Ethical issues in today's information society from a Spinoza perspective

Natascha Helena Franz Hoppen, Renato Levin-Borges and Moises Rockembach.

Introduction This work aims to discuss some characteristic devices of the information society through Spinoza's Ethics.

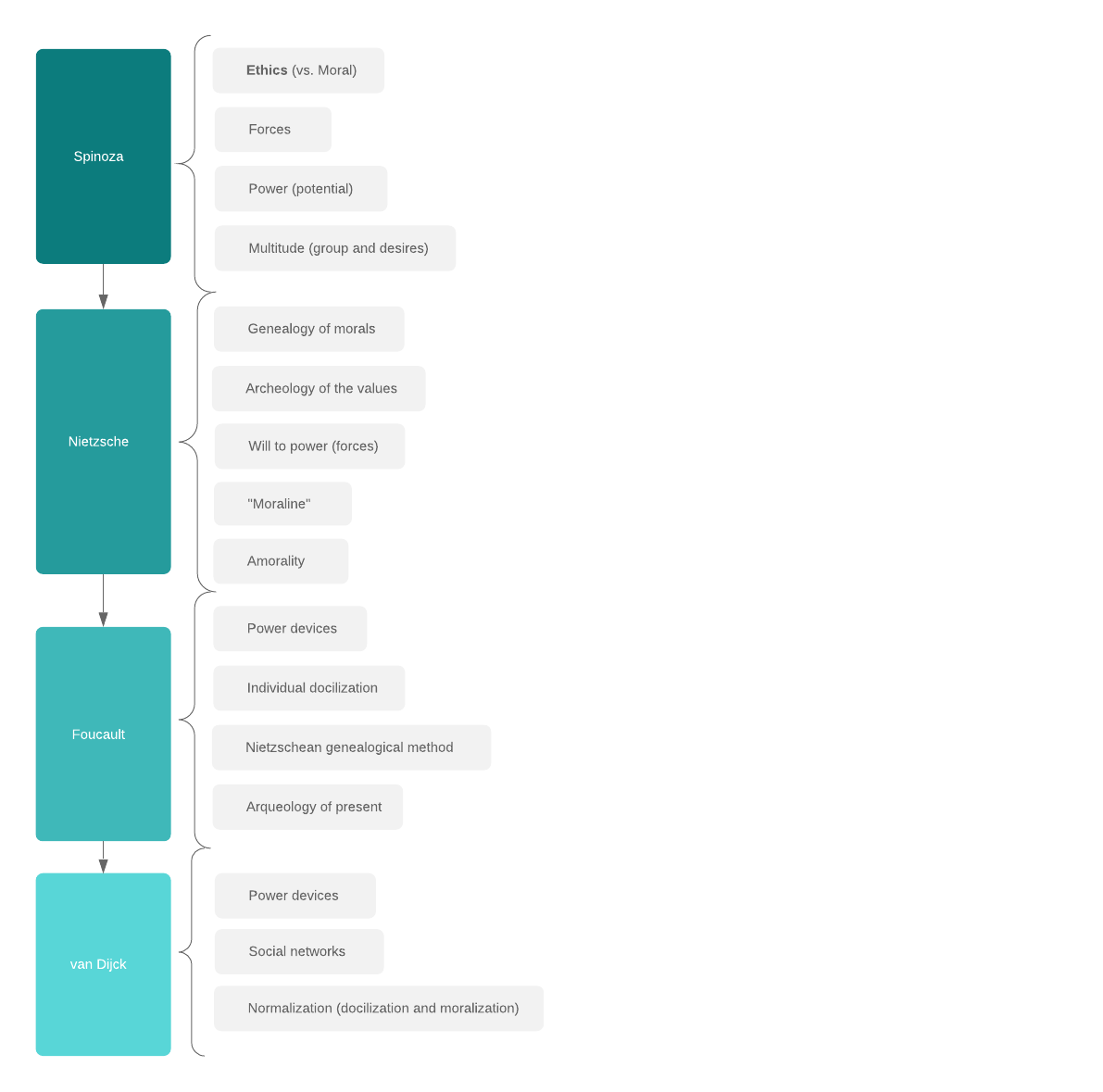

Methods. Qualitative analysis using concepts such as power or potentia, forces, "moraline" power devices, normalisation and other concepts from Spinoza and his followers.

Analysis. We define Spinoza's Ethics as amoral and a posteriori, supported not by moral judgments, but by ethical reflections on increasing and decreasing power (potentia). The paper illustrates ethical issues of the information society and analyses them through Spinoza's philosophy including access to information, welfare and social networks, universal standards of happiness, simulations of stereotypes (real life versus social networks), promoting constant consumption, providing personal data with and without consent, surveillance of citizens by the states under the aegis of biopower and the need for privacy.

Results. Finally, we conclude that Spinoza's Ethics aims to contextualise these phenomena and not evaluate them in advance and, as such, can serve as a basis for discussing the ethical demands of the information society.

Introduction

The objective of this article is to bring the ethical discussion about information to current phenomena, characteristic of the information society, such as surveillance through data and welfare in social networks (universal standards of happiness or simulations of stereotypes). These phenomena will be approached from the ethics of Spinoza, amoral ethics able to properly cover, in a non-dialectical way, issues of a post-modern society punctuated by an information explosion.

Although it is possible to think that ethics is something contemporary when applied to information, the subject began in Ancient Greece with the concept of parrhesia, which can mean freedom of speech or free speech, a key concept in Athenian democracy, but not available to everyone (Capurro, 2006; Foucault, 2008; Levin-Borges, 2016). Because of its restricted availability, an ethical act was required from the speaker, and the act of exercising free speech implied a risk to the speaker's existence. For Capurro (2006) and Fernández-Molina (2009), ethics pertinent to information acquire new and greater relevance at the end of the twentieth century, due to the enormous impact of the development of information and communication technologies, where the production, storage, processing and dissemination of information become more comprehensive, global, democratic and interactive (Fernández-Molina, 2009).

