Data mining of Internet users' interests in diverse, hierarchical information needs

Adeola O. Opesade.

Introduction. Despite the wide use of the search engine Google to access the Internet, its ability to record users' digital traces amassed over time and make this available to the public, no known study has employed this resource to examine Internet users' information-seeking behavior. This study, using Google Trends data, investigates the use of the Internet for multiple hierarchical information needs in the developing country Nigeria.

Methods. A data-driven research method was used in this study. Data-driven research uses exploratory approaches to analyse big data to extract scientifically interesting insights.

Analysis. Microsoft Office Excel 2007 and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 17 were employed for data analyses. The former was used primarily for charting while the latter was used for other descriptive and inferential statistical analyses.

ResultsThe findings present profiles of Internet user groups through their levels of search interests in five diverse needs. It also revealed differing levels of interest in searching for the diverse needs. Furthermore, the result shows that there is a divide between the Northern and Southern parts of Nigeria.

ConclusionThe research extends studies in information seeking by utilising Web data to understand Internet users' information seeking behaviour in Nigeria.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper875

Introduction

Information seeking behaviour arises as a result of a need perceived by an information user, who, to satisfy that need, makes demands upon formal or informal information sources or services (Wilson, 1999). According to Case (2007), studies in information seeking behaviour have evolved over time; systematic research on the subject, particularly on the use of sources like books or newspapers, dates back nearly a century. In the first three decades of the twentieth century, studies of information channels and systems (mostly libraries and the mass media) accumulated slowly. By the 1960s, investigations, mainly of the specialised information needs and uses of scientists and engineers, were appearing regularly in journals and reports. Information seeking has grown into a topic that has been written about in over 10,000 documents from several information need perspectives.

While many sources of information are available and used by different categories of people as reported in previous studies (Burkell, et al., 2006; Wong and Sam 2010; Hersberger, 2001; Yusuf 2012; Ukachi, 2007), the pervasiveness of the Internet and its ability to deliver information on virtually any topic of interest with simple clicks of a button has made the World Wide Web (WWW) one of the most consulted sources of information. The Web has exploded into an information platform of tremendous importance, with several hundred million users and over a billion Web pages (Buscher, et al., 2009; Pitkow, et al., 2009).

The Web, although providing diverse information through different pages, has provided a single medium through which information can be sourced. While commenting on the evolution of information seeking behavior, due to the impact of the Web, Case stated:

Think back to a time before the World Wide Web was available. All of the information was out there in individual offices, filing cabinets, minds, and computers. But because it was divided by source, by location, by person, and by channel, it was not always easily located or examined. ' But now ... Not only have the different channels of communication collapsed down to one, but less goal-oriented behaviors, such as browsing, may play a larger role than ever before. Looking for information becomes more holistic. The contrast between new and old is even greater when we compare tasks in the office and classroom to their counterparts of 20 years ago. Obscure bits of information ' are more easily found in a single 'place''the Web. ' In a manner similar to the emergence of the World Wide Web, our view of information behavior has become more integrated and less dictated by sources and institutions. (Case, 2007, p. 4)

It thus appears that the wide acceptance and use of the World Wide Web as an information source for satisfying information needs have a potential to open a new paradigm in information behaviour studies; one that is holistic, more integrated and less dictated by sources. For example, in addition to identifying the preferred sources used to meet a particular information need as usually done in existing studies, can we begin to investigate the preferences in the use of a single information source (the World Wide Web) for various information needs? This appears a herculean task, particularly because of the need for data on the extent of use of that very source for information seeking for such diverse needs. Also, the conventional survey method used in previous studies might not be adequate for this type of study.

A panel session at the 1997 Association for Computing Machinery Special Interest Group on Research Issues in Information Retrieval Conference entitled Real life information retrieval: commercial search engines had in attendance, representatives from numerous Internet search services (Jansen, et al., 1998). In that session, Doug Cutting, representing Excite, one of the major Internet search services, graciously offered to make available for research, a set of user queries that had been submitted to his service. That singular act of benevolence to research and other similar acts have enabled a number of studies on users' searching behavior on the Web (Jansen, et al., 1998; Jansen, et al., 2000; Spink, et al., 2002a; Spink, et al., 2002b; Jansen and Spink, 2003; Jansen and Spink, 2005; Jansen, et al., 2005; Jansen, et al., 2008). Such important studies would not have been possible but for the generosity of commercial search engines to share their data. Unavailability and lack of access to adequate data can cause a hindrance to furthering studies on Web users' information seeking behaviour.

Auspiciously, the Web does not only provide an important information source, it is also an important source of publicly available data (Facca and Lanzi, 2005; Vaughan and Romero-Frías, 2014). As people turn to the Internet to search for heterogeneous information, their digital traces are aggregated and built into massive data that can be analysed to get insight into Internet users' behaviour. The most frequently used providers of Web data are social media such as Twitter and Facebook and search engines such as Google and Yahoo! (Kristoufek, 2013). Among these data sources, Google has consistently been put at the top; according to Internet Live Stats, 2014, Google was reported to have processed more than 66.7 per cent of all the online queries in the world in December 2012. In 2009, Google began to release its users' search queries through a publicly accessible interface named Google Trends (Carrière-Swallow and Labbé, 2013). Google Trends provides a search index for the queries based on geographical locat ions and time, effective from 2004 (Wu and Brynjolfsson, 2015). Furthermore, the world of science is changing with a new mode of data-driven science that is emerging within traditional disciplines, challenging established epistemologies across the sciences, social sciences and humanities, and engendering paradigm shifts across multiple disciplines (Gray, 2007, Kitchin, 2014).

Despite the enormous use of the Google search engine to access the Internet to search for information, its ability to record users' digital traces amassed over time and the emergence of the fourth dimension of science that is data-driven, no known published research has utilised this great resource for the study of Internet users' information seeking behaviour. There is neither a known information seeking behaviour study that has been based on the analysis of publicly available Web data in general nor the use of Google Trends Web data in particular. No known published research has also systematically investigated relative use of the Internet for multiple, hierarchical information needs. The present study, leveraging the epistemology of the emerging data-driven science and using Google Trends Web data, adapts Maslow's theory of hierarchy of motivation and Dervin's sense-making theory to investigate the use of the Internet for multiple hierarchical information needs in a developing country, Nigeria.

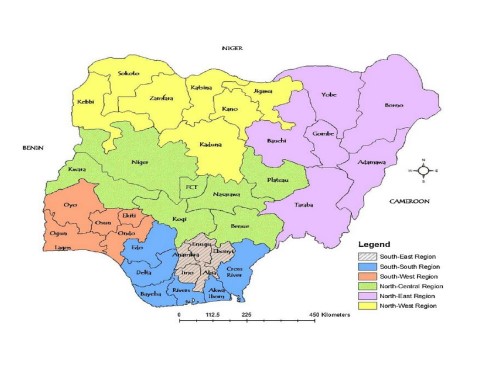

Nigeria is Africa's most populous country with over 160 million people and over forty million Internet users, the largest number of Internet users from a single country in the African continent. The growth of Internet usage in the country continues to increase, recording over 90% growth rate between 2000 and 2008 (Ayo, et al., 2011). Nigeria is also a multicultural and multi-linguistic nation divided into thirty-six states (with differing socio-economic status) and a Federal Capital Territory. All the states and Federal Capital Territory, shown in Figure 1, are further constituted into six geopolitical zones, namely, North Central (Niger, Kogi, Benue, Plateau, Nassarawa, Kwara, Federal Capital Territory); North East (Bauchi, Borno, Taraba, Adamawa, Gombe, Yobe); North West (Zamfara, Sokoto, Kaduna, Kebbi, Katsina, Kano, Jigawa); South East (Enugu, Imo, Ebonyi, Abia, Anambra); South South (Bayelsa, Akwa Ibom, Edo, Rivers, Cross River, Delta); South West (Oyo, Ekiti, Osun, Ondo, Lagos and Ogun).

Study design

Objective of the study

The main objective of this study is to advance information seeking behaviour studies by mining Web data to determine the relative use of the Web for multiple hierarchical information needs by Internet users in Nigeria. To achieve the objective of the study, the following sub-objectives were pursued.

- To compare the volume of online searches for the different hierarchical basic needs by Internet users in Nigeria.

- To compare the volume of online searches for the different hierarchical basic needs by Internet users in each geopolitical zone of Nigeria.

- To determine the pattern of search interests in the diverse hierarchical basic needs by Internet users in the states within each geopolitical zone of Nigeria.

- To profile Nigerian states based on the interests of their Internet users in searching for the five hierarchical basic needs.

To achieve the objective of the present study, the following research questions and hypotheses were examined.

Research questions

- How do the hierarchical basic needs rank in terms of their search volume among Internet users in Nigeria?

