Talking to imagined citizens? Information sharing practices and proxies for e-participation in hyperlocal democratic settings

Peter Cruickshank, and Hazel Hall.

Introduction. Previous research in information science often uses constructs from social exchange theory to explain online information sharing. Exchange theories have a strong focus on reciprocity, yet in some communities, such as elected democratic representatives at hyperlocal level, it is observed that information is shared online for little visible return. This raises questions as to the extent to which existing models of online information sharing based on the tenets of exchange are applicable across a full range of contexts. In the case of hyperlocal representatives, this also prompts consideration of their motivations for online information sharing, and their response to apparent non-participation or lurking in this process on the part of citizens. In this paper an information sharing, practice-based approach is deployed to explore the means by which hyperlocal representatives in Scotland handle their information sharing role and address their relationship with their online lurker audiences.

Method. Hour long interviews were conducted in November and December 2016 with nineteen representatives who serve on Scottish community councils.

Analysis. Qualitative analysis of the interview data generated the results of the study.

Results. Information sharing is regarded as an important duty of community councillors. It is largely practised as transmission or broadcast (rather than exchange) using a variety of channels, both online and face-to-face. Such efforts are, however, limited. This is due to restricted resources, a lack of familiarity with the information users (and non-users) that community councillors serve, and poor knowledge of tools for analysing online audiences. Attitudes towards online communities that largely comprise lurker audiences vary from frustration to resignation.

Conclusions. While some of the findings articulate with extant knowledge and extend it further, others contradict the results of prior research, for example on online platforms as deliberative spaces. The practice-based approach as deployed in the study surfaces new contributions on proxies in information sharing. Amongst these, it adds to prior work on information seeking by proxy, and introduces the concept of information sharing by proxy.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper880

Introduction

In this article the online information sharing practices of elected democratic representatives in public fora such as Websites and social media is examined. The findings derive from a research project entitled Information Literacy for Democratic Engagement (hereafter, the Information Literacy project) completed by a research team at Edinburgh Napier University in 2017. The analysis draws on a set of data gathered in interviews with 19 Scottish community councillors. In Scotland, community councillors are the democratically elected representatives at the lowest tier of government and serve in their communities at a hyperlocal level (Hall et al., 2018a, p. 2).

Levels of information literacy amongst Scottish community councillors, and the deployment of activity theory in research design, have been examined in previous publications from Information Literacy project (Hall et al. 2018a; Hall et al., 2018b). In this article, Scottish community councillors' perceptions of their role are considered in respect of online information sharing, with a focus on one aspect of this: the accommodation of an online 'lurker' audience that, in general, demonstrates only weak engagement with the community councillors' efforts at online information sharing.

The results of the empirical study are prefaced by a literature review in which are discussed the relevance of two theories that are applied in studies of online information sharing: (1) social exchange theory; and (2) practice theory. Next follows an account of the research design and its implementation for the empirical study. The project findings are then related. These are presented in terms of the information sharing role and practices of community councillors (both online and offline), and the online interactions between community councillors and the audiences that they serve. The analysis indicates the importance of information sharing as a duty of community councillors. It also shows that online deliberation is generally avoided. Community councillors deploy a range of channels for both information seeking and dissemination on behalf of, and to, largely unresponsive audiences. Access to resources has a significant bearing on their information sharing activities, particularly in terms of skills.

Through an exploration of information sharing practices to shed light on democratic representatives' responses to lurkers, this work furnishes new perspectives on motivations for information sharing in the face of low end-user engagement. Unlike much of the earlier work in the domain of e-participation, the focus falls on representatives rather than citizens, and considers on-going practice rather than a specific intervention. The approach deployed in the study allowed for the generation of new knowledge on the role of proxies in information sharing, and the value of looking beyond social exchange theory to explain information sharing practices.

Literature review: information sharing online

Treatment of online information sharing in the e-participation literature

The theme of online information sharing in the e-participation literature draws on two decades' worth of research on the Internet's impact on the democratic process (Medaglia, 2012, p. 347). Here the discussion of online information sharing is framed around the term engagement, usually in respect of particular one-off initiatives (Edelmann, 2017, p. 45). Examples of this work include research into the use of information and communication technologies by elected representatives, such as members of parliament in the UK (Norton, 2007; Seo and Raunio, 2017), and in Norwegian municipalities (Saglie and Vabo, 2009).

More specific to the study discussed in this paper is the published research on communication channels for public consultation purposes and deliberation. For example: Kubicek (2016) compares the advantages and disadvantages of online tools for information sharing in an empirical study, concluding that these should be deployed alongside offline channels according to the resource available amongst the pool of representatives; Cullen and Sommer (2011) draw attention to the strength of social capital evident amongst community members in online (low) and offline (high) groups. Similarly, in their published work on citizen-led participation in democracy, Taylor-Smith and Smith (2018) model online 'participation spaces' (such as social media and e-mail) alongside offline equivalents (such as rooms) as sites for communication. Here attention is drawn to the influence that the effectiveness of competing channels has on their overall uptake. Other work more strongly supports the value of online fora as spaces for intense political discussion (e.g., Svensson, 2018).

Models of e-participation that derive from this stream of research are strongly influenced by the ideal of public deliberation, as established by Habermas (e.g., Matthews, 2012; Svensson, 2018). These models have been devised in response to observed low levels of engagement by citizens, often with an explicit agenda of expanding it (Medaglia, 2012). Examples include a maturity model for increasing citizen participation (Williamson, 2015) and 'ladders' of (increasing) participation (Krabina, 2016; Linders, 2012; Medaglia, 2012, p. 354).

The term lurking has been associated with these low levels of e-participation. Lurking behaviour varies. For example, lurkers may leave no traces online, or they may be seen to listen passively. In these two contexts, lurkers are citizens who have chosen to follow, but not engage with, the political process (Cruickshank et al., 2010). There is a third type of lurker, who does engage with the online community, albeit indirectly. In this latter case, active lurking occurs when individuals exert influence offline, and that later has a subsequent impact (Edelmann, 2013, pp. 645-7).

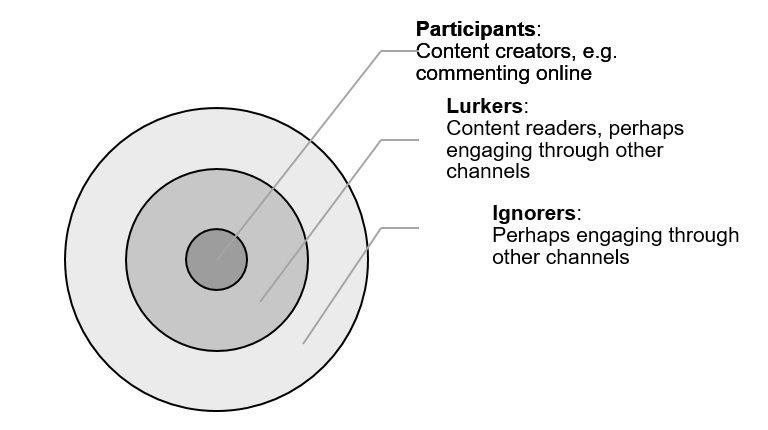

This range of modes of lurking participatory behaviour, which draws on the work of Edelmann (2017, p. 37) and Malinen (2015, p. 231), is illustrated in Figure 1. Here it can also be seen that a further set of actors is important to debates about engagement in e-participation. These are the ignorers who sit beyond the lurkers at the periphery of the online community. This group is large since it comprises the majority of citizens, i.e., those who do not directly engage with democratic processes between elections.

