The emerging role of business intelligence culture

Rimvydas Skyrius, Svetlana Nemitko and Gytis Talocka .

Introduction. The mixed experience of business intelligence implementation is shifting the focus of researchers and practitioners from technology issues to human factors. The wide set of human factors influencing business intelligence adoption tends to define features of what may be called business intelligence culture, a concept covering human and managerial issues that emerge in business intelligence implementation. The goal of this paper is to point out the key features of business intelligence culture, and examine their relations to the perceived level of this culture.

Method. A test survey has been performed in a group of actual users of business intelligence systems to define specific groups of human factors that may be considered the elements of business intelligence culture.

Analysis. Relations between key features of business intelligence culture and perceived level of this culture have been evaluated using IBM SPSS Modeler data mining software.

Results. Key features of business intelligence culture have been defined, and a relation of some of these features, mostly information sharing, to the perceived level of business intelligence culture has been evaluated.

Conclusions. The research has shown that the key features of business intelligence culture are: sharing of information and insights, creation of an intelligence community, information integration, accumulation of experience and of lessons learned."

Introduction

Business intelligence has firmly taken the position of an activity that supports advanced business informing, taking over from decision support systems who in their own turn were expected to provide advanced informing where regular information systems fell short. Although the definition and boundaries of business intelligence is and most likely will be the subject of discussion for the foreseeable future (Bucher and Gericke, 2009 ; Popovič, Turk and Jaklič, 2010 ; Power, 2013 ), for the purposes of this paper we will assume that business intelligence may be defined as the organizational practice that includes a coherent set of people, informing processes and conventions using a comprehensive technology platform to satisfy business information needs that range from medium to high complexity.

Business intelligence platforms are a fairly advanced area in terms of technology, and actually may be considered a test-bed for any innovations in advanced business informing. Technology advances create substantial value expectations from the users (Loshin, 2013; Yeoh and Popovic, 2015 ). On the other hand, numerous cases abound on problems in implementing business intelligence and creating expected business value, and a contradiction between advanced technologies and stumbling business intelligence implementation comes up. Various reasons for these problems have been pointed out in many sources. Value expectations are higher when investing in a sophisticated information system like business intelligence system; however, extraction of this value requires smarter activities that such systems enable, and such activities require specific organizational environment that gives considerable attention to human factors and cultural issues.

A significant part of research in the area of business intelligence implementation concentrates on the technology issues. However, for the last few years of business intelligence coverage in academic and professional sources many researchers have stated that among the reasons for business intelligence problems or failures, technological factors are far outweighed by human factors (e.g., Moss and Atre, 2003; Stangarone, 2014). Marchand, Kettinger and Roliins (2001) have stressed the importance of human factors like information behaviour and values. Presthus (2014) has defined business intelligence systems as socio-technical systems with equal importance given to technical and human factors, and presented a set of business intelligence adaptation cues based on human factors. Yoon, Ghosh and Jeong (2014) have stressed social influence and learning climate as important human factors in adopting business intelligence. Villamarin Garcia and Diaz Pinzon (2017) have extracted a list of business intelligence success criteria from the literature, where there are very few technology-related criteria. Yeoh and Coronios (2010), and later Yeoh and Popovic (2015) have defined critical success factors for business intelligence implementation, where organizational and managerial dimensions prevail. Olszak (2016) has explored factors leading to business benefits from business intelligence; again, mostly managerial factors dominate.

The wide and varied set of human factors, although important, is rather fragmented and lacks a unifying concept. An emerging trend is the development of specific business intelligence culture as a unifying environment for human drivers and a key prerequisite for successful adoption. The issues of business intelligence culture are still lacking structure and clarity; however, several groups of culture features are starting to emerge. This has led to the attempts to gain insights into key issues related to business intelligence culture by examining the information activities in organizations that already have adopted business intelligence and have considerable experience in its use. This paper presents a part of ongoing research into multiple dimensions of human factors of business intelligence implementation, and concentrates on user ratings of business intelligence culture in their organizations. The most important part of research is the choice of perceived level of business intelligence culture, as seen by the respondents, for the role of a reference point in an attempt to estimate important factors relating to this perceived level. The performed empirical research relates these levels to factors like distribution and sharing of information and insights.

The structure of the paper is as follows: first, the concept of business intelligence culture is discussed, and the next paragraphs relate business intelligence culture to organizational and information culture. This is followed by the description of the most common features of business intelligence culture, derived from the sources of published research. After that, the results of the actual performed research on some features of such culture are presented, and the paper is summed up in the conclusions.

Relation of organizational, information and business intelligence cultures

The wide set of human factors explored in published research, and the significance of organization-wide sharing of insights in particular, has hinted an existence of unifying cultural environment to join human factors of business intelligence. The terms like information culture, business intelligence culture, intelligence culture, analytic culture, decision-making culture, data-driven culture are already in use by researchers (e.g., Marchand, Kettinger and Rollins, 2001; Viviers, Saayman and Muller 2005; Wells 2008; Kiron and Shockley 2011; Popovič, Hackney, Coelho and Jaklič, 2012; Marchand and Peppard, 2013). To avoid confusion between various terms aimed at cultural issues in an organization, we have to clarify the relation of organizational culture to its recent information technology-related incarnations.

- Organizational culture covers the following dimensions: values, norms, behaviour, habits; information and informing processes are an important part of organizational culture, as stated by numerous sources (Lee and Widener 2013; Herschel and Jones 2005; Hough 2011);

- Information culture, according to Höglund, (1998) and Choo (2013), constitutes part of the organizational culture and has its own set of dimensions; covers all informing processes in an organization from the most detailed data units and actions performed on them to the complex information needs and complicated procedures to meet them. Or, according to Choo (2013), information culture is a part of organizational culture that is concerned with the assumptions, values, and norms that people have about creating, sharing, using information;

- Business intelligence culture may sound a bit controversial in a sense that it is a relatively new term, and the understanding of it varies from source to source. However, its positioning is clearly on the complex part of information needs scale intended to satisfy the needs for insights and decision support that arise from important and possibly costly issues.

