Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science, Oslo Metropolitan University, May 29 - June 1, 2022

Teenagers in the library: participatory mediation practices

Janicke Stensvaag Kaasa, and Åse Kristine Tveit

Introduction. In their efforts to reach out to teenagers, libraries facilitate different literary activities where youth come together, socialize and interact. In what ways do these practices contribute to the building of literary and social communities among the participating teenagers and to a broadened understanding of the concepts of libraries?

Method and Analysis. This paper examines three different cases of participatory mediation activities in Norwegian libraries: a podcast, a voluntary reading group and a shared reading activity. The method used is qualitative interviews, and the findings are discussed in relation to theories on the social and participatory dimensions of cultural institutions and to a model from library and information theory.

Results . In the cases presented, the libraries facilitated the activities as part of their strategies. The study sheds light on how the mediation practices in question contribute to fostering literary and social communities among the participating teenagers.

Conclusion. The present study demonstrates possible ways of expanding the understanding of what a library means to young people in a contemporary context.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/colis2217

Introduction

To some librarians, teenagers represent a problem, either because of their ways of using the library or, more often, because of their non-use. Statistics on the number of visitors to public libraries in Norway show a distinct decline in library use when the eager child users enter their teenage years (Statistisk sentralbyrå, 2017). Finding well-working strategies for reaching out to teenagers is a constant challenge to both public and school libraries in the Nordic countries (Hedemark, 2018 ; Sommervold, 2009 ). In accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, libraries are now developing or facilitating activities where young people may express themselves and their opinions on matters affecting them, such as literature and other media. Concerning the methods by which libraries’ media are presented or mediated, the young users are to an increasing degree invited to take part in ways they may find interesting and/or challenging. This change in library services and the growing focus on young people’s participation has so far received little interest in library and information research.

In this paper, we examine teenagers’ participation in three different physical practices of literary mediation in the library, specifically a reading group, a shared reading activity and a podcast production group. In this context participatory mediation practices refer to activities in which users are actively taking part in the mediation of literature and culture in a library context. What, we ask, characterizes the teenagers’ participation in these practices, the way in which they talk about and mediate literature and their reading experiences in a library context?

The paper poses the following two research questions:

- In what ways do these practices – the reading group and the podcast production in particular – contribute to the building of literary and social communities among the participating teenagers and to a broadened understanding of the concept of libraries?

- What are the objectives of the participatory activities in the reading group and the podcast group respectively, seen from the librarians’ and from the teenagers’ perspectives?

The paper is structured as follows: The presentation of the method and procedure used is followed by some theoretical considerations and perspectives from library and information theory. We then present our findings related to our research questions, on the three issues: social processes, library strategies and learning, before discussing our three cases of literary mediation practices and, in brief, their possible implications both for library practice and further studies. The results of this study will add to the knowledge of the social nature of reading, of literature and of the library’s role as a facilitator of both literary and social communities among teenagers. By extension, the paper sheds light on underexplored practices of literary and cultural mediation in the library, aimed at and involving the participation of teenagers.

Methodology and procedure

In order to get information from the various actors in the participatory mediation practices mentioned above, we established contact with a high school library and a public library that facilitate literary activities for teenagers. Unfortunately, our plan to make overt, physical observations of the reading group and the podcast production group had to be discarded due to covid 19 regulations. Initially, two online interviews were conducted (using zoom), one with a high school librarian in charge of both a school-based voluntary reading group and a shared reading activity, and one with a librarian in charge of a teenage podcast production group at the public library. Later, two additional online interviews were conducted with some of the teenagers in question; one interview with two members of the voluntary reading group at the high school and a second one with two members of the podcast group. The qualitative interviews were based on semi-structured interview guides developed from the research questions presented above. Although the interview questions varied slightly with the informants, they were all oriented towards the teenagers’ experiences of participating in library-based activities; their experiences of developing social communities through this participation, and the librarians’ attitudes to these activities as a strategy and a priority in the library services. Regarding the reading group and the podcast group, both the teenagers and the librarians in charge have presented their views, but when it comes to the shared reading activity, we rely only on the voice of the school librarian. According to our agreement with the informants, the interviews were recorded before being transcribed and anonymised. The interviews, lasting from 30 to 40 minutes, were later deleted. The transcriptions were categorized according to the issues mentioned above.

