Understanding Elders’ knowledge creation to strengthen indigenous ethical knowledge sharing

Jelina Haines, Jia Tina Du, Gus Geursen, Jing Gao and Ellen Trevorrow

Introduction. This study investigates Indigenous Elders’ oral knowledge creation as it is transmitted intergenerationally through storytelling. Synthesising oral knowledge to written text is problematic because the integrity of the spoken knowledge must be altered to suit the dominant language system, sometimes devaluing its significance.

Method. Using the principles of a community-based participatory study grounded by visual ethnography, data were collected from audio and video dialogic interviews with four Elders and one young participant as potential future knowledge keeper. Participants gave informed consent for the dissemination of these experiences.

Analysis. Data were transcribed and open coded, providing empirical information for analysis. The process was intended to capture unobserved shared practices and explore tacit and explicit knowledge creation as it evolved during social interaction among participants.

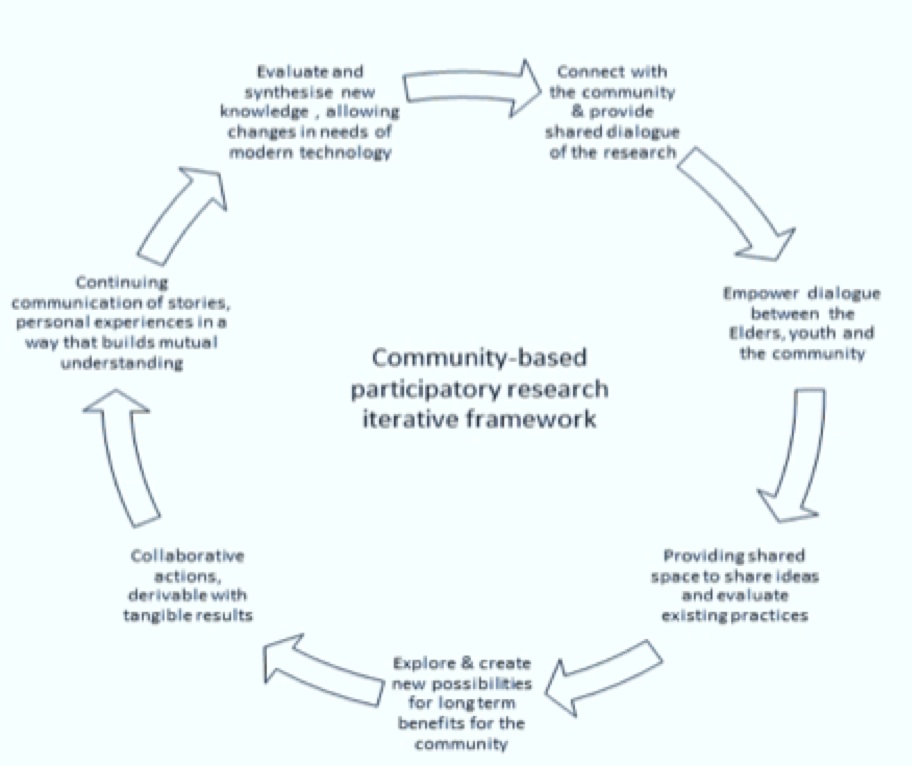

Results. Preliminary findings provide a structure for understanding the inherent value of participants’ tacit and explicit knowledge creation. This led to the development of a community-based participatory research iterative framework. This framework provides the research participants with the opportunity to actively engage with the research process.

Conclusion. The findings also assist in emphasising co-learning and collaborative study for ethical practices in conducting research with Indigenous people.

Introduction

The amount of shared Indigenous knowledge is declining due to a loss of a holistic connection to social and cultural contexts, which undermines the integrity of the Elders’ knowledge (Nakata and Langton, 2009). The numbers of Elders who have a considerable amount of oral knowledge is diminishing. Oral tradition is a vanishing resource; as knowledge keepers pass away, the need to preserve such information has become imperative. It is necessary to review oral tradition or oral knowledge in order to contextualise our investigation theoretically. In this research, oral tradition and oral knowledge are used interchangeably. Early scholarly information has been used to recognise the richness of oral knowledge and to retell some interpretations. Oral tradition articulates human history, human practices of communication of culture, tradition, and visual understandings of the past. For example, Vansina (1985) defined oral tradition as a history of verbal messages, an exercise of ‘cultural expression and oral statements from the past beyond the present generation’ (p. 28). Thus, oral knowledge generates a document of events and communications encompassing cultural practices such as personal and practical experiences, and perceptions of traditional life (Vansina, 1985).

Henige (2002) reasoned that irrespective of the historicity of oral tradition, it is a taxonomy of information that ‘should have been transmitted to several generations and is to some extent, a common property of a group of people’ (p. 233). We rationalise Henige’s views; for example, oral tradition is not a type of knowledge that can be easily written or transcribed; individual and personal experiences are distinct.

Similar arguments have been noted by Cruikshank (1994) who describes oral tradition as ‘not a set of formal text’; rather, it is a ‘living vital part of everyday life’ practices that are difficult to transfer (p. 10). Cruikshank (1994) states that oral knowledge is ‘inclusive rather than exclusive’ (p. 10). In this paper’s context, the wealth of oral knowledge is the fabric of a community’s history, identity and culture. A lack of full understanding of the inherent value of oral tradition will degrade its historical authenticity. To respect the validity and belonging of identity, we capitalise the words Indigenous and Elder as these terms are used to identify a person’s ethnicity and belief system. As discussed earlier, ‘oral knowledge is fluid’ and is safeguarded by Elders ‘who make up only a small percentage of the total population’ (Beaton, Fiddler and Rowlandson, 2004, p. 6). Thus, the successful transmission of oral knowledge is dependent on the Elders’ capability to pass on the knowledge before the full richness of the stories diminishes.