Ethics in Spinoza

Ethics originates from the Greek word ethos, which means way of being, customs and human habits. In classical antiquity, ethics was a central theme for Greek philosophers such as Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. After questioning what the world and its phenomena are, these philosophers reflected on human beings, their values and their customs. While the Greeks were looking for non-normative universal fundaments, Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677) represented a change in ethics. He left behind the tradition that was concerned with general measures and values, guiding human actions towards the creation of personal and communal ethical values. Spinoza proposes a non-normative and non-universal ethics. Contrary to the Western tradition, Spinoza's perspective presents an ethics that is not something pre-established, but an open path ahead, in which each person and community can create and build their own ethics.

Ethics and morality, although related, are distinct concepts in Spinoza. Both can guide human conduct, however, ethics is concerned with creating a way of being and relating to others, while morality refers to customs and habits in society. Morality is a set of rules that must be followed, for example, the set of rules of coexistence in a residential compound, closely linked to socially accepted and prescribed norms. Ethics, on the other hand, is not intended to be universal or prescriptive. While morality may come from common sense, from the socially accepted, but not always be reflected in customs, ethics does not come from pre-established values, and demands intellectual processes and self-experimentation. Therefore, since it is not predictable, ethics emerges and is created from a determined effort to constitute a way of existing (Spinoza, 2017/1677). Understanding the difference between ethics and morality is fundamental for understanding Spinoza's philosophy and how it relates to the information society and its critical points.

Baruch (or Benedictus of) Spinoza was a Dutch philosopher from a Portuguese-Jewish family, who lived from 1632 to 1677. During his life, he published three essays: On the improvement of the understanding (1662), The principles of Cartesian philosophy (1663), and Theologico-political treatise (1670). In 1677, the year of his death, Ethics, demonstrated in the manner of geometers, or simply The ethics (Spinoza, 2017/1677), considered his masterpiece, was published. He postulates that we are composed of affections (in the sense of engagement), that is, degrees of corporeal intensity that can increase our ability to be affected by and affect reality (called joy) or decrease it (called sadness).

Among all the affections that compose us, Spinoza (2017/1677) promulgates knowledge as the most powerful, since, more than any other, it increases our ability to affect and be affected by reality. This means that knowledge, intimately connected to information, is a necessary component for the increase of the power of human beings. Spinoza's expulsion from the Jewish community ("Herem", in Hebrew) was based on postulates in his philosophy concerning free will and God. Spinoza believed in the idea of God as nature, a pantheistic idea of a god that is in all things and that reveals himself in the harmony of nature and not as the personification of a father who judges and challenges human actions. Furthermore, through his conception of determinism, Spinoza eliminates the concept of free will, a device for blaming individuals, which makes individuals believe in religion, making them adopt the morality intrinsic to religions.

These concepts in Spinoza help us think about his Ethics: for Spinoza, God does not exist as a moral judge who watches his creations. Spinoza's god-nature is amoral, necessary and infinite (amoral should not to be confused with immoral. while amoral is non-moral, it is outside the moral question, outside its scope, while immoral is what is contrary to morality. So, an amoral ethics is, in short, an ethics that does not rely on moral standards, but is beyond it (this concept will be discussed along the argument). Therefore, a god who is amoral, necessary and infinite implies he/she/it is not subject to time and does not act as a judge of all things. Everything that happens, happens necessarily; meaning it could not have been in any other way, since everything that exists is a modulation of God and, by his nature, he could not have done better or worse, but everything that exists, exists necessarily.

In the sense of a life without certain precepts and morals considered to be true, Spinoza's Ethics is constructed from contexts and what they propose: increase or decrease of power, a word that is closely related with the word potentia in Spinoza's philosophy. Potentia is a Latin word that means something other than power, because while power denotes an actual and established relation (e.g., State power or the boss's power over workers), potentia is more related to the concentration of forces, either in virtual and/or actual existence, that are not granted a priori, and change according to the relations in a certain time and context. Power, in this way, is a type of relation, a layer of potentia in actual relations. For our proposes, we will use the word power as closely related to potentia, as it is in Spinoza's works. The concept of power in Spinoza's philosophy must be understood as forces containing possibilities and flows, which influenced Nietzsche (1883/2016; 1908/2015), who defined power as the increasing ability to act and be able to affect and to be affected by other forces, people, relations and encounters. What is good and what is bad are not pre-defined concepts, nor do they depend entirely on customs and traditions. According to Spinoza, good is what increases my power and bad is what decreases it (Spinoza, 1677/2017).

These concepts are necessary to understand Spinoza's philosophy, and the concepts in his philosophical cosmos which are relevant to the intentions of the present work are the previously mentioned (1) power (understood as potentia), (2) affect and (3) encounter. Thus, as mentioned before, power in Spinoza's thinking is the ability to act, either physically or intellectually. Thinking, for example, is considered an action of thought, just as running is an action of the body. It is very important to understand the theory of parallelism of mind and body in Spinoza's conception of being, where on the one hand we have the body, and on the other we have the mind: one does not affect the other in any way, otherwise, an affection in the body would have a parallel affection in thought, and a thought would have an affection correlated in the body. To sum up, thinking does not cause affection, nor the contrary; they happen in parallel, as two dimensions of the same thing on the being, e.g., being hungry: I feel a degree of intensity in my body and I have an idea of what I am feeling. ‘By affect I understand states of a body by which its power of acting is increased or lessened, helped or hindered, and also the ideas of these states. Thus, if we can be the adequate cause of any of these states, the affect in question is what I call an action; otherwise it is a passion' (Spinoza, [1677] 2017, p. 51, emphasis added). Affect, as we said before, is a degree of intensity in the body and is related to the affection, which denotes the passage from one state of affect to another. Encounters are mutual affectations that occur necessarily at all times with forces, beings and things, and cause some degree of intensity in our bodies.

