Exploring the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing in the public sector: the perspective of government agencies

Tung-Mou Yang

Department of Library and Information Science, National Taiwan University, No. 1, Sec. 4, Roosevelt Rd., Taipei, 10617 Taiwan

Yi-Jung Wu

Department of Public Policy and Management, Shih Hsin University, No. 1 Lane 17 Sec. 1 , Mu-Cha Rd. Taipei, Taiwan

Introduction

With the rapid development of information and communication technologies, electronic government has been an important strategy adopted by government administrations around the world to achieve better effectiveness and efficiency. Currently, as government programmes become increasingly interrelated, government agencies are further required to interact with other agencies to develop intricate interagency services and to address complex public problems. Accordingly, cross-boundary information sharing among government agencies is critical for government officials in tackling the complexity in the public sector. Particularly, related initiatives of cross-boundary information sharing can also be considered information technology projects while information system construction and business process changes are necessary to equip government agencies with the capabilities of sharing and using information across boundaries (Gil-Garcia and Pardo, 2005).

However, cross-boundary information sharing in the public sector is challenging and complicated due to various influencing factors. In the current e-government literature, researchers have studied cross-boundary information sharing from various perspectives to understand its complexity. Different barriers and enablers have been identified and discussed extensively from multiple perspectives, including technology, organization, legislation, policy and environment (Gil-Garcia, Chengalur-Smith and Duchessi, 2007; Gil-Garcia, Soon Ae and Janssen, 2009; Pardo and Tayi, 2007; Sayogo and Gil-Garcia, 2014; Yang and Wu, 2014). However, there is still limited research focusing on exploring how government agencies perceive the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing. In order to fill this gap, this exploratory research is conducted to provide a deeper analysis with empirical data support, and a preliminary framework is proposed for conceptualisation. Specifically, this research investigates the constructs and measures that government agencies employ to perceive the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing.

In the following sections, a literature review of the current development of cross-boundary information sharing in the public sector is first discussed. The definition of cross-boundary information sharing and related influential factors are presented. In addition, information quality and information system success models are discussed to form a preliminary framework for guiding this exploratory study. Next, research design and method in terms of the case study, data collection and data analysis are presented. Then, the results and findings of the study are listed with the support of empirical data. The implications of the study are also discussed and an enhanced conceptual framework is formed. Lastly, the paper ends with the contributions and limitations of the study, and directions for future research.

Literature review

For years, researchers have indicated the important role that cross-boundary information sharing plays in electronic government (Aedo, Díaz, Carroll, Convertino and Rosson, 2010; Dawes, 1996; Gil-Garcia, 2012; Pardo and Tayi, 2007; Sayogo and Gil-Garcia, 2014; Scholl and Klischewski, 2007). While government programmes have become increasingly interrelated, no single government agency possesses all the necessary resources to run public services without inputs from others. Collaboration is considered an imperative move, particularly in information sharing across the boundaries of government agencies (Pardo and Tayi, 2007). Some researchers also pinpoint the stages at which cross-boundary information sharing occurs during the development of electronic government (Klievink and Janssen, 2009; Layne and Lee, 2001). It is indicated that information sharing usually happens first across different levels of government agencies in the vertical dimension, then, among agencies having different functionalities in the horizontal dimension. Similarly, Gil-Garcia and Pardo (2005) further point out that the complexity of related initiatives grows from single agency level and interagency level to the intergovernmental level.

Defining cross-boundary information sharing

According to Barki and Pinsonneault (2005), cross-boundary information sharing usually accompanies the utilisation of information systems or telecommunication technologies to share information between groups, departments, or organizations. Similarly, Gil-Garcia, Pardo and Burke (2010) consider cross-boundary information sharing a complex socio-technical phenomenon. They define cross-boundary information sharing with four components, which are trusted social network, shared information, integrated data and interoperable technical infrastructure. Specifically, trusted social network means that social actors know and trust each other, and it forms the foundation to sustain the other three components. Shared information represents either tacit or explicit knowledge that is shared in forms such as formal documents, informal talks, email messages, and faxes. Integrated data is the integration of processed or raw data at the level of data element standards. Lastly, interoperable technical infrastructure means systems that include both hardware and software to facilitate information sharing across boundaries.

In addition, shared information and integrated data are further conceptualised into five types, which are collected raw data, value-added information, administration-oriented information, administration-oriented knowledge and domain-oriented knowledge respectively (Yang and Wu, 2013). It is indicated that in addition to administration-oriented information, collected raw data and value-added information represent the most frequently shared information across government agencies. Specifically, collected raw data means original datasets that are collected from the public or enterprises by government agencies. Value-added information refers to collected raw data that is further organized and analysed by government agencies before being shared with others. Furthermore, the boundary of information sharing is defined as a line to cross among participating government agencies (Zheng, Yang, Pardo and Jiang, 2009). There are two dimensions of boundaries, the vertical and horizontal dimensions. The vertical boundary exists between central and local government agencies, and the horizontal boundary occurs between parallel government agencies. The identified boundaries in the two dimensions are hierarchical, departmental, personal, geographic, development level, process and sectoral (Zheng et al., 2009; Yang, Zheng and Pardo, 2012). It is also indicated that boundaries in the vertical dimension are not always easier to cross than those in the horizontal dimension (Yang et al., 2012).

The complexity of cross-boundary information sharing

Researchers have indicated that cross-boundary information sharing is a complicated task in the public sector. In the recent electronic government literature, this complexity has been explored and discussed extensively from various perspectives, including technology, organization, sociology, ideology, and legislation and policy (Gil-Garcia, 2012; Gil-Garcia, Chengular-Smith and Duchessi, 2007; Gil-Garcia and Pardo, 2005; Gil-Garcia et al., 2009; Pardo, Nam and Burke, 2012; Pardo and Tayi, 2007; Sayogo and Gil-Garcia, 2014; Yang and Wu, 2014; Zhang and Dawes, 2006). In the technological perspective, different organizations are found to possess different hardware, software and data standards that act as impediments for information sharing using information systems (Atabakhsh, Larson, Petersen, Violette and Chen, 2004; Gil-Garcia, Chengular-Smith et al., 2007; Lam, 2005; Sayogo and Gil-Garcia, 2014; Zhang and Dawes, 2006). Security and confidentiality are also concerns that require carefully designed authorisation and authentication to protect data access (Chau, Atabakhsh, Zeng and Chen, 2001). Technological capabilities of participating government agencies also matter to the success of interagency information sharing (Lam, 2005).