Explanations have been put forward to account for high degrees of lurking in online communities developed for democratic purposes. It has been established that other than on Facebook (Edelmann et al., 2011), citizens are generally wary of discussing politics online, as well as worried about the consequences of doing so. Therefore, they choose to engage off-line instead (Edelmann, 2017, pp. 37-41).

While much of the earlier research focuses on the lack of engagement on the part of citizens, it should be noted that representatives themselves have also been found to actively avoid online dialogue (e.g., Ellison and Hardy, 2014 pp. 32-33, Hall, et al, 2018a, p. 7). A practical issue in the democratic context is that a large proportion of lurkers is a practical necessity. This is because continual 100% participation would swamp most participatory processes (Edelmann, 2017, p. 48). It is also worth noting that despite the negative connotations associated with the verb to lurk, and assumptions in earlier research on online communities in the 1990s that active and visible participation is key to survival of the online community, researchers across subject domains (e.g., Cranefield et al., 2015) and some e-participation researchers (e.g., Edelmann, 2013), now generally recognise a degree of value in lurkers. However, in line with the tradition of focusing mainly on citizens in the e-participation literature (as noted by Fedotova et al., 2012, p. 155), the attitudes of elected representatives to lurkers within their communities has not yet been reported in the extant literature.

Treatment of online information sharing in the information science literature

In information science, information sharing (both online and off-line) is considered as a sub-topic of information seeking behaviour and use. Although not as well studied or developed as information seeking (Pilerot, 2012; Wilson, 2010), and without clear models, three main foci of this research may be identified. These are: (1) the information shared; (2) those who share the information; and (3) the site(s) of sharing (Pilerot, 2012, p. 574). Much of this existing research addresses information sharing as practised at work in defined communities with clear boundaries for membership, and which operate under rules (whether made explicit or unspoken) for the transition of individuals from the periphery to the core. Examples of this can be found in the knowledge management literature (e.g., Buunk et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019). Other sharing contexts have also been covered, as summarised by Pilerot (2012). These include, for example, amateur genealogy, political activism, health, and education (Pilerot, 2012, p. 563). As is the case with much information seeking behaviour and use research, it is often assumed that those who share information in online communities are doing so to meet specific information needs, e.g., recreational codebreakers (members of an online community) share hints and tips (information) with the goal of deciphering encoded messages (defined purpose) (Hall and Graham, 2004).

In terms of theoretical underpinning, the research on information sharing within these defined communities published in information science titles frequently refers to social exchange theory and/or models of social capital, often with reference to the development of communities of practice (e.g., Hall, 2003; Hall et al., 2010; Yan et al., 2016) (In the wider literature other theories are also deployed, e.g., social cognitive theory, theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behaviour, and the technology acceptance model, as noted by Chen and Hew (2015)). Here the focus falls on the benefits enjoyed by community members who willingly share their information with one another (Pilerot, 2012, p. 572). Expectations of reciprocity are high within an information or knowledge market that operates as a 'gift economy' (Hall, 2003, p. 293). The two types of exchange structures that operate in these online information sharing environments determine participant expectations of response. In direct exchanges two actors are dependent on one another. More than two actors are involved in generalised exchanges, and reciprocal dependence is indirect (Hall, 2003, p. 290). In the latter case information sharing is a collaborative activity across the whole community.

Practice theory has also been invoked to explain information sharing in online environments (for example, Pilerot, 2013). A practice theory perspective allows primarily for the consideration of the motivations and intentions that drive information behaviour. In contrast to the work that explains information sharing online as a series of transactions with reference to social exchange theory, those who adopt a practice theory approach consider information sharing as non-transactional (Pilerot, 2012, p. 563). Instead it is viewed as a situated social behaviour (Savolainen, 2008, p. 40) that affirms normalcy, and provides confidence in the self-identity in community members' roles (Savolainen, 2008, p. 55).

The work of Savolainen (2008) cited above is especially relevant to the empirical work discussed in this paper in respect of the three main motivations identified for information sharing practice (pp. 192-194). These are:

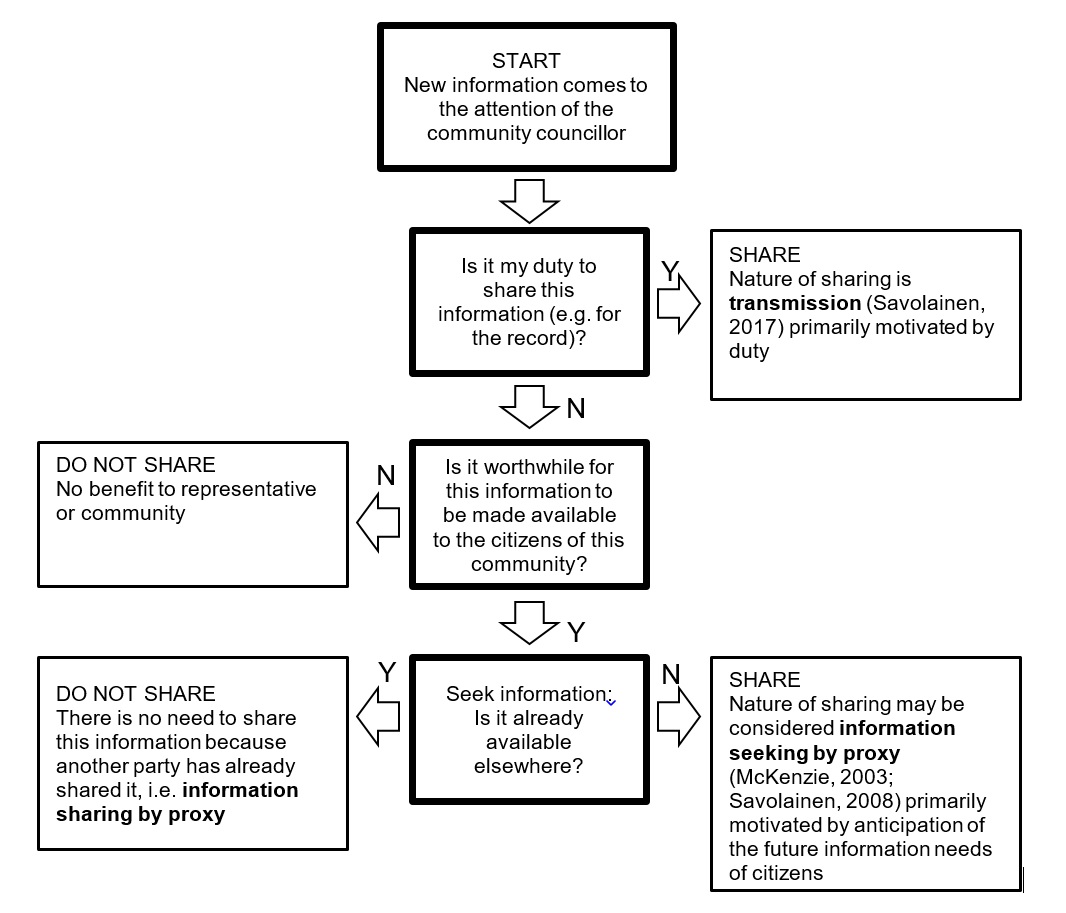

- Information seeking by proxy (as proposed by McKenzie, 2003), i.e., those who share information online are motivated to do so to help others who may not have access to the information.

- Duty, i.e., those who share information online are motivated to do so because they occupy roles such as information giver, distributor, or intermediary.

- Ritual, i.e., those who share information online are motivated to do so as part of social interactions based on regular dialogue – information sharing is considered an emotionally rewarding experience.

