Acceptance of new health and communication technology by older adults

Ágústa Pálsdóttir

Introduction. The study focuses on the health information behaviour of people at the age of 60 years and older, with an emphasis on the adoption of information and communication technology, and differences by their socio-demographic background.

Method. A survey was used to collect the data from a random sample of 300 people aged 60 years and older. The response rate was 42

Analysis. Participants were divided up in two groups, people aged 60 to 67 years old, and people aged 68 years or older. Differences across sex and education were examined for each age group and Tuckey test used to examine if differences were significant

Results. Although the majority in both age groups were interested in health information, including information in digital form, they had not yet adopted new health information and communication technology. People in the younger group considered it difficult to take new technology in use and both age groups found it difficult to get help using technology.

Conclusions. It is not sufficient to make new information and communication technology available. For older adults to be ready to accept new technology and take it into use, they must be offered training at using it and technical support as needed.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irisic2216

Introduction

It is of major importance to support and enhance people’s possibilities to remain as healthy and active members of society, for as long as possible. The changes in the age distribution, with societies all over the world ageing rapidly, pose great challenges. From 2013 to 2050 it is expected that the number of people aged 60 years and older will more than double globally (United Nations, 2013; World Health Organization,2007). This calls for the welfare society to react to the growing proportion of older people and ensure their prospects for health and wellbeing.

People's potential for life-long learning and informed decisions making about their health is a crucial issue. The importance of making the right behavioural choices for maintaining health has been described as a joint responsibility of individuals and society (Resnik, 2007; Wikler, 2002).

The society has an obligation to provide people with the means to add to their knowledge about healthy living and individuals need to respond by taking advantage of it. As a prerequisite for this, it is necessary for them to possess the motivation and belief that they are capable of improving their health (Pálsdóttir, 2008). It is equally important to support their means to gain knowledge and understanding about healthy living, and for this it is imperative that they have an easy access to information that satisfy their needs.

In the past years there have been great advancements in the way that information can be communicated and accessed. Health information is increasingly being disseminated digitally (Brand, et al., 2018), and people are constantly required to adjust to and learn about recent advances in their information environment. Given the growing amount of information that can be gathered from digital sources it is essential to recognize how people accept new technology and make use of it to gather information about their health history and healthy lifestyle.

This study examines health information behaviour by conducting a survey among 300 people who have reached the age of 60 years and older. The emphasis is on their adoption and use of information and communication technology, as well as differences by their socio-demographic background. Thus, the study seeks to understand how well the needs of older adults for access to digital health information are being met.

Literary review

Advances in digital technology and the growing amount of digital health information has brought new possibilities for people to manage their own health, practice better self-care and improve their health behaviour. Norman and Skinner (2006) have introduced the concept of eHealth literacy and defined it as ‘the ability to seek, find, understand, and appraise health information from electronic sources and apply the knowledge gained to addressing or solving a health problem’. Thus, to be able to benefit from digital health information demands that people possess the informational and technological competence which is required to take advantage of the digital information environment (Bol, et al., 2016).

The information environment has become more complex, particularly as knowledge about health is increasingly being disseminated through various digital sources. Older adults have been found to adopt new technology at a slower rate than those who are younger (Anderson and Perrin, 2017; Statistics Iceland, 2014; Vorrink, et al., 2017; Vroman, et al., 2015). The argumentation is sometimes that because technological solutions are targeted more towards those who are younger, the older generation is being left behind (Piper, et al., 2010).

Various factors have been found to cause challenges and have an impact on older people’s use of information technology. Socio-demographic factors have been identified (Kolotylo-Kulkarni, et al., 2021), in particular people with higher education have been reported to be more likely to use information and communication technology (Hargittai and Dobransky, 2017; Sabelli, 2020; Vroman, et al., 2015). This also includes physical issues, such as weak physical condition and health problems (Anderson and Perrin, 2017), problems with the visual and auditory presentation of information (Loos and Romano Bergstrom, 2014; Rosales and Fernández-Ardèvol, 2019; World Health Organization, 2007), and changes in the motor ability which people can experience as they grow older (Loos and Romano Bergstrom, 2014; Hoogendam, et al., 2014; Rosales and Fernández-Ardèvol, 2019; World Health Organization, 2007).

