Exploring the use of evidence in practice by Australian special librarians

Alisa Howlett and Zaana Howard

Information Systems School, Science and Engineering Faculty

Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia.

Introduction

Evidence-based library and information practice is a process through which evidence in its various forms is encountered, sourced, appraised and applied to inform practice. Evidence in much of the existing library and information science literature is considered to be ‘published research', with insufficient acknowledgement of other types of evidence relevant to the professional context. Concurrently, there is little understanding with regard to library and information professionals' perspectives on what constitutes evidence and how it is used to inform practice. The purpose of this paper is to share findings from a qualitative study focused on Australian special librarians which sought to identify the types of evidence they used in practice and how, including exploring influences associated with the contextual environment. This was achieved through the collection of participant diaries and qualitative interviews with five special librarians.

This paper commences by discussing existing evidence-based library and information practice literature, identifying gaps and providing the framework for this study. This is followed by an outline of the data collection and analysis methods used. Findings are then described and the role of evidence from a practitioners' perspective is outlined with relevant evidence-based library and information practice literature. Finally, limitations of this study are identified, and future directions for research conclude the paper.

Identifying evidence in evidence-based library and information practice

Evidence-based library and information practice is a model derived from medical origins. The framework's application to the library and information context however raises uncertainty regarding the sources of evidence which inform practice. In an early definition, Eldredge (2002) identifies research as the primary source of evidence through which library and information practice is improved. Booth (2002) also identifies research evidence in his definition, yet in addition considers ‘user-reported' and ‘librarian observed' sources:

Evidence-based librarianship is an approach to information science that promotes the collection, interpretation and integration of valid, important and applicable user-reported, librarian observed, and research derived evidence. The best available evidence, moderated by user needs and preferences, is applied to improve the quality of professional judgments. (p. 53)

Further to this, Koufogiannakis (2011, p. 53) brings evidence sources together into a model which formulates a ‘more realistic view' of evidence, making evidence-based library and information practice ‘more robust and practitioner-friendly'. Koufogiannakis recognises local evidence and professional knowledge, together with research evidence as sources informing practice. According to Koufogiannakis, locally derived evidence is directly applicable to a specific context as it is concerned with addressing the needs of the users the information service serves within their specific communities. Examples of local evidence include usage data, user feedback and evaluation of programs and services. Professional knowledge as evidence focuses on the notion that library and information practitioners are ‘action oriented' and often draw on ‘real life' experiences to improve practice with on the job training and tacit knowledge provided as examples of professional knowledge evidence (Koufogiannakis, 2011; Marshall, 2003). Koufogiannakis calls for these additional sources of evidence to be valued alongside research in the evidence-based library and information practice model, so it is more meaningful and applicable to the library and information professional context. Broadening the concept of evidence would create a more inclusive and pragmatic evidence-based library and information practice model for the profession.

Little is known about how library and information practitioners conceptualise evidence-based library and information practice. Few empirical studies have explored this. Koufogiannakis's (2012) study of academic librarians' use of evidence found that academic librarians were, for the most part, unsure what constituted evidence, but regardless of the source, they were willing to consider whatever may inform decision making (Koufogiannakis, 2012). In an Australian study, participants described their experiences of the role of evidence and evidence-based library and information practice in their daily practice (Thorpe, Partridge, and Edwards, 2008). Thorpe et al. found using evidence is associated with justifying an information service, gaining approval from governing bodies or influencing decisions within an organisation (Thorpe et al., 2008, p. 6). Evidence used by Australian library and information practitioners in this study included research literature, as well as surveys, organisational strategy and feedback, which is consistent with the sources of evidence advocated by Koufogiannakis (2011) (Thorpe et al., 2008). These empirical studies provide insight into the practitioners' perspective on the use of evidence in practice. The findings test the existing evidence-based library and information practice model and contribute to a developing understanding of the role of evidence in library and information professional practice. This research study aims to initiate this conversation within the special library sector.