In a later review paper, in which he elaborates information and knowledge sharing as forms of communicative activity, Savolainen (2017) presents two different metaphors for the sharing of information, as prompted by the work of Carey (1989). The first is transmission of messages, often conceived as one-directional from giver to receiver. In the second he revisits the theme of ritual, arguing that (a) information sharing is inherently social and interpersonal, and (b) exchange, interaction, dialogue and conversation are important to the building and maintenance of communities.

As is the case in the e-participation literature, researchers in the domain of information science have turned their attention to the question of lurkers, particularly in the context of online communities (e.g., Hung et al., 2015). This is also an area of research interest in the wider literature that has strong associations with information science, for example knowledge management and information systems. For example, lurking is discussed in work which focuses on realising business benefits through communities of practice (Malinen, 2015; Takahashi et al., 2007). Often such studies promote the encouragement of 'de-lurking' by means such as the 'reader to leader' framework (Preece and Schneiderman, 2009).

It has been noted elsewhere in the information science literature by Cooke (2014) that research on lurkers does not extend to considerations of the quality of their (passive) participation. This would be worthwhile for understanding lurkers as a group, and their information needs.

Democratic engagement at hyperlocal level and information sharing online: the opportunity to make a contribution

The design of empirical study reported below allowed for an exploration of online information sharing in a community that is atypical of those normally considered in the information science literature. In this case:

- the principal sharers comprise the few (hyperlocal representatives) who attempt to engage the many (citizens)

- the many represent a heterogeneous group of citizens whose single common point of reference is simply shared geography (unlike those brought together in a community of practice, they are not bound by a common objective)

- the many have undefined information needs, of which they are unlikely to be aware.

It is worth noting here that while most previous e-participation research prioritises citizens over representatives (with a focus on the involvement of the former in democratic processes and empowerment), this study favours the latter group. Thus it was anticipated at the outset that this study would furnish an opportunity to discover more about the information practices of an under-researched group.

In particular it was expected that the approach undertaken would generate insight into actors' motivations to share information online with a seemingly unresponsive audience. This is important given the different assumptions about information sharing associated with the two perspectives introduced above, i.e., social exchange theory anticipates a transactional element to this activity, whereas practice theory does not. The application of a practice theory lens to the findings from the empirical work outlined below has allowed for the nature of the relationship between the information sharing efforts of community councillors and audience engagement to come to the fore.

Study design

The context of Scottish community councils and online information provision

Scottish community councils are conceived as representative bodies for particular geographic localities across the 32 local authorities of Scotland. There are approximately 1,100 active community councils, employing around 10,000 unpaid community councillors in total. Community councillors generally have no duties to deliver services, they cannot raise taxes, nor do they make regulations or laws. Their main role is explicitly centred on information sharing, with an emphasis on communicating local opinion to the higher tiers of local government (Hall et al, 2018a, pp. 2-3). Previous research on community council online presences, such as Websites, Twitter accounts and Facebook pages – reveals that they are characterised by low activity (see, for example Ryan and Cruickshank, 2014). Only around a quarter of community councils are active online. Even where there are high levels of primary postings, there is low or negligible secondary engagement in the form of comments or responses, nor little evidence of sustained debate conducted online. Yet despite the low levels of observed online interaction, a substantial minority of community councillors persist in sharing information online.

- Taking into account the themes identified from a preliminary literature review on the nature of lurking, and in particular prior work in the e-participation literature (specifically Cruickshank et al, 2010; Edelmann, 2013, 2017; Edelmann et al, 2011), the following questions were addressed in the study: How do community councillors perceive their information sharing role?

- How do community councillors share information?

- Which contextual factors shape the sharing of information by community councillors?

- How do community councillors conceive (or imagine) their audiences and audience levels of engagement?

This approach allowed for a range of community councillor opinion on information sharing to be sought, and it was later possible to match this to tenets of social exchange theory and practice theory. For example, there was scope for community councillors to speak about information sharing as a series of reciprocal transactions or, alternatively, as one-directional broadcasting. Similarly, they had the opportunity to point to contextual factors that promote or thwart information sharing. For example, indications in the interview responses of high reliance on face-to-face encounters with known members of the community would be relevant to a social exchange theory perspective on the basis that strong social capital supports social exchange (in general).

The findings presented below draw on the analysis of data collected in hour-long, semi-structured interviews held in November and December 2016 with nineteen community councillors resident in city, town, rural and remote rural Scottish locations. The interviewees were selected from a set of volunteers who came forward following calls for participation on an online discussion board and the national community council Website. They are profiled in Table 1.

| Years of service | Age band | Sex | Highest level of qualification (years held) | Location | SIMD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 4 | 40s | M | Masters degree (15) | Very urban | 9 |

| P2 | 5 | 50s | F | Undergraduate degree (15) | Very urban | 10 |

| P3 | 6 | 50s | M | Masters degree (30) | Very urban | 10 |

| P4 | 17 | 50s | F | Undergraduate degree (20) | Very urban | 10 |

| P5 | 3 | 60s | M | Undergraduate degree (40) | Small urban | 9 |

| P6 | 2 | 40s | M | Undergraduate degree (5) | Small urban | 6 |

| P7 | <1 | 50s | M | Masters degree (26) | Rural | 7 |

| P8 | 3 | 40s | F | Masters degree (20) | Rural | 8 |

| P9 | 3 | 50s | F | Postgraduate Diploma (26) | Very urban | 6 |

| P10 | 4 | 50s | F | Diploma (5) | Rural | 6 |

| P11 | 15 | 70+ | M | Masters degree (33) | Small urban | 7 |

| P12 | 1 | 60s | F | Masters degree (15) | Rural | 7 |

| P13 | 2 | 70+ | F | Masters degree (21) | Very rural | 6 |

| P14 | <1 | 50s | F | Undergraduate degree (20) | Small urban | 7 |

| P15 | 4 | 60s | M | Accountancy (23) | Small urban | 7 |

| P16 | 2 | 50s | F | Undergraduate degree (34) | Small urban | 8 |

| P17 | <1 | 30s | M | Higher National Diploma (10) | Small urban | 5 |

| P18 | 1 | 60s | F | Postgraduate Diploma (12) | Very urban | 10 |

| P19 | 1 | 50s | F | PhD (11) | Very urban | 10 |

In this table SIMD refers to the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD, 2016), where 10 is the most prosperous, and 1 the least. In the event this variable did not distinguish the findings derived from the analysis of data from community councillors who represent different types of community council. This is in line with previous work in this domain such as Ryan and Cruickshank (2014) and Hall et al. (2018a).

As can be seen in Table 1, a spread of community council locations is represented in the study. However, it is not possible to be certain about the representativeness of the interviewees themselves as a set of typical community councillors. This is because demographic data on the whole population of Scottish community councillors is unavailable. On the basis of the high levels of qualification held by the members of the sample and their age range, however, it is obvious that they are not representative of the Scottish population as a whole. This eventual composition of the sample for this study was not unexpected: volunteers who serve in local democratic settings tend to be the well-educated with time available to engage in community activities.

As well as profiling the community councillors, the online presences of the community councils on which they serve were audited in 2017, soon after the collection of the interview data. The summary data on the online activity and engagement of each community council as presented in Table 2 provides context for participant comment gathered at interview. Here 'S' indicates a strong online presence. A weak presence is noted as 'W' to indicate that the online content is out of date, or poorly maintained. In some cases patterns emerged in the data according to the strength or weakness of community council presence. These are highlighted where relevant in the analysis presented below.

| Participant | 1 | 2/3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11/14 | 12 | 13 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | Active |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Website | S | S | S | S | W | S | W | S | W | W | S | S | - | W | - | S | - | 9 |

| S | W | S | S | - | S | S | S | S | W | - | S | S | S | S | - | S | 12 | |

| S | S | - | - | - | W | W | S | W | - | - | - | - | W | - | - | - | 3 |

The full set of interview questions designed for the study allowed for discussion of a range of topics around the information practices of the community councillors as part of the Information Literacy project. (A full account of the development, validation and piloting of the interview questions for that project is given in Hall et al. (2018a). It should be noted that at this stage the applicability of the tenets of social exchange theory and practice theory to the specifics of the research discussed in this paper was not a consideration when the interview questions were devised.) Of most relevance to this analysis on online information sharing practices and the accommodation of a lurker audience were data gathered in response to the following five interview questions:

- How would you describe your community council's role, and your part within that?