Nevertheless, challenges of cross-boundary information sharing do not simply reside in technology. Other issues such as inter-organizational interactions, and legislation and policy, should also be considered and managed. Researchers indicate that cross-boundary information sharing can involve complex interactions among participating government agencies (Drake, Steckler and Koch, 2004; Gil-Garcia, Chengular-Smith et al., 2007; Lam, 2005; Luna-Reyes, Gil-Garcia and Cruz, 2007; Pardo and Tayi, 2007). Different organizations tend to have different values and cultures that make communication difficult. It is not easy to have several organizations target on one shared objective when they have diverse values and treat information differently (Atabakhsh et al., 2004). Accordingly, the sustainability of cross-boundary information sharing relies heavily on the interrelationships of participating organizations. Particularly, trust building is found to be a core component to influence related initiatives significantly (Dawes, 1996; Gil-Garcia, Guler, Pardo and Burke, 2010; Lips, O'Neill and Eppel, 2011; Pardo and Tayi, 2007). The concerns of perceived effort, perceived risk and perceived benefit of information sharing also count (Yang and Wu, 2014). Specifically, the availability of financial resources is found to act as a key determinant (Sayogo and Gil-Garcia, 2014). Furthermore, leaders of government agencies also play a critical role in related initiatives (Sayogo and Gil-Garcia, 2014), and leadership can be exercised and manifested through executive involvement, formal authority and informal leadership (Gil-Garcia, Pardo and Burke, 2007). Lastly, researchers suggest that appropriate legislation and policy is necessary to lay the foundation in order to sustain related initiatives, and to reduce the concerns of information privacy and confidentiality (Atabakhsh et al., 2004; Dawes, 1996; Lam, 2005; Zhang and Dawes, 2006).

Exploring the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing

Currently, there is still limited research focusing on exploring how government agencies evaluate the effectiveness of information sharing initiatives. Specifically, what are the potential constructs and measures that governement agencies employ to assess the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing? As Gil-Garcia, Pardo et al. (2010) suggest, trusted social networks, shared information, integrated data and interoperable technical infrastructure are the four core components of cross-boundary information sharing. Particularly, the qualities of shared information, integrated data and interoperable technical infrastructure built on trusted social network can be fundamental to the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing. In the following subsections, the paper first discusses information quality to correspond to shared information and integrated data, and then information systems success to correspond to integrated data and interoperable technical infrastructure.

Information quality

In information sharing initiatives, cross-boundary shared information is the essential part. Particularly, Klischewski and Scholl (2008) point out that information quality acts as an indispensable capstone and foundation in information-sharing initiatives, and is the defining aspect of all information sharing efforts among government agencies. They indicate that little attention has been paid to information quality in electronic government research, especially in computer-supported information sharing in electronic government integration and interoperation.

Tayi and Ballou (1998) indicate that information quality can be best defined as fitness for use. Some information that is appropriate for a certain purpose may not be suitable for another use. To assess information quality, they suggest looking beyond traditional concerns of the accuracy of information, and other concerns such as timeliness, compatible formats, semantics and completeness should be considered (Tayi and Ballou, 1998). In addition, information quality can be represented by four categories, an intrinsic category, contextual category, representational category and accessibility category (Lee, Strong, Kahn and Wang, 2002; Wang and Strong, 1996). Intrinsic category means that information has quality in its own right. Contextual category suggests that information should be considered within the context of the task at hand. The representational category examines not only whether information is concise and consistently represented, but also whether information is interpretable and easy to comprehend. Lastly, the accessibility category emphasises the accessibility and security of information stored in computer systems.

In addition, Klischewski and Scholl (2006, 2008) discuss eight dimensions of information quality in e-government integration and interoperation. They identify the following dimensions. 1) Accuracy: shared information is accessed, received and transmitted accurately without distortion. 2) Comprehensiveness: the consistency, presentation and completeness of shared information fits the need of an information receiver. 3) Currency: some agencies require real-time information and some do not. 4) Cognitive authority: the credibility the information or information source represents. 5) Assurance/reliability: the shared information is perceived as reliable and trustworthy. 6) Relevance, precision and recall: the shared information is relevant to an information receiver’s need, precision refers to the amount of relevant information retrieved over the total amount of all retrieved information, recall refers to the amount of relevant information retrieved over the total amount of relevant information in an information repository. 7) Timeliness: how fast the shared information can be retrieved or accessed by an information receiver. 8) Perceived value: similar to reliability and cognitive authority, perceived value is determined by an information receiver’s accumulated experience in terms of information itself and related information sharing processes.

Klischewski and Scholl (2006, 2008) further suggest that different levels of information quality may occur at different levels of integration and interoperation with different key players involved. It is essential to ensure that information receivers understand the specific purposes that original information is collected for. Perceived high quality of shared information is also expected to intensify the engagement of cross-boundary information sharing in government agencies.

Information system success

Researchers indicate that cross-boundary information sharing is usually the interconnection of information systems or telecommunication technologies to share information between entities such as groups, departments and organizations (Barki and Pinsonneault, 2005). Similarly, as Gil-Garcia, Pardo et al. (2010) assert, information sharing across government agencies requires interoperable technical infrastructure such as the interoperation of information systems. Scholl and Klischewski (2007) also point out that cross-boundary information sharing among government agencies is closely interrelated with process integration and information systems interoperation. They define information systems interoperation as the utilisation of information systems of government entities to share information. It is suggested that initiatives of cross-boundary information sharing can be considered information technology projects because information systems are employed to achieve information sharing objectives (Gil-Garcia, Chengular-Smith et al., 2007). Consequently, the success of the information systems used in cross-boundary information sharing is critical to the effectiveness of related initiatives.

Researchers indicate that understanding success in information systems is a complex challenge and is particularly more difficult in the public sector environment (Scott, DeLone and Golden, 2011). They suggest that information technology quality has an impact on the effectiveness of electronic government initiatives, and constructs of information system success, including information quality, system quality and service quality, should be employed to explore electronic government success (Sørum, Medaglia, Andersen, Scott and DeLone, 2012; Scott et al., 2011). According to DeLone and McLean (1992, 2003), information quality, system quality and service quality can be used to measure the effectiveness of information systems. In their information system success model, information quality is applied to measure semantic success, and system quality is applied to measure technical success. The later proposed service quality is applied to measure the quality of information service provided by information system professions and units. The three constructs can further influence users’ intention to use, usage and satisfaction in using information systems. Scott et al. (2011) indicate that the information success model has been applied predominantly in the private sector and little research has been conducted in identifying measures that determine electronic government systems success. They suggest that there is a need to further apply traditional constructs of information system success to explore and understand electronic government systems success.

