The perceived value of the academic library: a systematic review

Tove Faber Frandsen and Kristian Møhler Sørensen.

Introduction. Academic libraries increasingly need to justify their contributions to their funding institution. Data on the impact and value of the library serves to render libraries' value visible. This review explores how funding institutions, the public, users and staff perceive the value of the academic library.

Method. Scopus, Library and Information Science Abstracts, and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global were used as data sources for the comprehensive search strategy.

Analysis. Study selection was done independently by two reviewers. Risk of bias criteria as well as a data extraction form was developed. Evaluation and data extraction were done by the first author and confirmed by the second author.

Results. The included studies use quantitative as well as qualitative methods. They focus on varying groups (e.g., international students, librarians, faculty members) from institutions all over the world (e.g., United States, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom).

Conclusions. A number of facets of values are identified and they can be described as input (resources, space and staff) and services. Furthermore, a number of the facets indicate that the values of academic libraries are not solely understood by their input and services.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper874

Introduction

Higher education institutions are struggling with the management of scarce resources and with justifying the need to maintaining or increasing the investment made in them. As the academic library serves the needs and priorities of its host institution (Rodger, 2009), libraries increasingly need to be able to demonstrate their contributions to institutional goals (Cox, 2018). However, institutions do not necessarily recognize the broader value of libraries (Delaney and Bates, 2015).

Hinderman (2005) recommends the use of outcome-based evaluation, which compares outcomes to the library's goals and mission. Although highly disputed, data on the impact and value of the library is no longer just nice to have; it is an essential management resource (Showers, 2015), and renders libraries' value visible. Library assessments 'has, over time, progressed from measuring inputs to gauging efficiency, then quality, to outcomes assessment' (Wallace, 2001, p.68). Furthermore, studies of impact are increasingly intended for higher-level administrators and tend to explore the impact of the library on institutional-level goals (e.g., student-centred outcomes) (Connaway, et al., 2017).

Markless and Streatfield (2017) call for theory-based evaluation as this approach uses a causal model between programme activities and desired ends to guide the evaluation. Kaufman and Watstein (2008) argue that libraries need to define outcomes relevant to their institution and measure their values. Town (2011) argues that there is a need for a broader assessment of the meaning of value and recognition that value is dependent on values sets or systems. Consequently, the first step in an evaluation of impact or value is to determine the desired ends. As pointed out by Hernon (2002) and Hernon and Nitecki (2001), many evaluation components exist, e.g., performance and outcomes measures, service quality, customer satisfaction and effectiveness. The relationship between these concepts is complex (Sputore and Fitzgibbons, 2017). ISO 16439 (2014, p.13) defines value as 'the importance that stakeholders (funding institutions, politicians, the public, users, staff) attach to libraries and which is related to the perception of actual or potential benefit'. Consequently, values can only be explored if stakeholders are asked.

Stenstrom et al. (2019) argue that value as a concept applied to libraries is highly complex and addresses both financial and social concerns. The former can be measured, whereas the latter is a product of the perceptions of stakeholders. Tenopir 2012) argues that value of libraries can be measured using implicit, explicit and derived values. Institutional missions vary and of course, academic libraries vary as well (Fraser, et al., 2002). How stakeholders perceive the value of the academic library is important to understand for libraries to be able to communicate their value to their funding institution. It may be that the perception of the value of the library differs among various stakeholder groups.

Kostagiolas and Asonitis (2009) stress that the traditional tools for value measurement will only provide a partial answer to the demand for proof of worth. They argue that the existing frameworks for assessing values fail to include intangible assets or broader definitions of value. Library value is also increased by staff capabilities and capacity, services, and the relationships with both its immediate stakeholders and broader society. Town (2011) argues that the definition of value is contextual and that valuation reflects values, and these are chosen. Because values are tied to people, it is necessary to gain insight into the shared beliefs inherent in values sets. Nitecki, et al. (2015) suggest the following important values: an informed citizenry, freedom of information, open and equitable access to knowledge and intellectual diversity. Mierzecka (2019) suggests the following areas of importance for researchers: general approach of scholars and librarians to cooperation, practices of research support, access to information resources adapted to scholars' needs, data curation support and publication strategies support. Furthermore, Bruff (2019) suggest articulating the value of student work and the library as laboratory, forum and archive. However, these values are not empirically identified in stakeholder groups. Urquhart (2015, p. 86) argues that '[o]nce library and information services have started to think about the various values that users attach to our services, we need to think thoroughly about perceived values.'

The aim of this review is thus to answer the following question: how do the stakeholders find value in the academic library?

Related literature

A number of initiatives exist to support academic libraries in demonstrating their value and impact. An example is the Value of Academic Libraries Initiative by the Association of College & Research Libraries (Oakleaf, 2010, p. 8) that aims to 'help academic librarians participate in the conversation and to identify resources to support them in demonstrating the value of academic libraries in clear, measurable ways'. Oakleaf suggests linking academic library outcomes to institutional outcomes within the following areas: student enrolment, retention and graduation rates, success, achievement, learning, engagement, as well as faculty research productivity, teaching, service, and the overarching institutional quality.

Another example is Lindauer (1998) who suggested key areas for the identification of library performance measures: (1) learning outcomes and enabling instructional outputs; (2) faculty/academic staff teaching effectiveness, scholarly productivity, and professional development; (3) institutional viability and vitality; (4) access, availability, and use of teaching-learning recourses; and (5) infrastructure-human resources, collections, and equipment/facilities. A final example is the perceived value framework of Holbrook's typology including three dimensions of perceived value: (1) extrinsic versus intrinsic value; (2) self-oriented versus other-oriented value; and (3) active versus reactive value (Holbrook, 1994; 1999). The dimensions are used to create a typology of perceived value containing the following values: efficiency, excellence, status, esteem, play, aesthetics, ethics and spirituality.

