Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science, Oslo Metropolitan University, May 29 - June 1, 2022

Collaboration between academics and librarians in information literacy instruction at Aalto University following a decentralising restructure

Tayo Nagasawa

Introduction. This study explored collaboration between academics and librarians in information literacy settings from the perspectives of information sharing and social networks based on a case study of Aalto University in Finland.

Method.A qualitative case study approach was adopted. Aalto University was selected as a salient case because its library organisation was decentrally restructured and embedded in institutional service sections in 2018.

Analysis. The data, mainly from interviews, were collected and analysed via thematic analysis.

Results. This study finds that academics and librarians collaborate indirectly. Mediated by study coordinators, key information and/or timetables are shared within online networks. Although the restructure of the library formed new ties outside the library, information on information literacy instruction is rarely shared. The library personnel reduction requires librarians to restrict their effort devoted to instructional services including information sharing.

Conclusions. This study finds that organisational social networks with almost no cohesive ties between academics and librarians maintain collaboration for information literacy instruction based on occasional information sharing. Although the restructure of the library expanded its organisational horizons, the limited time and therefore effort available of librarians constrains substantial active information sharing for information literacy instruction.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/colis2215

Introduction

In the library and information science literature, collaboration between academics and librarians in higher education has been studied in information literacy settings in many cases. The preceding studies discuss the collaboration within several thematic aspects: strategic approaches in educational development (e.g., Machin et al., 2009); understanding/supporting academics (e.g., Amante et al., 2012); redesigning library structure/personnel (e.g., Huotari and Iivonen, 2005); and influential conditions in libraries/institutions/societies (e.g., Julien and Given, 2003). Few studies, however, reveal the collaboration from a perspective in which information sharing and social networks are combined. This study aims to explore collaboration between academics and librarians in information literacy settings from the perspectives of information sharing and social networks, based on a case study of Aalto University in Finland.

Aalto University was selected as a salient case because the library was recently, decentrally restructured and embedded in institutional service sections. Since the restructure formed new ties outside the library, investigating information sharing and social networks between academics and librarians in information literacy settings offers the potential for extracting unique findings.

Literature review

Information sharing is approached as ‘a set of activities by which information is provided to others, either proactively or upon request’ and has two major perspectives to study: a one- way communication process and a two-way communication process (Savolainen, 2019; Sonnenwald, 2006). In this study, information is shared for work in information literacy settings, in which librarians support students to improve their information literacy, e.g. training in information retrieval skills. Information must be shared to build and maintain collaboration. Talja (2002) presents concepts and hypotheses of information sharing including super sharing, occasional sharing and nonsharing in relation to document retrieval in academic communities (p. 4). Pilerot (2012) identifies studies on information sharing which apply a social network framework e.g. HIV/AIDS information networks (Veinot, 2009). Social network frameworks are denoted by:

“actors” maintain “relations” with others which form the “tie” between them. The collective set of actors and ties forms “network” of connections among all members of the particular social set (Haythornthwaite, 2017, p. 4236).

Since ‘social network structures play a role in how easily information circulates’ (Haythornthwaite, 2017, p.4235), investigating how ties, i.e. social networks, between academics and librarians are configured contributes to understanding collaboration between academics and librarians. Nonetheless, few studies of the collaboration in information literacy settings have applied this framework.

Some studies of collaboration between academics and librarians in information literacy settings indicate information sharing from the aforementioned thematic aspect of strategic approaches to educational development. Wang (2011) identifies ‘shared understanding’ of information literacy in curricula and ‘shared knowledge’ of respective expertise as two of four key modes of behaviour of campus-wide collaboration including between academics and librarians. Machin et al. (2009) implement the model: ‘[t]hrough ongoing facilitation, the collaborative team work towards shared agreement and understanding of key values, tasks, operational language, and parameters of the development’ (p. 149). Other studies point out information sharing from the aforementioned thematic aspect of influential conditions. Ivey (2003) identifies a shared understanding of information literacy and the associated teaching responsibilities is one of four conditions essential for successful partnership between academics and librarians. Pham and Williamson (2018) address the proposition that despite few intersections in the institutional structure, organisational supportive structures at senior management level can enable information sharing between academics and librarians ‘that could lead to more specific collaborative ventures’.

Whereas these studies raise issues concerning the importance of shared understandings of information literacy, shared knowledge of respective expertise and organisational supportive structures for information sharing, few studies explicitly address the question of social networks. Hence, this study seeks to answer the following research questions within information literacy settings in higher education:

What kinds of social networks between academics and librarians exist?

What kinds of information do academics and librarians share within those networks?

How did the restructure of the library influence social networks and information sharing within those networks?

