Friend or foe: exploring master suppression techniques on Facebook

Rikard Harr, Annakarin Nyberg, Marcus Berggren, Richard Carlsson and Sebastian Källstedt

Introduction

Interaction is an essential part of our everyday lives and, whether we are aware of it or not, it often includes instances of power play. For example, power play is likely to occur when negotiating with our children about their screen time or when they will go to bed, or when questioning prices at a local market. However, instances of power play are not always as readily identified as in these examples.

Today, our interactions with others are as likely to occur online as offline. Internet-based interaction is in many ways a comparable alternative to traditional forms and most of us make frequent use of different sites, often social media sites, for daily interactions with friends, colleagues and other peers.

A study conducted in 2014 that charted Swedes' Internet habits showed that citizens spent an average of 3.8 hours a week on social media. However, people aged between 16 and 25 spent twice as much time on such sites (Findahl, 2014). Despite the fact that online interactions differ in some ways from their offline counterparts, there are also several similarities. For example, conflicts and power plays are likely to occur in both cases.

In this paper, we delve into online power play and master suppression techniques. We take as our starting point knowledge about domination techniques used in the offline work, and seek to determine how they are used in an online context, specifically on Facebook. A review of previous research on offline suppression techniques enabled us to develop an analytical tool that was applied to our collected data.

Established suppression techniques and their nuances have been described with a range of terms, many of which are negative (Ås, 1978, Eksvärd, 2011, Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014). We have all been exposed to instances of these, and probably employed them ourselves, even if we are not always aware of doing so. Conscious techniques are used to deliberately hurt others and are more easily detected, but unconscious ones are less readily discerned; a victim of unconscious suppression techniques might be unaware that they have been applied, and would only experience a feeling of discomfort or anxiety. All suppression techniques cause discomfort, and it is these, sometimes subtle, techniques and power plays that are under scrutiny in this paper.

Little is known about the occurrence and use of master suppression techniques on social media. Our work aims to change this by using a firm understanding of suppression techniques, domination techniques and related theory to inform an explorative study of these mechanisms on Facebook. Our ambition is to produce results that can help unravel this unexplored area by focusing on a specific medium and developing a categorisation model for future use.

With this aim in mind, we seek to answer two questions. First, there are many suppression techniques (with a range of nuances) that are known to be used in offline contexts. How many of these are manifested in the comment fields of open forums on Facebook? Second, how are these techniques and nuances manifested in this context?

Related work and theoretical framework

This section describes previous research related to the object of study and related relevant concepts.

Web 2.0 and social media

In recent years, Web 2.0 and social media have become increasingly common terms for describing new types of Web applications such as social networking sites (e.g. Facebook), blogs, micro blogs (Twitter), video sharing sites (YouTube) and wikis (Wikipedia) (Fuchs, 2013).

Social media and social software is an umbrella term for describing tools that 'increase our ability to share, to co-operate, with one-another, and to take collective action, all outside the framework of traditional institutional institutions and organizations' (Shirky. 2008, p. 20f). Users typically share information, pictures, and files, and are provided with opportunities to give and receive comments and feedback from others (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014). Facebook, Twitter and Instagram are all examples of social media, but in this paper we are focusing exclusively on Facebook. Facebook is currently the largest social media site, with 1.55 billion users worldwide (Statista, 2016). In Sweden, 66 percent of the population has used Facebook at some point; among people aged 16-25, this value rises to 95 percent, with 81 percent using the site daily (Nilsson, 2014).

Online disembodiment

An interesting dimension of Facebook, unlike many other social media, is that users are almost always identifiable: their names, pictures, occupation, education, and connections to different interest groups are publicly visible. Zhao, Gras Muck and Martin (2008) highlight the fact that users on anonymous sites can hide undesirable physical traits and construct their own biography and personality as they see fit, which the authors describe as online disembodiment. Sites such as Facebook, where users are identifiable, offer some scope for adjusting one's presentation (Zhao, Gras Muck and Martin, 2008), but only to a limited extent.

Individuals can sometimes use anonymity on Internet as a shield to hide behind, which allows users to express themselves in more radical, perhaps more aggressive, ways than they would use in a face-to-face situation. This behavior has been called the online disinhibiting effect and although Facebook is a social media platform with identifiable users, the effect is not uncommon there (Twenge, 2013).

Master suppression techniques

The concept of a master suppression technique was introduced by the Norwegian psychologist and philosopher Ingjald Nissen (1946) to describe the ways in which a person or a group behaves in order to maintain or increase their power in relation to others (Ländin, 2014). These techniques are used to maintain social superiority, and can include methods for degrading others (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2015).

A couple of decades after Nissen (1946) coined the term, the social psychologist and politician Berit Ås developed it further by creating a categorisation of different techniques known today as the five classical suppression techniques. These are making invisible, ridicule and reducing, conscious-disclosure of information, double punishment and imposition of guilt and shame. Ländin subsequently defined two additional techniques: objectification and violence or threats of violence (2014). Ås originally developed these categories to describe instances of male domination over women (1978), but modern researchers have adopted a slightly more neutral view, at least in terms of sex (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014).

Suppression techniques can be either conscious or unconscious, but are always used to suppress a group or individuals (Ländin, 2014). Being able to identify the techniques that an individual or group may face is a valuable competence because such knowledge can partially shield the intended victims from their effects (Ås and Johnson, 1982).

In the next section, we outline the classical suppression techniques described by Ås and some additional semi-classical techniques. We also broaden the scope of the discussion by addressing the suppression techniques described by Eksvärd (2011) and Ländin (2014), as well as the ten nuances of suppression techniques on social media developed by Nyberg and Wiberg (2014). The ambition is to provide a broad overview of the field to establish a foundation for our empirical study, and ultimately to extend the understanding of suppression techniques.