The informants’ comments included in the paper are translated from Norwegian by us. We refer to the different informants’ utterances using P1 and P2 for the podcast teenagers, R1 and R2 for the reading group members, SB for the school librarian and PB for the public librarian.

Theoretical considerations and perspectives

Communicating through social media to keep in touch with friends, get information, news, and entertainment, and present themselves to the world, both visually and verbally, forms an important part of teenagers’ daily life. Even so, face-to-face communication is a significant part of young people’s lives, according to a recent study in psychology (Bekkhus et al., 2020 ) arguing for the importance of physical contact for young people’s well-being, mental health and feeling of belonging.

Cultural institutions follow the development in communication habits and usages, and invite their audiences to be interactive, to socialize and to take part in different ways. In Norway, recent examples of such initiatives are the new Munch Museum’s weekly youth collective, where teenagers specifically are invited to participate physically in creative activities, and the Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art’s smell-based exhibition by Sissel Tolaas, where the visitors used their noses as much as their eyes, and a shared sauna and a swim was included. The social dimension of cultural institutions, as illustrated in the examples above, is a central point in Nina Simon’s The participatory museum (2010). Simon writes about user participation in libraries and museums from a broad perspective, and ‘define[s] a participatory cultural institution as a place where visitors create, share, and connect with each other around content’ (p. ii). She underlines both creative and social activity, but not of any kind; activities should be related to the content of the institution.

Theory and research in library and information science concerning library use perceive the library as a social venue, focusing on communication between librarians and users, and among the users themselves (Audunson, 2004 ; Buchman & Warner, 2016 ; Fagerlid, 2020 ). Even a general understanding of what a library essentially is underlines its social aspects. Norwegian library researcher Ragnar Audunson (Frisvold, 2020 ) describes a library as an institution based on organized collections of documents that initiates social processes related to learning, knowledge sharing, and mediation of culture. In this context the term social processes points to human interaction causing intellectual or interpersonal development, either one-to-one or within a more or less formal group. Like Simon, Audunson links these processes to the institutions’ content. Furthermore, this understanding is mirrored in the latest revision of the Norwegian library legislation, effective from January 2014, stating that the public library should be ‘an independent meeting place and arena for public discussions and debates’ (The Public Libraries Act, 2014).