- How do the hierarchical basic needs rank in terms of their search volume among Internet users in each geopolitical zone in Nigeria?

- What is the pattern of search interests in the hierarchical basic needs among Internet users in the states within each geopolitical zone of Nigeria?

- How do Nigerian states cluster based on their Internet users' searches for the five hierarchical basic needs?

Research hypotheses

- There is no significant difference in Nigeria's Internet users' search volume for the five hierarchical basic needs.

- There is no significant difference in the search volume for each of the five hierarchical basic needs based on Nigeria's Internet users' geopolitical zones.

Literature review and theoretical framework

Information seeking

Information is an important resource needed to be able to make good decisions, to reduce uncertainty, for individual growth and for survival. The progress of modern societies as well as individuals depends a great deal upon the provision of the right kind of information, in the right form and at the right time (Yusuf, 2012). People, therefore, seek information to fill up their perceived knowledge gap in achieving a goal. According to Case (2007), information seeking was a behaviour so commonplace that it was generally not an object of concern until time pressure made it so; systematic research on information seeking dates back nearly a century (Case, 2007). This field of research has witnessed consistent development since then. In the first three decades of the twentieth century, studies of information channels and systems, chiefly libraries and the mass media, accumulated slowly. The 1940s saw the first published reviews of this literature. By the 1960s, such research, particularly into the specialised i nformation needs and uses of scientists and engineers, was appearing regularly in journals and reports (Case, 2007). While many sources of information are available, the advent of the Internet has greatly impacted people's information seeking behaviour. In the words of Alese and Owoyemi (2004, p. 171), 'This global village is a library of fun, a shopping mall, a compendium of information, a health institute of a kind, research institute, an archive, musical studio or a pornographic shop. The Internet contains all these and many more'.

The Internet: an information seeking resource

The Internet constitutes a means through which diverse information can be sought. Its pervasiveness and ease of access has also made it the most consulted information source. Many studies have been carried out on the use of the Internet for information seeking (Lee, et al., 2014; Yoon and Kim, 2014; Cho, et al., 2011; Rennis, et al., 2015; Bernarda, et al., 2012; Bjelke, et al., 2016; Jiménez-Pernett, et al., 2010; Dolce, 2011; Lima-Pereira, et al., 2012; Pollard, et al., 2015). However, while human needs are numerous and hierarchical (Maslow, 1954), most of these existing studies have considered a single information need of their subjects.

Some studies have also looked into multiple uses of the Internet by their respondents. For example, Bashir, et al., (2008) studied multiple uses of the Internet among University of the Punjab, Lahore students. They reported in decreasing order, the various uses of the Internet by their respondents. These were to prepare class assignment, to research projects, to update their knowledge, for communication, for entertainment, to prepare for examinations, to read news, to download software, for other reasons and lastly to purchase items. Seybert and Lööf (2010) also reported on how employed and unemployed people consulted the Internet for learning and for reading newspapers. While the range of needs reported in these studies might satisfy their goals and objectives, they are not broad enough to understand Internet users' information seeking for multiple hierarchical needs.

If the Internet provides a means through which users can seek information on any topic of interest, then it might be useful to examine how this platform has been used over time for information seeking on these diverse needs. Information produced by this type of study can help in profiling Internet user groups through their levels of search interest in a number of diverse needs. It might also lead to the determination of the value attached to the Web as an information source by a group of people for diverse purposes. Such a research endeavour, however, would be limited by using the survey method that had been used in most of the previous studies on Internet users' information seeking. This type of research requires that data must be available on the extent of use of the Internet for information seeking about the various needs under investigation.

A body of research developed out of a panel session at the 1997 Association for Computing Machinery Special Interest Group on Research Issues in Information Retrieval Conference was captioned 'Real life information retrieval: commercial search engines'. Studies were carried out on real life data of Web users, and interesting information on United States and European Web users' behaviour were reported (Jansen, et al., 1998; Spink, et al., 2001; Spink, et al., 2002a; Spink, et al., 2002b; Jansen, et al., 2005; Jansen and Spink, 2005; Jansen and Spink, 2006).

Jansen, et al. (1998) analysed transaction logs of a set of 51,473 queries posed by 18,113 users of the search engine, Excite. They reported that there was a lot of searching about sex on the Web, but combined that it represented a small proportion of all searches because many other subjects were searched, and the diversity of subjects searched was very high. Spink et al. (2001) studied actual Web searching by the United States population by analysing over one million Web queries by users of the Excite search engine. They reported among other findings that a small number of search terms were used with high frequency, and a great many terms were unique. Queries about recreation and entertainment ranked highest. Spink, et al. (2002a) analysed three data sets culled from more than one million queries submitted by more than 200,000 users of the Excite Web search engine, collected in September 1997, December 1999 and May 2001. Their longitudinal benchmark study showed that public Web searching was evolving in certain directions, with search topics shifting from entertainment and sex to commerce and people. Jansen, et al. (2005) examined the characteristics and changes in AltaVista Web searching that occurred from 1998 to 2002. The results of their research, among other findings, showed a broadening range of Web searchers' information needs, with the most frequent terms accounting for less than 1% of total term usage. These series of studies have been able to showcase the behaviour of United States Web users, based on the queries they submitted to these search engines. The wide range of Web searchers' queries and the move in Web interest from information on sex and entertainment topics to commerce and people were noteworthy among the findings.

Spink, et al. (2002b) compared the United States and European Internet users' behaviour by analysing data sets culled from more than one million queries submitted by more than 200,000 users of the Excite and FAST (alltheWeb.com) search engines collected in May 2001. They reported the differences between search interests of the two populations; while European Web users were searching less for e-commerce related issues and more for people and computer related issues, United States users searched primarily for commerce, travel, employment or economy and people, places or things and less on sex, pornography or preferences and entertainment or recreation. Jansen and Spink (2005) analysed Web searching by European alltheWeb.com users and also reported that European search topics were broadening, with a notable percentage decline in searches for pornography. Jansen and Spink (2006) reported results from research that examined characteristics and changes in Web searching from nine studies of five Web search engines based in the U.S. and Europe. They reported that Web searching topics were changing; there was a decrease in sexual searching as a percentage of overall Web searches on both European and U.S. based Web search engines. The overall trend was towards using the Web as a tool for information or commerce, rather than entertainment. This trend was reported to be more pronounced with U.S. compared to European searchers.

These interesting findings would not have been revealed but for the generous sharing of user queries by some United States and European search engine services. While there is much more that can be learned from Web users' behaviour in different parts of the world, the availability of and accessibility to relevant Internet users' data remain necessary prerequisites.

The Internet: a big data resource

Big data according to TechAmerica Foundation (cited by Gandomi and Haider, 2015) refers to large volumes of high velocity, complex and variable data that require advanced techniques and technologies to enable the capture, storage, distribution, management and analysis of information. Big data is not only denoted by volume, it is characterised by being generated continuously, seeking to be exhaustive and granular in scope, as well as being flexible and scalable in its production (Kitchin, 2014). While there are many sources of big data created by the availability of numerous applications and devices that collect information continuously (Bhadani and Jothimani, 2016), the rapid growth of the Web and the variety of its data types have made it the largest publicly accessible data source in the world. Web data represent a large and increasing part of everyday life which cannot be measured in any other way. They are timely and they typically involve large numbers of observations, allowing for flexible conceptua l forms and experimental settings (Askitas and Zimmermann, 2015).

This massive data store offers researchers the tantalising possibility of observing the interests of societies in real time without carrying out costly surveys (Carrière-Swallow and Labbé, 2013; Wu and Brynjolfsson, 2015). Researchers are also finding Web datasets useful to study offline social, political, and economic phenomena because search topics have been found to re?ect real issues of concern to society (Vaughan and Romero-Frías, 2014). Consequently, recently, social scientists have obtained access to huge datasets based on the Internet activity of millions of users all over the world to analyse the complex behaviour of Internet users; describing various patterns, regularities and connections to other real world phenomena (Kristoufek, 2013).

For example, many studies have analysed Google Trends Web data, a compilation of all Internet queries submitted to Google's search engine since 2004, based on geographic locations and time (Wu and Brynjolfsson, 2015) in diverse research areas such as epidemiology (Carneiro and Mylonakis, 2009; Seifter, et al., 2010; Malik, et al., 2011; Kang, et al., 2013), finance and economics (Vosen and Schmidt, 2011; Carrière-Swallow and Labbé, 2013; Choi and Varian, 2012; Kristoufek, 2013; Wu and Brynjolfsson, 2015), and Webometrics (Vaughan and Romero-Frías, 2014) among others. These studies reported positively on the usefulness of Google Trends as a source of data for elucidating useful information about human behaviour online (Opesade, 2019, 2020).

