Untangling the building blocks: a generic model to explain information behaviour to novice researchers

Introduction and problem statement

Information behaviour is a complex human phenomenon that has among others a profound effect on all facets of work in library and information services (Wilson, 1981; Zhang and Benjamin, 2007, p. 1935). However, there seems to be a number of issues that challenge understanding of the role information behaviour plays in the provision of library and information services and why it should be dealt with in training programmes of prospective librarians.

Involvement in post-graduate teaching and supervision revealed an apparent lack of understanding of what information behaviour entails. Multiple models serving different purposes and approaches (Cole, 2013) cause confusion among novices who find it difficult to relate them to practical modules in their training programmes. Sometimes students quote Wilson’s (2000, p. 49) encapsulating definition of information behaviour without proof of understanding what it entails. Without an explanatory model including the core components they might fail to see the bigger picture comprising the relevant building blocks and their interrelationships, which bring about information behaviour.

Researchers who developed valuable conceptual frameworks over time often have a single or simplified focus (Wilson, 1981), but others take a multidimensional approach (Sonnenwald and Iivonen, 1999; Fidel, Pejterson, Cleal and Bruce, 2004).

While collecting evidence for this study, a pattern was noticed: that the different researchers focus primarily on one particular section of the information behaviour process. Niedzwiedzka (2003) confirmed that the methodological positioning of information behaviour researchers is reflected in the different sections of the information behaviour process on which they focus. For example, Wilson (1981) focused on information needs and seeking, drawing on various research fields such as psychology, sociology and decision making and the work of Bandura (1977), while Kuhlthau (1991) focused on the uncertainty and affective factors in the personal domain influenced by education. Dervin (1983) drew on communication studies and focused on information transfer, Sonnenwald and Iivonen (1999) incorporated Ranganathan’s framework for knowledge organisation in their focus on the role of context in the information behaviour process. In their paper Fidel et al. (2004) focused on human interaction in a work-centred conceptual framework (Fidel and Pejtersen, 2005) in order to inform the design of information systems.

Wilson (1999, p. 250) noted that

most models in the general field of information behaviour … attempt to describe an information seeking activity, the causes and consequences of that activity, or the relationships among stages in information seeking behaviour. These statements rarely advance to specifying relationships among theoretical propositions … but may suggest relationships that might be fruitful to explore or to test.

Zhang and Benjamin (2007, p. 1940) also agree that many studies focus on one or two fundamental components without showing conscious awareness of other components, or overlook them.

Terminology used interchangeably by various researchers is another concern (Cole, 2013; Savolainen, 2014). Some refer to contexts, components, dimensions, facets, subdivisions, or elements of information behaviour, while others view events or actions as subdivisions or elements of components (Sonnenwald and Iivonen, 1999; Fidel et al., 2004). There seems to be no consensus on whether to refer to characteristics of the different components, or to call them factors. Different viewpoints are offered as to what actually triggers information behaviour - where it starts, or whether the sequence of activities conducted is fixed or iterative, linear or non-linear (Davies and Williams, 2013, p. 554; Foster, 2004; Godbold, 2006; Niedzwiedzka, 2003; Robson and Robinson, 2013).

A paradigm shift that took place in information behaviour research around 2000, as well as advances in technology, also complicated matters (Cole, 2013, p. 5). Before 2000 the ‘field we now know as information behaviour was termed ‘user studies’ (Wilson, 2010, p. 29). The initial focus was primarily on information needs and information seeking behaviour as perceived from a library service perspective (Haglund and Olsson, 2008). The drive to establish theoretical and conceptual frameworks started with the models of information needs and the information seeking process (Wilson, 2010, p. 31). Information seeking behaviour seemed to have attracted most attention (Wilson, 1999). Many still use information seeking behaviour interchangeably with the generic concept of information behaviour (Davies and Williams, 2013, p. 548). Another fundamental aspect reflected in earlier research reports, but not necessarily identified as a core component, is the personal dimension. Descriptions of the interplay among mental constructs were addressed by Dervin (1983) and Kuhlthau (1991). Nahl (2001), in her taxonomy approach, and later Hepworth (2007) shed light on its relevancy in information behaviour.

