Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science, Oslo Metropolitan University, May 29 - June 1, 2022

Digital first: challenges for public and regional libraries in Sweden

Karen Nowé Hedvall, Malin Ögland, and Jenny Lindberg

Introduction. Between 2018- 2020, Swedish public library staff were involved in the national project Digital First to strengthen their capability to support citizens in developing digital competencies. In this paper we focus on the challenges that staff and management in public and regional libraries experienced while striving to support people’s development of digital competencies.

Method. In 2019 we met with staff and managers of five public libraries in different parts of Sweden for interviews and focus groups. In 2020, 19 online interviews and 18 email questionnaires were carried out with 20 regional coordinators of the Digital First project. The two datasets were combined for a comprehensive analysis, supplemented with data from quarterly reports collected by the national coordinator of Digital First.

Analysis. We conducted a qualitative content analysis guided by the theoretical concepts of institutional logic and legitimacy.

Results. On the municipal and the regional level, library staff offered education and support to users in the development of digital skills. The respondents referred to the Swedish Library Act and to their experience of citizens’ information needs to justify the library’s involvement in these activities. However, prospective users seldom experienced a need for competency development, nor did they regard libraries as sources for help with digital skill-building. Other bodies within the municipal organization (e.g. IT departments) were also often ignorant of the library’s remit and area of expertise in digital skills.

Conclusion. Tensions were identified among the expectations laid out at a national level in policy documents, the needs that library professionals strived to meet in their local work environments, and the expectations of the public. These tensions have complicated the ongoing efforts to justify the relevance of public and regional library work in Sweden.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/colis2221

Introduction

In accordance with the Swedish Library Act (Bibliotekslagen, SFS 213:801), there are public libraries in every municipality and regional libraries in every region of Sweden. Apart from the general mission described in the Swedish Library Act, public libraries are governed by their municipalities. Regional libraries support the public libraries within their region but have no mandate towards them. Generally, public libraries in Sweden must promote the development of a democratic society by advancing the dissemination of knowledge. To this end, public libraries ‘work to increase knowledge about how information technology can be used for knowledge acquisition, learning and participation in cultural life’ (SFS 213:801). Between 2018 and 2020, all Swedish public and regional libraries participated in a project aimed at developing the public libraries’ capability to support citizens in developing digital competencies. The project, called Digital First: with the user in mind (from now on mentioned as Digital First) was assigned to the National Library of Sweden by the Ministry of Culture as one among several initiatives within the framework of the Swedish digitalisation strategy (Kungliga Biblioteket 2021). The Ministry of Culture refers to the Library Act to motivate why public libraries should support citizens in gaining digital skills, stating that ‘library staff are used to reading needs in their surroundings and adapting their efforts to individuals’ demand’ (Kulturdepartementet 2017, p. 2, our translation) and that public libraries enjoy a high level of trust among the public. The idea for the project came from the

National Library of Sweden’s vision of ‘an investment in a broad digital competence development for the entire population with support in public libraries’ (Kulturdepartementet 2017, p.3).

Regional libraries played a central role in the Digital First project, as their staff were expected to engage the public libraries in the aims and coordinate competency development activities for library staff based on the needs of the libraries in their region. A central activity of the project was an online survey which all library staff were encouraged to fill out in the beginning and at the end of the project as a form of self-assessment of their level of digital competencies (Kungliga Biblioteket 2021).

We followed the project from 2018 to 2021 with a focus on how staff at public and regional libraries have shaped and experienced their roles in their local environment when it comes to digitalisation. We studied attitudes and activities concerning digital competencies of the library staff, but also of library users and of the regional support staff (Nowé Hedvall et al.2019; Lindberg, Nowé Hedvall & Ögland 2020; Nowé Hedvall et al. 2021). This paper is based on the research conducted in all of these studies, drawing most prominently from the 2019 study.

In this paper we explore the following research question:

Which tensions do staff and management in public and regional libraries experience when supporting users in developing digital competencies?

We start by discussing how staff and management at Swedish public libraries have worked to support Swedish citizens in gaining digital competencies. We then describe how staff at the regional libraries have worked to support the public librarians in their work. We use neo-institutional theory to analyse the resulting tensions and point at some strategies used to negotiate them.