Schwieder and Hinchliffe (2018) suggest categorizing the studies of academic library value according to the level of analysis: small-scale studies that examine value perceived by a small group of students, single-institution studies that examine values perceived by larger student groups at a single university and multi-institution studies that analyse values perceived by students across several academic institutions. Urquhart (2015) offers an interpretation that enables an application of the typology for evaluation of library and information services. For a recent overview of other approaches to value-based evaluation models, the reader is referred to Urquhart (2018). Finally, Saracevic and Kantor (1997) suggest the following taxonomy of value in using library and information services:

- Reasons for using a library or information service (e.g., for a task, project or personal reasons)

- Interaction with a library service (e.g., availability or accessibility of resources, use)

- Results of using a library service (cognitive, affective, or expectations met).

De Jaeger (2017) argues that the advantages of combining data are noted only briefly in the ISO standard. Attempts include linking evidence of library use with student success data, indicating correlation but not causation (for recent examples see Murray, et al., 2016; Scott, 2017) and assessments of the economic value of libraries including return on investment methods (e.g., Hájek and Stejskal, 2015).

Studies of specific services or programmes are available in vast amounts (recent examples include Perrier, et al., 2018; Gross, et al., 2018). Performance and outcome assessments are plentiful, typically focusing on student retention or success (e.g., Murray, et al., 2016). Several reviews provide an overview of studies on performance and outcome measures (Powell, 1992; Wallace, 2001; Fraser, et al., 2002; Hart and Amos, 2014; Urquhart and Turner, 2016). Likewise, studies of performance and outcome measures fora specific service or programme are also reviewed (Schulte, 2012; Menchaca, 2014; Erlinger, 2018). Furthermore, Blummer and Kenton (2018) is an example of a review of studies addressing specific outcomes. Finally, Urquhart (2015) and Sputore and Fitzgibbons (2017) review the principles, practice and methods for impact assessment for academic libraries.

Connaway, et al. (2017) argue that there are few studies of how stakeholders perceive the value or impact of the academic library and how they prioritize these values or impacts. Unlike research libraries, how stakeholders perceive the values of public libraries has been investigated and reviewed. A recent narrative review of the values of public libraries by Stenstrom, Cole and Hanson (2019) categorizes them into these three types of support: personal advancement, vulnerable populations and community development. Furthermore, Aabø (2009) is the first meta-analytical review of library valuation studies and thirty-two of the thirty-eight explore value of public libraries. Two of the included studies concern academic libraries; however, they only focus on specific library services (Harless and Allen, 1999; Luther, 2008). However, there are no reviews summing up the studies of the stakeholder perceptions of the value of academic libraries.

Methods

Urquhart (2010) explores systematic reviewing, meta-analysis and meta-synthesis for evidence-based library and information science. Urquhart also outlines methods for meta-synthesis in various library and information science research fields. This study aims to identify how the stakeholders find value in the academic library and thus a meta-analysis is not likely to be relevant in this case.

This systematic review was conducted and reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement (Moher, et al., 2009) and the AMSTAR measurement tool (Shea et al., 2007).

Search strategy

We searched for eligible studies using Scopus, Library and Information Science Abstracts, and Proquest Dissertations on August 14, 2019. The search strategy was developed and validated using the capture-recapture technique as well as on the basis of retrieval of known items (Booth, 2010). The search strategies are available in Appendix 2. Citation searching using included studies as a starting point was conducted to find further potentially eligible studies (Scopus up to August 27, 2019.

Eligibility criteria

All primary studies were considered eligible for inclusion if they examined the viewpoints of stakeholders in regard to the value of academic libraries, whether it was the main focus of the study or one of several aims. All research designs were considered eligible. Review articles were excluded but reference lists were used to identify further potentially relevant studies. The search was restricted to peer reviewed publications in English.

For this review and its included studies, an academic library is defined as the library associated with a degree-granting institution of higher education. Consequently, studies on specific occupational groups (e.g., cataloguers), specific programmes (e.g., embedded programmes) or specific services (e.g., interlibrary loans) fall outside the scope of this review.

The primary outcome was to understand the facets of values of the academic library as perceived by the stakeholders. For the search strategy a broad definition of value was used to retrieve as many potentially relevant studies as possible (Appendix 2). This review focuses on values and consequently, studies on satisfaction with services, outcome assessments, effectiveness or user satisfaction levels are excluded.

Study selection

Following the AMSTAR recommendation (Shea et al., 2007), two reviewers independently agreed on a selection of eligible studies and achieved consensus on which studies to include. Following recommendations from the Cochrane Handbook (Higgens et al., 2011) study selection took place in two stages. First, titles and abstracts were examined to remove obviously irrelevant items. Second, full-text reports were examined to identify studies that met eligibility criteria. Furthermore, the Cochrane Handbook states that at the first stage numbers of records are sufficient for exclusions, whereas at the second phase a minimum of one explicit reason for their exclusion must be documented. Numbers and reason are provided in the supplemental material. Covidence systematic review software (www.covidence.org) was used to screen and select included studies.

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

A data extraction form was developed (Appendix 4) and was piloted on one of the included studies. One author extracted the data from the included studies and the other author confirmed the extracted data. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The data extraction form included information relating to the publication: title (title of paper, abstract, report), report ID (if there are multiple reports of this study), reference details, publication type (e.g., full report, abstract, letter), type of study, aim of study, participant description (total number, age, sex, ethnicity), institutions (library, location, quantity), outcomes and results.

Suitable existing risk of bias criteria were not available and consequently, a set of criteria had to be developed using a recent systematic review of the perceived value of public libraries (Sørensen, 2020) as inspiration. The risk of bias was then assessed using this set of criteria: (i) selection bias, (ii), a priori values bias and (iii) outlier values bias (Table 1). Each criterion consisted of a set of signalling questions and was assessed for a low, high, or unclear level of risk.

