Post-truth era: news behaviour and news literacy skills of university librarians

Kanwal Ameen and Salman Bin Naeem

Introduction. This study was conducted with an objective to determine the ways librarians deal with fake news, as well as to assess the status of their news literacy skills in combating the fake news phenomenon.

Method. A cross-sectional survey was conducted in public and private sector university libraries of Punjab, Pakistan. The study’s population comprised of university librarians working at the rank of an assistant librarian or above.

Analysis. One hundred and eighty questionnaires were distributed in both print and online out of which 128 were returned (response rate 71.11%).Descriptive and inferential statistics were applied to report the data using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS-version 22).

Results. Librarians ‘sometimes’ determine the authenticity of news story e.g., ‘check it from other sources in case of doubts.’ The responses for all the eleven statements relating to news literacy skills ranged between 3.05 to 3.36 on a five-point Likert type scale, indicating that respondents ‘somewhat’ agreed with their perceived news literacy skills.

Conclusions.University librarians are not fully acquainted with the aspect of news trustworthiness on social media, which affects their news acceptance and sharing behaviour. They also have a moderate level of conceptual understanding of news literacy.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper921

Introduction

The term ‘post-truth’ was declared as an international word of the year by Oxford Dictionaries in 2016 (Berghel, 2017). It refers to an era in which audiences are likely to believe information that appeals to their emotions and personal beliefs, as opposed to information that is regarded as factual and or objective (Maoret, 2017). The hallmark of the post-truth era is that people’s perceptions and opinions are being shaped by socially constructed facts. Information on social media is growing rapidly in different forms, making it easier to connect to people.

As a result, the abundance of information on social media without any check on its authenticity makes it difficult for an individual to distinguish between facts, opinions, propaganda, biasness and fakeness in a piece of information. There is a huge increase in such stories on social media that initially appear credible and prove false or fabricated later; however, by the time they prove false, the damage is hardly reversible. Furthermore, it creates confusion in people’s minds about the trustworthiness of news sources. Thus, it becomes vital to educate people generally, and youth especially, about the nature of fake news and the negative outcomes of sharing such news.

Librarians for a long period of time have been concerned about careful and critical evaluation of information and provision of information literacy instructions (Hernadez, 2018; Connaway et al., 2017). Therefore, the post-truth era grabbed their attention. When the term ‘post -truth’ was declared as a word of the year in 2016 by the Oxford Dictionaries, we as librarians realized that action is needed to educate and advocate the importance of critical thinking- an essential skill when navigating the information (IFLA, 2016). As a result, IFLA created a guideline on ‘how to spot fake news’ with eight simple steps, which became the primary reference for librarians to identify the validity of a news story. The steps are: (i) consider the source, (ii) check the author, (iii) check the date, (iv) check your biases, (v) read beyond, (vi) supporting sources, (vii) is it a joke? and (viii) ask the experts. Wineburg (2016) emphasized that libraries and information professionals should play a vital role in sensitising students in this regard so that they can identify the agenda or bias of the writer and the authenticity of news itself.

A few studies have indicated that librarians have a central role to play in the fight against fake news (e.g., Finley et al., 2017; Batchelor, 2017; American Library Association, 2017). Others have established that libraries were already engaged (Jacobson, 2017; Neely-Sardon and Tignor, 2018; Wade and Hornick, 2018),and responded strenuously to the challenges of fake news in the post-truth era (Sullivan, 2019). Libraries have put together guides to help students, staff, and faculty to sort through what is fake news and how to recognize it (Stein-Smith, 2017; Hernadez, 2018).

This study aims to assess the news behaviour and news literacy skills of academic librarians while determining how they deal with fake news.. We assumed that the findings will promote an awareness on the effective role of librarians in providing news literacy instructions in the developing countries such as Pakistan. The findings may be useful in sensitising the university, and other librarians about their own news behaviourand level of news literacy skills.

Defining fake news and news behaviour

The literature mentions various concepts related to fake news such as penny press, jazz journalism, and yellow journalism- the use of sensational headlines, rather than factual news, to capture a reader’s attention (Campbell, 2019), and "The Hun" to provoke negative emotion (Deisel, 2017). However, for the present study we take it as a generalised term and all the other terms associated with fake news such as misinformation, disinformation, mal-information, and propaganda or the terms given in Table 2. ‘News behaviour’ is used also as a broader phrase i.e., all one’s behaviour patterns related to news seeking, obtaining, finding, analysing, keeping and sharing.

Literature review

The literature for this study was searched through various databases of scholarly information resources such as Web of Science, Scopus, the publishers Science Direct, Emerald, Wiley, and Taylor and Francis, the journal archive JSTOR, and Google Scholar. The keywords ‘news’, ‘fake news’, and ‘news literacy’ were used to search the literature and subscribe to article ‘alerts’. Most of the relevant literature was found in the areas of news literacy, categorization of descriptive sources of online fake news, social media as a platform to break fake news, the effect of fake news, and programmes of news literacy instruction in different settings.

Fake news is not a new phenomenon and has been with us for centuries (Floridi, 2016). Traditionally, tabloid newspapers were used to float fake news after the invention of the printing press but in the modern world, ‘click bait’ is a widely used method for the same old purpose with the modern way (Posetti and Matthews, 2018; Cooke, 2018). The era of yellow journalism, penny press, and jazz journalism are still with us in a new way and a different format, but the difference is that it is now quite recognizable (Cohen, 2000).

‘News literacy’ is the 21st-century term which requires critical-thinking skills for analysing and judging the reliability of news and information, differentiating between facts, opinions, and assertions in the media. It is a necessary component of a larger set of literacies needed in any contemporary society. Previously, a relatively broader term ‘media literacy’ was the most used term in relation to news literacy. News literacy has also been defined by Malik et al. (2013) as a set of integrated abilities to understand the role of news in society, the motivation to seek out news, to find, identify or recognize, critically evaluate and create news.

We find discussions lately among scholars and in the literature about the fake news phenomenon (Tandor et al., 2018; Cooke, 2018). It has emerged as a serious issue that is not only affecting information landscape flow (Figueira and Oliveira, 2017), but also becoming a major global risk (Shao et al., 2017), and a threat to democracy (Barthel et al., 2016).

The Council of Europe has refrained from using the term ‘fake news’ in its report on the ‘Information disorder: toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making’ for two reasons, (i) the term is woefully inadequate to explain the complex phenomena of information disorder, and (ii) it has begun to be used by the politicians to refer the news outlets whose news they find disagreeable harm (Wardle and Derakhshan, 2017).Hence, they presented the new conceptual framework, describing the three different types: misinformation, disinformation, and mal-information for assessing information disorder (Table 1). They used the dimensions of harm and falseness by describing the differences among the three types of information. Misinformation is described as unintentional mistakes such as inaccurate news without any intent to harm. On the other hand, disinformation or mal-information are fabricated or deliberate news that intends to harm (Wardle, 2016; Wardle and Derakhshan, 2017).

| Misinformation | Disinformation | Mal-information |

|---|---|---|

| False connection | False context | Leaks |

| Misleading content | Imposter content | Harassment |

| Manipulated content | Hate speech | |

| Fabricated content |

Wardle (2017) presented a framework of seven types of mis- and dis-information which is helpful to understand their nature (Table 2).

| Types | Description |

|---|---|

| Satire or parody | No intention to cause harm but potential to fool |

| Misleading content | Misleading use of information to frame an issue or individual |

| Imposter content | When genuine sources are impersonated |

| Fabricated content | News content is 100% false, designed to deceive and do harm |

| False connection | When headlines, visuals or captions don’t support the content |

| False context | When genuine content is shared with false contextual information |

| Manipulated ontent | When genuine information or imagery is manipulation to deceive |

Any one or all types together provide a basis for fake news. According to Berghel (2017), the sources of online fake news can be categorised into three broad types: (i) disclosed sources: which can easily be recognized and hide behind the freedom of speech, (ii) anonymous sources: tend to always be concealed within a newsgroup, and (iii) bogus sources: that are truly covert operations.

