The development of legal capability through information use: empirical findings, along with methodological and practical challenges in a mixed methods study

Fiona Brown and Kirsty Williamson

Introduction. Legal capability includes knowledge, skills, and attitudes required to deal effectively with the law. Paper explores whether legal information use can develop legal capability of legal self-helpers, using concepts emerging from Kuhlthau’s research and the dialogic approach, mixed methods lite, while considering theoretical and practical challenges.

Method. Within an interpretivist/constructivist framework, an online questionnaire collected quantitative and qualitative data from 90 legal self-helpers. Sixteen semi-structured interviews collected qualitative data from a purposive sample selected from questionnaire respondents.

Analysis. Quantitative data were analysed in Survey Monkey. Qualitative survey data were analysed with the interview data, using constructivist grounded analysis techniques to identify codes and themes, and undertake within-case and cross-case analysis, assisted by NVivo software.

Findings. Sixty percent found the information easy to understand, flagging a problem with content. Only six interviewees were satisfied with their information. Most pointed to inadequacies: of detail to enable decision making, a clear process to follow, and content to address fears and stress, and to develop confidence.

Conclusion. Presently, legal information is of limited assistance to legal self-helpers. Information use research, using mixed methods lite, proved effective for evaluating development of legal capability. Power of social media, in meeting challenges of attracting research participants, was notable.

Introduction

How does the public use online public legal information (legal information), how useful do they find it to solve legal problems, and does legal capability develop through this process? A study, undertaken in Victoria (Australia), has explored these issues. The focus of this paper, which is based on the study, is on the human information behaviour of legal self-helpers as they involve themselves with online information. Legal self-helpers are defined as individuals who, without assistance of legal professionals, are making decisions or undertaking legal tasks, including self-representation in courts.

Legal information (provided principally by government and public legal service providers) aims to support legal self-help by developing the legal capability of individuals. Legal capability has been defined as the ‘knowledge, skills and personal attitudes and characteristics’ that a person needs to deal effectively with the law and is considered to be the key determinant of legal action (Coumarelos et al., 2012, p. 44). The concept of legal capability, which was mapped in 2011, recognises that the abilities required by a legal self-helper vary according to the complexity of a legal matter (Collard, Deeming, Wintersteiger, Jones and Seargant, 2011). To develop any kind of legal capability, information users need to understand and apply information to solve a legal problem and perform legal tasks. They also need to derive confidence from the information to be empowered to engage with legal processes effectively and to undertake legal action on their own. The concept of legal capability therefore has information use at its heart.

This paper has three strands. The first focusses on key empirical findings regarding legal capability, as they emerged from the study. The second addresses theoretical issues relating to methods choices, particularly those associated with mixed methods approaches. The mixed methods literature presents significant challenges because of the multiplicity of perspectives on offer as well as their complexity. The third strand relates to the practical challenges of implementing the chosen methods. The story of these challenges, both methodological and practical, could be helpful to other researchers. The study was supported by four key Victorian legal service providers.

Significance of the study

Legal self-help is important because, in general, only the richest and poorest members of the community are likely to have access to professional legal services, leaving the majority, the missing middle (Australian Government Productivity Commission, 2014, p. 20), with only the option of self-help when a legal need arises. This is because of the high cost of private legal services and the strict means testing for public legal services. In order to close the gap, legal information aims to develop the legal capability of users.

In common law countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada and the United States, there has been very little research, from user perspectives, focussed on the outcomes of legal information use at a time of real legal need. There is therefore little empirical evidence about whether people are developing legal capability through the use of information. Studies have suggested that such research has been beyond the time and funding resources of public legal information providers and constrained by uncertainty about effective methods of testing and evaluating the outcomes of legal information use (Forell, 2015; Kirby, 2011; McDonald, Forell and People, 2014).

Research questions

Questions relevant to this paper are:

- Can research on information use be effective for indicating the development of legal capability?

- What were the theoretical issues relating to methods choices, particularly associated with the mixed methods approach chosen for the study?

- What can be learnt from the practical challenges that arose during the data collection process?

The foundation for the answer to the first of these questions comes through the findings, which follow the discussion of research methodology and the practical challenges of implementing the research plan. First, the literature review provides a background to the paper’s information concepts.

Literature review

The focus of the literature review is human information behaviour, specifically the outcomes of information use. Information behaviour is crucial because legal capability is an outcome of learning and problem solving through legal information use. Several models of information behaviour were considered for the study, as discussed below, following definitions of information behaviour and consideration of the methodological challenges of researching outcomes of information use.