Arguing about business culture, Wells (2008) defines its key areas: relationships, effectiveness, alignment, accountability, responsibility, commitment, change, values. Wells also states that there is no single right culture; and lists terms that are encountered in papers dealing with business intelligence culture, e.g., analytic culture, culture of discovery, culture of measurement, learning culture, decision-making culture etc. Watkins (2013) provides definitions of organizational culture that expose several traits featured in discussions on business intelligence culture: incentives, shared understandings and sense-making, values and rituals, norms and definitions of right and wrong, defensive system that senses risks and should be able to change with the environment. Lee and Widener (2013, p. 13) define organizational culture as the shared value and norms of the collective organization. O’Reilly and Chatman (1996) discuss what they call strong culture organizations, and among their features point out inclusive systems of participation that promote commitment, and consistent information from recognized leaders signalling what is important.

Choo (2013) relates organizational culture to information culture and presents two dimensions of the latter: information values and norms, and information behaviour. Alongside these dimensions, four types of information culture are specified: risk-taking, relationship-based, rule-following, and result-oriented, and, roughly conforming to four organizational culture types proposed by Cameron and Quinn (2011): adhocracy, clan, hierarchy, and market. As business intelligence strives to provide complete view of the environment, where all information sources and processing functions have their important role, the presence of intelligence activities exists in all types of information culture proposed by Choo (Table 1):

| Type of information culture | Features | Dominating business intelligence functions |

|---|---|---|

| Risk-taking | Sharing and proactive use of information are emphasized, promoting innovation and insights; focus on external information | Market intelligence and competitive intelligence, often ad-hoc |

| Relationship-based | Focus on internal information, promoting collaboration and cooperation; again, sharing and proactive use of information are emphasized | Communication, information integration, positioning and strengthening of organization-wide business intelligence function |

| Rule-following | Efficiency, control and integrity are the key features; focus on internal information | Monitoring of internal status on permanent basis |

| Result-oriented | Emphasizes evaluation of performance of organization as a unit, focusing mostly on external information and using benchmarking, surveys, market research | Market intelligence and competitive intelligence, largely by defined procedures |

Summing up, organizational culture can be seen as a set of norms and beliefs that are valid within the bounds of an organization, significantly related to informing in terms of information access, distribution and decision making. The important role of information creates an overlap between organizational and information culture; similarly, business intelligence culture may be considered a part of information culture, although carrying its own specific features. The specific nature of cultural issues arising in business intelligence may be supported by the fact that neither organizational nor information culture deal with issues like intelligence community and intelligence information sharing as their key features. Also, these issues are hardly mentioned when discussing implementation of regular systems of the enterprise resource planning type.

Not all types of organizational culture are equally supportive of business intelligence. Herschel and Jones (2005) have concentrated on the factors limiting information and insight sharing, and state that insight sharing is not supported in cultures where people are rewarded for what they know and others do not. Brijs (2013) has stated that the machine bureaucracy is incompatible with sophisticated business intelligence and knowledge exchange for strategy development. Mettler and Winter (2016) have researched determinants of information sharing in organizations by using social network platforms to exchange any information. They tested assumptions about relationships between information sharing in enterprise social systems and such determinants as organizational information ownership norms (not significant), reciprocity and social cohesion (significant), quality of shared information (significant), and privacy concerns (significant). Further analysis of relations between organizational culture and business intelligence, however interesting, oversteps the boundaries of this research, and is not pursued further in this paper.

The most common features of business intelligence culture

Although the published research sources on business intelligence culture are not very numerous, their analysis has produced a set of the most common features of business intelligence culture, named below.

The importance of information sharing

While for a lone analyst the importance of the skills to cope with intelligence tasks is obvious, many sources have stressed that communication between participants in the business intelligence process should create value by motivating tool adoption and use or insight development. It has to be noted that in literature terms “information sharing” and “insight sharing” are used interchangeably. To clarify this issue, further in this paper we will consider insights as a specific type of information, loaded with aggregated and valuable sense, and use a single term “information sharing” to denote both sharing of information and insights. Carlo, Lyytinen and Boland (2012) defined the existence of collective mindfulness as a set of combined activities that create awareness and facilitate discovery in high risk environments. Davies (2004), arguing about intelligence culture, has stressed the importance of communication and sharing of information:

‘The need for collegiality … is driven by specific conditions. Those conditions include technically and technologically diverse intelligence sources, the interdependence of those sources as pieces of a larger picture, and the need to meld those pieces together to get a coherent picture on the basis of which decision-makers can make their decisions’.(Davies, 2004, p. 497)

The opening of information silos inside the organization and horizontal cross-function exchange of information is one of the most prominent features of business intelligence culture found in published research. Marchand and Peppard (2013) suggest to assemble cross-functional analytical teams, open data silos, and facilitate a culture of information sharing. Kiron and Shockley (2011), describing elements of data-oriented culture, have stressed the sharing of information as one of the key characteristics of this culture. Matzler, Strobland and Bailom (2016) use the term collective intelligence and point to the importance of creating cognitive diversity with more contacts outside the usual circles, and the ability to access decentralized knowledge. Presthus (2014) describes actual experience from implementation of a business intelligence system, and has pointed out that the information technology platform will stimulate use if being simple, shared and open.

Record of lessons and experience as a sharing platform

As suggested by the importance of sharing of information in the previous paragraph, the horizontal nature of the business intelligence function is also supported by collections of accumulated and shared previous experience and lessons. These collections include not only success stories, but errors, failures, mistakes and surprises, thus reinforcing trust among the members of business intelligence community (Marchand et al., 2001). Grublješič and Jaklič (2015) indicate availability of prior experience as one of the business intelligence acceptance factors. Discussing expertise management in an organization, Shah (2011) stresses the need to use social systems that aggregate available experience and develop competitive advantage through driving collective talent. Hough (2011), discussing ways for business intelligence function to support organizational strategy, suggests identifying, sharing and evangelizing best practice; and sharing and discussing assumptions and strategies with everyone involved. Kiron and Shockley (2011) point out that the build-up of analytics expertise and lessons learned is an important link in the information integration chain. We may note that useful fragments about earlier experience do exist in one form or another, and not all of them are captured or deserve being recorded, but there is a considerable risk that valuable experience will be lost. A system of record with several basic standards and simple capture and search and retrieval functions can be one of the possible approaches to perform the function.