Literature review

As tax-funded institutions, public libraries must justify their importance to the community, but this is complicated (Gazo 2011; Waller 2008) by the wide range of tasks and stakeholders involved in their operation, which makes it difficult to find a single strategy to prove their relevance (Rasmussen and Jochumsen 2003; Waller 2008; Cusick 2020). Public libraries in Scandinavian countries are often viewed positively by politicians (Audunson 2005) and by the public (Rasmussen and Jochumsen 2003), but their image is of a boring public good (Rasmussen and Jochumsen 2003), restricted to traditional roles of supporting the literary canon through book lending (Audunson 2005, Audunson et al. 2019). While it is important for the legitimacy of an institution to conform to the expectations of the public to some degree, the services of the institution still need to be useful to a changing society (Audunson et al. 2019). Public libraries habitually do this by responding to current trends and to framing their activities around cultural policy (Audunson et al., 2020). Little research concerning the purposes and stakeholders of the Swedish regional libraries that are tasked with supporting public libraries exists. Two Swedish reports (Schultz Nybacka 2013; Pilerot 2019) conclude that the tasks of the regional libraries are varied and complex, and that their mandate towards public libraries is unclear. A focus on relationship building is central to building legitimacy towards those public libraries (Schultz Nybacka 2013; Pilerot 2019).

Since the end of the 20th century, the digital turn in society has confronted public libraries with a strong pressure to adapt (Waller 2008, Cusick 2020). As Maceviciute and Manžuch (2020) argue, roles of public libraries in a digital society depend on their geographical and historical contexts. Proposed roles range from providing physical social meeting places to balance too much digital interaction (Aabø, 2005; Audunson, Hobohm & Tóth 2020) to reducing the digital divide by providing infrastructure and/or training citizens in digital skills (Waller 2008; Jaeger et al., 2012; Real, Bertot & Jaeger, 2014; Bertot 2016; Maceviciute & Manžuch, 2020). In many countries, staff at public libraries have embraced the role set out for them by national policy of promoting the use of information and communication technology by citizens (Waller 2008; Rasmussen and Jochumsen 2003; Jaeger et al., 2012). In Sweden, the “digital imperative” has had a strong impact on cultural policy (Hallpers 2019). Public libraries in Sweden have for the most part already integrated digital collections, technology, and support into their existing operations (Michnik 2018; Olsson Dahlquist 2019). This became more marked during 2020-2021, when public libraries moved a majority of their activities online. However, librarians reported uncertainties and challenges in information security (Johansson and Lindh 2020), legal issues, and the demarcation of professional roles (Michnik 2018; Olsson Dahlquist 2019). Similar challenges were reported and addressed in the Digital First project.

Earlier research details challenges for public library staff related to showing the relevance of their institutions to the public and to local politicians. An increasingly digital society coupled with national policy makers expecting library staff to promote the use of digital tools both create strong incentives for library professionals to change. However, these challenges also offer the possibility of making the library a space that is more visible and representative of its users. As a result, library professionals can be uncertain as to their competencies and their mandates in some areas connected to digital skills.

Theory

In this study, we used concepts from neo-institutional theory to understand how and why organisations – and actors in organisations – evolve in relationship to a wider context (Lounsbury & Yanfel Zhao 2013). This framework suits the study of tensions experienced by library staff working in a digital environment. A central concept in the theory is legitimacy. We adopted the broad definition that “[l]egitimacy is a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions” (Suchman 1995, p.574). In our analysis, legitimacy in an organisation (in this case regional or public libraries) is dependent on two dimensions: perceived expectations and perceived needs. A public or regional library is perceived as legitimate when it offers the services that the library is expected to offer. For public libraries, the audience with expectations may be the public, municipal agencies, and/or national institutions, whereas the regional library strives to fulfil expectations by the public library staff and managers as well as other regional or national agencies. Regarding (perceived) needs, public or regional libraries are perceived as legitimate when they offer services that respond to the needs that exist (or at least are perceived to exist) in a (digital) society. These dimensions of legitimacy can both strengthen and conflict with each other. If libraries offer services that respond to identified needs in the world around them, this can enhance libraries’ legitimacy for their users, while at the same time such services can be perceived as beyond the remit of a library’s expected activities, and therefore an illegitimate use of taxpayer money (see also Michnik 2018).