The proposed research

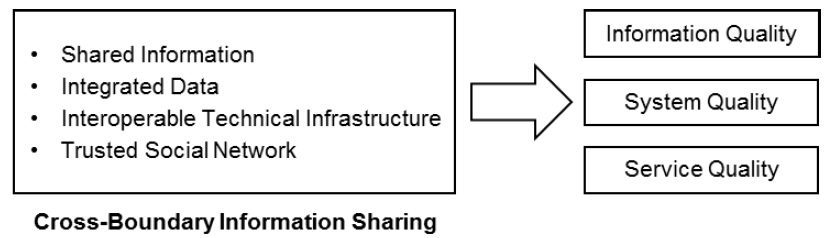

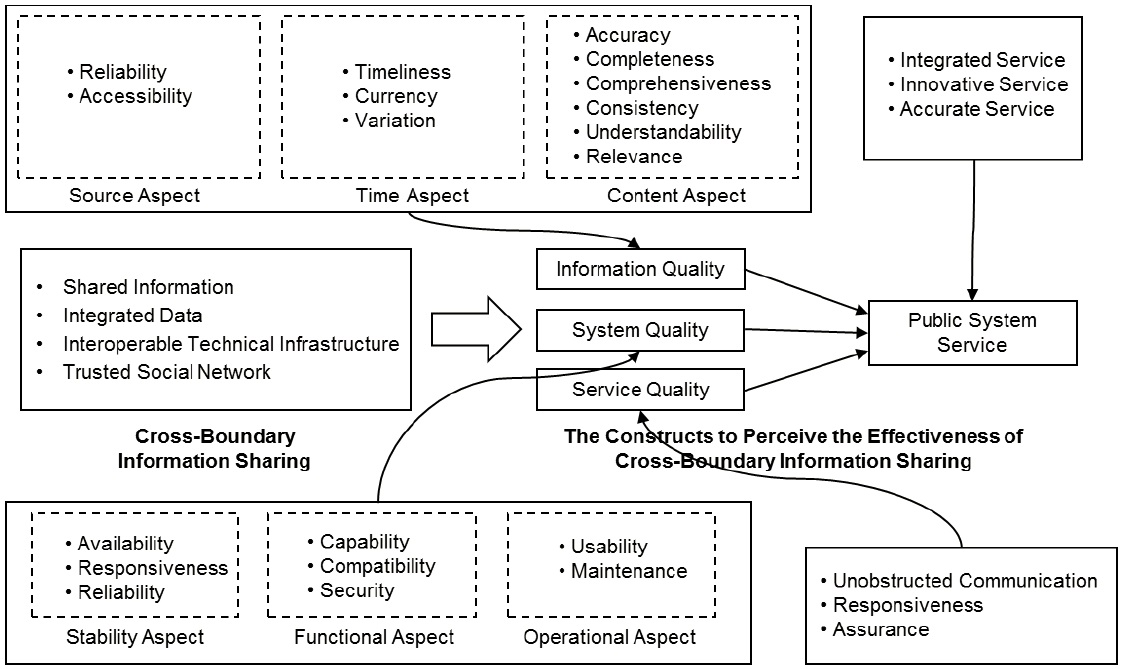

Currently, there is still limited empirical research investigating the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing in the public sector, and little research in this direction is done from the perspective of participating government agencies. In order to fill this gap, by drawing on a case study of Taiwan electronic government and using a qualitative approach, this study explores the potential constructs and measures that governemnt agencies employ to perceive the effectiveness of interagency information sharing. According to the aforementioned discussions about information quality and information system success, a preliminary conceptual framework is formed for guiding this research (see Figure 1). As Gil-Garcia, Pardo et al. (2010) assert, a trusted social network establishes the foundation of cross-boundary information sharing to enable and sustain shared information, integrated data and interoperable technical infrastructure. Particularly, this research adopts information quality, system quality and service quality to investigate the effectiveness of information sharing across government agencies. Based on an information system and technology oriented perspective, this research focuses on computer-aided information sharing in electronic government integration and interoperation as discussed by Klischewski and Scholl (2008). Specifically, the focused cross-boundary shared information of the study refers to integrated data defined by Gil-Garcia, Pardo et al. (2010), which means the integration or sharing of data at the level of data element standards. The data represent datasets that are either collected or produced by government agencies in their respective operations. Usually the data are raw datasets that are collected from the public and enterprises, or datasets that are further organized and analysed by agencies before being shared with others. Accordingly, in this research, the construct of information quality is applied to explore the semantic success of integrated data. The constructs of system quality and service quality are used to investigate the technical success of interoperable technical infrastructure.

Research design and method

In the research, a case study methodology was employed as it was considered appropriate for the exploration and classification of the knowledge building process. As Yin (2003) suggests, a case study methodology can help understand how or why a set of events occur, especially when the researcher has little control over the events and the focus of the study is a real-life contemporary phenomenon. In this research, through a case study methodology, the researchers were able to uncover how government agencies perceive the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing, and why some constructs and measures were adopted for the evaluation purpose. In addition, a case study methodology can offer in-depth and comprehensive coverage on a given research subject to facilitate theory articulation and enriching (Yin, 2003). Given the complexity of cross-boundary information sharing in the public sector, a case study methodology is an appropriate approach for this exploratory research.

The selected case in the study was from the context of the Taiwan electronic government. Specifically, a case study of the Electronic Networking Project of the Government Online Service in Taiwan was developed and used in the research. This project was a national flagship project and was a part of the Challenge 2008 - Taiwan National Development Plan initiated and supported by the Cabinet of Taiwan. The goal of the project was to promote and enhance cross-boundary information sharing among government agencies in Taiwan. In this case, government agencies were found to mainly rely on their respective information systems to interconnect with the systems of others for cross-boundary information sharing. Particularly, in the project a centralised information system, Government Service Platform, was designed and established under the supervision of the Research, Development and Evaluation Commission (which was superseded by the National Development Council in 2014) of the Cabinet. One of the major purposes of the Government Service Platform was to enclose the complexity of technology and maintenance into a single information technology platform to reduce agencies’ cost and effort in information sharing activities. Accordingly, the Government Service Platform was designed to act as an intermediary to facilitate information sharing among government agencies. For each participating agency, at least a legacy interface of its information systems was required to connect to the Government Service Platform to set up information sharing with other agencies. In the long term, the Government Service Platform can act as an entry point for both the public and private organizations to access public services while government information is shared across boundaries behind the scenes.

In this research, a purposive sampling methodology, using snowball sampling, was employed to identify relevant study participants. The first key interviewee was the deputy minister of the Research, Development and Evaluation Commission of the Cabinet of Taiwan. This key interviewee helped the researchers identify and contact other key players who participated in the Electronic Networking Project of the Government Online Service. Similarly, the identified key players further helped the researchers locate other key actors who were involved in the project. There were a total of twenty-three government officials interviewed by the researchers of the study. Eighteen participants were from central government agencies where they hold positions such as deputy minister, director, deputy director, section chief, technical specialist, information technology director and information technology consultant. Five participants were from local government agencies where they hold positions such as deputy director, section chief and specialist.