Wilson (1999) suggested the need for a generic model in information behaviour to give a more comprehensive picture. To this end he did pioneering work, as reflected in his nested models (Wilson, 1999). He later expressed concern that few researchers had proposed changes to his early models of human information behaviour. Instead they preferred to develop their own models to serve their particular purposes (Wilson, 2005).

Building an understanding of what information behaviour entails has taken a long time and continues to evolve in addressing new phenomena that have arisen in response to changes in everyday life (Zhang and Benjamin, 2007). Wilson (1999) and Sonnenwald and Iivonen (1999) were some of the first researchers who attempted generic models that gave a more comprehensive or holistic picture of the phenomenon. More recently there were attempts to take up Wilson’s (2005) challenge to build on existing research to work towards a generic model (Burford and Park, 2014; Davies and Williams, 2013; Robson and Robinson, 2013).

Despite the lack of a general theoretical model of information behaviour, Cole (2013, p. 4) reports a fair amount of in-depth research over the past decades (1984-1998) into relevant components that can contribute to the design of a generic framework. He posits that

Information behaviour research is maturing, becoming more sophisticated as a research field. Strong theories and well-defined, generally agreed-upon concept definitions, conceptual frameworks, models, and theories form a snapshot of a research area or discipline at a given point in time.

Cole (2013, p. 5) further argues that the development of models has moved beyond straightforward descriptions of phenomena to the ability to predict and explain natural and human phenomena. This complies with Bates’ (2005, p. 3) argument that

Only when we develop an explanation for a phenomenon can we properly say that we have a theory. Models are a kind of proto-theory, a tentative proposed set of relationships, which can be tested for validity.

Since various aspects that contribute to information behaviour are addressed by the relevant models, there seems to be a number of core components without which information behaviour cannot take place. With this in mind and considering novice researchers’ weak perception of what information behaviour entails, it seems a viable option to investigate what these components are and how they fit together in a framework that could provide a more holistic picture. Since this paper is aimed at supporting novice researchers and their supervisors, it attempts to establish what has been reported on the

- core components of information behaviour,

- subdivisions or elements of each component,

- attributes of the respective elements in each component, and

- the role the interrelationships play among the relevant components.

Methodology

For the purpose of this paper it was important to establish which components contribute to a more holistic picture of information behaviour. A number of generic models by well-established researchers (Davies and Williams, 2013; Fidel et al., 2004; Robson and Robinson, 2013; Sonnenwald and Iivonen, 1999; Wilson, 1999), which followed a multifaceted approach, were selected. The models reviewed are by no means an exhaustive survey of the field, since the aim was to focus on what has been reported on the core components, their properties and relationships. None of the existing models explicitly includes all components. Other studies were consulted to obtain more detail in cases where components were covered in very general terms, or components were addressed for the first time in a generic model. A content analysis was conducted in which the selected texts were read several times to observe differences and similarities with regard to terminology for describing or identifying components, elements of components, factors, attributes et cetera. Core components were isolated and described separately. For purposes of this paper the umbrella terms component and elements were chosen to distinguish between components and their attributes or subdivisions. Related terms were acknowledged under the respective umbrella terms.

