Network analysis approaches to collaborative information seeking in inter-professional health care teams

J. David Johnson

Introduction: It is widely believed that interprofessional health care teams can improve patient care and increase safety; however, intra-team communication has often proven to be problematic. One particularly important aspect of this problem is how teams collaborate to seek the information needed to address the issues they are confronting. Network analysis offers a rich set of concepts for tackling this problem.

Method: Review essay.

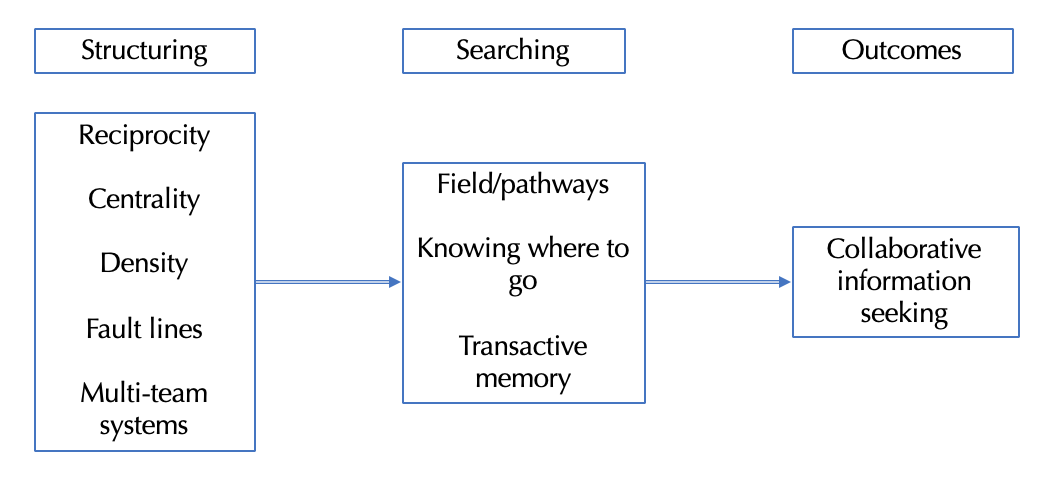

Analysis and results: Network analysis approaches offer the promise of more nuanced approaches and diagnostic tools that could address these issues by focusing on its elements: reciprocity, centrality, density, fault lines, multi-team systems, fields and/or pathways, knowing where to go, and transactive memory.

Conclusion: Network analysis of interprofessional health care teams holds much promise for addressing many current health care problems such as diagnosing fault lines in teams that lead to the blockage of critical information related to care.

Introduction

Teams have been important elements of healthcare delivery for over 100 years with accelerating usage over the last couple of decades, as technology has continued to rapidly develop and medical care has grown more complex (Poole and Real, 2003). Groups take many forms in healthcare settings: grand rounds, research groups, nominal care groups, ad hoc groups, interdisciplinary teams, and on and on. They serve a range of critical functions: sense making, creating, sharing, and distributing knowledge, adopting and implementing innovations, and collaborating (Poole and Real, 2003, p. 66). Team success often depends on effective information gathering (Ilgen, Hollenbeck, Johnson, and Jundt, 2005) and teams could be considered information processing units; they encode, store, and retrieve information (Henttonen, 2010). They, then, cognitively process this information to reach decisions on courses of action. If there is consensus on a course, then this leads to more commitment, higher performance, and better implementation of decisions. A major raison d’etre for teams is the potential of diverse members pooling information collaboratively in such a manner that better decisions are made and actions taken (Shah, 2015). For example, patients could be viewed as shared events that then become a vector for the dissemination of information among healthcare providers within a network (Parchman, Scoglio, and Schumm, 2011). Here we will focus on the role communication networks can play in more nuanced approaches to collaborative information seeking in interprofessional healthcare teams. Inter-professional healthcare teams are composed of members who represent different professions who are brought together to share their relevant expertise in providing healthcare to patients.

Unfortunately most models of information seeking focus on the individual rather than social searching (Evans and Chi, 2010). Given the complexity of our healthcare system, increasingly the operation of inter-professional healthcare teams are critical to healthcare outcomes. It is widely believed that well-functioning healthcare teams can improve patient care and increase safety (Meltzer, et al.2010; Thomas, Sexton, and Helmreich, 2003), in part stemming from the recommendations of the very influential Institute of Medicine report, To err is human: building a safer health system (Buljac-Samardzic, Dekker-van Doorn, van Wijngaarden, and van Wijk, 2010). More recently, medical errors have become recognised as the third leading cause of death in the US (Christensen, 2016). Teams may make fewer mistakes than individuals (Baker, Day, and Salas, 2006), increasing quality (e.g., improving patient safety) by ensuring that more than one set of eyes examine a problem. Social searching brings in group dynamics which can enhance motivation, increase persistence, bring in different points of view, and build in double checks (Johnson, 2018b).

Here we argue that social network analysis offers many concepts that enrich our understanding of collaborative information seeking in inter-professional healthcare teams. The potential benefits of inter-professional healthcare teams include: the many different types of expertise and points of view that are brought to the table; greater access to a wider range of resources outside of the team; shared risks and outcomes; and greater learning and potential growth among team members. However, there are problems with team communication (discussed in the next section). Collaborative information seeking themes are then briefly covered, before a discussion of how network analysis concepts could help research and understanding of collaborative information seeking and communication within inter-professional healthcare teams. We systematically review network analysis concepts (see Figure 1) that can enrich our understanding.

Problems with internal team communication

'Teams have a well-defined focus and a sense of purpose and unity that members of other groups do not share' (Poole and Real, 2003, p. 370). Team members share leadership roles, are accountable, encourage open-ended discussion, encourage listening, and measure their performance (Katzenbach and Smith, 2013). Teams may be most appropriate when the problem to be addressed is complex, requiring a high degree of interdependence among team members (Sheard and Kakabadse, 2004), something that is certainly true of modern healthcare.

In spite of their pervasiveness, there are still numerous problems with the operation of teams in medical care settings: poor communication; rigid roles; generally disappointing performance (Poole and Real, 2003); incompatible communication styles; negative team norms; power differentials; and role conflict (Johnson, 2016; Quinlan, 2009). A substantial percentage of malpractice claims stem from communication errors (Reimer, Russell, and Roland, 2016). Unfortunately, across a wide array of settings, collaboration failures are perhaps more common than collaboration successes (Hollingshead, Brandon, Yoorn, and Gupta, 2011; Koschmann, 2016). 'People die due to communication failures' (Nair, Fitzpatrick, McNulty, Click, and Glembocki, 2012, p. 115). It has been estimated that up to 80% of healthcare errors are caused by human factors associated with poor team communication (Xyrichis and Ream, 2008).

