Short paper

A life goals perspective on the information behaviour of elderly adults

Zinaida Manžuch and Elena Maceviciute.

Introduction. The paper offers a Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (SST) perspective on the information behaviour of the elderly. It goes beyond biological aging and could usefully explain motives, preferences, influential factors in their information behaviour.

Method. A thematic meta-analysis was performed to study the research on the information behaviour of the elderly adults published over the last decade (2010-2019).

Analysis. The analysis is focused on manifestations of emotional regulation aimed at information behaviour (needs and motives, information seeking and use) of the elderly.

Results. In everyday life situations the elderly prioritise emotional regulation goals, which are the main drive of information activities. Social networks, a safe and familiar environment, and positive emotional experience are influential factors shaping the needs, motivation and ways the elderly seek for and use information. Emotional regulation goals may also limit information seeking and cause distortions in making sense of information.

Conclusions. Differently from other approaches to information behaviour of the elderly, SST does not limit the study to biological aspects of aging and offers rich explanations of social and psychological aspects of their lives. It can be complementary to other approaches and provide an explanatory aspect to many descriptive studies, e.g., explain the extensive use for social networks for information seeking, avoidance of certain information activities, or reluctance to learn new internet search skills.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irisic2005

Introduction

The information behaviour of elderly people is a visible theme in social sciences with abundant and rich research data. Various aspects of information needs, seeking and use, including health information, information and communication technology (ICT) adoption, migration and social exclusion were analysed. The research has been developed in health, gerontology, computer science and information systems, sociology, information science and other related fields. Yet, often the elderly adults are approached from the perspectives of the declining abilities or social/digital exclusion and the need for compensation or care. This is reflected in purely age-based typologies associated with different ability levels as third or fourth age (Asla and Williamson, 2015), 'young old', 'older old' and 'the oldest old' (Enwald et al., 2017, etc.). Other research (e.g., Niemelä et al., 2012) takes richer everyday lifestyles perspectives but focuses on the observable information practices without connecting them to the transformations taking place with aging.

In this paper we offer a theoretical perspective that goes beyond traditional approaches to aging and considers changes in life goals usefully explaining information behaviour of the elderly. We aim to analyse how emotional regulation life goals of the elderly and strategies chosen to pursue them shape components of information behaviour. The research questions we have asked are:

- How does emotional regulation goal manifest in information behaviour of the elderly people?

- What are the opportunities and obstacles brought by emotional regulation to information activities of the elderly people?

- What are the benefits of using SST in information behaviour research?

For this purpose, we perform a meta-analysis of research on the information behaviour of the elderly adults published in 2010-2019. The information behaviour research is approached from the perspective of Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (SST) (Carstensen et al., 2003). The theory studies social, emotional and cognitive changes in behaviour that depend on individual perceptions of life-time available in future.

So far, we have identified only one study by Yang (2019) applying SST for analysing health information behaviour of elderly persons. This study focused on the connection between health information literacy and intention to share health rumours in the elderly adults. We apply this approach to explore the potential of SST in helping to understand diverse information behaviour of the elderly.

Theoretical framework and methods

SST argues that depending on the perception of time left in life, individuals prioritise between two major life goals that could be broadly referred to as knowledge acquisition and emotional regulation (Carstensen et al., 1999):

- Knowledge acquisition goals are aimed at preparing for the future and investing in activities that could lead to the best use of future possibilities or overcoming future obstacles that are quite uncertain in present.

- Emotional regulation goals are focused on the present and activities that could bring immediate emotional satisfaction, provide a sense of meaning and positive feelings without postponing them to the future.

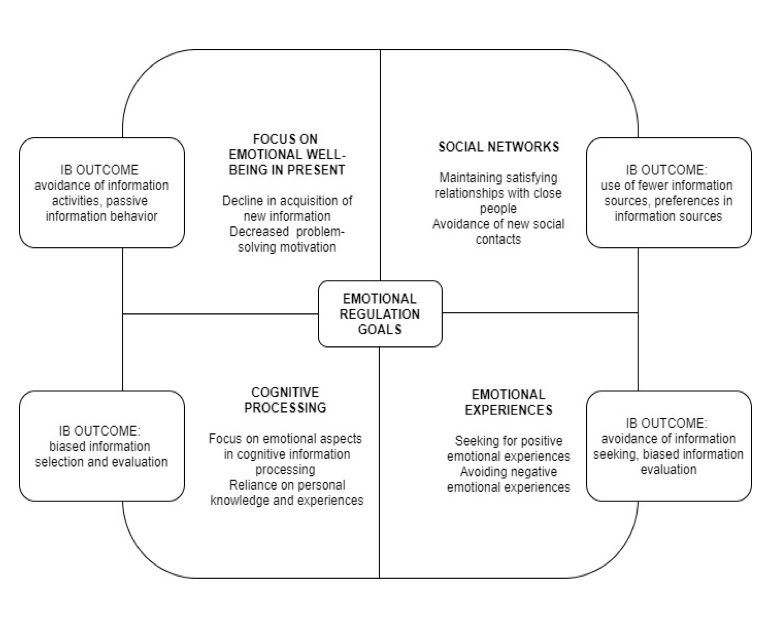

- The knowledge/emotion distinction does not mean that emotional or knowledge elements are absent in specific goals, rather it indicates the predominant orientation of the individual (Carstensen et al., 1999). There are several ways of pursuing these goals with varying implications for different aspects of information behaviour (Löckenhoff and Carstensen, 2004; Yang, 2019) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Emotional regulation goals and outcomes to information behaviour (IB)

With limited perceived time ahead and the focus on emotional well-being of the present, people become less interested in gathering new information or investing in activities that would bring satisfaction in future. It causes disinterest and lack of engagement in purposive information activities, avoidance and delegation of decision-making to others. Consequently, elderly people spend less effort and time on reviewing and critically assessing information before making decisions than their younger counterparts (Löckenhoff and Carstensen, 2004).