Furthermore, older people often rely on assistance from others (Pálsdóttir, 2011b), and factors such as lack of confident in their abilities to use technology and the need for help from others to start to use new technology have been reported to influence their use of it (Anderson and Perrin, 2017; Sabelli,2020).

Rosales and Fernández-Ardèvol (2019) have found indications that older adult’s choice of information channels is based on their 'values, style, habits and long-term perspective' (p. 63), which are among the reasons that limit their use of smartphones and leads them instead to gather information by means that are well known to them. Lack of trust in digital health information sources has been pointed out (Eriksson-Backa, 2012; Pálsdóttir, 2011a; Soederberg Miller and Berg, 2012). Prior results have for example revealed that, although senior citizens sought health information on the Internet more frequently in 2012 than they did in 2007, they had at the same time become more critical of the information and considered it both less useful and less reliable (Pálsdóttir, 2015). There are also indications that, to identify health information that they can trust, people prefer to get support from health professionals (Lee, et al., 2017).

It is therefore important that people have access to quality information about healthy behaviour. Likewise, for people to be able to actively manage their health, it is imperative that they can access information about their health condition. Electronic health records have been reported to hold several benefits for people, such as leading to better health knowledge, improvements in health behaviour, and engagement in self-management, as well as having positive effects communication with health professionals (Tapuria, et al.,2021). Beliefs about beneficial outcomes among older adults were also found in a study not restricted to electronic health records (Huvila, et al., 2018). Tapuria, et al. (2021), however, further reported that even if people who are 60 years and older express interest in accessing their electronic health records, they are less likely to use the access, and if they do so it is in a more limited way, than those who are younger

Nevertheless, there has been a substantial growth in older adults’ use of digital sources. This includes the use of the Internet from home, as well as the use of mobile technology such as smartphones (Anderson and Perrin, 2017; Statistics Iceland, 2014). Mendiola, et al. (2015) have suggested that the use of health apps in smartphones will create increasing opportunities for people to practice health care management. Their findings indicate that it is important that health apps are simple and intuitive to use, with an easy input of health data, and that they possess features that save time over current methods. This corresponds to previous evidence, that if older people find the technology easy to use, they are more inclined to do so (Tsai, et al., 2015). Thus, the usability of information and communication technology matters. Likewise, it is of significance how older people perceive the benefit of the information that can be reached by information and communication technology. There are indications that their attitude towards the adoption of smartwatches for health information is influenced by how they perceive the value of it (Todd, et al., 2019). If they believe that digital information has a high value for them, for example by receiving information that is tailored to their own needs, they are more encouraged to use digital solutions (Jimison, et al., 2008). Thus, the relevance of digital information is important, and if older people consider it to be high, they are more motivated and prone to make more effort at seeking it (Loos, 2012).

There is a widespread access to the Internet in Iceland, with 95% of the population connecting to it at least ones a week (Statistics Iceland, 2014). In that regard, the conditions for obtaining digital health information can be considered excellent. However, because access to the Internet does not necessarily translate into the use of digital health information (Ono and Zavodny, 2007), other aspects related to the use of health technology need also to be considered. Steps have been taken to improve access to health information. A new legal framework was set in 2009 to ensure people the right to access to their health history through their health records, however many of the files are not yet in a digital form (Health Records Act, 2009). The latest initiative is the development of the information communication system Heilsuvera, which is a multpurpose tool. Through the system's Website, access to a wide range of information from health professionals about diseases, health issues and healthy lifestyle is being offered. Thus, the Website allows users the opportunity to seek, examine, and gain knowledge from reliable health sources. Heilsuvera is also a communication system for health professionals and the users. This part of the system offers various functions that provide a possibility for people to get various health information tailored to their own needs. It allows people, for example, to book appointments with their physicians or other specialists, drug prescriptions can be examined and requests for renewal sent, history of vaccinations can be observed, and short questions or comments can be send physicians and answers from them received. During opening hours, a health professional is available for webchat. Some parts of people’s health history are already being recorded into the system daily, while other types of access are still under development. This includes for example health records made during doctors’ appointments, which are not accessible yet through the system (Directory of health, 2016).