(i) Selection bias. There are many stakeholders to consider (e.g., politicians, staff, non-users) and they can have very different characteristics. Knowing the characteristics of the participants can help reduce the risk of bias as various stakeholder perspectives can be taken into account. Consequently, not considering the characteristics of participants was considered a high risk of bias.

(ii) A priori determined values. Some studies may ask participants to rank a set of already determined values, which may have an influence on the results (e.g., if the list of values put emphasis on certain aspects of the academic library or by introducing values on the list at various levels of specificity). Applying a list of predetermined values was considered a high risk of bias.

(iii) Outlier values. A stated value may be the opinion of just one individual or a segment of stakeholders. If generalizability for the found values was not analysed, this was considered a high risk of bias.

| Criteria | Support for judgment | Review authors' judgment |

|---|---|---|

| Selection bias (e.g., gender, ethnicity, non-users, library staff, politicians) | Describe the process of recruiting participants. Specifically, whether the participants can be considered representative of the population. | Selection bias due to inadequate selection of participants to represent views of specific stakeholder groups, which leads to overrepresentation of specific subjects. |

| A priori values bias | Describe whether the values found in the study are the results of the study or determined a priori. | The study draws values from previous research to be verified in the study. Therefore, the study is biased towards preliminary stated values and does not explore new or current aspects of values. |

| Outlier bias (e.g., in according to central and periphery values) | Describe if the study is ranking the values in lists of priorities or centrality. | The study does not consider the significance of found values and findings may thus include outliers due to lacking internal validity. |

Quantitative analyses were not performed as the included studies present lists of values that cannot be quantified. Consequently, the sections in the PRISMA 2009 checklist (Moher et al., 2009) that relates to meta-analysis are not followed in this systematic review.

Results

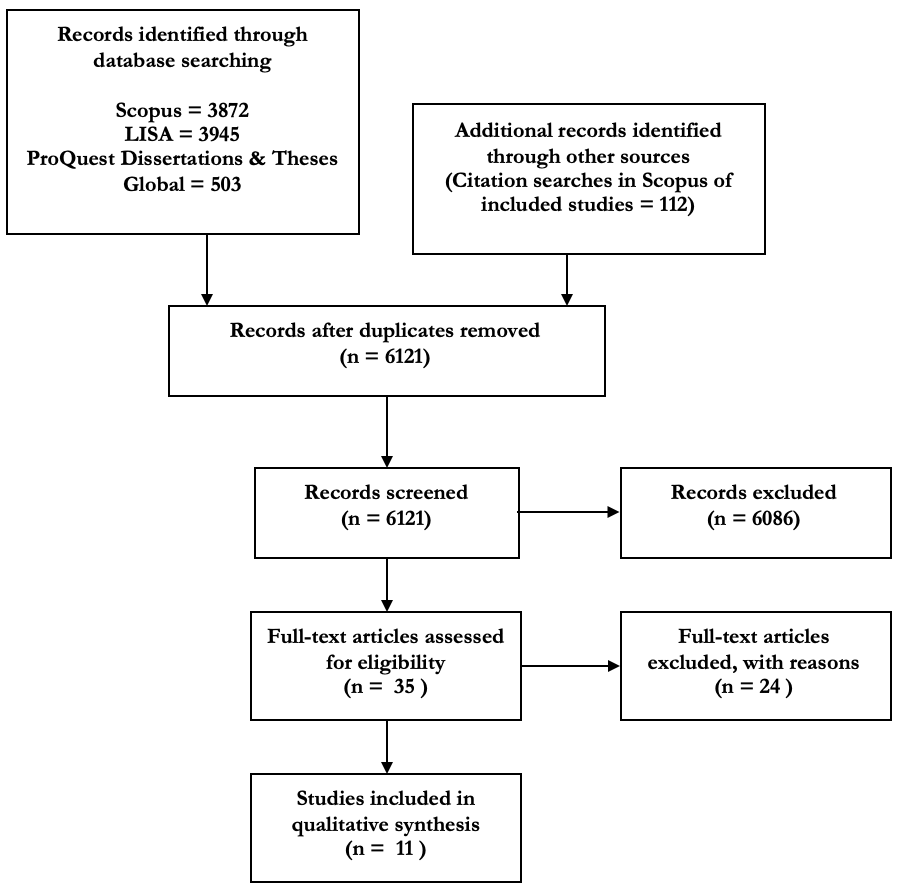

A total of 8,320 unique records were identified in the literature searches and an additional forty records were identified through citation searching (Figure 1). After removing duplicates 6,061 records were screened of which twenty-eight full-text articles for eligibility. Assessing the full text of the twenty-eight articles we found further studies not eligible for inclusion. Following PRISMA, the reasons for excluding at full text stage are available (see Appendix 3). In total, twenty-five were excluded due to the study's wrong outcomes, not being primary, being a duplicate, or having a focus on specific positions, programmes or services. Furthermore, a PhD thesis had to be excluded as it could not be obtained in full text. Therefore, eleven studies were included in the qualitative analysis. See the Appendix for an overview of the studies.

Figure 1: Study selection flow diagram.

Short descriptions of the studies are provided below.

Balog, Badurina and Lisek (2018) investigates the perceptions of 138 doctoral students at the Electrical Engineering and Computing faculty at the University of Zagreb. This mixed-methods explored the role of the academic library in supporting doctoral students' academic and research work. The results show that the students who uses the library appreciate the following:

- The availability of both library staff and information

- Speed of service

- Staff that is friendly, accommodating and courteous.

Furthermore, the study finds that the participants perceived library staff as a secure and competent resource to retrieve the information they need.

