Information needs of young adults with cancer in Germany

Paulina Bressel

Introduction. In Germany, approximately 500.000 people are newly diagnosed with cancer every year, of which only 3,3% are young adults between 18 and 39 years of age. Despite age-specific characteristics in terms of care and treatment, they receive little attention in the health infrastructure. The aim of this study is therefore to investigate information needs of young adults with cancer in Germany.

Method. Semi-structured guided online interviews were conducted with 14 young adults at the end of their treatment or in aftercare.

Analysis. The qualitative analysis was carried out inductively, using thematic analysis. In addition, the identified topics were analysed using the concept of the cancer patient journey.

Results. Ten themes were identified which are divided into information, service and care needs. While needs of the three identified medical themes are, for the most part, adequately answered, this does not apply to needs of the remaining seven themes.

Conclusions. The findings clearly demonstrate that the German health infrastructure still holds a lot of potential for improvement regarding answering information, service and care needs for young adults with cancer.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irisic2212

Introduction

Cancer is a global, potentially fatal disease that affects people of all ages. In Germany alone, 500.000 people are newly diagnosed with cancer every year (Robert Koch Institut, 2019). Only 16.500 of these diagnoses affect young adults between 18 and 39 years of age (German Foundation of young adults with cancer). As young adults with cancer therefore only represent 3,3% of all new cases in Germany each year, they are often not treated as a separate target group in the German health infrastructure.

Due to their age, young cancer patients are in a phase of transition, which includes social, mental and physical aspects (Zebrack, 2009; Keegan, et al., 2012; Lea, et al., 2018) and results in age-specific characteristics in cancer care and treatment (Zebrack, 2007; Lea, et al., 2018). If these special needs are not addressed due to lack of focus and adaption of the health infrastructure, young adults with cancer will have difficulties coping with the disease and its impact on their lives (Fernandez and Barr, 2006; Keegan, et al., 2012).

Countries like Great Britain, the United States of America, Canada and Australia researched needs of young adults with cancer since the early 2000s until now, resulting in age-specific treatment programs and centres, that have been proven to support individuals in their medical and psychosocial management of the disease (e.g. Zebrack, 2008; Bellizzi, et al. 2012; McCarthy, et al., 2018; Lea, et al., 2020). In Europe and especially in Germany, there is a lack of focused research for this target group (Stark, et al., 2016), which leads to the assumption that health infrastructures and services have not yet been sufficiently adapted to young adults. Due to different health care systems and medical approaches in different countries, a separate analysis for Germany seems necessary in order to clarify the current status of those affected within the German health care infrastructure and to reveal subjective needs for improvement. This is the first study to examine information needs of young adults with cancer in Germany and it is also the first study on young adults to use the concept of cancer patient journeys to study information needs.

Since existing international studies have been conducted mainly in the field of medicine, this study aims to analyse information needs of young adults with cancer from an information science perspective. The study was conducted using a qualitative research design consisting of 14 semi-structured guided interviews with young cancer patients who were at the end of their treatment or in aftercare. Shortly after the study was conducted, the full study was published in German on the institutional repository of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (Bressel, 2021).

Background

Research on health information behaviour is conducted both in information science and by different disciplines within health sciences, although particular reference is made to information science models (Petersen et al., 2021). In context of cancer research, especially information needs and information seeking behaviour was studied by information researchers (e.g.. Attfield, et al., 2006; Lambert, et al., 2009; Johnson and Case, 2012). However, a focus on the target group of young adults with cancer was not made so far. To best knowledge, this paper is the first study addressing young adults with cancer in information science.

Yound adults with cancer

In the context of cancer research, different age definitions for the target group of young adults have been chosen in the past. They are often analysed together with adolescents due to similar life experiences and perceptions. In this context classifications of 13-24 years (Abrol, et al., 2017; Lea, et al., 2018), 15-24 years (Stark, et al., 2015; Ahmad, et al., 2016), 15-25 years (McCarthy, et al., 2017), 15-29 years (Zebrack, 2008; Ferrari, et al., 2010) or 15-39 years (Bellizzi, et al., 2012; Aggarwal, et al., 2020) have been used. However, even without the involvement of adolescents, various approaches exist to describe young adults. For example, Abrol, et al. (2017) define them as individuals aged 19-24, Hauken (2014) and Kaal, et al. (2018) use the definition of 18-35 years, and Lea, et al. (2210) narrow the target group to individuals aged 19-26. This study includes individuals between the age of 18 to 39. Both cancer studies (Barnett, et al., 2016; Domínguez, et al.; 2016, Leuteritz, et al., 2018) and public or organisational websites (US National Cancer Institute, German Foundation for young adults with cancer) refer to this definition.

Receiving a cancer diagnosis as a young adult influences the developing sense of self of those affected, as they are in an emotional, physical and social transition phase due to their age (Zebrack, 2007; Bellizzi, et al., 2012; Ahmad, 2016; Barnett, et al., 2016). This affects the existential areas of relationships, education or work, children, as well as finances and future plans, and can lead to a partial loss or rediscovery of one’s identity (Belizzi, et al., 2012; Keegan, et al., 2012; Barnett, et al., 2016).

Furthermore, the disease leads to side, late and long-term effects, which have an additional negative impact (Lie, et al., 2018) and cause alienation from peers who do not have these experiences (Abrol, et al., 2017). While in Germany individuals between 0 and 17 years of age are subdivided according to age groups (newborn, infant, toddler, child, adolescent), a subdivision of this kind is omitted after reaching the age of majority (Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung, 2021). This leads to young adults often not being treated together with peers, what impairs the exchange of information (Zebrack, 2017). As a result, existing information grounds like waiting rooms provide not as useful information for young adults, as for older individuals (Attfield, et al., 2006). If they want more information, they are therefore dependent on actively seeking in other sources, such as online websites (Lea, et al., 2018; Lea, et al., 2019; Jiang and Liu, 2020), on social media (Valle, et al., 2013; Domínguez, et al., 2016; Perales, et al., 2016; Kaal, et al., 2018) or through social sources such as families and friends.

Information needs of young adults with cancer

Information need is the existence (Dervin, 1983) and recognition of a knowledge gap (Belkin, 1980) which depends on the personal, subjective context of the individual (Wilson, 1981), and which closing is done by seeking information after the gap has been recognised (Dervin, 1983).

As previous studies have shown, in the context of cancer research, a distinction between different needs of cancer patients must be made (Attfield, et al., 2006). According to Zebrack, et al. (2010), Barnett, et al. (2016) and Lea, et al. (2020), cancer patients have information needs as well as service and care or support needs that are not yet fully being answered and relate to different areas of life.

By providing needed information and support, psychological well-being, understanding of medical information, self-determined co-decision-making for therapies and the reduction of anxiety and stress are supported (Adams, et al., 2009). Unmet needs on the other hand can lead to increased anxiety, the feeling of loss of control and poorer outcomes (DeRouen, et al. 2015; McCarthy, et al., 2018). In particular, the provision of information and support for adoption, age-specific rehabilitation, therapy options for sexuality and intimacy and the use of alcohol and drugs (Zebrack, 2008), as well as long-term effects and the possibility of relapse (McCarthy, et al., 2018) were identified as unmet needs. However, as Lambert, et al. (2009) summarize, cancer patients deal with information individually. While some patients have many information needs, which they want to satisfy by seeking all information accessible, others consciously avoid cancer related information to evade psychological stress and overload.