Distinguishing between master suppression techniques and other forms of hostile or unpleasant communication

Before discussing existing suppression techniques at length, it seems like a good idea to highlight some things that should not be regarded as such techniques. Ländin (2014) claims that in order for something to be labelled as a master suppression technique, there must be some systematic agenda, pattern or underlying structure relating to its use in a specific situation. In addition, the victim of such techniques must be affected, either directly or indirectly. For example, if somebody degraded female politicians in general relative to male politicians, that would be 'solely sexist and silly' (Ländin, 2014, p. 13).

Classic master suppression techniques

In this section we outline the five classic suppression techniques of Ås (1978), with reference to the work of Nyberg and Wiberg's (2014), Eksvärd (2011) and Ländin (2014).

Making invisible

This technique involves conveying to others that a person or their opinions are not interesting or important. The reasons for applying this technique may differ and could include habit, ignorance or a wish to make a person feel insignificant (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014). It can take obvious or subtle as well as conscious and unconscious forms, but typically results in victims questioning their own value. This is the suppression technique that people are generally most familiar with (Ländin, 2014).

Ridicule or reducing

This technique involves suppressing a person through mockery of something that he or she says or is, for instance by attacking their pronunciation, laughter or physical appearance (Ländin, 2014). An example could be likening a group of women to a flock of hens, or addressing an adult as 'young lady' or 'young man' to suggest that they are behaving like a child (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014; Ländin, 2014).

Conscious-disclosure of information

More than 400 years ago, the British philosopher Francis Bacon coined the saying that 'knowledge is power' which is as true today as it was then. Having access to knowledge or information that others lack can be a source of power, and people sometimes purposefully keep others in the dark (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014). The non-disclosure of information may be unintentional (for example if a person is absent from a meeting), or due to the sharing of information in informal contexts where a particular individual isn't present. This is a technique typically applied by individuals to position themselves in a work-related hierarchy (Ländin, 2014).

Double punishment

This suppression technique often creates the feeling that whatever you do is wrong (Ländin, 2014). For example, someone could be criticized for being insufficiently involved in a child's upbringing due to extensive work hours, while simultaneously being criticized at work for not taking it seriously enough. This technique means that a person lets others define his or her character, while at the same time placing too much emphasis on doing the 'right' things (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014; Ländin, 2014).

Imposition of guilt and shame

If you experience feelings of guilt and shame even if you've done nothing wrong, you may be a victim of this technique. It is often experienced in conjunction with another technique, such as withholding of information or ridicule and reducing (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014). When applying this technique, the perpetrators express themselves in ways that make a victim feel ashamed, either for who they are or for their own unfortunate situation (Ländin, 2014). It is often used in connection with sexual harassment, such as when a woman is sexually harassed and is later told that her choice of clothes or behavior might have caused the situation. Instead of focusing on the perpetrator's offense, the blame falls on the victim (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014).

Semi-classical master suppression techniques

A few years after defining the five classical master suppression techniques, Ås (1978) came up with two additional techniques that she labelled semi-classical. This was done to clarify the differences between different classical techniques and to develop a better understanding of master suppression (Ländin, 2014).

Objectification

This technique involves reducing someone to an object by discussing or commenting on a victim's appearance in situations where it is irrelevant (Ländin, 2014). No matter what skills a victim has or shows, he or she is degraded into being nothing more than an object (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014, Ländin, 2014). For example, someone might objectify a leading politician by judging them on their dress or hairstyle rather than their skills or ambitions (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014).

Violence or threats of violence

This might seem like a technique that would be hard to miss when it is applied, but that is not always the case; a person might feel threatened even if the threat is not clearly stated (Ländin, 2014). The exertion of strength and superiority against an individual in order to suppress them is the least subtle form of this suppression technique. Hostile glances or gestures that hint at aggression are subtler, but may be just as unpleasant (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014).

Modern master suppression techniques

The nine techniques outlined in this section are used to acquire power over others and can be seen as additions, or further developments of, the classical and semi-classical techniques described by Ås (1978). Eksvärd's (2011) and Ländin's (2014) contributions provide an improved understanding of our behavior in situations of power play and warrant inclusion even if they overlap with or resemble the techniques discussed above in some respects.

The projection technique

The projection technique is manifested in situations when a person is criticized and responds by criticising the person who delivered the original critique rather than addressing their points. Everyone has probably experienced responses that begin along the lines of "but you did..." as a way of avoiding having to address the actual content of a critique. These situations can easily occur in close and personal relationships, which is the context in which the technique is most commonly applied (Ländin, 2014).

The compliment technique

This is a very subtle method that can be difficult to recognize. The perpetrator starts by complimenting the victim and then suddenly asks for a favor or service. It can be difficult for the victim to know if the compliment was meant honestly or was just a tool for manipulation. It is thus important for the victim to be able to interpret the context in which the compliment is given to find out which is the case (Ländin, 2014).

The stereotype technique

A stereotype is a simplified and general idea of the characteristics that members belonging to a specific group possess. Groups that may be stereotyped include people of particular ethnicities, genders, sexualities, occupations, or appearances (Eksvärd, 2011), and the perpetrator degrades the victim by reducing them to the stereotypical characteristics that they attribute to the relevant group. This is a suppression technique because the subject is judged on factors that may be completely irrelevant (Ländin, 2014).

The martyr technique

This technique is used to acquire power and manipulate others by creating feelings of guilt. A martyr positions him- or herself as a victim to obtain what he or she wants; an example would be a person who, after receiving constructive criticism from a colleague, makes that colleague feel guilt by saying 'you still think I am doing it wrong' (Ländin, 2014).

