Support versus restriction: parents’ influence on young children’s information behaviour in connection with mobile devices

Kirsten Schlebbe

Introduction. This paper examines how parents perceive and mediate young children's use of mobile devices and discusses how this may affect children's information behaviour.

Method. For data collection, semi-structured interviews with 22 parents from 19 families with 22 children aged one to six years who had already used mobile devices were conducted.

Analysis. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed using the software MAXQDA. A combination of inductive and deductive coding methods was used for data analysis.

Results. The analysis shows that young children engage in a great variety of information-related activities while interacting with mobile devices. The results also indicate a strong parental influence. Parents expressed positive and negative perceptions of young children's use of mobile devices and reported different enabling and restrictive mediation practices.

Conclusions. By supporting children's use of mobile devices, parents enable their children to engage in activities that help them to access new information and expand their knowledge. At the same time, parents try to protect their children from risks and negative influences through restrictions. In this way, parents act as a bottleneck for children's access to information by mobile devices.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irisic2006

Introduction

Studies indicate that children develop their first information behaviour abilities in their early years of life (Spink and Heinström, 2011). At this age, parents usually have a significant influence on their children's scope of action. Whether it is a public library that cannot be visited independently by a three-year-old child, or the ability to read and write, that is required for interaction with many information systems: although young children have their individual information needs, adults around them, especially their parents, act as a bottleneck for information. Or as Bates (1996) states: 'the younger a child is, the more the adults around that child decide what information gets to that child. It may or may not match well with what the child needs or is puzzled or scared about' (p. 8).

One important aspect to which this parental influence potentially applies is that of young children's information-related activities in connection with mobile devices. On the one hand, access to the World Wide Web and a wide range of applications offer many possibilities for interacting with information, and touch screens and voice control generally enable even very young children to interact with these devices. But on the other hand, children may experience different challenges when using the devices and may need their parents' support in some areas. For example, the handling of mobile devices requires practice, and for many use scenarios writing and reading skills are required. Additionally, children's access to the devices or specific applications could be restricted by parents.

Based on data from an earlier interview study (Schlebbe, 2020), this paper examines the following research questions:

- RQ1: How do parents perceive and mediate the use of mobile devices by their children aged one to six years?

- RQ2: How might this parental mediation affect the information behaviour of children aged one to six years in relation to mobile devices?

The paper is organised as follows. The next section introduces relevant research on young children's use of mobile devices, parental mediation strategies and their influence on children's information behaviour. Afterwards, the methods and analysis of the interview study are described. This is followed by the presentation of the results, which are then discussed and summarised.

The CSS Beautifier is a brilliant free online tool to take care of your dirty markup.

Relevant research

The following sub-sections aim to give an overview of relevant research. The first sub-section introduces studies on young children's use of mobile devices and the theory of parental mediation. The second sub-section focuses on the topic of parents' influence on young children's information behaviour, especially in connection with mobile devices.

Young children's use of mobile devices and parental mediation

In the context of this study, a mobile device was defined as, 'a portable, wireless computing device, possible to carry without additional equipment and small enough to be used while held in…hand' (Stal and Paliwoda-Pękosz, 2018, p. 197). Typical examples of mobile devices are smartphones and tablets. Studies show that in many countries, young children's use of such devices has increased during the last decade (Ofcom, 2019; Rideout, 2017).

In recent years, a growing number of projects from the field of media and communication studies investigated how parents manage their children's use of digital and mobile devices in more detail. A term frequently used in connection with these practices is that of parental mediation. In the context of children's use of television, Warren (2001) defined mediation as 'any strategy parents use to control, supervise, or interpret content' (p. 212). Three parental mediation strategies originally described in connection with children's television use are 1) active mediation: talking with children about the content, 2) restrictive mediation: setting rules and regulations, and 3) co-viewing: watching content together (Clark, 2011). During the investigation of parental mediation strategies for children's Internet use, Livingstone and Helsper (2008) noted the frequent use of technical controls as well as a blurring of co-use and active mediation in this context. Livingstone et al. (2011) further extended the approach for children's Internet use by adding the strategy of monitoring for activities whereby parents check on 'available records of the child's internet use afterwards' (p. 103). Nikken and Jansz (2014) investigated parental mediation strategies in families with children aged two to twelve years in connection with the use of digital media and included the strategy of supervision for 'parental activities whereby the child is allowed to go online alone but with the reassurance that he or she is under the direct supervision of a nearby parent' (p. 259). This study uses the categorisation of parental mediation styles described by Nikken and Schols (2015) and distinguishes the following strategies: 1) restrictive mediation, 2) active mediation, 3) co-use, 4) supervision, 5) monitoring, and 6) technical restrictions.

