Using e-materials for study: students’ perceptions vs. perceptions of academic librarians and teachers

Polona Vilar and Vlasta Zabukovec

Introduction. A qualitative study is presented of student perceptions/preferences regarding academic readings formats, and perceptions on these issues of teaching staff (teachers, assistants) and academic librarians. Topics were scope, ways and goals of use of these materials, handling, competences for searching, active use and evaluation of e-materials, scope of planned teaching of these competences at faculties. Students, teachers and librarians came from the same faculties and disciplines: Translating, Design, Engineering, Psychology, LIS.

Methods. Two methods were used: web survey for students with 25 questions (only the qualitative part – open-ended answers – were analysed), and web interview with 9 questions for teaching staff and librarians.

Analysis. Content analysis was used to identify main topics in both sets of results, and results were compared to look for similarities, differences, etc.

Results. No differences were identified between different disciplines or levels of study, but analysis identified three groups of answers (learning process, organizational aspects, environmental awareness) within three categories: General attitudes and perceptions on e-materials and printed materials; Actions with e-materials and printed materials; Competences of teachers and librarians.

Conclusions. Implications are given regarding teaching process at universities, cooperation between libraries, teachers, and management; and librarians' teachers' competences.

Introduction

Many studies show that deep learning and understanding is better supported with paper materials and that digital materials are more convenient for superficial activities, such as scanning, browsing, quick overviewing of texts (see for example Wästlund, Reinikka, Norlander and Archer, 2005; Mangen, Bente and Kolbjørn, 2013; Chen, Cheng, Chang, Zheng and Huang, 2014; Ackerman and Goldsmith, 2011; Ji, Michaels and Waterman, 2014; Mizrachi, 2010, 2014, 2015). As shown by Ackerman and Goldsmith (2011), Li, Poe, Potter, Quigley and Wilson (2011), and Mizrachi (2015), printed materials are more efficient for comprehension and memorizing, i.e. learning, because with digital materials users perceive tasks as more cognitively demanding, experience frequent concentration problems, have difficulties orienting, remembering and constructing knowledge, as well as marking and annotating text, feel sore eyes, miss the tactile aspect of holding paper (such as flipping pages, paper smell). It has also been found that different types of reading are encuraged with the use of printed and digital texts: receptive reading (i.e. without critical approach and with interruptions of line of thought) is characteristic for digital materials while responsive reading is linked to print (Thayer, Lee, Hwang, Sales, Sen and Dalal, 2011).

There are also studies which found no differences in reading comprehension and retention regardless of the format of material (Noyes and Garland, 2003; Zambarbieri and Carniglia, 2012). Additionally, some authors have even found that younger users, belonging to the so-called Y-Generation (undergradutes, high-schoolers), express greater receptiveness and better learning results (retention and comprehension) with digital materials (Strouse, 2014; Eshet-Alkalai and Geri, 2007).

However, and against many common expectations regarding digital preferences of young generations, many authors show that for students it is still important to have printed materials when engaging in deep learning, while they do value the convenience of digital tools for searching and access. As shown by Dilevko and Gottlieb (2002), printed books are perceived as more reliable and more useful for intensive academic work because they enable better insight and comprehension, also because their length does not enable online reading. With journal papers things are different, as already earlier studies (such as Liew, Foo and Chennupati, 2000 and Sathe, Grady and Giuse, 2002) found preferences of electronic over printed scholarly journals. Some studies (e.g. Tenopir, 2003; Whitmire, 2002) found preference differences between different disciplines: natural sciences seem to be more prone to using digital sources that do Social Sciences or Humanities – although, on the other side, we also find studies which did not identify differences (Gardiner, McMenemy and Chowdhury, 2006; Brady, McCord and Galbraith, 2006).

Therefore it seems that length of texts and study requirements influence the user format preferences or at least impose on them. Case (2005) again confirmed the Zipf Principle of least effort by showing that users like e-materials for their ease of access and use because this enables them to get "things done quickly and easily" (p. 391), especially if texts are shorter and less demanding ("non-academic") – the latter was also confirmed by Foasberg (2014). Corlett-Rivera and Hackman (2014) found that students prefer printed academic books and digital conference proceedings and reference works. Many studies also found that students, and also scholars, use digital tools for searching and gaining access to the materials, do superficial reading on-screen, but print the materials for thorough reading. (Liu, 2006; Tenopir, 2003; Ji, Michaels and Waterman, 2014; Mizrachi, 2010, 2014, 2015; Vilar, Bartol and Juznic, 2015). Language does not seem to be an influential factor, as found for example by Boustany (2015), Kortelainen (2015), Landoy, Repanovici and Gastinger (2015), Terra (2015), Zabukovec and Vilar (2015).

Literature shows that preferences regarding format come under the influence of many factors, among them convenience, mood, urgency, purpose, ecological awareness, length of material, weight, etc. while sometimes they are in fact not genuine preferences; instead they are governed by factors such as availability or price (Mizrachi and Bates, 2013; Mizrachi, 2015).

One of the features of quality learning is active approach which is, among other things, characterized by active work with study materials, such as highlighting, annotating, etc. As found by authors in a large international study (Mizrachi, 2015; Boustany, 2015; Kortelainen, 2015; Landoy, Repanovici and Gastinger, 2015; Terra, 2015; Zabukovec and Vilar, 2015), students were much more inclined to these activities with printed materials while in electronic environment they found them too demanding. Similar conclusions were reached by Quayyum (2008): annotating was perceived as difficult, critical thinking, memorizing and responsive reading were not felt to be supported. Active learning is generally defined as any instructional method that engages students in the learning process. In short, active learning requires students to do meaningful learning activities and think about what they are doing (Prince, 2004). Felder et al. (2000) include active learning in their recommendations for teaching methods that work, as they note among other things. Introducing activity into lectures can significantly improve recall of information while extensive evidence supports the benefits of student engagement (Prince, 2004). Naithani (2008) argues that active learning involves designing, implementing, maintaining and promoting, within and outside classroom, environment for learning, through creating opportunities for active engagement with the subject matter. It strives for higher-order thinking and in-depth comprehension of the learner. Several methods were introduced, such as one-minute paper to find out main idea, concept maps to find relations among concepts, short discussions, writing summaries, simulations etc. One can pick and choose any combination of the methods and tools but the selection of a combination has to be guided by the habits, preferences, willingness, behaviour modification, knowledge base and learning style of the students and also the instructors.

