The use of digital image collections and social media amongst Australian historical societies

Courtney Ruge and Tom Denison.

Introduction. We report the findings of a research investigating the use of social media in conjunction with digital image collections, by Australian cultural institutions, with a focus on the results relating to historical societies. The theory of technology affordances was applied to better understand Australian cultural institutions’ use of social media in relation to digital image collections.

Method. Data collection was conducted in two phases: seventy Websites maintained by mainstream institutions and community archives were examined and their features mapped; and interviews were conducted with staff and volunteers with responsibility for social media in a range of cultural institutions.

Analysis. Qualitative analysis was carried out on the results of the interviews and the data then analysed to identify a series of affordances in relation to the cultural institutions’ use of social media.

Results. The project identified nine affordances associated with the stated aims and use of social media, and issues that impact on the realisation of those affordances.

Conclusion. The findings from the Australian historical societies are highlighted, demonstrating that there is little consistency in their attitudes towards digital image collections and use of social media, and that many struggle to realise the potential benefits associated with utilising these platforms.

Introduction

Since the 1990s, projects dedicated to digitising collections and providing online access to digital assets have been common within the cultural sector. Many institutions such as national and state libraries, galleries, archives, and museums, have made significant digital collections available online, through their Websites or social media platforms with image-sharing functionality. Social media platforms are often used to support digital image collections through promotion, enhancing audience engagement, encouraging the co-creation of content, facilitating a two-way dialogue with users, and fostering other forms of participation and collaboration. Community archives have made less progress in this space, making less extensive use of social media, and with relatively few examples of digital collections available for viewing on their Websites.

This paper discusses the findings of research into the use of social media in conjunction with digital image collections by Australian cultural institutions, with an emphasis on highlighting the challenges and opportunities provided by such technologies for historical societies, a particular type of community archive. The research explores which social media platforms are used by Australian cultural institutions; how social media is used by these institutions in relation to digital image collections; the ways in which social media platforms are used; and the purpose behind their use. At the outset of the research, an assumption was made by the authors that a desire to digitise collections and share them with audiences would exist uniformly amongst Australian cultural institutions, yet the results of the study were found to contradict this assumption.

The project has drawn upon an adaptation of Gibson’s (1979) theory of affordances as a basis for explaining the many-to-many relationship that exists between cultural institutions and users when they interact through social media platforms. The article begins by providing the context and rationale for the project, followed by an introduction to the theory of affordances, and an outline of the project’s methodology and key research questions. The discussion draws upon examples brought to light during interviews with those working in the area in order to summarise current trends. It also highlights the opportunities and challenges faced by historical societies in providing access to digital image collections through social media. The risks of failing to adapt to changing user expectations and contemporary information-sharing practices are discussed.

Background

Digital image collections

In the past two decades, cultural institutions have moved towards the increased digitisation of their collections, converting analogue materials to digital formats by scanning, photographing, or representing them through 3D models. Many cultural institutions now host digital image galleries on their official Websites. A survey of cultural institution Websites undertaken for this project identified three approaches to digital image collections:

- bespoke digital image collections,

- social media photostreams, and

- online collaborative channels.

Bespoke digital image collections are online databases accessible through an organization’s Website, usually in the form of an online image gallery that users may browse or search. Such collections are usually presented as a set of thumbnail images, whereby the user may select a thumbnail to retrieve a higher resolution version and accompanying information. Bespoke digital image collections can be expensive to design, implement, and maintain, as advanced expertise in database management and Web publishing is required.

Social media photostreams are image collections powered by social media platforms that incorporate image-sharing functionality, for example, Facebook, Flickr, Instagram, and Pinterest. These platforms represent alternatives to dedicated repositories of digital images published on standalone Websites (Terras, 2010). Social media photostreams are a cheap, user-friendly alternative to bespoke digital image collections, allowing the creation of makeshift online image galleries free of charge, albeit with the trade-off of lower resolution images. These platforms are well-suited to enabling cultural institutions to share their collections with online audiences, with some allowing users to curate collections of favourites or even contribute their own images.

Online collaborative channels, essentially third party platforms through which cultural institutions may publish digital image collections, have recently emerged within the cultural sector. The Google Cultural Institute is a leading international example, whereby institutions are invited to curate online exhibitions and virtual tours. In the Australian context, examples of online collaborative channels include Victorian Collections and Culture Victoria, and Trove: Australia in Pictures Group on Flickr. Victorian Collections is an online service designed for small heritage organizations that provides a free Web-based collection management system, developed by Museum Victoria in partnership with Museums Australia (Victoria). Culture Victoria is the sister site of Victorian Collections, whereby institutions may curate stories containing information about the objects held in collections. Trove: Australia in Pictures Group is a collaborative group in Flickr, whereby users can contribute images that are representative of Australian culture. These images are also retrievable through the National Library of Australia’s search service, Trove.

