‘Us and them’: expert and practitioner viewpoints on small New Zealand community archives

Sarah Welland

Introduction. This article presents one aspect of a wider research project into New Zealand community archives. It focuses on how key aspects affecting community archives (for example, collaboration, digital archiving, and community engagement) are perceived differently by experts and practitioners.

Method. A qualitative research method was used, in two stages. Stage one involved semi-structured interviews and on-site visits with five community archivists. Stage two used three iterative survey rounds of surveys with fifteen experts using the Delphi research method.

Analysis and Results. he nature of community archives continues to be ambiguous to many working in the heritage information and recordkeeping sectors. While expert and practitioner groups had similar perceptions of some areas, they saw others quite differently. These different perceptions may lead to assumptions by each group that propagated notions of ‘us and them’. Reasons for these different perceptions include the community archivists’ community-based focus and their immediate work environment, and the experts’ society-wide focus and greater awareness of industry practice.

Conclusion. Opportunities are needed for these groups to share their different perceptions to help reduce professional and practical misunderstandings. Different perceptions may restrict collaboration within the heritage information and recordkeeping sectors, and hinder the development of community archives and the recognition of their unique role in the archival world.

Introduction

Information professionals in New Zealand demonstrate a range of different and often conflicting perceptions about small community archives, particularly in relation to what these archives do and whether they apply good archival practice. Although a small amount of New Zealand-based research into community archives exists (e.g., Newman, 2010), and there are some practice-based New Zealand examples (e.g., Green and Winter, 2011; Sullivan, 2012), little, if any, of this research addresses general perceptions about community archives from those working with heritage information.

This paper focuses on the different perceptions of community archives by two groups: individuals with day-to-day responsibility for managing a community archives (interviewees), and experts who have a broader archival perspective. It presents part of a wider on-going research project on community archives in New Zealand that focuses on three key areas: the current state of community archives, practice-based concerns, and priority areas for future development (Welland, 2015).

Wider industry perceptions

Although the term community archives is a familiar one to most information professionals, archival discourse implies that the concept behind it is still ambiguous to many. While a key premise of community archives is to ‘give substance to a community’s right to own its own memories’ (Earles, 1998, p. 12), and there also exists a ‘self-conscious sense of curation’ (Long and Collins, 2016, p. 98), it is usual for them to be ‘small, local, independent and oftentimes idiosyncratic’ (Hurley, 2016). This makes it harder for common factors to be identified, especially since collections can range in form from virtual participatory archives to smaller versions of government archives. It can also make it harder to create definitions that clearly outline what community archives are, and what they do (e.g., Gilliland and Flinn, 2013; Jura Consultants, 2009).

Many community archives researchers and writers have tried to define community archives by how they represent, validate or prompt the memory of different facets of culture or society rather than through commonalities in practice or content (for example, Battley, Daniels and Rolan, 2014; Long and Collins, 2016; Paschild, 2012). They can be viewed as places where the community itself takes responsibility for its memories, and where it gets to tell its own stories in its own voice in its own way (for example, Caswell, 2014; Flinn, 2007). They can also be political entities that counteract archival thinking established under traditional, custody-based collecting paradigms, and places where the voices of the marginalised, oppressed, poor or other can be heard. These voices may be perceived as being in direct contradiction to mainstream, published, or known narratives (for example, Cook, 2012; Flinn, Stevens and Shepherd, 2009). However, unless a universally agreed definition arises (which at this stage seems unlikely) the overall concept of community archives will remain one that will ‘depend on where you live’ (Bastian, 2012, p.6). In most respects, this discourse accurately reflects the New Zealand situation.

Method and findings

This paper is based on findings and results from qualitative research carried out in 2015. The purpose of the research was to document some of the different opinions and gaps in understanding about New Zealand community archives between expert and practitioner groups (Welland, 2015). While there was some general industry-based awareness of differences, little specific research had been carried out.