Indigenous knowledge keepers

Elders who are chosen as knowledge keepers are given the responsibility of passing on their knowledge to the future generation. However, to be called a knowledge keeper in the Indigenous society, an Elder must be recognised and respected for their selfless contribution to their people and valued for their knowledge gained from generations of stories and living on the land (Warburton and Chambers, 2007).

Iseke-Barnes (2009) noted that Elders are the ‘educators of children, youth, adults and communities’ storytellers and historians’ (p. 25), whose stories are used as educational tools to sustain communities’ cultures and their traditions. Today, there is a need for the Elders’ knowledge to be documented, and it is of vital importance that it be carried out sooner rather than later (Nakata and Langton, 2009). Otherwise, it will be lost forever. This concern is highlighted by Emery (2000) who pointed out that as the Elders pass away, the full richness of oral knowledge diminishes. Presently, the main reason for the loss of Elders’ knowledge is their untimely deaths and some, by the time of their death, have not chosen the appropriate person to carry forward the knowledge for future generations.

Joseph (2014) suggested that each Elder possesses an invaluable, distinct oral knowledge. This unique knowledge encompasses wisdom, perceptions, innovations and practical experiences associated with the Indigenous community (Agrawal, 1995). However, synthesising Elders’ knowledge to written text is sometimes problematic because the integrity of the spoken knowledge must be altered to suit the dominant language system (Battiste, 2005). Consequently, there has been an inevitable loss of Elders’ knowledge because it was not captured ethically and was often fragmented or suppressed. Another reason for the erosion of knowledge is that Elders’ knowledge today is hindered by modern media cultures, which entrances the younger generation’s imagination by imparting information that is not compatible with Indigenous ways of knowing (Emery, 2000). According to Aunty Ellen Trevorrow (personal communication, August 31, 2017), ‘the loss of some of our cultural stories and traditions are forever lost, but we do our best to pass on what we have left’. So, to explicitly measure the extent of the loss of Indigenous culture and languages is outside the current framework of this research.

The present study aimed to capture and explore the inherent value of Elders’ tacit (knowledge tools) and explicit (survival tools) knowledge creation. It also sought to employ ethical research practices by using the principles of community-based participatory research and informed consent.

We focused on working with four Indigenous Elders, who have knowledge and expertise of both past and present traditional ways of teaching, and one young participant whom they teach and mentor. The information collected from research participants included life experiences influenced by cultural tradition, wisdom and communal stories that have been passed down from generation to generation.

An ongoing community consultation was also carried out, and a part of the ethical process was in collaboration with the Ngarrindjeri community in the Lower Murray River Lakes and the Coorong areas in South Australia (Du and Haines, 2017; Du, Haines, Sun, Partridge and Ma, 2015). The empirical questions that guided this paper include:

- How has knowledge creation evolved from the application of cultural and communal practices?

- How can we develop a better framework and protocols to allow a more ethical representation of Elders’ knowledge in Indigenous research?

This investigation primarily focuses on a group of Elders, who are not the general overall population of all the Indigenous people within the Ngarrindjeri country. Some of the data we collected for this research contains ‘sensitive stories and therefore needed further consent from individual participants’ (Haines, Du, Trevorrow, and Gibbs, 2017, p. 481). Hence, the findings may not reflect the general view of the population. Instead, our results offer an insight into the shared knowledge practices of the research participants.

Methodology

This research used a qualitative method to gather data through dialogic interviews and video recordings of the same discussion. It was guided by the principles of community-based participatory research and was theoretically grounded by the methods of visual ethnography. Community-based participatory research has been developed over the past twenty years and is viewed as the leading method of generating collaborative partnership between the researchers and the community. Its principles of reciprocity and informed consent ensure the confidentiality and transparency of information gathered, which underpins trust and respect. Jacquez, Vaughn and Wagner (2013) pointed out that using community-based participatory research in addressing issues particular to marginalised communities is effective in removing the inequality of power from the research process. LaVeaux and Christopher (2009) emphasise that community-based participatory research is about creating a space for research participants to contribute ‘utilising Indigenous ways of knowing’ and interpret data ‘within a cultural context’ (Table 1). The fundamental principles of researching with Indigenous communities using a community-based participatory research are to recognise that members of the community under study are the experts of their knowledge.

| Community-based participatory research principles as described by Israel et al. in 1998 (LaVeaux and Christopher, 2009, p. 3) | Community-based participatory research principles relevant to Indigenous research as described by LaVeaux and Christopher in 2009, p. 7 |

|---|---|

| 1. Build on strengths and resources of the community | 1. Recognise ethnic sovereignty |

| 2. Facilitate collaborative partnerships in all phases of the research | 2. Differentiate between ethnic and community membership |

| 3. Integrate knowledge and action for mutual benefit of all partners | 3. Understand ethnic diversity and its implications |

| 4. Promote a co-learning and empowering process that attends to social inequalities | 4. Plan for extended timelines |

| 5. Involve a cyclical and iterative process | 5. Recognise key knowledge keepers |

| 6. Addresses health from both positive and ecological perspectives | 6. Prepare for leadership turnover |

| 7. Disseminates findings and knowledge gained to all partners. | 7. Interpret data within the cultural context |

| 8. Acknowledge historical experience with research | 8. Utilise Indigenous ways of knowing |

Visual ethnography

Traditional approaches to ethnography require a significant amount of fieldwork and field data analysis, which in turn requires more time. Visual ethnography is a contemporary approach to research that is designed not to investigate the whole culture, but rather to examine a specific aspect of research participants’ knowledge (Haines et al., 2016). Furthermore, visual ethnography is not a substitute for anthropology; instead, it can be viewed as a representational method that focuses on the parts of culture that cannot be retrieved by written words alone (Trafí-Prats, 2009). Delgado (2015) characterised visual ethnography as a transformative paradigm: a theoretical framework of principles and beliefs aligned with community-based participatory research. Pink (2013) stated that visual ethnography uses images to produce new knowledge and focuses on the visual contexts of culture within the society. It is an innovative process to gain useful insights into the human behaviour of acquiring new knowledge in less time. Also, the use of visual images as a metaphor to gather new information parallels with the Indigenous people’s cultural tradition of storytelling. The visual ethnographic method enriches the knowledge-sharing process by allowing unobserved social interactions such as mannerisms, facial expressions and emotions to be captured by a video in a natural setting. Both community-based participatory research and the visual ethnography method seek to illustrate the social responsibility and foundation of ethical research practices. Together, they systematically take advantage of what modern technology offers, to preserve and retain the integrity of the research participants’ voices.

