Information behaviour of HIV patients during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Republic of Georgia

Besiki Stvilia, Ketevan Stvilia, and Izoleta Bodokia.

Introduction. In this study, we examined the information behaviour of people living with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Republic of Georgia. The research took place before COVID-19 vaccines were available.

Methods. We conducted semi-structured interviews with fifteen participants.

Analysis. The content of interviews was analysed for a priori and emergent themes and iteratively categorized. In addition, we used k-means clustering to identify the types of information users.

Results. People living with HIV used government AIDS and CDC centres, primary care physicians, television, websites and their personal networks as their information sources. Some participants reported that receiving COVID-19 information increased their stress levels. Threats to their privacy and the fear of disclosing their HIV-positive status were identified as some of the barriers to seeking and sharing information they encountered. Three types of information users were identified: Netizens, Traditionalists and Lurkers.

Conclusions. The findings of this study can be used to help design effective health communication campaigns and information systems for people living with HIV in general and to provide COVID-19 information in particular.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper910

Introduction

The current evidence for people living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is limited regarding whether the infection imparts a higher risk of acquiring a severe case of COVID-19 (Altuntas Aydin et al., 2020; Härter et al., 2020). An analysis of the health outcomes of 12,987 people with COVID-19 in Western Cape, South Africa, found that people living with HIV and people with past or current tuberculosis infections had a greater risk of dying of COVID-19 (Davies, 2020). In contrast, some studies suggest that immunosuppression and low CD4 cell counts and some antiretroviral medicines (such as lopinavir and ritonavir [LPV/r]) might protect HIV-infected individuals from developing the cytokine storm observed in patients with COVID-19 that leads to severe complications from the disease (Fung and Babik, 2021). Considering such contradictory findings, implementation of COVID-19 prevention measures, including ensuring access of people living with HIV to high-quality, relevant information about COVID-19, becomes critically important.

The first cases of COVID-19 in Georgia were confirmed on February 26, 2020. At the beginning, the Georgian government was very proactive in taking measures to prevent COVID-19. It had quickly implemented targeted lockdowns and successfully controlled the spread of the virus until the early autumn 2020. In July 1, 2020, the total number of infected people was only 995, with 857 recoveries and fifteen deaths. Within the overall COVID-19 response, effective risk-reduction communication was initiated by developing clear messages related to COVID-19 symptom recognition, first contact, appropriate use of health services, financial access and social protection measures related to COVID-19 (Georgia. Government, 2020). In addition to these measures, the National AIDS Centre and HIV/AIDS Patients’ Support Foundation initiated specific COVID-19 risk-reduction communication for people living with HIV through direct proactive and reactive telephone communication with patients.

Later, in autumn 2020, however, the government relaxed its COVID-19 restrictions. It opened the country for local tourism and held parliamentary elections at the end of October 2020. That policy change quickly led to an explosion in the number of COVID-19 cases and COVID-19-related deaths in the country. As of December 16, 2020, Georgia, with a total population of 3.7 million people, was among the forty countries with the highest death ratios per 100,000 persons.

It is well known that, in general, people living with HIV are an underserved population. Members of this group are reluctant to seek medical advice and care because of the considerable stigma related to HIV, except in cases of a clear emergency (Chesney and Smith, 1999; Chin and Kroesen, 1999; Churcher, 2013; Smart and Wegner, 2000). People living with HIV in Georgia are not exempt from such behavioural patterns driven by the strong stigma and homophobia (Mestvirishvili et al., 2017; Vardiashvili, 2018). Furthermore, the Internet and social media platforms help spread accurate information as well as misinformation, disinformation and conspiracy theories about COVID-19 (Goodman and Carmichael, 2020). It is important to examine the information needs and activities of people living with HIV during the pandemic to fine-tune health communication campaigns and information services and make them more effective. Finally, there is a dearth of research on the information behaviour of people living with HIV in the South Caucasus region in general and during a health epidemic in particular. We have contributed to addressing these needs by interviewing people living with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic in Georgia. The study took place before COVID-19 vaccines were available in the country. In this paper we investigate how the context of global pandemic and stigma shaped the health information needs and behaviour of HIV patients living in a developing country. By interpreting the study’s findings through the literature, we examine how the population’s behaviour is unique or similar in relation to findings of prior studies, and the ways our examination could inform the design of health information resources and services for the population.

Related research

An information need is a realisation that one’s knowledge is insufficient to satisfy a goal that one holds. Information seeking, on the other hand, is the activity of obtaining a response to an information need or perceived gap in one’s knowledge (Case, 2006). As with any other activity, patients’ information-seeking activity can be shaped by multiple and often competing needs and motivations (Kaptelinin, 2005). Furthermore, patients’ information needs and related information behaviour are mediated by their personal psychological, affective, and cognitive states and the context of the activity (Bawden, 2006; Wilson, 1997). Misalignments among a person’s characteristics and states, other components of the activity, and the activity’s context can be conceptualised as barriers to and contradictions (Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2012, Wilson, 1997). One of the main motivations for individuals seeking health information is the perceived risk of catching a disease. To act on a motivation, however, the motivation needs to be strong enough, and the person needs to be capable of completing the actions of the activity (Kaptelenin, 2005). Indeed, the literature shows that users’ perceived self-efficacy can shape their information seeking and coping strategies (Wilson, 1997). Eastin and Guinsler (2006) found that patients with high perceived self-efficacy for obtaining and understanding health information might rely less on doctors’ advice in their health-related decision making. Rimal (2001) utilized perceived risk and self-efficacy as organising facets to define a four-part typology of information users: responsive, proactive, avoidant and indifferent. Furthermore, a person’s motivation for seeking high-quality information may compete with the person’s desire to feel competent. Individuals might intentionally avoid or ignore information that conflicts with their existing beliefs and previous evaluations regarding the quality of information items such as news (Allcott and Gentzkow, 2017). Alternatively, the feeling of a cognitive dissonance or conflict can motivate users to actively seek information that confirms their beliefs and convictions on a particular issue or event (Wilson, 1997).

Another factor that may influence whether a person initiates an activity is the perceived cost. Patients’ information-seeking behaviour can be affected not only by the material costs of obtaining information, but also by its psychological and emotional costs. Individuals may avoid searching for health information, using it or both because of the psychological cost of becoming aware of or making decisions about and being held responsible for their health problems (Brasher et al., 2000; Johnson, 2014; Zuuren and Wolfs, 1991, as cited in Wilson, 1997). Information behaviour can be also theorised using stress and coping theory. In particular, stress and coping theory suggests that the degree of a person’s intolerance to stressful situations and uncertainty, and the degree of the person’s cognitive avoidance to problem solving can be used to conceptualise different information behaviour and user types (Wilson, 1997).

To enable users’ information seeking, sensemaking, and evaluation, users need to have access to information resources and their metadata, including information quality and credibility cues; what Wilson (1997) categorized as source characteristics. Information quality is generally defined as the ‘fitness for use’ of the information. The quality of information affects the quality of decisions based on the information and the outcomes of activities that use the information (Stvilia et al., 2007). If an individual does not have sufficient subject matter knowledge and training to evaluate the information directly, the individual may rely on different cues and heuristics to assess the quality of the information indirectly. For instance, one of the most frequently used heuristics used by individuals in their indirect evaluation of online information quality has been the degree of corroboration of the information among multiple sources (Stvilia et al., 2009). However, to be successful in evaluating the information quality indirectly, users need to possess sufficient information literacy. They need to be able to recognise and use those equality cues in their heuristic evaluation (Choi and Stvilia, 2015; Stvilia et al., 2009). Furthermore, patients may exhibit satisficing behaviour (Simon, 1956) and may use information sources that are satisfactory or familiar to meet their information needs instead of conducting thorough research (Sundar et al., 2011). Finally, the level of education may affect the use of the Internet in health information seeking. It was found that HIV patients without a high school education used the Internet for health information significantly more often than those with a high school diploma. This could potentially make the former group more vulnerable to misinformation (Calvert et al., 2013).

Another source characteristic (Wilson, 1997) that may moderate HIV patients’ information behaviour is the confidentiality of an information channel. The literature shows that the preferred sources of health information for people living with HIV are physicians and other fellow patients (Hogan and Palmer, 2005; Veinot et al., 2006). The fear of marginalization and stigma might affect how HIV patients choose their sources of health information. They might avoid using information sources that they perceive as unsafe to their privacy and preserving the confidentiality of their health condition (Veinot et al., 2006). Furthermore, meeting the emotional and affective needs of health patients has been identified as critical to patients seeking or using health information or taking up a treatment (Brashers et al., 2000; Case, 2006; Veinot et al., 2006). HIV patient communities and community organizations serve as sources of information, places for emotional support and coping with stress (Hogan and Palmer, 2005; Reeves et al., 2001; Veinot et al., 2006). Entering a stigmatised information ecosystem can be particularly challenging to newcomers who might not be knowledgeable of or do not have access to specialized community resources and information channels (Lingel and Boyd, 2013).

Problem statement and research questions

People living with HIV could be at higher risk of contracting severe COVID-19 illness because they have compromised immune systems. They are also often members of marginalized and stigmatised populations, which may affect their access to quality health information and services. Because the Internet and social media platforms help spread accurate information as well as misinformation, disinformation and conspiracy theories about COVID-19, it is important to understand how people living with HIV obtain and evaluate information during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although the health information-seeking activity of people living with HIV has been studied extensively, research is still lacking on the information behaviour of people living with HIV in developing countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. To achieve the public health objective of high-quality, relevant information about COVID-19 reaching people living with HIV, it is critical to investigate how the context of COVID-19 pandemic has affected the information needs and behaviour of people living with HIV.

To gain an initial understanding of these issues, we interviewed HIV patients living in Georgia during the COVID 19 pandemic. In his general model of information behaviour, Wilson (1997) conceptualised the mediation of users’ information needs and behaviour by their context. In addition, Stvilia et al.’s (2009) model of information quality specified the sets of quality criteria and cues consumers might use in their indirect evaluation of the quality and credibility of health information. Guided by these two models, we examined the following research questions:

- What are the COVID-19-related information needs of people living with HIV?

- What sources do they use to obtain that information and why?

- How do people living with HIV evaluate the quality of information?

- What information do people living with HIV share and why?

Methods

To address the research questions listed above, we used semi-structured interviews. A literature analysis was used to identify initial themes and a questionnaire that was developed in a previous study of consumers’ evaluation of online health information was adapted to construct the interview protocol (Stvilia et al., 2009). We used a list from the HIV/AIDS Patients’ Support Foundation to recruit the study participants. Since the Foundation shared only the names and phone numbers of potential participants, the study used a convenience sampling approach. We recruited and interviewed participants one by one and discontinued the recruitment when we reached a saturation point - that is, when additional interviews did not produce new emergent themes or topics (Glaser and Strauss, 1967).

Before participants were interviewed, we obtained their informed consent. The informed consent form was approved by the human subjects committees of the National Center for Disease Control and Public Health and Florida State University (IRB00002150). The informed consent form provided information about the project, including information about potential risks associated with their participation in data collection. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the sample.

| ID | Sex | Age | Educational attainment | Year of HIV diagnosis | Current residence | User Group Name (Number) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 49 | Bachelor's degree | 2015 | Tbilisi | Netizens(1) |

| 2 | F | 47 | High school graduate | 2012 | Tbilisi | Netizens(1) |

| 3 | F | 55 | Bachelor's degree | 2000 | Batumi | Lurkers(3) |

| 4 | F | 45 | Bachelor's degree | 2015 | Batumi | Netizens(1) |

| 5 | F | 36 | Bachelor's degree | 2007 | Tbilisi | Lurkers(3) |

| 6 | F | 47 | Bachelor's degree | 2015 | Tbilisi | Lurkers(3) |

| 7 | M | 36 | Bachelor's degree | 2018 | Tbilisi | Lurkers(3) |

| 8 | M | 30 | Bachelor's degree | 2013 | Tbilisi | Lurkers(3) |

| 9 | M | 42 | High school graduate | 2015 | Mtskheta | Traditionalists(2) |

| 10 | M | 42 | Bachelor's degree | 2002 | Kutaisi | Traditionalists(2) |

| 11 | M | 27 | Bachelor's degree | 2017 | Tbilisi | Netizens(1) |

| 12 | F | 53 | Bachelor's degree | 2009 | Tbilisi | Netizens(1) |

| 13 | F | 53 | Bachelor's degree | 2006 | Kutaisi | Traditionalists(2) |

| 14 | F | 48 | Bachelor's degree | 2007 | Zugdidi | Traditionalists(2) |

| 15 | M | 36 | Bachelor's degree | 2018 | Tbilisi | Lurkers(3) |

The second author interviewed fifteen participants in May and June 2020 (see Table 1). Thus, we collected data for this research before COVID-19 vaccines were available. The interviews were conducted by phone in Georgian and recorded using the phone recorder application from Appliqato. After completing an interview, each participant received a $15 honorarium in the form of a Western Union money transfer. The average length of the interviews was fifteen minutes. Two authors separately analysed the content of the transcribed interview recordings for both a priori themes defined by the research questions for the study and themes that emerged from the data. Next, they compared their lists of codes, aggregated the lists and mapped them. To enhance the reliability of the content analysis, they used the coding schema resulting from the first round of the content analysis to recode two interviews (i.e., approximately 10% of the data). The authors discussed and resolved the code assignments on which they disagreed, updated the coding schema and then recoded the complete data set.

Classification and categorization are essential general research methods of analysis and knowledge creation in all disciplines, including in the social sciences. Grouping items and activities according to their similarity or other relationships can help identify and define new concepts, uncover hidden, latent characteristics of the phenomena, reduce data complexity and facilitate sense making and communicate the findings of research analyses effectively (Bailey, 1994).

We used k-means clustering (Manning et al., 2008) to identify the types of information users in the community of people living with HIV for this study. In particular, we used participants’ responses to questions regarding what sources they used for health information and how often they used them, how they checked the quality of information and whether they shared information with others. In particular, terms such as never, rarely, sometimes, often and all the time found in participants’ responses to the second research question were mapped to a five-point ordinal scale to measure the level of use of the three types of information sources: (1) the Internet and social media, (2) physicians and (3) television. A similar mapping scheme was used to quantify participants’ degree of information sharing. Finally, we counted the number of cues each participant reported using to assess the quality of information. For that purpose, we adapted a set of quality and credibility cues from a prior study in which we examined how users evaluated the quality of health websites (Stvilia et al., 2009).

In particular, we used ten binary-response (i.e., yes or no) questions to assess how much effort participants spent on evaluating the quality of information. The questions were based on the following ten cues: (1) who runs or owns the site; (2) the presence of attributions for the information; (3) the qualifications of the author(s) of the information; (4) the presence of an established internal or external process for quality review of the information; (5) the date of information creation or an update; (6) whether the information was based on advertising; (7) whether the site collected personal information; (8) the presence of a policy specifying how the site handles users’ personal information; (9) whether the site links to sites, blogs or social media posts that do not meet certain quality criteria; and (10) whether multiple online sources report the same information.

Each participant’s responses to these questions were counted, and the counts were normalized and mapped to the five-point scale. For instance, if a participant reported examining online information for only four cues out of the ten, then we assigned the participant to Level 2 of the five-point scale for the propensity of checking the quality of information. Because the data comprised five dimensions with five levels each, manual categorization and typology building were not feasible. Hence, we had to apply a computer-based cluster analysis to the data (Bailey, 1994) using the k-means cluster analysis module of IBM SPSS software (IBM Inc., 2017). The Elbow method (Manning et al., 2008) was applied to the data set to determine the optimal number of clusters.

Results

COVID-19-related information needs of people living with HIV

We asked participants to describe a recent situation in which they sought COVID-19 related information. Most of the participants reported that they looked for information to determine whether they belonged to a group at high risk for COVID-19. They were also interested in general information about COVID-19, such as what causes the disease and its symptoms, the means of transmission, prevention strategies, treatment options, quarantine and self-isolation recommendations and lockdown rules. Participants also mentioned searching for stress relief and management guidance. Many of them reported that they found the pandemic and its coverage in the media very stressful:

At the beginning of the pandemic, I was closely following information on TV and social media, but later I was stressed and anxious and trying to avoid COVID-19-related information... I was looking for information on stress management and relief, and I found three different people offering online recommendations for stress management: a Georgian, a Russian and an Indian guru. I have been following these sites since then. (S6)

Sources of information

We also asked participants what sources they used to obtain COVID-19 related information and why. To meet their information needs, participants used different sources: social media, the Web, distance and on-site trainings organised by the HIV/AIDS Patients’ Support Foundation and National AIDS Centre, television, primary care physicians and physicians at the National AIDS Centre. Most of the participants reported that they used and trusted government websites more than other sites. One participant mentioned learning about COVID-19-related websites at the training provided by the HIV/AIDS Patients’ Support Foundation and National AIDS Centre. It is important to note that most of the participants spoke more than one language. Hence, they used sites and information from different countries and in different languages, including Georgian, Russian and English language sites:

I am following the well-known information sources on the Internet such as BBC, CNN and the WHO site. I was looking for information also in Georgian. . . . At the beginning, I couldn’t locate information on COVID–HIV co-infection. There were sites promoting ARV [antiretroviral] medicines for COVID-19 treatment. Follow-up studies did not support this information, though. UNAIDS provided information on risks for HIV-positive people. People on social media also were sharing some information. I didn’t contact my physician as I was fully following recommendations and isolation rules. (S11)

Although most of the participants praised the AIDS centre and HIV/AIDS Patients’ Support Foundation for proactively disseminating COVID-19-related information to people living with HIV, some of them reported that they did their own research as well to gain a better understanding of the disease and how to protect themselves:

I’m reading various sources and articles on the Internet and trying to investigate the subject in depth. (S1)

A few of them avoided using social media and the Web for COVID-19-related information altogether or used the National AIDS Centre and National Centre for Disease Control and Public Health sites only:

I didn’t want to get controversial information that would make me nervous and frustrated. Therefore, I was listening to physicians only. (S13)

As with many other countries, the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown caused a shutdown of the Georgian economy. Some people living with HIV ended up out of work. Hence, they might have had more time to be active on social media while having less access to their primary care physicians and physicians at the National AIDS Centre. Many of those physicians were called on to fight the pandemic:

I am not active on social media. During COVID, I was not working and I could use social media, but I was still getting information on COVID from TV. (S15)

The COVID-19 pandemic affected HIV participants’ access to high-quality health information. The analysis revealed that participants had different levels of access to information based on where they lived or were located during the government-imposed COVID-19 travel restrictions. The restrictions interfered with their everyday information-seeking patterns. For instance, participants who got stranded in or moved to rural areas during the pandemic might not have had access to a broadband Internet connection:

During COVID-19, I had limited access to the Internet. I was in a village. So my primary source of information was TV and my neighbours, who usually were bringing terrible fake news. (S5)

Another participant lamented that she could not attend face-to-face workshops or individual consultations organised by the HIV/AIDS Patients’ Support Foundation or the National AIDS Centre because of the COVID-19 restrictions:

Before the actual spread of COVID-19 in Georgia, I received a phone call from the HAPS [HIV/AIDS Patients’ Support Foundation] with an offer to come to the office to get detailed instructions, but I couldn’t go. I tried to search on the Internet for information on COVID-19 and HIV. (S2)

Participants noted that different media focused on different aspects of COVID-19 and provided different levels of detail on the virus. According to these participants, television coverage of the disease was mostly centred on the information needs of the general audience. It did not report on the COVID-19 risks for patients with specific chronic diseases, such as HIV or AIDS.

Furthermore, because people living with HIV were reluctant to disclose they had a chronic condition because of the associated stigma, they might have found it challenging to self-isolate in villages where people lived in more close-knit communities, and the level of social interaction was much higher than in the urban areas of the country. One participant revealed that this inability to self-isolate had resulted in receiving unsolicited rumours and misinformation about COVID-19 from people she had to interact with:

At the beginning of the pandemic, I was interested in whether people living with HIV had an increased risk for this disease. Nobody provided this information, but I saw that HIV wasn’t listed among the high-risk chronic conditions for COVID-19. I was hearing a lot of myths about this disease. As my relatives still wanted to visit us in the village, it was very difficult to get self-isolated. (S5)

Most participants felt that they could obtain the information they needed. Participants also commented on the negative emotional toll brought on them by coverage of the disease on television and discussions on social media.

There were people saying that ‘if something happens to me, then I will follow the recommendation’. It was a person who wanted to attend the Easter service despite the lockdown rules. If she does not care about her health, we do. We want to live. (S1)

Information quality

We asked participants whether they felt that they had found good information. Fourteen out of fifteen participants reported that they were able to find good information to satisfy their COVID-19-related information needs. One participant disclosed that he was unable to find reliable information on HIV-COVID co-infection risks. Another participant reflected that COVID-19 was a new disease and that our knowledge of the disease was still evolving. Hence, she did not expect the COVID-19-related information disseminated by the government and health service providers to be 100% accurate and reliable.

When asked what made them feel that they had found useful, high-quality information, participants referenced the following virtues or dimensions of information quality: consistency, completeness, accuracy, reliability, clarity of presentation and ease of understanding. When asked how they recognised when the information was not good, participants mentioned content characteristics, such as an inconsistent, insensitive, frightening or stressful presentation.

In addition, participants reported the use of several heuristics. One participant used the level of agreement among multiple sources of information to evaluate the information reliability. Previous experience with a source and the credentials and reputation of that source were the other signals participants used to assess the quality of information indirectly. In particular, participants mentioned not trusting the Facebook accounts and websites they spotted because they had spread misinformation and conspiracy theories in the past. Another negative credibility signal or cue to participants was when sites changed their position on a particular issue or contradicted their previous recommendations. One participant noted that if the site published contradictory information about COVID-19, she would lose trust:

I had a case when I was looking for information, and if the physician changed her recommendations for the disease, I trusted those pages less. I received information on one specific medicine, Chloroquine, saying that it was useful for prevention of COVID. However, I didn’t buy this drug as I fully trust Dr. [X] and Dr. [Y], who said that this medicine has side effects and shouldn’t be used for prevention. (S9)

Another participant revealed that she used her personal network not only for obtaining health information but also for checking its accuracy and reliability.

In addition to inquiring about how they evaluate the quality and credibility of online health information in general, we asked participants whether they used specific quality cues in their evaluation. For that purpose, we adapted the set of cues from a prior study that examined how users evaluated the quality of health websites (Stvilia et al., 2009). When asked whether they checked who managed or owned a particular online resource, only half reported that they did. Only one participant reported that he checked the authorship of online information. He went even further and examined authors’ previous publications or posts and compared them with the publications and posts of other authors to assess the credibility of the information. Participants indicated that they did not examine whether the site provided an attribution for the information, nor did they check whether the site they used had an established internal or external quality review process for the information. They also did not examine whether the information was based on advertising to sell products. Participants did check, though, when the information was created or updated. Most of the participants stated that they minded if the site required registration and requested their personal information. They said that they avoided those kinds of sites unless the value they assigned to the information justified the risk or the site was an e-commerce site they had to use to perform specific transactions (e.g., banking). It is interesting to note that participants did not check how the sites handled their personal information.

Information sharing

When asked about what information they shared, participants were divided. Some of them shared general information but not health-related information because of privacy concerns and for fear that their health condition as people living with HIV could be inadvertently disclosed to outsiders. One participant explained her concerns as follows:

I hide my status; only one family member is aware, my sister... Therefore, I don’t share anything. I am trying to be less visible. If I write something, somebody may say why I am interested in such topics. (S15)

Participants revealed some of the strategies they used to share health-related information while protecting their privacy. One participant noted that she shared health-related information face-to-face only because she felt that sharing information online was unsafe. Another participant revealed that she shared health information with close friends and other patients by using private messages, not public posts. Privacy concerns might likewise have led people living with HIV not to use sites that required registration. One participant stated that he used a fake account and a proxy or relay e-mail service to obfuscate his identity when using such sites and applications.

Lack of expertise was another reason some participants did not share information. They expressed concerns about the accuracy of online information available on the Web and social media in relation to their ability to determine whether the information was safe to share:

I am careful, I am not a physician, and even if I like health information, I am not sure that it is correct. [Hence], I wouldn’t share. (S13)

Participants shared information that they found interesting and useful and that they believed to be accurate. Two participants also revealed that if they spotted fake news or a big lie on social media, they would comment and warn others about it.

Most of them indicated that they shared information only with their friends and other people living with HIV. The main motivations for sharing were to inform other people, raise collective awareness, protect people from damage and harm and help fellow individuals living with HIV:

I share information about different diseases on social media. Our PLWH [people living with HIV] community is very close. We are like a family, and we always share news and we support each other. (S8).

Information user types

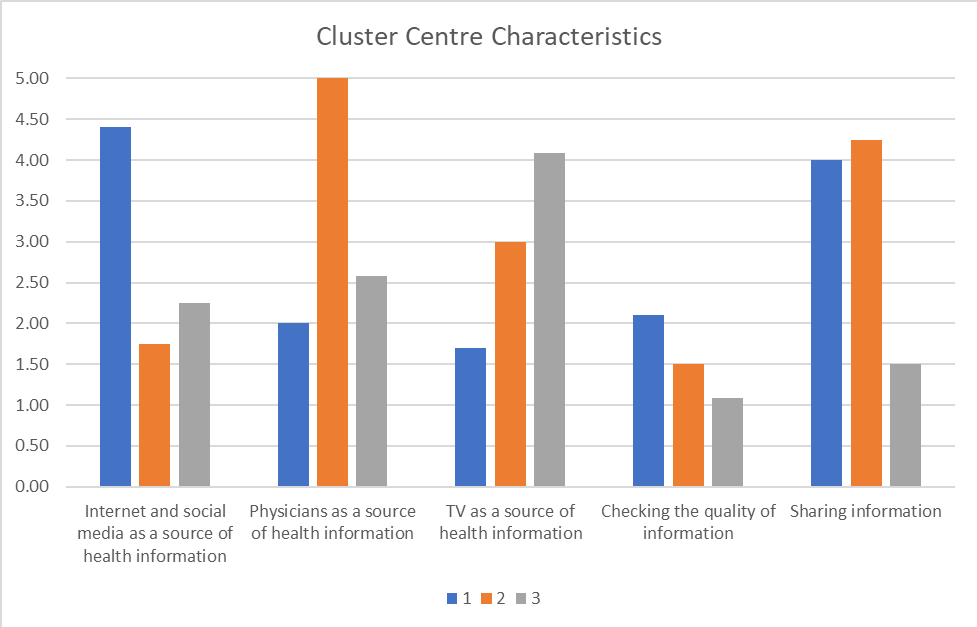

To define the types of information users in the community of people living with HIV for this study, we used k-means clustering. In the cluster analysis we used participants’ responses to questions regarding what sources they used for health information and how often they used them, how they checked the quality of information and whether they shared information with others. The Elbow method was applied to the data set to determine the optimal number of clusters; the results suggested the use of three clusters (Figure 1). Members of the first group were the most active users of the Web and social media for health information. They used physicians and television less often than did the other groups. They also exerted more effort on evaluating the quality of the information they used. Finally, they actively shared information. We called this type Netizens. The average age of the members of the group was 44 years. The average time from HIV diagnosis was six years, and most of the members of the group lived in Tbilisi, the capital city of Georgia.

Members of the second group were the least frequent users of the Web and social media for health information compared with the two other groups. They relied strongly on physicians as a source of health information. They were moderate users of television but actively shared information. We called them Traditionalists. The average age of the members of this group was similar to Netizens - 46 years. The average time from HIV diagnosis was the highest, however – 13 years. All of them resided in regional cities.

The main sources of health information for the members of the third group were television and physicians, in that order. They spent the least effort on evaluating the quality of information compared with the other groups. Finally, they were very privacy conscious and the least willing to share information. We called them Lurkers. The average age of the Lurkers was 40 years. The average time from HIV diagnosis was 8 years, and most of them resided in the capital city.

Discussion

The first research question sought to examine the COVID-19-related information needs of people living with HIV. Participants most frequently referenced the need for information on HIV and COVID-19 comorbidity. Many of them reported having an increased stress level and seeking stress management information on the Web. Increased stress levels can have a harmful effect on the mental health of people living with HIV and on how effectively they manage their chronic conditions (e.g., medication adherence, substance abuse; O’Cleirigh and Safren, 2008). Health service providers may need to increase their efforts at providing this population with stress management services and applications during the pandemic, especially for those groups and communities who feel more vulnerable because of their chronic health conditions (Chiauzzi et al., 2008).

The second research question was aimed at identifying the sources of information that people living with HIV used to obtain COVID-19-related information. Participants were very complimentary of the HIV/AIDS Patients’ Support Foundation and National AIDS Centre and its programmes for supplying them with useful and timely information about COVID-19. This corroborates the findings of another recent study showing that HIV centres and service providers can be effective sources of health information on non-HIV health issues and diseases for people living with HIV (Wigfall et al., 2020). In the present study, we also found that the pandemic lockdown had disrupted the access of some people living with HIV to their regular sources of health information, including the National AIDS Centre, the HIV/AIDS Patients’ Support Foundation and their services. These findings also highlighted the digital divide between rural and urban areas of the country. People living with HIV living in rural areas might not have regular access to the Internet, including the National AIDS Centre website, and might rely on television and their neighbours as sources of COVID-19-related information. The latter could be a source of misinformation and rumours. The digital divide between the country’s urban and rural areas could result in health communication disparities and harm the health-related quality of life of people living with HIV (Philbin et al., 2019). The country should enhance its efforts to provide affordable broadband access in rural areas, to reduce the digital divide and provide rural patients with equitable access to health information.

The third question was concerned with investigating how people living with HIV evaluated the quality of health information. Results of the analysis indicated that most of the participants did not do comprehensive information research on COVID-19. Instead, they relied on a few previously known sources. Likewise, most of them did not engage in a thorough assessment of online information quality. Only half of the participants reported checking the ownership of the sites they visited. Even fewer of them paid attention to the authorship of online information, editorial process cues and how the site was using their information. The level of corroboration among multiple sources and the consistency of coverage on a particular health issue were the most frequently reported quality evaluation heuristics by participants. The consistency of coverage could enhance the user’s sense of coherence and reduce uncertainty. However, the coverage of a particular topic could be consistent but at the same time inaccurate (Brashers et al., 2000). The literature has shown that vote-based quality signals can easily be fabricated (Manning et al., 2008; Zhou and Zafarani, 2020). Misinformation was a concern to the participants we interviewed. Considering that information bubbles can be imposed easily on social media users either voluntarily or by third-party targeted campaigns (Lazer et al., 2018), the community would benefit from health information literacy training. We also found that some participants engaged in collaborative information seeking (Veinot et al., 2006). In particular, they used their personal networks not only to obtain health information but also to evaluate its quality. Government agencies could facilitate the establishment of community led online discussion spaces that could be used by HIV patients to support their collaborative information seeking and sharing practices in a privacy preserving way. In addition, the National AIDS Centre could use the online spaces to intervene with evidence-based, high-quality health information and advice from healthcare professionals that are tailored to the needs of people living with HIV.

The fourth research question focused on the information-sharing behaviour of people living with HIV during the pandemic. When they shared information, participants were motivated for altruistic reasons to help fellow individuals living with HIV and protect them from harm. On the other hand, participants reported privacy concerns and the fear that their health condition could be exposed, their lack of expertise in determining the accuracy of the information and the fear of being held responsible for the consequences of using the information as barriers to health information sharing. These findings echo the report by Boudewyns et al. (2015) that people are less willing to discuss stigmatised topics on social media. The HIV/AIDS Patients’ Support Foundation and National AIDS Centre might consider adding to their Web presence more online private forums where people living with HIV could anonymously discuss and share health-related information and receive professional advice.

Although the participants expressed strong concerns about maintaining their privacy, we also found that they did not check the privacy policies of the websites they used. Multiple factors could be leading to this behaviour. Many of them might have lacked an understanding of how their personal information could be being collected unobtrusively and shared by websites. Another possible explanation could be the possible lack of enforcement of privacy laws online and the lack of related norms guiding the design of Websites in Georgia. Most of the Georgian websites do not provide links to their privacy policies. Finally, as a consequence, participants might not expect Websites to have a privacy policy.

Results of the analysis identified three types of information users in the community of people living with HIV: Netizens, Traditionalists, and Lurkers. Netizens used physicians less often than did the other groups. They were also more recently diagnosed on average with HIV than the other groups. Hence, one would expect that members of this group might have less strongly established ties with physicians and the National AIDS Centre than Traditionalists. The latter group had more than twice as large average time from HIV diagnosis than Netizens. The literature shows newcomers find entering a stigmatised information ecosystem challenging (Lingel & Boyd, 2013). Alternatively, the low use of the Web and particularly social media platforms for health information could be explained by the inertia of their established health information practices. The Web and social media platforms were less accessible and popular in Georgia 13 years ago, especially in regional cities. A future quantitative study with a larger, more representative sample could test these and other hypotheses of the connections among the demographic characteristics and information behaviour of HIV patients.

The user types could be used to develop three personas. Health information communication and services designers can use the types and personas to communicate the information needs and behaviour patterns of people living with HIV to more effectively, evaluate the existing services, and design new health information services and applications (Grudin, 2006; Noar et al., 2009). For example, for Lurkers who relied mostly on TV and physicians to receive health information and were most privacy conscious, the HIV/AIDS Patients’ Support Foundation and National AIDS Centre could design health information and communication interventions that use general communication channels such as TV and radio to push health information to members of this group in a privacy preserving way. In particular, HIV experts could regularly participate in TV and radio shows to deliver COVID-19 related updates and health advice to HIV patients. Similarly, the National AIDS Centre could facilitate the establishment of a community led Web or social media platform-based discussion or question and answer board pr portal for people living with HIV and engage Netizens and Traditionalists as moderators and contributors in that portal. The online portal could facilitate collaborative information seeking and sharing by HIV patients and support their emotional needs in a culturally sensitive way (Brashers et al., 2000; Veinot et al., 2006; Yi et al., 2012).

The study has several limitations. These findings represent the information behaviour of people living with HIV in the small, developing country of Georgia. Hence, they might not be generalisable to people living with HIV in countries with different socioeconomic and cultural characteristics. In addition, the qualitative nature of the study limits the overall generalisability of the findings. At the same time, the study contributes to the knowledge of information behaviour of people living with HIV in the South Caucasus region, where the research on the subject is scarce.

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to examine the information behaviour of people living with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Republic of Georgia. We found that the National AIDS Centre, within the National Center for Disease Control and Public Health, and its programmes helped provide people living with HIV with timely information about COVID-19. People living with HIV also used primary care physicians, television, Websites and their personal networks as other information sources. Some participants reported that receiving COVID-19 information increased their stress levels. Results of the study indicated that people living with HIV who lived or were stranded in rural areas during COVID-19 lockdowns were more underserved and had less access to high-quality COVID-19-related information sources than their non-HIV counterparts. Threats to their privacy and the fear of disclosing their HIV-positive status, uncertainty about the quality of information and fear of being held responsible for the consequences of using the information were identified as some of the barriers they encountered to seeking and sharing information.

In the study, we identified three types of information users among people living with HIV: Netizens, Traditionalists and Lurkers. The findings of this study can be used by health information communicators to help them design effective health communication campaigns for people living with HIV in general and about COVID-19 in particular. The findings herein can be used to help evaluate the country’s overall response to the pandemic in terms of health information services for vulnerable populations with chronic health conditions. These results can also inform the design of information services and systems that are better aligned with the information needs and behaviour of people living with HIV in Georgia and other countries with similar socioeconomic and cultural characteristics.

This study examined information behaviour of HIV patients during the pre-vaccination period of the COVID-19 pandemic in Georgia. A future related study that investigates the information behaviour of people living with HIV after COVID-19 vaccines became available in the country will complement the findings of this study. In another future related study, we will examine the information behaviour of other vulnerable populations in Georgia, such as people who inject drugs and receive methadone substitution treatment. The goal is to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the health information needs and behaviour of vulnerable populations in the country, including their needs for government-supplied health information services during the pandemic.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Joan Bartlett and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

About the authors

Besiki Stvilia is a professor in the School of Information at Florida State University in Tallahassee, Florida, USA. He can be contacted at: bstvilia@fsu.edu.

Ketevan Stvilia is the Global Fund HIV Program manager at the National Centre for Disease Control and Public Health in Tbilisi, Republic of Georgia. She can be contacted at: stviliak@gmail.com.

Izoleta Bodokia is the director of the HIV/AIDS Patients’ Support Foundation in Tbilisi, Republic of Georgia. She can be contacted at: hapsfund_iza@yahoo.com.

References

Note: A link from the title is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

- Altuntas Aydin, O., Kumbasar Karaosmanoglu, H., & Kart Yasar, K. (2020). HIV/SARS‐CoV‐2 co‐infected patients in Istanbul, Turkey. Journal of Medical Virology, 92(11), 2288–2290. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25955

- Bailey, K. D. (1994). Typologies and taxonomies: an introduction to classification techniques. Sage Publications. (Quantitative applications in the social sciences No. 102). https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412986397

- Bawden, D. (2006). Users, user studies and human information behaviour: A three-decade perspective on Tom Wilson's "On user studies and information needs". Journal of Documentation, 62(6), 671-679. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410610714903

- Boudewyns, V., Himelboim, I., Hansen, D. L., & Southwell, B. G. (2015). Stigma’s effect on social interaction and social media activity. Journal of Health Communication, 20(11), 1337–1345. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1018604

- Brashers, D. E., Neidig, J. L., Haas, S. M., Dobbs, L. K., Cardillo, L. W., & Russell, J. A. (2000). Communication in the management of uncertainty: the case of persons living with HIV or AIDS. Communications Monographs, 67(1), 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540129948090

- Calvert, J. K., Aidala, A. A., & West, J. H. (2013). An An ecological view of internet health information seeking behavior predictors: findings from the CHAIN study. The Open AIDS Journal, 7, 42–46. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874613601307010042.

- Case, D. O. (2006). Information behavior. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 40(1), 293–327. https://doi.org/10.1002/aris.1440400114.

- Chesney, M. A., & Smith, A. W. (1999). Critical delays in HIV testing and care: the potential role of stigma. American Behavioral Scientist, 42(7), 1162–1174. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027649921954822.

- Chiauzzi, E., Brevard, J., Thurn, C., Decembrele, S., & Lord, S. (2008). MyStudentBody–Stress: an online stress management intervention for college students. Journal of Health Communication, 13(6), 555–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730802619404

- Chin, D., & Kroesen, K. W. (1999). Disclosure of HIV infection among Asian/Pacific Islander American women: cultural stigma and support. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 5(3), 222–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.5.3.222

- Choi, W., & Stvilia. (2015). Web credibility assessment: conceptualization, operationalization, variability, and models. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(12), 2399–2414. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23543

- Churcher, S. (2013). Stigma related to HIV and AIDS as a barrier to accessing health care in Thailand: a review of recent literature. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health, 2(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.4103/2224-3151.115829

- Davies, M. A. (2020). HIV and risk of COVID-19 death: a population cohort study from the Western Cape Province, South Africa. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.02.20145185

- Eastin, M. S., & Guinsler, N. M. (2006). Worried and wired: effects of health anxiety on information-seeking and health care utilization behaviors. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 9(4), 494–498. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9.494

- Fung, M., & Babik, J. M. (2021). COVID-19 in immunocompromised hosts: what we know so far. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 72(2), 340–350. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa863

- Georgia. Government. (2020, July 13). Prevention of coronavirus spread in Georgia. StopCov.ge. https://web.archive.org/web/*/https://stopcov.ge/en

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Transaction.

- Goodman, J., & Carmichael, F. (2020, June 26). Coronavirus: 5G and microchip conspiracies around the world. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/53191523. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3cRsNmj).

- Grudin, J. (2006). Why personas work: the psychological evidence. In J. Pruitt & T. Adlin (Eds.), The persona lifecycle: keeping people in mind throughout product design. (pp. 642–664). Morgan Kaufmann/Elsevier. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/PersonaBook.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3COyrAb)

- Härter, G., Spinner, C. D., Roider, J., Bickel, M., Krznaric, I., Grunwald, S., Schabaz, F., Gillor, D., Postel, N., Mueller, M. C., Müller, M., Römer, K., Schewe, K., & Hoffmann, C. (2020). COVID-19 in people living with human immunodeficiency virus: a case series of 33 patients. Infection, 48(5), 681–686. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-020-01438-z

- Hogan, T. P., & Palmer, C. L. (2005). Information preferences and practices among people living with HIV/AIDS: results from a nationwide survey. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 93(4), 431-439. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1250318/

- IBM Corp. (2017). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. IBM Corp.

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. (2020, December 16). Mortality in the most affected countries. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3CTmx8e.)

- Johnson, J. D. (2014). Health-related information seeking: is it worth it? Information Processing & Management, 50(5), 708–717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2014.06.001

- Kaptelinin, V. (2005). The object of activity: making sense of the sense-maker. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 12(1), 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327884mca1201_2

- Kaptelinin, V., & Nardi, B. (2012). Activity theory in HCI: fundamentals and reflections. Synthesis Lectures on Human-Centered Informatics, 5(1), 1-105. https://doi.org/10.2200/S00413ED1V01Y201203HCI013

- Lazer, D. M., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., Metzger, M.J., Nyhan, B., Pennycook, G., Rothschild, D., Schudson, M., Sloman, S.A., Sunstein, C.R., Thorson, E.A., Watts, D.J., & Zittrain, J. L. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094-1096. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2998

- Lingel, J., & Boyd, D. (2013). "Keep it secret, keep it safe": information poverty, information norms, and stigma. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(5), 981-991. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22800

- Manning, C., Raghavan, P., & Schutze, H. (2008). Introduction to information retrieval. Cambridge University Press.

- Mestvirishvili, M., Zurabishvili, T., Iakobidze, T., & Mestvirishvili, N. (2017). Exploring homophobia in Tbilisi, Georgia. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(9), 1253–1282. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1244445

- Noar, S. M., Palmgreen, P., Chabot, M., Dobransky, N., & Zimmerman, R. S. (2009). A 10-year systematic review of HIV/AIDS mass communication campaigns: have we made progress? Journal of Health Communication, 14(1), 15–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730802592239

- O’Cleirigh, C., & Safren, S. (2008). Optimizing the effects of stress management interventions in HIV. Health Psychology, 27(3), 297. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012607

- Philbin, M. M., Parish, C., Pereyra, M., Feaster, D. J., Cohen, M., Wingood, G., Konkle-Parker, D., Adedimeji, A., Wilson, T. E., Cohen, J., Goparaju, L., Adimora, A. A., Golub, E. T., & Metsch, L. R. (2019). Health disparities and the digital divide: the relationship between communication inequalities and quality of life among women in a nationwide prospective cohort study in the United States. Journal of Health Communication, 24(4), 405–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2019.1630524

- Reeves, P. M. (2001). How individuals coping with HIV/AIDS use the Internet. Health Education Research, 16(6), 709-719. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/16.6.709

- Rimal, R. N. (2001). Perceived risk and self‐efficacy as motivators: understanding individuals’ long‐term use of health information. Journal of Communication, 51(4), 633–654. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2001.tb02900.x

- Simon, H. A. (1956). Rational choice and the structure of the environment. Psychological Review, 63(2), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0042769

- Smart, L., & Wegner, D. (2000). The hidden costs of hidden stigma. In T. F. Heatherton, R. E. Kleck, M. R. Hebl, and J. G. Hull (Eds.), The social psychology of stigma. (pp. 220–242). Guilford Press.

- Stvilia, B., Gasser, L., Twidale, M. B., & Smith, L. C. (2007). A framework for information quality assessment. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(12), 1720–1733. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20652

- Stvilia, B., Mon, L., & Yi, Y. J. (2009). A model for online consumer health information quality. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60(9), 1781–1791. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21115

- Sundar, S. S., Rice, R. E., Kim, H. S., & Sciamanna, C. N. (2011). Conceptual challenges and theoretical opportunities. In T. L. Thompson, R. Parrott, & J. F. Nussbaum (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of health communication. (2nd ed.) (pp. 181–202). Routledge.

- Vardiashvili, M. (2018, December 2). How HIV-positive people live in Georgia. JAM News. https://jam-news.net/how-hiv-positive-people-live-in-georgia/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/30YApRm)

- Veinot, T., Harris, R., Bella, L., Rootman, I., & Krajnak, J. (2006). HIV/AIDS information exchange in rural communities: preliminary findings from a three province study. Canadian Journal of Information and Library Science 30(3/4), 271-290 https://doi.org/10.29173/cais194

- Wigfall, L. T., Goodson, P., Cunningham, G. B., Harvey, I. S., Gilreath, T. D., Adair, M., Gaddist, B. W., Julious, C. H., & Friedman, D. B. (2020). Understanding community-based HIV/AIDS service organisations: an invaluable source of HPV-related cancer information for at-risk populations. Journal of Health Communication, 25(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.2196%2F17154

- Wilson, T. D. (1997). Information behaviour: an interdisciplinary perspective. Information processing & management, 33(4), 551-572. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(97)00028-9

- Yi, Y.J., Stvilia, B., & Mon, L. (2012). An understanding of cultural influence on seeking quality health information: a qualitative study. Library & Information Science, 34(1), 45-51. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2011.06.001

- Zhou, X., & Zafarani, R. (2020). A survey of fake news: fundamental theories, detection methods, and opportunities. ACM Computing Surveys, 53(5), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1145/3395046