published quarterly by the university of borås, sweden

vol. 24 no. 4, December, 2019

Introduction. The concept of desire lines is defined, contextualised and explored within the area of information landscapes. The paper problematises the existence of desire lines in relation to research which has been conducted with various refugee groups.

Method. The concept of desire lines is expanded and linked to the library and information science field by drawing from the authors empirical research projects and from the scant literature from geography, urban planning and from a social theory.

Conclusion. The concept of desire lines contributes to the nascent research area of fractured information landscapes and offers a way of understanding how information landscapes are shaped when people are resettling into a new setting. While the work presented in an emerging conceptualisation, the authors also believe there is potential to conceptualise the rebuilding of landscapes as an occurrence within any transitionary environment (e.g. starting a job, moving to a new country, or transitioning from university to work).

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same, (Frost, 2015)

The purpose of this conceptual and exploratory paper is twofold. Firstly, the paper introduces the concept of desire lines, and contextualises this concept within the area of information landscapes. Secondly, it presents examples which highlight the existence of desire lines in relation to the field of refugee studies. Frost’s poem is used to demonstrate the authors’ observations that people express their desire to exert their agency, even when organisational discourses provide them with established pathways to knowledge (including, inter alia, guidelines and searching strategies) and this desire has implications for the way in which we understand information seeking and searching, by highlighting agentic role contribution to the construction of information landscapes.

For the purposes of this paper, we define a desire line (a term adopted from physical geography) as a representation of an intended and purposeful direction of travel which does not employ formally managed or directed routes across a landscape, but is reliant on the complimentary relationships between people and their environments which furnishes affordances described as opportunities for people to interact (Gibson, 1977; Norman, 1988). While exploratory, the concept of desire lines is applied to deepen an understanding of how people approach and navigate the information pathways of complex and unfamiliar environments to build information landscapes.

The concept or theory of desire lines has received minimal attention within library and information science. However, the authors argue that when viewed as an extension to the existing work around information landscapes, desire lines have the potential to add an additional and valuable dimension to the discipline, by illustrating both the purpose and direction of travel across these landscapes and drawing attention towards agency. Agency is viewed in this paper as the attempt made by people to gain control of their lives, as they bump up against contexts, conditions and relations that influence the social structures and attempt to enable or constrain it (Sewell, 1992; Giddens, 1986).

It is also anticipated that the development and application of the concept of desire lines will contribute to an extension to the nascent research area of fractured information landscapes research (Lloyd, 2017). The term fractured landscape has been used to describe an outcome of forced migration and resettlement which creates the condition for transition and disrupts the existing information environments and by virtue information landscapes which have previously anchored people to communities (Lloyd, 2017). While the authors have used the concept in relation to refugees’ experiences of resettlement, we believe there is potential to conceptualise the rebuilding of landscapes as an occurrence within any transitionary environment (e.g. starting a job, moving to a new country, or transitioning from university to work).

To construct a way of being in the world, people interact with an information environment and draw from it to construct information landscapes which reference the sites of knowledge and ways of knowing that are central the realisation of subjectivity and scaffold individual agency. Information environments reflect the social, epistemic/instrumental and corporeal modalities of information which shape and support established bodies of knowledge that have been built up over time (Lloyd, 2010; Antweiler, 1998). Information to and from these modalities is accessible through membership and established expertise and has the potential to travel through a range of social and material doings (sharing, observation, making and remaking). Information environments are consequently treated in the first instance, as larger sites of stable knowledge (epistemic sites about technical/material practices and ways of knowing, normative rules and regulations, traditions, histories, etc) representing an intersubjective dimension which references shared language, and mutual understanding about what constitutes knowledge and ways of knowing (e.g. cultural understandings about how to be a parent, how to be worker, what knowledges are important in relation to health; how to be a worker, or a poet). Intersubjectivity therefore acts as a dimension of sociality (Lloyd, 2017).

