Crying mothers mobilise for a collective action: collaborative information behaviour in an online community

Jisue Lee and Ji Hei Kang.

Introduction. This research examines how members of an online community, MissyUSA, effectively used a virtual venue to pursue a collective action in response to a South Korean marine accident, the Sewol Ferry disaster, on April 16, 2014.

Method. Researchers retrieved posts, including keywords, relevant to The New York Times advertisement campaign, a targeted collection action, in the bulletin boards at MissyUSA. Researchers downloaded 260 threads including posts and their replies posted for fifteen days from April 16 to April 30, 2014.

Analysis. For qualitative content analysis, the researchers used a codebook built upon a Burnett’s typology of information exchange in virtual communities and also took a grounded theory approach to identify emergent types of information behaviour. Two researchers reviewed all 260 threads separately, compared coding results, and then consolidated any differences through discussion.

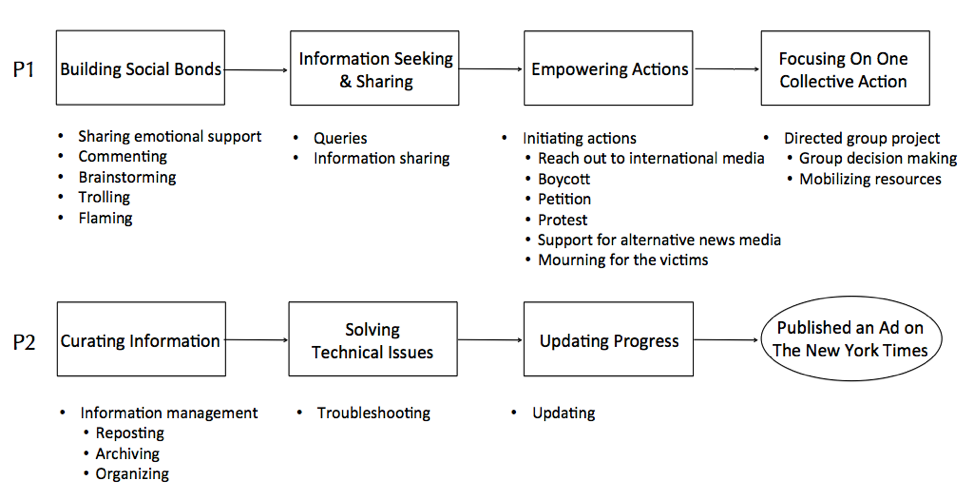

Results. Seven collaborative activities were identified from the two phases. The types of information behaviour that facilitated those collaborative activities were described along with examples. An expanded typology of information behaviour was provided.

Conclusions. Findings from this research expanded the existing typology, providing emergent types of collaborative information behaviour that promote The New York Times advertisement campaign, such as group decision making, mobilising resources, commenting, information sharing, initiating actions, information management, troubleshooting, and updating.

Introduction

Increasingly, more individuals have easy access to a wide spectrum of social movements in their everyday lives. Using evolving information communication technologies allows networked individuals to quickly communicate and share information, mobilise resources, and participate in collective actions and movements (Chadwick, 2006; Dahlgren, 2005; Papacharissi, 2002; Shirky, 2011). Online communities are conventional and convenient platforms where individuals can engage with others as they build relationships and interact on a regular basis (Rheingold, 1993). This study looks at how South Koreans used an online community to achieve a collective action activated by one tragic marine incident in 2014.

On the morning of April 16, 2014, the South Korean Ferry, Sewol, sank with over three hundred passengers, most of them high school students heading to Jeju Island for a four day field trip.

As the ferry sank, only 172 out of 476 passengers, including crew and a captain, were rescued. The South Korean government failed to conduct initial rescue operations for the remaining passengers in a timely manner (Kee, Jun, Waterson, and Haslam, 2017). For hours, scenes of the ferry Sewol capsised and sinking with hundreds of high school students wearing life vests, were broadcast live through domestic media, shocking the general public (Woo, Cho, Shim, Lee and Song, 2015). People’s deep resentment instantly triggered various collective actions that lasted for the next three years. Ultimately, unsolved questions regarding the disaster and the culpability of the Park administration brought about the President’s impeachment on March 10, 2017 (Griffiths and Han, 2017). After Park’s impeachment and the passage of nearly three years, the ferry was raised, and the bodies of four out of nine missing passengers were recovered and identified (Chae, 2017; Kim, 2017). As of June 2017, the accident had resulted in 299 dead, five missing, 172 rescued, and a search for the remaining passengers was ongoing (Lee, 2017; Kim, 2015).

Immediately after the tragedy on April 16, 2014, outraged South Koreans, both inside and outside of the country, organized and participated in a series of petitions and demonstrations against the Park administration. One of the ways Korean-Americans and Koreans residing in the United States responded to the sinking was to put full-page advertisements in major news media outlets, such as The New York Times and The Washington Post. Although the South Korean government controlled much of the local information flow through the domestic mainstream media, these serial advertising campaigns increased awareness of the sunken ferry tragedy internationally and led to a call for rigorous investigation and updates (Cho, 2014; Seo, 2014; Han, 2014). Members of the largest online community for Korean women living in the United States, MissyUSA, successfully achieved this collective action and placed the first full-page advertisement on Mother’s Day, May 11, 2014, in The New York Times. This campaign from the MissyUSA community triggered various civic engagements, including serial advertising campaigns; petitions for establishing a Sewol Ferry Act; protests against the South Korean government; boycotts against the mainstream domestic news media; and sponsorship for alternative investigative news media.

This research examines how MissyUSA members efficiently utilised this virtual communication venue to mobilise a collective action, the New York Times advertisement campaign, in a very short amount of time (fifteen days immediately following the ferry’s sinking) and describes the types of information behaviour and collaborative activities they engaged in during the campaign.

Literature review

This research examines how ordinary online community members became actively involved with a public and political affair and rapidly achieved a collective action through their community. To ground the study, the researchers explore concepts and related research on collective actions in online communities and collaborative information behaviour, as well as offering background information about the online community of MissyUSA.

Collective actions in online communities

The advancement of information and communication technologies, such as the Internet, e-mail, mobile phones and social networking services, drastically changed the way in which the general public communicate and collaborate. The networked individuals in greater groups easily communicate with one another, expand information access, participate in open discussion and information exchange, build online communities and easily mobilise resources for various political engagement and participation (Papacharissi, 2002; Dahlgren, 2005; Hara and Huang, 2011; Lian and Grue, 2017). Among the many types of political engagement and participation, collective actions can be broadly defined as ‘actions undertaken by individuals or groups for a collective purpose, such as the advancement of a particular ideology or idea, or the political struggle with another group’ (Postmes and Brunsting, 2002, p. 290). The spectrum of collective actions includes persuasive actions, such as letter writing, lobbying, and petitioning, as well as confrontational ones, such as individual or collective demonstrations, rallies, blockage, or sabotage. Since the 1990s, the Internet has provided a novel vehicle for supporting and/or complementing offline collective actions, while creating online equivalents such as online petitioning, website defacement, virtual blockages, sit-ins, denial of service attacks, and site hijacking (Postmes and Brunsting, 2002; Hara and Huang, 2011). In particular, the pivotal attributes of the Internet and neighbouring technologies for accomplishing collective actions are in mass communication and mobilisation, as they fundamentally enhance connectivity amongst participants (Postmes and Brunsting, 2002; Bimber, Flanagin and Stohl, 2012).

