The role of a data librarian in academic and research libraries

Isaac K. Ohaji, Brenda Chawner and Pak Yoong.

Introduction. This paper presents a data librarian role blueprint (the blueprint) in order to facilitate an understanding of the academic and research librarian's role in research data management and e-research..

Method. The study employed a qualitative ase research approach to investigate the dimensions of the role of a data librarian in New Zealand research organizations, using semi-structured interviews as the main data collection instrument.

Analysis.A data analysis spiral was used to analyse the interview data, with the addition of a job analysis framework to organize the role performance components of a data librarian.

Results. The influencing factors, performance components and training needs for a data librarian role form the basis of the blueprint.

Conclusions. The findings which are reflected in the blueprint provide a conceptual understanding of the data librarian role which may be used to inform and enhance practice, or to develop relevant education and training programmes.

Introduction

Data librarians are 'people originating from the library community, trained and specialising in the curation, preservation and archiving of data' (Swan and Brown, 2008, p. 1). This definition implies that the data librarian role is a professional position within academic and research librarianship that carries out e-research and/or research data management (RDM) support tasks. This paper describes the development of a data librarian role blueprint (the blueprint). The blueprint identifies dimensions of the role of academic and research librarians in research data management in order to provide a conceptual basis for the role. Although data librarians may work in the libraries of any type of research organization, the primary focus of this research was university libraries.

A conceptual or theoretical background for a profession has many advantages. First, it provides principles that underpin practice (Colley, 2003). Second, such a background improves the effectiveness of practice (Fargion, 2007). Third, it may guide and facilitate professional discussions, research, instruction and learning. Fourth, a conceptual foundation removes any ambiguities about the performance components (such as responsibilities and requirements) of a given professional role. Thus, a conceptual foundation provides someone new to the role with an overview of the components of professional practice in order to enhance his or her understanding of the purpose and nuances of the role. Finally, this foundation may provide experienced professionals with a framework for reflection and assessment.

The rest of this paper is divided into four main sections. The first section presents the background to the study. The second section outlines the research design while the third section discusses the findings. The final section concludes the paper.

Background to the study

The literature used as background to this paper focuses on three main areas. The first part considers research data and their management in order to provide a justification for research data management. The second part examines the involvement of academic and research libraries in research data management, particularly the inherent challenges, implications and effects. The third part summarises Abbott's The System of Professions: an essay on the division of expert labour (1988) which was used to develop the blueprint presented in this paper.

Research data and research data management

The Canadian Association of Research Libraries Data Management Sub-Committee (2009, p. 4) defines research data as 'the factual records (e.g., microarray, numerical and textual records, images and sounds, etc.) used as primary sources for research, and that are commonly acceptable in the research community as necessary to validate research findings'. Data are heterogeneous in scope and variegated in nature ranging from numbers, images, video or audio streams, software and software versioning information, algorithms, animations to models and/or simulations (National Science Board, 2005, p. 18). In addition, data can be voluminous and may be categorised based on the process of generating or storing them. The National Science Board (2005, p. 19) identified four broad categories: observational data, computational data, experimental data and records. Thomas (2011, p. 38) expanded these as:

- experimental data generated by lab equipment;

- computational/simulation data generated from computation models;

- observational data of specific phenomena at specific time or location;

- derived data produced via the processing or combining of other data (e.g., data mining);

- canonical data extracted from reference data sets;

- data storage solutions; and

- data curation.

There are two main sources of research data.The first is e-research which involves 'large-scale, distributed, national, or global collaboration in research' (O'Brien, 2005, p. 66). Hunter, Cook and Pope (2004, p. 2) noted that scientific research 'is increasingly being carried out through distributed, global collaborations, enabled by the Internet and related technologies'. The result of this has been referred to as a data deluge (flood of scientific data). Hey and Trefethen predicted the imminence of a data deluge in 2003 which became fulfilled early, raising the concern about managing and sharing research data over the long term (Borgman, 2010; 2011; Gold, 2007a).

The second main source of research data is a large number of small-scale projects that yield research data collections that 'are highly heterogeneous and tend to be isolated in scientists'[researchers'] offices and laboratories, yet they account for a substantial portion of the data assets at any given research university' (Palmer, Cragin, Heidorn and Smith, 2007, Introduction, para. 1.).

This increase in research data has created a need for a more formal approach to research data management. The Texas A&M (Agricultural and Mechanical) University Library Research Guides (2019) defined this as: 'the practices of organizing, documenting, storing, sharing, and preserving data gathered during a research project.'. The literature identifies several reasons to manage research data. First, Wong (2009, p. 125) argued that 'well-managed data in digital form have great potential to be searched, accessed, mined and re-used'. This view is particularly important given that research data fuel further research. As such, they are critical for the sustainability and reproducibility of research (Lynch, 2009).

The second justification is due to the nature of data-intensive research. Bell (2009, p. xiii) identified the three basic activities of data-intensive research as capture, curation and analysis. The implication is that the absence of any of these activities will limit the effectiveness of research data management. With regard to curation, Bell (2009, p. xiii) argued that uncurated data are guaranteed to be lost.

The third justification for research data management was expressed by Ashley (2012), who noted that the potential for reusing research data increases their value above the cost of their original acquisition. Collecting original data is costly in terms of time and resources, and by using data for multiple purposes, their value increases in relation to the cost of collection.

Finally, research data management implies a need to preserve data in a form that permits their re-use by researchers other than their original creators (Hey and Trefethen, 2003, p. 13). Academic and research library staff have extensive experience in information resources management, and this knowledge and skill could be transferable to a research data management role.

Academic and research library involvement in research data management

The justifications for research data management discussed above suggest that academic and research libraries have a role in research data management. Heidorn (2011, p. 663) identified four reasons for libraries to be involved in research data management:

- Curation of data is within the libraries' mission, and libraries are among the only institutions with the capacity to curate many data types.

- The data are critical to the scientific and economic development of society.

- There is a large volume of data not currently being curated adequately.

- Governmental and non-governmental funding bodies are beginning to recognise the importance of data and are creating rules for people receiving funds for research and development.

Resistance to the involvement of libraries in research data management may come from researchers in disciplines with their own tradition of research data management. Mullins (2010) noted that the term curation has different meanings in different fields and professions. To a scientist or an engineer, curation may involve making background documentation available in a database with regard to a project. In contrast, the librarian or archivist sees curation to be 'to store, provide access, preserve, and carry forward data into the future with assurance that the data will be accessible and retrievable for future verification or use' (Mullins 2010, p. 35). Curation has the same basic meaning in both contexts. However, the added dimensions of preservation and usability in the library and archivist perspective underline the importance of library involvement in research data management.

Over the last eighteen years, academic and research libraries have increasingly been involved in research data management. This involvement has challenges and implications for the librarians as well as effects on libraries and the information field.

The challenges

The challenges of research data management stem from three main issues. One is the nature of research data. An important component of this is the data deluge which results from the extent, scope and speed of data generation (Hey and Trefethen, 2003). Other characteristics of research data discussed by Salo (2010) that make managing them a complex problem include variability, backlog, project-orientation, and non-standard data and data formats. This complexity of managing research data has been described differently in the literature. Due to its complexity, authors such as Awre et al. (2015) and Cox, Pinfield and Smith (2014) describe research data management as a wicked problem. In comparison to other types of problem such as those related to staff, stock and systems for which the library profession has developed well-known approaches over the years, which they called tame problems, Cox, Pinfield and Smith (2014, p. 2) identified a wicked problem as 'one that is unique and highly complex, whose definition itself is disputed by those involved and whose solution is likely to remain unclear'. They argued that the point of distinction between tame and wicked problems is that if people know a problem is wicked they operate differently. This suggests that research data must be managed differently to more traditional library materials.