Types of cultural institutions

Mainstream cultural institutions include state and national libraries, galleries, museums, and archives. In the last few decades, mainstream cultural institutions have moved away from a one-to-many model of information transmission towards a more inclusive, many-to-many model that places greater value on encouraging user perspectives and engagement. In libraries, this is evident in the shift away from their former cathedral-like presence (Horava 2010). In museums, this is reflected by how the socio-constructivist approach is currently favoured rather than the traditional models of education, with an emphasis on user learning and the subject rather than the object (Russo, 2011)

Community archives have been defined by Stevens, Flinn and Shepherd (2010, p. 59) as ‘collections of material gathered primarily by members of a given community and over whose use community members exercise some level of control’. Flinn (2010) observes that community archives are usually initiated by the particular community documented in the archives. These archives are driven by a desire to tell a story about the community documented, and often incorporate grassroots activity such as collection development and acquisitions. Community archives can typically be categorised as third sector organizations that are driven by community needs and a philanthropic interest in contributing to the community through preservation and sharing of information rather than for the purpose of generating profit. As such, they are often subject to the challenges that most third sector organizations tend to grapple with, including limited access to resources such as funding, expertise, and a reliance on volunteers (Denison and Johanson, 2007)

This article focuses on historical societies, as a particular form of community archive. Although not all historical societies maintain archival collections, this study is concerned solely with those that do. The mission of historical societies is usually to preserve and promote the history and significance of the heritage of the local jurisdiction that they document. As such, these represent one type of a community archive, typically associated with a particular place, space, and time. Some hold objects and artefacts in addition to records, thereby representing amateur museums. Some are housed within heritage buildings such as historic homesteads, in which artefacts are displayed to immerse visitors in the historical period they represent, while many are based in public libraries.

Social media use by cultural institutions

The benefits of social media for commercial organizations are widely understood (Kaplan and Haenlein, 2010). Cultural institutions have recognised the potential that social media and Web 2.0 plays in fostering user engagement with institutional events and collections, two-way communication with audiences, in addition to audience broadening (Bakhshi and Throsby, 2012). The Smithsonian Institution and the Library of Congress were early adopters of social media and are among those institutions that are leading the cultural sector internationally in this space (Springer et al., 2008; Xie and Stevenson, 2014). Despite this recognition, there are few guidelines advising on best practice to aid cultural institutions in their use of social media, and few scholarly articles have been dedicated to examining how social media is used alongside digital image collections. Articles exploring digital collections hosted by community-driven archives are even less common. There are many examples of large cultural institutions using social media to great effect, however, a report from the Australian Centre for Broadband Innovation, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, and the Smart Services CRC (Mansfield, Winter, Griffith, Dockerty and Brown, 2014) warns that cultural institutions must continue to develop strategies to make effective use of social media in order to remain relevant to audiences, including observing the lessons that can be learned from amateur collections. For example, Terras (2010) discusses online image collections created by ‘amateurs’ which are often based on novel subject matter such as comic books and vintage sewing patterns, noting that they tend to have substantial user communities of interest around them.

The emergence and widespread uptake of Web 2.0 and social media tools is linked to do-it-yourself culture and is particularly reflected in platforms such as YouTube, Tumblr, and Pinterest (Gibbons, 2014; Tanenbaum, Williams, Desjardins, and Tanenbaum, 2013). Social media technology is based on a many-to-many communication model that is much more interactive, democratic, and participatory in comparison with traditional modes of information transmission (Russo, Watkins, Kelly and Chan, 2008). Within that context, a number of scholarly articles about cultural institutions’ use of social media suggest that such technologies have the potential to expand audiences, increase access to digital collections and information about services, and to facilitate audience engagement with collections (Cho, 2013; Pett, 2012; Phillips, 2015).

Affordance theory and social media

The theory of affordances provides a useful lens through which the potential and effectiveness of social media used in conjunction with digital image collections can be evaluated. Originating within the field of ecological psychology with Gibson’s (1979) attempts to develop a new understanding of human perception, the theory of affordances describes a networked relationship between an actor, an object, and the environment. According to Gibson, when an actor encounters an object for the first time, the actor perceives the object in terms of the possibilities for action that it affords in the pursuit of fulfilling a specific goal or need, in addition to the constraints (i.e., restrictions or challenges) it may bring to the actor’s pursuit of that goal or need when the object is put to use.

