Short paper

Information literacy as a joint competence shaped by everyday life and workplace roles amongst Scottish community councillors

Peter Cruickshank, Hazel Hall, and Bruce Ryan

Introduction. This paper addresses the information practices of hyperlocal democratic representatives, and their acquisition and application of information literacy skills.

Method. One thousand and thirty-four Scottish community councillors completed an online questionnaire on the information-related activities they undertake as part of their voluntary roles, and the development of supporting competencies. The questions related to: information needs for community council work; preparation and onward dissemination of information gathered; factors that influence community councillors’ abilities to conduct their information-related duties.

Analysis. Data were summarised for quantitative analysis using Microsoft Excel. Free text responses were analysed in respect of the themes from the quantitative analysis and literature.

Results. Everyday life and workplace roles are perceived as the primary shapers of information literacy as a predominantly joint competence.

Conclusion. The focus of information literacy development has traditionally been the contribution of formal education, yet this study reveals that prior employment, community and family roles are perceived as more important to the acquisition of relevant skills amongst this group. This widens the debate as to the extent to which information literacy is specific to particular contexts. This adds to arguments that information literacy may be viewed as a collective accomplishment dependant on a socially constructed set of practices.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irisic2008

Introduction

Presented in this paper is a study of the information behaviour and practices of a group of hyperlocal democratic representatives, and their acquisition of the information literacy skills that underpin their work. The influence of various roles in the development of information literacy, and the collaborative characteristics of information activities on which this depends, are examined.

The analysis presented extends prior research on the information practices of unpaid Scottish community councillors, and on the perceptions of members of this community in respect of the value of information skills, needs for information literacy training and the role of the public library in supporting community council work (Hall, et al., 2018, 2019; Cruickshank and Hall, 2020). This new work responds to calls for greater attention to be paid to information literacy research in settings other than educational institutions and libraries (e.g., Martzoukou and Sayyad Abdi, 2017). Hence, in this paper information literacy is conceptualised as a suite of competencies ‘connected to searching for, critically evaluating and using information effectively to solve everyday problems’ (Martzoukou and Sayyid Abdi, 2017, p. 634).

The report of the empirical study is framed by a literature review that summarises relevant prior work on: information literacy in civic/political contexts; workplace information literacy (in acknowledgement of the quasi-work environment in which volunteer community councillors operate); contextual factors and life roles deemed important to the acquisition of information literacy; and information literacy as an individual or joint competence. Then follows an account of research design and implementation. The research findings derive from the analysis of survey data collected from 1034 Scottish community councillors. Everyday life and workplace roles (rather than formal education) are revealed as the primary shapers of information literacy as a joint competence amongst Scottish community councillors. The detail presented is significant for an understanding of the development of information literacy within quasi-work communities, and its enactment as collaborative practice. This work adds to a neglected area of research in the area, i.e. information literacy amongst unpaid democratic representatives.

Literature review

The findings from the research discussed in this paper contributes to extant knowledge on information literacy in civic and political contexts. It draws on the analysis of data collected from Scottish community councillors who work, albeit on a voluntary basis, at the lowest hyperlocal tier of democracy in Scotland. To date, investigations of this nature have been rare amongst a plethora of research outputs predominantly concerned educational environments, as has been noted by many researchers in the field (for example, Hollis, 2018, p. 79; Martzoukou and Sayyad Abdi, 2017, p. 635).

Prior studies of broad thematic relevance to the work reported here have considered the collaborative nature of information literacy in government (Kauhanen-Simanainen, 2005, 2007); the participation (or not) of citizens in political processes (for example, Smith, 2016); the use of Facebook by election candidates (Bronstein, et al., 2018); digital media deployment of European Union parliamentarians (Theiner, et al., 2018). Other studies, while not focused on information literacy per se, have drawn attention to such skills in broader investigations of information behaviour and use in civic and political contexts (for example, Killick, et al., 2016, p. 393). There is, however, an apparent dearth of studies on themes of specific relevance to the themes of this paper (Hall et al., 2018, 2019).

