The consequences of online information overload confusion in tourism

Wee-Kheng Tan and Ping-Chen Kuo

Introduction. This study considers the often neglected impact of confusion arising from information overload in the tourism context.

Method. A questionnaire was used to gather data from visitors who had visited Hualien, a well-known Taiwanese tourist destination, and had used online websites to look for information regarding Hualien. The survey respondents were classified based on their number of visits to Hualien: first-timers (have made one visit) and repeaters (have visited more than once).

Analysis. Hypotheses were tested using partial least squares (PLS). The PLS Multi-group Analysis was then applied to compare each of the path coefficients of the two groups of visitors (first-timers and repeaters) to identify the paths that significantly differ across these two groups of visitors.

Results. Overload confusion adds to the undesirable outcome of regret and undermines the desirable outcome of the escape experience.

Conclusion. This study provides the empirical link between overload confusion and two tourism-related concepts that are not adequately explored: destination image and escape experience. The paper also adds to the literature of information science by providing evidence of the applicability of the concept of information overload to the tourism context and its negative effect, also prevalent in some commonly discussed tourism-related concepts.

Introduction

The dramatic proliferation of destination-related information on the Internet has had a deep impact on tourists’ pre-trip behaviour. The large volume and easy accessibility of information allows tourists to plan an itinerary before the trip. However, the vast information also causes difficulties by making tourists feel overwhelmed and confused.

Confusion arising from information overload (Shang, Chen and Chen, 2013) during information search is relevant in the tourism context. Since tourism products are often experience goods with many crucial decisions being made before the trip (Kang, Cheon and Shin, 2011), trip planning is often filled with uncertainty (Jeng and Fesenmaier, 2002). Hence, tourists often conduct an intensive information search in the overly information-rich online environment before a trip. However, previous research has shown that the 'confusion issue might even be more salient in the online tourism context. This issue, however, has not received much research attention in the tourism literature' (Lu, Gursoy and Lu, 2016, p. 77).

Although this area has started to receive some attention from researchers (Lu, Gursoy and Lu, 2016), a deeper understanding of overload confusion in the tourism context is still needed. A cognitive psychological phenomenon (Sproles and Kendall, 1986), overload confusion is 'a lack of understanding caused by the consumer being confronted with an overly information rich environment that cannot be processed in the time available to fully understand, and be confident in, the purchase environment' (Mitchell, Walsh and Yamin, 2005, p. 143). From the information science perspective, it can be viewed as one of the negative effects of information overload. The presence of overload confusion could start a chain of negative events. Overload confusion is known to affect aspects of tourists’ behaviour, such as regret and satisfaction (Desmeules, 2002; Matzler, Stieger and Füller, 2011; Schwartz, et al., 2002; Walsh and Mitchell, 2010).

Regret, a negative, cognitively-based emotion (Zeelenberg, 1999), can negatively influence post-decision attitudes (Tseng, 2017), such as by undermining satisfaction (Bui, Krishen and Bates, 2011). Regret also has a potential effect on tourists’ experience and is therefore important, since tourists’ decisions to purchase tourism products often hinges 'on a mere promise, a notion, and a socially constructed image of what constitutes an interesting or appealing experience' (Curtin 2005, p. 2). Even though holidays are frequently considered 'occasions of escape and liminal leisure' (Voase, 2018, p. 384), the way overload confusion felt by tourists affects their escape experience has often been ignored. Furthermore, destination image is widely examined in tourism research (King, Chen and Funk, 2015). However, the way overload confusion affects tourists’ perception of the destination remains uncertain.

A tourist destination often depends on domestic visitors for survival. Studies have often shown that domestic tourists are more likely than foreign tourists to make repeat visits, and tourists who repeatedly visit a destination can be engaged at a lower cost than new visitors, which is useful to destination marketing organisations (Zhang, Fu, Cai and Lu, 2014). However, these return tourists behave differently from first-time tourists in various aspects, such as the perceived level of confusion (Mitchell, et al., 2005), use of information sources (Baloglu, 2001), experience felt (Yuksel, 2001), destination image (Fakeye and Crompton, 1991), and satisfaction (Lim, Kim and Lee, 2016).

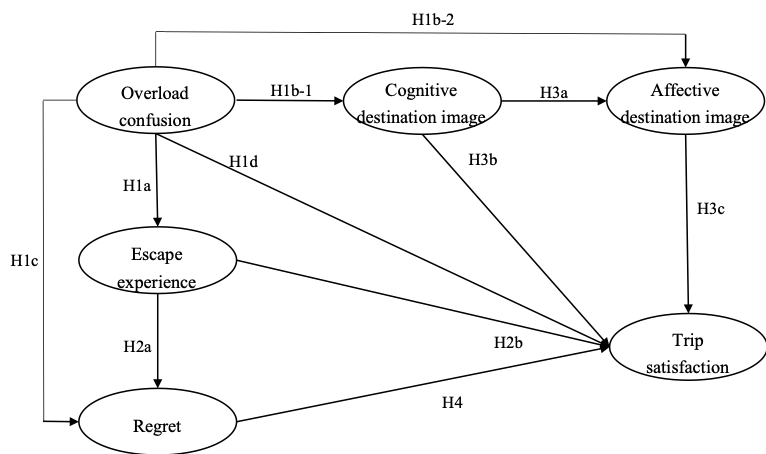

Given that the nature of the links between tourists’ confusion arising from information overload; their regret over choosing some attractions over others whilst touring the destination; escape experience arising from the trip; destination image and trip satisfaction; and how the tourists’ number of visits moderates these relationships is yet to be fully understood, this study suggests the following research question and research model (Figure 1).

Research question: In the tourism context, how does overload confusion arising from information overload affect destination visitors’ escape experience, regret over choosing the destination, destination image and, ultimately, overall trip satisfaction? In addition, how does the impact of overload confusion differ among first-time and repeat visitors?

Thus, this paper attempts to contribute to the understudied aspect of examining the outcomes of overload confusion arising from information overload in the tourism context. This study examines the relationship between information overload and some commonly discussed tourism related concepts. The study also adds to the literature of information science by providing evidence of the applicability of the concept of information overload beyond areas such as health information (Swar, Hameed and Reychav, 2017) and organisation related activities (Eppler and Mengis, 2004) to tourism. The study also has practical implications for destination marketing organisations, as well as entities and individuals involved in authoring, providing, and/or using information about destinations. For example, since information overload arises from excessive information provision, and providing and monitoring destination information is an important function of the destination marketing organisations, these organisations must be concerned with the implications arising from overload confusion. Many bloggers are also in the business of writing about tourist destinations. They will also be interested to learn how information overload and the accompanying overload confusion affects their readers and, hence, the receptiveness of the readers to the blog articles.