Researchers from political science and sociology disciplines have emphasised the roles of pre-existing networks, social ties, and physical organizations as social movement organizations to examine a particular group’s creation of political actions and opportunities (McAdam, Sampson, Weffer, and Macindoe, 2005). However, this phenomenon can also be viewed from the information science perspective, which investigates connected individuals’ collaborative activities and their adoption and management of their chosen technology platforms (Hara and Huang, 2011). With respect to the particular roles of information and communication technologies, Bennett and Segerberg articulated the concept of connective action as a large scale, intentional collective action created by digitally networked individuals without relying on central lead organizations and claimed that digital technologies function as ‘organizing agents’ (Bennett and Segerberg, 2012, p. 752).

Recent research investigating informal mass communication and decentralised mobilising structures by online communities demonstrates how activists use their own websites and social media platforms to disseminate extensive information without relying on traditional mass media (Almeida and Lichbach, 2003; Pang and Goh, 2016). Hara and Estrada (2005) describe how members of online discussion forums capitalise virtual resources of knowledge, credibility, interpersonal interactions, and both personal and group identity support. After Hurricane Katrina, individual bloggers emerged from a loose digital network to mediate various offline collective actions toward the recovery of the city (Ortiz and Ostertag, 2014). Similarly, activists with limited budgets may take advantage of raising funds though crowd-funding campaigns, much like Turkish activists did during protests in 2013 (See the Indiegogo campaign for publishing an advertisement in the New York Times). Other collective actions across the world exemplify how social and digital media users can coordinate and collaborate for online and offline actions, such as gatherings and protests for the Spanish Indignados, the Occupy Wall Street movement in the United States, or the Umbrella movement in Hong Kong (Auduiza, Cristancho and Sabucedo, 2014; Thorson, et al., 2013; Earl, Hurwitz, Mesinas, Tolan and Arlotti, 2013; Lee and Chan, 2016). Building on previous studies focusing on the various roles and functions of online communities, research examining sets of collaborative information behaviour will enhance our understanding of freely networked citizens’ online political communication and collective actions.

Collaborative information behaviour

Information behaviour refers to the aggregate of human behaviour that actively or passively seek and use information (Wilson, 2000). It has been nearly a century since research regarding information behaviour emerged (Case, 2012; Spink, 2010). Until the 1960s, the early studies focused more on the artefacts and venues of information, such as books, TV broadcasts, and newspapers. By the late 1970s, investigations turned to a person’s gratifications (Case, 2012) and activities to find and obtain information (Kasemsap, 2015). The number of studies on human behaviour interacting with information has grown rapidly since its inception in the 1980s. Starting with Wilson’s model (1981), a number of models and theories have been published in this field (Case, 2012). However, the foci of studies predominantly explored the individual level of information behaviour (Hertzum, 2008; Shah, Capra, and Hansen, 2014).

The field of collaborative information seeking emerged later and underwent a fundamental shift (Shah, 2012) with the rapid development of computer-mediated communication and computer supported cooperative work. Collaborative information seeking has stimulated various research dimensions. For example, researchers have attempted to investigate various collaborative information behaviour patterns, such as co-searching (Hyldegård, 2006; Morris and Horvitz, 2007), co-browsing, collaborative navigation, social searching or collaborative filtering (Romano, Nunamaker, Roussinov, and Chen, 1999). Space and time aspects of information behaviour have also been studied (Shah, 2012). In addition, some researchers have devoted attention to explaining particular contexts for information behaviour and created an information model by combining multiple research results (Golovchinsky, Pickens, and Back, 2009; Shah, 2012). Whereas relationships between people and laboratorial systems are well known, little is known about how social environments from everyday life, such as online communities or social networking sites, can encourage and support people's interactions and collaborations. Therefore, studying collaborative information behaviour in various online communities will provide insightful and practical findings to distinguish best practices for people to interact and collaborate (Shah, 2012).

MissyUSA as an information ground

Fisher (1999), developed the concept of information grounds to explain social settings where people share information about their daily lives. Fisher proposed information grounds as places temporarily created by people who come together for a specific purpose, such as clinics, hair salons, metro buses, restaurants and coffee places; yet, people share information spontaneously and serendipitously. That is, while attending to a focal activity, people share information intentionally or unexpectedly (Fisher, Landry, and Naumer, 2007). Information grounds can form anywhere at any time, and information flow is a by-product therein. In earlier studies, an information ground meant a physical environment; however, more recent studies have suggested that online as well as mobile spaces can be information grounds that connect people, places and information. Counts and Fisher (2010), for example, found that a mobile social networking system, Slam, acted as a social ecosystem and information ground, and Narayan, Talip, Watson, and Edwards (2013) argued that social media also played pivotal roles as information grounds.

MissyUSA is the largest online community for Korean women living in the United States and Canada (Lee, 2013; Yun, 2006). This website is an online community to share members’ wide range of thoughts, experiences, information, and knowledge about living in the United States. Most members are students, wives of students, working women, and/or married to Americans, representing diverse age groups, socio-economic statuses, and lifestyles (Lee, 2013). Whereas previous researchers’ interests in this community have been focused on topics of health and communication (Lee, 2013; Yun, 2006), this research investigates how MissyUSA members utilise their community as an information ground as well as how they leverage it as a virtual information organization for targeted collective action.

Considering the previous research findings and gaps discussed above, this research examines the New York Times advertisement campaign led by MissyUSA community members, the first formal citizens’ collective action regarding the Sewol ferry disaster. Particularly, the researchers investigate a series of collaborative activities conducted by the members and identify how particular information behaviour patterns support and facilitate those activities, which result in an influential action beyond simple communication.

Research questions

The purpose of this study is to explore and understand the types of collaborative activities and information behaviour that online community members engage in to pursue a collective action. Two research questions are investigated:

Research Question 1: What collaborative activities and information behaviour did online community members participate in to achieve the targeted collective action (i.e., the New York Times advertisement campaign)?

Research Question 2: How did their particular information behaviour facilitate collaborative activities to achieve the targeted collective action?

Methods

Data collection

This research focuses on identifying the types and patterns of activities and information behaviour that members of an online community socially and collaboratively engage with others to purse a targeted collective action, the New York Times advertisement campaign. From April 16 to 30, 2014 (for fifteen days), MissyUSA members talked about the breaking news of a sinking ferry, incubated a collective action, and conducted a crowd-funding campaign to complete the New York Times advertisement campaign. Therefore, the researchers retrieved and collected threads including keywords (The New York Times, NYT, campaign, news articles) which were posted in those fifteen days. From May 20 to June 10, 2014, the researchers obtained memberships, logged in to the community site, and retrieved the relevant threads for data analysis. A thread included an original post and its replies. The 283 threads were downloaded and saved in PDF format for further analysis. After excluding the 23 erroneous posts and replies (e.g., corrupted threads; 8.13%), the researchers analysed the data set of 260 threads.

Given the characteristics of public discourse in online communities (Rafaeli, 1996), obtaining informed consent from the community members was waived by the Institutional Review Board at Florida State University. For data analysis, any identifiable information on the participating members was removed from both the collected posts and replies to maintain privacy and confidentiality.

Content analysis

The content analysis in this study includes 1) identifying the collaborative activities that members of this online community engage in to mobilise for a targeted collective action, the New York Times advertisement campaign, and 2) describing and classifying the variety of information behaviour that members perform while participating in major collaborative activities. The researchers used the existing typology of information exchange in virtual communities (Burnett, 2000), which examines the range of activities undertaken by participants in a specific virtual community. By categorising both informational and social interaction, Burnett (2000) maintained that both information-oriented exchanges (such as announcements, queries and requests for information, and replies to such queries and requests) and diverse social activities (including the exchanges of pleasantries, gossip, and jokes, as well as active emotional support) were used in online environments to exchange information. He also argued that a specific community can have a different flavour, meaning that there are particular norms, expectations, and acceptable behaviour patterns within the community, which called for developing multiple typologies by studying multiple virtual communities (Burnett, 2000; Burnett and Buerkle, 2004). Therefore, we used Burnett’s typology to test it with a specific virtual community, MissyUSA, as well as to contribute to creating an expanded typology representing a richer variety of information behaviour on online communities.