Evidence-based library and information practice and the realities of daily practice

Further to acknowledging the different evidence sources in the evidence-based library and information practice model, another limitation is its failure to consider the day-to-day realities faced by library and information practitioners. In particular, library and information practice often involves short term problems which require quick decisions, with consideration given to the constraints of the local context rather than reliance on research evidence (Thorpe et al., 2008). In line with this, Turner (2002), in surveying information professionals' use of published research, found factors of time constraints and relevance in the reasons why practitioners did not consult research evidence (Turner, 2002). Findings from Koufogiannakis' (2012) study of academic librarians' use of evidence also found that research evidence rarely provides specific answers to questions required to inform practice. An understanding of the role of evidence sources within the context of library and information practice will benefit what is understood as ‘best available' by practitioners.

What constitutes best available evidence and how it is applied within the realities of practice is not well understood. The application of this evidence is subjective and largely determined by how the evidence serves to answer questions about practice, problems, decisions or judgments, as it relates to the given context (Booth, 2004). Koufogiannakis (2012, p. 18) suggests best available evidence may be best of what is found and integrated into practice through a process of using a pragmatic perspective. Through this process and applying evidence moderated through user needs and preferences, it is only practitioners that can assign appropriate value and importance of evidence relative to the given context (Booth, 2002; Koufogiannakis, 2011). Understanding what is best available evidence in the library and information practice context will assist in further developing the profession's evidence-based practice model to more sufficiently address its aims. Thorpe et al. (2008) and Koufogiannakis (2011) are examples of the few empirical studies which have attempted to bridge the gap between the perceived ideal of relying on research evidence and the realities of evidence use in daily practice. This study aims to continue to develop an understanding of evidence and evidence-based practice in the library and information professional context through exploring practitioner lived experiences.

Research aims

To adopt an evidence-based approach to informing and improving practice acknowledgement of, and reflection upon, the types and sources of evidence; how they are being used; and what constitutes best available from the library and information practitioners' perspective is required. The purpose of this study was to investigate the role of evidence in the practice of Australian special librarians, which included to:

- identify sources and types of evidence used in practice, and

- explore influences associated with evidence use.

This research aims to raise awareness of evidence use in informing library and information practice by contributing an initial understanding of how it is used in the professional context of special libraries.

Method

A qualitative study was used to investigate, from the practitioners' perspective, evidence use in practice. For this study, special librarians were defined in accordance with the Special Libraries Association (2003), as information professionals who develop, deploy and manage information resources and services in highly specialised contexts with unique user needs. Recruitment was undertaken in line with Creswell's (2012) description of a convenience sampling method. Participants self-nominated involvement in response to an open invitation through Twitter and Australian Library and Information Association special libraries e-lists (Creswell, 2012). Five study participants were recruited. Two participants practiced in the health sector, one in the law sector, one in a corporate library in local government, and another was a specialist information consultant in the education sector.

Data collection methods of participant diaries and semi-structured interviews were utilised as they provided the opportunity to explore influences associated with participants' lived experiences with evidence use as it related to their unique working environments (Silverman and Marvasti, 2008).

Data collection

Over a two week period, each participant completed three, one-page guided reflections, which focused on identifying types of evidence used and why in specific circumstances (see Appendix 1). The purpose of the reflections was to capture evidence use as it happened during the course of undertaking day-to-day duties. Written reflections were selected as direct observation may have altered how participants encountered or sourced evidence for their practice, potentially compromising data and findings. So as to not disrupt participants' natural flow of undertaking day-to-day duties and tasks, a flexible approach was taken in the manner in which participants submitted their reflections. Submitted reflections varied including hand-written directly into a hard copy of the template, and typed into an email or other electronic methods (for example, a Microsoft Word document).

Following the analysis of reflections, semi-structured interviews were utilised for clarification. Questions (see Appendix 2) prompted further exploration and reflection on participants' lived experiences. The semi-structured interview combines structure with freedom, and consists of a list of issues or topics to discuss and follow up points where necessary. This provided an opportunity to develop a more in-depth understanding of the use of evidence by participants (Creswell, 2012; Thomas and Hodges, 2010).

