Managing information in law firms: changes and challenges

Nina Evans and James Price

Introduction. Data, information and knowledge together constitute a vital business asset for every organization that enables every business activity, every business process and every business decision. The global legal industry is facing unprecedented change, which inevitably creates challenges for individual law firms. These global changes affect law firms' business as well as information environments.

Method. Qualitative interview-based empirical research was conducted with partners and practice managers in law firms in Australia, South Africa and the United States of America, to investigate the changes in the legal industry, the challenges subsequently faced by law firms, and how these challenges are being addressed.

Analysis. The interview transcripts were thematically analysed, supported by the NVivo10 qualitative analysis software.

Results. The legal sector, one of the most data, information and knowledge intensive industries, is currently undergoing unprecedented change resulting in numerous challenges for law firms that are creating increased pressure to be more effective and efficient.

Conclusion. The findings show that significant improvement to law firms' business performance can be driven by overcoming barriers to information asset management such as lack of executive awareness, justification, business governance, leadership and management, as well as ineffective tools. This paper recommends the steps that law firms can take to overcome these barriers.

Introduction

The global legal industry is facing unprecedented change, which inevitably creates challenges for individual law firms. These global changes affect law firms' business and information environments. The four resources (or assets) available to any organization, including law firms, are: financial assets (money); physical assets (land, plant, equipment, hardware and software); human assets (people) and information assets (data, information and knowledge). Data, information and knowledge together constitute a vital business asset for every organization, including law firms, that enables every business activity, every business process and every business decision. Information assets are the lifeblood of an organization and 'modern day gold' (McFadzean, Ezingeard and Birchall, 2007).

In this paper our working definition of the term information assets include all explicit, codified data and all unstructured information in records, documents and published content, as well as knowledge in peoples' heads (Evans and Price, 2012). The term information asset management refers to the processes and procedures to deploy information assets to derive meaningful business insights and deliver those insights to consumers at the right time in the right format (Bhatt and Thirunavukkarasu, 2010).

Law firms specialise in the speedy and efficient creation and transfer of legal information assets (Khandelwal and Gottschalk, 2003). Law firms face increased competition and pressure to be more productive and efficient. The productivity, competitiveness and success of a law firm is predominantly determined by how well it deploys its human assets and the information assets upon which they rely to deliver their advice. Information asset management ensures that enterprise data, information, content and knowledge are treated as assets in the true sense of the word, and avoids increased risk and cost due to misuse of information assets, poor handling or exposure to regulatory scrutiny (Ladley, 2010). Evans and Price (2012) agree that the effective management of information gives an enterprise a competitive edge, while information mismanagement leads to decline. Effective information asset management will allow a law firm to produce certain documents more efficiently, increase productivity and reduce stress (Kabene, King and Skaini, 2006).

This paper focuses on the management of information assets in law firms as regards accountability, governance, leadership and the behaviour of legal practitioners. The research questions for this study are:

- How can law firms manage their information assets to mitigate risk, manage costs and derive benefits from these assets and thus drive increased competitive advantage?

- What challenges do law firms experience in managing their information assets?

We present the findings of empirical research on three continents, focusing on the changes in the legal industry, the resulting challenges to law firms and their responses. Some of these responses are structural, appropriate and effective. However, the changes also demand that law firms become more efficient and effective, which means that the allocation of their fundamental resources must be improved, particularly the improvement of information asset management. The theoretical background, research methodology and research questions are followed by the qualitative empirical findings. The final sections of the paper contain the conclusions, recommendations, limitations and suggestions for future research.

Theoretical background

Information asset management

Law firms specialise in the creation and transfer of legal information assets that include knowledge about the plaintiff, defendant, client and judge, and about lawyers' experience, expertise and professional judgement (Sukumaran, Chandra and Chandra, 2013); knowledge of prior cases and how to ensure the best outcome for their client (Frost, 2013); and precedent agreements, checklists, research memos, opinion letters, guidelines, business plans, client lists, meeting minutes and matter summaries (Crosby, 2012).

Information assets can significantly enhance business performance (Bedford and Morelli, 2006; Choo, 2013; Ladley, 2010; Schiuma, 2012; Willis and Fox, 2005) and help organizations achieve competitive advantage by enabling delivery of cheaper or more differentiated products (Citroen, 2011; Porter, 1980). More efficient and effective deployment of these assets can increase revenue, reduce cost, improve profitability, mitigate risk, improve compliance and increase competitiveness (Bedford and Morelli, 2006; Oppenheim, Stenson and Wilson, 2001; Young and Thyil, 2008). Information asset management also supports collaboration whereby people from across the organization can collect information that could be of benefit to others (Bedford and Morelli, 2006). These information assets should therefore not be treated as an overhead expense, but rather as an important source of business benefit (Evans and Price, 2012; Laney, 2012; Schiuma, 2012; Strassmann, 1985). The latter part of the twentieth century witnessed an increasing recognition of the importance of information assets as the only form of sustainable competitive advantage (Parsons, 2004).

Information assets are different from most other resources. The potential value of an information asset is not a reliable indicator of its actual value: if the value is never crystallised, there is no benefit to the organization (Eaton and Bawden, 1991; Evans and Price, 2012). Higson and Waltho (2009) state that although information assets are the main source of value in a business, the accounting rules do not allow their inclusion in the balance sheet. They further emphasise that 'just because intangibles cannot be counted on the balance sheet does not mean that they do not count and should not be counted'

Despite the recognition that information assets are the lifeblood of a business, most organizations still do not manage data, information and knowledge well. A 2007 study found that fewer than ten percent of the participating organizations were using documented processes to manage these assets (Swartz, 2007). Several authors refer to a lack of information culture that supports information sharing and management (Abrahamson and Goodman-Delahunty, 2013; Oliver, 2011; Widén and Hansen, 2012). Evans and Price (2012) confirmed that executive level managers acknowledge the existence and importance of information assets in their organizations, but they found that that hardly any mechanisms are in place to ensure the effective governance and management of these valuable assets. The barriers to effective information asset management were found to be a lack of executive awareness, a lack of business governance, ineffective leadership and management, difficulty in justifying information management initiatives, and inadequate enabling systems and practices. Without understanding the barriers, it is impossible to improve the management of these crucial assets to reduce risk, improve decision-making, improve competitive position and increase return on investment.