The second main issue that makes research data management challenging is the increasing value the scientists place on research data as discrete from the publications emerging from their research (Joint, 2007). This may be because governmental and non-governmental funding bodies are beginning to recognise the importance of data and are creating rules for people receiving funds for research and development (Heidorn, 2011). This new focus and emphasis on research data ultimately leads to shifts in the scholarly publication cycle and the underlying model (O'Brien, 2005). If the librarians are to manage research data successfully, they must be aware of these shifts. Borgman (2010) noted that academic and research libraries are shifting their focus from reader services to author services. In addition, there is a 'shift from primarily acquiring published scholarship to managing scholarship in collaboration with researchers who develop and use the data' (Lynch quoted in Goldenberg-Hart, 2004, p. 1). The final research data management challenge comes from the use of institutional repositories to support the e-research life cycle (Henty, 2008; Smith, 2011; Wong, 2009). The main issue with this stems from the characteristics of institutional repositories discussed by Salo (2010), which include being institutionally bounded and optimised for articles, and suffering from technical issues and inadequate staffing. Salo (2010, Introduction, para 1.) further suggested that, in order to avoid missteps in utilising institutional repositories for research data management, academic and research library staff need to 'understand the salient characteristics of research data, and how they do or do not fit with library processes and infrastructure'.

The challenges discussed above support giving separate attention to research data in line with Cox, Pinfield and Smith's (2014) suggestion that wicked problems be handled differently.

The implications

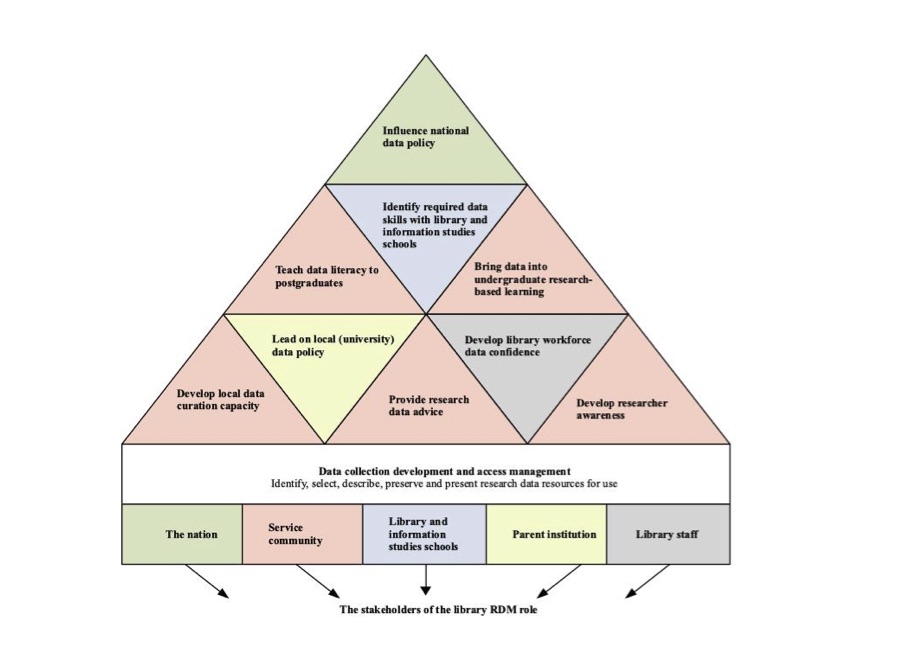

The involvement of library staff in research data management implies a new or adapted professional role. Luce (2008) proposed a three-fold role: supporting creation, connecting communities and curation. These activities will require library staff to develop supporting infrastructure, engage in disruptive thinking to identify novel solutions, implement new organizational structures and campus relationships, consider economic sustainability, and develop new skills (Case, 2008; Luce, 2008). Gold (2007b) noted that research data management falls within the upstream (pre-publication) and the downstream (post-publication) sides of the e-research cycle. Lewis (2010, p. 16) included nine of these activities in his research data management pyramid for libraries (the pyramid) shown in Figure 1.

Lewis (2010) noted that underlying the pyramid are two key non-technical strategic challenges: funding and policy, and workforce development. Corrall (2012, p. 111) added a base layer of collection development and access management to the pyramid and clarified that, even with the base layer, the pyramid still falls short of the complete set of activities in the Digital Curation Centre's lifecycle model. She noted that it concentrates on the areas reflecting competencies of librarians that are applicable to research data management. Analysing the nine activities within the Pyramid shows that they relate to five parties with an interest in research data management, shown as the base layer in Figure 1.

With regard to the library staff, some academic libraries are adapting their existing research support structure to support research data management. Cox, Verbaan and Sen (2012), Bresnahan and Johnson (2013), and Johnson and Bresnahan (2015) suggested that liaison and/or subject librarians be upskilled for this. Newton, Miller and Bracke (2011) reported that the e-Data Task Force for institutional repository dataset collecting at Purdue University, USA was made up of seven subject librarians. The findings of the second work package in Auckland's (2012) study revealed a considerable skills gap in nine areas of research data management in which subject librarians are expected to be involved in the future. The use of subject librarians to support research data management implies that they require training in the area of their skills gap. Their training triggers an interesting discussion for library administrators and educators whether the use of liaison or subject librarians to support research data management suffices or a specialist role model may be preferred. This paper favours a specialist role model.

Corrall (2012) highlighted options for training library professionals for research data management support credited to members of the International Data curation Education Action (IDEA). One involves training library professionals to work in digital or data curation. These professionals could be subject librarians, although the requirements of data description and use of technology in research data management roles provide a justification for involving metadata and digital librarians as well. Another option focuses on training digital or data curation professionals which points to a specialist individual role such as the data librarian or the data scientist.

In addition to the data librarian role, Swan and Brown identified three other key data roles: data creator, data scientist, and data manager (2008, p. 1). They defined data creators as 'researchers with domain expertise who produce data', data scientists as people who work 'in close collaboration with the creators of the data […], enabling others to work with digital data', and data managers as 'computer scientists, information technologists or information scientists and who take responsibility for computing facilities, storage, continuing access and preservation of data'. Pryor and Donnelly (2009) provided an overview that mapped a set of core skills to each of these four roles. However, Swan and Brown (2008) noted that although these roles appear to be distinct, in practice their demarcation might be blurred. This is particularly the case for the data librarian and data scientist roles which is typical of an evolving area. The following examples illustrate this overlap. Carlson and Kneale's (2011) embedded model for the librarian fits the definition of a data scientist, while Luce (2008, p. 47) stated that data scientists could be data librarians or informationists, while Lyon (2007, p. 55) indicated that data curators may be the same as data scientists. Furthermore, the National Science Board (2005, p. 27) listed both librarians and archivists as types of data scientist.

In the 1960s, data librarians were associated with data libraries that were part of the reference services of academic and research libraries specialising in social science data (Burnhill, 1985; Martinez-Uribe and Macdonald, 2009). Martinez-Uribe and Macdonald argued that the experience of data librarians with social science data enables them to manage scientific research data. Only a few studies exist that discuss the data librarian role. Alvaro, Brooks, Ham, Poegel and Rosencrans (2011) explored the field of e-Science librarianship, which is related to the data librarian role, through the content analysis of e-Science librarian position advertisements. Their study adapted a job analysis framework employed by Kim, Addom and Stanton (2011) identifying three categories of librarians supporting e-Science: subject librarians combining traditional librarianship with limited data responsibilities; e-Science librarians with more data responsibilities; and data librarians with full data responsibilities.

Puttenstein (2011) reported that the data librarian position existed in the Netherlands where there was a need either to expand an existing staff's role or to hire new staff to focus fully on research data management. Besides Pryor and Donnelly's (2009) work cited earlier, which is a good start to identifying the data librarian responsibilities and requirements, there is no major study that articulates their role performance components. A few related works in the areas of e-Science (e.g., Alvaro et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2011) and upskilling liaison or subject librarians (e.g., Cox et al., 2012) provide a clue. The growing association of data librarians with research data management in the literature suggests that the research data management role of libraries is expected to grow in the future, requiring a new unit and specialised librarians to staff it.

