Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science, Ljubljana, Slovenia, June 16-19, 2019

Facilitation in library makerspaces: a prototype for a professional development model

Leanne Bowler, Tom Akiva, Sharon Colvin, and Annie McNamara.

Introduction. This paper presents Remake Making, a research project that explores an interactive, constructivist professional development methodology for people who work with youth in library maker spaces, asking the research question, How can a constructivist system of professional development support facilitated making in libraries? The goal of the project is to provide library staff with a set of heuristics to support self-awareness, intentionality, and relevance around their facilitation practices with young people at the library.

Method. The project applied methods of improvement science to iteratively design and test a range of professional development innovations around facilitation. Through a participatory process, 18 library staff, grouped into four cohorts, met for multiple sessions over the course of two months (five sessions in the first two cohorts; six sessions in each of the last two). Participants identified their own problems of practice and used improvement science methods to establish practitioner know-how.

Results. The central contribution of this study is a model for a constructivist approach to professional development, accompanied by strategies that arise out of the real-world experiences of practitioners. For the participants, the act of reflecting on practice through an improvement project surfaced an awareness about themselves as facilitators, suggesting that the end game for professional development should not be a packaged, one-size-fits-all training program but rather, a methodology that allows library staff to design a set of reflective activities contextualized for their own use, in their own communities.

Conclusions. By treating the facilitation of activities in library maker spaces as a practice that requires expertise, the project gives serious attention to an (often unacknowledged) aspect of library service. This research study also advances broader knowledge in the area of professional development, specifically as relates to improvement science, an applied science useful for investigating change-in-context for the purposes of improvement.

Introduction

Many in the world of informal learning, including librarians, have embraced the maker movement and its physical instantiation – the makerspace, a place where people explore real-world materials, tools, and technology. Proponents of makerspaces argue that such environments address 21st century skills and aptitudes such as creativity, innovation, transmedia navigation, visual literacy, and (if based in technology) computational thinking. The outcomes of learning in makerspaces, however, are not limited to a set of skills and aptitudes. The communal nature of makerspaces affords relationships, through the interpersonal connections that young people make in their engagements with adults, including librarians. These engagements can, according to bioecological systems theory, influence the development of young people (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006 ). Despite the implications for youth, library staff generally don’t discuss with each other in a formal way what these engagements look like, including the nature of their facilitation practices in makerspaces (although they readily acknowledge that their interactions with library users do matter). For most, it is a language that they simply don't have. To further complicate the matter, there are few tools available to help them understand and plan for facilitation in ways that make sense to their local communities.

This paper presents Remake Making, a three-year research project which asks, How can a constructivist system of professional development support facilitated making in libraries? The project aimed to map out an iterative, constructivist professional development methodology to support the facilitation of maker experiences in youth library services. We frame this study through the meta theoretical lens of social constructivism, a stance familiar to the field of Library and Information Science (Talja, Tuominen & Savolainen, 2005) and which argues that ‘knowledge is social in origin; the individual lives in a world that is physically, socially and subjectively constructed’ (82). The project, set in an urban public library system in the United States, opens a window on facilitated making in libraries through a set of heuristics that library staff can hold in their head when guiding makerspace activities and secondly, lays out a set of professional development innovations.

Library staff who work with young people often seek to improve their professional practice through formal programs of professional development. The context and format of these professional development programs can vary. Most people who work in public libraries are familiar with top-down, often one-shot, professional development training, generally presented at library association conferences or through on-site workshops led by senior staff or hired consultants. In such professional development, a best practice is presented during the workshop and then the work of adapting to context occurs afterwards, outside of the workshop. A more constructivist approach might ask participants, during the training, to define what works best in their world and would then scaffold the knowledge discovery process with tools and tactics that support practitioner expertise. (For example, watching a video recording of oneself, in one’s own place of work, during a professional development program requires less translation to the local context). Such an approach might also attempt to find a balance between broad, evidence-based knowledge and the local wisdom of practitioners.