A significant number of studies have empirically investigated the implementation of parental mediation practices in relation to pre-school children's use of digital and mobile devices. Nikken and Schols (2015) examined the mediation practices of parents of children under eight years in the Netherlands. Their results indicate that the application of the different mediation strategies depends on parents' positive and negative attitudes towards media, as well as children's media skills, and specific media activities. An extensive qualitative study by Chaudron et al. (2015) explored children's experiences with digital technology in Belgium, the Czech Republic, Germany, Finland, Italy, the United Kingdom and Russia. Overall, seventy families with children up to eight years were asked about the children's media use and parents' mediation strategies. The results show that parents used restrictive strategies in most cases, e.g., time limits and restrictive condition of use. A secondary analysis of the data (Livingstone et al., 2015) indicates that the parents' own familiarity with digital devices influences parental mediation practices: 'parents who, because of their work or interests, have higher digital expertise and so tend to be more actively engaged in and less restrictive of children's online activities' (p. 22). Another sub-study in this project investigated the role of parents in the engagement of their six-to-seven-year-old children with digital technologies and combined the theory of parental mediation with a framework on children's rights (Dias et al., 2016). The results of forty qualitative family interviews in Belgium, Germany, Latvia, and Portugal show that parents' perceptions and attitudes play an important role in children's access to and use of digital devices. Similar to Livingstone et al. (2015), they found that parents' confidence with digital devices positively influences their perceptions and mediation strategies.

Further studies in recent years have confirmed and extended these results. Nevski and Siibak (2016) focused on the parental mediation of zero-to-three-year-old children's use of smart devices in Estonia. Using an online survey, they showed, that the most common parental mediation strategies were supervision and restrictive mediation. A survey with parents of children aged zero to seventeen years in the United Kingdom (Livingstone et al., 2018) examined how parents support their children in the digital home. The results show that 'parents engage in a range of enabling (active talking) and restrictive (setting rules, using filters) strategies' (p. 1). Comparing different age groups, they found that parents of very young children most often used time restrictions and technical control options as mediation strategies. Bergert et al. (2020) conducted an online survey to investigate parental perceptions of children's mobile technology use. They asked United States parents with children aged two to thirteen years about concerns and perceived benefits of their children's use of mobile devices as well as their parental mediation strategies. The biggest concerns of the parents regarding their children's use were related to consumed content and the time children spend with the devices. The perceived benefits for children named most often were the educational value and the development of general skills, technology literacy, and entertainment. In line with previous research, their results indicate that most of the described parental mediation strategies can be categorised as restrictive (Bergert et al., 2020).

The research described in this section helps us to understand parental perceptions and mediation of young children's use of mobile devices. Summing up, it can be assumed that parents use different strategies to mediate their children's use of mobile devices. Restrictive strategies and technical control seem to be used particularly frequently, especially with very young children. The use of specific strategies appears to be influenced by parents' own familiarity with mobile devices and their attitudes towards children's use: negative parental perceptions and insecurity in using mobile devices seem to lead to a more restrictive mediation. However, a potential influence of these parental mediation practices on children’s information behaviour has not been explored in the studies presented so far.

Parents' influence on young children's information behaviour

This study uses an open approach defining information behaviour, similar to Barriage (2015). As a consequence, the research design was guided by Bates' (2010) rather open definition covering 'all instances where people interact with their environment in any such way that leaves some impression on them – that is, adds or changes their knowledge store' (p. 2381).

Already in pre-digital times, library and information scientists stated the influence of adults, especially parents, on children's information needs and behaviour (Bates, 1996; Farrell, 1974; Walter, 1994). But for a long time, young children were generally underrepresented in information behaviour research (Given et al., 2016) and most researchers focused on school-aged children or adolescents. For example, Meyers et al. (2009) investigated the information behaviour of preteens aged nine to thirteen years. Inter alia, their results show that preteens perceived their parents as a potential source of information. But at the same time, parental power and authority acted as a barrier to information seeking and use, especially in the context of media use. Foss et al. (2012) investigated seven, nine and eleven-year-old children's online search at home. The families interviewed reported on supportive parental behaviour during online search (e.g., answering questions, showing new Websites, co-use), but also on rules and restrictions (e.g., length of use, rules about specific Websites). Since both studies only refer to school-aged children, the results cannot be directly transferred to younger children.

In recent years, there have been some important efforts to increase the visibility of younger children in information behaviour research. For example, Barriage has conducted different studies on young children's information practices, especially in relation to their hobbies and interests (Barriage, 2015; Barriage, 2018). As another example, Campana (2018) researched public library storytime events as an information environment for young children. The parental influence on young children in connection with the use of mobile devices was also addressed in some more recent information behaviour studies. Agarwal (2014) investigated children's use of touch devices between the ages of two to four years in the form of an observational single-case-study. Regarding the parental influence on the use, he found that 'the degree and type of parental awareness and support have enabled Ella to freely use the mobile devices' (p. 25). Given et al. (2016) examined the everyday life information seeking of Australian children three to five years old, using video recordings of the children's interaction with information technologies at home. Their results show, inter alia, that the children's '[p]arents and siblings were also observed aiding the young children in their play by helping them to set up and use the technology' (p. 347). However, it should be emphasised that the focus of both studies was clearly on the children's behaviour and not on the question of parental mediation.

The connection between children's information behaviour and the theory of parental mediation has hardly been explored so far. An exception is Gomez (2017), who investigated the dynamics between parental mediation and the use of information communication technologies of fourteen-to-sixteen-year-old teenagers in Puerto Rican and Dominican families living in the United States. Her results show that parents provided their children access to devices and used strategies of parental mediation, whereby their practices seemed to be strongly influenced by their personal context. However, Gomez points out that her results regarding parental mediation differ from the results of studies with younger children because of the greater independence of the adolescents studied.