Aim and research questions

The aim of the study is to explore how the health information behaviour of Icelanders´ who have reached the age of 60 years or older, with an emphasis on how they have taken new health information and communication technology into use, and how they perceive their possibilities to do so. People aged 60 or over are, however, not a homogeneous group but can consist of many different social groups with different backgrounds and it is necessary to take this into account.

The study will seek answers to the following research questions: 1) How motivated are older adults towards health information and how does it connect to their age, sex, and education? 2) How do older adults use recently available information and communication technology to access information about their health history and about healthy lifestyle and how does it connect to their age, sex, and education? 3) How do they evaluate their possibilities to adopt new information and communication technology and how does it connect to their age, sex, and education?

The purpose of addressing this is to understand better how older adults can benefit from development in information and communication technology and enhance their abilities to adopting healthier lifestyle through health information. An improved awareness of the issue may help to identify their needs for support at using health information and communication technology and increase the efficiency of providing them with digital health information.

Methods

Because the intention is to be able to generalize the results of the study to people age 60 years and older in Iceland, a survey method was chosen. Data for the study were gathered in from November 2018 to January 2019 by using a telephone survey in Icelandic, conducted by the Social Science Research Institute. A sample of 300 people aged 60 years and older, from the whole country, randomly selected from the National Register of Persons in Iceland, was used. The response rate was 42%.

In Western countries it has been traditional to use the retirement age to define older adults (Thane, 1989), and in Iceland elderly is defined by law as people who have reached the age of 67 (Lög um málefni aldraðra nr. 125/1999), when it is usual for people to retire. This has, however, been criticised for not taking into consideration the heterogeneity of older people (Berger, 1994). It has been pointed out that people’s chronological age is less important than determinants, like their physical, cognitive, and social capabilities (Ries and Pöthiga, 1984). In accordance with the viewpoints, that there is not a clearly defined age when people become senior citizens, the associations for senior citizens in in Reykjavík and neighbouring communities (https://www.feb.is/um-felagid/) admit those who have reached the age of 60 to become members. It was decided, in view of this, that people who have reached the age of 60 should be included in the study, and that those who are at the age 60 to 67 years, a group who is approaching retirement, should be compared with people aged 68 years or older, who have reached the retirement age.

Because of the response rate in the study, the data were weighted by gender (male, female), age in six categories, residence (within or outside the capital area) and education (primary, secondary, university) of participants so that they so that it corresponds with the distribution in the population. Reference figures for age, gender and place of residence were obtained from the National Registry of Iceland and for level of education from Statistics Iceland. Table 1 shows the number of participants before and after the data has was weighed.

| Participants | Before weighing the data (no) | After weighing the data (no) |

|---|---|---|

| 60-67 years | 51 | 66 |

| 68 years and older | 75 | 99 |

Measurements and analysis

In addition to the socio-demographic information, which included the background variables education, sex, age, residence and income, the measurements consisted of four sets of questions:

1. Motivation towards health information was examined by two questions: 1) How interested the participants are in information about health and lifestyle; 2) How often they discuss the topic with others. A five-point response scale was used (Very interested/often – Very low interest/Never).

2. One question examined how important it was for the participants to have full access to their health history through electronic health records. A five-point response scale was used (Very important – Very unimportant).

3. Use of health information and communication technology was examined by four questions: 1) The participants use of the health information and communication technology system ‘Heilsuvera’ in relation to their own health, for example communicate with doctors or other health professionals, book appointments, view drug prescriptions, or send messages to their doctor; 2) The use of ‘Heilsuvera’ to seek information about various health issues; 3) The use of apps in smartphones or smartwatches to monitor or record health information; 4) The use of a blood pressure monitors to record their health information. A five-point response scale was used (Very often – Never).

4. Possibilities of taking new health information and communication technology in use was examined by two questions in the form of statements: 1) How difficult it is to begin to use new technology; 2) How easy it is to get help at using technology when needed. A five-point response scale was used (Strongly agree – Strongly disagree).