Data analysis

Data analysis commenced from the first submission of reflections from participants. All reflections were analysed separately, to initially generate interview questions and topics, and again as one dataset with interview data to derive meaning. A constant comparison method was used to uncover themes from the data which involved generating and connecting categories by comparing incidents in the data to other incidents (Creswell, 2012). An open coding process assisted with making sense of the data, labeling segments and allocating themes (Creswell, 2012). Existing relevant evidence-based library and information practice frameworks were referred to and informed the mapping of themes to develop a picture of an evidence base used by Australian special librarians.

Results

Findings describe the role of evidence in practice. Three themes emerged of:

- Practitioner perspectives of what is considered evidence;

- Environmental factors and influences associated with evidence use in practice, and

- How evidence is used or becomes relevant to the participants' working environment.

Each of these is explored in detail below.

A practitioner's perspective on evidence in practice

Across all semi-structured interviews one question was consistently asked: ‘What would you consider evidence in your practice?' It was found that all participants draw upon a range of evidence that included reports, literature, professional knowledge and experience. Participant 2 (corporate) described evidence as going beyond what is known about a particular situation or context to inform practice:

[Evidence] doesn't mean I need to go and do a formal study or literature review every time I start a new project, although there are times when it would be useful and good to do that...evidence means that I am trying to extend beyond my own experience and extend beyond my own taken for granted knowledge to look for other information that might challenge me or make me see things in a new way or provide some back up to my arguments.

All participants most readily identified their own professional knowledge and experience as a significant source of evidence informing their practice. Participant 4 (health) viewed this source of evidence to be ‘practical evidence', that it is ‘automatic'. It was further found that participants heavily relied upon their professional networks and contacts in order to gather evidence needed to be directly related to the participants' specific contexts in order to make informed decisions. Specifically, Participant 1 (consultant) recognised a ‘verification process' with colleagues when using evidence, while Participant 2 (corporate) reflected on the importance of professional networks, saying: ‘One of the most important things in special libraries is our networks because a lot of what we do is hidden, so it's really great to meet other people who are working in the field'.

Three participants, 2 (corporate), 3 (law) and 4 (health) went further to weigh other practitioners' knowledge in terms of relevance or proximity to the information service. For example, Participant 3 (law) considered other practitioners' knowledge in other law firms, as well as knowledge from employees from within the organisation as a ‘strong' source of evidence. Participant 4 (health) had also reported liaising with colleagues who had expertise in specific areas to improve the information service. Liaising and interacting with other practitioners and employees saved the participant's time when making a decision. Taking this a step further, Participant 2 (corporate) specifically described searching the literature as another way of accessing other professionals' knowledge. Though not necessarily preferred, the literature was expected to have a higher level of validity than a colleague or peer because it was published.

Research evidence was not disregarded by participants, however the definition was broadened beyond published research, which for this study was defined as academic research published in journals or other periodicals. Government reports and reviews, as well as statements and standards from professional organisations such as Australian Library and Information Association or the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA), were identified by Participant 2 (corporate) as types of research evidence. They considered these to be informed by research and in-depth analysis exhibiting validity and more relevance than published research. Overall, it was found all participants, as library and information practitioners, identified evidence as information sufficient to meet a need or fill a gap in understanding a given situation.

Environmental factors and influences on evidence use in practice

A range of environmental factors and influences were found to impact on evidence used in practice. Environmental factors were primarily internal to the organisation or special library. Time was the most reported influence in using evidence in practice. Time restrictions were dictated by user needs, preferences and other stakeholders, such as decision makers. For example, Participant 1 (consultant) reflected that a person's position, such as a CEO, influenced the evidence gathered. It was observed in the semi-structured interviews that all participants were well attuned to their organisational environments and requirements, enabling them to easily recognise evidence to best meet their needs within time restrictions. An example was provided by Participant 3 (law): ‘People need things now, they don't need me to go away for a week to find particular information. I need this...by the end of the day. You have to use evidence and resources that are easy to access.'