Connaway et al. (2017) analyses how academic libraries can communicate value to higher education stakeholders and how to increase learning and success amongst students. The study applies focus groups and semi-structured interviews of fourteen provosts and fourteen academic library administrators and finds multiple types of values as mentioned below:

- Communication

- Teaching and learning

- Collaboration

- Service

- Space

- Collection

- Student success

- Research support

- Inclusivity and diversity

- Provision of tech

- Teaching support

- Accreditation

Datig (2014) explores themes of international students' conceptualizations and envisions of libraries. The study methods consist of an online survey and individual interviews. Forty-two international students from New York University Abu Dhabi, located in the United Arab Emirates, completed the online survey. Seventeen international students participated in interviews. The survey and interview data were coded by the author using a grounded theory approach to qualitative analysis and the following themes emerged:

- A library is for books

- A library is for academics

- The library as place

- Librarians take care of books

- Culture of libraries

- Higher purposes of the library

Furthermore, the study finds that the international students perceived the library as an aspirational place and a place to preserve knowledge for the future.

Fowler (2016) explores the 'essence' and lived experienced with the library. The study is a qualitative, transcendental phenomenological study based on interviews and focus groups with eight-three participants (administration, researchers, students and management) from twenty-seven samples (convenience samples from public research universities in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States) and finds the following themes:

- The aspirational library

- The library as servant

- The commons

- Information resources

- Stewardship

Murray and Ireland (2018) analyses the results of a survey study of college and university provosts' and chief academic officers' preferences for communicating library impact. The study seeks to understand what types of data will help prioritise library budgets at an institution. Their results include a list of practices that can be used as evidence for advocating the prioritisation of academic library budgeting:

- Space

- Staffing

- Instructional outreach

- Resources

Nel and Fourie (2016) aims to demonstrate the value of using multiple methods for collecting data and planning services to meet current trends and informational needs of academic library users. Using questionnaires and focus groups, the study investigates the perceptions of 361 researchers at the Faculty of Veterinary Science at the University of Pretoria. In the investigation of the participants' information needs, information seeking and information use, a list of library assets emerged:

- Access to information and information resources (support with literature searches; excellent collections, inter-library lending)

- Affect of services (Good interactions, helpfulness, competent staff)

- Training and workshops

Nitecki and Abels (2013) explores a broad segment of academic library users' perceptions of the value of academic libraries in order to investigate the root causes of library values. The study analyses data from interviews and focus groups with participants from one United States university faculty, comprising researchers, teaching staff and administrative staff. Multiple themes were derived from the focus groups:

- To increase my productivity (e.g., could not do as much or as well without the library)

- To expand student ability to get information

- To do my job for teaching, research, and writing (e.g., prepare online class, write book chapters, prepare grant, save time)

- To save money (e.g., cannot afford to buy publications)

- To indulge intellectual curiosity

The interview data complemented these findings with the following aspects:

- To not feel frustrated (e.g., due to clunky process, hard to use or not intuitive interface, not sure how to search)

- To meet accreditation criteria specifically for faculty performance (e.g., to understand how to do research, publish, and present)

- To change the university (e.g., to change the way we think about learning and learning outcomes)

Furthermore, the study identifies a series of factors that enhance these values: information resources (archives, reserves, stacks, electronic); staff; access (circulation, inter-library lending, online catalogue); assistance (instruction and reference); purpose of use (e.g., reason to use the library); archival or historic value of student work; access to online materials and information; and the physical space for faculty and students.

Thompson (2014) analyses faculty use and perceptions of libraries using a survey sent to a random sample of non-librarian faculty members at colleges and universities in the United States that grant bachelor's degrees or higher, excluding faculty in the health sciences. A total of 1,531 respondents participate in the survey. The survey includes questions regarding five roles, which are:

- Gateway

- Buyer

- Archive

- Teaching Support

- Research Support

The analysis resulted in the development of two additional constructs in this area:

- Negative perceptions of the continuing relevance of libraries

- Perceived dependence on the library

Vaagan and Holm (2004) presents the results of a survey study of value orientation among Norwegian librarians, library staff and information professionals. The survey respondents include eighty-five college or university librarians. They find that the values prioritized are the following:

- Spreading information literacy

- Free access to materials and to information

- Spreading knowledge and literacy

The lowest ranked values are:

- Protection of user confidentiality

- Creation of culture of reading

- Encouragement of cultural diversity

Volentine and Tenopir (2013) explores the role of the academic library collections in teaching as well as research. The data is extracted from an open-ended survey sent to all academic staff members at six UK higher learning institutions. Over 2,000 academic staff members completed the survey, in which 941 comments were made. They analyse the role of the library by presenting anecdotal evidence that is not summarized in specific values.

Webb (2007) draws on personal experiences, unstructured short interviews and a workshop that explored the ways in which libraries support scholarship and enhance research activity. Describing researchers and their information needs informs the principles underlying libraries supporting research activity. The following roles are identified:

- Gatekeeper

- Translator

- Information specialist

- Subject expert

- Safe harbour

- The fount of all knowledge

- Counsel, colleague and critical friend

Qualitative synthesis

Design, choice of stakeholders, institutions and size varied considerably among the included studies (Appendix).

Study design. Four studies analysed the values of the academic libraries as perceived by stakeholders using surveys (Murray and Ireland, 2018; Thompson, 2014; Vaagan and Holm, 2004, Volentine and Tenopir, 2013). The latter survey primarily analysed the comments made in open-ended questions and did not include statistical analyses of the responses. Four studies used qualitative methods (Fowler, 2016; Nitecki and Abels, 2013; Connaway et al., 2017; Webb, 2007). Furthermore, three studies used mixed methods (Datig, 2014; Balog, et al., 2018; Nel and Fourie, 2016).