How library staff strive to legitimise their activities can be further understood through institutional logic: an analytical tool used to understand how individuals in organisations make sense of their work practice and legitimise professional choices when dealing with ambiguous demands or expectations (Thornton & Ocasio 1999; Thornton 2004). Schultz Nybacka (2013) also begins with the concept of institutional logic and develops the concept of ‘assignment logic’ (uppdragslogik) as a specific institutional logic in a library competency development project. The concept describes how librarians in many internal discussions endeavoured to reconcile their practice and their professional values with the help of the abstract policy given in the Swedish Library Act.

In our study, we employ the concepts of assignment logic and legitimacy to better understand how staff at public libraries and regional libraries engage with the expectation of supporting citizens’ digital competencies as expressed in national guidelines in the project Digital First .

Method

For the public libraries in Sweden, we draw on empirical material collected during our study of Digital First from 2018-2021. We conducted case studies of public libraries in five municipalities of varying sizes in different parts of Sweden. In total, we conducted 13 semi-structured individual interviews with library staff and management, five focus group interviews, and three non-participant observations of staff meetings during the spring of 2019. We asked our respondents about activities related to digital competencies at the library, and to reflect upon the role of their library related to the digital turn in Swedish society. To study regional libraries, we use empirical material created by 19 online individual interviews with all regional coordinators of the Digital First project in the spring of 2020. Our empirical data also consists of 18 email responses to a questionnaire formulated in 2020 by researchers Schultz Nybacka and Lund (Södertörn University) about the role of regional libraries in Digital First . We also included quarterly reports collected from all regional coordinators between 2018 and 2020 by the national coordinator. All interviews were transcribed, and we analysed the results based on a qualitative framework using the theoretical concepts described above. The empirical material is in Swedish. All quotes in the results are our translations. Quotes from individual interviews with public library staff are coded PLI-1 to PLI-13 and from focus groups PLF-1 to PLF-5. Quotes from interviews with regional coordinators are coded RCI-1 to RCI-19, from email questionnaires RCQ-1 to RCQ-18, and from the quarterly reports QR-2018-1/2 to QR-2020-4.

Results

Public libraries

In all of the libraries we studied, the staff accepted the assignment expressed in the Digital First project as a natural part of their respective libraries’ mission. The respondents discussed meeting needs at different levels. Through the use of digital services, the general needs of library users could be met more easily. Likewise, the libraries’ digital services could respond to existing needs among citizens who did not yet use the library. Most respondents identified a need among the community to learn basic digital skills, as they saw the risk of a digital divide excluding elderly people, migrants, and people with disabilities from society. Many of the interviewed librarians could also see a need for users to learn more about security on digital platforms or evaluating digital sources. Some librarians still saw a need for analog services and not all were convinced that the digital turn of society was entirely positive. But teaching citizens about digital tools and services was still viewed as important, if only to give people the chance to make informed choices. In general, library staff were reasonably confident that they either possessed the basic digital competencies needed in the organisation as a whole, or that they could learn those skills if necessary, with the help of projects such as Digital First . Although there were other municipal actors such as schools who could meet some of the needs for digital support, in the smaller villages especially the library was one of few public institutions left: ‘There are not many places you can go to get help here. So I think the library is pretty much a given’ (PLI-9). Activities ranged from helping users with their digital errands on a case-by-case basis, to organising courses in dedicated digital centres, to inviting experts to deliver open lectures on aspects of digitisation.

Librarians were motivated by a desire to help people find answers to their questions and did not draw any clear demarcation lines between analog help, digital help, or whether the questions had anything to do with library resources. One staff member described the library itself as basically a service institution, which would help with ‘whatever is needed’ (PLI-9). Giving access to a copy machine or to WiFi was perceived as a digital service as well as helping people ‘to log in to the Swedish Social Insurance Agency [or] when they order a ticket’ (PLI-10). The goal was to be able to ‘help them and do a good job so they are happy and leave here with a book or a movie or their copies’ (PLF-3).

In other words, all of the respondents perceived that there was a need among their users to develop basic digital skills, and they were willing and – for the most part – eager to support users in this endeavour. However, according to respondents, users often did not experience the same need, nor did they regard the library as a possible source for help in fulfilling it. In some more rural districts, the technical infrastructure for a digital life in the municipality is still lacking, which in turn meant that there was little demand for digital support at the library. A respondent asserted that it was ‘a delicate task’ (PLI-1) to create interest in themes such as internet security and detecting misinformation. They perceived a gap between the needs for digital competency development that they would like to meet, and users’ expectations that the library’s support should be limited to transactional service, such as basic media provision and help with copying. It was a challenge for the respondent to treat basic interactions as opportunities for learning, and to sneak education into such service-based interactions.