The importance of coordination is amplified as interdisciplinary teams are increasingly operating in virtual communication environments (Faraj and Xian, 2006). As interdependence and associated coordination modes become more complex, the costs of communication and the burdens of decision making increase (Thompson, 1967). This implies that under norms of rationality and efficiency organisations will try to minimise the need for more complicated modes of coordination, interdependence, and associated information seeking. This is one of the reasons healthcare teams often revert back to the traditional hierarchical arrangements: they may not be effective, but they certainly are efficient. They also may be perfectly appropriate in routine situations where solutions are clear (Keith, Demirkan, and Goul, 2010; Shah, 2012). It has been suggested that knowledge in healthcare organisation can be associated with three frameworks: routinised, emergent, and political, with teams particularly appropriate for enhanced understanding in the latter two frameworks (Murphy and Eisenberg, 2011).

The traditional formal hierarchical structure of medical teams make it difficult for them to achieve desired levels of coordination and cohesion (Baker, et al. 2006; Shah, 2014). Realising the potential of teams is often very problematic (Salas, Sims, and Burke, 2005), in part, because physicians still have the primary personal responsibility for patient treatment (Barzdins, 2016; Sonnenwald, 2014). Surgeons, for example, often resist new routines which require them to depend on collaboration and communication with others to 'shift from "order giver to team member"' (Edmondson, Bohmer, and Pisano, 2001, p. 699). Under formal norms of rationality and efficiency, organisations will try to minimise the need for more complicated modes of coordination and interdependence, which has often mandated that near militarily organised hierarchical arrangements have been seen as necessary for action units like trauma teams (Klein, Ziegert, Knight, and Xiao, 2006). Collaboration load has been used to refer to the additional effort needed to work with others and cognitively process the additional viewpoints inherent in diverse teams (Shah, 2014). Communication, and relatedly coordination, tends to follow the professional status hierarchy of complex teams, resulting in centralisation. This is especially so for those teams containing volunteers and, as a result, volunteers often feel alienated from these teams (Berteotti and Seibold, 1994). However, inter-professional healthcare teams offer the potential of diverse members reciprocally pooling information, reflected in higher density (see Figure 1), in such a way that better decisions are made and actions taken. Team success, then, often depends on effective information gathering and sharing, reflected in reciprocal relationships (see Figure 1).

Collaborative information seeking

There has been an increasing focus on collaborative information seeking (McNeese and Reddy, 2017), particularly in healthcare settings where the diversity within inter-professional healthcare teams can result in misunderstandings and blockages in the flow of information. There is increasing recognition that it is not the sole individual seeking information to support their own decision-making that is the norm in organisations. For example, collaborative information seeking through such mechanisms as triage, timeouts, coordinating nurses, and the use of electronic whiteboards is at the core of work flow in emergency departments (Hertzum and Reddy, 2015). In a systematic review of communication papers focusing on collaboration Lewis (2006) found these common elements: a focus on activity; a focus on relationships; a movement towards equality in the relationships; a focus on process; and a perception that relationships were emergent, informal, and volitional. Healthcare settings are growing more and more complex, with people trained in a variety of professions, which often have their own normative expectations for what constitutes a valid information search. One discouraging element of healthcare-based practices is that it is not necessarily the best idea that will win out; often implementation depends on the willing acceptance of a variety of actors, including such outside forces as governmental agencies and insurers (Botello-Harbaum, 2013).

Collaborative information seeking is still a nascent field, drawing on a number of different disciplines, often with a focus on human interface with information technology, such as electronic health records and work performed at a distance (Hansen, Shah, and Klas, 2015; Sonnenwald, 2014). Shah's C5 model suggests that collaborative information seeking entails overlapping sets of: communication (information exchange), contribution, coordination, cooperation, and collaboration (Shah, 2012, 2015). Collaborative information seeking has been defined as: 'the study of the systems and practices that enable individuals to collaborate during the seeking, searching, and retrieval of information' (Foster, 2007, p. 330). Network analysis (see Figure 1) provides the communication frameworks that enable collaborative information seeking by providing a structure (e.g., centralisation) that determines the nature of searching (e.g., the pathways people follow).

Network analysis

Network analysis represents a very systematic means of examining the overall configuration of relationships within a social system. The most common form of graphic portrayal of networks contains nodes, which represent social units (e.g., individuals, groups), and relationships, often measured by the communication channel used to express them, of various sorts between them. The content of these relationships determines the substantive richness of network analysis for addressing collaborative information seeking. The graphic roots of network analysis rest on mathematical expressions that are the foundations of a sophisticated network analysis package like PAJEK (de Nooy, Mrvar, and Batagelj, 2005).

Owing to its generality, network analysis is used by almost every social science to study specific problems. Network approaches are increasingly common in team and leadership research, especially for the critical role of centrality and density measures in approaching different aspects of this problem (Mathieu, Maynard, Rapp, and Gilson, 2008; Sparrowe, 2014) and they have been increasingly applied to healthcare settings (Bae, Nikolaev, Seo, andCastner, 2015).

Figure 1: Network analysis and collaborative information seeking in inter-professional healthcare teams

Network analysis approaches to the problem of collaborative information seeking offer powerful tools for analysing the social structure of teams that provides a context for how members come to understand their specialised roles in collaborative information seeking. Figure 1 specifies the network properties that determine effective collaborative information seeking. Firstly, are the structuring concepts that reflect differing institutional levels: reciprocity reflects the dyadic level focusing on interpersonal relationships; centrality assesses an individual’s position within a network; density is measured by the number of actual linkages reported within a network grouping; fault lines suggest the divisions within these groupings; and multi-team systems capture the interaction of various groups within the healthcare systems. The structure of relationships captured by these concepts provides the initial starting point for information seeking and describes the current flow of information. Searching behaviour occurs when this structure has not provided the information needed for the team’s work. How inter-professional healthcare teams go about acquiring the information they need is then reflected in fields/pathways, knowing where to go, and transactive memory. They determine the ultimate outcomes of collaborative information seeking. We now elaborate on each of these concepts, with sections covering the structuring concepts and then the searching concepts listed in Figure 1.

Structuring property: reciprocity

Relationships are the fundamental unit in a network analysis. Reciprocity refers to whether or not both parties to a relationship characterise it in the same way. Unreciprocated linkages, linkages where one party does not agree that a relationship exists, are quite frequent in organisations. Monge, Edwards and Kirste (1978), for example, report percentages of reciprocation ranging from 37% to 100% across a number of empirical studies. Levels as low as 26% have been found in medication-advice-seeking, inter-professional networks in emergency departments (Crewswick, Westbrook, and Braithwaite, 2009).

One of the first transitional attempts to deal with the complexity of communication in organisations was Katz and Kahn's (1978) notion of communication circuits, which they argued had five major characteristics: the size of the loop that reflects the organizational coverage of a particular message; is the message repeated or modified as it passes through a circuit; the feedback or closure character of the circuit (feedback implies that a response is received to a message, whereas in a closed circuit there is no response); efficiency; and overall fit with system functioning. The more free-flowing the communication in teams, the greater the possibilities for errors in transmission, but errors can also be mitigated by feedback that corrects errors through reciprocated linkages.