Data-driven science: an emerging science paradigm

A science paradigm constitutes an accepted way of interrogating the world and synthesising knowledge, common to a substantial proportion of researchers in a discipline, at any one moment in time (Kitchin, 2014). In the words of Gray,

The world of science has changed, and there is no question about this. Thousands of years ago, science was empirical, describing natural phenomena. In the last few hundred years, theoretical branch evolved using models and generalizations, while in the last few decades, a computational branch emerged, simulating complex phenomena. (Gray, 2007, p. xix)

Today however, witnesses the evolution of data exploration which integrates theory, experiment and computation with advanced data management and statistics (Szalay, n.d). In an international workshop on cyber infrastructure for science, it was stated that while many fields of science had depended on computational science simulations, many more were then beginning to depend on computationally intensive data analysis. A statement that succinctly expresses the relatively recent addition of big data information technology to big computing information technology in scientific research (Strawn, 2012).

Gray, based on the growing availability of big data and new analytics, proposes that science is entering a fourth paradigm. He envisages the fourth paradigm of science to be data-intensive and a radically new extension of the established scientific method (Kitchin, 2014). The techniques and technologies for such data-intensive science are so different that it is worth distinguishing data-intensive science from the existing science paradigms as a new, fourth paradigm for scientific exploration (Gray, 2007). While many of the claims being made with respect to knowledge production assert that a fundamentally different epistemology is being created and that a transition to a new paradigm is under way, the form that this new epistemology is taking is contested (Kitchin, 2014).

Kitchin (2014) presented the two diverging views on the epistemology of the emerging paradigm. Some are of the opinion that big data ushers in a new era of empiricism, wherein the volume of data, accompanied by techniques that can reveal their inherent truth, enables data to speak for themselves free of theory. They further opine that big data, new data analytics and ensemble approaches, signal a new era of knowledge production characterised by the end of theory and obsolescence of scientific method. According to them numbers can be thrown into the biggest computing clusters the world has ever seen and statistical algorithms would find patterns where science cannot. In contrast to the empiricists' view, data-driven science seeks to hold to the tenets of the scientific method but is more open to using a hybrid combination of abductive, inductive and deductive approaches to advance the understanding of a phenomenon. It differs from the traditional, experimental deductive design in that it seeks to generate hypotheses and insights born from the data rather than born from the theory. As such, the epistemological strategy adopted within data-driven science is to use guided knowledge discovery techniques to identify potential questions (hypotheses) worthy of further examination and testing. The empiricist view has gained credence outside of the academy, especially within business circles, but its ideas have also taken root in the new field of data science and other sciences. Whereas, this new mode of data-driven science is emerging within traditional disciplines in the academy (Kitchin, 2014). The present study is situated within the data-driven science approach of the emerging science paradigm.

Theoretical framework

The present study is guided by two existing theories, Maslow's theory of hierarchy of motivation and Dervin's sense-making theory. The study however, in line with the adopted approach, seeks to generate insights from Google Trends Web data rather than from the theories.

Maslow's theory of hierarchy of motivation

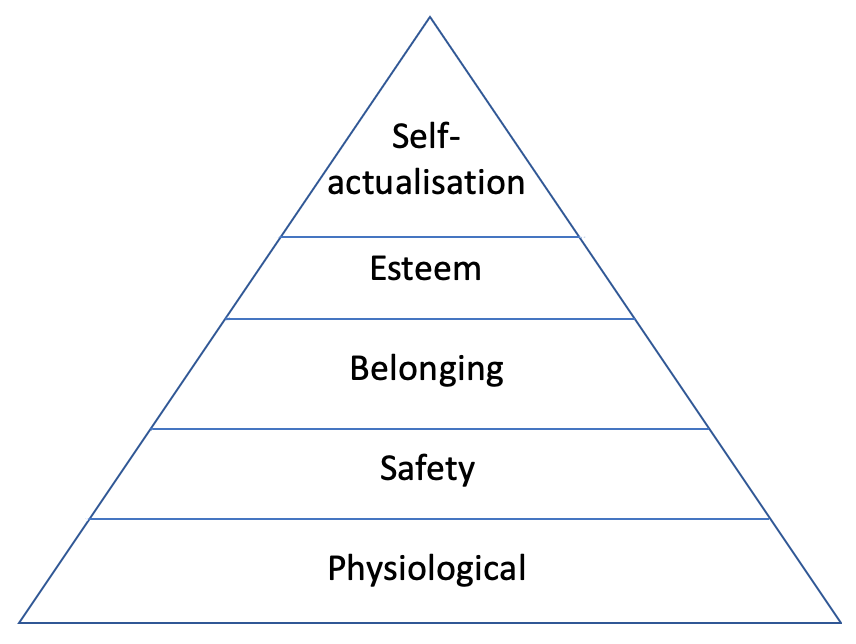

Maslow first published Motivation and personality in 1954, introducing his theory about how people satisfy various personal needs in the context of their work. He postulated, based on his observations as a humanistic psychologist, that there is a general pattern of needs recognition and satisfaction that people follow in generally the same sequence. He also theorised that a person could not recognise or pursue the next higher need in the hierarchy until her or his currently recognised need was substantially or completely satisfied, a concept called prepotency (Barnes and Pressey, 2011). Maslow classifies human striving as an attempt to fill one of five needs as shown in Figure 2.

The first need is labeled as physiological need which includes the need for air, water, and sufficient calories and nutrients to live. The second need named safety includes safety from assault, from murder and from chaos. The third need is belongingness and love, including a need for friends, a family, a community and having roots. The fourth need is esteem, where a person is valued as a wise decision-maker, with a certain status and confidence. The fifth need is self-actualisation, where each individual makes maximum use of their gifts and interests to reach whatever status they are capable of attaining (Lazim and Osman 2009; Hagerty 1999).

Although Maslow offers this as a theory of individual need fulfilment, it has been used to describe how nations develop and improve their quality of life (Hagerty, 1999). For example, Lazim and Osman (2009) proposed a new way of expressing the quality of life index using a mathematical modelling based on fuzzy sets theory and they proposed weights based on Maslow's theory of hierarchical human needs. In searching for a better solution, Clarke and Islam (2004, as cited in Lazim and Osman, 2009) used the theory of hierarchical human needs to propose weight in measuring Australia's well-being. Also whereas, Maslow's (1954) five stage model has been expanded to include cognitive and aesthetic needs and in 1970, transcendence needs (McLeod, 2007), the present study is based on the 1954 model of five hierarchical needs.

Dervin's sense-making theory

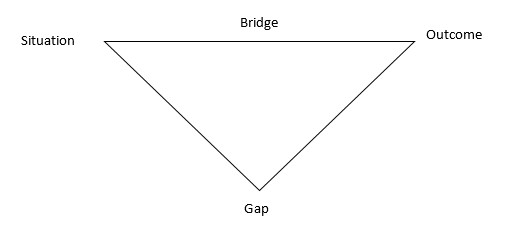

Dervin's sense-making theory is a set of assumptions, a theoretical perspective, a methodological approach, a set of research methods and a practice designed to cope with information that is perceived as a human tool and designed for making sense of a reality, which is assumed to be both chaotic and orderly (Wilson, 1999). Dervin presents these elements in terms of a triangle: situation, gap and/or bridge, and outcome (Wilson, 1999; Kundu, 2017) as shown in Figure 3.

The theory comprises four constituent elements, namely, a situation in time and space, which defines the context in which information problems arise; a gap, which identifies the difference between the contextual situation and the desired situation; an outcome; the consequences of the sense-making process; and a bridge; some means of closing the gap between situation and outcome. Sense-making's mandate has been focused primarily on the development of philosophical guidance for method, including methods of substantive theorising and of conducting research (Dervin, 1999).

The present study finds these two theories useful. Dervin's sense-making theory forms the foundation of the study which proposes that information seeking behaviour of Internet users results from the perception of their basic needs. This takes them to a situation of reality where they recognise that information is needed to fill the perceived gap and the perceived need leads to their use of the bridge (World Wide Web) to seek information to make sense of their perceived state of reality. Maslow's theory informs the perspective of diversity of human needs upheld in the present study. It also helps in determining a systematic means of identifying the multiple and hierarchical human needs used in the study. It could however, be noted that while Maslow considered satisfying personal needs in the context of employment, the present study focuses on life outside the professional environment.

