Information behaviour and information practices of academic librarians: a scoping review to guide studies on their learning in practice

Marguerite A. Nel.

Introduction. This paper reports on a scoping review of the literature on the information behaviour and information practices of academic librarians to determine how their information activities are linked to knowledge and skills development (i.e., their learning).

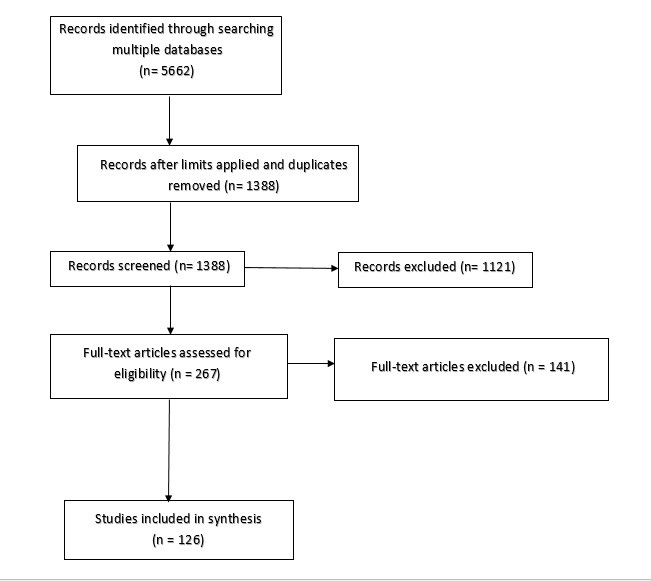

Method. A scoping study of peer reviewed scholarly papers published in English between 2000 and 2019 was conducted. Over 5600 papers, retrieved from seven scholarly databases, were screened, based on title, keywords and abstract, resulting in 126 papers for analysis.

Analysis. Data were extracted to provide an overview of the extent, range and scope of the selected literature. MS Excel and MS Word was used to sort, group and thematically analyse the data.

Results. The review provided valuable insight into the information behaviour and information practices of academic librarians. It also identified several information activities librarians engage in to ensure they have sufficient knowledge and skills (i.e., to learn) to cope with challenges in their work environment.

Conclusions. The scoping review served as a useful tool to get a notion of the scope of studies on the topic, addressing the research questions, and identifying opportunities for further investigation.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irisic2020

Introduction

The existence of academic libraries can be attributable to the value librarians are adding to teaching, learning and knowledge production and dissemination (Jubb, 2016). Librarians have always been mainly responsible for services such as collection development and acquisitions, cataloguing, circulation, reference and information literacy instruction and training (Allan, 2010; Atkinson, 2016; Cooke et al., 2011).

More recently, academic librarianship has been exposed to vast changes, as a result of stronger institutional focus on research, developments in higher education pedagogy, increased emphasis on research performance measurement and changes in scholarly communications (Bruns et al., 2015; Cox, 2016, 2017; Delaney and Bates, 2015; Hoodless and Pinfield, 2018; Koltay, 2016; Lang et al., 2018; McRostie, 2016; Mwaniki, 2018). Although there is still a need for traditional information services (Fourie and Du Bruyn, 2017; Hoffman et al., 2017), new opportunities emerged in which academic librarians may now develop their contributions stronger towards the shaping of research visions for universities (Appleton, 2018; Atkinson, 2016; White, 2017). Current reports highlight prominent roles in research data management, preservation and curation (Latham, 2017; Yu et al., 2017), research impact and evaluation (Braun, 2017; Thuna and King, 2017), open science and scholarly communication (Ogungbeni et al., 2018; Tenopir et al., 2017) and digital scholarship (Raffaghelli et al., 2016). These developments force libraries to form new partnerships and relationships (Cox et al., 2019; Cox, 2018; Haddow and Mamtora, 2017; Harland, 2017; Lang et al., 2018; McRostie, 2016), change the way they deliver services (Haddow and Mamtora, 2017; Klain Gabbay and Shoham, 2019; Koltay, 2016; Lang et al., 2018; McRostie, 2016), develop new strategies (Appleton, 2018; Cox et al., 2019; Cox, 2018; Pinfield et al., 2017) implement innovation and new technology (Chaithra and Pai, 2018; Joiner, 2018; Lee, 2018; Ponte et al., 2017) and assess current roles and practices (Gwyer, 2018; Johnson, 2019; Mwaniki, 2018). In this dynamic environment, it is understandable that some librarians might feel unprepared for new roles and responsibilities (Decker, 2017; Petek, 2018; Saunders, 2015), as change is more compelling than ever before.

Nevertheless, it seems that several libraries do manage to keep updated and are able to develop their services accordingly. The literature is infused with reports on how libraries effectively respond to opportunities (Lang et al., 2018; Mwaniki, 2018; Young, 2017). Yet, the literature on how librarians deal with new responsibilities and obtaining knowledge and expertise are less abundant, with even less reports on how they deal with their own information needs.

This motivated an investigation (scoping review) to determine the extent, range (variety), and scope (characteristics) of the evidence on the information behaviour and information practices of academic librarians.

Problem statement

The literature provides clear evidence that librarians are aware of the information needs of their users (Atkinson, 2016; Harland, 2017), yet, there are limited reports on how their own information needs are addressed. Given that they are working in information rich environments, where it is expected from them to be able to deal with sophisticated information questions, it can be assumed that academic librarians may face several information related challenges on a daily base. It is further expected from them to be innovative, up-to-date with new developments in the research arena and to play a leading role in implementing new technology in their workplace, but also to introduce users to this (Cox et al., 2019; Jantz, 2017; Joiner, 2018). How do they manage these expectations, and how do they ensure that they have sufficient knowledge and skills to cope with challenges and stay relevant?

A first approach would be to turn to the literature to determine what have been reported on the information behaviour and information practices of academic librarians and what can be learned from these studies. An initial overview might also enable the identification of areas in need of more empirical research and could provide a starting point for a deeper investigation of the current problem.

Research questions

With this in mind, a scoping review of the literature, guided by the following sub-questions was launched:

- What is the scope of studies investigating the information behaviour and information practices of academic librarians?

- What is reported on the information behaviour and information practices of academic librarians?

- How do academic librarians acquire knowledge, skills and expertise to align their information services to new developments and demands of the research environment?

In the following section, scoping review research as a methodology will be discussed. I will then briefly explains the main key concepts. This will be followed by a discussion of the methodology and the results of the scoping review.

Methodology

Scoping review research

Colquhoun et al. (2014:1294) define a scoping review as ‘a form of knowledge synthesis that addresses an exploratory research question aimed at mapping key concepts, types of evidence, and gaps in research related to a defined area or field by systematically searching, selecting, and synthesizing existing knowledge’. Hanneke et al. (2017:3) refer to it as ‘a literature mapping process that allows a researcher to examine the “landscape” of the literature based on a particular question of interest’. The purpose of conducting a scoping review may often be to ‘lay the groundwork for a more rigorous systematic review’, while other objectives can be to explore the extent of the literature, identify boundaries and parameters of a review, or to identify gaps in a body of literature (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005; Hanneke et al., 2017).

Evidence exists of scoping reviews in the academic library literature. Lorenzetti and Powelson (2015) report on a scoping review to explore practices and trends in library mentoring programmes, while Heyns et al. (2019) used this methodology to determine generational expectations of academic library leaders. O'Brien et al. (2017) found the methodology very useful to explore literature on individual differences in information seeking behaviour and information retrieval of people interacting with information and information systems.

The following stages, as proposed by Arksey and O'Malley (2005), will be followed to execute the current scoping review: identifying the research question; identifying relevant studies; study selection; charting the data; collating, summarising and reporting the results. The study was also guided by the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation, which was developed by Tricco et al. (2018). It is however important to first clarify relevant terminology.

Clarification of key concepts

Academic librarian

In this paper, an academic librarian will be viewed as a professional responsible for providing access to information and information sources as well as delivering services to support the information needs of students, staff, faculty, researchers as well as other users connected to a university or tertiary education institution. Other vocabulary often associated with this concept include research librarian, subject librarian, liaison librarian, reference librarian, information specialist, library and information professional and informationist.

Information behaviour

Several authors, including Bates (2017), Case and Given (2016), Courtright (2007), Savolainen (2007) and Wilson (2000) agree that human information behaviour includes the totality of activities involved in information seeking, information searching as well as supplying, using and sharing of information and can be both purposeful and passive. Information behaviour takes place within specific situations, contexts and in varied roles of people’s everyday lives (Savolainen, 2017). For the purpose of this paper, the following all-inclusive definition, by Fourie and Julien (2019, p. 693) will be used, which refers to information behaviour as ‘all information-related activities and encounters, including information seeking, information searching, browsing, recognising and expressing information needs, information encountering, information avoidance and information use’.

