Exploring information behaviour and meaningful experience amongst hikers on the West Highland Way

Keith Munro, Perla Innocenti and Mark Dunlop

Introduction. This paper discusses the information behaviour of hikers on the West Highland Way in Scotland by exploring meaningful experiences described by fifty participants walking the route.

Method. Using an ethnographic approach, participants were interviewed in the field at sites on the West Highland Way using semi-structured questions.

Analysis. Qualitative results are discussed and analysed using inductive thematic analysis and links to literature are established.

Results. Two types of meaningful experience were found in the interview data: connections with nature and social connections. Profound natural connections were found to feature embodied information from sensory interaction with the environment, resulting in a contemplative mindset and offering well-being benefits. Social connections with family, friends and fellow walkers were also described as meaningful, situating the activity as a ‘higher thing’ and demonstrating further well-being benefits.

Conclusions. This initial study indicates that natural and social connections are key to meaningful experience in walking the West Highland Way. A broader information behaviour study based on this work will further explore the use of embodied information, contemplation in information science, serious leisure as a ‘higher thing’, and well-being benefits.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irisic2204

Introduction

This paper discusses how hikers encounter meaningful experiences on their journey. The study is part of wider ethnographic research investigating the information behaviour of hikers on the West Highland Way in Scotland, UK. An initial data gathering exercise was conducted onsite, where fifty participants engaged in short interviews for insights into their experience of walking this long-distance route.

The West Highland Way is located in Scotland and is 96 miles long, running from Milngavie, on the outskirts of Glasgow, to Fort William in the Highlands (Loram and Newton, 2019). Launched in 1980, it is the country’s most popular long-distance walking route, with over 40,000 people completing it annually (West Highland Way, 2021). Many walkers are fulfilling a long-standing ambition (Hanley, 2020) and it has been described as akin to a pilgrimage in guides to walking the route (Loram and Newton, 2019).

The route has featured in prior academic research, including fields such as tourism management (Den Breejen, 2007), sports medicine (Ellis, et al., 2009) , natural history (McWaters and Murphy, 2016) and geography (Dickinson, 1982). However, it has not been previously addressed in information science studies. This work therefore aims to fill a gap in published knowledge in the field, specifically by exploring how participants‘ information behaviour informs meaningful experience and how this relates to the concept of higher things, to establish links to the interpretation and use of embodied information in other activities, as well as demonstrating possible well-being benefits associated with the activity. In doing so, a better understanding of the information behaviour of hikers can be gained, assisting in the delivery of useful information and information systems for the activity.

Literature review

This research is informed by the concept of higher things, the study of aspects of life that can be considered meaningful in a positive manner (Kari and Hartel, 2007) , The call to consider higher things posits that many information behaviour studies focus on areas that can be considered negative, serious life events such as illness or everyday activities like work. Therefore, to have a more complete understanding of information behaviour, research also needs to focus on that which can be considered pleasurable or profound. Activities identified as higher things include hobbies, leisure and relaxation, while profound experiences include human development, meaning of life and positive thinking. They are often serious leisure pursuits (Stebbins, 1982), of which hiking is considered as one (Davidson and Stebbins, 2011). Examples of walking being a higher thing can be observed in studies related to walking pilgrimage on the Camino de Santiago and St. Olav’s Way in Norway, a sense of mindfulness and being present in the moment, which is antithetical to everyday life, as well as a sense of spirituality, even amongst participants who were not religious (Jørgensen, et al., 2020; Slavin, 2003).

A relevant but parallel field is that of contemplative studies, research concerning the primary factors that influence human contemplative experience and the different means through which contemplative practices are conducted, generating meaningful understanding of them (Roth, 2014). Contemplative practice is commonplace in modern society and can be observed in popular activities like yoga, mindfulness applications or meditation. Contemplative studies are an interdisciplinary field, drawing on science, humanities and the arts (Roth, 2006) and there are calls for information science to focus studies towards this (Latham, et al., 2020), to understand the information behaviour that feeds into such activities. There are links between walking and contemplation studies, with walking meditation being identified as a key contemplative practice (Duerr, 2011). This ties in with walking in the natural environment of Scotland being described as a form of meditation (Shepherd, 2008) and in walking art practice, which involves ‘conscious walking’ and ‘meaningful reflection’ (Pujol, 2018, p. 3). Walking as meditation is also observed on walking pilgrimage routes (Jørgensen, et al., 2020; Slavin, 2003).