Research data management support provided by librarians to academics and researchers has resulted in library services promoted as research data services. These are also known as numeric data services, electronic data services, data library, data centre and data archive (Read, 2007, p. 62). Tenopir, Sandusky, Allard and Birch (2012, p. 2) provide a definition that gives insight into what the term comprises: 'Research data services are services that address the full data lifecycle, including the data management plan, digital curation (selection, preservation, maintenance, and archiving), and metadata creation and conversion'. In other words, these are services that a librarian offers to researchers that include the informational and technical aspects and cover all phases of the research cycle. The aim is to help academics, staff and students to find appropriate data to answer their specific research questions (Read, 2007).

The discussion of research data services in the literature includes differing levels or tiers of service (Bennett, 2010; Reznik-Zellen Adamick and McGinty, 2012; Wang, 2013) and areas for research data services development (Searle, Wolski, Simons and Richardson, 2015). In terms of the levels of service, the views of other authors have been added to the Reznik-Zellen et al's (2012) tiers of service in Table 1.

| Tiers of service (Reznik-Zellen, Adamick and McGinty, 2012 | Components from other authors |

|---|---|

| Education |

|

| Consultation |

|

| Infrastructure |

|

| Key: A - Bennett (2010); B - Searle, Wolski, Simons and Richardson (2015); C - Wang (2013) | |

Reznik-Zellen et al. (2012) arrived at their tiers of service through a Web audit and environmental scan of research data management and curation of services at eighteen peer and model institutions. They provided a summarised description of each tier level of service (p. 32-33). In tier one level of service, education, 'libraries educate their communities about data management'. In tier two level of service, consultation, 'libraries consult with faculty and researchers on a variety of issues relevant to the management of research data'. Finally, in tier three level of service, infrastructure, 'libraries provide infrastructure for data management and curation to their campus communities'.

In contrast, Searle, Wolski, Simons and Richardson (2015) highlighted four areas required for research data services development: policy, infrastructure, developing knowledge and skills (of researchers in research data management) and advisory services. This suggests that the scope of roles involved in providing research data services is expanding, and there is a need to clarify what skills and knowledge data librarians will need.

The effects

The involvement of academic librarians in research data management has salutary effects on the academic and research library landscape. First, there is the mention in the literature of emerging data-related disciplines such as data science (Swan and Brown, 2008), data librarianship (Martinez-Uribe and Macdonald, 2009), and e-Science librarianship (Alvaro, Brooks, Ham, Poegel and Rosencrans, 2011; D'Ignazio, Qin and Kitlas, 2012). These are early efforts to articulate information or instructional content outlining the relevant knowledge and skills needed to adequately prepare data librarians to support research data management.

The components of a research data management role have also been conceptualised in frameworks or models. One of these is included in the participatory librarianship framework. Lankes, Cogburn, Oakleaf and Stanton (2008) described participatory librarianship as being grounded in conversation theory and seeking to organize information as a knowledge process rather than as discreet objects in a taxonomy. They identified one possible role as a cyberinfrastructure facilitator, 'a vital member of the research enterprise who works closely with researchers to identify extant tools, data sets, and other resources that can be integrated into the research process of pursuing a research objective'. Although this may cover part of the data librarian role, it is not clear that this is a complete description, particularly given the tiers of service identified by Reznik-Zellen et al. (2012), which involve other activities.

Parsons et al.'s (2011) model for managing data could be condensed to a statement including their five guiding principles for managing data: 'data should be discoverable, open, linked, useful and safe' (p. 3). There are also models for initiating and setting up a digital curation initiative such as the Digital Curation Centre (DCC) curation lifecycle model and the data curation continuum model (An, 2003; Higgins, 2008). These conceptualisations provide a good overview of what is involved in research data management. However, they do not provide an overview of the data librarian role. This is needed to not only conceptually position the role in academic and research libraries but also to inform effective practice in that role.

In 2017, Yu found that there was a skills gap for people working in data-related roles in libraries, particularly in policy development. Cox and Verbaan (2016) found that librarians, information technology staff, and research administrators had different perspectives on research services. Similarly, Bradley's 2018 comparative content analysis of library and information studies literature and that of research administrators shows little awareness of their respective roles in providing research support, suggesting that clarifying the role of a data librarian would be useful.

This leads to the question: What are the dimensions of the data librarian role in New Zealand research organizations? The larger study on which this paper is based (Ohaji, 2016) sought to answer this main research question.

This paper focuses on the following sub-questions:

- What factors influence the data librarian role in New Zealand research organizations?

- What are the performance components of the data librarian role in New Zealand research organizations? and

- What is the nature of the training needs of the library and information professionals in order to carry out the data librarian role in New Zealand research organizations?

The preliminary model for the study

Abbott's (1988) book The System of Professions provided a theoretical framework for the study. Abbott's original analysis involved three professions: law, medicine and the information profession of which library and information science is a part. His theory is a product of historical and sociological analysis which sought to address the concern of how and why professions evolve, or in his words, 'how societies structure expertise' (Abbott, 1988, p. 323).

Abbott (1988) anchored his theory on three main constructs: professional work, jurisdiction and competition. Professional work embodies tasks to be accomplished by given professionals. Jurisdiction is the claim of a profession on its work while the attempt by different professions to lay claim on existing or newly discovered tasks engender competition. Professions are seen to be interdependent so that a move by one profession affects others. The professional work construct provides a conceptual basis for investigating the data librarian role.

Abbott (1988, p. 35) described the two kinds of properties of problems that make professions vulnerable to change to be objective and subjective qualities which point to both external and internal forces that impinge on professional work. The objective foundations are technological, natural, organizational and cultural in nature. The subjective foundations refer to the mechanisms of professional work given as diagnosis, inference and treatment. Abbott (1988, p. 40) said:

Diagnosis and treatment are mediating acts: diagnosis takes information into the professional knowledge system and treatment brings instruction back out from it. Inference, by contrast, is a purely professional act. It takes the information of diagnosis and indicates a range of treatments with their predicted outcomes.

Abbott also noted that professional work in most of the professions is tied directly to a system of academic knowledge that formalises the underlying skills (p. 52).

Abbott's theory has been variously used in library and information science research. It was used by Cox and Corrall (2013) to investigate evolving academic librarian specialties; Ladner (2004) used it in combination with another theory as a theoretical framework to examine the career pattern of women librarians. Other investigations used components of Abbot's theory, including competition (Danner, 1998; Ray, 2001), and professional and jurisdiction (Freeman, 1997). In terms of research data management, the theory was used or discussed by Cox and Pinfield (2014), Pinfield, Cox and Smith (2014), and Verbaan and Cox (2014a; 2014b) in relation to the professional jurisdiction construct.

Abbott's (1988) parameter of professional work, complemented with concepts from the literature, was adapted to develop a preliminary model for this research. Abbott's three main components of the parameter of work (diagnosis, inference and treatment) formed the main elements of this model. Complementary to these were the components factors influencing the data librarian role (Soehner, Steeves and Ward, 2010) and training needs (Auckland, 2012) from the literature.

Two of the main elements of Abbott's model were contextualised based on the literature for this study. With regard to diagnosis, while the aspect of colligation retained the meaning of structuring the problems, classification was taken to mean jurisdictional mapping of the structured problems to the tiers of research data services by Reznik-Zellen, Adamick and McGinty (2012) in order to make them amenable to treatment. The two aspects of research data management duties and requirements from the literature (Kim et al., 2011) were added nuances to the component treatment. The idea was to map the duties to the requirements for treating them.

