Late, lost, or renewed? A search for the public sphere in public libraries

Michael M. Widdersheim

Introduction. This theoretical and historical paper problematizes applications of the public sphere concept to the study of public libraries. By working through identified problems, this study sharpens the theoretical ideas of public library research, reveals new research directions, and speculates on how public library research could contribute to a new conception of the public sphere.

Methods. This paper uses conceptual analysis to test the applicability of the public sphere concept to the study of modern public libraries.

Analysis. This study compares and contrasts the meanings of the public sphere concept with empirical realities of public libraries.

Results. The liberal public sphere differs from the empirical realities of public libraries in terms of temporal and categorical locations. A considerable body of research related to public libraries that has accrued over several decades must therefore confront allegations of anachronism and anatopism.

Conclusion. Objections of anachronism and anatopism can be countered by either acknowledging multiple public sphere paradigms or by revising the substantive models of the public sphere. These strategies raise new research questions and suggest that further study of public libraries could contribute to a fuller understanding of the public sphere concept.

Introduction

The concept of the public sphere has been used to describe the social functions of public libraries internationally for several decades. The concept of the public sphere is most closely linked to the work of German philosopher and sociologist Jürgen Habermas, whose book The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere was published in German in 1962, Norwegian in 1971, and English in 1989 (Habermas, 1962, 1971, 1989a). Associations between the public sphere and lending libraries were first made in Structural Transformation (Habermas, 1989a, p. 51). The public sphere was then associated specifically with public libraries, first with pre-forms of public libraries (Thauer and Vodosek, 1978), then with post-war public library developments (Schuhböck, 1983, 1994). Associations between the public sphere and public libraries diffused to other geographies and languages as Structural Transformation became more widely read. Over the last two decades, numerous authors used the public sphere concept to describe public libraries in Europe, North America, and South America.

Associations between the public sphere and public libraries emphasize the similarities between the two. This focus reveals valuable insights about the social functions of public libraries: public libraries act as "communication centers to facilitate the generation of public opinion (Schuhböck, 1983, p. 211). Public libraries are nodes in a larger media network that forms the communicative infrastructure of society (Vestheim, 1997b, p. 122). As public spheres, public libraries support social policy initiatives, such as social inclusion (Williamson, 1998, 2000). In their roles as "information commons (McCook, 2004, p. 188), public libraries act as civic training grounds that prepare citizens for democratic society (Kranich, 2004, p. 282). As public sphere meeting places, public libraries build social capital (Audunson, Vårheim, Aabø, and Holm, 2007). It is said that the public sphere concept can serve as a framework and research agenda for the public library sector (Widdersheim, 2015a). As in the field of media studies, it seems that public library literature has witnessed a "rise and rise of the public sphere over the last two decades (Lunt and Livingstone, 2013, p. 87).

While associations between the public sphere and public libraries have been insightful, fixation on their similarities obscures important differences. The purpose of this paper is therefore to reveal these differences in order to show why associations between the public sphere and public libraries are problematic. To do this, this paper uses conceptual analysis as a methodological approach. Conceptual analysis is

a technique that treats concepts as classes of objects, events, properties, or relationships. The technique involves precisely defining the meaning of a given concept by identifying and specifying the conditions under which any entity or phenomenon is (or could be) classified under the concept in question. (Furner, 2004, p. 233)

In this paper, the public sphere is the concept and public libraries are the objects in question.

The classification of public libraries as public spheres raises two main problems: anachronism and anatopism. Anachronism refers to a temporal misplacement, anatopism to a categorical one. These problems potentially undermine any association between public libraries and the public sphere. After describing these problems, this paper proposes two argumentative strategies to overcome them. The first strategy acknowledges multiple public sphere paradigms; the second strategy proposes a revision of the substantive paradigm.

This paper is significant because it contributes to a sustained, international conversation regarding the public sphere and its relation to public libraries. This paper includes a literature review in this area of unprecedented scope, an identification of original research questions, and creative solutions to a seeming impasse. Finally, this paper proposes that library research move beyond merely appropriating the public sphere concept and toward developing a new conception of it.

Literature review

The public sphere

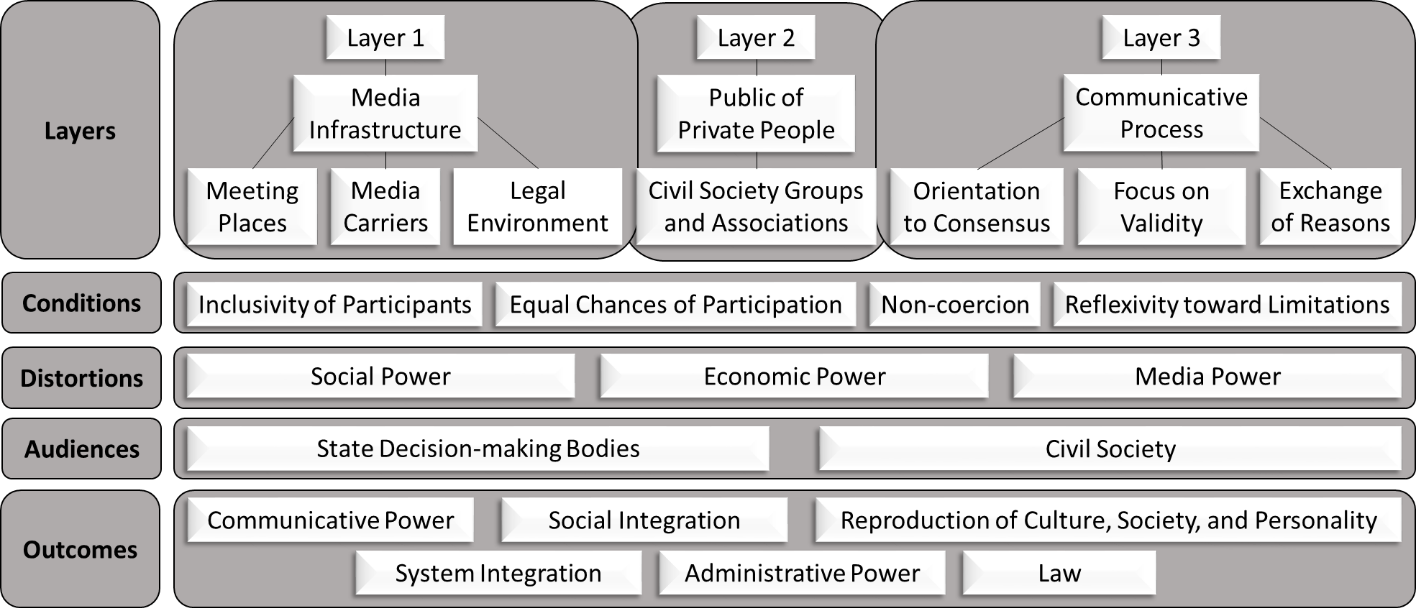

The public sphere is a complex social phenomenon composed of three layers. The first layer is media infrastructure. In the early-modern European account of the public sphere depicted in Structural Transformation, this media infrastructure consisted of meeting places such as salons, Tischgesellschaften (table societies), and coffee houses; media carriers such as journals, magazines, novels, newspapers, and their associated industries; and legal landscapes that protected free speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, and author and publisher rights (Habermas, 1989a). In contemporary contexts, the form of Layer 1 remains unchanged, but its content differs significantly: media carriers are less bounded by time and distance, meeting places are more diverse and distributed in nature, and the legal landscape has evolved to accommodate new technologies.