The research question and model are examined through the residents of Taiwan (i.e., domestic visitors) visiting Hualien, a favourite nature and rural tourist destination in picturesque eastern Taiwan. Hualien offers a wide range of attractions, such as the Taroko Gorge National Park, East Rift Valley, river rafting, hot springs, whale sighting, and Li-Chuan Aquafarm. Hualien’s distance from major urban centres (which are where most of its visitors come from) and its many attractions provide tourists with the opportunity to escape the hectic and usual urban lifestyle whilst touring Hualien. Given the popularity of Hualien, there is plenty of online destination information. Hence, information overload and its associated confusion are likely.

Literature review and development of hypotheses

Information overload

Whilst information overload is not a new concept (Bawden, Holtham and Courtney, 1999), it has become prominent and is widely researched because of the popularity of the Internet (Jackson and Farzaneh, 2012). The most well known of information pathologies (Bawden and Robinson, 2009), information overload commonly conveys the idea of receiving too much information (Eppler and Mengis, 2004). However, there is no single agreed definition for information overload (Bawden and Robinson, 2009; Jackson and Farzaneh, 2012). Bawden and Robinson (2009) have mentioned that information overload occurs 'when information received becomes a hindrance rather than a help when the information is potentially useful' (p. 249). Eppler (2015) suggests that information overload 'describes situations in which we receive too much information to sensibly deal with it all in our available time frame' (p. 217).

Eppler and Mengis (2004) have suggested five categories that cause information overload, i.e., personal factors, information characteristics, task and process parameters, organisational design, and information technology. The symptoms and negative effects of information overload have also been considered. Swar, et al. (2017) found that perceived information overload negatively influences the psychological well-being of online health information seekers. Limited information search and retrieval strategies, arbitrary information analysis and organisation, suboptimal decisions, and strenuous personal states such as confusion and demotivation are considered symptoms of information overload by Eppler and Mengis. Feelings of stress, ineffective information processing and confusion are also considered outcomes of information overload by Eppler (2015) and Thorson, Reeves and Schleuder (1985). Thus, from the information science perspective, confusion is often considered a symptom or result of information overload.

Overload confusion and its consequences

Consumer confusion is ‘consumer failure to develop a correct interpretation of various facets of a product/service, during the information processing procedure’ (Turnbull, Leek and Ying, 2000, p. 145) and consumers noticing that information processing could be confusing (Walsh, Hennig-Thurau and Mitchell, 2007). Researchers have identified three forms of confusion: similarity, ambiguity, and overload confusion (Lu, Gursoy and Lu, 2016).

Tracing back to brand confusion (Wang and Shukla, 2013), similarity confusion arises from consumers perceiving a similarity of products or services in aspects such as name, colour, size, packaging, and imitators (Matzler, et al., 2011; Wang and Shukla, 2013). Originating from decision sciences (Wang and Shukla, 2013), information that is complex, unclear, and confusing can contribute to ambiguity confusion (Lu, et al., 2016; Matzler, et al., 2011).

Arising from an overly information rich environment where consumers do not have time to process the information (Mitchell, et al., 2005; Moon, Costello and Koo, 2017), overload confusion is thus a negative outcome of information overload when viewed from the information science perspective. Information overload (Feng and Agosto, 2017) and its associated reaction of confusion have been examined in many contexts, such as food labelling (Kangun and Polonsky, 1995), telecommunications (Turnbull, et al., 2000), and online tourism (Lu, et al., 2016). Overload confusion also exists on the Internet (Lu, et al., 2016) and is a consequence of the breakneck growth of websites and consumers being overwhelmed by the vast quantity of information. Although consumer confusion ‘has not received much research attention in the tourism literature’ (Lu, et al., 2016, p. 77), it is prevalent in the online tourism context. For example, Lu, et al. investigated the antecedents and outcomes of consumer confusion in the online tourism context and found that price consciousness and the need for cognition negatively affected overload confusion. This overload confusion resulted in consumers obtaining more information and using familiar information sources.

Nevertheless, more studies are needed in the tourism context, since confusion can have a detrimental effect on many aspects of tourists’ behaviour, such as satisfaction, regret, word-of-mouth, and decision postponement (Desmeules, 2002; Matzler, et al., 2011; Schwartz, et al., 2002; Walsh, et al., 2007). This study chooses to focus on overload confusion because overload confusion has been more frequently mentioned in the literature on consumer confusion than the other two types of confusion. In addition, interviewed individuals who used online information to plan their earlier trips to Hualien consistently mentioned their concern about the massive amount of available information, but mentioned less frequently their similarity and ambiguity confusion.

Escape is often a motivational factor which pushes an individual to travel (Bi and Lehto, 2018; Dickinson, Hibbert and Filimonau, 2016). Escape experience is also one of the four experience dimensions (Pine and Gilmore, 1999). Escape experience involves immersion in the destination experience and a sense of escaping from the individual’s normal routine (Lee, Lee and Ham, 2014). Escape experience also includes tourists distancing ‘themselves from the daily routines, no matter what the daily routines are, where they head, and what they do’ (Oh, Fiore and Jeoung, 2007, p. 122). The other three types of experience are aesthetic experience, whereby tourists appreciate being in the destination environment; educational experience, which involves tourists increasing their knowledge; and entertainment experience (Oh, et al., 2007).

Each experience dimension is unique (Oh, et al., 2007), and not every dimension has to be present and accounted for simultaneously. For example, Lee, et al. (2014) do not consider aesthetic experience. Given that the nature and rural based Hualien provides an excellent environment for visitors to be temporarily removed from the urban and hectic environment they come from, this study considers specifically the escape experience. Few studies have considered the effect of overload confusion on tourist experience. This study suggests that the overload confusion during information processing could undermine a tourist’s escape experience during a trip. Thus:

H1a: Overload confusion influences escape experience.

This study further postulates that overload confusion can affect destination image, which is ‘the sum of beliefs, ideas, and impressions that a person has of a destination’ (Crompton, 1979, p. 18). The image is often considered to be a combination of offerings and attributes (Kim, 2014). Some attributes are cognitive in nature and involve an individual’s perceptions of and attitudes about a place (Martin and Bosque, 2008). Other attributes are affective and involve emotions evoked in the tourists, such as relaxing, pleasant, exciting, and rousing (Martin and Bosque, 2008). The cognitive and affective components can be considered independently (Baloglu and Brinberg, 1997), but the presence of both elements ‘may explain in a better way the image a tourist has of a place’ (Martin and Bosque, 2008, p. 264).

Past studies have shown that individuals create a destination image through different information sources (Greaves and Skinner, 2010). Baloglu and McCleary (1999) suggested that such sources affect how tourists evaluate the cognitive component of a destination. However, external information has a weaker influence on the affective component (Li, Pan, Zhang and Smith, 2009). Nonetheless, few studies have considered the effect of overload confusion on destination image; therefore, in response to the previous studies’ findings, this study suggests the following:

H1b-1: Overload confusion influences the cognitive destination image.