The cancer patient journey

Going through cancer is a subjective experience that includes different stages, like diagnosis, treatment(s) and aftercare. Based on the concept of patient journeys (Brailsford, et al., 2004), this process is called cancer patient journey (Halkett, et al., 2010; Nanton, et al., 2010; Germeni, et al., 2014; Tran, et al., 2018) or cancer timeline (Lea, et al., 2018).

In the past, this concept of patient journeys assisted in research about patient uncertainty when receiving information at different disease stages (Nanton, et al., 2010), the information seeking and avoidance behaviour of cancer patients (Germeni, et al., 2014) and unmet information needs (Halkett, et al., 2010; Tran, et al., 2018; Lea, et al., 2018). The advantage of this concept is the combination of the analysis of individual disease stages and the holistic consideration of all stages together. Moreover, the framework offers a clear structure for the analysis of different stages, their chronology and occurring needs, what is the rationale for its application within this study.

Method

Data collection and analysis

Subjective experiences of the target group were collected to describe information needs of young adults with cancer. For this purpose, a qualitative, inductive research approach was chosen. Fourteen semi-structured guided interviews were conducted with cancer patients aged 18-39, who were at the end of or after completion of treatments. Because of the covid-19 pandemic during the data collection from November to December 2020, all interviews except for two were conducted via Zoom or Skype, only the audio was recorded for the analysis. On average the interviews were 40 minutes long. All of them were conducted and fully transcribed in German. During reporting, quotes for the article were translated to English. The transcription, coding and analysis of the data was carried out with MAXQDA20. The data were subsequently analysed using thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke (2006). This qualitative approach is a substantial difference from the majority of current medical studies of young adults needs (DeRouen, et al., 2015; Shay, et al., 2017; McCarthy, et al., 2018; Tran, et al., 2018).

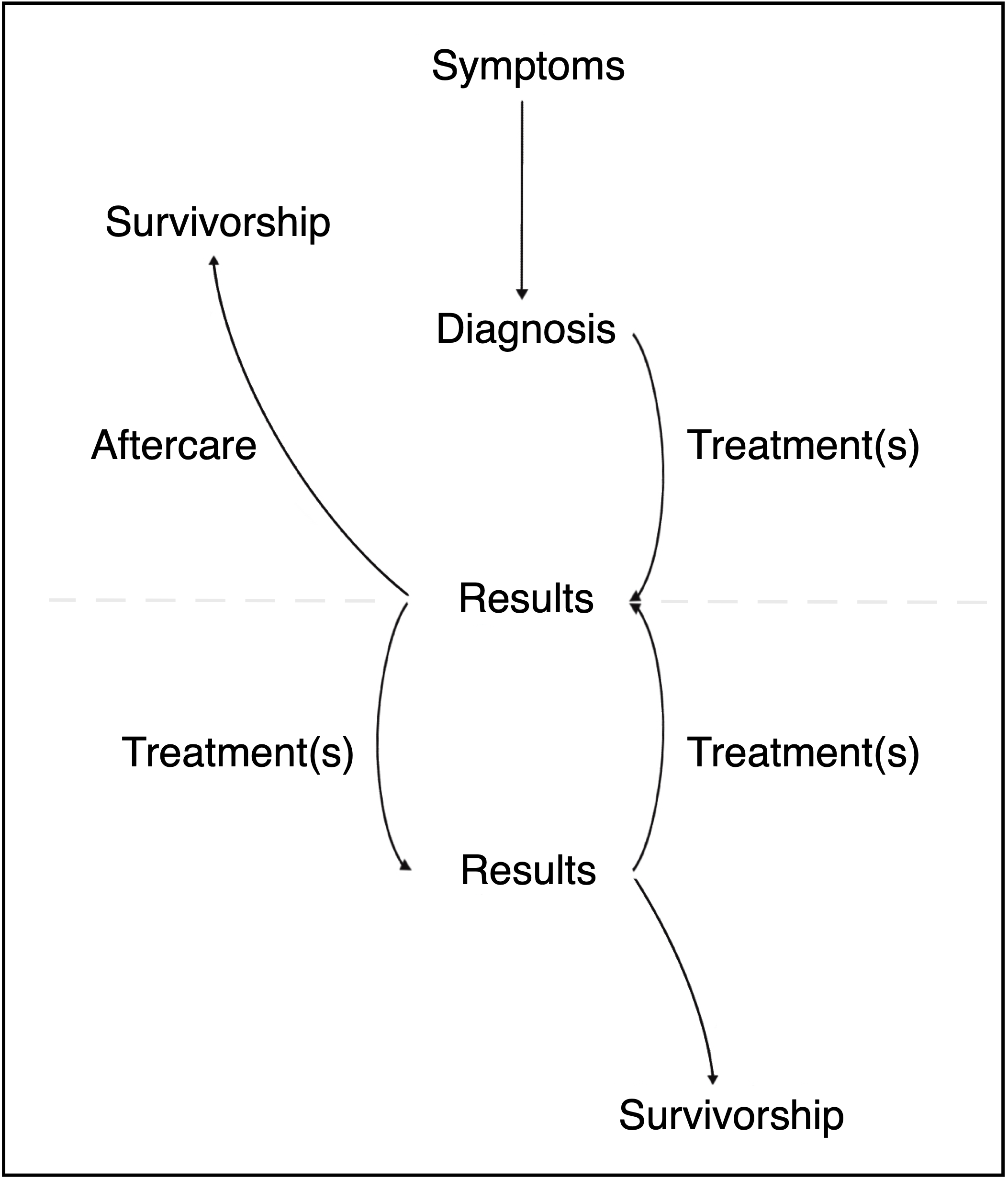

A cancer patient journey model was created based on a previous literature and video research by the author, which served to structure the interview guide, as well as further analyse and structure the results. The model of the cancer patient journey is presented in figure 1.

The model consists of two circles, which start by the recognition of symptoms. These symptoms are followed by a diagnosis, which marks the beginning of the actual cancer journey. After going through treatment(s), the decision follows about whether further treatments are necessary or whether aftercare can be initiated. From this turning point either the second circle begins or the patients start their recovery process, which eventually leads to cancer survivorship. Since cancer is a potentially fatal disease where death can occur at any stage of the journey, this aspect was left out of the model. However, it should be noted that this component can be added at any point.

The interview guide was structured based on the cancer patient model. The participants were asked about their experiences during each stage of the patient journey regarding questions and thoughts that occurred, as well as their information behaviour and most important requests for improvement.

Participant recruitment and sample

Fourteen participants were recruited using snowball sampling and with help of the German Foundation for Young Adults with Cancer, who disseminated the request through all their regional channels. In order to create a heterogeneous sample, the following aspects were considered during recruitment:

- Age during diagnosis (18 – 39)

- Type of cancer

- Place of residence/treatment

The final sample is presented in table 1 in the Appendix. Two of the participants had cancer that is incurable, one participant was pregnant during diagnosis.

