Implications of counter-attitudinal information exposure in further information-seeking and attitude change

Sangwon Lee

Introduction. Given that people rely heavily on their party affiliation to make their political decisions, an interesting dilemma occurs when people are exposed to counter-attitudinal information from the party they identify with. This paper examines how exposure to counter-attitudinal messages from the party an individual identifies with influence further online information seeking and attitude change.

Method. Using an adult sample (N=289), the study adopts an experimental design, measuring actual information seeking behaviour in time units through unobtrusive observation.

Analysis. Quantitative analysis was carried out on the data using SPSS.

Results. In terms of information seeking, neither attitude-party message consistency, nor partisanship strength, led to confirmation bias-seeking. In terms of attitude change, there was significant difference in attitude change between strong and weak partisans when they were exposed to the pro-attitudinal message.

Conclusions. Despite popular belief, even those with strong party identification do not blindly seek out information that confirms their own belief. The type of information exposure, rather than an individual’s strength of party affiliation, influences the further information seeking patterns of individuals. In addition, attitude change patterns showed some complexities depending on various conditions. This paper calls for more nuanced understanding of political information seeking behaviour and attitude change.

Introduction

Partisanship is known as a fundamental and lasting political predisposition (Campbell, Philip, Warren and Donald, 1960), which may shape policy opinions (Carsey and Layman, 2006) and perceptions (Bartels, 2000). Citizens often use party label as a useful shortcut regarding both how to vote and where to stand on political issues (Converse, 1975; Downs, 1957). Given that people rely heavily on their party affiliation to make their political decisions, cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957) would occur when people are exposed to counter-attitudinal political information from the party they identify with (from now on, referred to as the same party).

Although inconsistency between the political position of an issue and party affiliation is not uncommon in current politics (see Nicholson, 2012), little research has been conducted on that type of situation (except for Nicholson, 2012). Even though there is little disagreement that partisanship plays a critical role in shaping political attitude, people do not always make their political decisions solely based on party labels (Bullock, 2011; Lau and Redlawsk, 2001). Information-seeking literature suggests that people often seek additional information in order to reduce uncertainty (Case, Andrews, Johnson and Allard, 2005; Kuhlthau, 1993).

The current Internet environment, in particular, facilitates political information seeking by providing ample avenues for searches (Bennett and Iyenger, 2008; Shah, Cho, Eveland and Kwak, 2005). Nevertheless, we have a surprisingly poor understanding of how Internet users seek additional political information on the Internet when they encounter an unexpected stance of political information. The purpose of this paper is to examine how exposure to counter-attitudinal messages from the same party (for instance, Republican and pro-DreamAct) influence further online information seeking and attitude change.

Literature review—selective exposure theory

The concept of selective exposure refers to the tendency to craft an information environment that matches one’s beliefs. Selective exposure theory is one of the theories that is most frequently cited to illustrate the pattern of how people find political information. Its theoretical grounding was given by Festinger’s cognitive dissonance theory (1957). Cognitive dissonance theory suggests that inconsistency with prior beliefs or attitudes creates a negative psychological tension so that individuals are motivated to reduce dissonance by seeking out information to reinforce their attitude (Festinger, 1957). Research on selective exposure initially attracted researchers’ attention as selective exposure phenomenon is one of the classic testing grounds for dissonance theory (e.g., Adams, 1961; Feather, 1962, 1963; Mills, Aronson, and Robinson, 1959; Schramm and Carter, 1959).

Research on the topic increased in the 1960s, and then waned in subsequent periods following the conclusion from Freedman and Sears that there is little evidence for selective exposure (Freedman and Sears, 1965; Sears and Freedman, 1967). Weak evidence of selective exposure is largely due to lack of media choices in the past (McGuire, 1968). People encountered the same news channels with the same information, providing little opportunity to engage in selective exposure (McGuire, 1968; Stroud, 2008).

However, the advent of the Internet has exponentially expanded the available ways for people to seek information (Case, Johnson, Andrews, Allard, and Kelly, 2004) and created a more fragmented information environment (Bennett and Iyengar, 2008; Sunstein, 2001). People can now enjoy a wider range of media offerings, providing greater variability in the content of information (Bennett and Iyengar, 2008; Stroud, 2008). This dramatic change in the media environment led to a boom in selective exposure theory once again (Garrett, 2009a, 2009b; Knobloch-Westerwick and Meng, 2009; Mutz, 2002; Mutz and Martin, 2001; Stroud, 2007, 2008, 2010; Sunstein, 2001).

Several scholars have noted that the Internet may fragment users into ever more specific like-minded groups (e.g., Bennett and Iyengar, 2008; Mutz and Martin, 2001; Sunstein, 2001). In the age of digital media, with more chances for people to engage with various types of information, they are more likely to read, listen to, or view political information that supports their opinion, and they are less likely to engage with information that may challenge their position (Bennett and Iyengar, 2008; Mutz and Martin, 2001; Sunstein, 2001). Following this line of view, Bennett and Iyenger (2008) argued in favour of a new era of minimal effects, asserting that media users can easily avoid opposing views posted in online venues; thus, the Internet entails more potential than traditional media venues to magnify confirmation-bias exposure patterns.

However, this argument has recently been refuted by a number of scholars (Garrett, 2009a;; Garrett and Stroud, 2014; Jang, 2014; Kim, Hsu, and de Zuniga, 2013), who have pointed out that Internet users do not necessarily avoid attitude challenging opinions. In contrast to a face-to-face conversation context, where people usually want to avoid dissonant conversation (Mutz, 2002), in online settings participants often seek a variety of opinions to increase their knowledge about the issue (Garrett, 2009a; Stromer-Galley, 2003). In addition, if individuals expect that information would be beneficial to them, they will be less concerned with whether the message agrees with their previous beliefs (Knoblock-Westerwick and Johnson, 2014). In this case, the utility motivation may override confirmation bias.