Information landscapes (Lloyd, 2010) reference the intersubjective space created when people interact with the information environments. Information landscapes enable discourse to be materialised (Barad, 2007) and evolve through interaction with other people, material objects and the embodied performances of a specific setting (Lloyd, 2006). This space references the taken for granted and agreed modalities and sources of information that reflect enterprises and performances of people engaged in collective action. To enter a new culture, society and its communities, new members have to learn about the cultural material, economic, political and historical resources that shape the site of the social (Schatzki, 2002; Lloyd, 2006) and what enables and constrains their access to knowledges and information. By undertaking this form of information work, they create their information landscapes and its paths, nodes and edges. They also have to engage with information practices such as information literacy, information sharing, observing others while they demonstrate know-how and expertise that will provide them with the capacity to engage with information.

In the construction of information landscapes, people may take less obvious or formalised paths to the information required (i.e. they may not search or seek information in expected or designated ways). In taking the road less travelled they potentially create desire lines which trace their travel across information environments. Desire lines may not be formalised but reference individual agency (to resist a formal path) and are therefore subject to cultural and social considerations.

Despite being a relatively well-understood physical phenomenon in the related fields of physical geography and urban planning, desire lines - also known as desire paths, cow paths, pirate paths, social paths, game trails, social trails, Chemins de l’âne (donkey paths), kemonomichi (beast trails), and Olifantenpad (elephant trails) - lack a robust, inclusive definition. Even the origin of the term itself is debatable. The French Philosopher Gaston Bachelard is often cited as the originator of the term ‘desire lines’, in his 1959 work ‘The Poetics of Space’ (Bachelard, 1959). However, the work itself makes no explicit mention of desire lines or desire paths.

Ahola (2013) suggests that: ‘A desire path is a path that is formed when people choose not to use the path that you have paved for them. It’s the shortest or otherwise most convenient way for them to get from point A to point B.’ These paths actively ignore physical layouts or other structural considerations which are very often created on an aesthetic rather than functional basis. However, there may be a variety of reasons for the development of desire lines. Kolhstedt (2016) proposes that ‘[S]ome present obvious shortcuts or offer less-steep courses while others allow people to avoid alarmed exits or address regional superstitions.’

In her article for the New York Times, Brown (2003) emphasised the significance of desire lines in highlighting a purposeful direction of travel: ‘In areas with no sidewalks, beaten-down paths in the grass, known as “desire lines" in planning-speak, indicate yearning, said John La Plante, the chief traffic engineer for T. Y. Lin International, an engineering firm. “When sidewalks are provided, people do walk," he said.’ Perhaps conversely, McFedries (2003) suggests that desire lines may be less purposeful: ‘Desire lines (or natural desire lines, as they're also called) are those well-worn ribbons of dirt that you see cutting across a patch of grass, often with nearby sidewalks — particularly those that offer a less direct route — ignored. In winter, desire lines appear spontaneously as tramped down paths in the snow. I love that these paths are never perfectly straight. Instead, like a river, they meander this way and that, as if to prove that desire itself isn't linear and (literally, in this case) straightforward.’ The routes that are defined by desire lines may indicate a form of navigation for future travellers, as Kohlstedt (2016) proposes: ‘…[t]hese paths frequently become self-reinforcing: others intuit the potential advantages of a newly-forming route and follow it, thus eroding it further and enhancing its visibility.’While their origins rest in physical geography and planning, Ahola (2013) suggests that desire lines (or paths) can be observed in other domains more closely aligned with information:

‘They exist in your products, services, and organizations. The paths that you have designed into your products are often not the paths that people actually tread along when they use your product. The way that people access public services is often not the way that the authorities designed them to be accessed. People don’t necessarily enter your organization through the front door, but rather by talking about you on your unmonitored backyard.’

Conceptualising desire lines, or the use of desire lines as a metaphor within theories can be highlighted by the work of Nichols (2014) who proposes social desire paths described by this author as ‘instances wherein individual interests and desires collectively, but independently, make imprints on the social landscape over time.’ Nichols suggests that in addition to a theoretical contribution to the sociology of interests, social desire lines may also relate to the development of policies and programs. In this sense, social desire lines are closely related to informational desire lines in that they may be used to identify systemic issues in the configuration of information systems and processes (including migration), and act as a base for subsequent refinement and improvement. She goes on to highlight a critical issue affecting the power dynamics of desire lines: ‘The most challenging aspect of such analyses, as in all policy-making endeavours, is to balance the typically distinct, often competing, values that may drive the creation of the same path.’

