Archivists about students as archives users

Polona Vilar and Alenka Šauperl

Introduction. The development of archival digital collections should follow user needs, as library and information science practice shows that otherwise collections may lack usability. To contribute to knowledge about archival users, we analysed existing literature and developed the draft profile of the student as archives user, based on Kuhlthau’s ISP and Johnson’s Model of contextual interaction.

Method. We tested it using qualitative methods: interviews and open-ended surveys of archivists from SI and BH. Research had two phases: interviews were used to form a more detailed user profile; surveys were used to verify this profile.

Analysis. Data from both methods was content-analysed.

Results. The interview data helped enhance the draft model. Survey data served to confirm and update the model: the student, called Amar, has an assignment requiring archival research. Although he prefers digital sources he works with finding aids and primary sources. He has difficulties understanding hierarchy of archival records, context of primary sources and archival jargon. He is able to reach the goal only by extensive help of the archivist and his professor.

Conclusion. We show the convergence of both approaches: literature review and research of archivists, indicating that students have similar needs and habits in BH, SI and the Anglo-American countries.

Introduction

Archives in Slovenia and Bosnia and Herzegovina have so far focused little attention on their users and their information needs, as was already mentioned by Vilar and Šauperl (2015). We started to approach this gap from two directions, theoretical and empirical. The first was the body of literature on user needs in information science (e.g., Case, 2012, Catalano, 2013 and Vilar, 2005) and archival science (e.g., Duff and Johnson, 2002; Yakel and Torres, 2003; Johnson, 2008; Daniels and Yakel, 2010, Vilar and Šauperl, 2015 etc.), which is mainly of anglo-american origin. We found, as we show in the literature review, that the study of archives users has not yet been well developed in archival theory and research. Unlike in library and information science, user studies are not common in the archival context, so not enough is known about users of either physical or digital archives. We also wonder whether findings from foreign countries would be useful for our archives. Knowing users from our archives would likely answer this question.

The second starting point was a bilateral research grant awarded to the Faculty of Arts at the University of Ljubljana (Slovenia) and Faculty of Arts at the University of Tuzla (Bosnia and Herzegovina). It aims at the exchange of expertise, theory and practice on archival description, use and users. Therefore research was conducted in the two countries, Slovenia (SI) and Bosnia and Herzegovina (BH). Because the two countries share a long common history (both were parts of the Austro-Hungarian empire, Yugoslavia before and after 1945, and have been independent since early 1990s) we may expect many similarities. For a better comparability only public archives (regional and state) were included.

Based on our literature review, we developed a profile of a student as an archives user. In our research archivists in both countries, who were not aware of this body of literature, were asked to describe the users of archives as they personally experience or imagine them, whether they work with the public regularly or only occasionally. Two methods were used, interviews and surveys. Content analysis of their responses was used to verify the theoretically developed profile.

Literature review

Kuhlthau’s (1993) model of the information search process consists of three realms (affective – feelings; cognitive – thoughts, and physical – actions) which help describe the six stages of information search process: task initiation, topic selection, prefocus exploration, formulation, collection, and search closure. Later Kuhlthau (2007) introduced the seventh stage, assessment, but did not discuss it.

Zhou (2008) adapted Kuhlthau’s model for users in archives: 1) receiving the research assignment and one hour archival orientation, 2+3) general topic exploration and determination, 4) focused topic exploration and determination, 5) information collection, and 6) writing. We agreed that one could see searching for archival information as an information search process in a particular discipline and expected that this model could be applied to the archival environment in SI and BH. This expectation was confirmed by the respondents to our question about the definition of information literacy in a preliminary study (Vilar and Šauperl, 2014). Most of our respondents said that ALA’s definition of information literacy could be applied to the archives.

Johnson (2008) also used Kuhlthau’s model, but based her model of contextual interaction also on three forms of knowledge necessary for work in the archives, which were first developed by Yakel and Torres (2003), and confirmed by Greene (2010) and Lymn (2014). These forms of knowledge are: 1) domain knowledge (knowledge of the topic studied, e.g. historical period, event or personality), 2) artefactual literacy (ability to see and analyse texts as if they were objects) and 3) archival intelligence, which consists of the knowledge of archival theory, practice and procedures, the ability to develop search strategies and understanding of the relationship between the representation of the document and the actual document (Yakel & Torres, 2003; Johnson, 2008).

The library and information science area offers a rich body of literature on information behaviour of students. Cole (2000) investigated 45 history doctoral students to see how they searched for information. He found that many students collected “names” of people, places and things and used them as access points to the primary and secondary materials. In a quantitative study of 305 masters students of different disciplines Heinström (2005) investigated the relationship between personality traits, study approach and information behaviour. She found that five personality dimensions – neurositicm, extraversion, openness to experience, competitiveness, conscientiousness – are connected with contextual factors and affect students' information behaviour. Rowlands et al. (2008) used a three-part study (literature review on the information behaviour of young people over the past thirty years, survey data mining, and deep log analysis of website visits) to see how the researchers of the future (born after 1993) were likely to access and interact with digital resources in 5-10 years' time. The purpose was to investigate the impact of digital transition on the information behaviour of the Google Generation and to guide library and information services to anticipate and effectively react to any new or emerging behaviours. The study found that much of the impact of ICTs on the young has been overestimated. Although young people demonstrated an apparent ease and familiarity with computers, they relied heavily on search engines, viewed rather than read and did not possess the critical and analytical skills to assess the information that they found on the web. Gunter et al. (2009) reviewed original and secondary research evidence from international sources to determine whether there is a younger generation of learners adopting different styles of information search behaviour from older generations regarding patterns of use of online technologies. This was followed by a study using log data from two digital journals libraries, and one e-book collection (Nicholas et al., 2009), to provide evidence on the actual information-seeking behaviour of students in a digital scholarly environment, and to compare student information-seeking behaviour with that of other academic communities. They found a distinctive form of information-seeking behaviour associated with students and differences between them and other members of the academic community: eg students constituted the biggest user group in terms of sessions and pages viewed, were more likely to undertake longer online sessions, were the most likely users of library links to access scholarly databases.

