Information horizons mapping to assess the health literacy of refugee and immigrant women in the USA

Margaret S. Zimmerman

Introduction. Refugees and immigrants are at a heightened risk of many negative health outcomes. Whilst strong health literacy ability may be a determinant of favourable health outcomes, assessing the health literacy of refugee and immigrant women is a challenge. Owing to typically lower literacy and English ability, one possible method to measure the health literacy of this population is to ask them to graphically represent their health-related information horizons.

Method. Seventy-four women were asked to take a survey and answer open-ended questions about their health information seeking behaviour and demographic information. They were then asked to create an information horizons map in the context of health information seeking.

Analysis. Each map was compared to the survey questions and specific questions were asked to gauge the health literacy of the participants. Using Sonnenwald’s methodology, the network of information resources for immigrant and refugee women was graphically displayed.

Results. Women who drew more complex maps had survey responses that correlated with higher health literacy and eHealth literacy. Refugee women were less aware of health information sources than other immigrant women.

Conclusions. Whilst more research is needed, this research provides evidence that information horizons mapping within a health information seeking context may be predictive of health literacy.

Introduction

Refugees and immigrants in the United States are at a heightened risk of a number of negative health outcomes, including diabetes, obesity, chronic disease and mental health disorders (Im and Rosenberg, 2016; Nelson-Peterman, Toof, Liang and Grigg-Saito, 2015). Owing to displacement and acculturation stress, newly resettled refugees are unlikely to have access to, or the ability to seek, necessary information and care requisite to good health. Despite arriving at healthy weights, immigrants to the United States experience an increase in obesity and health conditions, and an overall deterioration in self-reported health (Antecol and Bedard, 2006). Both groups have an increased risk for delayed uptake of prenatal care (Kentoffio, Berkowitz, Atlas, Oo, and Percac-Lima, 2016). In an increasingly polarised climate, studies have shown a direct relationship between anti-immigration policies and their effects on access to health services (Martinez, 2015).

There is a body of literature stating that successful health information seeking behaviour is dependent upon strong health literacy skills, and that proficient health literacy by a woman is a determinant of favourable health outcomes for both herself and her children (Lloyd, 2014; Wångdahl, Lytsy, Mårtensson, and Westerling, 2014; Zimmerman, 2017). Despite evidence that refugees and immigrants need improved health literacy skills, this significant issue has received little scholarly attention. Aligned with this, conducting assessments to determine the health literacy of immigrants and refugees, a requisite step in addressing health literacy needs, is a continuous challenge.

The objective of this study is to explore the potential of an alternative methodology of assessing health literacy for immigrant and refugee populations through information horizons mapping. In meeting this objective, the following research questions will be considered:

What are the sources and channels of information seeking used by refugee and immigrant women?

What comparisons can be made between their information seeking behaviour and other indicators of health literacy?

Do the breadth of their information horizons maps reflect consistency with these other indicators of health literacy?

Information horizons mapping is a method developed by Sonnenwald, Wildemuth, and Harmon in 2001, which combines interview data with participant-drawn graphical representations of recent information seeking experiences situated within specific contexts. By comparing the graphical maps with the interview data, the researchers are able to analyse the information horizons, or contextually-based information resources, for individuals and aggregate them for specific populations within a context (Sonnenwald, 1999).

In this study, women were asked to take a survey and answer open-ended questions about their health information seeking behaviour and demographic information, and then asked to create an information horizons map in the context of health information seeking (see Appendix B). As these populations traditionally have lower literacy levels and limited understanding of English, drawing their knowledge spaces is theorised to be a method that may offer further expression beyond written language to immigrant and refugee women. Literature about health literacy assessment was evaluated, and questions previously validated as being significant measures of health literacy were included on the survey. These responses were compared to the maps and demographic data in an attempt to determine both the women’s individual and collective information horizons and look for corresponding assessment of health literacy. By doing so, this study both employed and expanded upon the information horizons research method used by Sonnenwald, Wildemuth, and Harmon in 2001 to evaluate the potential for this method to be used as a platform by which to examine the health literacy of the participants.

Background

To devise a method using information horizons mapping to assess health literacy, the background of both concepts must be explored. The current sources and channels of health information for refugees and immigrants also bear examination. The following section provides a snapshot of literature on refugee and immigrant information sources, health literacy assessments germane to this research, and a few relevant studies that have employed Sonnenwald’s information horizons mapping.

Sources and channels of refugee and immigrant health information-seeking

Immigrants experience significant language and cultural barriers upon immigration to their resettlement country. Whilst the importance of quality health information is generally understood, newly arrived immigrants often lack knowledge of where to obtain this information and frequently end up utilising sources of convenience, such as friends and family (Silvio, 2006). Mistrust and perceived discrimination from sources are a significant barrier to refugees and immigrants (Asgary and Segar, 2011), providing another reason to seek health-related information within one’s own social network. Because of this, because of the size of the immigrants’ interpersonal network in their new country, these personal sources may also be family in their home country (Chen, Kendall, and Shyu, 2010). Because of the limited scale of social networks some immigrants, and particularly refugees by the nature of their displacement, may run the risk of suffering network poverty, which can hinder their access to health information (Vinson, 2009).

Media directed to significant immigrant groups, such as ethnically-targeted television, is another channel by which some immigrant groups, such as Latinos, prefer to consume health information. In one United States study, a significant relationship was found between television as a primary source of health information and both insurance status and poverty. Those immigrants that were uninsured and poor were more likely to rely upon Hispanic programming as a primary source of health information (Cheong, 2007). This is unfortunate, as television has typically been found to be a less reliable source of information, contributing to knowledge gaps between populations with differing levels of socioeconomic status (Robinson, 1972).