Spinoza's Ethics also differentiates between good and bad encounters. As previously mentioned, good is what increases power (potentia) of acting, bad is what decreases it. For example, a good encounter for an individual can be the coffee he or she drinks at breakfast: the forces of the coffee connect themselves with the forces of the body and increase the person's ability to act. A bad encounter can be when the same coffee, drank excessively, causes headaches and agitation. Drinking coffee is an encounter which is defined as good or bad as it increases or decreases the chances of action of the drinker.

The information society

There are many definitions used to refer to the model of society we live in today: network society, information society, knowledge society, global village, post-industrial era and other variants, all denominations used to describe society from the perspective of the Internet and the development of information and communication technologies. Although the definition of each of these terms differs from one another, they all have information as the fundamental basis for social transformations: from economics to different forms of human interaction, information is also fuel to constant and accelerated technological change and development, an input of a society connected to networks (Castells, 2000, 2010; Burch, 2005; Coutinho and Lisbôa, 2011).

The term information society gained prominence during the development of the Internet and the communication and information technologies in the 1990s, powered by Web 1.0. The term was established based on neoliberal intentions (Burch, 2005) as it was used in European Community forums, in G8 meetings (now G7), by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and by the United States government, among other agencies, culminating in its use as a name for the 2003/2005 World Summit.

In this context, the concept information society, as a political and ideological construction, was developed from neoliberal globalization, with the main goal of accelerating the establishment of a world market that would supposedly be open and self-regulated. This policy has been closely coordinated by multilateral organizations such as the World Trade Organization (WTO), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Bank, with the goal of making underdeveloped countries abandon national regulations or protectionist measures that "discourage" external investments; all this with the well-known consequences of intensifying the gaps between rich and poor in the world (Burch, 2005).

In the meantime, the neoliberal idea of globalisation uses the term as one of the elements in a mythical promise of freedom and equality, when in reality it (also) serves as a way to de-protect developing countries in competition between markets. Castells (2000, 2001, 2010) associates what he calls the network society and the Internet with this controversial phenomenon: according to the author, it is a utopia to say that the Internet, by connecting people to networks, will take down global barriers and borders, democratise access to knowledge, and reduce economic gaps between users. For Castells, access does not mean effective use: although access to the network is increasing, it is not absolute, nor does it occur at the same level or in the same way for everyone. In fact, it adds yet another layer of social marginalisation: those who have access to the Web compared to those who have it to a limited extent or not at all, or do not know how to use it effectively; which seems to be a reference to information literacy or information behaviour.

The differentiation between those who have and those who do not have access to the Internet adds an essential division to the already existing sources of inequality and social exclusion, in a complex interaction that seems to increase the disparity between the promise of the Information Age and its bleak reality for many throughout the world. (Castells, 2001).

Access is a prerequisite for reducing the digital divide, but by itself it does not solve the problem. In the information society, the digital divide takes place in the ability to transform information into knowledge and knowledge into power and the capacity to act. According to Castells (2000), these issues are related to the educational and cultural capacity to use the Internet, not only accessing codified knowledge, but knowing how to transform and apply what one learns. It is in these aspects that an individual's social, educational and cultural background can generate barriers.

Although the globalisation discourse about the Internet sells the idea that it will make information more democratic and accessible, what we have been seeing is the growth and dominance of a few services over the Internet. According to Cuthberstone (2017), almost 70% of Internet traffic nowadays is concentrated on Facebook and Google, including their services, i.e., YouTube, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Amazon, more oriented towards e-commerce (Dastin and Dang, 2017). The Internet does not seem to be becoming more democratic and accessible; on the contrary, it looks like it is reproducing the classical capitalist concentration of profit and information in a few hands.

Information as power

Castells (2001) proposes that the difference between access to information and its effective use is a key issue of the specific social exclusion of the information society. Based on Spinoza's (1677/2017) philosophy, it is the difference between information as mere undefined input and information as power. If power means being able to act, to understand and to create (characteristics of being powerful), information as empowerment presupposes information in service of life, with the intent to create possibilities instead of limiting and monetising them.

If we think about information either from the ideal assumption of the information society or from Spinoza's philosophy, information itself can be life-enhancing: it is the basis for knowledge and the product and producer of actions, reflections, acts and becoming. It enables encounters and, consequently, affections. According to Spinoza (1677/2017), knowledge is the most powerful of affections because it makes us more apt to be affected and to affect ourselves and the world around us. In this context, information is precursor to knowledge and therefore necessary to it. In this way, information is the main agent of knowledge, affection and power.

It is necessary, however, not to be deceived by the Enlightenment ideal: first, access to information alone does not produce knowledge and knowledge alone is not empowerment. Second, as Castells (2000) diagnoses, the way products of the information society are used is not necessarily what they were conceived for. In the information society, people are equally producers and users of information, and its uses and appropriations are diverse. In other words, we need to think about the information society using Spinoza's philosophy: access, use, information, knowledge, network and globalisation are not good or bad a priori. One must ponder when there is a good encounter which improves life.

Spinoza understood that knowledge, nourished by information, is a battle between power interests. Foucault (1994; 2008), deeply influenced by power in Nietzsche and his concepts of forces, inherited from Spinoza, went further and noticed the change of the state reason, or governability (the switch from disciplinary to biopower in Nation states around the eighteenth century in Europe), made knowledge become a sign and a possibility for the powers to have a more effective control over people and modulate the position of relations of force. Explaining this intimate relationship between power and knowledge on Foucault's research, Rouse (2005, p. 4) affirms: 'The connection he proposes between power and knowledge is not just a particular institutional use of knowledge as a means to domination. Foucault objects to the very idea of a knowledge or a truth outside of networks of power relations'. With the emergence of neoliberalism, information became privileged raw material of management and monetisation by the powers of state and capitalism.

As an example, when the term information society was consolidated as an unfolding of neoliberal capitalist intentions (which encourage a type of market that potentialises some governments, companies and groups, while doing the opposite to others), information as input from this society did not necessarily create freedom or good encounters for society as a whole. In fact, it is in service of the opposite, by fueling or fomenting standardised and universal ways of existence, as the capitalist system proposes, by prescribing specific ways of life as happy and excluding others, by serving as invaders of privacy, tacitly allowing the surveillance of lives. Therefore, it is necessary to think of Ethics (and not to propose a moralityl) by Spinoza (1677/2017), in this information society. The following are examples of applications.

