Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science, Oslo Metropolitan University, May 29 - June 1, 2022

Public libraries in a changing political landscape: results from a survey on political influence and pressure on public libraries in Southern Sweden

Fredrik Hanell, Joacim Hansson and Hanna Carlsson

Introduction. When the definition of democracy and the meaning of a democratic society is renegotiated and reinterpreted, the mission of the public library is placed in a new context. This paper reports findings from an ongoing research project focused on library managers’ and librarians’ lived experiences of recent political developments in Sweden.

Method/Analysis. Methodologically, the research project applies the perspective of institutional ethnography and combines a longitudinal survey study with interviews, focus- group interviews, and document studies. This paper reports findings from the first stage of a library manager survey.

Results. Results indicate that the interplay between libraries and the local political level is experienced as mostly well-functioning, although notable exceptions exist, and that the correspondence between national cultural- and library policies and politics of the participating municipalities is perceived as high. However, the Library Act paragraph, stipulating that particular attention should be devoted to national minorities and persons with a native language other than Swedish, causes notable opposition between local and national political levels.

Conclusions. Illegitimate political pressure is uncommon, but when it occurs, it is often connected to issues pursued by radical right-wing parties. The study indicates a need to further investigate the intersection of (national) policies and (local) politics.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/colis2216

Introduction

Public libraries in Sweden were institutionalised as part of the establishment of democracy and given a pivotal position in the construction of the social-democratic welfare state during the course of the twentieth century (Hansson, 2010; Torstensson, 2012). Still today, public libraries stand strong, and are seen as important for upholding the Swedish form of governance. Since 2014, the Swedish Library Act (SFS 2013:801) states that ‘libraries in the public library system shall promote the development of a democratic society by contributing to the transfer of knowledge and the free formation of opinions’ and that ‘library activities shall be available to everyone’ (translations from Swedish Library Association, 2015). Formulations such as these are tied closely to the wordings of the constitution, emphasizing the central position of the library system in Swedish society.

However, when the definition of democracy and the meaning of a democratic society is re- negotiated and re-interpreted, the mission of the public library is placed in a new context. The type of democracy expressed in the Library Act is a representative, liberal democracy (Rivano Eckerdal, 2017 ). Support for this type of democracy, combining individual rights and the will of the majority, has decreased in recent years (Mounk, 2018). Political actors, mainly from the radical right, instead advocate a form of democracy focused on the will of the people, at the expense of individual rights. This political project, that also includes a critical view on migration and cultural diversity, stands in stark contrast to the mission of the public library, which implies providing library services to everyone (Carlsson and Rivano Eckerdal, 2018 ).

Swedish politics have traditionally focused on the dimension of socioeconomic cleavage but recently, sociocultural discourses and conflicts concerning immigration and law and order have gained prominence. This is entirely in line with the key rallying issues of ethnic nationalism and anti-establishment populism opposition (Rydgren and Van der Meiden, 2019). Up until the 2010’s, Swedish cultural policies were characterised by cross-partisan consensus on most issues (Lindsköld, 2015 ). Through the gradually increasing presence and influence of radical right-wing party The Sweden Democrats (SD), particularly on the local municipal level in Southern Sweden, public libraries and other institutions promoting culture and participatory democracy have become the focal point of ideological discussions in a new way.

The cultural policies of Scandinavian radical right parties emphasise two main problem representations: multiculturalism is perceived as a threat to national culture and public funding is seen as a threat to freedom (Lindsköld, 2015 ). Both notions stand in opposition to current Swedish cultural policy and the Library Act. Public libraries are affected in a very direct sense by these discussions. Amongst other issues, debate focuses on who the libraries are for and what languages should be prioritised. In 2016, SD petitioned in the Swedish Parliament that the Library Act should only apply for Swedish citizens, offering only citizens access to library service and that only the Swedish language should be prioritised. In Sölvesborg, a municipality in the far South-East of Sweden, the cultural- and library manager was in 2019 relieved of her duties by the local government after a heated discussion concerning the local library plan. Leading SD-politicians wanted to change writings about literature in other languages than Swedish. This became a contested issue as local library plans are defined as compulsory in the Swedish Library Act and should be consistent with the writings of the national law.

These developments motivate further study of how experiences and working conditions at public libraries are affected by current changes in the political landscape. Against the background of these examples of re-interpretations and re-negotiations of the meaning of a democratic society, this current research project is guided by the following main research question:

How are working conditions of librarians and their experiences of the mission to work for the development of a democratic society affected when the established view on democracy is challenged?

This paper seeks to answer this overarching question with an overview of the current situation for public libraries by focusing on local politics in relation to national policies, and concrete formulations in the Swedish Library Act.