From both Participant 1 (consultant) and Participant 3 (law) experiences of evidence use, it appeared that the most influential stakeholders of the information service, such as managers across an organisation, determine the types of evidence to be collected, used or applied. This potentially superseded the participants' otherwise professional judgment.

Responding to these influences, Participant 2 (corporate) and Participant 3 (law) identified key drivers for using evidence for purposes such as demonstrating value or return on investment and accurately reporting the contributions made to the organisation. Participant 2 (corporate) highlighted use of evidence to support communicating value to stakeholders:

We're asking council and ratepayers to pay for those things [services], so we need to demonstrate value for the community. It's not sufficient to say we want to do something because we've always done it or think it's a good idea.

In addition to Participant 2 (corporate), decision makers' expectations of what constitutes evidence for demonstrating a return on investment was mentioned by Participant 3 (law), who compiles a regular report to the executive team.

Other organisational influences, reflected on by all participants, include the budget or the resources allocated to the information service, which impacted on the accessibility and availability of certain types of evidence they might otherwise consider for practice. For example, Participant 1 (consultant) reported the information service did not have access to subscription databases, however an internet search provided useful functionality and enabled access to a range of information. Participants 2 (corporate), 3 (law) and 4 (health) reported that evidence judged relevant to the context are types that are easily accessible and do not take a great deal of time and resources to collect. Attributes of these types of evidence include being easily searchable, routinely collected or curated collections of information resources kept on hand.

Making evidence readily available for integration with practice

It was found that evidence from outside the immediate special library context can be made readily available if it is collected before it is needed. Participants 1 (consultant) and 2 (corporate) spoke about strategies they use to keep up to date with the broader professional context. These included curating a collection of information that is saved and organised in a way which makes the information useful when the need arises. Participant 2 (corporate) maintains a ‘Reading and Ideas' folder where relevant material is kept on hand. The same participant routinely gathers feedback from users about the resources and services provided, also making this type of evidence readily available:

[the customer satisfaction survey] is a good way to gather some internal information without having to do another customer engagement process....a current awareness folder where I file articles and web pages that I come across every day, during the course of my work, a great resource to dip into.

A related experience is Participant 1 (consultant) who regularly receives ‘daily digests', a form of knowledge sharing across the organisation that is ‘stashed away for use when needed'. These ‘desktop' methods of collecting information brings potentially relevant evidence into the organisational context on a just in case basis. Participant 2 (corporate) describes this process:

Only when I file it away and flag it for myself as something we're not doing right now but might look at doing in the future and then I have some reading there ready to go for when we have time.

Developing a collection of potential evidence when circumstances permit, enables Participant 1 (consultant) and Participant 2 (corporate) to consider a wider range of evidence not usually possible when the need for evidence arises. While not explicitly stated by these participants, it was found descriptions of these processes involved: reflecting on what is currently known or not known to assist with informing a situation; the working environment and user needs; and how the evidence might be related to the specific context or benefit the delivery of the information service.

Discussion

Findings highlighted practitioner perspectives of evidence, environmental influences on evidence use and strategies used by the participants for making evidence readily available. These themes are further explored in relation to relevant evidence-based library and information practice literature.

A diverse range of evidence from spheres of contextual relevant

What was found to constitute evidence by Australian special librarians within this study differed from the perspectives of academic librarians shared in Koufogiannakis' (2012) study. Australian special librarians in this study readily identified professional knowledge and experience, both their own and others in their network, as evidence informing practice. However, academic librarians in Koufogiannakis' (2012) study were not as inclined to this view, instead acknowledging this source of evidence was used, but did not feel certain that experience or opinion could be considered as evidence.