Perceived available time in future also affects social interactions. The focus shifts to maintaining satisfying relationships with few people who are well-known and trusted. It increases the chance for positive experience, assistance in overcoming difficulties, and a sense of social belonging. Usually, people become less prone to establishing new contacts and expanding social networks than in case of the focus on knowledge acquisition. So, the information is obtained from familiar and trusted sources (Löckenhoff and Carstensen, 2004).

In search for satisfying emotional experiences people prioritize positive information over negative and, in general, avoid enduring negative experiences (Carstensen et al., 2003). Löckenhoff and Carstensen (2004) noted the negative effect of this older adults’ feature on health information behavior when unpleasant but crucially important health information was ignored. However, the elderly people respond to positively formulated health recommendations (English and Carstensen, 2015).

When cognitive processing serves emotional regulation, people predominantly identify, remember and use personally significant emotional information (e.g., thoughts, feelings, personal judgements, experiences). Yang (2019) observed that emotional regulation focus was negatively related with health information literacy and positively with an intention to share health rumours. Löckenhoff and Carstensen (2004) noted that in decision-making the elderly increasingly relied on their prior knowledge and past experiences. Although this strategy could be useful, together with prioritized positive information it leads to biased evaluation and the lack of critical assessment of information (Löckenhoff and Carstensen, 2004).

Appropriating the SST conception of the life goals, we searched for the presence of emotional regulation in previous information behaviour research. SST was applied to different components of information behaviour as expressed in Wilson’s model (1997) that provides a broad conceptualisation of processes and elements of information behaviour. Wilson’s model contains 6 elements. Three of them indicate stages in information behaviour. We use them to explain how emotional regulation goals manifest in information behaviour:

- Context of information needs - according to Wilson (1997), information needs are directly unobservable subjective experiences, but we can deduce needs and underlying motives by studying reports of information seekers and their actual information activities. In this study, we focus on observable manifestations of information needs and their psychological motives identified by other researchers.

- Information-seeking behaviour includes various modes of searching and information acquisition and variety of preferred channels and sources to obtain information.

- Information processing and use explains how acquired information is integrated into the existent pool of knowledge, beliefs and values of the individual. It goes beyond the process of seeking but "provides the link back to the need arousing situation of the person-in-context" (Wilson, 1997, p. 569).

Three remaining elements cover activating mechanisms and intervening variables that stimulate or hinder each information behaviour stage. SST deals only with psychological aspects of information behaviour, so we concentrate our analysis on them.

The main data sources for this study were research papers focused on the information behaviour of the elderly individuals. Due to abundant research publications on the topic only research published in the last decade (2010-2019) was considered. Research papers that empirically studied the elderly people (not involving research of relatives, caregivers etc.) were selected. We also considered only papers published in English.

The papers were identified by using Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar.

| Search query* / Search engine | Scopus | Web of Science | Google Scholar |

|---|---|---|---|

| elderly AND "information behaviour" | 24 | 2 | 1360 |

| old AND "information behaviour" | 54 | 19 | 6590 |

| senior AND "information behaviour" | 22 | 3 | 2990 |

Search results were examined, and irrelevant papers were excluded by manual analysis in two stages. First, we removed occasional results with:

- inappropriate meaning of search terms. For instance, "senior" showed differences in position, rank or status (e.g. senior executive, senior manager), while "old" indicated age in general (e.g., 15 years-old).

- occasional co-occurrence of search terms (e.g., "sociodemographic information, behaviour and lifestyle").

- occasional occurrence of search terms only in a publication’s reference list.

At the second stage, we reviewed the abstracts and excluded papers that did not examine or at least partly refer to different manifestations of information behaviour (e.g., treatment or medical help seeking behaviour etc.). Finally, 46 papers were selected for further analysis.

We coded the material applying the analytical framework in Figure 1 and used thematic analysis of the data.

Findings: features of the analysed studies

Forty-six publications, selected for analysis, include studies in various disciplines. We analysed the affiliations of authors and grouped them according to OECD (2007). Revised field of science and technology classification to show the disciplinary landscape of the research (see Table 2).

| Author's affiliations according to fields and sub-fields of science** | No. of studies |

|---|---|

| Medical and health sciences: health sciences (13), clinical medicine (14) | 20 |

| Social sciences: information sciences* (10), sociology (6), media and communications* (4), psychology (3), library and information science* (3), law (1), economics and business (2), public administration (1), education (2), social and economic geography (1) | 32 |

| Natural sciences: computer sciences (4), mathematics (1) | 5 |

| *In OECD manual information sciences and library sciences are categories of a sub-field "Media and communications". ** No. of affiliations is higher than no. of studies because several authors affiliated to institutions working in different disciplines may co-author one study | |

About half of the papers contained authors affiliated to one subfield (24), while 17 showed affiliations to two and five - to three subfields. It indicates that information behaviour of the elderly is an interdisciplinary research field.