Despite the fact that the Internet has become a direct channel to facilitate health information seeking, eHealth resources are utilised disproportionately by those with higher education and incomes and there is a significant racial divide (Cotton and Gupta, 2004; Kontos, Blake, Chou, and Prestin, 2014). As a result, health information on the Internet is often written at a very high level (Mcinnes and Haglund, 2011) that may be beyond the ability of many immigrants and refugees. As an example, in one study of Hispanic immigrants who were not comfortable speaking English, only fourteen per cent reported use of the Internet for health information seeking (Clayman, Manganello, Viswanath, Hesse, and Arora, 2010). As a further complication, there is still a significant digital divide for immigrants and refugees in both access and ability (Alam and Imran, 2015; Changrani and Gany, 2005).

Whilst there are some studies that have found that specific communities prefer medical professionals for health information (Britigan, Murnan, and Rojas-Guyler, 2009), the majority of scholarly research still confirms that personal channels are the first and most significantly used information sources for immigrant and refugee populations (Courtright, 2005).

Thus, research has found that refugees tend to absorb health information in primarily non-textual ways (Lloyd, 2014). Given limited language, cultural understanding, and literacy, refugees often digest information by taking it in through a myriad of sources in everyday settings, called knowledge spaces. This concept, the idea that refugees are a part of a greater landscape of information that they process, but may not have the language to describe, gives credibility to the idea that graphical mapping may be a beneficial tool by which they can further describe their health information horizons.

Health literacy and assessment

The Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Health Literacy, defines health literacy as, 'The degree, to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions'. (Nielsen-Bohlman, Panzer, Hamlin, and Kindig, 2004, p. 31). Health literacy is dependent upon the individual's health-related reading level and familiarity with relevant vocabulary and concepts, in addition to the environmental supports of the system in which they find themselves (Baker, 2006). As an individual ability, health literacy is a progression of high-level skills including critical thinking, decision making, information seeking, and ultimately, communication with health-related materials and health-care workers (Mancuso, 2009). Given the breadth of requisite capabilities, health literacy as an aptitude is difficult to measure.

There are many tools that attempt to do so, however, and they vary greatly in length, delivery, and skills assessed. The Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA) and the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) are most consistently held up as being the gold standard in health literacy evaluation (Baker, 2006; Dumenci, Matsuyama, Kuhn, Perera, and Siminoff, 2013; Paasche-Orlow, Parker, Gazmararian, Nielsen-Bohlman and Rudd, 2005). The Test of Functional Health Literacy is a written test that consists of fifty reading comprehension items and a seventeen-item subscale to measure numeracy. It takes up to twenty-two minutes to administer.

The Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy consists of 125 medical terms listed in order of increasing difficulty that the test takers are asked to read aloud. The total score is the number of correctly pronounced words converted into an equivalent grade level. If a patient scores less than a 9th grade level, it is assumed that they are likely to have difficulty with patient education materials.

While these methods have been considered the best for health literacy testing, many simpler assessment tools have been created and tested against these in the literature, with varying degrees of success. In particular, scores on the Brief Health Literacy Screen (BHLS) have been found to correlate with the shortened version of the Test of Functional Health Literacy (STOFHL), which patients rated as less difficult to complete (Sand-Jecklin and Coyle, 2014). It is composed of five questions that have Likert scale responses. These questions ask about the difficulty the patient has in understanding clinicians, forms, and written information. The responses are tallied for an overall health literacy rating, which has been demonstrated to be consistent with the results of the Rapid Estimate test.

These tests, however, have been criticised for measuring health literacy as purely an estimate of the participants reading literacy, while not evaluating the larger breadth of skills requisite to good health literacy (Baker, 2006; Berkman , 2004; Jordan, Osborne, and Buchbinder, 2011). As a result, additional health literacy assessments have been created that not only assess literacy and numeracy, as is the case with the Test of Functional Health Literacy, but also skills and tasks associated with good health literacy. An example of this is the Health Literacy Skills Instrument (McCormack, 2010).

Determining patient comfort in understanding written information was also a component of another study that sought to develop fast and precise screening questions to identify patients with low health literacy (Chew, Bradley, and Boyko, 2004). Sixteen questions were asked and their responses were compared with the results of their Short Test of Functional Health Literacy. Specifically, in the assessment patients were asked, "How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition because of difficulty understanding written information?: Responses to this question were found to be effective in detecting patients with inadequate health literacy (Chew, Bradley, and Boyko, 2004). Positive internal consistency was found with a similar measure (Chinn and McCarthy, 2013) in which patients were asked if they needed help, were they able to consistently find someone to assist them, if they trusted clinicians, and if they understood their interactions with healthcare workers. Patient results for this measure were not correlated with other instruments to confer validity, but literature was cited that confirmed the association of the questions chosen with functional health literacy. This measure also gauged patient trust in information they receive about their health, although this question did not have the same degree of internal consistency. The results of this study also positively correlated health literacy scores with patient self-reported general health ratings (Chinn and McCarthy, 2013).

The majority of health literacy assessments available are predominantly for English speakers, with the Rapid Estimate and the Test of Functional Health Literacy having been translated to a small number of other languages. However, these do not meet the needs necessary to represent the abundance of languages spoken by refugee communities in the United States. Given the complex nature of these assessments, there is also concern about the validity of translated tools owing to differences in context, culture, and phonetic structure (Mancuso, 2009). The assessment questions described above that ask the patient about their comfort level in understanding clinicians and written health information are simple and easily translated. More importantly, those that have been translated still demonstrate success in health literacy evaluation (Chakkalakal, 2017; Mantwill and Schulz, 2015).