- How do you go about finding information about local issues and developments? (What sources do you use? How did you learn about them?)

- How do you go about sharing information with your community

- How do you balance online and offline information sharing? (Have you ever chosen to share information only on paper/face-to-face? If so, why?)

- How important is an online response to your online information sharing? (Does it matter if no one responds? Who do you imagine is reading the material that you post online? How do you know who your online audience is?)

Questions 3, 4 and 5 were designed to address themes related to lurking identified in Edelmann (2013) and Cruickshank et al. (2010).

In line with common experience with semi-structured interviews, the responses to the above questions did not align directly with the research questions of the study (see for instance Evans, 2018). However, the responses gathered provided a rich data set for thematic analysis, as described below.

Data analysis

The thematic analysis of the data was achieved by a process that started with copying the responses to the interview questions into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet workbook: one row per interview question, one worksheet per interviewee. The data were then examined in three passes. First, all references to information practices and audience perceptions were identified and grouped according to literature review theme. Then the Excel TEXTJOIN concatenation function was implemented to group content by theme for all participants in a summary worksheet. The concatenated data were analysed a second time to ensure that any emergent and unanticipated themes within the data were identified. From this bottom-up analysis, five underlying themes related to practices and perceptions of information sharing emerged:

- Types of information shared

- Channels for information sharing

- Information skills/resources

- Imagining (or conceiving) the audience

- Audience interactions with information shared

Taking into account these five themes, the interview data were then re-examined a third time to validate the analysis. In this last pass it was possible to identify comments that exemplified the issues key to the study's main themes. The findings that derived from this analysis of the information sharing perceptions and practices of community councillors are detailed below, and then their implications discussed with reference to social exchange theory and practice theory.

Findings

The findings from the analysis of the empirical data are presented below according to the research questions introduced above. First the perceptions of the community councillors in respect of their information sharing role is considered. Then follows an account of their information sharing, both online and offline, and contextual factors that have an impact this activity. The third main focus of analysis is concerned with community councillors' interactions with their online audiences. Quotations and paraphrased material from individual interviewees cited in this account are indicated by the participant numbers used in Table 2.

Community councillors' perceptions of their information sharing

Information sharing is regarded by community councillors as a key duty in their roles as representatives who serve on an 'important body' (P8). A significant aspect of this work is explained as the creation of formal content for the record, such as meeting agendas and minutes (P5; P7; P12; P18), details of events (P12), planning applications (P5), or information shared by other organisations (P12). Community councillors often use the online presence(s) of the community council as a resource for residents to access local news, especially if the local newspaper is seen to be failing (P5). Alongside this formal information content, there is desire to disseminate news that will interest local residents: 'You want to put [online] something that's interesting… not the planning applications because most public aren't interested!' (P15). In some instances the community council Web pages and Twitter account are deployed to point interested residents to this archived content (P3).

The tasks associated with information sharing extend to information seeking activities, such as the monitoring of local newspapers and Websites (P17), or Facebook pages (P6; P16). For example, conversations witnessed on Facebook may later be cited a community council meetings (P7). Information for onward dissemination is also sought out through physical encounters. For example: P15 spoke about 'keeping [his] ear to the ground' and taking opportunities to 'meet people in the shop or whatever'; P5 referred to gathering comment when he passes people in the street; P8 and P18 spoke about information exchanges at other community gatherings such as at church; and P2 and P17 mentioned chance conversations with their neighbours. The digital equivalent of these interactions is the receipt of feedback by e-mail (P12). The interviewees also showed an awareness of limitations of this aspect of their information sharing role. For example: P1 drew attention to taking care with information accessed through party political contacts; P9 warned of the dangers of miscommunications that trigger negative responses from the community and cause extra work in addressing the consequences of the initial posting; and P15 spoke about disseminating content that could lead to a 'pointless argument'.

The main purpose of information sharing is to inform residents of local issues, with desired outcomes of '[making] sure that the people have as much information as possible' (P6), and 'keeping the community involved' (P18). A further driver for information sharing is to raise awareness of the work of community councils, as noted by P14. P14 believes that many citizens do not appreciate the work of community councillors and said: 'I think [community councils] should be promoting what [they're] doing to the public'. P1, who serves for one of the community councils with the strongest online presences (see Table 2), provided commentary that shows that, in some cases, this requirement for marketing has been recognised and acted upon:

We're competing for attention from people who are bombarded with all sorts of marketing messages all day long, so if I want to get to them about their opinions in a certain topic, then I have to somehow get their attention. We've got a logo, a consistent communications strategy (P1).

Although much of the interview discussion for this study focussed on the dissemination of information from the community council to citizens, the participants also drew attention to the need to voice community opinion to other parties (P14) as representatives (rather than as individuals (P7)), drawing on their knowledge of local demographics (P18).

Community councillors' information sharing practices

Community councillors share information using several channels. P6 and P8 identified the importance of deploying multiple methods of communication for reaching different groups of citizens. One of the challenges facing community councillors is identifying the most effective of these (P18), especially in the case of councils that cover large urban areas (P11). Another priority is to ensure that messages put out by community councils are not misunderstood by the population at large (P17). In addition, channel choice is also influenced by contextual factors. These issues are explored in detail below.

It is worth noting here that themes related to social exchange theory, such as reciprocal benefit, were barely mentioned in the interviews. For example, only two interviewees alluded to social capital in respect of face-to-face interactions. For this reason such themes do not feature in this account of the findings on information sharing practices.

Information sharing by community councillors online

The community councillors who contributed to this study generally prioritise online communication channels over those that are offline, as was noted explicitly by P1 and P9. Attention was drawn in the interviews to the affordances of particular online tools, especially in an era when traditional local print media are ailing or 'falling away' (P3). For example, it was argued that Facebook is more suitable for information sharing and dialogue than Twitter, conventional Websites or blogs (P5; P16; P17; P19):

'For Facebook, it's not just about information-giving, it's about getting information back' (P19).

A Facebook community council page is also valued as one of a suite of community resources:

Facebook is proving to be a very good tool for us over the last couple of years. We have our own Facebook page… there's other Facebook pages around the area. For example the village hall community association has one, and there's also an official one. (P16).

When speaking about audience interactions, it was noted by the interviewees that the information sharer is not obliged to wait passively for a response, but can rather seek out opinions by proactively garnering responses from known parties who may have an interest, in or be directly affected by, a particular issue (P8; P9). However, in a case cited by P17, it was evident that canvassing opinion when a low response rate was anticipated, and likely to be unrepresentative, was not supported by other members of his community council.

Most participants considered the main function of Websites as electronic noticeboards for the placement of announcements, and not a place for gathering community opinion. P6 went as far as to declare Websites as 'passé'. There was some reflection amongst the community councillors on the presentation of information on their own community council Websites. For example, P3 criticised his own for a structure that is 'too intricate'. Likewise P10 noted that citizens struggle to identify the location of the information that they need. P3 also disapproved of the provision of content that is not easy to read online.