Method

To address these research questions, this study employs a qualitative case study approach. Since its aim is to offer a means of investigating complex social units consisting of multiple variables in understanding a phenomenon (Merriam, 1998), this approach is suited to untangle social networks and information sharing activities. Aalto University was selected as a salient case because its library was decentrally restructured and embedded in institutional service sections in 2018.

Aalto University was established based on a merger of three universities in 2010 and these universities were relocated to one campus between 2016 and 2018. The unified library was renamed the Learning Centre in 2016 (Rämö, 2018) and was divided into eight teams which were embedded in four institutional service sections in 2018. The librarians and library staff were allocated across these teams. Then, information literacy instructional services were divided into two sections. Its work with the first-year students went to the new learning services section, and for bachelor, master and doctoral theses to the new research and innovation services section. Due to having no further meetings across these sections, librarians now operate information literacy instructional services in their respective sections. This study covers the period between the restructure of the library in 2018 and the start of measures to control the COVID-19 situation in 2020.

The data were collected between June and December 2021 through semi-structured interviews using Zoom with librarians and academics at Aalto University. In addition, further data from published materials and internal documents were collected. Prior to this data collection, a pre interview for background information about Aalto University was conducted. As main target informants, librarians and academics who have been involved in information literacy instruction were selected based on the pre interview. Accordingly, three librarians responsible for contact with their respective schools, a librarian for new student orientation and a librarian in a managerial position, making a total of five, participated. Three librarians were interviewed twice to collect further background and detailed information. Four academics were asked to participate, two were interviewed and one was analysed. Hence, eight interviews from six informants (A1, L1-5) were analysed. Thus, the collected data were mainly from librarians which somewhat affects the findings. The average length of these interviews was seventy-five minutes. All interviews were recorded using Zoom and/or an IC recorder, and transcribed. The interview transcripts were analysed utilising thematic analysis, which is ‘a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data ’ and has the potential to interpret various aspects of the research topic (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Since this study aims to explore patterns and pertinent themes of collaboration, thematic analysis is considered to be an appropriate method. The data were not coded into predefined categories, and categories were extracted inductively.

The following section consists of two parts. The first part describes the existing social networks and information sharing between academics and librarians in information literacy settings. The second part explains how the restructure of the library influenced the social networks and information sharing.

Results

Indirect collaboration between academics and librarians

In information literacy settings, academic and librarian collaboration is mostly mediated by study coordinators in the schools. Although a few variations dependent on schools are identified, key information and/or timetables are shared within online networks.

Mediated study coordinators and online request forms.

The first situation is a school in which information literacy instruction for bachelor and master theses is not mandatory.

Firstly, a librarian as the contact person for information literacy instruction in the school, sends e-mails to the study coordinators in the various departments of the school. The e-mail contains an advertisement for information literacy instruction and a link to an online request form to book a session provided by a librarian. On receiving the e-mail, study coordinators forward it to academics who engage in bachelor or master thesis seminars in each department. Academics who desire information literacy sessions, fill out the online request form supplying key information: major subject and topics of theses; previous experience in using electronic resources and databases; information needs, expectations and questions; and most suitable dates and times, and then submit the form.

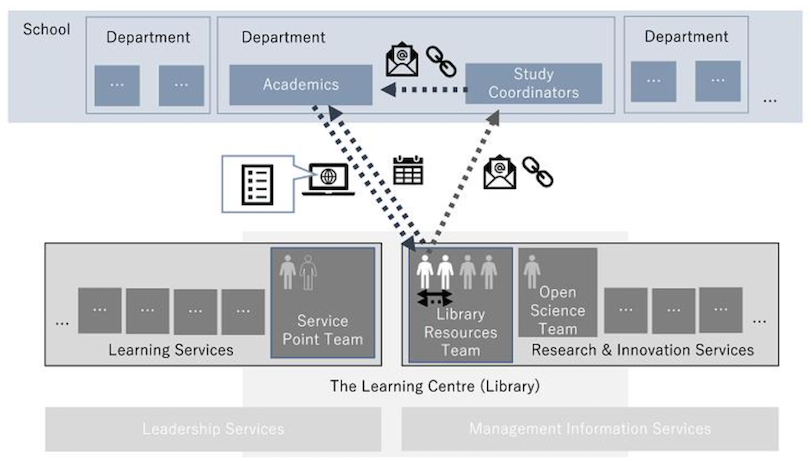

After receiving the forms, the named librarian sets the dates and times for information literacy sessions based on confirming schedules with the other librarian responsible for the school, and sends an e-mail to each academic with the schedule. Although this e-mail usually contains a question asking academics ‘do you want something new?’ or ‘should we do it in the same way as last year?’, academics usually make no further request. Based on the key information from the online request form, the librarian usually sets up databases, queries and journals tailored to each seminar without further information from academics (Figure 1). For example, when the relevance of a particular database can be presumed from the request form, then the librarian simply includes that database in the session (L1). Figure1 depicts interpersonal ties as solid arrows, online ties as dotted arrows and line thickness shows the volume of ties.