Research design

Located within the social contructivist paradigm, the study adopted a qualitative exploratory case research approach which is suitable for studying emergent practices (Voss, Tsikriktsis and Frohlich, 2002, p. 199). This approach also facilitates the exploration of a phenomenon within its context using a variety of data sources (Baxter and Jack, 2008). However, the specific case design adopted is primarily Creswell's (2007, p. 74) single instrumental case study where a researcher focuses on an issue or concern before selecting one bounded case to illustrate it.

The study was limited to New Zealand research organizations (universities and research institutes) based on a combined consideration of the gap in the literature, interest, logistics and convenience. This design fits into two of Yin's (2009) five rationales for a single-case design: whether the case is extreme, unique, representative or typical. New Zealand is a unique entity while the universities and Crown Research Institutes (the institutes) are representative examples of its research organizations. The main data collection involved semi-structured interviews.

Ethics approval for the research was received from Victoria University of Wellington's School of Information Management Human Ethics Committee. In order to test the interview protocols, exploratory data was gathered in Australia by interviewing e-research experts in two Australian universities. In the next phase, a total of forty-three data management position advertisements for librarians containing thirty-one job titles were selected between May 2012 and August 2014 from a number of USA and Australian job advertisement databases or Websites for analysis. These included the ALAJobLIST; HigherEdJobs, School of Library and Information Science, Indiana University's job list (obsolete), Australian Library and Information Association (ALIA), and the Australian National Data Service (ANDS). This data was intended to provide the employer's perspective, and included Australia and the USA in order to place the study in a broader context, given the limited number of position advertisements in New Zealand. Since the USA is one of the world's leading nations in research data management efforts (Pinfield et al., 2014, p. 3) and Australia is in the same geographical region as New Zealand, the location of the main study, and had made appreciable progress in research data management, mixing the data from Australia with those from the USA was considered useful to the study.

The main phase collected data from New Zealand research organizations. New Zealand has eight universities and eight Crown Research Institutes (institutes) (see Appendix 1). Four universities and five institutes were fully involved in this study while one researcher from an additional Institute also participated. Twenty-five respondents representing five categories of people were interviewed for this study:

- University librarians who were the prime contacts (4)

- Library and information professionals from the universities (those related to research support – 7) and the institutes (library managers or their representatives – 5)

- Institutional repository managers from two universities (2)

- Researchers involved in e-research from the universities (3) and the institutes (3)

- Information technology manager (1)

Pseudonyms are used to identify individuals, in combination with their position titles, in the discussion of the results.

Creswell's (2007) data analysis spiral was used for content analysis of the data from both phases. As is usually the case with case research, the unit of analysis is the case (Stake, 1978, p. 7). In this study, the case was the data librarian role in New Zealand research organizations. The level of analysis was primarily kept at the individual level but also included the organizational level in limited contexts where necessary.

Finally, the reviewed literature was synthesised with the views of experts and employers gathered in the exploratory phase in order to have a triangulated view (the triangulation) which provided a filter for discussing the research findings from the main phase.

Findings and discussion

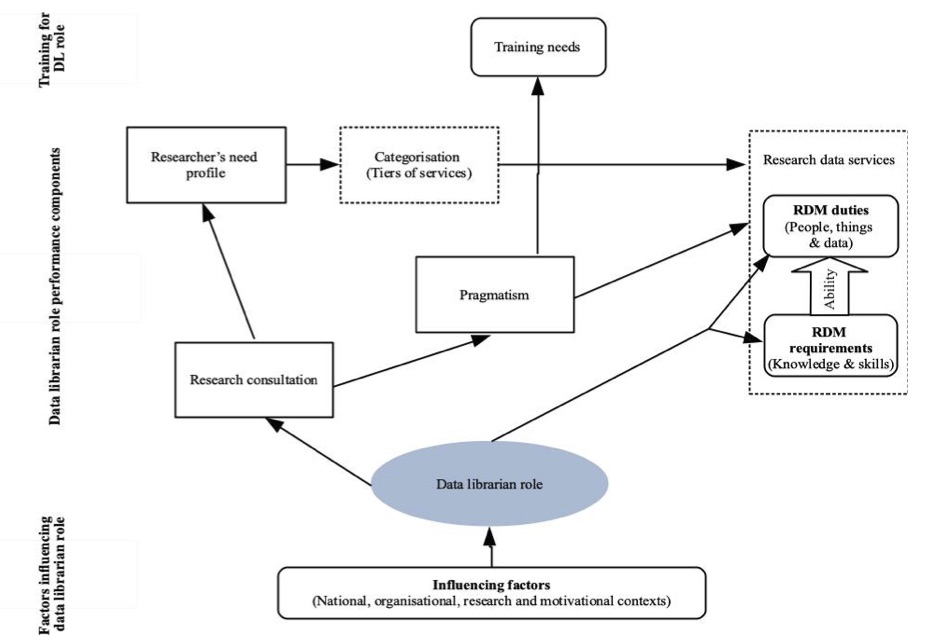

This section presents the blueprint that emerged from the study findings. Figure 2 shows the components of the model, which are individually described and discussed in relation to the findings.

Influencing factors

Influencing factors refer to the circumstances, facts, people, things, environment, etc. that may either enhance or hamper the data librarian role in a research organization. The influencing factors determine the configuration of the role in any given environment. As such, they are placed at the base of the model to underpin it. The data librarian role is situated above the influencing factors.

Four levels of influencing factors were identified from the findings of the study: the national, organizational, research and motivational contexts. These were discovered primarily from the views of the university librarians and the library and information professionals from both the universities and the institutes who participated in the study.

The national context comprises factors such as a lack of national leadership or direction in e-research and research data management, the perception of the performance-based research fund (PBRF) model as well as the activities of professional and research bodies, consortia and interest groups which stem from this lack of national leadership or direction. The lack of national leadership or direction in e-research and research data management was a common view among all categories of the participants except the e-researchers.

The organizational context comprises favourable disposition to research data management by both library and institutional leadership; the nature of research support in the research organizations; collaborations; and organizational challenges. The first was a converging point for the library and information professionals and the e-researchers as can be seen from this statement:

At the moment the library's role in the research data management support is developing. There is a clear recognition amongst leadership here at UN1 that the library does have a role to play in research data management because we, traditionally the library is the, I don't know if 'guardian' is the right word or 'gatekeeper,' but we are the organization on campus that deals the most with information management. (Eden, a library and information professional)

The research context includes influencing factors such as researchers being research data management drivers, a mandate for research data management and the researchers' discipline or areas of research. All of these factors were common to the views of university librarian, library and information professional and e-researcher participants.

Finally, factors from the motivational context occur at institutional and individual levels. At the institutional level, research data management was seen to be within the remit of academic or research libraries and there was recognition that research data management policy was a first step to e-research support. Librarians' motivation stems primarily from an understanding that research data management lies within their jurisdiction. This was common to both library and information professional and e-researcher participants.

The literature component of the triangulation also has four contexts influencing the data librarian role (based on Brandt, 2007; Newton et al., 2011; Soehner et al., 2010; Tenopir et al., 2012). Broadly, three of these contexts have similar names, although with differing elements, to those identified in the main study: national, organizational and research contexts. The main difference is that whereas the main study identified motivational context the literature has professional context. However, common elements found in both the literature and the main study are researcher interest in research data management, institutional research data management support at the administrative level, and collaborations between librarians and researchers and between libraries of different organizations. The elements of the contexts influence the data librarian role in any given environment.

Moreover, a closer look at the elements within the contexts from the findings reveal six relationships between the contexts in terms of how they may influence the data librarian role. Four pairs of contexts that may have positive influences on the data librarian role are national versus research contexts, organizational versus research contexts, motivational versus research contexts, and organizational versus motivational contexts. The other two pairs that may have negative influences on the role are national versus organizational contexts, and national versus motivational contexts.