Information practices

It has been debated that, because of their generic nature, the two concepts, information behaviour and information practice are sometimes viewed as umbrella discourses, with little consensus on exact definitions for each concept (Savolainen, 2008; Wilson et al., 2009). Cox (2012:182) reasons the ongoing multivocality because ‘there is no one theorist to whom one can turn for a definitive account of the practice approach’. In this regard Cox (2012, p. 185) reasons that ‘all social practices involve information use, creation and seeking, but this does not make them information practices, because only a few practices are specifically information oriented’. Cox (2013, p. 61) therefore proposes the use of the phrase information in social practice as an umbrella term in preference to information behaviour or information practice.

In spite of these indecisive views, it was decided to use a definition of information practice, devising from collectivism and social constructionist. From this viewpoint, information practices can be defined as a ‘set of socially and culturally established ways to identify, seek, use and share the information available in various sources such as television, newspapers and the Internet’ (Savolainen, 2008, p. 2).

The framework for the literature search will be discussed as follows.

Literature search strategy

Table 1 presents the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the literature search, the databases used for the search, including the final version of the search strategy.

| Inclusion criteria |

Publication years 2000-2019 Peer-reviewed publications Full text English language |

| Exclusion criteria |

Grey literature, editorials, commentaries, letters, conference announcements or proceedings Book reviews Evidence-based library and information practice (EBLIP) Studies focussing on library products or services, reports on library projects or best practices as it relate to service delivery Studies focussing on other types of libraries (e.g., school or public libraries) Studies focussing on library users (not librarians) Library and information science schools or curricula Other |

| Databases |

EBSCOhost—Includes: Academic Search Complete, ERIC (Education Resource Information Center), Family & Society Studies Worldwide, Humanities Source, Library & Information Science Source, Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts Emerald Insight ProQuest—Includes: Humanities Index, SciTech Premium Collection, Social Science Premium Collection (which includes Education Collection, Library & Information Science Collection, Linguistics Collection, Politics Collection, Social Science Database, Sociology Collection) ScienceDirect Scopus Web of Science Core Collection |

|

Search string (final version) |

[(information behaviour) OR (information behavior) OR (information use) OR (information searching) OR (information seeking) OR (information need*) OR (information encountering) OR (information avoidance) OR (information sharing) OR (knowledge transfer) OR communication OR (information activities) OR (information practice*)] AND [academic OR research OR university OR universities OR (higher education)] AND [librarian* OR (information specialist*) OR (information professional*)] The search was applied to the title, keyword and abstract fields |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The search only included full text, peer reviewed scholarly papers published in English between 2000 and 2019. Grey literature, editorials or commentaries, letters, conference announcements or proceedings and book reviews were excluded. In addition, all papers focussing on Evidence-based library and information practice (EBLIP) were omitted. Evidence-based library and information practice (EBLIP) developed from Evidence-based medicine (EBM), which refers to the application of the interdisciplinary approach known as evidence-based practice (EBP). This movement claims that all practical decisions made within the library should be based on research studies and that these research studies should be selected and interpreted according to some specific norms stipulated for evidence-based practice (EBP) (Hjørland, 2011). A bibliometric study of practice theory in library and information studies performed by Pilerot et al. (2017) also omitted this term as it was viewed as unrelated to the topic of practice theory.

Other studies excluded include those focussing on products or services, reports on library projects, studies focussing on library users and other types of libraries (e.g., school or public libraries) and studies not focussing on information activities as main object.

Search results

Databases listed in Table 1 relate to the library and information science discipline. Each database has unique features and differ in terms of their use of controlled vocabulary, thesauri and coverage. To ensure that most papers on the topic were covered, Google Scholar was searched for cited and related papers, of which 75 were included to be reviewed (based on their titles). Study selection from each database is presented in Table 2.

| Database |

Papers identified in initial search |

After limited to inclusion criteria |

Duplicates removed |

Total included for reviewing |

Excluded |

Accepted for inclusion in synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

EBSCO Host (selected databases) |

1369 | 799 | 408 | 391 |

Best practices: 110 Book reviews: 1 Conferences / meetings: 15 EBLIP: 5 LIS schools or curricula: 25 User needs or studies: 174 Not academic libraries: 4 Other: 6 |

51 |

| Emerald Insight | 293 | 282 | 8 | 274 |

Best practices: 20 Book reviews: 3 Conferences / meetings: 2 EBLIP: 3 LIS schools or curricula: 1 User needs or studies: 152 Not academic libraries: 54 Other: 31 |

8 |

| ProQuest | 1549 | 31 | 3 | 28 |

Best practices: 1 Book reviews: 0 Conferences / meetings: 0 EBLIP: 0 LIS schools or curricula: 0 User needs or studies: 10 Not academic libraries: 3 Other: 0 |

14 |

| ScienceDirect | 1068 | 378 | 0 | 378 |

Best practices: 98 Book reviews: 0 Conferences / meetings: 1 EBLIP: 2 LIS schools or curricula: 12 User needs or studies: 122 Not academic libraries: 10 Other: 36 |

97 |

| Scopus | 734 | 154 | 0 | 154 |

Best practices: 32 Book reviews: 0 Conferences / meetings: 1 EBLIP: 10 LIS schools or curricula: 6 User needs or studies: 80 Not academic libraries: 10 Other: 3 |

12 |

|

Web of Science Core Collection |

521 | 89 | 1 | 88 |

Best practices: 8 Book reviews: 2 Conferences / meetings: 0 EBLIP: 3 LIS schools or curricula: 5 User needs or studies: 56 Not academic libraries: 3 Other: 1 |

10 |

| Google Scholar | 128 | 0 | 0 | 75 | 0 | 75 |

| TOTAL: | 5662 | 1733 | 420 | 1388 | 1121 | 267 |

Study selection

A single list was compiled of the selected studies from all databases. Duplicates were removed, resulting in a list of 267 full-text papers. Although the search terms appeared in the title, keyword or abstract fields, a closer reading of the full papers determined that some of these studies focused on the information needs of users or library activities (not on information activities), some reported on specific projects or programmes, and a few were authors’ opinions, and not considering information activities. From these, 141 papers were removed, resulted in the final list of 126 papers. This process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Flow diagram of scoping process

Data extraction and mapping

An Excel spreadsheet was used to extract data from the 126 selected papers. Based on the research questions, the following categories were created to guide the data analysis: journal title, year, country of origin of the first author, research approach, data collection method and main information activity (e.g., information seeking, information practice, information sharing, information usage and information needs). Data was further collated and categorised. The results of the scoping review will be discussed in the following section.

Results

Scope and labelling of studies

Although this study aims to gain insight on information behaviour and information practices as it has been theoretically defined, most selected papers focus on activities implied to be part of information practices (e.g. mentoring as a process of information sharing). This may link to arguments previously mentioned in this paper that ‘all social practices involve information use, creation and seeking, but this does not make them information practices, because only a few practices are specifically information oriented’ (Cox, 2012, p. 185). Since the aim of this review is to determine what librarians do to develop expertise in their workplace, it was decided to include all practices relating to information activities (although some may not explicitly be information practices per se).

The selected papers are spread over 51 journal titles. The Journal ofAcademic Librarianship seems to be the most popular source for authors, holding 34 of the 126 (27%) papers, followed by Library and Information Science Research (12/126; 10%); College and Research Libraries (7/126; 6%); Library Philosophy and Practice (6/126; 10%); Library Hi Tech (5/126; 4%) and Library Management (4/126; 3%). Other titles appear only once or twice on the list. The majority of these journals focus on practical applications significant to academic libraries (which are the nature of the reviewed literature).

Qualitative and quantitative research designs are equally represented with each consisting of 41% of the studies, while 18% of the reviewed studies followed a mixed methodology design. Questionnaires are the preferred method for data collection, utilised in 38% of the studies, followed by reports on case studies (14%), interviews (13%), literature reviews (10%) and citation analysis (5%). The following methods were also used once in the reviewed studies: a longitudinal case study, bibliometric analysis, citation analysis, researcher-as-participant self-reflection activities and a scoping review.

Several studies used a combination of methods, such as questionnaires and interviews (9%), questionnaires and citation analysis (2%), questionnaires, interviews and document research (1%), observations and interviews (1%), interviews and a citation analysis (1%), interviews and card sorting (1%), informal interviews and a report from a pilot project (1%), focus group interviews and personal logbooks (1%), and content analysis and citation analysis (1%).

