Which lens for a study of information retrieval systems for cold case investigations - activity theory, systems or ecological approach?

Naailah Parbhoo-Ebrahim and Ina Fourie

Introduction. An understanding of information behaviour in cold case investigating is essential for information retrieval systems design. Cold case investigations involve collection of information/evidence, use of information technologies, organisation, storage and preservation of these, and use of specialised information retrieval systems. Theoretical frameworks should guide information behaviour studies. This paper assesses the potential of activity theory, traditional systems and ecological approaches to guide an information behaviour study for making recommendations on information retrieval systems supporting cold case investigations.

Method. Literature searches on activity theory, the systems and ecological approaches combined with information behaviour and information retrieval systems and information behaviour in law enforcement were done.

Analysis. TKey information behaviour components and activities in law enforcement were identified through qualitative analysis and mapped against models of activity theory, the systems and ecological approaches.

Findings. All three approaches can support an information behaviour study aimed at recommendations on information retrieval systems for cold case investigations. They, however, must be applied appropriately and adapted according to unique challenges of cold case investigations, the information/evidence and the activities involved.

Conclusion. A tailored and purpose specific approach based on the mapping presented in this paper is suggested in the choice of a theoretical framework.

Introduction

There is global concern about unsolved homicide cases that has resulted in many police departments implementing cold case units, staffed with highly skilled investigators to solve the cases that have gone cold (DetectiveEDU.org, 2018). Methods that address the issue of the increasing rates of cold cases (McClellan, 2007, p. 54) need to be assessed and developed, and improve systems to organise, represent, store and retrieve information, data and evidence are essential (United Nations, 2011, p. 1; Maguire, King, Johnson and Katz, 2010, p. 374). Cold case homicide investigations are those murder cases that have gone unsolved for months, years and decades (Attorney-General’s Department, 2015, p. 2). Homicide cases are considered cold cases once all the facts and inquiries have been exhausted and there are no other solutions or evidence to solve the case. This includes witnesses, suspects and physical evidence (Attorney-General’s Department, 2015, p. 2; Walton, 2014, p. 3). Cold case investigations are homicide cases that have been reported to law enforcement and investigated to the stage that no new evidence or suspects have been presented thus leading the case to go cold and left unsolved for months or years (Walton, 2014, p. 3), often with serious consequences for families looking for closure (Van Asselt, 2017, p. 5). Van Asselt (2017, p. 5) states that families of cold case victims cannot put their minds at rest until the case has been solved, therefore they put pressure on police agencies by using the media or finding their own information and tips and presenting it to the investigators involved in the case. Cases may become active when cold case investigators re-evaluate unsolved cases to determine if new technologies can be used to aid in the investigation or when new evidence can be found in finger print identification systems, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) databases and results from ballistics analysis that have become available since the original investigation (DetectiveEDU.org, 2018; Coleman, 2013, p. 15; Omar, 2008, p. 31). These can be referred to as information systems, databanks, repositories or databases, information retrieval systems; the latter is the term used in this paper.

Cold case investigations are complicated by many issues that hinder the solving of cases. This includes information and evidence not stored or catalogued correctly, not accessible due to technologies becoming obsolete, evidence being contaminated and people not having appropriate skills to search the various systems used by investigators and law enforcement agencies (Dobbs and Voss, 2009, p. 1; Meintjes-Van der Walt, 2008, p. 57; Ashcroft, Daniels and Hart, 2002, p. 6). Cold case investigators play an important role as they are trained to look for specific information and evidence, such as forensic evidence that can aid in solving a case, from what has been collected and stored on the systems and in physical storage boxes, understanding how these fit together to solve cases. They need excellent seeking and searching skills (Geberth, 2003), and have skills in the special decision-making processes involved when searching and using information (Roach, 2017, p. 3). In the solving of cold cases, the nature of data is different from other contexts (Liew, 2007; Baker, 2004). When discussing the use of activity theory in education, Vygotsky (1978, p. 13) refers to critical data collected from how children complete tasks. The focus is on their processes and not their performance. In studying information behaviour in cold case investigations, the processes of collecting data, evidence, processing information, etc. is also most important.

Similar to many other contexts an understanding of information behaviour in cold case investigations can help to address many of these challenges by improving information organisation and retrieval practices and systems (Fidel, 2012; Hepworth, 2007, 2004; Xie, 2006; Freund, Toms and Waterhouse, 2005; Ingwersen and Järvelin, 2005). Saracevic (2011, p. xxviii) confirms the role of the systems approach focused on information retrieval and the user-centred approach focusing on information behaviour: ‘Unfortunately these two main clusters are largely unconnected’.

Models of information behaviour and information retrieval have proven to be important in guiding studies (Mishra, Allen and Pearman, 2015, p. 665; Robson and Robinson, 2013, p. 169). According to Wilson (1999, p. 249) various models of information behaviour and seeking address key issues at various levels of information behaviour. Sometimes such models can be nested or they can complement each other (Wilson, 1999, p. 249). Some models explicitly refer to theories (Case and Given, 2016, p. 142; Wilson, 1999, p. 250) or are discussed in relation to theories. ‘…models and theories that are proposed by researchers have gained strength as they have been adopted as the basis for further research by other investigators’ (Wilson, 1999, p. 250). This paper will therefore consider a suitable theoretical framework to guide a study on information behaviour in cold case investigating that can support the improvement and use of information retrieval systems in cold case investigations. Based on their reported use in information behaviour and information retrieval studies activity theory (Abdallah, 2013, p. 93), the systems (Kowalski, 1997, p. xi) and ecological approaches (Steinerová, 2012, p. 87; Huvila, 2009, p. 696; Wise, 1999, p. 1224; Williamson, 1998, p. 25) will be considered (Wilson, 2006, p. 3). An important requirement is that the frameworks can support a study where technology is key in meeting information needs and fitting in with the assumption proposed in Meyer’s (2016) review on approaches to the building blocks of information behaviour, namely that the ‘interaction between information needs, seeking and use was accepted as a fixed relationship’. According to Saracevic (2011) cited in Ruthven and Kelly (2011, p. xxvii) information behaviour is used to define the various ways in which individuals interact with information, specifically the manner in which they seek and utilise information.

Findings from information behaviour studies should therefore inform the design of information retrieval systems.

In addition, this paper will also cover the clarification of key concepts and a brief background on findings from studies on cold case investigations and information behaviour in law enforcement. The paper will conclude with a recommendation on the appropriate use of frameworks for an information behaviour study of cold case investigations aimed at improving information retrieval systems and their use. The intention of the paper is to answer the question:

Which theoretical framework will be most appropriate to guide a study of information behaviour in cold case investigations to improve information retrieval systems’ design?

Clarification of concepts

The concept of cold case homicide investigations has already been clarified in the introduction. There are, however, a few other concepts that need to be clarified.

Cold case investigators

Homicide investigators are responsible for investigating suspected deaths caused by criminal activities; this includes analysing the crime scene evidence collected, interviewing witnesses and suspects and building a case for the prosecuting office (Criminal Justice Degree School, 2018; Walton, 2014, p. 3-4; Rapp, 2005, p. 41). The term cold case investigators are used for special law enforcement officers or detectives who investigate cases that have gone cold (Rapp, 2005, p. 41). In most police departments or forces they belong to a special cold case unit. They use the evidence collected and witness statements compiled during the homicide investigations and search for additional evidence (Lothridge and Fitzpatrick, 2013, p. 6; Dekle, 2011, p. 142). Their official titles may sometimes be different e.g. police detectives, cold case detectives and homicide investigators (Roufa, 2017), but their tasks and duties fall under this description.