There is a world-wide concern over the circulation of fake news and its effects on political, economic, and social well-being (Vosoughi et al., 2018). Many studies reported that social media outlets are contributing towards undermining the facts and manipulating peoples’ opinions (Head el al., 2018; Batchelor, 2017; Barthel et al., 2016). The rapid growth of factually inaccurate information and circulation of alternative facts on social media sites, such as Twitter and Facebook make it difficult to distinguish between fake and real news. This is not only jeopardizing the media industry but also affecting the minds of young people, who may consider all the information they receive through media as correct, which may influence their decision making processes (Sirajudeen et al., 2017). A large-scale survey revealed that the majority of U.S. adults (64%) admitted facing a great deal of confusion about the basic facts of current events because of the spread of fake news (Barthel et al., 2016).

During the 2016 Presidential election in the US, everyone from Pope Francis to President Obama expressed their concerns about fake news and its potential impacts on sabotaging the election results (Barthel et al., 2016). After a year, a survey revealed that fake news stories were shared thirty million times on Facebook to support a political candidate just three months before the General Election in the US (Allcott and Gentzkrow, 2017). As a result, fake news outperformed real news on Facebook in the months of the election (Silverman, 2016). The Pew Research Center found that nearly a quarter (23%) of U.S. adults were involved in sharing fake news on social media, whether knowingly or unknowingly (Barthel et al., 2016). The problem of fake news spread gets more severe when a study found, after critically evaluating 400 thousand tweets, the use of social bots in the spread of fake news (Shao, et al., 2017).

The fight against online fake news continues and Facebook and other social media channels have been part of this fight for the last two years (Ortutay, 2018). The European Union authorities directed social media channels including Google, Twitter, and Facebook to submit monthly reports on their efforts to eradicate ‘fake news’ campaigns ahead of the elections for the European Parliament (AP News, 2018). As a result, Facebook recently shut down Italian pages and accounts that were spreading misleading news ahead of European Union parliamentary elections (Chan and D’Memilio, 2019). Further to this, Spain joined the Europe-wide efforts to fight against online fake news, in order to shield their general election from cyberattacks (AP News, 2019). Singapore has recently passed a law allowing the government to treat spreading fake news as a criminal offense, to jail offenders for up to 10 years, and to block accounts spreading fake news (AP News, 2019). Efforts are being made by individuals, various libraries and agencies to prevent the spread of fake news on social media e.g., Facebook has recently set up a ‘war room’ to prevent the spread of fake news (Samaa, 2018). The government of Pakistan has recently launched ‘Fake News Buster’ account on Twitter to expose fake news (Dawn, 2018). Several Websites have also been developed that help detect fake news such as AP News, and Fake News Challenge. However, these steps are insufficient preventing the spread of fake news.

During the 20th century, information literacy and media literacy were distinct literacies under different disciplines such as the library and information science, and media studies. Hence, in the 21st century, the UNESCO introduced the interdisciplinary literacy approach using the evolving construct ‘media and information literacy’ by integrating the media literacy and information literacy, under which all the other types of literacies are linked such as digital literacy, ICT literacy, information literacy, media literacy, and news literacy (UNESCO, 2019a).

More recently, UNESCO along with its partners launched a ‘MIL CLICKS’ (Media and information literacy (MIL), critical thinking and creativity, literacy, intercultural, citizenship, knowledge, sustainability) movement to raise awareness about using the social media wisely, creatively, and critically, as well as looking-up, creating, and sharing relevant contents using #MILCLICK, and becoming a MIL CLICKER (UNESCO, 2019b).

The phenomenon of fake news has grabbed the attention of libraries, and there is a growing awareness about the significant role librarians can play in combating fake news. One such programme, was launched at the Giovatto library of Fairleigh Dickinson University, where librarians and staff work together to empower students with the skills they require to differentiate between fake and real news in order to protect them from being influenced by opinion or agenda (Stein-Smith, 2017). Librarians at the University of Oregon have also developed a research guide and instructional programme to counteract the effect of fake news. This is a comprehensive guide with four distinct sections that help users to develop evaluative skills in relation to fake news. Following the successful launch of this guide and overwhelming response from students and staff, the university library has conducted an interactive workshop on news literacy in which an instructional exercise forms the foundation of the workshop (Hernandez, 2018). Media literacy programmes are also helping to promote news media literacy among teenagers (Kleemans and Eggink, 2016).

The literature review concludes that most studies on ‘fake news’ are conducted by researchers in the field of journalism and mass communications, using their own framework of ‘media literacy.’ Moreover, the application of such a framework in order to make students able to differentiate between fake, false and real news has rarely been found in university settings, until now. Library and information professionals have identified this gap and expanded information literacy initiatives to address news literacy instruction. The literature review further indicates that most of the literature on ‘fake news’ was published after the 2016 Presidential Election in the US.

There is a gap in the published literature in terms of empirical studies on news literacy skills and the role of library and information professionals. In the context of developing countries like Pakistan, this subject has been hardy addressed in an empirical manner. Therefore, the present study will serve as foundation for further research in the news behaviour and news literacy skills of academic librarians.

Research method

The quantitative research design based on a cross-sectional survey of the selected public and private sector university libraries of the Punjab province, Pakistan was used to achieve the study’s objectives. The population consisted of regular librarians working as either assistant librarian or on higher professional positions in the university libraries.

Data collection instrument and method

A six-part structured questionnaire was developed after reviewing the current body of relevant literature on news literacy (Wardle and Derakhshan, 2017; Lazer, et al., 2018; Spratt and Agosto, 2017; Reis, et al., 2019; Flintham, et al., 2018), media literacy (Anderson, et al., 2008; Maksl, et al., 2015, 2017), and information literacy (Neely-Sardon and Tignor, 2018; Pennycook and Rand, 2019). The six parts are as follows: (1) the news sharing behaviour using social media channels; (2) determining the trustworthiness of various news sources; (3) reasons behind publishing fake news; (4) practices of determining the authenticity of a news story; (5) librarians’ news literacy skills; and (6) demographic information. Overall, the questionnaire comprised of forty-four statements and six sections.

The draft questionnaire was sent for content validation to three experts from the fields of library and information management, and mass media communication. It was pilot tested on a sample of fifteen respondents and their suggestions were incorporated in the questionnaire. The internal consistency and content reliability of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients; (the score ranged from 0.727 to 0.926, indicating good reliability of the questionnaire).