In-depth and semi-structured interviews were conducted to collect data for analysis. The average duration of interviews was about one and a half hours. Based on the preliminary conceptual framework, the interview questions were designed to help the researchers to explore how government agencies perceive the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing. The interview data were transcribed and analysed in Chinese. The important quotes were translated into English, and some are quoted in the paper for the purpose of theory explanation and illustration. The data analysis process followed an inductive approach by using techniques of open coding, axial coding and selective coding to analyse qualitative data. In the open coding process, the interview data were analysed, compared, conceptualised and categorised. Axial coding was then applied to group the initial codes produced in open coding and to uncover their relationships. Lastly, selective coding was used to interpret the relationships among the identified concepts and to ensure that the interpretation was coherent with the observed phenomenon of the case study. The qualitative software, Atlas-ti, was used by the researchers during coding and analysis processes.

Analysis and results

Based on the preliminary conceptual framework, information quality, system quality and service quality are the three constructs employed to explore how government agencies perceive the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing. The following subsections first present the identified measures of information quality and then system quality and service quality respectively.

Information quality

According to the interviewees, information quality is considered the most important construct to evaluate the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing among government agencies. The better quality the shared information, the better efficiency a government agency is able to achieve by utilising the shared information. Public services and agencies’ operations using the shared information can be more sustainable. An information technology director of a central government agency stated:

Information quality is the most important indicator to evaluate the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing. "Garbage in, garbage out!" If others share low-quality information with you, your output after integrating the information is definitely affected.

The following subsections present the eleven measures of information quality identified in the case study.

Accuracy: that is, the degree that information is correct and free of error. Information distortion during processes of information preparation and information retrieval can be accepted by an information requestor. According to the interviewees, the accuracy of shared information has a direct impact on the operations of government agencies using shared information. The interviewees indicated that inaccurate information may exist while it was first collected or was generated during processes such as calculating, transferring, or integrating data from various sources that have different data structures, standards and metadata. A section chief of a central government agency said:

We often receive inaccurate information from other agencies. However, we have no choice because we need the information to provide public services. There are many issues such as data entry errors and others that can raise the problem of information inaccuracy.

Completeness: means that the details of shared information achieve what is expected by an information requestor in terms of amount and specific items of information. The interviewees pointed out that sometimes an information provider may not have all the required information an information requestor needs. For instance, an information provider might just have six of eight items that an information requestor asks for. Even though the information provider provides all the six items with excellent quality, the shared information is still incomplete. The interviewees explained that incomplete shared information will not be used because there might be potential or unexpected problems caused by incompleteness. A director of a central government agency said:

We need to collect information from the twenty-five counties in Taiwan. If we end up obtaining the information from just fifteen counties, the information is still incomplete for us to conduct analysis. Similarly, we may need eighteen items of information from each local government agency. If we just got fifteen items of information, the information is also incomplete, and we won’t use it.

Comprehensiveness: as the interviewees suggested, comprehensiveness is a concept relative to completeness. Comprehensiveness means that the content of shared information covers greater detail than the requirement of an information requestor. Some interviewees indicated that when shared information from other government agencies is more comprehensive, they may be able to achieve better operational outputs by using the information. The detailed information can also provide more alternative approaches for information receivers to utilise and to obtain better results. For instance, some agencies have address information stored in one field: the usefulness of the information becomes limited. In contrast, some agencies have address information stored in separate fields such as street, district, city and zip code. The separate details of address information can provide more alternative usages such as statistical analysis. A deputy director of a central government agency gave another example:

When the shared information from other agencies is more comprehensive, we are able to conduct a better tax inspection in a greater detail than expected. Therefore, our taxation revenue can be increased significantly.

Consistency: suggests that the style, format and structure of shared information consistently comply with the requirements of an information requestor. According to the interviewees, the required format and structure of shared information is critical for an information requestor to process and integrate the information into its information systems. For periodic information sharing, the consistency of shared information in a regulated format and structure is important especially when a large amount of electronic information is shared. A section chief of a central government agency explained:

We request social welfare information sharing from twenty-five local government agencies and require the shared information conform to the standard format. However, we often receive different formats while local government agencies have high staff turnover rates, and the consistency of information sharing in required format becomes difficult to control.

Understandability

Understandability means the degree to which an information receiver can understand and interpret the meaning of shared information. According to the interviewees, government agencies have different core businesses, and their shared information can contain special syntax and terms such as nouns, codes and symbols that represent special meanings or treatments of shared information. Accordingly, the interviewees suggested that the understanding of shared information is important for utilising information correctly. An information technology specialist of a central government said:

A big challenge for us now is the understandability of shared information. Currently, an agency shares information with us every month. However, there are always some special codes within the shared information. Each time, we have to carefully figure out what those codes mean in order to process and integrate the shared information.

Timeliness: means whether the time spent to retrieve shared information can be tolerable or acceptable for an information receiver to fit its needs. It was found that time required to prepare information sharing varies among government agencies. Information preparation can be a process of integrating data from several information systems within an agency, or even a process of aggregating information from other agencies, and the cost of time can be high. Consequently, the interviewees indicated that information preparation is usually a time-consuming task, and immediate information sharing could be difficult in some circumstances. A section chief of a central government agency stated:

It can be time-consuming to prepare information while the required information has to be processed and aggregated from other agencies. Other agencies may transmit information to us once a day or once a week. It is inevitable that a time gap exists.

Currency: is a concept relative to timeliness. Currency means whether shared information can meet the real-time information need of an information receiver. In the case study, it was found that some government agencies have operations that need to retrieve information from the information systems of the Department of Household Registration and the Department of Land Administration. The agencies need to have real-time information search and authentication across agencies to verify whether the applicants of their public services provide correct information such as personal identifications and land certificates to apply for services. The interviewees clearly pointed out that real-time information sharing is critical for some government agencies to run daily operations appropriately.

Variation: means the extent to which the content of shared information changes in terms of time. As a result, it could be difficult to maintain the accuracy of shared information for a period of time if the variation of shared information is high. In the case study it was found that some information, such as household registration and company registration, can be frequently updated by the public on a daily basis. The cross-boundary shared information could become inaccurate within a very short period of time, and real-time information sharing is usually recommended. Consequently, for information that is difficult to share in high frequency or real time, the accuracy of the shared information can be impacted if the shared information has high variation that makes it difficult to retain accuracy. A deputy director of a central government agency gave an example:

We periodically acquire stock transaction data from other agencies for taxation purposes. However, the shared information we acquire can soon become inaccurate for us to know who possess what stocks. Accordingly, this information sharing becomes useless and even troublesome after we integrate the information within our public services.

Reliability

Reliability suggests that information from an information provider is perceived to be reliable, dependable and trustworthy by an information receiver. In the case study, the Department of Household Registration and the Department of Commerce are the authorised agencies by legislation to collect household registration information and company registration information. Although some agencies such as the Financial Data Center also possess similar information because of their respective operations, the interviewees still incline to trust that the Department of Household Registration and the Department of Commerce are the two authorities to provide the most complete and up-to-date registration information. A specialist of a central government agency stated:

We believe the information because the government agency we request information from is the only legally authorised government agency to collect such information. We have our trust on the reliability of its shared information.