Drachen et al. (2011) surveyed 4,453 and interviewed 20 PhD students to investigate their information behaviour and its implications for library services. The study had several findings: existing services were sought, but not well known among users due to poor communication, journal articles were identified as the most important information source, material not easily available was often disregarded, since convenience of access was crucial (probably due to time pressure), Google was widely used during all stages but especially in the beginning of the search process, online library services were very much in use, unlike physical buildings, reference management software was not as widely used as could be expected, many methods were used for searching and keeping informed (which is something that develops significantly during the PhD), information research habits were often established long before the PhD studies, but developed further during the PhD process (but mostly without library support), and supervision and courses were requested from the library if efficient, effective, and tailored. UK’s largest study on the information behaviour of Generation Y doctoral students (Researchers of Tomorrow, 2012) surveyed 17,000 doctoral students from 70 universities at various stages in their study. Results show that doctoral students are increasingly reliant on secondary research resources (eg journal articles, books), move away from primary materials (eg primary archival material and large datasets), access to relevant resources is a major constraint for doctoral students’ progress, authentication access and licence limitations to subscription-based resources, such as e-journals, are particularly problematic, open-access and copyright appear to be a source of confusion for Generation Y doctoral students, rather than encouraging innovation and collaborative research. This generation of doctoral students operates in an environment where their research behaviour does not use the full potential of innovative technology. Doctoral students are insufficiently trained or informed to be able to fully embrace the latest opportunities in the digital information environment.

In a review of literature from Anglo-American sources on graduate students information behaviour (Catalano, 2013) it was confirmed that most students will use internet first, prefer to consult their professor/advisor, remote access is preferred though humanities students will use primary sources in archives (because archives are difficult to find or rarely available online), that students are not aware of the existence of library sources and services, and have an inflated perception of their search abilities, but computer and internet experience can contribute to effective information retrieval. Similarly, a review by Rubinić (2014) on disciplinary differences in students' information seeking and use, the impact of curriculum and wider context including learning and teaching, effects of personality attributes, and studies that focus on use of electronic information resources, found that students are generally one of the most investigated groups in the field of human information behaviour, but the field of students' information behaviour is difficult to draw into a coherent knowledge base. There are many studies of different aspects of information behaviour conducted over different groups of students. Rubinić’s paper presents some of the key conclusions and perspectives of selected studies. Studies in this field are conducted from the beginning of 1970's when the focus was on exploring the usage of library resources and services. During the last two decades the interest in students' library use and information behaviour in general has increased and the focus of research expanded. Rubinić also highlights research problems that authors suggest as topics for further studies.

Some studies researched student information seeking behaviour in archives. Toms and Duff (2002) investigated four history graduate students (using a diary as data collection technique) on their use of archives and archival finding aids. The study found that students most commonly use personal names and fond's hierarchical structure, their knowledge of searching techniques includes keywords, personal names, names of corporate bodies and that they benefit from archivist's advice. Prom (2004) researched 89 individuals (mostly graduate students), 22 of them novices, on their navigational strategies through finding aids and the efficiency with which they searched five different collections. The study found that experts and novices use different strategies and reach different results, novices need more time for retrieval as experts, and that archival and computer expertise are strong predictors of efficient use of online finding aids. Johnson (2008) found that archives users have three basic questions: Where shall I look? Inexperienced users start with Google. They are not aware that archival material is not there. Experienced users rely on the principle of provenance, look for the certain fonds and archives. What shall I say? Experienced users seek help from archivists. In a reference interview archivists stear experienced users in the right direction. What is that? Langage and script of the document may be problematic for users. The meaning of documents is not always obvious. A study by Scheir (2006) included nine adult novices (non-users, non-academics, non-historians) to analyse by what route users accomplished a given task, what elements on the site help or hinder them, their overall experience; four particular components: terminology, navigation, display, structure. Results indicate problems of inexperienced users in an archive: Archival jargon impedes access (terms difficult to understand: scope and content, creator, container list, extent, arrangement, bulk), hierarchy of fonds is not clear, and multilevel, contextual information of finding aids is not as self-evident to novice users as it is to archivists and interface creators. The paper offers some solutions for digital collection interfaces: A fixed frame on the left side of the screen helps with understanding and navigation through hierarchy. Long blocks of text should be replaced with bulleted lists. A study by Tibbo (2003) shows information practices of history professors which, we may assume, are to some degree transferred to students during their studies. 700 historians teaching at US universities were investigated on ways of locating primary resources for their research. The study found that traditional print sources are preferred for primary sources, local library catalogues for publications, e-mail is used for gathering information on material before visiting archives at another location, visiting websites of repositories to search for sources is more often used as search engines.

Other studies tackled students' information competences. Yakel and Torres (2003), which were already mentioned in our literature survey, identified the required three forms of knowledge for effective work with primary sources in a study of 28 graduate students, some with but most without archival experience. Daniels and Yakel (2010) investigated 8 graduate students, 11 undergraduate students, 5 academic historians, 9 genealogists, 10 reference librarians on their skills and knowledge necessary for high success rate in searching two different online finding aid systems. They found that influential factors were prior experience in archival research, ability to generate appropriate search terms, understanding of archival terminology, knowing search techniques (Boolean search and browser’s find functionality (crtl+f)), navigation through large amount of text. Results also show that average number of searches per question is 2.79 (not significantly different among groups), that most users had difficulties in using personal names and subject headings as a search terms and that students tend to be in the middle range of search success.