Summing up, supportive but also restrictive types of parental influence on the information behaviour of children and adolescents have become evident in previous studies. But the specific nature of this influence and the role of parental mediation have hardly been addressed in information behaviour research, especially in connection with pre-school children. This study addresses this gap in research.

Method

This study is part of a larger project examining young children's information behaviour in connection with the use of mobile devices using a combination of etic and emic approaches (Shenton, 2010). The goal of the project is to examine the topic from different perspectives, including the views of young children themselves as well as the perspective of adults around them. While another study of the project will include children's perspectives, this study focuses on parents' perceptions and mediation practices.

The analysis is based on data from an interview study (Schlebbe, 2020) that investigated how children between one and six years of age use mobile devices and whether this use includes information seeking activities or other activities that can be linked to children's information behaviour. Semi-structured interviews with parents from nineteen families were conducted over nine months. For the recruitment of interview participants, a combination of convenience and snowball sampling was used. The following sampling criteria were considered:

- the interviewee is a parent of at least one child aged one to six years,

- the child has access to and has already used mobile devices, and

- the interviewee speaks German or English.

The final sample consisted of twenty-two parents from nineteen families with twenty-two children. The families lived in Germany (sixteen families), Denmark (two families) and Northern Italy (one family). Seventeen interviews were conducted in German, and two interviews were conducted in English. The quotations contained in this paper have been translated from German into English where necessary. Ten interviews were carried out by phone, six face-to-face and three by video call. Table 1 describes the sample in detail. The children were given pseudonyms for anonymisation.

| Family | Interviewee/s | Children (age in years) | Siblings (age in years) | Residence | Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Father A | Anna (5) ♀ | DK | en | |

| B | Mother B | Bo (5) ♂ | Brother (16) | DK | en |

| C | Mother C | Christian (4) ♂ | DE | de | |

| D | Father D & Mother D | Diana (5) ♀, Daniel (4) ♂ | DE | de | |

| E | Mother E | Eric (1) ♂ | DE | de | |

| F | Father F & Mother F | Finn (3) ♂ | Brother (7) | DE | de |

| G | Father G | Greta (4) ♀ | Twins (<1) | DE | de |

| H | Father H | Henry (3) ♂ | Sister (<1) | DE | de |

| I | Father I | Isabell (6) ♀ | DE | de | |

| J | Mother J | Jacob (5) ♂, Julia (3) ♀ | DE | de | |

| K | Mother K | Karla (2) ♀ | DE | de | |

| L | Mother L | Louis (2) ♂ | DE | de | |

| M | Father M | Max (3) ♂ | Brothers (<1, 11), Sister (13) | DE | de |

| N | Father N | Nina (6) ♀, Nora (4) ♀ | DE | de | |

| O | Mother O | Olivia (3) ♀ | DE | de | |

| P | Mother P | Paul (3) ♂ | Twins (<1) | DE | de |

| Q | Father Q | Quentin (3) ♂ | DE | de | |

| R | Father R & Mother R | Robert (5) ♂ | DE | de | |

| S | Mother S | Sina (4) ♀ | Brother (7) | IT | de |

The sample had a strong focus on families with children aged three to five years with seventeen children in this age range. Seven families had additional younger and/or older siblings who were not included in the study. All younger siblings were under one year old and had not yet actively used mobile devices. The older siblings were not included because the studies' focus was on the behaviour of pre-school aged children.

The length of the interviews varied between thirty and sixty minutes. Individual elements of McKenzie's (2003) model of information practices and Savolainen's (2008) model of everyday information practices that describe different information-related activities were used to develop the interview guide. The interview questions were related to mobile devices and how they were used by the children (e.g., beginning, frequency, duration, and context of use). In addition, the children's activities and their preferences regarding these activities were discussed. Another focus of the interviews was on the families' information-related activities in connection with the devices.

Analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed using the software MAXQDA. A combination of inductive and deductive coding was used, with a focus on descriptive coding. The four categories families, devices, general use and activities, were developed during the analysis described in Schlebbe (2020). During that data analysis, it became apparent, that the interviewed parents had a significant influence on their children's use of mobile devices, e.g., by limiting the frequency and duration of use as well as the access to particular content. This observation raised questions about the influence of parental mediation on children's information behaviour.