Relevance: means the degree to which shared information fits the need of an information receiver. The interviewees suggested whether shared information is relevant to their need is critical for the following usage. In addition, the interviewees indicated that the need for information sharing should be clearly defined and articulated in the very beginning of an initiative. The misunderstanding of information requirement could lead to a discrepancy and make an information provider share information that has little relevance or is even irrelevant to the need of an information receiver. A deputy director of a central government agency said:

It is possible that shared information from other agencies is not what we expect to receive. I think it is the issue that we didn’t clearly state the information we want. This misunderstanding can cause us to receive information that is not very relevant to fit our need.

Accessibility: means the degree of challenge to access cross-boundary shared information. According to the interviewees, different information providers can use different approaches to sharing information. If an information provider uses traditional paper-based information sharing, the accessibility becomes limited because of the constraint of physical paper. In addition, if an information provider shares information electronically by using the Government Service Platform, an information receiver also needs to be capable of having its information systems connected to the platform to access information. Furthermore, the interviewees pointed out that sometimes even when information is shared electronically, they still need to spend extra time and labour to parse and arrange the shared information in order to integrate the information into their information systems. A director of a central government agency explained:

Accessibility is important. You have to know whether the shared information can be easily retrieved. If you need to access and process the information by hand, it is slow and labour-intensive. If the amount of shared information is huge, network transmission is probably not a good idea. There are many different aspects to consider.

In sum, based on the interview data of the case study, eleven measures of information quality are identified and presented to know how government agencies perceive the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing (see Table 1).

| Measure | Definition |

|---|---|

| Accuracy | Accuracy means the degree that shared information is correct and free of error. Also how much information distortion during information preparing and information retrieving is acceptable by an information requestor. |

| Completeness | Completeness means that the details of shared information fulfill what is required by an information requestor in terms of amount and specific items of information. |

| Comprehensiveness | Comprehensiveness is a concept relative to completeness. Comprehensiveness means that the content of shared information covers a greater detail rather than the minimum requirement of an information requestor. |

| Consistency | Consistency means that the style, format and structure of shared information consistently comply with the requirement of an information requestor. |

| Understandability | Understandability means to what degree an information receiver can understand and interpret the meaning of the shared information from an information provider. |

| Timeliness | Timeliness means whether the time spent to retrieve shared information can be tolerable or acceptable for an information receiver to fit its needs. |

| Currency | Currency is a concept relative to timeliness. Currency means whether shared information can meet the real-time information need of an information receiver. |

| Variation | Variation means the extent to which the content of shared information changes in terms of time. |

| Reliability | Reliability means that shared information from an information provider is perceived with confidence to be reliable, dependable and trustworthy by an information receiver. |

| Relevance | Relevance means to what degree the shared information from an information provider fits the need of an information receiver. |

| Accessibility | Accessibility means the degree of challenge for an information receiver to access the shared information from an information provider. |

System quality

As Gil-Garcia, Chengular-Smith et al. (2007) indicate, information systems are usually brought in to alter existing organizational structures and business processes to achieve information sharing objectives. The interviewees also claimed that information systems play an important role to facilitate information sharing across government agencies. Particularly, in the case study, the Government Service Platform was established to act as an intermediary to help the interconnection of information systems of agencies to share information. While system quality is adopted to understand the technical success of interoperable technical infrastructure, the following subsections present the eight measures of system quality found in the case that the interviewees used to perceive the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing.

Availability: whether an information system is ready and accessible for use whenever a user has to use the system for the purpose of cross-boundary information sharing. The interviewees suggested that an information system should be online for twenty-four hours a day to provide non-stop services. Nevertheless, some interviewees indicated that their utilised information systems, such as the Government Service Platform, could have regular or even unscheduled maintenance periods that influence the availability of the information systems. In addition, it was found that some local government agencies shut down their information systems after working hours or on weekends. The government agencies connecting their information systems to those local agencies inevitably encounter the challenge of acquiring information to provide non-stop public services. A deputy director of a central government agency stated:

Do you know that information systems of some local government agencies are only available during working time on weekdays? However, our information systems connecting with those have to offer non-stop services because the public usually uses our services in evenings or on weekends when they have free time.

Responsiveness: whether the responding time of an information system can be tolerated and accepted by its users when the system is used to retrieve shared information. The interviewees suggested that the responsiveness of an information system is critical to satisfy its users. It was found that the responsiveness of an information system can be impacted by issues such as limited network bandwidth or heavy loading on the information system or its connected systems. The interviewees indicated that the performance of their operations can be seriously dragged if the utilised information systems to retrieve information respond inefficiently. As a deputy director of a central government agency said:

When we use an information system to retrieve shared information from another government agency, the responding time of the utilised information system should be in the tolerable range to meet our expectation.

Reliability: the degree that an information system can correctly process and transmit shared information. The interviewees suggested that the reliability of information systems to retrieve shared information is critical. It was indicated that some information systems of government agencies may not be reliable to transmit information requests and shared information across boundaries. A specialist of a central government agency gave an example:

For instance, through an intermediate system, we sent out ten requests to an agency to retrieve information. However, it was found that only six requests were delivered, and the other four requests were lost. On the other hand, if the agency received one hundred requests from us, we might just receive sixty responses, and the other forty responses were lost. This situation happens often.

Capability: means whether an information system can sustain a user’s needs to share and retrieve information. It was found that government agencies have various requirements to evaluate their utilised information systems in information sharing initiatives. For instance, in the case study, some agencies need information systems to be capable of real-time information sharing, and each transaction has to be executed and finished in just a few seconds. On the other hand, some agencies may demand information systems to be able to process a huge amount of information. A deputy director of a central government agency stated:

We need to have one million transactions of information sharing from other government agencies every month. However, the information system we use can only sustain two hundred thousand transactions each month. After consideration, we may have to give up using the current system and turn to look for other alternatives.

Compatibility: the degree that a government agency’s information systems can be compatible with the information systems of other agencies to share and retrieve information. According to the interviewees, some agencies can possess obsolete information systems that are not compatible with others and even challenge cross-boundary information sharing efforts. Some obsolete information systems are also limited to run under specific software and hardware. As a result, it was found that one major task of the proposed Government Service Platform of the case study is to apply newer technologies such as web services to gradually resolve the incompatibility issue of legacy information systems in government agencies.