Third issue is user education in archives. Allison (2005) reviewed educational programmes for undergraduate students at archives, manuscripts and special collections departments of 85 US universities. Findings reveal problems with undergraduate education: damage and overuse of some collections, occasional crowding and disruption of reading rooms, increased demands on limited staff time particularly because students tend to expect quick answers and are not well-prepared for the challenges and time it takes to use these resources, increased and sometimes excessive photocopying requests. But also some benefits of undergraduate education were identified, as it teaches students about primary sources and prepares them for future research with original material. Impact of systematic user training is shown by Duff and Cherry (2008) who followed four professors and 69 students attending 4 orientation sessions given by an archivist in the Yale University Library Manuscripts and Archives. They found increase in use of personal papers and correspondence for coursework and other research from 59,4% to 70,5%, increase in use of photographs from 52,2% to 58,1%, and increase in confidence level: mean value from 4.1 before to 6.0 after the orientation session.

Zhou (2008) investigated the needs and information behaviour of students in archival setting and the role of class instructor and reference archivist in instructing students. A case study of one class of undergraduate students exploring history of the US in the 1960s followed their entire course to investigate these issues in each of the phases. Findings are: 1) Task initiation: Students expect that research topics would be provided by the instructor. Using primary resources is a big challenge. Preparation of students includes reading works on archival principles, practice, and brainstorming about potential assignment topics. One hour orientation was offered to learn the most important skill: using online finding aids to search the detailed descriptions of archival collections. Archivists' role was teaching artifactual literacy and archival intelligence. Yet some students believed that an archivist does not know their topic and cannot help them 2) General topic exploration: Students look at a large quantity of primary resources. They need knowledge of using archival description tools, searching strategy, how to interpret the records (what records mean compared to the primary resource). Important was archivists' help. 3) Focused exploration: There was more optimism, feelings of relief when students find an interesting topic. Their action was intensive note-taking. Most important skills are ability to interpret primary material and assess their value for one’s research topic, understanding records, think critically, and develop contextual knowledge.

Krause (2010) investigated 13 experienced archivists from university archives on their perception of their educational role in academic archives; specialized knowledge that archivists’ believe is necessary for successful work in the archives. Study found two kinds of special archivists' competences: knowledge of the primary sources, which they acquire through their work with archival material. They are usually involved in creating description of that material, finding aids and other descriptive aids for the collections, and also most frequently provide reference information and individual instruction; and navigation skills: due to knowing their primary sources archivists are most qualified to teach how to search and use them. The study also found that archivists want to share and induce enthusiasm about archival research (coming from unique materials, hunting for useful items, interpreting and making sense of found primary sources).

Research

Research problem and research questions

Following our initial argument that the development of archival digital collections should follow user needs, our research aim was to investigate students as archives users, as perceived from the perspective of archivists. As we show below, there are some basic statistical data on students in archives, but we were also interested to find out the opinions of archivists on this issue. Secondly, we were interested how archivists perceive students as users (their characteristics, competences, archivists' own competences and ways of working with students) and what is their opinion of draft student profile (presented in Draft profile of student user). As in both countries archival user study has not been done before, we decided that in this stage of research it is better to include only archivists who work with users. We are, of course, aware that direct inclusion of users is highly advisable, but we felt that prior to that a solid body of theory should be built.

Data from annual reports of public archives in SI show that use for legal or administrative purposes dominates in most archives, however among the researchers dominate students. Pavšič Milost (1996) reports that students from highschools (28%), primary schools (23%) and universities (17%) were most frequent visitors of the Regional Archives Nova Gorica in the period 1986-1995). Their research topics focused on local history and battles of Soča-Isonco in the World War 1914-1918 (more in Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battles_of_the_Isonzo). Similarly Anžič (1996) shows that students were the most frequent users of the Regional Archives Ljubljana. Their number centered around 200 annually, compared to 60 historians. Semlič Rajh (2006) shows that students were the most frequent users of the Regional Archives Maribor in the period 2000-2005 with 37% share of visitors. Most often they came from the Pedagogical faculty of the University of Maribor.

Slovenian legislation requires archives to offer researchers advice in selecting fonds and prohibits archivists from doing research instead of researchers. Regional archives also offer orientation to local schools of different level. Maček (2009) reports number of school groups which visited regional archives. The share of these groups was from 20 to 95 percent of visits per year in the period 2004-2007.

We have no similar statistics for BH. This may be partially due to a different organization of the state and partially to our limited access to their professional publications. We were able to find that in the Archives of Tuzla Canton the number slowly rises from 10 resarchers in 2002 to 31 in 2007 and 43 in 2014. In the same period also rises the number of students (using archives for their theses) from 2 in 2002 to 11 in 2007 and 21 in 2014 (Fetahagić, 2008; Šauperl et al., 2015b).

The overall aim of our study was therefore to gather additional information to help us shape a more detailed profile of student user and to verify whether the identified characteristics were adequate. As starting point we used the draft profile, described below.

Draft profile of student user

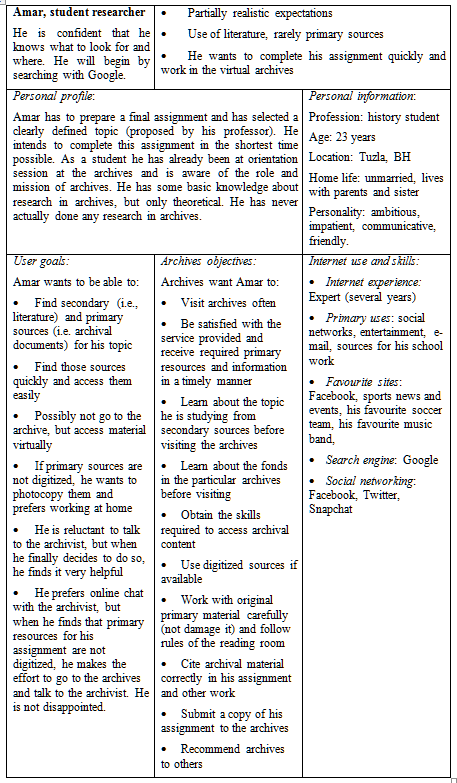

Development of our draft student profile was based on two theoretical models, Kuhlthau’s (1993, 2007) information seeking process and Johnson’s model of contextual interaction (2008). Both theoretical models (presented in short in chapter 2) were enhanced with information from literature review (both from library and information science and archival sources). The student user profile was given the name Amar, which was one of the popular male names in BH in recent years.