As this research particularly focused on examining collaborative information behaviour for a collective action, the researchers excluded non-interactive information behaviour, such as lurking (i.e., passively reading rather than writing) from Burnett’s typology (2000). Instead, the researchers endeavoured to delve into more diverse and specified types of interactive information behaviour with an emphasis on achieving a targeted collective action. While using Burnett’s typology, the researchers also took a grounded theory approach to identify newly emerged information behaviour from the dataset. As a result, this study provides an expanded typology of interactive information behaviour built upon Burnett’s.

Inter-coder reliability

Two researchers separately reviewed the 260 threads to identify the major collaborative activities the members engaged in. By using Burnett’s typology (2000) and a grounded theory approach, types of interactive information behaviour were constantly compared and coded, while emergent codes of information behaviour were added to the codebook. After reviewing all 260 threads, the researchers compared coding results and consolidated the differences through discussion. For valid interpretation of content and indirect member checking, researchers carefully cross-checked domestic and international news media reports based on interviews with MissyUSA members who participated in the New York Times advertisement campaign (, 2014; Park, 2014; Kang, 2014).

Results

The New York Times advertisement campaign consisted of two major phases as shown in Table 1. In the thirteen days of phase 1, from the day the Sewol ferry sunk on April 16 to April 28, MissyUSA members began expressing grief, frustration and anger against the South Korean government. They also shared news reports created from both domestic and international news media to gather accurate information. They then decided to initiate the New York Times advertisement campaign to increase awareness of this tragic incident outside of Korea and also to ask the South Korean government for a thorough investigation. They quickly mobilised various resources to design and draft the advertisement, consulted with lawyers about legal issues, and negotiated the prices and available dates with major newspaper companies. During phase 1, the New York Times advertisement campaign as a group project was incubated, and a total of 106 threads were created.

As soon as members completed final negotiations with The New York Times, they instantly started a crowd-funding campaign through a web platform (Indiegogo.com), titled 'Full Page NYT Denouncing the South Korean Government'. The targeted amount for this advertisement was $58,213 ($52,030 to place the ad and a $6,243 PayPal transaction fee). In the two days of phase 2, April 29 and 30, the campaign easily exceeded the target, and a total of 154 threads were created during this phase. The campaign lasted until May 9, 2014 and the total of 4,129 backers ultimately raised $160,439 (276% of the targeted amount).

| Phase | Description | Number of threads | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | The period (13 days) when the New York Times advertisement campaign as a group project was incubated and began to run. | 106 | 16-28 April |

| Phase 2 | The period (2 days) during which a crowd-funding for the New York Times advertisement campaign began and ended. | 154 | 29-30 April |

Major collaborative activities and information behaviour found in each phase are described below. During phase 1, members began building social bonds, engaged in information seeking and sharing, and initiated empowering actions. They then started the New York Times advertisement campaign as a direct group project within the community. In phase 2, whilst conducting a crowd-funding campaign, they curated information, solved technical issues, and updated progress. By identifying specific types of information behaviour and providing good examples of each, the researchers explain what specific information behaviour types MissyUSA members engaged in and how those information behaviour types effectively facilitated major collaborative activities for their collective action. Quotes in single quotation marks were translated directly from Korean to English. The number of the post that the direct quote came from is shown in parentheses. Additional explanation is added in the brackets.

Types of collaborative activities and information behaviour in phase 1

Building social bonds.

The MissyUSA members who were horrified by the breaking news of the Sewol ferry sinking were primarily Korean mothers of young children. They immediately began talking to one another in the community about this unexpected disaster and shared information, as well as feelings. Although not every member participated in this activity, the like-minded members exhibited strong solidarity and bonded by sharing emotional support and commenting.

Sharing emotional support. In the first few days following the April 16 sinking, little information was available to the public, and information from mainstream media and relevant government authorities such as Korea Coast Guard was quickly revealed to be false. For instance, mainstream media outlets (such as MBC, MBN, and YTN) broadcast that all students from the Danwon High School had been rescued about 11 am. However, this rapidly turned out to be a false report. The Sewol completely sank at about 11:20 am with 304 passengers, mostly the Danwon High School students trapped in cabins (Kee, Jun, Waterson and Haslam, 2017). While desperately waiting for updates about the government’s rescue activities, MissyUSA members continuously posted to express their feelings of sadness, frustration, and anger against the South Korean government:

Most of those children [trapped in the cabins of the sinking ferry] are only children. How can their parents live without them? ㅠㅠㅠㅠㅠ [a widely used emoticon using the Korean alphabet to shape how tears come from closed eyes]. (Post 2958).

Another post revealed anger and frustration:

I am so pissed off about how this crazy psycho [Ex-President Geun-hye Park] took advantage of a poor little girl [a six-year-old who survived alone after losing her entire family in the ferry]. Park brought this panicked girl from the hospital only to broadcast nice footage of her meeting the victims… It is truly a shame, but, we have to let the entire world know this is what the South Korean government is doing right now [instead of directing rescue operations]. (Post 19893).

Commenting. When one member wrote a post describing how desperately she had tried to make sense of the accident and control her grief and anger, others replied to her post by commenting. Most comments displayed agreement and support, but some did not (as discussed below). In particular, members expressed their agreements with the original post by typing a repeated Arabic number in their replies: ‘222222222, wow, you had a great point here, I agree that we need to let international news media know about this tragedy’ (in the first-level reply to Post 2918); ‘33333333333333333’ (in the second-level reply to the first-level reply to Post 2918). In this way, members expressed their agreement in replies, which allowed for counting the number of members who agreed with the post and for visualising their expressed solidarity.

Brainstorming. For the first few days, members mainly engaged in sharing emotional support (both positive and negative feelings), and commenting, but then they quickly moved to talking about how they could collectively respond to this tragedy. One suggested that community members should be alert to filtering out the false information controlled by the South Korean government and acquire more credible information from The Associated Press or The New York Times:

We must be keen… look at the reports from The AP or The New York Times… because the South Korean government controlled the information flow, the public might have not had access to credible information. (Post 1642).

Another member suggested building a separate website outside of Korea to safely collect, curate, and provide credible information to international news media (Post 3771).

Trolling and flaming. However, not every member in the community participated in sharing and building social bonds. Some deliberately wrote hostile posts to disapprove other members’ discussion and conversation and to elicit flames from more established community members. When irritated members talked about impeaching the president, one left this trolling comment, ‘impeaching president? You must have been watching too many TV shows and you really think you can do so in real life? Haha’ (Post 1659). Most members politely responded to this trolling by saying that democratic societies allow the people to impeach disqualified political leaders, and very few left flaming comments.

Information seeking and sharing.

As the public began to strongly question the credibility of the information being released by the South Korean government and domestic media (Cho, 2014), members started to seek and share news reports from international media, which were considered more credible and less biased than domestic media. Additionally, members actively asked questions and offered answers to help with each other’s information needs. In this manner, they collaboratively sought and shared information, which resulted in filtering out wrong information and rumours as well as educating themselves.