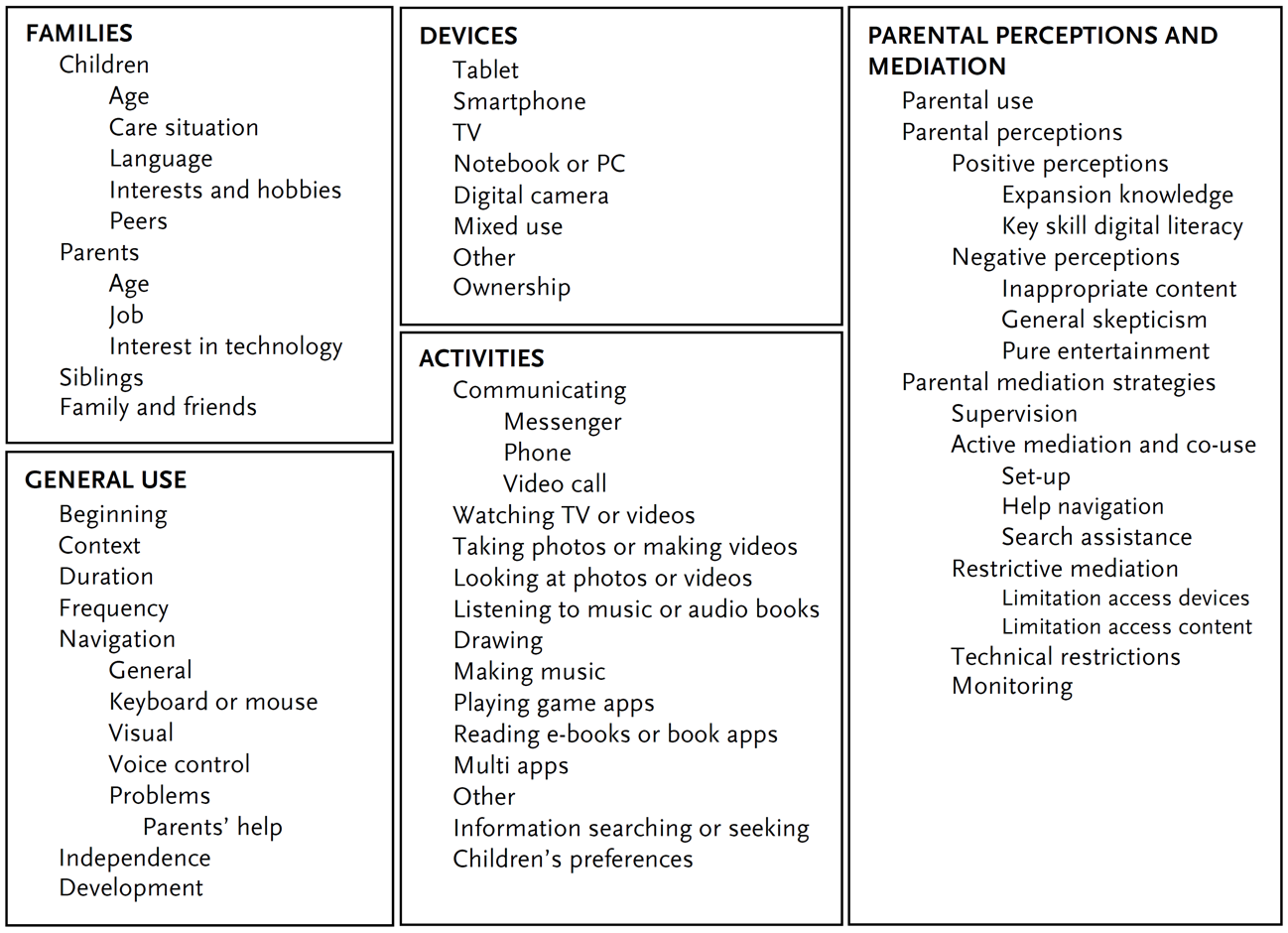

This paper examines this specific aspect, based on a secondary analysis of the interview data. The author undertook another round of coding with a particular focus on parental perceptions and mediation of their children's use of mobile devices. As a consequence, the category of parental perceptions and mediation was added for further analysis. The sub-categories regarding the parents' mediation strategies were influenced by the categorisation of Nikken and Schols (2015). Figure 1 shows the extended code system.

It must be noted that the secondary use of interview data causes some limitations since the interview questions did not focus on parental perceptions and mediation. However, the thickness of the interview data seemed to allow an exploratory analysis in this direction.

Figure 1: Extended code system

Results

In the following section, the results regarding the children's use of mobile devices are presented in a summarised form. A more detailed description can be found in Schlebbe (2020). Then the results of the analysis regarding parents' perceptions, their mediation practices, and a potential influence on the children's information behaviour are described.

Children's use of mobile devices

The vast majority of the children use the devices regularly, ranging from daily to about once a week. Only two of the families report a more limited use of the devices. In these families, the children used mobile devices very rarely and at irregular times. One of these cases was the youngest child in the sample (Eric).

While the older children in the sample were at least partly allowed to use the devices unassisted, the younger children were usually supervised by their parents. Since most children could not yet read and write, they navigated through visual features such as symbols or thumbnails. Four families reported that their children had already used voice control. In general, younger children often had to be assisted by their parents when using the devices, while the older children generally showed a higher degree of independence.

The interviews with the parents indicate that children engage in a great variety of activities related to mobile devices. The tablets and smartphones were seen as all-in-one solutions that serve simultaneously as television, computer, communication device, and camera. The children used the devices to watch online videos, play with various applications, listen to music, communicate with family and friends, view photos or videos, or take photos themselves. In Schlebbe (2020) the author discusses, why these activities that may appear as pure entertainment at first glance, can be seen as 'early steps in the 'mastery of life' that define an individual's everyday information behaviors' (Given et al., 2016, p. 346).

The use of the devices for active information searching or seeking activities, e.g., using search engines or online encyclopaedias was mentioned by half of the families interviewed. These activities took place irregularly and in situations where the children expressed a specific information need. In these situations, the parents acted as search assistants or lay information mediaries (Abrahamson and Fisher, 2007) for their children. In many cases, they used the devices to search for pictures or videos of things unknown to the child. Other examples mentioned were the use of Web mapping services to show the children the geographical location of a particular place or searching for information about events the children would like to attend. Parents who said that they did not use the devices to search for information for the children often stated that they could answer their children's questions themselves and that they did not need the devices for this purpose.