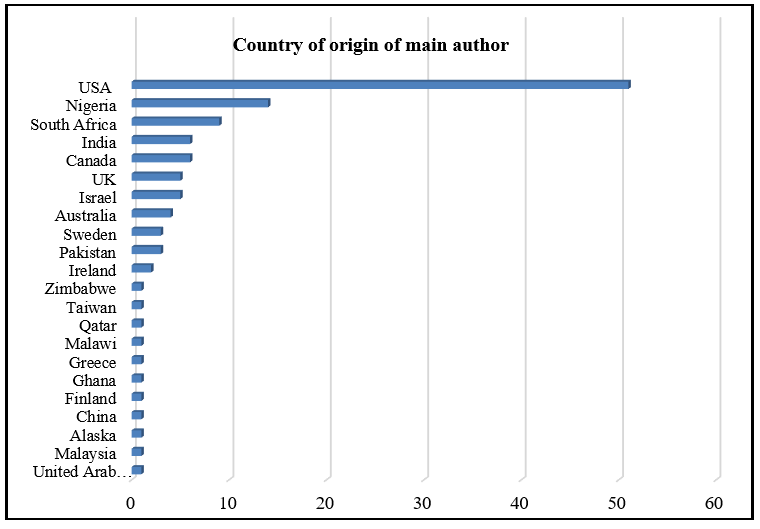

The country where a study was done may shed light on the context of a study (e.g., developing countries, opposed to developed countries). More than 50 per cent of the studies are from the United States (US). Countries represented in the studies are listed in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Countries represented in the selected studies (N = 126)

For 84 studies, librarians are the population of investigation, while five used librarians together with faculty, one educators, representatives of professional bodies and librarians and one library organizations. Another study used nursing students, a professor and a librarian. There is also one study, which collected data from undergraduate students together with librarians.

Information behaviour and information practices of academic librarians

The content of the selected papers was collated, categorised, and arranged according to main themes. This was analysed to determine what are reported regarding the information activities of academic librarians. The next section will report these findings.

Theoretical roots

| Theories | Examples of use |

|---|---|

| Transformational learning theory | (Attebury, 2017; Hess, 2015) |

| Communities of practice (Lave and Wenger) | (Belzowski, et al., 2013; Clifton, et al., 2017; Smith, 2016; Wittenberg, et al., 2018) |

| Social constructionism | (Boudreau et al., 2014; Julien and Given, 2002; Tewell, 2018) |

| Bandura's four sources of self-efficacy | (Bronstein and Tzivian, 2013) |

| Legitimate peripheral participation | (Dabengwa et al., 2019) |

| Social positioning theory | (Julien and Given, 2002) |

| Symbolic interactionism | (Julien and Pecoskie, 2009) |

| Social interaction as rituals of deference and demeanor (Goffman) | (Julien and Pecoskie, 2009) |

| Knotworking theory (cultural–historical activity theory) | (Kaatrakoski and Lahikainen, 2016) |

| organizational socialisation theory | (Lee et al., 2016) |

| Theory of work values | (Moniarou-Papaconstantinou and Triantafyllou, 2015) |

| Practice theory | (Brown and Ortega, 2005; Pilerot and Lindberg, 2018) |

| Diffusion of innovations theory | (Rodriguez, 2010) |

| Organizational lag model | (Rodriguez, 2010) |

| Information overload | (Shachaf et al., 2016) |

| Critical information literacy approach | (Tewell, 2018) |

| Zones of intervention (Kuhlthau) | (Fourie, 2013) |

| Zones of proximal development (Vygotsky) | (Fourie, 2013) |

Main focus of studies

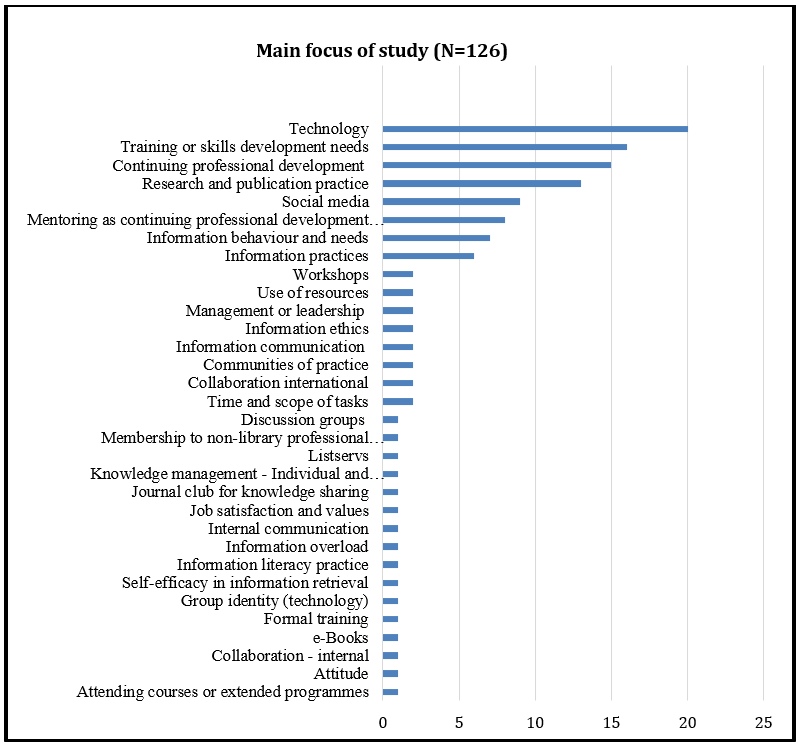

The content of each study was divided into categories according to the focus of the research (according to the researcher’s own interpretation). These concepts are listed, grouped, and illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Focus of studies (N = 126)

The focus of most of the reviewed studies is on information use – particularly on technology and information sources. Since an objective of this study is to determine what librarians do to obtain knowledge and skills in their workplace, their intentional information activities were used as categories in the analysis (e.g. discussion groups, listservs, journal clubs, etc.).

Focus on information activities

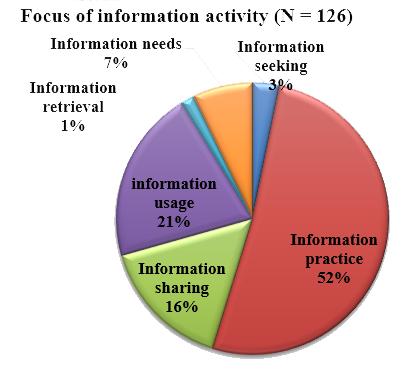

The next step was to determine what information activities were addressed in the different papers. This was determined by analysing the content of the papers. Some authors explicitly specify the broader term in the title, for example information behaviour (Fourie, 2012a; McDonald et al., 2015), information practice (Perryman, 2008) or information literacy practices (Anyaoku et al., 2015). Others refer to the specific information activity in the title, for example information seeking behaviour (Brown and Ortega, 2005) and information retrieval (Bronstein and Tzivian, 2013). Other authors focus on a combination of activities (e.g. information use and information sharing), for example in the study reported by Batool and Asghar (2012). A few authors also use the terms information behaviour and information practice as comprehensive or umbrella terms for various activities, without being specific e.g., Brown and Ortega (2005) and Perryman (2008). Several authors do not specifically refer to information behaviour and information practice per se, but the researcher used the definitions (explained previously in this paper) to categorise these papers according to information activity themes. These are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Focus on information activity (N = 126)

Specific focus related to information activities

The content of each paper was further demarcated to identify specific detail related to the information activities. Findings from these papers were grouped together under specific main themes and will be discussed in the following section.

Information needs

A few studies report on librarians’ needs for information to enhance their skills, as related to technology (Anyaoku et al., 2015; Enakrire, 2015; Haliso, 2011; Haneefa and Shukkoor, 2010; Hoskins, 2005; Husain and Nazim, 2015; Kaur and Gupta, 2015; Talab and Masoumeh, 2012) as well as their teaching roles (Carroll and Klipfel, 2019; Dabengwa et al., 2019; Julien and Pecoskie, 2009; Miller and Minkin, 2016; Snavely and Dewald, 2011). They also need information to improve their general work related abilities (Florance et al., 2002; Johnston and Williams, 2015; Klain-Gabbay and Shoham, 2016; Schrader et al., 2012; Wittenberg et al., 2018). The literature also indicate that the information needs of health librarians are similar to that of their users, but differ from those of other subject librarians (Carlyle, 2008; Wu et al., 2013).

Information seeking behaviour

The information seeking behaviour of academic librarians differ from those of their users (Hanz and McKinnon, 2018; McDonald et al., 2015; Perryman, 2008). Librarians tend to start their searches in library catalogues, and not in commercial databases or free websites, as noticeable from researchers and students (Hanz and McKinnon, 2018). They are feeling confident about their own information seeking behaviour and retrieval skills (Bronstein and Tzivian, 2013; Shachaf et al., 2016).

