Privacy and trust attitudes in the intent to volunteer for data-tracking research

Catherine L. Smith.

Introduction

In daily life, people use search engines, social networking sites, and other electronic resources as a matter of course. Companies that provide these services record their users’ activities for purposes of modelling and predicting needs and preferences. In exchange for valuable services, users grant companies permission to access, record (log), and analyse highly personal and detailed information such as the content of email, search engine query terms, and URLs of Websites visited (Kellar, Hawkey, Inkpen and Watters, 2008). Collected data may be anonymised, or users may grant permission for the retention of identifiable data for the construction of individualised profiles. With these data, commercial enterprises such as Google, Facebook, and Microsoft have acquired detailed and powerful views on many aspects of human information behaviour.

For academic researchers, understanding how current systems are used in the wild is fundamental. One approach to this is ethnographic methods (Rieh, 2004), which are time-consuming to analyse and often focus on small samples that may not generalise. Research participants may be invited to a lab for observation, but the completion of assigned tasks is unlikely to reflect typical user needs and behaviour, even when participants are asked to perform their own tasks (Hearst and Degler, 2013). Beyond the need for records of interaction during authentic problem solving for domains such as health care (Mamlin and Tierney, 2016) and disaster recovery (Spence, Lachlan and Rainear, 2016), long-term longitudinal data are critical to understanding changes in usage over time. Obtaining such data requires access to shared collections (e.g., USEWOD2012, n.d.), collaborative work across industry and academia (Dumais, Jeffries, Russell, Tang and Teevan, 2014; Yang and Soboroff, 2016), or the deployment of data tracking processes developed by and for academic researchers (Feild, Allan and Glatt, 2011).

One solution for academics is a collaborative approach such as a living laboratory (Kelly, Dumais and Pedersen, 2009; Smith, 2011, 2013). Enterprises of this type are shared among researchers and may engage volunteers in the co-design of information systems (Pallot, Trousse, Senach and Scapin, 2010). In this paper, we focus specifically on the concept of a virtual lab, where collaboration occurs online and participants are remote. Here, ideal volunteers would grant permission for the tracking of detailed interaction data across all personal digital devices. From the perspective of privacy and trust, the development of such a facility faces two interdependent challenges. First, the privacy of volunteers must be safeguarded through techniques such as anonymisation and differential privacy (Ohm 2010; Yang and Soboroff, 2016). Second, in a chicken-and-egg problem, testing these privacy techniques requires a sufficient number of volunteers (Feild and Allan, 2013). Researchers in both the academy and industry have found it difficult to recruit volunteers willing to knowingly install tracking software on their computers (Guo, White, Zhang, Anderson and Dumais, 2011; Community Query Log Project, 2010; Russell and Oren, 2009). Challenges in recruiting research volunteers extend to other domains (Close, Smaldone, Fennoy, Reame and Grey, 2013; Koo and Skinner, 2005), but it is also likely that privacy concerns associated with tracking cause specific impediments. This paper addresses these concerns and other factors hypothesised to affect the decision to volunteer.

This paper is organised as follows. First, we briefly review selected literature on privacy and trust. Following this background information, we state four specific research questions and then describe the method of the study and results. We then discuss our findings and implications before concluding. The paper contributes findings on factors affecting a potential research volunteer’s decision to participate in research, with specific findings on the requirement to download and install tracking software on one’s own computer.

Background

There are many obvious considerations in a decision to volunteer for research where explicit disclosure of private information is required. Two basic aspects are one’s views on personal information privacy and trust that one’s privacy will not be violated. While these are straightforward concerns, the study of privacy and trust is not, particularly in light of the many issues raised when modern information technologies are involved (Stutzman, Gross and Acquisti, 2013). There are many studies on privacy and trust in various disciplines and social contexts: law, business, marketing, psychology, computer science, information science and so forth (see, Bélanger and Crossler, 2011; Wang, Min and Han, 2016). While privacy and trust have been treated separately, recent work has examined the combined role of each in human affairs. Many useful conceptualisations flow from this work. Discussions from the law (Nissenbaum, 2001, 2004) are written with the goal of developing a theoretical framework for discussion of practical implications. In this background section we introduce central concepts of privacy and trust starting with Nissenbaum’s views, and then present work on several major constructs.

Conceptualisation of information privacy

In introducing conceptualisations that underlie our study, we begin with Nissenbaum’s paradigm of contextual integrity (2004). In investigating factors in privacy perception, Martin and Nissenbaum (in press) hypothesised that one’s sense of privacy is dependent on three aspects of context: the specific actors involved (who is sending or receiving information), expectations on the flow of information between the actors (when and how the information will be used), and the type or content of information within that flow (what is shared). More generally, Nissenbaum’s view posits that context forms social and personal norms for privacy, and that privacy violations come about when contextual elements are misaligned.

For example, granting permission to a search engine (actor) for the recording of query terms (content) for the purpose of improving search outcomes (flow) is normative; in this context the searcher perceives some acceptable level of privacy. In contrast, if the query terms are later distributed to a third party for marketing purposes, the flow is altered in violation of the norm, and privacy is diminished.

In the present study, we examine the specific context of a researcher recruiting volunteers for a study that requires the explicit action of downloading, installing and activating tracking software that records search interaction. In this scenario, the actors are the potential volunteer receiving a recruiting communication, the researcher sending it and the researcher’s affiliated institution. The content is the verbatim text of search queries and the URLs of Websites visited. The flow of information mirrors that expected with search providers, except that the researcher offers no exchange of services for the right to access (Richards and Hartzog, in press). As suggested by Nissenbaum’s view, privacy is a highly complex construct.