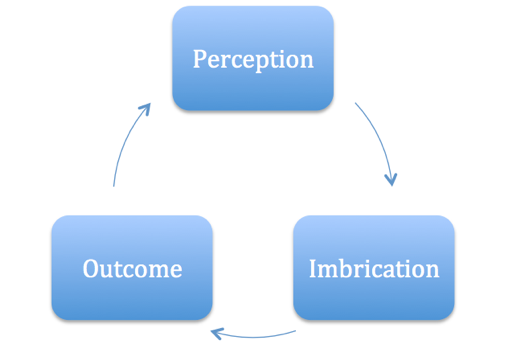

The theory of affordances has been used across various academic disciplines that differ somewhat from Gibson’s original theory (Majchrzak, Faraj, Kane, and Azad, 2013). The theory has been adapted by scholars within the fields of informatics and technology, for example, Gaver (1991), while Leonardi (2008) has applied the theory to organizational contexts. Leonardi suggests that the implementation of technologies based on the perception of affordances leads to the development of new goals and abilities on behalf of actors, followed by the perception of new affordances that, in turn, lead to new patterns of implementation or ‘imbrications’.

Figure 1 illustrates the cycle of affordances that takes place. First, an actor perceives an object in terms of its possibilities for action or constraints in relation to achieving a particular goal or fulfilling a need. The actor may then implement the object in a certain manner, arrangement, or pattern, constituting Leonardi’s (2008) notion of an imbrication. Based on this imbrication, the actor will perceive new affordances and imbricate the object in new ways, thus the cycle repeats. In this way, an affordance can be understood as a possibility for action that is based on a relationship between users and a technology object.

Majchrzak et al. (2013) argue that the theory is a useful and necessary lens for examining social media, given that it ‘avoids the separation between user and technology artefact’ (p. 50). They identified four affordances relevant to the user experience: metavoicing, triggered attending, network informed associating, and generative role-taking. Metavoicing refers to users’ ability to be able to interact with a piece of information by tagging, liking, or commenting on content. Triggered attending refers the ability to selectively participate in online discussions, by creating alerts. Network-informed associating refers to the ability to make new connections based on network relations, such as friending other users based on their connection to current friends. Generative role-taking refers to participation in new conversations as a result of participating in social media spaces.

Bakhshi and Throsby (2012) applied the theory in the context of cultural institutions’ use of social media, identifying three affordances: audience broadening, audience deepening, and audience diversifying. Audience broadening refers to ‘capturing a larger share of the population already known to be audiences’, whilst audience deepening involves ‘increasing and/or intensifying the engagement of audiences’, and audience diversifying incorporates ‘attracting new groups of consumers that do not currently attend’ (p. 209).

The merit of the theory of affordances lies in its holistic consideration of all aspects that comprise a relationship between objects and actors. In the context of examining cultural institutions’ use of social media alongside digital image collections, the theory of affordances considers social media platforms as a central node in a networked relationship between users and cultural institutions. This theoretical approach allows the identification of the potential strengths of social media and how the use of social media might contribute to fulfilling particular organizational goals.

Methods

The identification of specific affordances and how they are exploited in practice can vary depending on the stakeholder group being studied. The emphasis of this study was on whether the use of social media was meeting organizational goals, rather than the needs of the end users. Consequently, the study aimed to answer the following key research questions:

- What social media platforms are currently being used by Australian cultural institutions?

- How is social media being used in relation to digital image collections?

- How are specific social media platforms being used and for what purpose?

- What outcomes have cultural institutions experienced as a result of having a social media presence?

- Are any new social media trends taking place within the Australian cultural heritage sector?

Data collection was conducted throughout 2015 and early 2016. It included two phases: a Website survey, interviews with staff and volunteers with responsibility for social media in a range of cultural institutions, and a draft mapping of affordances. In the first phase, the Websites of a sample of mainstream institutions and community archives were viewed to observe current trends in social media use in conjunction with digital image collections. A total of seventy Websites were examined, including nine libraries, twelve archives, eight galleries, ninteen museums, and twenty-two community organizations, of which eleven were historical societies. Of the community archives considered, the majority were historical societies. In the second phase, interviews were conducted with staff and volunteers, drawn from eleven organizations, including two archives, three museums, one community organization and five local history societies. The interviews focused on social media practices in relation to digital image collections in order to gain insight into social media goals and challenges (i.e. affordances and constraints). The next step involved analysing the results from the previous two phases in order to compile the taxonomy of affordances. In this phase, the content of the interviews and any supporting documentation was analysed to identify comments that related the goals of using social media to the features used and outcomes achieved. These comments were assigned codes which were gradually refined using an iterative process in an attempt to identify a core set of affordances. These codes were then mapped to specific social media platforms and organizational goals.