In this study we followed a principal aim of comparing the preferences of the students with how well they are understood by university teachers (also assistants) and academic librarians. We attempted to do this by gaining a deeper insight into the results from the first phase of our study where student format preferences were explored (we did this by analysing their open-ended answers with each question), and to obtain the view from other angles by including faculty (teachers, assistants) and librarians. Our aim was to find out about and to find links between several aspects regarding printed and electronic study materials from all the stakeholders: perceptions, attitudes, actions, required competences, and development of these competences; and to attempt to identify a baseline for the active learning framework. This is relevant in today's turbulent time of higher education reforms and re-conceptualizations of teaching, accompanying the demands for higher student activity and more active and authentic learning situations which would support and encourage deep learning and transferable competences (see for example Golenko, 2015). Our questions were:

- Regarding attitudes, perceptions, preferences:

- What attitudes, perceptions and preferences in general do students express regarding electronic and printed study materials?;:

- Which features of each format affect their attitudes, perceptions and preferences (such as length, language)?;

- How do students feel towards e-textbooks?;

- How are student attitudes, perceptions and preferences understood and addressed by the faculty and librarians from the perspective of active learning?

- Regarding actions:

- Which actions do students employ with e-materials and with printed materials during study and which supporting actions do they employ?;

- How do these actions relate to required competences needed to carry them out?;

- How are these actions and competences understood and addressed by the faculty and librarians from the perspective of active learning?

- How do faculty and librarians perceive their own competences regarding active use of e-materials, and what opinions do they have about the development of these competences?

Method

As mentioned, the study was done in two parts and we worked with two sets of results. The first set comes from the web survey for students done in spring 2015, as part of a larger international study of student format preferences (Mizrachi, 2015; Boustany, 2015; Kortelainen, 2015; Landoy, Repanovici and Gastinger, 2015; Terra, 2015; Zabukovec and Vilar, 2015), from which the methodology and initial results of Likert-scale questions for Slovenia were reported by Zabukovec and Vilar (2015), showing clear and strong preferences of printed materials for deep study, which were also consistent with findings in other countries. In this study we did a qualitative analysis of student answers to open-ended prompts with each question in the 2015 survey with the purpose of additional understanding of the expressed preferences. In February 2016 we did a follow-up study using an open-ended web survey with academic librarians and faculty (teachers and assistants) at the same faculties and disciplines as the students in the survey. These qualitative follow-up activities were aimed at acquiring more information and getting a view from another angle on the student responses, in the light of the principle goal of the study. In this way we worked with data of the same type in both parts of the study.

Student web survey

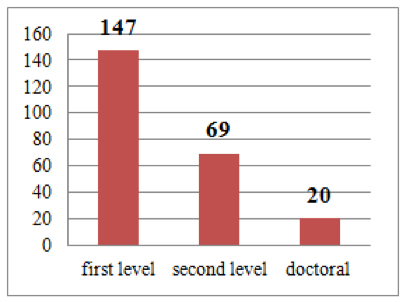

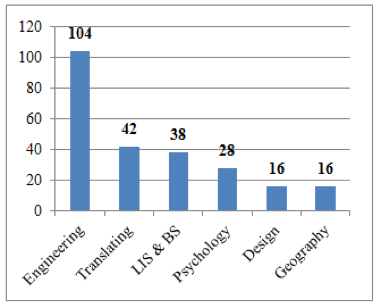

The web survey was opened from 11 March till 13th May 2015. Sample consisted of students of various disciplines and levels from three public universities (University of Ljubljana, University of Primorska, and University of Maribor). The sample was self-selected; students were encouraged to take the survey by the teachers and librarians at respective faculties which we contacted beforehand. There were 140 female and 120 male students; their structure according to study level is shown in Figure 1, according to discipline in Figure 2.

The questionnaire was nearly the same for all participating countries – open-ended comments with each question were only used by some countries, ours included. There were 25 questions: 17 Likert-scale, focusing on various aspects of academic reading formats (reading format preferences, behaviours and attitudes, devices used to read electronic texts, a prompt for open-ended responses or comments), and six demographic questions: gender, age, level of study, discipline, and visual or other limitations.

In the analysis for this study we included: student general attitudes, perceptions and preferences regarding e-materials and printed materials, student activities with e-materials and with printed materials, and related competences. The sample for the study, ie. numbers of students giving open-ended answers is shown in Table 1.

| Discipline | No. |

|---|---|

| Engineering | 36 |

| LIS & BS | 25 |

| Translating | 24 |

| Psychology | 10 |

| Design | 9 |

| Geography | 7 |

| Total | 111 |

Open-ended web survey with faculty and librarians

Sample consisted of 10 respondents: one academic librarian and one university teacher or assistant coming from the same faculties and disciplines as the students; that is from two universities (University of Primorska, University of Ljubljana) and from different disciplines (Translating, Design, Engineering, Psychology, LIS). This sample was rather small, the reason being that we wanted to include participants from the same institutions and disciplines.

Data were gathered in February 2016. There were two similar sets of 9 questions, 7 of them open-ended , differing only slightly to accomodate the aspects of librarians vs. faculty, while still looking at related concepts, regarding their opinions on: (i) student use of e-materials for study purposes, (ii) students' competences for searching, evaluating and active use e-materials, (iii) development of these competences, and (iv) librarians' and teachers' perceptions of their own competences for searching, active use and evaluation of e-materials.

Analysis

Qualitative analysis was applied, more specifically, content analysis, of open-ended answers given by the students and by librarians and university teachers/assistants. Content analysis is a method of finding patterns (connected with behaviour, events, opinions) in textual data (Powell & Connaway, 2004; Krippendorff, 2004).