Based on previous reviews, I expect that exposure to counter-attitudinal messages from the same party would bring about greater dissonance, which may result in engagement with more diverse information and a greater attitude change, compared to the pro-attitudinal message from the same party. This leads to two hypotheses on attitude-party message consistency.

Hypothesis 1: Individuals who were exposed to the counter-attitudinal message from the same party would spend more time on reading (a) counter-attitudinal and (b) neutral articles, and less time on (c) pro-attitudinal articles, than those who were exposed to the pro-attitudinal message from the same party.

Hypothesis 2: Individuals who were exposed to the counter-attitudinal message from the same party would be more likely to change their original attitude than those who were exposed to the pro-attitudinal message from the same party.

It was hypothesised above that individuals who were exposed to the counter-attitudinal message from the same party would spend more time on (a) counter-attitudinal articles and (b) neutral articles than those who were exposed to the pro-attitudinal message. Following hypothesis 1, it was assumed that exposure to counter-attitudinal articles makes users aware of the opposing rationale, thereby facilitating greater understanding for opposing views. The effect that exposure to contrasting views has on political tolerance has been supported by several studies (Mutz, 2002, 2002). This leads to the hypothesis on the effect of information seeking.

Hypothesis 3: The more time individuals spend reading counter-attitudinal articles, the more their attitudes shift.

The strength of an individual’s partisanship may also influence the exposure process. A number of researchers have pointed out that strong party affiliation leads partisans to be more likely to blindly adopt their preferred party’s positions (Bartels, 2000; Gaines et al., 2007). However, no research has been conducted on how partisan strength affects the way people seek information and form an attitude when they are exposed to counter-attitudinal political information from the same party.

The concept of attitude certainty may provide a key to addressing this problem. Attitude certainty refers to the extent to which one thinks that his/her views are correct (Tormala, Clarkson, and Petty, 2006). Attitude certainty has been considered an important factor that influences the selective exposure pattern (Knoblock-Westerwick and Meng, 2009; Stroud, 2007). Kuhlthau (1993) pointed out that uncertainty, caused by lack of understanding, motivates individuals to engage in information seeking behaviour. In the political realm, most studies support the idea that greater attitude certainty leads to additional seeking of like-minded opinions (Knoblock-Westerwick and Meng, 2009; Stroud 2007). Specifically, Knoblock-Westerwick and Meng (2009) argued that when individuals are not certain about their attitude they are more highly motivated to understand the counterarguments than individuals with greater attitude certainty.

Applying the attitude certainty concept into this study, it can be assumed that if strong partisans are exposed to the pro-attitudinal message, their attitude certainty will be stronger than the certainty of weak partisans. This then results in people searching for more attitude-consistent information, thereby decreasing the likelihood of them changing their opinions. However, when counter-attitude messages are given, even strong partisans will not show a high certainty toward the issue, and this lack of certainty will be even more pronounced for weak partisans. As attitude certainty is not expected to have a linear partisanship effect on the counter-attitudinal message, rather than proposing hypotheses, the following research questions were raised about people’s changes in attitude certainty after they are exposed to the counter-attitudinal message. When exposed to the pro-attitudinal message:

Hypothesis 4: Strong partisans spend less time on (a) counter-attitudinal and (b) neutral articles and more time on (c) pro-attitudinal articles than weak partisans do.

Hypothesis 5: Strong partisans are less likely to change their original attitudes than are weak partisans.

When exposed to the counter-attitudinal message:

Research question 1: How much time do strong partisans spend on reading counter-attitudinal, neutral, and pro-attitudinal articles compared to weak partisans, when exposed to the counter-attitudinal message from the same party?

Research question 2: How do strong partisans change their attitude compared to weak partisans, when given the counter-attitudinal message from the same party?

Methods

Issue selection

One of the most critical points of this online experiment was how to naturally create a dissonant condition in which individuals are exposed to the counter-attitudinal message from the same party. To maintain the validity of the test, the participants should take the party position shown in their message as real. The DREAM Act, which is legislation that provides immigrants with a path to citizenship (see the Appendix A for more details), was chosen as the issue in this experiment and it is considered an adequate way to test the situation in which individuals receive counter-attitudinal information from the same party without realising that it is fake. Public opinion has not yet crystallised regarding the DREAM Act and the Democratic and Republican parties have taken identical positions on this issue (Druckman, Peterson, and Slothuus, 2013). This indicates that manipulating party positions in the DREAM Act issue would be more realistic in comparison to other traditional partisan issues.

Procedure

Prior to the experiment a mock-up page of Googlenews.com was created to maximise ecological validity, as online users in the United States get more political information from portal websites than they do from partisan sources (Purcell, Rainie, Mitchell, Rosenstiel, and Olmstead, 2010). Participants were then recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk (Mturk). Several researchers have criticised heavy reliance on samples drawn from American colleges (Buhrmester, Kwang, and Gosling, 2011; Druckman and Kam, 2010). Mturk has been gaining popularity as an alternative that provides samples more demographically diverse than typical American college and standard internet samples (Buhrmester, et al., 2011; Paolacci, Chandler, and Ipeirotis, 2010). Through Mturk, participants were informed that they would be participating in public opinion research.

After consenting to participate in the study, participants were told that they were to engage in a public opinion study on the issue of the DREAM Act. At the beginning of the experiment, participants were given basic information about the DREAM Act issue (see Appendix A for more details), and their attitudes toward the act were evaluated. Participants were then randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions: Republican/supports, Republican/opposes, Democrat/supports, or Democrat/opposes. Those who had inconsistent positions between the party and issue attitude, and those who were pure Independent (Independents with no Democrat or Republican leanings) were excluded from the analysis after the study.