The exclusion technique

This involves a perpetrator excluding an individual or group from a situation. It could, for example, consist of an individual not getting any attention in a conversation or not receiving an invitation that everyone else gets. This makes the victim feel insignificant, independently of whether the perpetrator acted consciously or unconsciously. This domination technique is similar to the classical technique of making invisible, but Ås' (1978) technique is more heavily linked to unconscious behaviors (Eksvärd, 2011).

The hierarchy technique

One technique for suppressing others is to make use of hierarchical superiority. This could involve emphasising a superior work title in a context where it isn't called for (Eksvärd, 2011). For example, during a discussion of two conflicting opinions, one of the involved individuals may emphasize their rank, even though it is completely irrelevant to the discussion. The opposite approach could also be taken, although that would arguably be an example of the martyr technique instead.

Time technique

This technique involves dismissing someone's opinion because of his or her age. While age or experience can affect the value of someone's opinion in some settings, this is not always the case. Individuals applying this technique choose to equate competence with life experience when it is to their advantage, or alternatively, to regard competence in a particular area as having a "best before" or "not-valuable-after" date (Eksvärd, 2011).

The relativisation technique

This technique is a way for a perpetrator to use stories and experiences to diminish a victim's story (Ländin, 2014). It is manifested in situations when a victim tells a story to someone and the perpetrator responds by telling a similar story to 'one-up' the victim's story. The famous 'Four Yorkshiremen' sketch performed by the comedians of Monty Python is based on an exaggerated and over-explicit example of this technique (Monty Python - Four Yorkshiremen, 1967).

Nuances of classical techniques

The preceding sections described the classical and semi-classical suppression techniques presented by Ås (1978), as well as other suppression techniques presented by Ländin (2014) and Eksvärd (2011). Nyberg and Wiberg (2014) have expanded on these techniques by defining ten potentially suppressive nuances. These nuances were identified by studying the comment fields of public individuals, and are not necessarily unpleasant; indeed, they do not necessarily represent an attempt to exercise power over others, and can in some situations be seen as rather casual and uncomplicated.

Social denial

Social denial involves things such as consciously avoiding liking something emerging in comments and updates. It is done for various reasons, such as to avoid drawing attention to certain persons (e.g. competitors). By using this technique, the perpetrator distances himself or herself from that person and his or her posts or comments, and thereby shows that he or she does not agree with a post or find it sufficiently interesting to confirm.

This nuance can be connected to Ås' (1978) technique of making invisible, and could in a similar way reduce the sender and indicate that he or she is not worthy of attention (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014).

Delayed and ambiguous confirmation

Unlike social denial, this nuance is about engendering a feeling of insecurity in the victim by waiting or pausing in conversations. This can be used when a post is considered controversial, too personal, or boastful, and is manifested in delayed or ambiguous confirmation. This includes giving pity likes, i.e. giving confirmation to show sympathy rather than to express appreciation. This nuance also encompasses giving a 'thumbs up' or a like to posts made by people who do not seem to understand language norms, rules and how to behave. Pity likes are a so-called ambiguous phenomenon because they cannot really be interpreted without considering who actually wrote a post and its content (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014).

Confirmation to make oneself visible

This nuance is about how some individuals showcase themselves for others who are not necessarily part of their networks. By liking a post, a user expresses their confirmation, which is visible to both the person who made the post and to others. In such cases, egoistic motives drive a behavior that at first glance could be interpreted as something completely different. This nuance is not applied to suppress others but to promote oneself and increase one's social status (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014).

Share to visualize oneself

The fourth nuance is also about self-promotion, but involves sharing images, links and information posted by others to showcase and highlight one's own status. By sharing, a user seeks to communicate something to others that will make them be seen in a more favorable way. For example, they may wish to portray themselves as caring about the world or being knowledgeable in certain areas. People applying this nuance typically take positions in public debate or politics and strive to be the first to share content, which makes it more likely that others will subsequently share or comment on that content. This nuance focuses on boosting oneself to achieve social promotion rather than degrading others (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014).

Overtaking threads and conversations

This nuance involves attempting to take focus and social status from others (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014). It may entail trying to shape topics to better fit one's preferences or taking over other peoples' threads. For example, a person may post or share a funny picture and the perpetrator could respond with a reducing or ironic comment. If the perpetrator is successful, the focus of the thread will shift from the original post to their comment. While the intent need not be hostile – the commenter may just be trying to be funny - the effect is suppressive (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014).

Showing loyalty through confirmation

The sixth nuance is about showing loyalty to others by confirming them in order to gain a personal advantage. For example, if an individual likes a post made by someone in a higher position in the social hierarchy, this creates an association between the two that is visible to others. It also shows that the person who liked the post belongs to the fan base of the person who made it, and is a part of their social group. By extension, it shows who is not part of the group. This technique represents a way to increase social status and is not exactly a suppression technique, even though people who feel excluded may suffer to some extent (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014).

Trespassing in places and flows

This nuance is about adding messages or tags to posts or comments to encourage others to chime in. When someone addresses something (by adding messages or tagging) to somebody who was not originally part of a discussion, it will show up on that person's wall or media flow. This could occur if a person comes a cross an interesting discussion and chooses to tag another person and seek their opinion or reaction. This can be done by whoever originally made the tagged post, but also by others. This can be suppressive if someone is invited to a discussion that they don't want to participate in, or if someone invites others to participate in a discussion against the wishes of whoever made the original post (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014).

Creating exclusive affiliations through tagging

This nuance is about how an individual can connect other people to images or messages by tagging in order to create an exclusive affiliation between him/her and them. The tagged people are included, while everyone else is excluded. Another way to demonstrate an affiliation is to check-in with someone via Facebook when arriving at a site or event. This nuance is used to show affiliation and to exclude others; it is thus a way to demonstrate a position above others and induce feelings of inferiority (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014).