Queries. When members had information needs, they actively posted queries to seek information, advice, and/or feedback. Their information needs varied. Some examples include:

How is the focus of international news media changing? I saw this post saying Korean domestic news media started simply scapegoating cabin crews to wrap up this turmoil, instead of criticizing the government's inability to rescue passengers. International media seemed to take this perspective in their reports, too. Is this some sort of a rumour or trolling? Or is it really true? Does anyone have more information about this? (Post 3651).

To the author of this post, I would like to vote for the questionnaire you mentioned in the post. The news article said there was a questionnaire at the bottom. However, I can’t find it. Could you help me with this? (in the first-level reply to Post 4174).

Information sharing. When MissyUSA members saw queries posted, they proactively answered and shared information to fulfil others’ information needs and requests. To answer the question of Post 3651, one member replied:

I don't think so. I heard radio news this morning saying that Korean people were outraged about the inability of President Park and the Park administration, while the government particularly criticized the captain and crew members who abandoned the ferry. I live in New Jersey and this is what I got this morning. (in the first-level reply to Post 3651).

The responses to the query from the first-level reply to Post 4174 were posted in the second-level reply: ‘Go all the way down to the bottom of the article, you see the questionnaire there, I just voted’ and ‘the questionnaire is between the news article and its replies’ (in the second-level reply to Post 4174). In addition, members searched for international media reports covering the ferry tragedy written from different perspectives than those of the South Korean media. When finding such reports from well-known international news media outlets, members fetched and shared them along with links, by copy-pasting in the MissyUSA community. Some members even distributed those reports and links outside the community by using other social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and KakaoTalk (the most popular instant messaging application in South Korea) to spread credible information sources to greater groups of readers. These information seeking and sharing activities were conducted with an emphasis on mutual information seeking, searching, filtering, and sharing to fulfil their information needs.

Empowering actions.

Initiating actions. While continuing to seek information and share, members began to offer suggestions to initiate persuasive and confrontational actions at a group level. During this period, among several actions suggested, some were taken and developed into local campaigns. Some of the major actions initiated are described below.

Reach-out to international news media. As they lost trust in the South Korean mainstream media, members resorted to well-recognised international news media. Members actively sent e-mails to ask mainstream news media in the United States, England, Germany and other countries, to send reporters to South Korea for additional reporting along with leaving comments and replies to forums in the websites of those outlets:The South Korean media have been controlled by the government for so long. When dictators Jung-hee Park and Doo-whan Jeon suppressed civilians, only international news media told the truth’ (Post 4421), and

international news media have more impact on the South Korean government and domestic media than we expect. We must express our opinions against Geun-hye Park’ (Post 4579).

Actions for boycott, petition, and protest. Members also initiated calls to boycott or cancel subscriptions to biased domestic mainstream media including the Korean Broadcasting Systems, Chosun-ilbo, Joongang-ilbo, and Donga-ilbo and refused to purchase products made by the companies that advertised in those media. In addition, members started petitions urging the impeachment of President Geun-hye Park and pressuring the U.S. president not to visit Korea. Groups of members from multiple states organized demonstrations, such as picketing and setting memorial altars for victims in front of the Korean Consulate buildings and shared their photos and stories in the community. Members communicated through the community and participated in local protests together.

I went to the demonstration in front of the Korean Embassy in D.C. I will attend another demonstration this Thursday (at the Korean Embassy in D.C., 04/24, 12PM). If you are interested in joining, reply to this post or e-mail me. I will organize a car pool for our transportation as well as the KaKaoTalk meeting room for further communication. Please dress in black color and bring a yellow ribbon or picket sign. Let us console the families of victims' grief by getting together here in the United States. (Post 4479).

Another member posted a photo of the memorial altar with candles, flowers, and sticky notes set in front of the Los Angeles Consulate. The sign on the right corner of the altar says, ‘hoping for miracles’ (Post 4553). Figure 1 shows the embedded photo in Post 4553.

Support for alternative news media. In addition, MissyUSA members started campaigns to support alternative independent online news media, such as Newstapa, Gobal News and Media Mongu, whose reports reasonably challenged the mainstream media and the South Korean government. Members shared the detailed information about how to donate to these alternative media using PayPal accounts and direct links to donating pages.

Mourning the victims. Meanwhile, members continued to express their grief and sadness for the victims and their families by creating and sharing the yellow ribbon images both inside and outside of the community. In hopes of rescuing the victims or finding missing persons from the sunken ferry, members created and shared various yellow ribbon images featuring the slogan of ‘a small movement for a great miracle’ (Post 4942). Figure 2 shows the image of one of the yellow ribbons created and shared in Post 4942.

Figure 2: A yellow ribbon image with the text ‘a small movement for a great miracle’

Focusing on one collective action: the New York Times advertisement campaign.

Directed group project. Among the many actions suggested and taken up within the community, members decided to focus on one collective action as a directed group project. This was to place an advertisement in one of the most prominent international mainstream media outlets in the United States. This directed group project aimed to increase awareness of the sunken ferry tragedy internationally and to call for rigorous investigation regarding the Park administration’s inappropriate handling of the disaster (Cho, 2014; Seo, Kim, and Dickerson, 2014). While conducting this directed group project together, members engaged in a series of subsequent information behaviour.

Group decision-making. Some members undertook leadership roles to manage group decision-making. When collecting ideas on how to design and draft the advertisement, they used the community as a town hall to hold online meetings. When a leading member wrote a post asking for the group’s comments on a specific topic, other participants quickly voiced their opinions by providing comments and votes for or against within their replies. After communicating with each other about the particular subject, the leading member who initiated the original post summarised the group’s collective decisions and made official announcements to provide closure to their virtual meetings.

This is one of the many designs created for the New York Times advertisement campaign. I am sharing the updated design based on the comments you left in replies. I mostly incorporated your comments into the revisions except those that were not accurate. I am done with revising this design for now. Thank you all for your help and time. Everyone who participated in creating this design owns the copyright of this work, so feel free to use and distribute it. (Post 7427).

Mobilising resources. Upon starting a directed group project, members voluntarily took on leadership roles in various tasks: graphic designers, copywriters, and public relations managers designed and drafted the advertisement; lawyers took part in reviewing legal issues that the advertising campaign might have faced; Korean-Americans fluent in English proof-read other members’ posts and/or e-mails being sent to international news media and/or other social networking services.

As most ordinary members continued to work on designing the advertisement, some leading members negotiated with the mainstream newspaper companies, and eventually reached a final agreement on the advertising fee and several possible dates for publication in The New York Times. On April 29, the group quickly started the crowd-funding campaign through the online platform, Indiegogo.com, to raise the advertising fee ($58,213). In less than two days, the campaign had successfully collected the target amount. Major collaborative activities in phase 2 included curating information, troubleshooting, and updating status.

Collaborative activities and information behaviour in phase 2

Curating information.

Information management. After sharing the post on the crowd-funding campaign on the bulletin board, including a full description and the URL to the fundraising site, members wanted to pin the original post so that it could be shown to the community members right away. However, the group did not have access to administrative privileges for managing the posts. Therefore, they came up with several ways to efficiently manage information.

Reposting. To keep the original post on the very first page of the bulletin board, members manually reposted the original post, including the instructions and the URL to the campaign site:

While I was writing a reply to this post, the original post was being deleted. Here I am copying the post and reposting it. Referring to the previous post, you can sign up for Indiegogo.com and pay by PayPal to participate in the funding campaign. The total that we have to collect is around 90,000 dollars. If 100 people join this campaign, one person needs to pay 900 dollars. If 1,000 people join it, one person needs to pay 90 dollars. If 10,000 people join it, one person needs to pay 9 dollars. This is the easiest thing we can do now. Please participate in the campaign. (Post 8612).