Intelligence information integration

The need to integrate information for insight development is key to intelligence activities, and is evident from the available history of intelligence activities (Davies 2004). The aggregation of individual pieces of information and detection of common traits may create valuable insights, or a more valuable intelligence product. Matzler et al. (2016), researching a case of competitive analytics, found out that the actual use of a competitive intelligence integration platform, called competitor Wiki, supported smooth information integration and effectively improved insight quality. However, company-wide business intelligence systems with an intent to integrate information should be implemented carefully: many published cases on (e.g., Fogli, Guida, 2013; Işık, Jones and Sidorova, 2013; Popovič et al., 2012; Zimmer, Baars and Kemper, 2012) stress the necessity to achieve a balanced mix of centrally managed standards on one side, and flexibility for special needs of business users on another. On the other hand, the above named sources actually deal with data integration, where standards relate more to information technology management than information integration, whose goal is to integrate sense and produce composite insights. Taking further the idea of information integration, Terziyan and Kaykova (2011) introduce Executable Reality as an advanced concept that defines how decision-makers can utilize highly heterogeneous data and business intelligence on top of it. A core feature of aforementioned executable reality is that by integrating sense into composite insights it enhances perception of real-world objects. Grandy and Mills (2004), however, identify that organizations are prone to introducing third-order simulacra, i.e. the representation of reality that an organization maintains is self-contained, comfortable and no longer represents existing objects. They stress that obscure concepts may serve managers as manipulative tools to control others. However, we may expect that a cooperative and catalytic business intelligence environment might utilize the filtering potential that information sharing is expected to have on information integration, and have a positive effect on objective reflection of reality that business intelligence provides.

Creation of an intelligence community

Many researchers agree that people actively engaged in business intelligence activities tend to gravitate towards forming a business intelligence community. Hallikainen, Merisalo-Rantanen, Syvaniemi and Marjanovic (2012) indicate that to propagate business intelligence thinking, a shadow community, where mental models and outcomes are shared, is of paramount importance. According to Mettler and Winter (2016), regular interaction on a sharing platform strengthens social ties and may lead to social cohesion, while peer pressure and increased visibility motivates individuals to maintain high quality of shared information. Alavi, Kayworth, and Leidner (2006) point out that the bonding glue for communities is shared professional interest and commitment, and informal communities are more agile and resistant to change than formal ones. Presthus (2014) has stressed the importance of self-reinforcing installed base: when users contribute, the user base and the value of system increases. An interesting point raised by Yoon et al. (2014) suggests that perceived social influence from referent others like co-workers or supervisors, or a learning climate, have a significant positive influence on individual intent to adopt business intelligence applications. Marchand and Peppard (2013) recommend finding sources of positive cycle to help reinforce the business intelligence community, and provide a case study of business intelligence community growth with positive feedback. Marchand et al. (2001) present a case where people have competed with each other in skills of using a business intelligence system and speed to locate the necessary information.

An important feature for business intelligence community, mentioned in published research, is tolerance for experimentation and mistakes. Marchand and Peppard (2013) stress that building a collaborative culture requires being tolerant for experimenting, learning and errors, and intolerance for failures and errors work against this culture.

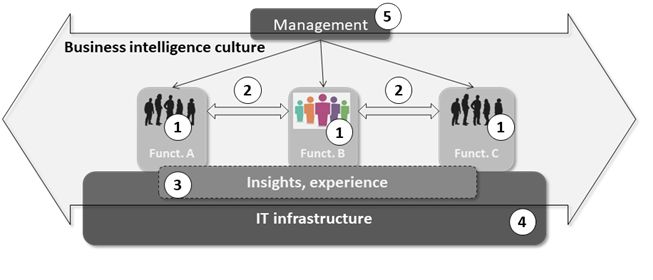

Summarizing the results of the literature analysis, the environment of business intelligence culture might include the participants and processes shown in Figure 1.

In Figure 1, the numbers refer to the corresponding business intelligence culture components listed below:

- The horizontal intelligence community, comprising analysts and insight builders from key functional areas.

- Sharing of intelligence information; synergy in a community leading to integration of sense-making and skills.

- Structured collections of insights, experience and lessons learned; with growing contribution, community size and the value of the system increases.

- Balanced information technology management, blending centralized elements implying few essential common standards with distributed local and self-service environments that carry the required agility and flexibility.

- The role of management, although not explicitly pointed out, is to create and maintain a blend of the above components to ensure development of business information culture and business intelligence culture as its subset.

One of the dominant likely components of business intelligence culture is sharing, exchange and access to information that crosses departmental borders and neutralizes the ill effects caused by information silos and fiefdoms.

Research on business intelligence adoption in Lithuanian companies

The analysis of published sources on cultural issues around business intelligence has directed the authors of this paper to perform empirical research in Lithuanian businesses – active users of business intelligence systems to estimate the role of human factors and business intelligence culture in the findings. Business intelligence culture is a relatively new research area, hence to discover important emerging issues it has been decided to employ elements of both quantitative and qualitative methods. The use of qualitative methods containing inductive approach and discovery techniques by eliciting free-text responses are deemed suitable for discovery of emerging important issues. Although not used extensively in this research, the qualitative elements are expected to facilitate the understanding of individual perceptions (Hunter, 2004). The structured part of the survey uses quantitative methods for evaluation of awareness of business intelligence cultural issues among respondents. Because of the unfamiliarity of the researched area, the quantitative analysis has mostly used descriptive methods, together with initial statistical testing of factor significance.

To gain more insight into actual state of information sharing in business intelligence applications, a questionnaire method has been chosen to cover a number of comparable items across different businesses. The questionnaire has touched many aspects of business intelligence implementation and use, including issues related to information sharing, and for this part of the questionnaire the research question may be formulated as follows: How do the respondents relate their perceived levels of business intelligence culture in their organizations to information sharing?