Another key concept informing this work is embodied information, an area in which further research is needed, particularly in relation to physical activities (Cox, et al., 2017). Some studies have demonstrated relevant findings in a similar pursuit, for example long distance hikers (Hyatt, 2020) and runners (Gorichanaz, 2015) assess sensory information and this affects their state of mind (Gorichanaz, 2015). Runners also use visual information from their environment to assess the going, internal sensory information from muscles and breathing, external sensory information such as wind on the skin, as well as aural and olfactory sensations to inform whether the activity is pleasurable or painful (Hockey, 2004, 2006, 2013; Hockey and Allen-Collinson, 2013). Walking pilgrims use sensory information to aid meditative states and to create an internal map of the route (Slavin, 2003), as well as immersing themselves in the sensory feedback of the natural environment (Jørgensen, et al., 2020).

Method

An initial data gathering exercise was conducted in the field on the West Highland Way in October 2021 using an ethnographic approach, a methodology suggested in information behaviour studies to better explore embodied information (Cox, et al., 2017) . This work was conducted as part of an investigation into: (1) how walkers information behaviour informs well-being benefits, (2) how embodied information influences walkers’ meaningful experiences on the route and (3) how walkers digitally capture meaningful experiences. Participants were approached at different locations on the route: Tyndrum, Bridge of Orchy, Glencoe (Figure 1) and Kinclochleven. The study was conducted under institutional ethical approval and within COVID -19 restrictions and guidelines.

Participants were asked to consent to take part in a short audio recorded interview, beginning with demographic questions regarding age, gender, whether they had walked the route before and whether they had walked other long-distance walking routes, followed by three semi-structured interview questions:

- What drew you to walk the West Highland Way?

- Did you have a meaningful experience yesterday?

- How have you recorded your journey so far?

These were based on research questions related to well-being benefits and how embodied information and digitally recording the hiking journey informed meaningful experience and memories. Participants were then invited to an online interview at a later date where more data could be gathered. This paper incorporates data from all the questions but primarily focusses on findings related to the second interview question regarding meaningful experience, positioning them within existing work on this topic in information science (Gorichanaz, 2019).

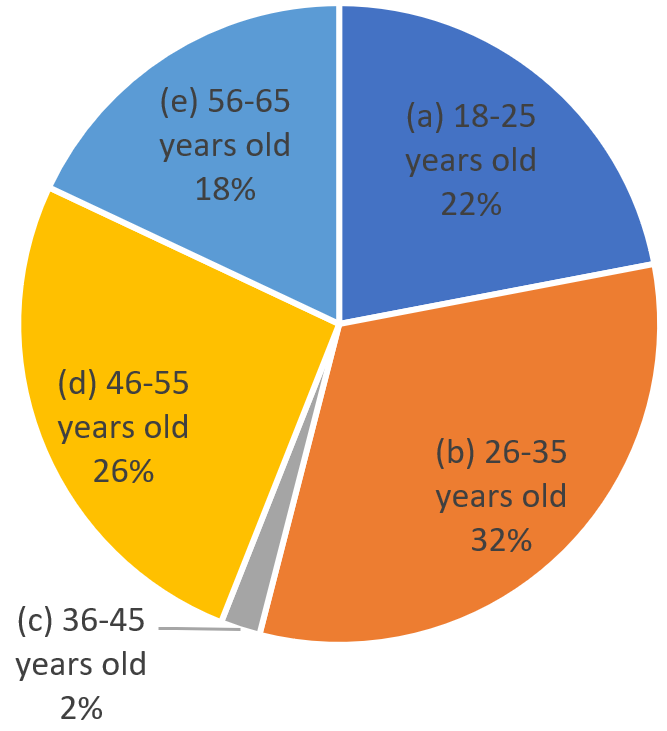

All participants were over 18 and had their identities anonymised in sequential order of being interviewed (P1-P50). All participants were walking the full length of the route, either at once or in stages over a longer period of time, those who were out for a day hike or walking locally were excluded. Participants were a mixture of individuals, dyads and groups, if in a dyad or group all participants were interviewed at the same time. Fifty participants were interviewed, and their age groups are indicated in Figure 2. Gender was represented as 54% of participants male and 46% female. 86% of participants had not walked the West Highland Way before, with only 14% having previously completed the route.

Further to this, 72% of participants had done some other form of long-distance walking with commonly listed routes including Camino de Santiago, Offa’s Dyke and the Great Glen Way, suggesting that this activity represented an extension of a serious leisure pursuit, while 28% had not done any other kind of long-distance route, indicative of a possible entry point to the activity becoming more serious.