Research design

We ensured that an informed consent and transparency were established before the research began. The research participants consented to be photographed and recorded by both audio and video recordings and their active involvement in the project formed the foundation of ethical research practices. We made certain that shared research involving Indigenous people meant recognising their significant contribution to the project as co-researchers. All quotations are referred to as personal communication as another cultural parameter that we are proposing as part of ethical research that includes the dates when the interview was recorded. All participants included in this paper were part of the editing process, especially the preliminary findings. One Elder is also recognised as the co-author of this paper.

Ngarrindjeri Ruwe (Country) and study participants

The Ngarrindjeri country is situated at the mouth of the Murray River in South Australia. The Ngarrindjeri Nation is divided into eighteen laklinyeris (tribes), each with its own boundaries. The Ngarrindjeri people continue to occupy and manage their inherited lands and waters within the area of the River Murray, Lower Lakes, and the Coorong area. The Ngarrindjeri culture and tradition are a knowledge system that is based on Creation stories, oral traditions and practices, which are passed down from generation to generation (Tendi et al., 2007). They see their homelands as a cultural landscape that was shaped during the creation of Ancestral Beings. Their cultural stories are detailed documents of the ecological changes of the Ngarrindjeri nation (Tendi et al., 2007).

Research location: Camp Coorong

Camp Coorong is located about 200 kilometres South-East of Adelaide, adjacent to Bonney Reserve and South Australia’s Coorong National Park. The research participants mostly come from Camp Coorong, Meningie (Figure 1). The Ngarrindjeri Land and Progress Association was incorporated in 1985. The Aboriginal Land Trust purchased the land for Camp Coorong as a place for South Australia’s school children to go to learn about Ngarrindjeri culture and history with the long-term aim that this experience will contribute to the reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. Camp Coorong is a community-based education facility and tourism enterprise that is now managed by Aunty Ellen Trevorrow along with other community members on behalf of the Association.

Figure 1: Research Location, Camp Coorong Race Relation and Cultural Museum (from http://ourriverourfuture.org/the-living-murray/lower-lakes-coorong-and-murray-mouth/)

Ngarrindjeri participants from Camp Coorong and Meningie

The research participants consisted of four Elders and one young participant. Table 2 shows the demographic life and work experiences of each participant. Their experiences and roles in the community also demonstrate the profound connection and devotion to the continuation of Ngarrindjeri culture. While cultural sensitivities are taken into account, research participants gave their consent and wrote down their names accurately rather than using identifying code numbers. The words Aunty and Uncle in this study refers to the Elders and is a term the community uses to show respect for their status.

| Participant | Age | Gender | Main Language | Community Status | Role in the community | Employment Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aunty Noreen Kartinyeri | 58 | F | English/ Ngarrindjeri | Elder | Basket weaver | Caterer & Cleaner |

| Ellie Wilson | 19 | F | English/ Ngarrindjeri | Youth | Cultural Guide (Tourism) - taking groups to bush walk, tour trips to the museum and 42-mile camp crossing, teaching basket weaving | Cultural guide & Basket weaver |

| Aunty Ellen Trevorrow | 61 | F | English/ Ngarrindjeri | Elder | Cultural educator, Elder and Ngarrindjeri Basket weaver | Manager (NLPA), Treasurer (NRA) |

| Aunty Alice Abdulla | 73 | F | English/ Ngarrindjeri | Elder | Cultural educator | Retired Teacher aide |

| Uncle Major (Moogy) Sumner | 58 | M | English/ Ngarrindjeri | Elder | Cultural adviser (NRA) and Vice-Chair (NLPA) | alkenjeri Dance director and Cultural educator |

Data analysis and data gathering tools

Research participants were carefully identified and selected based on their role as an Elder and substantial contribution to the community. The participation of the younger participant was crucial because of her current status as the granddaughter of a prominent Elder and her role in the community (Table 2). Data were collected from five research participants that included three female Elders and one male Elder, between 58 and 73 years of age, and the young participant, who was 19 years old. Data were gathered during field appointments between February to November 2016, and follow-up visits were also necessary. The dialogic interviews were divided into two parts; the audio session lasted one to two hours, including frequent coffee breaks. The second part was a video recording of our visit to the significant places where the individual participant’s knowledge stories originated. The audio interviews were transcribed and open coded. The coded data were examined for categories and themes which form a base for the contextual analysis of cultural and communal practices (Figures 3 and 4). As part of the collaborative and ethical research, ongoing consultation with the Elders, awareness of cultural protocols and respecting the traditional laws were incorporated into the process across all stages. Our preliminary findings were presented as an open dialogue. Therefore, excerpts from research participants are also included in our results.

Audio and video dialogue interviews

The dialogue interview was a suitable gathering tool because it allows a dialogic autonomy between participants and the researchers. Dialogic interviews is an egalitarian method of research because it takes into account the legality of participants contribution, which carries new opportunities and shared insights into ethical research. In this case, the dialogic interviews methods recorded the inherent meanings of cultural and communal stories of participant’s actual words, and in turn, collective knowledge sharing transpired (Figures 2 and 3). We intended to engage the participants in a reflective (participants were reminiscing childhood stories) and generative (how stories are shared) conversation. This process provided us with an understanding of how participants responded to our questions and encouraged an insightful discussion, which was relevant to the research.