Typical factors studied in work on privacy-related decisions include general privacy concerns (e.g., Malhotra, Kim and Agarwal, 2004), context-dependent privacy concerns (e.g., Internet privacy concerns, Dinev and Hart, 2006) and other situational factors (for a comprehensive review, see Bélanger and Crossler, 2011). Recent work (Dinev, Xu, Smith and Hart, 2013; Kehr, Kowatsch, Wentzel and Fleisch, 2015) has found evidence for the subsuming construct privacy perception, which is characterised as ‘an individual state, subsuming all privacy-related considerations at a specific point in time’ (Kehr, et al., 2015, para. 1). Kehr et al. found privacy perception to be antecedent to privacy-related decisions on information disclosure. Two key findings flow from this work. There is an interdependency of risk and benefit perceptions, whereby the perception of risk to privacy is mitigated by the perception of greater benefit from disclosure (Dinev et al., 2013; Kehr et al., 2015). The same studies found that perceptions of risk and benefit vary with other factors such as general concerns about privacy, the affective valence of communications and trust in technology infrastructure. Dinev et al. found that the perception of control over the information involved (i.e., anonymity and secrecy) affected perceptions of privacy.

More generally, trust has been found to be a key factor in decisions on the disclosure of private information. Next, we introduce the general concept of trust, and then briefly review associated factors before concluding with a discussion of models that account for both privacy concerns and trust relationships.

Conceptualisations of trust

In work on privacy, trust has been modelled as an outcome on perceptions of risk (e.g., Dinev and Hart, 2006) and as antecedent to perceptions of risks and benefits (e.g., Kehr et al., 2015). In a recent meta-analysis of research on trust in decisions on engagement in social media, Wang, Min and Han (2016) examined trust as a causal factor in perceptions of risk to information privacy and security. Given the complexity of interdependencies between trust and privacy, in considering the role of trust in decision making we turn again to Nissenbaum (2001) for views taken from the broader and more practical vantage point of the law. Next, we summarise and paraphrase her characterisations of trust.

Generally, trust is a specific relationship between a trustee (the entity being trusted) and a trustor (the person who trusts). Trust forms over time and with experience; however, in order for trust to accrue, there must be sufficient initial trust. Trust is affected by the history and reputation of the trustee. Where the trustor has some basis for personal knowledge of a trustee, perceptions of the trustee’s personal characteristics affect trust. Within the social context in which trust is sought, a trustee assumes a role. The trustor’s knowledge of the trustee’s qualifications for that role are important to initial trust formation. More generally, the construct of social context includes norms for trustworthiness in the relationship, any penalty the trustee faces for failing to prove trustworthy, the likelihood of disclosure should there be a failure and any insurance against the trustor’s loss if the trustee proves untrustworthy. Finally, trust is most likely to develop when two parties share a mutual condition or risk and there is some expectation of reciprocity. In the context of our study, all of these factors may be involved in a potential volunteer’s decision on enabling data tracking.

As with work on privacy, trust has a large literature covering many models and conceptualisations. McKnight, Choudhury and Kacmar (2002) summarise these constructs in a review of work on trust in the context of e-commerce. We apply these concepts to the perceptions involved in volunteering as a research participant, an act which requires some level of trust or willingness to be vulnerable (Mayer, Davis and Schoorman, 1995). Note that vulnerability implies acceptance of risk.

The study presented in this paper involves three trustees: the individual researcher seeking volunteers, the researcher’s affiliated institution and the information technologies used to communicate about and conduct the study.

The work of McKnight and others (McKnight, Carter, Thatcher and Clay, 2011; McKnight and Chervany, 2001; McKnight, Choudhury and Kacmar, 2002) suggest the following conditions for trust in e-commerce and technology-enabled contexts. With respect to the trustworthiness of individuals, the researcher must be perceived as benevolent and possessing sufficient competence and integrity to perform as promised (McKnight et al., 2001). The university, as an institution, must be perceived as providing structural assurance (mitigation of risk by social constructs such as rules and regulations) and situational normality (proper, customary, and understandable roles) (McKnight et al., 2002). Finally, the specific technologies involved must be perceived as having the functionality required to perform as promised, sufficient reliability to assure predictability and a quality of helpfulness (McKnight et al., 2011). In recruiting volunteers through online means, only electronic or digital communication is available for conveying these qualities of trustworthiness.

Privacy and trust in decision making

We conclude our review on privacy and trust by considering elements involved in the recruitment of research volunteers, where participation requires the installation of tracking software. We focus on two papers that have modelled privacy and trust factors in the context of engagement with specific software applications. These papers use the constructs mentioned above while introducing additional factors.

In a synthesis of prior findings on interrelated constructs on trust and risk, Wang, Min and Han (2016) conducted a meta-analysis of forty-three studies drawn from the literature on social media. In reviewing the work, the authors found the perception of risk often measured using privacy constructs. Their analytical framework examined associations between trust and risk, and the associations of each on data sharing behaviour, among other outcomes. Trust was found to have a larger effect than risk. While the perception of risk was associated with diminished sharing, the larger effect of trust was associated with diminished risk perception and more sharing. In examining moderators on sharing behaviour, trust in the technology platform (the site, community, or service provider) was found to have greater effect on sharing than did trust in members of the community or network.