The different range of evidence available to both these sectors (academic and special) and professionals may provide an explanation for this variation. Factors relating to accessibility, availability and applicability of evidence appear to impact the sourcing and use of evidence in practice. It is possible the breadth of published research relevant to the academic library sector leads to it being viewed as more relevant and identified as evidence. Participants in this study rely heavily on real life connections to specific contexts. Direct application of published research to practice is limited due to the heterogeneity of special library contexts.

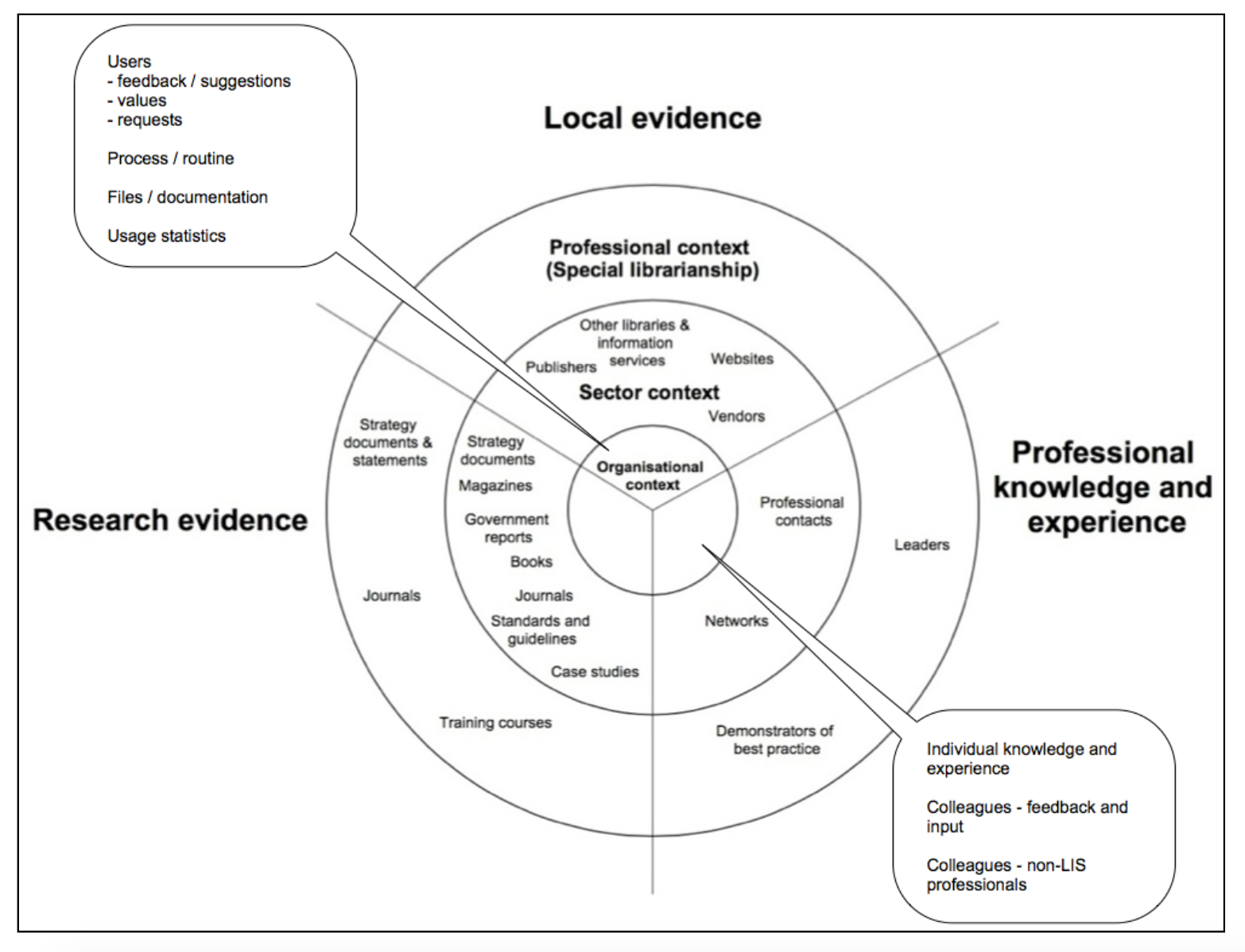

Evidence was found to be used by Australian special librarians to various extents in their practice. Koufogiannakis' (2011) three sources of evidence, research and local or professional knowledge and experience, provide the backdrop for categorising types of evidence used by the participants of this study. Figure 1 presents the different types of evidence used by participants, in accordance with source and the extent to which the type of evidence is relevant to the special library context. Three spheres of contextual relevance - organisational context, sector context and the professional context - add a dimension to understanding evidence use. While professional knowledge and experience and local evidence could be found within the organisational context, research evidence was not. The extent to which the evidence is applied reflects the specificity and complexity of the special library context.

At the centre of the sphere, the organisational context is closest to the specific situation or special library and represents the evidence most relevant. The sector context is the industry or field in which the organisation is situated, such as law or health. Information about other services and relevant vendors is collected from this sphere. The professional sphere of relevance relates to the overarching context that is special librarianship. Examples of the types of evidence found in this sphere include training courses and published research. Contextual relevance of the evidence influences its value relative to the situation or understanding of specific issues. The closer the evidence is to the organisational context or the higher the impact it may potentially have, determines the degree to which the evidence can be applied or integrated into practice.

The mapping of evidence types and sources relative to the specific contexts of special libraries shows an evidence base that is available to library and information practitioners. Relative to the impact, influence or applicability to a situation, a library and information practitioner may draw upon a number of types of evidence to assist with informing practice. When brought together, all three sources of evidence found by Koufogiannakis (2011) of research, local and professional knowledge and experience, suggests an evidence base that is defined by, and unique to, each library and information professional.