Changes and challenges in the legal industry

The legal industry has been facing unprecedented change. Law firms face an increasingly competitive market as large accounting firms, which withdrew their legal practices from the market, are now re-establishing their legal practices and leveraging the intelligence gathered by their auditing teams. organizations are also increasingly appointing in-house counsel, thereby reducing the amount of work available to the market and increasing pressure on firms to demonstrate value (The College of Law, 2014). Segal-Horn and Dean (2011) add that globalisation challenges law firms to expand their operations overseas. Alternatively, some firms will maximise competitive advantage by targeting a specific geography or area of legal practice (Kabene, et al., 2006). The legal industry is also experiencing increased numbers of mergers and acquisitions as a result of the amplified competition (Chilton, 2014), which results in emotional, practical and time burdens as different cultures are merged into one (Beaumont and Marshall, 2011).

The great recession or global financial crisis has put pressure on law firms to manage their finances more rigorously. The legal industry has shifted from being a sellers' market to a buyers' market where clients exercise greater influence over how legal services are delivered and insist on increased efficiency, predictability and cost effectiveness (Evans, 2015). Clients are often ahead of lawyers in implementing new technologies, and they also have improved access to the legal information that is readily available on the Internet (Kabene, et al., 2006). Clients of law firms are therefore becoming increasingly sophisticated and demanding (Muir et al., 2004). There is more pressure on law firms to move away from the traditional pricing mechanism (Tjaden, 2009) where time is billed in six minute increments. Pricing models are therefore changing with the introduction of alternative fee arrangements such as blended rates, capped fees, fixed prices, value pricing, staged costing, event costing, and success fees (Blanco and Latta, 2012). Law firms need to provide accurate, reliable and scalable reporting to effectively manage alternative fee arrangements and other complex billing structures (Dunford and Le-Nguyen, 2014).

There is a proliferation of legal information assets, the so-called information overload (Jarvis 2013) and merely identifying and managing these assets becomes a challenge to legal firms. Advances in technology are provoking law firms to embrace information management systems, technologies and social media (Kabene, et al., 2006). New technologies enable new workplace practices to emerge. For example, storage capacity in the cloud allows customer, case matters and other firm information to be stored centrally and accessed from work or home with significant cost savings. Firms realise that bring-your-own-device programmes can increase staff productivity by providing a more flexible work environment, and device mobility enables lawyers to access digital documents in court.

Law firms use tools such as intranets, expert systems, online dispute resolution systems, and knowledge management tools such as decision support systems, document management systems and artificial intelligence tools. Content management systems allow law firms to search, manage and retrieve information stored both internally and externally (Bedford and Morelli, 2006; Du Plessis, 2011; Gliddon, 2014; Khandelwal and Gottschalk, 2003; Mezrani, 2012; Moore, 2013; Shipman, 2002; Teece, 2000; Winston, 2014). Few law firms have yet embraced social media due to security risks to client information and intellectual property issues (Du Plessis, 2011; Khandelwal and Gottschalk, 2003; Moore, 2013; Winston, 2014).

The demographics of law firms are changing. Blanco and Latta (2012) noted that there is an age and gender balance shift. The average age of lawyers is decreasing and the proportion of female lawyers is increasing. The increase of female and younger law graduates and professionals challenges law firms to implement flexible working conditions such as part-time work and telework (Thornton, 2016). Djak (2015, p. 523) emphasises that the challenge to law firms is to provide flexible working conditions without the 'stigma of affirmative action' initiatives which benefit and 'accommodates' women, as this discourages employees from taking advantage of the opportunities.

Primarily due to the way lawyers have traditionally been compensated, time billing rewards inefficiency and dilatory practices. Work in law firms is often duplicated by several lawyers (Kabene, et al., 2006; Khandelwal and Gottschalk, 2003) and is not helped by the resistance to moving to electronic documents (Gliddon, 2014; Muir et al., 2004; Teece, 2000). As noted, there is increased pressure on law firms to be more efficient and productive. Business clients are no longer willing to pay lawyers to deliver work that is regarded as inefficient and expensive (Dublin, 2005; Lambe, 2003). Law firms must enhance their operational efficiencies in order to remain competitive (Hunter, Beaumont and Lee, 2002).

One of the major challenges facing law firms is implementing knowledge management practices. Law firms are 'in the knowledge business' and they have to share knowledge (Lambe 2003) to increase innovation, build adaptive and agile organizations, develop the institutional memory of the firm, and improve the organization's internal and external effectiveness (Zeide and Liebowitz, 2012). However, there exist few financial or other incentives for lawyers to share knowledge with their colleagues (Blanco and Latta, 2012; Gottschalk and Karlsen, 2009; Kabene, et al., 2006). The primary source of a lawyer's income is derived from time spent with clients (Lambe, 2003) and lawyers working on the billable hour system do not want to spend time on corporate knowledge management activities, which cannot be billed (Sukumaran, et al., 2013).

Research methods

The literature review was followed by an empirical investigation, based on qualitative research methodology. An important aspect of qualitative research in organizations is to gather the opinions and experiences of professionals, managers, executives and consultants (Bruner, 1990; Scholes, 1981; Swap et al., 2001; Tulving, 1972). Personal interviews were conducted with nineteen senior lawyers and legal business managers in Australia (A1–A7), the United States (U1-U4) and South Africa (S1-S8) (refer to Table 1). Purposive sampling was used to select participants. The sample size was not pre-specified, but determined on the basis of theoretical saturation, namely the point in data collection when new data no longer bring additional insights to the research questions. The sample is large enough to reach such theoretical saturation. Legal practitioners' perspectives were sought, rather than statistical significance.

| Firm and position |

|---|

| Australian firms (A1-A7) |

| A1 Managing partner |

| A2 Chief operating officer |

| A3 Director |

| A4 Managing partner |

| A5 Chief information officer |

| A6 Chief operating officer |

| A7 Lawyer |

| United States firms (U1-U4) |

| U1 Attorney |

| U2 Data management |

| U3 Chief operating officer |

| U4 Equity partner |

| South African firms (S1-S8) |

| S1 Owner |

| S2 Managing director |

| S3 Director |

| S4 Chairman of the board |

| S5 Director |

| S6 Lawyer |

| S7 Partner, Knowledge Management manager |

| S8 Partner |

The confidential interviews were conducted face-to-face and lasted between forty minutes and one hour. Particular attention was paid to the consideration of confidentiality of sensitive corporate information. Consent was sought, confidentiality agreements were signed, security provisions were undertaken, and names of individuals and organizations remain unidentified. Consequently, the participants were willing to enter into open and trusting discussions. Each interview was audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Respondents had the opportunity to review the transcripts of their responses as well as the de-identified and consolidated data.