All interviewees were asked whether it was permissible to identify themselves and their institution by name in the published output of the research. An ethics clearance was obtained from the Monash University Research Office and all participants were provided with a copy of the ethics statement.

Findings

The study found that Facebook is used by almost all organizations surveyed, with Twitter having a very strong presence. Pinterest, Instagram, Flickr and blogs were also popular, but to a lesser extent. Other platforms used by small numbers of institutions included Google+, FourSquare, Historypin, LibraryThing, Tumblr, Vimeo and Youtube, yet these are rarely used in conjunction with image collections and so are of less interest to this study.

In general, community archives were found to be making substantially less use of social media than larger institutions. This is because larger institutions tend to have far greater resources in terms of staff, funding, technological infrastructure, as well as digitisation and social media marketing expertise. Community archives are constrained by having limited funding, limited access to the technology and expertise required for digitisation and social media marketing, and a reliance on volunteers.

Through the Website survey and interviews, nine affordances or possibilities for action that are available to cultural institutions when using social media in conjunction with digital image collections were identified. These are presented in Table 1.

The affordances identified have been expressed in terms of organizational goals rather than the actions of users, as opposed to the work of Majchrzak et al. (2013). Although there is some overlap, these can be grouped under the general categories of:

- promotion,

- engagement,

- curation,

- collection building, and

- networking

| Affordance | Explanation |

|---|---|

| A1. Promoting events, services, and collections | Social media platforms represent marketing tools that enable cultural institutions to promote events, services, and collections. With regard to collections, there is a strong element of enhancing discovery. For example, including metadata such as descriptions and tags can enhance the discovery of collection materials, either within bespoke digital image collections or through commercial search engines. |

| A2. Engaging audiences | Having a social media presence facilitates two-way communication between institutions and users, giving users an opportunity to interact with content and representing an avenue that promotes audience engagement with collections (Russo et al., 2008). Using social media provides users with an additional point of contact with the organization. |

| A3. Broadening and diversifying audiences | Sharing content through social media allows cultural institutions to expand current audiences of user groups, in addition to attracting entirely new groups of users. Using social media provides users with an additional point of contact with the organization. |

| A4. Establishing a brand or identity | Through social media use, cultural institutions may establish a brand or identity (Kaplan and Haenlein, 2010). Providing a voice of authority on cultural issues. Maintaining a social media presence provides institutions with a platform for communicating with audiences as an authority on issues that emerge in relation to collection materials and the cultural sector. |

| A5. Curating exhibitions online | Cultural institutions can curate virtual exhibitions and collections by publishing images, captions, and stories through social media. This provides online public access to collection materials, as well as opportunities for user engagement with the institution. |

| A6. Encouraging multiple voices to enhance curation | The prevalence of Web 2.0 functionality within social media platforms allows users to perform participatory tasks such as contributing comments and uploading their own images, thereby facilitating co-curation and collaboration with users. |

| A7. Enhancing collections | Social media allows institutions to obtain user feedback and knowledge that can potentially enhance information about collections. |

| A8. Feedback and research | Some social media platforms provide institutions with metrics regarding views and traffic on their social media pages, particularly in relation to reach and engagement. This may help with identifying trending topics and issues, in addition to understanding audience demographics and content consumption patterns. |

| A9. Industry networking | Through social media usage, cultural institutions may network with other organizations and industry professionals, such as through liking and commenting on each other’s pages and content, and presenting co-curated collections and exhibitions. |

With regard to historical societies, the research found that in contrast to large cultural institutions, few host bespoke digital image collections on their Websites. Of the historical societies surveyed, almost all use Facebook as their primary social media platform, and those that promote their image collections rely on the photo stream functionality of social media platforms to host their collections.

The majority of Australian historical societies appear to be using Facebook. In many cases it is the only form of social media being used. Some interviewees suggested that Facebook is the most convenient platform because of the ease and speed of uploading and sharing images. Its popularity and widespread use makes it an obvious choice, with many interviewees expressing doubt that they could attract the same audience numbers on platforms such as Twitter or Pinterest. One interviewee noted that the organization has experienced greater difficulty with engaging the Twitter audience than with Facebook, as they had not yet obtained a substantial number of followers or retweets, and had generated little discussion on their Twitter feed.