Research involved gathering and analysing data across two stages, and categorising and comparing the findings from each. The first stage used semi-structured interviews with five sole-charge community archivists and an onsite visit to each of their collections. Each collection was carefully chosen to represent a community archive type that was common to New Zealand but which did not rely on government funding. An Iwi (Māori tribe) archives, a local history archives, an interest group archives, a Christian denominational (religious) archives, and a school archives were selected. Collections varied in size from 50 to 1200 linear metres. None of the interviewees had archival qualifications or extensive archival experience and training outside of their current role, although this was not a condition of selection.

Interview questions focused on two themes: how small community archives work and how interviewees view their community archives. Questions covered physical context (where the collection is stored), intellectual context (how the collection is described and managed), user context (who the users are, and how they use the collection), and the interviewee’s personal views on the collection.

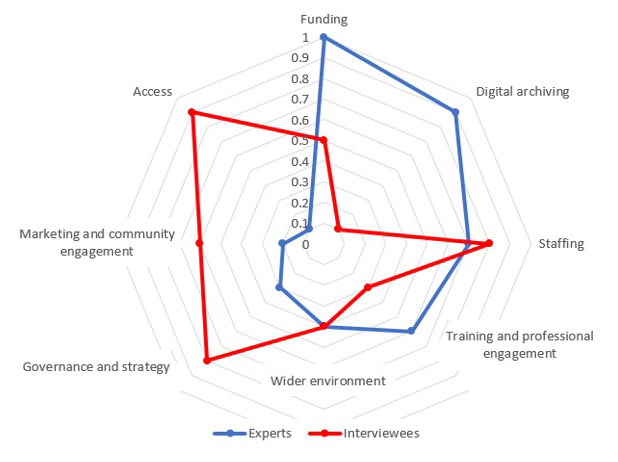

Interviewee transcripts and related on-site notes were organised into conceptual categories (Joe, Yoong and Patel, 2013, p. 917) to aid analysis. This was an iterative process that achieved increasingly precise and specific descriptive categories that related to the current working environments in the archives. In addition, interview comments that indicated worry, frustration, an awareness of lack, or a desire to change the current state were also categorised. (Welland, 2015, p. 14). Table 1 summarises these categories. Figure 1 compares these with the experts data.

| Category title * | Area(s) of perceived concern |

|---|---|

| Access | Providing equitable access to items within the collection. |

| Digital archiving | Addressing low-level and generalised aspects of digital archiving. |

| Funding | Managing within allocated resources. |

| Governance | Raising the governing body’s level of understanding about archives. |

| Marketing and community engagement | Promoting the collection and its holdings. |

| Repository management | Ensuring ‘business as usual’ regarding acquisition, processing, storage and preservation. |

| Staffing | Managing with current staff numbers. |

| Training | Training staff and volunteers. |

| Wider environment | Staying sustainable in the face of impacting business, environmental, political etc. trends. |

| * Note: A number of categories overlap or may be influenced by other categories. This aspect is covered in more detail in the original research. | |

These findings were compared with results and findings from stage two of the research. Stage two involved three rounds of online surveys with fifteen experts using the Delphi research method. Experts were purposively selected from around New Zealand. They had a history of oversight or responsibility for archival management processes in the library, archives or records management fields; held positions of responsibility within professional associations that advocated the management and use of heritage information; and/or had made a noted contribution to professional discourse. Only five had current or past involvement with community archives.

In round one, experts listed five factors they considered would have a major influence on community archives over the next ten years, ranked these factors, and explained their rationale. They also chose one of three responses (agree, disagree, it depends) to sixteen statements provided by the researcher that described possible characteristics of community archives in New Zealand, and gave reasons for each response. In round two, experts agreed or disagreed with rankings associated with eleven categories that summarised the impact factors identified in the previous round. They explained their rationale for any ranking they disagreed with, and suggested an alternative ranking. Experts also agreed or disagreed with the sixteen amended and non-ranked statements about the characteristics of community archives from round one, and suggested additional characteristics. Round three was similar in form, building on round two, and with optional rather than mandatory feedback. Categories and statements from the three rounds of the survey were then analysed and compared with the conceptual categories and statements identified from the interview transcripts and on-site notes.

