Intention to share: the relationship between cybersecurity behaviour and sharing specific content in Facebook

Suraya Ika Tamrin, Azah Anir Norman, and Suraya Hamid.

Introduction. Sharing information on Facebook is becoming increasingly popular. Sharing text, video, voice, and pictures with unique content of the language-specific and sacred text, is becoming a trend. Consequently, issues of secure and trustable content have become increasingly important to all netizens. This issue has its foundations in the intention to share behaviour where the emphasis is on user security behaviour when sharing specific content.

Method. The proposed theory was adapted and modified from previous research to empirically evaluate survey data collected from 154 Facebook users. A snowball sampling method was used.

Analysis. A quantitative analysis was carried out on the data, which related to 154 Facebook users. This analysis used SmartPLS software.

Results. The experience of information sharing was found to be an important determinant of personal outcome expectation as it explained about 89.9 per cent of the total variance. The ability to create and share information, subjective norms, feedback, information sharing self-efficacy, personal outcome expectations, and information security behaviour have become most important factors when intending to share specific content on Facebook.

Conclusions. There is a theoretical understanding of security behaviour as a factor that promotes specific-content sharing behaviour on Facebook.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper894

Introduction

The use of social media increases as the Internet advances. Facebook has become a significant communication platform, with almost 2.38 billion active users (Kellog, 2020). It offers an attractive means to interact and communicate with each other regardless of time and geographical location. Facebook is used mainly to share, discuss, and comment on information posted by a netizen (Internet or net citizen). The proliferation of social media users results in different types of information being shared, from general information to specific areas. Since there are ‘more than 1.5 billion Muslims in the world’ (Tabrizi and Mahmud, 2013), and ‘median of 18% users out of 39 countries across the Middle East, Europe, Asia, and Africa use the Internet in their home, school or workplace’ (Liu, 2013), it is likely that the users share information that contains specific content in social networking sites.

The fundamental issue of information sharing over social media has always been whether it is secure and trusted content. When communicating through the Internet, information is easily tampered with, and changed as it can be freely shared, and there is no authoritative body required to confirm the validity of information. Furthermore, the behaviour of users while communicating via social media is important. For instance, an ethical user would have good intentions when sharing, and would confirm the validity of content shared via the Internet. However, non-ethical users will tamper with the real content with a negative purpose, resulting in too much false content shared, hence bringing harm to other netizens. A previous study reported that ‘social media become the mechanism for massive campaigns to diffuse false content’ (Zannettou et al., 2019). Another study reported that ‘false content in social media spreads more than the truth because users are more likely to spread it’ (Vosoughi et al., 2018).

It cannot be ignored that more recently social media, especially Facebook, ‘has become a constitutive part of online news dissemination and consumption of information’ (Mitchell and Page, 2014. Existing studies tend to focus on general content sharing behaviour through social media. According to Kumpel et al. (2015), ‘research on sharing content on social media should focus only on the specific kind of content’ instead of describing a general social media activity that can involve posting personal pictures, anecdotes, or directly talking about one’s feelings. Additionally, ‘false information on social media is typically re-shared by many more people, and far more rapidly, than true information, especially when there is a specific topic’ (Buchanan, 2020).

Previous researchers have attempted to develop and empirically test models to understand the reason why people want to share information (Bock et al., 2005; Kankanhalli et al., 2005; Wasko and Faraj, 2005). By using social cognitive theory, users’ intentions to share information can be determined by several factors including their expectations, social factors (subjective norms), and beliefs. To the best of our knowledge, there are few if any studies focused on the content mentioned previously. This study is one of the earliest studies that identifies the implications of information security behaviour among Facebook users in sharing specific content on social media.Using responses from 154 Facebook users, we empirically validated the implications of specific content sharing on information security behaviour. Our findings suggest that information security behaviour, information sharing self-efficacy, and subjective norms influence the intention to share specific content on Facebook. These results provide important implications for practice and further research.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows: section two presents an overview of the related issues. Section three develops the model and proposes the constructs of interest in this study and the hypotheses. Section four discusses the research method. Section five presents the results of the model testing using partial least squares, SmartPLS. Finally, section six concludes the research and identifies potential limitations and further research.

Research questions

The objective of this study is to identify the factors that promote the intention to share specific content on Facebook. The three research questions are:

RQ1: What are the factors that lead to the intention to share information on Facebook?

RQ2: How do the factors relate to sharing specific content on Facebook?

RQ3: How does cybersecurity behaviour amongst netizen relate to sharing specific content on Facebook?

Literature review

Social network sites refer to a Web-based service that enables an individual to create an open profile to gather a list of other users with whom they share interests and activities within the network range. It is used by millions of people and now seems that ‘social networking has become a pervasive part of human interaction and is changing the societal rules in the modern world at a tremendous pace’ (Saini et al., 2020).

Cyber-security behaviour in social networking sites

Since the first recognizable social network site, SixDegrees.com, launched in 1997 (Boyd and Ellison, 2007), the popularity of social networking sites has been increasing, and millions of people are now using social networking sites to communicate with their friends, perform business and many other usages according to their interests. Previous research has discussed the security issues in the cyber world, analysing the privacy and risks that harm online social networking sites. Williams et al. (2009) identified ‘the security behaviour and attitudes for social network users from different demography groups and assess[ed] how these behaviours map against privacy vulnerabilities inherent in social networking applications.’ Meanwhile, Al Hasib (2009) highlighted ‘the commercial and social benefits of safe and well-informed use of social networking Web sites.’ Al Hasib emphasised the most critical threats of the users and illustrated the fundamental factors behind those threats. Guidance and proposed technical solution have been presented to enhance privacy and security without compromising the benefits of information sharing through social networking sites.

Hashimoto et al. (2010) addressed ‘security issues, network, and security managers, which often turn to management services of network policy, such as firewall, intrusion, perfusion system, antivirus and data loss.’ They highlighted security, a framework to secure the information of organization against the threats related to social networking sites. In this study, we defined cybersecurity behaviour in more understandable terms, which is information security behaviour.

Performance accomplishments

According to Bandura (1977), ‘performance accomplishments are one’s personal mastery experience, defined as past successes or failures.’ This experience forms expectations that generalise to other situations that may be similar or substantially different from the original experience. There are two elements: information creation ability and information sharing experience.

Information creation ability

Information, can be divided into two types, implicit information and explicit information’ (Nonaka, 1994). Implicit information is challenging to interpret, because it involves soft skills and mental models. In contrast, explicit information is information that can be easily presented in the form of numbers, data and graphs. Therefore, information creation ability refers to the transformation of implicit information into explicit information. Moreover, Munro et al. (2007) found that ‘self-efficacy is positively related to user competence.’ Based on social cognitive theory and competence literature, people with a higher ability to create information may have higher confidence in sharing information.

Information sharing experience

By considering information sharing experience as a particular behaviour, ‘people can assess the potential consequences of that behaviour, as well as the potential effects on themselves and their environments’ (Bandura, 2002a; 2002b). Also, individuals can anticipate outcomes according to their behaviour. As such, ‘experience of a particular behaviour is considering an important predictor of one’s engagement in that behaviour’ (Triandis, 1980). Larose and Eastin (2004) showed that ‘users’ experience indirectly influenced the behavior on social network usage through self-efficacy’. Thus users’ experience can lead to their particular behaviour of information sharing on social networking sites.