Two themes run throughout the project. First, the project reveals library staff perspectives on facilitation techniques that support maker learning, allowing us to learn more about facilitation in the specific context of makerspaces for youth and, second, it explores the practices and effects of participant-driven professional development, with the goal of developing professional development models that are adjustable to context. The first theme relates to informal learning with youth; the second relates to library training for adults. The two themes are deeply interwoven in this project (and therefore, hard to disentangle). Nevertheless, in this paper, we focus on the professional development aspect, aiming to present a do-able set of heuristics and tools that have been field-tested with practitioners. The constructivist nature of these methods means that we purposefully do not lay out a set of best practices for facilitation in makerspaces for youth. Rather, the paper presents a general model and some examples of techniques that can help practitioners arrive at their own rules of engagement in maker spaces for youth.

Background

Facilitation in Libraries

Facilitators are essential to meaningful learning. These are the people who spark interest, attend to individuals’ learning paths, create social structures that promote participation, push young people to stretch thinking, and strengthen understanding (Larson, 2000; Larson, Walker, Rusk & Dias, 2015; Barron et al., 1998; Brown & Campione, 1994; Mayer, 2004; Lazonder & Harmsen, 2016).

The notion that library staff facilitate meaningful information experiences and learning is not unfamiliar to the library world – the reference interview is a classic example (Dervin & Dewdney, 1986). Human information interaction (and the role of information professionals in facilitating the relationship between people and information) is central to the field of library and information science, as decades of research in information behaviour demonstrates. Indeed, facilitation grounds most library practices. Dialogic storytelling – where the storyteller inserts verbal question prompts and think-alouds into storytelling – is a recommended practice in both public and school libraries today (Arnold & Colburn, 2011, 2012; Ghoting & Martin-Diaz, 2006; Ghoting & Martin-Diaz, 2013). Guided Inquiry, a curricular tool for supporting information literacy, is steered by interactions with school librarians (Kuhthau et al, 2015) Even science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) activities with youth in libraries are richer when guided by the strategic use of question prompts by adult mentors, as Bowler and Champagne (2015) discussed in their exploration into the development of critical technical practice. In short, creating and maintaining relationships with youth is a central task of staff in children’s and youth libraries, in addition to the traditional range of duties related to the provision and organization of resources.

Maker experiences are a new service model for the public library. In a library maker space, young people explore, invent, and build products using analog and digital materials. (Bagley, 2012; Britton, 2012; Britton & Considine, 2012; Martinez and Stager, 2014; Migus, 2014, Scott, 2012, Sheridan et al, 2014). Since this activity requires some measure of guidance from a person who understands the techniques, tools, and processes associated with the materials (like coding a robot, for example), the role of a knowledgeable facilitator is crucial. Facilitation in library maker spaces, therefore, is a rich area for investigation given that facilitators are a critical point of service for young people in this learning environment. However, even as we acknowledge facilitation as the connective tissue of libraries, we have found a dearth of research that explores quality improvement specific to facilitation in library maker spaces.

Simple Interactions: A Facilitation Model

Since a goal of the study is to reveal to practitioners the value of their small, everyday interactions with young people and provide them with a simple set of heuristics (or rules of thumb) for understanding their own facilitation techniques, we introduced the Simple Interactions framework ( www.simpleinteractions.org). This is an analytic tool grounded on bioecological systems theory which argues that interactions with adults in the community, and not just the home or school, are critical and worthy of attention (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006).

The SI tool has previously been applied in a range of youth-serving organizations to help educators become more mindful of their interactions with children and youth (Akiva et al, 2016; Li, 2017; Li & Winters, 2019). It helps practitioners get under the hood, as it were, in terms of revealing their own facilitation techniques. In the present study, the SI framework was used by library staff to analyze video-recordings of their own interactions with youth in the context of maker experiences. Table 1 below defines the four types of interaction styles - Connection, Reciprocity, Inclusion, and Opportunity to Grow.

| Interaction style | Description |

|---|---|

| Connection | Interacting with mutually-appropriate emotions. |

| Reciprocity | Balancing roles of engagement during joint activity |

| Inclusion | Inviting and engaging all children, especially those who may be least likely or least able to participate due to ability, temperament, or other factors. |

| Opportunity to Grow | Presenting incremental challenge and matching with appropriate support. |