Information retrieval systems

An information retrieval system is a system that allows users to store, retrieve and maintain information (Kowalski, 1997, p. 2) and to support a variety of information seeking strategies in a variety of contexts (Xie, 2002, p. 55). According to Ingwersen and Järvelin (2005, p. 387) and Ellis (1992, p. 54) an information retrieval system is an information system that is created by interactive processes between its information space, information technology setting, interface functionalities and the environment. It includes the capability of searching and finding information of potential value to the seeker(s)’ information need. Information retrieval systems are used to provide information that can potentially support people in taking purposeful actions (Vakkari, 1999, p. 820). Information retrieval systems are also used to support access to a variety of information types that can include data and evidence. Furthermore, Toms (2011) cited in Ruthven and Kelly (2011, p. 43) states that

‘information retrieval systems are purposeful devices developed to service multiple objectives from locating the current weather conditions to identifying critical evidence for the use in complex decision making’.

Research methodology

This paper is based on a scoping literature analysis where the researcher made use of content analysis to analyse relevant literature relating to the three theoretical frameworks, information behaviour and cold case investigations. According to Booth, Sutton and Papaioannou (2016, p.111) a scoping literature analysis is a preliminary search that focuses on identifying the existing reviews and giving an indication of the existing quantity and quality of the studies relevant to the objective of the study. A scoping literature analysis is ideally performed using a selection of electronic databases and grey literature (Booth et al., 2016, p.111). The scope of the literature search focused on cold cases investigators and related professionals (e.g. investigators of ongoing cases, police, pathologists, crime and homicide units, and detectives) and their information behaviour, information needs and use of information systems and information retrieval systems, as well as the three potential theoretical frameworks: activity theory, systems and ecological approach. Search terms included: information behavior/behaviour, information needs, evidence, DNA databases, law enforcement databases, information retrieval systems, cold case investigators, activity theory, systems approach, information ecological approach and conceptual frameworks/theoretical frameworks. The following databases were searched: ERIC, Emerald Insight, Elsevier, Library and Information Science Abstracts, Sabinet, Sage Publications, Springer, Taylor & Francis Online, Wiley Online Library. Findings from the literature analysis are applied to the three frameworks to develop an eclectic framework presented in Figure 4.

Literature review

The literature review is presented under three sub-headings: (i) cold case investigations per se as contextualisation of the paper and need for an information behaviour study, (ii) use of information retrieval systems in cold case investigations, and (iii) findings form studies on information behaviour in law enforcement. A review of literature on the chosen frameworks will be covered in the next section.

Cold case investigations per se

Cold case investigations are those cases that have not been solved when the initial crime was committed due to the lack of evidence, lack in DNA forensic technology and lack of witnesses (Davis, Jensen and Kitchens, 2011, p. xi). There are various types of cold case investigations, namely: the classic cold-case investigation (investigators re-opens a case because of queries from the victims’ family or media coverage), the availability of forensic testing (forensic evidence from cold cases that could not be tested due to lack of technology can be retested with the advancement of technologies) and confessions from suspects and witnesses (cases are re-opened because the suspect confesses to the crime or the eyewitness comes forward to provide information) (Davis et al., 2011, p. xiv). A case is deemed cold when there is no other evidence or clues found (Fike-Data, 2010, p. 1). These cases are then closed if no additional information from witnesses is provided, there is no useful information found and time has lapsed (Fike-Data, 2010, p. 1). A case may also be considered cold when the evidence and technology available is limited when the crime took place, which cannot provide investigators with new clues and new direction (Fike-Data, 2010, p. 1).

Use of information retrieval systems in cold case investigations

The information seeking and behaviour skills of investigators are the same as other information professionals, however, investigators work with high risk information and require particular skills needed to work with and find particular types of information in the various criminal information retrieval systems and databases (Schefcick, 2004, p. 6). Information seeking skills makes an investigator a valuable asset as they are able to navigate easily and quickly through vast amounts of high risk information and searches through information retrieval systems (Schefcick, 2004, p. 6).

Loving (2014) states that the current methodologies and information sharing are made available which includes the CODIS (Combined DNA Information System-DNA profile database), NCMEC (National Center for Missing and Exploited Children), LinX (Law Enforcement Information Exchange), NamUs (National Missing and Unidentified Persons System). These are only a few that have been implemented; there are more systems and other methods that can be included. According to Loving (2014): ‘law enforcements also have access to the new scientific methods and forensic testing, computer technological advancements, and investigation teams (multi-jurisdictional partnerships) which significantly increases evidence processing and solvability’.

Studies on information behaviour in law enforcement

Allen and his co-workers completed a number of studies in law enforcement, and also on using activity theory as theoretical work (Allen, Karanasios and Norman, 2014; Allen, Fortune, Peters and Wilson, 2013; Allen, 2011). Actions and operations are important in police work where time pressure, task complexity and uncertainty are very important in the work environment (Allen, 2011, p. 2165). Some information seeking is based on intuition and others are supported by deliberate information behaviour (Ford, 2015, p. 2). Work in law enforcement are marked by intuition, gut feelings, deliberate seeking for information and evidence, intuitive gut feelings for the information found, deliberate analysis of the information found, integrated information systems, support for information sharing and interoperability of responses in emergency situations, collaboration and information systems that can support collaboration (Allen et al., 2013, p. 1; Ibrahim and Allen, 2012, p. 1916; Allen, Wilson, Norman and Knight, 2008). Work in law enforcement include the supervision of collecting the physical evidence, evaluation of the validity of new evidence, searching of criminal or missing persons, DNA and fingerprint databases, contact with victims and family, obtaining possibly new DNA samples and new evidence and utilising internal/external resources (medical reports and criminalist) (DetectiveEDU.org, 2018; Borglund, 2005) and a variety of non-technical issues (Allen, 2011, p. 2173) (e.g., interviewing the witnesses, family members as well as suspects, building new case to present to the district attorney) (DetectiveEDU.org, 2018). Information communication technology and information retrieval systems such as the Combined DNA Index System are very important in sharing information (Allen et al., 2014, p. 420). Unfortunately, in law enforcement and emergency work there is often a lack of understanding of the nature of emergency responder work and the interplay between technology, information and the user in order to ensure that technological solutions are contextually relevant and appropriately implemented into work practices (Allen et al., 2014, p. 420).

Key findings from information behaviour studies are captured in Table 1. Table 1 shows the key findings from information behaviour studies of cold case investigators, within this table the following elements are identified: types of information, information needs, activities and process and resources. When looking at the elements of Table 1, there are various aspects that fall within the three theoretical frames. The types of information, activities and processes fall within the activity theory framework, the information needs fall with the ecological approach and the resources falls within the systems approach frame. Thus, showing how each of the elements brings in a component(s) from the three theoretical frameworks.