In the next section, we briefly present previous research relevant to the research project. Then we describe the research design and present preliminary findings from the first stage of the longitudinal survey study, which includes library managers of public libraries in 77 municipalities from the six southernmost regions of Sweden. The paper ends with some concluding remarks and directions for further studies.

Previous research and project research design

The relation between public libraries and democracy has been continuously studied within library and information science, although research on how policies and politics affect public libraries is scarce (Jaeger, et al., 2013 ). Previous research has investigated the importance of the library as a public arena (e.g., Aabø et al., 2010; Buschman and Leckie, 2007), issues of cultural diversity and participation (Olsson Dahlquist, 2019; Pilerot and Lindberg, 2018), and the relation between national governance and self-governance of municipalities (Rivano Eckerdal and Carlsson, 2018). Public library research often presupposes liberal democratic values to imbue the work of public libraries, but it is important to stress that they function in several political environments. As liberal values based in the Enlightenment are being challenged, it is important to realise that the role of public libraries may differ somewhat in various democratic settings. Such differences have been addressed in Buckland and Takayama (2021, pp. 13-21 and pp. 147-149) and in the research anthology Libraries, archives and museums as democratic spaces in a digital age (Audunson, et al., 2020) gathering studies on public libraries from across Europe.

This project uses institutional ethnography as a theoretical and methodological starting point for studying lived experiences of librarians and library managers in relation to the changing political landscape surrounding public libraries. Institutional ethnography takes as its point of departure a critical, sociological tradition where sayings and doings are to be interpreted as institutional, that is as translocal co-ordinated processes and ways of acting, rather than as only expressions of individual experiences (Smith, 2006). Through this perspective, experiences of individual librarians and library managers also become experiences of the library. This project focuses on the lived experiences of librarians and library managers within the political development in relation to the professional role and their views of the role of the library in the municipality.

This current project comprises several data-gathering efforts, including individual interviews, focus-group interviews, and a recurring survey distributed three times over the project period 2021-2023. The longitudinal survey targets library managers from every municipality (n=77) in the six southernmost regions of Sweden: Skåne, Halland, Blekinge, Kronoberg, Jönköping and Kalmar. The questionnaire focuses three major themes:

- interplay between library and the political level,

- political discussions, and

- political pressure.

The study design encompasses three stages of the survey over three years, with a general election in September 2022, which allows for changes over time to be captured. The number of municipalities enables quantitative comparisons and offers a spectrum of political conditions. Results from the survey are used to guide the following stages of the project, both in terms of selection of municipalities to study further, and in general direction of priorities.

The first stage of the longitudinal survey, reported here, was conducted during May and June 2021. A link to the digital questionnaire was sent by e-mail to the person deemed to be directly responsible for the public library. Seventy-seven per cent of the respondents stated the title ‘library manager’. The others stated similar titles, often some higher position including cultural activities and library services. Among the respondents, 79% had had the same position for at least 3 years. From the total number of respondents, 57 respondents (74%) completed the questionnaire.

All the collected surveys were read through and answers indicating some sort of conflict between the local and the national political levels, and between library and the local political level, as well as answers suggesting conflict between certain passages from the Library Act and political discussions in the municipality were selected for closer reading. Surveys indicating various forms of illegitimate political pressure were also selected. In all, 23 surveys included answers that warranted further interest, and among these, 11 surveys were selected for closer analysis. In the following segments of this paper, results from this first library manager survey are shown. The source material is anonymised and quotes from individual surveys refer to these by survey identifiers 1-57.

Results and analysis

This section is structured in accordance with the major themes of the conducted survey: interplay between library and the political level (question 4), political discussions (question 5- 8), and political pressure (question 9).

Interplay between library and the political level

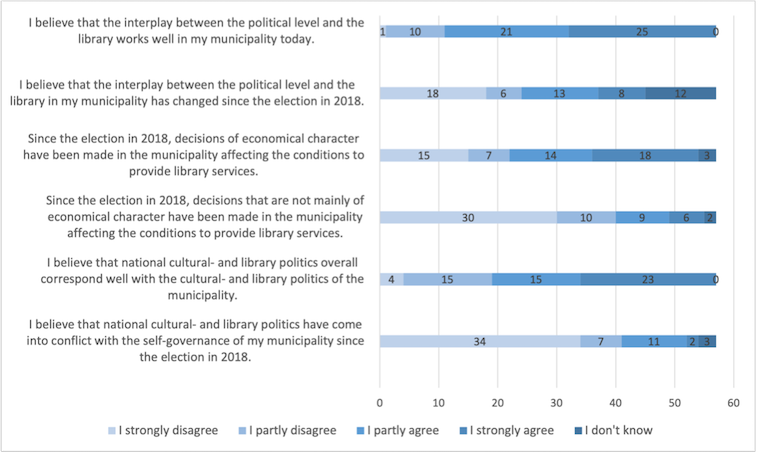

Figure 1 shows that the interplay between libraries and the political level is experienced as well-functioning by the library managers in general. Forty-four per cent of the respondents strongly agree and 37% partly agree with the statement ‘I believe that the interplay between the political level and the library works well in my municipality today’.