Methods

Navigating between the top-down, best practices approach (typical in most library professional development activities) and a bottom-up, constructivist paradigm where people generate knowledge through lived experiences, is a core tension in the professional training of library staff. In this paper, we turn to improvement science to help us negotiate a pathway toward a flourishing professional practice. It provides a methodological framework for considering improvement within the framework of a learning institution. Improvement science, originally applied in the Health Sciences and manufacturing and more recently adopted within the field of Education, is both a research paradigm and set of methods (Lewis, 2015; Langley et al, 2009). It attempts to bridge knowledge bases, allowing tacit, local, and practical knowledge to rise up and meet organizational knowledge and formal disciplinary knowledge, thus creating a praxis of theory and practice. Improvement science is a design science that seeks to develop systems and methods for improvement. The method integrates evaluation into the design process in an intentional way, while addressing organizational constraints and local variations. The process is the product. Researchers in Library and Information Science are familiar with related methodologies that allow for reflection and collaborative design of information services, such as action research (Khoo, Rozaklis, & Hall, 2012), design-based research (Bowler & Large, 2008) and participatory or cooperative design (Druin, 1999, 2010; Yip et al, 2013, 2016). In this project we use such collaborative, iterative design as a form of professional development (Voogt et al, 2015).

A principle tool of improvement science is the plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle (Langley et al, 2009), a process of rapid prototyping and testing that reveals what changes, in context, are needed to produce improvement. Assessment in relation to educational goals is constant. Variability is amplified, unlike experimental models which seek to generalize. Critically, the cycle is purposefully situated within an organizational context, one of the features that distinguishes improvement science from other design-oriented methodologies. Langley’s PDSA cycle provides the inspiration for our own “Try-it-out" projects at the library, described below.

The Remake Making project, took place in an urban public library system in the United States. Researchers, alongside four cohorts of 18 library staff from children’s and teen services. The project applied methods of improvement science to iteratively design and test a range of professional development innovations around facilitation. The library staff met for multiple sessions over the course of two months (five sessions in the first two cohorts; six sessions in the last two). They considered their own problems of practice and used improvement science methods to establish practitioner know-how (Bryk, 2015), to review their own practices, try-out small tests of change in their facilitation practices, and share their learning with their colleagues. Evidence from the project includes artifacts from participant-led improvement projects (such as their brainstorming notes and their posters for the final Celebration of Learning), transcripts from last-day activities designed to elicit feedback within the training, personal reflections recorded by the researchers, summary notes from team meetings, feedback forms completed by the participants, transcripts from interviews, and the results from a survey. Analysis and evaluation were constant and iterative, guided by the driving research question, How can a constructivist system of professional development support facilitated making in libraries? We note here that the project is designing a process as much as it is deriving theory in relation to facilitation practices. The methods used in the study, therefore, serve as both procedure and results.

Results

We present here the findings to emerge from the Remake Making study, including an overview of the constructivist professional development model, a range of strategies and techniques, and a summary of feedback from the participants.