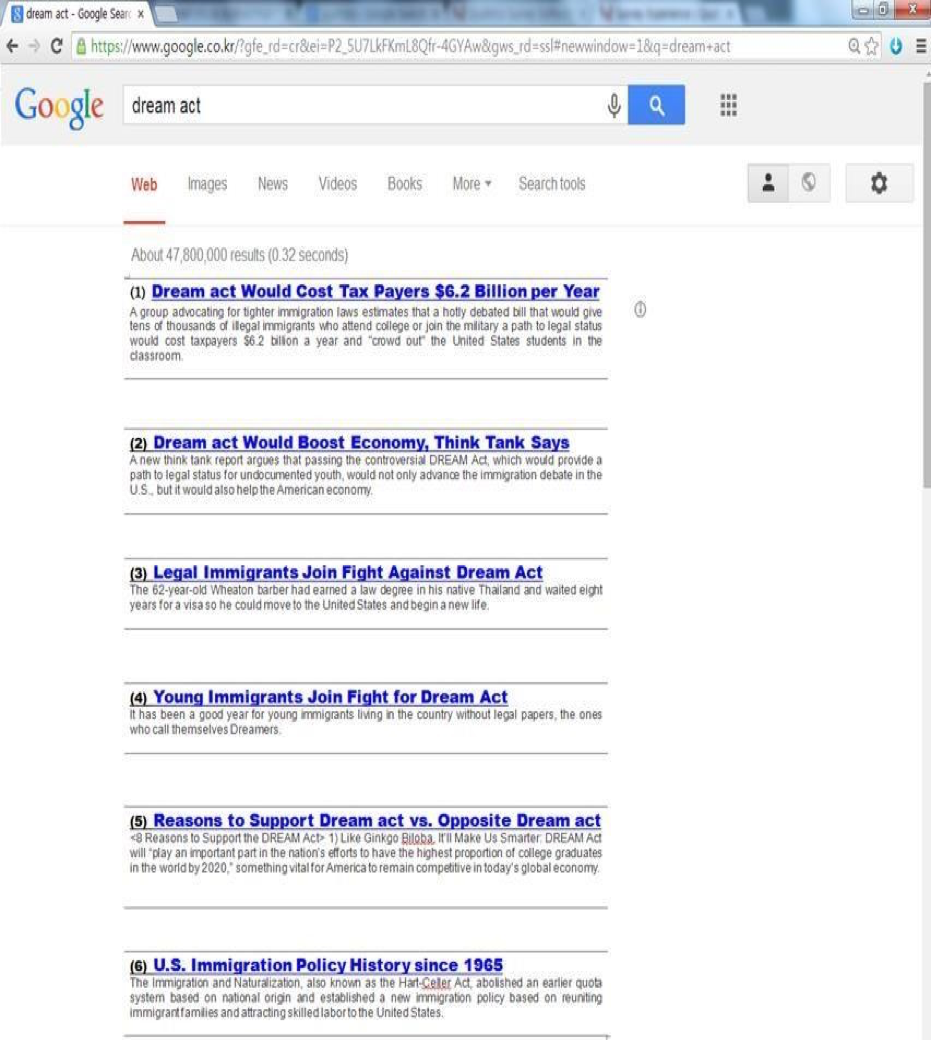

Participants were instructed to read the given opinion for one minute, they were then shown a mock-up page of Googlenews.com (see Appendix B for more details). Six titles related to the issue were shown on the mock-up page, two from each of three categories: pro-attitudinal articles, neutral articles, and counter-attitudinal articles. Each title presented a recognisable stance, so that the information in the article matched participants’ expectations (see Appendix B for more details). Participants were allowed to choose multiple articles to read and were given a total of three minutes to freely click the titles and read the various articles presented on the mock-up page. The difficulty and length of the articles was carefully checked to ensure consistency. The software recorded the viewing time for each argument selected. After three minutes, participants were asked again to indicate their attitudes on the issue (post-test). Demographic variables were collected at the end of the survey.

A total of 360 individuals participated in the online experiment, offering 360 responses. 54 cases were dropped because the subjects could not be identified as any party (i.e., indicated as pure Independents or other party in the partisanship question). Additionally, 17 cases were excluded because they neither support nor oppose the DREAM Act (pre-test attitude score being exactly 4). Of the remaining 289 participants, 193 participants were in support of the DREAM Act (pre-test attitude score being lower than 4, M = 2.49, SD = 0.90) and 96 participants were against the DREAM Act (pre-test score being higher than 4, M = 5.52, SD = 1.01). When divided by the message condition and partisanship strength, the latter group of 96 participants yielded a cell size less than 20 subjects. This therefore produced a final sample size of 193 for hypothesis testing. In terms of partisanship, 58% were Democrats and 42% were Republicans. Among the Democrats, 54% were strong Democrats and 46% were weak Democrats. Among the Republicans, 44 % were strong Republicans and 56% were weak Republicans. These results indicate that every cell is almost evenly distributed.

Independent variables

Message condition.

Dichotomous measures were used to capture attitudes towards the issue. Participants either received the pro- or the counter-attitudinal message from the same party. Pro-attitudinal message conditions were met if participants supported the DREAM Act and their party supported the DREAM Act. Counter-attitudinal message conditions were met if participants supported the DREAM Act, but their party opposed the DREAM Act.

Partisanship strength.