Results

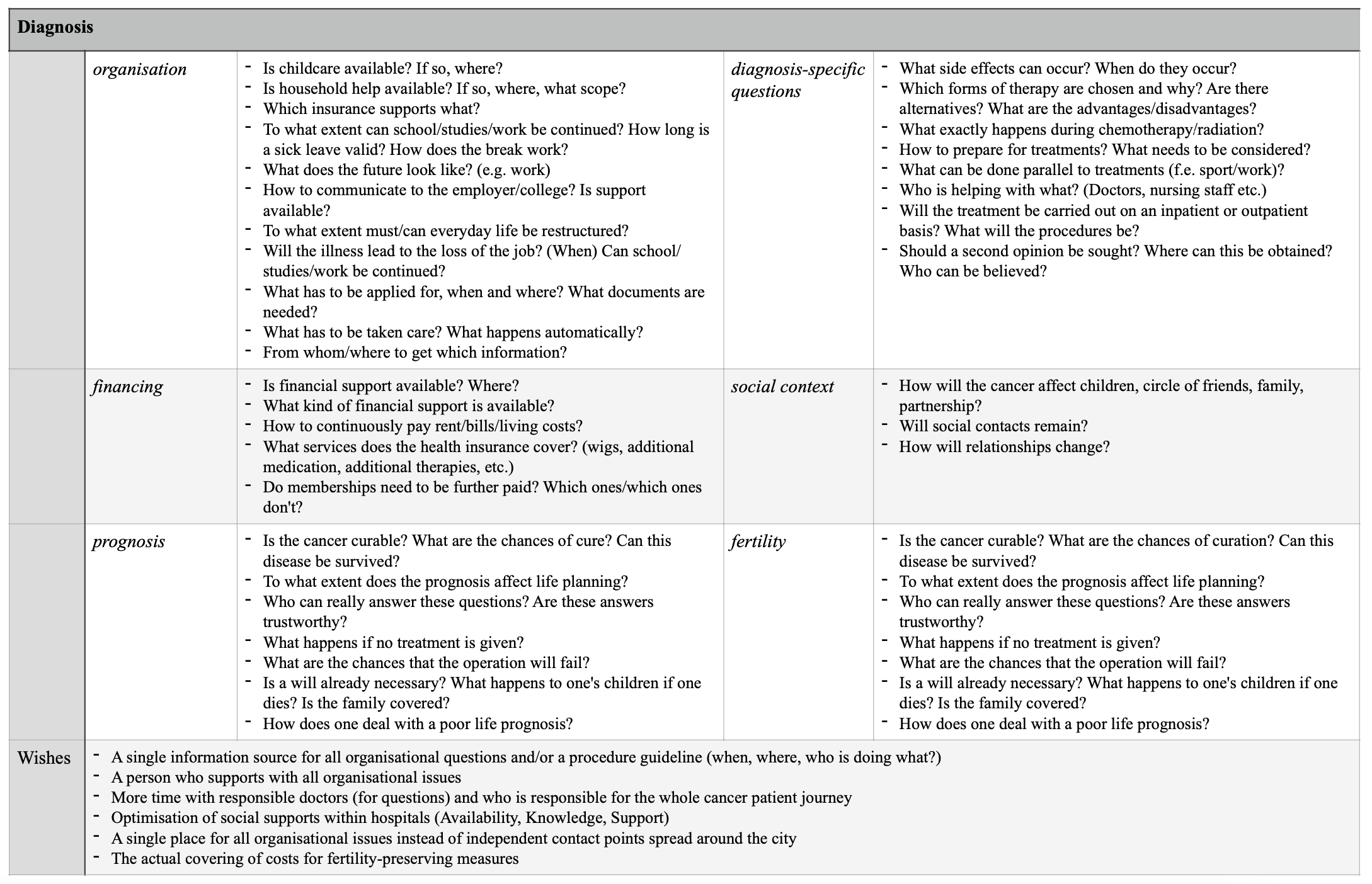

The data analysis revealed ten themes that reflect needs of young adults with cancer. They can be divided into the three main stages of the cancer patient journey: Diagnosis, Treatment(s), Aftercare. The identified themes are: organisation, finances, diagnosis-specific questions, prognosis, health practices, fertility, mental health, social context, rehabilitation and aftercare. The participants have experienced much pain in their life so that guaranteeing the safety of their identity is especially important for this study. Quotes are thus translated and participants names replaced by a letter without further traceable identification to the interviewees. The study received ethical approval.

I was just straight into battle mode. I knew immediately that it was not a question of whether I would make it, but how and when I would make it. (K)

Diagnosis

Diagnosis marks the first main stage of the cancer patient journey. In this stage participants mentioned six themes, which are explained below.

Organisation is the first theme, in which a distinction regarding the participants’ context must be made. Information needs regarding work or chosen educational paths and sick leaves (L), communicating the diagnosis to employers and colleagues (H, M), and the right time to give up on everyday life (H) were identified.

In addition, young parents are in a special situation. They have to take care of themselves and the disease, as well as continue to take care of their children. Receiving a cancer diagnosis therefore leads to information needs about the well-being of their own children, in addition to the organisational work involved (K, L). Unanswerable information needs result in anxiety regarding the future.

I was very worried about how my children would get through it. My older child was just about to start school and we had just moved to a new town. My biggest worry was: Will my children be psychologically damaged by this? How will my relationship stand it? How will I feel afterwards? Will I be able to work? Will I be able to work a lot, how will I be able to work? (L)

All participants mentioned that they felt left alone regarding organisational needs during this stage of the cancer patient journey, which led to additional stress and frustration (I, K). It is seen as problematic that there are many different points of contact for organisational needs and that, despite the difficult circumstances, cancer patients must personally take care of finding appropriate information carriers (E, H, K). The need for a combined source of information (G, K), a personal contact person (J) or a guideline (B, G, M) was identified.

And what I also missed at that moment was that you had to go through everything one by one. Every question individually. Support? Household help? What do I have to take into account with all the documents? What do I have to apply for? What don’t I? What is done automatically? What isn’t? A Disaster. (K)

The second theme is finances, which is a subtopic of organisation due to some overlaps.

I sat down with tax advisors to see what would happen now. Yes, as stupid as it sounds, we have just bought a house. I was on parental leave, right? It was just so much. We had moved into our new house and then this happened. And yes, it’s also an economic question. Seriously! The children are so small, no money, no sick leave or anything. (K)

For those with employment, income is lost due to sick leave and depending on the length of cancer illness and the employment relationship. This creates an information need regarding the payment of rent and living costs (F, H, I, N). In Germany, there are support services such as the hardship funds of the Deutsche Krebshilfe or the German Foundation for young adults with cancer (C), the Künstlersozialkasse for self-employed artists or disability insurances (I, D), but cancer patients often do not receive information about them. Thus, they must actively seek information for themselves. However, if they have no knowledge of these possibilities, they are unaware of their knowledge gap and do not initiate information seeking. This leads to a dependence on obtaining information randomly or serendipitously.

The third identified theme is about diagnosis-specific questions. Based on the interviews, those needs are relevant during the whole cancer patient journey, but emerge for the first time during the diagnosis stage. Receiving a cancer diagnosis is already the first information need of young adults. Because of their age, symptoms are sometimes not taken seriously by doctors, resulting in delayed treatments (B, C, D). Further, information needs arise about carrying out treatments and the duration of the whole process, as well as possible side effects (F, H). Similar information needs occur for the theme prognosis, which is explained later.

Closely related to diagnosis-related questions is the fifth theme, fertility.

Before chemotherapy and radiation started, I just wanted to know, I will be irradiated on the head, but what does that do to the rest of the body? Will I still be fertile afterwards? Can I still have a child? (E)

However, the majority said that fertility-related questions were answered during doctor’s consultation (A, G, H). The main problem is more a financial than an informational issue (H, N).

Information needs involving the social context, which is the sixth theme during this stage, are about relationship stability and how the situation will influence their children (H, I, M). Even though these needs occur especially in the first stage, they occur throughout the entire cancer patient journey.