A Constructivist Professional Development Model for Facilitated Making

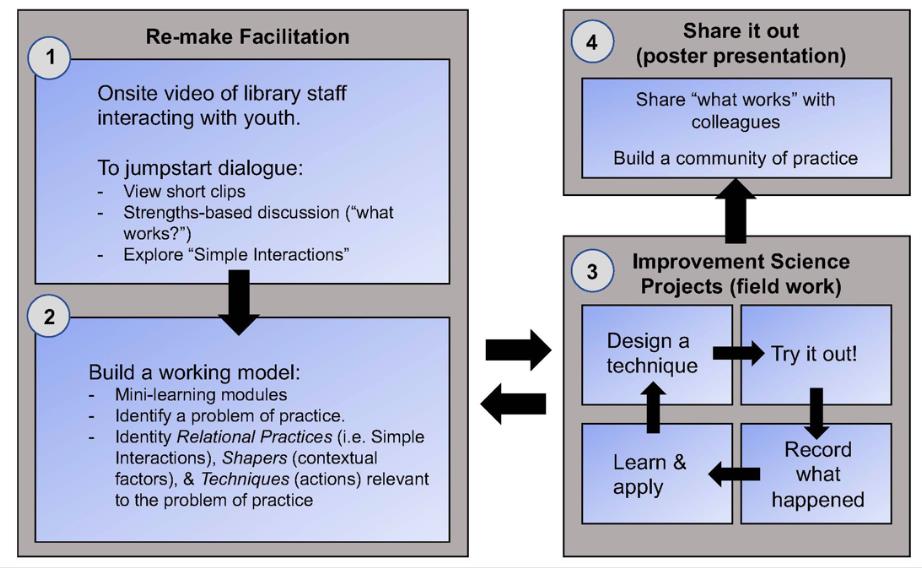

One of the central contributions of this study is a model of constructivist professional development that arises out of the real-world experiences of practitioners. The model unfolded in four stages, beginning with a video recording of the participants interacting with young people in maker activities at the library, followed by a learning module to help connect personal experience to broader knowledge about how young people learn, and then an exercise in the design of mini-improvement projects (which we called Try it out projects). In two cohorts an additional stage was added, where the participants shared their learning with their colleagues. Taken in its totality, the model provides a road map for a constructivist approach to professional development. Figure 1 below visualizes the model, derived in collaboration with the project’s partners in the field, the library staff who work directly with young people in children’s and youth services.

Figure 1: The Remake Making process model for constructivist professional development

(Source: Colvin, Akiva, and McNamara, 2019)

Strategies and techniques

The key elements of the Remake Making professional development model are detailed below and include 1) staff watching videos of themselves in practice situations and brainstorming ideas around relational practices, 2) attending to short learning modules, 3) the design and testing of new practices (called Try it out projects in this study), and 4) a poster presentation. These strategies and techniques were applied in emergent and adaptive ways and we would expect some modifications in any future iteration of this professional development methodology.

- Watching and discussing videos: Participants were recorded interacting with young people in the library (See Figure 2 below). They then watched the short videos alongside their colleagues. Viewing was followed by a strengths-based discussion using the Simple Interactions framework as a guide or set of heuristics, seeking to describe the nature of their interactions and interactional strategies that seemed to be productive. Several participants said that watching and discussing videos of themselves interacting with youth, provided a positive validation and helped them to gain confidence in their facilitation skills.

- Learning Modules: The participants encountered key ideas related to learning and development, the purpose being to help the participants situate their own practice within a broader, conceptual framework. The short presentations by the researchers (five to ten minutes) covered topics such as polyvagal theory, the link between interactions and social-emotional learning, principles of improvement science, and the effect of experiences on brain development. The learning modules were the least constructivist elements of the professional development model and so they were intentionally kept very short – five to seven minutes per module. Research presentations were also followed by facilitated discussion encouraging participants to connect research to their daily practice.