Choice of stakeholders. The majority of studies (6) analysed the perceptions of academic staff members or faculty members (Thompson, 2014; Volentine and Tenopir, 2013; Webb, 2007; Nel and Fourie, 2016; Nitecki and Abels, 2013; Balog, et al., 2018). Two studies analysed the perception of provosts (Murray and Ireland, 2018; Connaway, et al., 2017). The latter also included library administrators. Finally, one study analysed the perceptions of librarians (Vaagan and Holm, 2004). One study included representatives from a number of stakeholder groups (e.g., library directors, library staff, students and faculty members) (Fowler, 2016). One study included international students (Datig, 2014).

Institutions. Five studies include participants from institutions in the United States (Fowler, 2016; Thompson, 2014; Nitecki and Abels, 2013; Murray and Ireland, 2018; Connaway, et al., 2017). Two studies include participants from UK higher learning institutions (Volentine and Tenopir, 2013; Webb, 2007). The rest of the studies include participants from a number of different countries around the world: the United Arab Emirates (Datig, 2014), South Africa (Nel and Fourie (2016), Croatia (Balog, et al., 2018) and Norway (Vaagan and Holm, 2004).

Size. Six of the included studies have fewer than 100 participants (Datig, 2014; Vaagan and Holm, 2004; Fowler, 2016; Nitecki and Abels, 2013; Connaway, et al., 2017; Webb, 2007). Two survey studies have almost 1,000 and more than 1,500 responses respectively (Thompson, 2014; Volentine and Tenopir, 2013). The remaining three studies have 138 to 361 participants each (Balog, et al., 2018; Murray and Ireland, 2018; Nel and Fourie, 2016).

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias was assessed using three criteria: (i) selection bias, (ii), a priori values bias, (iii) outlier values bias. An overview of the assessments made is available in Table 2 and a detailed description of the risk of bias assessments can be found in the supplemental material.

| Study (Author, year) | Selection bias | A priori values bias | Outlier bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balog, et al. (2018) | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Connaway, et al. (2017) | Low | Low | Low |

| Datig (2014) | Low | Unclear | Unclear |

| Fowler (2016) | High | Unclear | Unclear |

| Murray and Ireland (2018) | Low | High | Low |

| Nel and Fourie (2016) | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Nitecki and Abels (2013) | High | Low | Low |

| Thompson (2014) | Low | High | Low |

| Vaagan and Holm (2004) | High | High | Low |

| Volentine and Tenopir (2013) | Unclear | Low | High |

| Webb (2007) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

There were several cases of unclear or high risk of bias with respect to all three criteria. The selection bias criterion showed low risk in six studies, unclear in two studies and high risk in three studies. Using the a priori values bias criterion it was revealed that five studies had low risk, whereas three studies had an unclear risk of bias and three studies had a high risk. Finally, using the outlier bias criterion it was revealed that five studies had a low risk, five studies had an unclear risk, and one study had a high risk.

Discussion and conclusion

This study aimed to determine the perceived values of academic libraries by stakeholders using systematic review methodology. Eleven studies were eligible for inclusion in the review.

Although rigorous methodology is used in the review process there are limitations. As there is no validated assessment tool suitable for the purpose, we developed our own set of risk of bias criteria. A validated tool strengthens the risk of bias assessment; however, our tool was not validated. Cochrane's risk of bias tool for assessing randomized trials is an example of a validated set of criteria (Higgins, et al., 2011). Using the developed set of three criteria, all eleven studies have a high risk of bias for one or two criteria. Some of the studies have determined the values a priori and are thus biased towards preliminary stated values, whereas new aspects of values are not explored. Furthermore, some studies include an unbalanced group of participants to represent views of specific stakeholder groups, which leads to overrepresentation of specific subjects. However, we also find studies with little risk of bias for all of the criteria.

Few similar reviews exist that can inform the discussion on which values stakeholders tie to the academic library. A recent review of the value of public libraries by Stenstrom, et al. (2019) categorizes the values in to these three types of support: personal advancement, vulnerable populations and community development. However, as the results are focused on public libraries, they are not easily transferable, which is also the case for Sørensen (2020) who reviews a wide variety of values from nineteen studies. However, the included studies in this review can also enlighten the discussion. Several issues are prominent: development over time, stakeholder foci, diversified terminology and perceptions of value.

The role of the academic library and the academic librarian is undergoing reconceptualization according to Llewellyn (2019). In this review the oldest study (Vaagan and Holm, 2004) seems to put emphasis on collections and information literacy. However, as the publications years range from 2004 to 2018, the time period is too short to make firm conclusions on development over time in the perception of the values of academic libraries.

Perceptions of some stakeholders have been investigated more than others. Generally, most of the studies explore the perception of researchers and faculty members. The perceptions of provosts have also been analysed in several studies, whereas library staff and students have been analysed less.

The terminology on values varies considerably. Although there is little evidence to support the metaphor often used of the library as the 'heart of the university' (Grimes, 1998), many similar metaphors exist which may be because of the difficulties of describing the actual values of the library. The included studies in this review use varying terminology to describe what ISO 16439 (2014) defines as the values of the library: perceptions, role, essence as well as value. Furthermore, the use of metaphors is widespread. Examples of metaphors include the fount of all knowledge, the gateway or the library as servant. The intangible values of the academic library can be difficult to describe and metaphors may describe it better.

These eleven studies show that perceptions of value, not just terminology, vary. However, there are some common denominators. Some of the studies focus on access to information and information resources (the library as archive, buyer) or as a space that is by the stakeholders. Many studies put emphasis on stewardship (spreading knowledge and information literacy). Consequently, collections and spaces are not are not enough when trying to grasp the values of the academic library. Outreach, training, support activities and the like are also important components in the understanding of the values. Furthermore, the library staff are also mentioned in several studies as a value. The participants in the included studies mention the competencies of the staff, their friendliness and the confidence that the library staff can secure access to all necessary information sources. Consequently, the library staff is of great importance to the values perceived by stakeholders.