Human information behaviour

The term information behaviour describes the various ways in which people interact with information. Wilson (1999, p. 257) defined information behaviour as "those activities a person may engage in when identifying his or her own needs for information, searching for such information in any way and using or transferring that information". Another broad definition is: "...all information-related activities and encounters, including information seeking, information searching, browsing, recognising and expressing information needs, information encountering, information avoidance and information use" (Fourie and Julien, 2014, p. 3) . The use of legal information, in a process of learning and problem solving to achieve a legal outcome, clearly falls within these broad definitions of information behaviour. In the study, information behaviour was extended beyond the mere use of information to include the outcomes achieved with information use.

Outcomes of information use: methodological challenges

A perceived deficit has been noted in the literature over the years in this area (Kari, 2007; Rich, 1997). A review of information behaviour literature between 1950 and 2012 found no studies of information outcomes prior to 1981, but stated that: "it is clear that more attention is being paid to the outcomes of information (in HIB studies) in recent years" (Case and O'Connor, 2016, p. 656). The reviewers suggested that this type of research was discouraged because there are few reliable ways of observing or recording the thoughts and decisions arising from the use of information and because measuring the outcomes of any information use is challenging (p. 657). The recent increase in outcomes studies demonstrates that it is possible to overcome research challenges. Evaluation methods are developing to do so.

Theoretical underpinnings

Legal self-helpers use public legal information in order to address a particular legal need and to inform a particular legal decision or legal task. They engage in active, purposeful information search in an attempt to construct legal capability for the legal matter at hand. In this context, a number of conceptual models of information behaviour were considered for the research, for example, Dervin’s (1998) sense-making, which emphasises purposeful information seeking to bridge a gap, and Wilson’s (1999) model of information behaviour, which is a macro model encompassing a range of behaviours.

Kuhlthau’s (1991) research on the Information Search Process (ISP) was considered to have the most relevance to the study. Hers is an approach to information behaviour that encompasses both cognitive and affective processes such as doubt, fear, anxiety, frustration, self-confidence, perseverance and resilience that are also included in the concept of legal capability. Kuhlthau’s original underpinning concept, the principle of uncertainty, is well suited to a study of legal self-helpers. She was influenced by Kelly’s (1963) theory of personal constructs, believing that a process of construction takes place as people seek meaning from information. The concepts that emerge from the extensive testing of the ISP, for example, the complex interplay of cognitive processes (thoughts), affective processes (feelings) and actions, resonate strongly with the processes that occur when people seek legal information and try to use it to help to solve legal problems. These concepts can also be encompassed in a study of the outcomes of information use. Broadly, Kuhlthau’s work is about seeking meaning in information contexts as the title of her book, Seeking Meaning (2004) indicates.

Research methodology

From the beginning, a mixed methods approach was envisaged for the project although the specific components, and the theoretical underpinnings thereof, evolved as the study developed. This section gives an overview of the study’s methodology with emphasis on the challenges of choosing an appropriate mixed methods approach in a study that collected principally qualitative data but for which the researcher believed that a quantitative component would also be useful.

Research paradigm

This was interpretivist (qualitative) research given that the researcher was interested in "the meanings and experiences of human beings" (Williamson, 2018a, p. 9). Interpretivists see the social world as constructed by people, favour naturalistic enquiry and an inductive style of reasoning, emphasise qualitative data and are aware of context. They are not concerned with measurement or the pursuit of an objective truth and collect mainly qualitative, primarily narrative data, using methods such as case studies, interviews and focus groups.

Consistent with interpretive approaches, the research was undertaken within a constructivist paradigm, informed in this case by personal construct theory (Kelly, 1963), which was also used by Kuhlthau (1991; 2004) for her work on the ISP, as mentioned above. This means that the emphasis was on how ideas, understandings and values were constructed, personally and uniquely, by participants in the study. Personal construct theory takes the philosophical view that "people make sense of their world on an individual basis, i.e., they personally construct reality, with each person’s reality differing to some extent from another person’s"(Williamson, 2018a, p. 12). The personal constructivist approach was appropriate, given that legal capability cannot be observed or understood in isolation from the thought processes, motivations, emotions, decisions, and actions of information users. Legal capability is the result of individual intellectual and psychological engagement with legal information in a particular context and is uniquely constructed by each individual through a learning process. Thus the project was an "attempt to understand the phenomena (i.e., legal capability developed from information use) through accessing the meanings participants assign to them" (Orlikowski and Baroudi, 1991, p. 5).