While it should be acknowledged that Scottish community councillors are unpaid democratic representatives, the activities that they perform may be considered a form of voluntary work. As such, the literature on workplace information literacy provides a preface for the empirical study discussed below. As is the case of studies of information literacy in civic and political contexts, the body of research on workplace information literacy is also small and under-researched (Lockerbie and Williams, 2019). In 2014, for example, Williams, et al. identified only 41 papers on this theme. However, it is growing (Forster, 2019, p. 349), and there are further calls for its expansion (Ahmad and Widén, 2018, p. 2). In a recent literature review, the types of professional groups investigated in studies of workplace information literacy have been identified to include a range of employees such as scientists, engineers and health professionals (Martzoukou and Sayyad Abdi, 2017, p. 638). A strong message from this body of work is that information literacy is contextual, and that workplace information literacy is therefore situated and enacted in practice (Forster, 2017; Goldstein and Whitworth, 2017; Lloyd, 2013, p. 223; Lloyd, 2017, p. 101). Information literacy practice is thus social, embodied and temporally and geographically related (Lloyd, 2017, p. 101; Olsson, 2014, p. 84; Webber and Johnston, 2017, p. 158). This implies a shift in focus from the individual to the social (workplace) context, with an emphasis on situated, rather than generic, skills.

Within this extant body of literature on workplace information literacy, it has been established that contextual factors contribute to its acquisition. These factors include prior education, self-efficacy, previously acquired knowledge and experience, and other social factors. In their literature review, Martzoukou and Sayyad Abdi (2017) emphasise in particular the importance of different roles in underpinning information literacy development (Table II, p. 655). These roles may be professional (p. 638), in healthcare (p. 649) and in informal care (p 651), and social such as citizenship (p. 643), and motherhood (p. 651). The term life roles is used to refer to these roles collectively. Of direct relevance to the empirical work reported here, are suggestions in prior work that the information literacy skills needed for community engagement may be shaped by family roles and relationships, location (rural or urban), and factors associated with the digital divide. It is thus implied that opportunities for citizens to develop their information literacy are not equal (p. 644).

Regardless of their levels and means of their acquisition, however, there is mixed evidence on the extent to which information literacy skills gained in one work environment are transferable to another. In some cases, it is argued that the situated nature of information literacy means that many workers are not able to apply elsewhere information literacy skills developed in one specific context. In contrast, there are documented cases where the social context provides skills and support for applying knowledge and skills across boundaries (Forster, 2015, p. 63, citing Bruce and Hughes, 2010). In particular, in the small body of published research that concerns everyday life information literacy and ordinary people, attention is drawn to the importance of applying information literacy skills from one life context to another. For example, it has been argued that skills acquired in the workplace might be transferable to a hobby, citizenship or community activity, and to other social roles in informal social settings where the evaluation and methodological use of information sources is required (Martzoukou and Sayyad Abdi, 2017).

Having considered prior work on information literacy of relevance to the specific context of the study reported in this paper (i.e., on civic and community quasi-workplaces, and the transferability of relevant skills from one context to others), it is worth highlighting the distinction between the treatment of information literacy as a competence of the individual, and of the group.

Since information literacy research has its origins in education and librarianship (as noted, for example, by Crawford and Irving, 2009, p. 30; Forster, 2017; Lloyd, 2017, p. 92; Martzoukou and Sayyad Abdi, 2017, p. 635), it has traditionally been conceptualised as a component of the learning process (Behrens, 1994, p. 317; Ferguson, 2012, p. 26; Hollis, 2018, p. 84). This is often with reference to a defined target, such as the submission of a paper, piece of coursework, or project report. The implication here is that information literacy is a personal attribute, developed in individuals who work independently (Forster, 2015, p. 63). This is reflected in the representation of competencies in educational models of information literacy (such as SCONUL, 2011), and narratives around the term (see, for example, CILIP, 2018).

To a lesser degree, information literacy has also been considered as an attribute of the workplace in that is owned collectively, and applied jointly (Lloyd, 2013). Here information literacy is viewed as socially constructed and situated within collective and/or collaborative dimensions (for example, Collard, et al., 2016, p. 82; Crawford and Irving, 2009, p. 30; Felstead and Unwin, 2016, p. 20; Hall et al., 2018; Lloyd, 2004, p. 218; 2017 p. 92). As Collard et al. (2016, p. 82) explain:

We consider information literacy to be social in at least three ways: (1) it relies on social relationships and organization as resources for its expression and development, (2) it shapes social relationships and social organization, and (3) it is (at least in part) a collective accomplishment.

That everyday information literacy is also seen as an inherently collaborative cross-group construct, where skills are acquired and applied from multiple sources (Martzoukou and Sayyad Abdi, 2017, p. 642), strengthens the argument for considering information literacy more readily as an attribute of the group (albeit acknowledging that group information literacy depends on that of individuals). The way in which this joint activity is structured, however, remains under-researched, albeit that Hall et al. (2018) have shown that activity theory can usefully be applied to unpick this phenomenon.