Figure 1. Interplay between libraries and the political level. Number of answers per question (n=57).

There are no clear tendencies when it comes to changes in this relation since the election in 2018. For the statement ‘I believe that the interplay between the political level and the library in my municipality has changed since the election in 2018’, 12 of the respondents answer that they do not know (this is the same number as the respondents who have answered that they have had their current position for 0-2 years). Among those who have graded their answer, most have chosen to strongly disagree. The percentage of those who perceive some sort of change (those who strongly agree and partly agree totals 37%) lies near the percentage of those who do not perceive a change (strongly disagree and partly disagree totals 42%).

However, most respondents state that decisions of an economical character have been made in the municipality affecting the conditions to provide library services since the election in 2018 (32% strongly agree and 25% partly agree). Decisions that are not mainly of economical character affecting the conditions to provide library services are not as common: for the statement ‘Since the election in 2018, decisions that are not mainly of economical character have been made in the municipality affecting the conditions to provide library services’, 11% strongly agree and 16% partly agree.

Overall, the perceived correspondence is high between the national cultural- and library politics and the cultural- and library politics of the municipality. Forty per cent of the respondents strongly agrees with the statement ‘I believe that national cultural- and library politics overall correspond well with the cultural- and library politics of the municipality’, and 26% partly agrees. This means that most of the respondents have not experienced that the national cultural- and library politics has come into conflict with the self-governance of their municipality since the election in 2018. However, notable exceptions exist. A noteworthy portion (26%) responded that they partly disagree, and 7% strongly disagrees.

Regarding the last statement in this section of the survey, ‘I believe that national cultural- and library politics have come into conflict with the self-governance of my municipality since the election in 2018’, the majority (60%) strongly disagrees. However, 19% partly agrees and 4% strongly agrees.

Among the comments made by respondents in this section, most concern economic aspects. However, one respondent notably questions the existence of national policies for libraries:

The problem is not primarily the municipality, but that there is no strong national support or supervisory authority that strengthens the libraries (14).

Political discussions and the Swedish Library Act

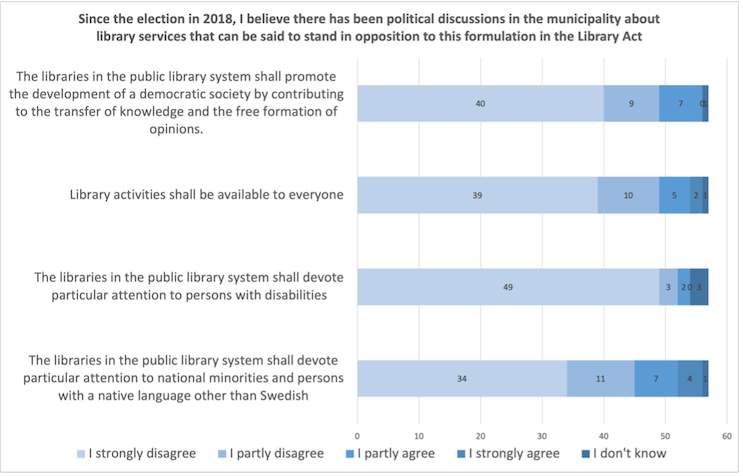

As seen in Figure 2, questions 5-8 can be considered as concrete examples of how the national policy level, as manifested in the Swedish Library Act (SFS 2013:801), may come into conflict with the local political level of the municipality. In this way, the intersection of national policies and local politics is captured. Questions present certain formulations from the Library Act (translations from Swedish Library Association, 2015 ) specifically relevant for public libraries, asking respondents to grade whether they disagree or agree to this statement: ‘Since the election in 2018, I believe there has been political discussions in the municipality about library services that can be said to stand in opposition to this formulation in the Library Act’. Answers from the library managers illustrate that some formulations are more contested than others.

On asking whether political discussions in the municipality have conflicted with the Library Act formulation that ‘Libraries in the public library system shall promote the development of a democratic society by contributing to the transfer of knowledge and the free formation of opinions’, 70% of the respondents strongly disagreed. None chose to strongly agree.