Both the audio and video interviews recorded the same data information, but the video footage adds another dimension to our research. The video captured verbal expression, social interactions, emotion, body language and gestures when participants responded to the given questions. Each question was contemplated upon by the participants and then a moment of silence occurred. Silence did not mean that the Elders do not understand the questions being asked; rather, it indicated that they took time to think about their responses. We also paused for a moment and joined the silence until the Elders were ready to continue. Furthermore, the video recordings were used as documents to support the validity and reliability of the content, as well as the accuracy and accountability of the written texts.

Preliminary findings and discussion

Intergenerational retelling of Elders’ oral knowledge creation practices that are pertinent to the younger generation

Field evidence shows the intergenerational practices of passing on cultural and communal knowledge (Figures 3 and 4). The purpose of retelling these practices is to build trust, respect and reciprocity as well as continue the belief in storytelling. According to Uncle Moogy (M. Sumner, personal communication, June 17, 2016), the process of incrementally retelling the stories is to ensure that it is valued and not misappropriated. However, Elders are concerned that the continuous misuse of unwritten stories, which are performed during cultural events, is likely to expose the stories to knowledge manipulation. For example, participating in ceremonial events does not make a person an expert on Ngarrindjeri culture. Uncle Moogy added ‘one way to understand Ngarrindjeri knowledge practices is to be part of the community and walk alongside with the Elders’ (M. Sumner, personal communication, June 17, 2016). In other words, cultural practices, experiences and wisdom are constantly evolving, and therefore, the transmission of the Elders’ knowledge has to be translated into cultural context. Keeping this in mind, as we engage in Indigenous knowledge sharing, we have to be mindful of cultural protocols, and the laws that apply to communal and cultural stories.

Elders’ perception on living in two worlds

Uncle Moogy draws our attention to the perception of living in two worlds (M. Sumner, personal communication, June 17, 2016). He added that surviving in two worlds means rationalising his outlooks on life under two knowledge systems (Aboriginal and Western Laws).

In some ways he said, it contradicts each belief system rather than working together. Uncle Moogy points out that

Every action we do, we have to justify ourselves. Whom do we have to justify to and why? We have to justify to ourselves…we justify ourselves to our Elders, to the community…to the Western society. In saying that, if we value the traditional laws, our knowledge…you have to consult the community as a lot of people, doesn’t do it. We are clever people; we are resilient and able to survive in both worlds” [Ngarrindjeri Laws and the Western Laws]. In the western laws…we have to make a living to pay our bills, buy food and send our kids to schools. While maintaining our traditional laws...our stories are our cultural survival tools and identify of who we are and where we came from. (M. Sumner, personal communication, June 17, 2016)

He also prompted us to acknowledge who we are:

Strong knowledge structure is knowing who you are and where you belong. It is part of your identity, your culture, your creation stories and tradition…learn to respect yourself too, without your culture you haven’t got much. (M. Sumner, personal communication, October 24, 2016)

Maintaining cultural identity is part of the Indigenous ways of knowing, which involves caring for the country and the land. This sentiment is strongly emphasised by Ellie Wilson as she affirms her understanding and her connection to her ancestral land:

For me, caring for the country is very important because if we didn’t have our country…we would have nothing to stand for…we can also be a Ngarrindjeri but what is Ngarrindjeri if you got nothing to go with it…like if you don’t have your land, you don’t have your birdlife or wildlife…what is Ngarrindjeri it’s just a word…if you are not connected to your culture, your land…simple as that. You can also be Ngarrindjeri but if you don’t know what it is…why you’re talking about it. (E. Wilson, personal communication, November 16, 2016)

Both participants’ views show personal resilience and determination of surviving in two worlds and being able to recognise both knowledge systems and reconcile them in their daily life practices. This finding provides tangible evidence of the participants’ beliefs and ideas that are difficult to express through written text alone. Therefore, the excerpts provide a voice and depiction of life as they see it. The younger participant’s views were significant and critical to this study, and notably with future research implications.

Research question 1: How has knowledge creation evolved from the application of cultural and communal practices?

We used the Western concepts of describing the Elders’ knowledge types as a point of dialogue. In this case, it recognises both knowledge systems. The Elders’ knowledge creation evolved from the application of two kinds of information:

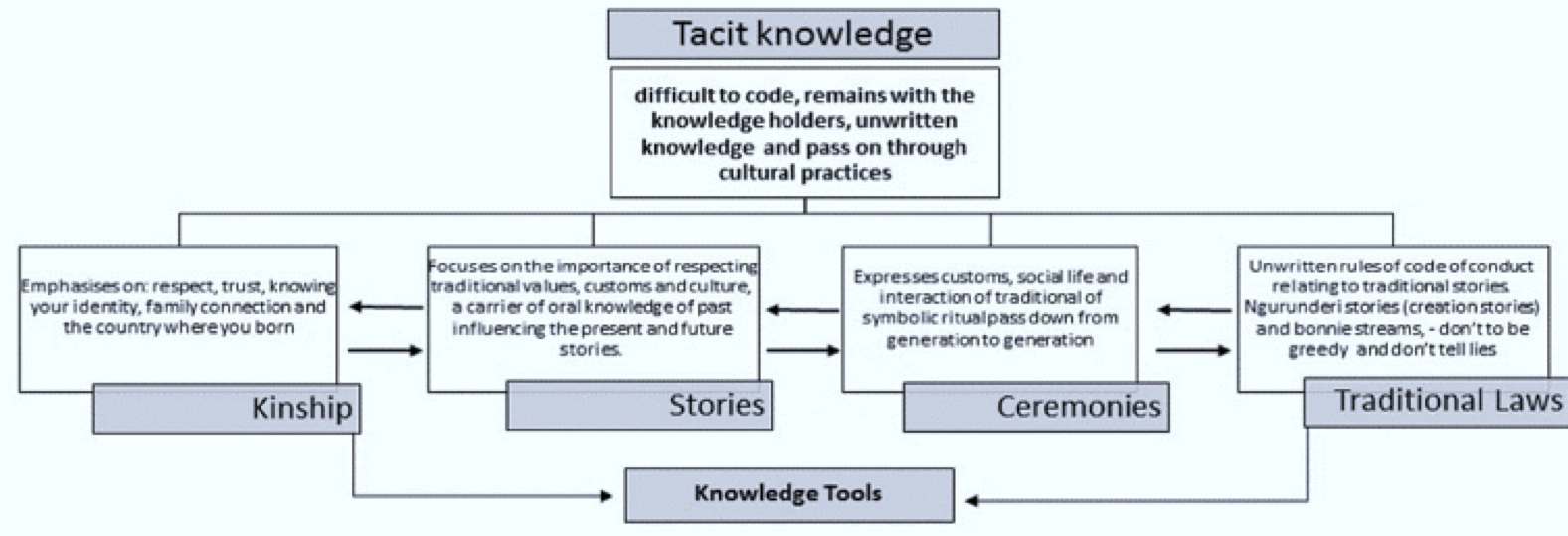

(1) Tacit (tools) knowledge: unrecorded and difficult to document as the individual holds it. When the knowledge keeper passes away, this unrecorded information is lost (Figure 2). This is often a familiar case in Indigenous communities.

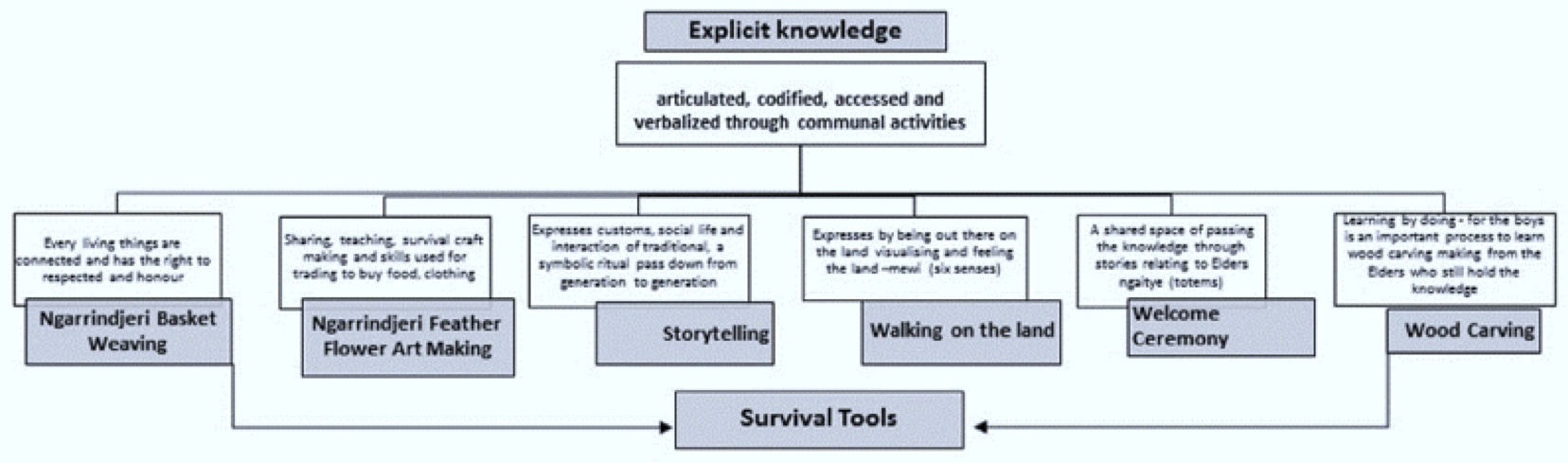

(2) Explicit (survival) knowledge: codified, readily available, recorded and stored in certain media and verbalised in various forms (Figure 3). For example, in Figure 3, the primary survival tools are basket weaving, feather-flower art making, and wood carving with a purpose for trading with other goods. Welcome ceremonies and storytelling are used as platforms to disseminate knowledge stories that are relevant to laws, protocols and beliefs, which are embodied in cultural and communal practices (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2: Tacit: cultural practices (knowledge tools)

Ngarrindjeri Elders’ tacit and explicit knowledge creation process

Figure 2 demonstrates tacit knowledge as accumulative, unspoken and often personal stories that are preserved within the family and only available to selected knowledge holders. Similarly, Figure 2 exhibits a cyclical process of tacit stories (knowledge tools) which symbolises the cultural landscapes of participants’ identities and beliefs. In this view, tacit knowledge is perceived as the foundation of Indigenous knowledge creation. However, codifying tacit knowledge will take time and trust, and disseminating these practices can be challenging. Explicit (survival tools) stories are practical information that is permitted to be widely shared and are part of daily life practices (Figure 3). It is socially translated, verbalised, and codified through communal activities as the participant's main survival tools to trade and continue living on the land (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Explicit: communal activities (survival tools)

Conversely, the changing environment of explicit knowledge hinges on how participants use, translate and disseminate their stories. Figure 3 summarises the participants’ collective knowledge, which is used as primary survival tools.