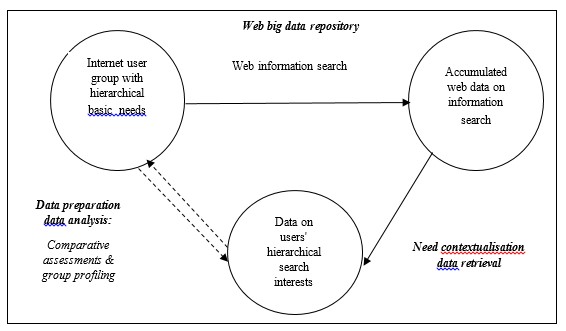

Method

The research method used in the present study is that of data-driven research. Data-driven research uses exploratory approaches to analyse big data to extract scientifically interesting insights (Kitchin, 2014). The procedure followed in this research commenced with need contextualisation in order to determine the basic search needs to be used as surrogates for the hierarchical needs. This was followed by the process of data collection (using appropriate Web data retrieval procedures), data preparation and then data analysis. Figure 4 shows the synopsis of the methodology used in carrying out the present information seeking behaviour study.

The study assumes that members of a group of information seekers have multiple information needs (with varying degrees of perception) for which they consult the Internet. These users leave digital footprints which are tracked by search engines and accumulated into a collection of Web data, as they carry out their searches. Application of appropriate data analytic techniques in mining the Web data can produce information on levels of Internet search interests for the diverse needs of the information seekers. This information can be used to discover the behaviour of the group in terms of the hierarchy of importance attached to the Internet as an information source to satisfy their basic needs. It can also be used to profile members of the group of Internet users based on their search behaviour. Presented below are the different stages involved in carrying out the present study.

Need contextualisation

This section describes the process followed in determining the multiple needs whose relative Internet search interests are to be compared. The present study contextualises the user needs within Maslow’s five hierarchical human needs; and since numerous specific human needs can fall under each hierarchy, the first stage in identifying users’ multiple, hierarchical needs is the identification of specific needs or search interests that can represent each hierarchy of targeted Internet users’ needs. This section presents the selected search interests used in this study and the rationale for their selection.

Physiological need: health-related information

Basic (or physiological) needs include air, water, sufficient calories and nutrients for life, sleep and sex. While many specific needs can be contained in this hierarchy, the present study used information related to health needs as a measure of physiological information needs. This is because unsatisfied physiological needs have been reported to cause feelings of physical pain, illness and discomfort (Maslow, 1954).

Safety needs: security-related information

Safety needs include safety from assault, from murder and from chaos. The image of lawlessness is seen everywhere through bombings, maimings and killings by disgruntled groups in Nigeria. At the moment Nigeria as a nation is being terrorised by a fanatical religious sect called Boko Haram. The Boko Haram sect believe that western education is evil and immoral. In their quest to achieve their wishes and aspirations they have resorted to acts of terrorism, bombing, maiming and killing innocent citizens in Nigeria (Nnaemeka, et al., 2015). Several other illegal armed groups, ethnic militia groups, religious fundamentalists and fanatics, are evidence of insecurity in Nigeria. These have given rise to arson, armed robberies, corruption and injustices. These happenings are negatively affecting Nigeria politically, religiously and culturally (Udoh, 2015). The present study therefore, uses searches for security-related issues to indicate interest in safety needs.

Belongingness: social media search

The third level of the needs hierarchy is belongingness which includes the human desire to belong to groups such as clubs, work groups, families or gangs. This study uses searches on social media to indicate a need for belonging. This is because social media is a means of social networking that is adopted by a large proportion of Nigerian Internet users. According to the country’s Ministry of Communications, about seventy-five per cent of Nigeria’s population that use the Internet use social media, and the number keeps growing (Amaefule, 2017). Some Nigerian Internet users basically use social media to make friends (Dada, 2018).

Esteem: English Premier League competition

Esteem can be brought about through the mastery of skills or attention and recognition from others, where a person is valued as a wise decision-maker and has a certain status and confidence. While what constitutes esteem may differ from one person to another, this study contextualises this need within Nigerian Internet users’ interest in the English Premier League. This is because of the passion that has been demonstrated over the years and the fans’ pride despite the success or failure of the teams. Figure 5a shows a crowd of football fans in Lagos watching a Premier League match while Figure 5b shows Arsenal Day in Kogi state, Nigeria which has been running for a decade.

|

|

According to Adegoke, (2017), every year for the past decade, five local government areas in Kogi state, Nigeria have come together to celebrate Arsenal Day, a two-day celebration of Arsenal football club. Thousands of fans in their red and white jerseys sing songs, dance and eat together, and enjoy a slice of Arsenal themed cake to celebrate Arsenal football club and its players. Stories of Nigeria’s English Premier League fans’ interest in the competition shows that fans derive esteem in terms of value, confidence, attention and recognition from others by the performance of their adoptive teams.

Self actualisation: Internet banking

Self-actualisation is an ongoing process. It is the need to be what one was born to be. It is the fulfilment of one’s potential. The specific form that this need will take will of course vary greatly from person to person. In one individual it may take the form of the desire to be an ideal mother, in another it may be expressed athletically, and in still another it may be expressed in painting pictures or in inventions (Maslow, 1954). The present study situates this need hierarchy within the context of Nigeria's Internet users' interest in Internet banking. Although money does not mean everything to everyone, it is assumed that being interested in Internet banking shows a level of actualisation in a country with a substantial poverty level.

Search term generation

Search term generation was carried out in February 2019, to determine the keywords to be used to collect the data on each need category from Google Trends. To achieve this task, the researcher combined their experiential knowledge of prevailing situations in Nigeria and searching some relevant sources. The sources consulted were the Website of the National Bureau of Statistics, to identify prevalent diseases in Nigeria as keywords for the physiological (health) need; the list of leading social networks in Nigeria at the 3rd quarter of 2017 was harvested from Statista.com. The Premier League table for the 2018/2019 Season was derived from Sky Sports, while the list of commercial banks was published by the Central Bank of Nigeria. The search terms for safety need category were compiled from frequent security issues in the country.

Data collection

Internet search volume on each basic need was collected from Google Trends. Volumes of Internet users’ searches for relevant terms in each category were collected between February 25 and March 2, 2019. To retrieve search volumes on these terms, each search item as it is called by Nigerians and which generated the highest number of searches were entered separately as search terms on Google Trends. For example in a preliminary search, HIV, HIV/AIDS, HIV and AIDS, and AIDS were entered in a comparative search and HIV had the highest search volume; so HIV was selected as the search term. Table 1 shows the search parameters for data collection on Google Trends.

| Need category | Selected need category | Google Trends category | Search terms on Google Trends | Search period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological | Health | Health | Polio, Cholera, Malaria, Tuberculousis, Cancer, HIV, Leprosy | 3/2/14 - 3/2/19 |

| Safety | Security | Public safety | Boko haram, Fulani herdmen, Badoo, Niger Delta Avengers | 2/27/14 - 2/27/19 |

| Belongingness | Social media | Online communities | Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp, YouTube, Snapchat, Skype, Facebook messenger, Google Plus, LinkedIn, Hangouts | 2/28/14 - 2/28/19 |

| Esteem | English Premier League | Sports | Chelsea, Arsenal, Manchester United, Manchester City, Liverpool | 2/27/14 – 2/27/19 |

| Self-actualisation | Internet banking | Banking | Access Bank, Diamond Bank plc, Ecobank, Fidelity bank, First bank, FCMB, GTB, Heritage bank, KeyStone bank, Polaris bank, Providus bank, Stanbic IBTC, Standard Chartered Bank, Sterling bank, Suntrust bank, Union bank, UBA, Unity bank, Wema bank, Zenith bank | 2/25/14 - 2/25/19 |

The need category is informed by Maslow’s theory, the selected category need refers to the context of needs of Internet users in Nigeria that represents each need category. The Google Trends category is the predefined category in Google Trends which was selected while collecting data on the search terms in each category.

Search terms are the keywords that were supplied to Google Trends sequentially as alternatives to each need category. Search terms were supplied in the English language. This is because English language is Nigeria’s official language and it is also the language that most people in Nigeria use to search on the Internet. Search period refers to the cumulative period over which Google Trends data were collected for the study (2014 to 2019) for each of the Nigerian thirty-six states and the Federal Capital Territory. Weekly data were downloaded for each state and saved as a comma-separated values file.

Data preparation

Google Trends data were prepared using Microsoft Excel 2007. The software was used to normalise search volume for search terms under each category. This was done by dividing the sum of search volume in each category by the number of search terms in that same category.

Data analyses

Microsoft Office Excel 2007 and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 17 were employed for data analyses. The former was primarily used for charting while the latter was used for determining frequency distributions and for inferential statistical analyses. SPSS was also used to cluster the thirty-six states and FCT of Nigeria based on their search interests in the basic hierarchical needs.

Results

Research Question 1: How do the hierarchical basic needs rank in terms of their search volume among Internet users in Nigeria?

The result of the mean, standard deviation and variance of the search volume for each of the five hierarchical needs in Nigeria as a whole are presented in Table 2.

| Measure | Need category | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Security | Social media | English Premier League | Online banking | |

| Mean | 28.9961 | 4.3668 | 30.6560 | 53.0108 | 20.5432 |

| Standard deviation | 15.45242 | 8.54862 | 8.69621 | 16.43174 | 15.15158 |

| Variance | 238.777 | 73.079 | 75.624 | 270.002 | 229.570 |

For the Internet users in all of Nigeria, the English Premier League had the highest number of searches, followed by social media, health, online banking and lastly security.