Influences, barriers and constraints affecting the use of evidence in practice

Findings of this study suggest environmental factors internal to the organisation (or information service) play a significant role in influencing evidence use in practice. Booth (2011, p. 13)admits literature related to barriers to evidence-based library and information practice, is ‘predominantly opinion based' with limited empirical investigations into the evidence-based library and information practice and how it is cultivated in the profession. Australian special librarians in this study experience evidence use as directed by their specific context, which consists of users or other stakeholders, organisational culture, systems and infrastructure, reporting relationships and the position of the information service within the organisation. Further to this, findings from this study suggest there are factors which influence the decision to use certain types of evidence, and there are factors which influence obtaining evidence. Workplace barriers to evidence-based library and information practice identified by Booth (2011), such as time and infrastructure, appear consistent with how participants of this study used evidence in their context. Other workplace barriers such as organisational support and financial resources, as well as additional barriers such as access to and limitations of the evidence base appear to influence how participants of this study obtained evidence for use in practice.

While existing evidence-based library and information practice literature label influences as barriers, participants of this study shared strategies for overcoming them. Methods included storing relevant literature and other material to be readily available for when the need for evidence arises. Barriers do not prevent practitioners from using evidence in practice, rather only influence how and when evidence is sourced or encountered and applied to instances. Barriers are not a question of what evidence practitioners have access to or what evidence is applied to practice, but are instead a question of how and when evidence may be applied.

From information to evidence: the "simmering" before evidence is used

Participant 1 (consultant) and Participant 2 (corporate) regularly collected and curated information resources in ways to make them readily available when needed. Participants identified this information as potentially relevant and useful evidence in the future with this initial process of bringing potential evidence within reach. This is where potential evidence ‘simmers' in the background, and is brought to the ‘boil' when a relevant situation requires it. Evidence is then searched, appraised further and prepared for application to decision making in a situation or integration to improve practice.

Koufogiannakis and Crumley (2004) present three categories for the extent to which evidence may be applied:

- the evidence is directly applicable;

- the evidence needs to be locally validated, and

- the evidence simply improves understanding.