Social persuasion

Social persuasion is one of the major elements in social cognitive theory, and encompases having others to influence one’s self efficacy and providing opportunities for mastery experience in a safe manner. Bandura (1977) stated that people were ‘led to believe they could accomplish a task or behaviour by the use of suggestion, exhortation, or self-instruction.’ However, because social persuasion is not grounded in personal experience, it is a weaker inducer of efficacy and may be extinguished by histories of past failures. There are two aspects of social persuasion (also known as verbal persuasion)Subjective norms

This suggests that ‘behaviour is instigated by one’s desire to act as important referent others (e.g., friends, family, or society in general) think one should act, or as these others actually act’ (Pookulangara and Koesler, 2011). Subject norms, which apply to the focal behaviour, reflects participant perceptions of whether the behaviour is accepted, encouraged, and implemented by the participant’s circle of influence. Bock et al. (2005) conducted a survey with thirty organisations to test a knowledge-sharing model. The results suggested that ‘subjective norm has a significant influence on knowledge sharing intention.’ One’s social environment is a valuable source of information to reduce uncertainty and determine whether behaviour is within rules and acceptable. Therefore, ‘subjective norms may, through informational and normative influences, reduce uncertainty concerning whether the use of a system is appropriate’ (Srite and Karahanna, 2006).

Feedback

Fitzsimmons et al. (1991) found that ‘good feedback increased self-confidence judgments and future self-performance.’ It is also vital for goals to have maximum effectiveness in enhancing self-confidence and improving performance. Likewise, ‘a person is relatively relying on others’ perspective, inspiration and support he receives to determine his ability’ (Bandura, 1986). Self-efficacy and outcome expectations can be determined by external feedback. Furthermore, there is a high probability for a person to enhance their ability to perform any task if supported by others.

Information sharing self-efficacy

According to Bandura (1989), ‘an individual motivation, affect and behaviour are significantly determined by perceived self-efficacy, which is defined as "a self-assessment of a person’s capacity to design things to do and then carry out the activities to achieve the goals"’ (Bandura, 1997). Bandura (1999) noted that ‘one’s perceived personal efficacy is likely to affect that individual’s selection of activities connected with the goal of eventual success.’ As such, this idea can be applied to an individual who is actively participating in social network activities. For example, a study by Larose et al. (2001) indicated that information sharing self-efficacy was a significant predictor of social network use. Furthermore, Petrie and Gunn (1998) maintained that ‘people who display social network addiction-like symptoms also tend to demonstrate low self-efficacy.’ Thus, this study intends to examine the predictability of perceived self-efficacy on social network use.

Personal outcome expectations

Bandura (1986) noted that ‘Expected outcomes have been identified as a significant predictor of one’s behaviour’. Indeed, users’ outcome expectations act as cognitively influential motivators guiding how individuals take action, such as adopting innovative communication technologies. Individuals’ expectations depend primarily on their direct or indirect experience of the behaviour being considered. ‘Expected outcomes had [been] constructed according to the six following types: novel sensory, social, status, monetary, enjoyable activity, and self-reactive incentives’ (Bandura, 1986). Similarly, individuals integrate media use, which has been partially mediated by the anticipated outcomes they aim to achieve. For example, Larose and Eastin (2004) stated that ‘expected outcomes were significantly related to social network use.’

Social network netizen

Netizen (net citizen) is a citizen who uses the Internet as a way of participating in political society (for example, exchanging views, providing information, and voting). Meanwhile, social network netizen is a social network user who is trying to contribute to the social network’s use and growth. In this study, netizen plays a significant role as a behavioural subject to determine the factors of intention to share specific content on Facebook.

Intention to share the specific content area in the social network

Bock et al. (2005) conducted a survey with thirty organisations to test a knowledge-sharing model. The results suggested that ‘attitude toward information sharing is positively and significantly influencing the behavioural intention.’ Venkatesh and Morris (2000) proposed a model presenting factors influencing household technology adoption. They concluded that ‘there is a significant relationship between attitude toward IT usage and intention to adopt technology’. Galletta et al. (2006) investigated the interacting effects of Website delay, familiarity, and breadth of users’ performance in information searching. They found ‘a positive and significant relationship between attitude and behavioural intention.’ Kolekofski and Heminger (2003) proposed a model that defines the influences of one’s intention to share information in the social network. By using the workers in a unit of a large governmental organization as samples, their study confirmed that ‘attitude influences intention to share information.’ Finally, the integrated model proposed by Wixom and Todd (2005) empirically validated ‘the strong association between attitude toward social network use and intention to share information.’

Social cognitive theory

According to Bandura (1977), ‘social cognitive theory is a widely accepted and empirically validated model of individual behavior.’ Also, social cognitive theory explains that three significant factors are affected by each other: behaviour, environmental situations, and personal factors. Additionally, Bandura (1986) defined self-efficacy as ‘people’s judgments of their capabilities to organise and execute courses of action required to attain designated types of performances’; that is, it is concerned not with the skills one has but with judgments of what one can do with whatever skills one possesses. Thus, ‘perceived self-efficacy is a crucial factor affecting motivation and behavior’ (Bandura, 1986).

Pfleeger and Caputo (2012) stated that ‘social cognitive theory asserts that some of an individual’s knowledge acquisition can directly be related to sharing behavior.’ Thus, by taking into account performance accomplishments, social persuasion, information sharing self-efficacy and personal outcome expectations, information security behaviour could increase cybersecurity awareness. This could be done by using social cognitive theory to enable Facebook users to identify a recognizable specific content to be shared and have a greater sense of information sharing self-efficacy. Facebook users would be likely to influence other Facebook users to share any specific content or information securely.

Self-efficacy

Bandura (1986) proposed that ‘there are four key sources of self-efficacy, which include performance accomplishments; vicarious experience; verbal persuasion; and psychological states.’ However, in this study, we only focused on two of the key sources, performance accomplishments and verbal persuasion (social persuasion) which will be explained in more detail in the next section. Furthermore, information sharing self-efficacy is confidence in one’s ability to share valuable information. Previous research has found that ‘people with higher levels of expertise are more likely to provide useful advice on computer networks’ (Constant et al., 1996). Additionally, an ‘individual is less likely to contribute if they feel that they lack information that is useful to others’ (Lee et al., 2006) while Kankanhalli et al. (2005) also found that ‘knowledge self-efficacy significantly affects the degree of sharing information.’ In summary, information sharing self-efficacy determines user intention to share information. Thus, we considered it as important factors in the research model.

Self-efficacy in information security behaviour

Information security behaviour can be defined as individuals information security practice involving two aspects: the adoption of security technology and security-conscious care behaviour related to computer and Internet usage’ (Rhee et al., 2009). In this study, we intend to understand the factors influencing information security behaviour when intending to share specific content on Facebook. By extending the social cognitive theory to the information security behaviour context, we contend that users’ beliefs regarding their ability to protect their information determines their behavior. Furthermore, it helps explain current security behavior and their intention to be consistent to practice such behaviour in future.