Audio recorded interviews were transcribed and then subjected to thematic analysis, at first deductively, then inductively (Braun and Clarke, 2019). Initial analysis coded whether a meaningful experience had been stated or not in response to the second interview question, with annotations made of the characteristics of experience. After this, coding was applied to all interview data according to the key concepts set out in the literature review: higher things, serious leisure, contemplation studies and embodied information. Again, annotations for the type or characteristic of data related to these concepts were made, for example natural beauty, mindfulness and family connection. From the collation of data associated with these deductive themes, two emergent themes emerged inductively related to meaningful experience, that of natural connections and social connections.

Findings and discussion

From studying this initial data, 46 participants said they had had a meaningful experience the day before and four said they had not. From this there were two emergent themes described as meaningful experiences: connections to nature and social connections. These themes are then discussed in relation to links to relevant literature.

Connections to nature

The most common form of natural connection was with the weather. Perhaps obviously for some good weather was linked to a memorable experience, offering rewarding views and good walking conditions. However bad weather was also mentioned in relation to meaningful experience, of character building, a sense of accomplishment, meeting a challenge and enjoyment.

Other connections were described in relation to the natural environment of the route, of being ‘at one with nature’ (P11) or ‘very much in touch with nature’ (P19). The scenery was often mentioned as being memorable, ‘for me, it was the beauty of the landscape unfolding’ (P34). Links to history in the landscape and memorable connections with wildlife were also discussed. Beyond the visual, participants also described the sounds of the landscape and the wildlife as being memorable, as well as the sense of quiet in remote locations. Finally, there was discussion of how this connection with nature fostered a positive contemplative mindset while walking, of it being like a form of ‘meditation’ (P20), while others described it as ‘spiritual’ (P25 and P39).

These meaningful nature connections link with concepts from the literature review. The landscape’s sensory information offers a chance for contemplation, an area posited as a rich source of findings (Latham, et al., 2020). Participants described walking in this environment as a form of meditation, as seen in walking in contemplation studies (Duerr, 2011), personal reflections on the natural environment of the Scottish Highlands (Shepherd, 2008), walking art practice involving meaningful refection (Pujol, 2018) and walking pilgrimage routes (Jørgensen, et al., 2020; Slavin, 2003) . Linking with the concept of higher things (Kari and Hartel, 2007), participants talked of being at one with nature and this experience feeling spiritual.

There is also demonstration of well-being benefits by considering the New Economics Foundation (NEF) five ways to well-being: connect, be active, take notice, keep learning and give (New Economics Foundation, 2008). The NEF is a UK based independent think-tank with the aim of promoting sustainable and well-being centred economic policies and the five ways have been used in studies such as environmental decision making (Fish, 2011) and green exercise (Barton, et al., 2016). The most apparent link is to the be active stage due to the level of physical activity involved in walking the route. There are also emergent links to the connect and take notice stages, with observing and feeling connected to nature frequently stated as meaningful.

Further to this there are links to embodied information in relevant studies, the walkers’ observation and interpretation of sensory information from the natural environment fed into meaningful experiences, similar to the effect that weather, conditions underfoot and assessment of physical condition had on runners and long distance hikers (Gorichanaz, 2015; Hockey, 2004, 2006, 2013; Hockey and Allen-Collinson, 2013; Hyatt, et al., 2020). Immersion in the natural environment is also apparent in descriptions of embodied experiences on walking pilgrimage (Jørgensen, et al., 2020). Indeed, embodied information, specifically how the participants’ bodies experienced the environment, can be seen to inform all of these natural connections and is key to contemplation and associated well-being benefits, as well as positioning them as a ‘higher thing’.

Social connections

Social connections between family, friends and fellow walkers were also associated with meaningful experiences. A memorable connection between friends walking the route together was being able to discuss and process problems in their lives, described as ‘therapeutic’ (P11), while a married couple (P35 and P36), where one of them suffered from chronic illness, described their partner’s support while walking as very meaningful.

Meaningful connections between fellow walkers were also described, hinting at being on the ‘same journey’ (P42) and having a common ground from which to share experiences. Another described how this shared journey allowed for connections to deepen and become more meaningful over the course of the route (P18). One participant (P32) described a social interaction that had resonated with them emotionally, a fellow walker sharing that they were walking the route to scatter the ashes of a friend who had previously walked it with them. Beyond social connections on location, meaningful experiences in sharing the journey with family and friends at home through social media and other digital communication platforms were also discussed, particularly amongst participants who were raising money for the care needs of a relative (P35 and P36).