The research of business intelligence adoption issues in Lithuania was conducted in September-October of 2016. The research target group may be considered a convenience sample as it included Lithuanian companies and organizations with revenue of more than five million Euro a year that had acknowledged successful recent implementation of business intelligence. The survey has been conducted online and questioned 207 respondents composed of first and second-level managers responsible for different business areas. 43% of respondents belong to large (in terms of business scale in Lithuania) organizations with more than twenty million Euro annual revenue; 48% of respondents represented companies with more than 250 employees, and in several cases responses were provided by more than one manager from a company. For the purposes of this paper, the actual use of business intelligence, business analytics tools and techniques comes under a single business intelligence term, unifying the monitoring and analytic parts of related activities.

The questionnaire included several groups of questions:

- respondent demographics: profiles of companies, respondents and business intelligence technologies in use;

- expectations from business intelligence use against actual results: value created by use, solved and unsolved problems, factors influencing implementation and use;

- actual experiences in using business intelligence: actual latency of information presentation and its movement in a process chain; access to and sharing of assorted information for decision support; understanding and evaluation of business intelligence culture.

The size distribution of the surveyed companies in terms of number of employees is provided below:

| Up to 50 employees | 32 |

| Between 50 and 250 employees | 76 |

| More than 250 employees | 99 |

The distribution of the surveyed companies by industry is:

| Manufacturing | 59 |

| Commerce | 57 |

| Services | 30 |

| Public sector | 21 |

| Telecommunications / IT | 16 |

| Finance / insurance | 10 |

| Other | 14 |

Use of business intelligence tools

All the respondents have already implemented and are actively using different business intelligence software platforms and tools, counting one installation per one organization.

| No | Software platform | Units | Share, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unique software developed for a specific company | 49 | 24 |

| 2 | Microsoft Excel | 38 | 18 |

| 3 | Two or more different business intelligence systems (Business Objects (www.businessobjects.com), IBM Cognos (www.ibm.com), Oracle (www.oracle.com), Qlik (www.qlik.com) etc.) | 34 | 16 |

| 4 | MS Excel and proprietary software developed for a specific company | 19 | 9 |

| 5 | Qlik | 17 | 8 |

| 6 | Business Objects | 15 | 7 |

| 7 | Excel and business intelligence system (Business Objects, Cognos, Oracle, Qlik etc.) | 12 | 6 |

| 8 | Oracle | 9 | 4 |

| 9 | Power BI | 4 | 2 |

| 10 | Cognos | 3 | 1 |

| 11 | Web Focus) | 3 | 1 |

| 12 | SAS | 2 | 1 |

| 13 | IBM SPSS | 2 | 1 |

| 207 | 100 |

The results of the research confirmed once again that Microsoft Excel is the dominating business intelligence tool, with 51% of respondents (lines 1, 2 and 4) using Excel or proprietary software developed for a specific company, usually based on Excel as the only business intelligence tool companywide. On one hand, easily available business intelligence tools, e.g., systems based on Excel, prevail. On the other hand, there is a significant level of adoption of advanced business intelligence technologies in the surveyed sample – 49 % of respondents (all other cases) are using specialised systems.

Factors hindering business intelligence implementation

Articulating the factors that hinder business intelligence implementation, the respondents mostly pointed out:

- the lack of strategy (29%);

- the lack of business intelligence ambassador; not a project manager, but an internal person, who has authority and power, believes in business intelligence and spreads the mission to the whole company (28%);

- internal disagreements, dilemma of the owner (27%);

- internal disagreements, dilemma of the owner (27%);

Sharing of information

The research has shown that 60% of surveyed organizations using business intelligence successfully solved the issue of the lack of up-to-date information, and the use of business intelligence allowed 52% of surveyed companies to create an integral system ensuring a “single truth” version of analytical information. A rather high figure, 93% of surveyed organizations indicated they are sharing the information. Depending on the needs, the employees share their information communicating with each other permanently and initiating this process (51%) by themselves or sharing the information during joint meetings (42%).

The use of a business intelligence platform’s functionality, for example, to collect data from a large number of different internal data sources (the zoo of information systems) to one integral system created significant value in 61% of companies. Besides technical features, it is important to note that in many cases business intelligence has become the main axis of all the organizational processes. It naturally forces the organization to combine all of its activities, monitor and integrate the data of different business areas in a wide overall context. Business intelligence culture actually can be the starting point for a companies’ evolution from functional to process-based, supporting a more effective model of doing business in highly competitive environment.

58% of respondents stated that high business value was created by business intelligence systems enabling the sharing of created reports as well as the opportunity to prepare the insights centrally and to present them in advance. At the same time, the developers of business intelligence state that the collaboration functionality of specialized systems, providing automatic or automated sharing of prepared reports, is still not widely used. When these results were processed in the context of the answers to other questions, it became clear that this is more about sharing information by all possible channels, not exclusively using collaboration features of business intelligence system.

Another issue related to potential value of sharing information has been shown by 48% of managers stating that they have to see the context in order to perform own analysis, requiring the information from other departments or processes. However, one-third of the managers use the context only when something is going wrong in their department, and thus the problems are solved post-factum, or just recognized and considered being lessons for the future. Only 35% of the respondents were able to access the needed information by themselves; the other 65% had to ask for it from other sources - another department or analysts.

The respondents have been asked to indicate their perceived level of business intelligence culture in their organizations on a five-point Likert scale, value 1 being the lowest rating, and 5 the highest. The most important issue for data analysis below is the features of business intelligence system for the levels of perceived culture equal 3 and more, i.e. average or above. In the following analysis, the indicated level of culture has been related to several questions related to information sharing, and the empiric data have been processed using IBM SPSS Modeler ® 17.1 (https://www.ibm.com/analytics/spss-statistics-software) data mining software package to indicate the most frequent relations. The relevant questions are coded as follows:

- Q11 – How business intelligence reports are prepared?

- self-service on one’s own;

- reports are renewed automatically;

- by analysts or IT people on request;

- other.

- Q12 – In what cases analysis requires information from other processes or departments?

- in all cases;

- only when a problem occurs;

- does not require;

- do not know.