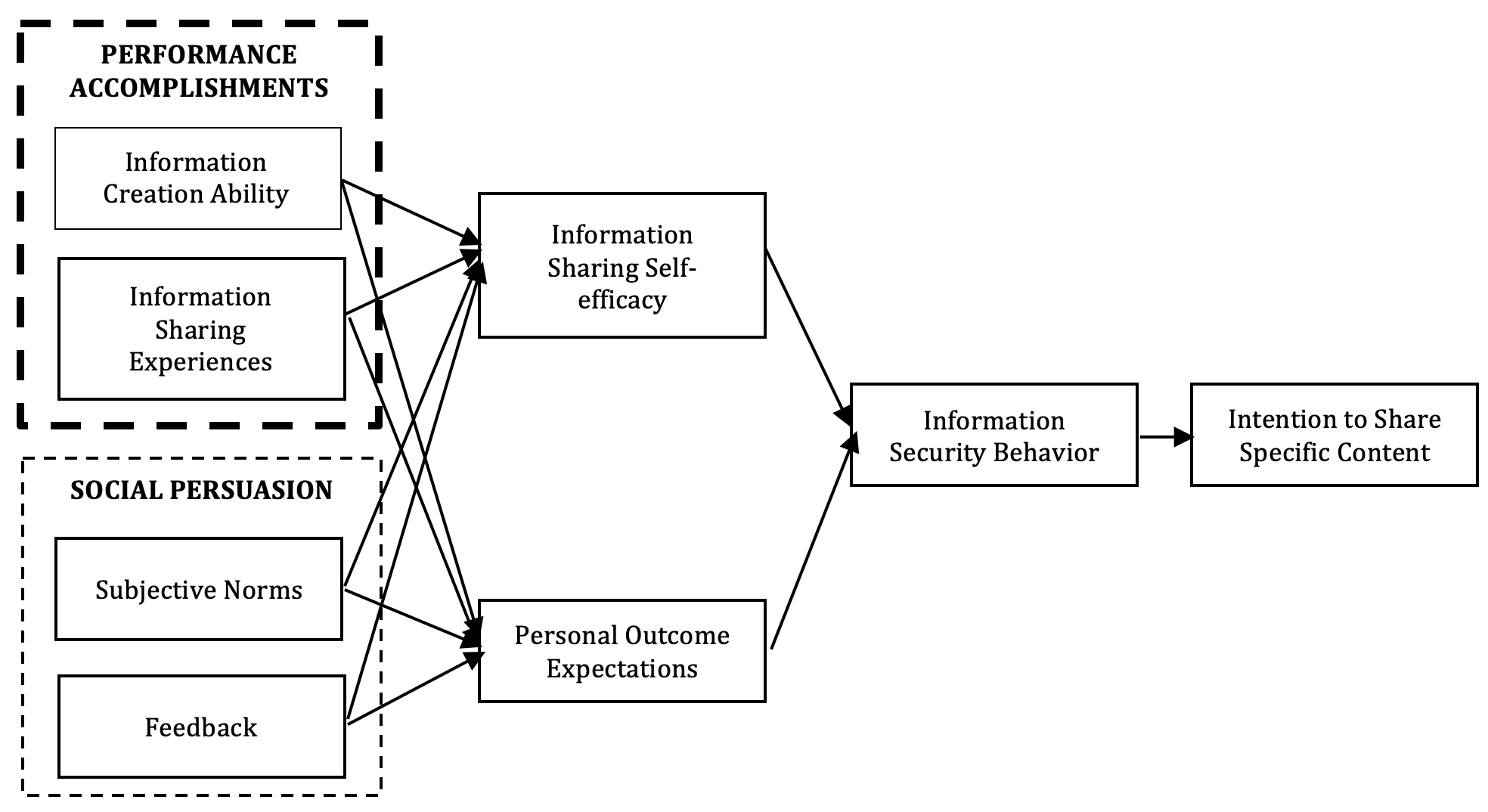

Hence, this study is adopting the social cognitive theory, and presents several crucial issues: performance accomplishments (information creation ability and information sharing experience), social persuasion (subjective norms and feedback), information sharing self-efficacy, personal outcome expectations, information security behaviour, and intention to share, using a model (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: Research framework (adapted from Lu and Hsiao, 2007)

Research framework and hypotheses

The framework shown in Figure 1 is adapted from previous research (Lu and Hsiao, 2007) based on social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986) as well as being related to information sharing and information security behaviour. From its origins in social cognitive theory, ‘self-efficacy is a person’s self-confidence in his ability to perform such security behaviour’ (Ng et al., 2009). Further, self-efficacy is an important factor that can influence a user to practice information security behaviour. On the other hand, research by Gold (2003), stated that factors such as ‘expected reward value (personal outcome expectation) have strong effects on behaviour’.

The current study investigated information security behaviour. Hence, the research model represents the element of information security behavior with two aims: 1) to investigate how information sharing self-efficacy and personal outcome expectations can influence the information security behaviour, and, 2) to investigate how behaviour is significant when considering intention to share specific content on Facebook. The proposed constructs and hypotheses that derived from the research model are all supported by previous research gathered from the literature of information systems security.

Performance accomplishments

Performance accomplishments refer to personal judgment based on an individual’s mastery experience. ‘Past successes raise efficacy assessments, while repeated failures lower overall efficacy assessments’ (Gist and Mitchell, 1992; Silver et al., 1995).

Information creation ability refers to ‘people’s judgments of their capabilities to create valuable or interesting information’ (Bandura, 1986). Additionally, he argued that ‘self-efficacy is the most affected by performance accomplishment.’ Thus, to assess a person’s performance accomplishments, information creation ability is needed as it can affect information sharing self-efficacy. Based on social cognitive theory, people who have more ability to create information may have confidence in sharing the information. Therefore, we hypothesise that:

H1. Information creation ability has a significant relationship with information sharing self-efficacy.

H2. Information creation ability has a significant relationship with personal outcome expectations.

Information sharing experience is defined as the experience of sharing valuable or interesting information with others via the Internet. It can also be shared in other media, such as books, pictures and e-mail. The Internet facilitates the mass usage of electronic media. When an individual makes judgments, information sharing of experience becomes a possible source of judging performance accomplishments. ‘Prior experience had been found to have a powerful effect on self-efficacy estimations’ (Wood and Bandura, 1989) and many studies suggest that prior experience would affect self-efficacy (Johnson, 2005; Potosky, 2002). Hence, information sharing experience may influence information sharing self-efficacy. Thus, we hypothesise that:

H3. Information sharing experience has a significant relationship with information sharing self-efficacy.

H4. Information sharing experience has a significant relationship with personal outcome expectations.

Social persuasion

Social persuasion refers to activities where people are talked into believing that they will deal with specific tasks successfully. For instance, coaching, counseling, and feedback on performance are general types of social persuasion.

Subjective norms is defined by Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) as ‘the degree to which an individual believes the people who are important to him/her expect him/her to perform the behaviour in question’. Compeau et al., (1999) also argue that encouragement, which is one form of outcome expectation, ‘can be influenced by subjective norms, of others who are important to people’. If others encourage the sharing of knowledge, the individual’s assessment of the likely outcome of their behaviour will be affected. Thus, we hypothesise that:

H5. Subjective norm has a significant relationship with personal outcome expectations.

H6. Subjective norm has a significant relationship with information sharing self-efficacy.

Feedback is defined as advice, criticism, or information about the quality or usefulness of something or somebody’s work. ‘Feedback had known to not only lead to the achievement of performance goals but also lead to a higher sense of competence’ (Barr and Conlon, 1994). As noted in self-efficacy literature (Igbaris and Iivari, 1995), individuals partly rely on the opinion of others as well as the encouragement and support they receive to judge their ability. External feedback may determine self-efficacy and outcome expectations. Moreover, people are also likely to increase their abilities to perform a task if assistance is readily available. Consequently, we hypothesise that:

H7. Feedback has a significant relationship with personal outcome expectations.

H8. Feedback has a significant relationship with information sharing self-efficacy.

Information sharing self-efficacy

This study describes the ‘confidence in one’s ability to share interesting or useful information with others’ (Constant et al., 1996). People gain confidence in sharing information and raise self-efficacy when they share useful information with others. This belief can be viewed as a self-motivational force for Facebook users to share valuable information. ‘If people feel that they cannot contribute useful information to others, they may be less willing to share information’ (Lee et al., 2006). Additionally, Bandura (1977) argued, ‘individuals can believe that a particular course of action will produce certain outcomes,’ but if individuals entertain severe doubts about whether they can perform the necessary activities, such information does not influence their behaviour. This statement indicates that the users’ cognition of a situation has a high impact on the outcomes of action. If individuals believe they have essential skills or information, they are more likely to expect positive results. Hence, we hypothesise that:

H9. Information sharing self-efficacy has a significant relationship with information security behaviour.