Mixed research methods

The next step was to decide on which research method/s to use. The research questions required both broad and in-depth pictures of the use of legal information. On the one hand, the preliminary research questions required an overview of legal information use in the Victorian community, from as many respondents as possible, meaning that a quantitative tool would be the best choice. On the other hand, the central research questions, examining the extent to which legal information developed the legal capability of legal self-helpers, were complex and required in-depth responses through personal interviews. A mixed methods approach was therefore required, leading to an extensive exploration of the available mixed methods options.

There are many definitions of mixed methods research. Based on an analysis of nineteen definitions in the literature, Johnson, Onwuegbuzie and Turner (2007) defined mixed methods research as where "a researcher or team of researchers combines elements of qualitative and quantitative approaches (e.g., use of qualitative and quantitative viewpoints, data collection, analysis, inference techniques) for the broad purposes of breadth and depth of understanding and corroboration" (p.123).

The researcher explored various mixed methods options, starting with the pragmatic and mixed methods paradigms, both of which encourage choice of methods from the full array available (Teddlie and Tashakkori, 2009) without reference to paradigmatic philosophies. This approach is problematic given the researcher’s agreement with Green (2012, p. 756) that "philosophical or paradigmatic assumptions about social reality and knowledge…all matter to the methodological decisions an inquirer makes".

Morse (2003) proposed that methods could be combined in mixed methods design or multimethod design as long as researchers adhere to a complementary strengths thesis and the quantitative and qualitative aspects of the research are kept separate. Whichever component does not provide the theoretical drive is supplemental, used to improve the scope and comprehensiveness of the study. This approach bears some similarity to the dialogic approach, although the latter encourages, rather than proscribes the use of quantitative and qualitative data in the same project. This was the approach chosen for the present study.

The dialogic approach

Jennifer Greene and her colleagues take a dialectic approach to mixed methods believing that all paradigms are valuable in understanding complex phenomena and that "the use of multiple paradigms leads to better understandings"(Greene and Caracelli, 2003, p. 96), especially through their dialogue or interaction with each other.

Greene (2012, 2015) emphasised the importance of researchers understanding the assumptions underpinning their research and particularly "the ideologies and values that accompany and support such assumptions" (Greene, 2015, p. 747). Philosophical beliefs determine the researcher’s world view about how knowledge is generated and thus affect "the inquirer’s decisions about and enactments of methodology" (Greene, 2012, p. 757). Greene’s approach is therefore carefully considered and respectful of the positions adopted by researchers from different philosophical traditions.

Nevertheless, her conclusion is that each methodological standpoint is inevitably partial and that "a mixed methods perspective legitimises multiple ways of seeing and hearing, multiple ways of making sense of the social world, and multiple standpoints on what is important and to be valued and cherished" (Greene, 2012, p. 750).

With the dialogic approach, mixing is possible at the level of method, methodology or paradigm/mental model. "Method here refers to individual techniques for gathering and analysing social data" (Greene, 2012, p. 770). The methodology level refers to the justification for a given inquiry tradition which includes inquiry purposes and questions, broad strategies and designs. The mental model combines paradigmatic philosophical assumptions, disciplinary and theoretical predispositions, and other methodological influences.

Greene discussed a modest mix, which she dubbed mixed methods lite as typically involving

mixing only at the level of method or, in some cases, mixing at the methodological level but with one dominant and one secondary methodology … (because such)) studies have the potential to yield better understanding of key phenomena … but are less likely to cross accepted conceptual boundaries or venture into new and uncharted territory (p.758).

The choice of mixed methods lite is appropriate for the current research which is clear in its interpretivist stance but uses mixed data collection techniques, in order to obtain an overview of use of legal information from a larger sample, as well as an in-depth picture of use of legal information.

Data collection

In implementing a mixed methods approach, the research plan included both quantitative and qualitative components, the development of each being influenced by ideas from Kuhlthau’s (1991) ISP research which encouraged the exploration of both cognitive and affective processes in information use. The total period of the data collection, both quantitative and qualitative, was from October, 2016 to November, 2017.