Ethical issues in the information society: examples of de-potencializers and life-enhancers

For the percentage of the population that has access to the Web, the information society can promote an ethics of the moral existence: universal and standardised in both the order of desire and action, establishing a power hierarchy. For instance: it is common in our contemporary Western society to access the Internet and social networks through personal devices (computers, tablets, cell phones), which are characteristic of the information society. Through personal devices, we can (and indeed do) constantly access social networks, feed them and watch them by becoming spectators and producers of ways of existing and being. As referenced in van Dijck (2013, p. 17), Papachirissi (2010) noticed that 'social media platforms have introduced a space where boundaries between private and public space have become fuzzy, claiming that this imprecision opens up new possibilities for identity formation'. In other words, we do not know exactly where the boundaries are between public and private anymore, and that raises a lot of concerns. The first and simplest concern about ethics in our interconnected culture, which is being sold as more democratic and decentralised, could be the paradoxical question: how can this foster moraliser and standardiser ethics? We start relating to our peers through what they post and what they choose to show us of their lives, valuing what we like and devaluing everything that does not receive our likes and shares. At the same time, we are evaluated and measured by others, companies and state powers, through our images, likes, opinions and interests, which are being stored, sold and used to make us buy certain products and even influence our political and ethical views.

In personal social media posts, achievements, trips, outings with friends, landscapes etc. are much more frequent subjects than failures, polluted scenarios, sick days or loneliness. However, both are part of our lives. The few stories about failure that get posted are, for the most part (if not always) followed by a great story describing how the failure was overcome that can attract likes and shares. Not that this is done consciously; usually, individuals do not intentionally try to impart the idea that their lives are perfect even though most of our regular days are not even close to perfection, but why do people on the Internet want to always seem happy? Is there an invisible generalised competition among Internet users? Dijck (2013, p. 21) thinks the answer is yes, and states that competitivity on the Internet is fomented by neoliberal principles which are already part of our Western standard subjectivities. The point is that these characteristics, so particular to our contemporaneity, have negatively influenced people's well-being. According to studies conducted with Facebook users (Kross, et al., 2013; Happiness Research Institute, 2016; Tromholt, 2016; Shakya and Schristakis, 2017), the illusion that the lives surrounding us are made up only of happy moments and achievements, compared to our lives (and the lives we know and have real access to), makes people more frustrated and disappointed by their own realities. Access to information in social networks fosters an implausible life ideal: happiness and joy every day, all the time, incredible stories of overcoming problems, perfect angles, beauty and satisfaction. It promotes something that Nietzsche, a severe critic of the moral, influenced by Spinoza's distinction between moral and ethics, ironically called moraline (Nietszche, 1883/2016; 1908/2005, p. 4), a tendency to standardise patterns of being. Our contemporary moraline is a morality of an anxious (with poor self-esteem) happiness that demands lots of likes to accomplish its little and inexhaustible everyday goal: a happiness filled with brightness and Instagram filters.

One such story is that of Essena O'Neill, an Australian model and former Instagram celebrity (Instagram is an app for posting pictures with short text descriptions). Essena used to make daily posts with pictures of herse;f in everyday moments in beautiful Australian landscapes, reaching more than 700,000 followers. Her photos were widely liked, which made the model famous to the point of being sponsored by brands that paid her to post photos using their products in her everyday life (or, at least, the life she artificially created with fabricated pictures and landscapes) in her online profile. Nevertheless, in October 2015, Essena deleted more than one thousand photos from her account and rewrote some of the descriptions in others, exposing the real process behind the pictures that were not deleted. In one of the edited posts, in which she poses in a bikini in a sunny beach, Essena wrote:

Not real life. Only reason we went to the beach this morning was to shoot these bikinis because the company paid me and also I looked good to society's current standards. I was born and won the genetic lottery. Why else would I have uploaded this photo? Read between the lines, or ask yourself "why does someone post a photo... What is the outcome for them? To make a change? Look hot? Sell something? I thought I was helping young girls get fit and healthy. But I only realized at 19 that placing any amount of self-worth on your physical form is so limiting! I could have been writing, exploring, playing, anything beautiful and real… Not trying to validate my worth through a bikini shot with no substance #celebrityconstruct (O'Neill, 2015).

In other posts edited after 2015, O'Neill (2015) writes about photos that were taken almost a hundred times, the stress of quarreling with her sister to get the right angle of her body, simulations of spontaneous moments with products that she did not use, starving herself to take pictures wearing bikinis and other simulacres that, according to her, worked for self-promotion, but were not real. Essena's unmasking had repercussions on portals all over the world (Bromwich, 2015; Hume, 2015; López, 2015; Martinelli, 2015; O'Neil, 2015) and there is currently only one picture on her Instagram account, which refers to her new motto: ‘social media is not real life'. Spinoza's question remains: did these kinds of lives, projected perfect lives, potentialise or de-potentialise her (in the sense of loss or decrease of power) and her followers? Building an intangible image of an all-around happy and relaxed life, Essena noticed that her way of being was only good to be monetised, but not to promote her or her followers' happiness – as previously mentioned here, other people's happiness and perfection displayed online tend to make people depressed and sad for not being able to lead a life like that. We could say more using Spinoza's lens, making the case that she was helping to create a sense of self-image, that is promoting knowledge which decreased her power and de-potencialised girls' self-esteem, already bombarded daily with a kind of moral concern with their bodies dictating what every female body should look like.

But the kind of life promoted by social media is not the only thing that can lead to ethical reflections within the information society. We provide, most of us without realizing it, information about our personality, what we do and where we are. As a huge political example, we have the ongoing Cambridge Analytica case on Donald Trump's election in 2016 in which, using data collected from Facebook users, the company – which ironically started as a happiness measurement program and became a political and military information weapon (Shaw, 2018) – made campaign advertisements for Trump based on personal data informed by, among other things, peoples' desires, frustrations, prejudices and opinions. Cambridge Analytica was successful in the use of data and information, not in Spinoza's way, that is, potentialising people's lives, but serving Trump and Republicans' political interests, producing and/or fomenting standardised subjectivities, modulating our subjectivities, according to preconceived patterns of ways of existence (Guattari and Rolnik, 2000).