An interview protocol was used to focus the discussion and to promote a consistent approach across a number of interviews (Flick, 2006; Miles and Huberman, 1994; Swap et al., 2001). The questions were open-ended and discovery-oriented. Business questions were asked to provide context, followed by questions about information management and its challenges, as well as probing questions to elicit more detail. Both planned prompts (predetermined) and floating prompts (impromptu decisions to explore a comment in more detail) enabled the researchers to delve into detail as required. The interview protocol covered the following areas:

- What is unique about the legal industry and how is it changing?

- What information assets, i.e. data, information and knowledge, do you deploy in conducting your business?

- How well are the information assets managed in your firm?

- What challenges do you experience in managing the firm's information assets?

Analysing qualitative data involves significant effort (Flick, 2006; Miles and Huberman, 1994). The interview transcripts were separately analysed by each of the researchers, aided by the NVivo 10 qualitative analysis software, and then discussed to iteratively identify common patterns or themes (McFadzean et al., 2007; Strauss and Corbin, 1998). Open coding was used to disentangle or segment the data to produce a set of codes. Axial coding was used to refine and differentiate the categories arising from the open coding, and to identify the categories that were most relevant to the research questions. As a third step, selective coding was used to continue the axial coding at a higher level of abstraction (Flick, 2006). The themes are shared in the next section as the major findings of the study.

Findings

Information asset management in law firms

According to the interviewees, information assets used in participating law firms include patents, trademarks, templates, precedents, e-mail, clients' business information, past matters, precedents, research notes, financial transaction documents, summaries of projects, billing records, time recordings, reports, curriculum vitae, marketing materials, flyers, web sites, social media, briefs, dispositions, motions, leases, contracts and standard operating procedures. Participants realise that these information assets are important to law firms:

Our job is purely information. On a minute by minute basis, that's all our job is [..] 100% of it is information. So how do we find better ways to capture, catalogue, index, store, present our information? It's really key (U4).

Although information is fundamental to a law firm, it is not managed well. A managing partner (A4) in an Australian firm agreed that they are a long way from optimising the capture and organization of information, 'so there's lots of head room and we can do it a lot, lot better'. An equity partner (U4) from the United States indicated that they have 'plenty of data all over the place, but because they are not connected it is a total failure'. He admitted that his firm spends a lot of time looking for information, whereas they would rather spend time thinking. He also referred to the disadvantages of using e-mail:

Every time my brain stops as a result of an e-mail notification, there's an impact. There is very little time to just close your door and deal with a matter. There is so much informational stimulation that you get overwhelmed (U4).

Finding relevant information is a challenge. A partner in a South African firm admitted:

This firm is like a library with no index. You don't know where to start finding something and you can search around forever (S2).

When asked whether information is managed with the same rigour as financial assets, a partner (S8) responded: 'No, it is like chalk and cheese'. A managing partner commented that information assets are less tangible and therefore not respected in the same way:

There must a bit of irony here. You are pushing for financial performance and the management of information can contribute to their efficiency and differentiate their service to others. I think [information management] does impact on financial performance, but it's a bit secondary because it is not as direct (A1).

A managing director (S2) stated that information, which is the commodity that they sell, is managed much more haphazardly than their financial assets. When the equity partner of a US firm (U4) was asked what his firm would look like if its money were managed the same way as its information, he pointed at a spot on the floor and said: 'My firm would be like that bloke there – invisible, non-existent'.

Performance management generally does not include a focus on information management. Information management is not on the checklist of partner reviews, according to S8, while S2 believes it should be included, as information management will only capture the imagination of the board of directors if it is elevated to a higher level.

Employees of law firms are often motivated only to succeed in their area of expertise (A5) and no-one is held accountable for the management of information as an enterprise asset. The managing director of a large law firm (S2) confirmed:

Do we have a responsible person for managing information/documents? There is definitely no such person. Everybody is responsible for managing their own information. We don't keep record of the information at all. The only management is that the templates are on the system. Only a few people in the office can make changes to the template. This is the only information management we have in the firm. (S2)

The majority of the participants referred to either the librarian or the chief information officer as the custodian or manager of the information assets. However, when prompted further, A1 remarked that no one is really accountable, because nobody is rewarded or punished for their information asset management practices.

Changes in the legal industry

The changes as identified in the literature review, were supported by the interview participants. The following themes were identified during the interviews:

Increased competition

Changes in the legal industry include heightened competition from new entrants and in-house counsel, globalisation, consolidation through mergers and acquisitions, as well as partnering. The competitive pressures of business now also apply to legal firms and lawyers cannot think the way they did twenty years ago (S3). In-house counsel takes the work that lawyers used to do (A1) and acts as 'gatekeeper in terms of legal spend' (A7). Demand for legal work is also increasingly being satisfied by the Big Four accounting firms, namely Deloitte, Ernst & Young, KPMG and PwC (A3). The legal industry is also seeing increased competition due to globalisation and international law firms growing their market (A3). Other sources of competition are partnering as well as mergers and acquisitions (U2). Technology and greater access to information also creates new competition:

If you want a discretionary trust set up you would have paid, few years ago, over a thousand dollars for that. I'm sure that if one of us got our smart phones out we could source within two minutes a discretionary trust for 200 bucks (A1).

Increased client sophistication

One of the most important changes to the legal industry is that clients are more informed and demanding:

Clients are very specific in what they want to have done... They say what they want to have done and what pricing they want. Why? In-house counsel advises clients on how to get a better deal. They also have sophisticated procurement teams who negotiate a better deal (A7).

Clients have increased access to information:

A lawyer is not like twenty years ago; people don't have respect for the lawyer. They look on Google and tell you how to do the work. Especially the young people – they want their way and don't want to pay for the service (S1).

So we need to be pretty efficient and be able to demonstrate value because the people who we are providing a service to are far more sophisticated than they used to be (A1).

Financial pressures

The global financial crisis has put financial pressure on companies around the world and created a need for rigorous financial management. Law firms are no exception (S2). They need to do more with less (S4, S5). The equity partner (U4) added that market forces are driving up salaries for lawyers and the cost of law school is increasing so resources are not getting any cheaper. Law firms therefore have to do what they have always done, but more efficiently, more cheaply and in more creative ways (U4).