According to the research plan, the first stage involved the collection of quantitative and qualitative data through a questionnaire posted on the websites of the four supporting organisations all of which provide legal information for legal self-helpers. In the second stage, qualitative data were to be collected through in-depth interviews with a purposive sample of legal self-helpers. In the third stage, not discussed here, personal interviews were to be undertaken with a select number of informants with expert knowledge of online public information services and legal self-helpers.

The samples

The sample for the first part depended on people deciding to respond to the questionnaire. The original, notional target number of responses was 300. The number proposed for the purposive sample of interviewees was about thirty people. (The actual numbers in the two parts of the sample are reported in the next major section, "practical challenges".) The sample was to be selected from the questionnaire respondents. The criteria, to guide the purposive sample were principally that interviewees must be over the age of eighteen and have used online public legal information within the past three months to find legal answers, to complete legal tasks, or to represent themselves in a civil matter in a court or tribunal. Although data on socio-economic variables (gender, age, and education) were collected, this information was not important in the selection of the purposive sample. The problems in building a purposive sample are discussed below.

The questionnaire

A key goal of the questionnaire was to provide the researcher with sufficient information to obtain a purposive sample of interviewees. Thus important questions were aimed at finding out the kinds of uses of legal information made by respondents. In order to obtain a cross-section of different kinds of legal self-helpers, the researcher needed information about the nature and complexity of the legal matters involved. She wanted to include both simple and complex matters, as well as users of various complexity of information, and interviewees who had represented themselves in court. The questionnaire also collected qualitative data, in the form of written responses, about the quality and usefulness of legal information.

The interviews

A number of interview topics, developed from insights in the literature including the concept of legal capability, were prepared as a guide for semi-structured, open-ended interview questions. The questions were adapted to each interviewee’s particular legal matter. To determine whether each interviewee was developing legal capability, the interviews explored views about information quality and usefulness, as well as affective responses. The interviews, averaging one hour in length, built on the responses about these matters in the questionnaire.

Data analysis

Analysis was different for quantitative and qualitative data. The questionnaire collected primarily quantitative data. These data were analysed in Survey Monkey and provided demographic information about the respondents, as well as statistics on several aspects of their legal information use. The qualitative survey data were analysed together with the interview data, aided by NVivo software.

Analysis of the qualitative data was not a separate and independent stage of the research. It took place throughout the interview process and the preparation of the transcripts. In keeping with the overall framework of the study, the researcher used constructivist grounded analysis techniques identifying codes and then themes in the data, revealing patterns of meanings (Charmaz, 2014). The thematic organisation of the data enabled a process of within-case and cross-case analysis of the data. This process has been described as identifying consensus and dissonance in the data (Williamson, Given and Scifleet, 2018, p. 457). This iterative process of contrasting and comparing the data of individuals with the data of the group of participants has enabled the researcher to develop an understanding of the motivations and decisions of individuals and the group as a whole.

Practical challenges

As frequently occurs with research, implementing the proposed methodology was not straight- forward. The major challenges were locating and communicating with legal self-helpers, including encouraging them to participate in the research, and selecting suitable interviewees. The poor response to the questionnaire was significant in these problems. While the research was not compromised, considerable flexibility and lateral thinking needed to be exercised. The concept of data saturation, where new information is not forthcoming (Eisenhardt, 1989), was very useful in determining when data collection could be concluded.

Locating, communicating with, and encouraging legal self-helpers

People who use online legal information for the purposes of legal self-help are not easily identified and located within the community. Their information use takes place in private space and time. They are not organised into support groups that can be contacted for research support and are invisible in the justice system outside the tribunals and courts where they may be found appearing as self-represented litigants.

A number of methods were used to find legal self-helpers willing to participate in the research. In chronological order the methods were (1) personal recruitment through a local community legal service, (2) use of an online questionnaire on legal information websites, (3) advertising through a number of legal service providers, and (4) the offer of a financial payment for interview.

During the study’s pilot phase, requests to attempt to recruit participants directly through a local community legal centre gained agreement in principle from the legal centre involved. This method was not pursued when it was observed that many of the clients were unlikely to be legal self-helpers for reasons including their eligibility for Legal Aid services, lack of English language skills, or limited internet access.

An attempt was then made to recruit legal self-helpers through the websites that they might use. Securing the support of four leading service providers and obtaining the necessary permission required a lot of work and took almost twelve months, delaying the research process considerably. This was the major way of recruiting research participants at the planning stage of the research, as indicated in the data collection section, above. Nevertheless, plain sailing is not an apt description.