Information horizons mapping

Since Sonnenwald, Wildemuth, and Harmon published their ground-breaking paper in 2001, it has been cited 113 times. The actual method has been employed multiple times in the literature to explore the information horizons of first-generation college students (Tsai, 2012); Internet users in the context of self-development (Savolainen, 2007); and the relationship of information horizons mapping to information literacy (Steinerová, 2014). The concept of the original paper is complex. Sonnenwald’s theoretical framework describes a horizon that simultaneously constrains and facilitates information behaviour: behaviour inclusive of social networks and contexts (Sonnenwald, 1999). The method she developed to illustrate and analyse information horizons involves a multistep process in which participants are asked to describe information seeking experiences within a specific context and draw a map of the steps they took to find information (Sonnenwald, Wildemuth, and Harmon, 2001). This graphical representation of the participants’ information horizon is then compared to interview data to show congruence between the maps and the participants’ narratives. Finally, maps of all participants are compared to show the group’s preferences for information resources; information that can then be used to create further graphical representations of the group’s network of information resources.

In 2014, this method was applied to a group of PhD students in an effort to draw comparisons between information horizons maps and their information literacy (Steinerová, 2014). Steinerová wrote that information horizons were influenced by levels of knowledge of the students, and their information literacy. Analysing the patterns found in the maps and interview data, resources used by the students were divided into starting resources, reference resources, and focusing resources. Patterns of information use were detected and Steinerová was able to formulate new contexts of information literacy based upon the study.

Huvila (2009) employed the method with archaeology professionals to analyse information behaviour related to their work roles. Using the term analytical information horizon maps, researchers drew diagrams of professional resources and information activities of the collective. Huvila was able to determine that the method is beneficial for describing and communicating common information behaviour within a professional group.

This method has also been expanded in a concept called information source horizons, which uses the original mapping method and asks that participants group sources into levels, or zones, of preference (Savolainen and Kari, 2004). Individuals were encouraged to imagine any information sources that may be helpful in seeking, then to position them graphically by proximity to themselves as a seeker and by perceived helpfulness. This focus on source preference gives a more robust concept of the information horizon of the individual participants and the group.

Finally, information world mapping, as Greyson and colleagues referred to it in their 2017 study, is based on Sonnenwald’s information horizons and was found to be a useful method to conceptualise the social information worlds of low-literacy-level youth in the context of health information practices (Greyson, O'Brien, and Shoveller, 2017). Participants were asked to draw themselves, then draw all aspects that they could of their information worlds. Suggestions were offered based upon the participants’ own narratives from the preceding interview and involved information behaviour such as seeking, receiving, and sharing information. The authors found that this method allowed for the triangulation of rich data to complement the interview data. It was concluded that this was a valuable means by which to 'centre the perspectives of a socially-marginalised population' (Greyson, O'Brien, and Shoveller, 2017, p. 156).

In addition to these examples, this method, or variations of it, have been employed repeatedly within the research literature graphically conceptualise information seeking behaviour within assorted contexts. It has been found useful in determining the information landscape (Lloyd, Kennan, Thompson, and Qayyum, 2013) of refugee populations. Further, graphical representations of knowledge have long been deemed useful in aiding those with low-literacy levels (Buki, Salazar, and Pitton, 2009; Houts, Doak, Doak, and Loscalzo, 2006; Kripalani, 2007).

Method

After receiving institutional approval, participants were recruited through refugee and immigrant organizations in Charlotte, North Carolina and in several locations in Iowa. A convenience sample of refugees was recruited for the study. Adult women were approached at organizational events and asked if they would like to participate: seventy-four women who agreed. Each was given a survey with a consent form that was available in English, Spanish, French, Swahili, and Arabic. The consent form described the research being conducted, the inclusion criteria, the risks and remuneration, and gave the contact information of the University of Iowa Human Subjects Office. The survey was based upon previously published and validated instruments (Britigan, 2009; White, 2016; Zimmerman, 2017). It contained questions about the participant’s health information seeking behaviour including source preferences, her demographic information, and instructions to create an information horizons map. Included in the survey were questions that have been demonstrated to be predictive of health literacy, including:

a woman’s self-reported ability to find the information that she was looking for when she had questions about health;

whether or not she was able to understand the information she found;

her personal rating of her overall health.

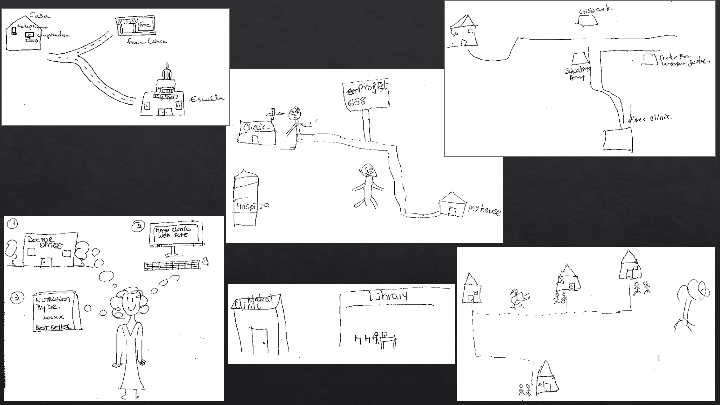

The study participants were asked to draw a picture of where they would go, who or what they would consult, and in what order, if they needed information about health. Specifically, they were asked to draw their information sources and the order in which they would go to them as if it were a map from leaving their house. Participants were instructed to show preference, and to draw as many places to look for information as they could. Of the seventy-four women that completed a survey, sixty-five drew an information horizons map. Following the administration of the survey, each information horizons map was analysed both independently and congruent to the demographic information and responses in the survey. Maps were first examined to graphically describe the network of information resources for immigrant and refugee women. Then, the maps were studied along with various potential indicators of information access and health literacy, in an attempt to determine if the information horizons maps had any predictive qualities. Examples of the maps are shown in Appendix A.

Analysis

Each map was scanned into pdf form and analysed independently. The individual information sources that each woman drew were counted and documented. If a participant drew a picture of seeking information by walking first to a friend’s house, then to the library to access information over the Internet, and then to a free clinic to talk with a healthcare worker, the participants were thereby drawing three sources. Each of these was counted and ranked into order of preference. First, the information sources that each woman listed were compiled into a matrix using the method Sonnenwald (2001) employed in the previously cited paper. In this matrix, the rows represent the sources employed by each woman and the columns represent each participant. The numbers in the individual cells of the matrix represent the order of preference for each information source. In the example above, the friend’s house would have a one, the Internet would have a two, and the clinic would be listed as three. If the drawings were unclear, as several were, the survey would be consulted. If this also was unhelpful, the map was not included. Of the sixty-five drawings, eight were too unclear to determine the order of preference and were left out of this part of the analysis.