Mediated study coordinators in school and departments

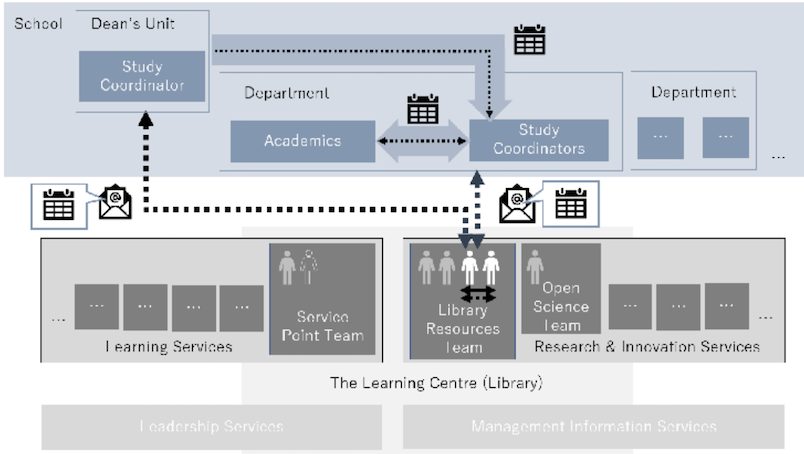

The second situation is a school in which information literacy instruction for bachelor and master theses is mandatory as a part of curricula. Firstly, the study coordinator who coordinates mandatory courses for bachelor students in the dean’s unit of the school, sends an e-mail to ask a particular librarian, who is the contact person for information literacy instruction in the school, if librarians need to update the existing information literacy course descriptions for the next period e.g. 2020-2022. If needed, the librarian updates the course descriptions, e.g. adding how to find open access information, and then returns them to the dean’s study coordinator. The study coordinator informs each departmental study coordinator of all course descriptions including information literacy sessions. After confirming the course description, each departmental study coordinator sends an e-mail to ask the librarian if a tentative schedule of information literacy sessions suits the librarian. After confirming the schedules with the other librarian responsible for the school, the librarian replies to the departmental study coordinator regarding their availability. Typically, no information is shared directly between academics and librarians (Figure 2). As for information literacy instruction for master theses and doctoral theses, these processes are similar to that for the bachelor theses (L2).

The third situation is a school in which mandatory information literacy instruction only applies to bachelor theses. The process here is similar to the second situation, above. Firstly, departmental study coordinators, or sometimes lecturers with assistant roles, who are responsible for the bachelor seminars in the various departments contact the named librarian to suggest the dates and times for information literacy sessions. After the librarian replies with available dates and times to each contact person, no further information is shared (L3).

Before and after the restructure of the library, the configurations of these social networks and information sharing activities show no differences. Since academics and librarians share information within online networks mediated by study coordinators, the collaboration can be characterised as indirect collaboration. Even if existing study coordinators move, these processes remain because their replacements simply operate as before (L1). Although academics and librarians sporadically share information directly, including on subjects and topics while preparing (A1, L2) or during information literacy sessions (L1, L3), these instances are very limited.

Existent information sharing remained within expanded social networks

The restructure of the library formed no cohesive ties between academics and librarians but new ties were formed between librarians and institutional service sections including units within schools. Within the new ties, information on information literacy instruction is rarely shared, however. The library personnel reduction requires librarians to restrict their efforts dedicated to a particular chunk of information literacy instruction and that restriction includes effort devoted to information sharing beyond the minimum necessary to ensure timely delivery.

Expanded social networks

After the restructure, librarians responsible for information literacy instruction for bachelor, master and doctoral theses began to receive information about more than library matters in monthly meetings of the institutional research and innovation services section. Although other team members share a variety of information including on research funding and academic legal services, information on information literacy instruction is rarely shared. Although the librarian team manager has opportunities to share current information and periodical statistics from library services, other team members seldom offer comments on information literacy instruction (L2).