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was used for the analysis of the weighed data. Chi-square tests were performed and based on previous analysis of the data it was decided to examine differences across sex and education for each age group.

Results

The chapter starts by presenting results about the participants motivation towards receiving health information and after that the importance of having access to health records. This will be followed by results about the use of the information and communication system Heilsuvera, the use of smartphones/smartwatches, and blood pressure monitors. Finally, results about the participants experience of taking new information and communication technology in use and their possibilities of getting help at it will be introduced. Furthermore, results from the analysis by background variables where significant differences were revealed will be introduced.

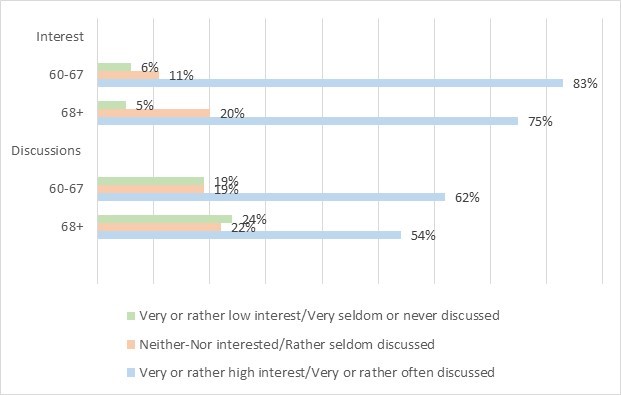

Figure 1 presents results about the participants motivation towards receiving health and lifestyle information.

Participants in both age groups were in motivated towards getting health information, however, those who are at the age 60 to 67 years were more likely to be so than those who are 68 years or older. The majority of both groups claimed to be either very or rather interested in information about the topic and over half of them discussed it very or rather often with others (Figure 1).

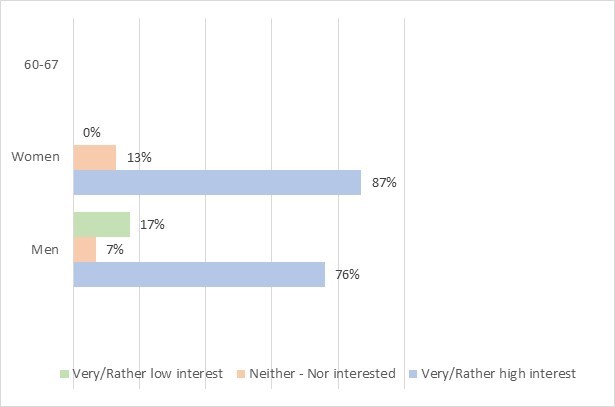

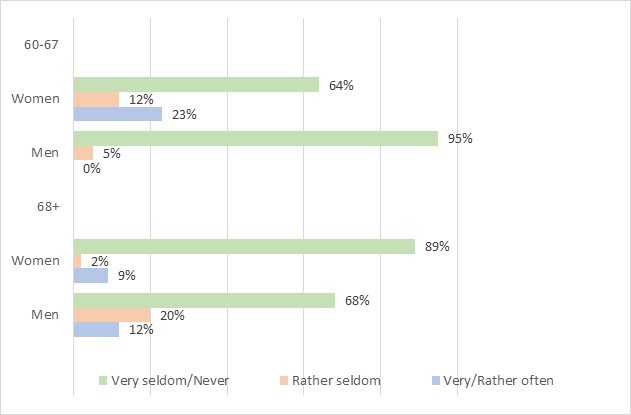

Analysis by background variables revealed a significant difference by sex in the younger age group in how interested the participants were in information. As figure 2 shows, women showed more interest in health information than men (p< 0.05).

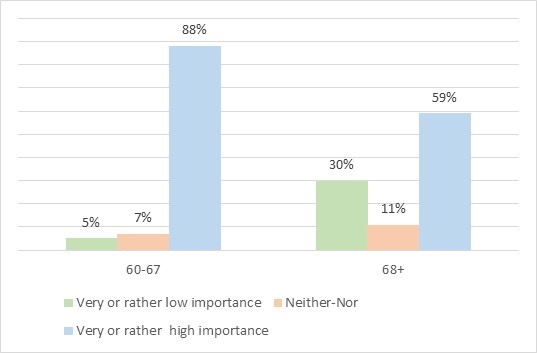

The participants were furthermore asked how important it was for them to have full access to their health history through electronic health records. The results are presented in Figure 3.