Other respondents believed that users did not associate education in digital skills – such as the evaluation of digital sources – with the library’s role: ‘maybe they do not expect that ... at the library you still only borrow books. Users do not expect us to know anything about digitalisation’ (PLI-8). Respondents wanted to satisfy the perceived needs of users through digital skills training, but were unsure whether it would give them legitimacy in the community because that activity did not match the users’ image of what a library should provide. In one case, respondents related to us that users assumed believed the library staff would have a negative view of tools (such as tablets) over physical books. These users did not expect library staff to be proficient in digital skills, or to actively encourage the use of digital tools. Even municipal services such as IT departments often lacked awareness about the library staff’s digital capabilities, or their task as described in the Swedish Library Act, or of the Digital First project. In two cases, the public libraries included digital centres on the premises. One group of staff asserted that these centres combat the dilemma of the library’s image: ‘if you have a “Digidel” center it will be much more legitimate to talk about information evaluation [and] technology, because people do not think so about libraries today’ (PLF-6).

In many instances, the library staff had a proactive attitude toward offering digital tools, services, and education to users: ‘If libraries do not break trail, who will? We cannot wait for all our users either, but we must go ahead and show the way’ (PLI-4). Often librarians would design the library’s services and activities based on perceived needs in the local environment, and then seek to shore up the legitimacy of those activities by referencing the Swedish Library Act: ‘We adapt to their needs as well as we can […] this is written in the library act as well, to work with technology to enhance knowledge’ (PLF-6). This demonstrates how librarians can use assignment logic to legitimise choices based on perceived needs and a professional understanding of their mission.

A similar story unfolded in all five public libraries, with local variations. Our empirical evidence confirmed that ‘library staff are used to reading needs in their environment and adapting their efforts to individuals’ demand’ (Kulturdepartementet 2017, p.2). However, the perceived needs and demand are not the same. Likewise, the local information infrastructure is not yet developed fully in all parts of Sweden. Librarians must cope with a tension between the needs they observe for digital support and education in their communities and the relatively low perceived expectations from the public about the library’s ability to meet those needs. All public library staff reported struggling with a lack of expectations among their users and sometimes among other municipal service staff who did not see the library as a natural partner in digital competency development. The library staff that we interviewed strived to create legitimacy for their digital upskilling activities partly by referring to perceived needs in their community, but most often by referring to the Swedish Library Act.

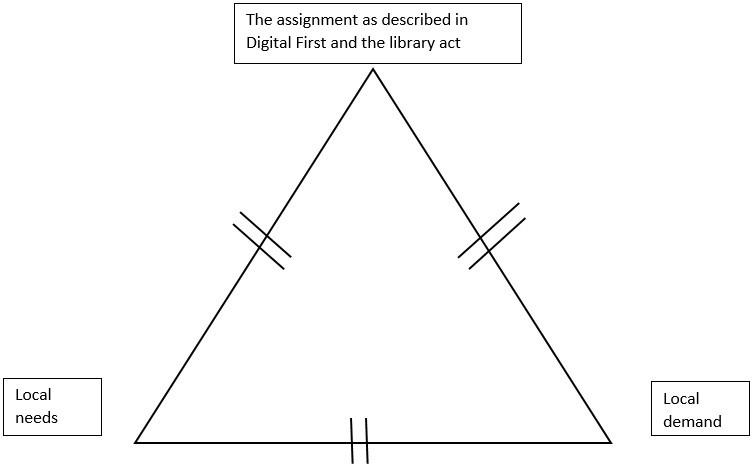

However, since few people working outside of the library environment can be expected to know the contents of the Swedish Library Act, it was difficult for library staff to assert themselves in the municipal environment. Thus, librarians occasionally attempted to sneak competency-development initiatives into their meetings with users. Rather than a need for developing digital competencies, our respondents expressed a need for improved skills in digital pedagogy; i.e., how do you teach digital skills to (sometimes uninterested or reluctant) users? Public libraries also needed support for an increased legitimacy of their mission at municipal level in order to reach their full potential. The tensions can be summarised in the following figure:

Figure 1: Tensions between local needs, local demand and national assignment.