Changes in technology

As identified in the literature review, the development in technologies such as the Internet, social media, artificial intelligence and knowledge management tools have changed the business landscape within which law firms operate. A7 referred to the 'amazing stuff' available, such as machine learning and document management. A6 gave an example of an artificial intelligence system, namely contract review software for sale agreements and due diligence when buying a company.

A6 added that once you have a document in electronic form, it is possible to use the IBM Watson system to mine data in the systems. He added that it can be very powerful to connect with voice files, e-mails and documents, as 'one can ask a question to the system and it will come back with a few scenarios, like the librarians do' (A6).Information proliferation

Like most other industries the legal profession is suffering from a proliferation of information, which, if unmanaged, creates significant administrative burden on the firm:

Our biggest issue is the administrative burden […]. It feels like we're not lawyers anymore, we are administrators; we are buried in information (S1).

We're busy with an administrative paper war, we have masses of paper. This has to change and we need to work electronically to allow us to work quicker and save time to do other things (S2).

Changes in demographics

Corroborating the literature, there is an improvement in information technology literacy due to an increase in young lawyers entering firms and a corresponding cultural shift. U1 said that younger attorneys are much more comfortable with the electronic method of communicating, but added that he prefers to talk to people. The new generation of lawyers are more used to sharing information online through social media tools like Facebook and Twitter (A1). Older lawyers may also be reluctant to transfer their knowledge to younger lawyers because of discomfort or unfamiliarity with the use of technology (S8):

If I have to be rated by the young people they rate me as an imbecile as far as the new technologies are concerned. I like to make notes on a hard copy of a document and not stare at a computer screen the whole day. We will probably go extinct one of these days.

S8 added that the younger partners are also more 'business oriented' than the older ones, who remain concerned purely about the practice of the law. This has implications for the future management of the legal firm, including the use of its information assets.

Challenges faced by law firms

The challenges created by the abovementioned changes to the legal industry, were identified during the interviews. These challenges are described below:

The challenge to present a value proposition

Law firms are forced to be more creative about billing arrangements, because clients want more service for lower prices (S2), increasingly demand fixed price quotes (A4), and expect firms to respond to requests for tender. Lawyers regard tendering as a huge challenge and it is difficult to estimate a fee beforehand, as they do not know how much work they will be required to do to give a reasonable service to the client (S8).

The challenge to develop an effective business structure

Firms have determined that they need to operate in areas where they have a competitive advantage, resulting in stratification of legal services and specialisation within those strata. A number of participants referred to the commoditisation of legal services. A managing partner (A1) said that law firms have been able to live pretty well doing a lot of relatively standardised work and this is now catching up with them as there is an ever increasing quantity of precedents and other material available on the Internet. However, a senior lawyer (S3) emphasised that all templates need to be 'panel beaten to fit the new scenario', while a director (A3) emphasised that it is important to understand what information is valuable. Law firms need to do what computers cannot do on their own and therefore to be competitive they need intellect, expertise, information and knowledge (A1).

For example, a pack of information was made available free to start-up businesses containing shareholder and employment agreements and information about running a business. A managing partner said:

It is not the document or piece of paper that is valuable. If it was valuable they would not be giving it away for free. What is valuable is the knowledge and the awareness of how to use those documents (A3).

The challenge to respond to and leverage changing demographics

Retirement of senior lawyers also leads to valuable knowledge loss, mostly due to improper documentation by the firm. Law firms are challenged to capture specialist knowledge and transfer it to the young lawyers to allow the firm to provide a continued high quality service to its clients. The managing partner of a large law firm in Australia (A1) acknowledged that there is only a degree of encouragement for retiring lawyers to contribute to the opinions register, but added: 'yet we don't do that in any formal way'. S8 said:

If I leave I would walk away with my wisdom. That's just the way it is. It is very difficult to capture my knowledge before I leave. I can tell you now that that will not happen.

The chairman of the board of a large and established law firm (S4) explained why they still prefer to work with hard copy, because 'some of us just like the smell of paper'.

The challenge to embrace technology

Resistance to technology remains a major challenge in law firms:

At the end of the day the pressure of delivering to the clients probably outweighs the perceived benefit of the systems. Unless the systems are really easy to use, you run out of time because you are trying to build in efficiency (A3).

If there are no incentives to use technology, lawyers' behaviour will not change:

I encourage people that whenever they produce any document or give any advice that is unique to send it to our library people for inclusion either in precedents or in the opinions register. The problem with that is, not everyone thinks to do it […] because you're busy. We don't push it as much as we should (A1).

The challenge to improve operational efficiency

Unlike most other industries, lawyers are often rewarded for being inefficient (A4) because they bill by the hour. This has led to 'laziness in thinking about how service delivery can become more efficient' (A3), for example, around finding information quickly:

Over time lawyers have got away with a model of 'the longer something takes, the more it will cost [the client] and the more [the law firm] can charge'. It's a really serious issue in terms of the cost of justice and the cost of legal services. I'm a beneficiary of that but it's madness from a commercial perspective (A4).

The changes in the legal industry make it imperative that firms become more efficient and productive:

We need to work electronically to allow us to work quicker and save time to do other things... If we can manage the knowledge better, people don't have to start doing research from scratch and reinvent the wheel. Lawyers complain that [others] take their work, but it is our own fault (S2).

In addition to the business benefit of efficiency, there is a risk in not doing so. For example, when information is saved on individual computers it cannot be accessed by anyone else:

The secretary stores the document she changed for me on her own hard drive. She just doesn't think about other people needing it. If something happens to her it will be a bit of a challenge to find it as everyone saves information in their own way (S4).

The challenge to improve information asset management

Lawyers resist the transition from working with hard copy to working with electronic copies of documents:

We put in a new matter management system, so that we could have paperless files - this is going back four or more years or so ago now. The heat I took over that was unbelievable (A4).

Maintaining client privacy is paramount in law firms and moving from the familiar management of hard copy to the unknown management of digital documents creates concern. The equity partner of a law firm (U4) said that 'information security is important because we are handling clients' intellectual property and information that is sensitive and proprietary'. A senior lawyer of a US firm indicated that everyone in the firm is responsible for privacy and confidentiality obligations:

We have a policy that outlines the expected behaviour regarding confidentiality that they sign annually (U1).

The challenge is to motivate lawyers to take this responsibility:

Case documents need to be made anonymous to be reused. However, this needs to be done by a lawyer who understands what is relevant and crucial, but not everyone is interested in doing this (A1).