After building the matrix described above, the links between each of the information sources were compiled into a chart detailing the total times each was mentioned, the total number of links, the unique links, the outgoing links, and the incoming links as in Sonnenwald’s method. Using this process, each node, or point of information, type was determined. They were grouped into categories of starting nodes, i.e., the beginning point of the intended search; focusing nodes, i.e., those with more incoming than outgoing links; recommending nodes, i.e., those with more outgoing than incoming links; balanced nodes, i.e., those with an equal number of incoming and outgoing links; and ending nodes, i.e., those terminating the intended search process./p>

The final step of this part of the method was that in using this information, the network of information resources for immigrant and refugee women, and specifically the stronger connections among those information resources, were graphically represented.

Results

Fifty-seven drawings are represented in the matrix that resulted from the foregoing analysis, Table 1:

| Sources | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Free clinic | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Crisis centre | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Community organization | 2,3 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Library | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Family | 1 | 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Friend | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Internet | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| School | 4 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Church | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Books and pamphlets | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Newspaper | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharmacy | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Doctor | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | |

| Hospital | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Free clinic | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Crisis centre | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Community organization | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Library | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Family | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Friend | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Internet | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| School | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Church | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Books and pamphlets | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Newspaper | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharmacy | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Doctor | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

The matrix above was analysed to determine each node type, as described in the analysis section: see Table 2:

| Node type | Total times mentioned | Total no. of links | Unique links | Outgoing links | Incoming links | Node type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinic | 29 | 24 | 9 | 10 | 14 | Focusing |

| Friend or family | 14 | 13 | 5 | 10 | 3 | Recommending |

| Hospital | 14 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 7 | Focusing |

| Internet | 13 | 16 | 9 | 9 | 7 | Recommending |

| Library | 9 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 3 | Recommending |

| Pharmacy | 7 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 4 | Focusing |

| Doctor | 7 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | Balanced |

| Community centre | 4 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 | Recommending |

| Church | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | Balanced |

| School | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 3 | Focusing |

| Crisis centre | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | Starting |

| Newspaper | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | Balanced |

| Books and pamphlets | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | Ending |

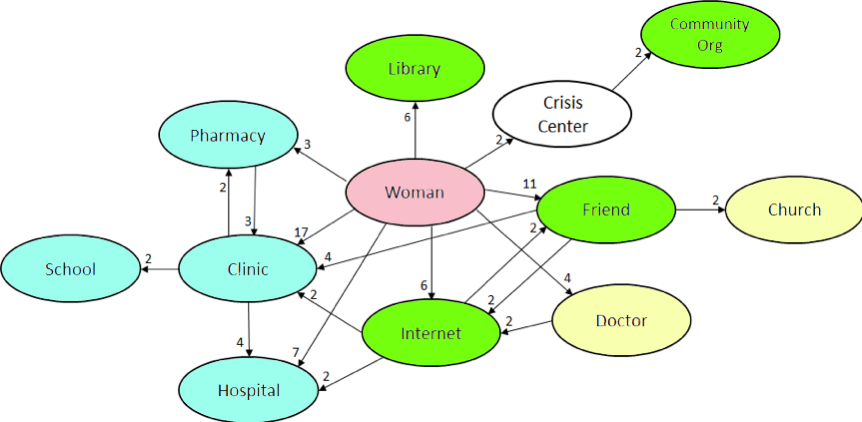

Finally, the first two tables were synthesised to graphically represent the network of information resources for immigrant and refugee women, displayed in Figure 1. The arrows point the direction of the information seeking between the sources, while the numbers represent the number of times this path was mentioned; newspapers and books and pamphlets are excluded from the table because they were so infrequently mentioned. The colours represent the node types, as in Table 2.

Figure 1: The network of information resources for immigrant and refugee women

Following this analysis, the current research deviated from Sonnenwald’s method. Next, the number of sources each woman drew was compared with the demographic and information seeking data that was collected through the survey. Specifically, drawings were grouped by years of education, frequency of Internet use, medium of Internet access, number of years living in the United States, and if the participant came into the United States under refugee status. The purpose of this analysis was to determine if any of these factors had correlative or influential relationships on the participants’ vision of their own information horizons. Correlation was measured, where appropriate, by Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

The number of sources on the information horizons maps was also compared with the participant’s self-reported ability to find the information that she was looking for when she had questions about health; whether or not she was able to understand the information she found; and her personal rating of her overall health. As discussed above, each of these questions potentially has correspondence with the women's health literacy.

Information horizons maps were received from 65 immigrant women, 25 of whom had refugee status. The participants ranged in age from 18 to 68 years old, with the average age of the group being 37.6 years. Fifteen of the women had never married, 52 women were currently married, and 15 were divorced. Three women chose not to answer. Only three participants did not have children. The respondents were similar in respect of the size of the family, the average number of children being 3. The women had lived in the United States an average of 8.7 years, though there was great variance in this number, with several participants having lived in the US just a few months and some for more than 20 years. Years of schooling also showed a large fluctuation. The average years of schooling for the group was through ninth grade. However, several women had college degrees and eight had not completed enough years of schooling to have finished elementary school. Only fourteen of the participants reported having no access to the Internet.

Years of schooling also showed a large fluctuation. The average years of schooling for the group was through 9th grade. However, several women had college degrees and eight had not completed enough years of schooling to have finished elementary school. Only fourteen of the participants reported having no access to the Internet.