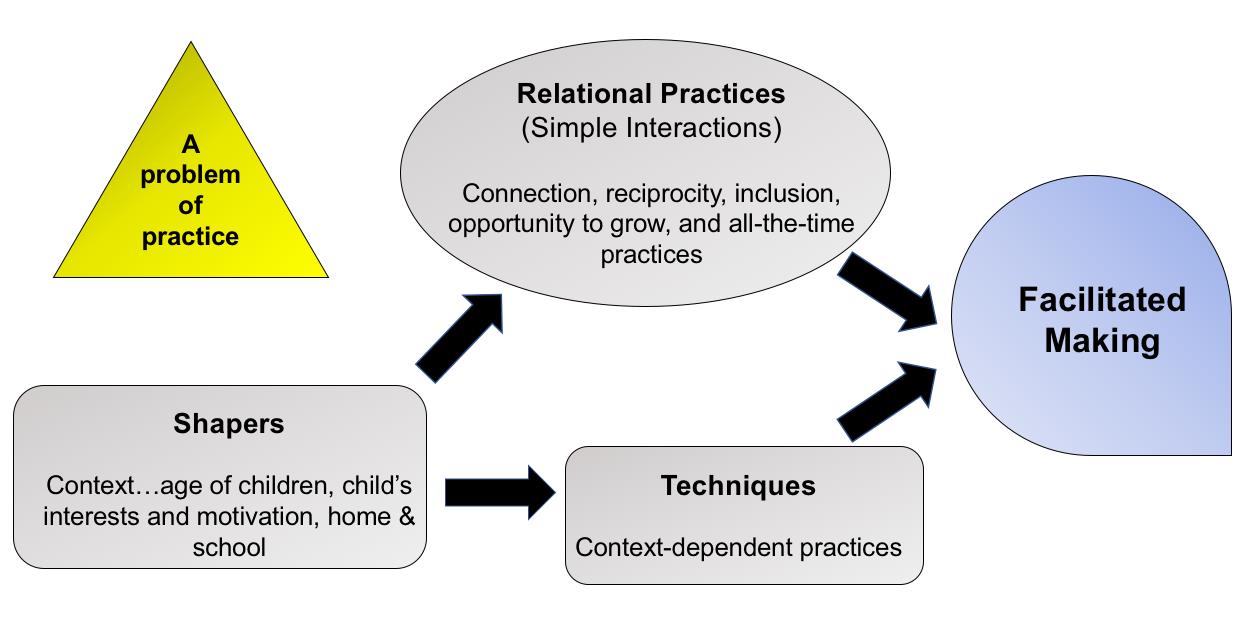

- ‘Try it out’ improvement science projects: Participants worked on their own improvement projects, applying the Try it out model provided by the project (See Figure 3 below). Each participant considered an area of their own practice which, in their own determination, needed growth. They identified a small change to their facilitation practices that they would try out and then articulated a hoped-for outcome and how they would know if that outcome was achieved (in other words, what would stand as evidence of that change). Feedback during this brainstorming process was invited from colleagues, sometimes in the form of sticky notes attached to a white board or paper with each participant’s problem of practice laid out. The Try it out projects were then tested in the field, with participants reporting back to their cohort one to two weeks later.

- 'Share it out' poster presentations. Later cohorts in the study presented their Try it out improvement projects with colleagues in children’s and teen services, in an event called a Celebration of Learning. The mode of communication was a poster presentation and attendees included current and past participants, other library colleagues, and other stakeholders (such as local foundation representatives).

Figure 2: Screen shot from a video of a library staff member facilitating a cooking activity with a teen.

Figure 3: Improvement science projects. The steps to follow for a Try it out project

An example problem of practice identified by one of the participants for a Try it out project was the challenge of building a community of learners (an issue in the public library where learning activities are drop-in). Using the model in Figure 3, participants brainstormed the style of interaction envisioned (i.e. relational practices), the factors shaping the situation (shapers), and some facilitation techniques that might help resolve the specific problem of practice (i.e. techniques). Unsurprisingly, the participants were highly sensitive to context. When thinking about shapers, some of the factors they mentioned were test days at school, the weather, the number of adults present, and ‘what’s happening with kids at home or school’, all helped to shape what happens in the library.

When thinking about techniques for improving facilitation, the participants were creative. Examples of techniques included: 1) introducing Simple Interactions into weekly meetings with other library staff to support dialogue among colleagues about interactions, 2) starting a video game tournament to encourage new friendships among peers, 3) asking youth about their interests in order to increase attendance in programs, and finally, 4) taking steps to draw upon the expertise and leadership of young people in the library (‘let youth lead’). These sample Try it out techniques were framed by considerations around relational practices and shapers and are not meant to be prescriptive: They arise out of, and serve, the real-world practices of the participants in this study. Some ‘tests of change’ - in other words, evidence that would count as a successful implementation of the Try it out project - were identified. For example, if a librarian’s goal was to encourage the relational practice of inclusion, what would serve as evidence that all (or certain) children had been included.

When the groups next met (approximately a week later), they reported on their tests of change. One positive story was reported by a children’s librarian. To address the problem related to building a community of learners in the children’s library, he had implemented a technique loosely described as ‘drawing upon expertise and leadership of young people’ by inviting a teen library patron to teach younger children how to create music videos on iPads using a ‘green screen’. Through reciprocity, inclusion, and by offering an opportunity to grow (all features of SI), the librarian had planted the seeds for a community of learners and gained a valuable youth partner in her library. Not all tests of change were successful. In the event, participants were asked to think about how they could learn from their projects when it didn’t work out as planned.