Regional libraries

In Digital First , regional libraries are described as competence and development nodes for public libraries in the area of digital competencies (Kungliga Biblioteket 2021). This is in line with the general mission of regional libraries: to promote cooperation, development, and quality in the public libraries within their region. All regional libraries assigned coordinators who worked within the framework of the Digital First project to support public library staff in developing their digital competencies. Initially, most regional coordinators toured their region with the ambition of offering all public libraries a workshop to discuss the results of a self-assessment test of their level of digital competencies. However, once they were ensconced in the library environments, in many cases the coordinators noticed that not all library staff perceived an urgent need to develop their competencies in all the digital skills listed in the self-assessment tests. Indeed, in the interviews with staff at the public libraries we conducted, few staff members could recall the self-assessment tests or the workshops without prompting. The more experienced coordinators were not surprised by the relative lack of interest. In a quarterly report, a regional coordinator would like to discuss, 'How we motivate library staff, they often have neither the time nor the energy and sometimes no interest in things like this that come from above.’ (QR-2018-1/2)

Most regional library coordinators were aware that they ‘need to be at the forefront of our own competence and development, to be credible towards our target group and to be able to identify existing needs and challenges and not yet quite clear needs and challenges’ (QR-2018-4). As project leaders of the Digital First initiatives, the coordinators saw a more pressing need for competency development than the staff of public libraries experienced. In other words, the needs the regional coordinators wanted to address were greater than the expectations. Many coordinators and managers emphasised the importance of starting their competency development based on the expectations of the staff, and especially the management of the public libraries, ‘playing it cool and waiting for requested areas of knowledge [from the public libraries], not pushing knowledge that is not relevant’ (QR-2019-4). Therefore, they built much of their legitimacy on networking closely with local library staff, in order to start from local needs and expectations. Most coordinators formed groups with library managers and/or staff to help them understand what the public libraries wanted. In this way, most coordinators identified a need that was not primarily laid out in the aims of the Digital First project: to clarify a given library’s mission on a municipal level to benefit local library staff and their users. This was handled by the coordinators to varying degrees, but the identification of the need demonstrates the value of those coordinators working closely with local library staff to make visible the permutations of the Digital First project across different regions in Sweden.

Some regional coordinators tried to involve library managers and staff as much as possible in their projects in order to raise their interest. Other regional coordinators instead tried to make it as easy as possible for the libraries to participate:

We believe that in general, public libraries appreciate when we can offer them ready- made concepts that they can take part in, which do not require as much planning, time and resources of their own. Public library staff often find it difficult enough to cope with all the regular demands on their time, and can be stressed when we at the regional level ask them if they want to be part of x, y, z. (RCQ-6)

This reflects a similar dilemma at the local level, where public library staff wanted to develop the digital skills of users who would rather receive basic, transactional services. A regional coordinator solved the dilemma by ‘sneaking in’ (QR-2020-3) learning activities when ostensibly lending IT equipment to the libraries.

The ignorance about the role of the libraries that was identified at the municipal level is also reflected at the regional level:

…our colleagues in regional development do not know ... we think we have been nagging and nagging, but it takes a while before it lands what we are doing at all. (RCI-17)

Again, similar to the public library staff, regional coordinators referred to the Swedish Library Act and to the assignment in the Digital First project in order to justify activities that they based on their professional expertise and their understanding of local needs. They engage more or less actively with the expectations expressed in the Digital First steering documents, using assignment logic to justify their actions. Even though the Digital First assignment did not add anything substantive to the more general description in the Swedish Library Act, some coordinators experienced that it provided them with a bit more legitimacy in the eyes of both public library staff and colleagues at the regional organization. One regional coordinator stated that they had been perceived by the library staff as having a larger mandate because their role as a development node had been explicitly written in Digital First . Regional library activities had also become more visible in the region’s organisation:

Our role regarding digital competence development becomes clearer, and we envisage a scenario where we at the regional level can take a clearer place in other constellations in the region […] Until now, the region has often forgotten our role as a learning institution, now we gain a stronger voice through the state assignment Digital First , we believe. (QR-2019-1)

In summary, the tensions between perceived local needs and local demands described in the Swedish Library Act that were identified for public libraries are also present at the regional level. This perception of legitimacy relies on hierarchical policy enforcement: Regional coordinators build relationships with their public libraries so that their projects can be accepted as relevant. Staff at regional libraries also refer to national assignments based on policy to legitimize and increase visibility of their actions.