Poor response to the questionnaire

There was a very low response to the online questionnaire. Although it was online for a period of three months, there were only 133 responses, forty-four of which were complete, or almost complete, and only three respondents volunteered to be interviewed. Other methods of recruiting interviewees were required.

Requests to recruit interviewees from the premises of several important legal service providers were declined because of ethical and privacy concerns of the service providers. Advertisements for interviewees were placed on the websites of service providers; and posters and flyers were placed at the Victorian Public Law Library and several community legal services, but failed to recruit a single interviewee.

Given a desperate situation, the researcher decided to offer a financial payment. The offer was advertised on the websites of two of the study’s public legal service providers, but this failed to recruit any interviewees. The break-through came when an advertisement was posted on the Facebook page of one of the service providers: the result was sixty-seven offers of interview. To help determine eligibility, and to continue the building of the purposive sample, all Facebook respondents were asked to complete the online questionnaire. As a result of this process, the number of responses to the online questionnaire was increased by fifty-five to 190 responses (ninety complete or almost complete).

Selecting suitable interviewees

The offer of a financial reward to recruit interviewees posed a number of challenges to the selection of the purposive sample. Ideal interviewees were persons who had seriously and diligently applied themselves to legal self-help and had reflected on the usefulness of the information they used. It was obvious from some indiscreet comments on the Facebook post that several people were only motivated to request an interview because of the prospect of easy money. Interviews were not offered to those respondents.

Many of the sixty-seven interview requests came from university students for whom the financial offer was very appealing. Despite some reservations, interviews were offered to five university students who appeared, from their questionnaire responses, to have had a genuine legal self-help experience.

After three interviews, a decision was made to cancel the remaining scheduled interviews when it appeared that the financial incentive had encouraged a law student to present for an interview based on an obviously fictitious legal self-help experience. This interview was not included in the analysis.

At this stage, with sixteen quality interviews and the data becoming repetitive, indicating saturation, the researcher decided to terminate the interviews. Although there were only two self-represented litigants in the sample (i.e., people who had represented themselves before a Victorian court or tribunal), suitable people in this group proved very difficult to locate. Most of the volunteers in this category appeared, from their correspondence and questionnaire responses, to be unstable.

Findings

Data analysis resulted in numerous research findings about the information behaviour of legal self- helpers. Space does not permit wide coverage. Since the development of legal capability is the focus of this paper, included here is a brief overview of the major relevant quantitative and qualitative findings.

Quantitative findings

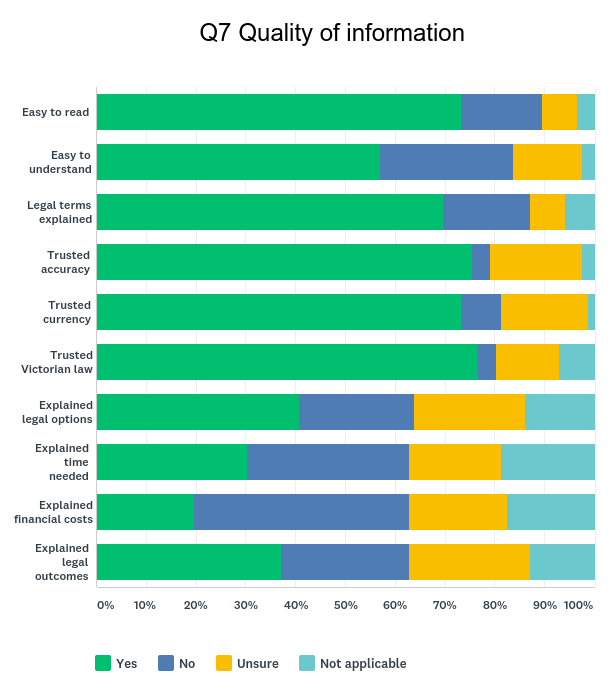

The quantitative data from the questionnaire provided a broad overview of legal information use by the public. Question 7 asked about the quality of information in the information sources respondents had used. The results are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Quality of legal information (N=86).

As shown in Figure 1, below, a key finding relevant to the development of legal capability was that, while 73% of respondents found the information easy to read, only 60% of them found the information easy to understand, flagging a problem with the content beyond readability. This was a surprising result given that respondents were well educated, in the main, with 29% having a university qualification and a further 23% having post-graduate degrees. The fact that less than half the respondents believed that the information explained possible legal options, expected outcomes, and the required time and financial resources, suggested that the information may be inadequate to allow the reader to make an informed decision about how best to resolve their legal matter.