A team comprising of three members having library and information science education was hired for data collection. They were instructed about the survey instrument and data collection process. Their primary role was to visit each participating university to collect data from the participants and to help in obtaining a high response rate.

Sampling

Punjab is the largest province of Pakistan and to collect data from the widely dispersed population using self-administered questionnaires technique was difficult. Therefore, first, the universities from its six main divisions, Bahawalpur, Dera Gazi Khan, Faisalabad, Lahore, Multan and Sargodha were selected. Then, according to Higher Education Commission (HEC) ranking 2019 ( https://www.hec.gov.pk), from higher to lower ranked universities were selected to collect data. Finally, the availability of their librarians was checked through personal contacts for administering the questionnaire with the help of our team. The data were collected from librarians working in central libraries. However, two participating universities had independent departmental or seminar libraries and data were also collected from them. A data collection team visited twice in each participating library to collect the data from those participants who were available and accessible during team visits. Furthermore, to expand the range of the sample, an online version of the questionnaire was sent to those participants who were in distant areas using a Google survey. Table 3. indicates that overall 180 questionnaires were distributed personally and through e-mail, out of which 128 completed questionnaires were returned (response rate of 71.11%). These responses were validated and used for analysis.

| Questionnaire distributed methods | Questionnaires distributed | Questionnaires returned | Response rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Face-to-face | 130 | 98 | 75.38% |

| Virtually (Online) | 50 | 30 | 60.00% |

| Total | 180 | 128 | 71.11% |

Data analysis procedure

The collected data were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS-version 22) after coding and cleaning. Missing values in responses were replaced by using the ‘expectation maximization’ method– it is an effective technique that is used in data analysis to manage missing values (Aktas et al., 2019). The non-parametric statistical test Mann-Whitney U was applied to determine the significant differences, if any, between the opinion of librarians working in public and private sector university libraries in their use of social media channels to share news (Table 5), their level of trustworthiness about the news sources (Table 6), their opinion about why fake news is published on social media (Table 7), and their perceived news literacy skills (Table 8). The reason behind using non-parametric statistics was the type of data that did not meet the underlying assumptions of parametric statistics due to as the statically uneven distribution of data with outliers.

Findings

The following section elaborates the findings related to main questions of the study using descriptive and advance statistics

Respondents’ demographic information

Demographic information (Table 4) shows that most of the respondents are male from public sector university libraries. Using a chi-squared analysis, we found no significant difference in the sex distribution of male and female respondents working in public and private sector university libraries (χ2 (1) = .004, P = 0.550, Phi = 0.005). The difference by sex was much higher in public sector university libraries than in the private sector. The age group with the highest number of librarians was 31–40 years. Many of the librarians were aged less than 40 years. A significant difference existed with a small effect size across the different age groups of librarians working in public and private university libraries (χ2 (3) = 9.249, P = 0.026, Cramer’s V = 0.269). Most respondents in the older age groups were from public sector university libraries as compared to private university libraries. In our cohort, the respondents were mostly working as librarians followed by assistant librarians. A significant difference found with a small effect size across the different working designations of respondents from public and private university libraries (χ2 (3) = 11.386, P = 0.010, Cramer’s V = 0.298). The category of ‘professional qualification’ with the most librarians was ‘masters degree’.

A statistically significant difference with a medium effect size is found in the professional experience of librarians working in public and private sector university libraries (χ2 (4) = 13.850, P = 0.008, Cramer’s V = 0.329). Librarians working in public sector universities were more experienced than the librarians of private sector university libraries.

| Variable | Public universities | Private universities | Total | χ2 value | p-value | Phi Φ | Cramer’s V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 52 (40.6%) | 27 (21.1%) | 79 (61.7%) | 0.004 | 0.550 | 0.005 | |

| Female | 32 (25.0%) | 17 (13.3%) | 49 (38.3%) | ||||

| Respondents’ age | |||||||

| <30 years | 21 (16.4%) | 21 (16.4%) | 42 (32.8%) | ||||

| 31-40 years | 40 (31.2%) | 19 (14.8%) | 59 (46.1%) | ||||

| 41-50 years | 17 (13.3%) | 3 (2.3%) | 20 (15.6%) | 9.249 | 0.026* | 0.269 | |

| >50 years | 6 (4.7%) | 1 (0.8%) | 7 (5.5%) | ||||

| Working designation | |||||||

| Chief Librarian | 6 (4.7%) | 5 (3.9%) | 11 (8.6%) | ||||

| Deputy Chief Librarian | 13 (10.2%) | 2 (1.6%) | 15 (11.7%) | ||||

| Librarian | 46 (35.9%) | 16 (12.5%) | 62 (48.4%) | 11.386 | .010* | .298 | |

| Assistant librarian | 19 (14.8%) | 21 (16.4%) | 40 (31.2%) | ||||

| Professional qualification | |||||||

| Master | 45 (35.2%) | 27 (21.1%) | 72 (56.2%) | ||||

| M. Phil | 34 (26.6%) | 15 (11.7%) | 49 (38.3%) | 0.724 | 0.696 | 0.075 | |

| PhD | 5 (3.9%) | 2 (1.6%) | 7 (5.5%) | ||||

| Professional experience | |||||||

| < 5years | 18 (14.1%) | 21 (16.4%) | 39 (30.5%) | ||||

| 6-10 years | 22 (26.2%) | 13 (10.2%) | 35 (27.3%) | ||||

| 11-15 years | 19 (22.6%) | 5 (3.9%) | 24 (18.8%) | 13.850 | 0.008* | 0.329 | |

| 16-20 years | 13 (15.5%) | 1 (0.8%) | 14 (10.9%) | ||||

| > 20 years | 12 (14.3%) | 4 (3.1%) | 16 (12.5%) | ||||

| * Level of significance < 0.05 Phi and Cramer’s V effect size: 0.1 small, 0.3 medium, 0.5 large. | |||||||

News behaviour

RQ1. Which social media channels are frequently used by librarians to share news?

The respondents were given a list of six social media channels and asked to indicate the usage frequency of these channels to share news. Table 4 shows that out of six social media channels, only one received a mean score around 4, indicating that a majority would often use ‘WhatsApp’ to share news followed by ‘Facebook’ (M=3.46) and ‘Google+.’ However, they were rarely using ‘Twitter’, ‘Instagram’ and ‘Snapshot’ for sharing news stories.

Using a Mann-Whitney U statistics we found p-values of all the six social media channels greater than the pre-set alpha value of 0.05, indicating statistically no significant difference in the frequency of use of social media channels to share news between librarians of the two groups (Table 5).

| Universities | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Private | ||||||||||

| Items | Always | Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | Mean | SD | Mean Rank | Mean Rank | Mann–Whitney U | P-value |

| 43.7% | 27.8% | 13.5% | 8.7% | 6.3% | 3.94 | 1.222 | 60.71 | 68.69 | 1575.500 | 0.216 | |

| 28.8% | 25.6% | 20.0% | 13.6% | 120.0% | 3.46 | 1.353 | 58.71 | 70.90 | 1434.500 | 0.065 | |

| Google+ | 19.5 | 20.3% | 14.8% | 19.5% | 25.8% | 2.88 | 1.488 | 68.63 | 56.63 | 1501.500 | 0.075 |

| 8.3% | 14.9% | 14.0% | 19.0% | 43.8% | 2.25 | 1.368 | 60.89 | 61.20 | 1668.500 | 0.961 | |

| 4.1% | 16.5% | 9.1% | 19.0% | 51.2% | 2.03 | 1.284 | 60.08 | 62.60 | 1623.500 | 0.681 | |

| Snapshot | 7.4% | 14.8% | 10.7% | 6.6% | 60.7% | 2.02 | 1.408 | 62.72 | 59.33 | 1620.500 | 0.562 |

| Scale: 5= Always, 4= Often, 3= Sometimes, 2= Rarely, 1= Never Level of significance < 0.05'. | |||||||||||

RQ 2. How often do you encounter a fake news story on social media?