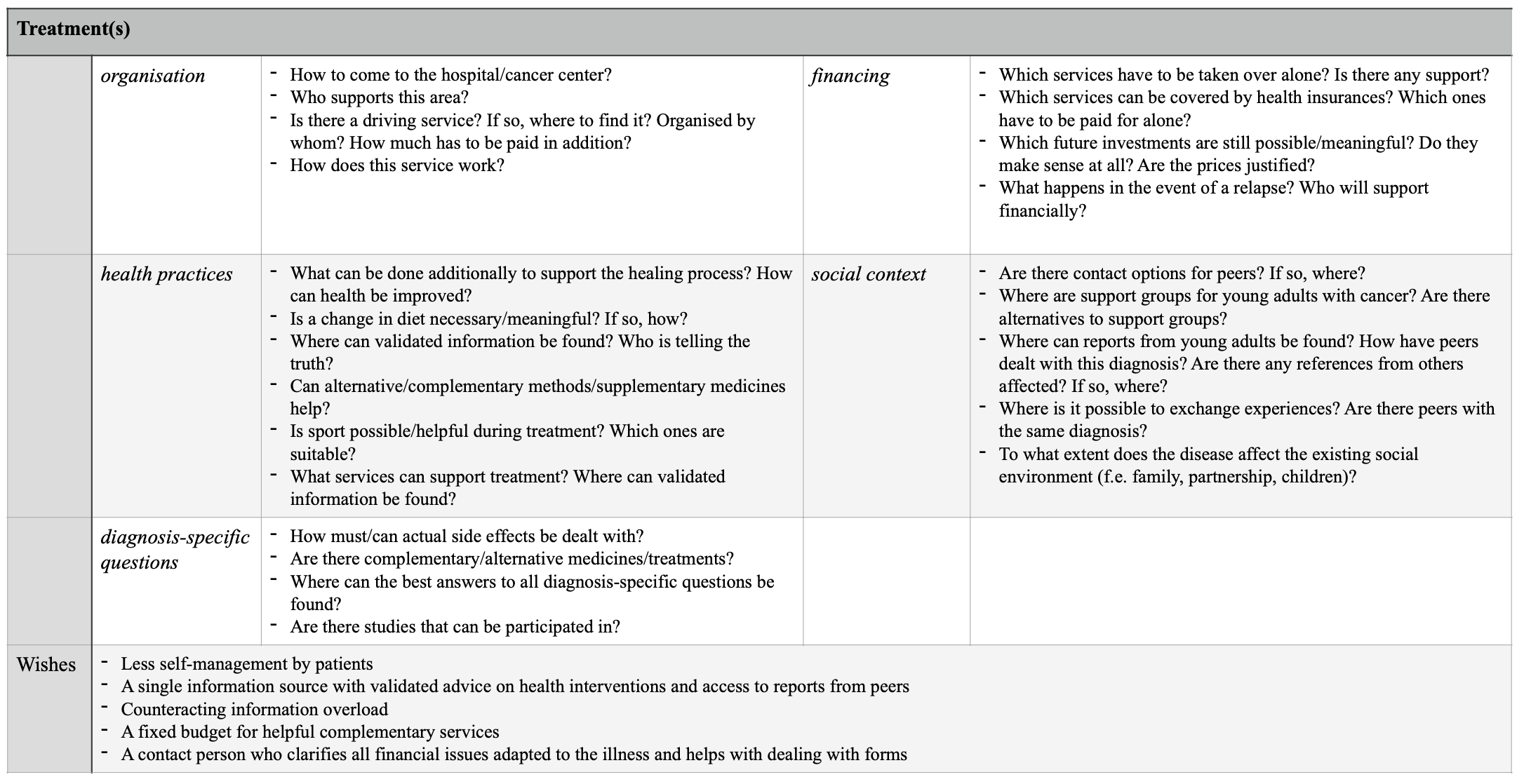

Treatment(s)

After going through diagnosis, cancer patients start their individual treatment(s) during the treatment(s) stage. Like the diagnosis stage, this stage contains five identified themes, which include needs of young cancer patients. The first theme for this stage is also organisation, but in contrast to the previous stage, it comprises only a few service and care needs, such as coordinating the way to the hospital or cancer center for each treatment, with the help of driving services (B, I). All young adults mentioned that too much self-responsibility was imposed on them. They must make appointments and arrange check-ups, and know their disease-status, their own body and similar issues, while dealing with side effects of treatment(s) (B, F, M).

With regard to finances, there is an urgent information need regarding the questions of where, how and which financial benefits can be claimed. This includes for example covering the costs of complementary treatments (E, H) and medicines (E), as well as services that improve side effects of treatment (D, K).

I always say, to go through cancer well, you really have to have money. You need to be able to afford to be diagnosed with cancer. (E)

Information needs of diagnosis-specific questions in this stage are mainly about alternative treatment options and dealing with side effects (E, F), or participation in research studies for new methods and drugs (B, D). An identified care need is more time with responsible doctors, in order to clarify all the individual questions (G, I).

What should have been done better? Well, I would say that it should somehow be made more detailed after the operation. Especially in combination with a doctor. Not that you are left alone like: “Here is the information. Read it and tell me your decision tomorrow.” but together with a doctor. (G)

The fourth theme is again the social context. Especially during treatment(s), thirteen participants would like to have contact and interaction opportunities with peers (A, B). However, as peers with the same illness are rarely treated in the same clinic, establishing contact is made more difficult (B, I). Moreover, the participants do not always know how to find peers on their own (A, G) or have the physical and mental strength to do so during treatment (A).

I wasn’t directed anywhere and I don’t know any support centres for young adults, but I didn’t do any research either because it didn’t even occur to me. (G)

The last theme during the stage of treatment is health practices. Needs of this theme appear for first time during treatment, after the first mental stress caused by a cancer diagnosis is left in the first stage. Engagement with health practices was found in all participants. Their own lifestyle is questioned and their awareness of health is increased. Identified information needs involve nutrition (B, F), sport (G, H), complementary medicine (E, F) and alternative treatments like meditation (C, N). These needs occur during this stage, as well as during aftercare.

Parallel with the treatments, health practices information needs are about the healthy handling and support of those treatments. In aftercare it is about the general support of one’s own health. The seeking process regarding this theme is influenced by the fact that various information sources contain contrary information. This leads to uncertainty (F, G, I) and fear of relapse (F), as it is not clear which source provides the correct information. In addition, the amount of information leads to information overload.