In the same way in which desire lines are created in physical landscapes, and subsequently used by urban planners to inform urban design, so too can they exist in virtual or information contexts. Bramley (2018) proposes that desire lines illustrate ‘the tension between the native and the built environment and our relationship to them’. A similar tension is highlighted via informational desire lines. However in these cases, the tension exists in the form of a power dynamic in which desire lines act to test or subvert a specific process. Their significance is due to their creation and ownership by information users, as opposed to the creators of information content. As such, they function outwith organisational constraints, readily adopted to support conformity and adherence to the formal linkages which exist between institutions of societal governance.

Desire lines enable access to ‘informalised’ information content which may be unregulated but may have a significant implicit informational value. For example, they may well utilise highly nuanced vernacular, local and narrative forms of knowledge and expertise. As such, informational desire lines, like physical desire lines are reliant on ongoing human interactions and thus contribute to the information landscapes and reference a form of agentic control which draws from the embodied experiences of interacting with larger formal information environments to embed themselves, and provide a form of wayfaring for future travellers (e.g. health, immigration, organisational). Linking to less formalised information content (such as personal blogs) by formal institutions is, on the whole largely ignored, using a rationale of control, however we could argue that links to informal and personal insights are purposefully ignored to avoid the potential to circumvent institutional processes.

We could argue that the recognition and further, the potential adoption of desire lines by formal institutions is an explicit recognition of the role and value of less formal information sources and content. However, the level to which these may be adopted is directly related to the extent to which they stand in opposition to the vested organisational and societal interests these institutions represent. Unlike formalised information pathways, desire lines may be less constrained by societal and behavioural ‘norms’, and as such provide the creators and users with a perceived or actual sense of ungoverned autonomy, which places agentic self at the centre of the journey, as opposed to the institutions which may seek to impose order on the process of navigating information landscapes.

The authors suggest that desire lines are present within virtual and non-physical contexts where routes of travel within and across information environments represent ‘short cuts’ between information ‘nodes’. These nodes act as information sources or access points, and may themselves be physical or virtual, existing in a myriad of forms including websites, databases, articles and people which aid in the formation and conceptualization of personal information landscapes. For example, the use of social media platforms such as Twitter and Instagram present alternatives short cuts, to more normative, organisational sources of information. These may include physical sources such as libraries and information resource centres, but also colonised online sites such as Facebook, which are frequently little more than shop-windows. In this example, Twitter and Instagram may be mapped into the landscape as a source preference and the use of the source reflects an agentic response which may differ from more traditional search strategies or information skills taught in formal information literacy classes.

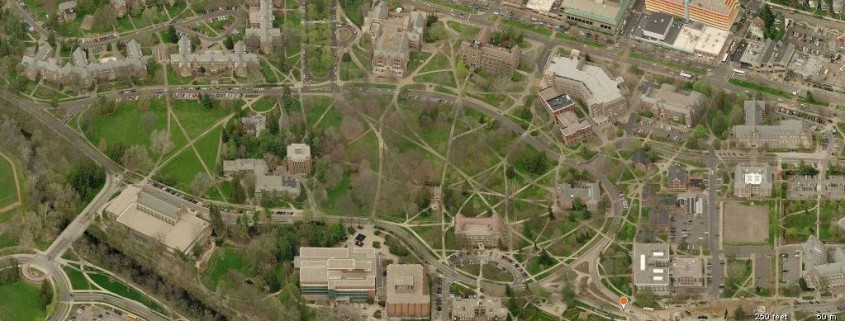

Over time however, both physical and virtual desire lines may act to guide the design of urban and digital environments. Nichols (2014, p.167) argues that ‘[u]rban planners and landscape architects are mixed about what to do when desire paths become part of planned landscapes. Some argue that desire paths provide helpful information in determining the usability of space and should be taken into account in future designs or used to modify existing landscapes.’ In the physical realm for example, designers may be influenced by people’s interaction with the landscape - ‘In Finland planners are known to visit their parks immediately after the first snowfall, when the existing paths are not visible. People naturally choose desire lines, which are then clearly indicated by their footprints and can be used to guide the routing of paths.’ (Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea, 2011). Similar approaches have been used at a number of educational institutions in North America, including University of California (Berkley) and Michigan State University. Desire lines are allowed to form from user footfall, and then these informal paths are used to form the basis of formal routes around campus. This suggests that mapping people’s information landscapes and the choices they make in their construction may provide a useful way of understanding what information or source is preferred by people at the ‘moment of their practice’.