Content analysis focused on answers which were given by the teachers and librarians and by at least 20% of students within each discipline. We were looking at the topics/categories, corresponding to the research questions, each within the context of active learning:

- Attitudes, perceptions and preferences on e-materials and printed materials, format features(length and language of material), attitudes towards e-textbooks;

- Actions with e-materials and printed materials: a) when used for studying (such as highlighting, making notes); b) for supporting purposes (such as digitizing or printing);

- Answers by faculty and librarians about their own competences as well as the development of these competences.

Results and discussion

We merge and discuss both sets of results (qualitative analysis of student answers regarding printed or electronic study materials, and qualitative analysis of answers of librarians and faculty regarding the use of printed or electronic materials for study purposes), following the three main research questions. We focus on most frequent topics identified in the responses, and illustrate them using direct quotes by respondents (S – student; T – teacher; L – librarian).

The overall findings regarding the first two topics show that no differences could be identified between students of different disciplines or level of study. The analysis of attitudes, perceptions and preferences regarding e-materials and printed materials (section 3.1) showed that the results can be grouped into meaningful units as three distinctive categories of answers were identified: those connected with learning process, those connected with organizational aspects, and those connected with environmental awareness; while certain other interesting opinions are grouped under 'other perceptions'. On the other hand the analysis of actions with e-materials and with printed materials and related competences (section 3.2), again revealed the category of learning process, the second category was supporting processes. Thus we focus most on the learning process category, which is the central theme of this paper. Within each group we intertwine the quotes from student survey with the quotes from the interviews with faculty and librarians, where meaningful relations could be identified. Section 3.3 only includes the answers of faculty and librarians regarding their competences.

Attitudes, perceptions and preferences regarding e-materials and printed materials in the context of active learning

We wanted to investigate students' attitudes toward the format of study materials, features they notice and emphasize; and to see how some of these perceptions are understood and addressed by the faculty and librarians in the context of active learning. The analysis showed, which is aligned with the literature, that students perceive both, positive and negative features of both formats, and that the librarians and faculty are at least partially aware of these perceptions which provides certain opportunities for more active work during teaching.

Learning process

Students (results in Table 2) believe that e-materials are good for searching, translating unknown words, and getting a quick overview while printed materials were perceived as easier to getting a sense of content and scope, good for adding notes, and are most useful for deep studying. They enable better focus, more efficient memorizing, and also allow/encourage reviewing or reuse. They also allow to be divided into smaller, more manageable chunks. These issues can be a starting point for teachers and librarians to find opportunities for active learning while still maintaining the required study level, which can result in higer quality learning, as was found in one teacher's comment. At least some students do posess complex skills for work with e-texts, as they belong to the so-called Y-Generation (Strouse, 2014; Eshet-Alkalai and Geri, 2007). Naithani (2008) has also commented on the importance of developing active study skills through interactive teching and learning methods.

S: 'I prefer e-materials, because searching for certain information is faster, besides, I can immediately transfer it to the dictionary if don't understand the meaning.

T; 'But if it's different type of materials, more interactive (web sources, special websites or applications) the use can be very specific – nothing like linear reading. I think especially in these cases the use of e-materials can be especially effective.'

The negative features of e-materials are linked to difficulties with concentration, lots of distractions, and consequent poor memorizing, sometimes linked to slower reading. Teachers and librarians are aware of this, too, although sometimes puzzled how to balance the need for contemporary teaching with a reasonable quantity of contemporary sources.

S: 'If materials are in e-form, it's much more difficult for me to read with concentration – as consequence I remember less.'

S: 'I have problems with e-reading, it's hard to remember information, also, reading is much slower than from paper.'

T: 'In my experience, reading from screen really encourages superficial reading.'

L: 'Students use teachnology regularly, but it is destructive for concentrated study. But technology can't be avoided, it should ne included more.'

No negative features of printed materials were identified regarding learning process, in fact students only emphasized contrasts with negative sides of e-materials. Already previous analysis (Zabukovec and Vilar, 2015) has shown that Slovenian students prefer printed materials, perceive them as more positive and use them more often than e-materials.

| E-materials | Printed materials | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| - For searching - Translating unknown words - Quick overview |

- Difficulties with concentration - Distractors - Poor memorizing |

- Easier to orientate - Good for adding notes - Better focus - Efficient memorizing - Encourage review or reuse - Division in manageable chunks |

/ |

Although there were not many who said that they prefer e-materials in general, these were seen as better with shorter materials, because students believe that for quick reading or getting an overview (i.e. used as 'informative version') even e-materials allow enough concentration. They also believed that e-materials can be good during active work. Naithani's (2008) findings also conclude that active teaching methods encourage higher-order thinking processes, better attention, memorizing and retention; as a consequence knowledge becomes more useful (Quayyum, 2008). Here again, some teachers were found to understand and accomodate student perceptions to some extent in order to make their teaching more dynamic.

S: 'For study it's more convenent if it's printed, for (quick) searching in the literature e-form is more convenient.'

S: 'For active work, like seminars, research papers etc. computer is of course handy.'

T: 'If work in the classroom is interactive and materials are appropriate, electronic can be better than printed.'

Some students linked their positive attitude towards shorter e-materials with the structure of materials, meaning that they didn't mind e-materials if there were a lot of graphical features, pictures, etc. Longer materials, especially if containing mostly text, were undoubtedly preferred on paper.Therefore we could assume that length of text was an influential factor in preferences of e-materials, as was also found by Case (2005), Mizrachi (2015) and Foasberg (2014). It would therefore be advisable to use teaching methods which develop skills for using e-texts in the sense of structure building. If students are guided and encouraged in this process, if they have a good model to follow (the teacher or librarian), then these skills are more likely to be developed and used. Sensible are Naithani's (2008) suggestions to use methods of deep reading, finding keywords, building concept networks, etc.