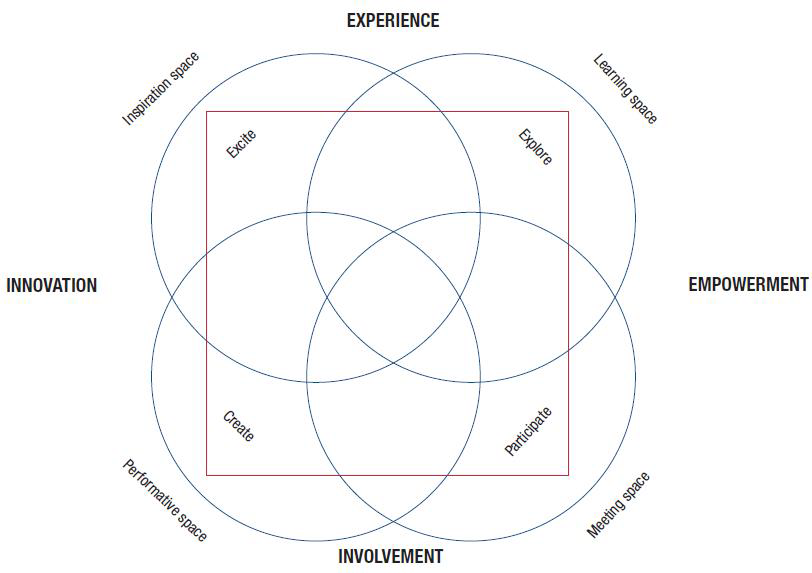

A model of the contemporary public library developed by three Danish library researchers includes the meeting space, as emphasised above, as one of four basic spaces that a library offers its users (Jochumsen et al., 2012 ). The model was proposed as a framework for discussion and analysis of values and priorities in the libraries at a time when societal changes challenged the traditional understanding of a library’s role. In the model, the meeting space is equated with the learning space, the inspiration space and the performative space, and the four spaces are seen as supporting these four goals: Involvement, empowerment, innovation and experience.

Figure 1: The four spaces of the public library (Jochumsen et al., 2012)

In the following, the model, together with the theoretical perspectives presented above, will constitute a framework for understanding the position and the potential of the presented participatory activities facilitated by the libraries. Moreover, it will serve as a point of departure for reflecting upon the libraries’ strategic work to reach out to teenagers and the social processes involved in teenagers’ participation in literary communities in libraries.

For teenagers, by teenagers: three practices of literary mediation

In this study, we are concerned with three different practices of participatory literary mediation: A voluntary reading group, a shared reading activity and a podcast production group. The first two are organized in a school library located at a high school in a middle-sized city, the latter is organized in a public library, located in a small town. Whereas the reading group and the podcast production are voluntary activities outside of, although not disconnected from, a school context, the shared reading activity is organized as a mandatory part of the teaching. Thus, it has a different set of circumstances and implications for the literary mediation. Because of this difference, and because we have not been able to interview the teenage participants in the shared reading activity, our emphasis will be on the reading group and the podcast production. Nevertheless, the interviewed school librarian provided several important reflections on the shared reading activity, also in comparison with the reading group that takes place at the same school, which we find relevant to the understanding of library practices in general and of literary mediation involving teenagers more specifically.

Before we go on to present and discuss the findings of our study, we will briefly lay out the conditions and circumstances of the three specific activities and how they are organized and executed, based on the information from the qualitative interviews with the librarians and the participating teenagers.

The reading group is initiated and run by five students (16 years old), with the assistance of a librarian and a teacher and takes place approximately once a month on a drop-in basis. As such, it is an example of a voluntary reading group in a school library context. Such groups have proven important to the fostering of reading for pleasure and the joy of talking about reading experiences with fellow readers (Cremin & Swann, 2016). The students in the group choose the texts themselves, drawing lots from the suggestions of the participants (their reading list as of December 2021: Stephanie Garber: Caraval, Maja Lunde: Bienes historie / The History of the Bees and Neil Gaiman: American Gods). Although it is voluntary and a student initiative, the reading group is organized at the school, in the school library during the lunch break. The students have explicitly asked the librarian and a teacher to be present during the session, not necessarily to regulate the conversation, but to get the conversation started, and in order for the students to gain more from the reading experience and to learn more in their conversations about the chosen texts.

The shared reading activity takes place in the same school library but within a very different context. For one, the activity is not voluntary, but mandatory, and it takes place during class with groups of about half of the students (app. 15 students). In this activity, the students do not choose the texts themselves but are presented with texts chosen by the librarian that they are to read and talk about there and then. The texts, however, are not linked to the curriculum and are not part of the teaching. As such, it is in line with shared reading as presented and taught by The Reader Organization (Davis, 2011 ) as a path to personal growth through reading that is not well suited to fulfil defined learning objectives. Shared reading is not a prepared activity like the reading group, which requires the participants to read before they meet. Moreover, the students that participate in shared reading activities do not necessarily have an interest in literature and reading. Nevertheless, in the experience of the interviewed librarian, shared reading often activates students who are not avid readers.