Structuring property: centrality

Classically, Freeman (1977) distinguished three types of centrality. Degree or local centrality refers to the number of immediate contacts an individual has, while closeness or global centrality refers to the number of ties needed to reach all others in a network. Betweenness centrality refers to strategic location as the shortest distance between two points in the network. If there is a need to disseminate information, members who have betweenness centrality have a substantial advantage (Meltzer, 2010).Brokers have betweenness centrality, since they are the go-betweens for transmission of messages from one grouping in a network to another and therefore can facilitate, impede, or bias the transmission of messages from different groups. It has been found that nurses and doctors are separated in medication advice seeking networks, reflecting a low level of cross-professional communication, but that pharmacists are quite central (Creswick and Westbrook, 2010). Interestingly, team leaders stimulate creativity when they are central to its external information network, while maintaining a position within the group that is neither too central nor too peripheral (Kratzer, Leenders, and Van Engelen, 2008). The bridging characterised by external network linkages ‘indicates access to new resources and opportunity for innovation and profit…’ (Hoppe and Reinelt, 2010, p. 601).

Prominent actors, such as liaisons, are those most visible to others (Wasserman and Faust, 1994). They may be the individuals most sought after for information, who have expert power, and those viewed as most credible. These actors are prestigious to the degree they have ties directed at them, such as those requesting information, with many more relationships coming in than going out (Wasserman and Faust, 1994), reflecting processes of preferential attachment.

Both the traditional opinion leadership (Katz and Lazersfeld, 1955) and network role literature suggest that people seek out knowledgeable individuals in their informal networks for answers to their questions (Johnson, 2009). Not only do opinion leaders serve to disseminate ideas, but they also, because of the interpersonal nature of their ties, provide additional pressure to conform as well (E. Katz, 1957). Some have gone as far as to suggest that group membership can be predicted based on an individual's information seeking preferences (Kasperson, 1978), with suggestions that opinion leaders are information brokers at the edges of groups (Burt, 1999). They are brokers twice over, since through cohesive ties they pass information to weak structurally equivalent individuals, thus triggering contagion across the social boundaries of groups (Burt, 1999). However, the literature is less clear as to how people come to know who these individuals are. Reputation and prestige may be particularly important in this process, but accessibility is also critical.

Ever since the initial studies of small group communication networks an individual’s centrality in a network has been directly tied to leadership (Shaw, 1971). A very interesting study in this regard was conducted by West and her colleagues (West, Barron, Dowsett, and Newton, 1999) which compared networks of clinical directors of medicine and directors of nursing. They found these networks to be very different; with the one for nurses very centralised, which enhanced the gathering of and dissemination of information, and the one for clinical directors very dense, with a greater likelihood that their communications would have social influence that could facilitate or arrest changes. Indeed, hierarchical relationships, often revealed by centrality, have been identified as a major problem for the operation of inter-professional healthcare teams across a wide range of studies (Bae, et al. 2015).

Structuring property: density

Perhaps the greatest level of development in network indices comes in the area of the relative connectiveness of larger social aggregates, either groups and/or cliques, or the larger social system. Essentially the issue of connectiveness refers to whether or not all of the possible linkages in an aggregate are being utilised. Even a group of seven has many possible combinations of internal linkages; the more of them that are in actual use, the higher the connectiveness of the group. This has important implications for processes like attitude formation in groups (Danowski, 1980) and a group's relative cohesiveness.

While centralisation describes the degree to which cohesion is organised upon particular nodes, density, which is determined by dividing the number of actual links in a particular network by the number possible, describes more holistically the level of connectiveness within a network (Scott, 2000). While communication networks often have low densities (Johnson, 2005), teams should be islands of higher density in sparser social structures. Density has been proposed as an operationalisation of shared leadership (Carson, Tesluk, and Marrone, 2007) and is commonly used as a measure of the internal network structure of teams (Henttonen, 2010). It has been positively related to team performance and member satisfaction (Henttonen, 2010). It has also been described as the sort of bonding of a 'trusted community where interactions are familiar and efficient' (Hoppe and Reinelt, 2010, p. 601).

Core-periphery and hierarchical group structures, both indications of lower density and lower levels of lateral communication, have been associated with lower performing work groups (Cummings and Cross, 2003). In short, 'for higher performing groups, sufficient ties among members to facilitate information flow, without over-reliance on one member, does seem important' (Cummings and Cross, 2003, p. 210). Interestingly, a network analysis of multi-disciplinary long-term care teams found two sub-teams with different functions exhibiting some multiplexity: one reflecting a denser structure indicative of teamwork and decision making among high status health professionals; and the other reflecting a more mechanistic centralised structure for nurses, with very little sharing of information between the two. In essence this reflected a clearly defined hierarchy of 'we decide, you carry it out' (Cott, 1997, p. 1411). Core-periphery structures have been studied in operating teams for their implications for the time of day in which surgery is performed and for which procedures were involved (Anderson andTalsma, 2011).

Structuring property: fault lines

The very professional diversity that promises to result in more effective decisions can result in teams splintering into coalitions surrounding various interests and being paralysed by the resulting conflict. Different perspectives resulting from the varied backgrounds of team members and the differing information they bring to the table results in a storming stage where conflict over the direction of the group occurs and cooperation among group members may be affected (Tuckman and Jensen, 1977). This can result in divisive internal coalitions forming within the team. Relatedly, in more complex groupings representing a variety of professions and volunteers, communication tends to occur most frequently among those who share similar status (Berteotti and Seibold, 1994), reflecting a general problem in healthcare teams where professionals are likely to share information most with others who are like them (Bae, et al. 2015; Crewswick and Westbrook, 2009).

The level of conflict within a team and how it is resolved often depends on the formation of coalitions. As teams grow larger the possibility of the development of subgroups within them, that have differing interests, increases. Members often coalesce upon differing ideas (e.g., diagnoses) which has the inevitable result of impacting on conflict and eventually the level of cooperation within the group. Polarisation among factions can lead to paralysis and an inability to make any decision. If a decision is made, sometimes the losers will passively or actively sabotage it. Minorities that perceive they are treated unfairly can withdraw from the group and have low levels of commitment to group work.

Subgroups are subsets of team members that are characterised by their unique form or degree of interdependence. Carton and Cummings (2012) exhaustive theory of subgroups and work teams suggests that there are three underlying factors to the formation of subgroups: identity, resources, and knowledge. Another important factor relating to subgroups is the number of their members and whether they are roughly equal in size, or whether a subgroup is a clear minority of team members. Resource based subgroups often develop coalitions, represented by terms such as factions, alliances and blocs, to gain more power in the context of team politics. Teams that have two or more identity subgroups may experience interesting dynamics. Work teams with equal sized subgroups may get locked into conflicts related to values and ideologies. In contrast, subgroups that are unequal in size may result in considerably different experiences among their various members, with minority subgroups feeling threatened and majority subgroups feeling relatively comfortable. Team learning benefits from situations when there is a middle ground, with neither too much asymmetry in perceptions of fairness, nor too little power centralisation.