| Authors and scope | Participants/Actors | Types of information (evidence is one of the derivatives of information) | Information needs | Activities and processes | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armstrong, Plecas and Cohen (2013) | Police department Integrated homicide investigative team Country: Canada (British Columbia) | Physical records e.g. foot prints and hand prints Event records e.g. of home invasion | Need to find new evidence or review old evidence in the case of important information being missed Finding new resources where resources are limited | Activities: Searching for gang demographics Understanding the influence of political variables Aiding in homicide clearance rates Procedures/processes: Investigative procedures Analytical processes | Timely search warrants Forensic services informants’ surveillance measures Information databases on gang and non-gang related homicides |

| Davis, Jensen and Kitchens (2011) | Law enforcement agency Federal Bureau of Investigation’s violent criminal apprehensive program unit Police department Sheriff’s department Investigators Countries: USA: Colombia Baltimore (Maryland), Dallas (Texas) | DNA e.g. hair strains Finger prints Finger print matches Victim characteristics e.g. hair colour and dental records Crime context e.g. where the crime took place Physical evidence e.g. shoe print | New leads on cold cases Family enquiries | Activities: DNA forensic technology analysis, finger print matching, eyewitness probative evidence, searching and acting on new information leads Procedures/processes: Recording of motives for the crime Conducting of debriefings of the cold cases so that arrests can be made for the crime if the leads prove to be true | Summaries of written reports of unsolved cases Combined DNA Index System |

| Dobbs and Voss (2010) | Crime analysis unit Forensic anthropologists Investigations bureau Detectives Investigators Country: Not specified | Reports e.g. witness or suspect statements | Need for new evidence due to lack of evidence found when the case was initially investigated Research notes of the pervious investigator about the crime Reports of forensic analysis on the whereabouts of suspects Leads of witnesses Criminal backgrounds | Activity: Search for information based on the crime Procedure/process: Access technologies to aid the search | Missing persons database Open source databases e.g. John Doe, court documents and news media reports Liaison with other agencies |

| Chaikin (2012) | Denver Police Department Detectives victim specialists Country: USA: Denver (Colorado) | DNA matches Anonymous tips Photo line ups Interviews: witnesses, family and friends | Gathering solid evidence | Activities: Interviewing witnesses and family members to gather information; searching databases such as DNA databases and finger print matches Procedures/processes: Using the information and evidence found during the investigation to determine whether criminal charges will be filed against the suspects in order to present the finding to a district attorney | Combined DNA Index System |

| Rapp (2015) | Federal Bureau of Investigation Homicide investigators Detectives Police patrol Country: USA – Virginia | ID documents DNA finger prints (full and partial)) | Need to find information that allows investigators to complete the report Need for new evidence in order to conduct the investigation and possibly close the case | Activities: Dispatching records and tapes of radio transmission, records kept by each individual involved in the case based on the scene and medical examiner reports Analysing ID documents Analysing finger prints matches Procedure/process: Obtaining of matches on the basis of finding characteristics of people involved thus allowing investigators to complete reports and possibly find new evidence to close the case | Information management systems Violent Criminal Apprehension Program system Missing persons database |

| Carter (2013) | Bureau of Justice Assistance Patrol supervisors Homicide investigators | Interviews of witnesses and suspects Reviews of documents DNA found on body Bullets left in the body or around the body | Information needed to focus on supporting the homicide investigation such as re- interviewing witnesses, re- evaluating the crime scene photographs and evidence | Activities: Interviewing family members, friends and suspects Analysing suspects’ phone records | Search warrants DNA databases such as Combined DNA Index System |

| Country: USA | Hair follicles on the body or under the nails of the victim | Analysing blood splatters and patterns Extracting evidence from victims e.g. such as DNA found on the body, bullets left in the body or around the body and hair follicles on the body or under the nails of the victim Procedures/processes: Sharing information with other agencies in order to gather data and evidence thus Reviewing of documents improving best practices that can be used across all agencies | Blood splatter analysis Intelligence resources that include personal data collected Broader criminal records |

||

| Fike-Data (2010) | Phoenix Police Department National law enforcement Cold case units Country: USA | DNA mapping Finger print identification Physical evidence e.g. collected from and around the scene Reports from the crime scene and forensic analysis Interviews with suspects and witnesses Media driven information perspectives Witness testimony Photographs Statements: witness, family and friends Telephone records | New leads: · to find solutions · to help the investigators increase their knowledge · to decrease inconclusive results | Activities: Evaluating of telephone records viewing photographs of the crime scene to determine if anything was missed interviewing people who have information about the crime Procedures/processes: Gathering of information that investigators can view Investigation of the crime as if it has happened recently | Cell phone records Wire tapes Surveillance footage Criminal behaviour such as: · patterns of serial killers · types of weapons they prone to us · outward appearance · manner of criminals typically behaviour in public or around other individuals Autopsy and medical examiner conclusion reports |

| National Sheriff’s Association (2011) | United States Department of Justice Law enforcement agencies Cold case units Retired investigators Country: USA | Reports on the initial crime Evidence found Possible suspects Archived files for review | Physical evidence Follow up on existing evidence | Activities: Conducting surveys and questionnaires with law enforcement Analysing the data collected Procedures/processes: Follow up on existing evidence in case information was lost or misinterpreted Investigation of the inconsistences and conflict of evidence that may have araised when the case was investigated | DNA databases and fingerprint analysis databases Forensic investigative tools Combined DNA Index System |

Review of a study framework: activity theory, systems approach or the ecological approach?

Different models, theoretical frameworks, theories and approaches have been reported in information science literature which can be useful for an information behaviour study in cold case investigations: Ingwersen and Järvelin (2005, p. 388) present Saracevic’s nested model of context stratification for information retrieval, Byström and Järvelin (1995) present a model on how task complexity affects information seeking and use, Krikelas (1983) presents a general model on information seeking behaviour, while Ellis (2005) focuses on patterns and concepts in his model of information behaviour research.

Early research focused strongly on the systems approach (Ingwersen, 2001, p.1) in the design and evaluation of information retrieval systems. Although often criticised this approach is still important (Lasker, 1981, p. xxiii). In information behaviour research the systems approach was followed and supplemented by the user-centred approach, cognitive approach, socio-cognitive approach and affective paradigm (focusing on affect and emotion) (Ellis, 1989, p. 172; Ingwersen and Järvelin, 2005, p. 17; Järvelin, 2006, p. 972). Gradually the use of other approaches in studies of information behaviour and in the design of information retrieval systems developed: Fidel (2012, p. 49), Eddy et al. (2014, p. 3) and Williamson (1998, p. 25) have reported on the use of the ecological and information ecological approaches. Although it has been used in educational research (Kyburz-Graber, Hofer and Wolfensberger, 2006, p. 104) for many years after being introduced by Vygotsky (1978, p. 79), activity theory has only more recently also gained considerable support in the information behaviour literature (Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2018, p. 3; Karanasios, 2018, p. 134; Kwon, 2017: el; Allen, Brown, Karanasios, and Norman, 2013, p. 836; Ghobadi, 2013; Allen, Karanasio, Slavova, 2011, p. 776; Wilson, 2008, p. 119; Mursu, Luukkonen, Toivanen and Korpela, 2007; Xu, 2007, p. 985; Xu and Liu, 2007, p. 987).

Three possibilities will be assessed for their value to guide an information behaviour study on cold case investigations namely, activity theory, systems approach and ecological approach. These were specifically selected for their ability to address the use of information technologies, databases and information retrieval systems that are used to support cold case investigations and solving cold cases.

Activity theory approach

In the literature of information science and more specifically information behaviour, activity theory has been used by various fields of organisation, management, social psychology, education as well as human computer interaction and information systems design (Almalki, Gray and Martin-Sanchez, 2016; Karanasios, Allen and Finnegan, 2015, p. 310; Roos, 2012; Spasser, 1999, p. 1136).