Creating uncertainty through ambiguous messages

This nuance is about adding hidden meanings to messages and comments to induce feelings of discomfort in others. This can be done by using smileys and emoticons, but also through elaborate formulations that cause confusion. Clever uses of emoticons (for example) can say much more than words and, if properly used, can convey hidden messages. The use of ambiguous and hidden messages can create discomfort, depending on how the recipient interprets the message (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014).

Beautifying oneself

The last nuance is about how individuals embellish their lives, for example by editing pictures or using filters. Applying filters to photos posted on Instagram or deleting unwanted details in images posted on Facebook has become increasingly common and is a way to beautify oneself. This can create discomfort in others by allowing people to give a misleading impression of being better off than they are. While it is perhaps farfetched to say that this nuance can be used to suppress others; it can certainly make them feel discomfort or degraded (Nyberg and Wiberg, 2014).

Summary

The preceding section outlines the classical and semi-classical suppression techniques described by Ås (1978), Eksvärd's (2011) and Ländin's (2014) modern suppression techniques, and the nuances of suppression techniques described by Nyberg and Wiberg (2014). These techniques, which are listed in Table 1, form the basis of our analysis; we chose to describe them because it is necessary to understand them to follow the subsequent analysis. To our knowledge, the occurrence and nature of suppression techniques on open social media forums have not previously been explored. We therefore sought to bridge this knowledge gap, and decided to keep an open mind about the use of these techniques - we assumed that they could all occur until proven otherwise.

| Classic master suppression techniques | Modern master suppression techniques | Nuances of classical master suppression techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Making invisible | The projection technique | Social denial |

| Ridicule or reducing | The compliment technique | Delayed and ambiguous confirmation |

| Conscious disclosure of information | The stereotype technique | Confirmation to make oneself visible |

| Double punishment | The martyr technique | Share to visualize onself |

| Imposition of guilt and shame | The exclusion technique | Overtaking threads and conversations |

| The hierarchy technique | Showing loyalty through confirmation | |

| Semi-classical master suppression techniques | The time technique | Trespassing in places and flows |

| Objectification | The relativisation technique | Creating exclusive affiliation through tagging |

| Violence or threats of violence | Creating uncertainty through ambiguous messages | |

| Beautifying oneself |

Methodology

In order to study suppression techniques on Facebook, we chose to use a netnographic approach for data gathering (Kozinets, 2011), were inspired by a pragmatic-interactional approach (Kozinets, 2011), and used qualitative content analysis to evaluate the gathered data (Graneheim and Lundman, 2004). In this section we will describe these approaches and outline how they were used in our study and why.

Netnography

Netnographic research combines elements of ethnography and anthropology, and involves six stages: planning of research, entry into the field, data collection, interpretation, ensuring that ethical standards are followed, and presentation of the research (Kozinets, 2011). The most frequently used data gathering technique in both ethnography and netnography is participatory observations, but we chose a different approach to minimize the risk of influencing the observed behaviors. We therefore decided to examine our selected forum, Facebook, as hidden observers, an approach that is highly compatible with netnography and sometimes even preferable, particularly when the mechanisms being observed are of a sensitive nature (Langer and Beckman, 2005). The use of hidden observations is somewhat controversial, however (Bowler, 2010), and so measures were taken to protect the integrity of the studied population. Specifically, we decided to anonymize the open forums, as recommended by Langer and Beckman (2005), as well as the individuals active in them. We use pseudonyms when referring to individuals in our text and have slightly altered the quotes presented to confound searches that could otherwise lead to the identification of the individuals behind them. We thus adhere to the principles outlined by Ahrne and Svensson (2011) who state that content that could lead to identification of particular individuals should not be published.

A pragmatic-interactional approach

The pragmatic-interactional approach to netnography (Kozinets 2011) has in our case contributed to a deeper understanding of how social power plays unfold on Facebook. This approach combines the methods of George Herbert Mead (1938) and Ludwig Wittgenstein's practical language philosophy (1978), and suits our study well because it does not require knowledge about who is saying or doing what, and instead focuses on identifying the interactions taking place in the selected community. Another important aspect of this approach is that it enables the researcher, in the analysis, to see the visual, graphic, audio-visual and auditory aspects of the observed behavior, which is not generally the case in analyses of netnographic data. The adoption of the pragmatic-interactional approach primarily influenced the way in which we obtained our observations rather than our analysis of data. It was appropriate for our purposes because we are interested in the actual comments (manifestations of suppression techniques) and their meaning, significance and appearance rather than the individuals who made the comments.

Qualitative content analysis

We used qualitative content analysis to analyze our gathered data (Graneheim and Lundman, 2004). This was done because our objective was to understand how and why things were done rather than to gather statistical data. Qualitative content analysis focuses on identifying differences and similarities in the data, and facilitating the emergence of different categories and themes. The data are divided into its manifest content and latent messages, where the manifest content is what is expressed explicitly and the latent message is what can be read between the lines (Graneheim and Lundman, 2004). Graneheim and Lundman (2004) further argue that the context is important when creating categories and themes because it can support the creative process. That is to say, the data are linked to their context and should not be considered autonomous. We have used the following concepts from qualitative content analysis: meaning units, condensed meaning units, codes, subcategories, categories, and themes.

Sampling

To maximize our coverage and ability to find relevant contexts, we chose a number of open forums on Facebook for observation. Through this strategic selection we aimed to gather as much relevant data as possible relating to our research objective. We also chose to limit ourselves to groups that use Swedish as their main language, and to focus on four types of groups: politics, news, public persons, administrative authorities and organizations. Finally, we only considered groups having forums that enabled discussions.