Fault lines often develop along attributes such as diversity, both surface and deep (e.g., professional affiliation). Almost all teams experience some fault lines. Members who share the same attributes, in contrast to another subset of members with a clearly distinct set of attributes, may experience considerable difficulties. Teams can benefit from the divergent ways that different sub groups acquire knowledge and interpret information. However, subgroups dynamics can also impair the ability of team members to experience a convergence of mental models and common understandings (Carton and Cummings, 2012) and the strength of fault lines impacts the effectiveness of communication (Mathieu, et al. 2008). Unfortunately, left to their own devices, most teams fail to learn optimal ways of integrating diverse opinions (Ilgen, et al. 2005). However, multiplexity which reflects the interaction of different types of networks (e.g., work, advice-sharing and friendship), can result in friendship ties that can bridge work-related subgroups that are cleaved by fault lines (Ren, Gray, and Harrison, 2015).

Structuring property: multi-team systems

Moving up a level, there is increasing interest in how multi-team systems coordinate their efforts (Carter and DeChurch, 2014). These collective entities represent two or more teams that share a superordinate goal, such as patient safety. Failures relating to these systems have become an increasing concern. So, the Department of Homeland Security was formed in part because of the lack of information sharing among various intelligence agencies in the U.S. Often the individual teams in multi-team systems exhibit high levels of commitment and cohesion, but the inter-team relationships are characterised by conflict and other dysfunctions. While there may be fully centralised vertical leadership of multi-team systems, shared leadership of these teams might be rotated, distributed, or simultaneously shared. Relationships among them have been cast in network terms, with interest in such issues as the diameter of relationships among the teams. A network’s diameter is the largest number of paths between two nodes in the network. Large diameters can negatively impact performance because of the delays in communication and coordination that are likely to occur.

Structuring properties summary.

Team success depends on effective information gathering and teams can be considered information processing units; they encode, store, and retrieve information. They, then, cognitively process this information to reach decisions on courses of action. If there is consensus on a course, then this leads to more commitment, higher performance, and better implementation of decisions. Figure 1 specifies the structuring properties that reflect the functioning of inter-professional healthcare teams. The level of reciprocity between separate dyads reflects the strength and flow of information sharing between individuals. Some individuals are more important in inter-professional healthcare teams than others, reflecting processes of preferential attachment and expertise that is evidenced in their relative centrality in the flow of information. The overall pattern of information sharing is determined by whether or not there is widespread sharing of information reflected in higher densities and whether or not fault lines have developed. These fault lines could reflect professional divisions, such as those often found between physicians and nurses, that can lead to blockages in information flow. Given the complexity of our healthcare system, teams often depend on information provided by other teams in multi-team systems to accomplish their work.

Searching property: fields and/or pathways

One constraint on information seeking is the information field within which the individual is embedded. This field encompasses the carriers of information an individual is normally exposed to and the sources an individual would normally consult when confronted with a problem, represented here by the forgoing structuring concepts in network analysis research. This information environment can be incredibly rich, including access to sophisticated data bases, advanced satellite systems, and search engines for computerised information retrieval. Information fields contain resources, constraints, and carriers of information that influence the nature of an individual's information seeking (Archea, 1977; Hagarstrand, 1953). The concept of field has a long tradition in the social sciences, tracing back to the seminal work of Lewin (Scott, 2000) and various philosophical traditions (Schatzki, 2005), with recent variants like information horizons (Sonnenwald, Wildemuth, and Harmon, 2001), information grounds (Fisher, Durrance, and Hinton, 2004), small worlds (Fulton, 2005; Huotari and Chatman, 2001), and social positioning (Given, 2005). In some ways the totality of an individual’s information fields has analogies to the notion of social capital, in that it describes the resources an individual has to draw upon when confronting a problem. When individuals share the same information field they also share a context, which provides the information grounds for further interaction (Fisher, Erdelez, and McKechnie, 2005). As a best-selling book on social networks puts it, 'The more contexts two people share, the closer they are, and the more likely they are to be connected' (Watts, 2003, p. 116). Thus, in a sense, individuals are embedded in a field that acts on them; however, individuals also make choices about the nature of their fields, the types of media they attend to, and the friendships they form, which are often based on their information needs.

The nature of an individual's stable information field, which in part reflects their pattern of network ties, can shape their more active information seeking, since it provides a starting point. As individuals become more focused in their information seeking, they change the nature of their information field to support the acquisition of information related to particular purposes. In this way individuals act strategically to achieve their ends and in doing so construct local, temporary communication networks that mirror their interests.

The presence of weak ties (Granovetter, 1973) may expose individuals to information that prompts change, and this may trigger an expansion of the individual's information field and blazing of new pathways. Pathways describe the behaviour people engage in as they respond to these forces. Johnson and his colleagues (Johnson, Andrews, Case, Allard, and Johnson, 2006) have developed the concept of pathways, the route someone follows in the pursuit of answers to questions. So, when an inter-professional healthcare team is confronted with an unusual cluster of symptoms they may need to consult sources beyond their fields, initiating new pathways to reach others who may have the information they require.

Network indices associated with pathways primarily deal with how easily a message can flow from one node to another node. Walks that begin and end at the same node are termed closed (Wasserman and Faust, 1994). Closure is an important property since it allows some feedback concerning how information has been processed (Katz and Kahn, 1978). A path’s length is determined by the number of lines and geodesic distance is determined by the shortest path, as in package delivery. Reachability focuses on how many links a message must flow through to get from one node to another, usually expressed in terms of the shortest possible path, an issue which has profound implications for an individual's ultimate influence in a social system (Barnes, 1972).

Pathways are also reflected in the classic small world problem that has received renewed attention with the advent of the Internet (Watts, 2003). The twist is that we are not seeking a particular target other, but rather targeted information that another may possess. So, one clue, may lie in the assumptions that others might have of the unique attributes of radial others (e.g., they have wide-ranging contacts that might lead me to my target). In this sort of expertise network, knowledge may substitute for formal authority for identification of targets, but similar problems of access, managing attention, overload, and queuing may result (Krackhardt, 1994). There is also the possibility that friction along paths can decrease the easy flow of knowledge in networks (Ghosh and Rosenkopf, 2015).

In the classic small world problem the task is for an individual to contact a distant target other, previously unknown to them, through intermediaries (Barabasi, 2003). Most of the research in this area has focused on the overall structural aspects of the linkages through which an individual goes, less attention has been given to how individuals strategically target particular intermediaries. Findings in e-mail networks suggest individuals are more likely to forward a message when the intended recipient appears easier to reach (Newman, Barabasi, and Watts, 2006). Watts (2003) has examined the latter aspect of the problem. He suggests individuals start with two broad strategies. One is to engage in a broadcast search in which you approach everyone you know, they in turn contact everyone they know until a target is reached, or in this case an answer is found. This approach is crude and has some obvious problems: one, it reveals your ignorance broadly; two, it implicates a large number of others, distracting them from their other tasks; three, it may produce large volumes of information that need to then be filtered by some criteria (e.g., credibility, relevance, and so on.). Reach and selectivity are often conflicting strategies for information dissemination in organisations. In an ideal world one might want to reach everyone with an inquiry, but the costs of pursuing this strategy are prohibitive (Monge and Contractor, 2003), especially for problems one would like to keep confidential.