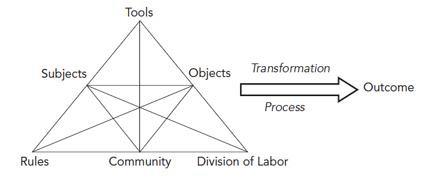

Activity theory is defined as a powerful and clarifying descriptive tool used to understand the unity of consciousness and activities (Foot and Groleau, 2011; Nardi, 2005, p. 4; Engeström, 2000, p. 301). Consciousness is the expression of the human mind and activity is the human interaction with the objective reality (Malaurent and Avison, 2015, p. 232; Bedny, Karwowski and Bedny, 2010, p. 377; Maceviciuté and Wilson, 2008; Kaptelinin, 2005, p. 55). Activity theory incorporates a strong notion of intentionality, history, mediation, collaboration and development in constructing consciousness (Hasan, Smith and Finnegan, 2017, p. 275; Iyamu and Ngqame, 2017, p. 3; Nardi, 2005, p. 4; Kuutti, 1996, p. 26). It connotes the study of the mode of human behaviour that acts upon objects to transform them (Pena-Ayala, Sossa and Mendez, 2014, p. 131; Wilson, 2008, p. 120; Spasser, 2007). It aims at understanding technology as part of the larger scope of human activities (Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2009, p. 5). Activity theory is dynamic. It recognises that activities, actions and operations change over time (Pena-Ayala et al., 2014, p. 132; Allen et al., 2011, p. 780). It is furthermore constrained by formal, informal as well as technical rules, norms and conventions of the community, in this case the law enforcement community (Pena-Ayala et al., 2014, p. 134; Widén-Wulff and Davenport, 2007; Barab, Schatz and Scheckler, 2004, p. 27). Activity theory supports three forms of action: self- action (things that are treated as functioning independently and viewed as acting under their own powers), inter-action (things that balance against other things in casual interconnection) and trans-action (dealing with aspects and phases) (Barab et al., 2004, p. 27). The application of activity theory can be characterised as an attempt to integrate three perspectives: objective, ecological and sociocultural. It takes into account cultural factors and developmental aspects of human mental life (Sawchuk, Duarte and Elhammoumi, 2006, p. 29; Kaptelinin, 2005, p. 54-55; Karpatschof, 2000, p. 4), and it differentiates between processes at various levels taking into consideration the object to which processes are oriented (Kaptelinin, 2005, p. 55). Figure 1 portrays an activity theory system as argued by Engeström who is considered a leader in the application of activity theory. Various versions of this has been presented by Karanasios, Thakker, Lau, Allen, Dimitravo, and Norman (2013, p. 2456) and Wilson (2006). According to Wilson (2006) as well as Karanasios and Allen (2013, p. 290) the activity theory approach consists of a triangle that remains the dominant figure, however, one subject is represented and the concept of division of labour has also been separately represented. Wilson (2006) further states that the concept of community is included within the cultural context where the activity is performed. The rules are also separated from artefacts that are represented as instruments (Karanasios and Allen, 2014, p. 533; Spinuzzi, 2012, p. 342; Nowé, Maceviciuté and Wilson, 2008; Wilson, 2006).

Figure 1: Activity theory system (Engeström, 1987, p. 78)

There are a number of reasons why activity theory can support a study of information behaviour in cold case investigations, the manner in which investigators gather evidence, and the processes involved in solving cases. The work of Karanasio et al. (2015), Rossmo and Summers (2015) and Clarke and Felson (1993), highlight some issues. Activity theory can

- address the relevance of the routine behaviour of understanding crime patterns in cold case investigations

- explain aggregated trends and behaviours of society

- be used to analyse behaviour at an individual level

- support how time and place are treated in collecting evidence, how known information about a suspect and the victim is used

- be used to understand a suspects’ behaviour when being interviewed

- be used when compiling a suspect profile to make an arrest.

Systems approach

The systems, also referred to as the traditional approach or systems view has been applied in information science and information retrieval research over many years since the early days of information retrieval systems (Ingwersen, 1992, p. 80; Ellis, 1989; Soergel, 1985; Ellis, 1984, p. 261). The systems approach considers the environment, the whole, the parts and the purpose. There are various concepts associated with the systems approach namely, holism, specialisation, non-summational, grouping, coordination and emergent properties (Thakur, 2017). It is a science that compares the system as its object (Stichweh, 2013, p. 1). Heylighen (1998) explains: ‘A system approach integrates the analytics and synthetic methods encompassing both holism and reductionism’.

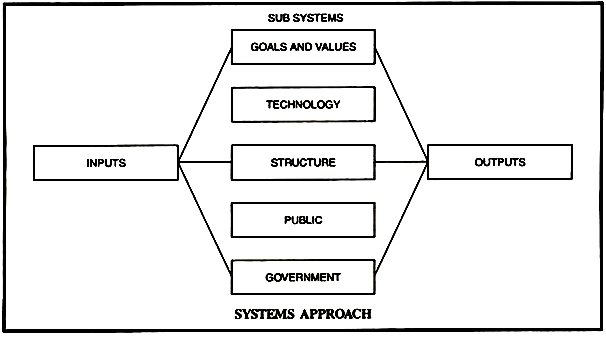

According to Gordon (2017) the systems approach comprises of three purposively designed parts that consists of: input, process and output. Input includes all the raw materials, queries and search terms (Gordon, 2017). Processes include the operations, quality assurance and activities that the user has entered into the input technologies and systems (Gordon, 2017; Sonnenwald, 2016, p. 171). In the case of information retrieval systems input would refer to problems with the representation of documents and other entities or search strategies, and processes for the processing of search requests and retrieval of search results. Outputs refer to the products and results to meet the requirements of the users (Gordon, 2017) (in the case of information retrieval these would include full-text records or representations of records) (Kowalski, 1997, p. 41). The systems approach further emphasises the use of feedback responses to aid in correcting errors that may arise when executing operations (Gordon, 2017). A system approach thus contributes to ensuring quality of the product and information that meets the requirements of the users (Gordon, 2017). ‘This is due to the approach systematically integrating all functions into an interrelated team effort, providing a structured framework for the development process from concept to production’ as stated by Gordon (2017). With regards to the systems approach it is important to link the input, processes, outputs and resource data and view them together as opposed to separately (Department of Economic…, 2003, p. 18). Figure 2 indicates that several inputs are received from the user(s). The input is processed and the output is produced (Kashyap, 2018). Each of the sub-systems are interconnected; if any action is taken to solve a problem it will have an effect on the other sub-systems (Kashyap, 2018). When applying the systems approach the environment in which a system operates and the demands, rules and procedures from such an environment is also important.

Figure 2: Systems approach (Kashyap, 2018)

In cold cases the larger environment in which cases are solved is especially important. It is important to monitor the demands of the criminal justice services, provision of services and processing of suspects (United Nations, 2003, p. 18). It is important to acknowledge how different agencies and components of the criminal justice system work together (Department of Economic…, 2003, p. 18), and the information and evidence that can be provided by each. Systems (electronic and manual) where information and evidence are stored must be acknowledged and seen as a whole. It is important to consider what evidence is processed and where and how such evidence is represented, organised and stored across an array of information and information retrieval systems that can aid in cold case investigations. The value, effectiveness and efficiency of such systems must be evaluated to ensure that it meets with the needs of cold case investigators. Many examples of the evaluation of information retrieval systems as well as methods of evaluation are noted in the subject literature (Ingwersen and Järvelin, 2005; Soergel, 1985). Although not specifically for information retrieval systems in law enforcement (Kumar, De Beer, Vanthienen and Moens, 2005, p. 5).