Execution of the study

This section details the steps we took in implementing our study, which were based on Kozinets' (2011) recommendations for netnographic research and our decision to conduct hidden rather than participatory observations.Netnographic study

Our observations covered all of the master suppression techniques outlined in the previous section, but we were also prepared to include other, previously unrecognized forms. When observing Facebook, we chose to limit the study to open groups that can be viewed by anyone, regardless of whether they have a Facebook account. The netnographic study was conducted according to Kozinets' six-stage model (Kozinets, 2011), with the exception that we conducted hidden rather than participatory observations.

Data were collected over a period of two weeks. The process was relatively simple: the selected groups were examined thoroughly, post by post, to find comments that were considered to employ one or more of the master suppression techniques or nuances described above. We captured archive data, which in this case meant screenshots of the conversations in which suppression techniques were identified, and also made field notes. The collected data were then categorized according to which suppression technique or nuance was used, and the context from which they were retrieved.

In total we estimate that around 1000 posts and topics from approximately 30 different open forums were observed. The numbers of comments in these posts and threads ranged from 0 to about 100. From these comments, we selected 80 that appeared to include uses of suppression techniques or nuances.

Qualitative content analysis

Meaning units were selected, condensed and coded as part of the analysis. The codes were divided into subcategories named after the suppression techniques and nuances that we could detect, and the subcategories were then sorted into broad categories on the basis of their differences and similarities. This resulted in the emergence of themes. Table 2 presents some representative condensed meaning units, codes, sub-categories and categories from our content analysis. Meaning units have been removed (and replaced with the text Direct quote) to prevent identification of their authors. The phrase SD-people refers to supporters of a political party in Sweden, hen is a Swedish word used to avoid gender markers such as him or her, and Carola is a famous Swedish artist.

| Meaning unit | Condensed meaning unit | Code | Sub-category | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct quote | Typical SD-people to write inappropriately | Generalisation | Stereotype | Mockery |

| Direct quote | West-coasters... | |||

| Direct quote | [Reply to a political comment] You're so cute Sara, beautiful eyes ;) | Ignore opinion, comments looks | Objectification | |

| Direct quote | Hen means 'hen' which maybe suits to describe you? | Analogy | Ridicule | |

| Direct quote | You are as immature as a baby | |||

| Direct quote | If you are displeased do something about it, don't just whine like babies | |||

| Direct quote | X uses diluted quotes and a rhetoric that doesn't solve the problem | Come up with something new | ||

| Direct quote | It is spelled like this and even if it was you're still wrong | Learn how to spell and study more | ||

| Direct quote | Little Karl. Think before you write, use your brain | Little you, use your brain | ||

| Direct quote | Check Carola's profile and you will understand | She is not very smart |

Results

In this section we present the results of our netnographic observational study. We focused primarily on the occurrence of suppression techniques on Facebook, and present the results of the qualitative content analysis in the form of categories.

The netnographic observational study

Below we present the suppression techniques we were able to observe in our study of Facebook. We provide examples of situations containing instances of suppression techniques, and explain why the comment (or comments) had suppressive effects. For the sake of clarity, we have chosen to present our results in relation to the subcategories for each suppression technique that was observed. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the techniques that we were unable to observe. When excerpts are provided, they have been translated from Swedish to English.

Ridicule and reducing

Our results indicate that ridicule and reducing, in different forms, were the most common suppression techniques on Facebook. The most typical form was to liken people (or, in certain contexts, their opinions), to ridiculous things such as hens or babies to communicate that these people or opinions should not be taken seriously.

Another version of the technique was to diminish someone's experience or claims as being insignificant. In one instance, a public person posted a picture from Paris on his or her profile page with an accompanying text recommending followers to visit a particular restaurant. The comments that followed reduced the post and labelled the suggested restaurant as nothing more than a 'tourist trap'.

Another form involved having fun at the expense of others. One example of this was found in the comments on a post made by a young man who defended women and feminism in a long comment. Two of the responses were clearly suppressive, making fun of the original post and the person behind it. One comment stated that we (men) had lost one to the feminists, referencing the loss of a person in combat. Another comment targeted the young man directly by saying that there is little use in making such posts because they wouldn't lead to him getting laid – a clear attempt to diminish his comment by presenting it as something it was not.

Finally, we saw another instance of the technique when a person was tagged to posts that he or she had no affiliation with. In one example, a single individual had tagged several people to an event (a well-known local running race) and asked the tagged people if they were interested in participating. One of the tagged individuals then questioned, in a ridiculing manner, why a specific third person had been tagged. This was interpreted as the second person mocking the third by questioning his ability to participate in the competition.

Making invisible

We could only identify one instance where this technique was applied. A public Swedish politician made a post about having met another politician from an ideologically similar party in Austria. The politician was supposed to participate in a debate later that day, and a follower asked a question about a current issue in Swedish politics, which the politician replied to. The follower then asked a second question and again received a response. This was followed by two separate questions from the follower, separated by an interval of a couple of hours. The politician did not answer these questions, and the follower decided to end the interaction by complimenting the politician on his performance during the debate. The politician, indicating that he had seen the previous posts but decided not to respond, liked the compliment. Thus, both the questions and the follower asking them were made invisible.

Double punishment

This is a technique that is typically applied over time and can hardly be seen in comment fields on social media. In a well-known case in Sweden where the police had committed an error, comments were made that questioned the decision not to punish the policemen for what they had done as well as for apologising for it. Consequently, their behavior was subject to criticism whether or not they apologized, even though they had clearly made a mistake; no matter how they handled the situation, they were considered to have done so wrongly.