As for the team now part of the institutional learning services section, the librarian team manager, a librarian responsible for new student orientation and other librarians began to receive information respectively from other teams in their new section. The librarian team manager receives a variety of information in the fortnightly board meetings for the institutional learning services section, and shares selected relevant information with the other team members (L5). The librarian responsible for new student orientation realises that the meetings to discuss and agree new student orientation provide ‘a good place to get information that I may not be able to get otherwise’ (L4). The institutional learning services section contains several learning service units based in and dedicated to schools e.g. the School of Business Learning Services. Since two librarians in the team work as a member of the respective school learning service units one day per week, these librarians have opportunities to receive current information in those schools. Although librarians formed new ties with other teams and/or schools following the restructure, little external information is systematically shared inside the librarian team (L5).

Reduced library personnel

One of the reasons information useful for information literacy instruction is not being shared actively within the new ties is reduction in the number of library personnel. The restructure of the library progressively reduced the total from ninety-five in 2010; to sixty-seven in 2016; and sixty-one in 2018. Personnel were relocated to other sections and retirees/leavers were not replaced. Accordingly, the number of librarians available to deliver information literacy instruction, has fallen.

The restructure also divided instructional service personnel into two teams: the team under the institutional research and innovation services for information literacy instruction for bachelor, master and doctoral theses; and the team under the institutional learning services section for new student orientation. The number of librarians responsible for the former has declined from thirteen to five, and an additional librarian is engaged in the latter. Most of the other librarians who used to engage in information literacy instruction were relocated into other teams and subsequently had no further responsibility for instructional services. Accordingly, the number of information literacy sessions delivered per librarian proliferated. One librarian had to deliver many more sessions solo after a partner librarian retired (L3). Another librarian reports that two librarians handle more sessions than five librarians used to deliver before the restructure (L2). Furthermore, additional responsibilities were allocated to librarians including the six librarians responsible for instructional services. Although additional responsibilities sometimes bring information on academics and schools, these librarians are expected to restrict effort devoted to delivering information literacy instruction. Some librarians were obliged to shorten the length of information literacy sessions (L2). Another librarian said that ‘we don’t really advertise these sessions as actively as we did before when we had six people [responsible for the school] doing this work’ (L1). Under these conditions, librarians struggle to maintain the social networks and information sharing activities for information literacy instruction already in existence.

Discussion

Based on a case study of Aalto University, this study finds that academics and librarians collaborate indirectly. As mediated by study coordinators, key information and/or timetables are shared within online networks. Although the restructure of the library formed new ties outside the library, information on information literacy instruction is rarely shared. The library personnel reduction requires librarians to restrict their effort devoted to instructional services including information sharing.

The social networks between academics and librarians are mediated by study coordinators. Since study coordinators have current information on who is engaged in teaching relevant seminars in the department, librarians only have to send one e-mail to study coordinators without confirming for themselves who is engaged in the seminars. This mediation by study coordinators, involving almost no cohesive ties between academics and librarians, helps to circulate information from librarians to all the academics whom librarians should contact. This means that the social networks consist of organisation created, not ad hoc or personal ties. As stated above, Pham and Williamson (2018) show how organisational supportive structures at senior management level involving both academic managers and library managers can lead to information sharing between academics and librarians in specific operations. At Aalto University the organisational supportive structures specific to information literacy instruction maintain information sharing, i.e. collaboration, between academics and librarians.

As for information sharing within the social networks, librarians share little expertise with academics, but some academics share key information on subject fields with librarians. After receiving the key information, librarians give and/or receive no further information to and/or from academics to prepare information literacy instruction. Ivey (2003) and Wang (2011) show that shared understanding of information literacy and shared knowledge of respective expertise are key types of behaviour for successful collaboration in developing information literacy programmes. Probably because this study focuses on existent information sharing activities, both academics’ and librarians’ expertise in particular is seldom shared. One of the concepts of information sharing presented by Talja (2002) is ‘occasional sharing’. The features of occasional sharing are: to it takes place between actors who seldom share the same interest and subject; it has limited forms to of sharing information; and it shares information less often (p.4). Assessed via information shared, forms and frequency, the information sharing identified in this study can be categorised as occasional sharing.

The restructure formed new ties outside the library. Although no ties with academics were formed, librarians began to gain an increased amount and variety of information from other institutional learning and research teams including those in schools. This means that the extant library services social networks, including those for information literacy instruction, i.e. the aforementioned organisational supportive structures were expanded on paper to institution-wide social networks. Due to the library personnel reduction, few of the new ties have enhanced information sharing powerfully enough to improve information literacy instruction as yet. These social networks, however, have an important potential for information sharing to facilitate and improve information literacy instruction.