Aligned with this perspective, Bradley (2010) alludes to the existence of desire lines in websites, and the navigation of these spaces by users: ‘These people are creating desire lines through our websites. We can try our best to force them to do it our way, but they won’t. They’ll either do it their way or leave. A better approach would be to understand where the desire lines in our sites being created and adjust our designs to those desire lines.’

Perhaps unlike more formalised paths, informational desire lines may be more fluid, reacting to their physical counterparts, evolving based on new information relating to the pathway itself, and the journey along it. Given this, desire lines may be viewed as an interdependent set of dynamics parts (or steps) within an information network, which may encompass formal and informal content, as well as visible and what the authors describe as ‘dark’ or ‘hidden’ knowledge, a concept which will be further explored in a subsequent publication.

Referring to Penhale (2011), Loustau and Davis (2012), query why residents of an urban area prefer to cross train tracks than use pedestrian underpasses: ‘Underground viaducts – criticised for being too far apart from each other, as well as dark, dangerous, narrow, noisy and smelling of piss and pigeon shit- are the only legal ways to cross.’ (Penhale, 2011). Thus, desire lines not only highlight physical or virtual passage, but hint at the motivations why such journeys have been taken in the first place. Desire lines then raise issues for information service design, which are largely driven by facilitating organisations rather than the needs of end users.

Desire lines are bound up in concepts of legitimacy and legality. In the examples above, planners can be seen to be using these illicit informal routes as base-line information on which to build more naturalistic pathways. However, not all desire lines are viewed so favourably. In their consideration of the Montreal train system, Loustau and Davis (2012) relate the story of a local citizen prosecuted for crossing the train tracks. While the judge in her case agreed with her logic in terms of urban circulation, she was still fined to ‘uphold the law’. The point highlights the power invested in established systems and processes, seemingly at the cost of efficiency. They conclude their paper was a number of significant points which apply equally within both physical and virtual realms: ‘Within the daily movements of the city, an alternative understanding of access and rights is already asserted. By ‘alternative’, we understand a model that allows for non-conventional uses of the space, relying on a different kind of responsibility and collective practice.’ (Loustau and Davis, 2012)

This range of varying definitions, in addition to the variety of physical and theoretical considerations presented by desire lines points to a need for further research to both clarify and classify the types and forms of desire lines. However, while differing, the definitions presented above are (tacitly or explicitly) unified in the informality of desire lines.

The concept of affordance represents an important concept in our theorizing desire lines. The affordances of the environment are ‘what it offers the animal, what it provides for ill or good" (Gibson, 1979, p.68). In our terms, this suggests a complementary relationship between people and their environments. The notion of affordance is extended by Norman (1998) who suggests that an “ affordance refers to the perceived and actual properties of the thing, primarily those fundamental properties that determine just how the thing could possibly be used" (1988, p. 9). More recently, Nagy and Neff (2015) exploring the concept of affordances in relation to technology, problematised earlier concepts to account for the way in which individuals “perceive, approach and use technological artefact’s (p.7). These authors suggest that affordances are largely imagined by users considering emotional and social characteristics of interaction with mediated environments and comment that ‘people shape their media environments, perceive them and have agency within them because of imagined affordances" (p.1).

In theorising desire lines we interpret affordances drawing from the definitions as the opportunities offered by the information environment (health, education, work, sporting or hobby) for people to create short cuts or follow paths across that information environment. Further we suggest that when people engage with the information environments that intersect their lives (e.g. health, their work context, education), they learn to recognise the opportunities to resist formal pathways and thus create desire lines which lead them to the desired outcome. Desire lines therefore reference the opportunities users perceive or image that are available for them which will result in the desired outcome. Affordances therefore reference the invitational qualities, which are predicated on the individual’s ability to recognize and mediate the information environment and construct information landscapes by identifying the kinds of knowledges (i.e. the multiple sites of knowledge that constitute being in the world) that are valued by members who are engaged or connected to the practice of remaking (Lloyd, 2006).