And what is always given to you is that you can do a lot as a patient to stay healthy yourself. Not through doctors, but rather through fellow patients, through the media, through alternative practitioners. So that somehow this after-cancer care movement, so everyone has then somehow read a study. […] But then you stand there as a cancer patient and want to do everything to stay healthy. And then there's just so much information about what you could or should pay attention to. And I found it all quite exhausting to deal with this information. (F)

No, it’s more the problem that you have two different opinions and then you don't know what's the truth. So which one is true? Or two different sources of information and they say something opposite or something contrary. […] You have to form your own opinion in the end, that's the problem. (G)

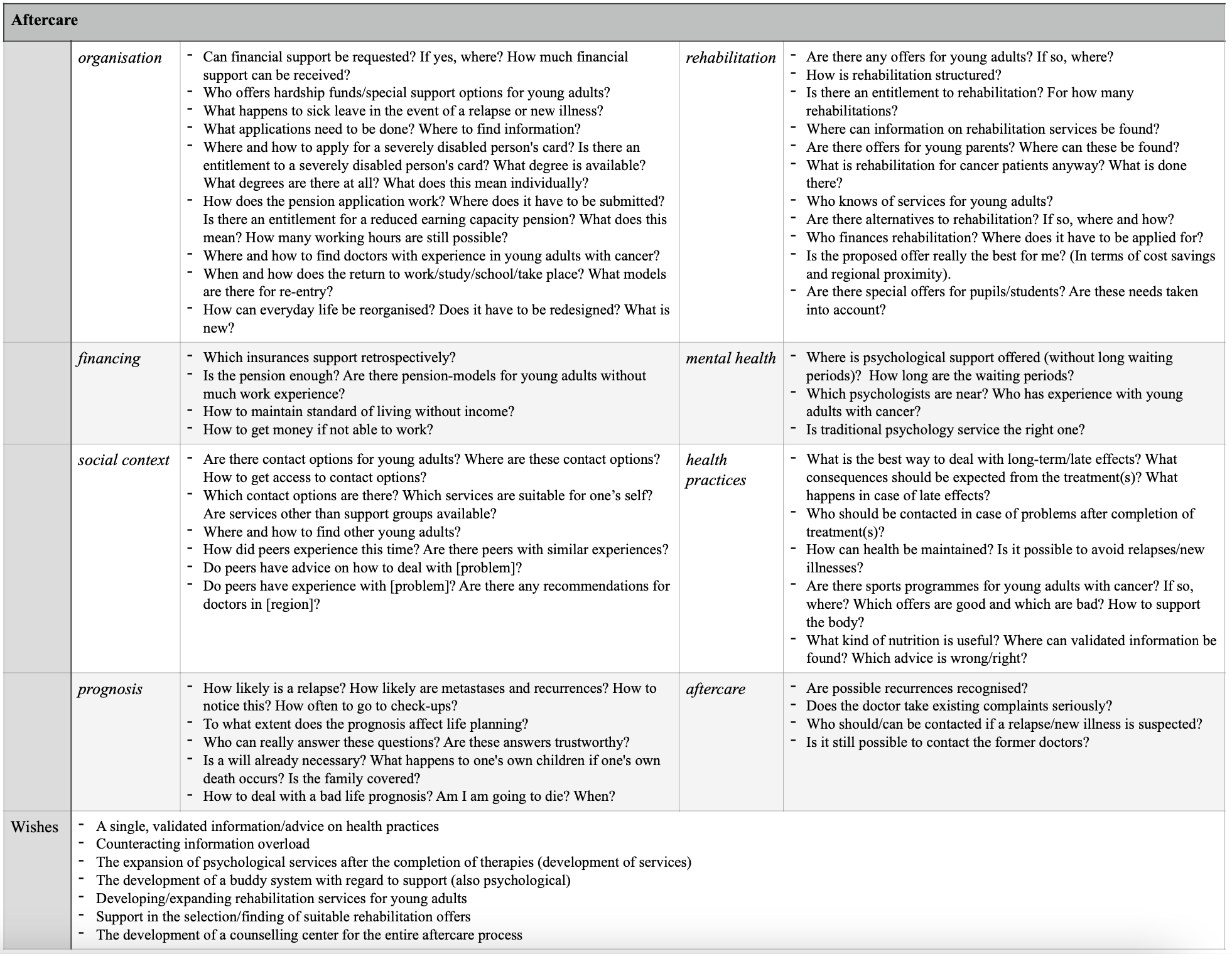

Aftercare

The last main stage of the cancer patient journey is aftercare, which combines eight identified themes.

The first identified theme of this stage is, as in the two previous stages, organisation. This theme, finances and social context, are evident throughout the entire cancer patient journey. Organisational information needs in aftercare are context-sensitive depending on the professional and educational background of the young adults. They need information about the right time to return to work or to their educational path (K) and the most suitable model for starting work again (B, H). They need to know how to apply for a disability card (C), for a reduced earning-capacity pension (E) and how to find qualified doctors, who have experience in working with young adults with cancer (M). Students and pupils have information needs about how to make up for the missed classes and whether the educational path can be continued at all (B, C, G).

Another finance related need involves financial options, if the work cannot be continued due to late or long-term effects of the cancer treatment. Without support from family, friends and official carriers, major financial problems can occur. A future pension may be too small or too low due to missing work hours, which especially impacts young adults (E).

In aftercare, social context includes the need for reports from peers about their cancer patient journey (L), as well as the service need for support groups to connect with peers (A, I). Especially during this stage, empathetic peers are important so that young adults can discuss their experiences and to feel understood (H).

Sometimes I needed someone to talk shit about what happened. And I had the feeling that this is easier with people who are going through something similar than with others. (H)

When no contact addresses or information sources are provided, some of the participants seek them on the internet or social media (A, D, H, I, M). Only three participants explained that they have not sought peers (A, B) or even thought of it (G). While A and G’s reason was unsuspectingness, B showed no interest in meeting peers.

The fourth theme is prognosis. The need of this already occurs during the diagnosis stage where the information is mixed with needs regarding diagnosis-specific questions, but it becomes significant again after the completion of treatments. Some information needs that were identified are about death (C, E, G, I), recurrences (D), metastases (J, N) relapses (K), incurability and how to handle these problems (E, F, I). While some participants want to know everything (D, H), others avoid this information deliberately (B).

I still have a lot of questions today that no one could, would or can answer. No idea. Actually, my whole cancer journey was like this. I had questions that no one could really answer. (D)

Health practices is the fifth theme and contains the same needs as explained before.

Another theme is mental health. At the beginning of the cancer patient journey, young cancer patients receive psychological offers. This service need is thus directly covered. However, psychological support is often needed after ending treatment. At this point options are missing and young adults have to take care of it on their own (D, E, H, N).In all honesty, I really needed psychological help after treatment because I fell into the typical treatment hole. At the beginning you are offered a lot of help, but I didn’t need it because I had the feeling that I was actively doing something. And afterwards, when it was all over, you stand there like you’ve been run over by a truck, think to yourself: “Ok, now I’m sort of stuck here again, like a cup that’s fallen off and somehow I don’t really get any help anymore, do I? (D)

Only a few cancer centres offer psychological support during the entire cancer treatment and aftercare. In contrast to other regions in Germany, the participants who were treated at those centres were satisfied and expressed no need for improvement (F, H).

Rehabilitation is the seventh theme and only occurs during aftercare. The majority of participants participated in rehabilitation and got information from their doctors, medical assistants or social support. However, an unmet information need was identified regarding options specific to young adults with cancer (C, H, I, K, M, N). Besides this, there is also a service need regarding offers for parents, who want to integrate their children into rehabilitation (C, I, M). The last theme at the stage of aftercare is named aftercare itself, since it includes needs that occur exclusively during aftercare, even if there are similarities to other identified themes. Because of the changes in body and mind due to cancer, there is a recognisable need for information about aftercare, and this area has not yet been sufficiently covered (H). In this context, information about specific sport, care and treatment offerings for cancer patients (C, E, F, I, L, N), and concrete contact options and referrals to experienced doctors are desired (H, K). The wealth of information also leads to an information overload, which has a negative impact on the young adults (H).

All identified needs and requests for improvement, designated as wishes are summarised in figure 2, figure 3 and figure 4.