The adoption of online tools by community councillors for information sharing may simply be happenstance, expressed as 'faute de mieux [for lack of something better]' by P13. At the other extreme, tool adoption results from careful planning, taking into account other community resources available online. For example, P16 explained that it is illogical to create a unique set of Web pages for a community council when there already exists a functional community Website. This point can explain the apparent 'poor' online presences of some community councils, as noted by P14, P16 and P17 in their interviews. Equally, the local media landscape is important. If an existing print or other online resource already serves the purpose of a proposed online tool, then the community council should use the existing resource as its main information channel. For example, in P15's location the local newspaper has a very high circulation ('everyone buys a copy') and it offers 'far more detail than on Facebook'. Similarly P12 made reference to mailing lists and direct mail as the route for sharing information, highlighting that to send an e-mail to the chair of the community council represents the 'real' two-way information sharing channel in hyperlocal democratic settings.

Information sharing by community councillors offline

The main traditional and official channel deployed by community councillors for information sharing is offline through community council meetings. In this face-to-face environment two-way information sharing is possible because these public meetings are open to all citizens (P19). However, the community councillors interviewed for this study noted that the members of the public who attend community council meetings tend to be unrepresentative of the local population as a whole, and are often present to promote 'their own agenda' (P18). Thus the information shared by those citizens present is regarded with a degree of scepticism, and the community councillors may choose to ignore it.

Between meetings, noticeboards can also be used for information sharing (P9). However, some of the interviewees doubted the value of noticeboards, especially when they are difficult to access (for example, because they are located inside a shop (P2)), or not regularly updated (P3).

Other physical presences provide opportunities for face-to-face information sharing with citizens, such as a stall at a local farmers' market (P8). The information gathered in such environments supplements that accessed in less formal face-to-face settings such as in the shop or street, at church, or through conversations with neighbours, as noted above.

Just two interviewees alluded to the development of social capital through face-to-face encounters with citizens (P2; P6). Social capital as a prerequisite for information sharing thus appears not to be a concern of Scottish community councillors.

Contextual factors that shape the information sharing practices of community councillors

The primary contextual factor that determines the information sharing practices of community councillors is the availability of resources. In particular, the existing skills of individual community councillors shapes the allocation of information sharing roles (P5; P6), and the channels of communication used for information sharing (P9).

In the face of a lack of specific training, when executing the information sharing role as community councillors, skills acquired in the work place or through everyday life situations are deployed (P1; P6; P16). For example, P1 explained that his community council has a clear communications strategy thanks to the skills that he has developed through work:

[In] my last job I was supply team manager for a very big consumer goods company. My job would be in multifunctional teams. I'd have marketing people next to me, finance, sales… [In] that job I became exposed to marketing methods and how to build up a following… I think that's really important for community councils (P1).

P11 also mentioned the assumption that younger community councillors have a better skills set than their older colleagues and thus are expected to take a lead in their deployment for online information sharing.

Many of the interviewees drew attention in their interviews to the lack of information sharing skills amongst community councillors at large, and highlighted that this constrains their citizen engagement work. In particular they referred to poor general IT literacy (P6; P11; P16), and a lack of knowledge of the tools that could help develop an understanding of their audiences (P2; P4; P6: P12: P18). This results in a high dependence on those who can offer the requisite skills (P9), and generates a sense of obligation on the part of certain community councillors to compensate for the lack of skills amongst others (P6).

Time is also a resource that is in short supply and may also determine the allocation of roles (P9; P12). This is regarded as wasteful in situations where the membership of the community council as a whole has a 'fabulous set of skills', but not the time to apply it (P12).

In addition to availability of resources, two further contextual factors were mentioned in the interviews as determinants of information sharing. One is the perception that information sharing is a risky activity, for example on the basis of negative prior experiences (P9; P14). The other is dominant personalities within the community council, as noted by P6.

Community councillors' interactions with their online audiences

How community councillors imagine (conceive) their online audiences

Overall, the community councillors interviewed for this study showed a weak knowledge of the consumers of the information that they share online on behalf of the Scottish community councils. They also exhibited a lack of awareness of means to address this. For example, three interviewees reported that they were unaware of the make-up of their audiences, and had no knowledge of techniques that could be used to provide this (P3; P5; P6). Similarly, two interviewees admitted that even in cases where data are available to help build a picture of the audience profile, such as counts of hits on Web pages, the conclusions drawn from these may be inaccurate (P16; P18). P11 explicitly highlighted this as a problem, and expressed the view that his community council could make a greater effort to gauge public opinion. P19 echoed this sentiment when she admitted that more could be done to assess the nature of the audiences with which the community councils interact.

This finding on low levels of knowledge of audience profile and information needs may be a reflection of the composition of the sample for this study, rather than representative of the population as a whole. For example, although P2 said that she could not provide detail at interview on hits to her community council's Website, this admission did not take into account that another (or others) in the same community council may have responsibility for the community council's online presence, and would thus have a stronger appreciation of levels of interaction that the Website enjoys with the local population. A lack of access to data may also offer some explanation here too. For example, if much of the online interaction with information shared by community councillors takes place on a platform that is not within the immediate control of the community council in question (such as a local community Website), then it may not be possible for community councillors to collect and analyse audience data.

In some cases the community councillors interviewed for this study felt that they had an intuitive understanding of those who read their online postings, and of the information needs of this audience. For example, P8 explained everyday life experiences from the time before they take up community council membership contributes to community councillors' ability to conceive the information needs of citizens. This strategy, however, is perhaps not sensible given the profile of community councillors. As P14 pointed out, although community councillors are elected as representatives of geographical areas, in practice they are not representative of the broad membership of the populations that they serve.

In other cases, it is clear that formal attempts have been made to use online tools to provide an indication of audience engagement and, through this, audience priorities. The tools available are applied with varying levels of skill. For example, basic tracking of interactions is achieved through counting comments made in response to postings on Facebook pages (P15) and Web page impressions (P7), and monitoring the derivation of such interactions (P16).

The evidence from this study also shows that those from community councils that have stronger online presences are more aware of the tools that can be deployed to understand online audiences. For example, P9 discussed the use of Facebook engagement statistics to give a better ideas of the issues of most interest to the community at large (in contrast to the low, static number of individuals who attend community council meetings in person). Similarly P1 explained that statistics can provide demographic data on the audience that has been reached. These data can then be compared with known community demographics to give a sense of the extent to which the following that the community council has garnered online (or reactions to a particular post) represent the opinion of the community as a whole (P1; P7).

Regardless of the extent to which they attempt to assess their demographic composition, information needs, and interactions of their audiences, all community councillors face a single key challenge. This is working with communities online that comprise a high proportion of ignorers and lurkers. These individuals either pay no attention whatsoever to the efforts of community councillors to fulfil their information sharing roles or – at best – listen into such communications without active participation (see Figure 1). This means that community councillors are effectively broadcasting information to 'imagined' audiences.

The analysis of the interview data shows that these imagined audiences may be characterised in a variety of different – and sometimes contradictory – ways. For example, P10 believed that ignorers are under-skilled and thus unable to access any information shared online. P2 referred to the elderly in a similar way, as did P6 and P8 (who do not expect to find older residents online at all). P9 was of the opinion that those people who do interact are the 'more public-spirited members of the community [and] people with more time on their hands', hinting at the older and retired demographic that P7 also considered well-engaged. Yet, in contrast, others imagined the online audience to be younger, digitally skilled 25-45 year-olds (e.g., P6). In one respect, however, the interviewees were in agreement: participants who actively interact with the online information shared by on community council platforms are just a few unrepresentative members of the communities in which they reside.

Community councillors' expectations of online engagement

Some interviewees made it clear that they had expectations of online dialogue with participant audiences (e.g., P6; P15; P18; P19). Responses to postings are valued because they validate the work of the community councillors:

It's quite good when you see a comment, because it's a waste of time if it doesn't happen (P15).