The conventional measure of party identification was used (e.g., Claggett, 1981). Participants were asked which party they most closely align themselves with: Democrat, Republican, Independent, or Other. If participants identified themselves as either Democrat or Republican, they were asked to identify themselves as strong Democrat (Republican) or weak Democrat (Republican). If they identified themselves as Independent, they were asked to identify themselves as leaning toward Democrat or leaning toward Republican. Those who identified themselves as strong Democrat or strong Republican were categorised as strong partisans. Those who identified themselves as weak Democrat or weak Republican and Independent but leaning toward Democrat or Independent but leaning toward Republican were all categorised as weak partisans. Independent leaners were regarded as partisans, as they tend to show similar vote choice and share policy opinions that are more aligned with the beliefs held by partisans (e.g., Lascher and Korey, 2011). Pure Independents were excluded from the analysis.

Dependent variables

Attitude change.

Attitude change means that a person’s evaluation is modified from one value to another and change is often assessed relative to the person’s initial attitude (Petty and Wegener, 1999). A four-item attitude scale was created to measure an individual’s attitude toward the DREAM Act issue. The scale consisted of seven-point semantic differential items (1: Strongly agree to 7: Strongly disagree) in response to a statement about the DREAM Act issue (e.g., Do you agree or disagree with the DREAM Act, which would provide undocumented immigrant youth a path to citizenship if they attend college or serve in the U.S military?). Reliability checks revealed that item 3 (Do you agree or disagree with maintaining all forms of public assistance, including education and health benefits, to all illegal or undocumented immigrants and their children?) lowered the internal consistency of the scale. After dropping the item, Cronbach's alpha indicated high reliability (α = 0.89 for pre-test, α = 0.92 for post-test). Attitude change was calculated by subtracting the post-test attitude score from the pre-test attitude score. The lower attitude score corresponded to pro- DREAM Act attitude, while the higher attitude score corresponded to counter-DREAM Act attitude; hence, a negative value of the attitude change (being the post-test score greater than the pre-test score) indicates that an individual has shifted their attitude towards the counter-DREAM Act position.

Time spent on reading articles.

In order to observe individuals’ information-seeking habits accurately, an approach was utilised that does not suffer from potential captive audience limitations by failing to provide enough choices for respondents (for more details, see Druckman, Fein, and Leeper, 2012). To accomplish this aim, participants were provided with an information search page designed in a style to resemble Google News page. The mock up page allowed participants to choose from six articles with different positions: pro-, con, and neutral (i.e., fact-checking news). All articles were minimally edited, although considerably shortened, to equalise length. The overview page (Appendix C) showed six news leads that each contained a headline, a news lead, and a hyperlink to access the actual article. The respondents selected articles by clicking on the hyperlinks and read as much of the content as they wished. They then returned to the overview page, selected other articles, and so forth, until the end of the reading period, which lasted a total of three minutes. Whenever a participant accessed or exited an article, a log of the activity was recorded to measure selective exposure times (for detailed measurement, see Knobloch and Meng, 2009). Time spent on counter-DREAM Act articles (in seconds) was calculated by summing up the amount of time spent on article 1 and article 3. In the same manner, time spent on pro-DREAM Act articles was calculated by summing up time spent on article 2 and article 4. Time spent on neutral articles was calculated from time spent on articles 5 and 6, to be used for further analysis.

Results

Participants clicked on 0.7 (SD = 0.7) pro-attitudinal articles, on 0.77 (SD = 0.71) counter-attitudinal articles, and on 0.61 (SD = 0.62) neutral articles. Bonferroni's post-hoc test revealed that there was no significant difference in the average number of articles clicked, F (2,192) = 2.64, p = 0.07. For exposure times, participants spent 20.87 seconds on average (SD = 28.08) on pro-attitudinal articles, 25.26 seconds (SD = 29.68) on counter-attitudinal articles, and 10.70 seconds on neutral articles. Time spent on counter-attitudinal articles and pro-attitudinal articles was significantly different from neutral articles, F (2, 192) = 12.73, p <0 .001. There was no significant difference between time spent on reading pro-attitudinal articles and counter-attitudinal articles (p = 0.60).

Attitude-party message consistency hypotheses

It was predicted that individuals who were exposed to the counter-attitudinal message from the same party would spend more time on (hypothesis 1a) counter-attitudinal and (hypothesis 1b) neutral position articles, and less time on (hypothesis 1c) pro-attitudinal articles than those who were exposed to the pro attitudinal message from the same party. An independent t-test was used to test the hypothesis. No significant difference was found for time spent on reading neutral position messages between the conditions, t (191) = 1.90, p = 0.06. There were no significant differences between the conditions in reading pro-attitudinal articles (t [191] = -0.27, p = 0.78), which suggests that those who were exposed to the counter-attitudinal message from the same party did not spend less time on reading pro-attitudinal articles (M = 21.37, SD = 28.02) than those exposed to the pro-attitudinal message from the same party (M = 20.27, SD = 28.29).

It is worth noting that, for counter-attitudinal articles, a significant difference was found between the conditions in the opposite of the hypothesised direction (t [191] = 2.22, p = 0.03). Individuals who were exposed to the pro-attitudinal message spent more time on counter-attitudinal articles (M = 30.32, SD = 32.12) than those who were exposed to the counter-attitudinal message (M = 20.92, SD = 26.81). Hence, the data were inconsistent with all the hypotheses in hypothesis 1.

It was predicted that individuals who were exposed to the counter-attitudinal message from the same party would be more likely to change their original attitude than those who were exposed to the pro-attitudinal message from the same party (hypothesis 2). The independent t-test result did not yield a significant difference between the conditions, t (191) = 0.04, p = 0.97. Individuals who were exposed to the counter-attitudinal message from the same party (M = -0.30, SD = 0.83) did not change their attitude more than those who were exposed to the pro-attitudinal message from the same party (M = -0.30, SD = 0.81). Hence, the data was inconsistent with hypothesis 2.