Information sharing

Librarians share information by means of participation in communities of practice (Belzowski et al., 2013; Delaney et al., 2020; Haliso, 2011; Smith, 2016), electronic mail (Chalmers et al., 2006; Flynn, 2005; Perryman, 2008), listservs (Julien and Given, 2002) and face-to-face meetings (Brown and Ortega, 2005; Chalmers et al., 2006; Keisling and Laning, 2016; Perryman, 2008; Pilerot and Lindberg, 2018). A large number of studies report on social media for information sharing (Adeyoyin, 2005; Aharony, 2009; Ahenkorah-Marfo and Akussah, 2016; Bar-Ilan, 2007; Costello and Bosque, 2010; Kim and Sin, 2016; Magoi et al., 2019; McIntyre and Nicolle, 2008; Okuonghae, 2018; Okuonghae et al., 2018; Quadri and Adebayo Idowu, 2016; Rodriguez, 2010). Although not their preferred method of information sharing, they also use short message service (SMS) (Batool and Asghar, 2012). They utilise personal communication (Brown and Ortega, 2005; Chalmers et al., 2006; Fyn, 2013; McDonald et al., 2015; Pilerot and Lindberg, 2018), online discussion groups (Bronstein and Tzivian, 2013; Brown and Ortega, 2005) and professional writing groups (Sullivan et al., 2013) to share information.

Technology plays an important role in the information activities of librarians and they know how to use it effectively (Adeyoyin, 2005; Ajayi et al., 2013; Ajegbomogun and Busayo, 2011; Boudreau et al., 2014; Chawinga and Selemani, 2017; Ejedafiru and Lucky, 2013; Igun, 2010; Mugwisi and Ocholla, 2003; Anasi et al., 2014; Ntui and Inyang, 2015; Oguche, 2017).

Information resources usage

To address their information needs, librarians will use library databases and collections (Hanz and McKinnon, 2018; McDonald et al., 2015), electronic books (Fourie, 2012a; Hanz and McKinnon, 2018) and scholarly journals (Brown and Ortega, 2005; Huang, 2014; McDonald et al., 2015; Mugwisi and Ocholla, 2003; Perryman, 2008; Sugimoto et al., 2014). They are also fond of using Google (Sorensen and Dahl, 2008).

Information practices

The reviewed papers revealed valuable information on the information practices of librarians. Academic librarians collaborate ( Anasi et al., 2014; Belzowski et al., 2013; Brown and Duke, 2005; Chang, 2016, 2017, 2018; Costello and Bosque, 2010; Dabengwa et al., 2019; Eddy and Solomon, 2017; Fourie, 2011, 2012b; Hart, 2000; Jamali, 2018; Magoi et al., 2019; Parrott, 2016; Smith, 2016; Spring et al., 2016) and socialise (Kaatrakoski and Lahikainen, 2016; Lee et al., 2016; Spring et al., 2016). Their information practices are shaped by norms (Adebayo and Mabawonku, 2017; Ferguson et al., 2016) and attitudes (Aharony, 2009; Hansson and Johannesson, 2013; Moniarou-Papaconstantinou and Triantafyllou, 2015). Several papers report on their information literacy practices (Anyaoku et al., 2015; Bewick and Corrall, 2010; Brown and Duke, 2005; Carroll and Klipfel, 2019; Delaney et al., 2020; Fourie, 2013; Hess, 2015; Hook et al., 2003; Julien and Genuis, 2011; Julien and Given, 2002; Julien and Pecoskie, 2009; Kim and Sin, 2016; Miller and Minkin, 2016; Snavely and Dewald, 2011; Sundin et al., 2008; Tewell, 2018). Doing research is also part of their work related practices (Bhardwaj, 2017; Chang, 2016, 2017, 2018; Dees, 2015; Hart, 2000; Jamali, 2018; Lyon et al., 2016; Powell et al., 2002; Schrader et al., 2012; Shao et al., 2018; Sugimoto et al., 2014; Sullivan et al., 2013; Watson-Boone, 2000).

Information activities linked to knowledge and skills development

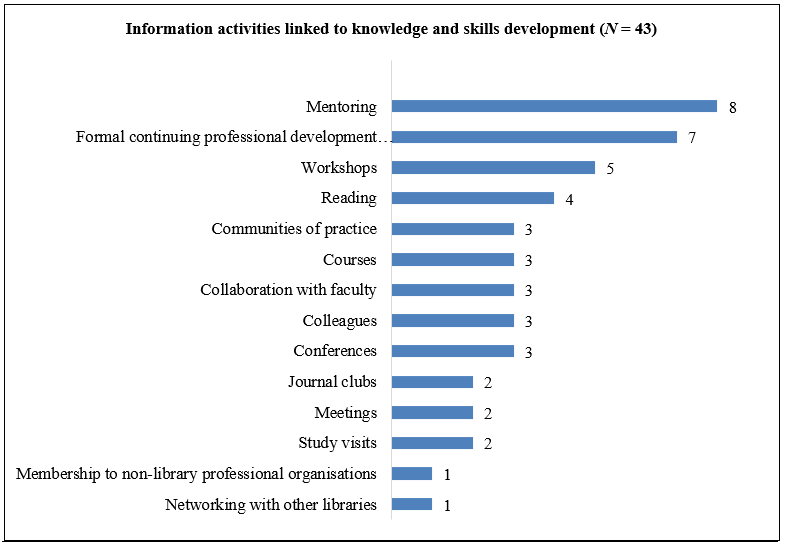

One of the main aims of this review is to determine how academic librarians obtain knowledge and skills. It is believed that learning and skills development takes place in daily practices in the workplace, of which the majority are informal and unintended (Aharony et al., 2017; Bruce et al., 2017; Forster, 2017; Lloyd, 2006, 2010, 2011a, 2011b). To determine what is reported on academic librarians’ information learning practices, papers related to learning and skills development were thematically analysed. Figure 5 provides a list of these themes, with the number of papers referring to the specific activity.

Figure 5: Information activity investigated (N = 43)

The majority of authors report on formal (intended) activities, such as mentoring (Bello and Mansor, 2013; Fiegen, 2002; Fyn, 2013; James et al., 2015; Jordan, 2019; Lee et al., 2016; Lorenzetti and Powelson, 2015; Mallon, 2014) and formal continuing professional development (CPD) programmes (Bello and Mansor, 2013; Bennett, 2011; Bewick and Corrall, 2010; Brantley et al., 2017; Chan and Auster, 2003; Cox et al., 2012; Hess, 2015). Some report on workshops (Booth and Brice, 2003; Delaney et al., 2020; Hook et al., 2003; Julien and Genuis, 2011; Ntui and Inyang, 2015) and reading (Hanz and McKinnon, 2018; Julien and Genuis, 2011; Perryman, 2008; Pilerot and Lindberg, 2018). There are three references to conferences (Lyons, 2007; Perryman, 2008; Pilerot and Lindberg, 2018) and communities of practice (Belzowski et al., 2013; Clifton et al., 2017; Smith, 2016). Other activities include courses (Brantley et al., 2017; Cox et al., 2012; Decker, 2017), collaboration with faculty (Belzowski et al., 2013; Brown and Duke, 2005; Julien and Given, 2002), colleagues (Eddy and Solomon, 2017; Hart, 2000; Pilerot and Lindberg, 2018), journal clubs (Barsky, 2009; Pilerot and Lindberg, 2018), participation in meetings (Keisling and Laning, 2016; Pilerot and Lindberg, 2018) and study visits (Bennett, 2011; Scherlen et al., 2009). Membership to non-library professional organizations (Bennett, 2011), and networking with librarians in other libraries (Smith, 2016) are other activities identified in the studies.

Discussion

This review scoped 126 papers to develop insight into the information behaviour and information practices of academic librarians.

Studies were spread over 51 journal titles, with the majority papers published in the Journal of Academic Librarianship. Researchers from the United States contributed more than half of these publications.

Studies followed qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods with the majority reporting on the utilisation of traditional methods, such as questionnaires and interviews, although a few endeavoured more innovative methods, such as the use of personal logbooks, card sorting and researcher-as-participant self-reflection. It would be worth exploring data collection methods other than questionnaires or interviews (where participants are reporting from their viewpoint), to see what results could be brought forward by looking from different perspectives (e.g., observations, photo ethnographic).

The majority of research report on practical challenges of librarians, with only a few referring to specific theoretical roots. This tendency confirms opinions by several researchers who are concerned with the difficulties in integrating theory to practice (Hider et al., 2019; Nguyen and Hider, 2018). This phenomenon may be a topic for future research.