The specific situation of trust required for agreement to tracking involves a sufficient belief that privacy will be protected in a complex information relationship between the three hypothesised trustees and the volunteer. Richards and Hartzog (in press) conceptualised information relationships involving entrustment of private information to a service provider; however, in a research scenario, there is no direct service relationship. For the volunteer, benefits are likely to be short-term rewards such as cash or other credits, and possibly anticipation of long-term value from new knowledge or improved outcomes. Also, an altruistic volunteer may place value on benefits that accrue to the public good (Edwards et al., 2009; Stunkel and Grady, 2011). In modelling the decision to disclose private information through a smartphone app, Kehr et al. (2015) found that the perception of greater benefit mitigated the perception of risk. The perceived sensitivity of the information to be disclosed had a compounding effect on perceptions, so that where more sensitive information was involved, the perception of benefit was diminished and the perception of risk was enhanced. The model also included measures of trust in underlying smartphone technology (termed institutional trust), finding greater trust associated with increased perception of benefit. These findings suggest that for research studies involving sensitive information and few direct benefits, participation is likely to hinge on a sufficient level of trust.

Another aspect of trust and privacy concerns for information technologies is communication of privacy protection from the trustee to the trustor. For academic researchers, this involves disclosure and informed consent meeting the legal and ethical standards of institutional review boards (Eynon, Fry and Schroeder, 2008; Kraut, Olson, Banaji, Bruckman, Cohen and Couper, 2004). Communication on risks associated with tracking software may be considered a unique form of fear appeal (Maddux and Rogers, 1983), where the goal is to invoke concerns about risk sufficient to result in reasoned consideration of a decision to take protective action. In the case of recruiting research volunteers, the goal of the fear appeal is to delineate the risks and benefits of participation in a manner that conveys the nature of the threat to privacy while informing on promised protections. Ethics require that the message be devoid of a persuasive valence of positive affect or social influence (Kehr et al., 2015; Johnston and Warkentin, 2010), which are likely to diminish the perception of risk.

Johnston and Warkentin (2010) studied the effect of a fear appeal intended to motivate the installation of software that detects tracking threats (anti-spyware). Two forms of efficacy were included in the model: self-efficacy with respect to the ability to utilise the software, and perception of the efficacy of the software. Higher levels of efficacy were associated with a greater intention to install the software, but a greater perception of threat was associated with lower efficacy. These findings suggest that a research volunteer’s decision to download and install tracking software requires sufficient perception of the efficacy of the promised privacy protections. Downloading tracking software is an explicit action to accept a threat to privacy, where the alternative is no action. Not accepting the threat is likely to be perceived as highly efficacious. These factors are likely to put an additional burden on the role of trust in the decision to volunteer.

Johnston and Warkentin’s (2010) model also included the perception of the susceptibility to threats. No significant association was found between the perception of susceptibility and efficacy; the authors speculated that prior experience moderated perceived susceptibility, such that people with no prior experience do not feel susceptible. Elhai and Hall (2016) examined anxiety about data breaches, self-reported use of nine security precautions and prior personal experience with four types of breaches. No significant association was found between prior experience and anxiety. Only one protective behaviour had a significant association; greater anxiety was associated with a higher probability of the use of a password or fingerprint reader on one’s smartphone.

The study presented in this paper draws on the earlier work discussed above to explore conditions of trust and data privacy attitudes in the context of a potential research volunteer’s intent to volunteer in a study requiring the installation of tracking software. While our work draws on the concepts mentioned above, it was not designed to test theory or to develop predictive models. Rather, the goal was to explore the salience of privacy and trust attitudes in the practical context of a respondent’s intent to volunteer as detailed in the questions listed below.

Research questions

- Does requiring the download and installation of tracking software on one’s own computer affect the intent to volunteer in a research study, as compared with the same study without the requirement for installation on one’s own computer? We hypothesise that the rate of volunteering will be lower for a study that requires data tracking on one’s own computer.

- Comparing those who say ‘yes’ to volunteering, those who are ‘unsure’, and those who say ‘no’, what, if any, are significant differences in privacy protection behaviour and prior exposure to privacy violations?

- Comparing those who say ‘yes’ for a study requiring installation of tracking software on their own computer and those who say ‘yes’ to the same study without installation on one’s own computer, what, if any, are the significant differences in privacy protection behaviour and prior exposure to privacy violations?

- What, if any, are the associations between the attitudes on privacy and trust, and the intent to volunteer in a study requiring installation of tracking software on one’s own computer?

Method

Overview

Previous work suggests that it is expensive to recruit volunteers for an actual study using downloaded tracking software, thus we used a survey approach to gather responses on a hypothetical research study (Russell and Oren, 2009; Smith, 2011). Because rates of volunteering for research tend to be low in general (Arfken and Balon, 2011; Galea and Tracy, 2007), we sought to separate general factors from those associated with the need to install software on one’s own computer. For these reasons, the study used a quasi-experimental design. In a quasi-experimental survey, respondents are assigned to groups and receive different instruments designed for comparison between the groups. Our study used two versions of a questionnaire, which was administered using a web-based online survey service. Respondents were asked about their willingness to participate in one of two versions of the hypothetical study (h-study). Half of respondents received information about an h-study requiring the installation of tracking software on their own computers (OwnV); the other half received information about an h-study requiring an appointment where the software would be installed on a lab computer (LabV). Except for details describing the assigned h-study, the questionnaires were identical.

Participants

The data were collected from an undergraduate research pool comprising students enrolled in a large introductory undergraduate course at a university in the U.S. Midwest. Students received course credit for participation. Recruiting was done through in-class announcements and an online administration system for student research pools. Pool demographics are 78% white, 58% female, with 96% under age 24. Approximately one third of students are in their first semester of college, with only 3% having obtained a prior bachelors’ degree. 8% are international students and 95% report English as their native language.