Many studies used qualitative research designs (26), 19 - quantitative and one - mixed research approaches. In qualitative studies interviews (22), observation (4), focus groups (4), informal conversation (2), content analysis (1) methods were used. The quantitative ones included questionnaire surveys (15), one randomized controlled trial, one process tracing, one controlled user experiment. One mixed methods study combined a questionnaire survey with interviews, focus groups and storytelling.

Fourteen papers focused on health information behaviour, nine on various information behaviour aspects in digital technologies adoption and use, nine on everyday life information behaviour, and two analysed information behaviour in experimental settings. Interestingly, 12 studies considered challenging situations where problem-solving behaviour was required. These studies included dealing with pains and deciding on medical treatment, problem solving issues caused by immigration and natural disasters.

Findings: main themes according to SST dimensions

Analysis of publications produced 14 main themes related to emotional regulation goals and information behaviour components (see Table 3).

| SST dimensions | Information needs and motives | Information seeking | Information processing and use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focus on emotional well-being in present | Focus on well-being: in general (Niemelä et al., 2012; Asla and Williamson, 2015; Boonchuay, 2017; Kim and Choi, 2014; Zou and Zhou, 2014): healthy lifestyle (Enwald et al., 2017; Colombo et al., 2014); engagement in favourite and personally satisfying activities (Damodaran et al., 2014; Paimre, 2019) | Passive information behaviour (McGrath et al., 2015; Pálsdóttir, 2011; Choi, 2019; Caidi et al., 2020). Avoidance to engage in information activities: ICT tasks (Hess et al., 2013; Wu and Li, 2016; Hur, 2016; Sheng and Simpson, 2015); health decisions (Lifford et al., 2015.) |

Delegating decision-making to others (Asla and Williamson, 2015; Caidi et al., 2020; Lifford et al., 2015; Denvir et al., 2014; Burton et al., 2015; Burton et al., 2017; Goodall et al., 2014). |

| Social networks | Nurturing relationships and learning about personally significant communities (Kim and Choi, 2014, Pálsdóttir, 2011; Asla and Williamson, 2015; Du et al., 2019). Use of ICT for maintaining social relationships (Jones et al., 2015, Vroman et al., 2015, Cotten et al., 2013; Colombo et al., 2014; Damodaran et al., 2014; Bloch and Bruce, 2011). |

Social interactions with significant others as a dominant information acquisition practice (Boonchuay, 2017; Paimre, 2019; Zhao, 2019; McGrath et al., 2015; Pálsdóttir, 2011, Caidi et al., 2020; Goodall et al., 2014; Choi, 2019; Kim and Choi, 2014; Zapata et al., 2018; Du et al., 2019; Chang et al., 2014; Pang et al., 2020; Preston and Moore, 2019; Panpanit et al., 2015; Au et al., 2014; Chang et al., 2014; Medlock et al., 2015) | Caring and emotionally responsive communication with significant others as a preferred decision-making mode (Burton et al., 2015, 2017; Lifford et al., 2015, Medlock et al., 2015; Zapata et al., 2018; Paimre, 2019, Pálsdóttir, 2011; Preston and Moore, 2019). |

| Cognitive processing | Emotionally grounded motivation to use ICT (Du et al., 2019; Vroman et al., 2015) | Saving cognitive resources in search and use (Hess et al., 2013; Hur, 2016; Wu and Li, 2016). | Emotionally grounded judgment about trustworthiness and credibility of information (Caidi et al., 2020; Choi, 2019; Klein et al., 2014; McGrath et al., 2015; Nguyen et al., 2011). Using learned traditional knowledge (Chang et al., 2014; Pang et al., 2020). |

| Emotional experiences | Seeking for positive emotional experiences in general (Asla and Williamson, 2015), in use of ICT (Damodaran et al., 2014, Wu et al., 2015; Wu and Li, 2016); health-related information (Medlock et al., 2013; Harrod, 2011). Avoiding negative information (Askari et al. 2014, Nguyen et al., 2011; Pálsdóttir, 2012; Wu et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2014). |

||

Focus on emotional well-being in present

Table 3 shows that seeking well-being can stimulate information activities. Favourite and personally satisfying activities (Damodaran et al., 2014; Paimre, 2019) were highlighted by various studies (Asla and Williamson, 2015; Preston and Moore, 2019) as important motives for engagement in information activities. Asla and Williamson (2015) showed the significance of positive affective information for the elderly, Paimre (2019) reported that the elderly prioritized information activities that make them feel positive (e.g., hobbies, cooking, grandchildren) over negative (such as searching information about diseases).

The focus on sustaining well-being is visible in the information needs related to maintaining a healthy lifestyle (Enwald et al., 2017; Colombo et al., 2014). A study by Harrod (2011) reveals that understanding of health information of the seniors went beyond the disease and illness and incorporated information for maintaining independence as a sign of well-being. Surveys marginally show interest of elderly in healthy lifestyles as this specific area is hidden under general health information heading. E.g., Colombo and his colleagues have found that 53.1 % of the Italian elderly (65-74 years) were using the internet to check the updates of health-related information (Colombo et al., 2014, p. 173). Similar findings were reported in the Dutch survey where 85% of seniors were using the internet for health-related issues (Medlock et al., 2013). But Boonchuay (2017), Wu and Li (2016), and Asla and Williamson (2015) have identified a strong interest of their participants in healthy lifestyle, eating habits, and weight control, health and wellness of themselves and their families.