Table 2 summarises the categories of impact that experts considered would have a major influence on community archives in the next ten years. Figure 1 compares these with the interviewees' data.

| Category title* | Area(s) of perceived impact |

|---|---|

| Access | Providing equitable access to a collection and the items within it. |

| Collaboration | Collaborating with other agencies and organisations. |

| Digital archiving | Collecting, creating, managing, preserving, accessing and using digital content. |

| Funding | Allocating and managing finances. |

| Governance and strategy | Governing the archives, both in terms of management, and in terms of strategy. |

| Marketing and community engagement | Promoting a community archives and its holdings. |

| Staffing | Recruiting and maintaining appropriate numbers of skilled paid or voluntary staff. |

| Standards | Establishing and maintaining rules, standards, frameworks, specifications, guidelines etc. relating to the management of a collection. |

| Training and professional engagement | Training and education of staff, volunteers, stakeholders etc. |

| Wider environment | Sustaining the collection in the light of wider social, cultural, political and environmental influences. |

| * Note: A number of categories overlap or may be influenced by other categories. This aspect is covered in more detail in the original research | |

Using the Delphi research method ensured that that experts’ anonymity could be maintained throughout the process. Although the researcher knew who all the experts were, she did not know which expert provided which responses. This was a key consideration in a country with a small number of researchers and practitioners. Experts were able to submit responses, view summarised findings from the previous round, and keep or change their viewpoints for the next (Yousuf, 2007). Full ethics approval for the current research was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Open Polytechnic of New Zealand.

Discussion

Findings clearly demonstrated that both expert and interviewee groups shared similar views when describing some of the key characteristics of small community archives in New Zealand. These characteristics were:

- Community archives are controlled by a self-defined community. A ‘self-defined’ community is one which Flinn (2007) says, 'defines themselves on the basis of locality, culture, faith, background, or other shared identity or interest'. This was further clarified in the research as genetic and social relationships, and personal identification with a specific culture, ethnic group or race.

- Community archives demonstrate some form of active community participation. This relates to active participation by members of the self-defined community (for example, community members acting as volunteers or support staff) as well as active participation by archives staff in community-related services that may or may not be related to their collection’s mandate. For example, they may store the community’s current or semi-current records or produce the community newsletter.

- They operate either as an in-house repository or as a stand-alone collecting institution. Community archives in New Zealand generally fall into two groups. One operates in-house and is supported and/or governed by an umbrella organisation (for example, a school). The other operates on an independent stand-alone basis (for example, a local history group created, financed and run by volunteers).

- Community archives require users to come to a physical place to access most of the collection. A physical building is still the most common way in New Zealand of storing community memory and providing access to it. Most small community archives have few, if any, descriptions or digitised holdings on the Web, and if they do, these represent only a very small percentage of the overall collection.

- Community archives hold a wide range of items, from archival records to reference material and artefacts. While a collection needs to hold at least some archival records for it to be called a community archives, archival items may make up only a small part of the whole collection.

- Community archives are staffed by one person who does most of the day-to-day work, and who carries most of the day-to-day responsibility. This work is usually carried out on a part-time basis; there are few full-time community archivists in New Zealand.

- Community archives operate with little resourcing. Lack of funding characterises many small community archives in New Zealand, impacting staffing, training, cataloguing and description, and preservation.

Since both groups identified the same key characteristics, it can be inferred that the overall concept of community archives is generally understood by most people working with heritage information in New Zealand, even though an agreed definition has yet to be developed.

However, while experts and interviewees shared a similar overall concept of community archives, analysis showed that they perceived the role and practices of community archives very differently. Three areas where these different perceptions were particularly evident were the role of the community archives, the carrying out of collaborative work, and the prioritisation of areas of concern.