Conclusion

Similar to findings by Waller (2008) and Rasmussen and Jochumsen (2003), the public library staff in this study embraced the role assigned to them by national policy of supporting local users in developing digital competencies. Library staff perceived a need for basic digital competency among their patrons that they were able to fill. However, they also had difficulty making these abilities visible to users and to other municipal actors. The library staff attributed the resistance among users to their perception of the library as a more traditional, transaction-based service organisation (see also Audunson 2005; Audunson et al. 2019). We have expressed this as a gap between perceived needs and perceived expectations. As legitimacy is created both by satisfying actual needs of the general public and by living up to the public’s expected image, this complicated the library staff’s work to show the continuing relevance of libraries. Similar challenges were found at the regional libraries. As earlier research by Schultz Nybacka (2013) and Pilerot (2019) shows, regional libraries have a difficult mandate towards public libraries in general and their staff are well acquainted with the need to legitimise their activities in order to achieve any impact. In the area of digital competencies, staff at public libraries did not always experience an urgent need for digital competency development and regional colleagues did not recognize the coordinators’ roles. One way of legitimising activities both on a local and a regional level was by referring to legislation (see also Audunson et al., 2020), a form of assignment logic. However, public libraries in particular still have considerable work to do as regards legitimising and clarifying their mission in their communities as well as in developing their own digital competencies.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Katarina Michnik of Gothenburg University Library, prof. Pamela Schultz Nybacka of Södertörn University and dr. Arwid Lund of Södertörn University. Katarina participated in the SSLIS research team during 2018 and 2019. Pamela and Arwid authored the questionnaire to regional coordinators and management and gathered the data 2020.

About the authors

Dr. Karen Nowé Hedvall is a senior lecturer and assistant head of department at the Swedish School of Library and Information Science (SSLIS), University of Borås. Her research interests include organizational studies of in libraries as well as information management studies. Karen can be contacted at karen.nowe_hedvall@hb.se.

Malin Ögland is a lecturer at SSLIS, University of Borås. Her research interests include public libraries and their position in society. She may be contacted at malin.ogland@hb.se.

Jenny Lindberg holds a PhD in Library and Information Science from the University of Borås, Sweden. Her research interests include librarianship and information practices, with a critical approach to the relation between people and technologies. She is a Senior Lecturer at SSLIS in Borås, and may be contacted at jenny.lindberg@hb.se.

References

- Aabø, S. (2005). The role and value of public libraries in the age of digital technologies. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 37(4), 205-211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000605057855

- Audunson, R. (2005). How do politicians and central decision-makers view public libraries? The case of Norway. IFLA Journal, 31(2), 174-182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0340035205054882

- Audunson, R., Aabø, S., Blomgren, R., Hobohm, H.-C., Jochumsen, H., Khosrowjerdi, M., Mumenthaler, R., Schuldt, K., Rasmussen, C.H., Rydbeck, K., Tóth, M. and Vårheim, A. (2019). Public libraries as public sphere institutions: A comparative study of perceptions of the public library’s role in six european countries. Journal of Documentation, 75(6), 1396-1415. https://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JD-02-2019-0015

- Audunson, R., Andresen, H., Fagerlid, C., Henningsen, E., Hobohm, H., Jochumsen, H., & Larsen, H. (2020). Introduction. Physical places and virtual spaces: libraries, archives and museums in a digital age. In R. Audunson (Ed.). Libraries, Archives and Museums as Democratic Spaces in a Digital Age. De Gruyter Saur. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110636628

- Audunson, R., Hobohm, H., & Tóth, M. (2020). Professionals and the public sphere. In R. Audunson (Ed.). Libraries, archives and museums as democratic spaces in a digital age. De Gruyter Saur. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110636628

- Bertot, J. C. (2016). Building digitally inclusive communities: the roles of public libraries in digital inclusion and development. In J. Bertot, E. Estevez, & S. Mellouli (Eds.), Proceedings of the ICEGOV'15–16 9th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, 95-102. https://doi.org/10.1145/2910019.2910082

- Cusick, C. J. (2020). Modeling the factors related to public library legitimacy: A comparison of library service and community socioeconomic characteristics. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Gazo, D. (2011). City councillors and the mission of public libraries. New Library World, 112(1), 52-66. https://dx.doi.org/10.1108/03074801111100454