Information effect hypothesis

It was predicted that the more time individuals spend on reading counter-attitudinal articles, the more their attitudes would shift (hypothesis 3). Multiple regression analysis was used to test the effect of time spent on reading counter-attitudinal articles, whilst controlling the effect of time spent on reading pro-attitudinal or neutral position articles. The result was significant, F (3, 189) = 6.30, p < 0.001, adjusted R2= 0.08. The analysis showed that time spent on reading counter-attitudinal articles was a significant predictor of attitude change, β = -0.29, t = - 3.80, df = 189, p < 0.001, while time spent on reading pro-attitudinal (β = -0.02, t = 0.33, df = 189, p = 0.75), or neutral position articles (β = -0.11, t = - 1.52, df = 189, p = 0.13) was not. Thus, the data were consistent with hypothesis 3.

Partisanship strength hypotheses and research questions

When exposed to the pro-attitudinal message from the same party, it was predicted that strong partisans would spend less time on counter-attitudinal articles (hypothesis 4a) and neutral articles (hypothesis 4b), and more time on pro-attitudinal articles (hypothesis 4c) than weak partisans. An independent t-test was used to test the hypothesis. The result did not show significant difference between strong and weak partisans in reading counter-attitudinal articles (t [87] = 1.84, p= 0.06). No significant difference was found between strong and weak partisans in reading neutral articles (t [87] = -0.01, p = 0.99), or pro-attitudinal articles (t [87] = -0.71, p = 0.48). This suggests that strong partisans neither spend more time on reading neutral position articles (M = 7.55, SD= 17.25) nor less time on reading pro-attitudinal articles (M = 17.85, SD= 26.56) than weak partisans (M = 7.69, SD= 16.69 for neutral articles; M = 22.17, SD= 29.70 for counter-attitudinal articles). Hence, the data was inconsistent with all the hypotheses in hypothesis 4.

It was predicted that strong partisans would be less likely to change their original attitudes than weak partisans, when exposed to the pro-attitudinal message (hypothesis 5). The independent t-test result revealed a significant difference between strong and weak partisans, t (87) = 2.64, p = 0.01. Strong partisans (M = -0.05, SD = 0.56) changed their attitude significantly less than weak partisans did (M = -0.49, SD= 0.92). Effect size, measured by Cohen’s d, was 0.58 which indicates that partisanship has a moderate effect size. Hence, the data was consistent with the hypothesis.

How much time strong partisans would spend on reading counter-attitudinal, neutral, and pro-attitudinal articles, compared to weak partisans when exposed to the counter-attitudinal message from the same party cue (research question1), was investigated. The result did not yield significant difference between strong and weak partisans in reading any kind of article. When reading counter-attitudinal articles, strong partisans spent a little less time (M = 19.04, SD = 28.49) than weak partisans did (M = 23.20, SD = 24.73), but the difference was not significant, t (102) = -0.79, p = 0.43. When reading neutral articles, strong partisans spent a little less time (M = 11.49, SD= 21.41) than weak partisans did (M = 15.66, SD = 27.33), but the difference was not significant, t (102) = -0.87, p = 0.39. Lastly, on reading pro-attitudinal articles, strong partisans spent a little more time (M = 23.95, SD = 30.09) than weak partisans did (M = 18.24, SD = 25.25), but the difference was not significant, t (102) = 1.04, p = 0.30. We also investigated how strong partisans would change their attitude compared to weak partisans when given the counter-attitudinal message from the same party (research question2). The independent t-test results did not show significant difference between strong and weak partisans, (t [102] = 1.84, p = 0.07).

To summarise, the results for research questions 1 and 2 showed that partisanship had no significant effect on either information-seeking or attitude change when given the counter-attitudinal message.

Discussion

The results demonstrate somewhat complex, but noteworthy and interesting findings.

In terms of information-seeking behaviour, participants who were exposed to the pro-attitudinal message more often searched for counter-attitudinal articles than those who were exposed to the counter-attitudinal message. In addition, partisanship strength did not result in different information-seeking behaviour.

In terms of attitude change, the results were also mixed. There was no attitude change between pro-attitudinal and counter-attitudinal message conditions. However, there was significant difference in attitude change between strong and weak partisans when they were exposed to the pro-attitudinal message, but no significant difference in attitude change occurred when they were exposed to the counter-attitudinal message.

First, in terms of information-seeking behaviour, the findings may seem a little counter-intuitive. How can this finding be accounted for? Dominant information-behaviour research suggests that self-efficacy is highly related to avoidance behaviour (Johnson, 1997). In other words, a high self-efficacy level would lead to seeking counter-attitudinal information. It is possible that the participants who were exposed to the pro-attitudinal message would have felt relatively little dissonance derived from the given condition, which led them to seek out counter-attitudinal information in order to be better informed about the issue. As an individual is expected to be self-confident under this circumstance, utility motivation may have outweighed self-defensive motivation. In contrast, the participants who were exposed to the counter-attitudinal message may have felt psychological arousal due to the dissonance, which may have decreased their need or want to spend more time reading further counter-attitudinal information, compared to those who were exposed to the pro-attitudinal message.

Under this circumstance, an individual’s self-defensive motivation may have outweighed utility motivation. Furthermore, this pattern holds constant regardless of an individual’s strength of party identification. An individual’s strength of party identification did not significantly influence their information-seeking behaviour.