When comparing the number of sources each woman drew in comparison to her years of schooling, there was a strong correlative relationship (r=0.924). There was also a strong relationship (r=0.885) between a woman’s frequency of Internet use and the number of sources she drew. There was no correlation between the number of sources women drew and either their number of years having lived in the United States or whether they accessed the Internet through their phone, a personal computer, tablet, or a borrowed device from outside of the home. Immigrant women who did not enter the United States under refugee status drew nearly twice the number of sources (n=2.25) that women who did enter the United States under refugee status drew (n=1.32).

Regarding the comparison of the drawn sources to the questions that may be predictive of health literacy, women who drew five sources were twice as likely to report that they were able to find health information that they needed than women who drew one source. These women also tended to have a more favourable report of their own health, with an average ranking of 3.5 as opposed to the 2.9 average of women that listed one source. Approximately half of the women (n=15) who drew one or two information sources felt that they could access and understand information when they needed it. Ten of the women also cited distrust in medical professionals and seventeen women stated that they did not trust information they found on the Internet.

Discussion

The outcome of this analysis is compelling in that it demonstrates potentially predictive qualities of information horizons mapping in two ways. First, there is support within these results for the potential of information horizons mapping methodology to be predictive of health literacy for refugee and immigrant women. Second, there is a clear parallel between the complexity of these maps and the illustrators’ years of schooling and Internet usage. These results provide support for a relationship between health literacy and educational attainment. This is significant, as it demonstrates the correlative effect of schooling on the participant’s knowledge of health-related resources available to them.

In examining the complexity of the information horizons maps of the participants, there was nearly perfect correlation with their years of schooling. As the participants drew more sources of information that they would use to gather information about their health, their number of years of education was found to be higher. This was interesting, as the participants being measured had an average of 9.5 years of schooling, with eight having had less than five years of school, and eight possessing graduate degrees. With the spectrum of educational attainment being so well-represented by this sample, this methodology could provide near perfect correlation between the participant’s representation of information resources and their educational attainment. This is significant and a point that urges further study and examination. Why is it that the participants who have completed more years of schooling are also more aware of their resources? Educational attainment is not necessarily a predictor of information literacy, and it cannot be assumed that the participants who drew more sources are necessarily more information literate based upon these findings. Regardless, it is clear from the results of this research that there is a relationship between the number of resources drawn through information horizons mapping and the educational attainment of the participants of this study.

Frequency of Internet usage, however, has been demonstrated to be predictive of the ability to use the Web to one’s benefit and to find information more easily (Broos, 2005; Hargittai and Hinnant, 2008). Multiple studies have positively correlated frequency of Internet use with an increase in eHealth literacy (Choi and DiNitto, 2013; Neter and Brainin, 2012; Tennant, 2015). The correlation between the number of information resources that the participants drew and the frequency with which they use the Internet was extremely strong, almost as strong as that with their years of schooling. While this certainly bears further examination, this finding may point to the possibility that women who draw more resources through information horizons mapping are not only more aware of the sources around them, but are more likely to use the Internet competently and that they potentially have higher eHealth literacy.

Returning to the first point, these results do indicate the potential of information horizons mapping methodology to be predictive of health literacy for refugee and immigrant women. There is clear consistency when comparing the information sources drawn with the questions that had been validated as significant measures of health literacy. The participants who drew more health information sources had an increased likelihood to report that they were able to access the health information that they needed. This demonstrates a comfort with navigating and understanding health information resources that agrees with the health literacy assessments mentioned above. There is a similar agreement in the finding that the participants who drew maps that were more complex also had a more favourable report of their own health. A consistency has been found between health literacy ability and self-reported general health ratings (Chinn and McCarthy, 2013). These measures confirm the possible capability for information horizons mapping to be indicative of health literacy.

Similarly, the participants who drew fewer information sources only reported a 50 per cent likelihood that they could access information that they were able to understand when they needed it. This finding is consistent with the questions in the Brief Health Literacy Screen regarding the difficulty the patient has in understanding clinicians, forms, and written information. It also corresponds with the measure employed by Chinn and McCarthy (2013) that participants who were measured as having lower health literacy had more difficulty consistently finding help and were less likely to understand their interactions with healthcare workers. Once again, this measure gauged patient trust in information that they received about their health as a measure of health literacy. In this study many, though not the majority of participants, also cited distrust in medical professionals. The participants stating that they distrusted medical professionals also listed fewer information resources on their information horizons maps, used the Internet less often, and were below the participant average for years of schooling attended. While further research is needed, these measures may indicate lower eHealth literacy and comfort with informational resources.

Another point that bears discussion is the finding that the participants who entered the United States under refugee status drew approximately half the number of health-related sources that the participants of immigrant status drew. This is alarming because it demonstrates that the participants who are brought in through refugee support organisations are less aware of the resources available to them than those who enter the United States by other means and not necessarily with organizational aid. As these refugees are offered community assistance networks and aid with resettlement, it would be assumed that they would be more, not less, aware of support and informational resources. However, that is not demonstrated through the findings of this study. In a particularly poignant example, discussions identified a refugee woman who had been living in Charlotte, NC for two years and was unaware of a free immigrant health clinic across the street from the community organisation where she participated in this study and had not been seen by a doctor in the time she had been in the United States. While further examination of this point is needed, the finding that women entering the country as refugees are under-aware of where to get healthcare and information may prove to be consistent through further research. This is a clear call to provide newly resettled refugees with interventions to teach them how to navigate the health information sources available to them.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is that it was a convenience sample of immigrant and refugee women. Therefore, the results cannot be generalised to a larger population. Also, the results would be more robust if participants were more thoroughly evaluated for health literacy in addition to being evaluated using information horizons mapping. While several of the survey questions correlated with previously validated health literacy screening tools, the participants were not thoroughly evaluated for health literacy. In future iterations of this research, participants should be evaluated using a traditionally utilised and vetted screening tool to produce the most accurate possible assessment of their health literacy.