Research consultation

Research consultation describes a discussion or meeting between a data librarian and one or more researchers in relation to their research needs or requests. The library and information professionals indicated that they engaged in research consultations with researchers to identify and address their needs. This involves an informal diagnosis of their request that is quite different from the formalised diagnosis component of the parameter of work in Abbott's (1988) theory which he described as having the dual aspects of colligation and classification.

In order to help researchers, librarians develop and work with tools such as classification and metadata schemes to describe contents of documents and/or resources including data. They also work with other tools such as data management planning tools, library guides, indexes and abstracts among other reference tools. However, they do not have any diagnostic classification system or dictionary of professionally legitimate problems in place that could facilitate research consultations. Abbott clarified that colligation aims to assemble the picture of a client's problems while classification maps this picture to a standard professional problem in order to prescribe treatment. This implies that there must be a profession's diagnostic classification system in place that is not organized as a logical (from general to specific) but a probabilistic hierarchy (from the common to the esoteric) (Abbott, 1988, p. 42). As most of the examples Abbott provided suggest, his descriptions might be truer of the medical than the library and information science professions.

Researcher's needs profile

Researcher's needs profile refers to a summarised description of what a data librarian understands through research consultation to be a researcher's needs or requests. In other words, through research consultation the researchers' needs are identified and met through research data services.

Research needs are as varied as the different researchers and their research interests and fields. The findings identified the following needs of the researchers who participated in the study: storage, management of datasets, data preservation and access, version control, information management, data catalogue, experiment records, discovery (Web) tools, implementing digital object identifiers (DOIs), supporting research projects, training on data management plans, and data registries.

Categorisation

Categorisation refers to the analysis and mapping of the researcher's needs to the levels of service so they can be met by research data services provided by a data librarian. Although librarians may find ways to understand the needs of the researchers, the interview data do not suggest that they do so in any formal way. Although different from the context of Abbott's parameter of work, it is likely that a form of classification is still needed to facilitate research data services. The inclusion of this component (categorisation) in the model is more in the context of Reznik-Zellen et al.'s (2012) tiers of service.

Pragmatism

Pragmatism means the librarian offering a practical approach to researchers' obscure problems or needs, based on his or her level of knowledge or skill as well as the opportunities and resources available within his or her service environment. The findings show that the library and information professional participants handled obscure research requests from the researchers in a number of pragmatic ways other than Abbott's (1988) inference. These are reference interview and/or research, collegial consultation, connecting researchers (referrals) with contacts or possible sources for further help and advising researchers about the lack of capacity to help them. The last approach was normally adopted as a last resort.

Kim et al.'s (2011) job analysis framework was used to organize performance components of the data librarian role which are the next two elements of the blueprint to be discussed. This framework has two parts. One is the work characteristics that refer to a worker's duties involving people, things and data. The other is the worker characteristics that refer to the requirements such as knowledge, skills and ability. While knowledge refers to a body of information to be learnt, skills refer to the know-how of applying knowledge to accomplish a task. Ability means one or more intrinsic talents that a worker possesses.

Research data management duties

Research data management duties refer to e-research support tasks involving one or a combination of people, things and data. People may be academics or researchers, students, staff, librarians, etc. Things refer to tools such as computers, data management planning tool, metadata schemes, etc. Data may involve data resources in different formats that may be needed for or generated from research.

The findings reveal some people- and thing-related duties but no direct data-related duty. The people-related duties are: provide advice on data management; liaison; organize training; and help with research needs. The thing-related duties comprise assistance with tools, applying metadata standards, and managing systems. The non-mention of data-related duties may be related to the general understanding of the practitioner participants that the library's role in research data management is limited to educational and advisory functions.

However, the triangulation (perspectives from the literature, experts and employers) have more people and thing-related duties and are only different from the findings above in terms of data-related duties. The data-related duties within the perspectives are: audit data, analyse data, collect data, present data and store data. This shows that the duties of a data librarian may depend on the extent of his or her library's involvement in research data management.

Research data management requirements

Research data management requirements are competencies required for the e-research support tasks such as knowledge, skills and ability. As they emerged from the study, knowledge requirements comprise: technical knowledge; research and/or scholarly publication; metadata; background in information literacy and liaison; science and statistics; researchers; and data. Skill requirements were discovered to be in such areas as citation tools, keeping up to date, research and searching, training and data literacy, data, database, project management and people (communication and interaction).

In terms of ability, someone in a data librarian role was expected to be able to communicate, to relate, to use technology, to liaise and to catalogue. The findings show that either or both knowledge and skills provide the ability to accomplish given tasks. For instance, knowledge of researchers (their needs) and possessing training and data literacy skills provide the ability to communicate with (teach) the researchers. Also, a background in liaison with people skills will provide the ability to liaise, relate and communicate with the researchers.

The triangulation has similar requirements for the role. Those discovered to be common provide some examples. Knowledge required includes: technology and standards (including metadata); researchers' needs and available resources in particular disciplines; research and its support; and research data and data lifecycle, curation and management. The required technical skills include teaching or instruction (including data literacy), technology and standards (including metadata), project management, reference and data audit interviews, computer literacy, and data. The non-technical skills include interpersonal and communication, team and collaboration, and administration. The most commonly mentioned ability was the ability to work independently and collaboratively (in a team).

Research data services

Research data services are the services provided by data librarians in response to their clients' research data management needs or problems for which they are expected to have the requisite knowledge and skills. Research data services translate to reducing the categorised needs of a researcher to specific research data management duties which require the abilities provided by requisite knowledge and skills to handle them (see Table 2).

The findings show that the research participants who were practitioners (university librarians and library and information professionals) from about two-thirds of the research institutions favoured subject and/or liaison librarians for the data librarian role as a part of a hybrid role. This approach is supported in the literature (e.g., Cox, Verbaan and Sen, 2012; Bresnahan and Johnson, 2013). The alternative approach of a data librarian role as a specialist individual role was mentioned in two instances. First, as a short-term role for training subject librarians in terms of the transfer of skills. Second, the role may exist in the future (or now) where the research data management support role grows and there is an actual need for it. It is important to note that the position advertisement component of the triangulation reveals the following forms in which the role exists: general non-management, subject-related, hybrid, and management positions. Thus, the extent and nature of library involvement in research data management may determine how the role may exist in a research organization.

The findings also show that support services for data and research data management distinguish the data librarian role from the generalist research support librarian role. This suggests that the data librarian role is distinct from general research support, and therefore merits unique attention.

Training needs

Training needs refer to the gaps in the skills and knowledge for the data librarian role in relation to research data services which can be filled with appropriate professional development. Researchers' needs profiles and research data services are seen to constitute the basis for identifying the training needs for prospective data librarians.

This study identified the following training needs for the data librarian role:

- Research (understanding the areas around research including research cycles, research project management and e-research)

- Technology (understanding basics around technology, available tools, what needs to be done with high performance computers, and engaging with ever-changing technologies)

- Information management (understanding of information governance and access principles or [international or existing] standards, basics regarding domains, information management and informatics, and understanding interchange standards)

- Research data (research data, data collection and its purpose, research data curation and management, data literacy, machine discovery, and business analysis)

- Metadata (metadata standards)

- Organizational knowledge (including policies that govern various aspects of the organization)

- Customerr elationship (including customer training)

- Interpersonal and communication skills

It is one thing to discover the training needs for a role and another thing to devise suitable ways to meet those needs. The findings reveal two broad training options for the role: personal opportunities and organizational opportunities. Personal opportunities include: working with librarians and other professionals who are experts in the area; being exposed to other support services in the area; conducting research with technology for hands-on experience; personal reading; talking to researchers about how they use data, the practices they use to manage data, and what sort of tools or programmes they use.