This finding supports Garrett’s criticism of previous findings, that merely giving opinion-reinforcing and opinion-challenging information without presenting multiple-option conditions could overestimate the tendency for opinion reinforcement (Garrett, 2009a). In addition, this finding is consistent with recent research showing that there is no evidence of individuals actively avoiding challenging opinions in an online sphere (e.g., Garrett and Stroud, 2014; Jang, 2014; Kim et al. 2013).

In terms of attitude change, the findings are complex, but intriguing. Party strength mattered, yet it functioned conditionally according to the types of message exposure. This finding shows that partisanship may not function in a uniform way and may not be a panacea for explaining an individual’s political attitude formation. Attitude certainty was covered to address this issue. As attitude certainty increases, people’s attitudes become more resistant to substantial attack (Tormala et al., 2006). In this study, due to the lack of attitude certainty, participants who were exposed to the counter-attitudinal message by the same party would have been more vulnerable to maintaining their position, compared to those who were exposed to the pro-attitudinal message by the same party. This interpretation is compatible with other research linking a high certainty to greater attitude – behaviour correspondence (Fazio and Zanna, 1978; Tormala and Petty, 2004), greater attitude – choice consistency (Bizer, Tormala, Rucker, and Petty, 2006), and greater resistance to persuasion (Bassili, 1996; Tormala and Petty, 2002). However, as the concept of attitude certainty combined with partisanship has not been extensively covered within a political realm, further research on this issue would be necessary to shine more light on the dilemma that occurs when party label and value do not match.

Limitations

Although this research has discovered some meaningful findings, it is not without limitation. Firstly, this study only analysed the responses of people who supported the DREAM Act, ruling out people who opposed the DREAM Act, due to the lack of sample size when the participant groups were divided by each of the message conditions and by partisanship strength. As the samples for those who opposed the DREAM Act were dropped, much of the data could not be utilised. Overall, when the sample was winnowed down to those who fit the design, the sample size shrank which may have contributed to many of the null findings. Secondly, even though the tracking-time method made it possible to measure how much time the participants actually spent on reading each of the articles, the findings are limited by the inability to determine how thoroughly the participants read the articles. Although the participants were informed that they would be asked about the articles they read, motivating their sincere information-seeking and article reading behaviour remained a challenge. It is possible that some participants either did not pay attention to the articles, or they simply clicked on the article and spent time on the site, without reading the article at all. Lastly, this study tested selective exposure and information seeking behaviour with a single issue, making it difficult to draw generalisable conclusions. The issue characteristic may play a role in a selective exposure phenomenon. Different issues may prompt participants to have different motivation goals as they engage in information-seeking activities (for reviews, see Kim, 2009; Kunda, 1990). The topic’s unique features, unsolidified, bi-partisan, and of historical interest in the U.S, may have influenced the outcome of this study’s failure to find confirmation-bias seeking in any of the conditions. Given these issue characteristics, it is impossible to rule out the possibility that people may have searched for more counter-attitudinal articles in order to be more informed about the issue (for more details on the discussion of accuracy goals, see Kunda, 1990).

Conclusion

This study investigated how the type of information exposure influences further online information seeking and attitude change. By measuring actual exposure in time units using unobtrusive observation, instead of relying on self-reports of information seeking, this study suggests some noteworthy findings:

- Despite popular belief, even those with strong party identification do not blindly seek out information that confirm their own beliefs (i.e., confirmation-bias).

- The type of information exposure (i.e., pro- vs counter-attitudinal), rather than an individual’s strength of party affiliation, influences the further information seeking patterns of individuals.

- Both the type of information exposure and an individual’s strength of party affiliation influence their policy issue attitudes.

These findings call for a more nuanced understanding of political information seeking behaviour and attitude change. Importantly, findings should be cautiously interpreted within a set of aforementioned limitations that generate opportunities for further research to build upon this seminal study.

Keeping the aforementioned limitations of this study in mind, several suggestions can be made for future research. First, researchers should strive to increase participants’ attention to reading materials (e.g., message treatment and information pieces). Although time-tracking was incorporated to ensure that participants stay on the page and spend enough time to read, it is not without concern because the study was an online experiment and it is hard to know what participants were doing during the reading time. Future studies may consider conducting a lab study instead, in order to combat this difficulty. Secondly, future research can improve external validity of the findings by examining the proposed relationships using a variety of political issues. Replications of this experiment across different issues are encouraged to examine the robustness of effects across contexts. In addition, future research should examine how, and to what extent, the findings vary with varying degrees of media and political systems. Thirdly, follow-up studies should explore potential activating mechanisms (termed by Wilson, 1999) for seeking additional information, other than partisanship and attitude certainty. As suggested by information-behaviour models, non-political variables can also influence an individual’s information searching behaviour (e.g., Case et al., 2005; Johnson, 1997; Wilson, 1999). Lastly, but not least, the sample size should be larger to draw conclusions with more confidence.

Acknowledgement

I would like to offer special thanks to Dr. Daniel Bergan. Advice given by him has been a great help in developing this research.

About the author

Sangwon Lee is a doctoral student in the Department of Communication Arts, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 821 University Ave, Vilas Room 6067, Madison, WI 53706, USA. He earned M.A. degree in Communication from Michigan State University. His research interest lies in the intersection of political communication and social media, more specifically, how social media changes the way citizens engage in politics. He can be contacted at slee572@wisc.edu

References

- Adams, J. S. (1961). Reduction of cognitive dissonance by seeking consonant information. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 62(1), 74-78.

- Atkin, C. K. (1971). How imbalanced campaign coverage affects audience exposure patterns. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 48(2), 235-244.

- Baldassarri, D. & Bearman, P. (2007). Dynamics of political polarization. American Sociological Review, 72(5), 784-811.