Feedback from the participants

As the targets of this professional development program, how did the participants experience it? In their view, might it support the growth and flourishing of facilitation in the library? Overall, the participants found the experience valuable, with one person from Cohort 3 saying it was ‘one of the most meaningful professional development opportunities I have participated in.’ The experience was found to be impactful, because it ‘illuminated for people that these things that they do every day, that they don't necessarily think about, are part of a specific educational practice and there's a word or a phrase for what they're doing’

In terms of the specific strategies (using the SI tool, watching and discussing videos, gaining new knowledge through the learning modules, and learning how to design a Try it out improvement project), feedback varied, depending on the cohort (and perhaps reflecting the adjustments made in the procedures along the way). The first cohort was more positive about the learning modules and less enthusiastic of the Simple Interactions tool, while later groups were less enthusiastic about the learning modules (‘useful, but not what stuck with me the most’), saying that the learning modules would have more impact if they helped to explain “the why behind our how" – in other words, more explicitly connected theory to their own practice. A later cohort was quite positive about the SI tool, with one practitioner saying that it helped them to ‘think critically/constructively about my everyday interactions’ and another agreeing that it made them ‘more deliberate’ in their interactions with youth. Since adjustments to the strategies were made in reaction to feedback from the earliest cohorts onward, reactions were more consistently positive during the latter sessions.

Several of the library participants told us that the Try it out projects allowed them to think outside the box, to see that there is ‘always another way that could work’. Thinking about their own facilitation practices allowed the participants ‘to think about it’, with one participant noting that the program provided her with space to reflect. The act of reflecting on practice through an improvement project surfaced a mindfulness about themselves as facilitators, suggesting that the end game for professional development should not be a one-size-fits-all training program but rather, a methodology that allows library staff to design a set of reflective activities contextualized for their own use in their own communities. But more personally, the training taught them about intentionality in everyday practice - to slow down, to notice and to become deliberate about their time with children and youth. The group experience was also valued because it provided a means to learn from everybody.

Despite an overall positive reaction, feedback from some participants revealed some confusion in terms of the specific professional development innovations around facilitation. Some participants relayed that they expected a traditional professional development workshop, where content is pre-packaged and delivered. The constructivist, open-ended approach to the Remake Making trainings did not fit into their conceptions of teaching and learning and we realized that new participants who are used to traditional, top-down professional development may be need more scaffolding to help them understand the constructivist paradigm applied in this approach to professional development. Furthermore, since constructivist professional development is slow and iterative (i.e. it isn’t enacted through a one-shot workshop), institutional buy-in is clearly needed in order for staff to have time to participate.

The study brought to the fore and legitimized the idea that interactions between library staff and youth are complex, cumulative, and meaningful. This notion was expressed by a participant, saying they learned that ‘the biggest things come from the smallest moments’. The participants called for more tools and learning-modules to share with their colleagues. They also wanted more time for reflection and experimentation. As a result of this feedback, more Try it out projects were added and the number of sessions increased.

The most valued aspect of this constructivist professional development program that consistently came through in feedback was the creation of a supportive community of practice. Learning from others, watching videos of themselves with their co-workers and getting positive feedback, and discovering new facilitation techniques, were features of this program that helped them gain confidence and satisfaction in their practice.

Conclusion

The Remake Making project provided professional development opportunities for library staff across four cohorts, as well as a real-world environment for experimenting with a constructivist program. Evidence drawn directly from the people for whom the program was intended grounds our process model of constructivist professional development. Our intention was not to derive a universal set of rules for facilitating maker experiences for youth but rather, a system of professional development that gives participants a chance to construct their own models for facilitated making. When implementing a constructivist approach, some initial work may be needed adapting library staff to a new way of thinking about training. The constructivist approach adopted in this study was not expected nor initially understood by some of the library staff who participated in our study (the direct transmission of information and best practices being a more common practice in many professional development programs). However, once experienced, nearly all library staff expressed great appreciation for the opportunity to chart their own journey.

Interactions with young people are central to the work of children’s and youth services library staff – work that deserves attention and respect in professional development. Relationships lie at the core of facilitation and the staff who interact with young people in maker spaces need adaptable tools that can be applied at a local and indeed, a personal level – to get at learning that arises out of experience and draws upon the considerable assets that staff bring to the library. The Remake Making project is ongoing, with expectations of expansion to other libraries and after-school learning environments where it will continue to design and test a constructivist, staff-led professional development program that supports facilitated making and speaks to the local needs of communities and the young people they serve.