Security: whether an information system can securely transmit shared information among government agencies and maintain secure control to access shared information. According to the interviewees, secure information transmission is critical for an information system to protect the confidentiality of shared information when the information is transmitted between agencies through computer networks. Particularly, it was indicated that a strict control, regarding what information to share, how to transmit information, and who is permitted to access information, at what time and for what purpose, is necessary to protect information confidentiality. The interviewees suggested that information systems should be capable of maintaining, controlling, authorising and tracing how information is accessed and shared among agencies. In this study, it was found that the Government Service Platform incorporates the mechanism of Public Key Infrastructure to provide a more secured environment for agencies to share information across boundaries.

Usability: the degree that the design and user interface of an information system are convenient for users to operate. According to the interviewees, when using information systems, some users prefer dealing with several steps within a single page of user interface rather than separate pages. The interviewees indicated that a friendly and well-designed user interface can assist users to get acquainted with the operation of an information system. Some interviewees also suggested that information systems can be relatively easy and intuitive to operate while the concept of Web information systems is employed by integrating Web browsers to present front-end user interfaces.

Maintenance: the degree of effort and cost that are needed to sustain and keep an information system running properly. According to the interviewees, the maintenance of their information systems to share information can become a growing burden. When a government agency interacts with more agencies and organizations in information sharing, the agency would need to set up more connecting interfaces for its information systems, and the maintenance cost of the interfaces connecting to other information systems, including the Government Service Platform, keeps rising and becomes a concern. A deputy director of a central government agency said:

When we have information sharing with more agencies, the interfaces of our information systems become more complicated. The maintenance of information systems turns to be a difficult task that we also need to take into consideration.

In sum, based on the interview data of the case study, eight measures of system quality are identified to know how government agencies perceive the quality of interoperable technical infrastructure in cross-boundary information sharing (see Table 2).

| Measure | Definition |

|---|---|

| Availability | Availability means an information system is ready and accessible for use whenever a user has to use the system for the purpose of cross-boundary information sharing. |

| Responsiveness | Responsiveness means whether the responding time of an information system can be tolerated and acceptable by its users when the system is used to retrieve shared information. |

| Reliability | Reliability means the degree that an information system can correctly process and transmit shared information. |

| Capability | Capability means whether an information system can sustain a user’s needs to share and retrieve information. |

| Compatibility | Compatibility means the degree that a government agency’s utilised information system to share and retrieve information can be compatible with the information systems of other agencies. |

| Security | Security means whether an information system can securely transmit shared information among government agencies and maintain secure control to access the shared information. |

| Usability | Usability means the degree that the design and user interface of an information system are convenient for users to operate. |

| Maintenance | Maintenance means the degree of effort and cost that are needed to sustain and keep an information system running properly. |

Service quality

The service quality construct evaluates the quality of information services provided by information system professionals in information sharing initiatives. In general, the interviewees of the case study were found to be satisfied with the information services they received from information system professionals. However, the interviewees suggested that there is still room for further improvement to enhance the current service quality. The interviewees agreed that service quality of the utilised information systems is critical to satisfy users in information sharing initiatives. The following subsections present the three measures of service quality employed by the interviewees to perceive the quality of received information services.

Communication: evaluates service quality by assessing whether a well-maintained channel exists to enable smooth dialogues between users and information system professionals. Some interviewees suggested that information system professionals could maintain a better communication channel with them. For instance, some interviewees indicated that the information systems they use can sometimes be upgraded or modified without notification in advance, and their regular operations can be interrupted. As a result, their subsystems connecting to the utilised information systems for information sharing could be suspended from working properly while the subsystems become incompatible with the upgraded or modified information systems. The interviewees suggested that a specifically designated contact can maintain a direct and more efficient communication channel between users and information system professionals.

Responsiveness: whether information system professionals can promptly react and respond to users’ questions and requests. According to the interviewees the utilised information systems, such as the Government Service Platform, are maintained with established standard operating procedures, and the questions brought up or requirements of users can be resolved rapidly. Nevertheless, some interviewees indicated that the responsiveness of information system professionals can be seriously dragged in dealing with information loss as information sharing is a complex inter-organizational process involving providers, intermediaries and receivers. The interviewees also pointed out that the responsiveness of information system professionals varies while different information systems are utilised for information sharing purposes.

Assurance: whether information system professionals are believed to be capable of resolving the problems that users encounter, and users are satisfied with the results. In the case study, the interviewees indicated that the capability of information system professionals matters and is perceived as a criterion to evaluate service quality. For instance, some interviewees stated that information system professionals of the Government Service Platform possess sufficient technical capability to help them establish interfaces for connecting interagency information systems. In addition, sufficient support is offered by the professionals to help resolve issues the users encountered. Although some problems may not be resolved immediately, there are always answers and explanations given. The interviewees are confident of the information system professionals’ competence in providing a quality service.

In sum, according to the empirical data, three measures of service quality are identified, and government agencies use the measures to evaluate the quality of information services that information system professionals provide in cross-boundary information sharing (see Table 3).

| Measure | Definition |

|---|---|

| Communication | Communication means whether well-maintained channels exist to enable smooth and unobstructed dialogues between information system professionals and information system users. |

| Responsiveness | Responsiveness means whether information system professionals can promptly react and respond to information system users’ questions and requests. |

| Assurance | Assurance means whether information system professionals are believed to be capable of resolving the problems that information system users encounter, and users are also satisfied. |

Discussion

The identified measures of the three constructs

In this study, based on the preliminary conceptual framework, three constructs are employed by the researchers to explore how government agencies perceive the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing. Particularly, the most important construct found is information quality, and the empirical data also support that system quality and service quality matter while information sharing across boundaries usually needs the facilitation and interconnection of information systems among government agencies.

Specifically, there are eleven measures of information quality identified in the case study. According to the aforementioned literature, measures of information quality can be grouped into four categories, an intrinsic category, contextual category, representational category and accessibility category (Lee et al., 2002; Wang and Strong, 1996). In this study, the identified measures of accuracy and reliability can be grouped into the intrinsic category. Timeliness, currency, relevance, variation, completeness and comprehensiveness are included in the contextual category while the measures can have respective weights in different information sharing contexts. Understandability and consistency belong to the representational category while the focus is whether the shared information is easy to interpret and comprehend, and whether the shared information is concisely and consistently represented. Lastly, accessibility directly corresponds to the accessibility category.

Similarly, Klischewski and Scholl’s (2006, 2008) eight dimensions of information quality in e-government integration and interoperation are also found in the study with empirical data support. The identified measures, including accuracy, timeliness, currency and relevance can directly correspond to Klischewski and Scholl’s (2006, 2008) work respectively. Another three identified measures, completeness, comprehensiveness, and consistency, all correspond to Klischewski and Scholl’s (2006, 2008) concept of a comprehensiveness dimension. Lastly, another identified measure, reliability, means whether shared information is perceived to be reliable, dependable and trustworthy. This definition of reliability covers a greater range and corresponds to the three dimensions of Klischewski and Scholl’s (2006, 2008) work, which are cognitive authority, assurance/reliability and perceived value.