The alternative, a directed search, may start by developing some criteria (e.g., I will only ask dieticians). Here search targets may be categorised in broadly stereotypic ways as having the potential information we need. Of course, the best of all criteria is some indication of a target’s position in the overall social structure (e.g., are they well connected to diverse others; what social groups do they belong to; are they homophilous to me?) (Watts, 2003). In general, Watts has found networks to be more easily searchable when individuals can judge their similarity to target others along multiple dimensions. Interestingly, when individuals are required to carry out repeated directed searches an overall structure evolves, that does not result in bottlenecks at the top of the hierarchy, that are highly searchable (partly because of the recognition of more weak ties), and that are relatively robust in response to environmental changes. Watts goes on to suggest that developing more effective social structures may be a more effective solution to search problems than a reliance on centrally designed problem-solving tools and data bases. So, focusing on the network properties of inter-professional healthcare teams could result in an improvement in search resulting from an understanding of its emergent properties, such as linkages to others identified in transactive memory as likely repositories of the needed information.

Searching property: knowing where to go

While much research has focused on the issue of knowledge transfer, far less has considered the issues of individuals seeking out existing knowledge. The ability to do this may be constrained by the simple fact that those seeking knowledge may not be aware of those who have it …. (Kayworth and Leidner, 2003, p. 245).

One of the things that characterises effective decision making is knowing what the other knows and when to turn to them (Cross, Rice, and Parker, 2001). Partly growing from the classic debates relating to the validity of self-reports of network linkages, some have suggested that individuals have strong, albeit often crude, categorical, intuitions of surrounding social structures, that they know who is linked to whom in a stable network (Corman and Scott, 1994), and by implication they have some awareness of where information resides.

However, here we are not exploring how people get routine information, from their strong ties, which may indeed have been formed to create an information field. Rather, we are interested in how people actively search for answers to questions that may exceed the capability of their existing network. This question is given some additional impetus by the classic findings of the information seeking literature, that people will seek information from interpersonal sources who: can summarise information for them in meaningful terms; are accessible; and that people are not terribly persistent nor sophisticated in their search behaviour (Johnson, 2015). It also addresses the organisational quandary of how to make connections between new knowledge and those who should have it (Schulz, 2001).

The literature has hinted at a number of factors that may shape searches for new information: relationships with weak ties; opinion leadership; the more general role of brokers; accessibility; and the status structures in which searchers are embedded. Prior experience with a source and that person’s trustworthiness are particularly important. Cross, et al. (2001) have described this in more contemporary terms as the degree of safety in a relationship that promotes both learning and creativity. In inter-professional healthcare teams the development of trusting relationships and enhanced understanding of others’ skill sets through continued interactions are likely to create more efficient and effective searches, reflected in the transactive memory processes to which we now turn.

Searching property: transactive memory

a knowledge community or network would seem to require a human hub or switch, whose function is as much to know who knows what as to know what is known (Earl, 2001, p. 225).

Knowing who knows what is a fundamental issue; it answers the know-who question (Borgatti and Cross, 2003). Using computer search engines and networks as a metaphor can also lead us to interesting insights into this human systems problem. If people can be considered to be information processing units, then every social group can be viewed as a computer network with analogous problems and solutions (Wegner, 1995), developing means of retrieving and allocating information to collective tasks (Palazzolo, Serb, She, Su, and Contractor, 2006). Some have argued, then, that the fundamental unit of transactive memory is task-expertise-person units that answer in fundamental ways the know-who question (Brandon and Hollingshead, 2004; Hollingshead, et al. 2011). A transactive memory system within a network, then, reflects one’s awareness of task-expertise-person units that can be accessed much as one accesses data banks within information systems.

Information sharing in transactive memory systems can play a critical role in medical decision making (Reimer, et al. 2016). It can improve the efficiency and effectiveness of a team by promoting a division of labour on certain information processing tasks, whilst also providing mechanisms for integration. Groups in which member’s expertise is made public have been found to share more unique information (Thomas-Hunt, Ogden, and Neale, 2003). The value of transactive memory manifests itself over time through repeated interactions that have meaningful consequences (DeChurch and Mesmer-Magnus, 2010). Several interrelated processes are involved, including retrieval coordination, directory updating, and information allocation (Palazzolo, 2006). Retrieval coordination specifies procedures for finding information. Directory updating involves learning who knows what, while information allocation assigns memory items for group members.

So, an inter-professional healthcare team concerned with developing a diagnosis might initially meet to determine the expertise of its members, assigning them research tasks, and specifying procedures for gathering information related to their tasks in a format that can be shared. For ongoing groups, task-expertise-person units can be assigned formally based on one’s role, from memory, from various social constructions, from documents and so on (Brandon and Hollingshead, 2004). Once someone’s expertise is known they are more likely to become the objects of information searches, increasing their centrality (Borgatti and Cross, 2003), with reciprocity often driving future interactions and further development of transactive memory (Hollingshead, et al. 2011).

Searching properties summary

Pathways reflect the pattern of activities inter-professional healthcare teams will engage in to acquire the information they need. Knowing where to go greatly facilitates this searching. Transactive memory often results from past experiences with potential sources of information and an assessment of how likely they are to provide the information that is required. So, an inter-professional healthcare team that needs critical diagnostic information may initiate a path along their weak ties to those who they think are likely repositories. If they know highly credible sources their search may require few linkages, but if they are confronted with an unusual problem they may not know of likely sources and as result have near random paths, of greater length through their extended network.

Outcomes

Effective collaborative information seeking is reflected in sense making, creating, sharing, and distributing knowledge, adopting and implementing innovations, and collaborating. Teams have the potential of diverse members pooling information collaboratively in such a manner that better decisions are made and actions taken. However, collaborative information seeking is often a great challenge for teams. Unfortunately there is no guarantee that time spent on developing collaboration in inter-professional healthcare teams will improve the quality or safety of care, since they are vulnerable to cliques, professional and gender heterophily, and over-reliance on central individuals (Cunningham, et al., 2012). Team work can be used as a guise for higher status healthcare professionals to maintain control over others, while often medium status members hope to use it to gain status and control (while maintaining control over their underlings) (Cott, 1997).

Central individuals are doubly vexed since they are the focus of activities and may not have the time to engage in thorough searches on their own. One advantage of working in teams is that many people may combine their efforts to collaborate to arrive at the best information needed to support decision making. It has been suggested that team members can become catalysts for innovation by being aware of the needs of other network members and respecting the diversity of their linkages to external sources of information (Tortoriello, McEvily, and Krackhardt, 2015). From an information processing perspective, one of the primary reasons for the formation of a team is to promote the search for information from a variety of sources, then to interpret the information that is gathered from a variety of frameworks, and ultimately to arrive at a decision that reflects the input of the various team members. However, in practice central individuals, by default often physicians, either directly or indirectly, often limit the alternatives discussed by their actions or by their presence (Bae, et al. 2015). In some worst-case scenarios, the team processes information as effectively as one central person would do on their own.