When we access social media daily, navigate the Web, use applications that serve as routine tools and for which we provide data about our age, sex, location, consumption and affiliations we are feeding databases information about ourselves without realising it. Search engines harvest this data and process it through algorithms to suggest products and services according to our (supposed) personal interests when we make new searches. At first, this is not an issue: I willingly provide such data. However, today we know that the suggestions of products and services are not so innocent, since they generate constant consumption. I do not need X, but since it was suggested to me and it connects to a way of life intrinsically linked to happiness, I unconsciously become interested and end up buying it without really needing it. It stimulates purchases, investing in interests produced from the capture of singularities to form them into a common capitalist pattern: constant consumption. On an individual scale, the impact seems very small. But let us imagine that this is done all day, every day, with every person who uses a search engine as common as Google. The ethical question depends on an illusion of power of action, since capitalist consumption does not have an end, but produces needs and desires that never get satisfied, feeding itself. The consumption is never about the product but the uses of information, including personal data, hooking us in trying to achieve the happiness that is supposedly attached to the object we purchased. Žižek in his article ‘Happiness? No, thanks’; diagnoses: ‘Happiness relies on the subject’s inability or unreadiness to fully confront the consequences of its desire’ (Žižek, 2018). We do not know why we desire the things we desire anymore; there is always a way of being sold in everything we want and capitalism knows how to exploit it. In addition to fostering consumption from the data we provide, the information age also serves to capture and record what we consume as citizens of the state (Lemos, 2017), what music we consume (Agência EFE, 2016), what we talk about on Facebook (Levin-Borges and Ceccim, 2015) and other social media platforms.

Given the large-scale nature of these practices, which represent a reconfiguration of traditional intelligence agencies, the document states that the analysis of European surveillance programs cannot be reduced to a balance between data protection versus national security, but it should be framed in terms of collective liberties and democracy. (Bigo et al., 2013, p. 3).

The ethical question here is very clear: massive, invasive mechanisms of control and subjugation are being produced – to the point where they cannot even be compared to the Big Brother cameras and speakers portrayed in the dystopian work 1984 (Orwell, 2009), using information as their raw material; who are they empowering? In these cases, the information collected and the access to them on the part of the states are instruments of de-potentialisation of existence, since they restrict freedom, powers, lives, propose and invest in standardised subjectivities and desires, weave propositional norms through produced patterns, fed and reinforced by the individuals themselves. Espionage provides subsidies for the most varied power techniques, which lead to greater subjugation and submission of individuals. The possibility of privacy is almost utopian and certain data parameters can even lead to physical sanctions – such as the already practiced arbitrary detention of suspects without proof or evidence of threat to national security, like the Guantánamo prison in Cuba.

According to Jacob Appelbaum, a WikiLeaks contributor: 'What people used to call liberty and freedom, we now call privacy'. (Poitras, Bonnefoy and Wilutzky, 2014). This is because we have data from all areas of our lives being collected, recorded, registered and accessed, whether for commercial purposes or for surveillance purposes. Snowden, another contributor to WikiLeaks, warned of the construction of machines of oppression so sophisticated that no citizen could oppose them. Privacy is necessary and fundamental, and this is another ethical issue relevant to the information society; nowadays, what can we call private, as opposed to public? What are their boundaries? Did the Internet blur them irreversibly?

In the information society, Websites like Facebook may already exert more normalisation, promotion of the docile body, and power over individuals than regular disciplinary institutions such as the law, schools, prisons and factories. Van Dijck (2013, p. 19) outlines the Foucauldian perspective of powers, where the norms are postulated as cultural cement which serves as ground for legal regulations, saying that, 'Social media constitute an arena of public communication where norms are shaped and rules get contested’. Going further, van Dijck states that in social media the social norms and laws surpass the laws of the social plane, where they are, in her words, ‘much more influential’ (Dijck, 2013, p. 19). Developing the idea that the contemporary methods of power follow Foucault’s diagnoses, she recognises a shift of techniques in which the idea of power control no longere operates mainly through laws, but by normalisation, not by punishment, but by endless techniques from agency control devices.

From the moment an individual feels watched and controlled, their power is inhibited. The guarantee of security of environments and the possibility of privacy and confidentiality are necessary for the free exercise of some potentia. Surveillance inhibits experimentation and hinders potentialities, as it exerts a kind of virtual moral eye. It is not a prescriptive morality, but a propositional morality that operates restrictively by denying what is outside of the set standards, which places on the existential horizon the fear of creating or experiencing anything that can be considered contravening – even personal de-medicalisation, as in the case of the virtual community DIU de Cobre, or copper intrauterine device (copper IUD).

Note: The text reads, 'We do not accept couples' profiles – exclusive group for people with a uterus... Read the fixed post and use [tags] in the post'.

The Brazilian Copper IUD (DIU de Cobre in Portuguese) community on Facebook is a great example of the use of Spinoza’s approach to information and the Web for increasing power. It aims to unite people who can share information and personal experiences about the copper IUD. The copper intrauterine device is a contraception method that does not use any artificial hormones for birth control. It is a non-pharmacological, cheap and efficient method of contraception (Grimes, Lopez, Manion and Schulz, 2007; World Health Organization, 2016), but it is not much used and known among the female population of Brazil for many reasons, such as misinformation, religion and the pharmaceutical industry’s interest in widespread use of hormonal contraception – the contraceptive pill (Perpétuo and Wong, 2009). Following the need to reduce unnecessary medical and pharmaceutical interventions on women’s reproductive health – such as ceasarean sections (World Health Organization, 2018) –, the Brazilian Copper IUD community is an almost-safe and secure place where women (and men with a uterus) are able to find information about the method without being bombarded with drug offers (from the pharmaceutical industry) or prejudice.