The level of interest (Hur, 2016) or perceived benefit of stimulating activities (Damodaran et al., 2014; Vroman et al., 2015; Sheng and Simpson, 2015) strongly motivated elderly people to perform information tasks and increased the intensity of information behaviour. Personally significant activities were related to integration of information technology into the lives of elderly (Damodaran et al., 2014; Vroman et al., 2015; Wong et al., 2014). On the contrary, as shown by studies of the internet usage, the inability to see the personal value (Vroman et al., 2015), or feeling of wasting time on the internet and in social networking sites (Bloch and Bruce, 2011), was a strong deterrent for the elderly to perform these activities.

Several studies confirmed earlier research about the delegation of information seeking and even decision making to carers, family members, health professionals, or friends (see Table 3). Elderly also preferred easy or passive information acquisition, e.g. in a beauty salon (Asla and Williamson, 2015), on television and radio (Goodall et al., 2014), or approaching people met on their way (Du et al., 2019). McGrath (2015) has found that elderly sought health information from soothing and safe public figures (clergymen, librarians, policemen), instead of health services. Asla and Williamson (2015), Choi (2019) and Pálsdóttir (2011) have noted how elderly obtain information passively and accidentally while interacting with other people. Du et al. (2018) show random and accidental discovery of information by their participants. As a result, researchers found that, e.g., elderly Chinese immigrants perceived their information as received through accidental encounters and therefore "incomplete and fragmented" (Caidi et al., 2020; Wu and Li, 2016).

Social networks

As shown in Table 3 in everyday life situations nurturing social relationships was the common motivation for the elderly to engage in information activities; it also stimulated and maintained various information needs. Information activities of the elderly were focused on learning about people and communities they cared about or belonged to (Asla and Williamson, 2015). Du et al. (2019) highlighted that Chinese immigrants used social networking application WeChat for getting information because it connected them with people of common heritage and ethnic background. Information activities were often encouraged by elderly peers and their outcomes were used to maintain and develop existing relationships by sharing relevant information (Kim and Choi, 2014; Pálsdóttir, 2011). Socializing with peers cultivated the interests of elderly people and, consequently, sustained their information needs (Asla and Williamson, 2015). ICTs were often used for maintaining existent social networks as well (see Table 3). ICTs were mostly used to communicate with family and friends, but the elderly were reluctant to expand their social networks with new contacts (Bloch and Bruce, 2011; Cotton et al., 2013).

Personal networks of trusted and familiar people were the preferred source of getting information for the elderly (Boonchuay, 2017; Choi, 2019; McGrath et al., 2015; Panpanit et al., 2015). They included family members, peer networks, and health professionals. Family members were the most important and trusted information providers (Caidi et al., 2020; Zhao, 2019; Paimre, 2019; Au et al., 2014). Children played an important role in connecting different information worlds in the study of Indonesian disasters (Pang et al., 2020), they were also the most trusted and appreciated source of information by Chinese immigrants (Du et al., 2019; Caidi et al., 2020). Elderly spouses often assumed either the role of information provider or receiver in health-information activities (Choi, 2019). The members of the same club and age group were actively used as information sources (Boonchuay, 2017; Pálsdóttir, 2011), as they have similar concerns, can learn together, share and explore how to deal with particular issues or changes (Choi, 2019; McGrath et al., 2015; Panpanit et al., 2015; Chang et al., 2014). Preston and Moore (2019) found that the telephone "befriending service" was appreciated for helping to find and pair people with similar interests and facing the same difficulties. Apart from peers, the professionals were used to obtain information. The elderly emphasized the importance of communication with significant others as a preferred mode of taking decisions and prioritized it over other ways of getting information, i.e. searching for it on the internet, reading books and leaflets, etc. (see Table 3). The veterans experiencing anxiety preferred to discuss coping strategies with health professionals and peers (Zapata et al., 2018); women with breast cancer strongly preferred communicating with doctors or nurses to make decisions about the treatment (Lifford et al., 2015; Burton et al., 2017) and associated it with the quality of care (Burton et al., 2015). Here the factor of caring and emotionally responsive communication comes into play. Preston and Moore (2019) indicated that calls from helpline services were appreciated by the elderly users for showing care about them. Lifford et al. (2015) noted that women considered conversations about breast cancer with relatives as a source of instrumental and emotional support. Additionally, Pálsdóttir (2011), Kim and Choi (2014) noticed that older adults were aware of the information needs of their peers. So, the activities of sharing and discussing with peers the information they accidentally discovered was the act of caring and served the goals of strengthening their relationships.

Cognitive processing

There is evidence that activities with personal significance and emotional well-being were related to integration of information technology into the lives of elderly and its continued use (Damodaran et al., 2014; Vroman et al., 2015; Wong et al., 2014). The ‘feel-good’ motive was found to be a powerful driver for continued use of information technology when it was associated with benefits to brain health, such as, ‘stimulating the brain’, ‘feeling part of the 21st century’, ‘maintain an active engagement in life’, or interests in hobbies like digital photography, literature or music (Damodaran, et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2015).

This observation was often coupled with the reluctance of the elderly participants to invest effort in complicated information tasks (Hess et al., 2013; Wu and Li, 2016) or acquisition of sophisticated technology skills (Hur, 2016). Hess et al. (2013) have associated this feature with higher sensitivity to the task context and need to ration cognitive resources. This may explain the findings by Wu and Li (2016) that their participants preferred to use familiar search tools, searched on the internet by clicking on links in a web page or just browsed what is on the first search results page and refused to change.