It also must be acknowledged that only refugees and immigrants in the United States were assessed. A larger and more diverse sample certainly would have provided a more accurate examination of the abilities of information horizons mapping to examine health literacy. Evaluating the results with refugee populations in other parts of the world would provide further evidence of the efficacy of this method.

Conclusion

This was a preliminary study into the potential of information horizons mapping to be a method that may be employed to measure the health literacy of immigrant and refugee populations. As an alternative, information horizons mapping could be of great benefit to those that are typically poorly represented by traditional assessment tools. Drawing knowledge spaces maps may provide an opportunity for non-native speakers and those with limited literacy to graphically represent their information seeking abilities, therefore providing a more complete picture of the information behaviour of groups that are typically marginalised by tools like the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine and the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults.

As a beginning, this study did demonstrate positive results. Using the method, the participants who were more likely to have higher health literacy, according to measures used by other means of assessment, were also more likely to draw information horizons maps of higher complexity; just as those who are likely to have lower health literacy ability are likely to draw simpler maps. Findings from this study indicate that women entering the US under refugee status may be less likely to know of the health information resources available to them than other immigrant women. However, this research is a first step into understanding the capability of this method in providing assessment of health literacy. Much more research is needed before validating this as a trusted tool in this arena. As mentioned above, Sonnewald’s method should be evaluated against formal health literacy testing. More robust results would be produced if information horizons mapping was also tested in application to other populations.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided by the University of Iowa School of Library and Information Science.

About the author

Dr. Margaret Zimmerman is Assistant Professor, School of Library and Information Science, 3074 Main Library, The University of Iowa Iowa City, IA 52242-1420. Her doctorate in Library and Information Science is from the University of South Carolina. She also has a Master’s in Information Systems and a MLIS with a concentration in digital libraries, both from Drexel University. Her research areas of interest focus on the health-seeking behaviour and patterns of such behaviour of women of disadvantaged populations. Dr. Zimmerman studies the impact that information access, information literacy, and reading and literacy has had in affecting the health and well-being of the women she studies. She can be contacted at margaret-zimmerman@uiowa.edu

References

- Alam, K. & Imran, S. (2015). The digital divide and social inclusion among refugee migrants: a case in regional Australia. Information Technology & People, 28(2), 344-365.

- Antecol, H. & Bedard, K. (2006). Unhealthy assimilation: why do immigrants converge to American health status levels?. Demography, 43(2), 337-360.

- Asgary, R. & Segar, N. (2011). Barriers to health care access among refugee asylum seekers. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 22(2), 506-522.

- Baker, D.W. (2006). The meaning and the measure of health literacy. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(8), 878-883.

- Berkman, N.D., DeWalt, D.A., Pignone, M., Sheridan, S.L., Lohr, K.N., Lux, L.,... Bonito, A.J. (2004). Literacy and health outcomes. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments, No. 87). Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK37134

- Britigan, D.H. (2009). Health information sources and health literacy levels of latinos in a midwestern tri -state area. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Cincinnatti, Cincinnatti, USA. Retrieved from https://etd.ohiolink.edu/!etd.send_file?accession=ucin1258660537&disposition=inline

- Britigan, D.H., Murnan, J. & Rojas-Guyler, L. (2009). A qualitative study examining Latino functional health literacy levels and sources of health information. Journal of Community Health, 34(3), 222-230.

- Broos, A. (2005). Gender, information and communication technologies (ICT) anxiety: male self-assurance and female hesitation. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 8(1), 21-31.

- Buki, L.P., Salazar, S.I. & Pitton, V.O. (2009). Design elements for the development of cancer education print materials for a Latina/o audience. Health Promotion Practice, 10(4), 564-572.

- Chakkalakal, R.J., Venkatraman, S., White, R.O., Kripalani, S., Rothman, R. & Wallston, K. (2017). Validating health literacy and numeracy measures in minority groups. HLRP: Health Literacy Research and Practice, 1(2), e23-e30. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2DuYr8E

- Changrani, J. & Gany, F. (2005). Online cancer education and immigrants: effecting culturally appropriate websites. Journal of Cancer Education, 20(3), 183-186.

- Chen, C.J., Kendall, J. & Shyu, Y.I.L. (2010). Grabbing the rice straw: health information seeking in Chinese immigrants in the United States. Clinical Nursing research, 19(4), 335-353.

- Cheong, P. H. (2007). Health communication resources for uninsured and insured Hispanics. Health Communication, 21(2), 153-163.

- Chew, L. D., Bradley, K. A. &anol Boyko, E. J. (2004). Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Family Medicine, 36(8), 588-594

- Chinn, D. & McCarthy, C. (2013). All Aspects of Health Literacy Scale (AAHLS): developing a tool to measure functional, communicative and critical health literacy in primary healthcare settings. Patient Education and Counseling, 90(2), 247-253.

- Choi, N.G. & DiNitto, D.M. (2013). The digital divide among low-income homebound older adults: Internet use patterns, eHealth literacy, and attitudes toward computer/Internet use. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(5). Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3650931/

- Clayman, M.L., Manganello, J.A., Viswanath, K., Hesse, B.W. & Arora, N.K. (2010). Providing health messages to Hispanics/Latinos: understanding the importance of language, trust in health information sources, and media use. Journal of Health Communication, 15(sup3), 252-263.

- Cotten, S.R. & Gupta, S.S. (2004). Characteristics of online and offline health information seekers and factors that discriminate between them. Social Science & Medicine, 59(9), 1795-1806.

- Courtright, C. (2005). Health information-seeking among Latino newcomers: an exploratory study. Information Research, 10(2), paper 224. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net /ir/10-2/paper224.html

- Dumenci, L., Matsuyama, R.K., Kuhn, L., Perera, R.A. & Siminoff, L.A. (2013). On the validity of the shortened rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine (REALM) scale as a measure of health literacy. Communication Methods and Measures, 7(2), 134-143.