Amar is an average history student. He is enrolled in the third year of study at the History department of the Faculty of Philosophy. Amar attended lecture their professor gave on of the importance of archives as sources for research, but has no practical experience. He was assigned a topic by his professor and is determined to complete the assignment in the shortest time possible. He is excited and intimidated, because he has never worked in an archives before. He begins with Google but with very poor success. He is forced to visit the archives. His first visit to the archives reading room is frustrating. He scans through finding aids and collects large numbers of primary sources. Optimism is mixed with confusion and worry, when he does not understand what do primary sources mean. He looks at some documents, asks for photocopies. He is not certain what to do, he changes his mind frequently and finally asks for archivist’s advice. He realizes he will have to invest more time in his assignment as he planned. He is worried, the progress is slow, it is difficult to find appropriate sources, but with archivist’s help and his own persistence and determination, Amar is taking step by step in the right direction. He also talks to his colleagues and the professor. He feels some relief when he finally finds sufficient information to start writing. Scientific writing is not as hard for Amar, because he had to learn it in earlier years of study. He follows professor’s advice and university instructions. Although Amar found some primary sources, he gives more time and attention to secondary sources (published literature). Amar finishes his assignment on time and gets ready for presentation in the class. He is worried about the grade (Šauperl et al. 2014b).

Research questions

In accordance with the above research problem, our research was guided by the following questions:

- How frequent are students as users in the archive and how big is their ratio in the user population?

- What are the characteristics of students as archives users?

- What forms of work with students are required from the archivists?

- How do archivists perceive the profile of a student user (presented in Draft profile of student user)?

The answers to the first three questions were sought in the interviews and served to form a more detailed profile of student user, while the last question was the content of the survey and servied to verify the profile.

Methods

Interview

This was the first phase of our research and consisted of a pilot study and main study. In a pilot study (Vilar and Šauperl, 2014) six participants, divided into three groups responded to a survey: two archivists from Slovenia, two archivists from BH, one university teacher from Slovenia and one from Bosnia, both having at least basic knowledge of library and information science and archival theory.

This pilot study showed methodological drawbacks, already discussed by Vilar and Šauperl (2015): the questions were too complex for a survey, the topic was unusual, and both researchers were from library and information science, therefore foreign to respondents. We therefore changed our approach to an interview for the main study. This meant that the researcher was able to introduce herself and establish a more trusting rapport with each respondent. The questions were the same in the survey and in the interview. However, the interview was conducted as an unstructured interview and the researcher was able to explain and rephrase questions for each participant. The interviews were conducted in SI in spring and early summer of 2014 and in BH in September 2014. The participants were recruited at the conferences and purposive sampling was used. Six archivists from regional archives and three from the national archives participated in SI. There are six regional archives, which collect fonds from local and regional authorities and one state archive (collecting fonds from the state authorities) in Slovenia. They are all public. In BH there were four participants from the regional archives and one from a state archive. Based on the Dayton Agreement the organization of archives in BH is rather particular and difficult. There are seven cantonal, two entity and one state archive in BH, all public. The cantonal archives collect fonds from local and regional authorities, entity archives collect fonds from each entity’s governmental institutions and the state archives work from the state authorities. Eight participants were female, six male and they were mostly historians by profession. All were experienced professionals.

Interviews were transcribed and content-analyzed. The analysis was performed with the coding scheme based on the information seeking process of Carol Kuhlthau (1993). To come closer to the specifics of the archives, we also followed Johnson’s (2008) profile of the non-professional user. Coding was performed by both researchers. Results were frequently discussed with the entire group of collaborators on the bilateral grant (3 library and information science and 5 archival experts). Intensive discussion of interviews and coding results within the group ensured validity of our results.

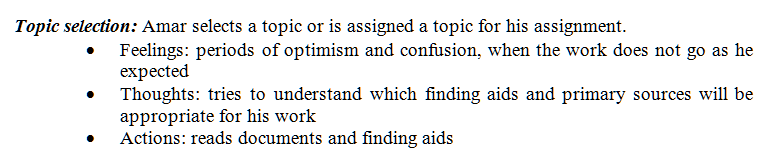

Survey

In the second phase, which followed the analysis of the results from the first phase, we did an open-ended survey among attendees of the international conference of archivists in Radenci, Slovenia, in April 2015. The survey containing the description of information search process (as seen below in the section 4.1.1) was distributed to the audience, consisting mostly of archivists. During our presentation (Šauperl et al., 2015a) the audience was asked to check whether they agree with our proposal regarding each of the stages of information search process by Kuhlthau. The questionnaire contained only short description of phases (example in Figure 1), but the oral presentation explained all the details. Eleven most motivated attendees collaborated. Six were from different Slovenian archives, two from Croatia and three from BH. Students visit ten of the archives represented by these participants. Seven of the participants work in the archives reading room regularly or occasionally.

Figure 1: Excerpt from the survey given to the conference attendees in 2015 to comment

Results and discussion: archivists about students as users

Interviews

Archivists gave differing answers regarding the numbers and ratios of student users: from 1%, 'not many', 'rather rare', 'less than other users', to 20%, one third, 35%, half, 'the largest group' (three answers). We noticed differing notions about this user group: five archivists considered them among the researchers (as some sort of junior researchers), while for nine archivists they were an independent user group.