Several barriers to participation in social media platforms were found to exist within historical societies. These include finding or developing the expertise required to establish and maintain a social media presence, the time requirements and creative challenges that coincide with generating content, and the risks associated with the sustainability of a social media presence in the long-term. The volunteer bases of historical societies in particular tend to be comprised of older individuals who do not belong to the Net Generation (Tapscott, 2008), who have had to adapt to technology rather than growing up with it. As a result, many volunteers have low levels of computer literacy, therefore some societies, such as the Knox Historical Society, have created an instruction manual to assist volunteers in using the Society’s Facebook page and Website.

The sustainability of maintaining a social media presence is another issue that is often raised. Community organizations in general have a high turnover of volunteers. In all of the historical societies included in the study, the management of a social media presence was the responsibility of a single individual, leaving them open to significant disruption should that volunteer leave the organization. Several interviewees also commented that there are many things that their organizations would like to do to enhance their internal collection management and promote their collections. Grappling with cataloguing extensive backlogs of donated materials, as well as organizing local community events, were commonly cited as activities that are accorded a higher priority and consequently resource allocation.

Finding the time to create content for social media posts can also present problems. A considerable amount of time and effort must be devoted by volunteers for them to be able to research and write content, as well as respond to user comments. Failure to do so potentially leaves the organization looking inactive. One strategy to reduce the amount of time required in maintaining a presence on multiple social media platforms is cross-pollination. For example, Carnamah Historical Society employs a strategy whereby a blog post is created on average once per fortnight, coupled with a tweet and Facebook update to advertise the blog post, with images used in the blog post also posted on Pinterest or Instagram. Carnamah tries to keep its Facebook posts generally broad and diverse in order to cater to the wide variety of interests amongst the audience of this platform. Another interviewee reported tweeting the same content as is posted on the organization’s Facebook page, albeit reformatted to meet the 140 character limit.

At the outset of the project, an assumption was made that a desire to digitise collections and share images with audiences would exist across all cultural institutions. Indeed, mainstream institutions such as state and national galleries, libraries, archives, and museums, have digitised large sets of historical photographs and made them available for online viewing through bespoke digital image collections, in addition to platforms such as Flickr. Although there was an awareness and expectation that historical societies may have less substantial digital collections and social media presence compared with mainstream institutions due to limited resources, the study found no clear pattern. A minority of sites had a strong presence in terms of user engagement and volume of content, but these were the exception.

Differing attitudes to the digitisation and sharing of images through social media can also be explained by varying attitudes of governance groups to custodianship, digitisation and sharing. Interviewees from approximately half of the historical societies expressed no sense of urgency with regard to sharing image collections online. The expectation was that members of the public will visit the physical archives and museums in person. The Knox and Whitehorse historical societies have undertaken substantial digitisation of their collections but do not provide online access to them. The Royal Historical Society of Victoria has not undertaken substantial digitisation of many photographs in its collections, despite having a strong collection of historical photographs in terms of their significance. This attitude is often reinforced by responses to a number of other, non-technological issues.

The Whitehorse Historical Society received a local Council grant to digitise the photographs in its collections, yet is hesitant to share those images online due to fears of legal repercussions associated with infringing copyright and privacy regulations. The Secretary commented that the Society does not own the photographs, but rather acts as custodian, given that many of the photographs have been freely donated by members of the public, often from personal family albums or professional studios. Indeed, other studies have found that publishing digital image collections online brings a range of copyright, ethical, and privacy considerations and risks that are not straightforward to negotiate (Ruge et al., 2017; Willett and Wright, 2015). For example, it can often be difficult for cultural institutions to identify the subjects of historic photographs, or who the original donors of particular collections are, as photographs are not always fully catalogued at the time they are accessioned. Seeking permission retrospectively can be both resource-intensive and frustrating.

Citing the ease of duplicating, transferring, and reproducing images, several interviewees expressed concern in relation to the potential for unauthorised re-use of images without proper acknowledgement of sources. Strategies such as scanning in low resolution and adding watermarks to images can potentially mitigate the risk of image appropriation, however they can involve additional handling that is beyond the available resources. Given that users have become accustomed to accessing information for free, the use of watermarks and low-resolution versions in the digital image collections of historical societies may be looked upon unfavourably. The Box Hill Historical Society found received a complaint over its use of watermarks over images posted on Facebook. They subsequently abandoned the practice, noting that they did not want to project having a sense of exclusivity or ownership over their collection materials.

One interviewee commented that historical societies often rely on donations and grant funding to stay afloat. They expressed a concern that freely sharing images online can impact on the revenue raised by historical societies through the sale of images. Charging a fee for access to digital collection materials represents an important source of potential income and a difficult trade-off to negotiate when the question of online image-sharing is raised.