The second layer of the public sphere consists of embodied people—the actual public of private people who communicate in virtual or face-to-face forums. These people include civil society groups and individuals, but they also include political parties, lobbyists, unions, for-profit and non-profit corporations, experts and researchers, and politicians (Habermas, 1996, 2006)

The third layer of the public sphere is the communicative process itself, the symbolic exchange of meanings with an emphasis on reasons and an orientation to consensus. Public sphere communication can at any time thematize perceived distortions from social, economic, and media power (Dahlberg, 2001, 2004; Habermas, 2006).

These three layers—media infrastructure, people, and communication—form a public sphere. A public sphere is distinct from a mass, crowd, or other social collective because only a public approximates the necessary conditions of openness, common concern, and debate that apply across all three layers. The outcomes of a public sphere include the formation of communicative power and social integration. Communicative power affects state decision-makers; social integration affects the culture, society, and identity of members of civil society (Habermas, 1984, 1996). The complete public sphere structure is organized visually in Figure 1 below.

Public libraries and the public sphere: an overview

Associations between public libraries and the public sphere began in Germany following the publication of Structural Transformation (Habermas, 1962), then diffused throughout Europe, North America, and South America as the public sphere concept became more widely known. Table 1 below lists over 60 works that relate the public sphere concept with public libraries. The works were retrieved using a combination of techniques, including: literature searches for terms such as "public sphere and "public libraries in databases such as Library Literature and Information Science, Library and Information Science Abstracts, Library, Information Science, and Technology Abstracts, and Proquest Dissertations and Theses; grey literature searches in popular Web search engines using both English and non-English terms such as "Öffentlichkeit and "esfera pública; searches in proceedings of relevant conferences, such as Conceptions of Library and Information Science, Association for Information Science and Technology, and iConference; citation chaining; and word of mouth. The table is organized chronologically from oldest to most recent.

| # | Author(s) and year | Nation of focus | Type | Methods/Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Thauer and Vodosek (1978) | Germany | Book | History |

| 2 | Schuhböck (1983) | Germany | Article | Multiple case study |

| 3 | Greenhalgh, Landry, and Worpole (1993) | UK | Book | Survey/Interview/ Observation |

| 4 | Schuhböck (1994) | Germany | Article | History |

| 5 | Greenhalgh, Worpole, and Landry (1995) | UK | Book | Cultural criticism |

| 6 | Webster (1995) | UK | Book | Cultural criticism |

| 7 | Vestheim (1997a) | Norway | Thesis | History |

| 8 | Vestheim (1997b) | Norway | Article | Cultural criticism |

| 9 | Emerek and Ørum (1997) | Denmark | Article | History |

| 10 | Williamson (1998) | UK | Thesis | Interviews |

| 11 | Williamson (2000) | UK | Article | Cultural criticism |

| 12 | Ventura (2001) | Portugal | Thesis | Ethnography |

| 13 | Ventura (2002) | Portugal | Book | Ethnography |

| 14 | Leckie and Hopkins (2002) | Canada | Article | Ethnography |

| 15 | McCook (2003) | US | Article | Cultural criticism |

| 16 | Wiegand (2003a) | US | Article | Editorial |

| 17 | Wiegand and Bertot (2003) | US | Article | Editorial |

| 18 | Wiegand (2003b) | US | Article | Editorial |

| 19 | Buschman (2003) | US | Book | Cultural criticism |

| 20 | Alstad and Curry (2003) | Non-specific | Article | Cultural criticism |

| 21 | Buschman (2004) | US | Article | Cultural criticism |

| 22 | Leckie (2004) | Canada | Article | Conceptual |

| 23 | Kranich (2004) | US | Chapter | Cultural criticism |

| 24 | McCook (2004) | US | Chapter | Textbook |

| 25 | Frohmann (2004) | Canada, US, UK | Review | Cultural criticism |

| 26 | Audunson (2005) | Non-specific | Article | Conceptual |

| 27 | Aabø (2005) | Non-specific | Article | Conceptual |

| 28 | Andersen (2005) | Non-specific | Article | Cultural criticism |

| 29 | Buschman (2005a) | US | Article | Cultural criticism |

| 30 | Buschman (2005b) | US | Article | Cultural criticism |

| 31 | Ljødal (2005) | Norway | Report | Interviews |

| 32 | Black and Hoare (2006) | UK | Book | History |

| 33 | Buschman (2006) | US | Article | Cultural criticism |

| 34 | Taipale (2006) | Finland | Paper | Conceptual |

| 35 | Andersen and Skouvig (2006) | Denmark | Article | Conceptual |

| 36 | Leckie and Buschman (2007) | US and Canada | Chapter | Conceptual |

| 37 | Rothbauer (2007) | Non-specific | Chapter | Cultural criticism |

| 38 | Newman (2007) | UK | Article | Interviews |

| 39 | Buschman (2007) | US | Article | Cultural criticism |

| 40 | Audunson et al. (2007) | Norway | Paper | Survey |

| 41 | Vårheim, Steinmo, and Ide (2008) | OECD countries | Article | Survey/Interview |

| 42 | Burnett and Jaeger (2008) | US | Article | Conceptual |

| 43 | Braman (2009) | US | Chapter | Conceptual |

| 44 | Taipale (2009) | Finland | Thesis | Multiple case study |

| 45 | Jaeger and Burnett (2010) | US | Chapter | Conceptual |

| 46 | Aabø, Audunson, and Vårheim (2010) | Norway | Article | Survey |

| 47 | Burnett and Jaeger (2011) | US | Article | Conceptual |

| 48 | Buschman (2012) | US | Book | Cultural criticism |

| 49 | Aabø and Audunson (2012) | Norway | Article | Ethnography |

| 50 | Buschman (2013) | US | Article | Cultural criticism |

| 51 | Kranich (2013) | US | Article | Cultural criticism |

| 52 | Jaeger et al. (2014) | US | Article | Conceptual |

| 53 | Frota (2014) | Brazil | Article | Cultural criticism |

| 54 | Machado, Elias Junior, and Achilles (2014) | Brazil | Article | Cultural criticism |

| 55 | Trosow (2014/2015) | Non-specific | Article | Cultural criticism |

| 56 | McNally (2014/2015) | Non-specific | Article | Cultural criticism |

| 57 | Richards, Wiegand, and Dalbello (2015) | Non-specific | Book | History |

| 58 | Evjen (2015) | UK, Denmark, Norway | Article | Interviews |

| 59 | Ingraham (2015) | UK | Article | Discourse analysis |

| 60 | Widdersheim and Koizumi (2015a) | US | Paper | Content analysis |

| 61 | Widdersheim (2015b) | US | Poster | Content analysis |

| 62 | Widdersheim and Koizumi (2015b) | US | Paper | Content analysis |

| 63 | Widdersheim (2015a) | Non-specific | Article | Conceptual |

| 64 | Widdersheim and Koizumi (forthcoming) | US | Article | Content analysis |

The above literature that associates the public sphere with public libraries can be organized into two main categories. In the first category are studies of how the public sphere materializes or manifests in public libraries. These studies explore how public libraries facilitate public sphere communication and what effects this communication has. In the second category are studies of how public libraries are themselves issues of public sphere communication.