We also found that it is problematic to convert explicit back to tacit knowledge unless these activities are reframed and internalised using the Elders’ knowledge as a point of reference. For example, practical skills and wisdom, which are gained from basket weaving, can be synthesised into new insights. Therefore, tacit and explicit knowledge is not static; rather, the inherent value of the Elders’ knowledge creation evolves as the society changes. These changes reveal how cultural and communal activities are delivered by storytellers. For example, storytelling is aimed at enriching the participants’ knowledge acquisition. Although, the transferral of the Elder’s tacit and explicit knowledge to future generations is gradual. According to Aunty Ellen Trevorrow (personal communication, July 07, 2016), this process guarantees that future knowledge keepers are ready to take on the responsibility as future knowledge keepers.

Understanding knowledge transmission at different age level

In this research, storytelling was a common tool used to stimulate the participants’ memories and strengthen their interests during communal activities (Figure 3). We were fortunate that during one of our fields visits Aunty Ellen and Ellie were working on a weaving project (Figure 4). On this occasion, we witnessed the knowledge transmission in practice. Basket weaving is the main tool of passing on Aunty Ellen’s stories (Figure 4). According to Aunty Ellen, these activities are ‘our way of passing on our stories to the next generation’ (E. Trevorrow, personal communication, July 07, 2016). It also shows that through learning by doing, Ellie is engaged more, while being guided through the process of weaving. For Aunty Ellen, there was a sense of accomplishment and assurance that her knowledge had been passed on to the right person. We can, for example, see the importance and the sentimental value of understanding the practical process of weaving.

Figure 4: Aunty Ellen Trevorrow and Ellie Wilson

Aunty Ellen emphasised that the continuation of weaving to the next generation is crucial and asserted that:

Our weaving creation is like our children; each stitch carries our stories pass on by generations of Elders. I believed our weaving object we create is like our children; they don’t belong to us. We just a vessel to channel our stories through weaving and letting them go to share their own stories to the rest of the world but it also needs protection from misappropriation. (E. Trevorrow, personal communication, July 07, 2016)

Furthermore, what is pertinent to the younger participant, Ellie, is that her knowledge is firmly connected to the land as she continues her learning as a future knowledge keeper. It manifested in her views about the current environmental change of her country and stated:

My whole life is always in this place [Bonney Reserve]; it doesn’t matter how many times that I could find things that are important to me. Camp Coorong, Bonney Reserve and the Peninsula, these are the places that hold everyone together. We have so much stuff that could break our family apart…like losing Pop [Grandfather], losing the people that meant so much to us. This place…just held us together…this place brings us back [Bonney Reserve]…its home…if you got somewhere…that you love and in a way, you know that it means to you more than anything that you have connection to…treasure it, spend as much time, on it or with it as you can. I spend as much as I can over here…the land out here, either by myself or with the groups… I love it…because you got no idea when is going to be gone. I have no idea if a big wave or tsunami will come straight through the dunes and take all these [Bonney Reserve] from me. (E. Wilson, personal communication, September 09, 2016)

The findings also show that living on the land and caring for country is central to the development of Indigenous knowledge creation. For example, in regards to the feather flower art making (Figure 5), Aunty Alice emphasises that:

We, as Ngarrindjeri people we take care our Ngaitye (Totem), we have the responsibility to care for them and to make sure that they are happy and healthy, where they are. The Ngori (pelican) is my Ngaitye, so I have the responsibility to care for my totem. I am grateful for my Ngaitye for providing me with the feathers… We never kill a pelican for the purpose of getting their feathers. We will wait when one of them dies at the natural cause. (A. Abdulla, personal communication, February 28, 2016)

Figure 5: Aunty Alice Abdulla and Jelina (researcher) (Image credit: Ali Walker)

Similarly, learning by doing also plays a major role in the knowledge creation of Aunty Noreen’s upbringing:

I am 58, and I am still learning but when I was growing up, Mum and Dad always there for me….until they get sick and then I have to look after them. I follow my dad and go with for fishing….I prepared the old ways because it was not strict…and we always go out and learning new things from the land. Dad…used to teach how to fish traps and then…he will say…stay there, but I always follow him, to go fishing, and he would say, whatever you do…do not put your hands on the fish, but as a kid, you never listened, what I did, I put my hand on the mouth of the fish traps, and my hand get stuck. Now, what I learned from my mum and dad…always reminded me to keep going. (N. Kartinyeri, personal communication, July 07, 2016)

Findings also suggest that the Elders’ knowledge creation introduces a theory of information. A theory of the self-transcending process of tacit-embodied knowledge on the right hand and explicit-embodied knowledge on the left; both practices encompass a sense of emerging evidence-based opportunities (Figures 3 and 4). One possibility is the ability of tacit and explicit knowledge to adapt to learning circumstances influence the participants’ upbringing, their beliefs, ways of knowing, and their perseverance in preserving their cultural and communal practices. Also, synthesising and disseminating Elders tacit and explicit knowledge through storytelling, cultural activities and within a cultural context can assist in the process of long-term partnership.

Research question 2. How can we develop a better framework and protocols to allow a more ethical representation of Elders’ knowledge in Indigenous research?

We developed a framework and protocols that focused on shared dialogue in working with the Ngarrindjeri community. This approach provided a space for collaborative discussion. The seven phases of the community-based participatory iterative research framework are designed and implemented as a mutual process that takes into account the participants’ opinions and was not aimed at an analytical procedure nor solutions for the short outcome.