The need to manage knowledge is an ongoing challenge within law firms. Most law firms encourage individuality and therefore lawyers are often not interested in sharing knowledge with others. A director of an Australian firm (A3) agrees that individuals need to hit their time budgets or deliver their volume of new revenue to the business, so they are not incentivised to collaborate for the greater good of the firm. Furthermore, the success of a partner is based on the number of cases they attract and win. This makes practitioners hesitant to share knowledge and risk losing their competitive edge. Although the directors of a large law firm in South Africa share knowledge around the water cooler, not everyone is involved in the discussions. The managing director and chair of the board (S4) said:

We eat lunch and discuss with each other. We learn a lot between us directors, but the rest don't share in the knowledge. It would be cheaper if they [junior lawyers] can do the work; we need to empower them to do the work so we can be a smarter firm. We want to increase the 1% that actually shares to 100%.

Lawyers protect their access to clients (A5). A director of a South African firm (S3) agreed that it is important, yet difficult, to motivate people to share their contacts:

This type of information is not stored anywhere at all. I'll have to ask all my senior partners. The senior partners' contacts are the real experts. We need a system to store this, with a rating on how valuable the contact is. It is the firms' information, not your own (S2).

As competition increases, people are relatively mobile between law firms and retention of knowledge becomes an important challenge. A2 commented that the photocopying bill goes up when a partner leaves because they are copying all their documents to take with them. The senior partner of a firm added:

People just load our IP [intellectual property] on a memory stick and walk away with all our information. This is a large risk of developing a KM system (S3).

Challenge to change culture and the behaviour of individuals

A chief operations officer of an Australian firm (A6) is of the opinion that lawyers passively resist rules for managing information. The managing director of a large law firm in South Africa refers to this behaviour as 'civil disobedience' or 'political will' (S2). An Australian chief information officer (A5) commented: 'We need a carrot coloured stick to change this'. The chief information officer of a county attorney's office (U3) added that whilst information management policies have been endorsed by the county's chief administrative officer, people will find workarounds if they do not like the system. Further, people are prone to store information in their own environments. There is no compulsion to use the system and the county attorney's office relies on individuals' professionalism to ensure that it is used. A5 is of the opinion that they need to show people why improved information management is going to be better for them, not be too directive.

Responses to the challenges identified

By and large firms are starting to respond successfully to some of these challenges. They are offering increasing predictability of their fees and cost-effective pricing. The industry is seeing the advent of business models such as bodies corporate and listed entities, which are different from the traditional, partner owned law firm. In order to expand cross-border business and networks to attain global status, legal firms are increasingly forming alliances. Firms are stratifying their services to create competitive advantage. A2 commented that to be more competitive they needed to restructure their business, which is why they are not a full service law firm anymore.

Firms are no longer necessarily partnerships in which a managing partner adopts the role of part time chief executive officer. Instead, they can be corporate entities, provided that their directors are attorneys. Large corporations are emerging with business people at the helm and a growth, profit and efficiency incentive that will enable them to achieve competitive advantage.

We need to effectively make the partners employees, and the only way we can see doing that is to publically list the law firm. Partners then become employees and we will have a carrot and a stick that we can wave in front of them and change their behaviours. If we try to do this at a traditional partnership level it would be impossible, because they won't want to change (A6).

The findings show that legal work is separating into three streams. These three streams require different approaches to be profitable:

- Top end consulting work (bespoke advice) that requires experience and expertise (A3), 'where clients just want to talk to someone and pick their brains' (A7).

- Commoditised work that tailors existing documents (templates) and requires both systems and expertise (A3), i.e., work that is more reliant on technology (A7).

- Process work that is high volume, standardised and repetitive, such as wills that can be automated and produced at the push of a button (A3). For this type of work 'you have to have the systems to run like a beautiful machine' (A7).

Some law firms are starting to respond to the pressure to increase business efficiency. Although information is not managed well in most law firms A7's firm is starting to realise that improving information management means they can be faster and more agile.

So where do you see efficiency? Well, you see it in commoditised legal work. The market says 'I'll pay $800 for a lease', so what do lawyers do? Get really, really good at pushing that lease out the door in a fraction of the time (A4).

The managing partner in an Australian firm (A4) believes:

We're at a place on the [information management] spectrum; it's not the case that there's no management of intellectual property, [knowhow] or information. In fact, substantial effort goes into both capturing and organizing information. These conversations weren't happening three years ago, just not happening (A4).

In one South African firm executive leaders encourage information management practices in their firms by providing incentives to do so:

We have a little coaster with our icon and slogan and when a person arrives at work they will find such a coaster with a cupcake on their table with a note thanking them for their contribution. It's a bit corny but people love it (S7).

In A6's firm, management is encouraging the use of technology and younger attorneys are predictably more comfortable complying. The participant noted that although technology cannot increase output, it can make the process to achieve that output more efficient. Instead of one lawyer producing five documents a day, they can put the content of those documents in the system and produce ten documents a day. A7 agreed that if they can 'get through more work' they can charge more. A5 commented that 'law is not an ancient profession anymore' and that there is a recognition that embracing technology will help drive business improvement:

You've got to have people who know how to apply the tools effectively and who [are able to] use technology tools to find information (A7).

Firms are encouraging their lawyers to contribute documents of business value to the firm's repository, or else they will have a certain proportion of their profit share at risk. A4 commented:

If you've got 20 grand [in bonus] swinging whether or not you download all the relevant documents into our [knowhow] database at the conclusion of every matter, it will happen. Because there's no doubt that remuneration systems drive behaviour (A4).

One South African firm implemented a formal knowledge governance structure where a knowledge partner was identified for each of the nine practice groups. A knowledge lawyer who reports into the practice partner, was appointed to play the role of champion of knowledge for that group. The knowledge partners are accountable and the knowledge lawyers are responsible for ensuring that knowledge is captured and shared at every possible opportunity. According to the knowledge manager (S7) and a senior lawyer (S6) knowledge management is ongoing work in progress in their firm. S7 added that they have come a long way but there is still so much more to do.