The podcast production takes place at a public library. A podcast is defined as ‘a series of digital audio files (voice recording), distributed over the internet, released with episodes and downloaded through web syndication’ (De Sarkar, 2012 ). The increasing production of podcasts by library staff in cooperation with the library users themselves is a strategic way of communicating with others, young and old. Podcasting is easy to do and is commonly used to describe and promote library services or resources (Bradley, 2015 ; De Sarkar, 2012 ; Thomas, 2019 ). During the last decade, several Norwegian libraries have started their own podcasts (i.e., Deichman Majorstuens podcast and BoBcast). Few of these, however, are targeted at teenagers, and even fewer are made by teenagers.

The podcast group consists of six participants (15 years old). They were recruited by the librarian from students who had school library as an optional subject, and they are paid to make the podcast episodes (in total 10 episodes, approximately 5-15 minutes each) that the library publishes on its website and makes available through Spotify. There are usually two or three participants for each episode. After a quick training from the library staff, the teenagers in the podcast group have been free to choose the topics they want to talk about and the books and films they want to include. They have not been obliged to choose from the library’s collection. The project has been financed by the EU project Read on throughout 2021 and will continue with funding from the library. The library in question has a podcast studio and employees with the necessary technical competence. One of the library staff edits, adds the theme song (“jingle”), and publishes the episodes. The library already has experience in making podcasts by adults for both children and adults and has a well-equipped recording studio for this purpose.

Findings

Social processes

When asked about their motivation for participating in the podcast, one of the two informants in the podcast group referred to the excitement of talking about books and the useful experience of recording a podcast but also emphasized the podcast as an opportunity for the participants to reach out to other teenagers and to broadcast their opinions on books as well as on social issues: ‘Well, it is fun to tell someone about your opinions or ideas that they may not have considered’ (P1). When asked about what they liked best about participating in the podcast, the other informant answered: ‘To know that other people are listening to you’ (P2).

Reaching out to other teenagers constitutes a somewhat different objective and motivation than the one communicated by the reading group participants, which of course is related to the different forms of participatory mediation practices we study here. The teenagers in the reading group were first and foremost motivated by talking about the books they had read within the group and learning from the other members’ reading experiences. The teenagers in the podcast group, too, mentioned this both as a motivation for and as an outcome of the podcast production: ‘Now I understand more of what books they prefer, and I know more of their serious thoughts’ (P2). Still, they were very much aware of – and mainly motivated by – their conversation being made available to others. In this way, the podcast group can be said to involve two kinds of communities, namely that of the podcast group, and that of the podcast listeners. As mentioned previously, the participants in the podcast group are not obliged to choose from the library collection (which is also the case for the reading group). To our question about how they decide what to talk about in the podcast episodes, the informants responded that the topics often came first, and then they went on to choose books and other media that they deemed relevant to the topics. There seemed to be a mutual understanding between the podcasters when it came to picking the most relevant books.

In the reading group, the school librarian considers the atmosphere to be accepting, fostering a kind of solidarity among the members. Her views are shared by the two student informants who both mention that the group is a place for them to talk to others about the books they read, and to learn from the other participants. One of the student informants says that she ‘simply has no one to discuss books with outside’ [of the reading group] (R2). Moreover, both of them mention how the group is an opportunity to read books they normally would not choose themselves:’…in the reading group you get to read books you never thought of. And suddenly you end up reading something very interesting, like American Gods, the one we read now’ (R2).

Library strategy

The school librarian and the teenagers from the reading group stated that this activity had its natural base in the school library, despite its voluntary character and despite it being a student initiative. One of the teenagers mentioned the school library as a fitting venue for the reading group because ‘there is no disturbance from the classrooms, you are at peace there, kind of, and you have the books for inspiration. I think it is a very good place to gather’ (R1), referring to the calmness of the room.

