Attributes that influence academics' data sharing in Nigeria: the effects of organization culture

K. A. Abdullahi and A. Noorhidawati

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper908

Introduction. This study was conducted to ascertain the attributes that influence data sharing practices among academics in Nigerian universities. Nigeria is known to be a country with limited resources to acquire digital paraphernalia which may restrict data sharing practices. The purpose of this study was to investigate factors that influence research data sharing practices among academics in Nigeria. The scope entails a broad context in the lens of organization cultural theory as efforts in data sharing practice are hypothesized to be influenced by institutional involvement besides individual decision.

Method. A survey questionnaire was used as the instrument for data collection. A random sample consisting of 378 academics represented the academics in Nigeria.

Analysis. Partial least square analysis was employed to evaluate the proposed model.

Results. The findings indicated several factors which had influenced data sharing practices among academics in Nigeria including organizational, personal, and social attributes.

Conclusion. This study is important to extend knowledge on data sharing behaviour particularly for academics in a periphery country like Nigeria and the attributes expected to influence these practices.

Introduction

Research data sharing can be traced to the open science movement with open data as a subset of research data sharing. Borgman (2012) described data sharing as enabling the availability of research datasets for use by other researchers. Data sets are usually attached to scholarly articles, deposited in repositories, or kept on personal computers or local servers (Wallis, et al., 2013). One of the main contributions to research and development of data sharing is that it could minimize data re-collection, hence optimising the use of resources (Tenopir, et al., 2011). Data sharing practices among academics are essential to provide transparency and credibility of research findings, and evidence to support research frameworks (Kim and Adler, 2015).

There is a high participation in data sharing practices in developed countries such as United Kingdom and United States of America (Byrd, et al., 2020). This has led to reproduction of research outcomes (Agosti, et al., 2018), recovery and retrieval of old data (Moss, et al., 2015), intensification of research efficiency and regenerating of research data among academics (Gregory, et al., 2018). Data sharing in these countries is encouraged and is increasingly being adopted and enabled through advanced open storing and sharing platforms and technologies. Studies have shown a significant relationship between these nations’ attitudes towards advancing research, protecting privacy, and beliefs about risks and benefits of data sharing (Shah, et al., 2019). Overall, findings have revealed that researchers in advanced nations do prioritise privacy and there is a strong need to control data types shared and with whom data will be shared (Shah, et al., 2019).

In the past, researchers shared their research outputs only through journal articles; now, it has become necessary to embark on other sharing exercises such as data sharing (Shen, 2016). Despite the benefits of data sharing, there is not much literature reporting data sharing practices among the academics particularly in Nigeria (Adam and Usman, 2013). This is probably due to a growing concern in less developed nations regarding how data are managed and the problems related to it (Odigwe, et al., 2020). In Nigeria, there have been limited studies reporting data sharing practices among academics.

This paper, therefore, aims to address this gap by investigating what influences (or hinders) data sharing among academics in Nigeria, in a broader perspective than just available information technologies. This study also aims to investigate attributes from the Theory of Organizational Culture which states that data sharing practices are not only influenced by individual characteristics but also by activities in the organization and social environment. The objective of this study, therefore, is to identify those attributes that encourage or obstruct data sharing practices among researchers in context of Nigerian universities. The research question formulated in this research is: What are the attributes that influence data sharing practices among academics in Nigeria?

Literature review

Open science is a process where people collaborate, contribute, and make research data and research processes freely available to be reused, re-distributed and reproduced (Mons, et al., 2017). Open science comprises activities that promote sharing output, resources, methods, or tools at any stage of the research process. Data sharing is one of the components in open science under the umbrella of open data. Open data signifies sharing and reusing research data and relevant materials when conducting research work (Foster and Deardorff, 2017). Research data sharing practice is aligned with the principle of openness through the entire research cycle, encouraging sharing and collaboration as early as possible (McKiernan, et al., 2016; Morey, et al., 2016). One important component of research is the transparency and reproducibility of the research results. Lack of transparency is, therefore, a setback to research development. Consequently, data sharing is the practice of making scholarly research data to be available and possible re-used by other investigators which has recently gather attention among academic communities driven to improve their reputation (Linek, et al., 2017).

The needs for data sharing have been recently more emphasised around the scholarly world (Shen, 2016). The spirit of openness of research data in an academic environment is gaining momentum as more research funders and journals call for more openness of research results (Gewin, 2016; Nosek, et al., 2015; Vicente-Sáez and Martínez-Fuentes, 2018). The absence of research data on a shared platform can be seen as a threat to verifying the results and conclusions of empirical studies. Open data is expected to solve this problem by ensuring the data are freely accessible. Previous studies revealed that academics. particularly medical practitioners, health policy analysts, and other researchers from the sciences become more self-assured when their results and conclusions can be verified (Allen and Mehler, 2019; Hardwicke, et al., 2018; Naudet, et al., 2018). Thus, the value of researchers increases with more openness and transparency and enables the prospective external researchers to reanalyse and build on previous data. Hence data sharing is essential to for public accessibility and reusability.

Those emphasising data sharing in academic environment gain its benefits but not without some problems. Researchers have realized that they must make their data accessible to attain research progression. Their awareness of such initiatives in data sharing was due to the requirements by journals and funding agencies to deposit their data in data repositories for open accessibility. This practice is enforced by journal publishers, research funders and individuals who wish to further cross-examine their scientific conclusions (Boulton, et al., 2011). There are existing studies which have reported developing new competences in data sharing, data quality, standards, and protection, which had increased researchers’ willingness to share their data (Sayogo and Pardo, 2013).

However, opinions and practices regarding data sharing seem to differ among various disciplines (Creaser, et al., 2010) which have embraced data sharing practices differently. In some disciplines, such as cognitive neurosciences, data sharing is still in the early stages. It is a notable challenge for neuroscience laboratory work and collaborative projects to practise data sharing as an effective form of data management (International Brain Laboratory, et al., 2020). Within sciences such as genomics, researchers share data when requested by peers to gain credit for their work and expect their data will not be misused (Tenopir, et al., 2015). In genetics, genomics and structural biology, shared large datasets are common (Karczewski and Francioli, 2017), and many researchers have used and re-used previously published datasets to enable new discovery (Bonàs-Guarch, et al., 2018).

In physical sciences such as astronomy and astrophysics, telescope data is typically made open (Bhatnagar, 2018). It is a normal practice to share data in ecology as the nature of the field requires and benefits from open data (Baker and Millerand, 2016; Reichman, et al., 2011). This is evident from the increased amount of shared ecology data reported (Michener, 2015) as well as publications in databases supported by large networks of researchers (Gilbert, et al., 2014). In social sciences and humanities, there is a need to access data to replicate existing studies. This practice of sharing data, unfortunately, is not encouraged in social sciences (Kim and Adler, 2015).

Thus, research data sharing practices are given more priority in the field of sciences than in the non-science fields (Kim and Stanton, 2016). There is also support from research stakeholders such as United States’ National Science Foundation, which mandates data sharing practices for grant recipients (Alter and Gonzalez, 2018). In the future, data sharing practices should be accepted across all academic fields because transparency and openness are considered by many to be part of scientific method.

Reviewing the literature has shown that researchers are aware of the benefits and willing to share their research data with others. Despite being aware of the benefits, researchers are also influenced by certain issues that make them less willing to share their data. These include: the potential misinterpretation of data, (un)ethical use of data by government and commercial purposes (Howe, et al., 2018), and how their data would be used once it is shared (Kiran et al., 2015). Researchers need to know more about their potential data users before agreeing to share their data (Asai, et al., 2002.). Studies have shown that researchers might be unaware that their data had already been shared by others (Hate, et al., 2015). For all these reasons, they might choose not to share their data.

The importance of data sharing practices among researchers cannot be over emphasised (Kim and Stanton, 2016; Tenopir, et al., 2011) although journal publishers and research funders have found low take-up of data sharing across some disciplines (Houtkoop, et al., 2018). Despite the advantages of open access, only a small number of researchers are willing to share their research data (Dahrendorf, et al., 2019; Hardwicke, et al., 2019). Stakeholders, such as other researchers, journal publishers, funders, and universities, have expressed their concerns about data sharing practices and its transparency and have demanded an improvement in data sharing structures (Munafò, et al., 2017; Nosek, et al., 2015).