Evidence, or this potential evidence, may move from improving understanding of issues or simply gathered information, to eventually being applied to practice. Koufogiannakis and Crumley's (2004) categories to applying evidence may provide the basis for a framework to explain how evidence is appraised and used. If evidence offers an improved understanding, it does not mean it is the end of life for applying it as evidence in practice at a later time. A decision to apply evidence is staged and is not necessarily made at the time of encounter or sourcing of the evidence. In this way, evidence may have multiple uses, depending on the situation.

From ‘simmering' to the ‘boil', participants appeared to use their initial or improved understanding of the issues to identify a further need for evidence. Appraisal of potential evidence and professional judgments about how the evidence may be applied to a given situation may result in it needing to be ‘locally validated' or ‘directly applied' to practice (Koufogiannakis and Crumley, 2004, p. 123). From current awareness to applying evidence to a specific situation, there is a process of reflection that draws upon professional knowledge and experience to make these judgments.

Limitations and future directions

Limitations of this qualitative research study include that it aimed to explore the role of evidence with a small number of Australian special librarians. With only five participants in the study and the heterogeneity of this sector, it is not possible to draw generalisations from responses given. Participant 5 (health) did not provide additional insight to the key themes identified in this study, neither agreeing nor disagreeing, and therefore direct reference to this participant was not suitable. It was also identified that pre-conceived understandings or gaps in understanding evidence-based library and information practice may have limited the number of participants identifying themselves as potential participants. Though having minimal impact on participant recruitment for the scale of the study, it is still important to acknowledge this potential limitation for future studies looking at evidence-based practice from a library and information practitioners' perspective.

Despite these limitations, the findings provide insight into understanding evidence-based library and information practice and highlights areas for future research. Findings of this study contribute an already forming picture of evidence use in library and information practice. More research in a different sector of library and information practice, public librarians for example, is needed to further develop an understanding of the role of evidence in informing practice from the practitioner's perspective. It is also recommended the role of professional knowledge and experience in the evidence-based practice approach, and/or informing practice, be explored further. Understanding of how this source of evidence is used and how it contributes to furthering best practice in the profession will lead to better recognition in the evidence-based library and information practice model. Only then can strategies be formed towards strengthening this evidence source for the library and information practice profession.

Conclusion

Evidence-based library and information practice will benefit from a more inclusive model that recognises evidence that is useful, relevant and applicable to professional practice. This study considered what evidence meant to Australian special librarians, and explored influences associated with sourcing, appraising and integrating evidence into practice. Contributing to the existing evidence-based library and information practice literature, this study raises awareness of the types and uses of evidence used by practitioners. This includes professional knowledge and local information such as usage statistics and client feedback.

The strategies used by practitioners in this study to source and appraise evidence from outside the organisational and sector contexts ahead of when the need arises, promotes the fact that research evidence, while untimely to access, is not disregarded as an important source of evidence. Findings of this study presented a map of an evidence base available to the participants that was relative to their specific context. If professional knowledge and experience is given further acknowledgment in the literature as a source of evidence informing library and information practice, the evidence base map suggests that evidence available to a practitioner would differ, making one unique to each library and information practitioner from which to draw from.

Findings of this study contributed insight and an initial understanding of evidence use in the context of special libraries. If a culture of evidence-based library and information practice is to be better embraced by the professional community, a deeper understanding of how evidence is used by practitioners, from their perspective and not researcher opinion, will be needed to ensure the evidence-based library and information practice model assists the very professionals and practice it seeks to improve and grow.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted as part of Master of IT study at QUT. Full ethical clearance for this study was obtained from the QUT Ethics Committee (QUT Ethics Approval Number 1300000164).

About the authors

Alisa Howlett is an information management specialist, currently a policy officer in an Australian archival authority. She received her Master of Information Technology (Library and Information Studies) from Queensland University of Technology in 2013. She can be contacted at acrystelle@gmail.com.

Zaana Howard is a Lecturer in Information Ecology at Queensland University of Technology in Australia. Zaana is near completion of a PhD, researching design thinking in practice in large organisations. She can be contacted at zaana@wearehuddle.com.