Discussion and conclusion

There have been major reviews of both collaborative information seeking (e.g., Shah, 2014) and network analysis in healthcare contexts (e.g., Bae, et al. 2015), but they have not focused on the dynamics represented by inter-professional healthcare teams. As we have seen, network analysis approaches offer the promise of more nuanced approaches and diagnostic tools that can address these issues by focusing on its structuring elements (see Figure 1), reciprocity, centrality, density, fault lines, multi-team systems, that shape searching processes including fields/pathways, knowing where to go, and transactive memory. This review establishes a framework for future investigations and points to some critical areas for future research.

This study is important because it highlights two vital areas of further research in network analysis for collaborative information seeking in inter-professional healthcare teams. One of the major emerging opportunities for future research in our increasingly complex healthcare systems is the operation of multi-team systems, which in many ways moves these factors up a level. So, the initial intake of a patient in an emergency room is the starting point for the operating room team who then hand the patient off to intensive care. In this type of network analysis, nodes become the team and links the relationships between teams. So, different individuals may handle the intake and pass on this information to different operating room technicians. However, these cross-level phenomena have not been carefully examined to determine how differences at the dyadic level may impact inter-team interactions. They could, for example, impact fault lines in teams that lead to the blockage of critical information related to care.

Another important issue for future research is the impact of virtual technologies and training on inter-professional healthcare team performance (Sonnenwald, 2014). Unfortunately there is a shortage of software tools and other specialised approaches that promote and support collaborative information seeking (Shavner and Tang, 2014), with most tools at an academic research stage lacking scalability, ease of use, and an array of features that mitigates against their widespread acceptance (Shah, 2015).

Future research also needs to focus on the likelihood that inter-professional healthcare teams will move beyond their currently available information, reflected in structuring, to engage in active searching for information which virtual technologies and improved software tools could facilitate. There is ample evidence that the press of time, unfamiliarity with sources, and inadequate information skills and tools inhibit such searches (Johnson and Case, 2012). The existing structuring of relations may not have adequate information for successful collaboration and patient care. This provides a new opportunity for information professionals, like medical librarians, who, in addition to the traditional knowledge of software and data bases, should focus on the human resources who are the most likely ones for inter-professional healthcare teams to draw on (Johnson, 2018a). Future research that enriches our understanding of the linkage between structuring and searching is needed for improved collaborative information seeking.

One role of leadership in self-managing teams would be providing people with the resources and skills necessary to seek information related to their problems and/or concerns by facilitating and creating rich information fields. Another strategy is to increase the salience of these issues through better training programmes that address optimal search behaviour and acquaint individuals with unfamiliar sources of information.

A number of difficult things must be accomplished before teams can function effectively in healthcare settings. Without good communication and cooperation inter-professional healthcare teams will lack vital information and the quality of care will be at risk (Crewswick and Westbrook, 2009). A greater understanding of the specific network factors that determine quality outcomes is needed (Bae, et al. 2015). Here a broad range of concepts (see figure 1) have been presented which offer rich possibilities for diagnosing the structure of teams. These in turn provide the initial starting point for active searching which can then lead to more effective collaborative information seeking.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Cole and the anonymous reviewers for their many helpful suggestions.

About the author

Dr. J. David Johnson is University Research Professor, Department of Communication, Blazer Dining Hall, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506, USA. His doctorate in Communication is from Michigan State University. His research areas of interest focus on the health-seeking behavior, teamwork and leadership, and network analysis. He can be contacted at jdj@uky.edu.

References

- Anderson, C. & Talsma, A. (2011). Characterizing the structure of operating room staffing using social network analysis. Nursing Research, 60(6), 378-385.

- Archea, J. (1977). The place of architectural factors in behavioral theories of privacy. Journal of Social Issues, 33(1), 16-37.

- Bae, S., Nikolaev, A., Seo, J.Y. & Castner, J. (2015). Healthcare provider social network analysis: a systematic review. Nursing Outlook, 63(5), 566-584.

- Baker, D.P., Day, R. & Salas, E. (2006). Teamwork as an essential component of high-reliability organizations. Health Services Research, 41(4), 1576-1598.

- Barabasi, A.L. (2003). Linked: how everything is connected to everything else and what it means for business, science, and everyday life. New York, NY: Plume.

- Barnes, J.A. (1972). Social networks. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Barzdins, J. (2016). Process-oriented knowledge system for health professionals as a tool for transition to hospital process orientation. International Journal of Healthcare Management, 9(4), 245-250.

- Berteotti, C.R. & Seibold, D.R. (1994). Coordination and role-definition problems in health-care teams: a hospice case study. In L.R. Frey (Ed.), Group communication in context: studies of natural groups (pp. 107-131). Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Borgatti, S.P. & Cross, R. (2003). A relational view of information seeking and learning in social networks. Management Science, 49(4), 432-445.

- Botello-Harbaum, M.T., Demko, C.A., Curro, F.A., Rindal, B., Collie, D., Gilbert, G.H., ... Lindblad, A. (2013). Information-seeking behaviors of dental practitioners in three practice-based research networks. Journal of Dental Education, 77(2), 152-160.

- Brandon, D.P. & Hollingshead, A.B. (2004). Transactive memory systems in organizations: matching tasks, expertise, and people. Organization Science, 15(6), 633-644.

- Buljac-Samardzic, M., Dekker-van Doorn, C.M., van Wijngaarden, J.D.H. & van Wijk, K.P. (2010). Interventions to improve team effectiveness: a systematic review. Health Policy, 94(3), 183-195.

- Burt, R.S. (1999). The social capital of opinion leaders. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 566, 37-54.

- Carson, J.B., Tesluk, P.E. & Marrone, J.A. (2007). Shared leadership in teams: an investigation into antecedent conditions and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 50(5), 1217-1234.

- Carter, D.R. & DeChurch, L.A. (2014). Leadership in multiteam systems: a network perspective. In D.V. Day (Ed.), The Oxford handboook of leadership and organizations (pp. 482). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Carton, A.M. & Cummings, J.N. (2012). A theory of subgroups in work teams. Academy of Management Review, 37(3), 441-470.

- Christensen, K. (2016, May 4). Medical errors may be third leading cause of death in U.S. CNN. Retrieved from http://www.cnn.com/2016/05/03/health/medical-error-a-leading-cause-of-death (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/74aAfV7jL)

- Corman, S.R. & Scott, C.R. (1994). Perceived networks, activity foci, and observable communication in social collectives. Communication Theory, 4(3), 171-190.

- Cott, C. (1997). "We decide, you carry it out": a social network analysis of multidisciplinary long-term care teams. Social Science & Medicine, 45(9), 1411-1421.