Public libraries as public sphere infrastructure

In the first category of literature, public libraries represent Layer 1 of Figure 1 above: the media infrastructure of the public sphere. In other words, public libraries have replaced the coffee houses, salons, and table societies of Enlightenment-era Europe. Public libraries are the "windows of an information society (Ventura, 2002), its public sphere "platforms. As media infrastructures, public libraries act as media suppliers, virtual and physical meeting places, and protected spaces for communicative exchange.

Existing literature about the public sphere and public libraries emphasizes various facets of this infrastructure. One salient facet is the public library’s role as a physical meeting place. Several studies survey how public libraries act as meeting places (Aabø and Audunson, 2012; Aabø et al., 2010; Audunson et al., 2007). In these studies, the asserted benefits of public sphere communication in public libraries are positive by-products of the communicative process itself, such as the creation of civic culture (Kranich, 2004, 2013; McCook, 2003, 2004) and social capital (Audunson et al., 2007).

Existing literature also emphasizes the openness and diversity of media resources of public libraries. Webster (1995) and Buschman (2003) foreground public libraries’ collections that contain diverse viewpoints and are in principle open to anyone. At the same time, it is said that public libraries are not neutral in the kinds of communication they support (Andersen, 2005; Andersen and Skouvig, 2006). There is a strong current in the literature that expresses scepticism about whether the types of culture and messages that are transmitted through libraries are genuinely undistorted, whether they are not commercialized or hegemonic. Following Webster (1995), Leckie and Hopkins (2002) and Buschman (2003) express ambivalence about whether public libraries are too privatized and business-oriented to facilitate public sphere communication. Similar sentiments are expressed by Vestheim (1997a) and Taipale (2006, 2009).

Some studies describe public libraries as part of a larger media infrastructure for the formation of public opinion (Frota, 2014; Schuhböck, 1983). Widdersheim and Koizumi (2015a, 2015b) find that public libraries were used as a public sphere by civic groups, readings clubs, and communities. In their historical surveys of public library developments, Richards et al. (2015, p. 70) and Black and Hoare (2006, p. 7) remark that public libraries formed part of the public sphere infrastructure of modern societies.

There are several confusions in this category that are worth noting. First, in some studies, the noun public sphere (der Öffentlichkeit) in the public opinion and public communication sense is sometimes confused with the adjective public (öffentlich) in the sense of government ownership. For example, Webster (1995, p. 176) states that public libraries are public sphere institutions because they are "publicly funded and "staffed by professional librarians. Similarly, Leckie and Hopkins (2002, p. 357) claim that "the library is becoming increasingly co-opted by multiple private interests, implying that public communication necessitates public funding. These descriptions are mistaken because a public sphere does not require tax-based, government management. Early public sphere meetings occurred in private clubs and salons in private homes. Not privatization and commercialization per se, but certain types of privatization and commercialization potentially distort the public sphere. A second confusion is between public communication and information transfer. Jaeger et al. (2014) states that "libraries, schools, and other public sphere organizations…exist specifically to ensure that information continues to move between the small worlds. Public sphere communication requires information exchange, but this condition alone is insufficient. The "information equals democracy assumption has been previously interrogated (Lievrouw, 1994). Reducing the public sphere to information transfer leaves no room for distinctions of information quality and use. Williamson (1998, 2000) makes a third mistake by associating the public sphere with service provision. Services provided by public libraries, such as those for job seekers, are not necessarily related to public sphere communication. Such an association seems to confuse social integration with system integration (Habermas, 1989b)

Public libraries as a public sphere issue

The second category of existing literature that associates public libraries with the public sphere focuses on how public libraries are the topic of public sphere communication. This literature discusses how public libraries have been or currently are legitimated by various groups in the public sphere. In some cases, public libraries were created due to popular pressure from civil society groups (Schuhböck, 1994, p. 218; Widdersheim, 2015b). Once institutionalized, public libraries themselves mobilize support on their behalf (Machado et al., 2014; Widdersheim and Koizumi, 2015b). Recent studies use interviews or discourse analysis to study how various stakeholders, such as politicians, civil society groups, and librarians legitimate public libraries in the public sphere (Evjen, 2015; Ingraham, 2015; Newman, 2007). Insofar as public libraries constitute public sphere infrastructure, discourse about that infrastructure is said to be a "metasphere of the library (Ingraham, 2015, p. 156). Emerek and Ørum (1997) and Vestheim (1997a) establish that this metasphere affected the historical development of public libraries in Denmark and Norway.

Problems of public sphere status in public libraries

Associations between the public sphere and public libraries yield a nuanced understanding of the social functions of public libraries; however, by focusing exclusively on the similarities between public libraries and the public sphere, existing literature inadvertently overlooks two significant differences.

Late: the public sphere and anachronism

The first significant difference between public libraries and the public sphere is that the liberal model of the public sphere is a historically-bounded concept. As it was described in Structural Transformation, the public sphere emerged in eighteenth-century France, England, and Germany following a general shift from feudalism to mercantile capitalism and a gradual growth of state bureaucracy. As a social-historical category, the public sphere represented an unfulfilled promise, an ideology that failed to materialize authentically even in its heyday in the mid-nineteenth century. By the mid-nineteenth century, due to economic and technological changes, the public sphere in the liberal sense began to collapse into a mediatized, power-ridden (vermachteten) public sphere, one that was "refeudalized by state and corporate interests to form a staged and acclamatory public (Eley, 1992; Habermas, 1989a, p. 195). Habermas is unequivocal regarding the temporal location of the liberal public sphere model described in the first half of Structural Transformation:

Although the liberal model of the public sphere is still instructive today with respect to the normative claim that information be accessible to the public, it cannot be applied to the actual conditions of an industrially advanced mass democracy organized in the form of the social welfare state. (Habermas, 1974, p. 54)