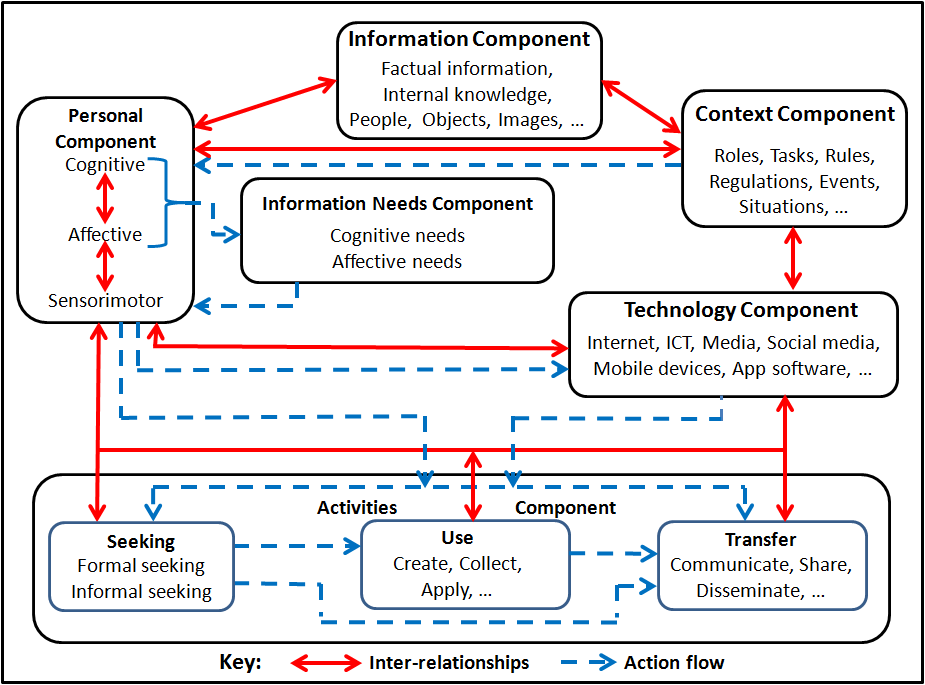

Special attention was paid to the description of relationships between the relevant components, as well as the interplay between elements of a component wherever such action had been reported. The collected information is arranged with the set questions in mind, as envisioned for the proposed model. The model is offered in the form of a simplified flowchart (figure 1), which suggests the links that exist and the interaction that takes place among the respective components.

Literature review

This literature review aimed at providing an account of earlier studies on a generic model of information behaviour in terms of its core components, subsets of the respective components and the interrelationships among them.

Core components

From the selected studies it is evident that researchers were aware that information behaviour is multifaceted and that several components are involved in the constitution of information behaviour. Researchers often drew on the work of others to uncover relevant components for a generic model. For example, Wilson (1999) integrated the models of Ellis (1989), Kuhlthau’s (1991) information search model, Dervin’s (1983) sense-making theory and Ingwersen’s (1996) cognitive model into a more general framework. Similarly, Fidel et al. (2004) drew on the research of Allen (1997), Baldwin and Rice (1997), Solomon (1999), Sonnenwald and Iivonen (1999), Lamb and Kling (2003) and Vincete (1999) for their multidimensional approach. Burford and Park (2014) strengthened their argument for the role of information technology in information behaviour by considering the viewpoints of Wilson (1981, p. 659-662; 1999), Sonnenwald and Iivonen (1999) and Ingwersen (2005, p. 130).

Diverse terminology is used to describe the relevant components. Wilson (1999) used primarily the term components, while Sonnenwald and Iivonen (1999) referred to facets and Fidel et al. (2004) to dimensions. A clear distinction is not always made between the different components and/or their subdivisions. Although there is an understanding of their interdependence, in real-life situations the components are intertwined and difficult to distinguish (Sonnenwald and Iivonen, 1999).

Not all components relevant to a generic model were covered by one study. Usually researchers addressed only one or two components for their own purposes (Wilson, 1999). Older models focused primarily on information needs and information seeking for their importance in the design of information retrieval systems (Wilson, 1981; Taylor, 1968). Information needs, seeking and use were often offered as a cause and effect combination, but where these components fit into the bigger picture was not specifically argued. Wilson (1999, p. 257) views Dervin’s (1983) sense-making model as a more complete framework for exploring the totality of information behaviour – from the context to the means through which the information need is satisfied. Although Burford and Park (2014) did not offer a model with clearly identified components of information behaviour, they indirectly admitted that information, actors, environments and the different activities and information technology are all fundamental to information behaviour.

From the selected studies the following aspects emerged as potential core components:

Information activities

For Wilson (1999, p. 249) information activities are synonymous with information behaviour. In a footnote Wilson (1999, p. 249) explained that ‘by information behaviour is meant those activities a person may engage in when identifying his or her own needs for information, searching for such information in any way, and using or transferring that information’. Later Wilson (2005, p. 49) noted that information behaviour is only observable in the information activities seeking, searching, use and transfer. Fidel et al. (2004) focused primarily on collaborative information retrieval activities. In more recent models Robson and Robinson (2013) and Davies and Williams (2013) made valuable contributions by addressing the formerly neglected activities information provision, transfer and/or communication.

Role of context

The initial generic models did not explicitly include context as a core component of information behaviour, although researchers were aware of its role. Wilson (2000) noted that

There is no indication of processes whereby context has its effect upon the person, or factors that result in the perception of barriers, nor what effects barriers have upon motivation of a person to seek information.