The aim of this review was to learn more on the information behaviour and information practices of academic librarians. It is generally accepted that information behaviour is determined by, and takes place within, specific situations, contexts and in varied roles of people’s everyday lives (Savolainen, 2017). This scoping review indicated that context and work roles might define the information behaviour of librarians. Some findings, for example, show that health information specialists have similar information behaviour as the professionals they serve (Booth and Brice, 2003; Butler, 2019; Carlyle, 2008; Scherrer and Jacobson, 2002), while there are clear differences between the information seeking behaviour of physical science librarians and that of their users (Perryman, 2008). Most often, academic librarians will start their searches in library catalogues rather than commercial or free websites (as is the case with most library users) (McDonald et al., 2015), although they do use Google too (Sorensen and Dahl, 2008). They are also purposeful users of scholarly journals and e-books (Hanz and McKinnon, 2018; Perryman, 2008). They do thus use the sources they acquire, manage and promote as part of their work. This links to the concept community of justification, which refers to the tendency of a person to make use of the tools at hand within which he or she acts (Sundin and Johannisson, 2005; Sundin et al., 2008). This theory is also supported by findings of studies indicating that librarians conform to ethical practices (which they promote to users) in their own use of information (Ferguson et al., 2016). In line with their academic work environment, they are also doing research (Powell et al., 2002; Shao et al., 2018; Watson-Boone, 2000) and teach (Julien and Pecoskie, 2009). This can be further explained by the theory of symbolic interactionism, which rests on the notion that roles and identities are constructed and evolve through social interaction (Julien and Pecoskie, 2009), in this case with faculty at their institutions.

To address their information needs, librarians often prefer to use less formal information resources. Findings indicate preferences towards personal communication (e.g., electronic mail, face-to-face meetings), social media and other Web 2.0 tools, such as wiki’s and blogs (Aharony, 2009; Ahenkorah-Marfo and Akussah, 2016; Costello and Bosque, 2010; Magoi et al., 2019; Quadri and Adebayo Idowu, 2016).

Librarians are willing to learn and understand the importance of skills development. They therefore deliberately engage into formal programmes to improve themselves or their colleagues. A large number of authors report on mentoring to broaden skills and professional development of librarians (Bello and Mansor, 2013; Fiegen, 2002; Jordan, 2019; Lorenzetti and Powelson, 2015; Neyer and Yelinek, 2011). Mentoring, became an established practice in academic libraries, with a variety of such programs presented, ranging from formal one-on-one pairings to mentoring groups (Fyn, 2013). Librarians also read to stay updated (Bhardwaj, 2017; Perryman, 2008; Pilerot and Lindberg, 2018). Other formal learning opportunities include attendance of conferences, courses, study visits and workshops, as well as journal clubs, and membership to non-library professional organizations.

A few authors mention engaging in communities of practice for information sharing and learning (Belzowski et al., 2013; Clifton et al., 2017; Miller and Minkin, 2016). The community of practice concept refers to a group of individuals who share a common practice, with learning embedded in the community, marginalising the possibility of knowledge transfer either inwards or outwards (Lave and Wenger, 1999; Wenger, 1999). Several authors view communities of practice to be significant sites of learning, innovation and creativity in workplaces (Brown and Duguid, 2000; Talja, 2002; Vega and Quijano, 2010).

Collaboration and socialisation is part of librarians’ daily activities – this is how they address their information needs and learn to do new things (Belzowski et al., 2013; Corrall, 2014; Fourie, 2012b). In this regard, the reviewed literature provide various views on more informal ways of learning in the workplace. Librarians particularly learn by doing things together with their colleagues, participating in meetings, collaborating with faculty and socialising and networking with librarians from other libraries (Pilerot and Lindberg, 2018). This links to arguments by several authors (including Bruce et al., 2017; Forster, 2017; Lloyd, 2011a) that learning and knowledge transfer in the workplace is most of the time unintentional and function as part of day-to-day work life. They agree that information skills cannot be taught independently of the knowledge domains, organizations, and practical tasks in which these skills are used (Tuominen et al., 2005).

The scoping review provided useful insight into the information behaviour and information practices of academic librarians. Yet, there are gaps, which can be addressed by further research. A study comparing the information behaviour and information practices of academic librarians as it relates to different tasks and roles may provide even deeper insight into the different contexts of the work of librarians. This, for example may assist library management with strategic decisions, such as finding ways to enhance innovation from within teams (Ahmad et al., 2019; Gross, 2017) or the effective implementation of technology in work spaces (Lee, 2018; Papagiannidis and Marikyan, 2019). It may further add to the theoretical knowledge on tasks in information research contexts, as there are limited reference to this, except from Koltay (2016) and McDonald et al. (2015), who found that patterns in librarians' information behaviour at work and leisure are influenced by contextual variables, personal preferences and tasks. It would also be meaningful to investigate information practices of different functional groups in libraries.

Several papers discuss the use and application of information communication technology in librarian’s work and information activities (Ajegbomogun and Busayo, 2011; Ejedafiru and Lucky, 2013; Hoskins, 2005; Talab and Masoumeh, 2012). Yet some found that librarians need more training in information technology skills (Haneefa and Shukkoor, 2010; Ntui and Inyang, 2015). They also need training to prepare them for their work in information-rich environments and to participate as peers in problem solving, as well as to excel in teaching (Miller and Minkin, 2016). The work environment of academic librarians is technology driven, and it is expected from the library to drive innovation and to introduce new technology to the university community (Chaithra and Pai, 2018; Walwyn and Cloete, 2016), yet, several studies indicate a lack of essential skills to drive technology. Future research aiming to better understanding these needs might assist in identifying learning initiatives to enhance innovation and developing high-level technology skills.

Conclusion

The intention of this review was to get an overview of the scope of evidence on the information behaviour and information practices of academic librarians. The 126 selected papers provided valuable insight into these information activities as well as how it link to knowledge and skills development in their workplace.

In addition, this review identified opportunities for future research. With only a few studies based on theoretical frameworks, and a strong tendency towards practice-led research, the need for more integration and collaboration between theory and practice exists. Future research may also focus on task-based information practices as well as linking information practice research to innovation and technology.

The scoping review methodology succeeded in providing an overview of the nature of studies on the topic, while enough evidence was obtain to address the research questions and identifying opportunities for further investigation.

About the author

Marguerite Nel is a PhD candidate in the Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria, South Africa. She acts as Deputy Director responsible for information resources, access and operations in the Department of Library Services at the University of Pretoria and her research interests are in information behaviour, strategic management and library leadership and innovation. She can be contacted at marguerite.nel@up.ac.za

References

- Adebayo, J.O. & Mabawonku, I. (2017). Perception and practice of information ethics by librarians in four higher institutions in Oyo State, Nigeria. Library Philosophy & Practice, 1-31. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1574/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20190807232110/https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1574/)

- Adeyoyin, S.O. (2005). Information and communication technology (ICT) literacy among the staff of Nigerian university libraries. Library Review, 54(4), 257-266. https://doi.org/10.1108/00242530510593443

- Aharony, N. (2009). Web 2.0 use by librarians. Library & Information Science Research, 31(1), 29-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2008.06.004

- Aharony, N., Limberg, L., Julien, H., Albright, K., Fourie, I. & Bronstein, J. (2017). Information literacy in an era of information uncertainty. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 54(1), 528-531. https://doi.org/1002/pra2.2017.14505401063

- Ahenkorah-Marfo, M. & Akussah, H. (2016). Being where the users are: readiness of academic librarians to satisfy information needs of users through social media. Library Review, 65(8-9), 549-563. https://doi.org/10.1108/lr-02-2016-0020

- Ahmad, F., Widén, G. & Huvila, I. (2019). The impact of workplace information literacy on organizational innovation: an empirical study. International Journal of Information Management, 51, 102041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.102041

- Ajayi, S.A., Shorunke, O.A. & Akinola, A.O. (2013). Factors influencing the use of information communication technologies (ICT) by library personnel in college libraries in Osun and Oyo States, Nigeria. Information Technologist, 10(1), 143-156.

- Ajegbomogun, F.O. & Busayo, I.O. (2011). Information and communication technology (ICT) literacy among the staff of the libraries of Kenneth Dike and Nimbe Adedipe Universities, Nigeria: a comparative study. Information Studies, 17(2), 89-98.

- Allan, B. (2010). Supporting research students. Facet Publishing.