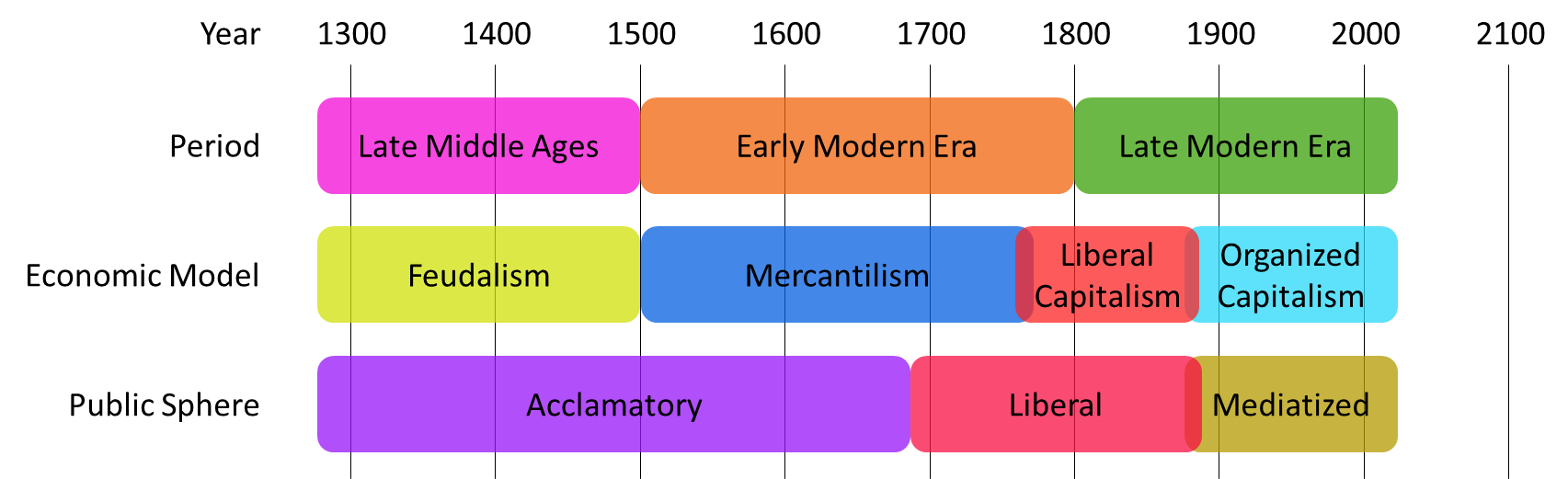

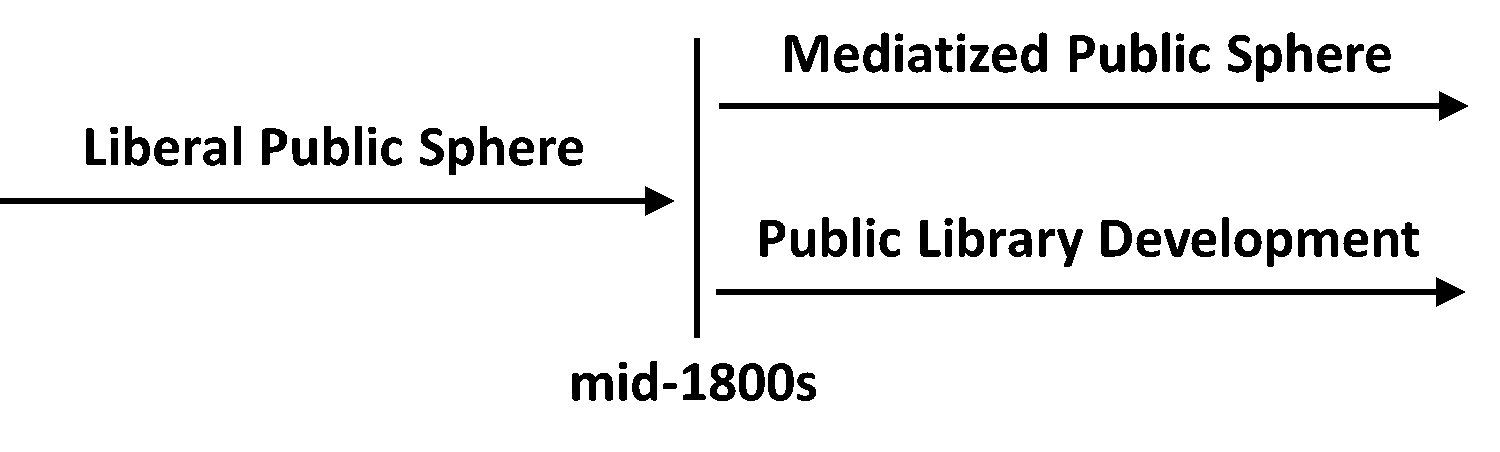

It is clear from this passage and from Structural Transformation that the public sphere only describes cultural dynamics that peaked around the mid-nineteenth century but did not last beyond the late nineteenth century (Habermas, 1989a). Figure 2 below shows a simplified historical transformation of the public sphere.

Figure 2: Simplified historical transformation of the European public sphere

The year 1850 is an important date for the purpose of this discussion because public libraries did not develop significantly in any nation before that date. Public libraries in this case refer to state-sponsored libraries, not libraries that are privately owned but open for public use, such as the Gebrauchsöffentlichkeit mentioned by Schuhböck (1994, p. 217) and Vestheim (1997b, p. 121). Table 2 below shows significant formative developments in public libraries internationally. The data in Table 2 is drawn from Richards et al. (2015).

| Nation | Significant early events in public library development |

|---|---|

| United Kingdom of Britain and Northern Ireland | Public Libraries Act of 1850 The Library Association founded in London (1877) |

| Denmark | State Libraries Agency (1882) Professional association established (1915) Public Libraries Act (1920) |

| Norway | Opening of Deichmanske Bibliotek (1898) Professional association established (1915) |

| Sweden | Establishment of state funding (1905) |

| Russia | Founding of public library by Liubov Borisovna Khavkina (1886) |

| Poland | Founding of public library in Warsaw by Zaluski brothers (1747); removed by Russia in 1795 Warsaw Philanthropic Society opens free readings rooms (1861) |

| Bulgaria | Law requiring all communities to form reading societies (1927) |

| Germany | Karl Benjamin established Sunday school with library open to public (1828); accepted as town library in 1833 Friedrich von Raumer established four public libraries in 1850 Book hall movement (Bücherhallenbewegung) started by Eduard Reyer and Constantin Nörrenberg (1895) |

| Czechoslovakia | Matica Slovenská founded in 1863 Martin (now the Slovak National Library in Slovakia) |

| Belgium | Willemsfond establishes public library opens in Ghent (1856) and small libraries across Flanders Davidsfonds establishes small libraries across Flanders (1875) Ligue de l’enseignement establishes small libraries with primary schools in Brussels (1864) |

| Netherlands | Libraries established at Utrecht (1892) and Dordrecht (1898) Central Association for Public Reading Rooms and Libraries established (1908) |

| France | Establishment of hundreds of small libraries run by volunteers (1860-1900) Eugène Morel publishes Bibliothèque (1908-1909) and begins training courses for librarians (1910-1913) |

| Italy | Antonio Bruni opens the first popular library in Prato (1861) Municipal libraries established in Milan (1867) and Turin (1869) |

| Spain | Small public libraries open (1869) |

| Portugal | Decree opens small public libraries (1870) |

| United States | Massachusetts passed legislation to fund a public library in Boston (1848); Boston Public Library opened in 1854 American Library Association formed (1876) New York Public Library established (1895) |

| Canada | Ontario (1882), Manitoba (1899), Saskatchewan (1906), Alberta (1907), New Brunswick (1929), Nova Scotia (1937), and Quebec (1959) adopt public library legislation |

Supposing that Table 2 above is correct, and that few significant public library developments occurred in any country before the mid-nineteenth century; and supposing also that Structural Transformation is correct that the liberal public sphere—as an empirical category tied to economic and cultural conditions—began to disintegrate around the mid-1800s, then the following question must be addressed: how can the public sphere describe public libraries when the public sphere began to collapse just as public libraries began to develop? Existing literature that associates the public sphere with public libraries must confront allegations of anachronism—the application of the public sphere concept to a period where it does not belong. Literature that associates the public sphere with public libraries appropriates the public sphere concept, but only incompletely: it fails to account for its temporal boundedness. The same literature that borrows the public sphere concept to describe public libraries in the late nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries also implicitly repudiates the claim that the public sphere is a temporally-bounded concept. How is it that contemporary public libraries can be classed as public spheres in a way that is non-illusory and non-ideological? It remains to be explained how public libraries can be associated with the public sphere in a non-anachronistic way.