As can be seen from Figure 3, the majority in both groups considered it rather or very important to have full access to their health history through electronic records. The younger group was though more likely to find this important than the older group, and a higher portion of those who are older considered it to be of very or rather low importance.

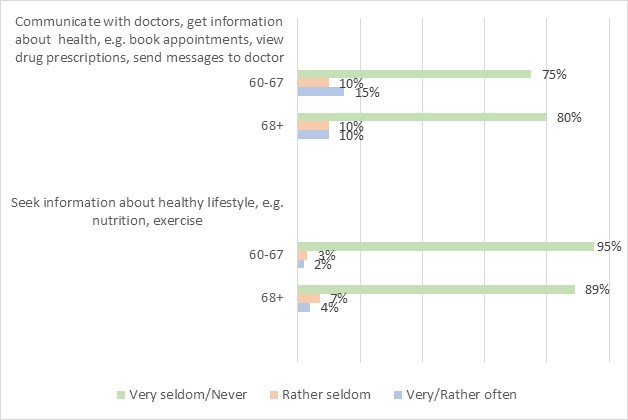

Two questions examined the participants use of the health information and communication system Heilsuvera. One of the questions asked how often they used it for activities such as to communicate with doctors or other health professionals in relation to their health. In addition, they were asked about their use of the system to seek information about various health issues. Figure 4 presents the results.

Figure 4: Use of Heilsuvera to communicate and to seek information about health

Figure 4 shows that the participants in both age groups rarely used the system to communicate with doctors or other health professionals in relation to their own health, book appointments, view drug prescriptions, or send messages. Likewise, they rarely sought information about health through the system.

When the question about using the system to get information related to their own health through was analysed by sex, significant differences were found for both age groups (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Use of Heilsuvera to communicate and get information about own health

As Figure 5 shows that among those who are 60 to 67 years old, women were more likely to have used the system for communication in relation to their own health than men (p< 0.05). The results are reverse among those who are 68 years and older, with men being more likely to have used it than women (p< 0.01).

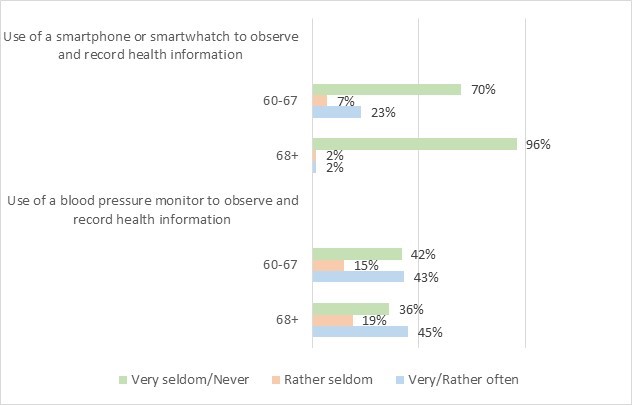

The participants were furthermore asked about their use of equipment, such as smartphones, smartwatches, and blood pressure monitors, to observe and record their health information. Figure 6 presents the results.

Figure 6: Use of apps in smartphones or smartwatches and use of blood pressure monitor

As can be seen in Figure 6, the majority of the participants had either never or very seldom used apps in smartphones or smartwatches to monitor or record their health information. The younger group was though more likely to have done so, while it was extremely rare for those who are 68 years or older. It was, on the other hand, more common for the participants to have used blood pressure monitors and the results show that there is only a slight difference across the age groups.

An examination by education revealed a significant difference for the use of blood pressure monitors in the age group 60-67 years old, see Figure 7.

Figure 7: Use of blood pressure monitors by 60- to 67-year-olds sorted by education

Figure 7 shows that, in the age group 60-67 years old, those who have secondary school education were most likely, and those with university education least likely, to have done so very seldom or never to have used blood pressure monitors very or rather often (p< 0.05).