The analysis of prior research on information literacy conducted for the study as summarised here surfaced a number of opportunities to contribute to the domain in an investigation into the information practices of Scottish community councillors. This contribution comprises two main strands on: (1) the development of information literacy skills based on experience of life roles (as defined above); and (2) the levels at which information literacy is operationalised.

Methods

Two main research questions are addressed in this paper:

- What is the relative importance of life roles that shape the information literacy of Scottish community councillors?

- To what extent is information literacy operationalised as an individual/joint competence in the quasi-work environment of a community council?

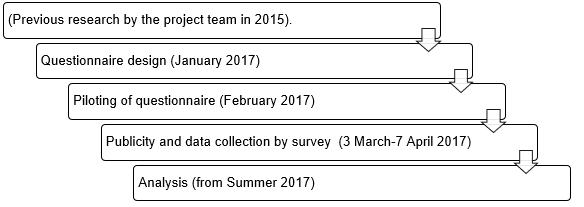

The empirical work was conducted using the survey method. Following ethical approval and piloting, an online questionnaire comprised 26 questions was advertised through channels used by the Scottish community councillor population. It was made available to this community (only) for completion over a period of four weeks in March/April 2017.

Four questions in the questionnaire were analysed to address the two research questions noted above:

- In your community council, who decides the aims and methods for gathering information about local issues? In your community council, who finds, edits and presents information about local issues? (Question 3)

- In your community council, who decides that the community council has found enough information about local issues? (Question 4)

- How much have any of these (present or past) roles helped you learn how to process information relevant to your community council work? (Question 5)

- If any other life-roles or factors helped you learn how to find, process/edit and share information relevant to your community council work, please tell us what they are and how helpful they have been. (Question 17)

Each question was framed around (a) the information-related roles of community council members (i.e. assigned responsibilities for identifying information needs, determining the means of meeting these information needs, accessing the information sought, and its dissemination) and (b) life roles (as defined above) that prepare community councillors for information work in hyperlocal democracy.

The groupings of life role presented to the respondents in the questionnaire were derived from the findings of another project to which Scottish community councillors had previously contributed (Hall et al., 2018). Equally, close reference to competencies as articulated in information literacy models available at the time (e.g. SCONUL, 2011) helped to guide the design of questions related to skills, and to organise data for analysis.

The response format for each of the questions allowed for the submission of both (scalar) quantitative and (free text) qualitative data. In addition, data on respondent demographics were collected in order to gain an understanding of the general profile of respondents, for example in terms of age, sex, highest level of education, ethnicity and employment status.

Particular care was taken over wording of actual questions to avoid the use of technical terms that may be meaningful in academia, but not elsewhere. For example, it was anticipated that community councillors would not be conversant with the broad term information literacy, nor familiar with the terminology of established information literacy models, such as the pillars of the SCONUL model (2011): identify, scope, plan, gather, manage, present and evaluate. Therefore, during the piloting of the questionnaire respondent understanding of proposed wording for individual questions was checked. For example, it was found that the phrase ‘learn how to process information’ elicited reflections from participants on information literacy skills development (in line with the working definition of information literacy presented above) so this wording was adopted in the final version of the questionnaire as a proxy for ‘develop information literacy skills’. It is acknowledged that simplifying the vocabulary of the questionnaire in this way for a lay audience reduced its level of sophistication, and leaves it open to criticism. Similarly, caution is required when drawing conclusions from self-reported scalar responses to questions of opinion. This is because it is impossible in this case to be certain that all study respondents understood the scales in the same way, and there was no opportunity to provide for them to provide nuanced responses to the questions posed. The option of supplying additional free text comments was offered as a means of reducing these limitations.

Figure 1 below gives an overview of the stages in research design and data collection, including a pilot phase during which the questionnaire was developed and tested.

Figure 1: Overview of the data collection process

In total, 1034 community councillors responded to the call to complete the questionnaire. Given the estimate of 12,000 community councillors in Scotland (Hall et al., 2019), this represents around 8% of the total population. Some respondents abandoned the questionnaire part-way through completion, or did not answer all the questions. Whether or not this was due to its length is uncertain. Whatever the reason, the number of usable responses for data analysis is lower than 1034. The details of the questionnaire themes, data sought and levels of response are summarised in Table 1.

| Theme | Specific data sought on: | Free text responses | Scalar responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information needs analysis, and strategy for meeting information needs (Q3) |

Who within the community council:

|

223 | 963 |

| Information seeking, reformatting, and dissemination (Q4) |

Who within the community council:

|

||

| Information saturation (Q5) |

Who within the community council:

|

712 | |

| Factors that have an impact on the ability of individuals to conduct community council information work (Q17) |

|

144 | 876 |

In addition to the responses summarised in the table above, 866 participants provided demographic data.