If people… don't contact us, it's easy to believe that no-one knows about us (P18).

For P19, feedback can be 'absolutely vital', although it need not be immediate and may be directed through a channel other than that in which the dialogue was initiated. Those from community councils with a stronger online presence were particularly keen to promote information sharing as a two-way process. For example, P7 exhibited pride when he explained that his community council's online resources show higher levels of interaction than the official council Website when controversial issues such planning applications are under consideration. In contrast, the distress of those associated with an online presence (limited to a Website only) that prompted no end user comment was evident when P12 explained that the developer was 'despondent', and then admitted 'I just don't think the community necessarily wants or needs it in the way that it was envisaged'.

Other interviewees (e.g., P8; P9; P10) indicated that they are happy to know that their online content is read, and hope (though do not necessarily expect) that it may prompt some form of response through other channels. These community councillors exhibit caution over involvement in 'public' online dialogues. To respond to a public comment with a private message is the preferred option (P10). Thus to the set of community councillors interviewed for the study, online channels are not conceived as a discussion forum, nor are they anticipated to facilitate feedback or deliberation. One of the reasons for this is the nature of the information shared such as meeting agendas or minutes, which are not intended to invite interaction (P6; P12).

Just one interviewee (P2) regarded the community councillor's online information sharing role as one that should be executed without any expectation of response. She emphasised information sharing as a form of transmission (rather than an exchange, or a means of democratic engagement, or a way to build community). To her a response is not 'hugely important'. Some other interviewees expressed a preference for one-to-one online communication methods such as private messages to respond to citizen engagement in information shared on behalf of the community council. This reduces the visibility of both information sharing and engagement. The hidden nature of these communications may be an indication of the low priority given to proactive engagement on the part of community councillors, characterised by one as 'outreach work' (P19).

Discussion

The findings reported above show that information sharing is an important duty of the community councillor role. As well as disseminating the information as required by their role (for example, meeting agendas and minutes), community councillors seek out additional information that might be of interest to members of the local communities for onward distribution. Access to resources, especially in terms of skills amongst serving community councillors, have an impact on information sharing activity.

The manner of information sharing is largely practised as transmission or broadcast using a variety of channels, both online and face-to-face. The non-transactional nature of information sharing (not conducted with an expectation of exchange), and the lack of attention to themes such as reciprocity and social capital in the interviews, indicate that it would be difficult to explain the motivations of those involved in information sharing with reference to social exchange theory.

A major drawback to their efforts at information sharing is that community councillors do not have adequate knowledge of those they serve, nor are they familiar with tools that could help them achieve this. They do, however, know that their audience comprises a majority of lurkers and ignorers. Attitudes towards these two groups amongst the community councillors are not uniform. To most, a lack of end-user responses is acceptable in recognition that an expectation of online dialogue is unrealistic. To others, there is a desire for fuller citizen engagement with the information that they share online.

The discussion below considers the key findings of the study to generate two perspectives. The first is an assessment of the extent to which the findings articulate with, extend, or contradict the extant knowledge on information sharing, e-participation, and the question of lurkers. The second revisits the findings with reference to practice theory to characterise the nature of online information sharing amongst Scottish community councillors. The limitations of the study are then presented.

Articulation of the findings of this study with extant knowledge on information sharing and e-participation

In a number of respects the findings of this study align closely with those reported in earlier work on e-participation. For example, it is evident that those who lurk in the online spaces hosted by Scottish community councils are not entirely passive. Rather these consumers of the information posted in public online fora may be prompted to take action elsewhere, for example by sending an e-mail to a community council chair, or physically attending a community council meeting. This finding fits with 'active lurking' behaviour identified by Edelmann (2013, pp. 645-7). In addition, it has been shown that the limited engagement of citizens is seen as advantageous by community councillors who fear that high response rates to online postings would require attention and use up their meagre resources. This attitude has already been noted by other e-participation researchers (Edelmann, 2017, p. 48), with specific reference to the low number of representatives, the voluntary nature of their roles, and the limited amount of channels selected for communicating with their online audiences (Kubicek, 2016).

As well as providing confirmation of findings reported in earlier studies of information sharing online for democratic purposes, the results presented here also extend previous knowledge. For example, the community councillors' reluctance to enter into dialogue with citizens in publicly accessible online spaces because they seek to avoid public controversy provides a parallel to earlier findings that citizens do the same (Edelmann, 2017, pp. 37-41). The detail in the interview data also provides explanation of the low citizen engagement with online information that has been observed in the past in this context. For example, it is clear from this study that community councillors do not expect certain types of information distributed online to prompt engagement (notably community council meeting agendas and minutes). It has also been demonstrated that when they need to do so, community councillors will proactively seek engagement offline. In these cases they are taking advantage of the hyperlocal context of their voluntary work, where opportunities for face-to-face conversations and meetings are far more frequent than in other types of community, where wide geographic dispersal of the members determines greater reliance on online tools. At the hyperlocal level these alternatives to online engagement mean that the information sharing environment is inherently multi-channel. This study furnishes additional evidence of channel switching according to channel effectiveness in specific contexts, as previously identified by Taylor-Smith and Smith (2018).

The findings on use of platform analytics by the interviewees who took part in this study also adds to extant knowledge. In prior work it has been suggested that the digital footprints left by lurkers might serve as proxy measurements of interaction (for example, Malinen, 2015, p. 232). Here examples of formal attempts to use online tools to measure audience engagement give an indication of the (limited) extent to which this is achieved in practice.

In some respects, opinions of the interviewees presented here are at odds with findings of previous work. For example, the possibility that online platforms might serve as sites for public deliberation is an ideal cited in the some of the literature reviewed above. However, amongst the community councillors interviewed for this study there is little appetite to pursue or promote this. Indeed, the findings presented here show reluctance to use public online spaces in this way. Rather, in general, community councillors consider themselves as broadcasters of information online who will respond to audience reaction but do not seek it, and they show few signs of resentment at the lack of online engagement on the part of citizens. In contrast to the communities studied by Svensson (2018), for example, there is no evidence that community councillors perceive online media as deliberative spaces where citizens may feel empowered to contribute to local debate. In fact, within these communities deliberation is closed down when possible. Thus concepts such as 'ladders' of (increasing) participation (Krabina, 2016; Linders, 2012; Medaglia, 2012, p. 354) or the idea of a maturity model to increase citizen participation (Williamson, 2015) are not relevant to this cohort.

The nature of online information sharing as practised by Scottish community councillors

By focusing on the information sharing practices of community councillors – as advocated by the practice theory approach outlined in the literature review above – the main motivations and intentions of the community councillors are surfaced in this report of the empirical work conducted for this study.

Community councillors are seen to share information primarily because this is a duty of the hyperlocal elected representative role. At the very least, community councillors understand their obligation to ensure that matters for the record reach citizens. Some also feel duty-bound to share content that they believe will interest their local communities, even if it is not crucial to community council business. This leads them to engage in a form of information seeking by proxy, achieved by anticipating (rightly or wrongly) the information needs of the citizens that they serve, and ensuring that relevant information is readily available for the time that the need for it is recognised. In online environments, the community council members who are most skilled in the use of technologies for information sharing are the main information intermediaries. Their practice forms part of the regular interactions managed by the community councils.

This overview of the information sharing practices of community councillors, derived from the analysis of empirical data, fits with the Savolainen's 2008 work, especially in respect of the motivations of (1) information seeking by proxy (elaborated from McKenzie (2003)), (2) duty and (3) ritual. In addition, the activities related to information seeking by proxy might also be conceived as a form of information sharing that leads to community building, as described by Savolainen in his more recent work (2017).