As regards e-textbooks, students perceive them as good in terms of all positive features of e-materials already mentioned (good for searching, for superficial study); among negative features they emphasized less clear structure of these materials, and the need to print certain sections for deep study. This is similar to the finding of Dilevko and Gottlieb (2002) that students like to choose printed books due to their reliability. It was interesting to find that quite a few make hand-written notes while using e-textbooks. E-textbooks were popular due to being very modern, cheaper, accessible especially if open for print, while some students said that they use them only if there is no print version, and stressed the negative side, ie. poorer offer, as there are not many around. Faculty or librarians did not comment on e-textbooks which was somewhat surprising to us.

S: 'I borrow e-books for study, but I mostly only go through the table of contents – I don't study from them. If I need some chapter, I print it.'

Regarding language, about half of students said that they prefer foreign materials in e-format because it makes it easier to search for unknown words and translate them. Some said it's not the language itself that influences their format preferences but the complexity of materials.

S: 'I only use e-reading with English materials, because I can translate unknown words as I go along.'

Although the teachers and librarians believe that e-materials are more often used by more senior students, statements by more senior students did not differ from more junior students.

T: Use of e-materials depends on the type of the course and on the level of students.

L: 'I believe there is big difference regarding frequency and goal of use of e-materials in terms of study level – the senior the students the more frequently they use e-materials.'

Very few students directly spoke about who gives the initiative to use the materials, but from the answers we can conclude that more active teaching would be welcomed by the students. They believe that this would enable them more meaningful learning and greater awareness of the learning process which they would also be able to self-direct. When looking at answers of librarians and faculty, we see some differences between their opinions. Librarians believe that electronic academic materials are not used for study on students' own iniciative; teachers' instruction or even demand is needed. But on the other side, teachers believe that students do use electronic academic readings on their own initiative when interactive teaching methods are applied and teaching is organized in small study groups, although they, too, think that the use is more rare when it depends on self-initiative of students. Similar was found by Naithani (2008) and Felder, Woods, Stice and Rugarcia (2000). Librarians also believe that e-materials are not used so much also because the teachers request students to read paper materials; and that the use of e-materials would increase if the teachers also used these materials themselves.

S: 'I support professors who make the effort of making e-scripts from their lectures.'

S: 'It's very handy if the notes have been made by the professor, or assistants and contain the core of necessary knowledge. Then students can bring them to the lecture and add additional explanation if needed for better understanding.'

T: 'I think student's own initiative in the use of e-materials is more rare than if it's required. Self initiative is more present with courses that are more interesting to students and more interactive.'

L: 'I believe that students on their own initiative very rarely use e-materials for study purposes. Students use e-materials much more frequently when this is demanded or instructed by the teachers than on their own initiative.'

L: 'I believe that the use of e-materials would increase if they were regularly used by the teachers.'

L: 'Teachers who themselves use e-materials a lot, and also alert the students, are more succesful.'

Coupled with student opinions, we see an opportunity for the teaching to become more active, and result in deeper and more permanent knowledge, if teachers and librarians develop their own competences and embrace the positive student attitude as well as their apparent willingness to follow their instructions and to learn, which is consistent with the findings and recommendations of Naithani (2008), Felder, Woods, Stice and Rugarcia (2000), and Prince (2004), and beautifully illistrated with the following quote where it's apparent that for some students the shift in teaching is a matter of time and that electronic materials will bring along some new skills:

S: 'I fight for the right to e-read! I believe that students will get used to e-reading more and more. It will probably change the way of learning and thinking but I don't see this as bad. I think it's normal, evolutional. In a few decades there will be a need for different literacies as we have now. The book will stay, in different forms. Study will also stay, in different forms.'

Organizational aspects

In terms of organization (Table 3), students saw e-materials as better for accessing, searching and finding, saving, formatting, and sharing with colleagues. These are the features of active learning, which are obviously already used, and could be systematically supported and developed further by the teachers and librarians to achieve more active work in the classroom. Printed materials were seen as good because they do not contain distractions, don't cause addiction to devices, are more handy to carry around, read in bed, look again or overview. Concentration was also found to be an important factor by Ackerman and Goldsmith (2011), Li, Poe, Potter, Quigley and Wilson (2011), and Mizrachi (2015). It is obvious that deep learning is still only possible from paper. Some teachers brought to attention the specificity of digitized printed materials which are, in their opinion, used a lot like printed ones.

S: 'If materials are in printed form, I can also look in them after a year or so.'

S: ' I prefer to design, format and edit study materials in digital form. I prefer to read articles and books in e-format, but I prefer to study from printed format because it is easier to focus.'

T: 'If it's only e-form of a printed source (like PDF) I think it depends on the personal preference.'

On the other side, students linked negative features of e-materials to problems with technology, while printed materials were seen as less practical to carry around due to weight, consuming more space, and being less practical for reference at some later time. Librarians warned that often the choice of format is due to teachers' demands, not voluntary.

S: 'Imagine how heavy our bags would be, if we had to bring everything to the lecture.'

S: 'Printed materials are easier to read and study from, but, when I pass the exam, printed materials go to the 'physical archive' - pile of old literature. Once there I probably won't have another look at it because it's too hard to find in a pile over meter high. For later reference e-materials have great advantage, that it's easier to find and search.'

L: 'Students don't use e-materials much. The reason is that most study literature is printed and teachers also recommend/require it. E-materials are used, if demanded.'

| E-materials | Printed materials | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative |

|

Accessing Searching Finding Saving Sharing Formatting |

Difficulties with technology Difficulties with highlighting |

No distractions Do not cause addiction More handy to carry Look again and overview Cheaper More long-term |

Less practical Heavy Consumes more space Not good for later reference |

Environmental awareness

This category was identified with students' positive opinions on e-materials and negative opinions on printed materials. E-materials are perceived as eco-friendly, printed materials waste paper, ink, are expensive, and are also often discarded when no longer needed. Only a few had opposing thoughts.

S: Printed materials are much more environment friendly. Paper is recyclable material.

We did not identify such opinions with university teachers and assistants or librarians which is consistent with findings of Mizrachi and Bates (2013) and Mizrachi (2015).

Other perceptions

Students find printed materials problematic due to their price/availability: buying them is often very expensive; often there are not enough copies in the libraries. But also e-materials were seen as problematic by some students, because of their limited availability (students emphasized that not enough study materials are in e-format, they can be obtained only from faculty, via remote access or in e-learning, i.e. through passwords).