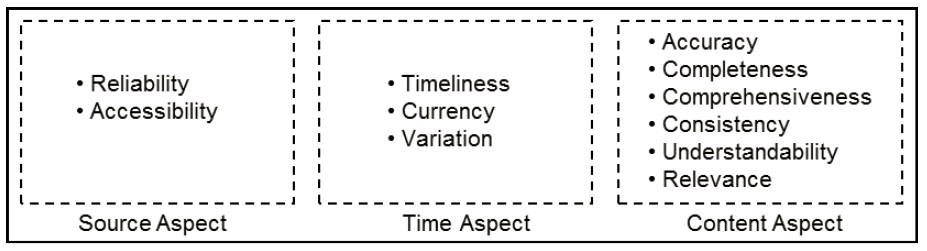

In addition to corresponding to the literature, the identified eleven measures can be discussed from three aspects based on their characteristics that government agencies use to evaluate information quality. Specifically, the three aspects are source aspect, time aspect and content aspect (see Figure 2). In terms of source aspect, reliability and accessibility are taken into consideration. The interviewees indicated that in initiatives of cross-boundary information sharing, they tend to evaluate whether shared information comes from reliable information providers having legitimate authority and it is difficult or easy to acquire shared information from information providers. Second, measures in the time aspect, including timeliness, currency and variation, are brought into consideration in terms of time variances. An information receiver may evaluate whether shared information can be delivered in a timely manner to comply with its business requirement, and some agencies may consider the currency measure when demanding real-time information sharing. An information receiver also has to include the variation measure to know how long the shared information can maintain its integrity, such as accuracy, in terms of timespan. Lastly, the measures in the content aspect are closely related to the intrinsic value of the content of cross-boundary shared information. The six measures in the content aspect are relevance, accuracy, completeness, comprehensiveness, consistency and understandability. Through these six measures, an information receiver evaluates: whether shared information is relevant to its need as expected; whether shared information maintains sufficient accuracy; whether shared information is as complete as possible with limited missing or shortage of data; whether shared information has comprehensive content that enhances usages; whether shared information is always consistent in terms of consented style and format; and whether the meaning of shared information can be understood and interpreted correctly.

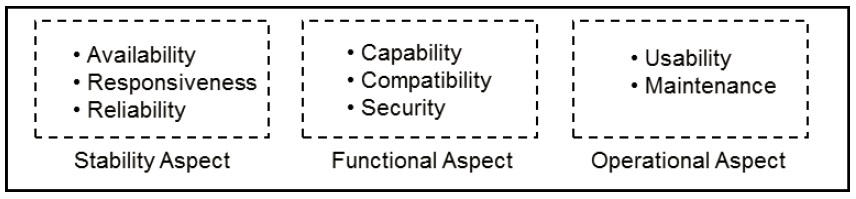

In addition, system quality and service quality are important while information systems of government agencies are interconnected in the case study to enable information sharing across boundaries. Particularly, the identified eight measures of system quality can also be conceptualised into three aspects, including the stability aspect, functional aspect and operational aspect, to discuss how government agencies evaluate the quality of utilised information systems in information sharing initiatives (see Figure 3). In the stability aspect, availability, responsiveness and reliability are the measures to assess whether an information system maintains steady status in cross-boundary information sharing. The three measures evaluate the fundamental performance of an information system to see whether a system is constantly accessible, reacts in a reasonable time, and is reliable during information transmission. In the functional aspect, capability, compatibility and security take one step further to require more developed functions of an information system. Cross-boundary information sharing can be highly demanding while processing large amounts of information in real time is needed, interconnection between information systems is necessary, and shared information can be sensitive and confidential. Accordingly, the measures in the functional aspect focus on evaluating whether an information system meets the needs of government agencies to provide a competent, integrated and secure information-sharing environment. Furthermore, in the operational aspect, there are two measures, usability and maintenance. The focus is on the human-computer interaction of operating an information system and related cost of maintaining a system. Specifically, government agencies employ the two measures to assess the degree of easiness or difficulty of using an information system and the related expense and effort of maintaining a system for information sharing purposes.

Lastly, the three identified measures of service quality are communication, responsiveness and assurance. The three measures focus on the interaction between users and information system professionals. Specifically, communication is the fundamental measure to examine whether an appropriate communication channel exists between users and information system professionals. Based on a sustainable communication channel, responsiveness takes one step further to evaluate whether information system professionals can promptly respond to users’ questions and problems. Likewise, assurance measures whether information system professionals possess sufficient technical capability and are competent to solve users’ problems and gain their satisfaction.

Public system service

In addition to the three quality constructs guiding this exploratory research, the interviewees further suggested that the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing should be explored from the aspect of public system services enhanced and enabled by the three quality constructs. This argument emphasises that whether information sharing initiatives can allow government agencies to improve current and create new public system services is an important aspect to consider. Similarly, the argument also corresponds to the net benefits construct of DeLone and McLean’s (2003) information system success model. A deputy director of a central government agency said:

You have to know whether the initiatives bring their influences. Otherwise, you say you get very good information quality, very reliable information systems and excellent service support, but if you don’t really apply the shared information to your work, every effort is in vain.

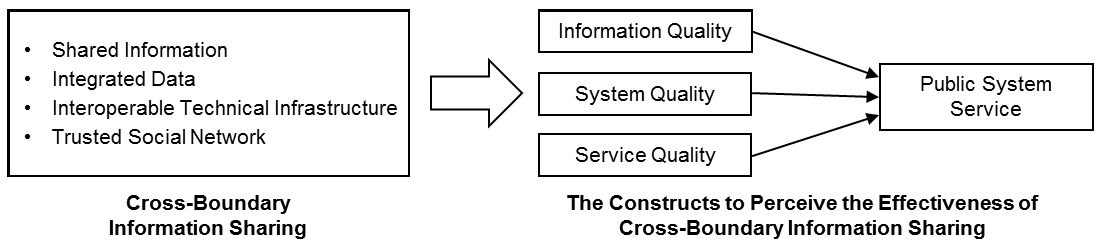

Accordingly, suggested by the interviewees, a public system service is included in the preliminary conceptual framework and is sustained by the three quality constructs (see Figure 4). Specifically, based on the empirical data of the case study, three measures are applied to evaluate whether public system services are enhanced and enabled by cross-boundary information sharing. The three measures are integrated service, innovative service and accurate service. The following subsections discuss the three measures respectively.

Integrated service means whether government agencies can provide one-stop or enhanced public system services through cross-boundary information sharing. According to the interviewees, with integrated services, the public is no longer required to physically attend several agencies to acquire documents or certificates to apply for public system services. Consequently, the time and cost for the public to apply for governmental services can be significantly reduced. Similarly, government agencies themselves can benefit from integrated services while their efficiency is greatly improved through electronic information sharing. Agencies do not have to spend extra effort on collecting certain information while shared information from other agencies is actually more comprehensive.