The role of community archives

When it came to the role of community archives, both interviewee and expert groups agreed that community collections played a key part in preserving community memory in New Zealand. However, perceptions differed about how community archives carried out this role across wider society. These differences in perception in such a fundamental area could cause continued confusion about what community archives do.

Expert comments indicated that many viewed the role of community archives from an inclusive perspective. That is, they saw community archives as sharing an archival space that included government and collecting archives and individual and special collections, all of which contributed to the documenting of society.

[Community archives] often pick up material that is missed or 'out of scope' for professional libraries and archives. (Expert comment)

Such comments implied that experts would consider one community archives collection to be more significant than another if they considered the material addressed memory gaps in wider society, rather than just locally. For example, a queer community collection may be considered more archival (or more nationally significant) than a rural local history collection of a similar size, because it is perceived to contain a greater range of unique information.

Conversely, interviewees had a more focused perspective of the role of community archives, founded on perceived community need. Concepts of community involvement, representation, and identity were enmeshed with the need to ensure that a community’s memories were accessible in an equitable and educative way. Interviewees considered the role of the collection to be one of preserving community history, facilitating community access, and bridging community knowledge between back then, now, and the future. They also saw it as supporting other community functions and information needs, such as records storage. For example, the school archives participant noted:

I think [our role is] to provide information... And that's why we need this collection here. We need to have it for when they [users] want photos or when they want things. (Interviewee comment)

For experts, who have a more discipline-focused approach to managing archival collections to aid society-wide understanding and access, the interviewees’ view can lead the experts to assume that community archives staff are unconcerned about the lack of more accepted (or at least widespread) archival practices that would help to maintain the collection.

In my experience training in archival practice is one of the most important factors in ensuring that community archives are managed appropriately. (Expert comment)

However, for many community archivists, this was not a consideration, and even if they were aware of it, some would interpret suggestions by experts for more training in archival practice as unwanted attempts to control what they were doing. A key reason seems to be the society-wide perceptions of experts in contrast to the community-focused perceptions of interviewees. These perceptions are not in themselves wrong, and may reflect established (if not formally articulated) thinking within each group. They may also be inevitable in an information sector that encompasses three very different ways of managing heritage information (libraries, archives and museums). For example, both the expert and interviewee groups often seemed to assume that the other group did not ‘get’ what they did, and that the other group was not interested in finding out more. These perceptions can compromise the development of future solutions for community archives development if one group’s views are not understood by the other.

Collaborating with others

Interviewee and expert perspectives also differed about the perceived value of collaboration, particularly collaboration between community archives and other individuals, groups or institutions. Experts considered that collaborative practices such as shared storage, project work and training would have a significant and positive effect on community archives. Many were conscious of what they saw as the potential benefits of appropriate collaborative practice over the long term, seeing it as lowering costs, enhancing strategic focus, and improving sharing of archival knowledge and experience.

While some experts questioned the level of emphasis that collaboration was given by their group, other experts saw it as a way of helping to address systemic issues around arrangement, description, and preservation, particularly in small collections run by staff with little or no archival training. For example, some experts questioned the ability of small community archives to have processes that demonstrate understanding of key archival theory and practice, particularly in relation to the archival principles of provenance and original order, and appropriate preservation:

… some [community archives] are impeded by a lack of focus, and a clear collection mandate. (Expert comment)

Interviewees however, did not perceive collaboration to be significant in their day-to-day practice. Only one of the interviewees mentioned a collaboration project, which was setting up an agreement with another small heritage institution to scan a few boxes of newspapers. None of the collections had any formal collaboration agreement in place for shared storage or acquisition practices, nor were they considering formal collaboration projects (small or large) in the future. Newman (2011) outlined a similar finding in her research, stating ‘none of the [New Zealand] community archives studied had effectively collaborated with other archives or heritage organisations’. She also suggested that a possible reason was ‘the strong parochialism felt by community archives’ (p. 42).