Ecological approach

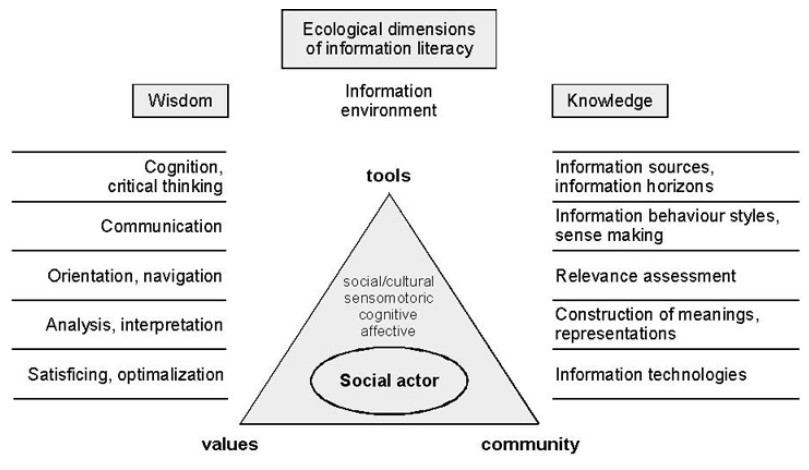

An ecological or information ecological approach has been applied in a few studies of information behaviour as well as in relation to information retrieval systems (e.g., Fidel, 2012; Steinerová, 2012; Huvila, 2009; Williamson, 1998). Fidel (2012, p. 274) as well as Nardi and O’Day (1998) define an information ecology as a system of people, practices, values and technologies in a particular local environment. In an information ecology the spotlight is not on the technology but on the human activities that are served by the technology (Nardi and O’Day, 1998). In this sense it would be useful for an information behaviour study aiming to improve information retrieval systems and the use of ICT. According to Fidel (2012, p. 274) ‘an ecological approach focuses on and gives priority to the investigation of context in which the behavior takes place’. It is used as a guide to ensure that humans are on the right path, but it does not provide a step-by-step procedure (Pivnick, Wise and Alberta, 2003, p. 152). An ecological approach requires a user to live with uncertainty, having to trust their hunches and ambiguity (Pivnick et al., 2003, p. 152). Furthermore, the ecological approach does not replace but only guides the choices of the research instrument (Pivnick et al., 2003, p. 152-153). Figure 3 indicates that within an ecological approach knowledge includes the information sources, information behaviour and the relevance of the assessment of said information, furthermore showing how wisdom includes the manner in which individuals communicate, analyse and interpret the information found. These can all be important in solving cold cases. Figure 3 reflects an ecological dimension of information literacy proposed by Steinerová (2010).

Figure 3: A model of ecological dimensions of information literacy (Steinerová, 2010)

In terms of the use of the ecological approach in an information behaviour study of cold case investigations, an ecological approach will especially support the uncertainty with which investigators need to work and how they need to live with the uncertainty that a case may never be solved. The uncertainty supported by the ecological approach is also very relevant to the families of victims with regards to not knowing if the homicide case will ever be solved. Cold case investigators who cannot acquire new evidence may follow a hunch and change their search strategies on criminal information retrieval systems to try and solve the case (Cronin, Murphy, Spahr, Toliver and Weger, 2007, p. 27).

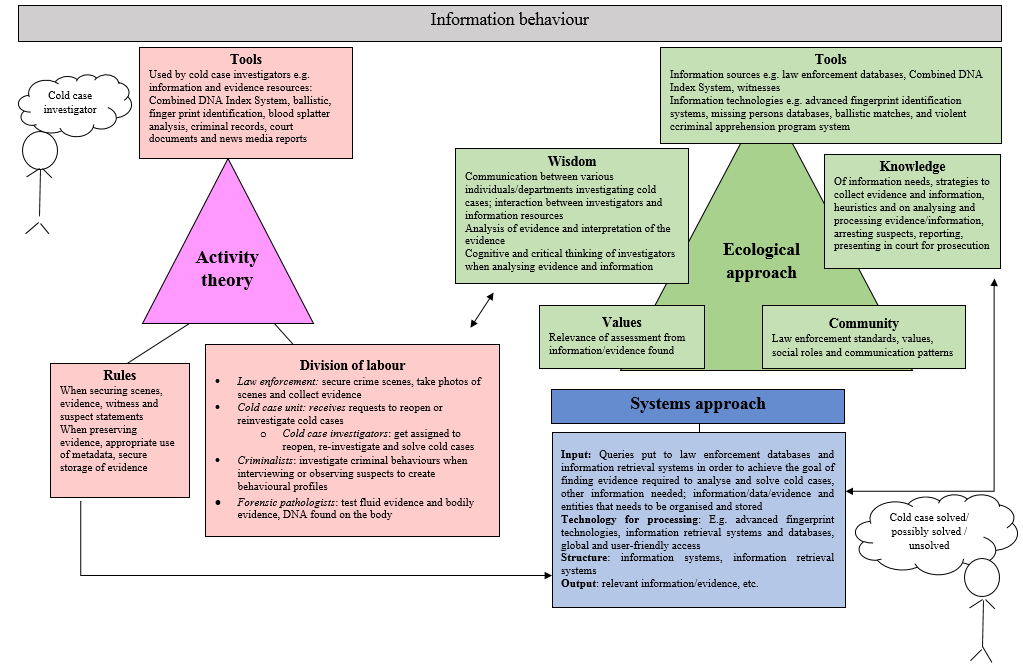

Figure 4: illustrates the preliminary application of the three theoretical frameworks to cold case investigations to support an information behaviour study. In this model the researcher has not included: subjects, objects and community as shown in Figure 1 as it is not quite clear yet how these aspects apply to the context of cold case investigations. After empirical data collection this might be clearer.

Figure 4: Preliminary application of the three theoretical frameworks to cold case investigations to support an information behaviour study

Recommendations

Cold cases may go unsolved for many years as stated in the definition of cold cases. When solved, it is done through different search strategies and approaches. To improve the information retrieval systems that are used in cold case investigations the information behaviour of people involved, such as the cold case investigators, must be understood.

All three approaches hold value to the study of information behaviour in cold case investigations considering the findings from related studies noted in Table 1. Activity theory focuses on the tools used in finding, organising and storing information such as specialised databases, e.g. Combined DNA Index System and finger print matching databases. It can also be applied to study the information activities of all the actors involved e.g. cold case investigators, how they collect evidence and information such as statements from witnesses and suspects. It can be applied to the information and evidence that are collected, organised and stored, the unique processes involved in cold case investigations e.g. obtaining matches on the basis of finding characteristics of people involved in the investigation to complete reports and possibly find new evidence to close the case and recording the motives for the crime, how people and institutions collaborate in sharing information and expertise. In cold case investigations information activities (falling under information behaviour) are guided by very specific rules and procedural guidelines. There however, is also a lot of uncertainty at stake and the need to act on gut feelings. Insight from the ecological approach might support the information behaviour study by highlighting uncertainty when studying information behaviour in cold case investigations, also the spectrum of information sources (information horizons) that need to be considered from the wide information environment (e.g. between different law enforcement agencies), the values attached to information and agencies. Similar to activity theory, the ecological approach allows for consideration of the community in which information behaviour manifests. The systems approach raises awareness for the input that needs to be stored in information retrieval systems e.g. ballistics results, DNA, fingerprints, witness statements, the need to acknowledge the purpose of cold case investigations, need to consider the role of all sub-divisions, processing and output.

Conclusion

In conclusion when looking at cold case investigations, the need for information and the appropriateness and efficiency of integrated information retrieval systems supporting the full spectrum of information needs, types of information, evidence, data and critical data must be supported from studies of information behaviour and the use of such systems. The scope of such a study, data collection and research questions need to be guided by a theoretical framework. A systems approach can guide the researcher to consider the environment and society in which cold cases are solved, the purpose and objectives of cold case investigations and the various components, departments and sections involved. Using the systems approach can furthermore aid in determining if the relevant queries are inputted into the various systems such as CODIS and if the investigators have retrieved the relevant information and evidence, and more specifically how information and evidence is organized (i.e., use of metadata) and stored. An ecological approach can call for attention to people (investigators, suspects, victims and witnesses), practices (investigating and legal) and technologies (DNA, fingerprint and bullet ballistics databases and analysis technologies), as well as uncertainty that marks cold case investigations. The ecological approach can also encourage consideration of communication between the various individuals that investigate cold cases, and furthermore how the interaction between investigators and information and evidence resources, increase cognitive and critical thinking skills when analysing evidence and information. If the theoretical lens is activity theory, a researcher will be guided to consider the manner in which investigators gather information, the processes they follow to solving the cold cases, and the technology they use with regards to securing the scene, preserving evidence, appropriate use of metadata and interviewing witnesses and suspects. Either one of the systems and ecological approaches or activity theory can be applied in information behaviour studies in the contexts of law enforcement. Activity theory supplemented by the other two seems most appropriate if the aim of such a study is to improve the integrated use of information retrieval systems, the support of information behaviour, and to contribute to the solving of cold cases.