- Creswick, N. & Westbrook, J.I. (2010). Social network analysis of medication advice seeking interactions among staff in an Australian hospital. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 79(6), e116-e125.

- Creswick, N., Westbrook, J.I. & Braithwaite, J. (2009). Understanding communication networks in the emergency department. BMC Health Services Research, 9, 247-256. Retrieved from https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6963-9-247 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76Clw3Icx)

- Cross, R., Rice, R.E. & Parker, A. (2001). Information seeking in social context: structural influences and receipt of information benefits. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics-Part C: Applications and Reviews, 31(4), 438-448.

- Cummings, J.N. & Cross, R. (2003). Structural properties of work groups and their consequences for performance. Social Networks, 25(3), 197-210.

- Cunningham, F.C., Ranmuthugala, G., Plumb, J., Georgiou, A., Westbrook, J.I. & Braithwaite, J. (2012). Health professional networks as a vector for improving healthcare quality and safety: a systematic review. British Medical Journal Quality and Safety, 21(3), 239-249.

- Danowski, J.A. (1980). Group attitude uniformity and connectivity of organizational communication networks for production, innovation, maintenance content. Human Communication Research, 6(4), 299-308.

- de Nooy, W., Mrvar, A. & Batagelj, V. (2005). Exploratory social network analysis with Pajek. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- DeChurch, L.A. & Mesmer-Magnus, J.R. (2010). The cognitive underpinnings of effective teamwork: a metaanalysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 32-53.

- Earl, M. (2001). Knowledge management strategies: toward a taxonomy. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 215-233.

- Edmondson, A.C., Bohmer, R.M. & Pisano, G.P. (2001). Disrupted routines: team learning and new technology implementation in hospitals. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(4), 685-716.

- Evans, B.M. & Chi, E.H. (2010). An elaborated model of social search. Information Processing & Management, 46(6), 656-678.

- Faraj, S. & Xian, Y. (2006). Coordination in fast-response organizations. Management Science, 52(8), 1155-1169.

- Fisher, K.E., Durrance, J.C. & Hinton, M.B. (2004). Information grounds and the use of need-based services by immigrants in Queens, New York: a context-based, outcome evaluation approach. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 55(8), 754-766.

- Fisher, K.E., Erdelez, S. & McKechnie, L.E. (Eds.). (2005). Theories of information behavior. Medford, NJ: Information Today.

- Foster, J. (2007). Collaborative information seeking and retrieval. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 40, 329-356.

- Freeman, L.C. (1977). A set of measures of centrality based on betweenness. Sociometry, 40(1), 35-41.

- Fulton, C. (2005). Chatman’s life in the round. In K.E. Fisher, S. Erdelez & L. McKechnie (Eds.), Theories of information behavior (pp. 79-82). Medford, NJ: Information Today.

- Ghosh, A. & Rosenkopf, L. (2015). Shrouded in structure: challenges and opportunities for a friction-based view of network research. Organization Science, 26(2), 622-631.

- Given, L.M. (2005). Social positioning. In K.E. Fisher, S. Erdelez & L. McKechnie (Eds.), Theories of information behavior (pp. 334-338). Medford, NJ: Information Today.

- Granovetter, M.S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360-1380.

- Hagarstrand, T. (1953). Innovation diffusion as a spatial process. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Hansen, P., Shah, C. & Klas, C. (2015). Editorial. In P. Hansen, C. Shah & C. Klas (Eds.), Collaborative information seeking: best practices, new domains and new thoughts. New York, NY: Springer.

- Henttonen, K. (2010). Exploring social networks on the team level - a review of the empirical literature. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 27(1-2), 74-109.

- Hertzum, M. & Reddy, M.C. (2015). Procedures and collaborative information seeking: a study of emergency departments. In P. Hansen, C. Shah & C. Klas (Eds.), Collaborative information seekings: best practices, new domains and new thoughts (pp. 55-71). New York, NY: Springer.

- Hollingshead, A.B., Brandon, D.P., Yoorn, K. & Gupta, N. (2011). Communication and knowledge sharing errors in groups: a transactive memory perspective. In H.E. Canary & R.D. McPhee (Eds.), Communication and organizational knowledge: contemporary issues for theory and practice (pp. 133-150). New York, NY: Routlege.

- Hoppe, B. & Reinelt, C. (2010). Social network analysis and the evaluation of leadership networks. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(4), 600-619.

- Huotari, M. & Chatman, E. (2001). Using everyday life information seeking to explain organizational behavior. Library and information science research, 23(4), 351-366.

- Ilgen, D.R., Hollenbeck, J.R., Johnson, M. & Jundt, D. (2005). Teams in organizations: from input-process-output models to IMOI models. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 517-543.

- Johnson, J.D. (2005). Innovation and knowledge management: the Cancer Information Services Research Consortium. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Johnson, J.D. (2009). Managing knowledge networks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Johnson, J.D. (2015). The seven deadly tensions of health-related information behavior. Informing Science, 18, 225-234. Retrieved from http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol18/ISJv18p225-234Johnson1715.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76CqIEN5M)

- Johnson, J.D. (2016). Interprofessional care teams: the perils of fads and fashions. International Journal of Healthcare Management. 10(2), 127-134.

- Johnson, J.D. (2018a). Innovations as symbols in higher education. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Johnson, J.D. (2018b). Teams and their leaders: a communication network perspective. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Johnson, J.D., Andrews, J.E., Case, D.O., Allard, S.L. & Johnson, N.E. (2006). Fields and/or pathways: contrasting and/or complementary views of information seeking. Information Processing and Management, 42(2), 569-582.

- Johnson, J.D. & Case, D.O. (2012). Health information seeking. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Kasperson, C.J. (1978). An analysis of the relationship between information sources and creativity in scientists and engineers. Human Communication Research, 4(2), 113-119.

- Katz, D. & Kahn, R.L. (1978). The social psychology of organizations (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Katz, E. (1957). The two-step flow of communication: an up-to-date report on an hypothesis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 21(1), 61-78.

- Katz, E. & Lazersfeld, P.F. (1955). Personal influence: the part played by people in the flow of mass communications. New York, NY: The Free Press.

- Katzenbach, J.R. & Smith, D.K. (2013). The discipline of teams. In Harvard Business Review (Ed.), On teams (pp. 35-53). Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

- Kayworth, T. & Leidner, D. (2003). Organizational culture as a knowledge resource. In C.W. Holsapple (Ed.), Handbook of knowledge management 1: knowledge matters (pp. 235-252). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

- Keith, M., Demirkan, H. & Goul, M. (2010). The influence of collaborative technology knowledge on advice network structures. Decision Support Systems, 50(1), 140-151.

- Klein, K.J., Ziegert, J.C., Knight, A.P. & Xiao, Y. (2006). Dynamic delegation: shared hierarchical and deindividualized leadership in extreme action teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51(4), 590-621.

- Koschmann, M.A. (2016). The communicative accomplishment of collaboration failure. Journal of Communication, 66(3), 409-432.