While interviewees demonstrated a certain parochialism because of their community-focused perspective, their narrow focus was due more to a conditional wariness towards collaboration, rather than any active avoidance of it. For example, one interviewee was agreeable to a form of collaborative storage where holdings were kept by a larger repository, as long as the community didn’t lose ownership of the collection. All interviewees also seemed amenable to collaboration for training and professional guidance purposes. However, they were also cautious about whether collaboration would succeed due to lack of internal resourcing, a perceived lack of support from larger archival institutions, and few relevant and affordable training opportunities outside of main cities.

I [have] been involved with the archives world for … over twenty years now, and … there's a real down the nose approach to community archives. [Laughs], and … there seems also to be a real lack of comprehension from those who are working in well-funded, dedicated institutions … all they do is archives. (Interviewee comment)

Overall, this state of conditional wariness seems to have been heavily influenced by the interviewees’ work environments. While a sole charge position and a perennial lack of resourcing can lead to some ingenious short-term solutions and a measure of independence, these factors can also make it difficult for interviewees to make significant changes over the long term. This, and the interviewees’ own community-focused viewpoint, seemed to create a state where individuals preferred to overlook collaborative practice (and its potential pitfalls from which they felt they might not recover) in favour of in-house projects that they could more quickly and demonstrably protect or control. This also revealed a tendency towards learning from individuals or groups already trusted by the community, rather than taking a risk with someone different.

The different perceptions held by experts and interviewees suggest a lack of understanding around the other group’s archives-related decisionmaking. Consequently, there is a danger that these assumptions could negatively inform any future planning and strategy involving community archives, unless measures are taken to remediate the situation. The perception gap, the small number of people working in the sector, and the growing need to collaborate for advocacy, education, digitisation and funding purposes, raise concerns about the development of community archives and archivists. For example, experts may leave community archivists out of collaborative projects, assuming they would not be interested enough or experienced enough, while community archivists may avoid participating in collaborative projects, assuming they would not be valid for their own work environment.

Prioritisation of areas of concern

While research findings and results demonstrated a variety of opinion between the two groups in many areas, perceptions differed most significantly when it came to areas of concern and/or potential impact on community archives. While experts and interviewees identified similar areas (demonstrated by the eight categories that appear in both tables), they prioritised each area quite differently.

Figure 1 provides a visual representation of how similar areas of concern and/or potential impact are differently prioritised by experts and interviewees. This was gained from analysis of the number of times specific areas of concern were mentioned by interviewees, and the ranked level of importance experts gave to each area that they thought impacted on community archives. Findings were converted into a 10-division scale (0.1 to 1) to better demonstrate equivalences and differences. The higher the number, the greater the level of agreement by all the individuals within the group.

Figure 1: Comparison of priorities for areas of perceived impact or concern: experts and interviewees

There are only two areas where priorities are similar: staffing, and wider environment. All other areas show clear disparity. For example, while both funding and digital archiving were ranked by experts as being in the top five priority areas, they were areas of markedly less concern for interviewees. Interviewees considered marketing and community engagement, governance and strategy, and access as key areas of concern, but these were ranked by experts as areas of lower priority overall.

Discussion of three particular areas: digital archiving, marketing and community engagement, and governance and strategy, illustrates some of the problems these discrepancies cause for community archives and for the heritage information and recordkeeping sectors more generally, particularly for the on-going survival of community collections.

Digital archiving

The area of digital archiving addresses concerns and factors that impact the collection, creation, management, preservation, access and use of digital content in community archives.

Experts considered digital archiving to be a key area of future impact for community archives, second only to funding. Although one third of the expert group questioned its ultimate assigned level of priority (stating that other areas like funding and training and professional engagement would dictate its success or failure), survey results and associated comments demonstrated recognition of the ubiquity of digitised and born digital information. That is, ongoing preservation would need to be managed (at least eventually) by all types of heritage information repository. Experts seemed to have a much wider range of experience in digital archives than interviewees, and consequently their comments showed greater awareness of digital archiving and its associated issues.