Survey structure

Table 1 provides an overview of the survey structure. After confirmation of consent to participate, the first block asked about smartphone and computer ownership. For the one student who reported not owning a computer and having no access to a computer, the survey ended and course credit was granted. We assumed that those who did not own their own a computer could face impediments to installing software, thus seven students were assigned automatically to LabV. All other respondents were assigned randomly to one of the two groups. The second block of questions asked about privacy protection practices for smartphones, computers and Websites (see Table 2). The third block presented information about the assigned h-study and collected information about the intent to volunteer. The fourth block investigated attitudes involved in the decision. The fifth block asked about knowledge of and personal experience with privacy violations (see Table 3). All survey questions except those in block four were validated for forced completion with the option to refuse an answer. Within blocks, the item order of related questions was randomised automatically.

- Block 1 Smartphone and computer ownership

- Block 2 Privacy practices: smartphone, computer, Websites

- Block 3 h-study version assigned

Block 3a Introduction to mock study- Block 3b Mock email subject line

- Block 3c LabV or OwnV version of mock recruiting email

- Block 3d LabV or OwnV version of mock disclosure and consent statement

- For those responding ‘yes’ to 3d: LabV: Would you make an appointment? OwnV: Would you download the software?

- Block 4 Fourteen semantic dichotomies

- Block 5 Previous experience with, and knowledge of, privacy violations and threats

Table 1. Block structure of the online survey

Block 3: Questions on intent to volunteer for the h-study

Communication materials were written to comply with institutional review board requirements, with the h-study described as being about how people search for information on the Internet. The block was exactly the same except for the requirement for an appointment and software in the lab for LabV, and the requirement for downloading and installing the software one’s own computer for OwnV. The block started with the same mock e-mail subject line, ‘Participate in a research study and earn up to $40’, and asked about the likelihood of opening and reading such an e-mail. The next page displayed a mock recruiting e-mail, which contained information about the assigned h-study (see Appendix A). The email contained the sentence: ‘To learn more about the study, or to sign up, visit this website: [url]’. Questions at the bottom of the page asked, ‘Do you have enough information to make a decision about participating?’ and ‘Would you click the link to learn more?’. Respondents were instructed to assume they had clicked the link. A disclosure was then displayed for the assigned h-study (see Appendix B). The next questions asked ‘Do you have enough information to make a decision about participating?’ and ‘Would you agree to participate?’. Only those who answered ‘yes’ to participating were asked a follow-up question about the likelihood of taking action to participate—for LabV: ‘Would you click to schedule an appointment in the lab?’, and for OwnV: ‘Would you click to download the CrowdLogger [data tracking] software?’.

| Privacy protection behaviour | % responses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | ||

| Computer | Manually clear browsing history | 21 | 54 | 17 | 7 |

| Manually delete cookies | 51 | 40 | 5 | 4 | |

| Manually clear search history | 31 | 46 | 17 | 6 | |

| Manually clear cache | 53 | 39 | 6 | 2 | |

| Smartphone | Manually clear browsing history | 27 | 41 | 18 | 14 |

| Manually delete cookies | 67 | 22 | 4 | 7 | |

| Manually clear search history | 35 | 39 | 16 | 10 | |

| Manually clear cache | 64 | 18 | 11 | 7 | |

| Apps | Check for privacy tool | 38 | 30 | 13 | 19 |

| Ask friends about it | 41 | 27 | 21 | 11 | |

| Read privacy policy | 57 | 35 | 6 | 2 | |

| Check ratings | 9 | 23 | 33 | 35 | |

| Refuse to share with third party | 14 | 28 | 30 | 29 | |

| Check for certification | 45 | 28 | 15 | 13 | |

| Use privacy setting | 9 | 21 | 28 | 42 | |

| Websites | Check for privacy policy | 36 | 28 | 23 | 14 |

| Ask friends about it | 26 | 34 | 26 | 16 | |

| Read privacy policy | 44 | 47 | 8 | 1 | |

| Check ratings | 31 | 33 | 23 | 16 | |

| Refuse to share with third party | 18 | 25 | 32 | 25 | |

| Check for certification | 41 | 26 | 16 | 17 | |

| Use privacy setting | 12 | 28 | 27 | 33 | |

| Set device to: | Per cent report using | |

|---|---|---|

| Computer | Automatically clear browsing history | 7 |

| Automatically delete cookies | 12 | |

| Automatically clear search history | 6 | |

| Automatically clear cache | 6 | |

| Software preventing tracking | 8 | |

| Software blocking ads. | 57 | |

| Other protection software | 33 | |

| Smartphone | Automatically clear browsing history | 9 |

| Automatically delete cookies | 6 | |

| Automatically clear search history | 16 | |

| Automatically clear cache | 4 |

| Knowledge of privacy violations in past two years | Per cent reporting number of instances | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | 1 or 2 | 3 or 4 | 5 to 10 | Over 10 | ||

| Personal victim of... | privacy invasion | 47 | 41 | 9 | 3 | — |

| stolen credit card, bank account, information | 79 | 21 | 1 | — | — | |

| Known a victim of... | privacy invasion | 18 | 42 | 23 | 13 | 4 |

| stolen credit card, bank account, information | 9 | 53 | 22 | 12 | 4 | |

| Heard or read about... | identify theft | 16 | 38 | 23 | 8 | 15 |

| potential invasion of privacy through surveillance | 16 | 39 | 25 | 11 | 10 | |

| potential invasion of privacy by hackers | 12 | 38 | 27 | 8 | 15 | |

| misuse of information collected from the Internet | 6 | 19 | 26 | 22 | 27 | |

Block 4: Questions on attitudes toward volunteering

Two types of questions collected information about attitudes. First, after a reminder of their decision about participating (‘Earlier in the survey, you were asked... You answered saying you would/would not/were undecided...’), an open-text question asked respondents to explain the reason for their answer. The next page displayed fourteen semantic dichotomies in a bi-polar matrix of radio buttons labelled 1 through 10, with opposing ends of the dichotomies displayed at each end of the scale (see Table 4).