- Greyson, D., O'Brien, H. & Shoveller, J. (2017). Information world mapping: a participatory arts-based elicitation method for information behaviour interviews. Library and Information Science Research, 39(2), 149-157.

- Hargittai, E. & Hinnant, A. (2008). Digital inequality: differences in young adults' use of the Internet. Communication Research, 35(5), 602-621.

- Houts, P.S., Doak, C.C., Doak, L.G. & Loscalzo, M.J. (2006). The role of pictures in improving health communication: a review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Education and Counseling, 61(2), 173-190.

- Huvila, I. (2009). Analytical information horizon maps. Library & Information Science Research, 31(1), 18-28.

- Im, H. & Rosenberg, R. (2016). Building social capital through a peer-led community health workshop: a pilot with the Bhutanese refugee community. Journal of Community Health, 41(3), 509-517.

- Jordan, J.E., Osborne, R.H. & Buchbinder, R. (2011). Critical appraisal of health literacy indices revealed variable underlying constructs, narrow content and psychometric weaknesses. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(4), 366-379.

- Kentoffio, K., Berkowitz, S., Atlas, S., Oo, S. & Percac-Lima, S. (2016). Use of maternal health services: comparing refugee, immigrant and US-born populations. Maternal & Child Health Journal, 20(12), 2494-2501.

- Kontos, E., Blake, K.D., Chou, W.Y.S., & Prestin, A. (2014). Predictors of eHealth usage: insights on the digital divide from the Health Information National Trends Survey 2012. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(7), e172. Retrieved from https://www.jmir.org/2014/7/e172/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/747tMBAJX)

- Kripalani, S., Robertson, R., Love-Ghaffari, M.H., Henderson, L.E., Praska, J., Strawder, A. & Jacobson, T.A. (2007). Development of an illustrated medication schedule as a low-literacy patient education tool. Patient Education and Counseling, 66(3), 368-377.

- Lloyd, A. (2014). Building information resilience: how do resettling refugees connect with health information in regional landscapes – implications for health literacy. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 45(1), 48-66.

- Lloyd, A., Anne Kennan, M., Thompson, K.M. & Qayyum, A. (2013). Connecting with new information landscapes: information literacy practices of refugees. Journal of Documentation, 69(1), 121-144.

- McCormack, L., Bann, C., Squiers, L., Berkman, N. D., Squire, C., Schillinger, D. & Hibbard, J. (2010). Measuring health literacy: a pilot study of a new skills-based instrument. Journal of Health Communication, 15(S2), 51-71.

- Mcinnes, N. &qmp; Haglund, B. J. (2011). Readability of online health information: implications for health literacy. Informatics for Health and Social Care, 36(4), 173-189.

- Mancuso, J. M. (2009). Assessment and measurement of health literacy: an integrative review of the literature. Nursing & Health Sciences, 11(1), 77-89.

- Mantwill, S. & Schulz, P.J. (2015). Health literacy in mainland China: validation of a functional health literacy test in simplified Chinese. Health Promotion International, 31(4), 742-748.

- Martinez, O., Wu, E., Sandfort, T., Dodge, B., Carballo-Dieguez, A., Pinto, R., & Chavez-Baray, S. (2015). Evaluating the impact of immigration policies on health status among undocumented immigrants: a systematic review. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 17(3), 947-970.

- Nelson-Peterman, J.L., Toof, R., Liang, S. & Grigg-Saito, D.C. (2015). Long-term refugee health: health behaviours and outcomes of Cambodian refugee and immigrant women. Health Education & Behavior, 42(6), 814-823.

- Neter, E. & Brainin, E. (2012). eHealth literacy: extending the digital divide to the realm of health information. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(1), e19. Retrieved from https://www.jmir.org/2012/1/e19/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/747u7LDvb)

- Nielsen-Bohlman, L.T., Panzer, A.M., Hamlin, B. & Kindig, D.A. (Eds.). (2004). Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences. Board on Neuroscience and Behavioural Health, Institute of Medicine.

- Paasche-Orlow, M.K., Parker, R.M., Gazmararian, J.A., Nielsen-Bohlman, L.T. & Rudd, R.R. (2005). The prevalence of limited health literacy. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20(2), 175-184.

- Robinson, J.P. (1972). Mass communication and information diffusion. Current Perspectives in Mass Communication Research, 1, 304-319.

- Sand-Jecklin, K. & Coyle, S. (2014). Efficiently assessing patient health literacy: the BHLS instrument. Clinical Nursing Research, 23(6), 581-600.

- Savolainen, R. & Kari, J. (2004). Placing the Internet in information source horizons. a study of information seeking by Internet users in the context of self-development. Library & Information Science Research, 26(4), 415-433.

- Savolainen, R. (2007). Information source horizons and source preferences of environmental activists: a social phenomenological approach. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(12), 1709-1719.

- Silvio, D. (2006). The information needs and information seeking behaviour of immigrant southern Sudanese youth in the city of London, Ontario: an exploratory study. Library Review., 55(4), 259-266.

- Sonnenwald, D. H. (1999). Evolving perspectives of human information behaviour: contexts, situations, social networks and information horizons. In T.D Wilson and D.K Allen, (Eds.), Exploring the contexts of information behaviour: proceedings of the second international conference in information needs. London: Taylor Graham.

- Sonnenwald, D.H., Wildemuth, B.M. & Harmon, G. (2001). A research method using the concept of information horizons: an example from a study of lower socio-economic students’ information seeking behavior. The New Review of Information Behavior Research, 2, 65-86.