Research Question 2: How do the hierarchical basic needs rank in terms of their search volume among Internet users in each geopolitical zone of Nigeria? The result of the mean, standard deviation and variance of the search volume for each of the five hierarchical needs in each geopolitical zone are presented in Table 3.

| Geographical zone | Measure | Need category | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Security | Social media | English Premier League | Online banking | ||

| North Central | Mean | 31.7959 | 6.5306 | 25.6364 | 66.7143 | 21.3571 |

| Standard deviation | 9.97748 | 12.20174 | 8.29401 | 14.23463 | 6.72349 | |

| Variance | 99.550 | 148.882 | 68.791 | 202.625 | 45.205 | |

| North East | Mean | 19.6190 | 0.0000 | 26.5455 | 38.0333 | 5.0417 |

| Standard deviation | 17.62620 | 0.00000 | 10.87692 | 8.51861 | 6.42280 | |

| Variance | 310.683 | 0.000 | 118.307 | 72.567 | 41.252 | |

| North West | Mean | 14.6735 | 1.3673 | 27.6234 | 36.7143 | 11.5000 |

| Standard deviation | 19.19409 | 3.61766 | 6.07878 | 10.71128 | 17.09349 | |

| Variance | 368.413 | 13.087 | 36.952 | 114.731 | 292.188 | |

| South East | Mean | 36.8000 | 0.0000 | 30.6000 | 59.4800 | 21.3300 |

| Standard deviation | 10.06692 | 0.00000 | 6.34693 | 16.16453 | 9.25511 | |

| Variance | 101.343 | 0.000 | 40.283 | 261.292 | 85.657 | |

| South South | Mean | 36.7143 | 6.1429 | 37.3636 | 58.2000 | 29.9083 |

| Standard deviation | 5.90676 | 8.42639 | 6.85168 | 4.08705 | 14.93859 | |

| Variance | 34.890 | 71.004 | 46.945 | 16.704 | 223.161 | |

| South West | Mean | 37.5952 | 11.5714 | 37.5000 | 60.4333 | 35.6250 |

| Standard deviation | 10.30491 | 11.55961 | 6.44154 | 14.85633 | 11.51090 | |

| Variance | 106.191 | 133.624 | 41.493 | 220.711 | 132.501 | |

For the North Central zone, the English Premier League has the highest search volume followed by health, social media, online banking and lastly security. North East has the highest number of searches for the English Premier League followed by social media, health, online banking and lastly security. The North West’s highest number of searches is for the English Premier League followed by social media, health, online banking and lastly security. For South East the highest search volume is for the English Premier League, followed by health, social media, online banking and lastly security. South South’s highest number of searches is for the English Premier League followed by social media, health, online banking and lastly security. South West also has the highest search volume for the English Premier League followed by health, social media, online banking and lastly security. The mean search volume for security is zero in both the North East and South East geopolitical zones. This shows that the relative search volume is less than 1% in the two geopolitical zones.

To sum up, it could be observed from Table 3 that the English Premier League has the highest search volume across the six geopolitical zones. Search volumes for health and social media tie, as health comes second highest in the South West, South East and North Central while social media comes second highest in the South South, North West and North East. Online banking comes fourth across all zones while searches for security information are lowest across all the regions.

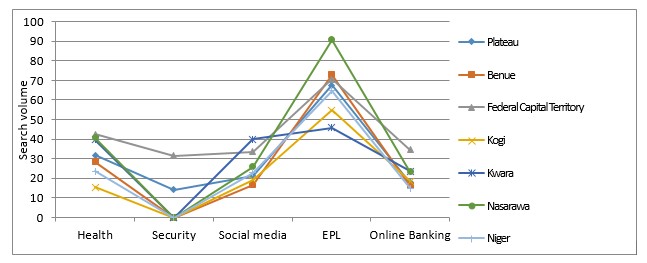

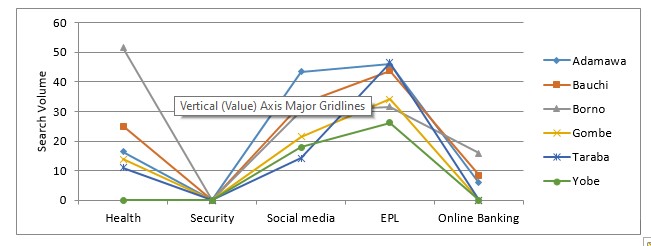

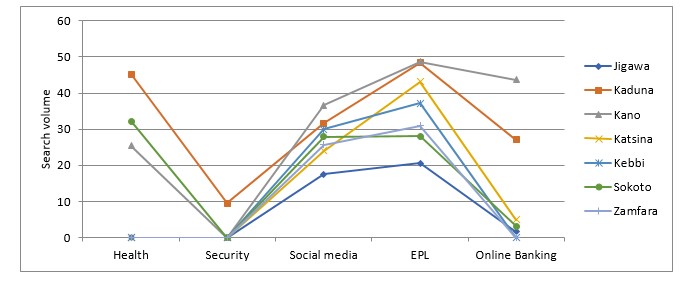

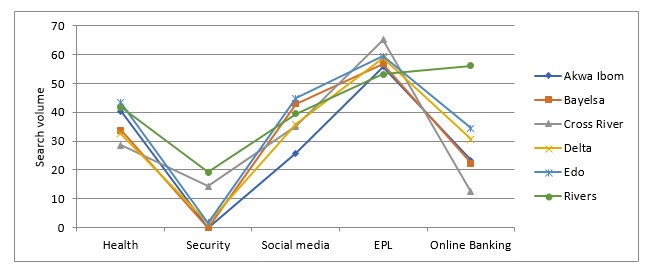

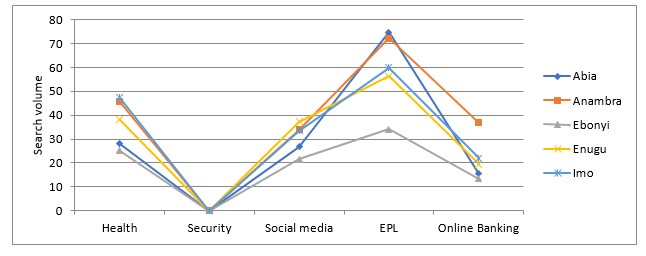

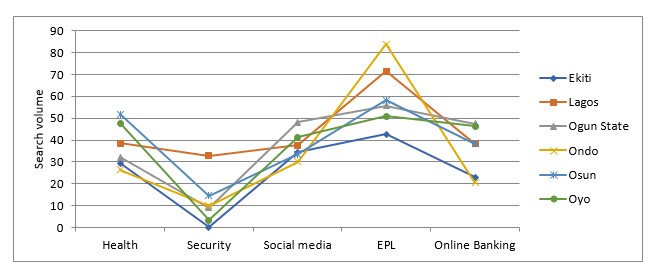

Research Question 3: What is the pattern of search interests in the hierarchical basic needs among Internet users in the states within each geopolitical zone of Nigeria? Figures 6 to 11 present the line graphs of the search volumes for each of the hierarchical needs within each of the six geopolitical zones of Nigeria.

The patterns of the number of searches carried out in each state are similar to those of the geopolitical zones and the entire country. As shown in the line graphs, search volume for the English Premier League appears to be highest while search volumes for security appear to be the lowest for most of the states within each region. It could also be observed that some states in the North Central (Federal Capital Territory and Plateau), North West (Kaduna), South South (Rivers and Cross River), and South West (Lagos) appear to be more interested in security related needs when compared to other states in their regions.

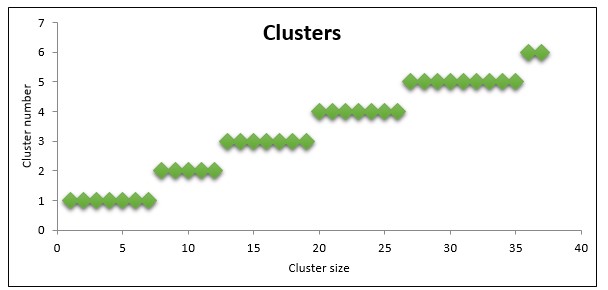

Research Question 4: How do Nigerian states cluster based on the interests of Internet users in searching for the five hierarchical basic needs? The clustering of Nigerian States based on the interests of Internet users in searching for the five hierarchical basic needs is presented in Figure 12.