Given the multiple time zones in the United States, members in different zones voluntarily took turns reposting the original post to keep the campaign active around the clock:

I am reposting this post again before my lunch time is over. Anyone, please repost this again so that this original post can stay on the first page (Post 9220_2).

In addition to posts related to crowd-funding, members continuously reposted others’ posts that were worth re-sharing within the community, such as information about how to support alternative independent news media in South Korea (Post 8235)

.Archiving. Given the ephemeral nature of online communication, members saved certain posts by capturing screenshots or copying their content. In the first reply to Post 5021, one member said that she had copied that post in case it was deleted soon after she had read it.

Organizing. For more efficient communication, members tried to use keywords in brackets such as [repost], [to leading members], and [announcement] for easy retrieval and classification of posts.

Solving technical issues.

Troubleshooting. After the crowd-funding campaign was posted at Indiegogo.com, members quickly reported back to the community any technical issues they found in the campaign platform. For instance, because of the sudden excessive traffic, the site temporarily went down. When multiple members reported this fact, leading members quickly identified the problem and solved it so that the campaign could go on. While troubleshooting these technical issues, leading members simultaneously updated community members with their progress.

[Leading member] Announcement about the updated payment for the New York Times advertisement campaign (content added). I just called PayPal out of impatience. I requested again that PayPal unblock our campaign account since I sent all documentation needed. Now it is unblocked. The campaign account is linked to the Indiegogo campaign site. Thanks, those who supported us by paying by credit card. I would appreciate if you participate in the campaign by using PayPal. (Post 9166).

Also, members voluntarily asked questions and provided answers to help others who had difficulties in using the online crowd-funding platform:

Some senior lady asked for the information about how to send her money order to this crowd-funding campaign. Leading members, please help! (Post 9224)

Updating progress.

Updating. As soon as the crowd-funding campaign opened, members continuously updated the fundraising status, including number of participants and amount of money raised. In Post 9166, where a leading member shared the announcement of the crowd-funding campaign, many participating members left comments to let others know of their participation as well as the status of the campaign:All of our family members participated in the campaign. I appreciate everyone’s participation. More than 370 participants already have funded this campaign!’, and

I just participated in it too! We have collected $21,705 now! (Post 9004).

In Post 9113 members shared their excitement by saying,

for the last 12 hours, two-thirds of our targeted fund was already collected. I see our advertisement in The New York Times is coming for sure, and

I just did it too. [Now the sum is] $43,935’.

With serial updates of the number of participants and amount of funds in the community, the campaign successfully collected the target amount ($58,213) in less than 48 hours after launching.

Figure 3 displays the sequence of collaborative activities and sets of significant information behaviour related to each collaborative activity from both phases 1 and 2.

Figure 3: Collaborative activities and types of information behaviour in phase 1 and 2

Discussion

We have examined how members of MissyUSA used their online community to quickly mobilise resources and accomplish a targeted collective action, the New York Times advertisement campaign. While members participated in a series of collaborative activities, they engaged in various types of information behaviour that effectively facilitated those activities. Using the existing typology of information exchange in virtual communities (Burnett, 2000), the researchers excluded non-interactive information behaviour, such as lurking, to focus on examining more specific types of interactive collaborative information behaviour observed from written posts and replies.

As a result, the researchers realised that most existing types of information behaviour from Burnett (2000) effectively described members’ informational and social oriented interactions. However, the researchers were able to identify more specific types of information behaviour which further streamlined the direct group project, such as group decision-making and mobilising resources. The researchers also identified commenting, information sharing, initiating actions, information management, troubleshooting and updating. Some emergent types, such as information sharing, initiating actions, and information management, include multiple subordinate types. These emergent types of information behaviour clearly represented MissyUSA members’ unique norms, expectations, and acceptable behaviour patterns as they achieved the targeted collective action. By applying Burnett’s typology to analyse activities in the MissyUSA community, the researchers not only validated most interactive information behaviour types, but also learned that each information behaviour type could be assigned and supplemented with additional descriptive commentaries reflecting each community’s characteristic, shared interests or goals and the nature of the members’ interactions. Table 2 shows an expanded typology of information behaviour and code, including existing types from Burnett and newly found types from the MissyUSA community.

| Information behaviour type (Code) | Description | Sub-type (Code) |

|---|---|---|

| Flaming (HF) | A hostile act of online ad-hominem argumentation, aiming neither for logic nor for persuasion, but purely and bluntly intended as insult. | |

| Trolling (HT) | A hostile act of one deliberately posting a message for the purpose of eliciting an intemperate response among more established community members. | |

| Commenting (CM)* | An act of commenting on original posts and/or replies on multiple levels. A comment to the original post is a first-level reply. Another user commenting on a first-level reply is a second-level reply. | |

| Emotional support (ES) | An act of expressing emotions for precisely defined groups of users and/or specific issues. This includes positive (e.g., consolation, gratitude, happiness, solidarity, encouragement, etc.), negative (e.g., anger, frustration, etc.), and neutral emotions. | |

| Queries or Specific request for information (QU) | An act of asking questions or submitting queries made by other community members; queries presented to the community both in the posts and its replies. | |

| Information sharing (IS)* | An act of deliberately sharing certain posts, such as news reports, created by mainstream and/or alternative news media, along with URLs, and/or answering specific queries and requests to share information. | |

| Initiating actions (IA)* | An act of initiating actions for community members to solve problems, or support group decision-making. | Reach out to international news media (RM)*, Boycott (BC)*, Petition (PE)*, Protest (PT)*, Support for alternative media (SA)*, Mourning the victims (MV)* |

| Directed Group Project (DGP) | An act of conducting more concrete group projects designed to support the interests and information needs of the community. Intended to have an impact on the world outside the community, to make information available that may not otherwise be easily accessible to community members, or to instigate or support political activities. The New York Times advertisement campaign was established as a directed group project in this online community. | Group decision-making (GDM)*, Mobilising resources (MR)* |

| Information Management (IM)* | An act of intentionally managing information by clustering, classifying, archiving certain posts and/or using keywords and titles in the subject lines. | Reposting (RP)*, Archiving (AR)*, organizing (OG)* |

| Troubleshooting (TS)* | An act of solving technical issues related to maintaining the fundraising website, reporting and fixing issues, helping others fix technical issues while participating in the fundraising campaign, etc. | |

| Updating (UP)* | An act of updating/broadcasting the current status of fundraising to the community. | |

| Note. This table was adapted from a typology of information exchange from Burnett (2000). The sign of (*) denotes a newly emergent code of information behaviour. | ||

In the separate sections below, the researchers provide detailed discussion of the emergent types of information behaviour and their implications.

Development of collective identity and solidarity

Immediately after the ferry sank, anxious members started expressing and sharing emotional support in the community while waiting for news updates from South Korea. Most members, as mothers of young children, became deeply empathetic and personalised the sorrow and anger of parents who lost their children in the sunken ferry disaster. Collective identity consists of ‘agreed upon definition of membership, boundaries, and activities for the group’ whereas individual identity consists of ‘wholly personal traits that are... internalised and imported to social movement participation as idiosyncratic biographies’ (Laraña, Johnston, and Gusfield, 1994, p. 15). This simple, but comforting, activity of sharing emotions for the first few days greatly contributed to building a shared collective identity as ‘mothers who have and raise their own children’ and strong solidarity to quickly initiate any collective actions.