H1b-2: Overload confusion influences the affective destination image.

Regret is what ‘people experience when they realise or imagine that their present situation or condition would have been better if they had acted differently’ (Kaur, Dhir, Chen and Rajala, 2016). It occurs when one feels responsible for negative events (Zeelenberg, van Dijk, Manstead and van der Pligt, 2000) and ‘is not experienced if the consumer feels that he/she can alter the current outcome, for example, if the consumer purchases a warranty on a product’ (Krishen, Bui and Peter, 2010, p. 175). Hence, regret has a strong tendency of self-blame (Zeelenberg and Pieters, 2007) and can be frustrating (Kahneman and Tversky, 1982).

There are multiple consequences attached to regret. In addition to making individuals feel worse off (Schwartz, et al., 2002), regret also lowers an individual’s confidence in the choice they have made (Desmeules, 2002; Matzler, et al., 2011; Walsh, et al., 2007).

Since tourists often actively search for information during trip planning and reflect on the events and success of the trip, overload confusion may make tourists feel a sense of regret. This is especially so in the tourism context, since many outcomes cannot be altered and are intensely felt by tourists, especially after much effort, time, money, and anticipation have been expended for a memorable holiday experience. Hence regret, if present, should be felt strongly by tourists. Furthermore, while most literature argues for the usefulness of an information search before a purchase, there is an alternative view whereby, if viewed from the angle of regret literature, ‘external search processes may also have the unintended consequence of contributing to regret’ (Keaveney, Huber and Herrmann, 2007, p. 1028). Thus, this study postulates that tourists’ overload confusion arising from information search could contribute to their regret over choosing some attractions over others whilst touring the destination:

H1c: Overload confusion influences regret.

Past studies have shown that a lack of understanding arising from overload confusion can lead individuals to feel anxious, frustrated, and dissatisfied (Matzler, et al., 2011; Walsh and Mitchell, 2010). However, Keaveney, et al. (2007) have shown that information search does not affect satisfaction. Thus:

H1d: Overload confusion influences trip satisfaction.

Escape experience and its consequences

Since escape experience is often longed for by tourists (Bi and Lehto, 2018), it is reasonable to assume that it could affect the level of regret felt by tourists. Past studies often suggest that tourist experience positively influences satisfaction (Lee, et al., 2014; Oh, et al., 2007). The following hypotheses are thus postulated:

H2a: Escape experience influences regret.

H2b: Escape experience influences trip satisfaction.

Destination image and its consequences

Whilst some studies indicate that the destination image cognitive dimension influences the affective dimension (Chen and Phou, 2013; Papadimitriou, Kaplanidou and Apostolopoulou, 2018), it is also possible that ‘destination image is simultaneously formed with cognitive and affective components, instead of being a mere result of causality’ (Kim and Chen, 2016, p. 2). Given the conflicting results, further investigation is needed regarding how cognitive and affective destination images are related. Destination image also influences behaviour such as satisfaction (Kim, Hallab and Kim, 2012; Laing, Wheeler, Reeves and Frost, 2014). Thus:

H3a: Cognitive destination image influences affective destination image.

H3b: Cognitive destination image influences trip satisfaction.

H3c: Affective destination image influences trip satisfaction.

Regret and its consequences

Past studies have illustrated that regret negatively influences post-decision attitudes (Tseng, 2017) and repurchase intent (Chang, Gao and Zhu, 2015) and leads to dissatisfaction (Tsiros and Mittal, 2000). Bui, et al. (2011) also found that regret lowers the level of satisfaction and increases negative emotion. Thus, the following hypothesis is suggested:

H4: Regret influences trip satisfaction.

Number of visits as a moderator

Repeat visits are an indicator of a visitor’s experience with the destination (Kerstetter and Cho, 2004). The number of visits ‘represents a key marketing variable in segmenting and targeting certain groups and developing a marketing action plan, including product, distribution, pricing and promotion decisions’ (Baloglu 2001, p. 127). Thus, it is a crucial aspect of tourism research.

First-time and return visitors behave differently. According to Mitchell, et al. (2005), ‘experience can work for or against the consumer with respect to confusion’ (p. 147). Consumers without sufficient product knowledge and facing many choices encounter difficulty in decision making (Heitmann, Lehmann and Herrmann, 2007). This difficulty in information processing likely leads to confusion (Johnson and Russo, 1984). Matzler, et al. (2011) found that product knowledge negatively affects consumer confusion. With lower levels of information searched, consumers involved in low-involvement purchase are less likely to be confused because of information overload (Mitchell, et al., 2005); however, consumers may, through putting in more effort, avoid confusion during a high-involvement purchase (Foxman, Berger and Cole, 1992).

Lim, et al. (2016) found that, for recreational and wellness tourist attractions in South Korea, the motivation and satisfaction levels of first-time and return visitors differed. Their behaviour at the destination also differed. Repeat visitors to New Zealand visit fewer attractions than those who visit for the first time (Oppermann, 1997). First-time visitors explore a broad range of activities that are geographically dispersed, while repeat visitors travel to shop, dine, and socialise with friends and family while in Hong Kong (Lau and McKercher, 2004). First-timers look for new experiences, while return visitors look for something that they are comfortable and familiar with (Kim, et al., 2012).

Furthermore, the satisfaction perception of visitors who have toured only once and those who made repeated visits relies on different interpretations of their experiences at the destination (Yuksel, 2001). Previous experience also affects visitors’ perception of the destination image (Fakeye and Crompton, 1991). Chew and Jahari (2014) point out that ‘repeat tourists have different cognitive processes in image formation and travel behaviour than those of first-time visitors’ (p. 383).

Since the number of visits is an important parameter for destination marketing organisations, knowing more about the differences between first-timers (those visitors who have made a single visit to the destination) and repeaters (those visitors who have made more than one visit) can help destination marketing organisations understand visitors better, design destination positioning, and improve visitor satisfaction (Lim, et al., 2016). Thus, this study postulates the following:

H5: Number of visits moderates the above relationships.

Method

Past studies’ construct items were altered to match the requirements of this study (Table 1). The items for overload confusion were modified from Lu, et al.(2016). The items of escape experience, regret, and trip satisfaction were obtained from Oh, et al. (2007); Kang, Hong and Lee (2009); and Lee, et al. (2014), respectively. Survey respondents indicated the degree to which they concurred with the items on a five-point Likert scale ranging from not at all (1) to a lot (5).