Next was asked whether political discussions in the municipality have conflicted with the Library Act formulation that ‘Library activities shall be available to everyone’. Like the previous question, 68% of the respondents strongly disagreed. Notably, 4% did strongly agree.

On asking whether political discussions in the municipality have conflicted with the Library Act formulation that ‘Libraries in the public library system shall devote particular attention to persons with disabilities, including by offering, based on the varying needs and prerequisites of such persons, literature, and assistive technology so that they are able to gain access to information’, an even higher portion (86%) strongly disagreed. None did strongly agree.

Answers for the last question in this part of the survey differ considerably compared to the answers for the previous three questions. This concerns whether political discussions in the municipality have conflicted with the formulation that ‘Libraries in the public library system shall devote particular attention to national minorities and persons with a native language other than Swedish, including by offering literature in 1) the national minority languages, 2) other languages than the national minority languages and Swedish, and 3) easy-to-read Swedish’. Here, only 60% of the respondents strongly disagreed, and 7% strongly agreed. Thus, there is a considerably higher number of respondents who had experienced some sort of opposition or conflict in this area since the election in 2018.

In the free-text comments of this section, respondents mention how the issue of linguistic diversity is cause for debate, for example when a library trained its staff in everyday Arabic, or when prioritising foreign languages are mentioned in local library plans. The controversial nature of issues connected to cultural diversity is also reflected in the fact that many complaints against public libraries submitted to the Parliamentary Ombudsman (Justitieombudsmannen) are related to migration and cultural diversity (Sundeen and Blomgren, 2020). Other, seemingly conflicting, points of view are also brought forward, illustrating the challenges connected to working in institutions that are governed by (local) politicians:

We have mostly experienced a difficulty in maintaining arms-length distance to our politicians as they have wanted to engage in what we do. That is, they haven’t limited their mandate to what we should do, but sometimes also how and when we should carry out what has been decided (11).

I would have been happy if politicians at all showed interest in discussing our activities. Rather, the problem is that they don’t really engage but leave it completely up to us. A bit of resistance would have been fun! (14).

Political pressure

The last section of the survey focuses on concrete examples of political pressure of illegitimate nature, that is outside of the legitimate political channels. On asking ‘Have you or any of your library co-workers experienced that you have been the target of what can be described as “political pressure” of a sort that lies outside of the formal structures of decision-making in your municipality?’, 86% of the respondents answered no, and 14% answered yes. Among these, a majority indicated that the political pressure concerned programme activities (63%). Remaining answers differ between for example political pressure in relation to re-organisations (11), pressure from private citizens (49), or media outlets (55).

Those who have been the source of these instances of political pressure are mostly political decision-makers acting outside of their official mandate, or individual library users. The occurrence of these instances of political pressure varies, but overall recurrence seems fairly low. One respondent indicated that instances of political pressure had been followed by threats of repercussions directed towards him/her or other library co-workers.

The free-text comments provided by respondents in this section of the survey provide some indications of the nature of the political pressure experienced. Several examples of political pressure are related to library activities connected to cultural diversity and foreign languages, such as storytelling in Arabic, or acquisitions of Arabic literature. In many cases, political pressure is exerted via social media and in two cases through the library Facebook page:

I have received comments from politicians about what activities we should offer, and we have received angry unlikes on Facebook posts about LGBT-books or our Pride Week, from SD-politicians in the municipality (5).

Offensive and racist comments on the library’s Facebook flow after posts about activities for new Swedes. But then against the activity as such rather than against the staff (44).

In another case, one library manager mentions being contacted by one of the main web-based alternative radical right media outlets in the country:

I have been called by media, [name of media outlet], and exposed in their blog (55).

Concluding remarks

Results from the library manager survey indicate that the interplay between libraries and the local political level in Sweden is experienced as mostly well-functioning, although notable exceptions exist. Importantly, there are no clear tendencies when it comes to changes in this interplay since the election in 2018.

In the second part of the survey, the correspondence between national cultural- and library policies and politics of the participating municipalities is perceived as high. However, the paragraph from the Library Act about particular attention to national minorities and persons with a native language other than Swedish causes notable opposition between the local and the national political levels.

From the third part of the survey, we learn that illegitimate political pressure is uncommon, but when it occurs, it is often connected to issues pursued by radical right-wing parties, particularly regarding critique of cultural diversity and the rights of sexual minorities.