The shared reading sessions also took place in the school library. When asked if the sessions should be included in the teaching plans in Norwegian classes, however, the school librarian said she doubts if this would work. Even though these sessions take place within school hours, the librarian very much emphasises the importance of shared reading as something different from the teaching and the curriculum, and as something that is not a means to fulfilling defined learning objectives. Rather, she finds shared reading to be a brilliant tool in a school library for discussing literary form and content, but even more for bringing up the students’ life experiences and, as one of the students who took part formulated it, ‘for getting to know each other on a deeper level’ (SL). In the librarian’s opinion, it is not the texts themselves that generate interest and enthusiasm – or fail to do so – but the group dynamics: A text that works well in one group, does not in another. As such, the choice of texts does not seem to guarantee anything.

According to the public librarian, the podcast is part of their library strategy, embodied in their action plan. ‘User participation is highly valued here’, she says and explains that the podcast is just the beginning of their ongoing strategy to reach out to young people through young people. The librarian underlines that ‘[t]his is vital, to get to the young people, who are the future’ (PL), and elaborates on how this reaching out activity may in turn lead to young people redefining the understanding of what a library is.

Although the podcasts could be about anything the participants choose and do not necessarily have to be based on the media collection, the podcasts in turn become part of the collection.

Learning

The reading group was established by the students as a voluntary activity in their lunch break, and as such, it is not part of the formal learning process. Even so, the school library setting and the participation of the teacher and the librarian, make this an informal learning practice. The librarian reflects upon this: ‘I think they want to get the adults’ view, to offer them a wider perspective on literature. I think they find that they learn a little, without that being the point – it is not an academic thing, but still, they learn something’ (SL). She adds that the adults also learn from the students and that they discover new features of the text. The participating teenagers stress the learning aspect, too: When asked if they benefit from the reading group in their schoolwork, one of them reflects: ‘Through all reading one may be better at formulating, get new words that I may use myself later on […] So yes, in the end, it does benefit school work, but maybe more so; that one even develops one’s thoughts and reflections, by talking about what is read.’ (R1). Yet, as the other informant states, the reading they do for the reading group is ‘not scholarly reading, it is reading for fun’ (R2), and very different from the reading they do in a classroom context.

The podcast production is not organized within a school context, but learning is nevertheless an aspect that is emphasised by the participating teenagers. One informant from the podcast group stated that she learnt a lot from this work: ‘It was very instructive, really. To learn how to make recordings and stuff, to plan what to talk about, putting down keywords and so on’ (P1). The other informant had a wider perspective on learning: ‘Maybe we can teach other teenagers something, issues other teenagers experience, like LGBT experiences that they may not have heard about or know anything of’ (P2). Listening to the podcast, it becomes clear that the teenagers are especially interested in issues of gender and sexuality, which is a topic in several of the episodes. This, in turn, has an impact on their choice of books and films (such as Andre Aciman’s Call me by your name (2007) or fragments by Sapfo), and on which aspects of these works they are interested in discussing. In this way, the podcast production, the selected topics, books, and films become part of the teenagers’ ambition to learn and to teach others.

Discussion

To structure our discussion in a way that is relevant to our research questions and theoretical approaches, we consider the teenagers’ participation in the specific literary mediation practices through the same three perspectives as those in the “Findings” part: 1) social processes, 2) library strategy and 3) learning.

1. Participation, motivation and social processes

The social aspect of the participatory mediation practices in question is closely intertwined with the teenager’s participation in these activities, and their possible experiences of taking part in a community through this participation. The social processes and communities, however, vary with the activities.

In our interview with the school librarian, she reflects upon the differences between the shared reading activity and the reading group. In the shared reading sessions, located in the school library, the leader, in this case, the school librarian, reads aloud while the students listen and comment upon the texts afterwards. As these groups have been mandatory so far, and have taken place during class, the level of active participation varies greatly. The librarian noticed that the boys dominate the conversations and that the most eager ones are not at all library or book lovers. This makes a contrast to the voluntary reading group; the librarian states: ‘In that group, you meet the people who read, who love literature and reading. In a way, there is so much more to a shared reading session’ (SL). This observation points to a possible change in attitudes towards reading among the shared reading participants, and at the same time to the unpredictable status of the sessions.