The cognitive destination image’s attributes differ across destinations. To obtain a list of attributes of Hualien that is extensive, yet sufficiently brief enough for this study, the attributes summarised by Echtner and Ritchie (2003) were used as the initial list. Through discussions with visitors who have toured Hualien, those attributes that were irrelevant or unimportant, such as political stability and city atmosphere, were deleted. This mechanism eventually produced a list of 10 cognitive attributes (Table 1). The four often-adopted affective attributes were utilised in this study (Beerli and Martin, 2004). The survey participants rated the extent to which they agreed with the attributes on a five-point Likert scale.

| Construct | Item |

|---|---|

| Overload confusion (OC) | I felt confused because there are so many Hualien information websites to choose from. The more Hualien information websites I browsed, the more confusion I experienced. I felt overwhelmed by too much information provided by those Hualien information websites (deleted). |

| Escape experience (EE) | I felt like I was living in a different time or place. I completely escaped from reality. I felt I played a different character here (deleted). |

| Regret (RE) | I feel sorry about choosing the attractions in Hualien. I regret choosing the attractions in Hualien. I should have chosen other alternative attractions in Hualien |

| Trip satisfaction (TS) | I am happy with my decision to visit Hualien. My Hualien experience here exceeded my expectations. Overall I am satisfied with my Hualien visit |

| Destination image | |

| Nature cognitive (DN) | Farm Nature Good scenery Sea view Shoreline |

| Non-nature cognitive (DNN) | Good accommodation quality Clean Food Friendly locals Good service quality |

| Affective (DA) | Unpleasant-pleasant Gloomy-exciting Sleepy-arousing Distressing-relaxing |

Research assistants were employed to reach out to potential respondents through convenience sampling. They had to ensure, by questioning, that the potential respondents were Taiwan residents who had toured Hualien and had used online websites to look for information regarding Hualien. If the criteria were met, the potential respondents were then provided with information regarding the purpose of the survey and invited to complete the paper-based survey form.

Those survey respondents who had only visited Hualien once were classified as first-timers, and those who had visited Hualien more than once were labelled as repeaters. In accordance with the process in Beerli and Martin (2004) and Lim and Weaver (2014), the obtained data of destination image attributes were subjected to factor analysis. This study also used SmartPLS to perform partial least squares analysis for the two visitor groups. This method was used because it is applicable for appreciating complex models (Urbach and Ahlemann, 2010), such as the model considered in this study. The method also does not have stringent requirements for residual distributions and sample size (Chin, 1998). The partial least squares, multi-group analysis (Henseler, Ringle and Sinkovics, 2009; Sarstedt, Henseler and Ringle, 2011) was then applied to compare each of the path coefficients in Figure 1 of the two groups of visitors (first-timers and repeaters), to identify the paths that significantly differ across these two groups of visitors.

Data analysis

Table 2 shows the respondents’ demographic profile, which is generally well spread, with a similar proportion of male and female respondents, in line with Taiwanese being generally well educated, and Hualien is popular across all age groups. Among the 226 returned survey forms, 119 respondents had toured Hualien once (the first-timers), and 107 had toured Hualien twice or more (the repeaters).

| Variable | First timers (n=119) | Repeaters (n=107) | Total (n=226) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Percent | No. | Percent | No. | Percent | |

| Sex: Male | 60 | 50.4 | 48 | 44.9 | 108 | 47.8 |

| Female | 59 | 49.6 | 59 | 55.1 | 118 | 52.2 |

| Age: 18-20 | 14 | 11.8 | 18 | 16.8 | 32 | 14.2 |

| 21-30 | 54 | 45.4 | 28 | 26.2 | 82 | 36.3 |

| 31-40 | 11 | 9.2 | 29 | 27.1 | 40 | 17.7 |

| 41-50 | 25 | 21.0 | 20 | 18.7 | 45 | 19.9 |

| >50 | 15 | 12.6 | 12 | 11.2 | 27 | 11.9 |

| Education: Senior-high & below | 40 | 33.6 | 35 | 32.7 | 75 | 33.2 |

| Undergraduate | 73 | 61.3 | 64 | 59.8 | 137 | 60.6 |

| Graduate | 6 | 5.0 | 8 | 7.5 | 14 | 6.2 |

| Employment: Student | 42 | 35.2 | 32 | 29.9 | 74 | 32.8 |

| Manufacturing | 50 | 42.0 | 34 | 31.8 | 84 | 37.2 |

| Services | 14 | 11.8 | 20 | 18.7 | 34 | 15.0 |

| Other | 13 | 11.0 | 21 | 19.6 | 34 | 15.0 |

| No. of visits: 1 | 119 | 100 | 119 | 52.7 | ||

| 2 | 61 | 57.0 | 61 | 27.0 | ||

| 3 | 19 | 17.8 | 19 | 8.4 | ||

| 3 | 27 | 25.2 | 27 | 11.9 | ||

The factor analysis of the destination image attributes showed a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of 0.91 and a Bartlett test of sphericity of 2854.87, which is significant; three factors (cumulative variance explained = 79.10%) were extracted and labelled as nature, non-nature, and affective (Table 1).

| Variable (see Table 1) | First-timers | Repeaters | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | AVE | CR | Alpha | Mean | SD | AVE | CR | Alpha | |

| OC | 2.83 | 0.72 | 0.80 | 0.89 | 0.76 | 2.55 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.83 |

| EE | 3.77 | 0.68 | 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.74 | 3.97 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.86 | 0.67 |

| RE | 2.47 | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.90 | 0.83 | 2.29 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.93 | 0.89 |

| TS | 3.68 | 0.62 | 0.78 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 3.96 | 0.68 | 0.83 | 0.94 | 0.90 |

| DN | 4.13 | 0.66 | 0.83 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 4.31 | 0.64 | 0.83 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

| DNN | 3.67 | 0.56 | 0.66 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 3.90 | 0.66 | 0.72 | 0.93 | 0.90 |

| DA | 3.83 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 4.17 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.96 | 0.94 |

| Note: There is a significant difference across the two visitor groups for all the constructs (ρ<0.05) except RE | ||||||||||

The constructs possess internal consistency reliability since the composite reliability values are larger than 0.7 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Average variance extracted (AVE) values exceeding 0.5 support convergent validity. Discriminant validity (Chin, 1998) exists because the square root of the AVE of each construct is larger than the correlation coefficients involving the construct (Table 4), the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) requirement is met, and the HTMT confidence interval does not contain the value 1 (Henseler, Ringle and Sarstedt, 2015). Collinearity does not exist since the VIF values are lower than the value of 5 (Hair, Ringle and Sarstedt, 2011).

| DA | DNN | DN | OC | EE | RE | TS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-timers | |||||||

| DA | 0.90 | ||||||

| DNN | 0.44 | 0.81 | |||||

| DN | 0.43 | 0.54 | 0.91 | ||||

| OC | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.06 | 0.90 | |||

| EE | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.51 | -0.17 | 0.89 | ||

| RE | -0.09 | -0.06 | -0.30 | 0.53 | -0.45 | 0.86 | |

| TS | 0.34 | 0.43 | 0.50 | -0.13 | 0.72 | -0.50 | 0.89 |

| Repeaters | |||||||

| DA | 0.93 | ||||||

| DNN | 0.64 | 0.85 | |||||

| DN | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.91 | ||||

| OC | -0.30 | -0.41 | -0.39 | 0.92 | |||

| EE | 0.53 | 0.44 | 0.52 | -0.41 | 0.86 | ||

| RE | -0.55 | -0.54 | -0.57 | 0.70 | -0.43 | 0.91 | |

| TS | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.53 | -0.64 | 0.91 |

| Note: Diagonal elements (in bold) show the square root of AVE. Off-diagonal elements are correlations between constructs | |||||||

The outcomes of the hypothesis testing and the partial least squares multi-group analysis are listed in Table 5.