S: The choice of buying a laptop or smartphone depends on the money – if there is none, priorities are not on reading study literature in e-form.

S: I would like it if more materials were (also) in digital form, so that you don't waste time visiting libraries and waiting for materials when they are on loan.

S: If students could access e-materials through an application (with high level of protecting author and user information) and all materials would be available 24/7, study would be mnuch easier. Especially if all printed materials would be digitized on the long run. This way students could access quality information with speed comparable to internet searching.

Technological aspects of electronic format also appeared; for some it was relevant in terms of the type of material.

S: If I get a virus, I need to restore the system and I lose all e-articles that I have on it. I don't trust cloud-computers.

S: Electronic should be adaptable to the screen

S: Certain things can be electronic – like videos, films.

Teachers and librarians did not emphasize availability of materials, possibly because they do not feel this problem to the same extent and consequently do not see it as equally problematic. However, librarians also believe that the use of e-materials is increasing with the use of e-learning, which we could confirm, as students, too, spoke about having materials available through e-learning, although occasionally complaining about too many channels.

S: 'I like e-materials in e-learning because I can print them or have them on computer and bring them to the lecture.'

S: 'I rather buy study literature in the form of textbook than to have to go over e-classrooms, student information system and various dropboxes to find out which e-materials need to be printed (and then pay for copies of each sheet of e-materials separately).'

Some student perceptions pointed towards personal preferences affinity towards (mostly printed) format while some revealed deeper insights:

S: 'It's easier to take the book to bed than a laptop.'

S: 'I also like the feeling of physical materials in my hand.'

S: 'With books there remains peace which doesn't exist with electronic devices. They return us to silence, don't scream, disturbe, become colleagues and comlanions in conversation, we share touches and words.'

S: 'It's not important if electronic or in print, it's important to have the will/motivation to read (if and when I have it).'

Actions with e-materials and with printed materials, and related competences in the context of active learning

This question addressed both, actions and also competences needed to carry out the actions with e-materials in the context of active learning. Besides identifying the activities, we were also interested in the competences which students believe to possess and which they believe to be underdeveloped regarding e-materials; and how these competences are understood and addressed by the faculty and librarians. We identified opinions related to learning process, and other general opinions.

Learning process

The students mostly said that they use the techniques of highlighting and making notes on/with printed materials while only rare do the same with e-materials. All these activities are features of active learning, therefore it should be possible to think of ways of transferring them also to the use of e-materials. Especially as many students were found to make notes on paper while studying from e-materials (while virtually none was found to make e-notes with printed materials) – which is interesting in itself, as students obviously have intuitively transferred some ways of active use onto a new format, although in a rather awkward way. Active learning techniques besides higher-order cognitive processes, better memorizing, retention and concentration also enable more succesful and long-lasting transfer of knowledge, thus making learning much more effective (Naithani, 2008; Felder, Woods, Stice and Rugarcia, 2000). The study should not be only receptive reading but responcive and critical which offers the possibility of linking existing knowledge and active use of new knowledge. Receptive reading (i.e. without critical approach and with interruptions of line of thought) is characteristic for digital materials while responsive reading is linked to print (Thayer, Lee, Hwang, Sales, Sen and Dalal, 2011). We again see this as an opportunity for teaching, even more so, as highlighting e-materials (Table 4) was seen as difficult, time-consuming, unpractical and useless for getting orientation – therefore perceived negatively by the students, which could be changed with appropriate teaching approaches. Quite a few students also emphasized that they do not have enough knowledge and skills to do it (Table 4), do not use active study techniques with e-materials because they don't know how, aren't used to them (or are only slowly getting used to them), that they would use them, if they felt more confident. Development of these skills should be done through interactive forms of teaching and learning (Naithani, 2008).

S: "If I want to highlight for better understanding, paper is better."

S: "I only slowly catch up with these technologies/applications."

S: "Electronic functions don't work well and I spend too much time to "colour" something."

S: "Nobody has ever taught us to use these highlight features in e-materials, so I never use them."

| Reasons for not highlighting e-materials |

|---|

|

- Difficult - Time-consuming - Unpractical - Useless for getting orientation in text - Not enough knowledge and skills |

Highlighting paper materials and making hand-written notes, sketching, drawing, etc. was mentioned by several as part of active study contributing to better understanding, more efficient learning; some stressed that they do it if time permits. This is consistent with findings of many studies, among them Mizrachi (2015), Boustany (2015), Kortelainen (2015), Landoy, Repanovici and Gastinger (2015), Terra (2015), Zabukovec and Vilar (2015), Quayyum (2008) and also promising in the light of finding ways to transfer these competences to electronic environment.

Both librarians and university teachers/assistants believe that since electronic materials are predominantelly used for quick reading from the screen, students do not use underlining or notes in e-materials. They also believe that students sometimes print electronic materials and use study techniques to support intensive study of materials, as was also found by Case (2005), Mizrachi (2015) and Foasberg (2014). With this they partly confirmed what was said by the students; although students in fact do not highlight e-materials, they do perform the same activity of making notes as with printed materials. It is likely that teachers themselves do not use these techniques a lot with e-materials and, as a consequence, do not support students either. On the other hand, some librarians did show insight into student activities.

L: 'I think they write down notes as they study from e-materials and that they print a lot.'

Librarians and teachers share the opinion that with the level of study, intensity and frequency of use of electronic academic materials increase, but we already showed that the student results did not show these differences. However, librarians and teachers also believe that there are no differences between different levels of study in using study techniques, such as underlining, highlighting and making notes or comments, and this was confirmed in the student survey.

Librarians and teachers also believe that students are not competent enough for retrieving, evaluating and active use of electronic materials. Within this context some answers from librarians mentioned generational differences.

T: 'They are equally (in)competent for all three.'

L: 'I think that with generations they are becoming more and more competent.'