- Hallpers, A. (2019). ‘Allt förändras och förändringarna kommer att fortsätta’: Om synen på digitalisering och det digitala imperativet. Master’s thesis. Högskolan i Borås. https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn%3Anbn%3Ase%3Ahb%3Adiva-21707

- Jaeger, P. T., Bertot, J.C,. Thompson, K. M., Katz, S.M., & DeCoster, E.J. (2012). The intersection of public policy and public access: Digital divides, digital literacy, digital inclusion, and public libraries. Public Library Quarterly, 31(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2012.654728

- Johansson, V. & Lindh, M. (2020). Skyddsvärden i vågskålen : internet på folkbibliotek - ideologi, juridik, praktik. Förvaltningen för kulturutveckling, Västra Götalandsregionen, Kultur i Halland & Biblioteksutveckling Sörmland. https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn%3Anbn%3Ase%3Ahb%3Adiva-23960

- Kulturdepartementet (2017). Uppdraget till Kungliga biblioteket om digital kompetenslyft. Regeringsbeslut I:62.

- Kungliga Biblioteket (2021). Digitalt först med användaren i fokus 2018-2020. Slutredovisning. Kungliga biblioteket. https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kb:publ-77

- Lindberg, J., Nowé Hedvall, K., & Ögland, M. (2020). Folkbiblioteken och den digitala kompetensen : Uppdrag, behov och förutsättningar. Högskolan i Borås.

- Lounsbury, M. & Yanfei Zhao, E. (2013). Neo-institutional Theory. In Oxford Bibliographies in Management. Ed. Ricky Griffin. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Maceviciute, & Manžuch, Z. (2020). Getting ready to reduce the digital divide: Scenarios of Lithuanian public libraries. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 71(10), 1205–1217. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24324

- Michnik, K. (2018). Samhällets allt-i-allo?: Om folkbibliotekens sociala legitimitet. Högskolan i Borås.

- Nowé Hedvall, K., Lindberg, J., Michnik, K., & Ögland, M. (2019). Användarna först med det digitala i fokus : folkbibliotekariers arbete inom den nationella satsningen för ökad digital kompetens. Högskolan i Borås. https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn%3Anbn%3Ase%3Ahb%3Adiva-21858

- Nowé Hedvall, K., Ögland, M., Lund, A. & Schultz Nybacka, P. (2021). Regionala biblioteksverksamheter som kompetens- och utvecklingsnoder i Digitalt först. Högskolan i Borås. https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn%3Anbn%3Ase%3Ahb%3Adiva-26745

- Olsson Dahlquist, L. (2019). Folkbildning för delaktighet: en studie om bibliotekets demokratiska uppdrag i en digital samtid. Lunds universitet. https://lup.lub.lu.se/record/d0f8de0c-7232-4de0-a1b3-d69b52300a4e

- Pilerot, O. (2019). Arbete i regional biblioteksverksamhet. Region Uppsala. https://web.archive.org/web/20220516073010/https://regionuppsala.se/globalassets/kulturutveckling/biblioteksutveckling/ola_pilerot_regional_biblioteksverksamhet_slutversion.pdf

- Rasmussen, C.H. and Jochumsen, H. (2003), Strategies for public libraries in the 21st century. The International Journal of Cultural Policy, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 83-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028663032000089840

- Real, B., Bertot, J. C., & Jaeger, P. T. (2014). Rural public libraries and digital inclusion: Issues and challenges. Information Technology and Libraries, 33(1), 6–24. https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v33i1.5141

- Schultz Nybacka, P. (2013). Att hantera den dynamiska kontrasten mellan tradition och förnyelse : en studie av Projekt Kompetensen inom Regionbibliotek Stockholm. Regionbibliotek Stockholm.

- SFS 213:801. (2013). Swedish Library Act.

- Suchman, M.C. (1995). Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571-610. https://doi.org/10.2307/258788

- Thornton, Patricia H. (2004). Markets from culture. Institutional logics and organizational decisions in higher education publishing. Stanford University Press.

- Thornton, Patricia H. & Ocasio, William (1999). Institutional Logics and the Historical Contingency of Power in Organizations: Executive Succession in Higher Education Publishing 1958-1990. American Journal of Sociology. Vol. 105:3, p. 801-43. https://doi.org/10.1086/210361

- Waller, V. (2008). Legitimacy for large public libraries in the digital age. Library Review, 57(5), 372-385. https://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00242530810875159