Figure 12: Clusters of Nigeria’s states and Federal Capital Territory based on search pattern

In clustering the Nigerian states and the Federal Capital Territory using K-Means algorithm, the cluster number was set to six, in line with the number of geopolitical zones of the country. The resulting clusters provide information on the levels of similarities among the country's thirty-six states and the Federal Capital Territory so that locations having similar patterns in their search volumes are clustered together.

Cluster 1 comprises seven (7) states: Abia, Benue, Cross River, Nasarawa, Niger, Ondo, Plateau. Cluster 2 comprises five (5) states: Kogi, Adamawa, Bauchi, Ebonyi, Sokoto. Cluster 3 has seven (7) states: Gombe, Jigawa, Katsina, Kebbi,, Taraba, Yobe, Zamfara. Cluster 4 consists of seven (7) states> Anambra, Edo, Osun, Oyo, Kano, Ogun, Rivers. Cluster 5 contains nine (9) states: Akwa Ibom, Bayelsa, Delta, Ekiti, Enugu, Imo, Kaduna, Kwara, Borno. Finally, Cluster 6 comprises of only two locations which are Federal Capital Territory and Lagos. Cluster 4 scores the highest mean in online banking, social media and health; Cluster 1 has the highest score in English Premier League while Cluster 6 has the highest score in safety. Cluster 3 has the least value across all the five basic needs.

Tests of hypotheses

Hypothesis 1: There is no significant difference in Nigerian Internet users' search volumes for the five hierarchical basic needs. Results of the analysis of variance and post hoc tests are as shown in Table 4a and Table 4b respectively.

| Sum of squares | Degrees of freedom | Mean square | F-test | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between groups | 46122.014 | 4 | 11530.503 | 64.993 | 0.000 |

| Within groups | 31933.889 | 180 | 177.410 | ||

| Total | 78055.903 | 184 |

Table 4a shows that F= 64.993, df = 4, 180 and significance = 0.000. Since the significance is less than 0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected. Hence, there is a significant difference in Nigerian Internet users' search volumes for the five hierarchical basic needs.

| Need class | No. of States | Subset for alpha = 0.05* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Security | 37 | 4.3668 | |||

| Online banking | 37 | 20.5432 | |||

| Health | 37 | 28.9961 | |||

| Social media | 37 | 30.6560 | |||

| English Premier League | 37 | 53.0108 | |||

| Significance | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.593 | 1.000 | |

| Means for groups in homogeneous subsets are displayed * The ANOVA test of significance | |||||

Table 4b shows that the search volume for English Premier League is the highest and it is significantly different from the others. This is followed by the search volumes for social media and health which are not significantly different from each other but significantly different from all other need categories. These are followed by the search volume for online banking which is also significantly different from others and lastly by the search volume for security.

Hypothesis 2: There is no significant difference in the search volume for each of the five hierarchical basic needs based on Nigerian Internet users' geopolitical zones. Results of the analysis of variance is as shown in Table 5.

| Need factor | Measure | Sum of squares | Degrees of freedom | Mean square | F-test | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Between groups | 3124.009 | 5 | 624.802 | 3.540 | 0.012 |

| Within groups | 5471.970 | 31 | 176.515 | |||

| Total | 8595.979 | 36 | ||||

| Security | Between groups | 635.876 | 5 | 127.175 | 1.976 | 0.110 |

| Within groups | 1994.962 | 31 | 64.354 | |||

| Total | 2630.838 | 36 | ||||

| Social media | Between groups | 893.146 | 5 | 178.629 | 3.027 | 0.024 |

| Within groups | 1829.319 | 31 | 59.010 | |||

| Total | 2722.465 | 36 | ||||

| English Premier League | Between groups | 5220.864 | 5 | 1044.173 | 7.194 | 0.000 |

| Within groups | 4499.212 | 31 | 145.136 | |||

| Total | 9720.076 | 36 | ||||

| Online banking | Between groups | 3912.973 | 5 | 782.595 | 5.575 | 0.001 |

| Within groups | 4351.558 | 31 | 140.373 | |||

| Total | 8264.531 | 36 |

Table 5 shows that the level of significance is less than 0.05 for all except security; the null hypothesis is rejected for health, social media, English Premier League and online banking while the null hypothesis is accepted for security. Hence, there is a significant difference in the number of searches carried out by Nigerian Internet users for health, social media, English Premier League and online banking based on their geopolitical zones. However, there is no significant difference in the search interest for security among Internet users in Nigeria based on their geopolitical zones.

Tables 6a - 6d present the results of the Duncan post hoc tests on the results of the analysis of variance tests on health, social media, English Premier League and online banking.

| Region | No. of States | Subset for alpha = 0.05 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| North West | 7 | 14.6735 | ||

| North East | 6 | 19.6190 | 19.6190 | |

| North Central | 7 | 31.7959 | 31.7959 | |

| South South | 6 | 36.7143 | ||

| South East | 5 | 36.8000 | ||

| South West | 6 | 37.5952 | ||

| Significance | 0.521 | 0.120 | 0.495 | |

| Means for groups in homogeneous subsets are displayed Duncan test: a. Uses Harmonic Mean Sample Size = 6.087. b. The group sizes are unequal. The harmonic mean of the group sizes is used. Type I error levels are not guaranteed. | ||||

Table 6a shows that there is no significant difference between Internet users in the North West and North East of Nigeria in their search volume (being the least) for health-related terms. North Central differs significantly (higher) from the North West but not from the North East, South South, South East and South West. South South, South East and South West are significantly different (higher) from North East and North West but not from one another nor from North Central. This shows that South South, South East and South West have the highest search volume for Health, followed by North Central, North East and then North West.

| Region | N | Subset for alpha = 0.05 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ||

| North Central | 7 | 25.6364 | |

| North East | 6 | 26.5455 | |

| North West | 7 | 27.6234 | |

| South East | 5 | 30.6000 | 30.6000 |

| South South | 6 | 37.3636 | |

| South West | 6 | 37.5000 | |

| Significance | 0.313 | 0.148 | |

| Means for groups in homogeneous subsets are displayed Duncan test: a. Uses Harmonic Mean Sample Size = 6.087. b. The group sizes are unequal. The harmonic mean of the group sizes is used. Type I error levels are not guaranteed. | |||

As presented in Table 6b, there is no significant difference among Internet users in the North Central, North East, North West and South East of Nigeria in their number of searches for social media related terms. South South and South West differ significantly (higher) from North Central, North East and North West but not from South East nor from each other. This shows that South South and South West have the significantly highest search volumes for social media, followed by South East and then by North Central, North East and North West.

| Region | N | Subset for alpha = 0.05 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ||

| North West | 7 | 36.7143 | |

| North East | 6 | 38.0333 | |

| South South | 6 | 58.2000 | |

| South East | 5 | 59.4800 | |

| South West | 6 | 60.4333 | |

| North Central | 7 | 66.7143 | |

| Significance | 0.850 | 0.270 | |

| Means for groups in homogeneous subsets are displayed Duncan test: a. Uses Harmonic Mean Sample Size = 6.087. b. The group sizes are unequal. The harmonic mean of the group sizes is used. Type I error levels are not guaranteed. | |||

Table 6c shows that there is no significant difference between Internet users in the North West and North East of Nigeria in the search volume for English Premier League related terms. South South, South East, South West and North Central differ significantly (higher) from North West and North East but not from one another. Hence, South South, South East, South West and North Central have a significantly higher number of searches for the English Premier League than North West and North East.

| Region | N | Subset for alpha = 0.05 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| North East | 6 | 5.0417 | ||

| North West | 7 | 11.5000 | 11.5000 | |

| South East | 5 | 21.3300 | 21.3300 | |

| North Central | 7 | 21.3571 | 21.3571 | |

| South South | 6 | 29.9083 | ||

| South West | 6 | 35.6250 | ||

| Significance | 0.349 | 0.180 | 0.062 | |

| Means for groups in homogeneous subsets are displayed Duncan test: a. Uses Harmonic Mean Sample Size = 6.087. b. The group sizes are unequal. The harmonic mean of the group sizes is used. Type I error levels are not guaranteed. | ||||

Table 6d shows that there is no significant difference in the search volume for Internet banking related terms among Internet users in the North East and North West of Nigeria. South East and North Central differ significantly (higher) from North East but not significantly different from North West and from each other. South South and South West differ significantly (higher) from North East and North West but not from South East, North Central nor from each other. This shows that South South and South West have the highest search volume for Internet banking, these are followed by South East and North Central, followed by North West and lastly by North East.

Discussion of findings

In comparing the levels of interest in online searches for the different hierarchical basic needs in each geopolitical zone of Nigeria, the search for English Premier League ranked the highest in each of the six geographical zones and in Nigeria as a whole, while the search for security related issues ranked the lowest. Four regions namely North Central, South South, South West and South East ranked higher than that of the country’s mean search volume in their search for the English Premier League, online banking and health related terms.