Discussion

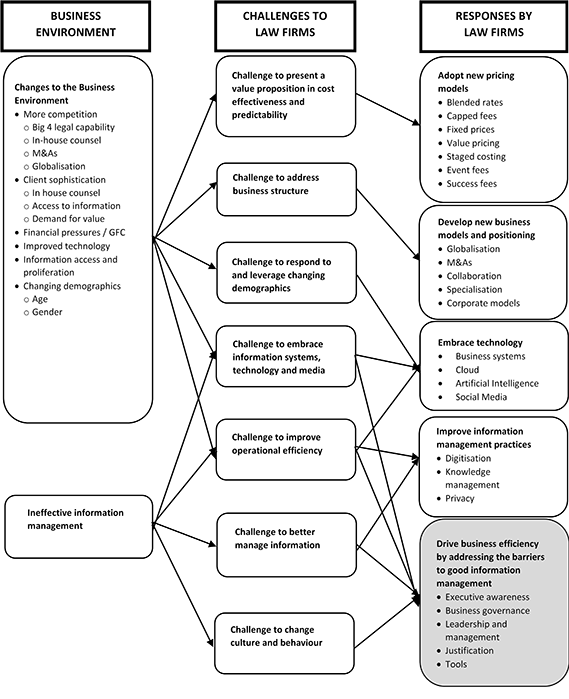

The evidence from literature and the empirical study indicating that the legal industry is not only undergoing significant change, but suffers from poor management of its information assets, is illustrated in Figure 1. The changes to the business environment are driven by heightened competition in the marketplace, increased client sophistication, additional financial pressures, ubiquitous technology, a proliferation of information, and changing demographics of law firms. In all three countries, changes to the legal industry are driving competitive and commercial challenges and forcing firms to become more efficient. As indicated by the arrows in the relationship diagram (Figure 1), the changes to the legal industry's business environment create challenges for firms which must present new pricing models, adopt clear market positions, embrace technology and improve operational efficiency. Additionally, the current ineffective management of firms' information assets drives the need to change from hard to soft copy, ensure privacy, manage knowledge, embrace technology, change culture and behaviour, and increase operational efficiency. Firms must adapt or perish.

By and large firms are responding successfully to these challenges. The challenge to present more attractive pricing and value propositions is being responded to through new pricing models. Firms are offering increasing predictability of their fees and cost-effective pricing. Similarly the challenge to clearly articulate competitive advantage has resulted in the development of new business models and positioning. Firms are also embracing technology. The industry is seeing the advent of corporate entities with a growth, profit and efficiency incentive to achieve competitive advantage.

Some areas remain that would benefit from improvement. The two key resources for a legal firm are its people and the information assets they use to advise their clients. Managing information well can play an important role in achieving the business objectives because it has the potential to increase efficiency and effectiveness within the firm (Kabene et al., 2014). The practice managers and lawyers realise that improved information asset management can provide their firms with increased revenue, reduced cost and risk, increased profit, competitive advantage, growth and sustainability. In line with literature, a chief executive officer (U2) emphasised that information is more than fundamental, it is vital to the firm. Furthermore, if lawyers do not have knowledge in their heads or the ability to find it somewhere, they do not have the ability to service a client and therefore they do not have a business. A managing partner (A1) observed that firms that manage their information better will get ahead.

Information asset management across all industries is being driven by a range of factors. This includes a need to improve the efficiency of their processes, the demands for compliance regulations and the desire to deliver new services to their clients (Robertson, 2005). Everyone in an organization, especially executive managers and senior partners, need to understand the importance of effective information asset management. Without that understanding, there is little chance of their strategies being implemented successfully (Swartz, 2007).

The literature and the findings from this research indicate that information assets are not managed well in all industries, and this is particularly true of the legal industry, which is information and knowledge intensive. Every one of the changes and challenges in the legal industry has an information management component: informing customer access, relationships and service; the scoping and planning of matters; the pricing of proposals; business and professional decision making; the firm's profitability and competitiveness; risk management; service delivery; as well as lawyer and staff behaviour. It is therefore incumbent upon every legal firm to improve its information management practices. As the primary resources at firms' disposal are their people and the information they use, changing behaviour and improving information practices is imperative, that is, they need to develop an information culture (Abrahamson and Goodman-Delahunty, 2013; Oliver, 2011; Widén and Hansen, 2012). Successful law firms understand the importance of effectively managing their information to drive down costs, to increase revenue, to manage risk, to improve competitiveness and ultimately, to maximise their profit.

Based on the research, firms are responding well to the challenges they face with one exception, the management of their information assets. Despite the importance of information and knowledge to law firms, typically they do not demonstrate an awareness of, or interest in data, information and knowledge management and therefore do not address the fundamental barriers to good information asset management (illustrated in Figure 1). There is usually a profound lack of business governance applied to the management of information. There is often a lack of leadership and management: for instance, few legal staff have key performance indicators around timeliness and accuracy of information. Information management is often difficult to quantify and consequently difficult to justify, and business instruments such as international accounting standards and consistency of language are rarely fit for purpose.

The ability of law firms to overcome the challenges to improve operational efficiency, change from hard to soft copy, ensure privacy, manage information assets and change the culture and behaviour are being hampered by significant barriers to improving information management practices. These barriers must be addressed.

Figure 1: The conceptual framework

Conclusion

This project was conceived following observations that the global legal industry faces unprecedented change, inevitably generating challenges for individual law firms. The findings from our research show that law firms are responding. However, like most organizations in most industries, law firms are still not effectively managing their information assets.

In this paper we posit that the inefficient management of information assets can be overcome by addressing the five categories of barriers to information asset management as identified by Evans and Price (2012) (refer to the shaded part of Figure 1). The barriers relate to: the awareness by executives of the importance of managing information as a business asset which requires education and training; business governance which addresses the issues of the ownership of, the responsibility for and genuine accountability for delivering information in an accurate, timely and relevant fashion to the people who need it; the leadership and management to create a culture that values information and provides incentives to manage it well; a penetrating understanding of what it costs to manage a firm's information, the value of that information to the people who need it and the benefit to a firm of good information management practices; and the fitness for purpose of business tools including consistent business language and international accounting standards.

Firms need to educate their executives that information is one of two most important assets in law firms. They need to impose genuine accountability on someone with the authority to manage information as the firm would manage its financial assets. They also need to imbue a culture of valuing and managing information assets by, amongst other initiatives, providing incentives to manage information as an enterprise resource to drive competitive advantage (Oliver, 2011). For example, evidence from other industries suggests that imposing key performance indicators around the accurate and timely provision of information makes staff value their information more and, in turn, manage their information better. Information management is everyone's job (Young and Thyil, 2008). People on all levels of an organization should manage and leverage information as an asset (Laney, 2012). Executives need to recognise the cost and value of their information and the benefit of managing it well. Firms also need to implement appropriate business management tools and solutions that are both effective and easy to use.