Objectification

This technique typically involves responding to a serious statement made by someone (often a woman) and diminishing it by addressing their looks or gender rather than the substance of their point. In one example, after making a defensive comment about a public person, a woman received a response saying that she was cute and had beautiful eyes. Because her appearance was irrelevant in that context, the comment was regarded as a way of diminishing her opinion, even if it was sincerely intended as a compliment.

Imposition of guilt and shame

This technique was manifested in the form of users blaming other individuals for something even when those individuals had done nothing wrong. In many cases this was due to the parties having different opinions about what was interesting and relevant. In one case, where a public person had posted a picture with accompanying text asking if they should cut their hair, a follower, Tyko, responded by saying: 'Linus, give it a rest! Are you really making a status update about your hairstyle? Could you tell us what you are having for dinner as well? Disappointed.' It appeared that Tyko really appreciated and respected Linus, but had lost his respect for Linus because he (Linus) was typically critical of superficial posts. Tyko thus placed guilt on Linus through his comment.

The relativisation technique

On Facebook this technique was manifested through, first and foremost, users bragging about and glorifying their own everyday lives. We found several examples of people trying to outdo each other by constantly showing how much better their lives were. One example of this behavior is a picture of a nice house, taken on a glorious day and posted by a public person. The person also added text to emphasize just how good his or her life is. Many of the followers who commented on the picture responded by uploading their own pictures in attempts to outdo the initial post.

The stereotyping technique

Generalisations on Facebook are common. As a consequence, it was no surprise that this technique was seen in a variety of contexts, often with the objective of mocking someone by providing a stereotypical affiliation. Individuals were labelled by others saying that the behavior was typical of one group or another, for example by saying 'typical west coaster' or 'typical Swedish democrat voters'. A clear example occurred when a public person (John) wrote:

To everyone (mainly people who have studied at the tough school of life and have a fierce wolf in their profile picture) who comments that I am rich and fortunate, and that it is the old and the poor who pay for immigration, I ask this: if I and the rest of us in the PK [political correct] elite paid for everything, would you then open your arms?

John is making a generalisation about Facebook users who state in the education section of their profile that they were educated in the tough school of life, and concludes that it is people in this group who criticize him the most.

Hierarchy technique

Only one instance of this technique could be found in our data. A user had decided to comment on the pronunciation of a public person when he/she talked about his/her new podcast. The follower then chose to first give an encouraging comment and immediately after give suggestions on how to better pronounce certain words. The user never says explicitly that he or she is a language expert, but indicates the possession of knowledge in the field. The comment does not focus on the content of the podcasts but rather the form, and shifts the focus of the discussion to him or herself rather than its original subject.

Time technique

Users questioning the age of others and diminishing their opinions manifested the technique. We were able to see a clear pattern of younger people mocking older people in order to devalue their views. Two examples were: 'says you who grew up during the Second World War' and 'you're too old to discuss new technologies'.

Creating uncertainty through ambiguous messages

It was hard to find instances of this technique in our data. We were able to discern its use in the way people wrote and made use of punctuation and emojicons, but we couldn't perceive the underlying or hidden meanings or purposes. Creating uncertainty through ambiguous messages was also found to have strong links to the use of irony.

Showing loyalty through confirmation

Discussions occur continuously on open Facebook forums, and disagreements emerge frequently. In such cases, one or more groups are often formed, whose members back each other up by responding to one-another's posts. A notable example of this occurred when an individual (Sven) decided to show his loyalty (through confirmation) by defending a public person who was challenged by a woman (Stina). Sven says: 'the guy has money, thousands of followers and a career, what exactly do you have Stina?'

Beautifying oneself

Facebook is full of pictures and posts where users embellish their lives and existence, but it turned out that this did not always have suppressive effects on others. However, when combined with other techniques, such as relativisation, suppression did occur. In several situations, when we focused specifically on public persons, we discovered that many followers were trying to make their lives appear similar to or even better than that of the public individual. They often wanted to glorify their lives by uploading pictures and making comments saying that their lives were even better.

Overtaking threads and conversations

This is a technique that was frequently seen in very diverse contexts. It was manifested in people asking questions that had already been asked, and a concrete example was found on a news forum, in a thread about an article discussing an individual who had experienced racist harassment. Rather than addressing this topic, one use noticed and mentioned her resemblance to the actress Angelina Jolie. 'Is it just me who thinks that she is a clone of Angelina Jolie? Strange! Haha.' This user, whose name was John, received 49 likes for his comment, causing it to rise to the top of the discussion and shifting its focus from harassment issues to the people's physical appearances.

Trespassing in places and flows

In public forums on Facebook, it is difficult to know what is an intrusive comment and what is just a regular one. However, we saw that intrusions in public feeds could be directly linked to several other suppression techniques. We saw several situations in which ridiculous images were used to suppress others. These were typically playful images that were linked to someone's flow, creating intrusions that enabled the use of further suppression techniques.

Delayed and ambiguous confirmation

This technique was typically seen alongside the technique of making invisible. There were frequently clear delays between posts being made and replied to, as confirmations of individual's questions did not receive responses until several hours later. In this way, the time stamp feature for comments on Facebook enabled suppression to take place.

Non-observed suppression techniques

The suppression techniques that we outlined in the previous sections were categorized as classic suppression techniques, semi-classical suppression techniques, modern suppression techniques and nuances of suppression techniques. We found no sign of the following techniques and nuances: conscious disclosure of information; violence or the threat of violence; the exclusion, compliment, martyr, or projection techniques; social denial; confirmation to make oneself visible; sharing to visualize oneself; and creating exclusive affiliations through tagging. The apparent absence of these techniques is discussed in more detail later on in the text.