Lost: the public sphere and anatopism

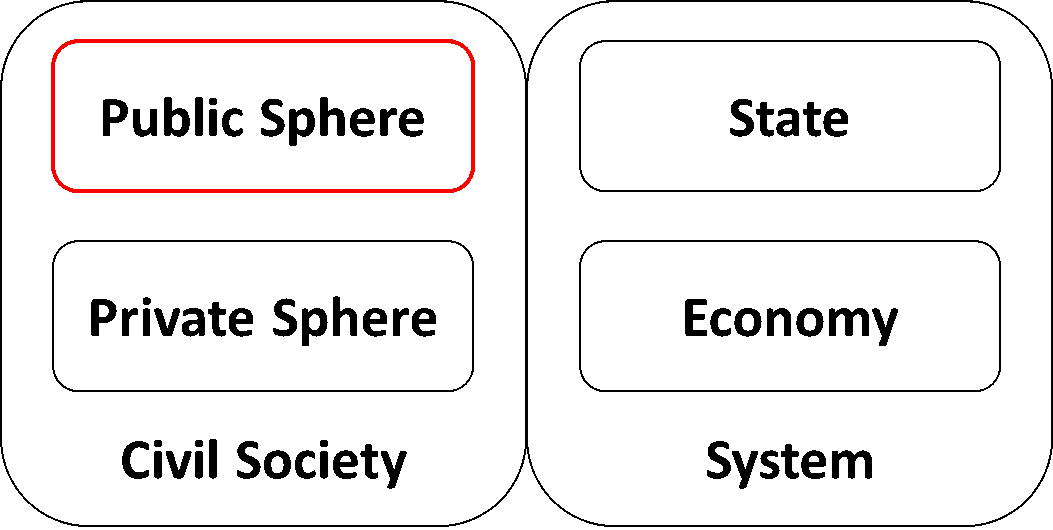

A second significant difference between the public sphere and public libraries, besides temporal location, is geographical location. Geography in this sense does not mean physical geography, it means categorical geography. Traditionally defined, the public sphere inhabits a space in civil society that mediates between civil society and the state. In this position, it affects both (Eley, 1992; Habermas, 1989a). The public sphere affects civil society through political-cultural critiques of everyday practices (Cohen and Arato, 1995), and it affects the state by influencing laws and legislation (Habermas, 1996). This in-between position of the public sphere, as a specifically non-state entity, is explained in Structural Transformation (Habermas, 1989a, p. 30). This conceptual geography is visualized in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Traditional location of the liberal public sphere

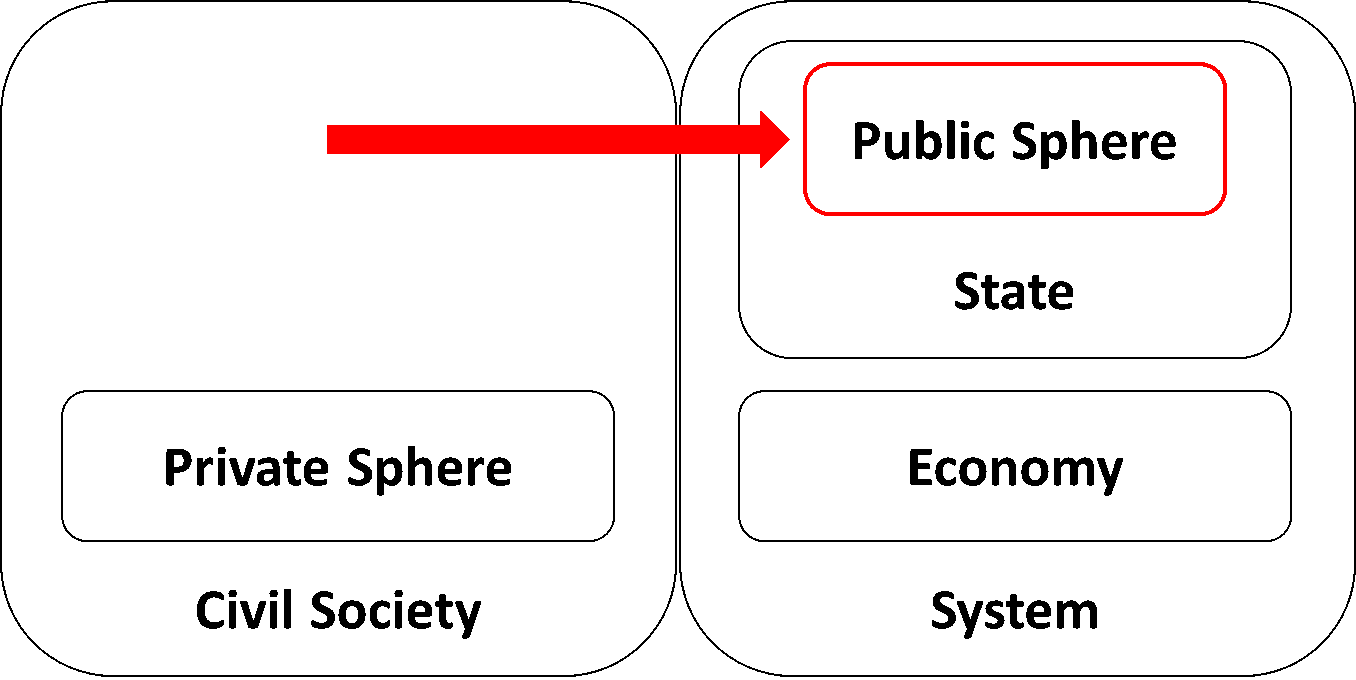

This conceptual geography differs significantly from the empirical reality of public libraries because public libraries are state authorities—they are state-owned, state-managed, and state-funded. It is true that public libraries vary in their specific relationships with the state (Joeckel, 1935; Usherwood, 1993): some are trusts, some are non-profit organizations, and others are municipal departments. Whatever the specific relationship to local governments, however, public libraries are by definition state-sponsored agencies. Many are funded by wealth transfer from the economy to the state, which is enforced through tax legislation. Because public libraries are state authorities, literature that associates the public sphere with public libraries must confront the objection of anatopism—the application of the public sphere concept to a categorical location where it does not belong. Associations between the public sphere and public libraries inadvertently shift the categorical location of the public sphere from civil society to the state. This anatopic shift is visualized in Figure 4. Existing literature has not explained how the public sphere concept can describe state authorities like public libraries without succumbing to objections of conceptual anatopism.

Figure 4: Anatopic shift of the public sphere in library literature

Renewed status? Accommodation strategies for the public sphere in public libraries

Problems of anachronism and anatopism are obscured in existing literature that associates the public sphere with public libraries. Because the problems have been overlooked, no solutions yet exist. The problems of anachronism and anatopism undermine a substantial body of literature about public libraries that has accrued over several decades. Existing literature would benefit from an explanation of how studies of public libraries could accommodate a public sphere conception while also avoiding objections of anachronism and anatopism.

Strategy 1: multiple public sphere paradigms

One strategy of accommodation is to recognize public sphere paradigms that are more flexible in terms of temporal and conceptual location. Existing literature largely appropriates the conception of the public sphere from Structural Transformation (Habermas, 1989a). This work actually contains two empirical conceptions of the public sphere: the liberal model that existed from the late eighteenth century to the late nineteenth century, on the one hand, and the power-ridden (vermachteten) model that began to form in the mid-nineteenth century and continues today (Habermas, 2006). These conceptions describe cultural and technological conditions, and because they make claims about the actual content of the public sphere, they are "substantive models of the public sphere (Fraser, 1990, note 34). Debates about the "existence of the public sphere implicitly work within the substantive paradigm (Leckie and Buschman, 2007, p. 13). It might be said that Structural Transformation also contains a normative or transhistorical model of the public sphere as well (Kramer, 1992), but this model actually developed in later works (Habermas, 1984, 1989b).