It may also be argued that sitting alongside seeking by proxy, there is evidence of information sharing by proxy as a practice of Scottish community councillors. They achieve this when they seek out and identify new information of relevance to their communities, yet deliberately refrain from sharing it when they are certain that it has already been disseminated by another intermediary. This recalls the concepts of ritual and exchange in Savolainen's 2017 work. It also hints at a form of generalised exchange (as outlined above with reference to social exchange theory), albeit that there is insufficient evidence from this study that the community councillors would recognise it as such.

The nature of information sharing by Scottish community councillors, as established in this study is summarised in Figure 2.

A further use of proxies is evident in some of the findings related to the means by which community councillors imagine their audiences. In cases where community councillors consider their own experiences and information needs as ordinary citizens, for example, they could be considered as treating themselves as proxies for the consumers of the online information that they post. Similarly, their 'imagined' audience could be based on community council meeting attendees. However, the use of community councillors (interested in hyperlocal democracy) and visibly active citizens (often with their own specific agendas) as proxies for online lurkers and ignorers is flawed. This is because these two sets of actors are unrepresentative of citizen populations.

Limitations of the study

While the analysis of interview data collected for this study has added to the understandings of information sharing and e-participation, there are a number of limitations to this study.

The main limitations are concerned with sample selection. Those who offered their opinions on the topics discussed in this paper were self-selecting individuals interested in the themes of the research as active information-sharing practitioners, and all came from the 25% of Scottish community councils that have maintained online presences. It is thus not possible to argue that their views on the study themes are representative of Scottish community councillors as a whole. In addition, only perspectives of community councillors were sought for the study. A more rounded account would have resulted from an approach that included discussions with citizens, the target audience of the community councillors' information sharing efforts.

A further limitation is that the investigation of the question of lurking was a secondary objective of a study that was primarily focused on information literacy (see Hall et al, 2018a). A focussed piece of work with lurking as its main theme would have generated additional data and a fuller analysis.

Conclusion

With reference to practice theory, this work has offered novel insight into information sharing and engagement in hyperlocal democratic settings, addressing gaps identified in the extant literature (e.g., Cooke, 2014). Unlike much of e-participation research of this nature, these themes have been considered in a context where a continuum of engagement is required, rather than with reference to a one-off initiative. In addition, the site for data collection has allowed for an investigation of online information sharing beyond the traditional setting of a community of practice where there is an expectation of reciprocity (for example, to meet objectives associated with knowledge management such as organisational learning). In doing so, it has brought into question the extent to which social exchange theory can be invoked to explain information sharing across a full range of online environments.

Here it is demonstrated that community representatives are pragmatic, resource-limited practitioners, working as volunteers within geographically-bound locations. Their priorities when information sharing using a limited variety of channels are focused on their duty to inform citizens of issues of importance to the local community, rather than on democratic engagement. They are aware that their efforts are hampered by a lack of familiarity with the end-users of the online information that they share, and poor knowledge of tools that could help them address this. They also recognise that the online communities that that they serve largely comprise lurkers and ignorers. However, their opinions of lurking and ignoring vary: to some these are important issues to be addressed; others are resigned to accept the status quo. The findings indicate that community representatives would benefit from training on tools for online information sharing (even if only to reduce the burden, and dependence on, the individual who already offer these skills), and how to use analytics and demographic data to know more about their audiences.

This analysis represents a new contribution on the role of proxies in online information sharing environments where there is low engagement. First, practical examples of information seeking by proxy, as introduced by McKenzie (2003) and elaborated by Savolainen (2008), are provided. In addition, other information-sharing-related, 'proxied' activities on the part of community representatives have been identified:

- To profile the membership of communities served, in this case with reference to expectations of community council offerings of community councillors themselves and attendees at community council meetings

- To evidence 'silent' engagement, here through the examination of digital footprints

- To information share, in this instance through confirming that relevant material identified has already been put into the public domain by other intermediaries

This adds to growing literature on the use of proxies online (such as Newlands, Lutz and Hoffman, 2018).

The research in this area could be extended in a number of ways. First, from an e-participation perspective it must be emphasised that this analysis does not consider why so few citizens engage in hyperlocal democracy online, nor question whether or not levels of low participation are important, and, if so, the means of addressing this. It would also be valuable to conduct a study similar to the one reported here at other levels of democratic representation. It is anticipated that such future work would generate a better understanding of the influence of geographic proximity on information sharing efforts, and possibly explain further opinion on the need (or not) for online engagement, as expressed by the interviewees who took part in this study. Finally, there is potential to develop the new notion of information sharing by proxy, particularly with reference to generalised forms of exchange.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Information Literacy Group of the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals for the funding of the project discussed in this paper, and the interview participants for willingly giving up their time to discuss information sharing as related to community council roles. They would also like to thank and acknowledge their Centre for Social Informatics colleague Dr Bruce Ryan for his contributions to the empirical study reported here.

About the authors

Peter Cruickshank is a Lecturer within the School of Computing at Edinburgh Napier University, United Kingdom. He has extensiveexperience in research into online participation and democratic engagement (e-participation), recently focussing on the information practice aspects, particularly around identity. He also has an active interest and delivers courses and lectures in informationsecurity and governance. He can be contacted at p.cruickshank@napier.ac.uk.

Hazel Hall is Professor of Social Informatics in the School of Computing at Edinburgh Napier University, Scotland and Docent in Information Studies at Åbo Akademi University, Finland. She holds a PhD in Computing from Napier University, an MA in Library and Information Studies from the University of Central England, and a BA (Spec Hons) in French from the University of Birmingham. Her research interests include information sharing in online environments, knowledge management, social computing, social media, online communities and collaboration, library and information science research, and research impact. She blogs at http://hazelhall.org and can be contacted at h.hall@napier.ac.uk.

References

Note: A link from the title is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Buunk, I., Smith, C.F. & Hall, H. (2018). Tacit knowledge sharing in online environments: locating 'Ba' within a platform for public sector professionals. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 51(4), 1134–1145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000618769982

- Carey, J.W. (1989). Communication as culture. Essays on media and society. Unwin Hyman.

- Chen, Y. & Hew, K.F. (2015). Knowledge sharing in virtual distributed environments: main motivators, discrepancies of findings and suggestions for future research. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 5(6), 466-571. https://doi.org/10.7763/IJIET.2015.V5.551

- Cooke, N. A. (2014). Connecting: adding an affective domain to the information intents theory. Library and Information Science Research, 36(3–4), 185–191. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2014.07.002

- Cranefield, J., Yoong, P., & Huff, S. L. (2015). Rethinking Lurking: Invisible leading and following in a knowledge transfer ecosystem. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 16(4), 213–247. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00394

- Cruickshank, P., Edelmann, N., & Smith, C. F. (2010). Signing an e-petition as a transition from lurking to participation. In J. Chappellet, O. Glassey, M. Janssen, A. Macintosh, J. Scholl, E. Tambouris, & M. Wimmer (Eds.), Electronic Government and Electronic Participation (pp. 275–282). Trauner Verlag. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-570-8-11

- Cullen, R., & Sommer, L. (2011). Participatory democracy and the value of online community networks: an exploration of online and offline communities engaged in civil society and political activity. Government Information Quarterly, 28(2), 148–154. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2010.04.008

- Edelmann, N. (2013). Reviewing the definitions of 'lurkers' and some implications for online research. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(9), 645–649. http://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0362

- Edelmann, N. (2017). Online lurking: definitions, implications, and effects on e-participation. [Doctoral dissertation, Tallinn University of Technology]. TTÜ Press. http://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.21750.70725