By creating posts and commenting in the community, members shared both positive (consolation, encouragement) and negative (sorrow, anger, and frustration) emotions, and their peculiar practice of expressing agreement by typing Arabic numbers in replies (11111, 22222, etc.) effectively visualised their agreement, consent, and solidarity. Receiving replies (Joyce and Kraut, 2006; Rafaeli and Sudweeks, 1997), and receiving positive feedback and emotional support from other members (Black, 2005; Pfeil, Zaphiris, and Wilson, 2009) are factors that influence a poster’s continued participation and increases the sustainability of an online community. The activities of sharing emotional support and commenting helped them to ‘validate their personal and group identity’ as mothers (Hara and Estrada, 2005, p. 507) and build moral engagement and solidarity to quickly move on to the next steps of brainstorming and initiating various collective actions. While deciding to conduct the New York Times advertisement campaign as their directed group project, community members also accomplished some substantial actions suggested from brainstorming activities. These actions, such as boycott, protest, supporting alternative news media, continued to grow even after the New York Times advertisement campaign. This shows that many other collective actions were being practically incubated from members’ activities of brainstorming and initiating various actions. These very specific information behaviour types for initiating actions may be transferrable to similar research on collective actions and social movements in online communities.

Collaborative information behaviour facilitating a directed group project

As the South Korean government and mainstream media provided limited and censored information, perplexed members actively sought and shared more accurate and credible information created by international news media. Through asking questions and sharing information, they searched for and brought international news reports to the community, made sense of, and assessed the quality and relevance of the information together. It is important to see that members shared not only the objective information they found, but also their own understandings and interpretations of the information (Harper and Sellen, 1995; Hansen and Järvelin, 2005). Specifically, members sought and collected information from various sources outside of the South Korean government and domestic mainstream media, assessed the credibility of the information, and filtered out rumours and trolling as a way of mutual problem solving and collaborative sense making. These patterns of co-searching, co-browsing, collaborative navigation, and collaborative filtering are some representative examples of collaborative information behaviour observed in previous research (Hyldegård, 2006; Morris and Horvitz, 2007; Romano, Nunamaker, Roussinov and Chen, 1999). In addition, as media exposure increases political knowledge, and thereby affects political participation, such as voting and protesting (Corrigall-Brown and Wilkes, 2014; Eveland and Scheufele, 2000), these collaborative information seeking and sharing activities assisted MissyUSA members to build a solid communal knowledge and to incubate and then initiate their directed group project, the New York Times advertisement campaign.

When focusing on the New York Times advertisement campaign as a collective action, some leading members and a majority of the ordinary members actively engaged in group decision-making and mobilising resources. To design and draft the advertisement together, when a leading member opened up a post, members shared their opinions by commenting in replies. After the group discussion ended, the leading member would report the group’s important decisions in detail and make official announcements to close their meeting. While engaging in open discussion, members voluntarily mobilised their various expertise and skills to finish tasks. For example, graphic designers, copywriters, and public relations managers designed and drafted the advertisement while lawyers provided free consulting services. Through this group decision-making and mobilising resources, members achieved great transparency and accountability in spite of having no formal organization. When starting a crowd-funding campaign in phase 2, members continuously updated the progress of the campaign on the community website. Members’ timely updating not only shared campaign status, but also allowed them to exchange their joy and gratitude and harden their solidarity within the community.

Enhancing information and digital literacy

Having neither a separated bulletin board, nor administrative privilege in the community, members of MissyUSA came up with their own strategies for efficient information management: organizing, archiving, and reposting posts within the community. They tried to use structured and controlled keywords in text and embedded brackets in the subject line of posts for easy retrieval and classification. Also, members attempted to archive posts in case they were deleted. However, the most efficient information management strategy was observed when the crowd-funding campaign started. Members constantly took turns to repost the original post, including the instructions and the URL of the crowd-funding campaign site. By doing so, members separated the most important posts from the many non-relevant posts in the bulletin board and kept the most important post on the very first page. Paul and Morris (2011, p. 24) found similar behaviour in their collaborative web search study and labelled it ‘prioritising information’ behaviour that supports collaborative sense making. The strategies created by MissyUSA members increased their information literacy in terms of creation, retrieval, organization, and management of posts and efficiently facilitated the communication of and participation in the New York Times advertisement campaign.

In addition, the housewives at MissyUSA, especially those who were not fluent in English and lacked experience using the Internet and social networking services, took advantage by quickly asking for the information they needed and troubleshooting issues at hand. For example, when the crowd-funding campaign went up, members started posting questions and queries about how to use credit cards or PayPal to send donations. With prompt responses and comments from the community, they quickly had their information needs fulfilled, could troubleshoot issues and participated in the fundraising. Members voluntarily helping each other to solve the technical issues resulted in an early completion of the fundraising in less than two days. This shows that networked computer environments can offer great potential for developing individuals’ information and digital literacy in the course of seeking and sharing information, troubleshooting problems, and expanding lifelong learning opportunities.

From an information ground to a virtual informal organization for collective actions

The online community, MissyUSA, was originally created for Korean women to share information about and experiences with living in the United States. Topics ranged from information about how to apply for driver’s licenses and green cards; reviews of legal offices or hospitals; to shopping tips and celebrity gossip. Although the site allows a wide variety of topics, the most popular sections are about cooking and motherhood (Lee, 2013). The research on this particular community has been focused on health and communication (Lee, 2013; Yun, 2006). However, when saddened and panicked mothers in the community started talking about the sunken ferry disaster, they not only shared additional information about the terrible accident, but also opened up an opportunity to participate in a collective action. This study is the very first investigation to examine MissyUSA members’ political communication and participation. In this sense, their online community was transformed from a simple information ground, where members obtained information as a by-product, into an actual information organization for collective political actions. As recent studies have tested and discovered how mobile social networking systems and social media platforms can serve as information grounds (Counts and Fisher, 2010; Narayan, Talip, Watson and Edwards, 2013), this study also shows how an online community can serve members’ shared goals beyond the community’s pre-defined purpose. Further research examining how individuals not only obtain serendipitous information, but can also easily mobilise civic engagement and political participation by Internet and adjacent social technologies, will extend the boundary of research on information grounds and users’ collaborative information behaviour therein.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the keywords for limiting the topical scope regarding the New York Times advertisement campaign (The New York Times, NYT, campaign, and news articles) may not include an exhaustive list of relevant keywords. Therefore, the collected posts that included these keywords may not cover the entire process by which this collective action was initiated and developed. In addition, for the first few weeks after the ferry sank, there was a turmoil of trolling and attacking MissyUSA members by outsiders who were assumed to be extreme rightists known from Ilbe, an online community that embraces ‘the irrational hatred for liberalism/progressivism, hostility towards people from certain regions in South Korea, and intense misogynies’ (Kim, 2012, para. 2). Some posts were deleted without posters’ permission, and the server was down for a couple of days for no reason, which quickly stirred up the community and generated confusion among members. This vulnerability influenced members’ creation and deletion of posts as well as researchers’ retrieval and collection of the posts.

Secondly, according to the purpose of this research, the researchers attempted to classify the types of information behaviour related to a series of collaborative activities in phase 1 and 2, which resulted in creating an expanded typology of information behaviour. However, the assignment of information behaviour codes was conducted at the general individual thread level (i.e., the original post and its first level replies). Considering that an individual thread has different depth and length of information and contexts (e.g., multi-level commenting in replies, numbers of comments and speed of commenting, etc.), further in-depth analysis for second and third level replies as well as contextual and/or discourse analysis may result in identifying other types of collaborative information behaviour.