Organizational opportunities are provided by the research organizations and include organizational support for training in the form of sponsored formal learning such as courses or training programmes in a university, in-house training, or bringing in an expert singly or in partnership with other libraries. Other options include exchange course arrangements with other libraries or other organizations doing research data management; sponsorship to attend professional meetings such as conferences and workshops; professional collegial or peer support to someone new to the role; and learning on the job through pilot data management projects and conferences. Read (2007, p. 64) and Simons and Searle (2014, pp. 10-13) discussed some of these options. However, it must be noted that most of the practitioner participants in the study preferred librarians to learn on the job through informal opportunities.

Moreover, the experts within the triangulation also favoured options such as conferences and professional networks, training courses, online courses, self-learning, and project experience which can be summed up as learning on the job. Corrall, Kennan and Afzal (2013, p. 662) revealed that eight libraries in New Zealand included in their study favoured the learn on-the-job option for current staff education on research data management support. The training option preferred by prospective trainees is a very important consideration in this respect (Bresnahan and Johnson, 2013; Johnson and Bresnahan, 2015) since it enhances convenient learning in a secure environment that facilitates learning, understanding and learning outcomes.

Main areas of the study

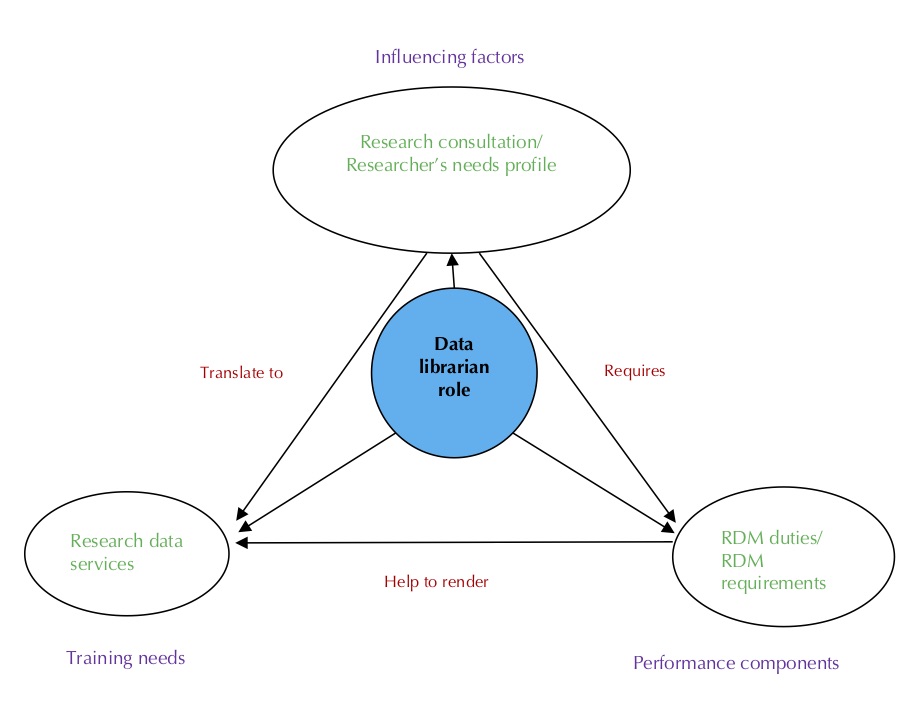

The main areas of the study around which the blueprint was developed are related to one another. They are the influencing factors, performance components and training needs for a data librarian role. Within the model, they involve five components, shown in Figure 3: research consultation, researcher's need profile, and research data services, plus the two performance components (research data management duties and research data management requirements).

Driving the relationships are researchers' needs which belong to the research context of factors influencing the data librarian role. Researchers are seen to be the drivers of research data management through their research areas, interests and needs. The researchers' needs determine and translate to research data services which require the performance components of research data management duties and requirements in order to be addressed. While the performance components are part of the data librarian role dimensions, within the research data services context they help to reveal the requirements that a prospective data librarian may be lacking. These are his or her training needs.

However, there are other relationships between the main aspects of the study that are not easily seen from the model. For instance, the decision on the type and design of training to address the identified training needs depends on organizational factors such as the favourable disposition of organizational and library leadership to research data management.

Summary of the components of the models

The blueprint shows that the influencing factors on the data librarian role are at the base of the model, similar to a foundation at the base of a building. Thus, the data librarian role is situated directly on top of the influencing factors. Just above the role is research consultation which is the core and starting point of his or her activities in the role. A product of research consultation is the researcher's needs profile that could be subjected to categorisation in preparation for research data services. However, obscure problems emerging from research consultations need to be dealt with pragmatically.

However, both the categorised researcher's needs profile and pragmatically assessed needs are addressed through research data services. These translate to the duties of the data librarian for which s/he requires the ability from relevant knowledge and skills. It is what s/he lacks in terms of knowledge and skills within the background of the categorised researcher's needs profile and pragmatically assessed needs that shows what his or her training needs may be.

The fit of the data librarian role blueprint

The needs of the researchers imply researchers' need profiles such as could arise from a research consultation. Table 2 aligns these to the Reznik-Zellen et al. (2012) tiers of service and maps them to the type of research data management duty and the corresponding research data management requirements. Note that the research data management requirements' columns include data from the literature, experts and employers' perspectives.

| Consultation (Research Needs) | Research needs' description | Categorisation (Tier of Service) | Research data management duties (Type) | Research data management requirements | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Skills | ||||

| Storage | Includes software versions; software simulation codes with their parameters; Artefacts; Disk space | Infrastructure | Data or things | Technology and standards (including metadata); Software; Research data management | Technology and standards (including metadata); Software; Research data management |

| Management of datasets | Intermediate or working datasets | Infrastructure | Data | ||

| Data preservation and access | Description of data for re-use | Infrastructure | Data | ||

| Version control | Use system to track changes on a file | Infrastructure | Things | Software; Computer | Information technology; Technical |

| Information management | Organizing information through its cycle | Infrastructure | Things | Background in information professions | Information management |

| Data catalogue | Metadata for data | Infrastructure | Things | Background in librarianship; Data | Metadata; information |

| Experiment records | Searchable electronic holding for curated experiment records | Infrastructure | Things | Technology and standards (including metadata) | Technology and standards (including metadata) |

| Discovery (Web) tools | For visualisation | Infrastructure | Things | Technology (Web tools and visualisation platforms) | Technology (Web tools and visualisation platforms) |

| Implementing digital object identifiers | For datasets and resources connected to dissertation to make them citeable and accessible | Consultation | People | Background in librarianship; Digital object identifiers | Metadata; Liaison; Digital object identifiers |

| Support research projects | Involvement in research projects; Working with Research Office and IT Services to coordinate data storage | Consultation | People | Research; Project management | Research; Project management; People |

| Training on data management plan | For one or more people | Education | People | Teaching or pedagogy; Research data management | Data literacy; Research data management; Teaching |

| Data registry | List of data repositories | Education | Things | Information management | Organizational |

Issues with the data librarian role blueprint

Two issues may be raised by the exemplar and require clarification. First, its focus on the e-research and research data management support may imply that it is intended for a single-role position which may not permit embedding it to another role. On the contrary, the idea is to provide a blueprint for the aspects of the data librarian role which could be performed in any number of ways. For instance, in most of the case-study institutions subject librarians or their equivalents were favoured for the role. As a hybrid role, subject librarians need to conceptually understand what is expected of them. In this way, they are better prepared for the role. Moreover, the employers' perspective shows that the role can take a number of forms.

Finally, the model lacks any component regarding the professional background or qualifications of prospective data librarians. It is taken for granted that the role is within the remit of qualified librarians. However, this is implied by the motivational context factor 'professional interest, background and experience'.