About the author

Naailah Parbhoo-Ebrahim is a full-time lecturer in the Department of Information Science, as well as the office manager and research officer for the African Centre of Excellence for Information Ethics based in the Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria. She holds a masters in Information Technology with specialisation in library services. She is currently completing her doctorate in Information Science at the University of Pretoria. Her research focus includes information behaviour, information retrieval, information ethics, cold case investigations and competitive intelligence. Postal address: University of Pretoria, Department of Information Science, Hatfield, 0028, Pretoria, South Africa. She can be contacted at naailah.parbhoo@up.ac.za

Dr. Ina Fourie is a full professor in the Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria. She holds a doctorate in Information Science, and a post-graduate diploma in tertiary education. Her research focus includes information behaviour, information literacy, information services, current awareness services and distance education. Currently she mostly focuses on affect and emotion and palliative care including work on cancer, pain and autoethnography. Postal address: Private bag X20, Hatfield, 0028, Pretoria, South Africa. She can be contacted at ina.fourie@up.ac.za

References

- Abdallah, N.B. (2013). Activity theory as a framework for understanding information literacy. European conference on information literacy (pp. 93-99). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International.

- Allen, D. (2011). Information behavior and decision making in time-constrained practice: a dual- processing perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(11), 2165-2181.

- Allen, D.K., Brown, A., Karanasios, S. & Norman, A. (2013). How should technology-mediated organizational change be explained? A comparison of the contributions of critical realism and activity theory. MIS Quarterly, 37(3), 835-854.

- Allen, D., Fortune, D., Peters, R. & Wilson, F. (2013). Enterprise information systems for crisis management. Paper presented at the CENTERIS 2013: Conference on ENTERprise Information Systems, Lisboa, Portugal. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266382434_Enterprise_Information_Systems_for_Crisis_Managementt

- Allen, D.K., Karanasios, S. & Norman, A. (2014). Information sharing and interoperability: the case of major incident management. European Journal of Information Systems, 23(4), 418-432.

- Allen, D., Karanasios, S. & Slavova. M. (2011). Working with activity theory: context, technology, and information behavior. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(4), 776-788.

- Allen, D.K., Wilson, T.D., Norman, A.W.T. & Knight, C. (2008). Information on the move: the use of mobile information systems by UK police forces. Information Research, 13(4), paper 378. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/13-4/paper378.html.

- Almalki, M., Gray, K. & Martin-Sanchez, F. (2016) Activity theory as a theoretical framework for health self-quantification: a systematic review of empirical studies. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(5). Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4909388/?report=classic

- Armstrong, J., Plecas, D. & Cohen, I.M. (2013). The value of resources in solving homicides: the difference between gang related and non-gang related cases. Retrieved from: https://www.ufv.ca/media/assets/criminal-justice-research/Report---The-Value-of-Resources-in-Solving-Homicides.pdf

- Ashcroft, J., Daniels, D.J. & Hart, S.V. (2002). Using DNA to solve cold cases. Retrieved from the website of the National Criminal Justice Reference Service: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/194197.pdf.

- Attorney-General’s Department. Government of South Australia (2015). Unsolved homicides: information for families and friends. Retrieved from https://www.dpp.sa.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Unsolved-Homicides.pdf

- Baker, L.M. (2004). The information needs of female Police Officers involved in undercover prostitution work. Information Research, 10(1), paper 209. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/10-1/paper209.html.

- Barab, S., Schatz, S. & Scheckler, R. (2004). Using activity theory to conceptualize online community and using online community to conceptualize activity theory. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 11(1), 25-47.

- Bedny, I.S., Karwowski, W. & Bedny, G.Z. (2010). A method of human reliability assessment based on systemic-structural activity theory. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 26(4), 377-402.

- Booth, A., Sutton, A. & Papaioannou, D. (2016). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. (2nd edition). London: Sage Publications.

- Borglund, E. (2005). Operational use of electronic records in police work. Information Research, 10(4), paper 236. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/10-4/paper236.html

- Byström, K. & Järvelin, K. (1995). Task complexity affects information seeking and use. Information Processing & Management, 31(2), 191-213.

- Carter, D.L. (2013). Homicide process mapping, best practices for increasing homicide clearance. Retrieved from the website of the Institute for Intergovernmental Research: https://www.iir.com/Documents/Homicide_Process_Mapping_September_email.pdf

- Case, D.O. & Given, L.M. (2016). Looking for information: a survey of research on information seeking, needs and behavior. (4th. ed.) Bingley, UK: Emerald.

- Chaikin, S. (2012). Homicide cold case investigations a guide for victims and their families. Retrieved from https://www.denvergov.org/content/dam/denvergov/Portals/720/documents/VAU_Cold_Case_Program_Homicide_Booklet_2012.pdf.

- Clarke, R.V. & Felson, M. (1993). Routine activity and rational choice. London: Transaction Publishers.

- Coleman, J. (2013). Handbook of forensic services. Virginia, VA: An FBI Laboratory Publication.

- Criminal Justice Degree School. (2018). Homicide detective: career guide. Criminal justice degree schools. Retrieved from https://www.criminaljusticedegreeschools.com/criminal-justice- careers/homicide-detective/

- Cronin, J.M., Murphy, G.R., Spahr, L.L, Toliver, J.I. & Weger, R.E. (2007). Promoting effective homicide investigations. Washington, DC: Police Executive Research Forum.

- Davis, R.C., Jensen, C. & Kitchens, K.E. (2011). Cold-case investigations: an analysis of current practices and factors associated with successful outcomes. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/.../RAND_TR948.pdf.

- Dekle, G.R. (2011). The last murder: the investigation, prosecution and execution of Ted Bundy. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2003). Manual for the development of a system of criminal justice statistics. Retrieved from the website of United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/SeriesF/SeriesF_89E.pdf.

- DetectiveEDU.org. (2018). What are cold case investigations? Retrieved from http://www.detectiveedu.org/cold-case-investigations.

- Dobbs, M.R. & Voss, M.T. (2009). Reviving the cold case: an analytical approach to case closure. Retrieved from http://www.iaca.net/Resources/Articles/Reviving_the_Cold_Case.pdf.

- Eddy, B.G.B., Hearn, J.E., Luther, M., Van Zyll de Jong, W., Bowers, R., Parsons, D., Strickland, P.G. & Wheeler, B. (2014). An information ecology approach to science-policy integration in adaptive management of social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 19(3), 1-16.

- Ellis, D. (1984). The effectiveness of information retrieval systems: the need for improved explanatory frameworks. Social Science Information Studies, 4(4), 261-272.

- Ellis, D. (1989). Behavioural approach to information retrieval system design. Journal of Documentation, 45(3), 171-212.

- Ellis, D. (1992). The physical and cognitive paradigms in information retrieval research. Journal of Documentation, 48(1), 45-64.

- Ellis, D. (2005). Ellis’s model of information-seeking behaviour, in K.E. Fisher, S. Erdelez and L. McKechnie (Ed.) Theories of information behaviour (pp. 138-142). Medford: American Society for Information Science and Technology by Information Today.

- Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding: an activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Helsinki, Finland: Orienta-Konsultit.

- Engeström, Y. (2000). Activity theory and the social construction of knowledge: a story of four umpires. Organization, 7(2), 301-310.