- Q13 – How do you get the decision information from other departments?

- on my own, having access rights;

- by making a request to other department;

- by approaching a person responsible for business intelligence (a business intelligence ambassador);

- this process is unregulated and chaotic;

- there is no such need.

- Q15 – How do people share analytical insights inside organization?

- do not share;

- only during common meetings;

- on permanent basis by direct communication and self-initiated discussions;

- do not know;

- other.

The role of the dependent variable has been assigned to the perceived level of business intelligence culture inside an organization, indicated in responses to question 23 (Q23) and varying from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent).

The distribution of responses to Q23 is given in Table 3 below. We have to note that the absolute majority of respondents (186 out of 207, or 89.9%) consider their organizations having their level of intelligence culture at 3 (mediocre), 4 (good) or 5 (excellent).

| Perceived level of business intelligence culture | Number of cases |

|---|---|

| 1 | 3 |

| 2 | 18 |

| 3 | 86 |

| 4 | 79 |

| 5 | 21 |

The respondents were asked to provide a free text comment explaining their rating. For the lowest perceived level of business intelligence culture, equal to 1, just three instances are available with no text comments except one: “Information is being hidden”. For other levels, the text comments provide some insights on the respondents’ rating of their business intelligence culture. For an indicated weak business intelligence culture level (rated 2), the example comments are:

Fragmented and does not encompass all aspects of activities.

The system is) still in the launch phase, inexperienced users; hope that culture will evolve.

No self-service analytics, just prefabricated templates are used.

Lack of strategy and professional analysts.

The management does not see business intelligence as an important function.

Different organization units see things differently.

It can be noted that for the level 2 of business intelligence culture dominating response topics are: business intelligence is in its initial stages of implementation, and the importance of business intelligence and its use are quite low; business intelligence is fragmented and chaotic, there’s no unified understanding for different units, and many obstacles and limitations lead to low usage.

For indicated mediocre business intelligence culture level (rated 3), the example comments are:

The required level of implementation, management and use is not achieved yet.

Although the organization is a rather advanced user of business intelligence, processes are still upgraded because there’s still space to grow.

We have all the contemporary tools we need; it’s more the lack of culture and methodology.

The emergence of business intelligence culture is rather recent, and not everybody in the organization equally understands its importance.

Lack of clear intelligence strategy. What are the goals and what are we trying to achieve?

We have to master internal communication. There’s also lack of competence in some areas.

Dominating response topics point out that business intelligence still inadequate; there’s space for growth. On the other hand, respondents are aware of the growth of business intelligence importance and related culture changes. Different people have different competences and attitudes, and there’s noticeable lack of competence and support.

For indicated good business intelligence culture level (rated 4), the example comments are:

There’s an attitude that business intelligence is a must, and competence gaps are insignificant.

The constantly changing environment forces adapting to changes. … follows one of the quality management principles – admit mistakes.

The analysis is directed to the needs of direct users, not top management. Human factors define processes and motivation.”

Recognition by top management.”

Data is available, but not convenient – part of information is not integrated, automation is insufficient and requires additional work and time.”

There’s space to grow. We are strong in intelligence, but it can be done better.

At this level of perceived business intelligence culture (4), dominating response topics point out that there is a perception of significant business intelligence role, growing understanding of business intelligence importance, and growing user base. Business intelligence culture seems quite adequate and draws realistic evaluations – nothing is perfect, but the organization steadily moves to commonplace business intelligence. The respondents are also aware of business intelligence value, its strengths and weaknesses, and directions for improvement.

For indicated excellent business intelligence culture level (rated 5), the example comments are:

Because one can note a serious attitude and processes, understanding, investment into upgrades, inclusion of new related products and additional departments.

There are all conditions for working and perfecting, submitting proposals, use required innovations.

Business data for analytics are accessible to every specialist inside competence boundaries. Inside the same boundaries, and based on this data, decision rights are granted.

Work is hardly imaginable without (business intelligence) tools – decision making would be complicated; employees use them without additional orders.

Business intelligence is already in use for some time, there are qualified people and everything works.

At this level of perceived business intelligence culture (5), dominating response topics point out that business intelligence function is clear and well-positioned, and business intelligence activity is naturally woven into work processes. There is significant experience and traditions.

The most mature answers relate to 4 level of perceived business intelligence culture; evidently, the respondents have a realistic estimation of business intelligence culture in their organizations. Meanwhile, the responses with level 5 sound a bit too optimistic. Most of the respondents have an adequate understanding of business intelligence culture and do not hesitate to relate its perceived level to business intelligence implementation success.

The survey responses to questions serving as independent variables have not been coded using Likert scale, so Cronbach‘s alpha value to estimate internal consistency has not been calculated. A simple correlation analysis has been performed on the part of the questionnaire containing data used in this paper. Interestingly, while unstructured responses show awareness and general understanding of the selected factors influencing business intelligence culture, a correlation analysis has shown the relation between the named factors as statistically insignificant (Table 6).

| Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Q15 | Q23 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q11 | 1 | ||||

| Q12 | 0,219698 | 1 | |||

| Q13 | 0,389995 | 0,469376 | 1 | ||

| Q15 | 0,175484 | 0,041152 | 0,15902 | 1 | |

| Q23 | 0,183915 | 0,214552 | 0,174078 | 0,100485 | 1 |

However, to have a better estimate of what exact levels of relation between survey data are, several additional analyses have been performed with the above factors.

To gain more insight into relation between questions in information sharing and perceived level of business intelligence culture, a neural network analysis has been performed on corresponding data using IBM SPSS Modeler ® 17.1 (https://www.ibm.com/analytics/spss-statistics-software) data mining software package. The analysis procedure, including questions Q11, Q12, Q13 and Q15 as predictor variables for Q23, had generated a network with single hidden layer containing a single node. The results of analysis are presented in Table 7.