The library is more than collections, services and staff. Several studies mention the aspirations of the library, the higher purpose and the library as counsel, colleague and critical friend. Fowler (2016) argues that libraries can begin focusing on fulfilling the need of the universities by realigning their purpose from collecting, preserving, and providing access to information to intersubjective communication. Fowler (2016, p. 79) describes intersubjective communication as '[th]e provocation and enabling of users to challenge their current knowledge in a manner that builds greater understanding.' Fowler argues that the library is a phenomenon, not the input (collections, buildings, staff). It is an experience that continues to evolve with every intentional act.

Summing up, these eleven studies on perceived values of academic libraries explore or assess the values of academic libraries. These studies are found when performing a comprehensive search strategy and duplicate study selection. A number of facets of values are identified in these studies and focus on what can be termed input: resources, space and staff. Services are also mentioned as a value of academic libraries. Furthermore, many of the included studies also report values such as the aspirational library, the library as counsel, colleague and critical friend indicating that the values of academic libraries are not solely understood by their input. The academic libraries may be understood as an experience or intersubjective communication.

About the authors

Tove Faber Frandsen is professor WSR at the University of Southern Denmark. She can be contacted at: t.faber@sdu.dk

Kristian Møhler Sørensen is PhD student at the University of Southern Denmark. He can be contacted at: krms@sdu.dk

References

Note: A link from the title is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Aabø, S. (2009). Libraries and return on investment (ROI): a meta-analysis. New Library World, 110(7/8), 311-324.

- Allard, S., Thura, M. R., & Feltner-Reichert, M. (2005). The librarian's role in institutional repositories: a content analysis of the literature. Reference Services Review, 33(3), 325-336. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320510611357

- Balog, K. P., Badurina, B., & Lisek, J. (2018). Information behavior of electrical engineering and computing doctoral students and their perception of the academic library's role: a case study in Croatia. Libri, 68(1), 13-32. https://doi.org/10.1515/libri-2017-0017

- Blummer, B., & Kenton, J. M. (2018). Academic libraries and student learning outcomes. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 19(1), 75-87. https://doi.org/10.1108/PMM-11-2017-0053

- Booth, A. (2010). How much searching is enough? Comprehensive versus optimal retrieval for technology assessments. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 26(4), 431-435. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462310000966

- Bruff, D. (2019). Students as producers: collaborating toward deeper learning. In A.S. Jackson, C. Pierard, and S.M. Schadl, (Eds.) Scholarship in the sandbox: academic libraries as laboratories, forums, and archives for student work. (pp. 1-15). Association of College and Research Libraries.

- Connaway, L.S., Harvey, W., Kitzie, V. & Mikitish, S. (2017). Academic library impact: improving practice and essential areas to research. Association of College & Research Libraries.

- Cox, J. (2018). Positioning the academic library within the institution: a literature review. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 24(3-4), 217-241. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2018.1466342

- Datig, I. (2014). What is a library?: international college students' perceptions of libraries. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(3-4), 350-356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.05.001

- de Jager, K. (2017). Approaches to impact evaluation in academic libraries: a review of a new ISO standard. IFLA Journal, 43(3), 282-287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0340035217696321

- Delaney, G., & Bates, J. (2015). Envisioning the academic library: a reflection on roles, relevancy and relationships. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 21(1), 30-51. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2014.911194

- Erlinger, A. (2018). Outcomes assessment in undergraduate information literacy instruction: a systematic review. College and Research Libraries, 79(4), 442-449. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.79.4.442

- Fowler, G. J. (2016). The essence of the library at a public research university as seen through key constituents' lived experiences. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Old Dominion University.

- Fraser, B. T., McClure, C. R., & Leahy, E. H. (2002). Toward a framework for assessing library and institutional outcomes. Portal, 2(4), 505-528. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2002.0077

- Grimes, D. J. (1998). Academic library centrality: user success through service, access, and tradition. Association of College and Research Libraries. (ACRL Publications in Librarianship, 50).

- Gross, M., Latham, D., & Julien, H. (2018). What the framework means to me: attitudes of academic librarians toward the ACRL framework for information literacy for higher education. Library & Information Science Research, 40(3-4), 262-268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2018.09.008

- Hájek, P., & Stejskal, J. (2015). Modelling public library value using the contingent valuation method: the case of the Municipal Library of Prague. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 47(1), 43-55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000614525217

- Harless, D.W. & Allen, F.R. (1999). Using the contingent valuation method to measure patron benefits of reference desk service in an academic library. College & Research Libraries, 60(1), 56-69. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.60.1.56

- Hart, S., & Amos, H. (2014). The development of performance measures through an activity based benchmarking project across an international network of academic libraries. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 15(1-2), 58-66. https://doi.org/10.1108/PMM-03-2014-0010

- Hernon, P. (2002). Outcomes are key but not the whole story. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 28(1/2), 5-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0099-1333(01)00301-9

- Hernon, P., & Nitecki, D. A. (2001). Service quality: a concept not fully explored. Library Trends, 49(4), 687-708, 778.

- Higgins, J. P. T, Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Jüni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., Savovic, J., Schulz, K. F., Weeks, & L., Sterne, J. A. (2011a). The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 343, d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928

- Higgins, J.P.T. & Green, S. (Eds.). (2011b). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/archive/v5.1/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/36guAgW)

- Hinderman, T. A. (2005). What is your library worth? Changes in evaluation methods for academic law libraries. Legal Reference Services Quarterly, 24(1-2), 1-40. https://doi.org/10.1300/J113v24n01_01

- Holbrook, M.B. (1994). The nature of customer value: an axiology of services in the consumption experience, in Rust, R. and Oliver, R.L. (Eds), Service quality: new directions in theory and practice.(pp. 21-71). Sage Publications,

- Holbrook, M.B. (1999). Introduction to consumer value. In M.B. Holbrook, (Ed.). Consumer value: a framework for analysis and research. (pp. 1-28). Routledge,.