As noted above, the reading group encourages the students to read books they would not have chosen themselves. In this way, the group does not merely cater to the teenagers’ literary preferences and interests, it also provides the opportunity to get to know new books, new authors, and, as one of the teenagers expressed it, ‘to get to know the others’ thoughts’ (R1). These statements express a way of looking at the reading group as a community that is based on common interests but not necessarily on an assumed agreement about what is a good read and what is not.

The podcast production does not entirely follow Simon’s (2010) notion that social and creative activities in participatory cultural institutions should be centred around the content of the institution as such. The group was free to choose both the works and the media they wanted to talk about. Yet, as the teenagers themselves state, most of the podcast episodes are centred around books (and films), and in their opinion they work best when centred around such content. Although they might not always choose specific titles from the collection, the content of the podcast is surely relevant in a library context: Indeed, the teenagers’ free choice of books shows another form of participation in the sense that it has an influence on the libraries’ content, as their chosen titles will be added to the collection, along with the actual podcast productions.

2. Participation as a strategy and a way of working for libraries

In our interview with the librarian in the public library, she pointed out how teenagers were a notoriously difficult group for the library to reach, and how the podcast – and the direct communication between teenager producers and listeners – was a strategic attempt to reach this group. In this way, the objectives of the library coincide with the above-mentioned motivation of the teenagers: both want to reach out to other teenagers.

In the framework of the four-space model, the reading group and the podcast production fall within all four overlapping spaces of the library: Both can be considered meeting spaces and performative spaces of empowerment, involvement and innovation. The performative aspect, however, is perhaps most prominent in the podcast production because the participants create content that is made available to a larger audience through ‘a platform for mediation’ (Jochumsen et al., 2012 , p. 593). Furthermore, the interviews show how both the reading group and the podcast production are inspirational spaces, in the sense that they provide ‘meaningful experiences’ (p. 590), and learning spaces, in the sense that they give the participants ‘experience and empowerment’ (p. 591). Experience and empowerment, however, take different forms in the two practices: The participants in the reading group were preoccupied with the activity as an opportunity to talk about their own, - and learn from the other participants’ – opinions and reading experiences, whereas the podcast participants were more concerned with their position as podcast producers and their opportunity to share their thoughts and opinions with an audience. As such, the podcast can be seen as a practice that transgresses the four-space model: Indeed, the meeting space can take a variety of forms, both live and online (Jochumsen et al., 2012 ). Yet, the podcast in our study illustrates how a meeting space, in the sense of a physical space where people meet (here, the participating teenagers and possibly the library staff) extends into being a non- physical meeting space, also including the listeners (in this case, most likely other teenagers). Additionally, the podcasters represent another transgression of the four-space model by taking part in library programming and literary mediation practices as paid co-workers: Despite the pay being, according to the librarian, symbolic, one of the teenagers mentioned payment first in response to our question on what they liked best about making the podcast.

The school librarian and the public librarian alike express enthusiasm and personal engagement in the participatory activities they facilitate. Talking about her recent training in the shared reading method, the school librarian remarks: ‘suddenly I remembered why I became a librarian. It is about sharing and mediating literary experiences’ (SL). Both the shared reading sessions and the podcast group are results of the librarians’ initiatives and appear to be depending on their continued engagement, although these initiatives are strongly supported by their respective leaders as part of the school’s and the public library’s strategies.