- Fidel, R. (2012). Human information interaction: an ecological approach to information behaviour. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Fike-Data, E. (2010). Cracking the cold case: the anatomy and deconstruction of unsolved crimes. Unpublished undergraduate honors thesis, Barrett Honors College, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA. Retrieved from https://www.documentingreality.com/forum/attachments/f227/520618d1394038005-lists- death-suicide-unsolved-missing-fike-data_october-2010_cracking-cold-case-anatomy- deconstruction-unsolved-crimes.pdf.

- Foot, K. & Groleau, C. (2011). Contradictions, transitions, and materiality in organizing processes: an activity theory perspective. First Monday, 16(6). Retrieved from http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3479/2983.

- Ford, N. (2015). Introduction to information behavior. London: Facet Publishing.

- Freund, L., Toms, E.G. & Waterhouse, J. (2005). Modeling the information behaviour of software engineers using a work - task framework. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 42(1), 1-23.

- Geberth, V.J (2003). Practical crime scene investigation: legal considerations. In V.J. Geberth, Practical homicide investigation: tactics, procedures, and forensic techniques (3rd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. Retrieved from http://www.practicalhomicide.com/articles/LegalCS.htm.

- Ghobadi, S. (2013). Application of activity theory in understanding online communities of practice: a case of feminism. The Journal of Community Informatics, 9(1). Retrieved from http://ci- journal.net/index.php/ciej/article/view/828/1017

- Gordon, J. (2017). Importance of the system approach principle. Retrieved from http://smallbusiness.chron.com/importance-system-approach-principle-81413.html.

- Hasan, H., Smith, S. & Finnegan, P. (2017). An activity theoretic analysis of the mediating role of information systems in tackling climate change adaptation. Information Systems Journal, 27(3), 271-308.

- Hepworth, M. (2004). A framework for understanding user requirements for an information service: defining the needs of informal carers. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 55(8), 695-708.

- Hepworth, M. (2007). Knowledge of information behaviour and its relevance to the design of people-centred information products and services. Journal of Documentation, 63(1), 33-56.

- Heylighen, F. (1998). Basic concepts of the systems approach. Retrieved from Principia Cybernetica web site: http://pespmc1.vub.ac.be/SYSAPPR.html.

- Huvila, I. (2009). Ecological framework of information interactions and information infrastructures. Journal of Information Science, 35(6), 695-708.

- Ibrahim, N.H. & Allen, D. (2012). Information sharing and trust during major incidents: findings from the oil industry. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(10), 1916-1928.

- Ingwersen, P. (1992). Information retrieval interaction. London: Taylor Graham Publishing.

- Ingwersen, P. (2001). Cognitive information retrieval. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 34, 3-52. Retrieved from http://peteringwersen.info/publications/2330_ingwersen_arist34-finalprint.pdf.

- Ingwersen, P. & Järvelin, K. (2005). The turn: integration of information seeking and retrieval in context. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

- Iyamu, T. & Ngqame, Y. (2017). Towards a conceptual framework for protection of personal information from the perspective of activity theory. South African Journal of Information Management, 19(1), 1-7.

- Järvelin, K. (2006). An analysis of two approaches in information retrieval: from frameworks to study designs. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 58(7), 971-986.

- Kaptelinin, V. (2005). Activity theory: implications for human-computer interaction. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d6cc/43b0ced736237dc06618bfac91f467117aeb.pdf.

- Kaptelinin, V. & Nardi, B.A. (2009). Acting with technology: activity theory and interactive design. Retrieved from https://mitpress.mit.edu/sites/default/files/titles/content/9780262513319_sch_0001.pdf.

- Kaptelinin, V. & Nardi, B.A. (2018). Activity theory as a framework for human-technology interaction research. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 25(1), 3-5.

- Karanasios, S. (2018). Toward a unified view of technology and activity: the contribution of activity theory to information systems research. Information Technology & People, 31(1), 134-155.

- Karanasios, S. & Allen, D. (2013). ICT for development in the context of the closure of Chernobyl nuclear power plant: an activity theory perspective. Information Systems Journal, 23(4), 287-306.

- Karanasios, S. & Allen, D. (2014). Mobile technology in mobile work: contradictions and congruencies in activity systems. European Journal of Information Systems, 23(5), 529-542.

- Karanasios, S., Allen, D. & Finnegan, P. (2015). Activity theory in information systems research. Information Systems Journal, 25(3), 309-313.

- Karanasios, S., Thakker, D., Lau, L., Allen, D., Dimitravo, V. & Norman, A. (2013). Making sense of digital traces: an activity theory driven ontological approach. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(12), 2452-2467.

- Karpatschof, B. (2000). Human activity - contributions to the anthropological sciences from a perspective of activity theory. Copenhagen: Dansk Psykologisk Forlag. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/12-3/Karpatschof/Chapter_1a.pdf.

- Kashyap, D. (2018). Approaches to the study of organizational behavior. Retrieved from: http://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/organization/organizational-behaviour/approaches-to- the-study-of-organizational-behavior/63748.

- Krikelas, J. (1983). Information-seeking behaviour: patterns and concepts. Drexel Library Quarterly, 19(2), 5-20.

- Kumar, N., De Beer, J., Vanthienen, J. & Moens, M.F. (2005). Evaluation of intelligent information retrieval tools for unstructured police case reports. Paper presented at the Conferentie Informatiewetenschap, Belgium, Antwerp, 18 November, 2005. Retrieved from http://www.informatiewetenschap.org/CIW2005/papers/presentatie4.pdf

- Kuutti, K. (1996). Activity theory as a potential framework for human-computer interaction research. In B.A. Nardi (Ed.). Context and consciousness: activity theory and human-computer interaction (pp. 17-44). Cambridge, MA: MIT.

- Kowalski, G. (1997). Information retrieval system: theory and implementation. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Kwon, N. (2017). How work positions affect the research activity and information behaviour of laboratory scientists in the research lifecycle: applying activity theory. Information Research, 22(1), paper 744. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/22-1/paper744.html.

- Kyburz-Graber, R., Hofer, K. & Wolfensberger, B. (2006). Studies on a socio-ecological approach to environmental education – a contribution to a critical position in the education for sustainable development discourse. Environmental Education Research, 12(1), 101-114.

- Lasker, G.E. (1981). Applied systems and cybernetics. Vol 1. New York, NY: Pergamon.

- Liew, A. (2007). Understanding data, information, knowledge and their inter-relationships. Journal of Knowledge Management Practice, 8(2). Retrieved from http://www.tlainc.com/articl134.htm

- Lothridge, K. & Fitzpatrick, F. (2013). Crime scene investigation a guide for law enforcement. Retrieved from https://www.nist.gov/sites/default/files/documents/forensics/Crime-Scene-Investigation.pdf.

- Loving, K. (2014). Solving yesterday today: cold cases. Retrieved from https://www.criminaljusticedegree.com/solving-yesterday-today-cold-cases/.

- Maceviciuté, E. & Wilson, T.D. (2008). Information behaviour in research network building by relocated scholars in Swedish higher education: a report on a pilot project. Information Research, 13(4), paper 371. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/13-4/paper371.html.

- Maguire, E.R., King, W.R., Johnson, D. & Katz, C.M. (2010). Why homicide clearance rates decrease: evidence from the Caribbean. Policing & Society, 20(4), 373-400.

- Malaurent, J. & Avison, D. (2015). Reconciling global and local needs: a canonical action research project to deal with workarounds. Information Systems Journal, 26(3), 227-257.

- McClellan, J (2007). Unsolved homicides: what we do and do not know. Journal of Security Education, 2(3), 53-69.