To sum up, the analysis shows that children engage in a great variety of information-related activities while using mobile devices. Therefore, it can be assumed that the use of mobile devices can be a source of information for young children.

Parental perceptions and mediation

Parents expressed positive and negative perceptions of young children's use of mobile devices and described various activities of mediation. These aspects and their potential influence on young children's digital information behaviour are examined in more detail below.

Due to the secondary use of interview data, the numbers given below must be treated with caution. It must be considered that the data might be incomplete regarding some aspects since parental perceptions and mediation practices were not explicitly asked for during the interviews.

Positive and negative perceptions

The parents expressed several perceived benefits of their children's use of mobile devices. In about half of the families (eleven of nineteen) parents expressed that they think that the children expand their general knowledge by using the devices. Parents reported, for example, that the consumed content helps the children to learn about the world around them: 'and then the content of videos she watches, that was a learning opportunity for her.' (Father G). Additionally, all parents reported that the regular use of the devices helps their children to develop and improve digital skills. Eight of the families explicitly emphasised their view of digital literacy as a critical skill in society: 'Surely you need something like that for the future, right? So, the handling of these devices' (Mother S). Another positive parental perception of the children's use of the devices is the aspect of communication. All parents interviewed support the use of the devices to enable the children to communicate with wider family and friends and see this as a valuable activity. Other rather interactive and creative activities of the children were also generally positively judged by the parents, such as listening to or making music: 'at the moment it's all about music, and we encourage him to play as much as he can' (Mother B). The parents of thirteen families also talked about benefits of children's use of the devices for themselves. In these cases, parents use the devices to keep the children occupied while they do household or work-related tasks or relax.

These positive perceptions were contrasted by several negative perceptions of young children's use of mobile devices. About half of the families interviewed (ten of nineteen) explicitly expressed that they fear their child's confrontation with inappropriate content or that they suspect that the child could be overwhelmed by the amount or complexity of content. Parents of twelve of the nineteen families expressed a critical attitude towards young children's use of digital technology in some form, even though the use of such technology was generally allowed in these families. For example, some of these parents expressed regret or doubt about the use of the devices as digital babysitters or as a reward for good behaviour. Use that was considered too long or too intense also caused a feeling of guilt in some parents. Some parents specifically emphasised that they generally prefer non-digital activities for their child: 'we find the analogue world just as good...or even better' (Father N). In addition, many parents seem to perceive the use of the devices primarily as pure entertainment or play. Five parents stated this explicitly during the interviews. Especially watching videos on the devices, which is a frequent activity in many families, or playing with game applications were considered to be of little value: 'It's just consuming, right?' (Father I).

So, on the one hand, parents expressed different perceived benefits of their children's use of mobile devices. On the other hand, they show concerns and negative feelings towards the devices. These perceptions may influence their parental mediation strategies.

Parental mediation strategies

Supervision: As mentioned above, all younger children in the sample were usually supervised by their parents while using the devices. The older children were at least partly allowed to use the devices unassisted, but only for a limited time and a specific use case.

Active mediation and co-use: Regarding enabling practices by parents, one aspect is the set-up and preparation of the devices. All parents interviewed search for suitable applications for the children, select and install them. Especially the younger children in the sample are not involved in these processes. The older children are able to suggest their wishes and interests, and the applications are searched for together and then installed by the parents.

Regarding the handling of the devices, the parents assumed that the children are able to copy and imitate much of their behaviour. Parents also take over part of the operation of the devices (e.g., opening an application or entering the camera mode), especially for the younger children in the sample. Activities that require reading or writing skills are also supported or carried out by the parents. When children encounter problems while using the devices, they usually ask their parents for help and also receive it. In these activities, as well as in the parents' search assistance activities described above, different examples of enabling parental mediation strategies can be identified. In general, it was difficult to distinguish between co-use and active mediation, partly because the line between assistance, co-use and guidance by parents was blurred, partly because the specific behaviour of the parents was not always clear in the interview data. Overall, a combination of supervision and occasional assistance seems to be more common than the strategies of active mediation or co-use.

Restrictive mediation, technical restrictions and monitoring: In all interviewed families, parents restrict children's access to the devices in some form. For example, the devices can only be used by the children at certain times and for a certain period. In all families, children have to ask their parents for permission before using the devices, and all parents use the security settings to control the children's access to the devices. To restrict the frequency and duration of use, all parents interviewed use verbal agreements and general rules with their children. Access to applications, functions, and specific content is also restricted, depending on parents' rules. As a result, children are usually allowed to navigate within particular applications and features of the devices, but not in more open online contexts, e.g., using a Web browser. Five parents explicitly reported using technical device settings, for example, safety settings or specific profiles, to restrict the children's use in some form. Only in one case (Family G), an external mobile application is used to monitor the child's use. In the other families, the children's use is usually controlled by parental supervision.