The quantitative data were summarised for analysis using Microsoft Excel. Following this, the free text responses, which were brought together in a single file according to question, were reviewed manually. This exercise took into account themes from the literature review, and provided further insight to the quantitative analysis for the account of the findings that follows below.

Findings and discussion

Demographics of respondents

The demographic data were first evaluated to establish the representativeness of the responses. This analysis, summarised in Table 2 below, revealed the questionnaire respondents as predominantly white, well-educated, male and over-55 years of age. The largest employment group was retired. These findings were not entirely unexpected: they fit with both observed compositions of community council membership and findings of prior research in the domain (Hall et al., 2018).

| Sex | 57% male, 43% female |

| Age | 69% over 55, 27% aged 36-55, 4% under 35 |

| Employment | 48% retired, 38% employed, 14% other |

| Education | 56% university/professional |

| Ethnicity | 95% white |

| Origin | 76% Scotland, 18% England, 6% other |

However, it should be noted that those who completed the questionnaire were motivated to do so because they had an interest in the study and the time to participate in it. Thus, the findings reported below are likely to be more representative of the opinion of engaged community councillors with time to participate in the study, rather than of members of the community councillor population in general.

Life roles that shape the information literacy of Scottish community councillors

876 respondents answered the question on the value of different life roles (as conceived above) that shape the development of information literacy. For ease of questionnaire completion, a six-point Likert scale (0-5) was offered so that the respondents could give a rating for the seven life roles listed in Table 3 in response to Question 5. The table summarises the data in ranked order, with the majority responses highlighted.

|

Source: Q17 n=876 |

very helpful or helpful (5,4) |

not helpful at all or not relevant (0,1) |

Neutral responses (2,3) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| workplace roles* | 71% | 16% | 23% | 100% |

| being a friend or neighbour | 52% | 18% | 30% | 100% |

| family roles** | 42% | 32% | 26% | 100% |

| social clubs† | 32% | 47% | 31% | 100% |

| work context†† | 29% | 54% | 27% | 100% |

| being a student | 23% | 58% | 19% | 100% |

| being a child/ at school | 13% | 69% | 28% | 100% |

| * being an employee, manager; **being a parent, grandparent; † being a member of a sports or social/recreational organisation; ††being in a trade union or professional body | ||||

The figures in the table show a distinction between the extent to which different life roles are perceived by community councillors to have contributed to the development of their information literacy skills. The indication here is that they believe that paid employment is perceived to offer most value, and formal education the least.

In their textual responses, 52 out of 876 respondents were specific about the nature of paid employment that had supported their acquisition of information literacy skills. For example, almost half (20) mentioned work roles in academia, education and/or training. Experience at director or managerial level was also cited often (15 respondents), as was work with, or for, religious bodies (9 respondents).

As well as formal work roles, the analysis of textual responses revealed that unpaid voluntary work is deemed important. This includes, for example, service for the Scout and Guide movements, and a range of other unpaid work activities such as citizens’ advice, church, and emergency response roles.

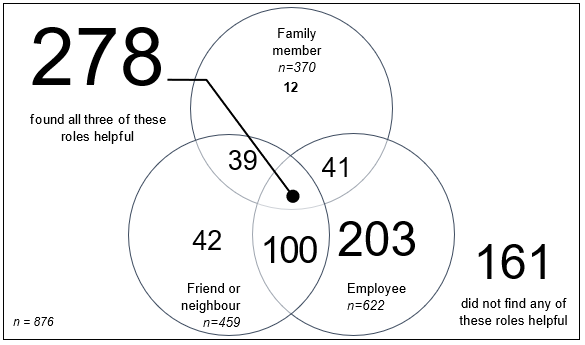

Figure 2 shows that in respect of the three top roles identified in Table 3, almost one third of respondents (278 out of 876, 32%) rated all three highly. In total 715 (82%) identified one or other of these roles to be helpful.

Figure 2: Value of the top three life roles to the development of information literacy

Social context is, of course, an important factor in the development of information literacy skills. However, it is clear that some social contexts are perceived by these study participants as more important than others. For example, such as social clubs, or professional or trade union involvement do not feature in Figure 2.