Discussion

This study identified ten themes regarding information needs of young adults with cancer in Germany. The themes were additionally mapped to three main stages of the cancer patient journey. As with Zebrack (2010), Barnett, et al. (2016) and Lea, et al. (2020), not only information needs but service and care needs were identified. This seems logical, since needs in these three areas are closely interrelated and equally influence patients’ management of their life-threatening disease. While information is needed to facilitate coping-mechanisms to deal with the disease and the resulting problems and adjustments, service and care needs require infrastructure and social support. Not all needs that were identified are specifically for young adults, but the need to focus on young adults was apparent.

Comparison to international studies

Nearly all the themes are comparable with needs identified in existing international studies. One distinction is the theme mental health, which is not part of comparable international studies (Keegan, et al., 2012; McCarthy, et al., 2018). This absence can be explained by differences in the health infrastructures in Australia and the United States, compared to Germany. In those countries, the development of cancer centres and programmes that directly address the needs of young adults with cancer started in the early 2000s. Patients are thereby not only represented by organisations outside cancer centres and hospitals, but also receive comprehensive care, like psychological care that is complementary to treatments (Ferrari, et al., 2010; Stark, et al., 2015; US National Cancer Institute, 2018). In Germany, progress has also been made in recent years, by the development of a medical care and treatment guideline for young adults (Hilgendorf, et al., 2163), by the establishment of support groups and by the German foundation of young adults with cancer. However, the automatic integration of these infrastructures into the treatment process is still missing, as the identified theme mental health is proving. This assumption is supported by the fact that participants of this study, who were offered psychological support throughout their entire cancer patient journey, did not express any needs in this field, similar to the mentioned international studies. Since the participants also mentioned that psychological support is rare at the end of treatments and during aftercare although they need it, all hospitals and cancer centres should integrate psychological service during the whole cancer journey.

Another theme, that distinguishes the results of this study to the results of comparable international studies is the organization during treatments and aftercare. The current study reveals that young adults in Germany have to engage directly with health services on their own and feel overwhelmed, because doctors as well as health workers rely on their capacity for self-management. While in contrast McCarthy, et al. (2018) identified a need regarding the activation of young adults towards self-management, to integrate them more in the decision-making for their own patient journey, young patients in Germany feel left alone. Decisions and appointments are often their task which results in too much responsibility. This distinction should be analysed further in the future.

As Zebrack (2008) already stated, the social context of young adults changes because of their age, and is influenced by a cancer diagnosis. Nevertheless, social context related needs could not be found during his analysis. However, some recent medical studies on information needs as well as this study were able to identify this issue (Lea, et al., 2018, 2020; McCarthy, et al., 2018). Since young adults are often treated with older patients, it is harder for them to find peers with similar experiences. As the study revealed, only one participant intentionally decided not to seek peers during or after treatments. All other participants reported the need or wish for both empathy and the exchange of advice by peers. For this reason, a solution could be to proactively speak about services such as the German Foundation for Young Adults with Cancer during consultations. As noted by Abrol, et al. (2017), Lea, et al. (2018) and Aggarwal, et al. (2020), young adults sometimes use digital sources to meet peers, therefore highlighting digital support groups or helpful web addresses at the diagnosis stage would be helpful too.

Although information needs regarding fertility were identified as by Zebrack (2008), Keegan, et al. (2012), Bellizzi, et al. (2012), Matsuyama, et al. (2013) and McCarthy (2018), the results demonstrate, that these needs are mostly answered during doctor consultations. This is probably due to the fact that a new law was passed in 2019 to ensure that young cancer patients are financially supported by their health insurance companies and the resulting increased attention to the topic in general (German Foundation of young adults with cancer, 2022b).

The stage of aftercare

The stage of aftercare includes many identified needs and requests for improvement. Both Keegan, et al. (2012) and McCarthy, et al. (2018) as well as Zebrack (2008) did not identify needs regarding aftercare. This theme, as well as rehabilitation, is often omitted from cancer studies because it starts after active treatment ends (Feuerstein, 2007; Hauken, 2014; Rutten, et al., 2016). Therefore, limited research has been done on this area (Lea, et al., 2020) which leads to less provided information and fewer services, as well as unmet information and service needs, as the results of this study reveal.

Since many needs occur during this stage, both, the provision of information and the range of services should be enhanced for the optimal care even after active treatment ends. This includes contacts to helpful doctors, sports and nutrition offers adapted to the after- or long-term effects of the disease, as well as psychotherapy and suitable rehabilitation offerings.

Information overload

Previous research on cancer information behaviour has shown that information overload is indicated by seeking cancer related information (Chae, et al., 2016; Serçekus, et al., 2020). This study validated this for two themes: health practices and aftercare. Numerous sources provide contradictory information, which lead to uncertainty and stress for all cancer patients, as also Kim et al. (2007) recognized. To prevent this, reliable and easy understandable information carriers are needed (Serçekus, et al., 2020). The participants of the current study expressed the need for a reliable information source as well. Therefore, the development of such a source, and making it available during the stages of treatment(s) and aftercare is important.

Met and unmet needs

Even though the focus was not specifically the identification of met or unmet needs, some insights emerged during the data analysis. Similar to Nanton (2010), McCarthy, et al. (2018) and the only comparative study from Germany by Goerling, et al. (2020), the medical information needs for diagnosis-specific questions and for information about prognosis are already well answered. The same cannot be said about the needs of the other eight themes. In summary, improvements in the information and service provision in the health care infrastructure for young adults with cancer in Germany are still necessary for each stage of the cancer patient journey, especially non-medical information about service and care needs. In particular, the requests for improvement, formulated as wishes (s. figure 2-4), should be considered.

Limitations

Because of its small sample, which does neither include all regions of Germany or all kinds of cancer, this study does not claim completeness regarding identified needs. Only the subjective perception of the participants was analyzed, which is why no analysis of all existing health infrastructures or differences in treatment of different types of cancer was carried out.

Conclusion

The analysis of subjective perceptions of young adults with cancer in Germany revealed ten themes, in which information, service and care needs occur. The analysis can be summarised that the German health infrastructure does not yet match the needs of young adults.

The following recommendations for improvement are based on the needs that were identified:

- Regarding information needs

- A single information source (e.g. guideline) that summarises all important organisational information, provides guidance, and contains tips and helpful contacts throughout the entire cancer patient journey.

- One reliable information source for effective health practices, thematically sorted.

- An age-specific referral to peers with cancer at the stage of diagnosis

- An age-specific referral to doctors with experience in attending young cancer patients in aftercare

- Regarding service needs

- The development of age-specific rehabilitation facilities targeting status groups (f.e. students/employed, parents/childless)

- Support services in form of one person, who answers organisational information needs and assists managing organisational aspects at the entire cancer patient journey

- Regarding care needs

- More time with supervising doctors to ask questions

- The active option for psychotherapy after treatment(s) end

The information behaviour perspective on this topic allowed for an intensive examination of individual needs, rather than a survey-based, quantifiable overview of given needs. As this can potentially lead to improvements for all young cancer patients, further qualitative studies in the field of health information behaviour should be conducted in the future. A lot of improvement remains necessary for young adults with cancer in Germany.

Acknowledgements

The author wants to thank the German foundation of young adults with cancer, for disseminating the call for participants over all of their regional channel.]