- Steinerová, J. (2014). Information horizons mapping for information literacy development. In Serap Kurbanoğlu, Sonja Špiranec, Esther Grassian, Diane Mizrachi & Ralph Catts, (Eds.), Information literacy. Lifelong learning and digital citizenship in the 21st Century, Second European Conference, ECIL 2014, Dubrovnik, Croatia, October 20-23, 2014. Proceedings (pp. 70-80). Cham, Switzerland: Springer

- Tennant, B., Stellefson, M., Dodd, V., Chaney, B., Chaney, D., Paige, S. & Alber, J. (2015). eHealth literacy and Web 2.0 health information seeking behaviours among baby boomers and older adults. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(3). e70. Retrieved from https://www.jmir.org/2015/3/e70/

- Tsai, T-I. (2012). Coursework-related information horizons of first-generation college students. Information Research, 17(4), paper 542. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/17-4/paper542.html. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/747up6PDW)

- Vinson, T. (2009). Social inclusion: the origins, meaning, definitions and economic implications of the concept of inclusion/exclusion. Canberra: Australian Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

- Wångdahl, J., Lytsy, P., Mårtensson, L. & Westerling, R. (2014). Health literacy among refugees in Sweden – a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 1030.

- White, M. (2016). Ghana population, consumption and environment (PCE) survey, 2002. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. Retrieved from https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/34830/version/1 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/747wwW6Nx)

- Zimmerman, M.S. (2017). Assessing the reproductive health information-seeking behaviour of low-income women: describing a two-step information-seeking process. Journal of Health Communication, 23(1), 1-8.

How to cite this paper

Appendix A: Examples of information horizon maps

Appendix B: Health information survey questionnaire

We invite you to participate in a research study being conducted by investigators from The University of Iowa. The purpose of the study is to explore the health information-seeking patterns and needs of immigrant and refugee women residing in the United States.

If you agree to participate, we would like you to fill out a survey. The survey will be administered on paper. You are free to skip any questions that you prefer not to answer. It will take approximately 20 minutes.

For filling out the survey to completion, with the exception of any questions that you are not comfortable answering, you will be given $10 in cash immediately.

This survey is completely anonymous. We will not collect your name or any identifying information about you. It will not be possible to link you to your responses on the survey.

Taking part in this research study is completely voluntary. If you do not wish to participate in this study, simply say no or return the survey without answering any of the questions.

If you have questions about the rights of research subjects, please contact the Human Subjects Office, 105 Hardin Library for the Health Sciences, 600 Newton Rd, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242- 1098, (319) 335-6564, or e-mail irb@uiowa.edu.

Thank you very much for your consideration of this research study.

Sources and trust

1. In general, would you say your health is: 1=Very poor 2= poor 3= good 4=very good

2. Do you think you have a high risk to become unhealthy in the future? ___Yes, ___No

a. If yes, why? ____________________________________________________ Think about a recent time (the last time) that you had questions about health:

3. Was the information for yourself or someone else? _________________________

a. If for someone else, what person? ________________________

4. What type of information where you looking for? (Examples: Information about illness, children, nutrition, birth control, etc.)

_______________________________________________________________________

5. Did you find it? ___Yes, ___No

6. Where did you look for information when you had questions about your health? For

example, did you talk to a doctor or friend, look on the internet or in books or magazines?

_______________________________________________________________________

a. After the first place you looked for information, did you go to a second source? If so, what was next?

__________________________________________________

7. Did you find enough information? ___Yes, ___No

8. Was the information you found easy to understand? ___Yes, ___No

9. Did you trust the information you found? ___Yes, ___No

10. After you got the information you wanted, did you do any of the following:

a. Changed a behavior to be healthier ___Yes, ___No

b. Sought treatment ___Yes, ___No

c. Discussed the information with a doctor ___Yes, ___No

d. Shared information with a family member or friend ___Yes, ___No

e. Looked for more information ___Yes, ___No

f. Tried to avoid more information about the topic ___Yes, ___No

11. Of sources of information about health, (examples are your doctor, the internet, magazines, television) which ones do you trust the most?

________________________________________________________________________

12. Of sources of information about health, which ones do you trust the least?

________________________________________________________________________

13. Do you ever come across information about health without looking for it? ___Yes __No

b. If yes, where? ________________________________________

14. If you need information about health again, where would you like it to be so that you can get it?

_______________________________________________________________

15. How often do you look for answers to health questions?

___Daily, ___Weekly, ___Monthly, ___Several times a year, ___Rarely, ___Never

Barriers

1. Did you have any problems when trying to obtain health information? ___Yes __No

a. If yes, what problems? ______________________

2. When you need information about health, do you feel like you can always get it? ___Yes ___No

3. Is there something that would help you get better information?

________________________________________________________________________

Information needs

1. Do you need health information about any of the following topics?

General health and wellness ___Yes __No Diet and nutrition ___Yes __No

Mental health ___Yes __No

Dental health ___Yes __No

Managing a chronic illness/health problem ___Yes __No

Finding health care for you in the United States ___Yes __No

Finding health care for your children in the United States ___Yes __No

Paying for health care in the United States ___Yes __No

Preventing pregnancy ___Yes __No

Preventing an STD or HIV ___Yes __No

Protection from domestic violence ___Yes __No

How to be healthy during pregnancy ___Yes __No

How to have a healthy child ___Yes __No

Parenting ___Yes __No

Demographics

1. What is your age? _____

2. What is your marital status? ____ Never married ____ Married ____ Divorced ____Widowed

3. How many children do you have? _____

4. How many years of school have you completed? _____

5. How long have you lived in the US? ______________

6. Do you enter the US under refugee status? ____ Yes ____ No

7. What country were you born in? _______________________

8. In which languages do you know how to read or write? ________________________

9. Do you have books in your home? ____ Yes ____ No

10. Do you have any way to use the internet? ____ Yes ____

a. If yes, how? __________________

11. How often do you use the internet? _________________

12. What do you look up? _____________________________________________________

This is the last question. Can you please draw me a picture of what information places and people are available to you? What I mean is, if you need information about health, can you draw a picture of where you would go and in what order? For example, can you draw from leaving your house to find information? Would you first walk to a friend’s house or to the library? Where would you go? Please draw as many places to look for information as you can.