Interviewees however, made very few remarks to indicate that digital archiving was a concern, or even a concept they needed to be aware of. Only two of the five interviewees discussed the possibility of a small scale digitisation programme, while the other three talked about digital archiving in terms of appropriate physical storage for video cassettes and CDs. This can be explained to some extent by the interviewees’ working environment. All worked in places where there was little understanding of digital recordkeeping by the governing body, no born-digital items being received, no tools or facilities available to ingest, store or control digital items, and no trained or experienced person to manage digital recordkeeping processes.

…so much is becoming digital and I find that kind of recordkeeping doesn't connect with a lot of other people in the staff… (Interviewee comment)

If experts and interviewees do not have an opportunity to engage with the other group and understand their perspective, it could create ongoing issues concerning the planning and development of digital archiving solutions for community archives. Evidence of this can already be seen in the lack of awareness of digital issues (and possible solutions) by interviewees. It can also be demonstrated by the current lack of accessible, affordable, and relevant documentation on digital archiving that is suitable for most New Zealand community archives.

Marketing and community engagement

Marketing refers to the processes that community archives employ to encourage community interaction with the collection. Community engagement relates to the level of interaction the community has with the archives collection itself.

Both groups agreed that marketing and community engagement was an area of focus, but like digital archiving, they prioritised its level of importance differently. Also, as with digital archiving, there was evidence of disagreement within the expert group. Some viewed it as something that could be improved upon once other issues were addressed, while others saw it as vital for the ongoing survival of the collection. From the expert responses, it was clear that an expert’s own experience influenced how they perceived the motivations behind many of the processes carried out by community archives. For example, one asked why marketing and community engagement would be considered even a priority for community archives when they ‘are likely to be managed within a broader institution such as a library or local museum’ (Expert comment).

Interviewee comments were more consistent in their estimation of the importance of marketing and community engagement. All considered it to be a key area. Interviewees saw themselves as sole representatives of the archival collection to their community, and so they were aware of just how much responsibility they had in this area. They were also cognisant of the importance of positive community attitudes towards the collection, especially when it came to withstanding challenges to its role or its existence. Most interviewees indicated that the lack of community engagement was often due (at least in part) to the community’s misunderstanding of the role and purpose of the collection.

I know that there's a lot of people, even just here in a little place like [town], they don't know anything about archives… (interviewee comment)

The different viewpoints of experts and interviewees indicate that at least some experts underestimated the vital role marketing and community engagement plays in many small community archives. Consequently, any plans to market or advocate community archives from an industry-wide perspective may be unconsciously downplayed by more senior archivists because other concerns are deemed more important. Since the interviewees made it clear that marketing and community engagement is a key priority for most small community archives, they may interpret any perceived reduction in its importance by wider industry as disinterest or unconcern.

Governance and strategy

Governance and strategy comprises the impact of governing bodies on the ongoing development of community archives, particularly as it relates to strategy and associated advocacy.

Although experts recognised its value, they tended to downplay the possibility that it may be a key priority. While one third disagreed with its final placement, they were evenly split between those who wanted it to be given greater priority, and those who wanted it to be given less. For example, some saw other priority areas such as funding and staffing as more important, while others viewed governance and strategy as a key vehicle for addressing these areas. Two-thirds of the experts had no experience working in community archives, which may have also played a part in the variation of opinion. They may have not realised the extent to which a governing body influences the day-to-day workings of a small archival collection.

In contrast, all the interviewees had similar views about the role of the governing body and its level of influence. They voiced many concerns relating to what can happen when a governing body does, or does not, understand the role or purpose of the collection, and emphasised that unless the governing body is supportive, very little will be able to be achieved, no matter how good the strategic planning.