As mentioned in the theoretical part cognitive processing of elderly can serve emotional regulation goals and affect perception of trustworthiness and reliability of information sources. A number of studies have found that perceived trustworthiness of information is often associated with pleasant environment and comfort of recognizability (Damodaran et al., 2014; Zhao, 2019). The effect of the emotional value is particularly visible in the study of Chinese immigrants, who especially cherished laoxiang, people stemming from the same area in China, often speaking the same dialect. They were referred to as ‘objective’, ‘friendly’ or ‘trustworthy’. The bonds with them played an important role in well-being and sense of belonging in the new country, provided empathy and served as "accurate source of age-appropriate information" for the participants of the study (Caidi et al., 2020). The most trusted and appreciated source of information to immigrants were their children (Du et al., 2019; Caidi et al., 2020).

Comfort and trust were also increased by recognizable experience of peers. Klein and his colleagues (2014) have identified a demand for "a safe place to learn" about medicine or health, that was understood as creating peer connection between a senior learner and a senior educator. This connection was regarded as safe and reliable because both actors were perceived as equals, non-experts and sharing in discussion (Klein et al., 2014). Similar trust in peers can be seen in other studies (Boonchuay, 2017; Choi, 2019; McGrath et al., 2015; Panpanit, et al., 2015). South Korean senior citizens also confirmed that other seniors who bring enhanced interpersonal communication and self-satisfaction are their main information source (Kim and Choi, 2014). Chang et al. (2014) have noted that the criteria of trust were based less on "factuality and logic" of the presented information and more on irrational emotional base. E.g., despite being eager to learn English, elderly immigrants relied on bilingual speakers as language mediators, although it has been identified as an additional barrier to language acquisition (Goodall, et al., 2014).

Similar irrationality was identified in equal acceptance of or preference for familiar traditional medical knowledge, as noted by Chang et al. (2014) and Caidi et al. (2020). On the other hand, cultural–historical experience and indigenous knowledge enabled seniors "to make sense of information and interpret environmental signals and level of threat" during a disaster situation (Pang et al., 2020).

Emotional experience

Seeking for positive emotional experiences and avoiding the negative proved to affect different stages of information behaviour of the elderly. It also relates to the first category of focus on emotional well-being in present (Table 3). In general, it was a motivation and main goal to engage in information seeking (Asla and Williamson, 2015; Paimre, 2019). In the study of health information behaviour, Wu and Li (2016) reported positive emotional evaluation of their information seeking skills and knowledge despite insignificant improvements in task performance. Similarly, Medlock et al. (2013) reported that senior people positively evaluated their internet health information seeking experience. He noted that the elderly mostly tended to use information for changing lifestyle and habits, but not for further discussion of their health condition with the health professional (Medlock et al., 2015).

Avoidance of negative information was a strong factor preventing information seeking (Nguyen et al., 2011), in elderly people, as in the cases of information about falls (Askari et al., 2014) and negative images of the users of assistive technologies (Wu et al., 2015). The denial effect was also obvious in the studies by Liu et al. (2014), Pálsdóttir (2012) and Harrod (2011). Being aware of threats of diseases, disability and chronic conditions, the elderly adults preferred to focus on health information that would help them to keep active and maintain their independence (Harrod, 2011) and a peaceful state of mind (Liu et al., 2014). Pálsdóttir (2012) has found that elderly people were reluctant to be seen as incapable and dependent and would not seek information related to the changed conditions and circumstances.

Discussion and conclusions

Emotional regulation goals were observed throughout all stages of information behavior of the elderly. They manifested as specific types of behaviour (e.g., passive information seeking) or mechanisms that activate them (e.g., preference for positive information).

First, preference for emotional regulation caused lack of engagement in purposeful information activities. It ranged from lack of motivation to initiate the process (in some cases even avoidance of it) and allocate necessary cognitive resources to it, choosing passive information acquisition or delegation of information processing and decisions to other people. Interestingly, passiveness and non-involvement were clearly stated in previous research, but were explained by external circumstances or declining cognitive capabilities. For instance, Asla and Williamson (2015) argued that elderly adults in their fourth age increasingly relied on others in information seeking because of little availability of other information sources. Other researchers (e.g., Pálsdóttir, 2011; Nguyen et al., 2011; Hess et al., 2013) mentioned that information seeking and use behaviour was at least partly due to declining physical or cognitive abilities. SST adds a psychological dimension to these arguments by emphasizing the changing life priorities that are not focused on acquisition of new information.

Secondly, the focus on emotional and social aspects of well-being was the main motive that shaped how the elderly engaged in information activities. Studies showed that the elderly pursued information activities to experience positive emotions and strengthen social relationships. They were eager to adopt ICT tools to communicate with family and friends; became interested in information activities and ICT tools that provided emotionally meaningful positive experiences. Older adults tended to judge the credibility and trustworthiness of information resources on emotional grounds and preferred a caring and emotionally responsive interpersonal interaction for processing information and making decisions. The role of emotions in information activities is not as visible as the use of social networks in information practices. Research on the emotional parameters of information behaviour of the elderly could produce new valuable insights, as it was already successfully done by Yang (2019).

The focus on well-being and positive emotions was apparent in all stages of information behaviour. On the one hand, being a natural response to life span issues (Löckenhoff and Carstensen, 2004) such approach offers a good coping strategy with stress and challenges. The elderly focused their information activities on things that helped them feel good in terms of leisure, adaptation to their environment, healthy and active life. On the other hand, orientation to positive in line with avoiding the negative information may become destructive when it precludes receiving help from outside or inhibits use of necessary information sources. It could result in avoiding necessary health-related decisions (Liu et al., 2014), reducing the abilities of the elderly to successfully adapt to changes in their environment (e.g., Caidi et al., 2020; Du et al., 2019).