As noted previously, the volunteer base of most historical societies is largely comprised of individuals of retirement age. Although each society appeared to have one or two volunteers with a high level of computer literacy, low levels of computer literacy were more the norm. Several volunteers indicated during interviews that although some members appreciate the potential benefits of online image-sharing and would like to see their respective historical societies make use of this activity. However, such a view was often at odds with the views of senior members of historical societies, making it difficult to reach consensus. In addition, historical societies have severely limited capacity and resources for undertaking digitisation and web publishing projects, and for maintaining a strong social media presence, particularly in terms of the technical expertise and volunteer time required.

Discussion

Several issues were found to impact on the online presence of historical societies and their realisation of specific affordances. Online image collections and exhibitions enable collecting organizations to showcase their holdings to the maximum number of viewers (A1, A2, A3, A5). The extent of a historical society’s online presence may also impact the reputation of the organization by influencing users’ perceptions if using the organizations’ Website or social media presence as a first point of contact (A4).

Social media platforms potentially enable community archives to network and collaborate with similar or supporting organizations. The Box Hill Historical Society uses Facebook to network with other popular social media accounts that relate to local heritage, particularly Lost Melbourne. Having a post shared by one of these pages often results in gaining a substantial number of new followers (A3, A9). Similarly, the Whitehorse Historical Society reported gaining new followers when a giveaway competition in collaboration with a magazine publication, tapping into the audience of the publication. This represents an example of cross-pollination of followers between two separate organizations as a result of a collaboration.

As noted in the findings, the lack of digitisation and sharing through social media can at least in part be explained by the attitudes of governance groups towards custodianship, digitisation and sharing. The reluctance to provide access to images has the potential to conflict with user expectations and impacts on the way users can engage with the collections and the organization (A2), perhaps the key affordance identified by the study. Although existing users may engage through an institution’s social media presence, a lack of content can make it difficult to broaden and diversify the audience (A3) or to establish the brand or identity beyond the existing user base (A4). It can also reduce opportunities for diverse voices (A6) and incentive for contributing to collections (A7).

Despite such concerns, some societies have achieved significant success in aspects of their social media use. The Box Hill Historical Society established its Facebook account in March 2015, and had approximately 2,800 followers be the start of 2017 (A3). The Society’s primary social media volunteer reported taking time to carefully monitor and respond to user comments left on the page. The results have been attracting ‘regular’ followers who comment on posts frequently, as well as lively discussions and debates taking place around local heritage topics and issues (A2, A6). It has been observed that users often become quite emotionally involved in these discussions, particularly due to nostalgic sentiment associated with historical places and times.

One of the most successful examples of embracing social media is the Carnamah Historical Society, which maintains seven separate social media accounts: Facebook, Twitter, a blog, Pinterest, Instagram, Flickr, and LinkedIn. Having a strong social media presence has significantly raised the online profile of the Society (A2, A3, A6), and contributed to it winning the community-based organization category of the 2015 Western Australian Heritage Awards. Carnamah is now featured in Landmarks, a permanent exhibition at the National Museum of Australia (NMA) that showcases Carnamah and thirty-two other heritage locations (Bowman-Bright, 2011). The Carnamah Historical Society maintains a strong commitment to sharing its collections online, with recognition that this contributes to fulfilling its mission statement, that is, to promote awareness of Carnamah and its local history.

Another important strategy for engaging social media followers is participation in discussions that take place within user comments. By facilitating two-way communication, community archives can benefit from the contributions of users in the areas of collection-building and enhancing information about collections (A2, A3, A4, A6, A7). Carnamah’s Virtual Volunteering Website is an example of a crowdsourcing initiative led by a community organization, with contributing transcriptions recently being recognised as part of the work for the dole (unemployment benefit) programme. The Whitehorse Historical Society has used Facebook to gain assistance from users in transcribing difficult-to-read collection materials (A7). The Knox Historical Society reported using a Reddit discussion thread to request help in identifying an artefact. Whilst this is linked to enhancing information about collections, it also represents a form of encouraging user engagement with collections by contributing to the work of the institution (A2, A3, A7). In the context of historical societies, in which attitudes towards image-sharing are often conservative, these crowdsourcing approaches represent an alternative way of engaging the organization’s audience beyond the pure sharing of content.

One of the key findings of the research was that none of the historical societies examined was found to have bespoke digital image collections. This is partly due to the technical expertise required and costs associated with the development and maintenance of such systems. Obtaining equipment such as scanners and storage devices, setting up Web hosting services, the digitisation process itself, as well as database management and Web publishing, can be costly to community organizations. Open source content management software tools such as Omeka, CollectiveAccess, ICA-AtoM, and Islandora are available (Hardesty, 2014), and are used by a small number of societies, for example, the Royal Historical Society of Victoria and the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives. However, there can be problems around the use of such tools. For example, though these platforms are usually free in terms of the financial cost, they require a high degree of expertise and substantial amount of resources to customise, implement, and maintain. As a result, social media photo streams often represent a more manageable alternative, being free to use, having low barriers to entry, a straightforward learning curve, and are user-friendly.