From these findings it can be seen that it is a combination of experiences from across life (some of which are more important than others) that underpins the development of information literacy amongst this cohort of volunteer community representatives. A comment from respondent 590 serves as illustration of the wide variety of experiences that could contribute to the development of competences in information literacy:

All [the roles listed] have played a part in my life, and made me who I am - I do not subdivide experience like this. Having said that I was a teacher for 37 years … I am also heavily involved in church ... I am a trustee of five different charities, music (3 choirs, in one of which I have held office), philately (4 different societies) … and in my time written countless minutes as well as still looking after 9 non-personal Bank accounts! I have gained experience from all of these and on top of that I did my teacher training [abroad] and taught there, living there for over three years. I have been married for over 40 years, have a daughter and a grand-daughter, so these all contribute!

Informal, everyday and lifelong activities in combination are important to information literacy development in the older population represented in this study. Even the well-educated individuals surveyed emphasised contexts that are more immediate over their past education as the main source of the skills required to carry out their information-related community councillor roles. These findings lend support to the view that workers (in this case older adults contributing in a voluntary capacity) are able to apply information literacy developed in one specific context to another, as proposed in a number of the studies identified by Martzoukou and Sayyad Abdi (2017) in their literature review cited above.

Information literacy operationalised as an individual/joint competence in a quasi-work environment

The analysis of questionnaire data on the allocation and execution of information activities within community councils points to the extent to which information literacy skills might be operationalised as an individual or joint competence in this quasi-work environment. Extracted from the quantitative data set, and presented in Table 4, are figures for information activities that are considered by community councillors to be completed individually themselves, jointly with others, and by other people. The activities correspond with those articulated in commonly cited educational models of information literacy such the SCONUL pillars (2011), and the CILIP information literacy themes (2018). For ease of reference, the appropriate SCONUL pillars have been included in the table.

| Activity | Likert scale. Activity completed… | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | Pillar | 5 ...independently | 4 ....mostly independently | 3 ...jointly | 2 ...mostly by another person | 1 ...by another person | Σ |

| In your community council, who decides the aims and methods for gathering information about local issues? | |||||||

| deciding the aims (what to do) | Scoping | 21 | 59 | 815 (85%) | 35 | 33 | 963 |

| deciding the methods (how to do it) | Planning | 22 | 91 | 786 (82%) | 33 | 31 | 963 |

| In your community council, who finds, edits and presents information about local issues? | |||||||

| finding information | Gather | 50 | 138 | 646 (67%) | 82 | 47 | 963 |

| finding local residents' opinions | Gather | 15 | 96 | 740 (77%) | 73 | 39 | 963 |

| editing information | Managing | 61 | 173 | 470 (49%) | 179 | 80 | 963 |

| presenting information | Presenting | 83 | 156 | 516 (54%) | 138 | 70 | 963 |

| In your community council, who decides that the community council has found enough information about local issues? | Evaluating* | 14 | 56 | 730 (84%) | 40 | 26 | 866** |

| * To establish that enough relevant information has been gathered. **This question had an unknown option, which was selected by 97 respondents | |||||||

The data in the highlighted column indicate that all activities bar one (editing information) are largely considered as collaborative endeavours in the community councils by the majority of questionnaire respondents.

Some study participants provided textual responses to the questions on the execution of information activities within community councils. From an analysis of these qualitative data, it is possible to assess further the extent of collaboration around information activities within community councils, and the levels of formality in such work. While the headline figures from the analysis of the quantitative data are emphatic, the analysis of the qualitative data reveals that the implementation of this joint activity is not straightforward: it depends on a range of information practices, as shown below.

Informal collaborative information work largely focuses on information sharing in face-to-face encounters. This happens, for example, in the street in small communities (‘Being a small community you meet fellow community councillors in the village’ Respondent 1096), or through the deployment of digital media (‘We interact via website, Facebook and Twitter… and are trialling Slack to make communication more efficient’ Respondent 1059). The respondents also mentioned collaborating over email frequently in their questionnaire returns. For example, Respondent 1265 noted:

We are fortunate that every member of our community council has access to email, so we do a lot of work ‘together’ by circulating emails and responding to them.

Amongst the more formal approaches to joint information activities, some community councils have established special interest groups. For example, Respondent 79 referred in the questionnaire return to ‘a subcommittee that look into planning matters’. In others, information gathering tasks are delegated to individual community councillors who then report back to the community council, as explained by Respondent 167:

We each have an area of responsibility. Information gathering and dissemination in that particular area is the individual’s responsibility. Any correspondence will come jointly from the community council.

In such cases, information work that has been completed by individuals with assigned areas of responsibility is packaged for onwards dissemination in a way that gives the impression of joint work, even though this is not strictly the case.