The orientation to positive experiences and pleasure could be much more exploited by the providers of health information or trainers of information and computer literacy. Often the future negative consequences of not seeking information or not gaining technology-related skills are emphasized in trying to motivate behavioural changes of seniors. The approaches emphasizing positive sides of the desired activities, such as pleasant entertainment, enjoyment, or meaningful health information leading to good health outcomes could be more empowering for the seniors and more effective in achieving the aims of these activities. The same positive strategy is crucial in promoting assistive technologies or preventive health programmes. As the analysis of literature showed, older adults cherish their independence and do not want to be treated as incapable and in need of assistance (e.g., Wu and Li, 2016; Harrod, 2011). They are flexible information-seekers who actively use their knowledge and regulate their involvement in information tasks based on its personal significance and relevance to their interests. As shown by Pang et al. (2020) reliance on traditional knowledge could be helpful in surviving during the natural disasters.

The dominant feature of the information seeking behaviour of the seniors is the reliance on communication with limited and close social environment, predominantly their family members. The seeking of new social contacts is limited and often confined to stress-related situations, such as illness, long-term move to another place, or acute danger when information is sought from unknown people perceived as authoritative or insider information sources. This limited but trusted social network is mainly formed deliberately by seeking a meaningful and deep relationship, sense of security and positive emotional experience. It is a part of an emotional regulatory mechanism that is activated by the closeness to the time horizon.

Differently from other approaches used to study the information behaviour of the older adults, SST is non-discriminative because it does not link the study of senior people with decline in specific functions of organism and does not develop age-based typologies. SST reveals universal psychological mechanisms that influence information activities and decision-making of individuals (Löckenhoff and Carstensen, 2004). Perception of available life time in future is not limited to the elderly population, but also extends to people with terminal diseases or those who experienced traumatic events (e.g., natural disasters) that could influence their understanding of time left in future.

Researchers recognised the importance of an in-depth understanding of aging for interpretation of information activities of the elderly (e.g., Harrod, 2011). Asla and Williamson (2015) applied a conception of the 'fourth age' to focus on diminishing ability rather than physical age. Colombo et al. (2014) apply the concept of 'active post-war' generation. However, a sound explanatory approach is still lacking. The findings of quantitative studies are largely descriptive and pose a lot of questions for further research: e.g., why the elderly lose interest in information about health and physical activities the older they get (Enwald et al., 2017); why some older adults do not search information about falls online and do not want to participate in online fall prevention assessment tests (Askari et al., 2014); why they use the internet more after visiting a health professional, but less preparing for the visit (Medlock et al., 2015). Mechanisms highlighted by SST, such as emotional regulation goals, rationing cognitive resources, or avoidance of negative information could provide an explanation of these activities. Application of SST would allow the researchers to carry out currently rare large-scale quantitative explanatory and predictive information behaviour studies, as these also report contradictions that cannot be explained. For instance, Burton et al. (2015) reported contradictions in findings about the amount of information desired by the elderly women for making treatment decisions; Nguyen et al. (2011) argued that "information needs are emotionally associated and sometimes contradictory". SST would be helpful to reconcile contradictory findings and fill in some missing explanations, it also can supplement existing approaches. However, it should be noted that SST focuses only on psychological mechanisms and does not include a variety of social, cultural, economical and other factors that come into play in information activities.

About the authors

Zinaida Manžuch, Associate Professor, PhD. at the Digital Media Lab, Faculty of Communication, Vilnius University, Saulėtekis Ave. 9, Vilnius, Lithuania. She received her PhD from Vilnius University and her research interests are in the areas of digital inequalities, libraries, and digital culture. She can be contacted at zinaida.manzuch@mb.vu.lt

Elena Macevičiūtė, Professor, Habil. Dr. at the Digital Media Lab, Faculty of Communication, Vilnius University, Saulėtekis ave. 9, Vilnius, Lithuania, and Swedish School of Library and Information Science, University of Borås, Allegatan 1, Borås, Sweden. She received her PhD from Moscow State Art and Culture University and her research interests are in the areas of organizational information and communication, digital publishing and reading, digital libraries’ and information management. She can be contacted at elena.maceviciute@gmail.com.

References

Note: A link from the title is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Askari, M. (2014). Improving quality of fall prevention and management in elderly patients using information technology: The impact of computerized decision support. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Amsterdam. https://dare.uva.nl/search?identifier=872ded52-66dd-4cc2-8cdf-0cfbf8b6d63d

- Asla, T. M. & Williamson, K. (2015). Unexplored territory: information behaviour in the fourth age. In Proceedings of ISIC, the Information Behaviour Conference, Leeds, 2-5 September, 2014: Part 2, (paper isic32). http://InformationR.net/ir/20-1/isic2/isic32.html (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2BgNicQ)

- Au, T. S., Wong, M. C., McMillan, A. S., Bridges, S., & McGrath, C. (2014). Treatment seeking behaviour in southern Chinese elders with chronic orofacial pain: a qualitative study. BMC Oral Health, 14(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6831-14-8

- Bloch, N., & Bruce, B. C. (2011). Older adults and the new public sphere. In Proceedings of the 2011 iConference, Seattle, Washington USA, February, 2011 (pp. 1-7). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/1940761.1940762