Personal outcome expectations

Compeau et al. (1999) stated that ‘personal outcome expectations refer to expectations of rewards or change in image’. Based on social cognitive theory, people are more likely to engage in a behaviour if they expect to reward. Additionally, ‘people will continue to share information on the Internet if they expect praise or rewards’ (Lee et al., 2006). Hence, we hypothesise that:

H10. Personal outcome expectation has a significant relationship with information security behaviour

Information security behaviour

Mattord and Whitman (2012) defined information security as ‘the protection of information and the systems and hardware that use, store, and transmit that information’. Meanwhile, information security behaviour is defined as ‘individual’s willingness to take security precaution to protect information’ (Rantonen, 2014). In the context of this study, focusing on sharing specific content on Facebook, the practitioners and others have stressed that it is vital to secure the governance that entails Facebook users. Hence, this information security behaviour will lead to an intention to share specific content on Facebook in a secure manner. Prior research has suggested that ‘the habit (a form of behaviour) had a direct effect on intentions to use IT’ (Vance et al, 2012). In this study, we focus on the relationship between information security behaviour and intention to share. Hence, we hypothesise that:

H11. Information security behaviour has a significant relationship with the intention to share

Table 1 outlines the details of the research questions and hypotheses, as discussed above.

| Research questions | Hypotheses |

|---|---|

| RQ1: What are the factors that lead to the intention to share information on Facebook? | No hypotheses (results are determined by the loading of each factor). |

| RQ2: How do the factors relate to sharing specific content on Facebook? | H1: Information creation ability has a significant relationship with information sharing self-efficacy. H2: Information creation ability has a significant relationship with personal outcome expectations. H3: Information sharing experience has a significant relationship with information sharing self-efficacy. H4: Information sharing experience has a significant relationship with personal outcome expectations. H5: Subjective norms have a significant relationship with personal outcome expectations. H6: Subjective norms have a significant relationship with information sharing self-efficacy. H7: Feedback has a significant relationship with personal outcome expectations. H8: Feedback has a significant relationship with information sharing self-efficacy. |

| RQ3: How does cybersecurity behaviour amongst netizen relate to sharing specific content on Facebook? | H9: Information sharing self-efficacy has a significant relationship with information security behaviour. H10: Personal outcome expectations have a significant relationship with information security behaviour. H11: Information security behaviour has a significant relationship with the intention to share. |

Research methodology

Sampling and data collection

The target population consisted of Facebook users, and the unit of analysis was a user who intended to share specific content on Facebook including content sharing that contains sacred texts of faith and belief. The reason for focusing on Facebook as a subject in this study was because it is the biggest and fastest-growing social network system. In fact, ‘Facebook is currently the dominant and most-trusted social network system with almost 2.38 billion active users’ (Kellog, 2020). Thus, it is reasonable to suggest that Facebook is the favourite platform for users to disseminate information, including specific content. Further, a snowball sampling method was applied to in two steps:

- Identify potential participants in the population.

- Ask those participants to recruit other people (and then ask those people to recruit. Participants should be made aware that they do not have to provide any other names).

Measurement instrument

A questionnaire was developed made up of thirty-four self-reported items related to eight research constructs and in dual-language, Malay (official language in Malaysia) and English, to ensure all the participants were able to understand the questions. All the items selected for the constructs were adapted from prior research to ensure content validity and reliability. The questionnaire items used a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. All the adapted scale items were slightly modified to fit the requirements of this study. Table 2 shows a summary of the items used.

On the questionnaire, users could self-report their confidence level of sharing the specific content, the ability to share the specific content, the experience of specific content sharing, the expectations and feedback from friends and people they know regarding specific content sharing in Facebook, and their self-expectations towards specific content sharing on Facebook.

| Items | Code | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Information creation ability (Lu and Hsiao, 2007) | ICA1 | I am able to create some valuable or interesting specific-based information. |

| ICA2 | I am good at creating some valuable or interesting specific-based information. | |

| ICA3 | I often create some valuable or interesting specific-based information. | |

| Information sharing experience (Staples et al., 1999) | ISE1 | I have much experience in sharing valuable or interesting specific information with others via Facebook |

| ISE2 | I usually share valuable or interesting specific information with others via Facebook. | |

| Subjective norms (Venkatesh and Morris, 2000) | SN1 | My Facebook friends expect me to share specific information on my Facebook. |

| SN2 | People who I contact expect me to share specific information on my Facebook | |

| Feedback (Lu and Hsiao, 2007) | FeB1 | I get some feedback (advice or criticism) about specific information I shared on my Facebook from my friends. |

| FeB2 | I get some feedback (advice or criticism) about specific information I shared from the people who I contact. | |

| Information sharing self-efficacy (Kankanhalli et al., 2005) | ISS1 | I have confidence in my ability to share specific information on Facebook that can solve others’ problem or is entertaining. |

| ISS2 | I have confidence in my ability to share specific information on Facebook, which others are interested in or consider useful. | |

| ISS3 | I am confident that the most specific information which I share can attract others’ attention | |

| Personal outcome expectations (Compeau and Higgins, 1999) | POE1 | If I share specific information on my Facebook, I will improve my image within others. |

| POE2 | If I share specific information on my Facebook, I will improve others’ recognition of me. | |

| POE3 | If I share specific information on my Facebook, I will be given praise from others. | |

| Information security behaviour (Rai, 2011) | ISB1 | I have ever read the security policy before joining Facebook. |

| ISB2 | I regularly review Facebook’s security settings. | |

| ISB3 | I monitor my Facebook profile. | |

| ISB4 | I am careful about the shared specific information I posted on my Facebook. | |

| ISB5 | I am careful about who I friend. | |

| ISB6 | I am careful about what groups I join. | |

| ISB7 | I control my security settings so that only my friends can see the specific information I share. | |

| ISB8 | I control my security settings so that what I share on Facebook regarding specific information does not show up on my news feed. | |

| ISB9 | I am concerned about the security of the specific information that's shared on Facebook. | |

| ISB10 | Facebook did a good job of protecting my information security. | |

| ISB11 | It is very important to me that I am aware of and knowledgeable about how my specific information will be used when I share it online. | |

| ISB12 | I am not aware of how Facebook may use the specific information I share on my profile. | |

| ISB13 | In the past, others have posted specific information that I wish had not posted. | |

| ISB14 | In the past, people have seen specific information on my Facebook profile that I regret I posted. | |

| ISB15 | I wouldn't mind if Facebook allowed advertisers to use my specific information, I shared on my profile to send me ads about things I might be interested in. | |

| Intention to share (Davis, 1989; Moon and Kim, 2001) | IS1 | I intend to share this specific information on my Facebook from now on. |

| IS2 | I predict I would share this specific information on my Facebook continuously. | |

| IS3 | I plan to share this specific information on my Facebook in the future. | |

| IS4 | I will recommend others to share specific information on their Facebook. |

Results

Descriptive statistics

The sample was disseminated without any selection of male and female respondents. As a result, within 154 respondents, the majority (81.8 percent) were female, with the remaining 18.2 per cent being male. As of December 2017, Malaysia has around 22 million active Facebook users, of which 45 per cent are male, 51 per cent female and 4 per cent unstated (Statista, 2017). Thus, female Facebook users are more numerous than male.

In terms of education level, 41.6 percent of the respondents indicated that they have a Bachelor’s Degree. Furthermore, the results showed that 82.5 percent of the respondents in the age range between 18 and 25 years old. According to Ismail et al, (2019), in Malayisa, statistically showed that ‘the young adults in the age range between 18 and 25 years old are the main contributors with 34.5 percent of Facebook users’. There was no respondent in the range 55 and older. As stated above, this study applied a snowball sampling method in distributing the survey. This may impact the result where the young group in the range of 18 to 25 circulated the survey among their networking group.The results indicate that 48.1 per cent of the respondents logged on to or accessed Facebook several times a day. Detailed descriptive statistics data relating to the respondents, including the percentages are shown in Table 3.