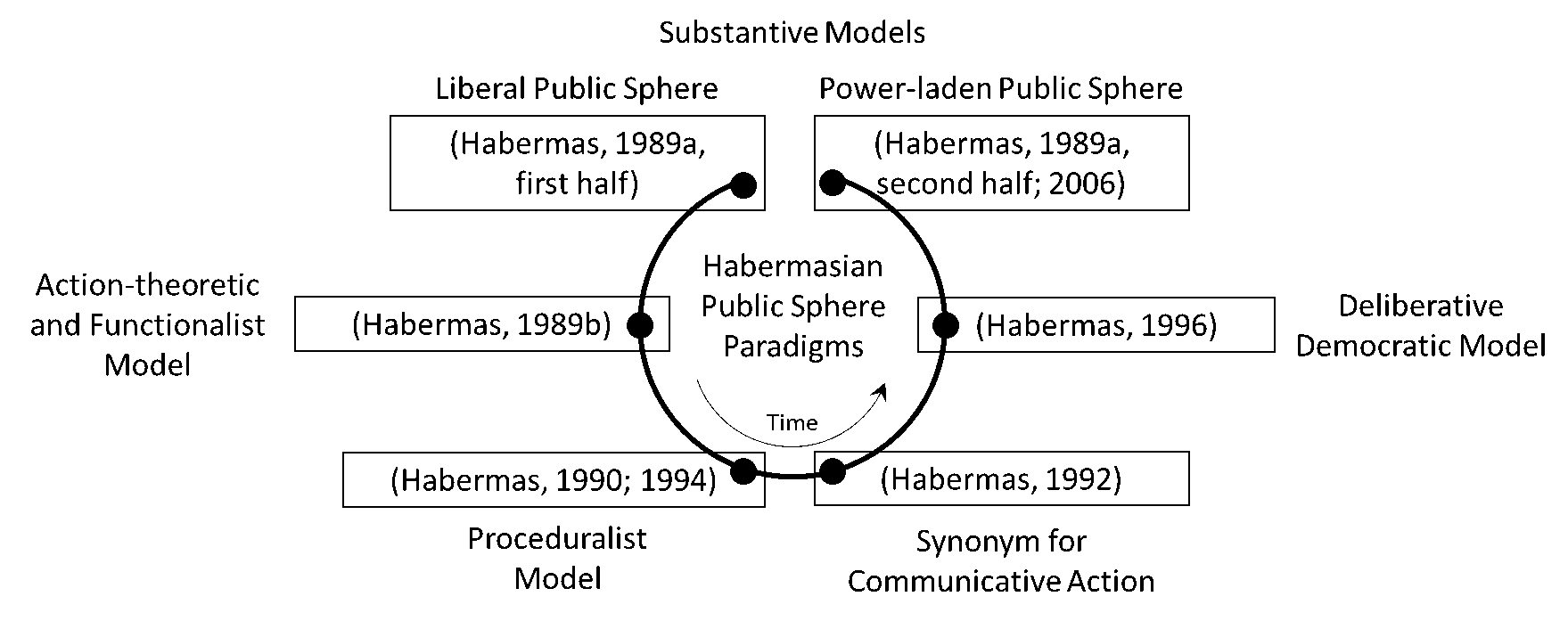

Substantive, empirical models only represent one possible paradigm. Since Structural Transformation, the public sphere has been used by Habermas in a discourse-theoretic and proceduralist way (Habermas, 1990, 1994), a functionalist or action-theoretic way (Habermas, 1989b), as a synonym for communicative action (Habermas, 1992), and in a normative political theory related to law and deliberative democracy (Habermas, 1996). Paradigms of the public sphere have therefore evolved and changed over time (Baxter, 2011; Johnson, 2006). One interpretation of these various public sphere paradigms is visualized in Figure 5 below. If Structural Transformation represents the first set of public sphere models, then over time several paradigms have emerged, coming "full circle with a return to the substantive paradigm (Habermas, 2006).

Figure 5: Habermasian public sphere paradigms

Literature that associates the public sphere with public libraries could better distinguish between different public sphere paradigms and apply those that are not tethered to temporal and conceptual locations. Existing literature mentions these alternative models: for example, the deliberative democracy model (Kranich, 2013; Vestheim, 1997b) and the action-theoretic model (Vestheim, 1997b); but these models have not been associated with public libraries in detail. That existing literature assumes a single, monolithic public sphere concept is belied by statements such as "the library also appears to be a part of the public sphere in the Habermasian sense (Aabø et al., 2010, p. 25). As Figure 5 shows, however, there is no single Habermasian sense. Alternative paradigms present attractive future research directions because, unlike the substantive and empirical models, normative, proceduralist, and ideal-typical models do not describe the culture of a particular place and time, but instead explain hypothetical rules and normative possibilities.

Strategy 2: revision of the substantive model

Besides recognizing and applying more flexible models of the public sphere, another strategy to accommodate associations between the public sphere and public libraries is to revise the conditions of the substantive paradigm. The traditional, substantive paradigm of the public sphere as described in Structural Transformation supposes that the liberal public sphere began to collapse in the mid-nineteenth century, forming a power-laden and mediatized version, one designed for manipulation and consumption training (Habermas, 1989a). Around this same time, public libraries began to develop internationally. These two processes are visualized in Figure 6 below.

Figure 6: Public sphere and public library trajectories

It is tempting to suppose, based on Figure 6, that the development of public libraries represents a continuation of the liberal public sphere in new garb, one parallel to but distinct from the mediatized public sphere. This is the basic argument of Vestheim (1997a, 1997b) and Emerek and Ørum (1997) in their historical accounts of public library developments in Norway and Denmark. Vestheim (1997a) and Buschman (2003) claim that the public sphere that had manifested in public libraries in Norway and the US, respectively, collapsed later. These histories, however, do not sufficiently acknowledge their conflict with the central thesis in Structural Transformation. A fuller explanation is still needed for how the public sphere "lived on in public libraries even as the public sphere, in general, collapsed otherwise, and why the public sphere shifted in location from civil society to the state (Leckie and Buschman, 2007).

Supposing that the public sphere "lived on in a substantive way in public libraries, then public libraries represent an exception that was overlooked by Habermas (1989a) in his general account of public sphere collapse. Perhaps the structural transformation of the media infrastructure sustained by public libraries followed an alternate trajectory. More detailed, cautious, and empirically-based arguments are needed that describe the public sphere in public libraries in a non-illusory and non-ideological way. Did the location of the public sphere shift from civil society to the state as the state grew in complexity and public/private intermingled? This is still an open question. Just as the mass-democratic social-welfare state began to provide material and bio-political infrastructure in the mid-nineteenth century, perhaps it also supplied the symbolic infrastructure for a distinct kind of public sphere. Such a thesis, if developed further, could contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the dynamics of public sphere conditions.

Conclusion

This paper used conceptual analysis to identify two differences between the public sphere concept and public libraries. The differences raise two problems, anachronism and anatopism. These problems are overlooked in existing literature and potentially undermine any association between the public sphere and public libraries. In order to address these problems, and in order to show how the public sphere concept might still apply to public libraries, this paper proposed two argumentative strategies. The first acknowledges a multiplicity of public sphere conceptions, and the second suggests a revision of the substantive paradigm. These strategies remain speculative and require further elaboration, but they raise several new research questions and contribute to an ongoing international conversation that is central to the public library field.About the author

Michael M. Widdersheim is a PhD candidate in the School of Information Sciences at the University of Pittsburgh, USA. He can be reached at mmw84@pitt.edu.