This study contributes to making social networks visible as well as information sharing between academics and librarians in information literacy settings. However, some limitations remain. Firstly, the social networks found in this study were extant prior to the restructure. More active and expanded social networks and information sharing activities might have been identified in new networking processes. Secondly, this study focuses on institutional routines and excludes sporadic, ad hoc, individual information sharing activities in its analysis. Thirdly, a wider range of informants should need to be interviewed to enhance the picture: academics in particular, librarians including those in managerial positions and study coordinators.

Conclusions

This study finds that organisational social networks, with almost no cohesive ties between academics and librarians and depending on occasional information sharing, maintain the collaboration needed for information literacy instruction. Although the restructure of the library expanded its organisational horizons, the limited effort that has been able to be made by librarians has constrained substantialising active information sharing for information literacy instruction.

At Aalto University a reorganisation specific to information literacy instructional services has been planned. The new organisation starts in January 2022 and information literacy instruction programmes, as redesigned, will be delivered in the autumn of 2022. Investigating new social networks and information sharing activities for information literacy instruction is therefore a topic of future study.

Acknowledgements

This paper owes much to the valuable information provided by informants at Aalto University in Finland. I am grateful for the time informants gave to take part in my study. I also wish to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on my paper. Finally, I would like to acknowledge my supervisors: Dr. Gunilla Widén, professor at Åbo Akademi University in Finland and Dr. Jannica Heinström, professor at Oslo Metropolitan University in Norway. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 19K12713.

About the author

Tayo Nagasawais a Ph.D. student in information studies at Åbo Akademi University in Finland and an associate professor in the Organization for Information Education and Research at Mie University in Japan. Her research interests are collaboration, information sharing, social networks, higher education and information literacy. Her mailing address is Mie University Library, 1577 Kurima-machiya, Tsu, Mie 514-8507 JAPAN. She can be contacted at tnagasaw@abo.fi.

References

- Amante, M.J., Extremeno, A.I. & da Costa, A.F. (2012). Modelling variables that contribute to faculty willingness to collaborate with librarians: the case of the University Institute of Lisbon (ISCTE-IUL), Portugal. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 45 (2), 91-102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000612457105

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3 (2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Haythornthwaite, C. (2017). Social networks and information transfer. In J.D. McDonald, & Michael Levine-Clark (Eds.), Encyclopedia of library and information sciences (4th. ed., pp. 4235-4245). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1081/E-ELIS4

- Huotari, M.L. & Iivonen, M. (2005). Knowledge process: a strategic foundation for the partnership between the university and its library. Library Management, 26 (6/7), 324- 335. https://doi.org/10.1108/01435120410609743

- Ivey, R. (2003). Information literacy: how do librarians and academic work in partnership to deliver effective learning programs?. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 34 (2) 100-113. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2003.10755225

- Julien, H. & Given, L. (2003). Faculty-librarian relationships in the information literacy context. Canadian Journal of Information and Library Science, 27 (3), 65-87. https://doi.org/10.29173/cais526

- Machin, A. I., Harding, A. & Derbyshire, J. (2009). Enhancing the student experience through effective collaboration. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 15, 145-159. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614530903240437

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applicants in education. Jossey-Bass.

- Pham, H.T. & Williamson, K. (2018). A two-way street: collaboration and information sharing in academia. A theoretically-based, comparative Australian/Vietnamese study. Information Research, 23 (4), paper isic1810. http://informationr.net/ir/23-4/isic2018/isic1810.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20220516121018/http://informationr.net/ir/23-4/isic2018/isic1810.html)

- Pilerot, O. (2012). LIS research on information sharing activities: people, places, or information. Journal of Documentation, 68 (4), 559-581. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220411211239110

- Rämö, E. (2018). Service design and co-design work at Aalto University Learning Centre. In J. Atkinson (Ed.), Collaboration and the academic library: internal and external, local and regional, national and international (pp.131-141). Chandos Publishing.

- Savolainen, R. (2019). Modeling the interplay of information seeking and information sharing: a conceptual analysis. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 71(4), 518- 534. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-10-2018-0266

- Sonnenwald, D.H. (2006). Challenges in sharing information effectively: examples from command and control. Information Research, 11 (4), paper 270. http://informationr.net/ir/11-4/paper270.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20220516121617/http://informationr.net/ir/11-4/paper270.html)

- Talja, S. (2002). Information sharing in academic communities: types and levels of collaboration in information seeking and use. New Review of Information Behavior Research, 3 (1) (Archived by CiteSeerX at https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.96.163)

- Veinot, T.C. (2009). Interactive acquisition and sharing: understanding the dynamics of HIV/AIDS information networks. Journal of American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60 (11), 2313-2332. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21151

- Wang, L. (2011). An information literacy integration model and its application in higher education. Reference Services Review, 39 (4), 703-720. https://doi.org/10.1108100907321111186703