Students mainly come from the field of history, some study law and journalism. They tend to be inexperienced and impatient. Their knowledge of the research topic and of history in general is inadequate (some archivists stressed that their knowledge is getting poorer by the year), as is their knowledge of the archive, organization of materials. Their motivation is often problematic, as many come to the archive only due to external requests (mainly by their professors). They are not independent, meaning that they are not able to use finding aids, are not able to formulate a precise question, and do not have experience in doing research. They gather and scan large quantities of records and documents, copy and compile them without formulating reliable selection criteria.

Archivists in such situations usually perform informal individual training adapted to a particular situation. This means that they talk to the student to help them clarify their actual need, help explain how to find the required documents and sometimes bring them to the user. Sometimes they only do basic advisory work, so that the student can practice archival research (usually this approach is co-ordinated with their professors). At the end of the project the student is supposed to be trained in the archival research process. Certain archives do planned group work, mainly in two forms: as practical work (co-ordinated with professors), and workshops, presentations and similar activities done by the archives as forms of user training or promotion. Archivists stressed that work with the users requires a lot of their time and thorough preparation in which information on the users (such as age, study programme, information behaviour, previous knowledge on materials, languages, script) is very helpful, as are archivist's competences in areas such as pedagogy, psychology, use of ICT. Some archives also do promotion in the forms of TV shows, documentary films or participate in social networks (such as Facebook).

When our basic theoretical model is compared to participants’ descriptions of users’ characteristics, we can see that they are aligned, namely, the archivists’ descriptions do not differ between the two countries. Because the characteristics of the student profile were developed from the Anglo-American literature, of which our respondents were unaware, we may assume that students in BH and SI have very similar information seeking behaviour as students in the Anglo-American countries.

Profile of the student as user of archives

On the basis of our draft theoretical model of student user, Kuhlthau's and Johnson's models, and the results of the interviews, we shaped a more detailed model of student user (Table 1) and elaborated on his information seeking process.

Table 1: Profile of student as archives user

Amar's information seeking process:

- Task initiation – Amar selects his assignment topic from a list provided by the professor or is assigned a topic by the professor. He is a beginner, who has never done any research in the archives before. He has also just a limited knowledge of the research topic.

- Feelings – Amar is actually quite confident he will find answers in one document or book and complete his work quickly. He is annoyed when he is not able to find digitized material and has to visit the archive. Only when the reference archivist explains research process in the archive Amar begins to worry.

- Thoughts – Amar thinks he knows exactly how to start searching. He thinks his work will be smooth and quick. He knows he can rely on his professor but thinks that archivists are only administrators, who cannot help. When he is able to change that perception, he thinks archivists are very helpful.

- Actions – Search begins with browsing Google and brings no useful results. Amar then remembers the professor instructed them to start by reading 1) published literature on the topic, and 2) archival finding aids. Although he may not understand immediately that regional archives hold documents from a certain region, he expects that professor would not send them to do research in another city. Fortunately for Amar the two things coincide.

- Topic selection – Amar has selected his assignment topic in the earlier stage, but has only in this stage decided on the topic he intends to search for.

- Feelings – A brief period of optimism is followed by confusion when search process proves to be rather complicated and difficult. Amar is not certain how to evaluate relevance of retrieved items.

- Thoughts – Amar is able to understand literature he is able to find but does not understand information in archival finding aids. Most of the time he does not understand what does the retrieved information mean. He has also difficulties in understanding original documents. They are not giving him direct answers to his research questions and that confuses him.

- Actions – Amar reads literature and looks at archival finding aids. He is also reading the first documents but is not able to understand them entirely. He asks the archvist what he should do with the document and what he should write from them. He scans widely through documents and frequently changes courses. Archivists advice is always helpful but the entire experience quite overwhelming.

- Prefocus exploration – Even without experience Amar becomes aware that his research will take more time and effort. His persistent and optimistic character now enable him to continue his work.

- Feelings – Amar is impatient and hopes that his work will soon be finished successfully. He is finding some information but is uncertain, when some information seems to be missing.

- Thoughts – Work does not going as planned. Ne thinks his research should be completed, yet he has still not found relevant documents and information. Some information is found, but not just what he wanted. The archivist is helping and encouraging him.

- Actions – Amar is reading carefully from selected documents, makes notes and analyses them. He compares documents with literature. He talks to his colleagues, the professor and the archivist.

- Formulation – Amar decides to stop searching for new documents and begins writing his assignment.

- Feelings – He is satisfied with information found. He believes it is sufficient for his assignment. He is not paying much attention to the type and quality of sources found.

- Thoughts – Amar is studying how to write the assignment, how to compose the required information. He is using experience from previous assignments. Methodology of scientific work and writing was explained by the professor and archivist, but it made much less sense then as now.

- Actions – When writing Amar includes more literature as primary sources. When he does not uncerstand primary sources he asks the archivist for advice. He also returns to primary sources.

- Collection – Amar writes his work and tries to form a consistent story based on sources found. Following instructions he is able to prepare his assignment in the correct form.

- Feelings – Relief and satisfaction with the accomplished task is mixed with anxiety about professors evaluation and grade.

- Thoughts – Research in archives is not easy. It also takes time. Amar has changed his perception during this assignment and learned new knowledge and skills.

- Actions – Amar is striving to write a good assignment. He is aware that citation of sources is very important and pays special attention to that.

- Search closure – Amar submits his assignment.

- Feelings – Excited and relieved because the assignment is complete.

- Thoughts – Research is not easy but it is interesting and Amar will not hesitate to take a similar assignment again.

- Actions – Amar is preparing the presentation of his assigmnet before his class. Possibly he will accept professors suggestion to submit it to the student or scientific journal at the national level.