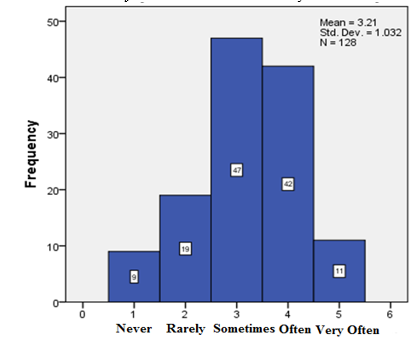

The respondents were asked about the frequency of encountering a fake news story on social media. Figure 1 indicates that 53 (41%) either ‘often’ or ‘very often’ encounter a fake news story. However, 66 (52%) indicated that they either ‘sometimes’ or ‘rarely’ encounter a fake news story on social media.

Figure 1: How often do you encounter a fake news story on social media?

RQ 3. What is the level of trustworthiness among librarians about the news sources?

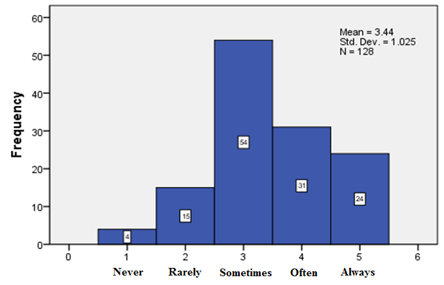

The respondents were asked a question about the trustworthiness of a news story and the way it matters to them while reading it on social media. Figure 2 shows that 55(43%) respondents indicate that the trustworthiness of a news story matter either ‘always’ or ‘often’ to them. However, 69 (54%) reported that its trustworthiness matter to them either ‘sometimes’ or ‘rarely’.

Figure 2: While reading a news on social media, does its trustworthiness matter to you?

The respondents were given a list of five news sources in order to identify their level of trustworthiness about these sources. Table 6 shows that 73.5% of the responses considered print (e.g., newspapers) and 65.6% considered electronic (e.g., radio, TV, cable) sources as ‘almost always’ or ‘often’ trustworthy news sources while social media feeds (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) got only 36.7% responses in the same category. It shows that the respondents still rate the newspapers comparatively the most authentic source of a news. The blogs got the lowest mean value in terms of trustworthiness.

Using Mann-Whitney U statistics, we found p-values of all these five news sources greater than the alpha value of 0.05 indicating no statistically significant difference in the level of trustworthiness about the news sources between librarians working in public and private sector universities.

| Universities | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Private | ||||||||||

| Media | Always | Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | Mean | SD | Mean Rank | Mean Rank | Mann–Whitney U | P-value |

| Print (e.g., newspapers) | 30.5% | 43.0% | 14.1% | 9.4% | 3.1% | 3.88 | 1.047 | 67.17 | 59.40 | 1623.500 | 0.232 |

| Electronic (e.g., radio, TV, cable) | 25.8% | 39.8% | 21.1% | 9.4% | 3.9% | 3.74 | 1.067 | 62.15 | 68.98 | 1651.000 | 0.300 |

| Friends/Peers etc | 8.7% | 39.4% | 33.9% | 8.7% | 9.4% | 3.29 | 1.062 | 64.64 | 62.78 | 1772.500 | 0.775 |

| Social media feeds (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) | 7.0% | 29.7% | 37.5% | 18.8% | 7.0% | 3.11 | 1.021 | 63.58 | 66.25 | 1771.000 | 0.686 |

| Blogs (Buzz Feed) | 4.0% | 22.2% | 25.4% | 22.2% | 26.2% | 2.56 | 1.210 | 62.80 | 64.80 | 1747.000 | 0.764 |

| Scale: 5= Almost Always, 4= Often, 3= Sometimes, 2= Rarely, 1= Never | |||||||||||

RQ4. What is the opinion of librarians about fake news publishing in social media?

The respondents were given a set of eight statements to indicate their opinions on fake news publishing on social media. Table 7 shows that mean value of all these statements ranges from 2.57 to 3.13. It indicates that fake news is ‘probably’ published to support a political or religious cause or agenda (M= 3.13) and to oppose a cause, political, or religious, etc. (M=3.05), and to trigger people to take some action (M=2.96), etc. ‘Just by ignorance’ got the lowest Mean value depicting respondents’ belief in the mal-intentions behind publishing fake news on social media.

Using a Mann-Whitney U statistics, we found a p-value lower than the alpha value of 0.05 in a statement that fake news is published ‘just by ignorance’ (U = 1396.5, p = 0.021, r = 0.20) indicating a statistically significant difference in the opinions of librarians working in public and private sector university libraries (Table 7). The respondents from the private university libraries were more certain that fake news is published ‘just by ignorance’ as compared to the respondents from public sector university libraries (Mean Rank: 73.76 vs 58.83). A statistically no significant difference is found in the opinion of librarians working in public and private sector university libraries about why fake news is published on social media (Mean Rank: Public University Libraries=58.60 vs Private University Libraries=71.09, U = 1426, p =0.065, r = 0.16).

| Universities | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Private | |||||||||

| Statements | Definitely Not | Probably Not | Probably Yes | Definitely Yes | Mean | SD | Mean Rank | Mean Rank | Mann–Whitney U | P-value |

| To support a cause (political, or religious, etc.) | 4.7% | 14.8% | 44.5% | 35.9% | 3.13 | .842 | 63.64 | 66.15 | 1775.500 | 0.696 |

| To oppose a cause (political, or religious, etc.) | 4.7% | 18.0% | 46.1% | 35.9% | 3.05 | .841 | 61.71 | 69.82 | 1614.000 | 0.208 |

| To trigger people to take some action | 4.0% | 18.3% | 56.3% | 21.4% | 2.96 | .763 | 61.49 | 67.25 | 1639.000 | 0.347 |

| To deceive people | 1.6% | 25.8% | 50.0% | 22.7% | 2.94 | .753 | 64.30 | 63.43 | 1801.000 | 0.890 |

| To advance a vested interest or agenda | 8.6% | 14.1% | 53.1% | 24.2% | 2.92 | .864 | 59.27 | 71.39 | 1457.000 | 0.051 |

| To confuse people | 5.5% | 18.8% | 57.0% | 18.8% | 2.91 | .798 | 62.45 | 68.41 | 1676.000 | 0.335 |

| Just for fun (or as a prank) | 15.0% | 22.8% | 46.5% | 15.7% | 2.64 | .966 | 58.25 | 70.23 | 1420.000 | 0.060 |

| Just by ignorance | 16.5% | 25.2% | 44.1% | 14.2% | 2.57 | .948 | 58.83 | 73.76 | 1396.500 | 0.021 |

| Scale: 4= Definitely Yes, 3= Probably Yes, 2= Probably Not, 1= Definitely Not | ||||||||||

RQ 5. How often do they determine the authenticity of a news story?