About the author

Paulina Bressel is a doctoral student and lecturer at the Berlin School of Library and Information Science at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Her research interests are in health information behaviour and qualitative research designs. She can be contacted at p.bressel@hu-berlin.de

References

- Abrol, E., Groszmann, M., Pitman, A., Hough, R., Taylor, R.M. & Aref-Adib, G. (2017). Exploring the digital technology preferences of teenagers and young adults (TYA) with cancer and survivors: a cross-sectional service evaluation questionnaire. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 2017(11), 670-682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-017-0618-z

- Adams, E., Boulton, M., & Watson, E. (2009). The information needs of partners and family members of cancer patients: a systematic literature review. Patient education and counseling, 77(2), 179-186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.027

- Aggarwal, R., Hueniken, K., Eng, L., Kassirian, S., Geist, I., Balaratnam, M.L., Paulo C.B., Geist, A., Rao, P., Mitchell, L., Magony, A., Jones, J.M., Grover, S.C., Brown, M.C., Bender, J., Xu, W., Liu, G. & Gupta, A.A. (2020). Health-related social media use and preferences of adolescent and young adult cancer patients for virtual programming. Support Care Cancer, 2020(28), 4789-4801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05265-3

- Ahmad, S.S., Reinius, M. AV., Hatcher, H.M. & Ajithkumar, T.V. (2016). Anticancer chemotherapy in teenagers and young adults: managing long term side effects. BMJ, 2016(354), i4567. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4567

- Attfield, S. J., Adams, A., & Blandford, A. (2006). Patient information needs: pre- and post- consultation. Health Informatics Journal, 165-177. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458206063811

- Barnett, M., McDonnell, G., DeRosa, A., Schuler, T., Philip, E., Peterson, L., Touza, K., Jhanwar, S., Atkinson, T. M., & Ford, J. S. (2016). Psychosocial outcomes and interventions among cancer survivors diagnosed during adolescence and young adulthood (AYA): a systematic review. Journal of cancer survivorship: research and practice, 10(5), 814-831. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0527-6

- Belkin, N. (1980). Anomalous States of Knowledge as a basis for Information Retrieval. The Canadian Journal of Information Science. 1980(5), 133-143.

- Bellizzi, K.M., Smith, A., Schmidt, S., Keegan, T.H.M., Zebrack, B., Lynch, C.F., Deapen, D., Shnorhavorian, M., Tompkins, B.J., Simon, M. & the Adolescent and Young Adult Health Outcomes and Patient Experience (AYA HOPE) Study Collaborative Group (2012). Positive and negative psychosocial impact of being diagnosed with cancer as an adolescent or young adult. ACS Journals, 2012(118), 5155-5162. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.27512

- Brailsford, S.C., Lattimer, V., Tarnaras, P. & Turnbull, J. (2004). Emergency and On-Demand Health Care: Modelling a Large Complex System. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 55(1), 34-42. https://10.1057/palgrave.jors.2601667

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bressel, P. (2021). Die übergangenen Patient*innen: Eine qualitative Analyse der Informationsbedarfe von jungen Erwachsenen mit Krebs in Deutschland (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Master thesis). https://10.18452/22913

- Chae, J., Lee, C-J. & Jensen, J.D. (2016). Correlates of Cancer Information Overload: Focusing on Individual Ability and Motivation. Health Communication, 31(5), 626-634. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2014.986026

- DeRouen, M.C., Smith, A.W., Tao, L., Bellizzi, K.M., Lynch, C.F., Parsons, H.M., Kent, E.E. & Keegan, T.H.M. (2015). Cancer-related information needs and cancer's impact on control over life influence health-related quality of life among adolescents and young adults with cancer. Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer, 24(9), 1104-1115. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3730

- Dervin, B. (1983). An overview of sense-making research: Concepts, methods and results. [Paper presentation]. The annual meeting of the International Communication Association, Dallas, TX, May. https://faculty.washington.edu/wpratt/MEBI598/Methods/An%20Overview%20of%20Sense-Making%20Research%201983a.htm. (Internet Archive)

- Domínguez, M., & Sapiña, L. (2017). "Others Like Me". An Approach to the Use of the Internet and Social Networks in Adolescents and Young Adults Diagnosed with Cancer. Journal of cancer education: the official journal of the American Association for Cancer Education, 32(4), 885-891. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-016-1055-9

- Fernandez, C. V., & Barr, R. D. (2006). Adolescents and young adults with cancer: An orphaned population. Paediatrics & child health, 11(2), 103-106. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/11.2.103

- Ferrari, A., Thomas, D., Franklin, A.R.K., Hayes-Lattin, B.M., Mascarin, M., Van der Graaf, W. & Albritton, K.H. (2010). Starting an Adolescent and Young Adult Program: Some Success Stories and Some Obstacles to Overcome. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2010(28), 4850-4857. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.23.8097

- Feuerstein M. (2007). Defining cancer survivorship. Journal of cancer survivorship: research and practice, 1(1), 5-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-006-0002-x

- German Foundation for young adults with cancer (2022a). Motivation & Goals. https://junge-erwachsene-mit-krebs.de/about-us/motivation-and-goals/?lang=en (Internet Archive)

- German Foundation for young adults with cancer (2022b). Cancer and becoming a parent. https://junge-erwachsene-mit-krebs.de/moving-forward/improving-care/cancer-and-becoming-a-parent/?lang=en (Internet Archive)

- Germeni, E., & Schulz, P.J. (2014) Information seeking and avoidance throughout the cancer patient journey: two sides of the same coin? A synthesis of qualitative studies. Psycho‐Oncology, 2014(23), 1373-1381. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3575

- Goerling, U., Faller, H., Hornemann, B., Hönig, K., Bergelt, C., Maatouk, I., Stein, B., Teufel, M., Erim, Y., Geiser, F., Nicke, A., Senf, B., Sickert, M., Büttner-Teleaga, A. & Weis, J. (2020). Patient Education and Counseling, 103(1), 120-126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.08.011

- Halkett, G.K.B., Kristjanson, L.J., Lobb, E., O’driscoll, C., Taylor, M. & Spry, N. (2010). Meeting breast cancer patients’ information needs during radiotherapy: what can we do to improve the information and support that is currently provided? European Journal of Cancer Care 2012(19), 538-547. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01090.x

- Hauken, M.A. (2014). „The cancer treatment was only half the work!“ A mixed-method study of rehabilitation among young adult cancer survivors (doctoral thesis). Bergen Open Research Archive. University of Bergen. https://hdl.handle.net/1956/9332

- Hilgendorf, I., Borchmann, P., Engel, J., Heußner, P., Katalinic, A.N., Neubauer, A., Rahimi, G., Willenbacher, W. & Wörmann, B. (2016). Heranwachsende und junge Erwachsene (AYA, Adolescents and Young Adults). https://www.onkopedia.com/de/onkopedia/guidelines/heranwachsende-und-junge-erwachsene-aya-adolescents-and-young-adults/@@guideline/html/index.html (Internet Archive)

- Jiang, S. & Liu, L.L. (2020). Digital divide and Internet health information seeking among cancer survivors: A trend analysis from 2011 to 2017. Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer, 29(1). 61-67. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5247

- Johnson, J.D. & Case, D.O. (2012). Health Information Seeking. Peter Lang Publishing Inc.