Results of the qualitative content analysis

Table 2 illustrates how we categorized condensed meaning units, codes, subcategories and categories. By analyzing conversations in their entirety together with our background knowledge of how the suppression techniques are manifested and our interpretations of the deferred messages in the texts, we could use codes to situate texts in subcategories that were then organized into categories based on their differences and similarities. We could then formulate a theme based on these categories; the chosen theme was defined as the exercise of power on Facebook. This theme is something that we had in mind since the start of our study because previous studies had treated suppression techniques as unpleasant tools for obtaining power. By applying qualitative content analysis, we were able to confirm that these techniques are indeed used to this end.

We could however not apply this method to all of the observed suppression techniques because the contexts of certain conversations provided no meaning units for analysis. This was the case for techniques such as making invisible. In other cases, such as for the nuance beautifying oneself, the situation was only depicted with images and so there were no meaningful units to analyze.

Analysis

Given our pragmatic-interactional analytical approach, we chose to regard comments featuring suppression techniques as social acts in a larger social power play. These (often subtle) techniques that create both discomfort and power are something that we see as conscious acts, and if we view Facebook as a game plan then these suppressive acts correspond to movements of playing pieces. Such movements could create completely new situations and must therefore be analyzed as such. Given this perspective, the movements of the playing pieces represent the most interesting unit of analysis, i.e. the uses of master suppression techniques and their nuances in comment fields. This perspective is related to the view of power as contextual power (Sköldberg, 2014). In other words, every situation where power is exercised can only be understood in the context in which it unfolds. To reach this understanding, it is vital to comprehend the micro techniques (in this case, suppression techniques) that are used in the power play. From this perspective, we have developed our analysis and discussion. Our qualitative content analysis forms the basis for the model we present, and through our observations we explain how the social context of Facebook unfolds and why.

Why aren't suppression techniques visible?

As noted in the results section, we could not detect any instances of some suppression techniques in our study. There are several possible reasons for this. First, some of these techniques and nuances are probably difficult to capture through observations. To detect their occurrence, we would have had to ask perpetrators specific questions about behaviors that most people would probably prefer not to talk about. This would be the case for techniques such as the nuance of sharing to visualize oneself. Without being able to ask questions directly, we cannot say what the actual purpose behind an instance of sharing really was.

Another possible reason for our failure to observe certain techniques or nuances is that they are rarely applied in the studied context. This is probably the case for the compliment technique, which is most likely to be common among individuals with established relationships due to its dependence on an understanding of the other person's competence. Given the decision to study open Facebook groups related to politics, news, public persons, administrative authorities, and organizations, this specific technique, and possibly others too, were difficult to observe.

A third possible reason for failing to observe some techniques is that they may not have effective suppressive effects on Facebook. This may be the case for violence or threats of violence, for instance. Since suppression techniques are always subtle, this technique is associated with violence or threats that are not explicitly stated or executed, and are therefore hard to observe in the chosen context.

We initially decided to see Facebook as a network that creates opportunities to execute suppression techniques. The scope for users to do this is clearly related to what we call Facebook's room for action. All users can execute suppression techniques, but they don't have to do so in the context of a conflict. However, when these techniques are put into practice, they become a way for the perpetrator to achieve superiority over others, for example in a discussion. The room for actions relating to suppression techniques thus enables users to establish superiority over others through these techniques (Sköldberg, 2014).

Although it isn't always possible to determine who is playing a leading role in a digital social hierarchy, it is possible to identify individuals who are trying to attain such a role. This ambition is achievable because all users are connected through the medium, illustrating the breadth of the room for action provided by Facebook.

In situations where we could observe suppression techniques being applied, we could almost always also see that the relevant power relations were asymmetric, or moved in both ways. One or several parties executed power over others, but as we have previously described there were also instances of symmetrical power where one user had the upper hand.

Technology and power

Technology plays an important role in how power plays unfold, in both online and offline contexts. Our observations have given us a more fine-grained understanding of the technological possibilities offered by Facebook. However, before we began our study we assumed (based on related research) that the technology (i.e. Facebook) was a platform on which power plays would be widespread and master suppression techniques highly visible. Since all users can communicate with one another, we expected to find a game plan filled with subtle master suppression techniques. Moreover, Facebook requires users to create non-anonymous accounts where they represent themselves; we assumed that this would limit the extent to which users spoke openly and freely with one another. In other words, it was expected that users would feel limited by the fact that those they engaged with knew who they really were. Our observations did not bear this out.

We observed a much harsher and crude context in which subtle power plays were largely overshadowed by Internet hate. This may be partly due to the online disinhibition effect (Twenge, 2013), which makes it possible (and to some extent, likely), that our expressions of opinion and behavior will be altered simply because they occur online. This is important to when considering the results of our observations. We believe that some of the inhibitions we experience in offline conversations are relieved when we become representations of ourselves online. This might explain why some people seem to be more verbal and negative in their communication on Facebook than they are normally. This phenomenon was discussed earlier in this paper, in relation to online disembodiment (Zhao, Grasmuck and Martin, 2008).

Geography is another potentially relevant factor. Technology does not have geographical boundaries, which allows people to comment on and discuss various topics, sometimes in negative and suppressive terms, without running the risk of facing consequences in a real life context. Accordingly, one might feel more secure and daring in an online than in an offline context.