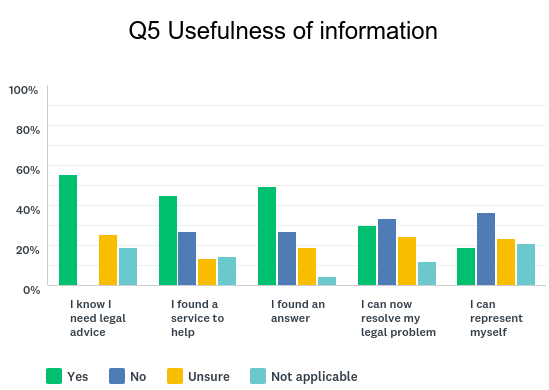

Question 5, about the usefulness of information, is also relevant to the development of legal capability. Figure 2 displays the results.

Figure 2. Usefulness of legal information (N=90).

As demonstrated in Figure 2, less than 40% of respondents were able to resolve their problem with the information they had used and less than 20% believed that the information enabled them to represent themselves before a court or tribunal. Legal information was more useful to achieve other outcomes. Approximately 45% of respondents were able to find a legal service to help them, half of the respondents were able to find an answer to a legal question and 55% of respondents could decide if they needed legal advice.

Respondents reported using legal information for several reasons simultaneously. As a result, a cross- analysis of data from different categories of legal self-helpers failed to reveal if legal information was more useful for particular types of legal self-help.

The quantitative results suggested that legal information service providers were not developing the legal capability of the majority of their users (in the sense of enabling them to deal effectively with the law). Legal information was inadequate to provide self-helpers with access to justice. What the data could not do was to explain the reasons why this was the case.

Qualitative findings

The process of counting helped to gauge the consensus or dissonance within the sample. Counting, a quantitative technique, is "integral to qualitative research, as meaning depends, in part, on number (Sandelowski, 2001, p. 231). Confirming the quantitative findings, cross-case analysis of the interview data revealed that legal information did not meet the needs of the majority of interviewees. Ten of the sixteen interviewees did not find the legal information, which they had explored, to be useful for their purposes; six interviewees found legal information useful or partially useful. Thus 62% of the interviewees were unable to achieve their desired outcome with legal information.

The qualitative data explained the quantitative findings and enabled the researcher to gain insights into the ways in which legal information assisted or hindered legal self-help. It was possible to compile a list of the reasons why the information did not meet needs. In the quotations, below, numbers are used for questionnaire respondents; initials for interviewees.

(1) A major finding was that the information lacked the detail needed for most forms of legal self-help. Four satisfied interviewees were using legal information primarily to obtain basic legal information to answer a simple question. Only two of the six satisfied interviewees found legal information useful for answering complex questions.

All the information I read was very comprehensive and easy to understand but the information that I needed just wasn’t there. (Interviewee CDL)

I guess I was hoping for some ‘case studies’ that would provide details (instead of the very general advice provided which is available on a number of sites. (Questionnaire respondent 15)

(2) Legal self-helpers were critical of the lack of a clear process to follow. This lack of direction had a negative impact on the confidence of the legal self-helper as illustrated by the following quotes:

It wasn’t straight forward and clear – clearly defined steps – and I had to keep jumping from different information to different information which got me confused and that’s where I lost confidence … Even a checklist which says you need this, this and this is something which I think would help a lot. (Interviewee RA)

It caused me greater stress to be honest because these days we rely on web searching…. If you’re going to do that (provide online information) then make the process easy to follow … (Interviewee CO)

(3) None of the interviewees mentioned that their information acknowledged the inherent stress of legal self-help and encouraged them in any way. There was an absence of content in the information resources, to address the natural fears and stress of the user in engaging in the legal system and to empower the user with the confidence required to take legal action. Specific questions about this matter drew a blank. In one case, an interviewee mentioned that learning about her, hitherto unknown, legal risks and responsibilities increased her stress:

Well not really ... in the property settlement it actually made my stress worse because it said that I was liable with my ex-partner even though my name is not on any of the credit cards… (Interviewee KD)

Discussion and conclusion

Kuhlthau’s (1991) ISP research emphasises the exploration of both the cognitive (for example, understanding information), together with the affective (for example, stress and confidence levels when using information). Both types of considerations are important in the development of legal capability. Affect is very important in an information-seeking situation that is likely to involve an emotional component in the legal matter itself, as well as difficulties for a self-helper trying to engage with unfamiliar information and processes. The answer to the first question is that research on information use can effectively indicate legal capability development, or lack thereof, of individuals in a sample.