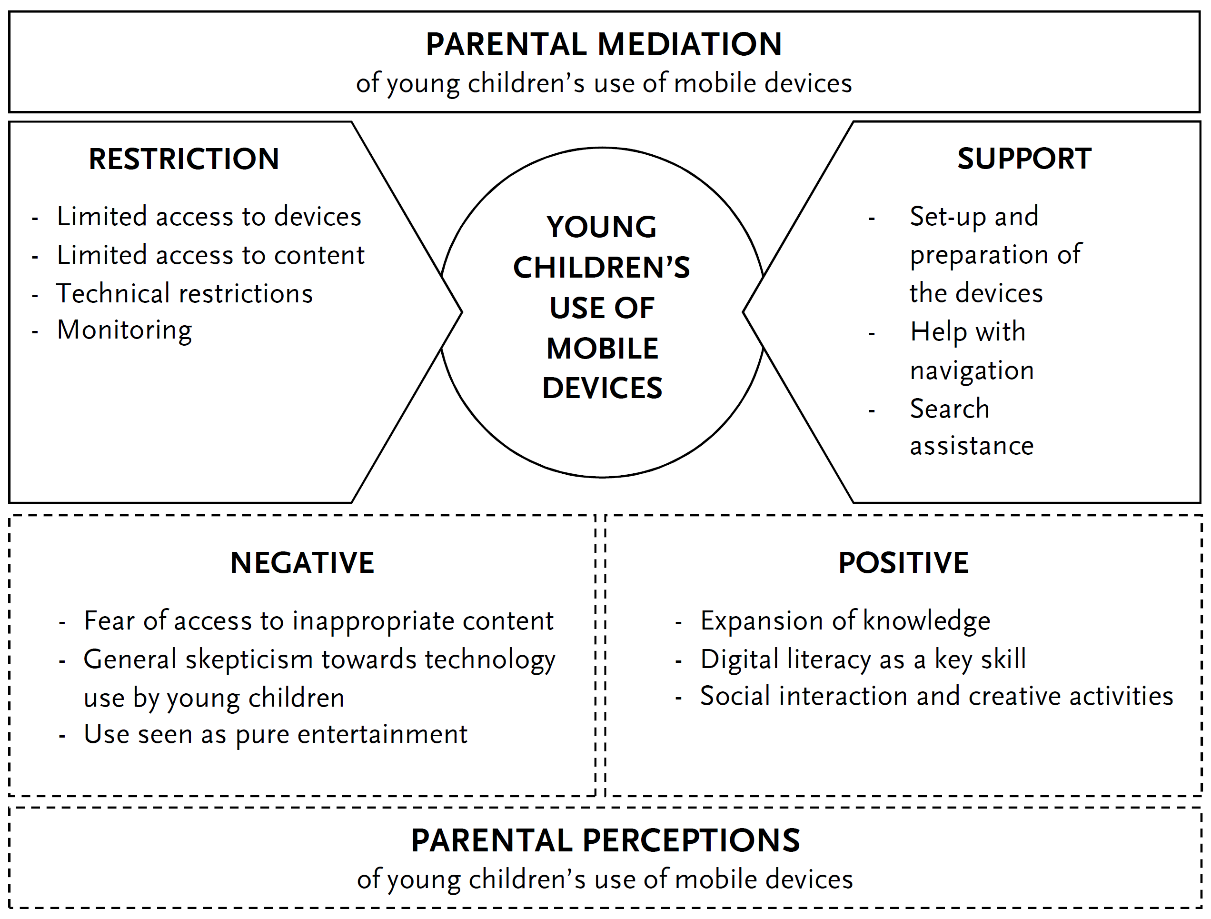

Figure 2 illustrates the potential parent-related factors influencing young children's use of mobile devices that were mentioned during the interviews in a summarised form.

Figure 2: Potential parent-related factors influencing young children's use of mobile devices

It is important to emphasise that in the families examined, the negative and positive parental perceptions were expressed to varying degrees, and different combinations of parental mediation strategies were reported. These differences seem to be related to diverse family contexts and individual parent- and child-related factors. However, a deeper analysis of these aspects is beyond the scope of this paper.

Parental influence on children’s digital information behaviour

The question arises how negative and positive parental perceptions, as well as supportive and restrictive mediation practices, influence young children's information behaviour in connection with mobile devices.

By giving their general permission and supporting their children's use of mobile devices, parents enable their children to engage in various activities that can help them to access new information and expand their knowledge. In cases of active information searching or seeking, parents sometimes even act as search assistants and use the devices to satisfy their children's information needs. At the same time, parents try to protect their children from risks and negative influences, which certainly exist for children in the digital environment, through restrictions and limitations. However, these restrictions may also keep the children away from information, and in this way, parents act as a bottleneck for children's access to information.

Thus, the strong parental influence on children's access to information, that Bates (1996) has stated, also seems to be relevant in the digital context. The parental influence may even be stronger than in other contexts, since young children's use of mobile devices seems to be associated with particularly negative perceptions, at least for some parents.

Discussion and Conclusions

This paper examined parental perceptions of and mediation practices in connection with their children's use of mobile devices and discussed how this might affect children's information behaviour.

The results indicate that parents have positive and negative perceptions of the use of mobile devices by their children aged one to six years. Perceived benefits named by parents are, e.g., the expansion of children's general knowledge or the improvement of digital skills. Concerns or negative perceptions regarding young children's use of mobile devices named by parents are, e.g., the confrontation with inappropriate content or an understanding of the use as pure entertainment. These results are in line with previous research (Bergert et al., 2020; Chaudron et al., 2015).