Those people out there that are interested in the Treaty [of Waitangi] claims, they know the value of what's sitting up there. I don't believe the Trustees… do. Because they would never leave that stuff sit there idle, gathering dust. They'd want to protect it for as long as possible, and yet, I've been here… seven years next year, and they're still sitting there… I don't believe that the people that sit around [the Board] table realise what they've got up there [in the collection]. (Interviewee comment)

Interviewees stated that a governing body which understood the role and purpose of the collection was more likely to allocate extra resourcing and advocate the collection to the community. Consequently, interviewees considered the area of governance and strategy to be of key priority, as it had direct impact on how the collection was run, and how it was to survive into the future.

These differences indicate a lack of common understanding regarding the working environment of many community archives, as well as a continuing lack of communication between the two groups. Experts especially will need to gain greater understanding of the role and importance of the governing body in community archives before they are able to contribute appropriately to future initiatives that support and advocate community archives.

Conclusion

Experts and interviewees demonstrated diverse opinion across the heritage information sector. Such diverse opinion needs to be exchanged between, and acknowledged by, each group to avoid the perpetuation of assumptions that could hinder the ongoing development of community archives. Left unresolved, the communication gap between the two groups is likely to lead to a continuation of different assumptions that could ultimately hinder ongoing development in areas that need wider industry collaboration or support.

Comments from both groups also imply that the work of small community archives can be interpreted as reactive, localised and protective. While these ways of working can help community archivists survive day-to-day pressures in what is commonly a sole-charge environment, it can also make it harder for them to respond to internal or external change, or to ask for help from those outside of the community. Likewise, the experts’ society-wide focus can exclude aspects of community archives-related thinking from archival discourse, feeding the illusion that community archives have nothing to offer archival theory or practice. Without cross-group communication, the experts’ focus can lead to the development of umbrella solutions that do not reflect or fit the unique working context of community archives, since they are more likely to be in the national and large archival institutions that develop such solutions. Umbrella solutions give rise to perceptions by those working within community archives that the providing these solutions are out of touch or elitist.

Each group’s assumptions about the other creates a perception induced barrier that can make it more difficult for effective communication to take place. While there is high-level recognition of the nature and importance of New Zealand community archives from those working with heritage information in other parts of the information sector such as public libraries, very little collaborative discussion or interaction currently exists between information professionals and community archivists working in smaller collections. This lack of existing communication seems to exacerbate perceptions of exclusivity between those working in community archives, and those working in archival institutions elsewhere.

Any workable long-term solutions may be dependent on the level to which industry professionals in the different heritage information sectors are willing to go to recognise the different perspectives of community archives, and to advocate their value. The onus of responsibility, at least initially, may need to be on a small group of dedicated individuals, because many of those working in community archives do not have the resources, time, contacts or knowledge to do it.

One solution for New Zealand is to establish a forum where community archivists and other industry professionals meet and share perspectives on community archives. This will help other industry professionals understand issues and solutions from the perspective of the community archivist. It will also help community archivists to identify and apply relevant knowledge they may previously have been unaware of. Such a forum needs to be carried out in a face-to-face environment (at least initially) to establish the beginnings of a trusted network of individuals and institutions. It could then become a foundation for further information sharing and communication initiatives benefitting community archives, such as an online community, an advocate group, and an online toolkit (Welland, 2016).

Dedicated, ongoing communication between the different information heritage sectors will help New Zealand community archives take their place as representatives of community memory in an environment that, to date, has been chronically under-funded, under-educated and under-appreciated. However, the lack of any support structure or professional community for community archivists means that this suggestion remains a suggestion. There is currently no identifiable organisation or group that can establish the forum and coordinate such efforts, which has its own set of issues.

Regardless of how (or even whether) solutions are created, a demonstrated willingness by wider industry to listen to, collaborate with, and share information with, community archivists would go a long way towards breaking down group-based perceptions of us and them, and consequently to create a more productive environment for the development of community archives.