References

- Aabø, S. (2005). The role and value of public libraries in the age of digital technologies. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 37(4), 205-211. doi: 10.1177/0961000605057855

- Aabø, S., & Audunson, R. (2012). Use of library space and the library as place. Library & Information Science Research, 34(2), 138-149. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2011.06.002

- Aabø, S., Audunson, R., & Vårheim, A. (2010). How do public libraries function as meeting places? Library & Information Science Research, 32(1), 16-26.

- Alstad, C., & Curry, A. (2003). Public space, public discourse, and public libraries. Libres, 13(1).

- Andersen, J. (2005). Information criticism: Where is it? Progressive Librarian, 25, 12-22.

- Andersen, J., & Skouvig, L. (2006). Knowledge organization: A sociohistorical analysis and critique. Library Quarterly, 76(3), 300-322.

- Audunson, R. (2005). The public library as a meeting-place in a multicultural and digital context: The necessity of low-intensive meeting-places. Journal of Documentation, 61(3), 429-441. doi: 10.1108/00220410510598562

- Audunson, R., Vårheim, A., Aabø, S., & Holm, E. D. (2007). Public libraries, social capital, and low intensive meeting places. Information Research, 12(4).

- Baxter, H. (2011). Habermas: The discourse theory of law and democracy. Stanford, CA: Stanford Law Books.

- Black, A., & Hoare, P. (2006). Libraries and the modern world. In A. Black & P. Hoare (Eds.), The Cambridge history of libraries in Britain and Ireland (Vol. 3, pp. 7-18). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Braman, S. (2009). Theorizing the state of IT on library-state relations. In G. J. Leckie & J. Buschman (Eds.), Information technology in librarianship: New critical approaches (pp. 105-125). Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

- Burnett, G., & Jaeger, P. T. (2008). Small worlds, lifeworlds, and information: The ramifications of the information behaviour of social groups in public policy and the public sphere. Information Research, 13(2).

- Burnett, G., & Jaeger, P. T. (2011). The theory of information worlds and information behaviour. In A. Spink & J. Heinström (Eds.), New directions in information behaviour (pp. 161-180). Bingley, UK: Emerald.

- Buschman, J. E. (2003). Dismantling the public sphere: Situating and sustaining librarianship in the age of the new public philosophy. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

- Buschman, J. E. (2004). Staying public: The real crisis in librarianship. American Libraries, 35(7), 40-42.

- Buschman, J. E. (2005a). Libraries and the decline of public purposes. Public Library Quarterly, 24(1), 1-12.

- Buschman, J. E. (2005b). On libraries and the public sphere. Library Philosophy & Practice, 7(2), 1-8.

- Buschman, J. E. (2006). "The integrity and obstinacy of intellectual creations: Jürgen Habermas and librarianship’s theoretical literature. Library Quarterly, 76(3), 270-299. doi: 10.1086/511136

- Buschman, J. E. (2007). Democratic theory in library information science: Toward an emendation. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(10), 1483-1496. doi: 10.1002/asi.20634

- Buschman, J. E. (2012). Libraries, classrooms, and the interests of democracy: Marking the limits of neoliberalism. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

- Buschman, J. E. (2013). Libraries and the right to the city: Insights from democratic theory. Urban Library Journal, 13(1), 1-13.

- Cohen, J. L., & Arato, A. (1995). Civil society and political theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Dahlberg, L. (2001). Computer-mediated communication and the public sphere: A critical analysis. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 7(1). doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2001.tb00137.x

- Dahlberg, L. (2004). Net-public sphere research: Beyond the "first phase". The Public, 11(1), 27-44.

- Eley, G. (1992). Nations, publics, and political cultures: Placing Habermas in the nineteenth century. In C. Calhoun (Ed.), Habermas and the public sphere (pp. 289-339). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Emerek, L., & Ørum, A. (1997). The conception of the bourgeois public sphere as a theoretical background for understanding the history of Danish public libraries. In N. W. Lund (Ed.), Nordic Yearbook of Library, Information, and Documentation Research (Vol. 1, pp. 27-57). Oslo, Norway: Novus.

- Evjen, S. (2015). The image of an institution: Politicians and the urban library project. Library & Information Science Research, 37(1), 28-35. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2014.09.004

- Fraser, N. (1990). Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy. Social Text(25/26), 56-80.

- Frohmann, B. (2004). Review of Dismantling the Public Sphere: Situating and Sustaining Librarianship in the Age of the New Public Philosophy by John E. Buschman. Progressive Librarian, 23, 75-86.

- Frota, M. G. d. C. (2014). Biblioteca Pública - espaço de formação da opinião pública? [Public Library - Space of public opinion formation?]. Perspectivas em Ciencia da Informacao, 19(special issue), 79-94. doi: 10.1590/1981-5344/2271

- Furner, J. (2004). Conceptual analysis: A method for understanding information as evidence, and evidence as information. Archival Science, 4(3-4), 233-265. doi: 10.1007/s10502-005-2594-8

- Greenhalgh, L., Landry, C., & Worpole, K. (1993). Borrowed time? The future of public libraries in the UK. Gloucestershire, UK: Comedia.

- Greenhalgh, L., Worpole, K., & Landry, C. (1995). Libraries in a world of cultural change. London, UK: UCL Press.

- Habermas, J. (1962). Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit: Untersuchungen zu einer Kategorie der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft. Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp.

- Habermas, J. (1971). Borgerlig offentlighet : dens framvekst og forfall : henimot en teori om det borgerlige samfunn. Oslo, Norway: Gydendal.

- Habermas, J. (1974). The public sphere: An encyclopedia article (1964). New German Critique(3), 49-55. doi: 10.2307/487737

- Habermas, J. (1984). The theory of communicative action, volume 1: Reason and the rationalization of society (T. McCarthy, Trans.). Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Habermas, J. (1989a). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society (T. Burger & F. Lawrence, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Habermas, J. (1989b). The theory of communicative action, volume 2: Lifeworld and system: A critique of functionalist reason (T. McCarthy, Trans.). Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Habermas, J. (1990). Discourse ethics: Notes on a program of philosophical justification (C. Lenhardt & S. W. Nicholsen, Trans.) Moral consciousness and communicative action (pp. 43-115). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Habermas, J. (1992). Further reflections on the public sphere. In C. Calhoun (Ed.), Habermas and the public sphere. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Habermas, J. (1994). Justification and application: Remarks on discourse ethics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Habermas, J. (1996). Between facts and norms: Contributions to a discourse theory of law and democracy (W. Rehg, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Habermas, J. (2006). Political communication in media society: Does democracy still enjoy an epistemic dimension? The impact of normative theory on empirical research. Communication Theory, 16(4), 411-426. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2006.00280.x

- Ingraham, C. (2015). Libraries and their publics: Rhetorics of the public library. Rhetoric Review, 34(2), 147-163. doi: 10.1080/07350198.2015.1008915

- Jaeger, P. T., & Burnett, G. (2010). Information worlds: Social context, technology, and information behavior in the age of the Internet. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Jaeger, P. T., Gorham, U., Bertot, J. C., Taylor, N. G., Larson, E., Lincoln, R., . . . Wentz, B. (2014). Connecting government, libraries and communities: Information behavior theory and information intermediaries in the design of LibEGov.org. First Monday, 19(11).