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 28 | 18.2 | 81.8 |

| Female | 126 | 81.8 | 100 | |

| Education | PMR* | 2 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| SPM** | 7 | 4.5 | 5.8 | |

| STPM†, Diploma or Certificate | 42 | 27..3 | 33.1 | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 64 | 41.6 | 74.7 | |

| Master’s Degree | 33 | 21.4 | 96.1 | |

| Doctoral Degree | 4 | 2.6 | 98.7 | |

| Professional Degree | 2 | 1.3 | 100 | |

| Age | 17 or under | 3 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| 18 – 25 | 127 | 82.5 | 84.4 | |

| 26 – 34 | 20 | 13.0 | 97.4 | |

| 35 – 44 | 3 | 1.9 | 99.3 | |

| 45 – 54 | 1 | 0.7 | 100 | |

| 55 or older | 0 | 0.0 | 100 | |

| Facebook use in a given week | Less than once a week | 5 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| At least once a week | 0 | 0 | 3.2 | |

| Three to four times a week | 13 | 8.4 | 11.6 | |

| At least once per day | 48 | 31.2 | 42.8 | |

| Several times a day | 74 | 48.1 | 90.9 | |

| All-day long | 14 | 9.1 | 100 | |

| * Penilaian Menengah Rendah - a former public examination; **Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia (Malaysian Certificate of Education); † Sijil Tinggi Persekolahan Malaysia (Malaysian Higher School Certificate) | ||||

Data analysis

To conduct the proposed model and test the hypotheses, we used structural equation modelling, partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM), SmartPLS in identifying the relationship of variables on specific information sharing behaviour. A SmartPLS approach allows researchers to calculate and analyse various parameters, which include item loading, reliability, and validity tests and structural path coefficients simultaneously of social cognitive theory in this study. ‘PLS-SEM is frequently used by many researchers today and is claimed to be a powerful method to analyses research data’ (Ali et al., 2016). It is shown to be suitable to use in the analysis of abnormally distributed data. Correspondingly, the validating procedure involved is called confirmatory factor analysis. ‘This validation method has been widely used in previous studies’ (Bulut and Dogan, 2017).

Additionally, SmartPLS makes minimal demands in terms of a sample size to validate a model compared to structural equation modelling. In our model, because all items are viewed as effects, not causes, of latent variables, they are modeled as reflective indicators. According to Chin (1998), the sample size of PLS requires ten times the largest number of independent variables impacting a dependent variable or the largest number of formative indicators. Therefore, our sample size of 154 is more than sufficient for the PLS estimation procedures. We modeled all latent constructs as reflective indicators. To sum up, the measurement model demonstrated factor validity, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity, as presented in Table 4.

In this study, the specific targets are Facebook users who mainly use Facebook to share specific content such as verses, videos, and so on. Therefore, this study used the 154 responses to test the research model.

| Validity type | Criterion | Description analysis | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor validity | Outer loadings and cross loadings | In the PLS analysis, the significance of each item or variable is measured by using the outer loading and cross-loadings in the reflective measurement model. The variables with outer loading 0.7 or higher are considered highly satisfactory (Henseler et al., 2009; Gotz et al., 2010). While loading value of 0.5 is regarded as acceptable, the manifest variables with loading value of less than 0.5 should be dropped (Chin, 1998; Hair et al., 2010). | Table 6 shows that all of the variables/items are greater than acceptable value 0.5. Hence, the results demonstrate that the items were considered highly satisfactory (greater than 0.7), except for ICA3 and ISB10. |

| Internal consistency reliability | Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability | Internal consistency reliability is constructed reliability where it is evaluated by two measures, that is, Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability, which indicate how well a set of variables appraises a single latent construct. However, compared to Cronbach alpha, composite reliability is considered a better measure of internal consistency because it employs the standardised loadings of the variables (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Nonetheless, the interpretation of the composite reliability score and Cronbach's alpha is similar. According to Litwin (1995), the value of Cronbach's alpha should be higher than 0.7 and for composite reliability the value of 0.7 is suggested as modest (Hair et al., 2011; Nunally, 1978). | As shown in Table 6, our Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.705 to 0.888, exceeding the threshold of 0.7. Meanwhile, for composite reliability, the constructs are considered reliable because the value of is more than 0.8, as presented in Table 6. |

| Convergence validity | Average variance extracted. | In the partial least squares analysis, each latent variable’s average variance extracted criterion by Fornell and Larcker (1981) is evaluated to check convergent validity. Furthermore, convergent validity is confirmed when the average variance extracted values are greater than the acceptable threshold of 5.0 (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988) | From Table 6, it is found that all of the average variance extracted values are within the range between 0.714 and 0.899 (greater than 0.5), whereby all items had sufficient convergent validity. |

| Discriminant validity | Fornell-Larcker criterion | Fornell and Larcker (1981) suggested that the square root of AVE in each latent of the variable can be used to establish discriminant validity. The AVE reading of each latent variable is higher compared to the latent variable’s highest squared correlation than other latent elements (Urbach and Ahlemann, 2010) | Table 5 indicates that discriminant validity for all items is well established and the latent variable has good values. |

| FeB | ICA | IS | ISB | ISE | ISS | POE | SN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feedback | 0.892 | |||||||

| Information creation ability | 0.494 | 0.845 | ||||||

| Intention to share | 0.398 | 0.531 | 0.863 | |||||

| Information security behaviour | 0.153 | 0.287 | 0.716 | 0.848 | ||||

| Information sharing experience | 0.480 | 0.686 | 0.595 | 0.264 | 0.948 | |||

| Information sharing self-efficacy | 0.403 | 0.564 | 0.801 | 0.677 | 0.589 | 0.895 | ||

| Personal outcome expectations | 0.570 | 0.410 | 0.381 | 0.104 | 0.323 | 0.386 | 0.892 | |

| Subjective norms | 0.700 | 0.607 | 0.517 | 0.200 | 0.677 | 0.470 | 0.566 | 0.878 |

| Construct | Items | Loading | Cronbach’s alpha | Composite reliability | Average variance extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feedback | FeB1 | 0.914 | 0.747 | 0.887 | 0.796 |

| FeB2 | 0.870 | ||||

| Ability | ICA1 | 0.928 | 0.798 | 0.879 | 0.714 |

| ICA2 | 0.946 | ||||

| ICA3 | 0.621 | ||||

| Share | IS1 | 0.927 | 0.886 | 0.921 | 0.745 |

| IS2 | 0.823 | ||||

| IS3 | 0.912 | ||||

| IS4 | 0.782 | ||||

| Behaviour | ISB10 | 0.654 | 0.865 | 0.910 | 0.719 |

| ISB7 | 0.915 | ||||

| ISB8 | 0.908 | ||||

| ISB9 | 0.888 | ||||

| Experience | ISE1 | 0.950 | 0.888 | 0.947 | 0.899 |

| ISE2 | 0.946 | ||||

| Self-efficacy | ISS1 | 0.937 | 0.872 | 0.923 | 0.800 |

| ISS2 | 0.948 | ||||

| ISS3 | 0.791 | ||||

| Expectations | POE1 | 0.918 | 0.873 | 0.921 | 0.796 |

| POE2 | 0.865 | ||||

| POE3 | 0.891 | ||||

| Norms | SN1 | 0.901 | 0.705 | 0.871 | 0.771 |

| SN2 | 0.854 | ||||

| Note: ISB1, ISB2, ISB3, ISB4, ISB5, ISB6, ISB11, ISB12, ISB13, ISB14, and ISB15 were deleted due to low loading | |||||

Structure model

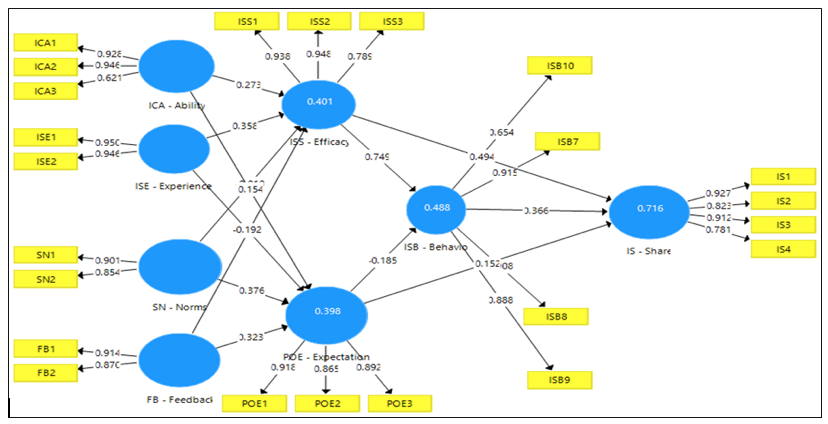

This study employed SmartPLS to test the research model for the proposed hypotheses testing. Chin (1998), stated that ‘bootstrapping was performed to determine the statistical significance of each path coefficient using t-tests.’ Figure 2 below presented the results of the analysis.