A lack of standardised terminology is evident in describing context as a component. Wilson (1981) referred to organisation and cultural environments, while Dervin (1983) viewed context as a situation. Sonnenwald and Iivonen (1999) identified context as the physical spaces in which people function, and also referred to their environments, organisational and socio-political contexts. Fidel et al. (2004) gave preference to the term dimension. Much later Burford and Park (2014) argued the importance of an online or digital environment, which challenged the boundaries of a physical context.

The inner experience

Although many researchers (Wilson, 1997; Kuhlthau, 1991; Dervin, 1983) were aware of the role of a person’s inner experience (often referred to as the personal dimension), it was not explicitly identified as a core component of a generic model. Fidel et al. (2004, p. 941) accepted that both the former psychological and social approaches are necessary to account for the complexity of human-information interaction in the real world.

Dervin (1983) showed awareness of the cognitive structures of the human mind. In Kuhlthau’s (1991) information searching process model, she described how emotions and feelings affected information seeking. Nahl (2001) and Hepworth (2007) made useful contributions to our understanding of the mental structures constituting the personal component. Nahl (2001) described and explained the cognitive, affective and sensorimotor processes, while Hepworth (2007) explained how inner cognitive, conative and affective experiences affect information behaviour. Davies and Williams (2013, p. 556) also recognised the role of a person’s inner experiences when they referred to a combination of cognitive, affective and behavioural processes that result in information being perceived, processed and collected by individuals.

Role of information needs

Although information needs were traditionally accepted as indispensable to the redesign and improvement of existing information retrieval systems (Taylor, 1968; Wilson, 1981), they were also closely related to inner experiences of the user. Initially there was general belief that uncertainty gave rise to information needs, but Wilson (1981, p. 7-8) posited that many factors may give rise to information needs. In addition there are needs to create understanding, alleviate uncertainty and broaden a person’s knowledge base (Case, 2012), a need for inspiration (Makri and Warwick, 2010), which can be added as attributes of an information needs component.

Diverse opinions exist about exactly where information needs originate. Wilson (1981) distinguished between cognitive needs (triggered by the performance of tasks, decision making and planning) and affective needs (triggered by a need for achievement). Dervin (1983), Kuhlthau (1991) and Nahl (2001) argued that awareness of a lack of information (inner experience) can trigger a need for information. Savolainen (2012) pointed out that information needs had been approached increasingly in the context of task performance. More recently Cole (2012) formulated a theory of information needs.

Relevancy of information

Despite the fact that the discourse revolves around human behaviour related to information, its role is seldom acknowledged in generic models. Wilson (1981, p. 3) argued that it is difficult to find a suitable definition for the level and purpose of investigation, but Solomon (1997) maintained that information becomes relevant and attains sense when it fits and satisfies the goal that is pursued. Bates (2009, p. 2381) argued the role of information when she stated that information behaviour is in essence the interaction between information and the user. Dervin (1983) saw the role of information as a human tool designed for making sense of reality. She viewed it as a bridge to span the gap between the problem and the solution to the problem. Sonnenwald and Iivonen (1999, p. 435) referred to information and information resources as tools. Robson and Robinson (2013, p. 22) identified factors relating to information and sources that were not clearly identified by other researchers. Davies and Williams (2013) did not identify information as a component, but described the impact of information on the seeker and provider’s state of knowledge and comprehension. From a philosophical approach Floridi (2015) noted that although we still have to agree about what information exactly is in everyday life, we understand information as one of our most important resources. In a more practical sense Ford (2015, p. 35) stated that information is needed to solve problems and to achieve goals.

Impact of technology

Although the contribution of information and communication technologies have not been recognised by most of the generic models as a separate component, there is evidence that many researchers (Wilson, 1999; Sonnenwald and Iivonen, 1999; Lievrouw, 2001; Courtright, 2007; Cole, 2013), were aware of its impact – primarily subordinate to, or as an attribute of context. Wilson (1981, p. 662) argued that the ‘information system’ includes technology ‘that provides techniques, tools and machines’ for finding information. Burford and Park (2014) were concerned about amorphous attention given in existing models to technology and presenting it as remote from the user. For them information technology should be de-coupled from the remote technology of information systems and be more closely associated with information actors and the context of their information behaviour (Burford and Park, 2014, p. 631).