- Meintjes-Van der Walt, L. (2008). An overview of the use of DNA evidence in South African criminal courts. South African Journal of Criminal Justice, 21(1), 22-62.

- Meyer, H. (2016). Untangling the building blocks: a generic model to explain information behaviour to novice researchers. In Proceedings of ISIC, the Information Behaviour Conference, Zadar, Croatia, 20-23 September, 2016: Part 1. Information Research, 21(4), paper isic1602. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net /ir/21-4/isic/isic1602.html.

- Mishra, J., Allen, D. & Pearman, A. (2015). Information seeking, use, and decision making. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(4), 662-673.

- Mursu, Á., Luukkonen, I., Toivanen, M. & Korpela M. (2007). Activity theory in information systems research and practice - theoretical underpinnings for an information systems development model. Information Research, 12(3), paper 311. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/12-3/paper311.html.

- Nardi, B.A. (1996). Activity theory and human computer interaction. In B.A. Nardi (Ed.). Context and consciousness: activity theory and human-computer interaction (pp. 1-8). Cambridge, MA: MIT.

- Nardi, B.A. (2005). Activity theory and human-computer interaction. Retrieved from http://ics.uci.edu/~corps/phaseii/nardi-ch1.pdf.

- Nardi, B. & O'Day, V.L. (1998). Information ecologies: using technology with heart. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

- National Sheriffs’ Association. (2011). Serving survivors of homicide victims during cold case investigations: a guide for developing a law enforcement protocol. Retrieved from http://www.pomc.org/docs/guidefordevelopingalawenforcementprotocolaugust172011.pdf

- Nowé, K., Maceviciuté, E. & Wilson, T.D. (2008). Tensions and contradictions in the information behaviour of Board members of a voluntary organization. Information Research, 13(4), paper 363. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/13-4/paper363.html.

- Pena-Ayala, A., Sossa, H. & Mendez, I. (2014). Activity theory as a framework for building adaptive e-learning systems: a case to provide empirical evidence. Computers in Human Behavior, 30, 131-145.

- Pivnick, J., Wise, E. & Alberta, C. (2003). In search of an ecological approach to research: a meditation on topos. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 8. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ881754.pdf.

- Omar, B. (2008). Are we taking physical evidence seriously? The SAPS criminal record and forensic science service. SA Crime Quarterly, 23(March), 29-36.

- Rapp, B. (2005). Homicide investigation a practical handbook. Port Townsend, WA: Loompanics Unlimited.

- Roach, J. (2017). The retrospective detective: cognitive bias and the cold case homicide investigator. Papers from the British Criminology Conference. 17. Retrieved from http://www.britsoccrim.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/The-Retrospective-Detective.pdf.

- Robson, A. & Robinson, L. (2013). Building on models of information behaviour: linking information seeking and communication, Journal of Documentation, 69(2), 169-193.

- Roos, A. (2012). Activity theory as a theoretical framework in the study of information practices in molecular medicine . Information Research, 17(3), paper 526. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/17-3/paper526.html#.Wqe0AmpuaCg.

- Rossmo D.K. and Summers L. (2015). Routine activity theory in crime investigation. In M.A. Andresen and G. Farrell (Eds), The criminal act (pp. 19-32). London: Palgrave Macmillan. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9781137391322_3.

- Roufa, T. (2017). Explore a career as a cold case investigator. Retrieved from https://www.thebalance.com/explore-a-career-as-a-cold-case-investigator-974509.

- Ruthven, I. & Kelly, D. (2011). Interactive information seeking, behaviour and retrieval. London: Facet.

- Saracevic, T. (2011). Foreword. In I. Ruthven & D, Kelly (Eds.). Interactive information seeking, behaviour and retrieval (p. xxv - xxxii). London: Facet.

- Sawchuk, P.H, Duarte, N. & Elhammoumi, M. (2006). Critical perspectives on activity: explorations across education, work, and everyday life. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Schefcick, P.E. (2004). The information seeking behavior of private investigators: a study of investigators in North Carolina and Georgia. Unpublished Master's thesis, School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA. Retrieved from https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/indexablecontent/uuid:9b28afe7-e378-4f5f-b03c-2ef3fed90576

- Soergel, D. (1985). Organizing information: principles of data base and retrieval systems. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Sonnenwald, D.H. (Ed.) (2016). Theory development in the information sciences. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Spasser, M.A. (1999). Informing information science: the case for activity theory. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 50(12), 1136-1138.

- Spasser, M. (2007). Issue editorial. Information Research, 12(3), editorial GE123. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/12-3/geditor123.html.

- Spinuzzi, C. (2012). Working alone together: coworking as emergent collaborative activity. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 26(4), 399-441.

- Steinerová, J. (2010). Ecological dimensions of information literacy. Information Research, 15(4), paper 719. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/15-4/colis719.html.

- Steinerová, J. (2012). Information ecology as a framework for reconsidering information usage. Mousaion, 30(1), 87-102.

- Stichweh, R. (2013). Systems theory. In International Encyclopedia of Political Science (pp.1-8). Retrieved from https://www.fiw.uni-bonn.de/demokratieforschung/personen/stichweh/pdfs/80_stw_systems-theory-international-encyclopedia-of-political-science_2.pdf

- Thakur, D. (2017). What is systems approach? Definition and meaning. Retrieved from http://ecomputernotes.com/mis/information-and-system-concepts/systemsapproach.

- Toms, E. G. (2011). Task-based information searching and retrieval. In I. Ruthven & D, Kelly (Eds.). Interactive information seeking, behaviour and retrieval (pp. 43-59). London: Facet.

- United Nations. (2003). Manual for the development of a system of criminal justice statistics. New York, NY: United Nations Publications.

- United Nations. (2011). Criminal intelligence manual for analysts. Vienna: Publishing and Library Section.

- Vakkari, P. (1999). Task complexity, problem structure and information actions integrating studies on information seeking and retrieval. Information Processing and Management, 35(6), 819-837.

- Van Asselt, T.C. (2017). Heating up cold cases: a qualitative international research towards best practices in the cold case approach, commissioned by Berenschot. Unpublished master's thesis, Social and Behavioural Science of the Utrecht University at Heidelberglaan, Utrecht, The Netherlands. Retrieved from https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/354063.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Walton, R. H. (2014). Practical; cold case homicide investigations procedural manual. London: CRC Press.

- Williamson, K. (1998). Discovered by chance: the role of incidental information acquisition in an ecological model of information use. Library & Information Science Research, 20(1), 23-40.

- Widén-Wulff, G. & Davenport, E. (2007). Activity systems, information sharing and the development of organizational knowledge in two Finnish firms: an exploratory study using activity theory. Information Research, 12(3), paper 310. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/12-3/paper310.html

- Wilson, T.D. (1999). Models in information behavior research. Journal of Documentation, 55(3), 249-271.

- Wilson, T.D. (2006). A re-examination of information seeking behaviour in the context of activity theory. Information Research, 11(4). Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/879f/84dbe91e8b871a6c21002dbcced4d913c501.pdf.

- Wilson, T.D. (2008). Activity theory and information seeking. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 42, 119-161.

- Wise, J.A. (1999). The ecological approach to text visualization. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 50(13), 1224-1233.

- Xie, I. (2002). Patterns between interactive intentions and information-seeking strategies. Information Processing and Management, 38(1), 55-77.

- Xie, I. (2006). Evaluation of digital libraries: criteria and problems from users' perspectives. Library & Information Science Research, 28(3), 433-452.

- Xu, Y. (2007). The dynamics of interactive information retrieval behavior. Part I: An activity theory perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(7) 985-970.

- Xu, Y. & Liu, C. (2007). The dynamics of interactive information retrieval. Part II: An empirical study from the activity theory perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(7), 987–998.