The Copper IUD community accepts only personal profiles of people with a uterus (which means it is restricted to people who can or need to use an intrauterine device, for instance, women and transexual men). In addition, sharing messages or screen-grabs from within the group is not allowed, which contributes to the privacy of the group and its members. The community has about ten moderators; it is extremely well organized, with fixed topics and tags for posts, with information about the use of a non-hormonal contraceptive method (the copper IUD) reports about insertion of the device (positive and negative), legislation on access to health plans, availability through the Brazilian Unified Health System, health issues related to the female reproductive cycle, etc.

For Castells (2000), the information society through the Internet allows interpersonal relationships in virtual communities based on personal interests and affinities, but without the physical limitations that, in physical groups, would make this type of relationship difficult. Virtual communities are plans of connection driven by desires and shared affections. In Spinoza’s ethical key, they can be the search for good encounters, where information operates as a force to potencialise individuals’ lives beyond the capitalist logic of knowledge growth only through monetary transactions. These virtual communities have another advantage: they do not require physical meetings between the subjects who interact with each other, which allows for the constitution of big networks, including a range of people who otherwise could not participate in certain types of discussions and access some of the information freely shared in these virtual spaces.

In this sense, the opportunity to be part of a community with people with the same interests, and yet, a community in which there is some level of privacy, results in a possible ethical process, thanks to the characteristics of the information society. As it is something intimate (but as constantly studied as female sexuality and reproductive cycles, including conception and contraception), it cannot be talked about openly (at least not all the time). This community is a clear example of the need for privacy in the information society and which, when endowed with this characteristic, becomes an example of the scope of the information society in another ethical bias: the potentiator. Access to information in this community opens new avenues and possibilities for women who have been taking medication (artificial hormones as contraceptives) since their first menarche, as if the menstrual cycle was an illness, which it is not.

Here, we see a possibility of using Spinoza’s (1677/2017) perspective to deal with this potentia of what information made more democratic and serving peoples’ lives can do. As it is known, the pharmaceutical industry has never been interested in health measures that do not increase medicalisation. To give us an idea of the pharmaceutical industry interests, including, of course, the general medicalisation of the population, a report led by Chris McGreal (2017) points to more than US$ 2.5 billion put into lobbying and funding members of the USA congress over the past decade. It exerts pressure on health workers, even when they do not receive financial advantages from laboratories (as is very common for Brazilian physicians). The official science and standard health procedures prescribe hormonal contraceptives for healthy women, reducing their general well-being and decreasing their knowledge and power. In other words, there are obvious power relations that make very few gynecologists even mention the existence and possibility of the copper intrauterine device as a drug-free method for women to avoid getting pregnant.

On the other hand, we have information that could lead to less medicalised lives for women and even cut cervical cancer by a third, if it could be shared freely (Cortessis, et al., 2017). More than that, a preconceived and artificial notion of happiness is used as a hook and plays a big part in the medicalisation of women’s bodies, because it has been advertised over decades that oral contraceptives help with depression. This becomes more clear if we consider happiness as Spinoza’s (1677/2017, p. 116) definition of this concept in his Ethics, which necessarily involves the sharing of information, which becomes knowledge to create a real power increase, characterising happiness: 'So it is especially useful in life for us to perfect our intellect = reason as much as we can; and men’s highest happiness consists in just this'. Nevertheless, studies affirm that hormonal contraceptives can reduce general well-being in women’s health and are no better than placebos in treating depression (Cullberg, 1972; Skovlund, Mørch, Kessing and Lidegaard, 2016; Zethraeus, et al., 2017). One of the most recent studies was conducted following the double-blind methodology, which means that neither the researchers giving out the pills nor the women taking them knew who was getting the placebo or the contraceptive pill (Zethraeus, et al., 2017). It concluded that women who took the contraceptive pills had decreased their life quality compared with those who took placebos.

That proves we are not dealing with neutral information accessible to everyone with the goal of making peoples’ lives better. We are dealing with a lot of power Webs in the information society, and a different way to deal with information is needed. Maybe the problem of power understood as potentia in Spinoza’s Ethics can help us to think of different ways to handle and promote information.

Final considerations

The information society and its characteristics, relevant to the development of communication and information technologies, the Internet as a global network, information explosion, reconfiguration of interpersonal and institutional relations of a networked society, capitalist desires and consumption etc., cross ethical questions. This article proposed considering them beyond a monetarising and moralising ethics, which defines what is bad or good or what is accepted or rejected. The complexity of the postmodern information society does not allow dialectical reflections like these. On the other hand, Benedictus de Spinoza's Ethics allows one to think of these dilemmas in this context and to the extent that they enable or inhibit life powers, changing the perspective of how information is preconceived by some power centres that project which are the ones people need and how to allow and promote the information and knowledge that people demand and need for their different and multiple interests.

Access to information, the well-being of people and how it is affected and shaped by social networks, capitalistic and universalising standards of happiness, simulations of stereotypes (and the complex interaction between real life versus social networks), the promotion of constant consumption, the provision of personal data with and without consent, the monitoring of citizens by the states under the aegis of biopower, and the need for privacy and confidentiality are phenomena that illustrate ethical issues that require an amoral ethics. We propose moving the issue of freedom and privacy in the access and use of information from the sphere of legal right to the existential criterion of what increases or decreases powers to exist and what allows the creation of other ways of being that are not preconceived, guaranteed and invested unceasingly over our desires by those in power positions.

In this sense, the possibility of being part of a community with people who share the same interests and, at the same time, a community where there is protection of privacy, we obtain a possible ethical process thanks to the characteristics of the information society. The intra-uterine device community is a clear example of the need for privacy in the information society. As it is, it becomes an example of the scope of the information society from a different ethical view: the potentiator. It potentialises lives (increases power and possibilities of action) through sharing information, in a community without the limits of borders and without, in some sense, the virtual eye of morality that would probably exist if it was not private.