- Assessment – Amar is nervous about his presentation to the class and professor’s grade.

- Feelings – Amar is aware that professor’s proposal to submit his assignment for publication means a good grade, but is still worried about his classmates’ reaction and also about the publication process.

- Thoughts – He thinks of the changes he will have to make to the assignment before publication and is considering advice form his professor and older colleagues, who have already published.

- Actions – Amar presents his work to the class and submits his work for publication.

Survey

Six respondents (of eleven) contributed more comments in the survey (all working in the reading room) and five just checked or wrote that they agree.

Task initiation was confirmed by all participants. Archivist No. 1 added that feelings of uncertainty come only after s/he explains to the student what is available. The archivist then advises to his/her best abilities. Archivist No. 5 also agreed with our profile, but added that some students believe they will find one archival document which will exactly answer their question and the work will be finished.

Topic selection was confirmed by all participants. Archivist No. 1 commented, that s/he sometimes needs to encourage student to continue the work. Archivist No. 3 wrote that mixed feelings of optimism and confusion in this stage are the normal part of research. Archivist No. 5 added that in this stage students also ask what they should do and how they should work. Archivist No. 6 usually experiences requests for assistance in this stage, while archivist No. 11 believes that this assistance is very helpful to the student.

The stage, prefocus exploration was confirmed by 9 archivists. Archivist No. 1 said that also not finding information is information. S/he added that the student in this stage thinks about connection between his or her findings and results of previous results found in published literature. Archivist No. 3 said that confusion, which occurs when the student does not find some information can be relieved by professor’s or archivist’s help. Archivist No. 4 did not agree with our statement, that the student is worried about missing information or documents. S/he did not elaborate on this but maybe s/he thought that the student is not experienced enough to be able to understand that some information is actually missing. Archivist No. 11 said that large quantities of primary material have to be looked at frequently and by all researchers.

The fourth stage, formulation also caused more comments from participants. The model was confirmed by 10 participants. Archivist No. 5 did not agree entirely. S/he wrote that the archivist has to remind the student to also report previous findings from published research. S/he commented that students seem to forget this even when they are used to scientific writing through other assignments. Archivist No.1 added that students like to share their excitement in this phase with others. They frequently tell him/her about the exciting documents they have found. Archivist No. 6 added that the student needs to consult the professor and archivist earlier, not in this stage of work.

The fifth stage, collection was confirmed by all eleven participants. Archivist No. 1 added that students seem to be most happy at this stage. S/he can see that students find new topics for new research projects. At this stage he usually helps students make correct citations to the fonds and documents used in the assignment. Archivist No. 11 added that all researchers frequently tell that research in archives takes long time.

The entire presentation lasted about 10 minutes, but the response to the last phase, search closure, did not receive least attention. It was confirmed by nine participants without comments. While archivist No.1 wrote that publication is certainly in place, archivist No. 4 wrote, that only publication in a student journal is appropriate. The same archivist also corrected the feelings description from »agitated« to »excited and relieved«. The assessment phase, which was not elaborated by Kuhlthau, was not tested in this survey.

Conclusions

Our previous research involved developing models of typical archives users, among them the typical student. The literature which we reviewed mostly came from the Anglo-American world where most of archives user research was done. The intention of the current study was to verify these models through surveys and interviews of archivists from Slovenia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. In our findings we show the convergence of both approaches, one coming from literature review, and the other coming from Bosnian and Slovenian archivists,. We believe that this convergence is interesting because it indicates that students have similar needs and habits regardless of geographical location and type of information system.

After our study was finished we identified two new literature review papers (Rhee, 2015; Katuu, 2015). The two reviews provided a kind of triangulation, because we found that we did not miss important studies in our earlier literature review. According to Lincoln and Guba (1985) and Marshall and Rossman (1995) soundness of qualitative research project has to be discussed through four points:

- Credibility: We had three sources of data: literature review from two disciplines, survey and interview of fourteen archivists from SI and BH, and survey of presentation audience with eleven respondents, all archivists. Data was perceived through the lenses of the two models, Kuhlthau’s and Johnson’s, which gave us the basic coding scheme. Both researchers carefully observed inconsistencies or data that would not fit the model.

- Transferability: We worked with literature from Anglo-American countries and collected data from BH and SI. Samples seem to be small, but they in fact include large proportion of the population.

- Repetition: The results were obtained by two repetitions of data gathering and analysis.

- Objectivity: Although this research project was mostly conducted by the two authors, we had numerous discussions with colaborators in the bilateral grant, a combination of ILS and archives experts.

This model of the student as user of archives rises several issues. One is promotion of archives. Are archives willing to promote their services and are they able to performe those services if the number of visitors rises? Many of the public archives in SI and BH have made large investments in promotion, and can also serve increased number of visits, but not all are able to do so because of serious limitations in space. The second issue is user education (archival literacy). Because archivists are aware of the need for this specific knowledge, they invest much effort into individual education of users. They teach them how to conduct research in their fonds. Some archives also offer lectures and presentations, others prepare TV shows for promotion of their services and fonds. Some archives are also active in social networks such as Facebook. Facebook and similar social networks may be the most appropriate tool for reference work for the student, because they are heavy users of such networks. It offers possibilities to help them online. The third issue is the role of the schools. How are they ready to integrate some of the possibilities offered by archives. Gilliland (1998) started writing about the advantages archives can offer to educational institutions. Many of the archives in SI and BH became aware of that without seeing Gilliland’s paper and are offering orientation sessions to different schools. But some interviewees commented that professors do not prepare students sufficiently for work in the archives and that they do not collaborate with the archivist before giving the assignment to the student. This means that the entire community still has to work. This is not only investment into research abilities of young people. It is also rising awareness of the importance of archives in protecting and ensuring human rights.