Figure 2: Research model results

Notes: * significant at p <0.1; * significant at p<0.05; ** significant at p<0.01; *** significant at p<0.001

Consistent with H1, H3, and H8, (information creation ability, information sharing experience, and feedback) the results show a significant relationship with information sharing self-efficacy. Contrary to H6, subjective norms, which fall under verbal persuasion, did not significantly relate to information sharing self-efficacy. As expected, information sharing experience (H4) and subjective norms (H5) significantly related to personal outcome expectations, but feedback (H7) had the strongest significant relationship on personal outcome expectations. Meanwhile, information creation ability (H2) did not significantly relate to personal outcome expectations. Also, information sharing self-efficacy (H9) had a stronger significant relationship on information security behaviour as compared to personal outcome expectations (H10). Furthermore, the information security behaviour (H11) had a statistically significant relationship to intention to share specific content on Facebook.

As a result, there were nine supported hypotheses (H1, H3, H4, H5, H7, H8, H9, H10, and H11) and two hypotheses (H2 and H6) not supported as presented in Table 7. All supported hypotheses showed the t-value reading at p=0.05 and p=0.2. The remaining paths were not significant as the t-value reading is lower than p=0.05.

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Std Beta | Std Deviation | T-statistics (|O/STERR|) | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Information creation ability has a significant relationship with information sharing self-efficacy. | 0.283 | 0.130 | 2.103*** | Supported |

| H2 | Information creation ability has a significant relationship with personal outcome expectations. | 0.095 | 0.144 | 0.730 | Not supported |

| H3 | Information sharing experience has a significant relationship with information sharing self-efficacy. | 0.356 | 0.133 | 2.691*** | Supported |

| H4 | Information sharing experience has a significant relationship with personal outcome expectations. | -0.255 | 0.160 | 1.596* | Supported |

| H5 | Subjective norms have a significant relationship with personal outcome expectations. | 0.397 | 0.153 | 2.478*** | Supported |

| H6 | Subjective norms have a significant relationship with information sharing self-efficacy | -0.011 | 0.104 | 0.103 | Not supported |

| H7 | Feedback has a significant relationship with personal outcome expectations. | 0.295 | 0.118 | 2.576*** | Supported |

| H8 | Feedback has a significant relationship with information sharing self-efficacy. | 0.104 | 0.074 | 1.390** | Supported |

| H9 | Information sharing self-efficacy has a significant relationship with information security behaviour. | 0.750 | 0.061 | 12.228*** | Supported |

| H10 | Personal outcome expectations have a significant relationship with information security behaviour. | -0.181 | 0.063 | 2.947*** | Supported |

| H11 | Information security behaviour has a significant relationship with the intention to share | 0.377 | 0.099 | 3.711*** | Supported |

| Note: ***significant at p>0.05 (1.96), **significant at p>0.1 (1.645) and *significant at p>0.2 (1.282) | |||||

Discussion

This study aimed to analyse the execution of social cognitive theory in the intention of sharing specific content on Facebook. The results revealed the answer to all the research questions discussed in Section 1 and are discussed below.

RQ1: What are the factors that lead to the intention to share information on Facebook?

As shown in Table 6, the results revealed that all the items, which are, information creation ability, information sharing experience, subjective norms, feedback, information sharing self-efficacy, personal outcome expectations, and information security behaviour, had a great value of loading (more than 0.5, acceptable value). Hence, we conclude that all the items are the factors that lead to intention to share specific content on Facebook. To the best of our knowledge, there is minimal research focusing on sharing specific content on Facebook.

RQ2: How do the factors relate to sharing specific content on Facebook?

As shown in Table 7, the findings indicated only two relationships were not supported, which are the relationship between information creation ability and personal outcome expectations, and the relationship between subjective norms and information sharing self-efficacy. The remaining relationships showed that there is a statistically significant relationship regarding the intention to share specific content on Facebook. Information sharing experience was validated to be an important determinant to personal outcome expectations as it explained about 89.9 percent of the variance in it. Subjective norms and feedback, which fall under social persuasion, were also important factors, whereby results indicated that both items motivate Facebook users to share specific content by their personal expectations. Meanwhile, information sharing self-efficacy and personal outcome expectations had a positive effect on information security behaviour that mediated to the intention to share specific content on Facebook.

In this research, we are clear that factors affect Facebook users’ intention to share from the perspective of specific content. The results deepen our understanding of the factors that affect Facebook users’ intention to share. Secondly, we focused on the effect of users’ specific behaviour on sharing the specific content and found that information security behaviour is the essential aspect that affects the user’s intention to share. More importantly, we surveyed users’ preferences in their intention to share, which has previously received limited attention.

RQ3: How does cybersecurity behaviour amongst netizen relate to sharing specific content on Facebook?

Both information sharing self-efficacy and personal outcome expectations were tested and revealed the positive relationship towards information security behaviour. Hence, we infer that information sharing self-efficacy and personal outcome expectations are the factors that influence information security behaviour. Information security behaviour was also tested, and we infer that this item could be considered as the factor of an intention to share specific content on Facebook. In overall, it concluded that cybersecurity behaviour amongst netizen had an impact towards sharing specific content on Facebook.

Conclusion and recommendations

In this study, we wanted to identify and understand the factors that promote the behaviour of sharing specific-content on Facebook. The research found that:

- Information creation ability, information sharing experience, and feedback are the factors of information sharing self-efficacy. Meanwhile, information sharing self-efficacy is mediated by information security behaviour that leads to the intention to share specific content on Facebook.

- Information sharing experience, subjective norms, feedback, and information sharing self-efficacy are the factors that lead to personal outcome expectations. On the other hand, personal outcome expectation is mediated by information security behaviour that leads to an intention to share specific content on Facebook.

- Information security behaviour had positively led to an intention to share specific content on Facebook.

- Information sharing self-efficacy, personal outcome expectations, and information security behaviour are the important factors when intending to share specific content on Facebook.

Several possible limitations of this study should be considered. First, this study only focused on one social media platform, which is Facebook. Some social networks such as Twitter, YouTube, blogs and many others could be examined to avoid biases in the result. Secondly, since the study is focused on Facebook users, the samples of this study are mostly personal Facebook users. It is not appropriate to infer similar findings for organisational use of Facebook. For example, the motivation to share specific content among organisational Facebook users may be different. More studies are needed to explore the differences in the future. Finally, non-responses bias may exist because most of those who responded are active members. Inactive members are less likely to fill out the questionnaires due to less frequenct use.

In conclusion, the study has attempted to understand the factors influencing the users’ information security behaviour. The results demonstrate that information sharing self-efficacy and personal outcome expectation do have a substantial explanatory impact regarding information security behaviour in the intention to share specific content on Facebook. By identifying specific conditions that influence the formation of information sharing self-efficacy and personal outcome expectations in information security behaviour, we may develop a more effective program that social network users should be able to use to promote security manners in sharing information through Facebook. Furthermore, this study helps Facebook users have a better understanding to enhance their intention to share specific content securely. This research helps to ensure that users understand the implications of their information security behaviours online. Additionally, it has contributed a new construct to a model, which is information security behaviour.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by UMRG Programme 2013, University of Malaya (RP004E – 13HNE).