- International Standards Organization. (2014). ISO 16439. Information and documentation - methods and procedures for assessing the impact of libraries. International Standards Organization.

- Kaufman, P., & Watstein, S. B. (2008). Library value (return on investment, ROI) and the challenge of placing a value on public services. Reference Services Review, 36(3), 226-231. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320810895314

- Kostagiolas, P. A., & Asonitis, S. (2009). Intangible assets for academic libraries: definitions, categorization and an exploration of management issues. Library Management, 30(6-7), 419-429. https://doi.org/10.1108/01435120910982113

- Lindauer, B. (1998). Defining and measuring the library's impact on campuswide outcomes. College & Research Libraries 59(6), 546-70. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.59.6.546

- Llewellyn, A. (2019). Innovations in learning and teaching in academic libraries: a literature review. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 25(2-4), 129-149. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2019.1678494

- Luther, J. (2008). University investment in the library: what's the return? A case study at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. LibraryConnect, Elsevier. https://libraryconnect.elsevier.com/sites/default/files/lcwp0101_1.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2U5jlSY)

- Markless, S., & Streatfield, D. (2017). How can you tell if it's working? Recent developments in impact evaluation and their implications for information literacy practice. Journal of Information Literacy, 11(1), 106-119. https://doi.org/10.11645/11.1.2201

- Menchaca, F. (2014). Start a new fire: measuring the value of academic libraries in undergraduate learning. Portal, 14(3), 353-367. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2014.0020

- Mierzecka, A. (2019). The role of academic libraries in scholarly communication. a meta-analysis of research. Studia Medioznawcze, 20(1), 99-112. https://bit.ly/2U6zHuG (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3eD4HM4)

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264-269. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

- Murray, A., Ireland, A., & Hackathorn, J. (2016). The value of academic libraries: library services as a predictor of student retention. College & Research Libraries, 77(5), 631-642. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.77.5.631

- Murray, A., & Ireland, A. (2018). Provosts' perceptions of academic library value & preferences for communication: a national study. College & Research Libraries, 79(3), 336-365. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.79.3.336

- Nel, M. A., & Fourie, I. (2016). Information behavior and expectations of veterinary researchers and their requirements for academic library services. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(1), 44-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.10.007

- Nitecki, D. A., & Abels, E. G. (2013). Exploring the cause and effect of library value. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 14(1), 17-24. https://doi.org/10.1108/14678041311316103

- Nitecki, D. A., Wiggins, J., & Turner, N. B. (2015). Assessment is not enough for libraries to be valued. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 16(3), 197-210. https://doi.org/10.1108/PMM-10-2015-0032

- Oakleaf, M. J. (2010). The value of academic libraries: a comprehensive research review and report. Association of College & Research Libraries. http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/issues/value/val_report.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3eFf16w)

- Perrier, L., Blondal, E., & MacDonald, H. (2018). Exploring the experiences of academic libraries with research data management: a meta-ethnographic analysis of qualitative studies. Library & Information Science Research, 40(3-4), 173-183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2018.08.002

- Powell, R. R. (1992). Impact assessment of university libraries: a consideration of issues and research methodologies. Library & Information Science Research, 14(3), 245-257.

- Rodger, E. J. (2009). Public libraries: necessities or amenities?. American Libraries, 40(8/9), 46-48. https://issuu.com/seanfitzpatrick/docs/0809/49?

- Saracevic, T., & Kantor, P. B. (1997). Studying the value of library and information services. Part II. Methodology and taxonomy. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 48(6), 543-563. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199706)48:6<543::AID-ASI7>3.0.CO;2-U

- Schulte, S. J. (2012). Embedded academic librarianship: a review of the literature. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 7(4), 122-138. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8M60D

- Schwieder, D., & Hinchliffe, L. J. (2018). A multilevel approach for library value assessment. College and Research Libraries, 79(3), 424-436. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.79.3.424

- Scott, R. E. (2017). Information literacy skills are positively correlated with writing grade and overall course performance. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 12(2), 157-159.S https://doi.org/10.18438/B8TT0G

- Shea, B. J., Grimshaw, J. M., Wells, G. A., Boers, M., Andersson, N., Hamel, C., Porter, A. C., Tugwell, P., Moher, D., & Bouter, L. M. (2007). Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 7, Article 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-7-10

- Showers, B. (Ed.). (2015). Library analytics and metrics: using data to drive decisions and services. Facet Publishing.

- Sputore, A., & Fitzgibbons, M. (2017). Assessing 'goodness': a review of quality frameworks for Australian academic libraries. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 66(3), 207-230. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2017.1344794

- Stenstrom, C., Cole, N., & Hanson, R. (2019). A review exploring the facets of the value of public libraries. Library Management, 40(6/7), 354-367 https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-08-2018-0068

- Sørensen, K. M. (2020). The values of public libraries: a systematic review of empirical studies of stakeholder perceptions. Journal of Documentation, 76(4), 909-927. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-10-2019-0201

- Tenopir, C. (2012), Beyond usage: measuring library outcomes and value. Library Management, 33(1/2), 5-13. https://doi.org/10.1108/01435121211203275

- Thompson, C. M. (2014). Disciplinary differences between faculty in library use and perceptions. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Missouri.