Both are also convinced that these comptences should be systematically developed and upgraded, as is also recommended by the Framework for information literacy for higher education (Association of College and Research Libraries, 2016) where these competences are considered an integral part of information literacy. Mizrachi (2015) also supported the teaching collaboration between the faculty and librarians.

When asked whether they support and develop these competences with students, only half of librarians answered positively. We can assume that there are some educational programs in university libraries for developing students' competences for retrieving, evaluating and active use of electronic materials, but are not implemented systematically. Librarians mentioned that the reasons for not working with students on a regular and planned basis mostly lie in the unpreparedness of faculty management to allocate adequate resources. On the other hand, all teachers answered positively to the same question. We interpret this as an opportunity that librarians can embrace in order to establish teaching cooperation. Information skills, from reflexive information discovery, understanding how information is generated and evaluated, and the use of information in creation of new knowledge and erhical participation in learning communities, should be taught to form an integrated whole – the information literacy, as defined by Association of College and Research Libraries (2016). Information literacy is not a technical skill, but a cognitive one, as it requires critical thinking about the information found in various sources and sensible use of this information (Decarie, 2012), and enables the students to succesfully use the study materials. Where competences for searching, evaluation and active use are taught, librarians place most emphasis on search and use competences. Some librarians are aware that some competences receive more attention than others. Teachers stress more demanding cognitive skills, such as content analysis, interpretation, paraphrasing, abstracting. According to teachers, skills for evaluating electronic materials should be taught more often and with greater care.

L: We focused on search and use, we should focus more on evaluation of e-materials.

T: ability for good analysis of content, summarizing, more planned introducing of competency model in this field would be welcome.

T: Above all they should know searching for credible sources – this area needs thorough and planned development.

Both believe that the cooperation between librarians and teachers in developing student competences for e-materials should be more intensive and should be better supported. But, both also spoke about obstacles, and mainly saw the other side as the main reason why cooperation is not better. Librarians mostly believe that teachers do not show interest for such cooperation, which, as we saw above, apparently is not true. Some librarians stressed that it is also their task to establish and encourage cooperation with teachers, and suggested that it could be started through education which libraries would offer to the teachers. On the other side, the impressions of teachers are that cooperation is not as intensive as it could be. It is also not perceived as useful by some teachers although some said that they could not assess how it would work because cooperation has not yet happened. Some teachers believe that librarians' work is very specific, unrelated to teaching, and also that librarians often do not want to cooperate with teachers. Librarians also think that they usually possess good knowledge although some also stressed that this knowledge needs improving.

T: ‘There's not enough working together between librarians and us. Sometimes we get the feeling that library work is "off limits", that we, teachers, should not interfere with it.’

L: ‘Some teachers are willing to work together, but librarians should be more competent for teaching these competences. We can't get them ourselves, we should have trainings for good teaching inside pedagogical process.’

L: ‘It's us who should approach the teachers about joint teaching.’

Actions supporting learning process

Printing e-materials is done more often than digitizing paper materials. However, students stressed that printing is mostly done selectively, with best or most needed materials while librarians think they print more. The most frequent reason for printing is getting a paper copy to write on/highlight/learn from.

S: 'It was most conveient when we got printer-friendly digital versions.'

S: 'Compared to the beginning of study I can say that I print less and less. Personally I noticed this transition from printed forms to electronic.'

T: 'I think at least some students also print such materials.'

L: 'I think they print most materials.'

Factors preventing printing are either linked to price or ecology. This is consistent with librarians' and teachers' beliefs that students only occasionally print their e-readings. Digitizing is generally seen by students as a waste of time. If students do it, the reasons are also linked to importance of material: archiving/saving and sharing.

S: 'Once you have a physical copy, there really is no reason to digitize it (except for archiving for posterity).'

Faculty and librarians' competences regarding e-materials

This section only concerns answers of librarians and university teachers/assistants. Both believe that they need additional training, especially for evaluating and active use of electronic materials. The competences for searching were perceived as least problematic (only one librarian and one teacher thought their skills could be further developed). We believe that it is especially important that teachers possess the competences for evaluating and active use of electronic materials as they will be able to use them in class and will also serve as a good role model for the students. This should result in better information literacy of all. Some teachers expressed both self-confidence and preparedness to learn.

T: I belive I have quite a lot of knowledge in this area, but it can always be improved, especially due to such quick developments.

When asked about education and training, which could be offered to the teachers, both agreed that librarians are the ones to do it. One teacher even said that internal education, done by the 'home' librarians, would work best because they already know each other, librarians are more approachable. Librarians also said that this would mean additional work tasks for them.

T: probably internal librarians would be the best for this job, since we know them and they are more close to us.

L: We could do it but we would need more knowledge. Also, we would need to think how to find the time.

The suggested forms and methods for such training were also aligned on both sides: e-learning, videolectures, short specialized trainings, all due to teachers being busy and not having a lot of time. It is therefore reasonable to assume that such education would be welcomed by both sides, although we need to take into accout the obstacles mentioned by the librarians and related to working conditions of academic libraries.

Conclusions

Our sample does not allow generalizing, however, the results are still consistent throughout different disciplines and levels of study. For deep learning students still prefer printed materials, but at the same time acknowledge and use the advantages of electronic. For example, e-textbooks are perceived positively within the usual limits of e-materials (good for searching and superficial reading, but having less clear structure and often need to be printed for more thorough study). Based on this perception it could be concluded that e-materials are not convenient for taking notes and they do not give opportunities to students to be actively engaged in study materials. Consequently the recall of information is difficult (Prince, 2004). Teachers and librarians are aware of these preferences. Answers of both groups indicate that students would have to be trained for more active use of e-materials. Naithani (2008) suggested several methods or techniques with the aim to improve comprehension and higher-order thinking, such as to find out the main idea, concept maps, simulations etc. The decision regarding their application should be related to the content. It was interesting to find that some students expect certain changes in the educational process which would be caused by the electronic materials (development of specific skills, literacies, etc.). It was also stressed that e-materials are often used with their final works, which again makes the competences necessary. Students also often brought up the environmental aspect of e-materials which was not mentioned by either the teachers or librarians.