Recommendations

From the research we suggest that law firms implement solutions that are practical and deliver tangible, measurable benefit to each individual and the firm as a whole. This can be done through the following steps:

- 1. Develop business governance and information asset governance frameworks that will guarantee the management of data, information and knowledge as a vital business asset.

- 2. Develop a stakeholder management and behavioural change plan (including performance incentives and awards) to educate all levels of staff in the law firm in the importance and benefits of effectively managing information assets.

- 3. Implement the effective leadership for and management of information assets:

- 3.1 Design a vision of the future;

- 3.2 Determine the law firm's current information management practices;

- 3.3 Extrapolate the business impact that those practices have on the firm;

- 3.4 Determine the potential benefits of improving information management practices;

- 3.5 Develop and implement an information asset management strategy and project roadmap.

- 4. Design an information asset management justification model and implement a benefits realisation programme.

- 5. Relentlessly drive measurable business improvement.

By undertaking these steps appropriately law firms will improve the management of their information assets. In step 2 the specific barriers currently faced in the organizations should be identified and penetrating investigation is required. The authors caution firms not to rely on traditional information technology solutions, but to adopt innovative thinking to effectively address all five barriers. This, together with the current responses to the challenges they face will enable firms to become more competitive, profitable and better able to mitigate their business risk. Current evidence that information asset management will benefit the organization is anecdotal, but this will be formalised in the next phase of the research, as discussed in the next section on suggested future research.

Limitations and future research

The study is subject to the general limitations associated with this type of qualitative research, particularly regarding the lack of generalisation of findings from a limited number of participants.

We propose further research to validate the findings of this research by conducting a formal information asset management practice assessment (health check) and business impact assessment. Formal benchmarking of information asset management practices across the legal industry will allow researchers to compare law firms' information asset management processes and performance metrics against a baseline. Such benchmarking could compare information management performance against corporate objectives at a point in time; forecast or desired improvement over time; the performance of industry peers; and published standards. Participating in the benchmarking exercise would allow firms to gain an understanding of how well they are managing their information assets and to develop a roadmap for improvement. They would also gain insight into the impact of those practices on their businesses and the potential benefits from improving them. Participating in a benchmark exercise and improving the management of information assets should increase productivity, raise revenue, reduce costs, improve profit, manage risk, improve work quality, create competitive advantage, cement brand awareness and customer relationships and improve morale.

About the authors

Nina Evans is Associate Head of the School of Information Technology and Mathematical Science (ITMS) at the University of South Australia (UniSA). She holds tertiary qualifications in chemical engineering, education, computer science, a Masters' degree in Information Technology, an MBA and a PhD. Her research interests relate to information and knowledge management, managing the usiness-IT interface, the use of ICT in Education, and ICT innovation. She can be contacted at nina.evans@unisa.edu.au

James Price is the Founder and Managing Director of Experience Matters. The firm is based in Adelaide, Australia and takes a position of global leadership in the business aspects of Information Management. He does research in the field of information asset management and is currently working on a project investigating various aspects of the subject on three continents. He can be contacted at james.price@experiencematters.com.au

References

- Abrahamson, D.E. & Goodman-Delahunty, J. (2013). The impact of organizational information culture on information use outcomes in policing: an exploratory study. Information Research 18(4). Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/18-4/paper598.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6ncwv2MBp)

- Beaumont, J. (2010). Knowledge management in a regional law firm: a worthwhile investment or time wasted? Business Information Review, 27(4), 227-232. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0266382110389296 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6ncx1Ibij)

- Beaumont, J. & Marshall, H. (2011). With change comes challenge: law firm mergers. Legal Information Management, 11(4), 289-293.

- Bedford, D. & Morelli, J. (2006). Introducing information management into the workplace: a case study in the implementation of business classification file plans from the sector skills development agency. Records Management Journal, 16(3), 169–175.

- Bhatt, Y. & Thirunavukkarasu, A. (2010, March 1). Information management: a key for creating business value. The Data Administration Newsletter. Retrieved from http://www.tdan.com/view-articles/12829 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6ncxSmyX8)

- Blanco, L. & Latta, C. (2012). Knowledge management in Australian law firms and the accelerating rate of change. Sydney, NSW: Colin Biggers & Paisley. Retrieved from http://www.cbp.com.au/publications/2012/december/knowledge-management-in-australian-law-firms-and-t (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6ncxQ524T)

- Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Chilton, S. (2014). Moving times. The Journal of the law Society of Scotland, 18(2). Retrieved from http://www.journalonline.co.uk/Magazine/59-4/1013856.aspx (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6ncxfy61o)

- Choo, C.W. (2013). Information culture and organizational effectiveness. International Journal of Information Management, 33(5), 775–779.

- Citroen, C.L. (2011). The role of information in strategic decision-making. International Journal of Information Management, 31(6), 493–501.

- The College of Law. (2014). What's on the horizon for the legal industry in 2014? Retrieved from http://www.collaw.edu.au/insights/whats-horizon-legal-industry-2014/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6nczuUpM4)

- Crosby, C. (2012). An introduction to knowledge management for law firms. Toronto, ON: Crosby Group Consulting. Retrieved from http://www.slideshare.net/conniecrosby/law-firm-knowledge-management-an-introduction-13192279 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6ncxYeaEz)

- Djak, I. (2015). The case for not 'accommodating' women at large law firms: de-stigmatizing flexible work programs. Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics, 28(3), 521-544.

- Du Plessis, T. (2011). Information and knowledge management at South African law firms. Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal, 14(4), 233-258.

- Dublin, M. (2005). Creating an environment in law firms where knowledge management will work. ArticleCity. Retrieved from http://www.articlecity.com/articles/legal/article_165.shtml (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6ncxiLPPD)

- Dunford, N. & Le-Nguyen, M. (2014). Five trends affecting legal CIOs. CIO. Retrieved from http://www.cio.com.au/article/538951/five_trends_affecting_legal_cios/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6o9hJRm0Q)

- Eaton, J.J. & Bawden, D. (1991). What kind of resource is information? International Journal of Information Management, 11(2), 156–165.

- Evans, C. (2015). 2015 state of the legal market. Melbourne, VIC: Melbourne Law School and Thomson Reuters. Retrieved from https://peermonitor.thomsonreuters.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/2015-AU-Report-FINAL.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6ncydhjvl)

- Evans, N. & Price, J. (2012). Barriers to the effective deployment of information assets: an executive management perspective. Interdisciplinary Journal of Information and Knowledge Management, 7, 177–199.