- Anasi, S., Akpan, I. J., & Titilayo, A. (2014). Information and communication technologies and knowledge sharing among academic librarians in south-west Nigeria: Implications for professional development. Library Review, 63(4/5), 352-369. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/LR-10-2013-0124

- Anyaoku, E.N., Ezeani, C.N. & Osuigwe, N.E. (2015). Information literacy practices of librarians in universities in South East Nigeria. International Journal of Library and Information Science, 7(5), 96-102. http://dx.doi.org/10.5897/IJLIS2014.0489

- Appleton, L. (2018). Positioning the academic library within the institution: structures and challenges. New review of academic librarianship, 24(3-4), 209-216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2019.1582078

- Arksey, H. & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-32. http://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Atkinson, J. (2016). Academic libraries and research support: an overview. In J. Atkinson (Ed.), Quality and the academic library (pp. 135-141). Elsevier. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-802105-7.00013-0

- Attebury, R.I. (2017). Professional development: a qualitative study of high impact characteristics affecting meaningful and transformational learning. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 43(3), 232-241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2017.02.015

- Bar-Ilan, J. (2007). The use of Weblogs (blogs) by librarians and libraries to disseminate information. Information Research, 12(4), paper 323. http://informationr.net/ir/12-4/paper323.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200715110929/http://informationr.net/ir/12-4/paper323.html)

- Barsky, E. (2009). A library journal club as a tool for current awareness and open communication: University of British Columbia case study. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library & Information Practice & Research, 4(2), 1-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v4i2.1000

- Bates, M.J. (2017). Information Behavior. In J.D. McDonald & M. Levine-Clark (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Library and Information Sciences (pp. 2074-2085). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1081/E-ELIS4

- Batool, S.H. & Asghar, A. (2012). Mobile phone text messaging use among university librarians of Lahore city. The International Information & Library Review, 44(3), 164-170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iilr.2012.07.003

- Bello, M.A. & Mansor, Y. (2013). Strengthening professional expertise: mentoring in knowledge transfer, the cataloguers' perspective. The International Information & Library Review, 45(3), 139-148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iilr.2013.10.006

- Belzowski, N., Ladwig, J.P. & Miller, T. (2013). Crafting identity, collaboration, and relevance for academic librarians using communities of practice. Collaborative Librarianship, 5(1), 2.

- Bennett, M.H. (2011). The benefits of non-library professional organization membership for liaison librarians. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 37(1), 46-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2010.10.006

- Bewick, L. & Corrall, S. (2010). Developing librarians as teachers: a study of their pedagogical knowledge. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 42(2), 97-110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0961000610361419

- Bhardwaj, R.K. (2017). Research activities of library and information science professionals in Indian Higher Educational Institutions: competencies, support and engagements. DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information Technology, 37(1), 30-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.14429/djlit.37.1.10672

- Booth, A. & Brice, A. (2003). Clear-cut?: facilitating health librarians to use information research in practice. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 20(Supplement 1), 45-52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2532.20.s1.10.x

- Boudreau, M-C., Serrano, C. & Larson, K. (2014). IT-driven identity work: creating a group identity in a digital environment. Information and Organization, 24(1), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2013.11.001

- Brantley, S., Bruns, T.A. & Duffin, K.I. (2017). Librarians in transition: scholarly communication support as a developing core competency. Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship, 29(3), 137-150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1941126X.2017.1340718

- Braun, S. (2017). Supporting research impact metrics in academic libraries: a case study. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 17(1), 111-127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.2017.0007

- Bronstein, J. & Tzivian, L. (2013). Perceived self-efficacy of library and information science professionals regarding their information retrieval skills. Library & Information Science Research, 35(2), 151-158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2012.11.005

- Brown, J. & Duguid, P. (2000). Organizational Learning and Communities of Practice: Toward a Unified View of Working, Learning, and Innovation. In E. L. Lesser, M. A. Fontaine, & J. A. Slusher (Eds.), Knowledge and Communities (pp. 99-121). Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Brown, J.D. & Duke, T.S. (2005). Librarian and faculty collaborative instruction: a phenomenological self-study. Research Strategies, 20(3), 171-190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resstr.2006.05.001

- Brown, C.M. & Ortega, U. (2005). Information-seeking behavior of physical science librarians: does research inform practice? College & Research Libraries, 66(3), 231-247. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl.66.3.231

- Bruce, C.S., Demasson, A., Hughes, H.E., Lupton, M., Sayyad Abdi, E., Maybee, C., Somerville, M.M. & Mirijamdotter, A. (2017). Information literacy and informed learning: conceptual innovations for IL research and practice futures. The Journal of Information Literacy, 11(1), 4.

- Bruns, T., Brantley, J.S. & Duffin, K. (2015). Bruns. The 21st Century Library: Partnerships and New Roles. Faculty Research and Creative Activity, 99. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/lib_fac/99

- Butler, R. (2019). Health information seeking behaviour: the librarian's role in supporting digital and health literacy. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 36(3), 278-282. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/hir.12278

- Carlyle, R. (2008). Educating a new profession: developing the communication and information management skills of health information specialists. Journal of Communication in Healthcare, 1(1), 68-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/cih.2008.1.1.68

- Carroll, A.J. & Klipfel, K.M. (2019). Talent, Schmalent: an instructional design/action research framework for the professionalization of teaching in academic libraries. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 45(2), 110-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.01.009

- Case, D.O. & Given, L.M. (Eds.). (2016). Looking for information: a survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behavior (4th. ed.). Emerald.

- Chaithra, G. & Pai, R.D. (2018). Libraries of the future: information technology as tool for transformation. Paper presented at the 3rd National conference on management of modern libraries (NACML), MAHE Manipal.

- Chalmers, M., Liedtka, T. & Bednar, C. (2006). A library communication audit for the twenty-first century. Portal: Libraries & the Academy, 6(2), 185-195. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.2006.0017

- Chan, D.C. & Auster, E. (2003). Factors contributing to the professional development of reference librarians. Library & Information Science Research, 25(3), 265-286. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-8188(03)00030-6

- Chang, Y-W. (2016). Characteristics of articles coauthored by researchers and practitioners in library and information science journals. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(5), 535-541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2016.06.021

- Chang, Y-W. (2017). Comparative study of characteristics of authors between open access and non-open access journals in library and information science. Library & Information Science Research, 39(1), 8-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2017.01.002

- Chang, Y-W. (2018). Exploring the interdisciplinary characteristics of library and information science (LIS) from the perspective of interdisciplinary LIS authors. Library & Information Science Research, 40(2), 125-134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2018.06.004

- Chawinga, W. & Selemani, A. (2017). Information and communication technologies in academic libraries: a comparative study. Innovation, 2017(55), 42-66.

- Clifton, S., Jo, P., Longo, J.M. & Malone, T. (2017). Cultivating a community of practice: the evolution of a health information specialists program for public librarians. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 105(3), 254-261. http://dx.doi.org/10.5195/JMLA.2017.83

- Colquhoun, H.L., Levac, D., O'Brien, K.K., Straus, S., Tricco, A.C., Perrier, L., Kastner, M. & Moher, D. (2014). Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(12), 1291-1294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013

- Cooke, L., Norris, M., Busby, N., Page, T., Franklin, G., Gadd, E. & Young, H. (2011). Evaluating the impact of academic liaison librarians on their user community: a review and case study. New review of academic librarianship, 17(1), 5-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2011.539096

- Corrall, S. (2014). Designing libraries for research collaboration in the network world: an exploratory study. Liber Quarterly, 24(1), 17-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.18352/lq.9525

- Costello, K. & Bosque, D. (2010). For better or worse: using wikis and blogs for staff communication in an academic library. Journal of Web Librarianship, 4(2/3), 143-160. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2010.502877

- Courtright, C. (2007). Context in information behavior research. Annual review of information science and technology, 41(1), 273-306. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/aris.2007.1440410113

- Cox, A., Pinfield, S. & Rutter, S. (2019). Academic libraries’ stance toward the future. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 19(3), 485-509. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.2019.0028

- Cox, A., Verbaan, E. & Sen, B. (2012). Upskilling liaison librarians for research data management. Ariadne, (70). http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue/70/cox-et-al/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20191225085519/http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue/70/cox-et-al/)

- Cox, A.M. (2012). An exploration of the practice approach and its place in information science. Journal of Information Science, 38(2), 176-188. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0165551511435881

- Cox, A.M. (2013). Information in social practice: a practice approach to understanding information activities in personal photography. Journal of Information Science, 39(1), 61-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0165551512469767

- Cox, J. (2016). Communicating new library roles to enable digital scholarship: a review article. New review of academic librarianship, 22(2-3), 132-147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2016.1181665

- Cox, J. (2017). New directions for academic libraries in research staffing: a case study at National University of Ireland Galway. New review of academic librarianship, 23(2-3), 110-124. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2017.1316748

- Cox, J. (2018). Positioning the academic library within the institution: a literature review. New review of academic librarianship, 24(3-4), 217-241. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2018.1466342

- Dabengwa, I.M., Raju, J. & Matingwina, T. (2019). Academic librarian's transition to blended librarianship: a phenomenology of selected academic librarians in Zimbabwe. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 45(4), 343-357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.04.008

- Decker, E.N. (2017). Encouraging continuous learning for librarians and library staff. Library Management, 38(6/7), 286-293. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/LM-10-2016-0078

- Dees, A.S. (2015). A bibliometric analysis of the scholarly publications of librarians at the University of Mississippi, 2008-2013. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(3), 241-245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.03.019

- Delaney, G. & Bates, J. (2015). Envisioning the academic library: a reflection on roles, relevancy and relationships. New review of academic librarianship, 21(1), 30-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2014.911194

- Delaney, M., Cleary, A., Cohen, P. & Devlin, B. (2020). Library Staff Learning to Support Learners Learning: Reflections from a Two-Year Professional Development Project. New review of academic librarianship, 26(1), 56-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2019.1681483

- Eddy, M.A. & Solomon, D. (2017). Leveraging librarian liaison expertise in a new consultancy role. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 43(2), 121-127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2017.01.001

- Ejedafiru, E.F. & Lucky, U.O. (2013). Attitude of professional librarians towards the use of information and communication technology (ICT) in Delta State University Library. International Research: Journal of Library and Information Science, 3(4).