About the authors

Suraya Ika Tamrin is currently a PhD Candidate at the Faculty of Computer Science and Information Technology, University of Malaya (UM), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. She obtained her Master of Office Systems Management from the Faculty of Business Management, University Technology MARA (UiTM), Puncak Alam Campus, Malaysia. Her research interests include information systems and information security management. She can be contacted at surayaika@siswa.um.edu.my

Azah Anir Norman is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Information Systems, Faculty of Computer Science and Information Technology, University of Malaya (UM), Malaysia. She completed her PhD Degree from the University of Malaya (UM). Her area of research is management information system (electronic commerce, security management, information systems). Dr Norman is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: azahnorman@um.edu.my

Suraya Hamid is a Senior Lecturer (Associate Professor) at the Department of Information Systems, Faculty of Computer Science and Information Technology, University of Malaya (UM), Malaysia. She obtained her PhD in Computing and Information Systems at the University of Melbourne, Australia. She can be contacted at suraya_hamid@um.edu.my

References

Note: A link from the title is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Al Hasib, A. (2009). Threats of online social networks. International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security, 9(11), 288-293.

- Ali, F., Amin, M., & Cobanoglu, C. (2016). An integrated model of service experience, emotions, satisfaction, and price acceptance: an empirical analysis in the Chinese hospitality industry. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 25(4), 449-475. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2015.1019172

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 161), 74-94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 842), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Prentice-Hall. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446221129.n6

- Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175–1184. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. Freeman. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.13.2.158.

- Bandura, A. (1999). A social cognitive theory of personality. In L. Pervin & O. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality (2nd ed.), (pp. 154–196). Guilford Publications. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315793177-26

- Bandura, A. (2002a). Social cognitive theory in a cultural context. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 512), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00092

- Bandura, A. (2002b). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. In J. Bryant & D. Zillman (Eds.), Media effects: advances in theory and research (2nd ed.), (pp. 121–153). Lawrence Erlbaum. https://doi.org/10.4324%2F9780203877111-12

- Barr, S. H. & Conlon, E. J. (1994). Effects of distribution of feedback in workgroups. Academy of Management Journal, 37(3), 641-655. https://doi.org/10.5465/256703

- Bock, G. W. & Kim, Y. G. (2002). Breaking the myths of rewards: an exploratory study of attitudes about knowledge sharing. Information Resource Management Journal, 15(2), 14-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.4018/irmj.2002040102

- Bock, G. W., Zmud, R.W., & Kim, Y. G. (2005). Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 87-111. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148669

- Boyd, D. M., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), 210-230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x

- Buchanan, T. (2020). Why do people spread false information online? The effects of message and viewer characteristics on self-reported likelihood of sharing social media disinformation. PLoS ONE 15(10), e0239666. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239666

- Bulut, Z. A., & Doğan, O. (2017). The ABCD typology: Profile and motivations of Turkish social network sites users. Computers in Human Behavior, 67, 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.10.021

- Cheung, W., Chang, M., & Lai, V. (2000). Prediction of Internet and World Wide Web usage at work: a test of an extended Triandis model. Decision Support Systems, 30(1), 83-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-9236(00)00125-1

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In G.A. Marcoulides (Ed.). Modern methods for business research (pp. 295-336). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Compeau, D. R., Higgins, C. A., & Huff, S. (1999). Social cognitive theory and individual reactions to computing technology: a longitudinal study. MIS Quarterly, 23(2), 145-158. https://doi.org/10.2307/249749

- Constant, D., Sproull, L., & Kiesler, S. (1996). The kindness of strangers: the usefulness of weak electronic ties for technical advice. Organization Science, 7(2), 119-135. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.7.2.119

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 318–319. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: an introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesely.

- Fitzsimmons, P. A., Landers, D. M., Thomas, J. R., & van der Mars, H. (1991). Does self-efficacy predict performance in experienced weightlifters? Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 62(4), 424–431 https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.1991.10607544

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D.F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Galletta, D. F., Henry, R., McCoy, S., & Polak, P. (2006). When the wait isn't so bad. Information Systems Research, 17(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1050.0073

- Gist, M. E. & Mitchell, T.R. (1992). Self-efficacy: a theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. The Academy of Management Review, 17(2), 183–211. https://doi.org/10.2307/258770

- Gold, J.I. (2003). Linking reward expectation to behavior in the basal ganglia. Trends in Neurosciences, 26(1), 12-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0166-2236(02)00002-4

- Gotz O., Liehr-Gobbers, K., & Krafft M. (2010). Evaluation of structural equation models using the Partial Least Squares (PLS) approach. In V.E. Vinzi, W.W. Chin, J. Henseler, and H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of artial least squares (pp. 47–82). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-32827-8

- Hair J. F., William C. B., Barry J. B., & Anderson R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. Prentice-Hall.

- Hair J. F., Ringle C. M., & Sarstedt M. (2011). PLS-SEM: indeed, a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2),139–151.

- Hashimoto, G. T., Rosa, P. F., Filho, E. L., & Machado, J. T. (2010). A security framework to protect against social networks services threats. In M. Sugano (Ed.), Fifth International Conference on Systems and Networks Communications (pp. 189-194). CPC/IEEE Computer Society.

- Henseler J., Ringle C. M., & Sinkovics R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. New Challenges in International Marketing, 20, 277–319.

- Igbaris, M., & Iivari, J. (1995). The effect of self-efficacy on computer usage. Omega: International Journal for Management Science, 23(6), 587-605. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-0483(95)00035-6

- Ismail, N., Ahmad, J., Noor, S. M., & Saw, J. (2019). Malaysian youth, social media following, and natural disasters: What matters most to them? Media Watch, 10(3), 508 – 521. http://doi.org/10.15655/mw/2019/v10i3/49690

- Johnson, R. D. (2005). An empirical investigation of sources of application-specific computer-self-efficacy and mediators of the efficacy-performance relationship. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 62(6), 737-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2005.02.008

- Kankanhalli, A., Tan, B. C. Y. & Wei, K. K. (2005). Contributing knowledge to electronic knowledge repositories: an empirical investigation. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 113-43. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148670

- Karahanna, E. & Straub, D. W. (1999). The psychological origins of perceived usefulness and perceived ease-of-use. Information & Management, 35(4), 237-250. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7206(98)00096-2

- Kellog, K. (2020, February 3). The 7 biggest social media sites in 2020. Search Engine Journal. https://www.searchenginejournal.com/biggest-social-media-sites/308897/#close (Archived by the Internte Archive at https://urlproxy.sunet.se/canit/urlproxy.php?_q=aHR0cHM6Ly9iaXQubHkvM3Uyenc0bA%3D%3D&_s=dHkubmlsc3NvbkBoYi5zZQ%3D%3D&_c=22d82e35&_r=aGItc2U%3D)

- Kolekofski, K. E., & Heminger, A.R. (2003). Beliefs and attitudes affecting intentions to share information in an organizational setting. Information & Management, 40, 521-532. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7206(02)00068-X

- Kumpel, A. S., Karnowski, V., & Keyling, T. (2015). News sharing on social media: a review of current research on news sharing users, content, and networks. Social Media + Society, 1(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115610141

- LaRose, R. & Eastin, M. S. (2004). A social cognitive theory of Internet uses and gratifications: toward a new model of media attendance. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 48(3), 358–377. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4803_2

- Larose, R., Mastro, D., & Eastin, M. S. (2001). Understanding Internet usage: social cognitive approach to uses and gratifications. Social Science Computer Review, 19(4), 395–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/089443930101900401

- Lee, M.K., Cheung, C.M. & Sia, C.L. (2006). Understanding customer knowledge sharing in Web-based discussion boards. Internet Research, 16(3), 289-303. https://doi.org/10.1108/10662240610673709

- Litwin M. S. (1995). How to measure aurvey reliability and validity. Sage Publications.