3. Participation and learning

To varying degrees, learning is an important aspect of all the three activities we discuss in this paper. The shared reading activity, being mandatory and thus intertwined with teaching, is perhaps the most obvious example of learning in a participatory literary mediation practice. But learning is also a motivation, albeit secondary, for the interviewed teenagers in both the reading group and the podcast group. A school library is part of a learning environment and thus shares its goals with the overall education policy, as expressed in the national curriculum. The revised Norwegian national curriculum does indeed point to social learning, learning in depth and exploring as important parts of the basic education:

The ability to understand what others think, feel and experience is the basis for empathy and friendship between pupils. Dialogue is crucial in social learning, and the school must teach the value and importance of a listening dialogue to deal with opposition. […] Learning to listen to others and also arguing for one’s own views will give the pupils a platform for dealing with disagreements and conflicts, and for seeking solutions together. (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2020).

The Norwegian national curriculum’s emphasis on empathy, dialogue and learning to listen to other students’ views, while developing arguments for one’s own opinions, are all elements present in the reading group discussions. According to the school librarian, there are not usually very differing opinions of a book, but different nuances are debated. She adds: ‘Some are skilled in argumentation, others have to learn it, but I notice that after some time, they dare to take part’ (SL).

Moreover, the elements mentioned above are also reflected in the podcast production and in the participating teenagers’ wider perspective on learning and on the podcast as a way to facilitate dialogue and exchange views and opinions.

The teenagers’ participation in the reading group and the podcast group, then, seems to be partly motivated by learning, but they all stress how their main motivation is the opportunity to get together to discuss and share their reading experiences — and to have fun.

Implications for library practice and further research

The librarians’ and teenagers’ experiences with these three literary mediation practices may inspire other librarians in both public and school libraries to try them out in their efforts to reach out to teenagers. In our view, they also show how strategic library planning may include the participation of young voices to ensure that the activities intended for young people are well-targeted.

Recent years’ development in communication technologies and the changing ways in which especially young people socialize and communicate, open up an interesting area of study to library and information researchers. Libraries that make use of these technologies and facilitate participating activities in cooperation with their users point to new mediation practices and new possibilities of developing communities, physically and digitally, as well as to a broadened understanding of the concept of libraries and of actual libraries. The implications for the libraries as developers of social citizenship, particularly that of young people, should be of interest as a subject for further research.

Conclusion

The concept of libraries, be it school libraries or public libraries, increasingly includes users and users’ participatory activities, which involve social processes and the building of communities. Libraries open spaces for youth who want to take part, to perform and to come together and share with, as well as learn from, their peers. In the cases presented above, the libraries facilitated the space, the technical equipment and the expertise needed, in addition to the supply of books that made up the basic materials for the reading group and the podcast group. The activities were thus related to the libraries’ content, as expressed by Simon (2010), and in the podcast production, the users’ activity even created new content for the library to share with other users.

The present study demonstrates possible ways of expanding the understanding of what a library means for young people in a contemporary context. A library has always been a place where people meet, interact and develop new knowledge and aesthetic experiences based on the present media collections. Today, a library may also be conceived as including media contributions by the users, presented by the users, and as a meeting place where users facilitate activities of their choosing. When it comes to teenage users, libraries have started to explore the potential in participatory mediation of literature and culture that may appeal to young people’s media practice. Encouraging and welcoming participatory activity in the library may foster young people’s further participation in civil society and hence contribute to local democracy.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the participants for sharing their opinions and personal experiences.

About the authors

Åse Kristine Tveit

is Associate Professor at the Department of Archivistics, Library and Information Science at Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway. Tveit teaches children’s literature and children’s librarianship. Her research interests are mainly concerned with children’s reading and sociology of literature. Can be contacted at aasekt@oslomet.no

Janicke S. Kaasa has a PhD in Comparative Literature, and currently holds a position as Associate Professor at the Department of Archivistics, Library and Information Science at Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway. Among her research interests are book and reading history, children’s literature and sociology of literature. Can be contacted at janickek@oslomet.no

References

- Act relating to public libraries (The Public Libraries Act). (2014). https://bibliotekutvikling.no/content/uploads/2019/10/4297-EN- nasjonalbiblioteket_bibliotekloven.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20220516103436/https://www.global- regulation.com/translation/norway/5961682/law-on-public-library-%2528public-library- act%2529.html )