The respondents were asked a set of eleven statements in order to assess their frequency for determining the authenticity of a news story while reading it on social media (Table 8). Of the eleven statements, three received a mean value close to 4.0 indicating that respondents often ‘check the objectivity and reliability of the sources’ (M= 3.68), ‘check the home page to know more about the source’ (M= 3.63), and ‘check the validity of timings of the news’ (M= 3.58). However, eight statements received a mean score around 3.50, indicating that they fall between ‘sometimes’ and ‘often’ to determine the authenticity of news story e.g., ‘I check it on other sources in case of doubts’ (M=3.49), and ‘I check what others are saying about the news story’ (M= 3.46). The Table shows that even the last statement got the mean value of almost 3.0. It appears that they are considerably check the authenticity of a news story using various sources.

Using Mann-Whitney U statistics, we found p-values of all the eleven statements greater than the level of significance of 0.5 indicating no significant difference in the frequency of determining the authenticity of news story between librarians of public and private sector universities (Table 8).

| Universities | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Private | ||||||||||

| Statements | Always | Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | Mean | SD | Mean Rank | Mean Rank | Mann–Whitney U | P-value |

| I check the objectivity and reliability of the source | 17.5% | 46.8% | 25.4% | 7.1% | 3.2% | 3.68 | .952 | 62.68 | 65.02 | 1737.000 | 0.714 |

| I check the home page to know more about the source | 18.3% | 41.3% | 23.8% | 11.1% | 4.8% | 3.63 | 1.250 | 61.09 | 67.99 | 1606.500 | 0.289 |

| I check the validity of timings of the news | 16.4% | 43.3% | 25.8% | 9.4% | 4.7% | 3.58 | 1.024 | 64.78 | 63.97 | 1824.500 | 0.901 |

| I check it on other sources in case of doubts | 14.8% | 41.4% | 27.3% | 10.9% | 5.5% | 3.49 | 1.050 | 62.43 | 68.45 | 1674.000 | 0.359 |

| I check what others are saying about the news story | 15.7% | 33.9% | 34.6% | 12.6% | 3.1% | 3.46 | 1.006 | 66.00 | 60.23 | 1660.000 | 0.379 |

| I check that the credibility of the news source | 13.3% | 41.4% | 28.9% | 7.0% | 9.4% | 3.42 | 1.106 | 61.01 | 71.16 | 1555.000 | 0.122 |

| I share with other (e.g., colleague, peer, friend) to seek his/her opinion | 12.5% | 36.7% | 35.2% | 10.2% | 5.5 | 3.41 | 1.015 | 66.25 | 61.16 | 1701.000 | 0.438 |

| I search for the news source to see what else they’ve published | 12.5% | 35.9% | 34.4% | 12.5% | 4.7% | 3.39 | 1.014 | 62.05 | 69.18 | 1642.000 | 0.278 |

| I check the URL to see the reliability of a news story | 11.7% | 38.3% | 33.6% | 8.6% | 7.8% | 3.38 | 1.057 | 62.43 | 68.44 | 1674.500 | 0.360 |

| I make sure that the news is not given in a sarcastic manner | 9.4% | 37.8% | 34.6% | 12.6% | 5.5% | 3.33 | 1.000 | 61.89 | 67.98 | 1651.000 | 0.350 |

| I try to ask a media person, if possible | 7.8% | 30.5% | 26.6% | 15.6% | 19.5% | 2.91 | 1.249 | 62.00 | 69.27 | 1638.000 | 0.278 |

RQ6. What is the level of perceived news literacy skills among librarians?

As the goal was to determine the news literacy skills of the respondents, they were asked about rating their skills based on their self-perceptions by giving them a set of eleven statements. Table 9 shows that mean values of all the eleven statements ranged from 3.05 to 3.36 indicating that the respondents agreed ‘somewhat’ with the statements such as, ‘I am aware of my own bias and belief while reading news stories’ (M=3.36), ‘I know how to use searching techniques to get the needed information from the media’ (M=3.34), and ‘I am confident in my ability to judge the truth of a news item’ (M=3.33), etc. It shows that all related skills need to work on for attaining the desired knowledge of news literacy and news literacy skills to be able to play the role of instructor in this regard as ‘I have a good understanding of the concept of news literacy’ got the lowest Mean.

Using Mann-Whitney U statistics, we found p-values greater than the alpha value of 0.05 in all these statements indicating no statistically significant difference in the perceived news literacy skills between librarians working in public and private sector university libraries (Table 8).

| Universities | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Private | ||||||||||

| Statements | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Somewhat Agree | Agree | Strongly Agree | Mean | SD | Mean Rank | Mean Rank | Mann Whitney U | p-value |

| I am aware of my own bias and beliefs while reading news stories | 7.8% | 17.2% | 18.0% | 45.3% | 11.7% | 3.36 | 1.135 | 65.73 | 62.15 | 1744.500 | 0.583 |

| I know how to use searching techniques to get the needed information from the media | 13.3% | 10.2% | 18.0% | 46.1% | 12.5% | 3.34 | 1.220 | 67.33 | 59.10 | 1610.500 | 0.207 |

| I am confident in my ability to judge the truth of a news item | 3.9% | 21.1% | 21.9% | 44.5% | 8.6% | 3.33 | 1.028 | 62.46 | 68.40 | 1676.500 | 0.362 |

| I understand how news is made | 8.6% | 11.7% | 25.0% | 48.4% | 6.3% | 3.32 | 1.049 | 64.76 | 64.01 | 1826.500 | 0.908 |

| I can compare news across different media sources to determine its trustworthiness | 3.9% | 20.5% | 24.4% | 42.5% | 8.7% | 3.31 | 1.021 | 63.61 | 64.74 | 1793.500 | 0.862 |

| I am sensitive about the role of positive and negative effects of news contents on individuals. | 9.4% | 21.9% | 12.5% | 41.4% | 14.8% | 3.30 | 1.233 | 62.29 | 68.72 | 1662.500 | 0.330 |

| I have the skills to interpret news messages | 9.4% | 9.4% | 32.0% | 41.4% | 7.8% | 3.29 | 1.059 | 62.10 | 69.09 | 1646.000 | 0.284 |

| I am aware of the fact that malpractices may influence news content | 6.3% | 22.7% | 28.1% | 31.1% | 11.7% | 3.20 | 1.109 | 63.43 | 66.55 | 1758.000 | 0.640 |

| I am good at catching-up with the changes in the agenda of media | 12.5% | 16.4% | 30.5% | 32.8% | 7.8% | 3.07 | 1.145 | 62.58 | 68.16 | 1687.000 | 0.402 |

| I am often confused about the trustworthiness of news and information on social media | 5.5% | 26.6% | 32.0% | 28.1% | 7.8% | 3.06 | 1.041 | 67.89 | 58.03 | 1563.500 | 0.138 |

| Scale: 5= Strongly Agree, 4= Agree, 3= Somewhat Agree, 2= Disagree, 1= Strongly Disagree | |||||||||||

Discussion

Our findings reveal trends regarding use of social media channels and establishes that WhatsApp and Facebook are the frequently used for dissemination of news. The findings endorse the findings of previous studies (Kumpeg et al., 2015; and Mitchell and Page, 2014) that social media is not only used for social connections but also for publishing fake news on politics and religions, as well as to deceive people.