The research found that legal information, in its current form, was of limited assistance to legal self- helpers. It was most effective for answering fact-based enquiries and for completion of very simple legal procedures. The information needs of self-helpers, with more complex legal problems, were not met. Notably absent was information to encourage and emotionally support the negotiation of an unfamiliar legal system at a time of real legal need. The result was failure to develop fully the legal capability required to take effective legal action. The research has identified a number of ways to improve public legal information – the subject of other papers.

The study, discussed in this paper, involved many challenges, both in the planning stages and in the attempts to implement the plan. Deciding on a mixed methods approach, suited to the research as well as to the researcher’s ontological perspectives, involved extensive reading and reflection. The dialogic approach of mixed methods lite (Greene, 2012; 2015) worked well in combination with concepts emerging from Kuhlthau’s (1991) ISP. Using the mixed methods lite approach, the researcher combined quantitative and qualitative data collection within an interpretivist framework, This approach provides triangulation of data, as well as counteracting critics of studies that involve only quantitative or qualitative data. The reliability of findings based on interview data alone has been challenged by scholars who argue that interviews are performances or retrospective narratives that may not be entirely authentic and which are often accepted uncritically by researchers (Atkinson and Silverman, 1997). With quantitative data the problems of questionnaire design can make findings unreliable (Williamson, 2018b). In the present study, the quantitative findings provided an overview of legal information use in the community. The qualitative data provided insight and meaning to the intriguing, although unexplained findings from the questionnaire.

The key lesson learned from this study may be of value to other researchers: to consider carefully alternatives to recruiting research participants, other than through gatekeeper organisations.

Negotiating access to the clients of these organisations, through websites or work premises, created a lot of work, delayed the project by more than a year, and achieved very little. If involvement with gatekeeper organisations is necessary, the researcher would recommend using their Facebook pages for recruiting participants, if that is possible.

The power of social media was strikingly demonstrated through this research. With hindsight, direct advertising for research participants to an appropriately targeted audience through Facebook, if approved by an ethics committee, may have produced results more quickly. Based on bitter experience, the researcher would also recommend immediately offering a financial incentive for interview and thus avoid time wasted while hoping the right recruits will volunteer out of altruism.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on Fiona Brown’s doctoral research, for which Kirsty Williamson is a supervisor. The authors would like to thank the two other supervisors, Dr Tom Denison and Adjunct Associate Professor, Graeme Johanson.

About the authors

Fiona Brown is a former corporate solicitor with a research interest in legal information. In 2009, she co-authored the history of the Australian Law Librarians’ Association. Her research projects have included a study of law firm library outsourcing in the United Kingdom and in 2015 she completed a survey of Australian law libraries. She is currently completing a PhD in Information Technology at Monash University, Melbourne, Australia. Email: fiona.brown1@monash.edu/it

Kirsty Williamson received her Master of Librarianship from Monash University and her PhD from RMIT University, both Australian universities. She is now Adjunct Senior Research Fellow at Monash University’s Caulfield School of IT and Charles Sturt University’s School of Information Studies, having headed Information and Telecommunications Needs Research for many years (affiliated with both universities). She has undertaken many research projects, funded by a range of different organizations including the principal funding body of Australian Universities, the Australian Research Council (ARC) and also has a strong publication track record. Her principal area of research has been ‘human information behaviour’. Many different community groups have been involved in her research, including older people, women with breast cancer and online investors. Mailing address: Dr Kirsty Williamson, Caulfield School of Information Technology, Monash University PO Box 197, Caulfield East, Vic., 3145. Email: kirsty.williamson@monash.edu.

References

- Atkinson, P. & Silverman, D. (1997). Kundera's 'Immortality': the interview society and the invention of the self. Qualitative Inquiry, 3(3), 304-325.

- Australian Government Productivity Commission. (2014). Access to justice arrangements inquiry report. Retrieved from http://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/access-justice/report

- Belkin, N.J. (2005). Anomalous state of knowledge. In K.E. Fisher, S. Erdelez & L. McKechnie (Eds.), Theories of information behavior (pp. 44-48). Medford, N.J.: Information Today.