Acknowledgements

The authors express gratitude to the governments of the Republic of Slovenia and Bosnia and Herzegovina who financed the bilateral grant entitled "Guideliens for subject description of archival material" (BI-BA/14-15-031) within which this study was done. We also wish to thank all the experts who participated in this study.

About the authors

Polona Vilar is an Associate Professor in the Department of Library and Information Science and Book Studies at the Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana. She teaches and researches in the areas of information behaviour and information literacy, and related fields. She can be contacted at: polona.vilar@ff.uni-lj.si.

Alenka Šauperl is a Full Professor at the Department of Library and Information Science and Book Studies at the Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana. She teaches and researches in the areas of subject cataloguing and content description of documents in library and other collections. She can be contacted at: alenka.sauperl@ff.uni-lj.si.

References

- Allison, A.E. (2005). Connecting undergraduates with primary resources: A study of undergraduate instruction in archives, manuscripts and special collections. Unpublished master’s thesis. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina. Retrieved from: http://ils.unc.edu/MSpapers/3026.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFaj9uPn).

- Anžič, S. (1996). Uporabniki arhivskega gradiva v Zgodovinskem arhivu Ljubljana. In: 17. Posvetovanje Arhivskega društva Slovenije, Koper, 23.-25. Oktober 1996. pp. 59-61. Koper: Pokrajinski arhiv Koper

- Case, D.O. (2012). Looking for information: a survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behavior. (3rd ed). Bingley: Emerald

- Catalano, A. (2013). Patterns of graduate students’ information seeking behaviour: a meta-synthesis of the literature. Journal of Documentation, 69(2), 243-274.

- Cole, C. (2000). Inducing Expertise in History Doctoral Students via Information Retrieval Design. The Library Quarterly, 70(1), 86-109.

- Daniels, M. G. & Yakel, E. (2010). Seek and you may find: successful search in online finding aid systems. The American Archivist, 73(2), 535-568. Retrieved from http://americanarchivist.org/doi/pdf/10.17723/aarc.73.2.p578900680650357 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFapXZcF).

- Drachen, T. M., Larsen, A. V., Gullbekk, E., Westbye, H. & Lach, K. (2011). Information behaviour and practices of PhD students. København: Universitets Bibliothek; Oslo, University Library; Wien, Universität. Retrieved from https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/hprints-00599034/file/Information_behaviour_and_practices_of_PhD_students.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFb5LGOt).

- Duff, W.M. & Johnson, C.A. (2002). Accidentally found on purpose: information seeking behavior of historians in archives. Library Quarterly, 72(4), 472-496.

- Duff, W.M. & Torres, D.A. (2003). Archival intelligence and user expertise. American Archivist, 66(1), 51-78. Retrieved from: http://americanarchivist.org/doi/pdf/10.17723/aarc.66.1.q022h85pn51n5800 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFbBTYGX).

- Duff, W. & Cherry, J. (2008) Archival Orientation for Undergraduate Students: An Exploratory Study of Impact American Archivist, 71(2), 499-529.

- Fetahagić, H. (2008). Značaj i naučno-istraživačka kompomenta (funkcija) fondova i zbirki Arhiva Tuzlanskog kantona. Arhivska praksa, 11, 230-238. Retrieved from https://www.scribd.com/doc/295025465/ARHIVSKA-PRAKSA-11 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFbEo0I7).

- George, C., Bright, A., Hurlbert, T., Linke, E.C., St. Clair, G. & Stein, J. (2006). Scholarly use of information: graduate students' information seeking behaviour Information Research, 11(4), paper 272. Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/11-4/paper272.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFbP4zk4).

- Gilliland-Swetland, A. (1998). An exploration of K-12 user needs for digital primary source materials. American Archivist, 61(1), 136-57. Retrieved from: http://americanarchivist.org/doi/pdf/10.17723/aarc.61.1.w851770151576l03 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFbT49ch).

- Greene, M.A. (2010). MPLP: it's not just for processing any more. American Archivist, 68(2), 208-263. Retrieved from: http://americanarchivist.org/doi/pdf/10.17723/aarc.73.1.m577353w31675348 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFbbuEHp).

- Gunter, B., Rowlands, I. & Nicholas, D. (2009). The Google Generation: Are ICT Innovations Changing Information‐seeking Behaviour? Oxford: Chandos.

- Heinström, J. (2005). Fast surfing, broad scanning and deep diving: the influence of personality and study approach on students' information-seeking behaviour. Journal of Documentation, 61(2), 228-247.

- Johnson, A. (2008). Users, use and context: supporting interaction between users and digital archives. In: L. Craven (ed.), What are archives? Cultural and theoretical perspectives: a reader (pp. 145-166). Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Katuu, S. (2015). User studies and user education programmes in archival institutions. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 67(4), 442-457.

- Krause, M.G. (2010). Undergraduate research and academic archives: instruction, learning and assessment. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan. Retrieved from: http://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/75841/mghetu_1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFbfM7x2).

- Kuhlthau, C. C. (1993). Seeking meaning: a process approach to library and information services. Norwood, NY: Ablex.

- Kuhlthau, C. C. (2007). Reflections on the development of the Model of the Information Search Process (ISP): excerpts from the Lazerow Lecture, Univ. of Kentucky, April 2, 2007. JASIST Bulletin, (June/July 2007). Retrieved from: https://www.asis.org/Bulletin/Jun-07/kuhlthau.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFbjeBwF).

- Lincoln, Y.S. & Guba, E.G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Lymn, J.A. (2014). Queering archives: the practices of zines. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Technology, Sydney, Australia. Retrieved from: https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/29211 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFbmdv7q).

- Maček, J. (2009). Pregled dela v slovenskih državnih regionalnih arhivih. In: S. Tovšak [et al.] (ed.), Tehnični in vsebinski problemi klasičnega in elektronskega arhiviranja: Arhivi v globalni informacijski družbi (pp. 39-54). Maribor: Pokrajinski arhiv.