More than this, as argued above, information, its circulation and uses, is a power battlefield and puts us in an ethical conundrum: who is the information serving? What ways of life are being promoted? Is the information circulation making knowledge more democratised, or is it being monetised and concentrated following capitalistic reason? If Spinoza's work on ethics fulfills the information society's potential for making knowledge truly accessible to everyone and consequently improving people's lives, the world community's potentia would increase.

About the authors

Natascha Helena Franz Hoppen is a librarian at the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil, and a Ph.D. student at the same university. Her research interests include ethics, scientific information, scientific and scholar communication, scientific production, and bibliometrics. She can be contacted at na.hoppen@hotmail.com

Renato Levin-Borges is a Philosophy Teacher in Porto Alegre municipality and Ph.D. student in Education at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil. His researches interests are in the field of subjectivation through social media and relations mediated by Internet. He can be contacted at renato_levinborges@yahoo.com.br

Moisés Rockembach is Adjunct Professor in Information Science, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil. He received his Ph.D. from University of Porto (Portugal) and his research interests are in Web archiving, digital preservation and digital ethics. He can be contacted at moises.rockembach@gmail.com

References

- Agência EFE (2016). O que as músicas que você escuta revelam ao Spotify? [What songs do you listen to through Spotify]. G1. Tecnologia e Games. Retrieved from http://g1.globo.com/tecnologia/noticia/2016/08/o-que-musicas-que-voce-escuta-revelam-ao-spotify.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76x0gxbuQ).

- Bigo, D., Carrera, S., Hernanz, N., Jeandesboz, J., Parkin, J., Ragazzi, F. & Scherrer, A. (2013). Mass surveillance of personal data by EU member states and its compatibility with EU law. Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies. (CEPS Papers in Liberty and Security in Europe, 62). Retrieved from https://www.ceps.eu/publications/mass-surveillance-personal-data-eu-member-states-and-its-compatibility-eu-law (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76xtpJleh)

- Bromwich, J. (2015, November 3). Essena O'Neill, Instagram star, recaptions her life. New York Times, Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/04/fashion/essena-oneill-instagram-star-recaptions-her-life.html. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76xu2Oi8N)

- Burch, S. (2005). Sociedade da informação/Sociedade do conhecimento [Information society/knowledge society]. In A. Ambrosi, V. Peugeot and D. Pimienta (Eds.). Desafios de palavras: enfoques multiculturais sobre as sociedades da informação. Caen, France: C & F Éditions. Retrieved drom: https://dcc.ufrj.br/~jonathan/compsoc/Sally%20Burch.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/778TZdVNV)

- Capurro, R. (2006). Towards an ontological foundation of information ethics. Ethics and Information Technology, 8(4), 175-186.

- Castells, M. (2000). Internet y la sociedad red. [Internet and the network society]. Retrieved from http://red.pucp.edu.pe/wp-content/uploads/biblioteca/Castells_Internet.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76xr0e9JV)

- Castells, M. (2001). The Internet galaxy: reflections on the Internet, business and society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Castells, M. (2010). The rise of the network society: the information age (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Cortessis, V. K., Barrett, M., Brown Wade, N., Enebish, T., Perrigo, J. L., Tobin, J.,… McKean-Cowdin, R. (2017). Intrauterine device use and cervical cancer risk. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 130(6), 1226-1236.

- Coutinho, C. & Lisbôa, E. (2011). Sociedade da informação, do conhecimento e da aprendizagem: desafios para educação no século XXI. [Society of information, knowledge and learning: challenges for education in the 21st century]. Revista de Educação, 18(1), 5-22.

- Cullberg, J. (1972). Mood changes and menstrual symptoms with different gestagen/estrogen combinations: a double blind comparison with a placebo. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum, 236(1), 1-86.

- Cuthbertson, A. (2017, February 2). Who controls the Internet? Facebook and Google dominance could cause the 'death of the Web'. Newsweek.com. Retrieved from http://www.newsweek.com/facebook-google-Internet-traffic-net-neutrality-monopoly-699286 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76wzSKaIt)

- Dastin, J. & Dang, S. (2017, April 27). Amazon ad sale boom could challenge Google-Facebook dominance. Reuters.com. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amazon-com-ads/amazon-ad-sale-boom-could-challenge-google-facebook-dominance-idUSKBN1HY1GI (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76wzfqP8i)

- Dijck, José van (2013). The culture of connectivity: a critical history of social media. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fernández-Molina, J. C. (2009). La información en el entorno digital: principales áreas con implicaciones éticas. [Information in the digital environment: main areas with ethical implications.]. In H. F. Gomes, A. M. Bottentuit, and M. O. E. Oliveira. (Org.). A ética na sociedade, na área da informação e da atuação profissional: o olhar da Filosofia, da Sociologia, da Ciência da Informação e do exercício profissional do bibliotecário no Brasil (pp. 65-93). Brasília: Conselho Federal de Biblioteconomia.

- Foucault, M. (1994). Histoire de la sexualité. I: la volonté de savoir. [History of sexuality. I: the will to know]. Paris: Gallimard.

- Foucault, M. (2008). Le gouvernement de soi et des autres. [Self-government and others]. Paris: Gallimard.

- Guattari, F. and Rolnik, S. (2000). Micropolítica: cartografias do desejo. (6th ed.). [Micropolitics: cartography of desire]. Petrópolis, Brazil: Vozes.

- Grimes, D. A., Lopez, L. M., Manion, C. & Schulz, K. F. (2007). Cochrane systematic reviews of IUD trials: lessons learned. Contraception, 75(6 Suppl.), S55–S59.

- Happiness Research Institute. (2016). The Facebook experiment: does social media affect the quality of our lives? Retrieved from https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/928487_680fc12644c8428eb728cde7d61b13e7.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76wzoAlFy)

- Hume, K. (2015, November 22). It's time to get honest on Instagram. News.com.au. Retrieved from http://www.news.com.au/news/its-time-to-get-honest-on-instagram/news-story/5ffdbd61709cb0c887d42947cc4518e6 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76wzw9UKK)

- Kross, E.,Verduyn, P., Demiralp, E., Park, J., Lee, D. S., Lin, N., Shablack, H., Jonides, J. & Ybarra, O. (2013). Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS ONE, 8(8), e69841.