In this section, we draw from examples of refugees’ experiences with formal information environments to highlight how desire lines might emerge through the circumvention of formal information pathways. Thus far, we have argued that desire lines may be seen as subversive, or as Knouf (2012) alludes to, a form of civil disobedience. They can be used to circumvent established formal processes for personal gain. However, these formal processes may not be without fault, and thus desire lines may not only be useful for planners and designers as previously suggested, but may in fact be used to shield travellers from harm. In this aspect, the yearning may refer to a desire to remain safe or to avoid or reduce surveillance which can have dire consequences (Gillespie et, al 2016; Wall, Campbell and Janbeck, 2017).

Taking the example of the current and highly publicised migration of those fleeing war in Syria into Europe and resettling into a destination country, there is a clear relationship between ‘real world’ desire lines and their virtual counterparts.

In the case of refugees, desire lines may exist below the visible information environments as evidenced by the use of the ‘dark web’, an unindexed part of the ‘deep web’ which has been related to hacking, pornography and drug dealing, and in relation to refugees, human trafficking or less dramatically, simply knowing the ‘trick’ to get first choice of housing in a difficult market.

Thus, desire lines may provide routes, not only between formal and informal information nodes, but between knowledge objects present (both tacitly and explicitly) of ‘dark knowledge’ addressing personal and societal needs which cross barriers of legality and legitimacy. Where can I find someone to smuggle my family to a safer country? How much will it cost? What are the risks involved? We may consider the explicit raising of these issues (albeit in covert forums) as paths, in that they provide routes for others to follow in both a physical and virtual sense.

Enabling organisations (governments, third sector agencies) that support refugees’ resettlement often provide a wealth of information via online information resources, often in the form of categorised lists or FAQs, for example The Scottish Refugee Council’s ‘Common questions and answers’ (Scottish Refugee Centre, 2019) and The Culture Atlas ‘Dos and Don’ts’ (2019). These lists become a de facto starting point for entry into information environments representing critical nodes or waypoints to perceived needs, such as how to obtain welfare payments, maintain and seek information about health, education, employment and housing Accessing these nodes enables the development of information landscapes. The creation, development and maintenance of these nodes is based on an understanding of informational needs, developed by stakeholders within these enabling organisations. However, they (generally) do not consider how access to these resources may be affected by (for example) cultural and social factors, in addition to levels of information literacy and language skills. As such, there is a failure of stakeholders and service providers to consider that access to information resources, or the recognition of what constitutes information, may be culturally framed or subject to suspicion because it has been supplied by government agency who have active participated in the surveillance of people (Gillespie 2016). Indeed, findings from prior research into the information needs of Syrian refugees in Lebanon (Internews, 2013) specifically emphasises an (over)reliance on word-of-mouth information from friends and family due to a perceived lack of trust in official sources.

As a result, refugees develop, may apply and share informal negotiated routes across information landscapes in the form of desire lines. Like physical desire lines, information desire lines are driven by a desire to move to a specific outcome, and are inherently less concerned with the mode of travel. However, lists of information resources provided by enabling organisations both tacitly and explicitly act to ‘guide’ refugees in a specific direction, using pre-determined channels in the form of processes. For example, a refugee seeking to obtain an appointment with a doctor may have been given guidance on how to engage with a health service, but understand that the process itself may be lengthy. As a consequence, they may create a desire line which utilises a hospital’s accident and emergency ward to circumvent this process, and subsequently share their knowledge of this ‘workaround’ with friends and family. Or they may be created as people try to work through medical information by pooling together their knowledge of information sources (Martzoukou and Burnett, 2018). Similarly, in a recent study of refugees resettling in Sweden (Lloyd, Pilerot and Hultgren, 2016) participants, describe how they circumvented official advice on how to obtain housing and making bids for housing stock as it became available each week. Formal information about the process was circumvented and alternate pathways were created based on people’s lived experiences of getting housing. This information was shared among relatives and friends which provided information about how to be the first caller of the day.