Categorisation model

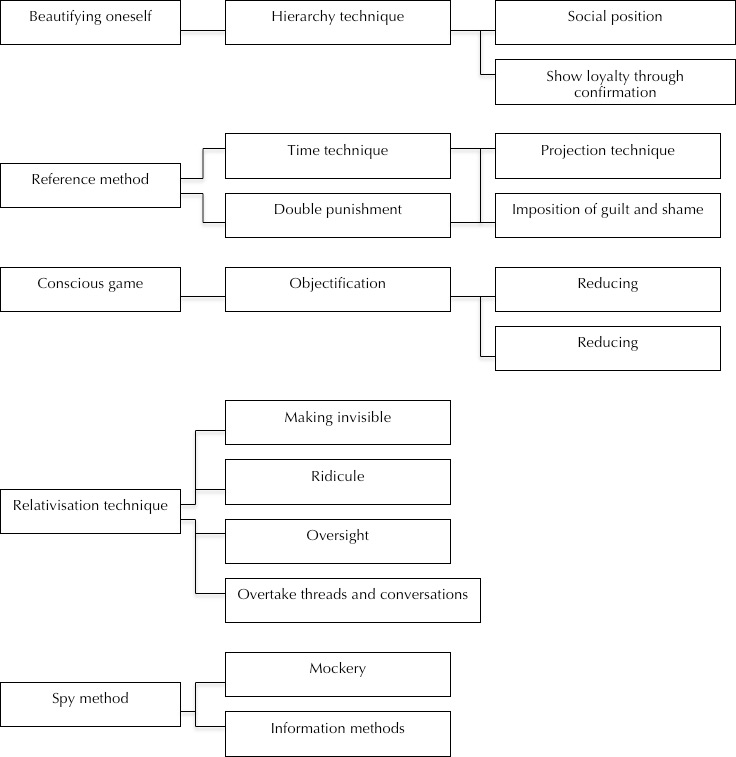

Based on related research on suppression techniques and their nuances, as well as our results, we have created a model (Figure 1) of these techniques and their use on Facebook. The techniques and nuances are divided into different categories to establish a schematic and simplified model that only includes those techniques and nuances that were identified in our study as well as some new nuances that we defined on the basis of our results. The nuances are divided into different groups (oversight, mockery, conscious game, social position and information methods), which are named for their characteristics or lowest common denominators. The model was created on the basis of a content analytical categorisation of the differences and similarities of the techniques and nuances. By using the model, we can more effectively show that these suppression techniques are found on Facebook and how they are connected. In the following section, we describe the groups and the subgroups that constitute the model.

Oversight

This characteristic includes the technique of making visible, which is manifested through the techniques of relativisation and overtaking threads and conversations. We have named the group oversight because we regard it as the characteristic that best describes the overall aim of these techniques.

Mockery

This includes ridicule and reducing. These techniques could be considered synonymous given their descriptions and execution, but since two different authors defined them, we choose to keep them separate. We also observed the techniques of exclusion and objectification being used to ridicule and reduce others, so they too are included in this group.

Conscious game

The projection technique and double punishment have in our observations had a dormant message relying on imposition of guilt and shame on others. Conscious game was therefore selected as the name for the group.

Social position

Social position is a divided group with one branch containing the hierarchy and time techniques, and another containing the techniques of beautifying oneself and showing loyalty through confirmation. Our observations and analysis indicate that all these techniques are used in situations where the exercise of power is connected to either the victim's or the perpetrator's social position.

Information methods

Information methods include nuances of master suppression techniques that we have observed and named. One of these is the reference method, whereby the perpetrator refers to a resource that can strengthen his or her arguments. This method is in no way unique to Facebook, but is very well suited for online contexts because online information is very easily found and accessed. The spy method is a technique whereby a perpetrator searches for information about a victim, and then uses it to suppress him or her. This method is especially well suited to Facebook because the platform is built upon a lot of individuals sharing personal information with others.

Figure 1. Categorisation model: visible nuances and master suppression techniques used on Facebook.

Conclusions

We have tried to develop an improved understanding of the use of suppression techniques on Facebook in particular, and in social power play online in general.

Our findings show that master suppression techniques are employed in open forums on Facebook, but they are not nearly as common as we originally expected. The climate in the open forums was usually surprisingly crude, and the comments were more closely related to net hatred than to the subtle power play we call suppression techniques. We generally observed more direct and harsh insults than creative and subtle ways of acquiring power. This may be due to the climate of public forums, as well as the lack of face-to-face encounters between perpetrators and victims, which allow individuals to relax their inhibitions. Very different situations may occur in private conversations or flows.

One of the main theoretical contributions of this work is the delineation of a set of nuances of domination techniques that may occur on Facebook. These information methods require extensive access to information, which is only possible online because all information on the Web is both stored and accessible to others. Such information can thus be used by perpetrators to practice suppression techniques.

Another theoretical contribution is the model presented in the discussion. This model can be used as a basis for assessing the presence of suppression techniques on other social media platforms, and could readily be modified to incorporate new nuances of suppression techniques. It also provides a simplified schematic view of how different suppression techniques and nuances are related via common denominators, or themes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the referees for their valuable feedback and our colleague Johan Bodén for serving as our copy-editor.

About the Authors

Rikard Harr is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Informatics, University of Umeå, SE-901 87 Umeå, Sweden. He graduated with a major in Informatics and received his PhD from University of Umeå, Sweden. He can be contacted at: rharr@informatik.umu.se.

Annakarin Nyberg is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Informatics, University of Umeå, Sweden. She received her Bachelor's and Master's degree in System Analysis as well as her PhD from University of Umeå, Sweden. She can be contacted at: aknyberg@informatik.umu.se.

Marcus Berggren is a student at Berghs School of Communication, Sweden. He received his Bachelor's degree in Digital Media Production from University of Umeå, Sweden.

Richard Carlsson received his Bachelor's degree in Digital Media Production from University of Umeå, Sweden.

Sebastian Källstedt is a graphic and Web designer at ALSO Deutschland GmbH, Germany. He received his Bachelor's degree in Digital Media Production from University of Umeå, Sweden.