Implications for research and practice

This paper has highlighted the blueprint that embodies the main findings of a study on the data librarian role in New Zealand research organizations. The findings have implications for research and practice. First, the blueprint is a major contribution to theory and practice. It enhances a theoretical understanding of the academic and research librarians' role in research data management. Abbott's 1988 theory's parameter of professional work provided a prism for analysing the data librarian role although it has limitations. The blueprint represents an improvement on the theory with the nuanced aspects of its diagnosis and treatment components and an additional consideration of the influencing factors as well as the training needs for the role which were not found in Abbott's theory. The blueprint grounds the data librarian role within the factors influencing it. This is important as roles in any organization are shaped by the influencing factors or contexts within and around it. These factors need to be understood in order to take advantage of the positives and deal with the challenges that could hamper success in a role such as the data librarian role. Also of note is the fact that it shows that pragmatism rather than Abbott's theory's hypothesis component is required in prescribing treatment to the research data management needs of the researchers.

The blueprint confirms that e-research and research data management support is a unique professional role within the academic and/or research librarianship landscape. It facilitates an interested practitioner's understanding of the data librarian role for effective practice. By positioning the research data services space around the responsibilities and requirements for the role it provides a background for identifying the training needs of any prospective data librarian. The blueprint may form the basis for the library research community to articulate or conduct research, instruction and learning in the research data management area. Being at a very high level the blueprint can be readily adapted to investigate other professional, especially librarian, roles.

In addition, the findings of the study also showed that the majority of the research organizations favoured subject or liaison librarians to play the data librarian role in New Zealand research organizations. As there are limited studies (Auckland, 2012; Corrall et al., 2013) related to subject and/or liaison librarians and research data management in New Zealand, further studies in this area are suggested. The findings of this study provide a foundation for surveying subject and/or liaison librarians in all the universities and their equivalent in all the institutes within the country. The focus of the study should be to explore their levels of comfort or anxiety surrounding research data management, the knowledge and skills they already possess and what else they need, and what training options they prefer. The findings could extend those of this study and facilitate the development of training modules for librarians in research data management at the research organizations as well as the Information Studies programme at Victoria University of Wellington.

Finally, the findings of the study showed that a specialist individual data librarian role can exist presently as an interim position for the training of subject librarians or in the future when research data management responsibility grows and there is actual need for that. Getting an interim specialist data librarian to train subject and/or liaison librarians is a challenge for the library management of various research organizations. Two main options may be considered in relation to the urgency of need and cost effectiveness of each available option. One option is to develop and use a staff member and the other option is to hire an expert from without the organization. In the first option, a member of staff could be provided with the resources for self-development or sponsored to learn through short-term courses or relevant conferences or a partnership programme with an institution that is far-advanced in research data management support. However, in the second option, an expert could be hired or borrowed short-term from partnering organizations to help in the role.

Limitations of the study

The limitations of the study are related to the nature and design as well as the resources for the study. This study employed an exploratory case research approach combined with semi-structured interviews as the main source of data collection. Leedy and Ormrod (2013, p. 141) observed that the major weakness of a single case design, typical of qualitative methodology, is that the findings cannot be generalised to situations outside the study. However, Yin (2009, p. 38) argued that there is a difference between statistical generalisation associated with deductive approaches and analytic generalisation in case studies which is at the point of theory.

Two limitations may be considered in relation to resources for the study. First, the literature reviewed or considered for the study was limited to publications in English. Some literature in other languages that could have been useful to the study might have been missed. However, there is the confidence that sufficient literature was reviewed for the study so that the omissions did not affect the study in any negative way. Second, interviews (Pickard, 2007, p. 181) and purposive sampling (Liamputtong and Ezzy, 2005, p. 49) guarantee rich and in-depth data, although the latter author added that the detail and breadth required in research need to be balanced with the resources of time and money available to the researcher. While the money and time available for this were limited, it is to be noted that the available resources have been sufficient for the purpose of the study.

Finally, Creswell (2007) emphasised that deciding on a case and its boundaries is challenging. In this study, research data management is considered to be a big space accommodating different data roles (e.g., data creators, data managers and data scientists), which may be misconstrued by some people as being restricted to the data librarian role. However, we do not claim that the data librarian has a sole stake in or is synonymous with research data management.

Conclusion

Research data occupy a central place in the research enterprise in terms of its sustainability and reproducibility so that a natural and reasonable course of action is to manage them. The mission, role and experience of academic and research libraries as information organizations over the years aptly position them as interested parties. A new role within their background has emerged which has been articulated as the data librarian role.

This paper highlighted an exemplar for the data librarian role that emerged from a recent study which provides the conceptual ground and overview for the role. In addition to the benefits of the exemplar to the academic library and information practitioners' community, the exemplar also contributes to the literature and conversation within the academic and/or research library research community around the involvement of academic and research libraries and librarians in research data management.

Acknowledgements

This research would not have been possible without the participation of the interviewees, who spoke freely and openly about their views. We would also like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments and encouragement.

About the authors

Isaac K. Ohaji is a senior librarian and the Technical Services Librarian in the Medical Library, College of Medicine, University of Nigeria, Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu, Nigeria. His research interests focus on research data management, academic librarianship, library profession, scholarly communication and digital libraries. He can be contacted at isaac.ohaji@unn.edu.ng

Brenda Chawner is a senior lecturer in the School of Information Studies, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. Her research interests focus on access to information, information policy, and free/libre open source software. She can be contacted at brenda.chawner@affinity.co.nz

Pak Yoong is an Emeritus Professor in the School of Information Management, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. His research interests focus on digital inclusion for older people and digital leadership. He can be contacted at pak.yoong@vuw.ac.nz

References

- Abbott, A. (1988). The system of professions: an essay on the division of expert labour. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Allard, S., Mack, T. R. & Feltner-Reichert, M. (2005). The librarian's role in institutional repository: a content analysis of the literature. Reference Services Review, 33(3), 325-336.

- Alvaro, E., Brooks, H., Ham, M., Poegel, S. & Rosencrans, S. (2011). E-Science librarianship: field undefined. Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship, (No. 66).

- An, X. (2003). An integrated approach to records management. The Information Management Journal, 37(4), 24-30.

- Ashley, K. (2012). Research data and libraries: who does what. Insights, 25(2), 155-157.

- Atkins, D. E., Droegemeier, K. K., Feldman, S. I., Garcia-Molina, H., Klein, M. L. Messerschmitt, D. G., ... Wright, M. H. (2003). Revolutionising science and engineering through cyberinfrastructure: report of National Science Foundation Blue-Ribbon Advisory Panel on Cyberinfrastructure. Retrieved from National Science Foundation: https://www.nsf.gov/cise/sci/reports/atkins.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2OZwJ9j)

- Auckland, M. (2012). Re-skilling for research: an investigation into the role and skills of subject and liaison librarians required to effectively support the evolving information needs of researchers. London: Research Libraries UK. Retrieved from https://www.rluk.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/RLUK-Re-skilling.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/33XuHe8).

- Awre, C., Baxter, J., Clifford, B., Colclough, J., Cox, A., Dods, N., ... Zawadzki, M. (2015). Research data management as a “wicked problem.” Library Review, 64(4/5), 356-371.

- Baxter, P. & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13(4), 544-559.

- Bell, G. (2009). Foreword. In T. Hey, S. Tansley & K. Tolle (Eds.), The fourth paradigm: data-intensive scientific discovery (pp. 177-183). Redmond, WA: Microsoft Research.

- Bennett, T. B. (2010). Research data services at Singapore Management University: engagement summary report. (Research College Library, Paper 5). Retrieved from http://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/library_research/5/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2PqR9qM).

- Borgman, C. L. (2010). Research data: who will share what, with whom, when, and why? Paper presented at the Fifth China-North America Conference, Beijing, China. Retrieved from http://works.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1237&context=borgman

- Borgman, C. L. (2011). The conundrum of sharing research data. Journal of American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(6), 1059-1078.

- Bradley, C. (2018). Research support priorities of and relationships among librarians and research administrators: a content analysis of the professional literature. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 13(4), 15-30.