Results and discussion

Overload confusion

Overload confusion is the only construct considered in this study for which the mean is higher for first-timers (mean = 2.83) than for repeaters (mean = 2.55). The means of the other constructs are significantly lower when the visitors are first-timers than repeaters (escape experience: first-timers = 3.77; repeaters = 3.97; nature cognitive destination image: first-timers = 4.13; repeaters = 4.31; non-nature cognitive destination image: first-timers = 3.67; repeaters = 3.90; affective destination image: first-timers = 3.83; repeaters = 4.17; trip satisfaction: first-timers = 3.68; repeaters = 3.96), or similar (regret: first-timers = 2.47; repeaters = 2.29). This observation shows that first-timers are more susceptible to overload confusion than are the more experienced repeaters. This finding supported those of past studies, such as Heitmann, et al. (2007) and Matzler, et al. (2011).

| Hypothesis | First-timers | Repeaters | Multi-group analysis (H5) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path-value | t-value | Path-value | t-value | ||

| H1a: Overload confusion→Escape experience | |||||

| OC→EE | -0.17* | 2.21 | -0.41** | 6.06 | Yes |

| H1b-1: Overload confusion→Cognitive destination image | |||||

| OC→DN | -0.06 | 0.63 | -0.39** | 5.41 | Yes |

| OC→DNN | 0.00 | 0.04 | -0.41** | 5.34 | Yes |

| H1b-2: Overload confusion→Affective destination image | |||||

| OC→DA | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.02 | |

| H1c: Overload confusion→Regret | |||||

| OC→RE | 0.47** | 5.24 | 0.63** | 8.54 | |

| H1d: Overload confusion→Trip satisfaction | |||||

| OC→TS | 0.12 | 1.08 | -0.02 | 0.14 | |

| H2a: Escape experience→Regret | |||||

| EE→RE | -0.38** | 4.61 | -0.17 | 1.73 | |

| H2b: Escape experience→Trip satisfaction | |||||

| EE→TS | 0.49** | 4.48 | 0.19 | 1.70 | Yes |

| H3a: Cognitive destination image→Affective destination image | |||||

| DN→DA | 0.28* | 2.60 | 0.29** | 3.70 | |

| DNN→DA | 0.28** | 2.63 | 0.47** | 5.63 | |

| H3b: Cognitive destination image→Trip satisfaction | |||||

| DN→TS | 0.11 | 1.30 | 0.15 | 1.47 | |

| DNN→TS | 0.10 | 1.08 | 0.17 | 1.41 | |

| H3c: Affective destination image→Trip satisfaction | |||||

| DA→TS | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.62 | |

| H4: Regret→Trip satisfaction | |||||

| RE→TS | -0.30** | 2.80 | -0.33** | 2.60 | |

| Notes: 1. * Significant paths at ρ<0.05 level; ** Significant paths at ρ<0.01 level 2. Multi-group analysis: Yes – significant difference across groups at the ρ<0.05 level. 3. First-timer: R2 of DA=0.24; DN=0.00; DNN=0.00; EE=0.03; RE=0.42; SAT=0.60. 4. Repeater: R2 of DA=0.46; DN=0.15; DNN=0.17; EE=0.17; RE=0.52; SAT=0.55. | |||||

The study further provides additional insights on the negative effect of information on satisfaction and the less-considered constructs of escape experience and destination image as information becomes excessive. Firstly, previous studies have proposed that information can enhance trip satisfaction. However, this study found that information associated with overload confusion, instead of enhancing trip satisfaction, could have no effect on trip satisfaction (H1d: path coefficient of first-timers = 0.12; repeaters = −0.02). It also makes visitors regret visiting the destination (H1c: path coefficient of first-timers = 0.47; repeaters = 0.63). This study thus supported the finding of Keaveney, et al. (2007) that overload confusion significantly contributes to a sense of regret.

Secondly, this paper provides the empirical relationship between overload confusion and escape experience. The analysis showed that overload confusion negatively impacts escape experience (H1a: path coefficient of first-timers = −0.17; repeaters = −0.41), and, according to the partial least squares multi-group analysis, there is significant difference between the path coefficient across the two visitor groups. Thus, the negative effect of overload confusion on escape experience is felt more strongly by repeaters than first-timers. This finding could be explained by the difference between tourists’ behaviour at the destination arising from the number of visits. Everything about the destination is new during the first trip. Hence, the effect of the confusion arising from too much information during the information search is less able to exert its negative influence on escape experience. However, repeaters should have already visited many of the destination attractions and would therefore need more information to discover additional attractions, or to have more in-depth touring ideas to achieve the escape feeling, which results in repeaters being more susceptible to overload confusion.

Thirdly, even though past studies have often illustrated that information contributes to destination image (Greaves and Skinner, 2010), this study suggests that the contribution of information to destination image could be minimal or possibly decrease. Thus, according to past literature, having more information can enhance the destination image, but, once a certain information threshold that leads to confusion has been reached, the contribution of overload confusion to the cognitive destination image becomes insignificant for first-timers (H1b-1: path coefficient of nature cognitive destination image = −0.06; non-nature cognitive destination image = 0.00) and undermines destination image for repeaters (H1b-1: path coefficient of nature cognitive destination image = −0.39; non-nature cognitive destination image = −0.41), and their path coefficients differ significantly across the two visitor groups. Similarly, given the more broad and exploratory nature of visits by first-timers, overload confusion is not able to exert its negative influence on these visitors. However, the more in-depth type of visit by repeaters renders the negative impact of overload confusion on cognitive destination image more strongly felt.

The impact of overload confusion

Escape experience

It is encouraging to observe that repeaters (mean = 3.97) have a significantly higher level of escape experience than do first-timers (mean = 3.77). The possible reasons are that repeaters are less likely to rush from one attraction to another, have more in-depth travel, are more able to immerse themselves in the environment, and have deeper appreciation of Hualien.