Although data sharing is strongly encouraged globally, researchers from Nigeria were observed to be unwilling to share their research data, information, and knowledge (Awodoyin, et al., 2016). Awodoyin et al. reported that although some data or knowledge were shared through face-to-face interactions, emails and mobile phones, it was not through established or standard platforms set up by institutions, journal publishers or funding agencies (Kaye, et al., 2018). Developing infrastructures, policies and incentives to facilitate data sharing practices would reduce false research, intensify research value and encourage research transparency (Chawinga and Zinn, 2019; Johnson, et al., 2019).

Institutions are reviewing their data-handling policies to ensure research data can be validated and preserved to enable discoverability and reuse by other investigators (MacMillan, 2014). Government agencies such as National Institutes of Health (with the National Institutes of Health Public Access Policy), and Research Councils UK (RCUK, now UK Research and Innovation (UKRI)) have adopted open-access mandates for grant recipients. They have also established policies that require authors to deposit into various data repositories. With the increasing number of research data sharing initiatives, publishers of journals with high impact factors have recently enacted policies requiring authors to share their data (Tannenbaum, et al., 2018). Policies and guidelines endorsed by organizations like the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health (GA4GH) and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) have promoted and recommended that data sharing initiatives should include governance, privacy and security protections, and data access in a transparent manner and through accessible digital platforms (Villanueva, et al., 2019). The policies established by the research funders and journals have shown a growing awareness of the importance of data sharing practices across academics although they might have implications as they would remain a significant risk to most of the researchers (Avuglah and Underwood, 2019).

Data sharing practices can be influenced by factors such as individual characteristics of the data provider, the organization, and the social environment surrounding the research activities. Several related studies have employed the theory of organizational culture to determine how individuals interrelate with each other and act with individuals outside their organisation (Kenter, et al., 2016; Little, et al., 2018). Idang (2015) provides insight into how different values can be seen as part of the organizational culture and how the shared set of values and beliefs contributes to organizational success. Other studies have reported the impact of organizational culture on knowledge management process and the potential implications of organizational culture towards sharing data (Lee et al., 2016; Tong, et al., 2015).

The research framework: theory of organizational culture

There are a few theories related to data sharing in an organization including the theory of organizational culture, theory of planned behaviour, institutional theory and social exchange theory (Oloruntoba, et al., 2019). Research data sharing practices are influenced not only by individual behaviour but also by the environment (i.e., organization culture) that either facilitates or discourages such practices. This study investigates attributes that influence data sharing practices among Nigerian academics in a broad perspective including both organisational and social interaction levels.

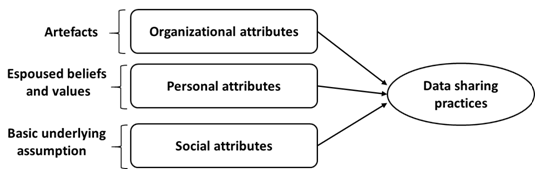

Organizational culture includes a system of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs which demonstrates proper and improper behaviour of people in organization (Chatman and Cha, 2003; Kerr and Slocum, 2005). Schein (1990) explains the theory of organizational culture through three elements:

- Artefacts: noticeable expressions of culture such as structures, practices and processes, rituals, technology, manner of dress and language. They are things that can be seen, heard and felt including constructs like organizational structures, infrastructures, data repositories, funding agencies, journal publishers, and policy/guidelines.

- Espoused belief and values: described as looking for a motive behind any observed artefact (Sangiovanni-Vincentelli, 2007). Some examples are creativity, problem solving and relating with others. Constructs include conditions for data sharing, perceived effort, anticipated benefits, legitimate concern, and altruism.

- Basic underlying assumptions: described as unconscious features of organizational culture which includes elements like perception, thoughts and feelings. These assumptions are very hard to change.

Figure 1 shows the mapping of the theory of organizational culture with related attributes: organizational attributes (Artefacts), personal attributes (Espoused beliefs and values), and social attributes (Basic underlying assumptions).

Figure 1: Mapping theory of organizational culture and data sharing attributes

Hypothesis development

This research is built based on the theory of organizational culture by Schein (1990) who explains the theory through three elements: artefacts (organizational attributes), espoused beliefs and values (personal attributes) and basic underlying assumptions (social attributes). The following sections examine the relationship between these three elements and data sharing practices.

(a) Relationship between organizational attributes and data sharing practices

Organizational attributes are considered to be factors associated with visible expression of the organization that can be easily viewed, heard and felt by individuals. They include internal and external organizational aspects like structures, practices and processes, and technology (Barrios, 2013). These attributes are easily discovered and acknowledged:

I. Internal organizational attributes include:

- Organizational structures: involve leadership of a particular organization in handling data sharing practices. An organization’s management can influence practices of data sharing by its members. This has been reported by Ünal et al. (2019) who indicated that proper management of data by members throughout the research process is crucial to make data openly accessible, intelligible, and usable.

- Infrastructure: can be seen as those fundamental facilities in an organization to support data sharing activity. Availability of such infrastructure to researchers can influence their behaviour in data sharing uptake.

- Policy/guidelines: imposed by various regulatory bodies such as university authorities, funding agencies, or journal publishers and could also influence data sharing activities. There are various data sharing policies and guidelines that academics must be aware of as they embark on data sharing activities.

II. External organizational attributes include:

- Data repositories: platforms used in data sharing practices. These could be built in-house and managed by the organization or could be commercial ones.

- Research funders: agencies that drive data sharing practices through establishing data sharing policies to ensure researchers make their data open and available to others for research replication.

- Journal publishers: play an important role in driving data sharing practices. Earlier studies have shown that journal publishers require authors to deposit their data, and this had affected researchers’ behaviour towards data sharing practices (Taichman, et al., 2016).

Based on the discussion above, the following hypotheses were postulated:

H1a Infrastructure positively influenced academics’ data sharing practices.

H1b: Data repository positively influenced academics’ data sharing practices.

H1c: Organizational structure positively influenced academics’ data sharing practices.

H1d: Research funders positively influenced academics’ data sharing practices.

H1e: Perceived pressure by journal positively influenced academics’ data sharing practices.

H1f: Policies and guidelines positively influenced academics’ data sharing practices.

(b) Relationship between personal attributes and data sharing practices

Personal attributes are basic underlying assumptions that are described as unconscious features of the organizational culture which include elements of individual perceptions, thoughts and feelings. These assumptions are very hard to change (Schein, 1990). Personal attributes comprise:

- Expected rewards: a situation where those participating in sharing (researchers) understand that data sharing may offer rewards like promotion, reputation, and recognition. This has been observed by many scholars: professional recognition (Kim, 2007), institutional recognition (Kankanhalli, et al., 2005), and academic reward (Kling, et al., 2003).

- Effort expectancy: described as the time and energy that needs to be allocated to embark on data sharing activities. Researchers may believe that it takes up a lot of time to form, fix and prepare the data for sharing, which can result in them withholding data. The time and effort required to share data may be distressful particularly when they have lack of time and funds to support such activities (Tenopir, et al., 2011).

- Conditions for data sharing: circumstances that may warrant an individual sharing data. This may involve the rights to publish the results, proper attribution of the data source, familiarity between sharer and recipient, research funders’ expectations, and the amount of effort required to share with others (Wallis, et al., 2013).

- Legitimate concerns: these include potential uncertain and negative outcomes in the process of sharing data. Researchers consider data sharing as a risk that can involve losing publication, misuse, misinterpretation, and criticism by their peers; this may negatively influence researchers’ data sharing practices. When data sharing become risky, there would be doubt as to whether to share or not data with other researchers. In social sciences, for example, researchers were worried that data sharing might lead to misuse of their data and potentially have a negative impact on their career as researchers (Kim, et al., 2015).

- Beneficence: strong desire to help others through data sharing practices. Some researchers are willing to share their data in the spirit of knowledge development and creation as reported by Fecher et al. (2015) and Kim and Stanton (2012).

Based on the discussion above, the following hypotheses were postulated:

H3a: Expected rewards positively influenced academics’ data sharing practices.

H3b: Effort expectancy positively influenced academics’ data sharing practices.

H3c: Conditions for data sharing positively influenced academics’ data sharing practices.

H3d: Legitimate concern positively influenced academics’ data sharing practices.

H3e: Beneficence positively influenced academics’ data sharing practices.

(c) Relationship between social attributes and data sharing practices

Social attributes are formed by interaction with other people over one’s lifetime; that is, how and where we relate with one another which includes discipline norms and community culture. Two aspects are relevant:

- Disciplines: some disciplines are more receptive to data sharing (e.g., astronomy) while others have well established culture and experiences of sharing research data with their colleagues (e.g., physics; see Kim and Stanton, 2013). Certain disciplines may consider data sharing as part of their professional responsibility and are expected to value and be deeply involved in its practices (Kim and Stanton, 2012).

- Community culture: the collective principles, thoughts, and standards that have an emotional impact on community’s performance (Jones, et al., 2006). Consent from members may lead to the collective involvement in data sharing practices. Sharing data among researchers in some communities raises a lot of sociocultural concerns (Hirschfeld, 2012; Pearce and Smith, 2011; Visscher and Weissman, 2011).

Based on the discussion above, the following hypotheses were postulated:

H2a: Discipline norms positively influenced academics’ data sharing practices.

H2b: Community culture positively influenced academics’ data sharing practice.

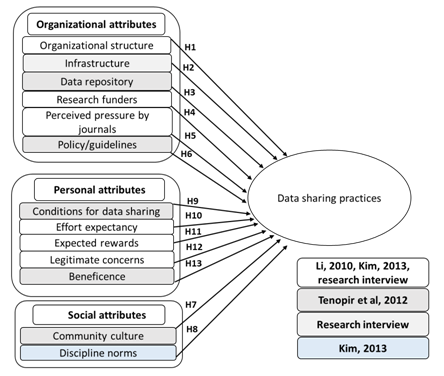

Figure 2: Attributes in data sharing practices

Method

This study employed semi-structured interviews and a survey to investigate factors that influenced research data sharing among academics in Nigeria. Twenty-two academics who were senior researchers were sampled for interviews that lasted 25-30 minutes. The interviews were audio-recorded with the respondents’ permission. The data were coded, and the themes that emerged indicated several aspects that influenced data sharing behaviour. The findings from the interviews were used to develop the survey instrument.

Self–administered survey questionnaires were distributed among the academics in Nigeria. From a population size of 7,561, a sample of 364 was determined based on Krejcie and Morgan (1970). Stratified sampling technique was used to gather the sample from five universities in Nigeria as shown in Table 1. A total of 440 (over sample) survey questionnaires were distributed, resulting in 378 responses which made an 86% response rate. Data from the survey were analysed using Smart-PLS to statistically confirm the influencing factors of data sharing practices in the context of Nigeria.

| University | Population | Stratified sampling | Survey distributed | Useful responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University | 2098 | 2098/7561 x 364 =101 | 120 | 101 |

| Moddibbo Adama University of Technology | 2231 | 2231/7561 x 364 = 107 | 120 | 107 |

| Federal University Kashere | 1023 | 1023/7561 x 364 = 49 | 70 | 60 |

| Federal University Wukari | 1106 | 1106/7561 x 364 = 53 | 65 | 56 |

| Federal University Yobe | 1003 | 1003/7561 x 364 = 48 | 65 | 54 |

| Total | 7561 | 440 | 378 |

Measures

The instrument was developed based on the theory of organizational culture and included organizational, personal, and social attributes. There were thirteen constructs categorised under these attributes. The questionnaire items were developed based on the interview findings and adapted from the literature (Table 2). The questionnaires used a 5-point Likert scale which allowed respondents to indicate a neutral response making the scale scores more reliable; this is also preferred by respondents (Adelson and McCoach, 2010).

| Constructs | Measurement variables | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Personal attributes | Effort expectancy (EE) | Vanneste et al. (2013), Kim (2013), Research interviews* |

| Legitimate concerns (LC) | Taichman et al. (2016), Kim (2013), Research interviews* | |

| Beneficence (BNC) | Wilbanks and Friend (2016), Tenopir, et al. (2011), Research interviews* | |

| Conditions for data sharing (CFDS) | Borgman (2012), Tenopir et al. (2011), Research interviews* | |

| Expected rewards (ER) | Eshel et al. (2016), Kim (2013), Research interviews* | |

| Organizational attributes | Organizational structure (OS) | Schein (1985) |

| Infrastructure (INF) | Research interviews * | |

| Data repository (DR) | Horai et al. (2010), Tenopir et al. (2011) | |

| Research funders (RF) | Piwowar (2011), Kim (2013), Research interviews* | |

| Perceived pressure by journal (PPJ) | Tenopir et al. (2015), Kim (2013), Research interviews* | |

| Policy/guidelines (PG) | Tenopir et al. (2011), Research interviews* | |

| Social attributes | Community culture (CC) | Research interviews* |

| Discipline norms (DN) | Kim (2013) | |

| Note: * Interviews were conducted to develop specific questions for the attributes | ||

Validity and reliability

Validity and reliability are two significant factors to consider when developing and testing a survey instrument. They help to ensure the quality of the measurement and the data collected. To reach good reliability and validity, content validity and convergent validity were conducted to achieve internal consistency, average variance, and discriminant validity.

Content validity was secured by modifying most of the survey items from preceding studies via exhaustive literature review. The survey items were also presented to a panel of five experts in the area of this study. They were provided with the measurement items and scrutinized the survey items in terms of the appropriateness and completeness of the measurement of each construct. Some survey items were amended in response to the comments, recommendations, and suggestions made by the panel of experts.

Convergent validity is the degree to which the single item correlates positively with the reflective multi-item measure of service value (Mooi, et al., 2018). Convergent validity is evaluated at the construct level via the average variance extracted (AVE). The common method to measure the internal consistency is using Cronbach's alpha, which provides an estimate of the reliability based on the inter-correlations of the observed indicator variables. It is, however, sensitive to the number of items in the scale and may lead to underestimating the internal consistency reliability. Therefore, it is normally recommended to use a different measure of internal consistency reliability, which is referred to as composite reliability. Composite reliability considers the different outer loadings of the indicator variables and is calculated using the following formula: if the composite reliability is larger than 0.7, it is acceptable. For this study, the composite reliability is between 0.88 and 0.95, while the average variance extracted is above 0.5. Therefore, convergent validity is adequate for all the constructs (see Appendix A).

Discriminant validity was used to test whether unrelated concepts or measurements that are not supposed to be related are actually unrelated. Thus, discriminant validity proposes that a construct is unique and captures phenomena not described by other constructs in the model. (Hair, et al., 2014). Discriminant validity is tested by evaluating the squared average variance extracted for each construct against correlations (shared variance) between the construct and all other constructs in the model. A construct has an adequate discriminant validity if the squared average variance extracted exceeds the correlation among the constructs (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Table 3 shows the correlation of latent variables and discriminant validity based on Fornell and Larcker. Table 3 also shows that the average variance extracted for each construct is more than each of the squared correlation between constructs. Therefore, discriminant validity is adequate for all constructs.

A pilot study was conducted to make sure that the various scales proved an appropriate level of reliability. The result of the pilot study revealed that the construct reliability constructs were satisfactory. It was discovered that 10-20 minutes was taken to complete the pilot survey. No significant changes were made to the survey questions.

Analysis method

Partial least squares was employed using SmartPLS software to effectively show the reliability of this study, by calculating convergent validity, discriminant validity and the path coefficients of all the factors under the three main attributes. The path coefficients which show the hypotheses testing evaluation is shown in Table 5 indicating all the thirteen independent variables were evaluated and found to be significant on data sharing practices.

| ER | BNC | CFDS | DN | DSP | RF | INF | PJJ | LC | CC | OS | DN | EE | PG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | 0.811 | |||||||||||||

| BNC | 0.313 | 0.890 | ||||||||||||

| CFDS | -0.353 | -0.201 | 0.829 | |||||||||||

| DN | 0.248 | 0.390 | -0.168 | 0.902 | ||||||||||

| DR | 0.253 | 0.090 | -0.139 | 0.047 | 0.863 | |||||||||

| DSP | 0.623 | 0.519 | -0.361 | 0.525 | 0.332 | 0.878 | ||||||||

| RF | 0.229 | 0.300 | -0.090 | 0.294 | 0.163 | 0.523 | 0.765 | |||||||

| INF | 0.295 | 0.197 | -0.103 | 0.259 | 0.264 | 0.424 | 0.222 | 0.866 | ||||||

| PPJ | 0.315 | 0.316 | -0.202 | 0.390 | 0.017 | 0.442 | 0.190 | 0.169 | 0.878 | |||||

| LC | -0.334 | -0.131 | 0.082 | -0.185 | -0.266 | -0.454 | -0.186 | -0.326 | -0.131 | 0.896 | ||||

| CC | -0.312 | -0.169 | 0.205 | -0.162 | -0.258 | -0.428 | -0.203 | -0.235 | -0.131 | 0.327 | 0.905 | |||

| OS | 0.350 | 0.264 | -0.207 | 0.278 | 0.136 | 0.444 | 0.222 | 0.113 | 0.301 | -0.092 | -0.193 | 0.852 | ||

| EE | -0.139 | -0.126 | 0.057 | -0.144 | -0.144 | -0.313 | -0.073 | -0.138 | -0.105 | 0.310 | 0.111 | -0.151 | 0.774 | |

| PG | 0.260 | 0.143 | -0.086 | 0.145 | 0.118 | 0.317 | 0.148 | 0.211 | 0.164 | -0.158 | -0.245 | 0.210 | -0.104 | 0.838 |

| *All correlations are significant at the p< 0.01 level. The square roots of the average variance extracted are shown on the diagonal in bold. | ||||||||||||||

Results

Demographic characteristics of the survey respondents

The results indicated that 79.6% (301) of the respondents were male and 20.4% (77) were female. About half of the respondents (44.7%) were between thirty-one and thirty-five years old. One third of the respondents had 11-15 years of experience in academia (36.5%). Non-science disciplines accounted for 57.1% respondents and the remaining 42.9 % were from sciences (see Table 4).

| Variable | Level | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 301 | 79.6 |

| Female | 77 | 20.4 | |

| Age | 21-25 years old | 17 | 4.5 |

| 26-30 years old | 46 | 12.2 | |

| 31-35 years old | 169 | 44.7 | |

| ≥40 years old | 146 | 38.6 | |

| Years in academia | ≤5 years | 22 | 5.8 |

| 6 -10 years | 78 | 20.6 | |

| 11-15 years | 138 | 36.5 | |

| 16-20 years | 106 | 28.0 | |

| 21 years | 34 | 9.0 | |

| Field | Sciences | 162 | 42.9 |

| Non-Sciences | 216 | 57.1 |

Attributes that influenced data sharing practices of academics in the context of Nigerian universities

Three attributes, organizational, personal and social, were significantly correlated with data sharing practices as shown in Table 5. All six organizational attributes (structure, infrastructure, data repositories, research funders, journal publishers and policy/guidelines), two personal attributes (beneficence and expected rewards), and one social attribute (discipline norms) indicated a positive significant relationship with the data sharing practices of the academics. The results revealed that organizational attributes are the most significant attributes that influenced academics’ data sharing practices. However, conditions for data sharing, effort expectancy, legitimate concerns and community culture are negatively correlated with data sharing practices. The results revealed that personal attributes are the most pessimistic elements that influenced academics’ data sharing practices as three out of five attributes were negatively related. Among all the attributes, expected rewards had the most positive significant relationships with β=0.235 and legitimate concern had the most negative significant relationships with β= -0.130.

| Path coefficients | SD | t-Values | P Values | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational attributes | |||||

| Organizational structure (OS) -> Data sharing practices | 0.094 | 0.030 | 3.111 | 0.001 | Supported |

| Infrastructure (INF) -> Data sharing practices | 0.079 | 0.023 | 3.360 | 0.001 | Supported |

| Data repository (DR) -> Data sharing practices | 0.082 | 0.027 | 3.061 | 0.001 | Supported |

| Research funders (RF) -> Data sharing practices | 0.234 | 0.026 | 8.970 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Perceived pressure by journal (PPJ)-> Data sharing practices | 0.096 | 0.029 | 3.283 | 0.001 | Supported |

| Policy/guidelines (PG) -> Data sharing practices | 0.049 | 0.025 | 1.944 | 0.026 | Supported |

| Personal attributes | |||||

| Beneficence (BNC) -> Data sharing practices | 0.157 | 0.030 | 5.293 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Conditions for data sharing (CFDS) -> Data sharing practices | 0.098 | 0.023 | 4.177 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Effort expectancy (EE)-> Data sharing practices | -0.110 | 0.030 | 3.708 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Expected rewards (EE) -> Data sharing practices | 0.235 | 0.030 | 7.724 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Legitimate concerns (LC) -> Data sharing practices | -0.130 | 0.027 | 4.788 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Social attributes | |||||

| Community culture (CC) -> Data sharing practices | -0.096 | 0.025 | 3.889 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Discipline norms (DN) -> Data sharing practices | 0.169 | 0.028 | 5.963 | 0.000 | Supported |

Discussion

Identifying attributes of research data sharing among academics has been a prominent topic of interest in universities (Ünal, et al., 2019). The data presented in this study represent the three attributes (organizational, personal and social) that had influenced data sharing among academics in Nigeria.

Organizational attributes are those attributes that show the overall well-being of the organization include organizational structure, infrastructure, data repositories, research funders, perceived pressure by journal publishers, and policy/guidelines.

- Organizational structure was found to have positive influence on data sharing practices through a mandate by the institution management in developing rules, regulations, and standard procedures.

- Infrastructure was found to have positively determined data sharing practices, indicating that having good infrastructure in place could support participation in research data sharing practices. This outcome was corroborated with previous studies that reported the same findings related to infrastructure such as data sharing platforms (Cao, et al., 2017) and Internet connectivity (Roberts, et al., 2017) which had influenced data sharing practices among academics.

- A data repository was also found to have a significant positive effect on data sharing practices. The availability of data repositories in universities had increased data sharing practices among academics across different disciplines as reported by Cragin et al. (2010) and Hemminger (2010). A data repository motivates other investigators to share their data regardless of their discipline.

- Research funders were found to have significant positive relationship with data sharing practices. This corresponded with previous studies which established that activities of research funders had a positive impact on data sharing practices among academics (McGuire, et al., 2008).

- Journal publishers have a weighted control on data sharing practices. Some journal publishers had made it conditional for authors to deposit their data in the publisher’s platform; some had made it mandatory; while others made it voluntary. This finding was consistent with previous studies which stated that there was a positive correlation between journal conditional regulations and data sharing in public databases (Piwowar and Chapman, 2010).

- This study revealed a correlation between established policies or guidelines and data sharing practices, supporting previous studies that had measured policies on research data sharing practices (Wouters, 2002), policies or guidelines imposed by journal publishers (Gewin, 2016), and research funders (Cook-Deegan, et al., 2017). This is logical due to the current technology and infrastructure. Data sharing should be supported through appropriate data repositories (Mannheimer, et al., 2019).

To summarize, all organizational attributes measured in this study have been shown to influence data sharing practices.

In this study, personal attributes are those characteristics of an individual that encompass effort expectancy, legitimate concerns, beneficence, conditions for data sharing, and expected rewards.

- Effort expectancy was found to have a significant negative effect on data sharing practices. Academics who notice that their involvement in data sharing requires more effort may not be willing to share their data with others.

- Legitimate concerns also had a negative significant relationship with data sharing practices. This had to do with the potential uncertainty and negative outcomes in the process of sharing data, which made the academics reluctant to share their research data.

- Beneficence is the willingness of a person to offer benefit and contribute to societies without anticipating something in return (Hsu and Lin, 2008). Beneficence was recognized to have a positive significant relationship with data sharing practices and inspired academics to share their data with others.

- Conditions for data sharing, which are certain conditions placed by academics that would guarantee the safety and privacy of their data, were found to have a negative significant relationship which means the participants would share their data even though the conditions were not aligned with their requirements.

- Expected rewards indicated a significant positive correlation on data sharing practices. Anticipated benefits of data sharing practices are likely to influence academics to make their data readily available to others.

These personal attributes complement findings from other studies into expected rewards (Allen and Mehler, 2019; Bezuidenhout, 2019), legitimate concerns (Ballantyne, 2019; Banks, et al., 2019; Spallek, et al., 2019), conditions for data sharing (Polanin and Terzian, 2019), beneficence (Hummel, et al., 2019; Ross, et al., 2018), and effort expectancy (Campbell, et al., 2019; Spallek, et al., 2019; Tenopir, et al., 2015). All these factors had profound effect on data sharing practices of individuals.

Social attributes in this study refer to characteristics emanated from the social interactions among the academics: community culture and discipline norms.

- Community culture describes social behaviour of people in a community. The findings signify a negative correlation of community culture with data sharing practices which indicates that people in a community who perceived data sharing as against the normal practices and/or customs are less likely to share their data with others.

- Discipline norms are those values set by the academics in their respective field of studies. They were found to have positive relationship with data sharing. This means that those disciplines with norms that encourage sharing are likely to partake in data sharing as compared with those without such norms. For example, in science, there is a growing awareness of the need for data access and sharing than the non-science disciplines (Zhao, et al., 2018). Social relations inspire people in an organization to act and benefit from each other. When people have a common forum and develop responsive relations with each other in an organization, they have a tendency to share more data (Borgman, 2018).

The use of the theory of organizational culture in this study has enabled the researchers to appropriately analyse the influence of organizational, personal and social attributes on data sharing among academics. It also enabled us to provide insight into how values can be seen as part of a culture and their influence on research data sharing practices.

Conclusion

This study has contributed to the body of knowledge by investigating attributes of data sharing practices among academics in Nigeria. The findings have added to the knowledge gap on research data sharing culture and the factors that influence the practices. This study employed Schein’s (1985) theory of organizational culture to provide a more complete view of research data sharing practices that involved organizational, personal and social attributes as dictates by artefacts, espoused belief and values, and basic underlying assumption (Bailey, et al., 2019). Within this framework, it can be concluded that data sharing practices among academics are influenced by organizational attributes (organizational structure, infrastructure, data repository, research funders, perceived pressure by journal and policy/guidelines), personal attributes (conditions for data sharing, effort expectancy, expected rewards, legitimate concerns and beneficence) and social attributes (community culture and discipline norms).

This paper also discovered new items such as community culture and infrastructure that are important factors in the uptake of data sharing practices in the Nigerian context. Findings presented in this study can show academics, journal publishers and research funders the perceived risks in data sharing, promote the sharing and reuse of research data, and create awareness among academics of data sharing sources. It can be concluded that academics have opportunities to advance in their research while keeping their data freely available to other researchers.

Recommendations and limitations

Some recommendations can be made:

- First, encourage adequate data citation practices. Academics are not eager to share data because they are worried about data falsification or misuse of data. Proper acknowledgement of data creators would be critical as a reward for their efforts in creating and sharing data. Data citation should be encouraged as a core data sharing practice to ensure adequate attribution and credit is given to data providers.

- Secondly, design a policy that allows data providers to exercise control over the shared data access. From the findings of this study, academics who were less willing to make their data available recommended that they should be able to place conditions on the accessibility and permissions required to disseminate the shared data. It was also recommended that researchers retain the right to publish before sharing data with others. One way of implementing such a policy is to disallow data usage for a certain period of time. This publication suspension policy has been adopted in genomics projects to reward data providers and ensure data quality (Roche, et al., 2014).

- Thirdly, ethical and disciplinary issues related to co-authorship in return for data sharing should be emphasised and academics given more opportunities for co-authorship and collaboration. Research collaboration is commonly operationalized as co-authorship and several studies have noted that one of the motivations for data sharing was expectation of co-authorship (Borgman, et al., 2007; Cragin, et al., 2010). Co-authorship issues also imply that academics need to understand that credit should be conferred for researchers’ works, including data in academic reward systems.

The limitation in this study is that only responses from academics were included. Further studies should be carried out to investigate research data sharing from other perspectives such as local policy makers at the institutional level, funding agencies and the public. The scope of future studies could be broadened to cover research data management closely related to data sharing activities. Although this study employed a survey as the data gathering technique, rigorous mixed methods design that includes interviews might be suitable to further explore the reasons to support or not support data sharing practices. The survey was focused on universities although data sharing practices may display different prevalence and be influenced by different attributes in other high institutions of learning. Despite these limitations, this study clearly has defined some distinctive attributes that influence academics in developing nations and demonstrated some of the policies and practices about data sharing practices among academics. More research in this area beyond universities could elucidate the negative impacts on conditions for data sharing, community culture, legitimate concerns and effort expectancy. Future policies might be able to address areas where the current activities thwart the data sharing practices.

About the authors

Khalid Ayuba Abdullahi was a PhD student of Department of Library & Information Science in the Faculty of Computer Science & Information Technology, Universiti Malaya. His research interests include information management, library automation and library anxiety. He is currently working as a lecturer at the Department of Library and Information Science, Faculty of Technology Education, Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, Nigeria. He can be contacted at ayubakhalid6@gmail.com.

A. Noorhidawati is an Associate Professor and currently the head of the Department of Library & Information Science in the Faculty of Computer Science & Information Technology, Universiti Malaya. She is also the program co-ordinator, Master of Library and Information Science (MLIS). She received her Ph.D. from the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK. Her research interests include digital library, digital literacy, information management, scholarly communication, and bibliometrics. She can be contacted at noorhidawati@um.edu.my.

References

Note: A link from the title is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Adam, I., & Usman, I. (2013). Resource sharing services in academic library services in Bauchi: the case of Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University and Muhammadu Wabi Libraries, Federal Polytechnic, Bauchi. Merit Research Journal of Education and Review, 1(5), 1-5. https://meritresearchjournals.org/er/content/2013/february/Adam%20and%20Usman.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3kndHby)

- Adelson, J. L., & McCoach, D. B. (2010). Measuring the mathematical attitudes of elementary students: the effects of a 4-point or 5-point Likert-type scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 70(5), 796-807. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164410366694

- Agosti, M., Ferro, N., & Silvello, G. (2018). Digital libraries: from digital resources to challenges in scientific data sharing and re-use. In S. Flesca, S. Greco, E. Masciari, & D. Saccà (Eds.), A comprehensive guide through the Italian database research over the last 25 years (pp. 27-41). Springer. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319618920

- Allen, C., & Mehler, D. M. (2019). Open science challenges, benefits and tips in early career and beyond . PLOS Biology, 17(5), e3000246. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000246 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20210826052427/https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pbio.3000246)

- Alter, G., & Gonzalez, R. (2018). Responsible practices for data sharing. American Psychologist, 73(2), 146. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000258

- Asai, A., Ohnishi, M., Nishigaki, E., Sekimoto, M., Fukuhara, S., & Fukui, T. (2002). Attitudes of the Japanese public and doctors towards use of archived information and samples without informed consent: Preliminary findings based on focus group interviews . BMC Medical Ethics, 3(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-3-1 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3sRVy9E)

- Avuglah, B. K., & Underwood, P. G. (2019). Research data management (RDM) capabilities at the University of Ghana, Legon. Library Philosophy and Practice, 1-18. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2258/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3DnWQhh)

- Awodoyin, A., Osisanwo, T., Adetoro, N., & Adeyemo, I. (2016). Knowledge sharing behaviour pattern analysis of academic librarians in Nigeria. Journal of Balkan Libraries Union, 4(1),12-19 https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2017.1329223

- Bailey, B., Benson, A. J., & Bruner, M. W. (2019). Investigating the organisational culture of CrossFit. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17(3), 197-211. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2017.1329223|

- Baker, K. S., & Miller and, F. (2016). Infrastructuring ecology: challenges in achieving data sharing. In J. Parker, N. Vermeulen, & B. Penders (Eds.), Collaboration in the new life sciences (pp. 133-160). Routledge.

- Ballantyne, A. (2019). Adjusting the focus: a public health ethics approach to data research. Bioethics, 33(3), 357-366. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12551

- Banks, G. C., Field, J. G., Oswald, F. L., O’Boyle, E. H., Landis, R. S., Rupp, D. E., & Rogelberg, S. G. (2019). Answers to 18 questions about open science practices. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(3), 257-270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-9547-8

- Barrios, J. A. (2013). The impact of mandated change on a hierarchical subculture: a mixed-methods study using the competing values framework. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Capella University, Minneapolis, Minnesota. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-impact-of-mandated-change-on-a-hierarchical-A-Barrios/71ffd1db1edd76054c97f8debf3b96c81ddc4bca

- Bezuidenhout, L. (2019). To share or not to share: incentivizing data sharing in life science communities. Developing World Bioethics, 19(1), 18-24. https://doi.org/10.1111/dewb.12183

- Bhatnagar N. (2018). Harnessing the power of big data in science. In A. Hassanien, M. Tolba, M. Elhoseny, & M. Mostafa, (Eds.). The International Conference on Advanced Machine Learning Technologies and Applications (AMLTA2018), Cairo, Egypt, 22-24 February (pp. 479-485). Springer. (Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol 723). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74690-6_47

- Bonàs-Guarch, S., Guindo-Martínez, M., Miguel-Escalada, I., Grarup, N., Sebastian, D., Rodriguez- Fos, E., González, S., Sánchez, F., Planas-Felix, M., Cortes-Sánchez, P., Timshel, P., Pers, T. H., Morgan, C. C., Moran, I., Atla, G., González, J.R. Puiggros, M., Martí, J., Andersson, E. A., … & Luan, J. (2018). Re-analysis of public genetic data reveals a rare X-chromosomal ariant associated with type 2 diabetes. Nature Communications, 9(1), article 321. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02380-9 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2WtKunm)

- Borgman, C. L. (2012). The conundrum of sharing research data. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(6), 1059-1078. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22634

- Borgman, C. L. (2018). Data sharing and reuse in interdisciplinary scientific collaborations: challenges of heterogeneous practice. Presented at The Pufendorf IAS Symposium on Interdisciplinarity, Lund University, Sweden. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6tb5718z (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3gG5TjY)

- Borgman, C. L., Wallis, J. C., & Enyedy, N. (2007). Little science confronts the data deluge: habitat ecology, embedded sensor networks, and digital libraries. International Journal on Digital Libraries, 7(1–2), 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00799-007-0022-9 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3gE2Fxw)

- Boulton, G., Rawlins, M., Vallance, P., & Walport, M. (2011). Science as a public enterprise: the case for open data. The Lancet, 377(9778), 1633-1635. https://doi.org.10.1016/so140-67369(11)60647-8 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3mD7bjv)

- Byrd, J. B., Greene, A. C., Prasad, D. V., Jiang, X., & Greene, C. S. (2020). Responsible, practical genomic data sharing that accelerates research. Nature Reviews Genetics, 21, 1-15.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-020-0257-5 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2Wz9jy9)

- Campbell, H. A., Micheli-Campbell, M. A., & Udyawer, V. (2019). Early career researchers embrace data sharing. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 34(2), 95-98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2018.11.010

- Cao, Q. H., Giyyarpuram, M., Farahbakhsh, R., & Crespi, N. (2017). Policy-based usage control for a trustworthy data sharing platform in smart cities. Future Generation Computer Systems. 107, 998-1010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2017.05.039

- Chatman, J. A., & Cha, S. E. (2003). Leading by leveraging culture. California Management Review, 45(4), 20-34. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166186

- Chawinga, W. D., & Zinn, S. (2019). Global perspectives of research data sharing: a systematic literature review. Library & Information Science Research. 41(2), 109-122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2019.04.004

- Cook-Deegan, R., Ankeny, R. A., & Maxson Jones, K. (2017). Sharing data to build a medical information commons: from Bermuda to the Global Alliance. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, 18, 389-415. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genom-083115-022515 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3sQHGwi)

- Cragin, M. H., Palmer, C. L., Carlson, J. R., & Witt, M. (2010). Data sharing, small science and institutional repositories. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 368(1926), 4023-4038. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2010.0165

- Creaser, C., Fry, J., Greenwood, H., Oppenheim, C., Probets, S., Spezi, V., & White, S. (2010). Authors’ awareness and attitudes toward open access repositories. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 16(S1), 145-161.https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2010.518851 OA (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2Wv2C0a)

- Dahrendorf, M., Hoffmann, T., Mittenbühler, M., Wiechert, S.-M., Sarafoglou, A., Matzke, D., & Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2019). Because it is the right thing to do: taking stock of the Peer Reviewers’ Openness Initiative. Journal of European Psychology Students, 11(1), 15-20. http://doi.org/10.5334/jeps.506 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3krLIrj)

- Eshel, N., Tian, J., Bukwich, M., & Uchida, N. (2016). Dopamine neurons share common response function for reward prediction error. Nature Neuroscience, 19(3), 479-486. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4239

- Fecher, B., Friesike, S., & Hebing, M. (2015). What drives academic data sharing? PLOS One, 10(2), e0118053. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118053 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2UQe7OQ)

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 382-388. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150980

- Foster, E. D., & Deardorff, A. (2017). Open science framework (OSF). Journal of the Medical Library Association, 105(2), 203-206. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2017.88 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2WuyilM)

- Gewin, V. (2016). Data sharing: an open mind on open data. Nature, 529(7584), 117-119. https://doi.org/10.1038/nj7584-117a (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3DlN5QN)

- Gilbert, J. A., Jansson, J. K., & Knight, R. (2014). The Earth Microbiome project: successes and aspirations. BMC Biology, 12(1), article 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-014-0069-1 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3jkArJS)

- Gregory, K., Cousijn, H., Groth, P., Scharnhorst, A. and Wyatt, S. (2018). Understanding data retrieval practices: a social informatics perspective. arXiv:1801.04971v1. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551519837182 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3jtpzK1)

- Hair, J., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & G. Kuppelwieser, V. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): an emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106-121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

- Hardwicke, T. E., Mathur, M. B., MacDonald, K., Nilsonne, G., Banks, G. C., Kidwell, M. C., Mohr, A. H., Clayton, E., Yoon, E. J., Tessler, M. H., Lenne, R. L., Altman, S., Long, B., & Frank, M. C. (2018). Data availability, reusability, and analytic reproducibility: evaluating the impact of a mandatory open data policy at the journal Cognition. Royal Society Open Science, 5(8), 180448. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.180448 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3DpQjmk)

- Hardwicke, T. E., Wallach, J. D., Kidwell, M. C., Bendixen, T., Crüwell, S., & Ioannidis, J. P. (2019). An empirical assessment of transparency and reproducibility-related research practices in the social sciences (2014–2017). Royal Society Open Science, 7(2), 190806. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.190806 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3gG4Ssf)

- Hate, K., Meherally, S., Shah More, N., Jayaraman, A., Bull, S., Parker, M., & Osrin, D. (2015). Sweat, skepticism, and uncharted territory: a qualitative study of opinions on data sharing among public health researchers and research participants in Mumbai, India. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 10(3), 239-250. https://doi.org/10.1177/1556264615592383 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3gCybMy)

- Hemminger, B. (2010). Scientific data repositories on the Web: An initial survey. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(10). https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21339 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3ynP5nO)

- Hirschfeld, G. (2012). Data sharing is harder to reward. Nature, 487(7407), 302. https://doi.org/10.1038/487302c (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3mEaBTm)

- Horai, H., Arita, M., Kanaya, S., Nihei, Y., Ikeda, T., Suwa, K., Ojima, Y., Tanaka, K., Tanaka, S., Aoshima, K., Oda, Y., Kakazu, Y., Kusano, M., Tohge, T., Matsuda, F., Sawada, Y., Hirai, M. Y., Nakanishi, H., Ikeda, K. … & Nishioka, T. (2010). MassBank: a public repository for sharing mass spectral data for life sciences. Journal of Mass Spectrometry, 45(7), 703-714. https://doi.org/10.1002/jms.1777 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2WvPrvG)

- Houtkoop, B. L., Chambers, C., Macleod, M., Bishop, D. V., Nichols, T. E., & Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2018). Data sharing in psychology: a survey on barriers and preconditions. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 1(1), 70-85. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245917751886 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2UW5r9Q)

- Howe, N., Giles, E., Newbury-Birch, D., & McColl, E. (2018). Systematic review of participants’ attitudes towards data sharing: a thematic synthesis. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 23(2), 123-133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819617751555.

- Hsu, C. L., & Lin, J. C. C. (2008). Acceptance of blog usage: The roles of technology acceptance, social influence and knowledge sharing motivation. Information and Management, 45(1), 65-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2007.11.001

- Hummel, P., Braun, M., & Dabrock, P. (2019). Data donations as exercises of sovereignty. In J. Krutzinna and L. Floridi (Eds.), The ethics of medical data donation (Philosophical Studies Series, 137; pp. 23-54). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04363-6_3

- Idang, G. E. (2015). African culture and values. Phronimon, 16(2), 97-111. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70550-3_6

- International Brain Laboratory, Bonacchi, N., Chapuis, G., Churchland, A., Harris, K. D., Hunter, M., Rossant, C., Sasaki, M. Shen, S. Steinmez, N. A., Walker, E. Y., Winter, O., & Wells, M. (2020). Data architecture for a large-scale neuroscience collaboration. bioRXiv preprint. https://doi.org/10.1101/827873 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3gE4LNU)

- Johnson, J. B., Reynolds, H. T., & Mycoff, J. D. (2019). Political science research methods. CQ Press.

- Jones, M. C., Cline, M., & Ryan, S. (2006). Exploring knowledge sharing in ERP implementation: an organizational culture framework. Decision Support Systems, 41(2), 411-434.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2004.06.017

- Kankanhalli, A., Tan, B. C., & Wei, K.-K. (2005). Contributing knowledge to electronic knowledge repositories: an empirical investigation. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 113-143.https://doi.org/10.2307/25148670

- Karczewski, K., & Francioli, L. (2017). The Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD). MacArthur Lab. http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org

- Kaye, J., Terry, S. F., Juengst, E., Coy, S., Harris, J. R., Chalmers, D., Dove, E. S., Budin- Ljøsne, I., Adebamowo, C., Ogbe, E., Bezuidenhout, L., Morrison, M., Minion, J. T., Murtagh, M. J., Minari, J., Teare, H., Isasi, R., Kato., K., Rial-Sebbag, E., … & Cambon-Thomsen, A. (2018). Including all voices in international data-sharing governance. Human Genomics, 12, article 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40246-018-0143-9

- Kenter, J. O., Bryce, R., Christie, M., Cooper, N., Hockley, N., Irvine, K. N., Fazey, I. Obrien, L., Orchard-Webb, J., Ravenscroft, N., Raymond, C. M., Reed, M. S., Tett, P., & Watson, V. (2016). Shared values and deliberative valuation: future directions. Ecosystem Services, 21, 358-371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2016.10.006

- Kerr, J., & Slocum, J. W. (2005). Managing corporate culture through reward systems. Academy of Management Perspectives, 19(4), 130-138.https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2005.19417915

- Kim, J. (2007). Motivating and impeding factors affecting faculty contribution to institutional repositories. Journal of Digital Information, 8(2). https://journals.tdl.org/jodi/index.php/jodi/article/view/193

- Kim, J. (2013). Data sharing and its implications for academic libraries. New Library World, 114(11/12), 494-506. https://doi.org/10.1108/NLW-06-2013-0051

- Kim, J., Lee, C., & Elias, T. (2015). Factors affecting information sharing in social networking sites amongst university students: application of the knowledge-sharing model to social networking sites. Online Information Review, 39(3), 290-309. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-01-2015-0022

- Kim, Y., & Adler, M. (2015). Social scientists’ data sharing behaviors: investigating the roles of individual motivations, institutional pressures, and data repositories. International Journal of Information Management, 35(4), 408-418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2015.04.007

- Kim, Y., & Stanton, J. M. (2012). Institutional and individual influences on scientists’ data sharing practices. Journal of Computational Science Education, 3(1), 47-56. https://doi.org/10.22369/issn.2153-4136/3/1/6

- Kim, Y., & Stanton, J. M. (2013). Institutional and individual influences on scientists' data sharing behaviors: a multilevel analysis. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 50(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1002/meet.14505001093

- Kim, Y., & Stanton, J. M. (2016). Institutional and individual factors affecting scientists' data‐sharing behaviors: a multilevel analysis. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67(4), 776-799.https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23424

- Kiran, M., Murphy, P., Monga, I., Dugan, J., & Baveja, S. S. (2015). Lambda architecture for cost-effective batch and speed big data processing. Paper presented at the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Big Data. https://doi.org/10.1109/BigData.2015.7364082

- Kling, R., & Spector, L. B., (2003). Rewards for scholarly communication. In D.L. Andersen (Ed.), Digital scholarship in the tenure, promotion, and review process (pp. 78-105). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315705170

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D.W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607-610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308

- Lee, J.-C., Shiue, Y.-C., & Chen, C.-Y. (2016). Examining the impacts of organizational culture and top management support of knowledge sharing on the success of software process improvement. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 462-474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.08.030

- Linek, S. B., Fecher, B., Friesike, S., & Hebing, M. (2017). Data sharing as social dilemma: Influence of the researcher’s personality. PLOS One, 12(8), e0183216. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183216 ( https://bit.ly/2XWWNsB)

- Little, J. M., Gaier, S., & Spoutz, D. (2018). The role of values, beliefs, and culture in student retention and success. In Critical assessment and strategies for increased student retention (pp. 54-72). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-2998-9.ch004

- McGuire, A. L., Hamilton, J. A., Lunstroth, R., McCullough, L. B., & Goldman, A. (2008). DNA data sharing: research participants' perspectives. Genetics in Medicine, 10(1), 46-53. https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e31815f1e00 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3BcCA0i)

- McKiernan, E. C., Bourne, P. E., Brown, C. T., Buck, S., Kenall, A., Lin, J., Mcdougall, D., Nosek, B. A., Ram, K., Soderberg, C. K., Spies, J. R., Thaney, K., Updegrove, A., Woo, K. H., & Yarkoni, T. (2016). Point of view: how open science helps researchers succeed. eLife, 5, 1-15, e16800. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.16800 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3gCzg74)

- MacMillan, D. (2014). Data sharing and discovery: what librarians need to know. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(5), 541-549.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.06.011

- Mannheimer, S., Pienta, A., Kirilova, D., Elman, C., & Wutich, A. (2019). Qualitative data sharing: data repositories and academic libraries as key partners in addressing challenges. American Behavioral Scientist, 63(5), 643-664. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218784991

- Michener, W. K. (2015). Ecological data sharing. Ecological Informatics, 29, 33-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2015.06.010 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3gBMyAu)

- Mons, B., Neylon, C., Velterop, J., Dumontier, M., da Silva Santos, L. O. B., & Wilkinson, M. D. (2017). Cloudy, increasingly FAIR: revisiting the FAIR Data guiding principles for the European Open Science Cloud. Information Services & Use, 37(1), 49-56.https://doi.org/10.3233/ISU-170824

- Mooi, E., Sarstedt, M., & Mooi-Reci, I. (2018). Market research: the process, data and methods using Stata. Springer Singapore. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9789811052170

- Morey, R. D., Chambers, C. D., Etchells, P. J., Harris, C. R., Hoekstra, R., Lakens, D., Lewandowsky, S., Morey, C. C., Newman, D. P., Schönbrodt, F. D., Vanpaemel, W., Wagenmakers, E., & Zwaan, R. A. (2016). The Peer Reviewers' Openness Initiative: incentivizing open research practices through peer review. Royal Society Open Science, 3(1), 150547. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150547

- Moss, E., Cave, C., & Lyle, J. (2015). Sharing and citing research data: a repository's perspective. In H.K. Jayasuriya, H. K., and K.A. Ritcheske (Eds.), Big data, big challenges in evidence-based policy making (chapter 4). Western Academic Publishing. https://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/115490

- Munafò, M. R., Nosek, B. A., Bishop, D. V., Button, K. S., Chambers, C. D., du Sert, N. P., Simonsohn, U., Wagenmaker, E., Ware, J. J., & Ioannidis, J. P. (2017). A manifesto for reproducible science. Nature Human Behavior, 1, article 21. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-016-0021 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3yhtWvP)

- Naudet, F., Sakarovitch, C., Janiaud, P., Cristea, I., Fanelli, D., Moher, D., & Ioannidis, J. P. (2018). Data sharing and reanalysis of randomized controlled trials in leading biomedical journals with a full data sharing policy: survey of studies published in The BMJ and PLOS Medicine. BMJ, 360, k400. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k400 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/38jc4pS)

- Nosek, B. A., Alter, G., Banks, G. C., Borsboom, D., Bowman, S. D., Breckler, S. J., Buck, S., Chambers, C. D., Chin, G., Christensen, G., Contestabile, M., Defoe, A., Eich, E., Freese, J., Glennerster, R., Goroff, D., Green, D. P., Hesse, B., Humphreys, M. … & Yarkoni, T. (2015). Promoting an open research culture. Science, 348(6242), 1422-1425. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab2374

- Odigwe, F. N., Bassey, B. A., & Owan, V. J. (2020). Data management practices and educational research effectiveness of university lecturers in South-South Nigeria. Journal of Educational and Social Research (JESR), 10(3), 24-34. https://doi.org/10.36941/jesr-2020-0042 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3zpazlR)

- Oloruntoba, R., Hossain, G. F., & Wagner, B. (2019). Theory in humanitarian operations research. Annals of Operations Research, 283(1-2), 543-560.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-016-2378-y

- Pearce, N., & Smith, A. H. (2011). Data sharing: not as simple as it seems. Environmental Health, 10(1), article 107. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-10-107 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3zq3G3I)

- Piwowar, H. A. (2011). Who shares? Who doesn't? Factors associated with openly archiving raw research data. PLOS One, 6(7), e18657. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0018657 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3gFnnwT)

- Piwowar, H. A., & Chapman, W. W. (2010). Public sharing of research datasets: a pilot study of associations. Journal of Informetrics, 4(2), 148-156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2009.11.010

- Polanin, J. R., & Terzian, M. (2019). A data-sharing agreement helps to increase researchers’ willingness to share primary data: results from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 106, 60-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.10.006

- Reichman, O. J., Jones, M. B., & Schildhauer, M. P. (2011). Challenges and opportunities of open data in ecology. Science, 331(6018), 703-705. https://doi: 10.1126/science.1197962(Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3zo4lCN)

- Roberts, E., Anderson, B. A., Skerratt, S., & Farrington, J. (2017). A review of the rural-digital policy agenda from a community resilience perspective. Journal of Rural Studies, 54, 372-385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.03.001 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3DmGTYN)

- Roche, D. G., Lanfear, R., Binning, S. A., Haff, T. M., Schwanz, L. E., Cain, K. E., Kokko, H., Jennions, M. D., & Kruuk, L. E. (2014). Troubleshooting public data archiving: suggestions to increase participation. PLOS Biology, 12(1), e1001779. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001779 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3sRIl0x)

- Ross, M. W., Iguchi, M. Y., & Panicker, S. (2018). Ethical aspects of data sharing and research participant protections. American Psychologist, 73(2), 138-145. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000240

- Sangiovanni-Vincentelli, A. (2007). Quo vadis, SLD? Reasoning about the trends and challenges of system level design. Proceedings of the IEEE, 95(3), 467-506.https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2006

- Sayogo, D. S., & Pardo, T. A. (2013). Exploring the determinants of scientific data sharing: Understanding the motivation to publish research data. Government Information Quarterly, 30, S19-S31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2012.06.011

- Schein, E. H. (1985). Organizational culture and leadership. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Schein, E. H. (1990). Organizational culture (Vol. 45): American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.45.2.109

- Shah, N., Coathup, V., Teare, H., Forgive, I., Giordano, G.N., Hansen, T. H., Groeneveld, L., Hudson, M., Pearson, E., Ruetten, H., & Kay, J. (2019). Motivations for data sharing—views of research participants from four European countries: A DIRECT study. European Journal of Human Genetics 27, 721–729. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0344-2 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3yidMSM)

- Shen, Y. (2016). Research data sharing and reuse practices of academic faculty researchers: a study of the Virginia Tech data landscape. International Journal of Digital Curation, 10(2), 157-175.https://doi.org/10.2218/ijdc.v10i2.359

- Spallek, H., Weinberg, S., Manz, M., Nanayakkara, S., Zhou, X., & Johnson, L. (2019). Perceptions and attitudes toward data sharing among dental researchers. JDR Clinical & Translational Research, 4(1), 68-75. https://doi.org/10.1177/2380084418790451 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3ztMkms)

- Taichman, D. B., Backus, J., Baethge, C., Bauchner, H., De Leeuw, P. W., Drazen, J. M., Fletcher, J., Frizelle, F. A., Groves, T., Haileamlak, A., James, A., Laine, C., Peiperl, L., Pinborg, A., Sahni, P., & Wu, S. (2016). Sharing clinical trial data: a proposal from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. New England Journal of Medicine, 374, 384-386. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe1515172https://bit.ly/2WytdZG (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2WytdZG)

- Tannenbaum, S., Ross, J. S., Krumholz, H. M., Desai, N. R., Ritchie, J. D., Lehman, R., Gamble, G. M., Bachand, J., Schroter, S., Groves, T., & Gross, C. P. (2018). Early experiences with journal data sharing policies: a survey of published clinical trial investigators. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(8), 586-588. https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-0723

- Tenopir, C., Allard, S., Douglass, K., Aydinoglu, A. U., Wu, L., Read, E., Manoff, M., & Frame, M. (2011). Data sharing by scientists: practices and perceptions. PLOS One, 6(6), e21101. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0021101 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3gEr8CT )

- Tenopir, C., Dalton, E. D., Allard, S., Frame, M., Pjesivac, I., Birch, B., Pollock, D., & Dorsett, K. (2015). Changes in data sharing and data reuse practices and perceptions among scientists worldwide. PLOS One, 10(8), e0134826. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0134826 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3mM7SqK)

- Tong, C., Tak, W. I. W., & Wong, A. (2015). The impact of knowledge sharing on the relationship between organizational culture and job satisfaction: the perception of information communication and technology (ICT) practitioners in Hong Kong. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 3(1), 9-37. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijhrs.v3i1.3112

- Ünal, Y., Chowdhury, G., Kurbanoğlu, K., Boustany J., & Walton G. (2019). Research data management and data sharing behaviour of university researchers In Proceedings of ISIC, The Information Behaviour Conference, Krakow, Poland, 9-11 October: Part 2. Information Research, 24(1), paper isic1818. http://InformationR.net/ir/24-1/isic2018/isic1818.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/74U6bBMqk)

- Vanneste, D., Vermeulen, B., & Declercq, A. (2013). Healthcare professionals’ acceptance of BelRAI, a web-based system enabling person-centred recording and data sharing across care settings with interRAI instruments: a UTAUT analysis. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 13(1), article 129. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-13-129 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3jnsraZ)

- Vicente-Sáez, R., & Martínez-Fuentes, C. (2018). Open science now: a systematic literature review for an integrated definition. Journal of Business Research, 88, 428-436.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.043

- Villanueva, A. G., Cook-Deegan, R., Koenig, B. A., Deverka, P. A., Versalovic, E., McGuire, A. L., & Majumder, M. A. (2019). Characterizing the biomedical data-sharing landscape. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 47(1), 21-30.https://doi: 10.1177/1073110519840481 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2WvzF3E)

- Visscher, K. M., & Weissman, D. H. (2011). Would the field of cognitive neuroscience be advanced by sharing functional MRI data? BMC Medicine, 9(1), article 34.https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-9-34 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2XYzRt3)