South South and South West ranked higher than the mean for the entire country in their searches for social media. South South, South West and North Central ranked higher than the country mean in their searches for safety related terms. This shows that South South and South West were higher than the country mean in their Internet searches for all the five needs, North Central ranks higher than the country mean in all except social media. South East ranked higher than the country mean in three out of the five basic needs while North East and North West rank lower than the country mean in their Internet searches for each of the five basic needs. This pattern is similar to the finding in a previous study by Opesade (2020) in which these two zones (North East and North West) were found to lag behind the other four zones in their interest in searching for electronic commerce sites. This could probably be attributable to their weaker socioeconomic status as revealed in the previous study.

Despite the security challenges faced by the nation, three regions (North Central, South South, South West) scored higher than the country average. It could be observed that these three regions constitute the parts of the country that are relatively peaceful compared to those who had lower interest in searching for security matters. Could it be that those who are relatively secure search for information to get informed about the events in the troubled areas? High numbers of searches for the English Premier League across the entire country and in each geopolitical zone reinforce Nigeria’s love for this competition in particular and for football generally. This finding corroborates that of Ojo and Olanrewaju (2019) who reported that the Nigerian Football Federation had the highest number of tweets among sixty-four ministries, departments and agencies in Nigeria. According to them, this pattern clearly indicates that Nigerians are football lovers, and that they easily forget their differences once it comes to the game of football.

Results of the test of the first hypothesis establish that there are significant differences in the search interests for the five hierarchical basic needs except between the number of searches for social media and health related matters. The result also shows that the hierarchy of search interests is different from that of Maslow’s hierarchical structures. While Maslow’s hierarchy follows the order physiological, safety, belongingness, esteem and self actualisation, the search interests of Internet users in Nigeria follow the order esteem (English Premier League), physiological (health) and belongingness (social media), self- actualisation (Internet banking) and lastly safety (security matters).

The study also reveals that there are significant differences in the behaviour of Internet users in some of the six geopolitical zones in searching for health, English Premier League, social media and Internet banking information. Their search volumes for security are however, not significantly different. This suggests that most Internet users behave alike in their search habits for security matters. Since the search volume for this need is the lowest across the board, it could be that Internet users in Nigeria are not interested in searching for security information because it is not available or due to a lack of awareness of useful information on security that could help meet their information needs. This could also be because of a lack of trust in the Internet as an information source for such a need or because Internet users in Nigeria get news about security issues from print or online newspapers, so they don’t need to search the Internet for it.

Clustering of the states provides information on the searching behaviour of the states whose similarity and dissimilarity are based on their interests in searching for the five basic hierarchical needs irrespective of their geopolitical region. While cluster 4 (Anambra, Edo, Osun, Oyo, Kano, Ogun, Rivers) and cluster 6 (Federal Capital Territory, Lagos) could be referred to as heavy users of the Internet for searching for information on the five basic needs, cluster 2 (Kogi, Adamawa, Bauchi, Ebonyi, Sokoto) and Cluster 3 (Gombe, Jigawa, Katsina, Kebbi,, Taraba, Yobe, Zamfara) could be said to be light users. Cluster 1 (Abia, Benue, Cross River, Nasarawa, Niger, Ondo, Plateau) and cluster 5 (Akwa Ibom, Bayelsa, Delta, Ekiti, Enugu, Imo, Kaduna, Kwara, Borno) are in between the two extreme groups. It could be observed that while the states who are heavy users are from the southern part of the country and the Federal Capital Territory, the states who use the Internet less are all (except one, Ebonyi) from the North. This suggests the existence of a digital divide between the North and South of Nigeria. Ebonyi, a state in the South Eastern part of the country, is the only southern state among the low search cluster. This state's behaviour is similar to that found in Opesade (2020). It would be interesting to examine why Ebonyi State’s Internet searching behaviour is closer to those of the northern states of Nigeria.

Limitation of the study

This study has a potential limitation. The search terms used to interrogate Google Trends were derived from the researcher’s experiential knowledge of the prevailing situation in Nigeria and consulting some other relevant sources. These may be subject to bias as there might be some other keywords that Internet users in Nigeria are using to search the Internet. However, to minimise the effect of differences in keyword coverage that might result from this limitation, the search volumes for search terms under each category were normalised before inclusion at the data analyses stage.

Conclusions

Internet users' interests in the five basic hierarchical needs could be said to be hierarchal but not in the same order as Maslow’s ranking. The English Premier League had the highest number of searches followed by searches for social media and health matters, followed by search interest in Internet banking and finally by searches for security matters. The present study corroborates the theories that guided the study. Findings support the assertion of sense-making theory that the perceived information needs of Internet users leads to their use of the bridge (World Wide Web) to seek information to make sense of their perceived state of reality. The study also supports the hierarchy of needs as postulated by Maslow (1954). While the behaviour of Internet users in searching for security matters are the same across the six geopolitical regions of the nation, there are significant differences among some geopolitical zones in their volume of searches for the other four basic needs. There is a divide between the Northern and Southern parts of the country. The heavier Internet users who search for information on the five basic hierarchical needs in the study come from the southern part of the country while the users who search the Internet less come from the North. Federal Capital Territory, although from the North falls among the heavy users while Ebonyi, although from the South falls among the low users.

Recommendations

- Information providers should continue to publish useful information on different aspects of human basic needs on the Internet. This will provide adequate information to meet the needs of users.

- Law enforcement, relevant governmental and non-governmental agencies should create awareness of sources of useful information on security related matters that are available on the Internet. This might help to improve the volume of searches on security topics and improve use of such sources.

- Governmental and non-governmental bodies should help to put measures in place that will improve the use of the Internet in the digitally lagging states and geopolitical regions of the country.

- The Government of Ebonyi state should help in improving its citizens’ standard of using the Internet so as not to lag behind its contemporaries in the southern part of the country.

Acknowledgement

The author acknowledges the generosity of Google Inc. for making its user search index publicly and freely available through their Google Trends service. Without this benevolence, this study would not have been possible.

About the author

Adeola O.Opesade is a Lecturer at Africa Regional Centre for Information Science, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. She had her Bachelor’s degree in Electronic and Electrical Engineering (1997) from Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, followed by Masters’ degrees in Industrial and Production Engineering (2002) and Information Science (2007) both from the University of Ibadan. She obtained her Ph.D in Information Science from Africa Regional Centre for Information Science, University of Ibadan in 2013. Her areas of research interests include Web data mining, natural language processing, data-driven science, quantitative methods, and cybersecurity. She can be contacted at: ao.opesade@ui.edu.ng

References

Note: A link from the title is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Adegoke, Y. (2017, August 21). Why do Nigerians love the English premier league? CNN African Voices. https://edition.cnn.com/2017/08/19/africa/nigerians-premier-league/index.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3ii4w9b)

- Alese, B. K., & Owoyemi, S. O. (2004). Factor analytic approach to Internet usage in south–western Nigeria. Journal of Information Technology Impact, 4(3), 171-188.

- Amaefule, E. (2017, November 17). Nigeria’s online population use social media – Minister. Punch. https://punchng.com/75-of-nigerias-online-population-use-social-media-minister/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2GmPDoS)

- Askitas, N., & Zimmermann, K. F. (2015). The Internet as a data source for advancement in social sciences. Institute of Labour Economics. (IZA) (IZA Discussion Papers 8899). http://hdl.handle.net/10419/110115 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/2015-ijm-internetas-data-source-ankfz_202006)

- Ayo, C. K., Adewoye, J. O., & Oni, A. A. (2011). Business-to-consumer e-commerce in Nigeria: prospects and challenges. African Journal of Business Management, 5(13), 5109-5117. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM10.822

- Barnes, S. J., & Pressey, A. D. (2011). Who needs cyberspace? Examining drivers of needs in second life. Internet Research, 21(3), 236 - 254. https://doi.org/10.1108/10662241111139291

- Bashir, S., Mahmood, K. & Shafique, F. (2008). Internet use among university students: a survey in University of the Punjab, Lahore. Pakistan Journal of Information Management and Libraries, 9, 49-65.