Sonnenwald and Iivonen (1999) did not make a clear distinction, but referred to the influence of technology and tools on information behaviour. They mentioned social networks, information and information resources, and information and communication technologies that play a role in providing access to information.

The use of information and communication technologies has shown that they can change information seeking, use and communication patterns as users are increasingly offered advanced searching and communication tools (Barry, 1997). The more information technologies are available and becoming affordable, the more people get used to them and rely on them (Rieh, 2004). Their unique options offering ease of use, speed and convenience will also change users’ preferences and eventually information use habits. However, the prescribed ways in which they are used require appropriate skills from prospective users in order to achieve the desired outcomes. In this respect information and communication technologies can either enhance or control the flow of information. Hence Lievrouw’s (2001) view that information technologies become either bridges or barriers.

Burford and Park (2014) argued that apart from providing access to information, there is evidence that technology and tools are also enhancing information use and communication activities. They focused primarily on the role of information and communication technologies and described in more detail the attributes and usefulness of mobile devices and digital information. They argued that advances in mobility of technology become a new fundamental characteristic of human engagement with digital information, and context becomes multi-dimensional, undetermined and fluid. The user is no longer restricted to location or environment and context becomes less definable (Burford and Park, 2014).

Elements, attributes, events subordinate to components

From the selected studies it was clear that researchers were aware that certain elements, attributes, events, processes, or factors subordinate to components could affect information behaviour. However, these were not always assigned to a specific component. Fidel et al. (2004, p. 944) believed that each dimension (psychological, organisational, social) includes a host of attributes and factors, depending on the purpose or method of study, and that they belong to different dimensions and interact simultaneously. The following sections reveal how the respective researchers reflected on the elements of the different components.

Elements relating to context

Wilson (1981) referred to tasks and processes of planning and decision making that are among the principal generators of cognitive needs. Sonnenwald and Iivonen (1999) identified goals, processes, tasks (including subtasks or activities), rules, or norms present in the work-based context. Dervin (1983) referred to time and space as being part of context in a broad sense.

Robson and Robinson (2013, p. 22) included in their ‘environmental context’ elements or attributes such as location, culture and social influence, colleagues, professional and organisational culture, work roles, objectives, tasks, time and financial constraints and technology (e.g. telephone, television, radio, computer systems and the Internet and communication systems) as factors. They observed that these factors, needs, wants, goals and perceptions deriving from the personal and environmental contexts motivate or inhibit information behaviour.

Elements relating to the inner person

Regarding the attributes of a personal component, Wilson (1981) identified psychological factors, while Sonnenwald and Iivonen (1999) referred to preferences, abilities and affects that influence information behaviour. Kuhlthau (1991) described emotions and feelings that can be related to the affective structures of the human mind (Nahl, 2001). Nahl (2001) described both the positive and negative emotions a person may experience during the consecutive stages of the information searching process. Robson and Robinson (2013, p. 22) referred to the personal component as the ‘internal environment’ and included the information actor’s demographics, expertise (including knowledge, education, training, experience) and psychological factors (including self-perception and self-efficacy, perceptions of others, perception of a knowledge gap, cognitive dissonance or cognitive avoidance, ability to cope with stress, thoughts and feelings while searching for information). Davies and Williams (2013) also recognised the role of a person’s inner experiences when they referred to a combination of cognitive, affective and behavioural processes that result in information being perceived, processed and collected by the individual.

Elements of technological mechanisms

Earlier studies viewed technologies as subordinate to context and therefore did not clearly identify elements belonging to a technological component. Sonnenwald and Iivonen (1999, p. 435) identified social networks, information and information resources, information and communication technologies involved in providing access to information. Robson and Robinson (2013, p. 22) related technological devices to context and included access to telephone, television, radio, computer systems and the Internet and communication systems as factors influencing transfer activities.

Burford and Park (2014, p. 630) argue that tablet devices and their applications are increasingly used to access digital information. These devices ‘enhance users’ ability to construct and individualise online information and construct a mobile interface to suit their own information requirements’. They have not only brought about changes in the lives of young adults, but also affected the various activities of seeking, searching, creating, reassembling and arranging digital information in an online environment. In addition, the authors pointed out the link between the creation of information, social media and the growing importance of ready access to digital environments in the 21st century.