Recent studies of refugees’ experiences of resettlement after forced migration, indicate that this process has the potential to fracture the previously established information landscapes of people which have been built overtime (Lloyd, Pilerot and Hultgren, 2017). To rebuild these landscapes refugees must renegotiate their access to legal, political and practical knowledge bases in order to obtain refugee status within European states (Lloyd, 2017). These journeys across information environments and the rebuilding of information landscapes may be at odds with legal and ethical issues present in the countries through which the migrants travel (Gower and Hawkins, 2013). Even once those physical journeys are complete, refugees must continue to revise their information landscapes by developing understanding of new ways of acting and being in their host countries, accommodating language barriers, cultural and religious factors and other more pragmatic issues relating to housing, education, healthcare and modes of recreation (Lloyd, 2017).

The physical and informational journeys form the fabric of the refugee narrative, one not only of the journey itself, but encompassing what has been learned and experienced throughout the journey. These stories and narratives may remain largely tacit (Burnett, 2012), however, if explored and exploited, they may provide an important and significant source of procedural and declarative knowledge to other actual and potential refugees, enabling and easing both the navigation across information landscapes and the physical journey undertaken by the refugees.

As well as highlighting alternative routes to information and knowledge, desire lines have other benefits. As suggested by Bramley (2018), desire lines not only show where to (and potentially how) to travel, but where one should not tread. Desire lines encompass and embed the personal knowledge of previous travellers within them, and may not only highlight what works, but also unsuccessful attempts or points of resistance. The current work has the potential to contribute to the emerging theorisation of sustainable information practice, by allowing us also consider how desire lines - as they emerge for individuals as acts of agency and resistance- can then can become a pooled resource which travels by being shared by others and mapped on to information landscapes.

In this respect, desire lines are not viewed as simply one-off ‘hacks’ used to circumvent an issue or solve a problem but may also represent semi-chronological narratives which tell the story of numerous personal journeys of resistance and agency across stable information environments with well-articulated/described ways of searching for information. Whether desire lines are employed deliberately to circumvent existing more formalised routes is currently an under researched area. An alternative perspective may be that desire lines highlight gaps in both information provision and content, and are thus created out of necessity. The active creation of desire lines then raises issues for information service design, which are largely driven by facilitating organisations rather than the needs of end users. A particular interest which guides this emerging conceptualisation is how and why people step off the formal established pathways and the implications of this decision.

Inextricably linked to the concept of desire lines is the ability to locate relevant and meaningful content largely, but not exclusively on the Internet. We can argue that the greater the degree to which information content conflicts with legitimacy, the more deeply this information may be hidden using secure areas of the internet, requiring special tools or permissions to access it. Our ability to locate and utilise desire lines within information landscapes is then dependent on our ability to find them.

So why do we use structured information paths and routes? They provide a perceived ‘safe’ environment with an accompanying reduction in personal risk. Our navigation of desire lines represents both a personal need, our agency, and a willingness to accept the risks of taking a path less travelled. There are a number of potential and actual concomitants relating to the use of desire lines. Firstly, the social and intellectual capital associated with the creation and utilisation of the desire lines themselves. The navigation of ‘physical’ desire lines enables the accumulation of procedural knowledge – ‘know how’. This knowledge if made explicit enriches the value of the desire lines by highlighting obstacles, bottlenecks and other potential pitfalls which may be encountered throughout the journey.

Potential and actual pitfalls present another valuable function in that they may allow for the creation of potentially more ‘effective’ or exploratory (incomplete) desire lines which act to probe a direction of travel as yet not undertaken. They may act to dissuade or ‘close off’ desire lines too hazardous for travel – here be dragons. Further, the desire lines themselves create a sense of shared experience and understanding – a collective empathy relating not only to the journey, but additional factors such as the drivers to using the pathway in the first instance.

To conclude with the final words from Robert Frost:

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less travelled by,

And that has made all the difference. (emphasis by authors)

Simon Burnett is a Professor of Information Management in the School of Creative and Cultural Business at Robert Gordon University. His research interests include storytelling, knowledge management, and information theory. He can be contacted at s.burnett@rgu.ac.uk

Annemaree Lloyd is a Professor in the Department of Information Studies at University College London. Her research explores the intersection between information, learning, practice and culture. She can be contacted at annemaree.lloyd@ucl.ac.uk .

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

|

|

© the authors, 2019. Last updated: 14 December, 2019 |

|