We identified areas where students' and teachers/ librarians' perceptions differ to a certain extent. For example, students answers did not reveal differences between levels of study while teachers and librarians seem to think that more senior students are more familiar and competent with e-materials. Librarians were convinced that students use e-materials only when requested by the teachers. Students, and also teachers, did not confirm this, and a certain level of independence was noticed. It was, however, apparent that students would like to have more materials available in electronic format. But we all should be aware that this could lead to lower level of comprehension (Naithani, 2008).

On the basis of gathered opinions we can start to think what could be done on a short run, and on a long run regarding a) teaching process at universities, which is also strongly connected with establishing cooperation between libraries, teachers, and management; and b) work on librarians' and teachers' own competences.

In terms of teaching our research gives some starting points regarding active teaching and learning. Teachers could direct their efforts towards higher cognitive strategies (such as interpreting, paraphrasing, abstracting, creating) while at the same time including librarians in the areas of searching, getting acquainted and using e-materials, finding examples of good e-materials, etc. There is no doubt that more active, and, above all, more systematic introducing of information skills can intensely enrich academic teaching and result in deeper knowledge (Prince, 2004; Naithani, 2008). At present, e-materials are not perceived as useful for deep learning, therefore students need to be given the tolls which would change this (this probably also concerns the competences of teachers and librarians). Here collaboration among the stakeholders can bring good results (see for example Golenko, 2015; Golenko, Vilar and Stricevic 2012); the prerequisite being institutional support (Golenko, 2015; Golenko, Vilar and Stricevic, 2013). Some standpoints need further investigation if we want to change them: the teachers belief that librarians are not interested in collaboration, as well as librarians' questioning whether teaching is among their tasks. The third is the support of the management which, according to some statements is lacking.

Although the teachers and librarians did not perceive their competences as very problematic (especially competences for searching), it is very important, especially for teachers, to acquire and develop competences for evaluating and active use of electronic materials which will enable them to use them in their teaching. It is good that we found a consensus that librarians should be responsible for education of teachers; they also agree on the forms of such teaching.

Our findings can serve as a foundation for further investigations of these phenomena and issues in order to make the academic teaching/learning process as active as possible. We believe that such approach can bring many improvements to academic teaching at the same time influencing the roles and status of academic librarians and the quality of acquired knowledge by the students.

About the authors

Polona Vilar is Associate Professor at the Department of LIS&BS, University of Ljubljana. She teaches and researches in the areas of information behaviour and information literacy, school and public libraries. She can be coontacted at polona.vilar@ff.uni-lj.si.

Vlasta Zabukovec is Professor at the Department of LIS&BS, University of Ljubljana. Her teaching and research interests are psychology, information literacy, and school libraries. She can be contacted at vlasta.zabukovec@ff.uni-lj.si.

References

- Ackerman, R. & Goldsmith, M. (2011). Metacognitive regulation of text learning: on screen versus on paper. Journal of Experimental Psychology Applied, 17(1), 18-32.

- Association of College and Research Libraries. (2016). Framework for information literacy for higher education. Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6mP7fJGaN).

- Boustany, J. (2015). Print vs. Electronic: What Do French Students Prefer in Their Academic Reading Material? In S. Špiranec (Ed.). European conference on information literacy (ECIL) : October 19-22, 2015, Tallinn, Estonia : abstracts (pp. 17). Tallinn: Tallinn University.

- Brady, E. E., McCord. S. K. & Galbraith, B. (2006). Print versus electronic journal use in three Sci/Tech disciplines: the cultural shift in process. College & Research Libraries, 67, 354-363.

- Case, D.O. (2005). Principle of least effort. In: K.E. Fisher, S. Erdelez, L. McKechnie (Eds.). Theories of Information Behavior (pp. 289–297). Medford, NJ: Information Today.

- Chen, G., Cheng, W., Chang, T., Zheng, X. & Huang, R. (2014). A comparison of reading comprehension across aaper, computer screens, and tablets: does tablet familiarity matter? Journal of Computers and Education, 1(2–3), 213-225.

- Corlett-Rivera, K. & Hackman, T. (2014). E-Book usage and attitudes in the humanities, social sciences, and education. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 14(2), 255-286.

- Decarie, C. (2012). Dead or Alive: Information Literacy and Dead (?) Celebrities. Business Communication Quarterly, 75 (2), 166-172.

- Dilevko, J. & Gottlieb, L. (2002). Print sources in an electronic age: a vital part of the research process for undergraduate students. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 28(6), 381-392.

- Eshet-Alkalai, Y. & Geri, N. (2007). Does the medium affect the message? the influence of text representation format on critical thinking. Human Systems Management, 26(4), 269-279.

- Felder, R., Woods, D. Stice, J. & Rugarcia, J. (2000). The Future of Engineering Education: II.Teaching Methods that Work. Chemical Engineering Education, 34(1), 26-39.

- Foasberg, N. (2014). Student reading practices in print and electronic media. College and Research Libraries, 75(5), 705-723.

- Gardiner, D., McMenemy, D. & Chowdhury, G. (2006). A snapshot of information use patterns of academics in British universities. Online Information Review, 30(4), 341-359

- Golenko, D. (2015). Model intrakurikularnog pristupa informacijskoj pismenosti na visokošolskoj razini u području prava : doktorski rad. [Model of intracurricular approach to information literacy on higher education level in the area of Law: doctoral thesis]. Zadar: University of Zadar (Ph.D. dissertation [in Croatian]).

- Golenko, D., Vilar P. & Stricevic I. (2012). Information literacy skills of law students: challenges for academic librarians. In T. Todorova, D. Stojkova (Eds.). Informacioannata gramotnost – modeli za obučenie i dobri praktiki = Information literacy – training models and best practices: sbornik c naučni dokladi i s'obščenija od Naučen seminar s meždunarodno učastie, 18-19 oktomvri 2012 g, (pp. 36-54). Univerzitetska biblioteka na ikonomičeskaja univerzitet, gr. Varna, Sofija: Izdatelstvo Za bukvite – O pismeneh'.