- Enakrire, R.T. (2015). Using information and communications technologies in the University of Kwazulu-Natal and University of Ibadan Libraries. Mousaion, 33(4), 38-61.

- Ferguson, S., Thornley, C. & Gibb, F. (2016). Beyond codes of ethics: how library and information professionals navigate ethical dilemmas in a complex and dynamic information environment. International Journal of Information Management, 36(4), 543-556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.02.012

- Fiegen, A.M. (2002). Mentoring and academic librarians: personally designed for results. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 9(1), 23-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J106v09n01_03

- Florance, V., Giuse, N.B. & Ketchell, D.S. (2002). Information in context: integrating information specialists into practice settings. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 90(1), 49-58.

- Flynn, D.A. (2005). Seeking peer assistance: use of e-mail to consult weak and latent ties. Library & Information Science Research, 27(1), 73-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2004.09.005

- Forster, M. (2017). Information literacy in the workplace. Facet Publishing.

- Fourie, I. (2011). Personal information management (PIM), reference management and mind maps: the way to creative librarians? Library Hi Tech, 29(4), 764-771. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/07378831111189822

- Fourie, I. (2012a). A call for libraries to go green: an information behaviour perspective to draw interest from twenty-first century librarians. Library Hi Tech, 30(3), 428-435. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/07378831211266573

- Fourie, I. (2012b). Collaboration and personal information management (PIM). Library Hi Tech, 30(1), 186-193. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/07378831211213292

- Fourie, I. (2013). Twenty first century librarians: time for zones of intervention and zones of proximal development? Library Hi Tech, 31(1), 171-181. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/07378831311304001

- Fourie, I. & Du Bruyn, K. (2017). From a framework for advanced research information literacy skills to a map of opportunities to be addressed by academic librarians. Innovation: journal of appropriate librarianship and information work in Southern Africa, 2017(54), 4-30.

- Fourie, I. & Julien, H. (2019). Innovative methods in health information behaviour research. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 71(6), 693-702. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-11-2019-314

- Fyn, A.F. (2013). Peer group mentoring relationships and the role of narrative. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 39(4), 330-334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2012.11.016

- Gross, R. (2017). The links between innovative behavior and strategic thinking. Contemporary Management Research, 13(4), 239. http://dx.doi.org/10.7903/cmr.18056

- Gwyer, R. (2018). “This is an opportunity for librarians to reinvent themselves, but it is about moving out of their areas”: new roles for library leaders? New review of academic librarianship, 24(3-4), 428-441. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2018.1473258

- Haddow, G. & Mamtora, J. (2017). Research support in Australian Academic Libraries: services, resources, and relationships. New review of academic librarianship, 23(2-3), 89-109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2017.1318765

- Haliso, Y. (2011). Factors affecting information and communication technologies (ICTs) use by academic librarians in Southwestern Nigeria. Library Philosophy and Practice.

- Haneefa, M.K. & Shukkoor, C.K.A. (2010). Information and communication technology literacy among library professionals in Calicut University, Kerala. DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information Technology, 30(6), 55-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.14429/djlit.30.682

- Hanneke, R., Asada, Y., Lieberman, L., Neubauer, L.C. & Fagen, M. (2017). The scoping review method: mapping the literature in “structural change” public health interventions. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781473999008 (https://methods.sagepub.com/case/scoping-review-mapping-literature-structural-change-public-interventions)

- Hansson, J. & Johannesson, K. (2013). Librarians' views of academic library support for scholarly publishing: an every-day perspective. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 39(3), 232-240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2013.02.002

- Hanz, K. & McKinnon, D. (2018). When librarians hit the books: uses of and attitudes toward E-books. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 44(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2017.12.018

- Harland, F.M. (2017). How the university librarian ensures the relevance of the library to stakeholders: a constructivist grounded theory. (PhD), Queensland University of Technology. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/106745/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20180602033358/https://eprints.qut.edu.au/106745/)

- Hart, R.L. (2000). Collaborative publication by University librarians: an exploratory study. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 26(2), 94-99. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0099-1333(99)00145-7

- Hess, A.N. (2015). Equipping academic librarians to integrate the framework into instructional practices: a theoretical application. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(6), 771-776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.08.017

- Heyns, E.P., Eldermire, E.R.B. & Howard, H.A. (2019). Unsubstantiated conclusions: a scoping review on generational differences of leadership in academic libraries. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 45(5), 102054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.102054

- Hider, P., White, H. & Jamali, H.R. (2019). Minding the gap: investigating the alignment of information organization research and practice. Information Research, 24(3). http://informationr.net/ir/24-3/rails/rails1802.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20190818111355/http://informationr.net/ir/24-3/rails/rails1802.html)

- Hjørland, B. (2011). Evidence‐based practice: an analysis based on the philosophy of science. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(7), 1301-1310. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/asi.21523

- Hoffman, N., Beatty, S., Feng, P. & Lee, J. (2017). Teaching research skills through embedded librarianship. Reference Services Review, 45(2), 211-226. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/RSR-07-2016-0045

- Hoodless, C. & Pinfield, S. (2018). Subject vs. functional: Should subject librarians be replaced by functional specialists in academic libraries? Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 50(4), 345–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000616653647

- Hook, S.J., Stowell Bracke, M., Greenfield, L. & Mills, V.A. (2003). In-house training for instruction librarians. Research Strategies, 19(2), 99-127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resstr.2003.12.001

- Hoskins, R. (2005). Information and communication technology (ICT) knowledge and skills of subject librarians at the university libraries of KwaZulu-Natal. South African Journal of Libraries & Information Science, 71(2), 151-163. http://dx.doi.org/10.7553/71-2-619

- Huang, Y-H. (2014). Measuring individual and organizational knowledge activities in academic libraries with multilevel analysis. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(5), 436-446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.06.010

- Husain, S. & Nazim, M. (2015). Use of different information and communication technologies in Indian academic libraries. Library Review, 64(1/2), 135-153. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/LR-06-2014-0070

- Igun, S.E. (2010). Working experience and librarians' knowledge of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in Nigerian University Libraries. Library Philosophy & Practice, 1-4.

- Jamali, H.R. (2018). Use of research by librarians and information professionals. Library Philosophy and Practice, 1.

- James, J.M., Rayner, A. & Bruno, J. (2015). Are you my mentor? New perspectives and research on informal mentorship. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(5), 532-539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.07.009

- Jantz, R.C. (2017). Creating the innovative library culture: escaping the iron cage through management innovation. New review of academic librarianship, 23(4), 323-328. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2017.1388055

- Johnson, A.M. (2019). Connections, conversations, and visibility: how the work of academic reference and liaison librarians is evolving. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 58(2), 91-102. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/rusq.58.2.6929

- Johnston, N. & Williams, R. (2015). Skills and knowledge needs assessment of current and future library professionals in the state of Qatar. Library Management, 36(1-2), 86-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/LM-10-2014-0120

- Joiner, I.A. (2018). Emerging library technologies: it's not just for geeks. Chandos Publishing.

- Jordan, A. (2019). An examination of formal mentoring relationships in librarianship. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 45(6), 102068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.102068

- Jubb, M. (2016). Libraries and the support of University research. In J. Atkinson (Ed.), Quality and the Academic Library (pp. 143-156). Chandos Publishing.

- Julien, H. & Genuis, S.K. (2011). Librarians' experiences of the teaching role: a national survey of librarians. Library & Information Science Research, 33(2), 103-111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2010.09.005

- Julien, H. & Given, L.M. (2002). Faculty-librarian relationships in the information literacy context: a content analysis of librarians' expressed attitudes and experiences. Canadian Journal of Information and Library Science, 27(3), 65-87.

- Julien, H. & Pecoskie, J. (2009). Librarians' experiences of the teaching role: grounded in campus relationships. Library & Information Science Research, 31(3), 149-154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2009.03.005

- Kaatrakoski, H. & Lahikainen, J. (2016). “What we do every day is impossible”: managing change by developing a knotworking culture in an academic library. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(5), 515-521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2016.06.001

- Kaur, H. & Gupta, R. (2015). Information communication technology skills expertise of present day library professionals of Panjab University, Chandigarh: a case study. International Journal of Information Dissemination & Technology, 5(4), 270-275.