The results indicate that both for training and testing stages of neural network analysis the strongest prediction levels lie in the area of Q23 values of 3 (mediocre) and 4 (good). This can be explained by the domination of these values in survey responses. The overall prediction strength is lower – 51.0% for training stage, and 42.6% for testing stage; this setback can be explained by lower frequencies of other instances for Q23.

| Sample | Observed | Predicted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Percent correct | ||

| Training | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 22 | 0 | 63.3% | |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 36 | 0 | 64.3% | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Overall percent | 0.0% | 0.0% | 52.4% | 47.6% | 0.0% | 51.0% | |

| Testing | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 10 | 0 | 60.0% | |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 11 | 0 | 47.8% | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Overall percent | 0.0% | 0.0% | 59.0% | 41.0% | 0.0% | 42.6% | |

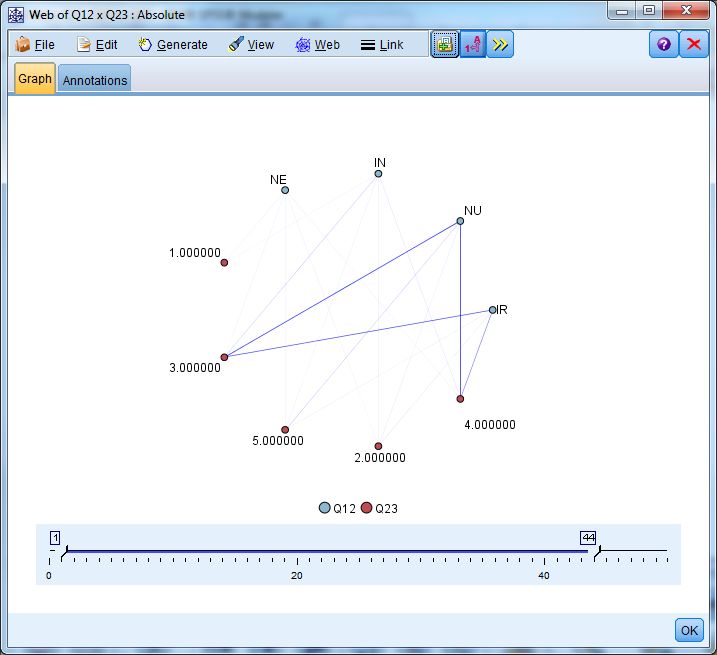

Below we present the more detailed analysis of responses to questions Q12 and Q15.

Q12. Information needs outside own department or function

The responses to Q12, asking in what cases analysis requires information from other processes or departments, have been coded as follows: NE – unaware; IN – information from other places is not required; NU – information is required on a permanent basis; IR - information is required only if there is a specific need to determine the cause of a problem, e.g., why some process is stuck.

The most frequent relations in this pair are shown in Table 8:

| Q12 – in what cases analysis requires information from other processes or departments | Q23 | Number of occurrences |

|---|---|---|

| NU (information is required on a permanent basis) | 4 | 43 |

| NU (information is required on a permanent basis) | 3 | 38 |

| IR (required only if there is a specific need) | 3 | 33 |

| IR (required only if there is a specific need) | 4 | 26 |

The data show that both for levels of perceived business intelligence culture 3 and 4 in question Q23, the dominating case of answers to question Q12 is “Information is required on a permanent basis”, and points to a perceived need of shared information, reflecting the permanent nature of intelligence and analytical functions.

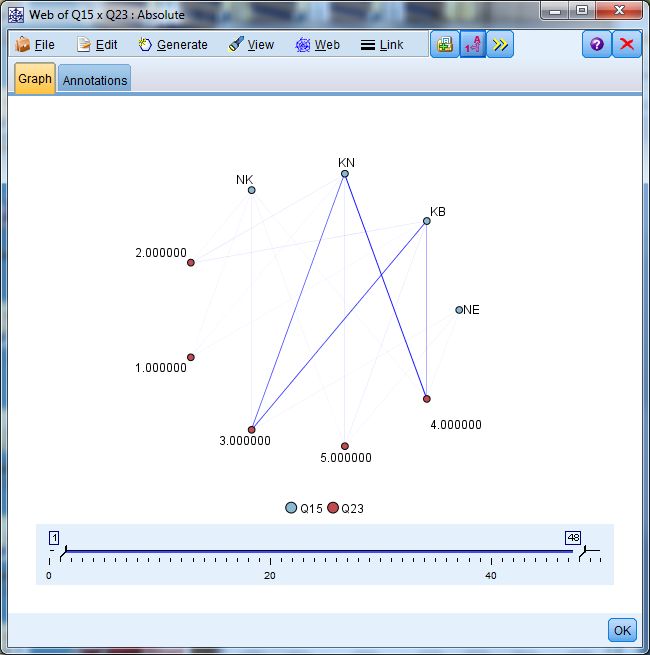

Q15. Sharing of analytical information inside an organization

The responses to Q15, asking how analytical information is shared inside organization, have been coded as follows: NK – no exchange of information; KN – permanent exchange by direct communication; KB – information is exchanged only during common meetings; NE – unaware.

The most frequent relations in this pair are in Table 9:

| Q15 | Q23 | Number of occurrences |

|---|---|---|

| KN – permanent exchange by direct communication | 4 | 47 |

| KB – information is exchanged only during common meetings | 3 | 40 |

| KN – permanent exchange by direct communication | 3 | 36 |

| KB – information is exchanged only during common meetings | 4 | 29 |

The data show that the most common occurrences involve responses permanent exchange by direct communication (KN), and “information is exchanged only during common meetings” (KB). In both cases, responses point to active and permanent sharing of information, indicating that the data silos between departments and functions have been opened or did not exist at all.

Summarizing the results, there is a noticeable relation between perceived level of business intelligence culture and intensity of information sharing between business functions, although its statistical significance is not strong. It can also be noted that, although the need for information sharing has not been very obvious in open text responses to the question Q23 about perceived level of business intelligence culture, the further analysis of data on information sharing for levels 3 (mediocre) and 4 (good) confirms its importance for above-average business intelligence culture.