- Town, J. S. (2011). Value, impact, and the transcendent library: progress and pressures in performance measurement and evaluation. Library Quarterly, 81(1), 111-125. https://doi.org/10.1086/657445

- Urquhart, C. (2010). Systematic reviewing, meta-analysis and meta-synthesis for evidence-based library and information science. Information Research, 15(3) colis708. Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/15-3/colis7/colis708.html. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3leyld5)

- Urquhart, C. (2015). Reflections on the value and impact of library and information services. Part 1: value identification and value creation. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 16(1),86-102. https://doi.org/10.1108/PMM-02-2015-0005

- Urquhart, C. (2018). Principles and practice in impact assessment for academic libraries. Information and Learning Science, 119(1-2), 121-134. https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-06-2017-0053

- Urquhart, C., & Turner, J. (2016). Reflections on the value and impact of library and information services. Part 2: impact assessment. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 17(1), 5-28. https://doi.org/10.1108/PMM-01-2016-0001

- Vaagan, R., & Holm, S. (2004). Professional values in Norwegian librarianship. New Library World, 105, 213-217. https://doi.org/10.1108/03074800410536649

- Volentine, R., & Tenopir, C. (2013). Value of academic reading and value of the library in academics' own words. Aslib Proceedings, 65(4), 425-440. https://doi.org/10.1108/AP-03-2012-0025

- Wallace, V. E. (2001). Outcomes assessment in academic libraries: library literature in the 1990s. College and Undergraduate Libraries, 8(2), 59-71. https://doi.org/10.1300/J106v08n02_06

- Webb, J., Gannon-Leary, P., & Bent, M. (2007). Providing effective library services for research. Facet Publishing.

How to cite this paper

Appendix 1: Additional tables

| Study | Study design | Stakeholders | Participants | Institutions | Facets of values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balog, et al. (2018) | Quantitative and qualitative | Doctoral students | n=138 | The Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Computing (FEEC) of the University of Zagreb[…]. | They mostly praise the availability of both library staff and information, speed of service and staff that is friendly, accommodating and courteous. They appreciate the library staff and believe they are highly competent in finding information they need and are fairly convinced librarians can secure access to all necessary information sources. |

| Connaway, et al. (2017) | Qualitative: focus groups and semi-structured interviews | Focus group interviews with library administrators comprising the advisory group, and semi-structured individual interviews with their provosts. | n=14 library administrators n=14 provosts |

Fourteen institutions that include community colleges (n=2), four-year colleges (n=2), and research universities (n=10); the members were from secular (n=11), nonsecular (n=3), public (n=9), and private (n=5) institutions representing the four geographical regions of the United States[…]. | Communication Teaching and learning Collaboration Service Space Collection Student success Research support Inclusivity/Diversity Provision of tech Teaching support Accreditation |

| Datig (2014) | Mixed method study: an online survey and individual interviews | Students | N=42 international students completed the online survey. 17 international students participated in interviews. | New York University Abu Dhabi (NYUAD), located in the United Arab Emirates. | A library is for books A library is for academics The library as place Librarians take care of books Culture of libraries Higher purposes of the library |

| Fowler (2016) | A qualitative, transcendental phenomenological study | Executive officer, chief administrative officer, chief research officer, and chief student affairs officer, library director, library staff, faculty, graduate students, and undergraduate students. | N=83 to include representatives from each of the 27 samples. | Three public research universities in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States | The aspirational library The library as servant The commons Information resources Stewardship |

| Murray and Ireland (2018) | Survey study | […] [P]rovosts or chief academic officers | n=197 | […] [P]ublic and private (not-for-profit) colleges/universities with a Carnegie classification of master's or above […]. | Provosts provided examples that broadly championed the academic library trifecta: space, staffing and instructional outreach, and resources. |

| Nel and Fourie (2016) | Questionnaire and focus groups | V]eterinary researchers (masters and doctoral students and faculty/academic staff) and three information specialists from the Library. | n=361 | [T]he University of Pretoria | Access to information and information resources (support with literature searches; excellent collections, inter-library lending) Affect of services (Good interactions, helpfulness, competent staff) Training and workshops |

| Nitecki and Abels (2013) | Interview and focus groups | Faculty: tenure track research faculty, non-tenure track teaching faculty, and those with intense administrative responsibilities. | Interviews with 10 faculty members and a focus group composed of six members of the Library Advisory Group. | One US university | (1) To increase my productivity (e.g. could not do as much or as well without the library). (2) To expand student ability to get information. (3) To do my job for teaching, research, and writing (e.g. prepare online class, write book chapters, prepare grant, save time). Low value was noted when library is perceived as not needed to do work. (4) To save money (e.g. cannot afford to buy publications). (5) To indulge intellectual curiosity. (6) To (not) feel frustrated (e.g. due to clunky process, hard to use or not intuitive interface, not sure how to search). (7) To meet accreditation criteria specifically for faculty performance (e.g. to understand how to do research, publish, and present). (8) To change the university (e.g. to change the way we think about learning and learning outcomes). |

| Thompson (2014) | Survey | Faculty members | 1531 respondents | Colleges and universities in the United States that offer bachelor's degrees or higher, excluding faculty in the health sciences. | Gateway Buyer Archive Teaching Support Research Support Negative perceptions of the continuing relevance of libraries Perceived dependence on the library |

| Vaagan and Holm (2004) | Survey | Librarians | 85 respondents | Norwegian college/university libraries | Spreading information literacy Free access to materials and to information Spreading knowledge and literacy |

| Volentine and Tenopir (2013) | Survey collecting both qualitative and quantitative data | Academic staff members | 941 responses to open-ended questions | Six UK higher learning institutions | Anecdotal evidence that is not summarized in specific values |

| Webb (2007) | Personal experience, interviews and a workshop | Researchers at various career stages | Unknown | UK higher learning institutions | Gatekeeper Translator Information specialist Subject expert Safe harbour The fount of all knowledge Counsel, colleague and critical friend |

Appendix 2

Supplementary material – literature search

Appendix 3

Supplementary material – excluded studies

Appendix 4

Supplementary material – Data extraction form and risk of bias assessment