The dichotomies were developed using responses from an earlier version of the instrument, which contained scales adapted from the literature reviewed above. The instrument also contained a similar open-response question on the intent to volunteer. The verbatim responses were used in bottom-up content analysis (Krippendorff, 2012), resulting in the bipolar items. Further detail on the development of the dichotomies is presented elsewhere (Smith, 2016). In preparing the instrument for this study, three of the dichotomies were reversed.

| In thinking about my desire to participate, [I feel]... | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Dichotomy name | Left (low) | Right (high) |

| Technology | Download (R). Downloading software makes me feel... | At ease | Worried |

| Software. I understand how the software works... | Completely | Not at all | |

| Trustees | Institutional review boards. University review board approval [makes me] feel... | Confident | Sceptical |

| Email. Email from [university name] is... | Trustworthy | Not trustworthy | |

| Researcher. The researcher is.... | Trustworthy | Not trustworthy | |

| Privacy | Protection. The privacy protections are... | Sufficient | Insufficient |

| Tracking (R) Tracking my Internet activities is... | Acceptable to me | Unacceptable to me | |

| Information | Information. The information I've been given is... | Enough to decide | Not enough |

| Opinion (R) Hearing...opinion[s] before volunteering is... | Unessential to me | Essential to me | |

| General | Time. The study is (1) ... | Good use of time | Poor use of time |

| Interest The study is (2).... | Interesting to me | Not interesting | |

| Ease (R) Completing the study would be... | Easy | Difficult | |

| Money. The money is... | Satisfactory | Unsatisfactory | |

| Volunteering. Helping by volunteering is... | Important to me | Unimportant to me | |

Data preparation

The survey was completed by 404 students. Five steps of data cleaning were used before analysis (see Appendix C). This resulted in the exclusion of 73 per cent of the records, which is consistent with a 75 per cent data-cleaning exclusion for a similar study (De Santo and Gaspoz, 2015). We were mindful that our data cleaning process could bias the final sample; therefore, we tested the distribution of the excluded responses at each step, finding no bias. Respondents were identified as either closed, unsure, or open to volunteering; we refer to this variable as the intent to volunteer, or Intent. With 294 responses excluded, 110 valid records remained: 51 from LabV and 59 from OwnV. We report on analysis of these records only.

Analytical approach

As the measures of behaviour and prior experience are count data, these are compared using the non-parametric, linear-by-linear, chi-squared test for differences in response frequency across the three levels of Intent. Because the measures of attitude were gathered using a ten-point scale, we used an analysis of variance to examine associations between Intent and h-study. As a result of the exploratory nature of this work and the large number of tests performed, we use an alpha level of 0.05 and two tails in our tests for significance. Post hoc analysis was performed using the conservative Scheffe method.

Results

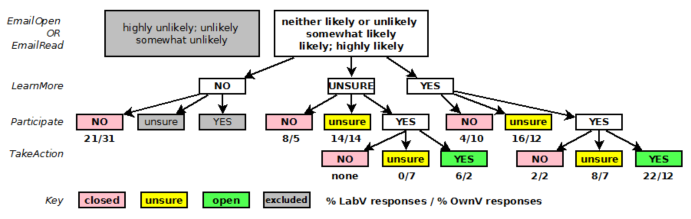

Research question 1 on intent to volunteer

Table 5 lists the rates of hypothetical volunteering for each h-study. In answering research question 1, chi-squared analysis was used to test the hypothesis that participants in the OwnV group were less likely to be open to volunteering than those in the LabV group. Although the rate was lower by half (14% vs. 28%), differences were not significant across all three levels of Intent (χ2 (2) = 3.629, p = 0.159). A comparison between open and closed rates approached significance. (χ2 (1) = 3.587, p = 0.058).

| h-study version | Per cent in response category (Intent) | Per cent total sample (count) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open | Unsure | Closed | ||

| LabV | 28 | 37 | 35 | 46 (51) |

| OwnV | 14 | 39 | 48 | 54 (59) |

| Total | 20 | 38 | 42 | 100 (110) |

Research questions 2 and 3 on protection behaviour and previous experience

In addressing research question 2, we examined associations between intent to volunteer and reported privacy protection behaviour, previous experience, and knowledge of privacy violations (see Tables 2 and 3). As a result of the small sample sises in many cells, exact tests and SPSS Monte Carlo sampling were used to verify results derived through asymptotic analysis. Using a linear-by-linear model, we tested for a significant relationship between behaviour reported as frequencies and intent to volunteer. Each binary response about behaviour was tested by chi-squared analysis. No significant differences were found for any variable for either group.

We addressed research question 3 by comparing the same measures for open respondents in each group. No significant differences were found between open respondents in LabV and open respondents in OwnV.