Interconnections fostered along the route with family, friends and fellow walkers can be considered a ‘higher thing’(Kari and Hartel, 2007). Participants related meaningful experiences to do with the care of partners, the sharing and processing of serious life problems amongst friends and emotionally resonant exchanges with fellow travellers, indicating the route to be a site where profound experiences can occur. As with natural connections, these social connections offer clear well-being benefits that can be linked to the NEF five ways to well-being (New Economics Foundation, 2008), with clear links to the connect stage in the form of meaningful social interactions, as seen on walking pilgrimage (Jørgensen, et al., 2020; Slavin, 2003), but also the give stage through offering support to those they were walking with and by engaging in fundraising, observed in long-distance walking in Wales (Dix, 2020).

Conclusion and next steps

This study has explored the previously unconsidered information behaviour of walkers on the West Highland Way. From initial data gathering and analysis there is demonstration of participants having meaningful experiences along the route in the form of natural and social connections. Central to connections to nature was the interpretation of embodied information, specifically the sensory interaction with the environment, which link with literature around embodied information, higher things, contemplation studies, and well-being. Social connections involving family, friends and fellow walkers were also commonly described as meaningful, placing them as a higher thing and demonstrating well-being benefits. This furthers understanding of this activity within these concepts in information behaviour studies. Knowledge from this study can assist with the provision of useful information and design of information systems for associated activities.

Analysis of this initial data gathering exercise is being used to design further data collection. This next phase of the study will aim to gather more detailed data in: (1) how participants’ information behaviour can be classified using Hektor’s information behaviour model (Hartel, et al., 2016; Hektor, 2001), (2) further understanding the use and interpretation of embodied information in the activity and (3) further exploring links to the field of contemplative studies and whether any associated positive mental well-being benefits from walking the route. Further research looking at the emergent themes of this study in relation to other hiking routes and similar physical activities would be welcome.

Acknowledgements

This pilot study is part of a research project funded by the University of Strathclyde. We would like to thank the participants for walking along. We are grateful to Ian Ruthven (University of Strathclyde) and Ed Hyatt (University of Northumbria) for their inputs to this study.

About the authors

Keith Munro is a Ph.D. candidate in the department of Computer and Information Science at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK, and member of the Strathclyde iSchool and Digital Health and Wellness research groups. His research focuses on the information behaviour of walkers on the West Highland Way. He can be contacted at keith.munro@strath.ac.uk

Perla Innocenti is a Senior Lecturer in Information Sciences in the department of Computer and Information Science at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK, and member of the Strathclyde iSchool and Digital Health and Wellness research groups. Her research is in the interdisciplinary field of cultural heritage informatics; Perla‘s work is currently focusing on information practices in walking routes, from walking pilgrimages to hiking routes.

Mark Dunlop is a Senior Lecturer in Computer Science, at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK, and member of the Strathclyde iSchool and Digital Health and Wellness research groups. His research focuses on Human Computer Interaction, mobile HCI, and usability evaluation.

References

- Barton, J., Bragg, R., Wood, C., & Pretty, J. (2016). Green exercise: Linking nature, health and well-being. Routledge.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589-597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Cox, A. M., Griffin, B., & Hartel, J. (2017). What everybody knows: embodied information in serious leisure. Journal of Documentation, 73(3), 386-406. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JD-06-2016-0073

- Davidson, L., & Stebbins, R. (2011). Serious leisure and nature: Sustainable consumption in the outdoors. Springer.

- Den Breejen, L. (2007). The experiences of long distance walking: A case study of the West Highland Way in Scotland. Tourism management, 28(6), 1417-1427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.12.004

- Dickinson, G. (1982). An Assessment of Pathway Damage and Management: The West Highland Way. Department of Geography, University of Glasgow.

- Dix, A. (2020). The Walk Exploring the Technical and Social Margins. In HCI Outdoors: Theory, Design, Methods and Applications (pp. 19-50). Springer.

- Duerr, M. (2011). Assessing the state of contemplative practices in the US. Contemplative nation: how ancient practices are changing the way we live, 9-34.