Conclusion and thoughts on future research

This research examined how ordinary online community members in the United States utilised their virtual communication venue, engaged in various collaborative activities and information behaviour, and achieved a collective action to promptly respond to a political affair, the Sewol ferry disaster in South Korea. By analysing MissyUSA members’ communication and interaction using Burnett’s typology (2000), the researchers not only tested the effectiveness of existing typology with this particular online community, MissyUSA, but also identified various emergent information behaviour types that facilitated crucial collaborative information activities for their collective action, the New York Times advertisement campaign.

- This research verifies how sharing emotions and commenting assisted members to quickly build a collective identity and solidarity as mothers and allowed them to move onto the next steps of initiating actions and participating in various subsequent actions, such as reaching out to international news media, boycott, petition, protest, supporting alternative news media, mourning the victims.

- This research shows how members engaged in collaborative information seeking and sharing behaviour to collect accurate information from various international news media, assess the relevance and credibility of the information, and filter out rumours and trolling as a way of collaborative sense making by asking questions and sharing information.

- For their chosen directed group project, the New York Times advertisement campaign, group decision-making and mobilising resources streamlined the process of group communication and resource mobilisation, as well as increased transparency and accountability.

- Members also developed their own strategies to effectively manage and curate information within the community: they organized posts by using certain keywords and brackets in the subject headers of posts, archived important posts and replies, and reposted certain posts to prioritise the most important information and sits exposure to members.

- Their prompt troubleshooting of technical errors of the crowd-funding site and updates of funding status allowed them to accelerate the speed of the crowd-funding campaign, which completed its fundraising in less than two days.

- Finally, this research provides a strong example of how loosely networked individuals can come together for a cause and transform an online community from a simple information ground into a powerful virtual organization, capable of implementing effective collective actions.

The identification and description of emergent information behaviour types in this study are significant because they contribute to the creation of an expanded typology that describes a wider spectrum of collaborative information behaviour in online communities. Considering that people’s information behaviour patterns evolve continuously, studying diverse online communities and conducting comparative analyses of multiple typologies should be continued and encouraged to accurately describe and understand various types of information behaviour and their implications.

To continue our interests in general citizens’ political communication and participation, the researchers intend to conduct individual and/or group interviews with MissyUSA members who participated in the New York Times advertisement campaign and perform quantitative analyses to further examine relationships between the certain types and frequencies of information behaviour.

About the authors

Jisue Lee, an adjunct professor in the School of Information at Florida State University, received her PhD in Information Studies from Florida State University and MA in Library and Information Science from Yonsei University, South Korea. Her research interests lie in how connected individuals engage in collaborative information behaviour with others for political communication, deliberation, decision-making, and collective actions in social movements through information and communication technologies. She can be contacted at noranjin@gmail.com

Ji Hei Kang is an assistant professor at the Department of Library and Information Science at Dongduk Women’s University, South Korea. She is interested in understanding how information specialists perceive innovations and advancements in technology. Dr. Kang serves as a member of ‘The Digital Library Committee of the National Library of Korea.’ She can be contacted at: jhkang@dongduk.ac.kr

References

- Aktihanoglu, M. (2013). Full page ad for Turkish Democracy in Action. Retrieved from https://www.crowdfundinsider.com/2013/06/16612-full-page-ad-for-turkish-democracy-quickly-crowdfunds-on-indiegogo (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zJIq4BiL)

- Almeida, P.D. & Lichbach, M.I. (2003). To the internet, from the internet: comparative media coverage of transnational protest. Mobilization, 8(3), 249-272.

- Auduiza, E., Cristancho, C. & Sabucedo, J.M. (2014). Mobilization through online social networks: the political protest of the indignados in Spain. Information, Communication & Society, 17(6), 750-764.

- Bennett, W.L. & Segerberg, A. (2012). The logic of connective action. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 739-768.

- Bimber, B., Flanagin, A.J. & Stohl, C. (2012). Collective action in organizations: interaction and engagement in an era of technological change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Black, R.W. (2005). Access and affiliation: the literacy and composition practices of English-language learners in an online fanfiction community. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 49(2), 118-128.

- Burnett, G. (2000). Information exchange in virtual communities: a typology. Information Research, 5(4). Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/5-4/paper82.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zJJ25t4W)

- Burnett, G. & Buerkel, H. (2004). Information exchange in virtual communities: a comparative study. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 9(2). Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2004.tb00286.x [Unable to archive.]

- Case, D.O. (2012). Looking for information : a survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behaviour (3rd. ed.). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group.

- Chadwick, A. (2006). Internet politics: states, citizens, and new communication technologies. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Chae, S.H. (2017, March 22). South Korea raises ferry that sank in 2014 disaster. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/22/world/asia/south-korea-ferry-sewol.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zJJ85lAY)

- Cho, C. (2014, May 12). Korean-Americians blast Park for failed Sewol rescue operation. Korea Herald. Retrieved from http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20140512001574 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zJLRAls2)

- Choi, H.J. (2014, April 30). http://www.webcitation.org/6zJLT33vb. OhmyNews. Retrieved from http://www.ohmynews.com/NWS_Web/View/at_pg.aspx?CNTN_CD=A0001985789 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zJLT33vb)

- Corrigall-Brown, C. & Wilkes, R. (2014). Media exposure and the engaged citizen: how the media shape political participation. Social Science Journal, 51(3), 408-421.

- Counts, S. & Fisher, K.E. (2010). Mobile social networking as information ground: a case study. Library & Information Science Research, 32(2), 98-115.

- Dahlgren, P. (2005). The Internet, public spheres and political communication: dispersion and deliberation. Political Communication, 22(2), 147-162.

- Earl, J., Hurwitz, H.M., Mesinas, A.M., Tolan, M. & Arlotti, A. (2013). This protest will be tweeted. Information, Communication & Society, 16(4), 459-478.

- Eveland, W.P. & Scheufele, D.A. (2000). Connecting news media use with gaps in knowledge and participation. Political Communication, 17(3), 215-237.

- Fisher, K.E. (1999). The role of community health nurses in providing information and referral to the elderly: a study based on social network theory. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada.

- Fisher, K.E., Landry, C.F. & Naumer, C. (2007). Social spaces, casual interactions, meaningful exchanges: 'information ground' characteristics based on the college student experience. Information Research, 12(2), paper 291. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/12-2/paper291.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zYbObNji)

- Godbold, N. (2005). Beyond information seeking: towards a general model of information behaviour. Information Research, 11(4), paper 269. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/11-4/paper269.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zYbXKPbp)

- Golovchinsky, G., Pickens, J. & Back, M. (2009). A taxonomy of collaboration in online information seeking. Retreived from https://arxiv.org/abs/0908.0704 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zJJUxmJe)

- Griffiths, J. & Han, S. (2017, March 12). Park impeachment: bittersweet victory for families of Sewol ferry victims. CNN. Retrieved from http://edition.cnn.com/2017/03/11/asia/south-korea-park-impeachment-sewol-ferry/index.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zJJYDxfq)

- Han, J. (2014, May 16). Another ferry ad to run, this time in the Washington Post. Korea Times. Retrieved from http://www.koreatimesus.com/another-ferry-ad-to-run-this-time-in-the-washington-post/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zJJczrw7)

- Hansen, P. & Järvelin, K. (2005). Collaborative information retrieval in an information-intensive domain. Information Processing & Management, 41(5), 1101-1119.

- Hara, N. & Estrada, Z.C. (2005). Analyzing the mobilization of grassroots activities via the internet: a case study. Journal of Information Science, 31(6), 503-514.

- Hara, N. & Huang, B.Y. (2011). Online social movements. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 45(1), 489-522.

- Harper, R. & Sellen, A. (1995). Collaborative tools and the practicalities of professional work at the international monetary fund. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems (pp. 122-129). New York, NY: ACM Press/Addison-Wesley Publishing Co.