- Krackhardt, D. (1994). Constraints on the interactive organization as an ideal type. In C. Heckscher & A. Donnelon (Eds.), The post-bureaucratic organization: new perspectives on organizational change (pp. 211-222). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Kratzer, J., Leenders, R.T.A.J. & Van Engelen, J.M.L. (2008). The social structure of leadership and creativity in engineering design teams: an empirical analysis. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 25(4), 269-286.

- Lewis, L.K. (2006). Collaborative interaction: review of communication scholarship and a research agenda. Communication Yearbook, 30, 197-247.

- McNeese, H.J. & Reddy, M.C. (2017). The role of team cognition in collaborative information seeking. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 68(1), 129-140.

- Mathieu, J., Maynard, M.T., Rapp, T. & Gilson, L. (2008). Team effectiveness 1997-2007: a review of recent advancements and a glimpse into the future. Journal of Management, 34(3), 410-476.

- Meltzer, D., Chung, J., Khalaili, P., Marlow, E., Arora, V., Schumock, G. & Burt, R. (2010). Exploring the use of social network methods in designing healthcare quality improvement teams. Social Science & Medicine, 71(6), 1119-1130.

- Monge, P.R. & Contractor, N.S. (2003). Theories of communication networks. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Monge, P.R., Edwards, J.A. & Kirste, K.K. (1978). The determinants of communication and communication structure in large organizations: a review of research. Communication Yearbook, 2, 311-331.

- Murphy, A.G. & Eisenberg, E.M. (2011). Coaching to the craft: understanding knowledge in healthcare organizations. In H.E. Canary & R.D. McPhee (Eds.), Communication and organizational knowledge: contemporary issues for theory and practice (pp. 264-284). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Nair, D.M., Fitzpatrick, J.J., McNulty, R., Click, E.R. & Glembocki, M.M. (2012). Frequency of nurse-physician collaborative behaviors in an acute care hospital. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 26(2), 115-120.

- Newman, M., Barabasi, A. & Watts, D.J. (Eds.). (2006). The structure and dynamics of networks. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Palazzolo, E.T. (2006). Organizing for information retrieval in transactive memory systems. Communication Research, 32(6), 726-761.

- Palazzolo, E.T., Serb, D.A., She, Y., Su, C. & Contractor, N.S. (2006). Coevolution of communication and knowledge networks in transactive memory systems: using computational models for theoretical development. Communication Theory, 16(2), 223-250.

- Parchman, M.L., Scoglio, C.M. & Schumm, P. (2011). Understanding the implementation of evidence-based care: a structural network approach. Implementation Science, 6. Retrieved from https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1748-5908-6-14 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76Cy9wepf)

- Poole, M.S. & Real, K. (2003). Groups and teams in healthcare: communication and effectiveness. In T.L. Thompson, A.M. Dorsey, K.I. Miller & R. Parrott (Eds.), Handbook of health communication (pp. 369-402). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

- Quinlan, E. (2009). The 'actualities' of knowledge work: an institutional ethnography of multi-disciplinary primary healthcare teams. Sociology of Health and Illness, 31(5), 625-641.

- Reimer, T., Russell, T. & Roland, C. (2016). Decision making in medical teams. In T.R. Harrison & E.A. Williams (Eds.), Organizations, communication, and health (pp. 65-81). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Ren, H., Gray, B. & Harrison, D. A. (2015). Triggering faultline effects in teams: the importance of bridging friendship ties and breaching animosity ties. Organization Science, 26(2), 390-404.

- Salas, E., Sims, D.F. & Burke, C.S. (2005). Is there a 'big five' in teamwork? Small Group Research, 36(5), 555-599.

- Schatzki, T.R. (2005). Periperal vision: the sites of organizations. Organization Studies, 26(3), 465-484.

- Schulz, M. (2001). The uncertain relevance of newness: organizational learning and knowledge flows. Academy of Management Journal, 44(4), 661-681.

- Scott, J. (2000). Social network analysis: a handbook. (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Shah, C. (2012). Collaborative information seeking: the art and science of making the whole greater than the sum of all. New York, NY: Springer.

- Shah, C. (2014). Collaborative information seeking. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(2), 215-236.

- Shah, C. (2015). Collaborative information seeking: from 'what?' and 'why?' to 'how?' and 'so what?'. In P. Hansen, C. Shah & C. Klas (Eds.), Collaborative information seeking: best practices, new domains and new thoughts (pp. 3-16). New York, NY: Springer.

- Shavner, S.S. & Tang, R. (2014). Collaborative information seeking (CIS) behavior of LIS students and undergraduate students: an exploratory case study. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 51(1), 1-4 Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/meet.2014.14505101106. Retrieved from (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76D21ax4R)

- Shaw, M.E. (1971). Group dynamics: the psychology of small group behavior. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Sheard, A.G. & Kakabadse, A.P. (2004). A process perspective on leadership and team development. Journal of Management Development, 23(1), 7-106.

- Sonnenwald, D.H., Soderholm, H.M., Welch, G.F., Cairns, B.A., Manning, J.E. & Fuchs, H. (2014). Illuminating collaboration in emergency healthcare situations: paramedic-physician collaboration and 3D telepresence technology. Information Research, 19(2), paper 618. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/19-2/paper618.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76D2FqSho)

- Sonnenwald, D.H., Wildemuth, B.M. & Harmon, G.L. (2001). A research method to investigate information seeking using the concept of information horizons: an example from a study of lower socio-economic students’ information seeking behavior. The New Review of Information Behavior Research, 2,65-85.

- Sparrowe, R.T. (2014). Leadership and social networks: initiating a different dialog. In D.V. Day (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of leadership and organizations (pp. 434-454). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Thomas-Hunt, M.C., Ogden, T.Y. & Neale, M.A. (2003). Who’s really sharing? Effects of social and expert status on knowledge exchange within groups. Management Science, 49(4), 464-477.

- Thomas, E.J., Sexton, J.B. & Helmreich, R.L. (2003). Discrepant attitudes about teamwork among critical care nurses and physicians. Critical Care Medicine, 31(3), 956-959.

- Thompson, J.D. (1967). Organizations in action. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Tortoriello, M., McEvily, B. & Krackhardt, D. (2015). Being a catalyst of innovation: the role of knowledge diversity and network closure. Organization Science, 26(2), 423-438.

- Tuckman, B. & Jensen, M. (1977). Stages of small group development revisited. Group and Organizational Studies, 2(4), 419-427.

- Wasserman, S. & Faust, K. (1994). Social network analysis: methods and applications. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Watts, D.J. (2003). Six degrees: the science of the connected age. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

- Wegner, D.M. (1995). A computer network of model of human transactive memory. Social Cognition, 13(3), 319-339.

- West, E., Barron, D.N., Dowsett, J. & Newton, J.N. (1999). Hierarchies and cliques in social networks of healthcare professionals: implications for the design of dissemination strategies. Social Science & Medicine, 48(5), 633-646.

- Xyrichis, A. & Ream, E. (2008). Teamwork: a concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 61(2), 232-241.