The escape experience can reduce the feeling of regret for first-timers but not repeaters (H2a: path coefficient of first-timers = −0.38; repeaters = −0.17), thus indicating that repeaters are more demanding and less easy to please than are first-timers. Whilst partially supporting studies, such as Lee, et al. (2014) and Oh, et al., (2007), this suggests that experience positively influences tourists’ satisfaction, and even though repeaters have more escape experience than first-timers, the contribution of escape experience to trip satisfaction is significantly higher for first-timers (H2b: path coefficient = 0.49) and significantly different from repeaters (H2b: path coefficient = 0.19), which is not significant, hence illustrating again the more demanding nature of repeaters.

Regret

The negative effect of regret over visiting the wrong destination attractions on satisfaction is prevalent for both first-timers and repeaters (H4: path coefficient of first-timers = −0.30; repeaters = −0.33), thus confirming the finding of past studies that regret can lower satisfaction (Bui, et al., 2011; Tsiros and Mittal, 2000).

Destination image

The study supported the findings of past research, such as Chen and Phou (2013) and Papadimitriou, et al. (2018), that the cognitive dimension contributes to the affective dimension of destination image (H3a: nature cognitive destination image - path coefficient of first-timers = 0.28; repeaters = 0.29, and non-nature cognitive destination image - path coefficient of first timers = 0.28; repeaters = 0.47). While Kim, et al. (2012) and Laing, et al., (2014) have shown that the destination image influences satisfaction, this was not the case in this study. Hence, as a whole, satisfaction is more affected by regret followed by escape experience than by the other examined factors.Number of visits as a moderator

As discussed above, this paper augments the existing literature on the difference between first-timers and repeaters. The difference is particularly evident in the consequence of overload confusion and escape experience. As a whole, overload confusion is more strongly felt by repeaters than first-timers. The escape experience is negatively affected by overload confusion and is more strongly felt by repeaters than first-timers. The negative impact of overload confusion on nature and non-nature cognitive destination image is also more strongly felt by repeaters than by first-timers. On the other hand, escape experience influences trip satisfaction in a positive manner and is more strongly felt by first-timers than repeaters (which is insignificant). The result again suggests that repeaters are more demanding than first-timers, as the latter move from the touch-and-go and exploratory type of visit to in-depth visits.

Practical implications

This paper shows the ability of overload confusion to undermine escape experience and increase the regret associated with a trip. It can also lower the destination image perceived by repeaters. The lowering of escape experience could increase regret, and regret would lower trip satisfaction. The negative impact of overload confusion is particularly felt among repeaters. While it is not possible for destination marketing organisations to prevent others from providing information about the destination, they should act on the issue of overload confusion. Destination marketing organisations should heed the advice of Bawden, et al. (1999), who emphasised the need for individuals and organisations to exercise control to cope with information overload. Thus, while destination marketing organisations should continue to provide quality information on their own public tourism websites (Kua and Chen, 2015) and a good and concise summary of good information available beyond the destination marketing organisation websites, it will be useful for destination marketing organisations to work with and promote a few selected and major bloggers and websites to provide authoritative information so that these sites would be the first stop for potential visitors, thereby lowering overload confusion. They should also promote the expertise of these bloggers to the public.

Destination marketing organisations should conduct further studies on the types and depth of information needs of their visitors, particularly on the repeaters, and organise or co-ordinate the information to reduce overload confusion. Such a move is also in line with the various strategies to cope with information overload and suggested in information science research and, thus, with how tourists will respond when faced with information overload. For example, Savolainen (2007) has suggested individuals may adopt the filtering and withdrawal strategies to cope with information overload. The former coping strategy involves ignoring information considered useless, and the latter deals with keeping the number of information sources used to a minimum.

Besides the filtering and withdrawal strategies, Saxena and Lamest (2018) also mentioned the summarising strategy. By providing useful and relevant information that caters to the needs of first-timers and repeaters, as well as useful summaries, the information sources manned by destination marketing organisations and bloggers will not likely be the casualties as a result of the filtering and withdrawal strategies adopted by the visitors. Promoting the expertise of the websites also fits well with another visitor’s strategy to cope with information overload, i.e., preference for shortcuts provided by experts (Stanton and Paolo, 2012).

The implications for destination marketing organisations are also relevant to bloggers who specialised in tourist destinations. Since the study has shown that repeaters are generally more demanding than first-timers, bloggers could carefully consider the customer segment they wish to better serve and provide articles with the required breadth and depth accordingly. They should also actively promote themselves beyond the Internet world to avoid being ignored by readers when they adopt the various coping strategies arising from information overload.

Research limitations and future research directions

This study has limitations, even though it provides several interesting insights. This study used a convenience sampling method. Although the respondents have a broad profile, caution is needed in extending the results to other contexts. This study is limited to Hualien, a rural and nature-based tourist destination. The cognitive destination image attributes of one destination are likely to differ from those of another destination. Future research could examine different types of destinations. The study shows that as the amount of information reaches a certain threshold, its positive effect on escape experience, destination image and trip satisfaction declines or even becomes negative. Hence, this study suggests that future studies could consider the rate and other influencing factors of the diminishing positive effect of information on these constructs.

This study has only considered overload confusion. Further studies could include the other two types of confusion, namely, similarity confusion and ambiguity confusion, and investigate how these three types of confusion are related in the tourism context. The study has only considered the destination image formed by visitors after a trip. However, visitors, especially repeaters, already have some image of the destination before the trip formed through the content of the information sources they have read and/or their previous visit. It will be useful to include the destination image before the trip as a construct and consider how it works together with overload confusion to influence destination image after the trip. This study has also suggested an interesting link between overload confusion and destination image. It will be of interest to both information science researchers and marketers if future studies could extend the concept of information overload and consider the impact of overload confusion on brand image and country image and examine whether some generalisation could be made about the role of overload confusion in shaping the image of products and services.

Conclusions

This study provides a direct link between overload confusion and two tourism-related concepts that have not been adequately explored: destination image and escape experience. It further illustrates that there is a limit to the influence of information on the frequent concerns of destination marketing organisations, i.e., trip satisfaction and, to some extent, destination image, even though past studies have often illustrated that information positively affects trip satisfaction and destination image. Once information leads to overload confusion, information could have no further positive impact on these two constructs. Furthermore, the negative effect of information appears when the volume of information becomes too much for tourists to cope with and causes overload confusion. Overload confusion adds to the undesirable outcome of regret and undermines the desirable outcome of escape experience. This study also further contributes to the existing literature on the difference between first-timers and repeaters. Thus, this paper also adds to the literature of information science by providing evidence of the applicability of the concept of information overload to the tourism context, and its negative effect which is also prevalent in some commonly discussed tourism-related concepts.

About the authors.