Discussion and conclusions

The set of culture components, drawn from published sources, i.e., information sharing and integration, record of lessons and experience, existence of business intelligence community, has been recognized as important for the formation of business intelligence culture in the responses of business users. The attempt to relate these components to the perceived levels of business intelligence culture may be considered a novel result, unifying together scattered human factors of business intelligence success that were found in literature analysis. An important part of the findings is that the respondents have shown an understanding of the concept of business intelligence culture, of its strength or weakness, and of its role in creating benefits from using business intelligence. These findings, to our opinion, justify the distinction of business intelligence culture as a separate concept that unifies the scattered definitions of cultural issues relating to business intelligence in published research. Although no research has been performed in relating organizational culture to business intelligence culture, the responses reflect the influence of the overall organizational culture on how the business intelligence potential is utilized. This finding could be a direction for future research avenues concentrating on relations between organizational culture, information culture, and business intelligence culture.

The analysis of empirical research data has shown that in the surveyed organizations the dominating share of respondents perceived their business intelligence culture as being mediocre to excellent. As the results presented in this paper deal mostly with intelligence information sharing, it can be noted that the surveyed organizations are well aware of their analytical needs and are quite active in supporting the horizontal communication of shared information. For good and excellent levels of perceived business intelligence culture respondents have indicated permanent needs and use of information from other functional departments, and active exchange of insights by direct communication. The importance of information sharing, as pointed out in many published works dedicated to the human factors of business intelligence implementation, has been only partially confirmed by the results of empirical research. The modest statistical significance of the relationships between the variables introduces reasonable caution in producing conclusions. On the other hand, respondents who are the most satisfied with their business intelligence culture seem to exist in an environment where information sharing is a natural way of executing business intelligence, and data silos between departments and functions have been opened or did not exist at all.

Business intelligence culture may boost business intelligence adoption as well as get in the way of it, for example, create the rock the boat syndrome when inconvenient (mostly internal) information is disclosed. Apart from mobilizing human factors, business intelligence culture may serve as an axis of organization-wide information integration, and help the transition from functional to process-oriented mode. The named set of culture components, although far from being exhaustive, reflects a trend towards harmonisation of human factors and alignment of efforts by establishing a flexible set of guidelines for sustainable business intelligence developments.

Limitations of the study. Further research needs a better-developed and more rigorous research model covering the most prominent relations between features of business intelligence culture. Our future research is going to look in more detail at the factors that motivate the growth of business intelligence community, relations between intelligence needs and technology platforms, effective information management in the area of management of experience and lessons, and common issues of business intelligence agility and resilience to maintain its key competences over the future changes in business activities and their environment.

About the authors

Rimvydas Skyrius is a professor at the Faculty of economics and business administration, Vilnius university, Lithuania. His research interests are in business information needs, management information systems, management decision support and business intelligence. He is the head of the Department of Economic Informatics and can be reached at rimvydas.skyrius@evaf.vu.lt

Svetlana Nemitko is a lecturer and a PhD student with the Department of Economic Informatics, Faculty of Economics at Vilnius university, Lithuania. Her research and teaching interests include business intelligence, analysis of BI business requirements and needs, business insight and intelligence culture issues.She can be reached at svetlana@streamline.lt

Gytis Talocka is a former MA student of Management information systems at Vilnius university (at the time of writing the paper). Currently he is a front-end developer and scrum master at Visma Lithuania. He can be reached at gytis.talocka@visma.com

References

- Alavi, M., Kayworth, T. & Leidner, D. (2006). An empirical examination of the influence of organizational culture on knowledge management practices. Journal of Management Information Systems, 22 (3), 191-224.

- Bara, D. & N. Knezevic (2013). The impact of right-time business intelligence on organizational behaviour. Interdisciplinary Management Research, 9, 27–42.

- Barclay, R.O. & Kaye, S.E. (2000). Knowledge management and intelligence functions: a symbiotic relationship. In Jerry Miller, (Ed.). Millennium intelligence: understanding and conducing competitive intelligence in the digital age. (pp. 158-169). Medford, NJ: CyberAge Books.

- Brijs, B. (2013). Business analysis for business intelligence. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis.

- Bucher, T. & Gericke, A. (2009). Process-centric business intelligence. Business Process Management Journal, 15(3), 408-429.

- Cameron, K.S. & Quinn, R.E. (2011). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: based on the competing values framework. Reading, MA: Josey-Bass.

- Carlo, J.L., Lyytinen, K. & Boland R., Jr. (2012). Dialectics of collective minding: contradictory appropriations of information technology in a high-risk project. MIS Quarterly, 36(4), 1081-1108.

- Choo, C. W. (2013). Information culture and organizational effectiveness. International Journal of Information Management, 33(5), 775-779.

- Cohen, W.M. & Levinthal D.A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128-152.

- Davies, Ph. (2004). Intelligence culture and intelligence failure in Britain and the United States. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 17(3), 495-520.

- Fogli, D. & Guida, G. (2013). Knowledge-centered design of decision support systems for emergency management. Decision Support Systems, 55(1), 336-347.

- Grandy, G. & Mills, A. J. (2004). Strategy as simulacra? A radical reflexive look at the discipline and practice of strategy. Journal of Management Studies, 41(7), 1153–1170.

- Grublješič, T. & Jaklič, J. (2015) Business intelligence acceptance: the prominence of organizational factors. Information Systems Management, 32(4), 299-315.

- Hallikainen, P., Merisalo-Rantanen, H., Syvaniemi, A. & Marjanovic, O. (2012). From home-made to strategy-enabling business intelligence: the transformational journey of a retail organization. In Proceedings of the 20th European Conference on Information Systems ECIS 2012, Barcelona, Spain, June 2012, paper 28. Atlanta, GA: Association for Information Systems

- Herschel, R.T. & Jones, N.E. (2005). Knowledge management and business intelligence: the importance of integration. Journal of Knowledge Management, 9(4), 45-55.

- Höglund, L. (1998) A case study of information culture and organizational climates. Swedish Library Research, (Nos. 3-4), 73-86.

- Hough, J. (2011). Supporting strategy from the inside. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 62(5), 923-926.

- Hunter, M.G. (2004) Qualitative research in information systems: an exploration of methods. In M. Whitman and A. Woszczynski (Eds.), The handbook of information systems research. (p. 291-304). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Işık, Ö., Jones, M.C. & Sidorova, A. (2013). Business intelligence success: the roles of BI capabilities and decision environments. Information & Management, 50(1), 13-23.