Regarding parental mediation, the parents interviewed reported the use of different mediation strategies. In all families interviewed, a combination of enabling and restrictive strategies was identified. A quantitative comparison between the use of different approaches is difficult due to the qualitative data basis. However, restrictive strategies were generally mentioned more often by parents during the interviews than supportive strategies. This impression is also reflected by the number of coded text segments, with more than twice as many codings in the restrictive categories compared to the enabling categories. The prevalence of restrictive mediation and supervision seems to confirm the results of previous studies (Livingstone et al., 2015; Livingstone et al., 2018; Nevski and Siibak, 2016).

The second research question explored the potential influence of parental mediation practices on children's information behaviour. The analysis of the interviews showed that children are generally able to engage in a great variety of information-related activities while using mobile devices. By supporting the children's use, parents enable their children to engage in various activities that help them to access new information and expand their knowledge. These results are similar to those described by Agarwal (2014) and Given et al. (2016). In cases of active information searching or seeking, parents sometimes even act as search assistants and use the devices to provide their children with information. In these cases, parents enable and support the satisfaction of their children's information needs. At the same time, parents try to protect their children from risks and negative influences through restrictions and limitations. These restrictions may also keep the children away from further information, and in this way, parents act as a bottleneck for children's access to information by mobile devices.

When interpreting the results, the limitations of the study should be considered. As mentioned before, the secondary analysis of interview data causes some limitations since the interview questions did not focus specifically on the parents' perceptions and mediation practices. Additional information on the parents interviewed (e.g., education, income) could not be used for the analysis because this data was not collected for the original study (Schlebbe, 2020). A single researcher performed the coding, so the coding process was not validated by intercoder reliability. Due to the exploratory nature of the study and the rather small number of families interviewed (N = 19), the results cannot be generalised.

Nevertheless, the present study provides valuable insights into parents' influence on their children's use of mobile devices and the potential impact on their information behaviour. Hopefully, it will contribute to a greater awareness of the theory of parental mediation in the research on children's information behaviour.

Further research should investigate the influence of parental mediation on young children's information behaviour in relation to mobile devices in a more structured and quantifiable way. Moreover, it should provide guidance how parents can be assisted in developing a successful balance between supportive and protective practices to optimally enhance young children's information behaviour in connection with mobile devices.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all the participants who volunteered for this study. The author is also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

About the author

Kirsten Schlebbe is a lecturer and doctoral student at the Berlin School of Library and Information Science at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. She can be contacted at: schlebbe@ibi.hu-berlin.de.

References

- Abrahamson, J.A. & Fisher, K.E. (2007). 'What's past is prologue': towards a general model of lay information mediary behaviour. Information Research, 12(4), paper colis15. http://informationr.net/ir/12-4/colis/colis15.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200802232737/http://informationr.net/ir///12-4/colis/colis15.html)

- Agarwal, N.K. (2014). Use of touch devices by toddlers or preschoolers: observations and findings from a single-case study. In D. Bilal & J. Beheshti (Eds.), New directions in children’s and adolescents’ information behavior research (pp. 3-37). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/S1876-056220140000010045

- Barriage, S. (2015). ‘Talk, talk and more talk': parental perceptions of young children's information practices related to their hobbies and interests. Information Research, 21(3), paper 721. http://InformationR.net/ir/21-3/paper721.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200727081112/http://informationr.net/ir//21-3/paper721.html)

- Barriage, S.C. (2018).Examining the red thread of information in young children’s interests: a child-centered approach to understanding information practices. (Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation). Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ.

- Bates, M.J. (1996). Learning about your users' information needs: a key to effective service. In A. Cohen (Ed.), Proceedings of the fifth Pacific Islands Association of Libraries and Archives Conference (pp. 5-12). Pacific Islands Association of Libraries and Archives.

- Bates, M.J. (2010). Information behavior. In M.J. Bates & M.N. Maack (Eds.), Encyclopedia of library and information science (pp. 2381-2391). Taylor & Francis.

- Bergert, C., Köster, A., Krasnova, H. & Turel, O. (2020). Missing out on life: parental perceptions of children’s mobile technology use. In N. Gronau, M. Heine, Krasnova & K. Pousttchi (Eds.), Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Wirtschaftsinformatik (pp. 568-583). ERP. http://dx.doi.org/10.30844/wi_2020_f1-bergert

- Campana, K. (2018).The multimodal power of storytime: exploring an information environment for young children. (University of Washington doctoral dissertation). http://hdl.handle.net/1773/42420 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200607144434/https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/handle/1773/42420)

- Chaudron, S., Beutel, M.E., Černikova, M., Donoso Navarette, V., Dreier, M., Fletcher-Watson, B., Heikkilä, A-S., Kontríková, V., Korkeamäki, R-L., Livingstone, S., Marsh, J., Mascheroni, G., Micheli, M., Milesi, D., Müller, K.W., Myllylä-Nygård, T., Niska, M., Olkina, O., Ottovordemgentschenfelde, S., … Wölfling, K. (2015). Young children (0–8) and digital technology: a qualitative exploratory study across seven countries. EU Publications. http://dx.doi.org/10.2788/00749

- Clark, L.S. (2011). Parental mediation theory for the digital age.Communication Theory, 21(4), 323-343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2011.01391.x.