Acknowledgements

The project Remake Making: Understanding Adoption and Adaptation of Facilitated Making in Libraries is supported through a grant from the National Science Foundation. Thomas Akiva (Principal Investigator) and Leanne Bowler, Kevin Crowley, and Peter Wardrip (Co-Principal Investigators). Award ID 1713299.

About the authors

Leanne Bowler is Associate Professor at School of Information, Pratt Institute, New York, United States. Her research and teaching focuses on human information interaction, youth technology practices, STEM learning, and how family, teachers, and out-of-school organizations, such as libraries and museums, support young peoples' competencies in socio-technical environments. She can be contacted at lbowler@pratt.edu.

Tom Akiva teaches at Department of Psychology in Education, University of Pittsburgh, United States. His research focuses on understanding and improving out-of-school learning (OSL) program experiences for children and youth. He can be contacted at tomakiva@pitt.edu.

Sharon Colvin is graduate student researcher at Department of Psychology in Education, University of Pittsburgh, United States. She can be contacted at sharon.colvin@pitt.edu.

Annie McNamara is graduate student researcher at Department of Psychology in Education, University of Pittsburgh, United States. She can be contacted at arm156@pitt.edu.

References

- Akiva, T., Li, J., Martin, K. M., Horner, C. G., and McNamara, A. R. (2016). Simple Interactions: Piloting a strengths- and interactions-based professional development intervention for out-of-school time programs. Child and Youth Care Forum.

- Arnold, R., and Colburn, N. (2011). The power of words: How librarians can help close the vocabulary gap. School Library Journal, 57 (7), 14.

- Barron, B. J., Schwartz, D. L., Vye, N. J., Moore, A., Petrosino, A., Zech, L., and Bransford, J. D. (1998). Doing with understanding: Lessons from research on problem-and project-based learning. Journal of the learning sciences, 7 (3-4), 271-311.

- Bowler, L. and Large, A. (2008). Design-based research for LIS. Library and Information Science Research. 30: 39-46.

- Bowler, L. and Champagne, R. (2016). Mindful making: Question prompts to help guide young peoples’ critical technical practices in DIY/maker spaces. Library and Information Science Research, 38(1), 117-124.

- Britton, L. (2012). The makings of maker spaces, part 1: Space for creation not just consumption. The Digital Shift. Retrieved July 15, 2019 from http://www.thedigitalshift.com/2012/10/public-services/the-makings-of-maker-spaces-part-1-space-for-creation-not-just-consumption/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/2ZDzz6M)

- Britton, L. and Considine, S. (2012). The makings of maker spaces, part 3: A fabulous home for cocreation. The Digital Shift. Retrieved July 15, 2019 from http://www.thedigitalshift.com/2012/10/public-services/the-makings-of-maker-spaces-part-3-a-fabulous-home-for-cocreation/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/2YKJHh8)

- Brown, A. L. (1992). Design experiments: Theoretical and methodological challenges in creating complex interventions in classroom settings. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 2 (2), 141–178.

- Brown, A. L., and Campione, J. C. (1994). Guided discovery in a community of learners. The MIT Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by design and nature. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. and Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In Lerner, R. M. and Damon, E. (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology (6th ed., pp. 793–828). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Bryk, A. S. (2015). 2014 AERA distinguished lecture accelerating how we learn to improve. Educational Researcher, 44 (9), 467-477.

- Colvin, S., Annie McNamara, A. and Akiva, T. (2018). Remake Making: A Constructivist Professional Development Model for Maker Educators. Connected Learning 2018

- Dervin, B., and Dewdney, P. (1986). Neutral questioning: A new approach to the reference interview. Reference Quarterly, 506-513.

- Druin, A. (1999, May). Cooperative inquiry: developing new technologies for children with children. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 592-599). ACM.

- Druin, A. (2010). Children as co-designers of new technologies: Valuing the imagination to transform what is possible. New directions for youth development, 2010 (128), 35-43.

- Ghoting, S. N., and Martin-Diaz, P. (2006). Early Literacy Storytimes @ Your Library: Partnering With Caregivers for Success. Chicago: American Library Association.