A large-scale study conducted in UK revealed that social media was the most popular type of online news among UK adults in 2018, with Facebook being the most used source at 33% (Jigsaw Research, 2018).

Forty-three percent of the librarians in our study reported that while reading news on social media, its trustworthiness mattered to them and they placed their trust in print (e.g., newspapers) and electronic (e.g., radio, TV, cable) news sources. These findings are in line with the findings of Jigsaw Research (2018) which shows that 77% of adults in the UK indicated that quality, trustworthiness and accuracy of news obtained from a magazine and radio is more valued, as compared to social media and many people showed concern about ‘fake news’ on social media.

In our study, 41% of librarians ‘very often’ or ‘often’ encountered a fake news story on social media. Previously, a large-scale survey (Barthel et al., 2016) reports that 32% of the US adults often encountered completely made up stories on social media. Our study also supports the findings of other studies that fake news on social media is published mainly to support or oppose political agenda (Lazer, et al., 2018; Howard et al., 2018), religious agenda (Boyd and Ellison, 2007; Howard et al., 2017; Farkas et al., 2018), and to trigger people to take certain actions (Kang and Goldman, 2016). Another study from the USA indicates that 71% adults either ‘often’ or ‘sometimes’ see completely made up political news online (Barthel et al., 2016), and many U.S. adults have expressed their concerns about the impact of fake news stories on the 2016 Presidential election in the US (Allcott and Gentzkrow, 2017; Silverman, 2016).

Our study reveals that university librarians use different ways to determine the authenticity of the news. A majority of the respondents ‘often’ check the objectivity and reliability of the sources, check the home page to know more about the source, and check the validity of timings of the news, whereas, they ‘sometimes’ check the credibility of the news source, check it on other sources in case of doubt, search for the news source to see what else they have published, or check the URL to see the reliability of a news story, etc.

Regarding news literacy skills, the findings show that librarians have a slightly moderate level of understanding of the concept of news literacy, as well as they demonstrated a moderate level of perceived news literacy skills (Table 9). They are ‘somewhat’ confused about the trustworthiness of news and information on social media that affect their ability to judge truth of the news story and their skills to interpret news messages. Moreover, librarians are partially aware of their own biases and belief while reading news stories. They are also somewhat sceptical about the role of positive and negative effects of news content on individuals. These findings demonstrate a gap between the perceived news literacy skills of librarians and the skills that are required to have for countering the fake news phenomenon and giving news literacy instruction to students. Stein-Smith (2017) recommends the education of librarians so that they can effectively enable students to achieve digital and news information literacy. Our study also endorses this recommendation.

Various approaches have been proposed in the literature on assessing the validity of information and coping with fake news phenomenon Batchelor, 2017; Steinberg, 2017); these approaches can be used to enhance the news literacy skills of university librarians. There are several facts checking Websites available that are gaining popularity such as FactCheck.org (Batchelor, 2017).

The CRAAP (currency, reliability, authority, accuracy, and purpose) test is a popular check list for assessing the validity of the information source. It proposes a set of questions for assessing the validity of the information source. For example, in relation to currency, it asks questions such as how recent is the information? How recently has the Website been updated? Is it current? In relation to reliability, it asks questions about assessing the objectivity and reliability of the sources. Similarly, each part of this check list contains questions to help to determine the authenticity of the news sources (California State University, Chico, 2010).

Implications of the study

Our study has practical implications as it highlights the news-related behaviour and level of news literacy skills among librarians, therefore, at a practical level, it recommends the need for sensitizing university librarians about their news literacy skills and the role they can play as an instructor. In order to be a news literacy instructor and responsible disseminator of information, they need mastery over these skills. Moreover, it also highlights a need to adopt internationally accepted news literacy frameworks and techniques to educate young students and encounter fake news phenomenon in Pakistan. The instrument we have developed can be of value to study the subjects in other cultures and countries.

Limitations of the study

The study has some limitations such as the data was collected from the librarians working in public and private sector university libraries of the Punjab province. The results of this study may not be generalized to other librarians working in special libraries, college and school libraries.

Another limitation may include the use of a self-administered instrument for assessing the respondents’ perceived news literacy skills, their level of trustworthiness about different news sources, and frequency of determining the authenticity of a news story. In a survey, the questionnaire’s statements are always subject to personal understanding and prejudices. Although, in order to minimize the bias, the questionnaire was pre-tested and validated by three experts in the fields of library and information science, information management and mass communication, and pilot tested. Internal consistency and content reliability of the questionnaire was also maintained using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. Moreover, the respondents were limited to only close ended questions; therefore, conducting a study using a qualitative approach such as focus group discussion or interview may yield more reliable information.

Conclusion

The study concludes that university librarians are not fully acquainted with the aspect of news trustworthiness on social media.. They also have a moderate level of conceptual understanding of news literacy skills. The study recommends that librarians should improve their news literacy skills through self-directed learning and development in order to provide news literacy instruction to the students. The news literacy skills of information professionals are important in order to play their part effectively in combating the fake news phenomenon in society.

Acknowledgements

This study is a part of the Punjab Higher Education Commission’s Indigenous Postdoctoral Fellowship 2018-2019 funded for the research project on 'Combating fake news era: Role of academic libraries in news literacy of students'.

About the authors

Kanwal Ameen is Professor of Information Management, and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Home Economics, Lahore, Pakistan. She has research interests in academic libraries and information behaviour. E-mail: kanwal.ameen@gmail.com

Salman Bin Naeem is currently a post-doctoral research fellow at Punjab Higher Education Commission, and is Assistant Professor at Department of Library & Information Science, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur. E-mail: salman.naeem@iub.edu.pk

References

Note: A link from the title, or from "(Internet Archive)", is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Aktaş, M.S., Kaplan, S., Abacı, H., Kalipsiz, O., Ketenci, U., & Turgut, U.O. (2019). Data imputation methods for missing values in the context of clustering. In Big Data and Knowledge Sharing in Virtual Organizations (pp. 240-274). IGI Global.

- Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of economic perspectives, 31(2), 211-36. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

- American Library Association. (2017). Resolution on access to accurate information. American Library Association. https://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/statementspols/ifresolutions/accurateinformation (Internet Archive)

- Anderson, A., Allan, S., Stuart, A., & Wilkinson, C. (2008). Nanoethics: the role of news media in shaping debate. In R. Luppicini & R. Adell, (Eds.). Handbook of research on technoethics, Vol. 1 (pp. 373-390). (http://dx.doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60566-022-6.ch025)

- AP News (2018, December 5). EU steps up fight against ‘fake news’ ahead of elections. AP News. https://apnews.com/1e826f96f0974176b788e89dfe1fde97. (Internet Archive)

- AP News (2019, March 15). Spain fights cyberattacks, fake news ahead of key elections. AP News. https://apnews.com/8b123a33a95843159abbc22fea5ecc2e. (Internet Archive)

- AP News (2019, May 9). Singapore outlaws fake news, allow govt. to block, remove it. AP News. https://apnews.com/76bb290db7724086b449071145c98d58. (Internet Archive)

- Barthel, M., Mitchell, A., & Holcomb, J. (2016). Many Americans believe fake news is sowing confusion. Pew Research Center. https://www.journalism.org/2016/12/15/many-americans-believe-fake-news-is-sowing-confusion/. (Internet Archive)

- Batchelor, O. (2017). Getting out the truth: the role of libraries in the fight against fake news.Reference services review, 45(2), 143-148. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-03-2017-0006

- Berghel, H. (2017). Lies, damn lies, and fake news.Computer, 50(2), 80-85.http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/MC.2017.56

- Boyd, D. M., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal ofcomputer‐mediated Communication, 13(1), 210-230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x

- California State University, Chico. Meriam Library. (2010). Evaluating information: applying the CRAAP test. California State University, Chico. https://library.csuchico.edu/sites/default/files/craap-test.pdf. (Internet Archive)

- Chan, K., & D’Memilio, F. (2019). Facebook removes fake Italian accounts ahead of EU election.AP News https://apnews.com/89272c4ff0ec41e2bafed718dbc907d3. (Internet Archive)

- Cohen, D. (2000). Yellow journalism: scandal, sensationalism, and gossip in the media. Millbrook Press.

- Connaway, L. S., Julien, H., Seadle, M., & Kasprak, A. (2017). Digital literacy in the era of fake news: key roles for information professionals.Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 54(1), 554-555. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.2017.14505401070

- Cooke, N. A. (2018). Fake news and alternative facts: information literacy in a post-truth era. American Library Association. https://lccn.loc.gov/2019009348. (Internet Archive)

- Dawn. (2018, October 1). Govt launches ‘fake news buster’ account to expose false reports. Dawn. https://www.dawn.com/news/1436167. (Internet Archive).

- Deisel, A. (2017). Concept of ‘fake news’ blatant misuse of media. IOL. https://www.iol.co.za/capetimes/opinion/concept-of-fake-news-blatant-misuse-of-media-8070037. (Internet Archive).

- Farkas, J., Schou, J., & Neumayer, C. (2018). Cloaked Facebook pages: exploring fake Islamist propaganda in social media. New Media & Society, 20(5), 1850-1867.https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817707759

- Figueira, Á., & Oliveira, L. (2017). The current state of fake news: challenges and opportunities. Procedia Computer Science, 121, 817-825.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2017.11.106

- Finley, W., McGowan, B., & Kluever, J. (2017). Fake news: An opportunity for real librarianship. ILA Reporter 35(3), 8–11. https://www.ila.org/publications/ila-reporter/article/64/fake-news-an-opportunity-for-real-librarianship. (Internet Archive )

- Flintham, M., Karner, C., Bachour, K., Creswick, H., Gupta, N., & Moran, S. (2018, April). Falling for fake news: investigating the consumption of news via social media. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, Canada, April 21-28, 2018 (paper 376). Association for Computing Machinery.https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173950

- Floridi, L (2016, November 29). Fake news and a 400-year-old problem: we need to resolve the “Post Truth” crisis. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/nov/29/fake-news-echo-chamber-ethics-infosphere-internet-digital. (Internet Archive)

- Head, A. J., Wihbey, J., Metaxas, P.T., MacMillan, M., & Cohen, D. (2018). How students engage with news: five takeaways for educators, journalists, and librarians.Knight Foundation and Association of College and Research Libraries. https://library.educause.edu/resources/2018/10/how-students-engage-with-news-five-takeaways-for-educators-journalists-and-librarians. (Internet Archive).

- Hernandez, C. (2018). Fake news and academic librarians: a hook for introducing undergraduate students to information literacy. In D.E. Agosto (Ed.). Information Literacy and Libraries in the Age of Fake News, (pp. 167-176). Libraries Unlimited.

- Howard, P. N., Bolsover, G., Kollanyi, B., Bradshaw, S., & Neudert, L. M. (2017). Junk news and bots during the US election. What were Michigan voters sharing over Twitter? Comprop Oxford Limited. (COMPROP Data Memo, 2017.1). http://blogs.oii.ox.ac.uk/politicalbots/wp-content/uploads/sites/89/2017/03/What-Were-Michigan-Voters-Sharing-Over-Twitter-v2.pdf. (Internet Archive).

- Howard, P. N., Kollanyi, B., Bradshaw, S., & Neudert, L. M. (2018). Social media, news and political information during the US election. Was polarizing content concentrated in swing states? arXiv.org https://arxiv.org/abs/1802.03573

- International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. (2016). How to spot fake news? IFLA. https://repository.ifla.org/handle/123456789/167. (Internet Archive)

- Jacobson, L. (2017). The smell test: In the era of fake news, librarians are our best hope.School Library Journal, 63(1), 24–29. https://www.slj.com/?detailStory=the-smell-test-educators-can-counter-fake-news-with-information-literacy-heres-how. (Internet Archive)

- Jigsaw Research. (2018). News consumption in the UK: 2018. Ofcom. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/116529/news-consumption-2018.pdf. (Internet Archive).

- Kang, C., & Goldman, A. (2016, December 5). In Washington pizzeria attack, fake news brought real guns. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/05/business/media/comet-ping-pong-pizza-shooting-fake-news-consequences.html. (Internet Archive)

- Kleemans, M., & Eggink, G. (2016). Understanding news: the impact of media literacy education on teenagers’ news literacy. Journalism Education, 5(1), 74-88. https://journalism-education.org/2020/07/understanding-news-the-impact-of-media-literacy-education-on-teenagers-news-literacy/. (Internet Archive)

- Kumpel, A. S., Karnowski, V., & Keyling, T. (2015). News sharing in social media: a review of current research on news sharing users, content, and networks. Social Media + Society, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115610141.

- Lazer, D.M.J., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., Metzger, M. J., Nyhan, B., Pennycook, G., Rothschild, D., Schudson, M., Sloman, S.A., Sunstein, C.R., Thorson, E.A., Watts, D.J., & Zittrain, J.L. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094-1096.https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2998

- Maksl, A., Ashley, S., & Craft, S. (2015). Measuring news media literacy. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 6(3), 29-45. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1174&context=jmle. (Internet Archive)

- Maksl, A., Craft, S., Ashley, S., & Miller, D. (2017). The usefulness of a news media literacy measure in evaluating a news literacy curriculum. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 72(2), 228-241.https://doi.org/10.1177/1077695816651970

- Malik, M. M., Cortesi, S., & Gasser, U. (2013). The challenges of defining 'news literacy'. Berkman Center Research Publication, No. 2013-20. https://bit.ly/3rK9Iuu. (Internet Archive).

- Maoret, M. (2017, May 10). The social construction of facts: surviving a post-truth world [Video]. YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7tHbSasnvno. (Internet Archive)

- Mitchell, A., & Page, D. (2014). State of the news media 2014: overview. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2014/03/26/state-of-the-news-media-2014-key-indicators-in-media-and-news/. (Internet Archive).