- Ellis, C., Cuthill, J., Hew-Butler, T., George, S. M., & Rosner, M. H. (2009). Exercise-associated hyponatremia with rhabdomyolysis during endurance exercise. The Physician and sportsmedicine,37(1), 126-132. https://doi.org/10.3810/PSM.2009.04.1693

- Fish, R. D. (2011). Environmental decision making and an ecosystems approach: Some challenges from the perspective of social science. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment, 35(5), 671–680. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133311420941

- Gorichanaz, T. (2015). Information on the run: experiencing information during an ultramarathon. Information Research, 20(4), paper 697. http://InformationR.net/ir/20-4/paper697.html (Internet Archive)

- Gorichanaz, T. (2019). Information experience in personally meaningful activities. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 70(12), 1302-1310 https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24142

- Hanley, M. W. (2020). West Highland Way: Off the beaten path, hidden gems, local knowledge, untold stories, myths-legends-folklore, ultimate journal. Independently published.

- Hartel, J., Cox, A., & Griffin, B. (2016). Information activity in serious leisure. Information research, 21(4). http://InformationR.net/ir/21-4/paper728.html (Internet Archive)

- Hektor, A. (2001). What's the Use?: Internet and information behavior in everyday life (Vol. 240). Anders Hektor.

- Hockey, J. (2004). Knowing the route: Distance runners’ mundane knowledge. Sociology of Sport Online, 7(1), 1-10.

- Hockey, J. (2006). Sensing the run: The senses and distance running. The Senses and Society, 1(2), 183-201. https://doi.org/10.2752/174589206778055565

- Hockey, J. (2013). Knowing the ‘going’: The sensory evaluation of distance running. Qualitative research in sport, exercise and health, 5(1), 127-141.https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2012.693531

- Hockey, J., & Allen-Collinson, J. (2013). Distance running as play/work: training-together as a joint accomplishment. Ethnomethodology at play, 211-226. https://figshare.com/articles/journal_contribution/Distance_Running_as_Play_Work_Training_together_as_a_Joint _Accomplishment_in_P_Tolmie_M_Rouncefield_eds_Ethnomethodology_at_Play_London_Ashgate_pp_211_226_/769284 (Internet Archive)

- Hyatt, E., Harvey, M., Pointon, M., & Innocenti, P. (2020). Whither Wilderness? An investigation of technology use by long-distance backpackers. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24437

- Jørgensen, N. N., Eade, J., Ekeland, T.-J., & Lorentzen, C. (2020). The Processes, Effects and Therapeutics of Pilgrimage Walking the St. Olav Way. The international journal of religious tourism and pilgrimage, 8(1), 33-50. https://doi.org/10.21427/v0cc-7135

- Kari, J., & Hartel, J. (2007). Information and higher things in life: Addressing the pleasurable and the profound in information science. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(8), 1131-1147.https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20585

- Latham, K. F., Hartel, J., & Gorichanaz, T. (2020). Information and contemplation: A call for reflection and action. Journal of Documentation.

- Loram, C., & Newton, J. (2019). West Highland Way: Glasgow to Fort William: 53 large-scale maps & guides to 26 towns and villages, planning - places to stay - places to eat.

- McWaters, S., & Murphy, K. (2016). Biological assessment of recreation-associated impacts on the water quality of streams crossing the West Highland Way, Scotland. Glasgow Naturalist, 26(2), 21-29. https://www.glasgownaturalhistory.org.uk/gn26_2/mcwaters_murphy_whw.pdf (Internet Archive)

- New Economics Foundation. (2008). Five ways to mental wellbeing. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/five-ways-to-mental-wellbeing (Internet Archive)

- Pujol, E. (2018). Walking art practice: Reflections on socially engaged paths. Triarchy Press.

- Roth, H. D. (2006). Contemplative studies: Prospects for a new field. Teachers College Record, 108(9), 1787-1815.

- Roth, H. D. (2014). A pedagogy for the new field of contemplative studies. Contemplative approaches to learning and inquiry across disciplines, 97-118

- Shepherd, N. (2008). The living mountain: a celebration of the Cairngorm mountains of Scotland. Canongate Books.

- Slavin, S. (2003). Walking as spiritual practice: the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. Body & Society, 9(3), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1357034X030093001

- Stebbins, R. A. (1982). Serious leisure: A conceptual statement. Pacific sociological review, 25(2), 251-272. https://doi.org/10.2307%2F1388726

- West Highland Way. (2021). 40th Anniversary - West Highland Way. https://www.westhighlandway.org/40th-anniversary/ (Internet Archive)