Interrelationships among relevant components

For a model to move closer to a theory, Cole (2013) argues the importance of describing the interrelationships among the relevant components. Establishing relationships proved to be difficult, as all dimensions are interdependent (Fidel et al. 2004; Sonnenwald and Iivonen, 1999).

Wilson (1981) viewed the relationship between information behaviour, information seeking and information retrieval as what sets the information behaviour process in motion. The interaction between information needs, seeking and use was accepted as a fixed relationship. More recently researchers described relationships among different sets of components, which allow for a broader perspective of the relationships among the relevant components. For example, Ingwersen’s (1984) model shows the relations among information and cognitive processes. Nahl’s (2001) work emphasises the interplay among the mental structures that serves as the trigger to take action in terms of decision making, which eventually gives rise to the relevant information activities.

Evidence of other relationships between the different components comes from the arguments that a demand for information originates in the context in which a person functions (Wilson, 1981; Byström, 2002). In addition, Wilson (1997) argued that different kinds of activating mechanisms could derive from different components. Wilson (1997 in Courtright, 2007, p. 287) referred to stress and coping factors, and ‘other intervening variables arising from personal, environmental, situational and sources related factors’. He pointed out that a person’s perception of risks and rewards, as well as past experience and perceptions of self-efficacy, may serve as activating mechanisms.

In their profile of the provider, Davies and Williams (2013, p. 547) referred to ‘the information value chain from strategic management, emotions and motivations from psychology and totality of information behaviour …’ Williamson (2005 in Burford and Park, 2014, p. 625) called for a focus on ‘the relationships between information types/sources/systems and the information seeker/user’. Burford and Park (2014), who paid attention to the link between the creation of information, social media and the growing importance of ready access to digital environments, suggested interaction between the activity component, the technological component and the contextual component.

Findings

A careful comparison and matching of evidence of the selected studies revealed more insights than anticipated. The findings showed that information behaviour is primarily a mental process with intricate relationships among its core components and their attributes. Wilson (2005, 49) argued that information behaviour becomes observable only in physical information activities such as seeking, searching, use and transfer. Besides information needs and the various information activities, the respective researchers viewed the context in which people function, the personal dimension, as well as information and technologies to handle information as of cardinal importance to the information behaviour process. It also became evident that attributes of the respective components fulfil particular functions in the information behaviour process, or set criteria with which the person-in-context must comply. For example, contextual attributes seem to determine the nature and type of information required for a particular task or decision, while attributes of the mental structures (personal component) can enhance understanding, control the use of information, or motivate action. In this regard Wilson (1997) referred to some of these attributes as activating mechanisms and intervening variables, which may either support or inhibit information seeking. Insights gained from the interrelationships discussed by the respective researchers showed that such relationships are instrumental in setting the information behaviour process in motion, as suggested by Wilson (1981). It has also been observed that the interrelationships among the respective components are involved in the underlying flow of mental actions – from the context where an information problem arises to the information activities component where physical activities are carried out to achieve the desired outcome.

While it is admitted that there may be more components and attributes, those identified by the respective models proved to be fundamental for information behaviour to take place. From the findings it became clear that (since researchers have drawn on each other’s models) combining their contributions provides useful insights for more experienced researchers to gain a holistic understanding of what information behaviour entails.

However, it became evident that for purposes of novice researchers the core components and their subdivisions need to be untangled and repackaged to get a clearer picture of where the attributes belong that act as “activating mechanisms” or “intervening variables”. Furthermore, it became clear that fixed terminology is required to represent variant terminology and also to distinguish between components and their subordinate attributes.

Proposed model

Considering the findings, it was regarded as a viable option to bring together in one single framework researchers’ contributions of the core components and elements subordinate to the respective components, and to suggest by means of a flowchart how the interrelationships among the respective components could come about. A framework depicted in Figure 1 was drawn up in which the core components were positioned in a specific order proposing the underlying flow (one-directional single-headed arrows in figure 1) that the information behaviour process follows – from initiation to the point where relevant activities are carried out. Interaction among the components is indicated by bidirectional double-headed arrows in figure 1. The proposed model is followed by a more detailed discussion of the role the respective components and their attributes play, as well as the multiple relationships among them.