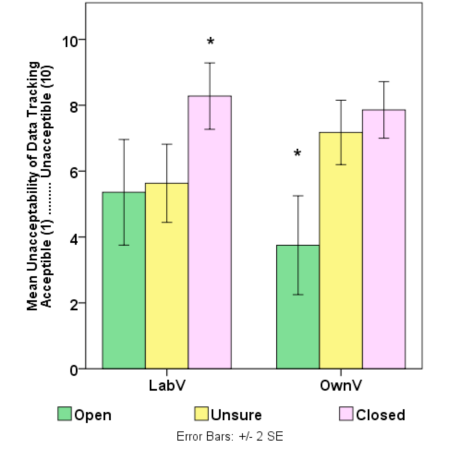

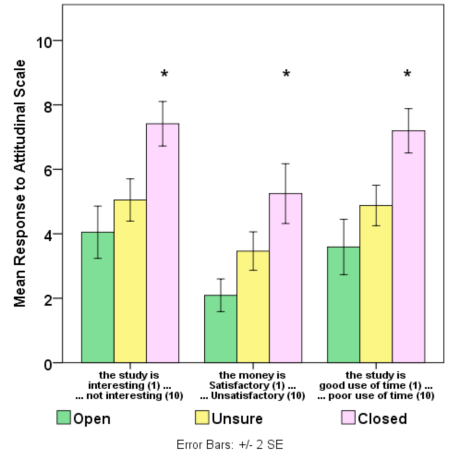

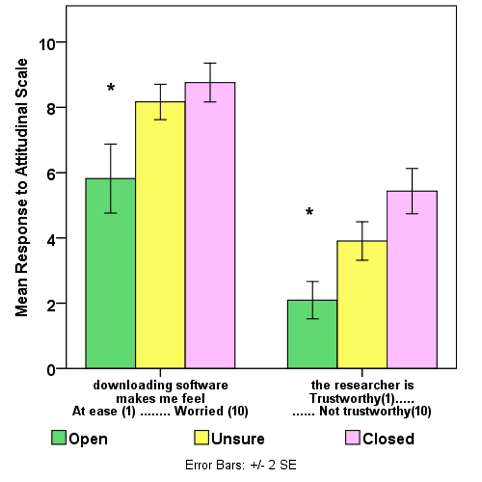

Research question 4 on attitudes associated with intent to volunteer

Fourteen ten-point bi-polar scales were used to measure attitude in the context of the intent to volunteer. These data were treated as continuous in a series of separate two-way ANOVAs that examined differences within and between h-study groups. Each ANOVA modelled the main effects and interaction of h-study and Intent for one dichotomy.

| Dichotomy name | p | Anchor at 1 | Mean for response level | Anchor at 10 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| Downloading (R) | *** | At ease | Oa (5.8) | Ub (8.2) | Cb (8.8) | Worried | |||||

| Understand software | ** | Completely | Oa (4.3) | U (5.4) | Cb (6.3) | Not at all | |||||

| Review board makes me | *** | Confident | Oa (3.0) | Ua (4.0) | Cb (5.6) | Sceptical | |||||

| Email is | * | Trustworthy | Oa (2.0) | U (2.9) | Cb (3.6) | Not trustworthy | |||||

| Researcher is | *** | Trustworthy | Oa (2.1) | Ub (3.9) | Cc (5.4) | Not trustworthy | |||||

| Protection | *** | Sufficient | Oa (2.9) | Ua (4.2) | Cb (5.9) | Insufficient | |||||

| Tracking (R)† | *** | Acceptable | Oa (4.8) | Ub (6.5) | Cc (8.0) | Unacceptable | |||||

| Information is | * | Enough | Oa (2.3) | Cb (3.0) | Ub (3.7) | Not enough | |||||

| Opinions (R) | Not.sig. | Unessential | Essential | ||||||||

| Use of my time | *** | Good | Oa (3.6) | Ua (4.9) | Cb (7.2) | Poor | |||||

| Study is (R) | ** | Easy | Oa (3.7) | U (4.6) | Cb (5.8) | Difficult | |||||

| Study is | *** | Interesting | Oa (4.0) | Ua (5.0) | Cb (7.4) | Not interesting | |||||

| Money is | *** | Satisfactory | Oa (2.1) | Ua (3.5) | Cb (5.2) | Unsatisfactory | |||||

| Volunteering | Not sig. | Important | Unimportant | ||||||||

| † The interaction of Intent and h-study was significant; see Table 7 and the text. O = Open; U = Uncertain; C = Closed * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001 | |||||||||||

| h-study group | Mean (s.d.) for response level | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |||

| LabV—tracking | Acceptable | O 5.4 (3.0) | U 5.6 (2.6) | C 8.3 (2.1) | Unacceptable | |||||

| OwnV—tracking | O 3.8 (2.1) | U 7.2 (2.3) | C 7.9 (2.3) | |||||||

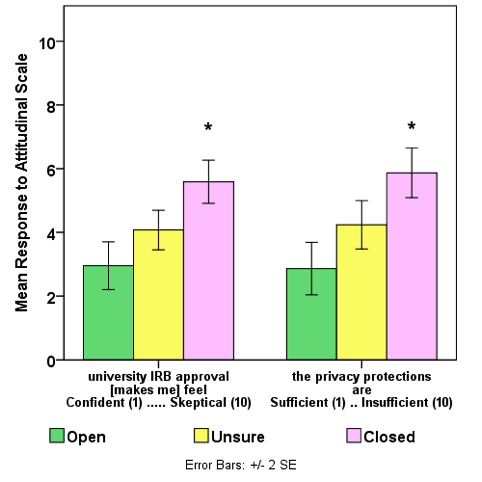

No significant main effect was found for h-study for any of the measures; however, the main effect of Intent was significant for twelve of the measures. Table 6 lists the dichotomies, the significance of main effects on Intent, and the mean for each at the three response levels across both h-study groups. Subscripts denote significant subgroups, as indicated by Scheffe’s post-hoc test. No significant interactions were found except for the acceptability of tracking on the Internet (F(2,104) = 3.38, p < 0.05), which is detailed in Table 7 and discussed next.