Office bearers play a greater role than their colleagues in preparing the information for onward dissemination, as explained by Respondent 497:

All members of the community council generally provide information obtained from their own contacts. Office-bearers generally co-ordinate activities relating to editing and presentation.

Conducting information work jointly in this way is valued because it allows for consent and consensus to be reached in groups. Respondent 1308, for example, highlighted that consensus is crucial to the community councillor role: I can only operate by consent.

In some community councils there may be a dependence on small number of active members (other than, or as well as, office bearers). This is illustrated in the comment below made by Respondent 975:

A number of our councillors are very passive and will just consume information, but a smaller number are more active, and we work collaboratively.

Similarly Respondent 443 admitted:

We have a small number of very active members who are working across sub-committees under Planning, Business, Environment and Youth to ensure that the community’s needs are communicated and responded to.

These findings on the collective endeavour of community councillors fit well with dominant messages from prior research on workplace information literacy, as reported above: that it is enacted in practice, and relates to the social environment in which information activities take place. They also articulate with arguments from the everyday information literacy literature which propose that information literacy should be primarily considered an attribute of groups, rather than of individuals (although in practice, it is both since group information literacy depends on skills of individuals brought together). On the basis of the analysis presented here, it can be argued that information activities conducted within community councils are collaborative, depend on social relationships and organisation, and lead to collective accomplishment.

Conclusion

The completion of this study has allowed for the investigation of the social context of the application of information literacy skills in a domain that has previously been unexplored in detail: the execution of quasi-work duties of elected representatives at the hyperlocal level of democracy. It offers a novel contribution on the source of competencies in information literacy to underpin collaborative information activities. The findings throw light on two research questions:

- What is the relative importance of life roles that shape the information literacy of Scottish community councillors?

- To what extent is information literacy operationalised an individual/joint competence in the quasi-work environment of a community council?

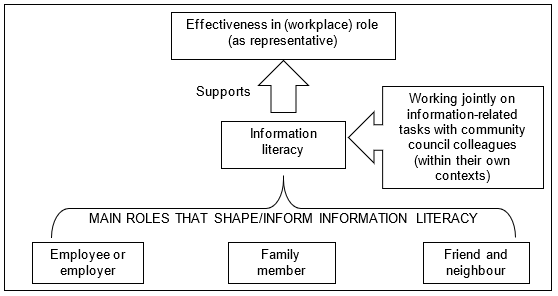

Figure 3 below summarises the main findings from this study in respect of Research Question 1. The life roles that appear to support the development of information literacy most readily amongst Scottish community councillors are those of employer/employee, family member, and friend or neighbour. The figure also highlights that the application of information literacy skills in joint activities with other hyperlocal representatives is important to the effective execution of the community representative role.

That roles related to employment, community and family, i.e. the workplace and everyday life, emerged as the most important in this study is significant. This is because, to date, the contribution of formal education is traditionally the main focus of research on the development of information literacy skills (for example, Sample, 2020). This evidence of the ready application of information literacy skills acquired in one environment to another is also noteworthy because this widens the debate as to the extent to which information literacy skills are specific to particular contexts.

Figure 3: Factors underpinning community councillors' effectiveness

Respondent profile, however, should be taken into account when considering the significance of these findings. It is possible that early life roles have an impact on the development of information literacy that is later mediated through post-educational experiences and/or lifelong learning. Most participants in this study were over 55 years old, therefore somewhat removed in time from their experiences of formal education and, as a result, may have underestimated the influence of their formative years in their questionnaire responses. Even so, it is important to bear in mind that this population is, in the main, highly educated and might be expected to be more conscious of, and value, education. While representing a limitation to this study, these issues illustrate the challenge of attempting objective measurement of perceptions across information literacy research that is undertaken in non-educational settings (Cruickshank and Hall, 2020). To address this, a similar study could be executed with attention paid to specific cohorts by age, ideally with reference to technological and societal changes that may have had an impact on the shaping of the information literacy of participants over their lifetime. At the same time, it would be worthwhile to extend the work beyond simply identifying the important life roles to exploring the reasons (a) why some appear to matter more than others, and (b) how individuals make these assessments of relative value.