- Ghoting, S. N., and Martin-Díaz, P. (2013). Storytimes for Everyone!: Developing Young Children's Language and Literacy. ALA Editions.

- Khoo, M., Rozaklis, L., and Hall, C. (2012). A survey of the use of ethnographic methods in the study of libraries and library users. Library and information science research, 34 (2), 82-91.

- Kuhlthau, C. C., Maniotes, L. K., and Caspari, A. K. (2015). Guided inquiry: Learning in the 21st century: Learning in the 21st century. ABC-CLIO.

- Langley, G. L., Moen, R. D., Nolan, K. M., Nolan, T. W., Norman, C. L. and Provost, L. P. (2009). The Improvement Guide. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Larson, R. W. (2000). Toward a psychology of positive youth development. American psychologist, 55 (1), 170.

- Larson, R. W., Walker, K. C., Rusk, N., and Diaz, L. B. (2015). Understanding youth development from the practitioner’s point of view: A call for research on effective practice. Applied Developmental Science, 19 (2), 74–86.

- Lazonder, A. W., and Harmsen, R. (2016). Meta-analysis of inquiry-based learning: Effects of guidance. Review of Educational Research, 86 (3), 681-718.

- Lewis, C. (2015). What is improvement science? Do we need it in Education? Educational Researcher, January/February, 44 (1), pp. 54-61.

- Li, J. (2017). Growing simple interactions inside everyday practice. ALIGN Journal Special Edition: “From theory to practice: residential care for children and youth" (3) , 2 - 6. ALIGN Association of Community Services, Alberta, Canada. Retrieved from http://www.alignab.ca/align-resources/align-journal/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/2yHPGoa )

- Li, J. and Winters, D. (2019). Simple, Everyday Interactions as the Active Ingredient of Early Childhood Education. Childcare Exchange. Retrieved July 15, 2019, from https://www.childcareexchange.com/article/simple-everyday-interactions-as-the-active-ingredient-of-early-childhood-education/5024560/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/2TdKcLd)

- Martinez, S. L., and Stager, G. S. (2014). The maker movement: A learning revolution. Learning and Leading with Technology, 41 (7), 12-17.

- Mayer, R. E. (2004). Should there be a three-strikes rule against pure discovery learning? American psychologist, 59 (1), 14.

- Migus, L. H. (2014). Broadening Access to STEM Learning through Out-of-School Learning Environments. Washington DC: The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Committee on Successful Out-of-School STEM Learning.

- Moorefield-Lang, H. (2015). Change in the making: Makerspaces and the ever-changing landscape of libraries. TechTrends, 59 (3), 107–112.

- Scott, S.H. (2012). Making the case for a public library makerspace. Public Libraries Online. Retrieved July 15, 2019 from, http://publiclibrariesonline.org/2012/11/making-the-case-for-a-public-library-makerspace/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/2YuVbFZ)

- Sheridan, K. M., Halverson, E. R., Litts, B. K., Brahams, L., Jacobs-Priebe, L. and Owens, T. (2014). Comparative case study of three makerspaces. Harvard Educational Review, 84 (4), 505–532.

- Talja, S., Tuominen, K., and Savolainen, R. (2005). “Isms" in information science: constructivism, collectivism and constructionism. Journal of documentation, 61 (1), 79-101.

- Voogt, J., Laferriere, T., Breuleux, A., Itow, R. C., Hickey, D. T., and McKenney, S. (2015). Collaborative design as a form of professional development. Instructional science, 43 (2), 259-282.

- Yip, Jason C., Elizabeth Foss, Elizabeth Bonsignore, Mona Leigh Guha, Leyla Norooz, Emily Rhodes, Brenna McNally, Panagis Papadatos, Evan Golub, and Allison Druin. "Children initiating and leading cooperative inquiry sessions." In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, pp. 293-296. ACM, 2013.

- Yip, Jason C., Tamara Clegg, June Ahn, Judith Odili Uchidiuno, Elizabeth Bonsignore, Austin Beck, Daniel Pauw, and Kelly Mills. "The evolution of engagements and social bonds during child-parent co-design." In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 3607-3619. ACM, 2016.