Wee Kheng Tan received his Ph.D. from National University of Singapore. He is an Associate Professor at National Sun Yat-sen University, Taiwan. His research interests include electronic commerce, consumer behaviour, tourism and leisure activities. He can be contacted at tanwk@mail.nsysu.edu.tw

Ping-Chen Kuo is a master’s degree student at Yuan Ze University. His research interests are e-commerce and e-tourism.

References

- Baloglu, S. (2001). Image variations of Turkey by familiarity index. Tourism Management, 22(2), 127-133.

- Baloglu, S. & Brinberg, D. (1997). Affective images of tourism destination. Journal of Travel Research, 35(4), 11-15.

- Baloglu, S. & McCleary, K.W. (1999). A model of destination image formation. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(4), 868-897.

- Bawden, D. & Robinson, L. (2009). The dark side of information: overload, anxiety and other paradoxes and pathologies. Journal of Information Science, 35(2), 180-191.

- Bawden, D., Holtham, C. & Courtney, N. (1999). Perspectives on information overload. Aslib Proceedings, 51(8), 249-255.

- Beerli, A. & Martin, J.D. (2004). Factors influencing destination image. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 657-681.

- Bi, J. & Lehto, X.Y. (2018). Impact of cultural distance on international destination choices: the case of Chinese outbound travellers. International Journal of Tourism Research, 20(1), 50-59.

- Bui, M., Krishen, A.S. & Bates, K. (2011). Modelling regret effects on consumer post-purchase decisions. European Journal of Marketing, 45(7/8), 1068-1090.

- Chang, Y.P., Gao, Y. & Zhu, D.H. (2015). The impact of product regret on repurchase intention. Social Behavior and Personality, 43(8), 1347-1360.

- Chen, C. & Phou, S. (2013). A closer look at destination: image, personality, relationship and loyalty. Tourism Management, 36, 269-278.

- Chew, Y. & Jahari, S. (2014). Destination image as a mediator between perceived risks and revisit intention: a case of post-disaster Japan. Tourism Management, 40, 382-393.

- Chin, W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. In G. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (pp. 295-358). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Crompton, J.L. (1979). An assessment of the image of Mexico as a vacation destination and the influence of geographical location upon the image. Journal of Travel Research, 18(4), 18-23.

- Curtin, S. (2005). Nature, wild animals and tourism: an experiential view. Journal of Ecotourism, 4(1), 1-15.

- Desmeules, R. (2002). The impact of variety on consumer happiness: marketing and the tyranny of freedom. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 12(12), 1-33.

- Dickinson, J.E., Hibbert, J.F. & Filimonau, V. (2016). Mobile technology and the tourist experience: (dis)connection at the campsite. Tourism Management, 57, 193-201.

- Echtner, C.M. & Ritchie, J. (2003). The meaning and measurement of destination image. Journal of Tourism Studies, 14(1), 37-48.

- Eppler, M.J. (2015). Information quality and information overload: the promises and perils of the information age. In L. Cantoni & J.A. Danowski (Eds.), Communication and technology (pp. 215-232). Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton.

- Eppler, M.J. & Mengis, J. (2004). The concept of information overload: a review of literature from organization science, accounting, marketing, MIS, and related disciplines. The Information Society, 20(5), 325-344.

- Fakeye, P.C. & Crompton, J.L. (1991). Image differences between prospective, first-time, and repeat visitors to the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Journal of Travel Research, 30(2), 10-15.

- Feng, Y. & Agosto, D.E. (2017). The experience of mobile information overload: struggling between needs and constraints. Information Research, 22(2), paper 754. Retrieved from http://informationr.net/ir/22-2/paper754.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6r2R7ZVch)

- Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50.

- Foxman, E.R., Berger, P.W. & Cole, J.A. (1992). Consumer brand confusion: a conceptual framework. Psychology and Marketing, 9(2), 123-141.

- Greaves, N. & Skinner, H. (2010). The importance of destination image analysis to UK rural tourism. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 28(4), 486-507.

- Hair, J.F., Ringle, C.M. & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139-152.

- Heitmann, M., Lehmann, D.R. & Herrmann, A. (2007). Choice goal attainment and decision and consumption satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(2), 234-250.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M. & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modelling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115-135.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M. & Sinkovics, R.R. (2009), The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In R.R. Sinkovics, & P.N. Ghauri (Eds.), New challenges to international marketing (pp. 277-320). Bingley, UK: Emerald. (Advances in international marketing, volume 20)

- Jackson, T.W. & Farzaneh, P. (2012). Theory-based model of factors affecting information overload. International Journal of Information Management, 32(6), 523-532.

- Jeng, J. & Fesenmaier, D.R. (2002). Conceptualizing the travel decision-making hierarchy: a review of recent developments. Tourism Analysis, 7(1), 15-32.

- Johnson, E.J. & Russo, E.J. (1984). Product familiarity and learning new information. Journal of Consumer Research, 11(1), 542-550.

- Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. (1982). The psychology of preferences. Scientific American, 246(1), 160-173.

- Kang, I., Cheon, D. & Shin, M.M. (2011). Advertising strategy for outbound travel services. Service Business, 5(4), 361-380.

- Kang, Y.S., Hong, S. & Lee, H. (2009). Exploring continued online service usage behavior: the roles of self-image congruity and regret. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(1), 111-122.

- Kangun, N. & Polonsky, M.J. (1995). Regulation of environmental marketing claims: a comparative perspective. International Journal of Advertising, 13(4), 1-24.

- Kaur, P., Dhir, A., Chen, S. & Rajala, R. (2016). Understanding online regret experience using the theoretical lens of flow experience. Computers in Human Behavior, 57, 230-239.

- Keaveney, S.M., Huber, F. & Herrmann, A. (2007). A model of buyer regret: selected prepurchase and postpurchase antecedents with consequences for the brand and the channel. Journal of Business Research, 60(12), 1207-1215.

- Kerstetter, D. & Cho, M.H. (2004). Prior knowledge, credibility and information search. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(4), 961-985.

- Kim, H. & Chen, J.S. (2016). Destination image formation process: a holistic mode. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 22(2), 154-166.

- Kim, J.H. (2014). The antecedents of memorable tourism experiences: the development of a scale to measure the destination attributes associated with memorable experiences. Tourism Management, 44, 34-45.

- Kim, K., Hallab, Z. & Kim, J.N. (2012). The moderating effect of travel experience in a destination on the relationship between the destination image and the intention to revisit. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 21(5), 486-505.

- King, C., Chen, N. & Funk, D.C. (2015). Exploring destination image decay: a study of sport tourists’ destination image change after event participation. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 39(1), 3-31.

- Krishen, A.S., Bui, M. & Peter, P.C. (2010). Retail kiosks: how regret and variety influence consumption. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 38(3), 173-189.

- Kua, E.C.S. & Chen, C.D. (2015). Cultivating travellers’ revisit intention to e-tourism service: the moderating effect of website interactivity. Behaviour & Information Technology, 34(5), 465-478.