- Bernarda, E., Arnoulda, M., Saint-Larya, O., Duhota, D. & Hebbrecht, G. (2012). Internet use for information seeking in clinical practice: a cross-sectional survey among French general practitioners. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 81(7), 493-499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2012.02.001

- Bhadani, A., & Jothimani, D. (2016). Big data: challenges, opportunities and realities. In M.K. Singh, & D.G. Kumar (Eds.). Effective big data management and opportunities for implementation (pp. 1-24). IGI Global. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1705.04928

- Bjelke, M., Martinsson, A., Lendahls, L. & Oscarsson, M. (2016). Using the Internet as a source of information during pregnancy - a descriptive cross-sectional study in Sweden. Midwifery, 40, 187-191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2016.06.020

- Burkell, J. A., Wolfe, D. L., Potter, P. J. & Jutai, J. W. (2006). Information needs and information sources of individuals living with spinal cord injury. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 23(4), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2006.00686.x

- Buscher, G., Cutrell, E. & Ringe, M. (2009). What do you see when you’re surfing? Using eye tracking to predict salient regions of Web pages. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems, Boston, Mass., USA, April 2009 (pp. 21-30). Association for Computing Machinery. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/1518701.1518705. https://bit.ly/3nbQARI

- Carneiro, H. A. & Mylonakis, E. (2009). Google Trends: a Web-based tool for real-time surveillance of disease outbreaks. Clinical Infectious Disease, 49(15), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1086/630200

- Carrière-Swallow, Y. & Labbé, F. (2013). Nowcasting with Google Trends in an emerging market. Journal of Forecasting, 32(4), 289-298. https://doi.org/10.1002/for.1252

- Case, D. O. (2007). Looking for information: a survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behavior (2nd. ed.). Academic Press Publications.

- Chi, E. D., Pirolli, P. L. T., Chen, K. & Pitkow, J. E. (2001). Using information scent to model user information needs and actions on the Web. In CHI '01: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seattle, Washington, USA, March 2001 (pp. 490–497). https://doi.org/10.1145/365024.365325 http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.17.7905&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Choi, H. & Varian, H. (2012). Predicting the present with Google Trends. Economic Record, 88(1), 2-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4932.2012.00809.x

- Cho, J., Noh, H., Ha, M. H., Kang, S. N., Choi, J. & Chang, Y. J. (2011). What kind of cancer information do Internet users need? Supportive Care in Cancer, 19(9), 1465–1469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-1057-9

- Dolce, M. C. (2011). The Internet as a source of health information: experiences of cancer survivors and caregivers with healthcare providers. Oncology Nursing Forum, 38(3), 353-359. https://doi.org/10.1188/11.ONF.353-359

- Dada, A. (2018, May 3). What Nigerians use social media for. PM News. https://www.pmnewsnigeria.com/2018/05/03/what-nigerians-use-social-media-for/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/what-nigerians-use-social-media-for-p.-m.-news)

- Dervin, B. (1999). On studying information seeking methodologically: the implications of connecting metatheory to method. Information Processing and Management, 35(6), 727-750. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(99)00023-0

- Facca, F. M. & Lanzi, P. L. (2005). Mining interesting knowledge from weblogs: a survey. Data and Knowledge Engineering, 53(3), 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.datak.2004.08.001

- Gandomi, A. & Haider, M. (2015). Beyond the hype: big data concepts, methods, and analytics. International Journal of Information Management, 35(2), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2014.10.007

- Gray, J. (2007). Jim Gray on eScience: a transformed scientific method. In T. Hey, S. Tansley, & K. Tolle, (Eds.). The fourth paradigm: data-intensive scientific discovery. (pp. xvii-xxxi) Microsoft Research. http://itre.cis.upenn.edu/myl/JimGrayOnE-Science.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/jim-gray-on-e-science)

- Hagerty, M. R. (1999). Testing Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: national quality-of-life across time. Social Indicators Research, 46(3), 249–271. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006921107298

- Hersberger, J. A. (2001). Everyday information needs and information sources of homeless parents. The New Review of Information Behaviour Research, 2, 119-134. https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/J_Hersberger_Everyday_2001.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3jnXdy6)

- Internet Live Stats (2014). Google search statistics. Internet Live Stats. http://www.Internetlivestats.com/google-search-statistics/# (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/34kFhhI)

- Jansen, B. J. & Spink, A. (2003). An analysis of Web documents retrieved and viewed. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Internet Computing. Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, 23-26 June, 2003 (pp. 65-69). CSREA Press. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/34MQ2ts

- Jansen, B. J. & Spink, A. (2005). An analysis of Web searching by European alltheWeb.com users. Information Processing and Management, 41(2), 361-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(03)00067-0

- Jansen, B. J. & Spink, A. (2006). How are we searching the World Wide Web? A comparison of nine search engine transaction logs. Information Processing and Management, 42(1), 248-263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2004.10.007

- Jansen, B. J., Booth, D. L. & Spink, A. (2008). Determining the informational, navigational, and transactional intent of Web queries. Information Processing and Management, 44(3), 1251–1266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2007.07.015

- Jansen, B. J., Spink, A. & Pedersen, J. (2005). A temporal comparison of AltaVista Web searching. Journal of the American Society of Information Science and Technology, 56(6), 559-570. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20145

- Jansen, B. J., Spink, A. & Saracevic, T. (2000). Real life, real users, and real needs: a study and analysis of user queries on the Web. Information Processing and Management, 36(2), 207-227. https://10.1016/S0306-4573(99)00056-4

- Jansen, B. J., Spink, A., Bateman, J. & Saracevic, T. (1998). Real life information retrieval: a study of user queries on the Web. SIGIR Forum, 32(1), 5-17. https://doi.org/10.1145/281250.281253

- Jiménez-Pernett, J., de Labry-Lima, A. O., Bermúdez-Tamayo, C., García-Gutiérrez, J. F. & Salcedo-Sánchez, M. C. (2010). Use of the Internet as a source of health information by Spanish adolescents. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 10 Article 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-10-6 (http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6947/10/6 Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3jP6UG1)

- Kang, M, Zhong, H., He, J., Rutherford, S. & Yang, F. (2013). Using Google Trends for influenza surveillance in South China. PLoS ONE, 8(1), e55205. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055205 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3nCsGyX)

- Kitchin, R. (2014). Big data, new epistemologies and paradigm shifts. Big Data and Society. 1(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951714528481

- Kristoufek, L. (2013). Can Google Trends search queries contribute to risk diversification? Scientific Reports, 3, Article no. 2713. http://www.nature.com/srep/2013/130919/srep02713/full/srep02713.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/kristoufek-2013-sci-rep)

- Kundu, D. K. (2017). Models of information seeking behaviour: a comparative study. International Journal of Library and Information Studies, 7(4), 393-405. http://www.ijlis.org/img/2017_Vol_7_Issue_4/393-405.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3jMgkC8)

- Lazim, M. A. & Osman, T. A. (2009). A new Malaysian quality of life index based on fuzzy sets and hierarchical needs. Social Indicators Research, 94(3), 499–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9445-6

- Lee, Y. J., Boden-Albala, B., Larson, E., Wilcox, A. & Bakken, S. (2014). Online health information seeking behaviors of hispanics in New York City: a community-based cross-sectional study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(7), e176. http://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3499.

- Lima-Pereira, P., Bermúdez-Tamayo, C. & Jasieńska, G. (2012). Use of the Internet as a source of health information amongst participants of antenatal classes. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21(3-4), 322-330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03910.x

- Liu, B. (2007). Web data mining: exploring hyperlinks, contents, and usage data. Springer.

- McLeod, S. A. (2007). Maslow's hierarchy of needs. Simply psychology. http://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/ct-2-paper-1)

- Malik, M. T., Gumel, A., Thompson, L. H., Strome, T. & Mahmud, S. M. (2011). "Google flu trends" and emergency department triage data predicted the 2009 pandemic h1n1 waves in Manitoba. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 102(4), 294-297. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03404053

- Maslow, A. H. (1954). A theory of human motivation. In A.H. Maslow, Motivation and personality. (pp. 39-58). Harper and Row Publishers Inc.

- Nnaemeka, C. A, Chukwuemeka, A. F. O, Tochukwu, M. O. & Chiamaka, O. J. A. (2015). Corruption and insecurity in Nigeria: a psychosocial insight. Journal of Political Sciences & Public Affairs, 3(Special issue), Article S1:003. https://doi.org/10.4172/2332-0761.S1-003 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/corruption-and-insecurity-in-nigeria-a-psychosocia)

- Ojo, A. K. & Olanrewaju, A. B. (2019). Twitter data analysis of ministries, department and agencies in Nigeria. International Journal of Scientific and Engineering Research, 10(10), 1414-1419. https://www.ijser.org/onlineResearchPaperViewer.aspx?Twitter-Data-Analysis-of-Ministries-Department-and-Agencies-in-Nigeria.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2GJeCDm)

- Opesade, A. O. (2019). Application of matrix multiplication technique to Google Trends data for mining knowledge on Nigeria’s telecommunications industry. University of Ibadan Journal of Science and Logics in ICT Research, 3(1), 1-15. https://journals.ui.edu.ng/index.php/uijslictr/article/view/74/56 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2GDvXxG)

- Opesade, A. O. (2020). Discovering patterns in electronic commerce diffusion in Nigeria using Google Trends Web data. Journal of Information Science, Systems and Technology, 4(1), 1-20. https://bit.ly/36PYOJL (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3dfQ8NX)