About the author

Sarah Welland is a lecturer at the Open Polytechnic of New Zealand, teaching records, archives, and information management. She has extensive experience in New Zealand’s recordkeeping industries, and received the inaugural Ian McLean Wards Scholarship in 2013 for research into community archives. Her current research is exploring other aspects of community archives and community heritage information. She can be contacted at sarah.welland@openpolytechnic.ac.nz

References

- Bastian, J. (2012). Putting the archivist into community archives (or not). Presentation at Unpacking the Digital Shoebox Symposium: InterPARES, Feb 17, 2012. Retrieved from http://www.interpares.org/display_file.cfm?doc=aca-ubc_symposium_2012--bastian_2-4.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6u5tIQVqU).

- Battley, B., Daniels, E., & Rolan, G. (2014). Archives as multifaceted narratives: linking the ‘touchstones’ of community memory. Archives and Manuscripts, 42(2), 155–157.

- Caswell, M. (2014). Toward a survivor-centered approach to records documenting human rights abuse: lessons from community archives. Archival Science, 14,(3–4), 307–322.

- Cook, T. (2012). Evidence, memory, identity, and community: four shifting archival paradigms. Archival Science, 13(2-3), 95–120.

- Earles, K. (1998). Community archives: introduction. South Africa Archives Journal, 40, 10-15.

- Flinn, A. (2007). Community histories, community archives: some opportunities and challenges. Journal of the Society of Archivists, 28(2), 151–176.

- Flinn, A., Stevens, M., & Shepherd, E. (2009). Whose memories, whose archives? Independent community archives, autonomy and the mainstream. Archival Science, 9(1-2), 71–86.

- Flinn, A. (2011). Archival activism: independent and community-led archives, radical public history and the heritage professions. InterActions: UCLA Journal of Education and Information Studies. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9pt2490x

- Gilliland, A. & Flinn, A. (2013). Community archives: what are we really talking about?. In L. Stillman, A. Sabiescu, and N. Memarovic (Eds.), Nexus, Confluence, and Difference: Community Archives meets Community Informatics: Prato CIRN Conference Oct 28-30 2013. Melbourne, Australia: Centre for Community Networking Research, Centre for Social Informatics, Monash University.

- Green, S., & Winter, G. (2011). Looking out and keeping the gate open: Wairarapa Archive, New Zealand’s greatest little archive. Aplis, 24(1), 23–31.

- Hurley, G. (2016). Gordon Dodds Prize: community archives, community clouds: enabling digital preservation in small archives. Archivaria, 81, 129 – 150.

- Joe, K., Yoong, P., & Patel, K. (2013). Knowledge loss when older experts leave knowledge-intensive organisations. Journal of Knowledge Management, 17(6), 913-927.

- Jura Consultants. (2009). Community archives and the sustainable communities agenda: final report. Midlothian: Museums, Libraries, Archives Council. Retrieved from http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20111013135435/http:/research.mla.gov.uk/evidence/view-publication.php?pubid=949

- Long, P., and Collins, J. (2016). Affective memories of music in online heritage practice. In J. Brusila, B. Johnson, and J Richardson, (Eds.), Memory, space and sound (pp 96 – 116). London: Intellect.

- Newman, J. (2010). Sustaining community archives. (Master’s Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand). Retrieved from http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/handle/10063/1398

- Newman, J. (2011). Sustaining community archives. Aplis, 24(1), 37–45.

- Pashchild, C. (2012). Community archives and the limitation of identity: considering discursive impact on material needs. The American Archivist, 75, 125–142.

- Sullivan, E. (2012). Impact of the February 2011 aftershocks: revisiting our heritage collections. Archifacts, October 2011 to April 2012, 73-92.

- Welland, S. (2015). The role, impact and development of community archives in New Zealand: a research paper. Retrieved from https://repository.openpolytechnic.ac.nz/handle/11072/1752

- Welland, S. (2016). The role, impact and development of community archives in New Zealand. In J.W. Arns (Ed.), Annual review of cultural heritage informatics 2015 (pp. 185-202). Lanham, MD: Altamira Press.

- Yousuf, M. I. (2007). Using experts’ opinions through Delphi technique. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation: A Peer-Reviewed Electronic Journal, 12(4), 1–8.