Information component

Although information is not explicitly acknowledged as a component in existing models, its role is evident in information behaviour. If Floridi’s (2015) argument is accepted, information serves as one of our most important resources in everyday life. Without the interaction between the individual and information (Bates, 2009, p. 2381) the information behaviour process cannot take place. It serves as a ‘human tool’ (Dervin, 1983) and it helps to create new insights, or change existing understanding. Information is applied as an input resource to complete tasks or solve problems. As input resource it comprises factual information outside the human mind harnessed in different formats (including digital information), users’ personal knowledge and experience, as well as the collective memory captured in experience and everyday life practices of groups of users such as consulting engineers (Du Preez, 2015). People, objects, images and sound can also serve as sources of information, depending on the circumstances. To what extent information will affect the user’s behaviour will depend on the interplay (indicated in figure 1) among attributes in the mental structures of the personal component.

Examples of effects include people’s preference for sharing information by means of social networking, or changes to current trends in using information and/or tools and techniques to carry out the different types of information activities, solve information-related problems, alleviate uncertainty, find inspiration or create new information.

Contextual component

Context is understood as the area in which people operate and interact with information, including a virtual context where physical boundaries become blurred (Burford and Park, 2014). It is accepted that people can operate in different types of context, such as contexts of health, engineering, development, et cetera. Elements as subdivisions of the contextual component comprise a variety of attributes and events that guide its functioning and also determine the type of information required. For example, elements related to a work-based context include rules, regulations, work roles, tasks, et cetera (Sonnenwald and Iivonen, 1999; Fidel et al., 2004).

Each element seems to have a set of criteria in terms of purpose, nature, scope, quality, quantity and urgency required to accomplish a particular task. For example, rules and regulations of an organisation (context) will determine the quality of information that is required for a task, when, and how much detail is required for a particular purpose or situation. It is argued that the elements of the context are set in motion by a decision taken to solve a problem or complete a task.

Interaction between the context and the personal component commences when the user is confronted with the nature of the information required, as well as the criteria set by the specific attribute or event. Hence Wilson’s (1981) argument that elements related to the performance of particular tasks and the processes of planning and decision making are among the principal generators of cognitive needs.

Personal component

Guided by Nahl’s (2001) contribution, it is accepted that the personal component comprises three mental structures, namely the (i) cognitive, (ii) affective and (iii) sensorimotor structures. There seems to be consistent interaction among the mental structures of an individual. Each mental structure has its distinctive attributes. For example, when a person in context receives messages from a situation or task that requires decision making, the attributes within the respective structures interact to match perceptions with incoming messages.

The cognitive structure enables a person to make sense of received messages. Understanding comes about when incoming messages are matched with existing knowledge, experience and skills. The cognitive structure not only enables a person to make sense of incoming messages, but also to judge received messages based on prior knowledge and experience. A person’s ability to reason and think, as well as the ability to recognise when information is lacking, or the ability to select from the existing store of knowledge, are attributes of the cognitive structure.

The affective structure comprises attributes such as emotions and feelings (for example, excitement, anxiety, uncertainty, frustration or satisfaction), which can affect a person’s attitude to information needed to accomplish a task. The affective structure also has to do with a person’s belief systems – a person’s belief in his/her capability to perform a particular task (Wilson, 1997). Attributes such as norms, values and preferences are instrumental when people perceive information as either useful or less useful and therefore influence their decisions to accept, reject, or avoid information. In this way the attributes act as control mechanisms.

An outstanding attribute of the sensorimotor structure is the ability to set actions in motion, such as recognising information needs, making decisions and planning. The interplay between the cognitive and affective structures enables the sensorimotor structure to set actions in motion (Nahl, 2001). It is argued that the sensorimotor structure kicks in at a stage when a person recognises that there is a gap in his/her state of knowledge regarding a situation or topic (Belkin, Oddy and Brooks, 1982). This 'gap stage’ (Dervin, 2005, p. 29) seems to be the crucial point at which a person develops a need for information to allow him or her to move forward.

Information needs component

Considering that the performance of tasks and the processes of planning and decision making generate cognitive needs (Wilsons, 1981) and the resultant interaction that takes place in the personal component (Nahl, 2001), it seems evident that the information needs concept is closely related to the personal component, as indicated by figure 1. The interplay among the mental structures shows that information needs arise after interaction between the mental structures of the personal component has taken place.