In addition to being a less costly and less resource-intensive option for creating and maintaining digital image collections, storing images on social media platforms brings the added benefit of enabling users to easily like and share them. This results in the circulation of the images throughout their own social networks and thus exposing the institution’s collection materials to new groups of users. In this way, community archives can tap into the social networking functionality of social media platforms to achieve audience broadening and diversifying (A2, A3). Related to this is the potential to connect to the pre-existing user bases that exist on social media platforms (Baggett and Gibbs, 2014; Kalfatovic, Kapsalis, Spiess, Van Camp, and Edson, 2008). Despite the prevalence of conservative attitudes towards image-sharing amongst historical societies, the sharing and re-use of images from cultural collections is the primary benefit of using social media, and particularly social media photo streams, as it potentially results in an ongoing cycle of sharing and exposure (A3, A7). By contrast, images posted on standalone digital image collections may remain hidden on institutional Websites if users are not actively searching for them, or if the navigation is too complex (Baggett and Gibbs, 2014; Beaudoin and Bosshard, 2012).

Conclusion

Although the study on which this paper is based sought to explore questions of social media use in conjunction with digital media collections at a wide range of Australian cultural institutions, the emphasis here has been on those historical societies which maintain collections. Within that context, it has presented the findings related to the research questions, including the identification of platforms in use, how they relate to the management of digital image collections, and the aims of such use.

Drawing upon the theory of technology affordances as a means of relating social media functionality to organizational goals, the study identified nine affordances associated with social media. However, it found that the success with which those affordances were exploited varied widely. It also found that social media photo streams reduce the need for bespoke digital image collections by providing community organizations with readymade platforms that not only facilitate image-sharing, but also audience broadening and diversifying through their social networking functionality.

Although the success with which historical societies use social media varies, it appears that many are grappling to reconcile a diverse range of views and attitudes towards online image-sharing. The major challenges identified include resourcing social media maintenance and digitisation projects, and overcoming low levels to computer literacy amongst members and volunteers. Regarding the accessibility of information, the study found that historical societies have a strong sense of custodianship, curatorship, ownership, in potential conflict with contemporary practices in information-sharing and user expectations.. Historical societies need to attract new generations of enthusiastic volunteers with technical expertise in order to adapt to the rapidly changing technological landscape and implement sustainable collection management practices. To achieve this, a strong online presence must be established that elicits good impressions of organizations from users who first encounter them online.

Ultimately, historical societies have a commitment to the local communities that they represent and a mission to fulfill community engagement with their collections. Achieving this will requires moving beyond traditional collection management systems and an overreliance on the physical presence of the organization. Organizations need to have innovative information management practices and the establishment of a powerful online presence to attract build and maintain new audiences.

About the authors

Courtney Ruge has a Bachelor of Arts with Honours in art history from the University of Melbourne, and a Master of Business Information Systems from Monash University with specialisations in knowledge management and librarianship, archival, and recordkeeping systems. She has worked as a research assistant on a number of projects exploring digital collections and community archives in Australia. She can be contacted at courtneyruge@gmail.com

Tom Denison is a research associate with the Centre for Organizational and Social Informatics, Faculty of Information Techology, Monash University. He teaches and conducts research within the fields of library and information science, and community and development informatics, with a particular focus on community engagement. He can be contacted at tom.denison@monash.edu

References

- Bakhshi, H. & Throsby, D. (2012). New technologies in cultural institutions: theory, evidence and policy implications. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 18(2), 205-222.

- Baggett, M. & Gibbs, R. (2014). HistoryPin and Pinterest for digital collections: measuring the impact of image-based social tools on discovery and access. Journal of Library Administration, 54(1), 11-22.

- Beaudoin, J. E. & Bosshard, C. (2012). Flickr images: what & why museums share. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 49(1), 1-7.

- Bowman-Bright, A. (2011, June 10). Carnamah’s place at the National Museum of Australia. [Web log entry]. Carnamah Historical Society and Museums Blog. Retrieved from http://www.blog.carnamah.com.au/2011/06/carnamahs-place-at-national-museum-of.html. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6uH99kU05)

- Cho, A. (2013). YouTube and academic libraries: building a digital collection. Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship, 25(1), 39-50.