- Dias, P., Brito, R., Ribbens, W., Daniela, L., Rubene, Z., Dreier, M., Gemo, M., Di Gioia, R. & Chaudron, S. (2016). The role of parents in the engagement of young children with digital technologies: exploring tensions between rights of access and protection, from ‘Gatekeepers’ to ‘Scaffolders’.Global Studies of Childhood, 6(4), 414-427. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043610616676024

- Farrell, D.G. (1974). Library and information needs of young children. In C.A. Cuadra & M.J. Bates (Eds.), Library and Information Service Needs of the Nation: Proceedings of a Conference on the Needs of Occupational, Ethnic, and Other Groups in the United States (pp. 1421-1454). US Government Printing Office.

- Foss, E., Druin, A., Brewer, R., Lo, P., Sanchez, L., Golub, E. & Hutchinson, H. (2012). Children's search roles at home: implications for designers, researchers, educators, and parents. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63, 558-573. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21700

- Given, L., Winkler, D.C., Willson, R., Davidson, C., Danby, S. & Thorpe, K. (2016). Watching young children “play” with information technology: everyday life information seeking in the home. Library & Information Science Research, 38, 344-352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2016.11.007

- Gomez, S.E. (2017). Information practices relative to parental mediation and the family context among puerto rican and dominican teens. (Rutgers University Ph.D. dissertation). https://doi.org/doi:10.7282/T3F76GPK

- Livingstone, S., Blum-Ross, A., Pavlick, J. & Ólafsson, K. (2018). In the digital home, how do parents support their children and who supports them? Parenting for a digital future: survey report 1. EU Kids Online.

- Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A. & Ólafsson, K. (2011). Risks and safety on the internet: the perspective of European children: full findings and policy implications from the EU kids online survey of 9-16-year olds and their parents in 25 countries. EU Kids Online.

- Livingstone, S. & Helsper, E.J. (2008). Parental mediation of children's internet use.Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 52(4), 581-599. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838150802437396

- Livingstone, S., Mascheroni, G., Dreier, M., Chaudron, S. & Lagae, K. (2015). How parents of young children manage digital devices at home: the role of income, education and parental style. EU Kids Online.

- McKenzie, P.J. (2003). A model of information practices in accounts of everyday‐life information seeking. Journal of Documentation, 59(1), 19-40. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410310457993

- Meyers, E.M., Fisher, K.E. & Marcoux, E. (2009). Making sense of an information world: the everyday-life information behavior of preteens. Library Quarterly, 79(3), 301-341. https://doi.org/10.1086/599125

- Nevski, E. & Siibak, A. (2016). The role of parents and parental mediation on 0-3-year olds’ digital play with smart devices: Estonian parents’ attitudes and practices. Early Years, 36(3), 227-241. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2016.1161601

- Nikken, P. & Jansz, J. (2014). Developing scales to measure parental mediation of young children's internet use. Learning, Media and Technology, 39(2), 250-266. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2013.782038

- Nikken, P. & Schols, M. (2015). How and why parents guide the media use of young children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(11), 3423-3435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0144-4

- Ofcom. (2019). Children and parents: media use and attitudes report 2018. Ofcom. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/134907/children-and-parents-media-use-and-attitudes-2018.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200723022130/https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/134907/children-and-parents-media-use-and-attitudes-2018.pdf)

- Rideout, V. (2017). The common sense census: media use by kids age zero to eight. Common Sense Media. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/research/csm_zerotoeight_fullreport_release_2.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200803071819/https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/research/csm_zerotoeight_fullreport_release_2.pdf)

- Savolainen, R. (2008). Everyday information practices: a social phenomenological perspective. Scarecrow.

- Schlebbe, K. (2020). Watching, playing, making, learning: young children’s use of mobile devices. In A. Sundqvist, Berget, J. Nolin & K.I. Skjerdingstad (Eds.), Sustainable Digital Communities: iConference 2020 (pp. 288-296). Springer Nature. (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 12051). http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43687-2_23

- Shenton, A.K. (2010). Etic, emic, or both? A fundamental decision for researchers of young people's information needs. New Review of Children's Literature & Librarianship, 16, 54-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614541.2010.503747

- Spink, A. & Heinström, J. (2011). Information behaviour development in early childhood. In A. Spink & J. Heinström (Eds.), New directions in information behaviour (pp. 245-256). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Stal, J. & Paliwoda-Pękosz, G. (2018). A SWOT analysis of using mobile technology in knowledge providing in organisations. In J. Kowal, A. Kuzio, J. Mäkiö, G. Paliwoda-Pękosz, P. Soja & R. Sonntag (Eds.), Proceedings of theInternational Conference on ICT Management for Global Competitiveness and Economic Growth in Emerging Economies, ICTM 2018 (pp. 228-242). The College of Management "Edukacja".

- Walter, V.A. (1994). The information needs of children. Advances in Librarianship, 18, 111-129. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/S0065-2830(1994)0000018006

- Warren, R. (2001). In words and deeds: parental involvement and mediation of children's television viewing. The Journal of Family Communication, 1(4), 211-231. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327698JFC0104_01