- Neely-Sardon, A., & Tignor, M. (2018). Focus on the facts: a news and information literacy instructional program. The Reference Librarian, 59(3), 108-121 https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2018.1468849

- Ortutay, B. (2018, November 3). Social media’s misinformation battle: no winners, so far. AP News. https://apnews.com/1729336126a448549379beb364180e27. (Internet Archive).

- Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2019). Fighting misinformation on social media using crowdsourced judgments of news source quality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(7), 2521-2526. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1806781116

- Posetti, J., & Matthews, A. (2018). A short guide to the history of ‘fake news’ and disinformation: a learning module for journalists and journalism educators. International Center for Journalists. https://www.icfj.org/sites/default/files/2018-07/A Short Guide to History of Fake News and Disinformation_ICFJ Final.pdf. (Internet Archive)

- Reis, J. C., Correia, A., Murai, F., Veloso, A., Benevenuto, F., & Cambria, E. (2019). Supervised learning for fake news detection. IEEE Intelligent Systems, 34(2), 76-81. https://doi.org/10.1109/MIS.2019.2899143

- Samaa Digital (2018, October 19). Facebook Launches ‘War room’ to tackle fake election news. Samaa Digital. https://www.samaa.tv/technology/2018/10/facebook-launches-war-room-to-tackle-fake-election-news/. (Internet Archive)

- Shao, C., Ciampaglia, G. L., Varol, O., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2017). The spread of fake news by social bots. Arxiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/1707.07592.

- Silverman, C (2017, November 16) Viral fake election news outperformed real news on Facebook in final months of the US election. BuzzFeed News. https://www.benton.org/headlines/viral-fake-election-news-outperformed-real-news-facebook-final-months-us-election. (Internet Archive).

- Silverman, C. (2016, November 16). This analysis shows how viral fake election news stories outperformed real news on Facebook. BuzzFeed News. /https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/viral-fake-election-news-outperformed-real-news-on-facebook. (Internet Archive).

- Sirajudeen, S.M., Azmi, N.F.A., & Abubakar, A.I. (2017). Online fake news detection algorithm. Journal of Theoretical & Applied Information Technology, 95(17), 4114-4122. http://www.jatit.org/volumes/Vol95No17/7Vol95No17.pdf. (Internet Archive)

- Spratt, H.E., & Agosto, D.E. (2017). Fighting fake news: because we all deserve the truth.Young Adult Library Services, 15(4), 17-20. http://yalsjournal.ala.org/publication/?m=53337&i=460559&p=19&pp=1&ver=html5. (Internet Archive)

- Stein-Smith, K. (2017). Librarians, information literacy, and fake news. Strategic Library, (No. 37), 1-23. http://www.libraryspot.net/SL/SL_Mar17_1.pdf. (Internet Archive).

- Steinberg, L. (2017). Beyond ‘fake news’ - 10 types of misleading news. European Association for Viewers Interests. https://eavi.eu/beyond-fake-news-10-types-misleading-info/. (Internet Archive).

- Sullivan, M.C. (2019). Libraries and fake news: what’s the problem? What’s the plan? Communications in Information Literacy, 13(1), 7.https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2019.13.1.7

- Tandor, E.C., Lim, Z.W., & Ling, R. (2018). Defining “fake news” A typology of scholarly definitions. Digital Journalism, 6(2), 137-153. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1360143

- UNESCO. (2019a). Information literacy. UNESCO. http://www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/access-to-knowledge/information-literacy/. (Internet Archive)

- UNESCO. (2019b). Media and information literacy: critical-thinking, creativity, literacy, intercultural, citizenship, knowledge and sustainability (MIL CLICKS). UNESCO. https://en.unesco.org/MILCLICKS. (Internet Archive).

- Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146-1151. https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.aap9559

- Wardle, C. (2017, February 16). Fake news. It’s complicated. First Draft. https://firstdraftnews.org/latest/fake-news-complicated/ - (Internet Archive)

- Wardle, C. (2016, November 30). The First Draft timeline of the fake news debate surrounding the 2016 US presidential election. First Draft. https://firstdraftnews.org/latest/key-moments-fake-news-debate/. (Internet Archive)

- Wardle, C., & Derakhshan, H. (2017). Information disorder: toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making. Council of Europe. (Internet Archive)

- Wade, S., & Hornick, J. (2018). Stop! Don’t share that story! Designing a pop-up undergraduate workshop on fake news. Reference Librarian, 59(4), 188-194.https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2018.1498430

- Wineburg, S., McGrew, S., Breakstone, J., & Ortega, T. (2016). Evaluating information: the cornerstone of civic online reasoning. Stanford University. Stanford History Education Group. https://purl.stanford.edu/fv751yt5934. (Internet Archive)

How to cite this paper

Appendix

Questionnaire. Post truth era: News behaviour and news literacy skills of university librarians.

Q-1 How often do you use the following social media channels to share news?

| Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Google+ | |||||

| Snapchat | |||||

Q-2 What is your level of trustworthiness about the following news sources?

| Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Almost Always | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Print (e.g., newspapers) | |||||

| Electronic (e.g., radio, TV, cable) | |||||

| Social media feeds (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) | |||||

| Blogs (BuzzFeed) | |||||

| Friends/Peers etc |

Q-3 How often do you encounter a fake news story on social media?

Q-4 While reading a news on social media, does its trustworthiness matters to you?

Q-5 In your opinion why fake news are published on social media?

| Definitely Not | Probably Not | Probably Yes | Definitely Yes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| To confuse people | ||||

| To deceive people | ||||

| To advance a vested interest or agenda | ||||

| To support or oppose a cause, political, or religious, etc. | ||||

| To trigger people to take some action | ||||

| Just by ignorance | ||||

| Just for fun (or as a prank) | ||||

| Any other (please specify) |

Q-6 Using the following scale of 1-5, please rate your news literacy skills?

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Somewhat agree | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Statements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I have a good understanding of the concept of news literacy | |||||

| I have the skills to interpret news messages | |||||

| I understand how news is made | |||||

| I am confident in my ability to judge a truthiness of the news item | |||||

| I’m often confused about the trustworthiness of news and information on social media | |||||

| I can compare news across different media sources to determine its trustworthiness | |||||

| I know how to use searching techniques to get the needed information from the media | |||||

| I am aware of my own bias and beliefs while reading news stories | |||||

| I am good at catching-up with the changes in the agenda of media | |||||

| I am aware of the fact that malpractices may influence news content | |||||

| I am sensitive about the role of positive and negative effects of news contents on individuals. |

Q-7 While reading a news story, which of the following do you do to determine its authenticity?

| Statements | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I check that the credibility of the news source | |||||

| I check the validity of timings of the news | |||||

| I search for the news source to see what else they’ve published | |||||

| I check what others are saying about the news story | |||||

| I check the objectivity and reliability of the source | |||||

| I check the homepage to know more about the source | |||||

| I check it on other sources in case of doubts | |||||

| I make sure that the news is not given in a sarcastic manner | |||||

| I check the URL to see the reliability of a news story | |||||

| I try to ask from media person, if possible | |||||

| I share with other (e.g., colleague, peer, fried) to seek his/her opinion |