- Bartels, L. M. (2000). Partisanship and voting behavior, 1952-1996. American Journal of Political Science, 44(1), 35-50.

- Bassili, J. N. (1996). Meta-judgmental versus operative indexes of psychological attributes: the case of measures of attitude strength. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(7), 637-653.

- Bennett, W. L. & Iyengar, S. (2008). A new era of minimal effects? The changing foundations of political communication. Journal of Communication, 58(4), 707-731.

- Bizer, G. Y., Tormala, Z. L., Rucker, D. D. and Petty, R. E. (2006). Memory-based versus online processing: implications for attitude strength. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(5), 646–653.

- Brady, H. E. & Sniderman, P. M. (1985). Attitude attribution: a group basis for political reasoning. American Political Science Review, 79(4), 1061-1078.

- Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T. & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon's Mechanical Turk a new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 3-5.

- Bullock, J. G. (2011). Elite influence on public opinion in an informed electorate. American Political Science Review, 105(3), 496–515.

- Campbell, A., Philip, E., Warren, E. M. & Donald, E. S. (1960). The American voter. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Carsey, T. M. & Layman, G. C. (2006). Changing sides or changing minds? Party identification and policy preferences in the American electorate. American Journal of Political Science, 50(2), 464-477.

- Case, D. O., Andrews, J. E., Johnson, J. D. & Allard, S. L. (2005). Avoiding versus seeking: the relationship of information seeking to avoidance, blunting, coping, dissonance, and related concepts. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 93(3), 353-362.

- Case, D. O., Johnson, J. D., Andrews, J. E., Allard, S. L. & Kelly, K. M. (2004). From two‐step flow to the internet: the changing array of sources for genetics information seeking. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 55(8), 660-669.

- Chaffee, S. H. & McLeod, J. M. (1973). Individual vs. social predictors of information seeking. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 50(2), 237-245.

- Chaffee, S. H., Saphir, M. N., Graf, J., Sandvig, C. & Hanh, K. S. (2001). Attention to counter-attitudinal messages in a state election campaign. Political Communication, 18(3), 247-272.

- Claggett, W. (1981). Partisan acquisition versus partisan intensity: life-cycle, generation, and period effects, 1952-1976. American Journal of Political Science, 25(2), 193-214.

- Converse, P. (1975). Public opinion and voting behavior. In F. I. Greenstein and N. W. Polsby (Eds.), Handbook of political science (Vol. 4, pp. 75-169). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of political action in a democracy. The Journal of Political Economy, 65(2), 135-150.

- Druckman, J. N. & Kam, C. D. (2010). Students as experimental participants: a defence of the “narrow data base”. In J. N. Druckman, D. P. Green, J. H. Kuklinski and A. Lupia (Eds.), Handbook of experimental political science (pp. 41–57). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Druckman, J. N., Fein, J. & Leeper, T. J. (2012). A source of bias in public opinion stability. American Political Science Review, 106(2), 430-454.

- Druckman, J. N., Peterson, E. & Slothuus, R. (2013). How elite partisan polarization affects public opinion formation. American Political Science Review, 107(1), 57-79.

- Erlich, D., Guttman, I., Schönbach, P. & Mills, J. (1957). Postdecision exposure to relevant information. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 54(1), 98–102.

- Fazio, R. H. & Zanna, M. P. (1978). Attitudinal qualities relating to the strength of the attitude-behaviour relationship. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 14(4), 398–408.

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Fiorina, M. P., Abrams, S. J. & Pope, J. C. (2005). Culture wars? The myth of polarized America. New York, NY Pearson Longman.

- Fiorina, M. P., Abrams, S. J. & Pope, J. C (2008). Political polarization in the American public. Annual Review of Political Science, 11, 563-588.

- Feather, N. T. (1962). Cigarette smoking and lung cancer: a study of cognitive dissonance. Australian Journal of Psychology, 14(1), 55-64.

- Feather, N. T. (1963). Cognitive dissonance, sensitivity, and evaluation. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66(2), 157-163.

- Freedman, J. L. & Sears, D. O. (1965). Warning, distraction, and resistance to influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1(3), 262-266.

- Gaines, B. J., Kuklinski, J. H., Quirk, P. J., Peyton, B. & Verkuilen, J. (2007). Same facts, different interpretations: partisan motivation and opinion on Iraq. Journal of Politics, 69(4), 957-974.

- Garrett, R. K. (2009a). Politically motivated reinforcement seeking: reframing the selective exposure debate. Journal of Communication, 59(4), 676-699.

- Garrett, R. K. (2009b). Echo chambers online?: politically motivated selective exposure among Internet news users. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 14(2), 265-285.

- Garrett, R. K. & Stroud, N. J. (2014). Partisan paths to exposure diversity: differences in pro and counter attitudinal news consumption. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 680-701.

- Holbert, R. L., Garrett, R. K. & Gleason, L. S. (2010). A new era of minimal effects? A response to Bennett and Iyengar. Journal of Communication, 60(1), 15-34.

- Iyengar, S. & Hahn, K. S. (2009). Red media, blue media: evidence of ideological selectivity in media use. Journal of Communication, 59(1), 19-39.

- Jang, S. M. (2014). Challenges to selective exposure: selective seeking and avoidance in a multitasking media environment. Mass Communication and Society, 17(5), 665-688.

- Johnson, J. D. (1997). Cancer-related information seeking. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

- Jonas, E., Schulz-Hardt, S., Frey, D. & Thelen, N. (2001). Confirmation bias in sequential information search after preliminary decisions: an expansion of dissonance theoretical research on selective exposure to information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(4), 557–571.