In addressing Research Question 2, the analysis of the questionnaire data established that information activities in this community are carried out as a joint enterprise. When considering Research Question 2 directly, it has been demonstrated that information literacy in this context is also operationalised jointly amongst Scottish community councillors as they complete their duties. While this is not surprising in a study of information practices within a collective body, this finding adds to discussions of information literacy and collective accomplishments (Collard et al., 2016), and socially constructed sets of practices (Forster, 2017). It also points to areas for further investigation. A more extensive study could, for example, explore in detail the nature and structure of this joint work: the levels of formality in the allocation of roles; means by which decisions on the adequacy of information gathered are made (consensus or individual decision); and hierarchical structures in information work that are undertaken by volunteer community representatives. The practice of repackaging outputs of individual information work as that of the collective also merits particular attention. This work also raises other broader, yet related, questions for scrutiny in future research. For example, it would be worthwhile to consider the extent to which known facets of workplace information literacy and its application apply in other environments where the work is voluntary.

Acknowledgements

The work reported on in this paper was internally funded by Edinburgh Napier University through the project MILDEM: More information literacy in democratic engagement. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their feedback which led to a significant improvement on the original submission.

About the authors

Dr Hazel Hall is Professor of Social Informatics within the School of Computing at Edinburgh Napier University, Scotland and Docent in Information Studies at Åbo Akademi University, Finland. She holds a PhD in Computing from Napier University, an MA in Library and Information Studies from the University of Central England, and a BA (Spec Hons) in French from the University of Birmingham. Her research interests include information sharing in online environments, knowledge management, social computing/media, online communities and collaboration, library and information science research, and research impact. She blogs at http://hazelhall.org and can be contacted at h.hall@napier.ac.uk.

Peter Cruickshank is a Lecturer within the School of Computing at Edinburgh Napier University, United Kingdom. He has extensive experience in research into online participation and democratic engagement (e-participation), recently focusing on the information practice aspects, particularly around identity. He also has an active interest and delivers courses and lectures in information security and governance. He can be contacted at p.cruickshank@napier.ac.uk.

Dr Bruce Ryan is a Research Fellow in the Centre for Social Informatics within the School of Computing at Edinburgh Napier University, Scotland. His research interests include computing in hyperlocal democracy, information systems and information literacy within democratic units, library and information science, and information behaviour around self-healthcare. He blogs at https://bruceryan.info and http://blogs.napier.ac.uk/diabetes-research. He can be contacted at b.ryan@napier.ac.uk.

The mailing address for all authors is School of Computing, Edinburgh Napier University, 10 Colinton Road, Edinburgh EH10 5DT, UK.

References

- Ahmad, F. & Widén, G. (2018). Information literacy at workplace: the organizational leadership perspective. In Proceedings of ISIC, The Information Behaviour Conference: Part 1. Information Research, 23(4), paper isic1817. http://www.informationr.net/ir/23-4/isic2018/isic1817.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/74FAovLgA)

- Behrens, S.J. (1994). A conceptual analysis and historical overview of information literacy. College & Research Libraries, 55(4), 309-322. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl_55_04_309

- Bronstein, J., Aharony, N. & Bar-Ilan, J. (2018). Politicians’ use of Facebook during elections. Aslib Journal of Information Management,70(5), 551-572. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-03-2018-0067

- (2018). CILIP definition of information literacy 2018. CILIP. https://www.cilip.org.uk/news/421972/What-is-information-literacy.htm (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200718024313/https://www.cilip.org.uk/news/421972/What-is-information-literacy.htm)

- Collard, A-S., De Smedt, T., Fastrez, P., Ligurgo, V. & Philippette, T. (2016). How is information literacy related to social competences in the workplace? In S. Kurbanoğlu, J. Boustany, S. Špiranec, E. Grassian, D. Mizrachi, L. Roy & T. Çakmak (Eds.), Communications in Computer and Information Science (Vol. 676, pp. 79-88). Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52162-6_8

- Crawford, J. & Irving, C. (2009). Information literacy in the workplace: a qualitative exploratory study. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 41(1), 29-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0961000608099897

- Cruickshank, P. & Hall, H. (2020 in press). Talking to imagined citizens? Information sharing practices and proxies for e-participation in hyperlocal democratic settings. Information Research.

- Felstead, A. & Unwin, L. (2016). Learning outside the formal system - what learning happens in the workplace, and how is it recognised ? Government Office for Science, London. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/590493/skills-lifelong-learning-workplace.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20190725044510/https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/590493/skills-lifelong-learning-workplace.pdf)

- Ferguson, S. (2012). Are public libraries developers of social capital? A review of their contribution and attempts to demonstrate it. Australian Library Journal, 61(1), 22-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00049670.2012.10722299

- Ford, N. (2015). Introduction to information behaviour. Facet.

- Forster, M. (2015). Refining the definition of information literacy: the experience of contextual knowledge creation. Journal of Information Literacy, 9(1), 62-73. http://dx.doi.org/10.11645/9.1.1981

- Forster, M. (2017). Information literacy and the workplace: new concepts, new perspectives? In M. Forster (Ed.), Information Literacy in the Workplace (pp. 1-9). Facet Publishing.