An analysis of simple main effects, with Bonferroni correction, was used to examine the acceptability of tracking. Among unsure respondents, there was a significant difference in the acceptability of tracking between h-study versions (F(1,104) = 4.237, p < 0.05). Relative to those in LabV, unsure respondents in the OwnV group were more likely to feel that data tracking is unacceptable. Comparison between h-studies for the other two levels of Intent (open, closed), were not significant. Within both versions of the h-study, simple main effects of Intent were significant (LabV: F(2,104) = 44.8, p < 0.001; OwnV: F(2,104) = 52.9, p < 0.001). Within LabV, the difference between open and unsure respondents was not significant, but the unacceptability of tracking was significantly greater for closed respondents (p < 0.01). Within OwnV, the difference between closed and unsure respondents was not significant, but the unacceptability of tracking was significantly lower (data tracking was more acceptable) for open respondents (p < 0.001).

Given the significant differences in attitude among those with differing levels of intent to volunteer, we investigated associations between the attitudes. Because of the small sample sise, principal components analysis was not defensible. Using separate ordinal logistic regressions, we tested for a linear relationship between each measure and level of Intent. A significant linear relationship was found for all but two measures. Table 8 lists the individual exponential beta coefficients with chi-squared and p values. This result suggests the dichotomies captured meaningful levels for the constructs underlying each bi-polar scale.

| Dichotomy name | Χ2 | df | sig | exp (beta) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology | download | 24.1 | 1 | *** | 1.56 |

| software | 8.8 | 1 | ** | 1.23 | |

| Trustee | institutional review board | 24.5 | 1 | *** | 1.55 |

| 6.3 | 1 | * | 1.29 | ||

| researcher | 36.5 | 1 | *** | 1.73 | |

| Privacy | protection | 22.4 | 1 | *** | 1.42 |

| tracking | 24.1 | 1 | *** | 1.42 | |

| Information | information | 0.3 | 1 | not sig. | — |

| opinion | 1.7 | 1 | not sig. | — | |

| General | time | 41.0 | 1 | *** | 1.70 |

| ease | 11.7 | 1 | ** | 1.29 | |

| interest | 35.6 | 1 | *** | 1.61 | |

| money | 47.6 | 1 | *** | 1.50 | |

| volunteering | 4.6 | 1 | * | 1.17 | |

| * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001 | |||||

In the light of the uniform direction and similarity in size of the beta values, we also examined the multicollinearity of the measures, finding three measures with variance inflation factors (VIFs) above 2.5 on all other bi-polar measures. These were: (1) the level of interest in the study, (2) attitude toward spending time on the study and (3) the trustworthiness of the researcher. Inexamining correlations between the measures, we found that the trustworthiness of the researcher was significantly correlated with twelve of the other thirteen measures, with four highly correlated (Spearman’s ρ > 0.600) and six moderately correlated (0.400 < Spearman’s ρ < 0.599). Table 9 details the correlations. These results suggest that the trustworthiness of the researcher may summarise or subsume other factors associated with the intent to volunteer. The high correlation (r = 0.730) between interest in the study and the use of time also suggests that these measures express the same underlying attitude. The small sample size and the high intercorrelation preclude further meaningful statistical analysis of associations between the measures.

| Dichotomy | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Researcher | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| 2 Software | 0.680** | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| 3 Inst. rev. board | 0.596** | 0.294** | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 4 E-mail | 0.553** | 0.329** | 0.434** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 5 Protection | 0.632** | 0.451** | 0.410** | 0.520** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 6 Tracking | 0.447** | 0.289** | 0.342** | 0.225* | 0.317** | 1.000 | |||||||

| 7 Ease | 0.361** | 0.429** | 0.277** | 0.298** | 0.396** | 0.299** | 1.000 | ||||||

| 8 Download | 0.482** | 0.293** | 0.376** | 0.234* | 0.413** | 0.474** | 0.236** | 1.000 | |||||

| 9 Time | 0.665** | 0.479** | 0.458** | 0.376** | 0.562** | 0.443** | 0.319** | 0.573** | 1.000 | ||||

| 10 Money | 0.618** | 0.522** | 0.504** | 0.381** | 0.587** | 0.289** | 0.407** | 0.314** | 0.515** | 1.000 | |||

| 11 Interest | 0.583** | 0.469** | 0.371** | 0.276** | 0.457** | 0.342** | 0.343** | 0.526** | 0.730** | 0.437** | 1.000 | ||

| 12 Volunteering | 0.399** | 0.314** | 0.370** | 0.359** | 0.333** | 0.209* | 0.277** | 0.163 | 0.438** | 0.319** | 0.339** | 1.000 | |

| 13 Opinion | 0.084 | -0.049 | 0.048 | -0.067 | 0.051 | 0.200* | -0.022 | 0.223* | 0.128 | 0.005 | -0.022 | 0.050 | 1.000 |

| 14 Information | 0.414** | 0.418** | 0.196* | 0.250** | 0.199* | 0.155 | 0.255** | 0.146 | 0.158 | 0.249* | 0.157 | 0.226* | 0.056 |

| Bold values = strong correlation (p > 0.600); italic values = moderate correlation (p < 0.600 and > 0.400). | |||||||||||||

Discussion

Using two versions of a hypothetical research study, we have examined privacy protection behaviour, prior experience with and knowledge of privacy violations, and attitudes associated with the intent to volunteer. Except for the acceptability of data tracking, no statistically significant results were found for any tests comparing the responses from the two h-study groups. We find no evidence that the protection practices or prior experience are factors in the intent to volunteer. This finding is consistent with that of Elhai and Hall (2016) who found no association on similar measures.

The interaction found for the acceptability of tracking suggests that the requirement to download and install tracking software on one’s own computer affected the decision to participate. This finding is consistent with the theory of contextual integrity (Nissenbaum, 2004), which predicts that sensitivity to the implications of data tracking will have different effects in different contexts. Here we find not just different levels for the decision outcomes, but the data also suggest different sensitivities in the effect of the risk perception (see Figure 1). For the OwnV group, openness to volunteering may require a threshold minimum level for the acceptability for data tracking (the minimum being a function of the direction of the dichotomy). For the LabV group, closedness may occur at a minimum threshold level of unacceptability. In viewing acceptability as the perception of risk, this is consistent with prior findings that the perception of greater risk is associated with less willingness to disclose private information and lower trust (Dinev and Hart, 2006; Dinev et al., 2013).