- Lemos, R. (2017, January 2). Estados desprezam privacidade de contribuintes. [States disregard taxpayer privacy]. Folha de São Paulo. Retrieved from http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/colunas/ronaldolemos/2017/01/1846243-estados-desprezam-privacidade-de-contribuintes.shtml (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76x0y2L4d)

- Levin-Borges, R. (2016). A grande saúde peregrina: vidas que constituem o jornal Boca de Rua [The great health pilgrimage: lives that constitute the newspaper, Boca de Rua]. (Unpublished Master's dissertatoin). Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10183/147936 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76xuDRLqZ)

- Levin-Borges, R. & Ceccim, R. B. (2015). O Facebook como confessionário: discursos sobre si e o investimento dos poderes. [Facebook as a confessional: discourse about yourself and the investment of powers]. Saúde em Redes, 1(2), 57-67.

- López, M. R. (2015, November 4). Essena O'Neill: celebridade do Instagram abandona rede social e revela sua fraude. [Essena O'Neill: Instagram celebrity abandons social network and reveals its fraud]. El País.com. Retrieved from https://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2015/11/03/estilo/1446547570_629565.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76x1LxRFU)

- McGreal, C. (2017, October 19). How big pharmas money – and its politicians – feed the US opioid crisis. The Guardian.com. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/oct/19/big-pharma-money-lobbying-us-opioid-crisis (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76x1cb5cd)

- Martinelli, A. (2015). Ela cansou de ser famosa no Instagram e desmascarou a ideia de "vida perfeita" na rede social. [She tired of being famous on Instagram and unmasked the idea of "perfect life" in the social network]. HuffPost Brasil.com. Retrieved from http://www.huffpostbrasil.com/2015/11/03/ela-cansou-de-ser-famosa-no-instagram-e-desmascarou-a-ideia-de_a_21695901/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76x1m3WmX)

- Nietzsche, F. (2005/1908). Ecce homo: how one becomes what one is. London: Penguin.

- Nietzsche, F. (2016/1883). Thus spoke Zarathustra. New York, NY: Jester House Publishing.

- Nisti, M. (Producer) & Renner, E (Director). (2008). Criança, a alma do negócio. [Child, the soul of business]. [Documentary]. Retrieved from http://www.videocamp.com/pt/movies/crianca-a-alma-do-negocio (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76x2gAfXJ)

- O'Neill, E. (2015). Essena O'Neill [Instagram]. Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/essenaoneill (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76x3C64j3)

- O'Neil, L (2015, November 3). Teen Instagram star Essena O'Neill hailed as a "revolutionary" for quitting social media. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/trending/instagram-essena-o-neill-social-media-isn-t-real-1.3302045 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76x31bN97)

- Orwell, G. (2009/1949). 1984. New York, NY: New American Library.

- Papachirissi, Z. (2010). A private sphere: democracy in a digital age. Cambridge: Polity.

- Perpétuo, I. H. O. & Wong, L. L. R. (2009). Desigualdade socioeconômica na utilização de métodos anticoncepcionais no Brasil: uma análise comparativa com base nas PNDS 1996 e 2006. [Socioeconomic inequality in the use of contraceptive methods in Brazil: a comparative analysis based on the 1996 and 2006 PNDS (National Demographic and Health Survey)]. In Brasil. Ministério da Saúde (Ed.), Pesquisa nacional de demografia e saúde da criança e da mulher PNDS 2006: dimensões do processo reprodutivo e da saúde da criança (pp. 87–104). Brasília: Ministério da Saúde.

- Poitras, L., Bonnefoy, M. & Wilutzky, M. D. (Producers). (2014). Citizenfour [Documentary]. Retrieved from https://citizenfourfilm.com/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76x3LgjaN)

- Rouse, J. (2005). Power/knowledge. In: G. Gutting (Ed.). The Cambridge companion to Foucault (2nd ed.) (pp. 95-122). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Shakya, H. B. & Christakis, N. A. (2017). Association of Facebook use with compromised well-being: a longitudinal study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 185(3), 203-211

- Shaw, T. (2018, March 21). The new military-industrial complex of big data psy-ops. NYR Daily. Retrieved from http://www.nybooks.com/daily/2018/03/21/the-digital-military-industrial-complex/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76x3VdTD5)

- Spinoza, B. (2017/1677). Ethics. Los Angeles, CA: Moonrise Press.

- Skovlund, C. W. ;,Mørch, L. S., Kessing, L. V. & Lidegaard, Ø. (2016). Association of hormonal contraception with depression. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(11), 1154-1162.

- Tromholt, M. (2016). The Facebook experiment: quitting Facebook leads to higher levels of well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(11), 661-666.

- Viana, N. & Assange, J. (2015, July 4). EUA espionaram ministros de Dilma e o avião presidencial. [US spies on Dilma ministers and the presidential plane]. Carta Capital.com [This appears to have been removed from the Carta Capital Website. The same information appears here https://wikileaks.org/nsa-brazil/press.es.html].

- Wikileaks. (2015). Bugging Brazil. 2015. Retrieved from https://wikileaks.org/nsa-brazil/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76x3nFxNK)

- World Health Organization. (2016). Selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use (3rd ed.). Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press.

- World Health Organization. (2018). WHO recommendations: intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press.

- Zethraeus, N., Dreber, A., Ranehill, E., Blomberg, L., Labrie, F., Schoultz, B., Johannesson, M. & Hirschberg, A. L. (2017). A first choice combined oral contraceptive influences general well-being in healthy women – a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Fertility and Sterility, 707(5), 1238-1245.

- Žižek, S. (2018, April 2). Happiness? No, thanks! The Philosophical Salon.com. Retrieved from https://thephilosophicalsalon.com/happiness-no-thanks/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.Webcitation.org/76x3v9aab)