- Audunson, R. (2004). The public library as a meeting-place in a multicultural and digital context. The necessity of low-intensive meeting-places. Journal of Documentation, 61 (3), 429–441. DOI: 10.1108/00220410510598562

- Bekkhus, M., Von Soest, T. & Fredriksen, E. (2020). Psykisk helse hos ungdom under covid-19: Ensomhet, venner og sosiale medier. Tidsskrift for Norsk psykologforening, 57(7), 492-501. https://psykologtidsskriftet.no/vitenskapelig-artikkel/2020/06/psykisk-helse-hos-ungdom- under-covid-19 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20220516103754/https://psykologtidsskriftet.no/vitenskapelig- artikkel/2020/06/psykisk-helse-hos-ungdom-under-covid-19 )

- Bradley, P. (2015). Social media for creative libraries: How to use web 2.0 in your library (2 nd ed.).

- Buchman, J. & Warner, D. A. (2016). On Community, Justice, and Libraries. Library Quarterly, 86 (1) 10–24. https://doi.org/10.1086/684146

- Cremin, T. & Swann, J. (2016). Literature in common: Reading for pleasure in school reading groups. In Rothbauer, P., Skjerdingstad, K. I., McKechnie, L. and Oterholm, K. (Eds.). Plotting the reading experience: Theory, Practice, Politics. (pp. 279-299). Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- Davis, J. (2011). The Reading Revolution. In Stop What You’re Doing and Read This, 117–136. London: Vintage.

- De Sarkar, T. (2012). Introducing podcast in library service: an analytical study. VINE. Very informal newsletter on library automation , 42 (2), 191–213. DOI: 10.1108/03055721211227237

- Fagerlid, C. (2020). Democratic coexistence, tiny publics and participatory emancipation at the public library. In Audunson, R. et al. (Eds). Libraries, archives and museums as democratic spaces in a digital age. (pp. 285-304). De Gruyter.

- Frisvold, Ø. (2020). Det strukturerte Ragnarok: Ragnar Andreas Audunson – forsker og folkeopplyser. In Evjen, S., Olsen, H. K. & Tveit Å. K. (Eds.), Rød mix: Ragnar Audunson som forsker og nettverksbygger. (pp. 3-13). ABM Media.

- Hedemark, Å. (2018). Authenticity Matters: The Reading Practices of Swedish Young Adults and Their Views of Public Libraries. New Review of Children’s Literature and Librarianship , 26 (1-2), 76-90. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614541.2021.1971392

- Jochumsen, H., Hvenegaard Rasmussen, C. & Skot-Hansen, D. (2012). The four spaces – a new model for the public library. New Library World , 113 (11/12), 586–597. https://doi.org/10.1108/03074801211282948

- The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2020. https://web.archive.org/web/20220513145830/https://www.udir.no/in-english/

- Read on: Reading for Enjoyment, Achievement and Development of Young people (n.d). https://web.archive.org/web/20220516102220/https:/readon.eu/about/project

- The Reader Organization (n.d.). Shared reading. https://www.thereader.org.uk/what-we-do/shared-reading/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20220513150227/https://www.thereader.org.uk/what-we-do/shared-%20reading/ )

- Simon, N. (2010). The participatory museum. Museum 2.0.

- Sommervold, T., Sjølie, G. & Haugstveit, T. B. (2009). Lesing på ungdomstrinnet: En rapport fra et Gi rom for lesing!-prosjekt. Høgskolen i Hedmark.

- Statistisk sentralbyrå (2017). Norsk kulturbarometer 2016 . https://www.ssb.no/kultur-og-fritid/artikler-og-publikasjoner/norsk-kulturbarometer-2016 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20220513150418/https://www.ssb.no/kultur-og-fritid/artikler-og-publikasjoner/norsk-kulturbarometer-2016 )

- Thomas, S. (2019). Library-Podcast Intersections. Library technology reports , 55 (5), 7-10.