While the rate of volunteering for the OwnV study was half that of the LabV study, the large difference was not statistically significant. We speculate that for OwnV, the open response rate is overstated relative to actual recruiting situations. For the OwnV group, only 12% of respondents indicated a positive intent to volunteer (yes) at every step in the decision process (see Figure C.1 in Appendix C). This rate is similar to the only previously reported rate known to us for studies involving the installation of tracking software. Microsoft researchers Guo et al. (2011) reported 10% participation among Microsoft employees asked to install tracking software on their computers.

The linear associations between Intent and attitudes for twelve of the bi-polar measures suggest that those factors were meaningful in the contexts presented in the h-study. Among the five general measures on attitude toward participation, three have characteristics suggesting thresholds that separate closed respondents from others (see Figure 2). Closed respondents did not find the money satisfactory, they were not interested in the study and they saw participation as a poor use of their time. With respect to self-efficacy with technology, trust and privacy protection, two measures suggest thresholds for openness and two thresholds for closedness. Open respondents expressed less worry about downloading the software and greater trust in the researcher (see Figure 3). Closed respondents derived less confidence from research board approval and were less likely to believe that privacy protection was sufficient (see Figure 4).

Our findings support common sense with respect to the intent to volunteer. Those who are open have the greatest self-efficacy with the technology, as measured by perceptions on the ease of downloading and understanding of the software. Open respondents also had the greatest sense of the efficaciousness of the software technology, as measured by perception of the sufficiency of the privacy protections. These findings are consistent with those of Johnston and Warkentin (2010), who found that greater technology efficacy was associated with the decision to install protective software; however, the software in our study was the opposite of protective. This suggests that the effect of efficaciousness is independent of the role of the software in mitigating the perception of risk; however, Johnston and Warkentin (2010) also found that the efficacy was diminished by the perception of higher threat severity. This suggests that for the open respondents, other factors mitigated the perception of risk. Trust is a mitigating factor for the perception of risk (Dinev and Hart, 2006; Johnston and Warkentin, 2010; Kehr et al., 2015), hence, we associate open respondents’ greater trust in the researcher with a lower perception of risk, and hypothesise that this enhanced the perception of acceptability for data tracking.

With respect to ambivalence, we observe that unsure respondents were closer to open respondents on many measures, including three of the four on general attitudes toward volunteering. This suggests that they were open to volunteering in general, but specific factors affected their intent. Different from those who were open, the unsure were more worried about downloading software although they expressed a similar level of confidence from review board approval and a similar sense that the privacy protections were sufficient. Unsurprisingly, they had the strongest feeling that the information provided was insufficient.

These findings, along with the finding on the acceptability of tracking, suggest complex interdependencies between factors of trust and privacy concern. Understanding the direction of the associations between these factors, and the relative weight of their influence on intent, requires further study using more sensitive survey instruments and larger samples.

Implications, limitations, and future research

Our findings have implications for researchers who wish to use remote methods requiring the installation of logging software on participants’ own computers. Participation rates are likely to be low, even when the researcher has an affiliation with the potential participant. Prior research and our results suggest that those likely to participate perceive little risk from participation and are trusting of the recruiting context.

Attempts to enhance participation may be most effective when focused on increasing comfort with downloading and installing the software through additional information and instruction.

Also, because a sizeable share of those receiving initial communications may be unsure and lacking trust in the researcher, follow-up with personal messages sent directly from the researcher may enhance participation.

We have investigated our research question on attitude using scales that reduced complex constructs to fourteen dichotomies. Our instrument presented the measures in a single matrix after the decision to participate was made and respondents had considered their reasoning in a written open response. This approach was likely to have elicited responses with rational coherence among the fourteen measures, which would not necessarily be found using separate, multi-factor scales on the same constructs. Also, we have gathered no data on underlying context-free levels for these measures, so we do not know how the context relates to general perceptions. The above issues may be addressed in future research with a more refined instrument.

Finally, our sample is not representative of a diverse population. To the extent that other populations are likely to be more sensitive to privacy threats, participation is likely to be lower than that reported here. These factors may be addressed in future research.

Conclusion

This study contributes to our understanding of factors associated with the decision to participate in a research study. Using a quasi-experimental survey, we have investigated the roles of privacy and trust attitudes when participants are asked to install tracking software on their own computers. In comparing this scenario to a low-risk scenario (installation on a lab computer) we find that the differing levels of risk affect the decision differently.

- For those who considered the risk of installation on their own computers, agreeing to do so was associated with a strong attitude of acceptance toward data tracking.

- For those who considered the low risk of installation in the lab, not agreeing to participate so was associated with the strong attitude that data tracking is unacceptable.

More generally, across both scenarios we found differences in attitude among those who were open or closed to participation. Our findings are consistent with prior research on the interdependent roles of privacy and trust in the use of information technologies. We have made several recommendations for researchers needing to recruit volunteers for studies requiring software installation. A deeper understanding of associations between attitudinal factors requires further research with more sensitive scales and larger, more diverse samples.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the anonymous reviewers and editors for their constructive suggestions and comments, which were invaluable in improving the paper. Thanks also to Heather Flynn for her diligent work on the surveys.

About the author

Catherine L. Smith (PhD) is an Assistant Professor at the School of Library and Information Science at Kent State University, Kent, OH 44242-0001, USA. She may be contacted at csmit141@kent.edu.