- Flick, U. (2006). An introduction to qualitative research. London: Sage Publications.

- Frost, A. (2013). The different types of knowledge. Knowledge Management Tools. Retrieved from http://www.knowledge-management-tools.net/different-types-of-knowledge.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6nd0CRbDi)

- Gliddon, J. (2014, July 16). Electronic documents: can law offices go paperless? Legal Insight. Retrieved from http://insight.thomsonreuters.com.au/electronic-documents-can-law-office-go-paperless/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6ncyrJFTk)

- Gottschalk, P. & Karlsen, J. (2009). Knowledge management in law firm business. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 16(3), 432-442.

- Higson, C. & Waltho, D. (2009). Valuing information as an asset. London: SAS. Retrieved from http://www.eurim.org.uk/activities/ig/voi/voi.php (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6ncyuKM2U)

- Hunter, L., Beaumont, P. & Lee, M. (2002). Knowledge management practice in Scottish law firms. Human Resource Management Journal, 12(2), 4-21.

- Jarvis, F. (2013). Information overload: big data threatens business model of even the elite law firms. Legal Week, 15(40), 13.

- Kabene, S.M., King, P. & Skaini, N. (2006). Knowledge management in law firms. Journal of Information Law and Technology, 1, 1-21.

- Khandelwal, V.K. & Gottschalk, P. (2003). A knowledge management survey of Australian law firms. Sydney, NSW: University of Western Sydney.

- Ladley, J. (2010). Making enterprise information management (EIM) work for business: a guide to understanding information as an asset. New York: Morgan Kaufmann.

- Lambe, P. (2003). What does KM mean for law firms? Green Chameleon. Retrieved from http://greenchameleon.com/thoughtpieces/kmlaw.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6ncyxIKEw)

- Laney, D. (2011). Infonomics: the economics of information and principles of information asset management. In Proceedings of the 2011 Chief Data Officer & Information Quality Symposium (pp. 590-603). [Powerpoint presentation]. Retrieved from http://mitiq.mit.edu/IQIS/Documents/CDOIQS_201177/Papers/05_01_7A-1_Laney.pdf. (Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6oERxWhem).

- McFadzean, E., Ezingeard, J. & Birchall, D. (2007). Perception of risk and the strategic impact of existing IT on information security strategy at board level. Online Information Review, 31(5), 622–660.

- Mezrani, L. (2012, September 6). Mind the knowledge gap. Lawyers Weekly. Retrieved from http://www.lawyersweekly.com.au/features/10689-Mind-the-knowledge-gap. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6nczN5Xyn.)

- Miles, M.B. & Huberman, A.M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. London: Sage Publications.

- Moore, L. (2013). The rise and rise of knowledge management. Sydney, NSW: The Law Society of New South Wales. Retrieved from http://www.lawsociety.com.au/ForSolictors/SmallPracticePortal/ BusinessDevelopment/articles/TheriseandriseofKnowledgeManagement/index.htm (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6nczOuSjq)

- Muir, L., Douglas, A. & Meehan, K. (2004). Strategic issues for law firms in the new millennium, Journal of Organisational Transformation & Social Change, 1(2), 179-191.

- Oliver, G. (2011). Organisational culture for information managers. Oxford: Chandos.

- Oppenheim, C., Stenson, J. & Wilson, R.M.S. (2001). The attributes of information as an asset. New Library World, 102(1170/1171), 458–463.

- Parsons, M. (2004). Effective knowledge management for law firms. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Porter, M.E. (1980). Competitive strategy. New York: The Free Press.

- Robertson, J. (2005). Information management: a key for creating business value. Retrieved from http://www.steptwo.com.au/papers/kmc_effectiveim/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6oA9Rq7WC)

- Schiuma, G. (2012). Managing knowledge for business performance improvement. Journal of Knowledge Management, 16(4), 515–522.

- Scholes, R. (1981). Language, narrative, and anti-narrative. In W. Mitchell (Ed.), On narrativity. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Segal-Horn, S. & Dean, A. (2011). The rise of super-elite law firms: towards global strategies. The Service Industries Journal, 31(2), 195-213.

- Shipman, A. (2002). Managing e-mail and e-commerce records. Records Management Journal, 12(23), 98–102.

- Strassmann, P.A. (1985). Information payoff: the transformation of work in the electronic age. New York: The Free Press.

- Strauss, A & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Sukumaran, S., Chandran, K. & Chandran, K. (2013), Knowledge management strategy using activity theory for a law firm. In Proceedings, 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management in Organizations: Social and Big Data Computing for Knowledge Management (pp. 521-553). Berlin: Springer Verlag.

- Swap, W., Leonard, D., Schields, M. & Abrams, L. (2001). Using mentoring and storytelling to transfer knowledge on the workplace. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 95–114.

- Swartz, N. (2007). Data management problems widespread. The Information Management Journal, 41(5), 28-30.

- Teece, D. J. (2000). Strategies for managing knowledge assets: the role of firm structure and industrial context. Long Range Planning, 33(1), 35-54.

- Thornton, M. (2016). The flexible cyborg: work-life balance in legal practice. Sydney Law Review, 38(1), 1-21.

- Tjaden, T. (2009). The 7 faces of legal knowledge management. Paper presented at LawTech Canada. Retrieved from www.legalresearchandwriting.ca/images/7faces.pdf. (Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6oAa8NOKw)

- Tulving E. (1972). Episodic and semantic memory. In E. Tulving and W. Donaldson, (Eds.). Organization of memory. (pp. 381-403). New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Widén, G. & Hansen, P. (2012). Managing collaborative information sharing: bridging research on information culture and collaborative information behaviour. Information Research, 17(4), paper 538. Retrieved from http://informationr.net/ir/17-4/paper538.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6o9neQrKD)

- Willis, A. & Fox, P. (2005). Corporate governance and management of information and records. Records Management Journal, 15(2), 86–97.

- Winston, A.M. (2014). Law firm knowledge management: a selected annotated bibliography. Law Library Journal, 106(2), 175-491.

- Young, S. & Thyil, V. (2008). A holistic model of corporate governance: a new research framework. Corporate Governance, 8(1), 94–108.

- Zeide, E. & Liebowitz, J. (2012). Knowledge management in law: a look at cultural resistance. Legal Information Management, 12(1), 34-8.