- Denison, T. & Johanson, G. (2007). Surveys of the use of information and communications technologies by community-based organizations. Journal of Community Informatics. 3(2). Retrieved from http://ci-journal.net/index.php/ciej/article/view/316. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6uH9FaHZ0)

- Flinn, A. (2010). An attack on professionalism and scholarship? Democratising archives and the production of knowledge. Ariadne, 62. Retrieved from http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue62/flinn. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6uH9KU29L)

- Gaver, W. W. (1991). Technology affordances. In Proceedings of CHI'91, New Orleans, Lousiana, April 28 - May 2, 1991, (pp. 79-84). New York, NY: ACM.

- Gibbons, L. (2014). Culture in the continuum: YouTube, small stories and memory-making. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia.

- Gibson, J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. Reading, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- Hardesty, J.L. (2014). Exhibiting library collections online: Omeka in context. New Library World, 115(3/4), 75-86.

- Horava, T. (2010). Challenges and possibilities for collection management in a digital age. Library Resources and Technical Services, 54(3). Retrieved from https://journals.ala.org/index.php/lrts/article/view/5556/6837. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6uH9OuZx2)

- Kalfatovic, M. R., Kapsalis, E., Spiess, K. P., Van Camp, A. & Edson, M. (2008). Smithsonian Team Flickr: a library, archives, and museums collaboration in Web 2.0 space. Archival Science, 8(4), 267-277.

- Kaplan, A. M. & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons, 53(1), 59-68.

- Leonardi, P. (2008). Organizing technology: toward a theory of sociomaterial imbrication. Academy of Management Proceedings, 1, 6p.

- Majchrzak, A., Faraj, S., Kane, G. C. & Azad, B. (2013). The contradictory influence of social media affordances on online communal knowledge sharing. Journal of Computer‐Mediated Communication, 19(1), 38-55.

- Mansfield, T., Winter, C., Griffith, C., Dockerty, A., Brown, T. (2014). Innovation study: challenges and pportunities for Australia’s galleries, libraries, archives and museums. Canberra: Australian Centre for Broadband Innovation, CSIRO and Smart Services Co-operative Research Centre. Retrieved from http://www.historyvictoria.org.au/wp-content/uploads/GLAM_Innovation_Study_September2014-Report_Final_accessible-1.pdf. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6uH9331zP)

- Pett, D. (2012). Use of social media within the British Museum and the museum sector. In C. Bonacchi (Ed.), Archaeology and digital communication: towards strategies of public engagement (pp. 83-102). London: Archetype.

- Phillips, A. (2015) Facebooking it: promoting library services to young adults through social media. Public Library Quarterly, 34(2), 178-197

- Proctor, N. (2010). Digital: museum as platform, curator as champion, in the age of social media. Curator: the Museum Journal, 53(1), 35-43.

- Ruge, C., Denison, T., Wright, S., Willett, G., & Evans, J. (2017). Custodianship and online sharing in Australian community archives. In H. Roued-Cunliffe & A. Copeland (Eds.), Participatory heritage. (pp. 79-86). London: Facet Publishing.

- Russo, A. (2011). Transformations in cultural communication: social media, cultural exchange, and creative connections. Curator: The Museum Journal, 54(3), 327-346.

- Russo, A., Watkins, J., Kelly, L. & Chan, S. (2008). Participatory communication with social media. Curator: The Museum Journal, 51(1), 21-31.

- Springer, M., Dulabahn, B., Michel, P., Natanson, B., Reser, D., Woodward, D. & Zinkham, H. (2008). For the common good: the Library of Congress Flickr pilot project. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/flickr_report_final.pdf. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6uH9TcUsi)

- Stevens, M., Flinn, A. & Shepherd. E. (2010). New frameworks for community engagement in the archive sector: from handing over to handing on. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 16(1-2), 59-76.

- Tanenbaum, J. G., Williams, A. M., Desjardins, A. & Tanenbaum, K. (2013). Democratizing technology: pleasure, utility and expressiveness in DIY and maker practice. In CHI 13: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 2603-2612). New York, NY: ACM.

- Tapscott, D. (2008). Grown up digital. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional.

- Terras, M. (2010). Digital curiosities: resource creation via amateur digitization. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 25(4), 425–438.

- Willett, G., & Wright, S. (2015). Copyright, copywrong, and ethics: digitising records of the Australian gay and lesbian movements from 1973. In R. Wexelbaum (Ed.), Queers online: LGBTI digital practices in libraries, archives, and museums (pp. 129-144). Sacramento, CA: Litwin Books.

- Xie, I & Stevenson, J. (2014). Social media application in digital libraries. Online Information Review, 38(4), 502-523.