- Marshall, C. & Rossman, G.B. (1995). Designing qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Nicholas, D.; Clark, D.; Rowlands, I. & Jamali, H. R. (2009). Online use and information seeking behaviour: institutional and subject comparisons of UK researchers Journal of Information Science, 35(6), 660-676.

- Pavšič Milost, A. (1996). Uporabniki arhivskega gradiva v Pokrajinskem arhivu v Novi Gorici. In: 17. Posvetovanje Arhivskega društva Slovenije, Koper, 23.-25. Oktober 1996. pp. 53-54. Koper: Pokrajinski arhiv Koper.

- Prom, C.J. (2004). User Interactions with Electronic Finding Aids in a Controlled Setting, American Archivist, 67(2), 234-68. Retrieved from http://americanarchivist.org/doi/pdf/10.17723/aarc.67.2.7317671548328620 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFbtiGBV).

- Researchers of Tomorrow. (2012). London: JISC, British Library. Retrieved from http://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20140614040703/http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/publications/reports/2012/Researchers-of-Tomorrow.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at ttp://www.webcitation.org/6lFbx78um).

- Rhee, H.L. (2015). Reflections on archival user studes. Reference and User Services Quarterly, 54(4), 29-42. Retrieved from: https://journals.ala.org/rusq/article/view/5707 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFc0dMlH).

- Rowlands, I., Nicholas, D., Williams, P., Huntington, P., Fieldhouse, M., Gunter, B., … Tenopir, C. (2008). The Google generation: the information behaviour of the researcher of the future. Aslib Proceedings, 60(4), 290-310.

- Rubinić, D. (2014). Information behaviour of university students: a literature review. Libellaruim, 7(1). Retrieved from http://www.libellarium.org/index.php/libellarium/article/view/201/229 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFc8fdSS).

- Semlič Rajh, Z. Dostop do gradiva v knjižnicah in arhivih ter njegova uporaba. Unpublished master’s thesis. Ljubljana, Slovenia: University of Ljubljana.

- Šauperl, A., Vilar, P., Šabotić, I. & Semlič Rajh, Z. (2014a). Uporabnikov pogled na arhiv in popise arhivskega gradiva v arhivskih informacijskih sistemih. In: I. Fras … [et al.] (ed.), Tehnični in vsebinski problemi klasičnega in elektronskega arhiviranja: Arhivi v globalni informacijski družbi (pp. 171-200). Maribor: Pokrajinski arhiv. Retrieved from http://www.pokarh-mb.si/uploaded/datoteke/radenci2014/17_sauperl_2014.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFcHUkpW).

- Šauperl, A., Vilar, P., Žumer, M., Semlič Rajh, Z., Šabotić, I., Isić, S. & Selimović, S. (2014b). Teoretski pogled na korisnike arhiva. Arhivska praksa, 17, 263-280. Retrieved from http://www.arhivtk.ba/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/ARHIVSKA-PRAKSA-17.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFcJclMk).

- Šauperl, A., Vilar, P., Žumer, M., Semlič Rajh, Z., Šabotić, I., Isić, … Zulić, O. (2015a). Arhivisti o uporabnikih arhiva. In: I. Fras … [et al.] (ed.), Tehnični in vsebinski problemi klasičnega in elektronskega arhiviranja: Arhivi v globalni informacijski družbi (pp. 111-121). Maribor: Pokrajinski arhiv. Retrieved from http://www.pokarh-mb.si/uploaded/datoteke/Radenci/radenci2015/111-121_sauperl_2015.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFcLnXwD).

- Šauperl, A., Fetahagić, H., Vilar, P., Žumer, M., Semlič Rajh, Z., Šabotić, I., … Tinjić, A. (2015b). Korisnička pitanja: primjer Arhiva Tuzlanskog kantona. Arhivska praksa, 18, 302-317. Retrieved from http://www.arhivtk.ba/ap18.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFcOdjTt).

- Scheir, W. (2006). First Entry: Report on a Qualitative Exploratory Study of Novice User Experience with Online Finding Aids Journal of Archival Organization, 3(4), 49-85.

- Tibbo, H.R. (2003). Primary history in America: how U.S. historians search for primary materials in the dawn of the digital age. American Archivist, 66(1), 9-50. Retrieved from http://americanarchivist.org/doi/pdf/10.17723/aarc.66.1.b120370l1g718n74 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFcRebE3).

- Vilar, P. (2005). Informacijsko vedenje: modeli in koncepti. Knjižnica, 52(1), 41-61. Retrieved from http://revija-knjiznica.zbds-zveza.si/Izvodi/K0512/Vilar.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFcd4cft).

- Vilar, P. & Šauperl, A. (2014). Archival literacy: different users, different information needs, behaviour and skills. In: Information literacy: lifelong learning and digital citizenship in the 21st century: Second European Conference, ECIL 2014, Dubrovnik, Croatia, October 20-23, 2014: Proceedings. pp. 149-159. Berlin: Springer.

- Vilar, P. & Šauperl, A. (2015). Archives, Quo Vadis et Cum Quibus?: archivists' self-perceptions and perceptions of users of contemporary archives. International journal of information management, 35(5), 551-560.

- Yakel, E. & Torres, D. A. (2003). AI: Archival intelligence and user expertise. The American Archivist, 66(1), 51-78. Retrieved from http://americanarchivist.org/doi/pdf/10.17723/aarc.66.1.q022h85pn51n5800 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFdpQDOU).

- Zhou, X. (2008). Student archival research activity: an exploratory study. American Archivist, 71(2), 476-498. Retrieved from: http://americanarchivist.org/doi/pdf/10.17723/aarc.71.2.n426270367qk311l (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6lFck04xG).