Attributes that can be assigned to the information needs component include cognitive needs (triggered by performance of tasks, decision making and planning) and affective needs (triggered by a need for achievement) as distinguished by Wilson (1981). Affective needs may also include needs to create understanding, alleviate uncertainty and broaden a person’s knowledge base (Case, 2012) as well as a need for inspiration (Makri and Warwick, 2010), which can be added as attributes of the information needs component.

Technological component

The technological component comprises various man-made mechanisms (including older technologies and manual mechanisms) devised to enhance different information activities. These mechanisms represent the elements of this component and include among others information sources and resources, social network tools, touch-based mobile technologies and application software. Some of their attributes include ease of use, speed and convenience, saving costs, time and effort, which can control or enhance the flow of information. Depending on the extent to which users can comply with their set requirements, these mechanisms may change users’ preferences and eventually their information use habits. It seems evident that technological mechanisms may have a profound influence on a person’s competencies and preferences residing respectively in the cognitive and affective structures of the personal component.

Depending on circumstances that give rise to a need for information, a person may decide whether to seek, use or send information and therefore select the most appropriate tool to perform the particular activity. If it is assumed that decision-making actions are motivated by the sensorimotor structure, the decisions to select the relevant activity and apply the most appropriate tool, programme or procedure to carry out the activity should be taken more or less simultaneously. Therefore, this component is positioned above the activities component on the flow chart in figure 1.

The technological component maintains a fairly complex relationship with the other core components. For example, there is a close relationship between the personal component, technological component and the respective activities in the activities component, as indicated in figure 1. However, the selection and application of tools and procedures are also closely related to the work environment as well as the nature and type of information required from the information component. What seems to remain fixed is that no interaction between the technological component and the other components will take place without the action taken by the sensorimotor structure of the personal component. Evidently the extent to which technological mechanisms are responsible for challenging user’s competencies, changing preferences, shaping decision making and enhancing information activities seems to justify its inclusion as a core component of information behaviour.

Activities component

Following the information behaviour process up to this point, it seems that all activities involved are solely part of a mental process that cannot be observed outside the human mind. The relationship between context and the personal component seems to build up progressively to a point where information behaviour becomes observable as reflected in the activities of seeking, searching, use and transfer or communication (Wilson, 2005, p. 49). The activities component is where the mental acts change to observable activities. Hence information activities are clustered in the activities component in figure 1.

While the sensorimotor structure of the personal component triggers physical action, a close relationship with the activities component in figure 1 seems inevitable. Accepting that there is not necessarily a fixed linear order in which the information activities are triggered (Davies and Williams, 2013, p. 554), the arrows (figure 1) between the relevant activities are indicated by dashed lines. Which information activity needs to be performed will depend on decisions taken in the personal component. The type of activity selected in real life depends on the situation for which the information is required. It also depends on how much is known or understood about a topic, as well as prior experience. For example, when existing information in a person’s knowledge base is insufficient, a decision to seek information will be taken. If the required information is available to perform a certain task or achieve a certain outcome, a decision might be taken to use existing information without performing the seeking activity. Alternatively, if a request from the context to provide, or to share information with others is made (Davies and Williams, 2013), a decision might be taken to perform the transfer activity. The seeking and use activities will then be skipped, as indicated by the dashed lines in figure 1.

Conclusion

The proposed model attempted to offer a guideline for novice researchers, enabling them to come to grips with the many approaches they encounter in the literature as to what information behaviour entails. The core components of information behaviour, which are in real life intertwined, were untangled to clarify their respective contributions. Each component was subdivided to highlight the functions of its respective elements.

The identified relationships among the respective components shed light on their roles as building blocks in the information behaviour process. A flow chart was used to show that the model not only comprises a mere description of building blocks, but reflects on the dynamics of a mental process motivated by multiple circumstances, inner personal responses and technological mechanisms.

It is envisioned that the proposed model could serve as a useful tool in guiding research and teaching information behaviour. This generic model offers fresh insights and it is hoped that it will also support information behaviour research in disciplines further afield.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Prof. Ina Fourie for her encouragement and inspiration, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions.

About the author

Hester Meyer has a DPhil (Information Science) and is currently a Research Associate with the Department of Information Science, University of South Africa. Research interests are in the field of information behaviour and the role of the information intermediary in the transfer process. Full mailing address and contact e-mail address: Dr HWJ Meyer, PO Box 74325, Lynnwood Ridge 0040, PRETORIA, South Africa. meyerhwj@gmail.com