Figure 6: Seven phases of Ngarrindjeri Community-based participatory research iterative framework

The framework is intended to empower the ongoing commitment to the community throughout all stages of the investigation and beyond the frame of inquiry. The cyclical framework employs a traceability process of ‘connecting to the community, empowering dialogue, sharing ideas, evaluating existing practices, exploring and synthesising new knowledge collectively’. We are continually refining the framework as new tangible evidence transpires from transcribing the data that has been gathered. Figure 6 is proposed as an experimental framework, which in turn, is subject to simplification as the research progressed. Existing practices were also recognised, which further added feasibility of the research. Admittedly, the process demanded time and effort, but the iterative process helps to identify any research issues that may arise. In this manner, it creates a truthful partnership between the community and the researchers.

| Ngarrindjeri community-based participatory research principles and protocols described by Aunty Ellen Trevorrow (personal communication, August 29, 2017) |

|---|

| 1. Respecting communities boundaries of the Ngarrindjeri Nation |

| 2. Continue to recognise and respect our culture, kinship, traditional laws and country |

| 3. Recognise and work in partnership with key knowledge keepers |

| 4. Understand cultural and language diversity and be kind to one another |

| 5. Acknowledge and respect the Elders for the stories passed on to us |

| 6. Interpret data within the cultural context of reconciliation and shared access to research |

| 7. Plan for extended timeline research and ongoing partnership for the benefit of the community |

| 8. Prepare for leadership turnover and develop a Ngarrindjeri Nation Research Centre |

The Ngarrindjeri community-based participatory research principles and protocols reaffirm the aims of reciprocity and informed consent partnership of study. This is combined with the Ngarrindjeri community-based participatory research iterative framework. It generates a two-way shared trust in which co-learning and the dissemination of findings are mutually agreed upon. Using both frameworks, the integrity of oral knowledge that is shared with research participants is handled with great respect and care. This process ensures and recognises that information is accurately gathered, is translated within a cultural context, and that appropriate management policy for data retention are put in place. Research participants’ stories are given the opportunity to synthesise with new knowledge. For that reason, excerpts from participants have intellectual characteristics that add rigour and trustworthiness to the research and provide context for the translation of stories. Informed consent ensures the respect of culture, tradition and identity of those involved (Haines et al., 2017).

A consensus was emphasised by Uncle Moogy Sumner:

I can only yanun (speak) for the Ngarrindjeri Ruwi (Country). Each story connected to different communities and certain talkuni (ceremonies) belong to that community…and it should be translated the same as how it was told. (M. Sumner, personal communication, June 17, 2016).

The questions were structured and implemented according to the consent given (Haines et al., 2015). In respect to the nature of the research, sensitive issues concerning family matters were omitted. Instead, the questions were designed to focus on individual knowledge. A cornerstone of an ethical research relationship with our participants is the respect and the trust that we have built over the last fifteen years (Du and Haines, 2017; Haines et al., 2017). Informed consent is about respecting the knowledge that we are given and making sure that virtuous research practices are applied. Another consideration that we added is that every participant was compensated with their time by giving them an honorary voucher and also by conducting follow-up interviews. We clearly stated the benefits that the community would gain from the research. Indigenous participation are not considered as symbolic inclusions; instead, they are acknowledged as co-researchers, which values the unity, diversity and cultural pluralism in the information field. This approach is the first step in assuring ethical practices.

Conclusions and future research

The preliminary results convey the research participants’ knowledge creation as a continuing adaptation of new understandings that is strengthened by tacit and explicit knowledge, which has been passed on during storytelling.

This research is also an initial examination of how Elders’ knowledge is shared intergenerationally. It shows that Indigenous Elders’ knowledge is a richly woven fabric of texts. This concept is influenced by the combination of cultural and communal practices shown in Figures 2 and 3. Moreover, the results reveal that storytelling is integral to the continuing process of participants’ knowledge creation. In the strongest sense, the Elders in this research are the custodians of culture, keepers of tradition and teachers of knowledge. Elders’ stories and practical experiences directly reflect on collective history, which is also a reflection of their cultural identity as Indigenous people. The results also show that it is imperative that informed consent is embedded in the research. The proposed framework and protocols are necessary for assisting us in implementing collaborative research partnership and shared practices of respect and trust. The video recordings published in Vimeo provide visual records with unprecedented access to such complex tasks of unpacking the intergenerational knowledge shared from the participants (see Haines, 2016 for the videos). However, the information published online only contains the knowledge permitted by the participants. Similarly, the results suggest that there is strong evidence of interest in intergenerational learning between Indigenous Elders and future knowledge keepers. Therefore, the results point toward the importance of the embodiment of the Elders’ wealth of knowledge and practical skills, which are transmitted through cultural and communal practices, from succeeding generations. The monetary value of this research is relevant to the field of information and is equally necessary for developing ethical research practices for working with Indigenous people.

The results from this study provide empirical evidence for future research on understanding the Ngarrindjeri stories’ resilience against technological changes and the ongoing vulnerability of oral tradition, which relies on the Elder’s ability to pass on their knowledge. Follow-up interviews also need to be conducted with our current research participants. This will ensure the transparency in maintaining that the translated data is truthful. Furthermore, the current results will guide us in improving our data gathering tools and strengthening the community-based participatory iterative framework when conducting ethical practices of working with the Indigenous community. It is anticipated that this knowledge will offer new approaches that will provide a memorandum of understanding that reflects on mutual respect and informed consent. It also integrates collaborative partnership between the researcher and participants in all phases of the research.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the Australian Government's Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship. The authors deeply acknowledge the contributions of the Ngarrindjeri Cultural Mentors, Elders, participants and the Ngarrindjeri Land and Progress Association for welcoming us to the community. We thank anonymous reviewers for their valuable contribution to improving the quality of the paper. Sincere thanks also to Joanne Evans for her comments on this research.