- Golenko, D., Vilar P. & Stricevic I. (2013). Academic strategic documents as a framework for good information literacy programs. In S. Kurbanoglu et al. (Eds.), Worldwide commonalities and challenges in information literacy: European conference in information literacy, ECIL 2013 Istanbul, Turkey, October 22-25, 2013: revised selected papers (pp. 415-421). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Ji, S.W., Michaels, S. & Waterman, D. (2014). Print vs. electronic readings in college courses: cost-efficiency and perceived learning. Internet and Higher Education, 21, 17-24.

- Kortelainen, T. (2015). Reading Format Preferences of Finnish University Students. In S. Špiranec, S. Virkus, S. Kurbanoglu, E. Grassian, D. Mizrachi & L. Roy (Eds.), Information literacy : moving toward sustainability : third European conference, ECIL 2015, Tallinn, Estonia, October 19-22, 2015 : revised selected papers (pp. 446-454). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology.Thousand Oaks, CA : Sage.

- Landøy, A., Repanovici, A. & Gastinger, A. (2015). The More they Tried it the Less they Liked it: Norwegian and Romanian Student’s Response to Electronic Course Material. In S. Spiranec, S. Virkus, S. Kurbanoglu, E. Grassian, D. Mizrachi & L. Roy (Eds.). Information literacy : moving toward sustainability : third European conference, ECIL 2015, Tallinn, Estonia, October 19-22, 2015 : revised selected papers (pp. 455-463). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Li, C., Poe, F., Potter, M., Quigley, B. & Wilson, J. (2011). UC Libraries Academic e-Book Usage Survey. Retrieved from http://www.cdlib.org/services/uxdesign/docs/2011/academic_ebook_usage_survey.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6iHq1R7VR)

- Liew, C.L., Foo, S. & Chennupati, K.R. (2000). A study of graduate student end-users; use and perception of electronic journals. Online Information Review, 24(4), 302-315.

- Liu, Z. (2006). Print vs. electronic resources: a study of user perceptions, preferences, and use. Information Processing and Management, 42(2), 583-592.

- Mangen, A., Bente, R.W. & Kolbjørn, B. (2013). Reading linear texts on paper versus computer screen: effects on reading comprehension. International Journal of Education Research, 58, 61-68.

- Mizrachi, D. &, Bates, M.J. (2013). Undergraduates’ personal academic information management and the consideration of time and task-urgency. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(8), 1590-1607.

- Mizrachi, D. (2010). Undergraduates’ academic information and library behaviors: preliminary results. Reference Services Review, 38(4), 571-580.

- Mizrachi, D. (2014). Online or print: which do students prefer? In Serap Kurbanoğlu, Sonja Špiranec, Esther Grassian, Diane Mizrachi, Ralph Catts, (Eds.), ECIL 2014 (pp. 733-742). Heidelberg, Springer.

- Mizrachi, D. (2015). Undergraduates' Academic Reading Format Preferences and Behaviors. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(3), 301-311.

- Naithani, P. (2008). Reference framework for active learning in higher education. In A. Y. Al-Hawaj, W. E. Ahlia, E.H. Twizell (Eds.). Higher Education in the Twenty-First Century: Issues and Challenges (pp. 113-120). London: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Noyes, J.M. & Garland, K.J. (2003). VDT versus paper-based text: reply to Mayes, Sims and Koonce. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 31(6), 411-423.

- Powell, R. R., & Connaway, L. (2004). Basic research methods for librarians (4th ed.). Littleton, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

- Prince, M. (2004). Does active learnign work? A Review of the Research. Journal of Engineering Education, 93(3), 223-231.

- Quayyum, M.A. (2008). Capturing the online academic reading process. Information Processing and Management, 44(2), 581-595.

- Sathe, N.A., Grady, J.L. & Giuse, N.B. (2002). Print versus electronic journals: a preliminary investigation into the effect of journal format on research processes. Journal of Medical Libraries Association, 90(2), 235-243.

- Strouse, R. (2014). The changing face of content users and the impact on information providers. Online, 28(5), 27-31.

- Tenopir, C. (2003). Use and Users of Electronic Library Resources: An Overview and Analysis of Recent Research Studies. Retrieved from http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub120/pub120.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6iHqBXw80)

- Terra, A.L. (2015). Students’ Reading Behavior: Digital vs. Print Preferences in Portuguese Context In S. Spiranec, S. Virkus, S. Kurbanoglu, E. Grassian, D. Mizrachi & L. Roy (Eds.). Information literacy : moving toward sustainability : third European conference, ECIL 2015, Tallinn, Estonia, October 19-22, 2015 : revised selected papers (pp.436-445). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Thayer, D., Lee, C.P., Hwang, L.H., Sales, H., Sen,P. & Dalal, N. (2011). The Imposition and Superimposition of Digital Reading Technology: The Academic Potential of E-readers. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 2917-2926). Vancouver, BC: Association for Computing Machinery.

- Vilar, P., Juznic, P. & Bartol, T. (2015). Information behaviour of Slovenian researchers: investigation of activities, preferences and characteristics. Information Research, 20(2). Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/20-2/paper670.html.

- Wästlund, E., Reinikka, H., Norlander, T. & Archer, T. (2005). Effects of VDT and paper presentation on consumption and production of information: psychological and physiological factors. Computers and Human Behavior, 21(2), 377-394.

- Whitmire, E. (2002). Disciplinary differences and undergradiates' information seekign behavior. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 53(8), 631-638.

- Zabukovec, V. & Vilar, P. (2015). Paper or Electronic: Preferences of Slovenian Students. In S. Spiranec, S.Virkus, S. Kurbanoglu, E. Grassian, D. Mizrachi & L. Roy (Eds.). Information literacy : moving toward sustainability : third European conference, ECIL 2015, Tallinn, Estonia, October 19-22, 2015 : revised selected papers (pp. 427-435). Cham, Switzerland : Springer.

- Zambarbieri, D. & Carniglia, E. (2012). Eye movement analysis of reading from computer displays, ereaders and printed books. Ophthalmic & physiological optics, 32(5), 390-396.