- Hertzum, M. (2008). Collaborative information seeking: the combined activity of information seeking and collaborative grounding. Information Processing & Management, 44(2), 957-962.

- Hyldegård, J. (2006). Collaborative information behaviour - exploring Kuhlthau’s Information Search Process model in a group-based educational setting. Information Processing & Management, 42(1), 276-298.

- Joyce, E. & Kraut, R.E. (2006). Predicting continued participation in newsgroups. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(3), 723-747.

- Kang, H.S. (2014, May 12). Interview with a participant of the New York Times advertisement campaign. Kang Hyeshin's Today US [Audio podcast]. Retrieved from http://www.todayus.com/?p=84622 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zJKbjl9s)

- Kasemsap, K. (2015). Theory of cognitive constructivism. In M.N. Al-Suqri & A.S. Al-Aufi (Eds.), Information seeking behaviour and technology adoption: theories and trends (pp. 1-321). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Kee, D., Jun, G.T., Waterson, P. & Haslam, R. (2017). A systemic analysis of South Korea Sewol ferry accident – striking a balance between learning and accountability. Applied Ergonomics, 59(Part B), 504-516.

- Kim, D.S. (2017, June 20). Ministry wraps up first part of search for Sewol victims. The Korea Herald. Retrieved from http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20170620000824 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zJJp9WaX)

- Kim, M.H. (2012, October 29). Politics in Ilbe. The Hankyoreh 21. Retrieved from http://h21.hani.co.kr/arti/society/society_general/33194.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zJKABcOq)

- Kim, S.K. (2015). The Sewol ferry disaster in Korea and maritime safety management. Ocean Development & International Law, 46(4), 345-358.

- Laraña, E., Johnston, H. & Gustfield, J.R. (1994). New social movements: from ideology to identity. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Lee, E. (2013). Formation of a talking space and gender discourses in digital diaspora space: case of a female Korean immigrants online community in the USA. Asian Journal of Communication, 23(5), 472-488.

- Lee, E. (2017, June 5). Remains found in Sewol-ho ferry confirmed as missing passenger Lee. The World on Arirang. Retrieved from http://www.arirang.com/News/News_View.asp?nseq=204861 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zJK1KyAa)

- Lee, F.L.F. & Chan, J.M. (2016). Digital media activities and mode of participation in a protest campaign: a study of the Umbrella Movement. Information, Communication & Society, 19(1), 4-22.

- Lian, O.S. & Grue, J. (2017). Generating a social movement online community through an online discourse: the case of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis. Journal of Medical Humanities, 38(2), 173-189.

- McAdam, D., Sampson, R., Weffer, S. & Macindoe, H. (2005). There will be fighting in the streets: the distorting lens of social movement theory. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 10(1), 1-18.

- Morris, M.R. & Horvitz, E. (2007). SearchTogether: an interface for collaborative web search. In Proceedings of the 20th annual ACM symposium on User interface Software and Technology, Newport, Rhode Island (pp. 3-12). New York, NY: ACM. Retrieved from https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/wp-content/uploads/2007/01/searchtogether.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zYiMzwj3)

- Narayan, B., Talip, B.A., Watson, J., & Edwards, S. (2013). Social media as online information grounds: a preliminary conceptual framework. In Shalini R. Urs, Jin-Cheon Na and George Buchanan, (Eds.). Digital Libraries: Social Media and Community Networks. Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Asia-Pacific Digital Libraries, ICADL 2013, Bangalore, India, December 2013. (pp. 127-131). Cham, Switzerland: Springer Verlag. Retrieved from https://eprints.qut.edu.au/72813/6/72813a.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zYtpbY3W)

- Ortiz, D.G. & Ostertag, S.F. (2014). Katrina bloggers and the development of collective civic action: the web as a virtual mobilizing structure. Sociological Perspectives, 57(1), 52-78.

- Pang, N. & Goh, D.P.C. (2016). Are we all here for the same purpose? Social media and indiviualized collective action. Online Information Review, 40(4), 544-559.

- Papacharissi, Z. (2002). The virtual sphere: the Internet as a public sphere. New Media Society, 4(1), 9-27.

- Park, H. (2014, September 3). All South Koreans are potential passengers in Sewol Ferry. The Hankyoreh. Retrieved from http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/society/society_general/654138.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zJKOgdFz)

- Paul, S.A. & Morris, M.R. (2011). Sensemaking in collaborative web search. Human–Computer Interaction, 26(1-2), 72-122.

- Pfeil, U., Zaphiris, P. & Wilson, S. (2009). Older adults’ perceptions and experiences of online social support. Interacting with computers, 21(3), 159-172.

- Postmes, T. & Brunsting, S. (2002). Collective action in the age of the Internet: mass communication and online mobilization. Social Science Computer Review, 20(3), 290-301.

- Rafaeli, S. (1996). How do you get a hundred strangers to agree? Computer-mediated communication and collaboration. In Harrison, T.M. and Stephens, T.D. (eds), Computer networking and scholarly communication in the twenty-first-century university (pp. 115-136). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Rafaeli, S. & Sudweeks, F. (1997). Networked interactivity. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 2(4). Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/jcmc/article/2/4/JCMC243/4584410 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zYdgUx31)

- Rheingold, H. (1993). The virtual community: homesteading on the electronic frontier. Reading, MA: Addision-Wesley.

- Romano, N.C., Nunamaker, J., Roussinov, D. & Chen, H. (1999). Collaborative information retrieval environment: integration of information retrieval with group support systems. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences. 1999. HICSS-32. (10 pages). New York, NY: IEEE.

- Seo, J-E. (2014, May 13). Park’s critics run an ad in N.Y. Times. JoongAng Ilbo. Retrieved from http://mengnews.joins.com/view.aspx?aId=2989058 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zJKQB8zR)

- Seo, J.Y., Kim, W. & Dickerson, S.S. (2014). Korean immigrant women's lived experience of childbirth in the United States. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 43(3), 305-317.

- Shah, C. (2012). Collaborative information seeking: the whole greater than the sum of all. New York, NY: Springer.

- Shah, C., Capra, R. & Hansen, P. (2014). Collaborative information seeking [guest editors' introduction]. Computer, 47(3), 22-25.

- Shirky, C. (2011). The political power of social media: technology, the public sphere, and political change. Foreign Affairs, 90(1), 28-41.

- Spink, A. (2010). Information behaviour: an evolutionary instinct. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

- Stein, M. (2004). The critical period of disasters: insights from sense-making and psychoanalytic theory. Human Relations, 57(10), 1243-1261.

- Thorson, K., Driscoll, K., Ekdale, B., Degerly, S., Thompson, L.G., Schrock, A., Swartz, L., Vraga, E.K. & Wells, C. (2013). Youtube, Twitter and the Occupy Movement: connecting content and circulation practices. Information, Communication & Society, 16(3), 421-451.

- Wilson, T.D. (2000). Human information behaviour. Informing Science, 3(2), 49-56. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tom_Wilson25/publication/270960171_Human_Information_Behavior/links/57d32fe508ae601b39a42875/Human-Information-Behavior.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zYbh577l

- Wilson, T.D. (1981). On user studies and information needs. (1), 3-15

- Woo, H., Cho, Y., Shim, E., Lee, K. & Song, G. (2015). Public trauma after the Sewol Ferry disaster: the role of social media in understanding the public mood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(9), 10974-10983.

- Yun, H. (2006). The creation and validation of a perceived anonymity scale based on the social information processing model and its nomological network test in an online social support community. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA.