Employment information needs and information behaviour of North Korean refugees

Jieun Yeon, and Jee Yeon Lee.

Introduction. The employment-related information needs and behaviour of North Korean refugees during their settlement in South Korea were analysed, and provisions that public libraries should consider when providing employment-related information to North Korean refugees were suggested.

Method. Semi-structured group interviews were conducted with twenty-one North Korean refugees who had job-seeking experience or who wanted to be employed. Also, five public and NGO workers that aid the employment seeking process for employment support services to North Korean refugees provided field data on the services provided and characteristics of North Korean refugees’ information behaviour.

Analysis. The results were examined using content analysis according to the factors of Dervin’s sense-making theory—situation, gap, and use. We used NVIVO 12 to extract codes from interview parts according to the factors.

Results. The employment situation of North Korean refugees in South Korea can largely be categorised into two types: employment-related and education-related. The frequent subjects of employment information needs were job posting, vocational education, and career. Participants suffered from a lack of intellectual, psychological, and social accessibility. North Korean refugees were most likely to get information from interpersonal sources, the Internet, and public institutions.

Conclusion. We developed a model of North Korean refugees’ information behaviour based on the findings and provided guidance for public libraries on serving job-seeking North Korean refugees.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper914

Introduction

As the field of information behaviour research has developed, more diverse groups and topics have been studied by researchers (Case and Given, 2016; Vakkari, 2008). While early research focused on the information behaviour of professionals, the amount of research on information behaviour and needs in citizens’ daily lives has grown (Vakkari, 2008). The information needs that people experience during migration and resettlement are one of the special needs that researchers are currently focusing on (Greifeneder, 2014). These information needs are important because sufficient information is closely related to immigrants' and refugees' survival and social inclusion (Caidi, et al., 2010; Lloyd, et al., 2013). Thus, scholars focus on understanding these special information needs and barriers to improve their access to information. In early studies, immigrants and refugees were studied under the branch of newcomer; however, there is a growing tendency to study refugee groups’ information behaviour separately, by focusing on the unique characteristics of refugees, including the political nature of refugees’ experience (Lloyd, 2017).

Among the population experiencing immigration and resettlement, North Korean refugees’ experiences are highly unique. According to Article 2 of the North Korean Refugees Protection and Settlement Support Act, North Korean refugees are:

persons who have their residence, lineal ascendants and descendants, spouses, workplaces, etc. in the area north of the Military Demarcation Line (hereinafter referred to as "North Korea".), and who have not acquired any foreign nationality after escaping from North Korea.

In 2017, the cumulative number of North Korean refugees who have entered South Korea exceeded 30,000, and every year more than 1,000 people escape North Korea and arrive in South Korean territory (Korea. Ministry of Unification, 2018). Since the late 1990s, most North Korean refugees in South Korea have come from less privileged groups. Currently, women who have migrated to avoid economic hardship constitute most North Korean refugees (Kim, 2010; Sung and Cho, 2018).

Due to the unique political and historical background of North and South Korea, North Korean refugees share many characteristics of other immigrants, refugees, minority groups, and the low-income class, but at the same time, they have distinctive characteristics (Lankov, 2006). Firstly, it is unclear whether North Korean refugees should be classified as immigrants or refugees. Refugees who have been displaced from North Korea because of economic difficulties are not eligible for refugee status, as defined in the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1954). However, since refugees will be severely punished by the state if they are sent back to North Korea, in 2003, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) suggested that North Korean defectors could be regarded as delegated refugees (UNHCR, 2003). Secondly, North Korean refugees who settle in South Korea have different experiences from other refugees or migrants. Upon arrival in South Korea, they are granted nationality equivalent to that given to citizens born in South Korea and receive settlement subsidies for housing, employment, medical care, education, etc. (Korea. Ministry of Unification, 2017). In contrast, most refugees and migrants must go through complex legal procedures to gain legal status in their receiving society without active support from the receiving society. Thirdly, even though both North and South Koreans speak Korean, a language barrier still exists. This is because the Korean language has evolved differently in the North and the South after the division of Korea, especially in pronunciation, accent, and loanwords. The greatest challenge for North Korean refugees in accommodating to South Korean language usage is learning English loanwords (Shin and Kim, 2014). Moreover, the North Korean accent is stigmatised in South Korea (Lee, 2016). Finally, North Korean refugees are from one of the most closed societies in the world, which means that they have distinctive prior experiences.

Because of these unique characteristics, North Korean refugees cannot be considered as equivalent to any other population, even though they have many similarities to other refugees or migrants. Some of them leave South Korea again and settle in other countries; therefore, it is important to maintain a worldwide interest in the reality that they must face.

In this study, we focused on the North Korean refugees' information needs related to employment to support them in experiencing grim economic status compared to normal South Korean citizens. North Korean refugees show a higher unemployment rate (7%) compared to the national average (3.6%). Also, the monthly wage of refugees is 1.78 million won ($1,780) while the average South Korean paid worker earns 2.42 million won ($2,420) per month. This gap can be explained by North Korean refugees' employment status. North Korean refugees are more likely to work as an elementary worker (21%, national average 13.3%) or service worker (27.3%, national average 10.9%), which do not require a high skill. Even though 57.3% of employed North Korean refugees are regular workers (the national average is 50.2%), 16.5% work as a daily worker. This ratio is approximately three times higher than the national average of 5.3 % (Korea Hana Foundation, 2018). One possible reason for the difficult employment situation of North Korean refugees is limited access to sufficient employment information (Lee, 2017; Park and Oh, 2012). To support such refugees to navigate better in a new society, this study explores their employment-related information needs and behaviour, which are also one of the most commonly reported information needs from immigrants and refugees worldwide (Atiso, et al., 2018; Khoir, et al., 2015a; Mansour, 2018; Silvio, 2006; Sirikul and Dorner, 2016).

Specifically, our research questions are as follows:

- RQ1. What employment-related situations do North Korean refugees experience?

- RQ2. What kind of employment-related information needs do North Korean refugees have?

- RQ3. What difficulties do North Korean refugees face in meeting their information needs for employment?

- RQ4. What are the characteristics of North Korean refugees’ information behaviour related to employment?

By examining these questions, we aimed to propose guidance for providing an employment information service for North Korean refugees in public libraries.

Literature review

North Korean refugees are at the intersection of multiple groups: refugees, immigrants, less privileged populations, people experiencing information poverty, and newcomers. Therefore, in addition to North Korean research, this study also examined the research on refugees, migrants, and information poverty, sharing characteristics with North Korean refugees.

Information needs and behaviour of immigrants

Immigrant studies excluding refugees have shown the following information behaviour characteristics (Caidi, et al., 2010). Immigrants’ needs for orienting information are spread out across cultural and religious events, politics, identity, etc. For problem solving during settlement processes, migrants often seek information on language, employment, community, housing, health, education, law, transportation, and banking. It has been found that their information needs are affected by various factors, such as settlement process, personal circumstances, age, and motivation, and immigrants’ information needs gradually diverge from general to detailed and personal topics (Khoir, et al., 2015a; Shoham and Strauss, 2007; Sirikul and Dorner, 2016; Su and Conaway, 1995).

Traditionally, many studies have reported the importance of interpersonal information sources to immigrants. Immigrants get information from personal relations; they also exchange information with the people they encounter at information grounds (Bronstein, 2017; Fisher, Durrance and Hinton, 2004; Fisher et al., 2004; Khoir, et al., 2015b). In addition, gatekeepers who can speak both the native language of the immigrant and the language of the receiving society are a primary information source (Jeong, 2004). When information is not available in the receiving society, a transnational information source may be used, such as a family member or a friend in the home country (Srinivasan and Pyati, 2007). In some cases, immigrants seek settlement information from online community websites created by immigrants from the same nation (Lingel, 2011). In addition, immigrants face many difficulties in the process of settlement in their new countries. Language barriers are the most common challenge, and a lack of understanding how the receiving society’s social systems work is also an obstacle to seeking information effectively (Fisher et al., 2004; Jeong, 2004; Khoir, et al., 2015a; Su and Conaway, 1995).

Information needs and behaviour of refugees

Unlike the typical migrants discussed above, refugees are defined by international law. They are looking for a safer place outside their home country because they fear persecution for reasons such as race, political opinion, religion, ethnicity, and culture. They are likely to experience very complex and dangerous situations because their lives are at threat if they do not have protection in a safe country (Lloyd, 2017).

Despite its urgent need, interest in refugees in the field of information science is just beginning. Some of the studies examined adult refugees who have settled in receiving societies and are receiving appropriate protection (Mansour, 2018; Twork, 2009), while some researchers have studied refugees who have not arrived in the receiving society yet or who suffer from an unstable situation in a refugee camp (Hannides, et al., 2016; Nekesa Akullo and Odong, 2017; Obodoruku, 2014). Their prevalent information needs include essential information for daily life, such as health, employment, and education, as well as refugee-specific information, such as up-to-date information on their homeland situation or information on legal procedures to ensure refugee status. Refugees rely on interpersonal information sources, the Internet, and social media to obtain information. The difficulties they face in seeking information are largely akin to those experienced by immigrants, but they are more likely to lack the information technology required to access information. Also, limited time and money as well as social and cultural barriers affect the information seeking behaviour of refugees (Nekesa Akullo and Odong, 2017; Mansour, 2018).

Like information seeking research on immigrants, factors that affect refugee information needs or behaviour have been investigated. Oduntan and Ruthven (2017) discovered that different modes of information behaviour arise depending on the status of refugees. Moreover, Lloyd et al. (2013) argued that refugees in the early stages of settlement obtain information through other immigrants who have settled first, and they gradually adapt to the information landscape of the new country as their information literacy improves. In addition, some studies observed that information needs vary according to the characteristics of the refugee, such as past residence, gender (Obodoruku, 2014), and level of education (Mansour, 2018; Martzoukou and Burnett, 2018).

Information needs and behaviour of North Korean refugees

In the field of information science, only a few studies have considered North Korean refugees: there have been two studies on their everyday life information behaviour (Cho, 2006; Koo, 2016). The information needs on job seeking appear commonly in research on information needs of North Korean refugees as well as those of immigrants (Khoir, et al., 2015a; Sirikul and Dorner, 2016). This suggests that employment information is one of the essential pieces of survival information for newcomers and might help them to solve the problems they face in daily lives (Marcella and Baxter, 2000).

The preferred information sources of North Korean refugees are interpersonal information sources and mass media, but the preferred type of interpersonal information source varies. Cho (2006) found that participants were most likely to prefer other refugees among interpersonal sources, but Koo (2016) reported that Hana Centre (the residence settlement support centre in local communities) staff were refugees’ most preferred source. Further, a gatekeeper (i.e., a North Korean refugee (Cho 2006)), such as Hana Centre staff, and local volunteers (Koo, 2016) play a role in connecting the North Korean refugee community and the outside world. In addition, in Koo’s (2016) study, it was ascertained that North Korean refugees with a higher level of post-traumatic stress disorder tend to seek information more passively, which indicates that psychological factors can affect the information behaviour of refugees.

Several studies regarded immigrants and refugees as experiencing information poverty (Caidi and Allard, 2005; Khoir, et al., 2015b; Lloyd, et al., 2013; Shen, 2013). Information poverty indicates a state in which a person cannot effectively seek information, and it is caused by a lack of information literacy or even the disregard for the importance of the information itself (Goulding, 2001; Jaeger and Thompson, 2004; Marcella and Chowdhury, 2020). One of the significant features of the information poor is that they are disconnected from general society (Jaeger and Thompson, 2004). According to a renowned study on the information world of the impoverished by Chatman (1986, 1987, 1996), social norms in their world and self-protecting mechanisms prevent active information seeking.

North Korean refugees belong to the periphery of South Korean society and experience information poverty. Cho (2006) explored the external and internal causes of their information poverty. As external factors, information services of the government and non-governmental institutions in the local community were insufficient. Intrinsic factors included a lack of proficiency in Korean, poor information literacy, and passive attitudes towards information seeking. In addition, since there is almost no link between North Korean refugees and South Korean society, they tend to obtain information from their closed network. While most of the respondents maintained active information sharing between North Korean refugees, some respondents noted that they try to avoid interaction with other refugees and consider the information from North Korean refugees as useless or untrustworthy. This is because some North Korean refugees had committed fraud against others by providing misinformation.

Employment information needs

Information needs related to employment is not a well-researched area. So far, the studies have highlighted the employment information needs of marginalised groups, such as a low-income class, or people with disabilities. Yet, employment information needs of specific job category, age, or other demographic characteristics still requires more research. Although it is difficult to find a clear pattern of information behaviour related to employment due to the limited number of studies, we can assume that the behaviour is highly dependent on the information seeker’s situation.

For example, Chatman (1986) analysed the employment information diffusion among female participants of the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA). In this study, Chatman found that the most prominent factor of information diffusion is timeliness. Interestingly, well-diffused information is devalued since the more people know the information about the job, the more competitive the job becomes. In the following study, Chatman (1987) further analysed the characteristics of opinion leaders among the female CETA participants. The opinion leaders were active in social participation and utilised libraries and media well. However, they were reluctant to share information about a decent job because they also wanted to take the job. Henry (2012) studied how people with intellectual disabilities seek employment information. He found that past experiences discouraged people with intellectual disabilities to search for employment information. Participants preferred personalised interpersonal information sources to printed information. In the meanwhile, Webber and Zhu (2007) reported a totally different preference for employment information sources. They interviewed young British Chinese adults to understand which information source they prefer in finding employment information. As a result, they found that the participants prefer the Internet to interpersonal sources. However, they found their current job from a newspaper or magazine, which shows the preference and effectiveness of information source are different.

Theoretical frames

We applied Dervin’s (1983) sense-making theory as an analytical framework for examining information needs related to employment that occur in the specific context of North Korean refugees. Dervin’s sense-making theory is about how people create their sense of the surrounding world. People encounter a discontinuous situation that they cannot pass through with the current sense they have while continuing their experience in space and time. The discontinuous point is a gap, and the context of time and space in which sense is created is the situation. An individual tries to bridge the gap by collecting information, and the result of gap-bridging is called use or help (Dervin, 1983; Savolainen, 1993).

Many studies, including Dervin’s (1992) study, have defined information seeking as an action that individuals take when information needs arise (Case and Given, 2016). However, individuals sometimes acquire the information they need without taking a specific action. Various models that include passive information seeking have appeared (McKenzie, 2003; Williamson 1998; Wilson, 2000). Since people seek information both actively and passively in their everyday lives, excluding passive information seeking might limit the scope of information behaviour studies (McKenzie, 2003). For this reason, we analysed not only active information seeking but also passive information seeking to understand the information seeking behaviour of refugees more thoroughly.

In addition, we used Dervin’s early research (1973) to categorise the various obstacles during employment information seeking of North Korean refugees. In the 1973 study, Dervin explained how individual residents, information needs, sources, and solutions are connected to each other in terms of five accessibility concepts: 1) societal accessibility, which indicates whether the appropriate source of information is available in the entire society or in the community, 2) institutional accessibility, which is related to the ability and willingness of the agency to provide the necessary information, 3) physical accessibility, which is related to the ability to make contact with sources, 4) psychological accessibility, which is related to difficulty in using information sources because of psychological discomfort in information seeking or refusal of information seeking itself, and 5) intellectual accessibility, which shows whether individuals have the knowledge they require to obtain information. Dervin assumed that there is a barrier in information seeking when some or all accessibilities are limited.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Our sample consisted of twenty-three North Korean refugees in South Korea aged fifteen and over who had job-seeking experiences before or who were seeking employment actively. It is well known that some refugees are highly anxious about the exposure of their identity since the exposure may cause harm to their families still living in North Korea (Chae and Yhi, 2004; Choe et al., 2012). Due to this characteristic, except for a few participants, it was not easy to find research participants who actively volunteered for the research. Furthermore, individual researchers could not reach a broad group of the research population. Thus, to encourage participation, we chose the snowball sampling method. First, we announced the recruitment of research participants in two online communities that are frequently used by North Korean refugees. One community, founded by North Korean refugees more than five years ago, is mainly used for a personal status update, sharing information, second-hand sales, and advertising. Another community has been managed by a non-profit organization of North Korean refugees for more than ten years. The members mostly use this community as an online debate bulletin, and a family and friend reunion bulletin. We chose these two communities because both were actively used and accessible by the public. Five refugees, including the pilot interview participants, applied for the interview. Then, they introduced eighteen research participants to make a total of twenty-three participants. We included participants whose period of residence in South Korea varied to capture how social changes in South Korea affected or did not affect the information behaviour of North Korean refugees. Additionally, by recruiting participants who had lived in South Korea for over six years, we intended to observe the change in their information behaviour. By recruiting participants both from the online community and personal network of research participants, we tried to avoid the overrepresentation of the population who could utilise digital devices well. Based on prior research and in-depth interviews with refugees, we recruited five public and non-governmental organization workers who responsible for providing employment support services to refugees, too.We conducted semi-structured interviews in Korean with groups of two to four people who knew each other to create a comfortable atmosphere and to encourage the North Korean refugees to provide candid answers. It is known that if there are similar experiences among participants in a group interview, participants are more likely to share information (Tracy, et al., 2006). We applied this technique because a previous study reported that North Korean refugees are information poor (Cho, 2006). People in information poverty live in a closed society of insiders with similar identities to protect themselves, and they hide and sometimes lie about their own situation or problem (Chatman, 1986). Sometimes, the researchers had to stop the group interview because of the time constraint of the participants, especially female participants. This time constraint for women from specific ethnic backgrounds is not unusual (Cannon, et al., 1988). In these cases, the researcher set an additional personal interview to finish data collection. Interviews took place between August 2018 and September 2018, and each interview lasted between 30 and 160 minutes depending on the number of participants.

We developed interview questions about situation, gap, and use based on previous research and the sense-making theory (Cho, 2006; Dervin and Clark, 1987; Dunne, 2002; Harris, 1988; Julien, 1999; Pettigrew, 1999; Webber and Zhu, 2007; Williamson, 1998). First, to grasp the situations of the participants, we used a timeline interview technique suggested by Dervin. We encouraged participants to describe all experiences relevant to employment in chronological order (Dervin and Clark, 1987).

Secondly, the questions about gap covered information needs and difficulties encountered when trying to obtain information. Thirdly, questions about use covered information sources and evaluation. Additionally, we asked questions about experiences of obtaining information by chance, i.e., passive information seeking. We also asked some ad hoc questions based on the interviewees’ answers. We eliminated any English loanwords in the interview questions because prior studies reported that North Korean refugees experience a language barrier mostly due to English loanwords in South Korean language (e.g. Shin and Kim, 2014). As some participants answered based on memories some years ago, we asked several clarification questions during the interviews. Sometimes, the participants helped each other to recall specific terms or memories. In the interview with public and non-governmental organization workers, participants offered field data on the services provided and the characteristics of the refugees’ information behaviour.

We had some research participants who expressed concerns about the exposure of their identity and seemed reluctant to share personal information. Thus, we tried to assure participants by mentioning more than once that all data would be anonymised and discarded after the research. Moreover, the interview solely focused on collecting data directly related to employment in South Korea without excessively probing personal information, especially personal history back in North Korea. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that the participants' cautiousness may have affected their answers.

Data analysis

Voice recordings of the interviews were transcribed, and content analysis was conducted. We used NVIVO 12, a qualitative research analysis program, to extract codes from parts of the interviews according to situation, gap, and use. Next, we created a codebook containing definitions and examples of each code and coded the entire interviews. In this process, some modifications were made to the code. After the coding process, intercoder reliability of one group interview was assessed between the first author and another researcher in the Master of Library and Information Science program based on Cohen’s Kappa. The correlation was found to be 0.91, which indicates a reliable result (Cho, 2008). Interviews with public and non-governmental organization workers were also recorded and transcribed. Some of these transcripts were used as a reference for interpreting the results of the interviews with the refugees.

Findings

Among the respondents, twenty (87%) were female, and three (13%) were male. Five (22%) had lived in South Korea less than three years, five (22%) between three and less than five years, seven (30%) between five and less than ten years, and six (26%) over ten years. The numbers of participants in their 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60s were ten (43%), eight (35%), 3 (13%), and two (9%), respectively. Among the public and non-governmental organization workers, A and B are executives of such an organization for North Korean refugees, and they have managed their respective organizations for more than ten and three years. C is a police officer who has worked as a local protection officer for North Korean refugees for more than three years. D is a job protection officer at the Employment Support Centre, and E is an employee at the Hana Centre, and both have worked for more than a year in their respective jobs.

Situation

The occurrence of a specific information need is influenced by context, and there is a more fundamental need behind the information need (Wilson, 2000). Therefore, to understand information needs related to the employment of North Korean refugees, it is necessary to explain the time, space, and context in which such needs appear and to examine what primary needs exist. In this section, to answer research question 1, we analyse experiences related to employment that occurred after North Korean refugees arrived in South Korea. The situations relevant to employment were categorised into two groups: situations directly related to job seeking and the others related to education.

Respondents face situations directly related to employment, mainly owing to their financial needs, dissatisfaction with jobs, emotional causes, and hopes of learning more about South Korean society. Before settling into South Korean society, North Korean refugees are required to take a 12-week education at Hanawon (the initial settlement support centre for North Korean refugees, which is a completely closed residential facility) and encouraged to take an eight-day settlement course at Hana Centre. These courses include career development and vocational skill courses. After completing Hanawon courses and stepping into South Korean society, all participants had experienced a situation in which they were forced to find a job because of their financial needs. Cho (2006) also explained that North Korean refugees have an urgent need for information about employment because of poverty. Immediately after arriving in South Korea, they have no money for living expenses even though the South Korean government subsidises them with a few million won (a few thousand dollars) as settlement support because they must pay a fee to their refugee broker. As a result, they are compelled to find a temporary job that they can start as soon as possible without any qualification or experience.

When arriving in South Korea, we have Maslow’s hierarchy of needs... The basic needs of human beings must be filled and solved first, but it seems difficult to solve for recently arrived refugees. Only after fulfilling their needs, people can think about who I am. (Worker B)

As Worker B mentioned, it is difficult for recently arrived North Korean refugees to think of any needs other than financial needs until they are financially able to support themselves in South Korean society. Therefore, we can assume that it is important for recently arrived refugees to efficiently collect job postings or other information about making money. In this study, job postings were defined as any type of announcement for a job opening spread by the Internet, flyers, and word-of-mouth. After they inevitably take a temporary job as their first job in South Korea, their situations change; they start to require more information on employment because of dissatisfaction with their current jobs. After working in dire conditions to earn enough money to meet their basic needs, they try to find a better job.

In addition, we discovered a situation in which the refugees want to be employed for emotional reasons. In this situation, the participants want a career to interact with people because they feel empty or stifled if they linger at home all day. Moreover, some participants responded that they sought work to learn more about South Korean life.

We also identified a situation linked to vocational education and found that it has a different cause than the situation directly related to employment. More than half of the participants felt a need to have more education because of job dissatisfaction. Because participants often take any temporary job to earn money, they become dissatisfied with their job because of excessive work intensity and job instability. As a strategy to overcome this situation, the refugees wanted to pursue vocational education and move to a better job. The next most popular response was a personal recommendation. Some participants felt the need for education only after getting a recommendation from other people. In other words, participants started considering an education when they received new information from their social network. This means new interpersonal information can motivate them to change their situation. The participants heard advice from other North Koreans, such as spouses and friends, employers, colleagues, or educators of Hanawon or vocational education institutions. However, some participants wanted to receive education just to obtain education subsidies from the South Korean government without clear needs of education. In addition, participants also felt the need for education because of the lack of job skills, boredom, difficulties in finding a job, regrets about lack of opportunities to learn in the past and need for useful knowledge about childcare.

The above results indicate that refugees require information about employment and education continuously as they explore South Korean society. In the beginning stage of settlement, refugees tend to take temporary work because of their financial needs, but as they accumulate experiences in the workplaces, they required a more stable job by getting an education or by putting more effort into job seeking. In conclusion, the situation related to the employment of refugees changes with time.

Information needs

To answer research question 2, the employment-related gap was analysed according to the subjects of information needs and the challenges refugees face when these needs occur. Their information needs and relevant information sources mostly varied based on their experiences (i.e., education, employment, etc.) in South Korean society rather than other personal traits.

The majority reported that they required information on job postings. Our participants mostly use local magazines, the Internet, and smartphone applications to seek a temporary job shortly after arriving in South Korea. Some participants reported obtaining information about job postings from North Korean neighbours. Many refugees live in the same public apartment buildings because the government provides public housing for North Korean refugees. This spontaneously creates a social network among refugees in the same apartment building, and they use each other as information sources. In some cases, refugees build a network of refugees who worked in the same profession in North Korea, or they form a social network through online communities created by refugees. Interestingly, although Chatman (1986) reported that the low-income class is not willing to share information about a preferable job since the more people know about a job, the more intense the competition is, we found that refugees actively exchange better job opportunities through their networks. For example, E1 explained his experience of sharing job information with other refugees:

I have a friend called____, a movie director [who is also a North Korean refugee]. One day, he called me... I asked "Why did you call?" then he told me that the Ministry of National Defence is hiring North Korean army civilian... Anyway, we decided to encourage everyone in the organization to apply for the job. The Joint Chiefs of Staff posted the job vacancy. It was insane. (E1)

Compared to the chance of getting information from North Korean refugees, there is less chance of obtaining information on job openings from South Koreans because it is more challenging to build connections with them especially right after they enter South Korean society. However, once the participants acquired a job, they started using South Korean employers and colleagues as their information source. This change indicates that North Korean refugees broaden their social network with South Koreans by having a job. In some cases, participants encountered South Korean strangers who offered them jobs, or they inquired about a job vacancy with random South Koreans. Similarly, especially in the early stage of settlement, there are cases where participants asked for job information from their local protection officer. Some participants tried to find a job using public institutions that offer support for employment, but the results varied; some found it very useful, but some others did not find a suitable job from the institutions.

In line with the needs of the job posting, refugees new to South Korean society want to know specific information sources for job postings. The interviews showed that participants learned the technique of finding job postings from Hanawon or other refugees. Sometimes, participants incidentally discovered a job information source, e.g., they encounter a local magazine on the roadside and use it as a job information source.

Another major information need was information on vocational education and job certificates. Participants often obtain this type of information through public institutions and interpersonal sources. Many South Korean educators in universities, job training centres, etc. provided information to the refugees during classes or personal meetings. Additionally, participants found useful information about training and certification from the Internet, local magazines, and flyers.

Meanwhile, participants needed information related to the definition of a job, requirements for a particular job, and job prospects. They needed to collect this type of information to be more familiar with the capitalist concept of selecting a job by themselves. The most popular source for career-related information was other refugees. When they want to try a new occupation, they often gather information about their acquaintances’ jobs while socialising with them. In addition, like the need for information on vocational training and certificates, information on careers comes from South Korean educators. Apart from this, some respondents asked a stranger what qualification is required for their job. Participant D2 said that she visited a public library near her home and asked a librarian at the circulation desk about how to become a librarian. Participants also utilised the Internet to gather career information, e.g., the type and prospect of occupation and the average salary and working hours of a specific occupation.

In addition, we discovered information needs on formal education, government employment support, employment processes, and career biography, most of which are satisfied using interpersonal sources or public institutions. More specifically, information on formal education, such as universities and lifelong education programmes, is actively exchanged among refugees. However, in the case of employment support and career biography, public institutions are the primary source of information.

Barriers to information seeking

To answer research question 3, we adopted accessibility categories suggested by Dervin (1973) to identify obstacles to seeking employment information for North Korean refugees. As a result, most participants reported that they experienced a barrier because of lack of intellectual accessibility. Also, many experienced a lack of psychological and social accessibility. Most of the difficulties occurred during the early settlement stage in South Korea.

Lack of intellectual accessibility can be categorized into two subcategories: low level of skills relevant to information seeking, such as language skills or information technology skills, and lack of information literacy, such as difficulties in articulating information needs or selecting information sources. The number of participants who expressed difficulty in not knowing where to find information was the greatest. In the initial stage of settlement, their knowledge about information sources was limited, and their social networks were not wide enough to get help with information seeking. Many participants said that they could not use electronic devices well, especially when they first entered South Korea. According to the 2017 Report on the Digital Divide, North Korean refugees have less ability to utilise personal computers and mobile devices than the average South Korean citizen (Korea. Ministry of Science and ICT and Korea National Information Society Agency, 2017). Because most refugees do not use the Internet or mobile phones when in North Korea or a third country, they enter South Korea without proper digital skills. Hanawon offers education on using the Internet and mobile phones, but insufficient class time causes many refugees to start living in South Korea without knowing how to utilise digital devices. However, the participants had gradually improved their digital skill as they participated in education or started working.

In addition, some participants felt unfamiliar with job information seeking since there is no concept of ‘choosing occupation’ in North Korea. Similarly, there was a response that they were unable to accurately express their information needs because they did not exactly know what to find.

Next, a lack of psychological accessibility was defined as abandoning a specific information source or refusal of information seeking itself because of psychological reasons, such as reluctance or discomfort. First, some participants expressed the psychological rejection of obtaining information from public institutions. For example, some participants do not use public institutions as information sources since they felt uncomfortable with the public workers in charge of supporting refugees. H1 complained that some public workers seemed like they were monitoring them:

I had a gut feeling. In fact, for five years since living in South Korea, the National Intel Service had been very interested in me... I cut off any chance of information exchange with them because they [public workers] seemed to watch me. (H1)

Secondly, respondents who were unfairly refused employment several times because of their North Korean intonation were no longer willing to seek employment information. In other words, South Korean society’s discrimination toward North Korean refugees produced a barrier to information seeking. A small number of participants also reported that they avoided employment information seeking because job searching is extremely complicated and will stress them out.

Seven participants indicated that it was challenging to obtain information because of the absence of social accessibility. In this study, social accessibility means the abundance of information or information sources in the whole of society or the social network around North Korean refugees. Many participants pointed out that it is difficult to get information because of the deficient human network:

Refer friends to... No, considering that I also only have limited information, and everyone just has too much on their plate, so it’s impossible to refer someone to a job. (Worker A)

Moreover, some participants mentioned that the quality of information shared among refugees is poor. As confirmed in previous studies, the social network of refugees mostly consists of other North Korean refugees (Jung and Sohn, 2015), which causes information sharing to occur among North Korean refugees only. Furthermore, because many refugees are in temporary employment or do manual labour, some participants pointed out that high-quality information related to employment did not exist in the network.

In addition, a lack of physical accessibility in time, health, and transportation and a lack of institutional accessibility because of disappointing services for refugees by public institutions were reported. Particularly, E2 mentioned that she could not easily visit the Hana Centre to get information when she lived in a rural area because public transportation conditions are relatively poor and the distance between the Hana Centre and her residence was too far.

Information seeking behaviour

To answer research question 4, this section focuses on the types of information sources, activeness and passiveness of information seeking by source type, and the evaluation of information sources, particularly the reasons for preferring specific information sources. In this study, we defined active and passive information seeking as information seeking with explicit information need and the unintended acquisition of information without explicit information need, respectively. This study classified information seeking behaviour based on the context of the interview in the case of no significant sign of activeness or passiveness, and we excluded some behaviour from the analysis if neither activeness nor passiveness could be inferred from the context. Table 1 shows the types of information sources and types of information seeking behaviour by information sources.

| Code | Active | Passive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | North Korean | Friend | 7 | 12 |

| Spouse | 1 | 1 | ||

| Colleague | 1 | 1 | ||

| Family | 1 | - | ||

| South Korean | Educator | 4 | 7 | |

| Colleague | - | 3 | ||

| Stranger | 3 | 2 | ||

| Local protection officer (police) | 2 | 1 | ||

| Employer | 1 | 3 | ||

| Priest | - | 2 | ||

| Korean-Chinese | 1 | - | ||

| Public institution | Hana Centre | 6 | 5 | |

| Hanawon | - | 6 | ||

| Employment support centre | 1 | - | ||

| Korea Hana Foundation | 2 | 2 | ||

| Community service centre | 2 | 1 | ||

| Internet | 12 | 1 | ||

| Local magazine | 10 | - | ||

| Smartphone application | 8 | - | ||

| Flyer | 1 | 1 | ||

| News | - | 1 | ||

| TV | - | 1 | ||

| Employment agency | 1 | - | ||

In line with the findings of Cho (2006) and Koo (2016), we confirmed that participants exchanged information with other refugees, such as friends, spouses, colleagues, and family members, who share similar experiences with them. Most participants responded that they received information from their friends, spouse and colleagues. They exchanged job-related information when catching up with each other or when finding someone to participate in vocational training together. Interestingly, D4 and E1 showed the characteristics of opinion leaders found in previous studies (Chatman, 1986, 1987; Cho, 2006; Koo, 2016). These two participants are both male and worked as soldiers in North Korea. In addition, they have excellent computer literacy and manage an online community of refugees, and founded an organisation of North Korean refugees by themselves.

Some of the female participants who were married to North Korean refugees received information from their spouses, which means that their spouses acted as a gateway of information to them:

So, I’d study for computer literacy certificate... Then I want to have a different job, like what my husband does. I’d choose an easier and more stable job. My husband says I can get that job if I have skills. (B2)

Their spouses, who arrived in South Korea more than five years before them, continually provide them with information because they have more experience of life in South Korea. Therefore, these female participants seem to have not felt as much need for information sources as their spouses.

When North Korean refugees are used as information sources, both active and passive information seeking occur, but passive information seeking is more common. Employment is one of the most frequent topics of daily conversation between refugees. Therefore, even if they do not have specific information need, they often get new job-related information for their conversations. Moreover, because other refugees likely have similar information needs, some share information with their friends in advance, even though those friends have not actively requested information. Participants preferred North Korean refugees because of trustworthiness. Participants considered the information from North Korean refugees as reliable since it is information provided based on personal experience of settlement, and the reliability of information and trust in the person offering information are interconnected. However, some participants mentioned that they heard that some North Korean refugees introduced illegal jobs to others or committed fraud by giving them misinformation. One participant noted that she does not ask North Korean refugees about education or training, because she believes that they have no valuable information.

Participants also obtain employment information from South Koreans. As North Korean refugees gain experiences of education and employment in South Korea, they are more likely to meet South Koreans and seek information from them. In other words, a North Korean refugee has more difficulties in information seeking from South Koreans if they do not have a chance to participate in education or get a regular job where they can widen their social network. For example, some participants relate their chance of employment or education to their age. F1, a woman in her fifties, had not thought of vocational or formal education because she felt the education is more for young people. As a result, her employment information seeking was limited to passive information seeking from flyers or Hana Centre by chance. This case shows that limited social experience results in limited access to information.

The most frequently mentioned information source was educators, such as professors or lecturers North Koreans meet in classes. Educators provide information on vocational education, job certificates, and careers to North Korean refugees. In the case of educators, passive information seeking occurred more frequently because many participants met their employment information needs by information transfer through classes. We also noted that most of the educators mentioned by participants are familiar with the characteristics of North Korean refugees through constant contact with the refugees in classes. Colleagues, strangers, local protection officers (police officers), and priests are also interpersonal information sources. When asked for their preference for interpersonal information sources from South Korea, participants showed their preferences for a professor. Participants described that they like to seek job-related information from a professor because the professor can immediately provide them with a detailed and accurate answer.

Other than interpersonal sources, the most frequently used sources were Internet and smartphone applications. Particularly, participants who have information technology skills actively sought employment information on the Internet and smartphone applications. The principal reason they prefer the Internet as a source of employment information is that they can acquire a large amount of information at once. B1 explained that she usually collects many job postings through the Internet and then compares them all before deciding which job to apply for. Besides, D4 uses the Internet because of his independent personality. However, some participants used the Internet because it was the only option they had:

Back then, Hana Centre didn’t exist. Nowhere to call for help. I had no single plan but just kept searching. There was a site where employers put up a job posting for North Korean refugees. I searched that site every day. (D1)

Again, we validated the lack of social networks and a lack of knowledge of information sources in the early days of settlement and the difficulties that arise from the absence of public institutions in the local community.

In addition, participants used local magazines primarily to search for job postings at the beginning of their settlement. Given that local magazines are usually distributed at front doors, bus stops, and downtown, several participants came across local magazines serendipitously. One participant tried to look for a local magazine or newspaper as she had an experience of finding jobs by reading a local magazine when she resided in China, which means previous experiences in information seeking can affect current information behaviour.

Some participants reported that they had obtained information through public institutions. The most frequently mentioned institution was the Hanawon and Hana Centre. North Korean refugees obtain basic information on occupation, education, and job certificates in Hanawon. They merely absorb employment-related information from settlement programmes, but they do utilise the information obtained from Hanawon after settling in South Korean society:

I was so interested in the outside world, and excited to meet the dazzling world out there, so things just went in one ear and out the other. I didn’t learn much. (D3)

As D3 mentioned, North Korean refugees often fail to remember information from Hanawon programmes because they have no explicit information need or experience needed for evaluating the importance of information before living in South Korea.

While Williamson (1998) reported that information users tend to actively seek information from institutional sources, in this study, we found that several refugees passively obtain information from public institutions. According to Worker E, there is a need to provide such pre-emptive information because refugees often fail to recognise public institutions as information sources:

At first, right after arriving here, North Korean refugees generally don’t know whether they can call us [Hana Centre]. We know that, so we visit them one by one. (Worker E)

Discussion

Comparison between previous studies and the current study

This study applied a qualitative method and focused on the employment-related information needs of North Korean refugees. Even though the previous studies on North Korean refugee's information needs utilised different methods and focus, there are common themes between previous studies and the current study.

First, the preference for information sources varies among studies, but some, including the current study, found that the preference changes over time. For example, in Cho's (2006) study, he reported that 80% of respondents whose length of stay was less than one year preferred North Korean refugees as an information source, but only 45.8% of respondents who had lived in South Korea more than four years prefer North Korean refugees. In the current study, we also discovered that the participants started seeking information from South Koreans as they gained more experience in South Korean society. However, Koo's (2016) study found that the most preferred information source of North Korean refugees is staff of Hana Centre. This finding might be affected by her participant recruitment at Hana Centre. It is also possible that information behaviour, including the preference for information sources, relevant to employment can be different from other information behaviour since it is directly related to survival. Employment information should be accurate and up to date to find a decent job. Chatman (1986) also noted that the competitive and timely nature of employment information changed information behaviour. To understand differences among studies, further research about North Korean refugees' information behaviour is required. Also, a study on employment information need can be pursued.

Second, North Korean refugees not only showed a positive attitude toward North Korean refugees as an information source but also a negative opinion. As Cho (2006) reported, some of our participants acknowledged the fraud cases between North Korean refugees related to a job referral. Some participants also remarked that the information shared among North Korean refugees is not good enough. Yet, generally, participants gained more information from North Korean refugees and valued the information. This finding also leads to the need for further research about the level of trust and the contradictory perception of information sharing within an ethnic group.

North Korean refugee information behaviour model

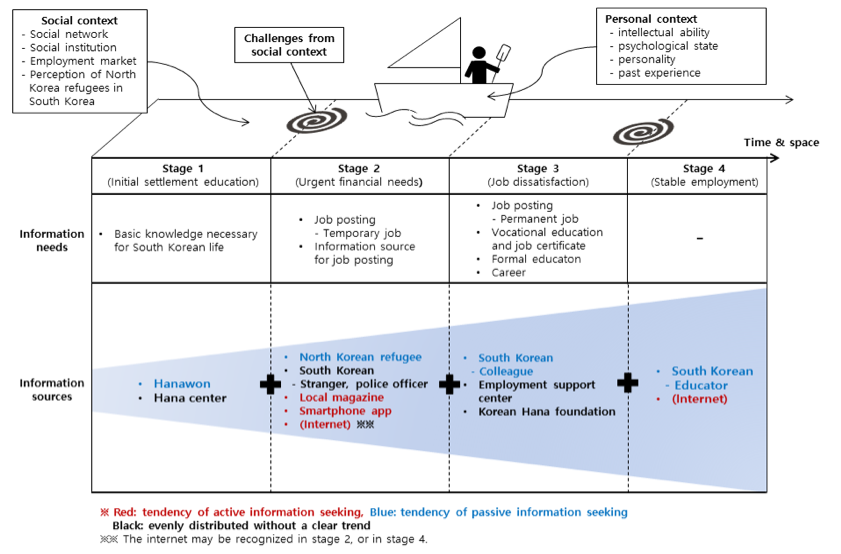

Based on the above findings, we could observe that the type of information needs and behaviour change as the settlement process of North Korean refugees advances, rather than changing based on demographic factors such as age, gender, or length of settlement. This study identified four employment stages of North Korean refugees based on its analysis, which are like the three stages of transitioning, settling in, and being settled described by Kennan et al. (2011):

- Initial settlement education: most North Korean refugees construct basic knowledge necessary for South Korean life through the initial settlement education of Hanawon and the Hana Centre, and they form a social network among other North Korean refugees.

- Urgent financial needs: after the initial settlement course is over, North Korean refugees usually face an urgent financial need. As a result, they try to find a temporary job to earn living expenses as soon as possible. They also require information sources to search for job postings. During this stage, small-scale social networks among refugees, the Internet, and local magazines are used as their information sources.

- Job dissatisfaction: after experiencing the labour market in South Korea, many refugees feel dissatisfied with their working environment. They feel more information needs than in the previous stage, such as those related to their career, postings of better jobs, permanent jobs, vocational education, and job certificates. In this stage, refugees use South Koreans and other North Korean refugees as information sources and tend to use information related to vocational education provided by public institutions.

- Stable employment: Based on the information acquired in the previous stages, refugees now have a regular job, vocational education, and possibly even formal education. As a result, their information needs are reduced. South Korean educators are the information sources added in this stage. In addition, refugees who were not able to utilise information technology improve their skills and use the Internet as an information source. However, the stability is not permanent; sometimes, refugees in the fourth stage fall back into the third stage owing to changes in the company’s financial situation or personal situation.

Immediately after North Korean refugees arriving in South Korea, they may have difficulties in information seeking because of psychological, intellectual, physical, and social barriers. Gradually, information literacy and social networks are developed in the process of participating in work and education, and as a result, they have better access to information. Thus, even if the refugees sometimes return to the former stage of job dissatisfaction, it is presumable that they will cope with their information needs by employing their newly obtained information sources from the stable employment stage. However, in other words, when the situations, such as health issues, child fostering, or family caregiving, prohibit participants from participating in work or education, participants had more difficulties in improving their information accessibility. To stop a vicious cycle of information inaccessibility and dire situation, the public libraries' role is to actively provide information and opportunities to widen their social networks.

In conclusion, we found that the information needs and behaviour of North Korean refugees change based on their situation. It is essential for information studies to examine the situations that refugees face. Based on our findings, the information behaviour of refugees is expressed as in Figure 1.

This model is built upon Dervin’s (1983) sense-making theory, which shows the information seeking process in terms of time and space. At the top of the figure, the person on the boat, which represents personal context, sails on a river that symbolises time and space. In the river, there is social context such as social institutions and the perception of North Korean refugees in South Korea, which affects information seeking. The navigator aboard the boat has an oar to paddle strenuously in the desired direction (active information seeking), but sometimes they receive help from waves (passive information seeking). Or the navigator may encounter with turmoil in the river (challenges of information seeking caused by social context). In this situation, some escape from the turmoil by oaring or by the help of waves. Unfortunately, some must stay in turmoil if they do not have enough skill or help. As stated earlier, North Korean refugees experience four stages of situations overtime after they arrive in South Korea, and they have different information needs depending on their situation. The table at the lower part of Figure 1 illustrates these situations, needs, and behaviour related to employment information. The first row represents the key information needs of each stage, and the second row describes the information sources that are newly added at each stage.

Implications for public libraries

Based on the above findings, this study suggests that public libraries provide proper employment information services to North Korean refugees at each stage. Among the four situations related to the employment of North Korean refugees, we focus on suggesting information services for people at stages 1-3, where they experience higher barriers to information seeking.

First, the prominent characteristic of the stage of initial settlement education is that the refugees do not have clear information needs. Therefore, it would be desirable to provide a brief but important notification about libraries. For example, librarians can create a connection with North Korean refugees by participating in the initial settlement programme and notifying them that public libraries can be used as information sources. In the case of rural areas where physical accessibility to the Hana Centre is limited, public libraries might play a major role as information sources for refugees. In addition, to improve psychological accessibility, librarians who also fled North Korea and received education after resettling in South Korea as refugees should attend the settlement programmes and provide information about public libraries. In this study, we observed that some participants formed a friendly relationship when public workers providing services to them were also from North Korea, and Tso (2007) found that librarians who have cultural or ethnic similarities with users provide a greater sense of trust in library services. Therefore, we suggest that public libraries should employ at least one librarian from North Korea to provide information services to refugees.

In the stage of urgent financial needs, refugees desperately search job postings to become financially secure, but they face various difficulties in information seeking such as lack of a social network, knowledge about information sources, and skills required to use information technology. Therefore, it is necessary to help them overcome the challenges in finding job postings. For example, public libraries can offer information literacy programmes that focus on basic computer skills, which can help refugees to find employment information on the Internet and to write a resume with a computer. Moreover, public libraries can provide a list of useful information sources and specific training on search methods to find job postings. Moreover, public libraries should provide information technology and a place to use the equipment. According to the 2017 Report on the Digital Divide, 59.4% of North Korean refugees own a computer, which is significantly lower than the 82.6% PC ownership proportion of South Koreans (Korea. Ministry of Science and ICT and Korea National Information Society Agency, 2017). This means that approximately 40% of North Korean refugees are not able to access computers.

For refugees in the third stage, i.e., job dissatisfaction, it would be best to provide them with information literacy education. Information literacy education focusing on the process of accessing, evaluating, and using necessary information is required. By developing abilities for defining information needs and collecting and evaluating information from various sources, refugees will form a basis for handling job-related inquiries (Lau, 2006). The public library should also consider presenting a relevant collection of information to refugees in advance, including how to explore their career aptitude, common occupations for refugees, and learning materials for obtaining job certificates. Additionally, it would be desirable to provide library programmes that can support refugees to blend in with local communities. Librarians should consider developing a programme or club activity that both North Korean refugees and South Koreans can participate in, which will eventually aid refugees in finding more useful information about jobs from members of local communities.

Limitations and future research

Because this study applied nonprobability sampling, the findings from this study cannot be generalized to all North Korean refugees in South Korea. Especially, we acknowledge that our research participants slightly overrepresent the population who experienced higher education in South Korea. 10 participants (44%) were attending or graduated from a two-year technical college or a four-year university. This percentage is 16% higher than what has been reported in the 2017 Settlement Survey of North Korean Refugees in South Korea. It will be possible to derive more generalisable research results if quantitative or qualitative studies applying appropriate probabilistic sampling methods are conducted in the future. Furthermore, based on the results of these generalisable studies, detailed employment information service strategies for public libraries can be developed for refugees.

We also acknowledge that some responses from the participants which were based on old memories that happened many years ago may be inaccurate. To overcome this inaccuracy, we asked as many clarification questions as possible. However, to obtain more accurate data based on recent memories, future research that applies diary methods or interview with a job seeker would be helpful.

Conclusion

This study investigated North Korean refugees’ employment-related information needs and behaviour, which have only previously been studied as part of everyday information needs and behaviour, by conducting semi-structured group interviews with twenty-three refugees. We presented four situations related to employment, information needs, and information behaviour and suggested information service guidelines for a public library that are suitable for each stage. The empirical data of this study will provide a basis for public libraries to provide information services to underrepresented groups of citizens, such as North Korean refugees.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2019S1A5C2A03083499).

About the authors

Jieun Yeon is currently a doctoral student at Syracuse University's School of Information Studies (iSchool). She holds her M.A. in Library and Information Science at Yonsei University. Her research focuses on the role and value of libraries in public libraries, library management, and information behaviour. Before joining the Syracuse iSchool, she worked as a research performance management librarian at Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology and a reference librarian at Seoul National University. She can be contacted at: jiyeon@syr.edu

Jee Yeon Lee is a professor at the Dept. of Library and Information Science, Yonsei University, Seoul, South Korea. She received her PhD in Information Transfer from Syracuse University, MLS in Library and Information Science at UCLA, and BA in Library Science at Yonsei University. Her research interests include human computer interaction, information behaviour, and digital libraries. She is currently working as the director of the Research Institute for Academic Library Development, funded by the Korean Ministry of Education. She published around 80 research papers and conducted more than 80 funded research projects.

References

Note: A link from the title is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Atiso, K., Kammer, J., & Adkins, D. (2018). The information needs of the Ghanaian immigrant. Information and Learning Sciences, 119(5/6), 317-329. https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-02-2018-0013

- Bronstein, J. (2017). Information grounds as a vehicle for social inclusion of domestic migrant workers in Israel. Journal of Documentation, 73(5), 934-952. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-02-2017-0023

- Caidi, N., & Allard, D. (2005). Social inclusion of newcomers to Canada: an information problem? Library & Information Science Research, 27(3), 302-324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2005.04.003

- Caidi, N., Allard, D., & Quirke, L. (2010). Information practices of immigrants. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 44(1), 491-531. https://doi.org/10.1002/aris.2010.1440440118

- Cannon, L. W., Higginbotham, E., & Leung, M. L. A. (1988). Race and class bias in qualitative research on women. Gender & Society, 2(4), 449–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124388002004003

- Case, D. O., & Given, L. M. (2016). Looking for information: a survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behavior. (4th ed.). Emerald.

- Chae, J. M., & Yhi, J. H. (2004). North Korea-South Korea cultural heterogeneity in psychological perspective: focusing on the North Korean defectors` adaptation. The Korean Journal of Culture and Social Issues, 10(2), 79-101.

- Chatman, E. A. (1986). Diffusion theory: a review and test of a conceptual model in information diffusion. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 37(6), 377-386. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(198611)37:6<377::AID-ASI2>3.0.CO;2-C

- Chatman, E. A. (1987). Opinion leadership, poverty, and information sharing. RQ, 26(3), 341–353.

- Chatman, E. A. (1996). The impoverished life-world of outsiders. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 47(3), 193-206. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199603)47:3<193::AID-ASI3>3.0.CO;2-T

- Cho, Y. I. (2008). Intercoder reliability. In P.J. Lavrakas (Ed.). Encyclopedia of survey research methods (pp. 345-346), Sage Publications.

- Cho, Y. W. (2006). Information behavior and information poverty of North Korean refugees. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Pusan National University, Busan, Korea.

- Choe, M. A., Yi, M., Choi, J. A., & Shin, G. (2012). Health knowledge, health promoting behavior and factors influencing health promoting behavior of North Korean Defectors in South Korea. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 42(5), 622-631. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2012.42.5.622

- Dervin, B. (1973). Information needs of urban residents: a conceptual context. In E. S. Warner, A.D. Murray, & V.E. Palmour, (Eds.). Information needs of urban residents final report. (pp. 8-42). U.S. Bureau of Libraries and Learning Resources. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED088464.pdf. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20211011001055/https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED088464)

- Dervin, B. (1983). An overview of sense-making research: concepts, methods, and results to date. [Paper presentation]. International Communication Association Annual Meeting, Dallas, TX, May 1983. http://faculty.washington.edu/wpratt/MEBI598/Methods/An%20Overview%20of%20Sense-Making%20Research%201983a.htm. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3xvJ75z)

- Dervin, B. (1992). From the mind’s eye of the user: the sense-making qualitative-quantitative methodology. In J. D. Glazier & R. R. Powell (Eds.). Qualitative research in information management (pp. 61-84). Libraries Unlimited. https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/bitstream/handle/2142/2281/Dervin1992a.htm. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/317MpQi)

- Dervin, B., & Clark, K. (1987). ASQ: asking significant questions. alternative tools for information need and accountability assessments by libraries. Peninsula Library System for California State Library. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED286519. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20211011010448/https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED286519)

- Dunne, J. E. (2002). Information seeking and use by battered women: a "person-in-progressive-situations" approach. Library & Information Science Research, 24(4), 343-355. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-8188(02)00132-9

- Fisher, K. E., Durrance, J. C., & Hinton, M. B. (2004). Information grounds and the use of need‐based services by immigrants in Queens, New York: a context‐based, outcome evaluation approach. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 55(8), 754-766. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20019

- Fisher, K. E., Marcoux, E., Miller, L. S., Sánchez, A., & Cunningham, E. R. (2004). Information behaviour of migrant Hispanic farm workers and their families in the Pacific Northwest. Information Research, 10(1), paper 199. http://www.informationr.net/ir/10-1/paper199.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3I0PLWh)

- Goulding, A. (2001). Information poverty or overload? Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 33(3), 109-111. https://doi.org/10.1177/096100060103300301

- Greifeneder, E. (2014). Trends in information behaviour research. In Proceedings of ISIC, the Information Behaviour Conference Leeds, 2-5 September, 2014: Part 1, (paper isic13). http://informationr.net/ir/19-4/isic/isic13.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3p0Ovde)

- Hannides, T., Bailey, N., & Kaoukji, D. (2016). Voices of refugees: information and communication needs of refugees in Greece and Germany. BBC Media Action. http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/mediaaction/pdf/research/voices-of-refugees-research-report.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3riddZu)

- Harris, R. M. (1988). The information needs of battered women. RQ, 28(1), 62-70.

- Henry, A. (2012). The employment information needs of people with intellectual disabilities. (Unpublished Master's thesis). Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand

- Jaeger, P. T., & Thompson, K. M. (2004). Social information behavior and the democratic process: information poverty, normative behavior, and electronic government in the United States. Library and Information Science Research, 26(1), 94-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2003.11.006

- Jeong, W. (2004). Unbreakable ethnic bonds: information-seeking behavior of Korean graduate students in the United States. Library & Information Science Research, 26(3), 384-400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2004.04.001

- Julien, H. E. (1999). Barriers to adolescents' information seeking for career decision making. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 50(1), 38-48. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(1999)50:1<38::AID-ASI6>3.0.CO;2-G

- Jung, J. H., & Sohn, S. H. (2015). Economic adaptation of female defectors from North Korea: employment, income and consumption. Seoul National University Press.

- Kennan, M. A., Lloyd, A., Qayyum, A., & Thompson, K. (2011). Settling in: the relationship between information and social inclusion. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 42(3), 191-210. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2011.10722232

- Khoir, S., Du, J. T., & Koronios, A. (2015a). Everyday information behaviour of Asian immigrants in South Australia: a mixed-methods exploration. Information Research, 20(3), paper 687. http://www.informationr.net/ir/20-3/paper687.html. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3p4m8Lj)

- Khoir, S., Du, J. T., & Koronios, A. (2015b). Linking everyday information behaviour and Asian immigrant settlement processes: towards a conceptual framework. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 462), 86-100. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2015.1024303

- Kim, S. (2010). Tackling the social exclusion of the North Korean refugees in South Korea. Korea Observer, 411), 93.

- Koo, J. H. (2016). Information-seeking within negative affect. Journal of the Korean Society for Library and Information Science, 50(1), 285-312. https://doi.org/10.4275/KSLIS.2016.50.1.285

- Korea Hana Foundation. (2018). 2017 Settlement survey of North Korean refugees in South Korea. Korea Hana Foundation. https://northkoreanrefugee.org/eng/resources/research.jsp (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3I3HyRd)

- Korea. Ministry of Science and ICT & Korea National Information Society Agency. (2017). The report on the digital divide. [In Korean]. Ministry of Science and ICT, National Information Society Agency. https://www.nia.or.kr/site/nia_kor/ex/bbs/View.do?cbIdx=81623&bcIdx=19480&parentSeq=19480 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3FXzSxY)

- Korea. Ministry of Unification. (2017). Manual for the resettlement support for North Korean refugees. [In Korean]. Ministry of Unification Resettlement Support Team. https://bit.ly/3p4oOZn (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3re6Eqz)

- Korea. Ministry of Unification. (2018). North Korean refugee policy. https://www.unikorea.go.kr/unikorea/business/statistics/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/32H0lli)

- Lankov, A. (2006). Bitter taste of paradise: North Korean refugees in South Korea. Journal of East Asian Studies, 6(1), 105-137. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1598240800000059

- Lau, J. (2006). Guidelines on information literacy for lifelong learning. IFLA. https://repository.ifla.org/bitstream/123456789/193/1/ifla-guidelines-en.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3p9Ao5f)

- Lee, E. (2017). A qualitative study on female North Korean defectors' experience of vocational education and job-seeking strategies. [In Korean] Korea Science & Art Forum, 27, 173-189. http://dx.doi.org/10.17548/ksaf.2017.01.27.173

- Lee, M. W. (2016). Micro language planning for refugee resettlement language support programs: the case of North Korean refugees in South Korea. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 25, 743–752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-016-0308-z