- Boonchuay, K. (2017). Day-to-day information needs and use of the elderly in Songkhla province, Thailand. In Chiew, K. T. et al. (Eds.). PGRES 2017, Kuala Lumpur, Eastin Hotel, July 18, 2017 (pp. 48-56). FCSIT. http://intra.fsktm.um.edu.my/~aini/sistem/pgres2017/Lampiran/DC/007_Kongkidakorn_31_7_fullPaper.pdf

- Burton, M., Collins, K. A., Lifford, K. J., Brain, K., Wyld, L., Caldon, L., ... & Reed, M. W. (2015). The information and decision support needs of older women (> 75 yrs) facing treatment choices for breast cancer: a qualitative study. Psycho‐Oncology, 24(8), 878-884. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3735

- Burton, M., Kilner, K., Wyld, L., Lifford, K. J., Gordon, F., Allison, A., ... & Collins, K. A. (2017). Information needs and decision‐making preferences of older women offered a choice between surgery and primary endocrine therapy for early breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 26(12), 2094-2100. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4429

- Caidi, N., Du, J. T., Li, L., Shen, J. M., & Sun, Q. (2020). Immigrating after 60: Information experiences of older Chinese migrants to Australia and Canada. Information Processing & Management, 57(3), 102111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2019.102111

- Carstensen, L. L., Fung, H. H., & Charles, S. T. (2003). Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motivation and Emotion, 27(2), 103-123. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024569803230

- Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54(3), 165. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.3.165

- Chang, L., Basnyat, I., & Teo, D. (2014). Seeking and processing information for health decisions among elderly Chinese Singaporean women. Journal of Women & Aging, 26(3), 257-279. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2014.888881

- Choi, W. (2019). Older adults' health information behavior in everyday life settings. Library & Information Science Research, 41(4), 100983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2019.100983

- Colombo, F., Aroldi, P. & Carlo, S. (2014). "Stay tuned": the role of ICTs in elderly life. In Riva, G., Marsan, P. A., & Grassi, C. (Eds.). Active ageing and healthy living: A human centered approach in research and innovation as source of quality of life (Vol. 203). (pp. 145-1467). IOS press. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-425-1-145

- Cotten, S. R., Anderson, W. A., & McCullough, B. M. (2013). Impact of internet use on loneliness and contact with others among older adults: cross-sectional analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(2), e39. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2306

- Damodaran, L., Olphert, C. W., & Sandhu, J. (2014). Falling off the bandwagon? Exploring the challenges to sustained digital engagement by older people. Gerontology, 60(2), 163-173. https://doi.org/10.1159/000357431

- Denvir, C., Balmer, N. J., & Pleasence, P. (2014). Portal or pot hole? Exploring how older people use the ‘information superhighway’ for advice relating to problems with a legal dimension. Ageing & Society, 34(4), 670-699. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X12001213

- Du, J. T., Tan, Y. & Xu, F. (2019). The information context of elderly Chinese immigrants in South Australia: a preliminary investigation In Proceedings of ISIC, The Information Behaviour Conference, Krakow, Poland, 9-11 October: Part 2. Information Research, 24(1), paper isic1820. http://InformationR.net/ir/24-1/isic2018/isic1820.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76lUmnoMW)

- English, T., & Carstensen, L. L. (2015). Does positivity operate when the stakes are high? Health status and decision making among older adults. Psychology & Aging, 30(2), 348-355. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039121

- Enwald, H., Kangas, M., Keränen, N., Immonen, M., Similä, H., Jämsä, T., & Korpelainen, R. (2017). Health information behaviour, attitudes towards health information and motivating factors for encouraging physical activity among older people: differences by sex and age. Information Research, 22(1), 22-1. http://www.informationr.net/ir/22-1/isic/isic1623.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6oGipnOZp)

- Goodall, K. T., Newman, L. A., & Ward, P. R. (2014). Improving access to health information for older migrants by using grounded theory and social network analysis to understand their information behaviour and digital technology use. European Journal of Cancer Care, 23(6), 728-738. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12241

- Harrod, M. (2011). "I have to keep going": why some older adults are using the Internet for health information. Ageing International, 36(2), 283-294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-010-9090-z

- Hess, T. M., Queen, T. L., & Ennis, G. E. (2013). Age and self-relevance effects on information search during decision making. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68(5), 703-711. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbs108

- Hur, M. H. (2016). Empowering the elderly population through ICT-based activities. Information Technology & People, 29(2), 318-333. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-03-2015-0052

- Jones, R. B., Ashurst, E. J., Atkey, J., & Duffy, B. (2015). Older people going online: its value and before-after evaluation of volunteer support. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(5), e122. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3943

- Kim, S. & Choi, H. (2014). Still hungry for information: Information seeking behavior of senior citizens in South Korea: Conference poster. In iConference 2014 Proceedings, Berlin, Germany (p. 889 - 894). IDEALS. https://doi.org/10.9776/14300

- Klein, L. A., Ritchie, J. E., Nathan, S. & Wutzke, S. (2014). An explanatory model of peer education within a complex medicines information exchange setting. Social Science & Medicine, 111, 101-109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.009

- Lifford, K. J., Witt, J., Burton, M., Collins, K., Caldon, L., Edwards, A., ... & Brain, K. (2015). Understanding older women’s decision making and coping in the context of breast cancer treatment. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 15(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-015-0167-1

- Lifshitz, R., Nimrod, G. & Bachner, Y. G. (2018). Internet use and well-being in later life: a functional approach. Aging & Mental Health, 22(1), 85-91. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1232370

- Liu, Z., Beaver, K. & Speed, S. (2014). Being healthy: a grounded theory study of help seeking behaviour among Chinese elders living in the UK. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 9(1), 24820. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.24820