- Joeckel, C. B. (1935). The government of the American public library. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Johnson, P. (2006). Habermas: Rescuing the public sphere. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Kramer, L. (1992). Habermas, history, and critical theory. In C. Calhoun (Ed.), Habermas and the public sphere (pp. 236-258). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kranich, N. (2004). Libraries: The information commons of civil society. In D. Schuler & P. Day (Eds.), Shaping the Network Society: The new role of civil society in cyberspace (pp. 279-299). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kranich, N. (2013). Libraries and strong democracy: Moving from an informed to a participatory 21st century citizenry. Indiana Libraries, 32(1), 13-20.

- Leckie, G. J. (2004). Three perspectives on libraries as public space. Feliciter, 50(6), 233-236.

- Leckie, G. J., & Buschman, J. E. (2007). Space, place, and libraries: An introduction. In J. E. Buschman & G. J. Leckie (Eds.), The library as place: History, community, and culture (pp. 3-25). Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

- Leckie, G. J., & Hopkins, J. (2002). The public place of central libraries: Findings from Toronto and Vancouver. Library Quarterly, 72(3), 326-372.

- Lievrouw, L. A. (1994). Information resources and democracy: Understanding the paradox. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 45(6), 350-357.

- Ljødal, H. K. (2005). Folkebiblioteket som offentlig møteplass i en digital tid [The public library as a public meeting place in a digital time] ABM-skrift (Vol. 18). Oslo, Norway: ABM-utvikling.

- Lunt, P., & Livingstone, S. (2013). Media studies’ fascination with the concept of the public sphere: critical reflections and emerging debates. Media, Culture & Society, 35(1), 87-96. doi: 10.1177/0163443712464562

- Machado, E. C., Elias Junior, A. C., & Achilles, D. (2014). A biblioteca pública no espaço público: Estratégias de mobilização cultural e atuação sócio-política do bibliotecário [Public libraries in the public sphere: Librarian's strategies for cultural mobilization and sociopolitical activism]. Perspectivas em Ciencia da Informacao, 19(special issue), 115-127. doi: 10.1590/1981-5344/2263

- McCook, K. d. l. P. (2003). Suppressing the commons: Misconstrued patriotism vs. psychology of liberation. Reference and User Services Quarterly, 43(1), 14-17.

- McCook, K. d. l. P. (2004). Introduction to public librarianship. New York, NY: Neal-Schuman.

- McNally, M. B. (2014/2015). Response to Dr. Samuel E. Trosow's Keynote Address. Progressive Librarian, 43, 30-34.

- Newman, J. (2007). Re-mapping the public. Cultural Studies, 21(6), 887-909. doi: 10.1080/09502380701470916

- Richards, P. S., Wiegand, W. A., & Dalbello, M. (2015). A history of modern librarianship: Constructing the heritage of western cultures. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.

- Rothbauer, P. (2007). Locating the library as place among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer patrons. In J. E. Buschman & G. J. Leckie (Eds.), The library as place: History, community, and culture (pp. 101-115). Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

- Schuhböck, H. P. (1983). Die gesellschaftliche Funktion von Bibliotheken in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Zur neueren Diskussion nach 1945 [The societal function of libraries in the Federal Republic of Germany: The recent discussion since 1945]. Bibliothek: Forschung und Praxis, 7(3), 203-222.

- Schuhböck, H. P. (1994). Bibliothek und Öffentlichkeit im Wandel [Libraries and the public sphere in transition]. Bibliothek Forschung und Praxis, 18(2), 217-229.

- Taipale, K. (2006). From Piazza Navona to Google or, from local public space to global public sphere. Paper presented at the Public Spheres and their Boundaries, University of Tampere, Finland.

- Taipale, K. (2009). Cities for sale: How economic globalization transforms the local public sphere. (PhD), Helsinki University of Technology, Helsinki, Finland.

- Thauer, W., & Vodosek, P. (1978). Geschichte der Öffentlichen Bücherei in Deutschland [History of the public library in Germany]. Wiesbaden, West Germany: Otto Harrassowitz.

- Trosow, S. E. (2014/2015). The commodification of information and the public good: New challenges for a progressive librarianship. Progressive Librarian, 43, 17-29.

- Usherwood, B. (1993). Public library politics: The role of the elected member. London, UK: Library Association Publishing.

- Vårheim, A., Steinmo, S., & Ide, E. (2008). Do libraries matter? Public libraries and the creation of social capital. Journal of Documentation, 64(6), 877-892. doi: 10.1108/00220410810912433

- Ventura, J. J. B. G. (2001). As bibliotecas e a esfera pública [Libraries and the public sphere]. Superior Institute for Labor and Business Sciences, University Institute of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal.

- Ventura, J. J. B. G. (2002). Bibliotecas e esfera pública [Libraries and the public sphere]. Oeiras, Portugal: Celta Editora.

- Vestheim, G. (1997a). Fornuft, kultur og velferd: Ein historisk-sosiologisk studie av norsk folkebibliotekpolitikk [Reason, culture and welfare: A historical-sociological study of Norwegian public library policy]. (Fil.Dr.), Goteborgs Universitet, Sweden.

- Vestheim, G. (1997b). Libraries as agents of the public sphere: Pragmatism contra social responsibility. In N. W. Lund (Ed.), Nordic Yearbook of Library, Information, and Documentation Research (Vol. 1, pp. 115-124). Oslo, Norway: Novus.

- Webster, F. (1995). Theories of the information society. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Widdersheim, M. M. (2015a). Governance, legitimation, commons: A public sphere framework and research agenda for the public library sector. Libri, 65(4), 237-245.

- Widdersheim, M. M. (2015b). System dreams: Public libraries and the politics of regional library service in Allegheny County, 1935-1989. Paper presented at the Pennsylvania Library Association Annual Conference, State College, PA. http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/26293/

- Widdersheim, M. M., & Koizumi, M. (2015a). Conceptual modelling of the public sphere in public libraries. Paper presented at the iConference 2015, Newport Beach, CA. https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/handle/2142/73675

- Widdersheim, M. M., & Koizumi, M. (2015b). Signal architectures of US public libraries: Resolving legitimacy between public and private spheres. Paper presented at the ASIS&T Annual Meeting, St. Louis, MO. https://www.asist.org/files/meetings/am15/proceedings/submissions/papers/50paper.pdf

- Widdersheim, M. M., & Koizumi, M. (forthcoming). Conceptual modelling of the public sphere in public libraries. Journal of Documentation, 72(3). doi: 10.1108/JD-06-2015-0079

- Wiegand, W. A. (2003a). Broadening our perspectives. Library Quarterly, 73(1), v-x. doi: 10.2307/4309616

- Wiegand, W. A. (2003b). To reposition a research agenda: What American Studies can teach the LIS community about the library in the life of the user. Library Quarterly, 73(4), 369-382. doi: 10.2307/4309683

- Wiegand, W. A., & Bertot, J. C. (2003). New directions in LQ's research and editorial philosophy. Library Quarterly, 73(3), i-ix. doi: 10.2307/4309661

- Williamson, M. J. (1998). The public library and social inclusion: Information services to jobseekers. (PhD), University of Brighton, UK.

- Williamson, M. J. (2000). Social exclusion and the public library: A Habermasian insight. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 32(4), 178-186.