- Forster, M. (2019). “Ethnographic” thematic phenomenography: a methodological adaptation for the study of information literacy in an ontologically complex workplace. Journal of Documentation, 75(2), 349-365. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JD-05-2018-0079

- Goldstein, S. & Whitworth, A. (2017). Determining the value of information literacy for employers. In M. Forster (Ed.), Information Literacy in the Workplace (pp. 67-84). Facet Publishing.

- Hall, H., Cruickshank, P. & Ryan, B. (2018). Exploring information literacy through the lens of activity theory. In S. Kurbanoğlu, J. Boustany, S. Špiranec, E. Grassian, D. Mizrachi & L. Roy (Eds.), Proceedings of the 5th European Conference on Information Literacy (ECIL2017) (pp. 803-812). Springer.

- Hall, H., Cruickshank, P. & Ryan, B. (2019). Practices of community representatives in exploiting information channels for citizen democratic engagement. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 51(4), 950-961. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0961000618769966

- Hollis, H. (2018). Information literacy as a measurable construct. Journal of Information Literacy, 12(2), 76-88. http://dx.doi.org/10.11645/12.2.2409

- Kauhanen-Simanainen, A. (2005). Collaborative information literacy by government. The IFLA Journal, 31(2), 183-187. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0340035205054883

- Kauhanen-Simanainen, A. (2007). Corporate literacy: discovering the senses of the organisation. Chandos Publishing.

- Killick, L., Hall, H., Duff, A. & Deakin, M. (2016). The census as an information source in public policy-making. Journal of Information Science, 42(3), 386-395. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0165551516628471

- Lloyd, A. (2004). Working (in)formation: conceptualizing information literacy in the workplace. In P.A. Danaher, C. Macpherson, F. Nouwens & D. Orr (Eds.), Proceedings of 3rd International Lifelong Learning Conference (pp. 218-224). Central Queensland University Press. http://acquire.cqu.edu.au:8080/vital/access/manager/Repository/cqu:1415 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20160117060319/http://acquire.cqu.edu.au:8080/vital/access/manager/Repository/cqu:1415)

- Lloyd, A. (2013). Building information resilient workers: the critical ground of workplace information literacy. What have we learnt? In S. Kurbanoğlu, E. Grassian, D. Mizrachi, R. Catts & S. Špiranec (Eds.), Worldwide commonalities and challenges in information literacy research and practice (pp. 219-228). Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-03919-0_28

- Lloyd, A. (2017). Information literacy and literacies of information: a mid-range theory and model. Journal of Information Literacy, 11(1), 91-105. http://dx.doi.org/10.11645/11.1.2185

- Lockerbie, H. & Williams, D. (2019). Seven pillars and five minds: small business workplace information literacy. Journal of Documentation, 75(5), 977-994. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JD-09-2018-0151

- Martzoukou, K. & Sayyad Abdi, E. (2017). Towards an everyday life information literacy mind-set: a review of literature. Journal of Documentation, 73(4), 634-665. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JD-07-2016-0094

- Olsson, M.R. (2014). Information practices in contemporary cosmopolitan civil society. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies Journal, 6(2), 79-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v6i2.3948

- Sample, A. (2020). Historical development of definitions of information literacy: a literature review of selected sources. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 46(2), 102116. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102116

- SCONUL. (2011). The SCONUL seven pillars of information literacy: core model for higher education. http://www.sconul.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/coremodel.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200715225649/https://www.sconul.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/coremodel.pdf)

- Smith, L. (2016). Information literacy as a tool to support political participation. Library and Information Research, 40(123), 14-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.29173/lirg722

- Theiner, P., Schwanholz, J. & Busch, A. (2018). Parliaments 2.0? Digital media use by national parliaments in the EU. In J. Schwanholz, T. Graham & P-T. Stoll (Eds.), Managing democracy in the digital age (pp. 77-95). Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61708-4_5

- Webber, S. & Johnston, B. (2017). Information literacy: conceptions, context and the formation of a discipline. Journal of Information Literacy, 11(1), 156-183. http://dx.doi.org/10.11645/11.1.2205

- Williams, D., Cooper, K. & Wavell, C. (2014). Information literacy in the workplace: an annotated bibliography. Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen. https://www.informall.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Workplace-IL-annotated-bibliography.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200730122938/https://www.informall.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Workplace-IL-annotated-bibliography.pdf)