- Edelmann, N., Parycek, P., & Schossbock, J. (2011). The unibrennt movement: a successful case of mobilising lurkers in a public sphere. International Journal of Electronic Governance, 4(1/2), 43. http://doi.org/10.1504/IJEG.2011.041707

- Ellison, N., & Hardey, M. (2014). Social media and local government: citizenship, consumption and democracy. Local Government Studies, 40(February 2015), 21–40. http://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2013.799066

- Evans, C. (2018). Analysing semi-structured interviews using thematic analysis. Exploring voluntary civic participation among adults. Edited by J. Lewis. [Dataset]. SAGE Publications, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526439284

- Fedotova, O., Teixeira, L. & Alvelos, H. (2012). E-participation in Portugal: evaluation of government electronic platforms. Procedia Technology 5, 152-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protcy.2012.09.017

- Hall, H. (2003). Borrowed theory: applying exchange theories in information science research. Library and Information Science Research, 25(3), 287-306. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-8188(03)00031-8

- Hall, H., & Graham, D. (2004). Creation and recreation: motivating collaboration to generate knowledge capital in online communities. International Journal of Information Management, 24(3), 235-246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2004.02.004

- Hall, H., Cruickshank, P., & Ryan, B. (2018a). Practices of community representatives in exploiting information channels for citizen democratic engagement. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 51(4), 950-961 http://doi.org/10.1177/0961000618769966

- Hall, H., Cruickshank, P., & Ryan, B. M. (2018b). Exploring information literacy through the lens of activity theory. In S. Kurbanoğlu, S. Špiranec, Y. Ünal, J. Boustany, M. L. Huotari, E. Grassian, D. Mizrachi and L. Roy, (Eds.). Information Literacy in Everyday Life 6th European Conference, ECIL 2018, Oulu, Finland, September 24–27, 2018, Revised Selected Papers (pp. 803–812). Springer. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74334-9_81

- Hall, H., Widén, G., & Paterson, L. (2010). Not what you know, nor who you know, but who you know already: examining online information sharing behaviours in a blogging environment through the lens of social exchange theory. Libri, 60(2). http://doi.org/10.1515/libr.2010.011

- Hung, S.-Y., Lai, H.-M., & Chou, Y.-C. (2015). Knowledge-sharing intention in professional virtual communities: A comparison between posters and lurkers. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 66(12), 2494-2510 https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23339

- Krabina, B. (2016). The e-participation ladder – advancing from unawareness to impact participation. In P. Parycek & N. Edelmann (Eds.), CeDEM16 Proceedings of the International Conference for E-Democracy and Open Government (p. 75). Edition Donau-Universität Krems.

- Kubicek, H. (2016). What difference does the 'e' make? comparing communication channels in public consultation and collaboration processes. In G. Aichholzer, H. Kubicek, & L. Torres, (Eds.), Evaluating e-participation. Frameworks, practice, evidence (pp. 307–331). Springer International Publishing. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25403-6_15

- Linders, D. (2012). From e-government to we-government: defining a typology for citizen coproduction in the age of social media. Government Information Quarterly, 29(4), 446–454. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2012.06.003

- Malinen, S. (2015). Understanding user participation in online communities: A systematic literature review of empirical studies. Computers in Human Behavior, 46(2015), 228–238. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.004

- Matthews, P. (2012). The longue durée of community engagement. New applications of critical theory in planning research. Planning Theory, 12(2) 139-157. http://doi.org/10.1177/1473095212455212

- Medaglia, R. (2012). e-participation research: moving characterization forward (2006–2011). Government Information Quarterly, 29(3), 346–360. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2012.02.010

- McKenzie, P. (2003). A model of information practices in accounts of everyday-life information seeking. Journal of Documentation, 59(1), 19-40. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410310457993

- Newlands, G., Lutz, C. & Hoffman, C.P. (2018). Sharing by proxy: invisible users in the sharing economy. First Monday, 23(11). http://dx.doi.org/10.5210/fm.v23i11.8159

- Norton, P. (2007). Four models of political representation: British MPs and the use of ICT. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 13(3), 354–369. http://doi.org/10.1080/13572330701500771

- Panagiotopoulos, P., Bowen, F., & Brooker, P. (2017). The value of social media data: integrating crowd capabilities in evidence-based policy. Government Information Quarterly, 34(4), 601–612. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2017.10.009

- Pilerot, O. (2012). LIS research on information sharing activities – people, places, or information. Journal of Documentation, 68(4), 559–581. http://doi.org/10.1108/00220411211239110

- Pilerot, O. (2013). A practice theoretical exploration of information sharing and trust in a dispersed community of design scholars. Information Research, 18(4) paper 595. http://informationr.net/ir/18-4/paper595.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6M8gawYnD)

- Preece, J., & Schneiderman, B. (2009). The reader-to-leader framework: motivating technology-mediated social participation. AIS Transactions on Human-Computer Interaction, 1(1), 13–32. http://doi.org/10.5121/ijfcst.2014.4403

- Ryan, B. M., & Cruickshank, P. (2014). Scottish community councils online: the 2014 survey. Edinburgh Napier University. http://doi.org/10.14297/enr.2016.000002

- Saglie, J., & Vabo, S. I. (2009). Size and e-democracy: online participation in Norwegian local politics. Scandinavian Political Studies, 32(4), 382–401. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2009.00235.x

- Savolainen, R. (2008). Everyday information practices: a social phenomenological approach. Scarecrow Press.

- Savolainen, R. (2017). Information sharing and knowledge sharing as communicative activities. Information Research, 22(3), 767. http://informationr.net/ir/22-3/paper767.html (Archived by WebCite® at https://www.webcitation.org/6tTRz0IcS)

- Seo, H. S., & Raunio, T. (2017). Reaching out to the people? Assessing the relationship between parliament and citizens in Finland. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 23(4), 614–634. http://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2017.1396694

- Scotland. Government. (2016). Scottish index of multiple deprivation, 2016. https://simd.scot/2016/#/simd2016/BTTTFTT/9/-4.0000/55.9000/ (Archived by WebArchive at https://bit.ly/3dYtPwl)

- Svensson, J. (2018). Lurkers and the fantasy of persuasion in an online cultural public sphere. In J. Schwanholz, T. Graham, & P. T. Stoll (Eds.), Managing democracy in the digital age (pp. 223–241). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61708-4_12

- Takahashi, M., Fujimoto, M., & Yamasaki, N. (2007). Active lurking: enhancing the value of in-house online communities through the related practices around the online communities MIT Sloan School of Management. (Research paper no. 4646-07). http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1041261 https://bit.ly/3jsM4vk

- Taylor-Smith, E., & Smith, C. F. (2018). Investigating the online and offline contexts of day-to-day democracy as participation spaces. Information, Communication & Society, 22(13), 1–18. http://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1469656

- Wang, J., Zhang, R., Hao, J-H. & Chen, X. (2019). Motivation factors of knowledge collaboration in virtual communities of practice: a perspective from system dynamics. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(3), 466-488. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-02-2018-0061

- Williamson, A. (2015). Embedding digital advantage: a five-stage maturity model for digital communities. The Journal Of Community Informatics, 11(2). http://www.ci-journal.net/index.php/ciej/article/view/1214/1144 (Archived by WebArchive at https://bit.ly/2TrgIdK

- Wilson, T. D. (2010). Information sharing: an exploration of the literature and some propositions. Information Research, 15(4), paper 440. http://informationr.net/ir/15-4/paper440.html (Archived by WebCite® at https://www.webcitation.org/6kDegAh7n)

- Yan, Z., Wang, T., Chen, Y. & Zhang, H. (2016). Knowledge sharing in online health communities: a social exchange theory perspective. Information and Management, 53(5), 643-653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.02.001