- Brandt, D. S. (2007). Librarians as partners in e-research: Purdue University Libraries promote collaboration. College & Research Libraries News, 68(6), 365-396. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.68.6.7818

- Bresnahan, M. M. & Johnson, A. M. (2013). Assessing scholarly communication and research data training needs. Reference Services Review, 41(3), 413-433. Retrieved from http://scholar.colorado.edu/libr_facpapers/7

- Burnhill, P. (1985). Towards the development of data libraries in the UK. Paper written for the Committee of Librarians and Statisticians. Retrieved from http://www.era.lib.ed.ac.uk/bitstream/1842/2510/1/devdatlibuk.PDF.

- CARL Data Management Sub-Committee (2009). Research data: unseen opportunities. Retrieved from http://carl-abrc.ca/uploads/pdfs/data_mgt_toolkit.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2RAiKIG)

- Carlson, J. & Kneale, R. (2011). Embedded librarianship in the research context: navigating new waters. College and Research Library News, 72(3), 167-170.

- Case, M. M. (2008). Partners in knowledge creation: an expanded role for research libraries in the digital future. Journal of Library Administration, 48(2), 141-156.

- Colley, S. (2003). Nursing theory: its importance to practice. Nursing Standard, 17(46), 33-37.

- Corrall, S. (2012). Roles and responsibilities: libraries, librarians and data. In G. Pryor, (Ed.), Managing research data (p. 105-133). London: Facet Publishing.

- Corrall, S., Kennan, M. A. & Afzal, W. (2013). Bibliometrics and research data management services: emerging trends in library support for research. Library Trends, 61(3), 636-674.

- Cox, A. M. & Corrall, S. (2013). Evolving academic library specialties. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(8), 1526-1542.

- Cox, A. M. & Pinfield, S. (2014). Research data management and libraries: current activities and future priorities. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 46(4), 299-316.

- Cox, A. M., Pinfield, S. & Smith, J. (2014).Moving a brick building: UK libraries coping with research data management as a 'wicked' problem. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 48(1), 3-17.

- Cox, A., Verbaan, E. & Sen, B. (2012). Upskilling liaison librarians for research data management. Ariadne, 70. Retrieved from http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue/70/cox-et-al/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2OXVK4G).

- Cox, A., Verbaan, E. & Sen, B. (2014). A spider, an octopus, or an animal just coming into existence? Designing a curriculum for librarians to support research data management. Journal of eScience Librarianship, 3(1), 15-30. Retrieved from http://escholarship.umassmed.edu/jeslib/vol3/iss1/2/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2PnQ82L).

- Cox, A. & Verbaan, E. (2016). How academic librarians, IT staff, and research administrators perceive and relate to research. Library and Information Science Research, 38(4), 319-326.

- Creswell,J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Danner, R. A. (1998). Redefining a profession. Law Library Journal, 90(3), 315-356.

- D'Ignazio, J., Qin, J. & Kitlas, J. (2012). Using internship experience to evaluate a new program in eScience librarianship. In iConference '12 Proceedings of the 2012 iConference,Toronto, Ontario, Canada — February 07 - 10, 2012 (pp. 601-602). New York, NY: ACM. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2PnBGrG

- Fargion, S. (2007). Theory and practice: a matter of words, language, knowledge and professional community in social work. Social Work and Society International Online Journal, 5(1), 62-77. Retrieved from http://www.socwork.net/sws/article/view/121/537

- Freeman, M. (1997). Is librarianship in the UK a true profession, a semi-profession or a mere occupation? New Library World, 98(2), 65-69.

- Gold, A. (2007a). Cyberinfrastructure, data, and libraries, part 1: a cyberinfrastructure primer for librarians. D-Lib Magazine, 13(9/10). Retrieved from http://www.dlib.org/dlib/september07/gold/09gold-pt1.html

- Gold, A. (2007b). Cyberinfrastructure, data, and libraries, part 2: libraries and the data challenge: roles and actions for libraries. D-Lib Magazine, 13(9/10). Retrieved from http://www.dlib.org/dlib/september07/gold/09gold-pt2.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3504kFS)

- Goldenberg-Hart, D. (2004). Libraries and changing research practices: a report of the ARL/CNI Forum on e-Research and cyberinfrastructure. ARL: A Bimonthly Report on Research Library Issues and Action from ARL, CNI, and SPARC, (No. 237), 1-5. Retrieved from https://www.cni.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/arl-br-237.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2s2y3PO)

- Green, A., Macdonald, S. & Rice, R. (2009). Policy-making for research data in repositories: a guide (Version 1.2). Retrieved from http://www.disc-uk.org/docs/guide.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2LxRXcf)

- Heidorn, P. B. (2011). The emerging role of libraries in data curation and e-Science. Journal of Library Administration, 51(7-8), 662-672.

- Henty, M. (2008). Dreaming of data: the library's role in supporting e-Research and data management. Paper presented at the Australia Library and Information Association Biennial Conference, Alice Springs, NT Australia. Retrieved from http://apsr.anu.edu.au/presentations/henty_alia_08.pdf. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2OXs0VO

- Hey, T. & Hey, J. (2006). E-Science and its implications for the library community. Library Hi Tech, 21(4), 515-528.

- Hey, T. & Trefethen, A. E. (2003). The data deluge: an eScience perspective. In Fran Berman, Geoffrey Fox and Anthony J. G. Hey (Eds.). Grid computing: making the global infrastructure a reality (pp. 809-824). Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Retrieved from http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/257648/1/The_Data_Deluge.pdf.

- Higgins, S. (2008). The DCC curation lifecycle model. The International Journal of Digital Curation, 1(3),134-140.

- Hunter, J., Cook, R. & Pope, S. (Eds.). (2004). E-research middleware: the missing link in Australia's e-research agenda. (Discussion Whitepaper on E-Research Middleware for submission to The Commonwealth of Australia Department of Education, Science and Training National Research Infrastructure Taskforce). Retrieved from http://itee.uq.edu.au/~eresearch/papers/eResearchMiddleware.pdf. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20120424182011/http://itee.uq.edu.au/~eresearch/papers/eResearchMiddleware.pdf)

- Jankowski, N. W. (2007). Exploring e-Science: an introduction. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(2), 549-562

- Johnson, A. M. & Bresnahan, M. M. (2015). DataDay!: designing and assessing a research data workshop for subject librarians. Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication, 3(2), eP1229, 1-19.

- Joint, N. (2007). Data preservation, the new science and the practitioner librarian. Library Review, 56(6), 451-455.

- Jones, E. (2008). E-Science talking points for ARL deans and directors. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries.

- Kim, Y., Addom, B. K. & Stanton, J. M. (2011). Education for e-Science professionals: integrating data curation and cyberinfrastructure. The International Journal of Digital Curation, 1(6), 125-138.

- Ladner, S. J. (2004). Career patterns of women librarians who were early adopters of the Internet. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Florida State University, Florida, U.S.A. Retrieved from http://purl.flvc.org/fsu/fd/FSU_migr_etd-3322

- Lankes, R. D., Cogburn, D., Oakleaf, M. & Stanton, J. (2008). Cyberinfrastructure facilitators: new approaches to information professionals for e-research. Paper presented at the Oxford e-Research Conference, Oxford e-Research Centre, University of Oxford. Retrieved from https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:392876bd-5d9f-40b0-822f-269332643e6b

- Leedy, D. P. & Ormrod, J. E. (2013). Practical research planning and design. Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc.

- Lewis, M. (2010). Libraries and the management of research data. In S. McKnight, (Ed.), Envisioning future academic library services initiatives, ideas and challenges (pp. 145-168). London: Facet Publishing. Retrieved from http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/11171/1/LEWIS_Chapter_v10.pdf.

- Liamputtong, P. & Ezzy, D. (2005). Qualitative research methods (2nd ed). South Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press.

- Lucas, D. (2011). Faculty in-service: how to boost academic library services. Collaborative Librarianship,3(2), 117-122.