- Kuhlthau, C. C. (1993). A principle of uncertainty for information seeking. Journal of Documentation, 49(4), 339-355.

- Kim, Y. M. (2009). Issue publics in the new information environment selectivity, domain specificity, and extremity. Communication Research, 36(2), 254-284.

- Kim, Y., Hsu, S. H. & de Zuniga, H. G. (2013). Influence of social media use on discussion network heterogeneity and civic engagement: the moderating role of personality traits. Journal of Communication, 63(3), 498-516.

- Knobloch-Westerwick, S. & Johnson, B. K. (2014). Selective exposure for better or worse: its mediating role for online news' impact on political participation. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 19(2), 184-196.

- Knobloch-Westerwick, S. & Kleinman, S. B. (2012). Preelection selective exposure confirmation bias versus informational utility. Communication Research, 39(2), 170-193.

- Knobloch-Westerwick, S. & Meng, J. (2009). Looking the other way selective exposure to pro-attitudinal and counterattitudinal political information. Communication Research, 36(3), 426-448.

- Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480-498.

- Lascher, E. L. & Korey, J. L. (2011). The myth of the independent voter, California style. California Journal of Politics and Policy, 3(1), 1-19.

- Lau, R. R. & Redlawsk, D. P. (2001). Advantages and disadvantages of cognitive heuristics in political decision making. American Journal of Political Science, 45(4), 951-971.

- Lazarsfeld, P. F., Berelson, B. and Gaudet, H. (1944). The people’s choice: how the voter makes up his mind in a presidential election. New York, NY: William Morrow.

- Lodge, M., Steenbergen, M. R. & Brau, S. (1995). The responsive voter: campaign information and the dynamics of candidate evaluation. American Political Science Review, 89(2), 309-326.

- McGuire, W. J. (1968). Selective exposure: a summing up. In R. Abelson, E. Aronson, W. J. McGuire, T. M. Newcomb, M. J. Rosenberg and P. H. Tannenbaum (Eds.), Theories of cognitive consistency: a sourcebook (pp. 788–796). Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

- Mills, J. (1965). Avoidance of dissonant information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2(4), 589-593.

- Mills, J., Aronson, E. & Robinson, H. (1959). Selectivity in exposure to information. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 59(2), 250-253.

- Mutz, D. C. (2002). Cross-cutting social networks: testing democratic theory in practice. American Political Science Review, 96(1), 111-126.

- Mutz, D. C., & Martin, P. S. (2001). Facilitating communication across lines of political difference: the role of mass media. American Political Science Review, 95(1), 97-114.

- Nicholson, S. P. (2012). Polarizing cues. American Journal of Political Science, 56(1), 52-66.

- Paolacci, G., Chandler, J. & Ipeirotis, P. G. (2010). Running experiments on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Judgment and Decision Making, 5(5), 411-419.

- Petty, R. E. & Cacioppo, J. T. (1981). Issue involvement as a moderator of the effects on attitude of advertising content and context. Advances in Consumer Research, 8, 20-24.

- Petty, R.E. & Wegener, D.T. (1999). The elaboration likelihood model: current status and controversies. In S. Chalken and Y. Trope, (Eds.). Dual process theories in social psychology (pp. 41-72). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Prior, M. (2009). Improving media effects research through better measurement of news exposure. The Journal of Politics, 71(3), 893-908.

- Purcell, K., Rainie, L., Mitchell, A., Rosenstiel, T. & Olmstead, K. (2010). Understanding the participatory news consumer: how Internet and cell phone users have turned news into a social experience. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

- Rahn,W. M. (1993). The role of partisan stereotypes in information processing about political candidates. American Journal of Political Science, 37(2), 472–496.

- Redlawsk, D. P. (2002). Hot cognition or cool consideration? Testing the effects of motivated reasoning on political decision making. The Journal of Politics, 64(4), 1021-1044.

- Schramm, W. & Carter, R. F. (1959). The effectiveness of a political telethon. Public Opinion Quarterly, 23(1), 121-127.

- Sears, D. O. & Freedman, J. L. (1967). Selective exposure to information: a critical review. Public Opinion Quarterly, 31(1), 194-213.

- Shah, D. V., Cho, J., Eveland, W. P. & Kwak, N. (2005). Information and expression in a digital age modeling Internet effects on civic participation. Communication Research, 32(5), 531-565.

- Stromer-Galley, J. (2003). Diversity of political conversation on the Internet. Users’ perspectives. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 8(3). Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2003.tb00215.x/full (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6slWQOjZ2)

- Stroud, N. J. (2007). Media effects, selective exposure, and Fahrenheit 9/11. Political Communication, 24(4), 415–432.

- Stroud, N. J. (2008). Media use and political predispositions: revisiting the concept of selective exposure. Political Behavior, 30(3), 341-366.

- Stroud, N. J. (2010). Polarization and partisan selective exposure. Journal of Communication, 60(3), 556-576.

- Sunstein, C. R. (2001). Republic.com. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Taber, C. S. & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 755-769.

- Tormala, Z. L., Clarkson, J. J. & Petty, R. E. (2006). Resisting persuasion by the skin of one's teeth: the hidden success of resisted persuasive messages. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(3), 423-435.

- Tormala, Z. L. & Petty, R. E. (2002). What doesn’t kill me makes me stronger: the effects of resisting persuasion on attitude certainty. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 83(6), 1298–1313.

- Tormala, Z. L. & Petty, R. E. (2004). Resistance to persuasion and attitude certainty: the moderating role of elaboration. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(11), 1446–1457.

- Wilson, T.D. (1999). Models in information behaviour research. Journal of Documentation, 55(3), 249-270. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/tdw/publ/papers/1999JDoc.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6slZth8gA)