Innovative service suggests whether agencies are able to provide new and creative public system services enabled by interagency information sharing. The interviewees indicated that, in addition to increasing the efficiency of current public services, they can create new and innovative services by using cross-boundary shared information. It was found that some agencies are able to provide active public services rather than traditional passive public services. For instance, it was the case that the public had to understand policy regulations and to prepare documents to apply for public services such as social welfare benefits. Enabled by cross-boundary information sharing, agencies now are capable of conducting prior analyses and providing active public services by notifying qualified citizens to use their services.

Lastly, accurate service discusses whether agencies are able to provide public services more accurately or run operations more precisely through cross-boundary information sharing. The interviewees indicated that agencies may have obsolete and inaccurate information after long-term operations. Cross-boundary shared information can help agencies alleviate the concern of incorrect information by having databases cross-checked. Consequently, agencies are expected to obtain results with better performance when running their operations more precisely. For instance, in this study, the Financial Data Center receives electronically shared information from other agencies and is enabled to run its taxation operations more precisely, and the national tax revenue is increased because of more accurate tax collections.

The enhanced conceptual framework

By integrating the four constructs and the identified measures, the preliminary conceptual framework to explore the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing is enhanced (see Figure 5). Information quality, system quality and service quality act as the fundamental constructs to sustain public system service. Specifically, information quality is considered the most important one of the three fundamental constructs. Nevertheless, information quality is closely related to system quality and service quality while cross-boundary information sharing usually uses information systems as media for electronic information sharing. Service quality from information system professionals is also critical to both information quality and system quality. Particularly, information sharing initiatives do not rely on just one-time effort. Rather, information usually has to be periodically or continuously shared in related initiatives. Besides maintaining the stability and operation of information systems, information systems professionals also need to offer uninterrupted and prompt information services to satisfy users’ needs and to obtain their trust. In sum, the identified measures of the four constructs are expected to offer a more detailed discussion regarding how government agencies perceive the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing. Nevertheless, agencies participating in different information sharing initiatives could have different respective requirements. Accordingly, agencies can maintain different priorities in utilising the identified measures of the four constructs to evaluate the effectiveness of related initiatives they participate in.

Conclusion

In this study, a conceptual framework is presented for discussing how government agencies perceive the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing. Information quality, system quality, service quality and public system service are the four constructs employed to explore the phenomenon. The identified measures of the four constructs are also discussed extensively with the support of empirical data. Specifically, this study contributes to the current information-sharing literature by exploring the effectiveness of interagency information sharing through the quality of cross-boundary shared information, the quality of utilised information systems, the quality of information services provided by information system professionals and the public system services enabled by information sharing.

As Chen (2010) suggests, it is important to acquire citizen feedback during the movement towards more integrated government information systems to provide public services. Similarly, cross-boundary information sharing in the public sector relies on the interconnection of government information systems, and the feedback of participating government agencies is critical for evaluating and improving the related initiatives. Consequently, the findings of the study can provide insights to practitioners, including information providers, information receivers and information system professionals. Specifically, the proposed conceptual framework is expected to offer a systematic and comprehensive list. Practitioners can know more about the constructs and measures they can use to evaluate and improve the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing. Depending on respective needs and priorities, practitioners acting as information receivers can review the proposed conceptual framework to decide which constructs and measures they can employ to evaluate the information-sharing initiatives they engage in. In addition to the three quality constructs, information receivers are also encouraged to examine whether cross-boundary information sharing strengthens their public system operations to enable integrated, innovative and accurate services. Furthermore, practitioners acting as information providers can review the measures of information quality to understand the expectation of information receivers so that cross-boundary shared information can be provided from a more user-centric perspective. For instance, completeness represents one of the requirements of information receivers. If information providers can take one step further to voluntarily provide more comprehensive information, information receivers can actually benefit more from using the shared information. While information systems are critical to assist interagency information sharing, information system professionals are also encouraged to review the measures identified in the constructs of system quality and service quality. Finally, when an information sharing initiative begins, the proposed conceptual framework can also serve as a checklist for both participants to go through to ensure the sustainability of the initiative.

However, the current study has its own limitations. This research was conducted by using a qualitative approach, and a single case study was developed and conceptualised for discussions. Potential researcher biases could occur during data collection and analysis. Future research can employ other case studies for further exploration or confirmation through either a qualitative or a quantitative approach. According to Gil-Garcia, Pardo et al. (2010), a trusted social network establishes the foundation of cross-boundary information sharing to sustain shared information, integrated data, and an interoperable technical infrastructure. However, based on a perspective of information systems and technology, this research mainly focuses on integrated data and an interoperable technical infrastructure to explore the effectiveness of cross-boundary information sharing among government agencies. Future research should be conducted to explore how the quality of shared information is perceived by agencies, while the precise meaning of shared information such as formal documents, informal talks, email messages, and faxes is usually considered difficult to convey between information providers and information receivers. In addition, there is also a quest to explore the independent variables that have influences on information quality, system quality, service quality and public system service (Petter, DeLone and McLean, 2013). Furthermore, in the current information science literature, researchers mainly study information sharing at the interpersonal level to discuss the motivations, the influential factors, what information is shared, who is sharing and the contexts where information sharing happens. Accordingly, it is suggested that future research can explore how individuals perceive the effectiveness of information sharing at the interpersonal level in different contexts. Lastly, while cross-boundary information sharing has been an important theme in governmental collaboration, the findings and discussions of this exploratory research are expected to enrich the current information-sharing literature from the perspective of government agencies in the public sector.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to all the interviewees participating in the research for their time, patience and valuable information and suggestions. The authors are also grateful to the editor and two anonymous reviewers providing valuable insights and comments to help the authors improve the paper. The authors also thank Beth Gibbs, the editorial associate, for editing the paper. This study was partially funded by the National Science Council (Ministry of Science and Technology), Taiwan [grant number: NSC 102-2410-H-002-006-MY2].

About the authors

Tung-Mou Yang is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Library and Information

Science at National Taiwan University, Taiwan. Tung-Mou Yang received his Ph.D. in Information

Science from the University at Albany, State University of New York. His research interests include

e-Government, cross-boundary information sharing, information management, and information

systems. He is also interested in digital divide and other information-related

sociotechnical systems. He can be contacted at tmyang@ntu.edu.tw

Yi-Jung Wu is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Public Policy and Management

at Shih Hsin University, Taiwan. Yi-Jung Wu received her Ph.D. in Educational Administration

and Policy Studies from the University at Albany, State University of New York. Her

research interests include policy information integration, policy planning, and policy marketing

in the fields of social welfare and education, particularly for the applications to the

disadvantaged students in the higher education system. She can be contacted at yijungwu@cc.shu.edu.tw