- Kiron, D. & Shockley, R. (2011). Creating business value with analytics. MIT Sloan Management Review, 53(1), 57-63.

- Lee, M. & Widener, S. (2013). Culture and management control systems in today’s high-performing firms. Management Accounting Quarterly, 14(2), 11-18. Retrieved from https://www.imanet.org/-/media/8e8262e40ceb44f3bf5f429915cd6542.ashx (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/74PPz1y3l)

- Loshin, D. (2013). Business intelligence: the savvy manager’s guide. Waltham, MA: Morgan Kaufmann.

- Marchand, D. & Peppard, J. (2013). Why IT fumbles analytics. Harvard Business Review, 2013(January-February). Retrieved from: https://hbr.org/2013/01/why-it-fumbles-analytics

- Marchand, D.A., Kettinger, W.J. & Rollins, J.D. (2001). Information orientation: the link to business performance. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Matzler, K., Strobl, A. & Bailom, F. (2016). Leadership and the wisdom of crowds: how to tap into the collective intelligence of an organization. Strategy & Leadership, 44(1), 30-35.

- Mettler, T. & Winter, R. (2016). Are business users social? A design experiment exploring information sharing in enterprise social systems. Journal of Information Technology, 31(2), 101-114.

- Moss, L.T. & Atre, S. (2003). Business intelligence roadmap: the complete project lifecycle for decision support applications. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

- Negash, S. & Gray, P. (2003). Business intelligence. In: F. Burstein and C. W. Holsapple (Eds.), Handbook on decision support systems 2, (p. 175-193). Heidelberg: Springer.

- Olszak, C. (2016). Toward better understanding and use of BI in organizations. Information Systems Management, 33(2), 105-123.

- O'Reilly, C. & Chatman, J. A. (1996). Culture as social control: corporations, cults, and commitment. In: B. M. Staw and L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior: an annual series of analytical essays and critical reviews, Vol. 18, (pp. 157-200). New York, NY: Elsevier Science/JAI Press.

- Popovič, A., Hackney, R., Coelho, P.S. & Jaklič, J. (2012). Towards business intelligence systems success: effects of maturity and culture on analytical decision making. Decision Support Systems, 54(1), 729-739.

- Popovič A., Turk, T. and Jaklič, J. (2010) Conceptual model of business value of business intelligence systems. Management, 15 (1), 5-30.

- Power, D. (2013). Decision support, analytics, and business intelligence. New York, NY: Business Expert Press.

- Presthus, W. (2014). Breakfast at Tiffany’s: the study of a successful business intelligence solution as an information infrastructure. In Proceedings of the Twenty Second European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), 9-14 June 2014, Tel Aviv, Israel. Track 04, paper 9. Retrieved from: https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2014/proceedings/track04/9/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/74PRPqkbV)

- Shah, R. (2011, March 1). Shifting the imperative from knowledge management to expertise management. [Web log post]. Retrieved from: http://www.forbes.com/sites/rawnshah/2011/03/01/shifting-the-imperative-from-knowledge-management-to-expertise-management/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/74PR0rXLu).

- Skyrius, R. (2014) The split of information needs support between the users and information technology. In Gloria Phillips-Wren, Sven Carlsson (eds.). Proceedings of the DSS 2.0 – Supporting Decision Making with New Technologies: 17th conference for IFIP WG8.3 DSS, 2-5 June 2014, Paris, France, (pp. 227-238). Amsterdam: IOS Press.

- Stangarone, J. (2014, May 20). 7 reasons why BI projects fail. [Web log post]. Retrieved from: http://www.mrc-productivity.com/blog/2014/05/7-reasons-why-business-intelligence-projects-fail/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/74PRZ9rbD)

- Terziyan, V. & Kaykova, O. (2011). Towards "executable reality": BI on top of linked data. In Maribel Yasmina Santos and Vagan Terziyan, (Eds.). BUSTECH 2011. The First International Conference on Business Intelligence and Technology, September 25-30, Rome, Italy. (pp. 26-33). Wilmington, DE: International Academy, Research, and Industry Association. Retrieved from http://www.cs.jyu.fi/ai/papers/BUSTECH-2011.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/74PRqhFOt)

- Villamarin-Garcia, J.M. & Dias Pinzon, B.H. (2017). Key success factors to business intelligence solution implementation. Journal of Intelligence Studies in Business, 7(1), 48-69.

- Viviers, W., Saayman, A. & Muller, M.-L. (2005). Enhancing a competitive intelligence culture in South Africa. International Journal of Social Economics, 32(7), 576-589.

- Watkins, M. (2013). What is organizational culture? And why should we care? Harvard Business Review(May 15). Retrieved from: https://hbr.org/2013/05/what-is-organizational-culture

- Wells, D. (2008, June 3). Analytic culture – does it matter? [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.b-eye-network.com/view/7572 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/74Q9JUn0h)

- White, C. (2007). Who needs real-time business intelligence? Teradata Magazine Online, 7(3), 1-2. Retrieved from http://apps.teradata.com/tdmo/v07n03/pdf/AR5385.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/74PS48qa2)

- Yeoh, W. & Coronios, A. (2010). Critical success factors for business intelligence systems. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 50(3), 23-32.

- Yeoh, W. & Popovic, A. (2015). Extending the understanding of critical success factors for implementing business intelligence systems. Journal of the Association for Information, Science and Technology, 67(1), 134-147.

- Yoon, T.E., Ghosh, B. & Jeong, B.-K. (2014). User acceptance of business intelligence (BI) application: technology, individual difference, social influence, and situational constraints. In Proceedings of the 47th Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences, 6-9 January, 2014, Waikoloa, Hawaii, (pp. 3758-3766). Washington, DC: IEEE Computer Society.

- Zimmer, M., Baars, H. & Kemper, H.-G. (2012). The impact of agility requirements on business intelligence architectures. In Proceedings of the 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, January 4-7, 2012, Maui, HI, USA, (pp. 4189-4198). Washington, DC: IEEE Computer Society.