- Liu, J. (2013, May 13). Among Muslims, internet use goes hand-in-hand with more open views toward western culture. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewforum.org/2013/05/31/among-muslims-internet-use-goes-hand-in-hand-with-more-open-views-toward-western-culture/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://urlproxy.sunet.se/canit/urlproxy.php?_q=aHR0cHM6Ly9iaXQubHkvMlpwZFAwMw%3D%3D&_s=dHkubmlsc3NvbkBoYi5zZQ%3D%3D&_c=c0d24b97&_r=aGItc2U%3D)

- Lu, H.-P., & Hsiao, K.-L. (2007). Understanding intention to continuously share information on Weblogs. Internet Research,174), 345–361. https://doi.org/10.1108/10662240710828030

- Mattord, H. J., & Whitman, M.E. (2012). Principles of information security(4th. ed). Thomson Course Technology.

- Mitchell, A., & Page, D. (2014). State of the news media 2014: growth in digital reporting: what it means for journalism and news consumers. Pew Research Center.

- Munro, S. A., Lewin, S. A., Swart, T., & Volmink, J. (2007). A review of health behavior theories: how useful are these for developing interventions to promote long-term medication adherence for TB and HIV/AIDS? BMC Public Health, 7(1). https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-7-104 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-7-104 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://urlproxy.sunet.se/canit/urlproxy.php?_q=aHR0cHM6Ly9iaXQubHkvM2RzQkNFTg%3D%3D&_s=dHkubmlsc3NvbkBoYi5zZQ%3D%3D&_c=7403cf0b&_r=aGItc2U%3D)

- Ng, B.-Y., Kankanhalli, A., & Xu, Y. C. (2009). Studying users' computer security behavior: a health belief perspective. Decision Support Systems, 46(4), 815–825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2008.11.010

- Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14-37. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.5.1.14

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. (2nd. ed). McGraw-Hill.

- Petrie, H., & Gunn, D. (1998). Internet addiction: the effects of sex, age, depression and introversion. Paper presented at the British Psychological Society London Conference, London.

- Pfleeger, S. L. & Caputo, D. D. (2012). Leveraging behavioral science to mitigate cybersecurity risk. Computers & Security, 31(4), 597-611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2011.12.010

- Pookulangara, S. & Koesler, K. (2011). Cultural influence on consumers' usage of social networks and its' impact on online purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 18(4), 348–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2011.03.003

- Potosky, D. (2002). A field study of computer efficacy beliefs as an outcome of training: the role of computer playfulness, computer knowledge, and performance during training playfulness, computer knowledge, and performance during training. Computers in Human Behavior, 18(3), 241-255. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0747-5632(01)00050-4

- Rantonen, K. (2014). Explaining information security behavior: case of the home user. (Unpublished master’s thesis). Jyväskylä University, Finland. https://jyx.jyu.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/45877/URN%3aNBN%3afi%3ajyu-201505121832.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Archive by the Internet Archive at https://urlproxy.sunet.se/canit/urlproxy.php?_q=aHR0cHM6Ly9iaXQubHkvM3MzdEswZw%3D%3D&_s=dHkubmlsc3NvbkBoYi5zZQ%3D%3D&_c=055b92a0&_r=aGItc2U%3D)

- Rhee, H.-.S, Kim, C., & Ryu, Y. U. (2009). Self-efficacy in information security: its influence on end-users’ information security practice behavior. Computers & Security, 28, 816 – 826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2009.05.008

- Saini, N., Sangwan, G.,Verma, M., Kohli, A., Kaur, M., Lakshmi, P. V. M. (2020). Effect of social networking sites on the quality of life of college students: a cross-sectional study from a city in North India. The Scientific World Journal, 2020. Article ID 8576023. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8576023. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://urlproxy.sunet.se/canit/urlproxy.php?_q=aHR0cHM6Ly9iaXQubHkvMkxZMXNGNQ%3D%3D&_s=dHkubmlsc3NvbkBoYi5zZQ%3D%3D&_c=6f46ce02&_r=aGItc2U%3D)

- Silver, W. S., Mitchell, T. R., & Gist, M. E. (1995). Responses to successful and unsuccessful performance: the moderating effect of self-efficacy on the relationship between performance and attributions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Process, 62(3), 286-299. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1995.1051

- Srite, M., & Karahanna, E. (2006). The role of espoused national cultural values in technology acceptance. MIS Quarterly, 30(3), pp. 679-704. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148745

- Staples, D. S., Hulland, J. S., & Higgins, C. A. (1999). A self-efficacy theory explanation for the management of remote workers in virtual organizations. Organization Science, 10(6), 758-776. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.10.6.758

- Statista. (2017). A number of Facebook users in Malaysia from 2017 to 2023 (in millions). Statisa. https://www.statista.com/statistics/490484/number-of-malaysia-facebook-users/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://urlproxy.sunet.se/canit/urlproxy.php?_q=aHR0cHM6Ly9iaXQubHkvM3F0cGxVYw%3D%3D&_s=dHkubmlsc3NvbkBoYi5zZQ%3D%3D&_c=2ce159dc&_r=aGItc2U%3D)

- Tabrizi, A .A., & Mahmud, R. (2013). Issues of coherence analysis on English translations of Quran. In 1st International Conference on Communications, Signal Processing, and their Applications (ICCSPA), American University of Sharjah February 12 - 14, 2013. (6 p.) IEEE. https://xplorestaging.ieee.org/xpl/conhome/6479747/proceeding https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCSPA.2013.6487276

- Triandis, H. C. (1980). Values, attitudes, and interpersonal behavior. In H.E. Howe (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1979: beliefs, attitudes and values. (pp. 195–259). University of Nebraska Press.

- Urbach, N., & Ahlemann, F. (2010). Structural equation modeling in information systems research using partial least squares. Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application, 11(2), 5-40. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/301356655.pdf

- Vance, A., Siponen, M., & Pahnila, S. (2012). Motivating IS security compliance: insights from habit and protection motivation theory. Information & Management, 49(3-4), 190–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2012.04.002

- Venkatesh, V., & Morris, M. (2000). Why don’t men ever stop to ask for directions? Gender, social influence, and their role in technology acceptance and usage behavior. MIS Quarterly, 24(1), 115-139. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250981

- Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

- Wasko, M. M., & Faraj, S. (2005). Why should I share? Examining social capital and knowledge contribution in electronic networks of practice. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 35-57.

- Williams, K., Boyd, A., Densten, S., Chin, R., Diamond, D., & Morgenthaler, C. (2009). Social networking privacy behaviors and risks. Paper presented at the Michael L. Gargano 7th Annual Research Day, Friday May 8th , 2009. http://csis.pace.edu/~ctappert/srd2009/a2.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://urlproxy.sunet.se/canit/urlproxy.php?_q=aHR0cHM6Ly9iaXQubHkvM2FzNXdxQQ%3D%3D&_s=dHkubmlsc3NvbkBoYi5zZQ%3D%3D&_c=923c9183&_r=aGItc2U%3D)

- Wixom, B., & Todd, P. A. (2005). A theoretical integration of user satisfaction and technology acceptance. Information Systems Research, 16(1), 85-102. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1050.0042

- Wood, R., & Bandura, A. (1989). Social cognitive theory of organizational management. The Academy of Management Review, 14(3), 361-384. https://doi.org/10.2307/258173

- Zannettou, S., Sirivianos, M., Blackburn, J., & Kourtellis, N. (2019). The Web of false information: rumors, fake news, hoaxes, clickbait, and various other shenanigans. Journal of Data and Information Quality, 11(3), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1145/3309699