- Kaal S.E., Husson, O., Van Dartel, F., Hermans, K., Jansen, R., Manten-Horst, E., Servaes, P., Van de Belt, T.H., Engelen, L.JLPG, Prins, J.B., Verberne, S., Van der Graaf, W.T.A. (2018). Online support community for adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer: user statistics, evaluation, and content analysis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018(12), 2615-2622. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S171892

- Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (2021). Einheitlicher Bewertungsmaßstab (EBM). Stand: 4. Quartal 2020. https://www.kbv.de/media/sp/EBM_Gesamt_-_Stand_4._Quartal_2020.pdf (Internet Archive )

- Keegan, T.H.M., Lichtensztajn, D.Y., Kato, I., Kent, E.E., Wu, X.C., West, M.M., Hamilton, A.S., Zebrack, B., Bellizzi, K.M., Smith, A.S. & the AYA HOPE Study Collaborative Group (2012). Unmet adolescent and young adult cancer survivors information and service needs: a population-based cancer registry study. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 2012(6), 239-98250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-012-0219-9

- Kim, K., Lustria, M., Burke, D., & Kwon, N. (2007). Predictors of cancer information overload: findings from a national survey. Information Research, 12(4) paper 326. http://InformationR.net/ir/12-4/paper326.html (Internet Archive)

- Lambert, S. D., Loiselle, C. G., & Macdonald, M. E. (2009). An in-depth exploration of information-seeking behavior among individuals with cancer: Part 1: Understanding patterns of disinterest and avoidance. Cancer Nursing, 32(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NCC.0000343372.24517.bd

- Lambert, S. D., Loiselle, C. G., & Macdonald, M. E. (2009). An in-depth exploration of information-seeking behavior among individuals with cancer: Part 2: Understanding patterns of disinterest and avoidance. Cancer Nursing, 32(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NCC.0000343373.01646.91

- Lea, S., Martins, A. Morgan, S., Cargill, J., Taylor, R.M., Fern, L.A. (2018). Online information and support needs of young people with cancer: a participatory action research study. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 2018(9), 121-135. https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S173115

- Lea S, Martins A, Morgan S, Cargill J, Taylor RM, Fern LA. Health care professional perceptions of online information and support for young people with cancer in the United Kingdom. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 2019(10), 103-116. https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S211142

- Lea, S., Martins, A., Fern, L.A., (2020). The support and information needs of adolescents and young adults with cancer when active treatment ends. BMC Cancer 20(697). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07197-2

- Leuteritz, K., Friedrich, M., Sender, A., Nowe, E., Stoebel-Richter, Y. & Geue, K. (2018). Life satisfaction in young adults with cancer and the role of sociodemographic, medical, and psychosocial factors: Results of a longitudinal study. ACS Journals, 124(22), 4374-4382. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31659

- Matsuyama, R.K., Kuhn, L.A., Molisani, A., & Wilson-Genderson, M.C. (2013). Cancer patients’ information needs the first nine months after diagnosis. Patient Education and Counseling. 90(1), 96-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.09.009

- McCarthy, M.C., McNeil, R., Drew, S., Orme, L. & Sawyer, S.M. (2018). Information needs of adolescent and young adult cancer patients and their parent-carers. Support Care Cancer 2018(26), 1655-1664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3984-1

- Nanton, V., Docherty, A., Meystre, C. & Dale, J. (2010). Finding a pathway: Information and uncertainty along the prostate cancer patient journey. British Journal of Health Psychology, 2009(14), 437-458. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910708X342890

- Perales, M., Drake, E., Pemmaraju, N. & Wood, W. (2016). Social Media and the Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Patient with Cancer. Current Hematologic Malignancy Reports, 11(6), 449-455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11899-016-0313-6

- Petersen, E., Jensen, J.G. and Frandsen, T.F. (2021). Information seeking for coping with cancer: a systematic review. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 73(6), 885-903. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-01-2021-0004

- Robert Koch Institut (2019). Krebs in Deutschland für 2015/2016 (12th ed.). Zentrum für Krebsregisterdaten.

- Rutten, L.J.F., Agunwamba, A.A., Wilson, P., Chawla, N., Vieux, S., Blanch-Hartigan, D., Arora, N.K., Blake, K. & Hesse, B.W. (2016). Cancer-Related Information Seeking Among Cancer Survivors: Trends Over a Decade (2003–2013). Journal of Cancer Education, 2016(31), 348-357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-015-0802-7

- Serçekuş, P., Gencer, H. & Özkan, S. (2020). Finding useful cancer information may reduce cancer information overload for Internet users. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 37(4), 319-328. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12325

- Shay, L.A., Parsons, H.M. & Vernon, S.W. (2017). Survivorship Care Planning and Unmet Information and Service Needs Among Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 6(2), 327-332. http://doi.org/10.1089/jayao.2016.0053

- Stark, D., Bielack, S., Brugieres, L., Dirksen, U., Duarte, X., Dunn, S., Erdelyi, D.J., Grew, T., Hjorth, L., Jazbec, J., Kabickova, E., Konsoulova, A., Kowalczyk, J.R., Lassaletta, A., Laurence, V., Lewis, I., Monrabal, A., Morgan, S., Mountzios, G., Olsen, P.R., Renard, M., Saeter, G., Van Der Graaf, W.T. & Ferrari, A. (2016). Teenagers and young adults with cancer in Europe: from national programmes to a European integrated coordinated project. European Journal of Cancer Care, 2016(25), 419-427. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12365

- Tran, Y., Lamprell, K., Easpaig, B.N.G., Arnolda, G. & Braithwaite, J. (2018). What information do patients want across their cancer journeys? A network analysis of cancer patients’ information needs. Cancer Medicine, 2019(8), 155-164. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.1915

- US National Cancer Institute (2018). Introduction to Adolescent and Young Adult Cancers [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1mIAbOE7Jkg

- Valle, C.G, Tate, D.F, Mayer, D.K, Allicock, M, Cai, J. A (2013). Randomized trial of a Facebook-based physical activity intervention for young adult cancer survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivership: research and practice, 7(3), 355-368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0279-5

- Wilson, T.D. (1981). On User Studies and Information Needs. Journal of Documentation, 37(1), 3-15. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb026702

- Zebrack, B.J., Mills, J. & Weitzman, T.S. (2007). Health and supportive care needs of young adult cancer patients and survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship: research and practice 1(2), 137-145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-007-0015-0

- Zebrack, B. (2008). Information and service needs for young adult cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2008(16), 1353-1360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-008-0435-z

- Zebrack, B., Hamilton R., Smith, A.W. (2009). Psychosocial outcomes and service use among young adults with cancer. Seminars in Oncology, 35(5), 468-77. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.07.003

- Zebrack, B., Chesler, M.A. & Kaplan, S. (2010). To foster healing among adolescents and young adults with cancer: What helps? What hurts?. Support Care Cancer, 2010(18). 131-135.

How to cite this paper

Appendix

| Cancer type | Subtype | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | Triple negative mammary carcinoma (genetic) | Pregnant during treatment |

| Specific diagnosis unknown | ||

| Hormone-positive mammary carcinoma [1] Triple negative mammary carcinoma (genetic) [2] | [1] Initial diagnosis [2] Second diagnosis | |

| Hormone-positive mammary carcinoma + Liver metastases, Lung metastases | Incurable due to spreading | |

| Brain tumor | Glioblastoma | Incurable |

| Anaplastic astrozytoma (sinistral) | ||

| Testicular cancer | Testicular carcinoma (unilateral) | |

| Thyroid cancer | Papillary thyroid carcinoma + Metastases + Lymphatic gland | |

| Bone tumor | Ewing’s sarcoma (Scapula unilateral) | |

| Lymphoma | Hodgkin‘s lymphoma | |

| Uterus cancer | Endometrium carcinoma | |

| Salivary glands cancer | Mucoepidermoid carcinoma |