- Keisling, B. & Laning, M. (2016). We are happy to be here: the onboarding experience in academic libraries. Journal of Library Administration, 56(4), 381-394. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2015.1105078

- Kim, K-S. & Sin, S-C.J. (2016). Use and evaluation of information from social media in the academic context: analysis of gap between students and librarians. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(1), 74-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.11.001

- Klain-Gabbay, L. & Shoham, S. (2016). Scholarly communication and academic librarians. Library & Information Science Research, 38(2), 170-179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2016.04.004

- Klain Gabbay, L. & Shoham, S. (2019). The role of academic libraries in research and teaching. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 51(3), 721–736. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000617742462

- Koltay, T. (2016). Are you ready? Tasks and roles for academic libraries in supporting Research 2.0. New Library World, 117(1/2), 94-104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/NLW-09-2015-0062

- Lang, L., Wilson, T., Wilson, K. & Kirkpatrick, A. (2018). Research support at the crossroads: capability, capacity and collaboration. New review of academic librarianship, 24(3-4), 326-336. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2018.1460727

- Latham, B. (2017). Research data management: defining roles, prioritizing services, and enumerating challenges. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 43(3), 263-265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2017.04.004

- Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1999). Practice, person, social world. In H. Daniels (Ed.), An introduction to Vygotsky (Vol. 2, pp. 149-156). Routledge.

- Lee, J., Oh, S. & Burnett, G. (2016). Organizational socialization of academic librarians in the United States. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(4), 382-389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2016.04.011

- Lee, V.R. (2018). Libraries Will Be Essential to the Smart and Connected Communities of the Future. In V.R. Lee, & A.L. Phillips (Eds.), Reconceptualizing Libraries: perspectives from the information and learning sciences (pp. 25-32). London: Routledge.

- Lloyd, A. (2006). Information literacy landscapes: an emerging picture. Journal of Documentation, 62(5), 570-583. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00220410610688723

- Lloyd, A. (2010). Framing information literacy as information practice: site ontology and practice theory. Journal of Documentation, 66(2), 245-258. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00220411011023643

- Lloyd, A. (2011a). From skills to practice: how does information literacy happen? Journal of the Korean Society for Library and Information Science, 45(2), 41-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.4275/KSLIS.2011.45.2.041

- Lloyd, A. (2011b). Trapped between a rock and a hard place: what counts as information literacy in the workplace and how is it conceptualized? Library Trends, 60(2), 277-296. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/lib.2011.0046

- Lorenzetti, D.L. & Powelson, S.E. (2015). A scoping review of mentoring programs for academic librarians. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(2), 186-196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.12.001

- Lyon, L., Mattern, E., Jeng, W. & He, D. (2016). Investigating perceptions and support for transparency and openness in research: using card sorting in a pilot study with academic librarians. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 53(1), 1-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pra2.2016.14505301114

- Lyons, L.E. (2007). The dilemma for academic librarians with collection development responsibilities: a comparison of the value of attending library conferences versus academic conferences. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 33(2), 180-189. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2006.12.001

- Magoi, J.S., Aspura, M.Y.I. & Abrizah, A. (2019). Social media engagement in developing countries: boon or bane for academic libraries? Information Development, 35(3), 374-387. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0266666917748985

- Mallon, M.N. (2014). Stealing the limelight? Examining the relationship between new librarians and their supervisors. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(6), 597-603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.10.004

- McDonald, E., Rosenfield, M., Furlow, T., Kron, T. & Lopatovska, I. (2015). Book or NOOK? Information behavior of academic librarians. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 67(4), 374-391. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-12-2014-0183

- McIntyre, A. & Nicolle, J. (2008). Biblioblogging: blogs for library communication. The Electronic Library, 26(5), 683-694. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02640470810910701

- McRostie, D. (2016). The only constant is change: evolving the library support model for research at the University of Melbourne. Library Management, 37(6/7), 363-372. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/LM-04-2016-0027

- Miller, S.D. & Minkin, R.M. (2016). Qualitative teaching and learning needs assessment for a community of academic librarians. Journal of Library Administration, 56(4), 416-427. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2015.1112708

- Moniarou-Papaconstantinou, V. & Triantafyllou, K. (2015). Job satisfaction and work values: investigating sources of job satisfaction with respect to information professionals. Library & Information Science Research, 37(2), 164-170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2015.02.006

- Mugwisi, T. & Ocholla, D.N. (2003). Internet use among academic librarians in the Universities of Zimbabwe and Zululand. Libri, 53(3), 194-201. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/LIBR.2003.194

- Mwaniki, P.W. (2018). Envisioning the future role of librarians: skills, services and information resources. Library Management, 39(1/2), 2-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/LM-01-2017-0001

- Neyer, L. & Yelinek, K. (2011). Beyond boomer meets NextGen: examining mentoring practices among Pennsylvania academic librarians. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 37(3), 215-221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2011.02.013

- Nguyen, L.C. & Hider, P. (2018). Narrowing the gap between LIS research and practice in Australia. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 67(1), 3-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2018.1430412

- Ntui, A.I. & Inyang, C.L. (2015). Utilization of information and communication technology (ICT) resources and job effectiveness among library staff in the University of Calabar and Cross River University of Technology, Nigeria. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(6), 102-105.

- O'Brien, H.L., Dickinson, R. & Askin, N. (2017). A scoping review of individual differences in information seeking behavior and retrieval research between 2000 and 2015. Library & Information Science Research, 39(3), 244-254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2017.07.007

- Oguche, D. (2017). Impact of information and communication technology (ICT) literacy competence on job performance of librarians in Federal University Libraries in Nigeria. Information Technologist, 14(1), 54-67.

- Ogungbeni, J.I., Obiamalu, A.R., Ssemambo, S. & Bazibu, C.M. (2018). The roles of academic libraries in propagating open science: a qualitative literature review. Information Development, 34(2), 113-121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0266666916678444

- Okuonghae, O. (2018). Librarians' awareness of social media usage for informal scientific communication in university libraries in south-south, Nigeria. Library Philosophy & Practice, 1-35.

- Okuonghae, O., Achugbue, E. & Ogbomo, M.O. (2018). Librarians, use of social media for informal scientific communication in university libraries in south-south Nigeria. Library Philosophy & Practice, 1-20.

- Papagiannidis, S. & Marikyan, D. (2019). Smart offices: a productivity and well-being perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 51, 102027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.10.012

- Parrott, J. (2016). Communication and collaboration in library technical services: a case study of New York University in Abu Dhabi. New review of academic librarianship, 22(2-3), 294-303. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2016.1181663

- Perryman, C. (2008). The information practices of physical science librarians differ from those of the scientific community: more research is needed to characterize specific information seeking and use. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 3(3), 57-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.18438/B8KK7J

- Petek, M. (2018). Stress among reference library staff in academic and public libraries. Reference Services Review, 46(1), 128-145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/RSR-01-2017-0002

- Pilerot, O., Hammarfelt, B. & Moring, C. (2017). The many faces of practice theory in library and information studies. Information Research, 22(1), 1-16. http://informationr.net/ir/22-1/colis/colis1602.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20190810190658/http://www.informationr.net/ir//22-1/colis/colis1602.html)

- Pilerot, O. & Lindberg, J. (2018). Inside the library: academic librarians’ knowing in practice. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 50(3), 254-263. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0961000618769970

- Pinfield, S., Cox, A. & Rutter, S. (2017). Mapping the future of academic libraries: a report for SCONUL.

- Ponte, D., Mierzejewska, B.I. & Klein, S. (2017). The transformation of the academic publishing market: multiple perspectives on innovation. Electronic Markets, 27(2), 97-100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12525-017-0250-9

- Powell, R.R., Baker, L.M. & Mika, J.J. (2002). Library and information science practitioners and research. Library & Information Science Research, 24(1), 49-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-8188(01)00104-9

- Quadri, G.O. & Adebayo Idowu, O. (2016). Social media use by librarians for information dissemination in three Federal University Libraries in Southwest Nigeria. Journal of Library & Information Services In Distance Learning, 10(1-2), 30-40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2016.1156597

- Raffaghelli, J.E., Cucchiara, S., Manganello, F. & Persico, D. (2016). Different views on digital scholarship: separate worlds or cohesive research field? Research in Learning Technology, 24(1), 32036. http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v24.32036

- Rodriguez, J. (2010). Social software in academic libraries for internal communication and knowledge management: a comparison of two Reference Blog Implementations. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 15(2), 107-124. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10875301003788323

- Saunders, L. (2015). Academic libraries' strategic plans: top trends and under-recognized areas. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(3), 285-291. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.03.011

- Savolainen, R. (2007). Information behavior and information practice: reviewing the “umbrella concepts” of information-seeking studies. The Library Quarterly, 77(2), 109-132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/517840

- Savolainen, R. (2008). Everyday information practices: a social phenomenological perspective. Scarecrow Press.

- Savolainen, R. (2017). Information need as trigger and driver of information seeking: a conceptual analysis. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 69(1), 2-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-08-2016-0139