- Laing, J., Wheeler, F., Reeves, K. & Frost, W. (2014). Assessing the experiential value of heritage assets: a case study of a Chinese heritage precinct, Bendigo, Australia. Tourism Management, 40, 180-192.

- Lau, A. & McKercher, B. (2004). Exploration versus acquisition: a comparison of first-time and repeat visitors. Journal of Travel Research, 42(3), 279-285.

- Lee, K., Lee, H.R. & Ham, S. (2014). The effects of presence induced by smartphone applications on tourism: application to cultural heritage attractions. In Z. Xiang, & I. Tussyadiah (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2014: proceedings of the international conference in Dublin, Ireland, January 21-24, 2014 (pp. 52-72). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Li, X., Pan, B., Zhang, L. & Smith, W. (2009). The effect of online information search on image development: insights from a mixed-methods study. Journal of Travel Research, 48(1), 45-57.

- Lim, Y. & Weaver, P.A. (2014). Customer-based brand equity for a destination: the effect of destination image on preference for products associated with a destination brand. International Journal of Tourism Research, 16(3), 223-231.

- Lim, Y.J., Kim, H.K. & Lee, T.J. (2016). Visitor motivational factors and level of satisfaction in wellness tourism: comparison between first-time visitors and repeat visitors. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(2), 137-156.

- Lu, A.C.C., Gursoy, D. & Lu, C.Y.R. (2016). Antecedents and outcomes of consumers’ confusion in the online tourism domain. Annals of Tourism Research, 57, 76-93.

- Martin, H.S. & Bosque, I.A. (2008). Exploring the cognitive-affective nature of destination image and the role of psychological factors in its formation. Tourism Management, 29(2), 263-277.

- Matzler, K., Stieger, D. & Füller, J. (2011). Consumer confusion in Internet-based mass customization: testing a network of antecedents and consequences. Journal of Consumer Policy, 34(2), 231-247.

- Mitchell, V.W., Walsh, G. & Yamin, M. (2005). Towards a conceptual model of consumer confusion. Advances in Consumer Research, 32(1), 143-150.

- Moon, S-J., Costello, J.P. & Koo, D-M. (2017). The impact of consumer confusion from eco-labels on negative WOM, distrust, and dissatisfaction. International Journal of Advertising, 36(2), 246-271.

- Oh, H., Fiore, A.M. & Jeoung, M. (2007). Measuring experience economy concepts: tourism applications. Journal of Travel Research, 46(2), 119-132.

- Oppermann, M. (1997). First-time and repeat visitors to New Zealand. Tourism Management, 18(3), 177-181.

- Papadimitriou, D., Kaplanidou, K.K. & Apostolopoulou, A. (2018). Destination image components and word-of-mouth intentions in urban tourism: a multigroup approach. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 42(4), 503-527.

- Pine, B.J., & Gilmore, H.J. (1999). The experience economy: work is theatre and every business a stage. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Sarstedt, M., Henseler, J. & Ringle, C.M. (2011). Multi-group analysis in partial least squares (PLS) path modelling: alternative methods and empirical results. In M. Sarstedt, M. Schwaiger, C.R. Taylor (Eds.), Measurement and research methods in international marketing (pp. 195-218). Bingley, UK: Emerald. (Advances in international marketing, volume 22)

- Savolainen, R. (2007). Filtering and withdrawing: strategies for coping with information overload in everyday contexts. Journal of Information Science, 33(5), 611-621.

- Saxena, D. & Lamest, M. (2018). Information overload and coping strategies in the big data context: evidence from the hospitality sector. Journal of Information Science, 44(3), 287-297.

- Schwartz, B., Ward, A., Monterosso, J., Lyubomirsky, S., White, K. & Lehman, D.R. (2002). Maximizing versus satisficing: happiness is a matter of choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(5), 1178-1197.

- Shang, R.A., Chen, Y.C. & Chen, S.Y. (2013). The effects of the number of alternative products and the way they are presented on the consumers’ subjective statuses in online travel sites. Behaviour & Information Technology, 32(7), 630-643.

- Sproles, G.B. & Kendall, E. (1986). A methodology for profiling consumers’ decision-making styles. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 20(2), 267-279.

- Stanton, J.V. & Paolo, D.M. (2012). Information overload in the context of apparel: effects on confidence, shopper orientation and leadership. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 16(4), 454-476.

- Swar, B., Hameed, T. & Reychav, I. (2017). Information overload, psychological ill-being, and behavioral intention to continue online healthcare information search. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 416-425.

- Thorson, E., Reeves, B. & Schleuder, J. (1985). Message complexity and attention to television. Communication Research, 12(4), 427-454.

- Tseng, A. (2017). Why do online tourists need sellers' ratings? Exploration of the factors affecting regretful tourist e-satisfaction. Tourism Management, 59, 413-424.

- Tsiros, M. & Mittal, V. (2000). Regret: a model of its antecedents and consequences in consumer decision making. Journal of Consumer Research, 26(4), 401-17.

- Turnbull, P.W., Leek, S. & Ying, G. (2000). Customer confusion: the mobile phone market. Journal of Marketing Management, 16(1-3), 143-163.

- Urbach, N. & Ahlemann, F. (2010). Structural equation modelling in information systems research using partial least squares. Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application, 11(2), 5-40.

- Voase, R. (2018). Holidays under the hegemony of hyper-connectivity: getting away, but unable to escape? Leisure Studies, 37(4), 384-395.

- Walsh, G. & Mitchell, V-W. (2010). The effect of consumer confusion proneness on word of mouth, trust, and customer satisfaction. European Journal of Marketing, 44(6), 838-859.

- Walsh, G., Hennig-Thurau, T. & Mitchell, V-W. (2007). Consumer confusion proneness: scale development, validation, and application. Journal of Marketing Management, 23(7-8), 697-721.

- Wang, Q. & Shukla, P. (2013). Linking sources of consumer confusion to decision satisfaction: the role of choice goals. Psychology and Marketing, 30(4), 295-304.

- Yuksel, A. (2001). Managing customer satisfaction and retention: a case of tourist destinations, Turkey. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 7(2), 153-168.

- Zeelenberg, M. (1999). Anticipated regret, expected feedback and behavioral decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 12(2), 93-106.

- Zeelenberg, M. & Pieters, R. (2007). A theory of regret regulation 1.0. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17(1), 3-18.

- Zeelenberg, M., van Dijk, W.W., Manstead, A. & van der Pligt, J. (2000). On bad decisions and disconfirmed expectancies: the psychology of regret and disappointment. Cognition and Emotion, 14(4), 521-541.

- Zhang, H., Fu, X., Cai, L. & Lu, L. (2014). Destination image and tourist loyalty: a meta-analysis. Tourism Management, 40, 213-223.