Results from this study indicate a need to further investigate the intersection of (national) policies and (local) politics in line with what has been requested by previous research such as Jaeger et al. (2013). It also brings to attention the need to further investigate experiences of various aspects of political pressure in day-to-day activities in public libraries through in- depth qualitative inquiry, and through longitudinal studies.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Crafoord Foundation (ref. no. 20210680). The authors would like to thank the participants of the study and acknowledge the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

About the authors

Fredrik Hanell holds a PhD in Information Studies and is Senior Lecturer at the Department of Cultural Sciences, Linnaeus University, 35106 Växjö, Sweden. His research focuses on public libraries as actors in a democratic society and media and information literacy in digital settings. He may be contacted at: fredrik.hanell@lnu.se

Joacim Hansson is Professor of Information Studies at the Department of Cultural Sciences, Linnaeus University, 35106 Växjö, Sweden. He has published extensively on issues concerning the ideological and cultural identity of public librarianship. He may be contacted at: joacim.hansson@lnu.se

Hanna Carlsson holds a PhD in Information Studies and is Senior Lecturer at the Department of Cultural Sciences, Linnaeus University, 35106 Växjö, Sweden. Her research interests include roles and challenges for public libraries in contemporary society and media and information literacy in digital settings. She may be contacted at: hanna.carlsson@lnu.se

References

- Aabø, S., Audunson, R. & Vårheim, A. (2010). How do public libraries function as meeting places? Library & Information Science Research, 32(1), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2009.07.008

- Audunson, R., Andresen, H., Fagerlid, C., Henningsen, E., Hobohm, H-C., Jochumsen, H., Larsen, H., & Vold, T. (Eds.). (2020). Libraries, archives and museums as democratic spaces in a digital age. De Gruyter.

- Buckland, M. K. & Takayama, M. (2021) Ideology and libraries: California, diplomacy, and occupied Japan, 1945-1952. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Buschman, J. & Leckie, G.J. (2007). The library as place: history, community, and culture. Libraries Unlimited.

- Carlsson, H. & Rivano Eckerdal, J. (2018). Det osynliggjorda arbetet: konflikter och möjligheter för (folk)bibliotekariens kompetenser i en politiskt turbulent tid. In J. Hansson and P. Wisselgren (Eds.), Bibliotekarier i teori och praktik: utbildningsperspektiv på en unik profession. BTJ Förlag, pp. 191–208.

- Hansson, J. (2010). Libraries and identity: the role of institutional self-image and identity in the emergence of new types of libraries. Chandos.

- Jaeger, P. T., Bertot, J. C., & Gorham, U. (2013). Wake up the nation: public libraries, policy making, and political discourse. The Library Quarterly, 83(1), 61-72. https://doi.org/10.1086/668582

- Lindsköld, L. (2015). Contradicting cultural policy: a comparative study of the cultural policy of the Scandinavian radical right. he Nordic Journal of Cultural Policy, 18T(1), 8-26. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN2000-8325-2015-01-02

- Mounk, Y. (2018). The people vs. democracy: why our freedom is in danger and how to save it. Harvard University Press.

- Olsson Dahlquist, L. (2019) Folkbildning för delaktighet: en studie om bibliotekets demokratiska uppdrag i en digital samtid. (Lund University PhD Dissertation)

- Pilerot, O. & Lindberg, J. (2018), ’Sen går jag hem när det stänger’: en studie av nyanländas biblioteksanvändning. Länsbibliotek Uppsala.

- Rivano Eckerdal, J. (2017). Libraries, democracy, information literacy, and citizenship: an agonistic reading of central library and information studies’ concepts. Journal of Documentation, 73(5), 1010–1033. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-12-2016-0152

- Rivano Eckerdal, J. & Carlsson, H. (2018). Styrdokumenten i vardagen: en undersökning av kulturpolitiska styrdokuments strategiska och praktiska betydelse för folkbibliotek i fem skånska kommuner. Lund University.

- Rydgren, J., & Van der Meiden, S. (2019). The radical right and the end of Swedish exceptionalism. European Political Science, 18(3), 439-455. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-018-0159-6

- SFS 2013:801. Bibliotekslagen (The Library Act in the Swedish Code of Statutes), 2014-.

- Smith, D. E. (Ed.) (2006). Institutional ethnography as practice. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Sundeen, J., & Blomgren, R. (2020). Offentliga bibliotek som arena för aktivism. The Nordic Journal of Cultural Policy, 23(2), 159–179. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2000-8325/2020-02-06

- Swedish Library Association. (2015). Promoting the development of a democratic society: the Swedish Library Act according to the legislator. Swedish Library Association.

- Torstensson, M. (2012). Framväxten av en statlig folkbibliotekspolitik i Sverige. In A. Frenander and J. Lindberg (Eds.), Styra eller stödja? Svensk folkbibliotekspolitik under hundra år. Högskolan i Borås, pp. 89–134.