- Löckenhoff, C.E. & Carstensen L.L. (2004). Socioemotional selectivity theory, aging, and health: the increasingly delicate balance between regulating emotions and making tough choices. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1395-1424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00301.x

- Malone, T., Jo, P., & Clifton, S. (2017). Perceived eHealth literacy and information behavior of older adults enrolled in a health information outreach program. Journal of Consumer Health on the Internet, 21(2), 137-147. https://doi.org/10.1080/15398285.2017.1300040

- McGrath, M., Clancy, K., & Kenny, A. (2015). An exploration of strategies used by older people to obtain information about health‐and social care services in the community. Health Expectations, 19(5), 1150-1159. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12408

- Medlock, S., Eslami, S., Askari, M., Arts, D. L., Sent, D., De Rooij, S. E., & Abu-Hanna, A. (2015). Health information–seeking behavior of seniors who use the internet: a survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(1), e10. https://www.jmir.org/2015/1/e10/ (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3ePckNQ)

- Medlock, S., Eslami, S., Askari, M., Sent, D., & Abu-Hanna, A. (2013). The consequences of seniors seeking health information using the internet and other sources. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 192, 457-460. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-289-9-457

- Nguyen, L., Evans, S., Wilde, W., & Shanks, G. (2011). Information needs in community aged care. In PACIS 2011: Proceedings of the 15th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems 141. Association for Information Systems. https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2011/141

- Niemelä, R., Huotari, M. L., & Kortelainen, T. (2012). Enactment and use of information and the media among older adults. Library & Information Science Research, 34(3), 212-219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2011.12.002

- OECD. (2007). Revised field of science and technology (FOS) classification in the Frascati manual. OECD/OCDE. https://www.oecd.org/science/inno/38235147.pdf (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/39mGjf5)

- Paimre, M. (2019). Do elderly people enjoy the fruits of Estonia’s e-health system? In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2019) (pp. 230-237). SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7210/fecf32caccf649beae269cfb3ec0d5f0b14c.pdf

- Pálsdóttir, Á. (2012). Elderly peoples’ information behaviour: accepting support from relatives. Libri, 62(2), 135-144. https://doi.org/10.1515/libri-2012-0010

- Pálsdóttir, Á. (2011). Opportunistic discovery of information by elderly Icelanders and their relatives. Information Research, 16(3). http://www.informationr.net/ir/16-3/paper485.html (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2WJ4hMB)

- Pang, N., Karanasios, S., & Anwar, M. (2020). Exploring the information worlds of older persons during disasters. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 71(6), 619-631. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24294

- Panpanit, L., Carolan-Olah, M., & McCann, T. V. (2015). A qualitative study of older adults seeking appropriate treatment to self-manage their chronic pain in rural North-East Thailand. BMC Geriatrics, 15(1), 166. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0164-3 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3eL9FoE)

- Preston, C., & Moore, S. (2019). Ringing the changes: the role of telephone communication in a helpline and befriending service targeting loneliness in older people. Ageing & Society, 39(7), 1528-1551. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X18000120

- Sheng, X., & Simpson, P. M. (2015). Health care information seeking and seniors: determinants of Internet use. Health Marketing Quarterly, 32(1), 96-112. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3749

- Vroman, K. G., Arthanat, S., & Lysack, C. (2015). "Who over 65 is online?" Older adults’ dispositions toward information communication technology. Computers in Human Behavior, 43, 156-166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.10.018

- Wilson, T. D. (1997). Information behaviour: an interdisciplinary perspective. Information Processing & Management, 33(4), 551-572. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(97)00028-9

- Wong, C. K., Yeung, D. Y., Ho, H. C., Tse, K. P., & Lam, C. Y. (2014). Chinese older adults’ Internet use for health information. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 33(3), 316-335. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464812463430

- Wu, Y. H., Damnée, S., Kerhervé, H., Ware, C., & Rigaud, A. S. (2015). Bridging the digital divide in older adults: a study from an initiative to inform older adults about new technologies. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 10, 193-201. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S72399

- Wu, D., & Li, Y. (2016). Online health information seeking behaviors among Chinese elderly. Library & Information Science Research, 38(3), 272-279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2016.08.011

- Yang, M. (2019). Health information literacy of the older adults and their intention to share health rumors: an analysis from the perspective of socioemotional selectivity theory. In Zhou, J. & Salvendy, G. (Eds.) Human aspects of IT for the aged population: Social media, games and assistive environments. 5th International Conference, ITAP 2019 held as part of the 21st HCI International Conference, HCII 2019 Orlando, FL, USA, July 26–31, 2019Proceedings, Part II (pp. 97-108). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22015-0_8

- Zapata, A. M. L., Beaudreau, S. A., O’Hara, R., Bereknyei Merrell, S., Bruce, J., Garrison-Diehn, C., & Gould, C. E. (2018). Information-seeking about anxiety and perceptions about technology to teach coping skills in older veterans. Clinical Gerontologist, 41(4), 346-356. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2017.1359716

- Zhao, D. (2019). Exploring older adults' health information seeking behavior: Evidence from urban China. In Blake, C. & Brown, C. (Eds.) Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, vol. 56, issue 1, (pp. 847-848). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.203

- Zou, C., & Zhou, P. (2014). Analyzing information needs of elderly people: A survey in Chinese rural community. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2(9), 109-115. DOI: 10.4236/jss.2014.29019 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3eVeADD)