About the authors

Jelina Haines is a PhD student of Information Studies in the School of Information Technology and Mathematical Sciences at the University of South Australia. Her current PhD research interest focuses on Indigenous knowledge journey practices observed during the cyclical process of knowledge creation, synthesis, translation, ethical dissemination and preservation of Elders stories using video dialogue interview. She can be contacted at jelina.haines@mymail.unisa.edu.au

Jia Tina Du is Senior Lecturer of Information Studies in the School of Information Technology and Mathematical Sciences, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia. Tina is also an Australian Research Council (ARC) DECRA Fellow (2017-19). Tina holds a PhD in information studies from Queensland University of Technology, Australia. Her research focuses on understanding the interplay between humans, information and technology, including theories and applications related to user-Web interactions, human information behaviour, and social impact of the Internet. Dr Du can be contacted at tina.du@unisa.edu.au.au

Gus Geursen is an Adjunct Professor of Information Technology and Mathematical Sciences, University of South Australia. Professor Geursen can be contacted at gus.geursen@unisa.edu.au

Dr. Jing Gao is an Associate Professor Learning Technologies & Senior Lecturer School of Information Technology and Mathematical Sciences. Dr. Gao can be contacted at jing.gao@unisa.edu.au

Mrs. Ellen Trevorrow is a Ngarrindjeri Elder and world-renown artist and cultural weaver with over 35 years’ experience and lives and works on Ngarrindjeri country at Camp Coorong. She is the manager of Camp Coorong, Centre for Cultural Education and Race Relations as part of the Ngarrindjeri Land And Progress Association. She also serves on the board of the Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority. Mrs. Trevorrow can be contacted at ellen1955.et@gmail.com

References

- Agrawal, A. (1995). Dismantling the divide between indigenous and scientific knowledge. Development and Change, 26, 413-413.

- Battiste, M. (2005). Indigenous knowledge: foundations for First Nations. World Indigenous Nations Higher Education Consortium-WINHEC Journal. Retrieved from http://multiworldindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/Indigenous-Knowledge-Foundations-for-First-Nations13.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6uCuNz2Qa)

- Beaton, B., Fiddler, J. & Rowlandson, J. (2004). Living smart in two worlds: maintaining and protecting First Nation culture for future generations. In M. Moll & L.R. Shade (Eds.), Seeking convergence in policy and practice: communications in the public interest (Vol. 2; pp. 281–295). Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

- Cruikshank, J. (1994). Oral tradition and oral history: reviewing some issues. The Canadian Historical Review, 75(3), 403-418.

- Delgado, M. (2015). Urban youth and photovoice: visual ethnography in action. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Du, J. T. & Haines, J. (2017). Indigenous Australians’ information behaviour and Internet use in everyday life: an exploratory study. Information Research, 22(1), paper 737. Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/22-1/paper737.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6oGbrpbYB)

- Du, J. T., Haines, J., Sun, V. Q., Partridge, H. & Ma, D. (2015). Understanding indigenous people's information practices and internet use: a Ngarrindjeri perspective. In Proceedings of the 19th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS 2015). Retrieved from AIS Electronic Library.

- Emery, A. R. (2000). Guidelines: integrating Indigenous knowledge in project planning and implementation. Hull, Canada: Canadian International Development Agency. Retrieved from http://www.kivu.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Partnership-Guidelines.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6uCw2FHrf)

- Haines, J., Du, J. T., Geursen, G., Gao, J. & Trevorrow, E. (2017). A visual ethnographic exploration of knowledge creation in the context of Indigenous Elders: a dialogic inquiry. In iConference 2017 Proceedings (pp. 480-490). Available from http://hdl.handle.net/2142/96759 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6uCwHszTZ)

- Haines, J. (2016) Jelina Haines [Vimeo videos]. Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/user59576922 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6uCxMn4S4)

- Haines, J., Du, J T., Trevorrow, E. & Gibbs, J. (2016). Transforming Indigenous learning using a visual ethnographic exploration in understanding Ngarrindjeri Elders knowledge: a narrative inquiry. Australian Association for Research in Education (AARE) Conference. Melbourne, Australia: AARE.

- Haines, J., Du, J. T. & Trevorrow, E. (2015). Indigenous knowledge sharing and relationship building through narrative storytelling and creative activities. Paper presented at Indigenous Content in Education Symposium, 21 September 2015, Adelaide, University of South Australia.

- Henige, D. (2002). Oral, but oral what? The nomenclatures of orality and their implications. Oral Tradition, 3, 229-238.

- Iseke-Barnes, J. (2009). Grandmothers of the Metis Nation. Native Studies Review, 18(2), 25-60.

- Jacquez, F., Vaughn, L. M. & Wagner, E. (2013). Youth as partners, participants or passive recipients: a review of children and adolescents in community-based participatory research (CBPR). American Journal of Community Psychology, 51(1-2), 176-189.

- Joseph, B. (2014). 11 things you should know about Aboriginal oral traditions. Retrieved from http://www.ictinc.ca/blog/11-things-you-should-know-about-aboriginal-oral-traditions (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6uCwfPSak)

- LaVeaux, D. & Christopher, S. (2009). Contextualising CBPR: key principles of CBPR meet the Indigenous research context. Pimatisiwin, 7(1), 1–25.

- Nakata, M. & Langton, M. (Eds.). (2009). Australian indigenous knowledge and libraries. Retrieved from https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/bitstream/10453/19486/1/E-book.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6uCwxJGs7)

- Pink, S. (2013). Doing visual ethnography (3rd ed.). London: Sage.

- Tendi, N., Ngarrindjeri Heritage Committee & Ngarrindjeri Native Title Management Committee. (2007). Ngarrindjeri Nation Yarluwar-Ruwe Plan: caring for Ngarrindjeri sea country and culture. Camp Coorong, South Australia: Ngarrindjeri Land & Progress Association.

- Trafi-Prats, L. (2009). Destination Raval Sud: a visual ethnography on pedagogy, aesthetics, and the spatial experience of growing up urban. Studies in Art Education, 51(1), 6-20.

- Vansina, J. M. (1985). Oral tradition as history. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Warburton, J. & Chambers, B. (2007). Older Indigenous Australians: their integral role in culture and community. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 26(1), 3-7.