- Case, D.O. (2012). Looking for information : a survey of research on information seeking, needs and behavior (3rd ed.). Bingley, UK: Emerald.

- Case, D.O. & O'Connor, L.G. (2016). What's the use? Measuring the frequency of studies of information outcomes. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67(3), 649-661.

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

- Collard, S., Deeming, C., Wintersteiger, L., Jones, M. & Seargant, J. (2011). Public legal education evaluation framework. Retrieved from http://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/geography/migrated/documents/pfrc1201.pdf

- Coumarelos, C., Macourt, D., People, J., McDonald, H. M., Wei, Z., Iriana, R. & Ramsey, S. (2012). Legal Australia-wide survey: legal needs in Victoria. Retrieved from http://www.lawfoundation.net.au/ljf/site/templates/LAW_Vic/$file/LAW_Survey_Vic.pdf

- Dervin, B. (1998). Sense-making theory and practice: an overview of user interests in knowledge seeking and use. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2(2), 36-46.

- Eisenhardt, K.M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. (Special forum on theory building). Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532.

- Forell, S. (2015). Beyond expectations: designing relevant, realistic and effective community legal education and information. Paper presented at the International Legal Aid Conference, Edinburgh, UK. Retrieved from http://www.ilagnet.org/images/edinburgh2015/conferencepapers/beyondgreatexpectations.pdf

- Fourie, I. & Julien, H. (2014). Ending the dance: a research agenda for affect and emotion in studies of information behaviour. Information Research, 19(4). Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/19-4/isic/isic09.html

- Greene, J.C. (2012). Engaging critical issues in social inquiry by mixing methods. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(6), 755-773.

- Greene, J.C. (2015). The emergence of mixing methods in the field of evaluation. Qualitative Health Research, 25(6), 746-750.

- Greene, J.C. & Caracelli, V.J. (2003). Making paradigmic sense of mixed method practice. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research (pp. 91-110). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Johnson, R.B., Onwuegbuzie, A.J. & Turner, L.A. (2007). Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(2), 112-133.

- Kari, J. (2007). Conceptualizing the personal outcomes of information. Information Research, 12(2). Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/12-2/paper292.html

- Kelly, G.A. (1963). The psychology of personal constructs. New York, NY: Norton.

- Kirby, J. (2011). A study in best practice in community legal information: a report for the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust of Australia. Retrieved from http://lawforlife.org.uk/wp- content/uploads/2013/05/study-into-best-practice-in-community-legal-information-joh-kirby- 377.pdf

- Kuhlthau, C.C. (1991). Inside the search process: information seeking from the user's perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(5), 361-371.

- Kuhlthau, C.C. (2004). Seeking meaning: a process approach to library and information services. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

- McDonald, H.M., Forell, S. & People, J. (2014). Limits of legal information strategies: when knowing what to do is not enough. Retrieved from http://www.lawfoundation.net.au/ljf/site/templates/UpdatingJustice/$file/UJ_44_Limits_of_le gal_information_strategies_FINAL.pdf

- Morse, J.M. (2003). Principles of mixed methods and multimethod research design. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (pp. 189- 208). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Orlikowski, W.J. & Baroudi, J.J. (1991). Studying information technology in organisations: research approaches and assumptions. Information Systems Research, 2(1), 1-28.

- Rich, R.F. (1997). Measuring knowledge utilization: processes and outcomes. The International Journal of Knowledge Transfer and Utilization, 10(3), 11-24.

- Sandelowski, M. (2001). Real qualitative researchers do not count: the use of numbers in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 24(3), 230-240.

- Teddlie, C. & Tashakkori, A. (2009). Foundations of mixed methods research: integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Williamson, K. (2018a). Research concepts. In K. Williamson & G. Johanson (Eds.), Research methods: information, systems and contexts (2nd ed., pp. 3-21). Oxford: Chandos.

- Williamson, K. (2018b). Questionnaires,individual interviews and focus group interviews. In K. Williamson & G. Johanson (Eds.), Research methods: Information, systems and contexts (2nd ed., pp. 379-401). Oxford: Chandos.

- Williamson, K., Given, L. M. & Scifleet, P. (2018). Qualitative data analysis. In K. Williamson & G. Johanson (Eds.), Research methods:Information, systems and contexts (2nd ed., pp. 453-472). Oxford: Chandos.

- Wilson, T.D. (1999). Models in information behaviour research. Journal of Documentation, 55(3), 249-270.