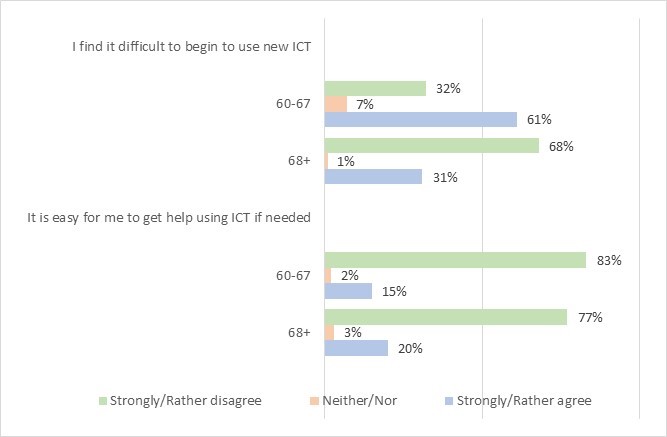

Results about respondents’ experience of taking new health information and communication technology into use, as well as how easy they found it to get help at using technology when they were in need for, are presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Difficulties at taking new technology in use and access to help at using technology

The results in Figure 8 reveal that the majority of participants in the younger age group agreed that it is difficult to take new health information and communication technology into use, while about third of them disagreed with it. The results were, however, reversed for the older group, with about one third of those who are 68 years or older agreeing that this is difficult and the majority disagreeing. The results about the participants possibilities to get help at using technology when needed, show that the great majority in both age groups did not consider it easy to get assistance.

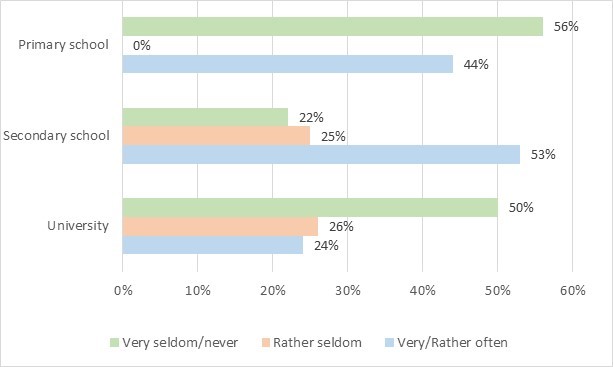

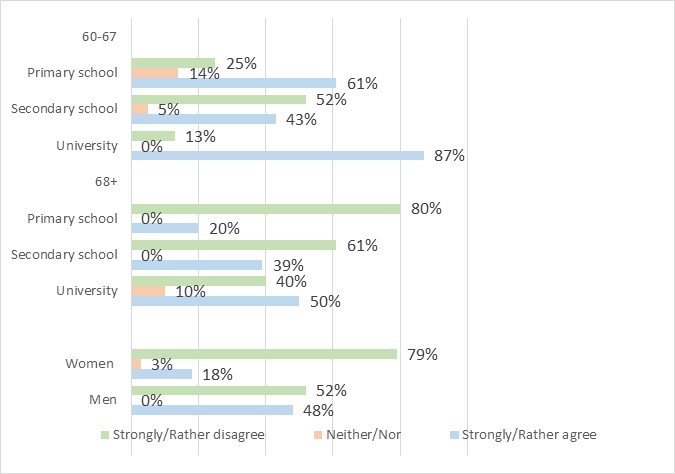

A further analysis of how difficult the participants found it to start using new health technology revealed significant differences by education for participants in both age groups, as well as by sex in the older group. The results are presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9: Difficulties at taking new technology in use

Figure 9 shows that, when asked if it is difficult to take new technology in use, there is not only a difference by education but also that the age groups differ considerably. In both groups, participants with university education were most likely to consider it difficult to start using new health information and communication technology. However, while the great majority of people with university education in the younger group agreed with this (p<0.05), only half of those in the older group did so (p<0.05). Furthermore, in the younger group, participants with secondary education were least likely to find this difficult, or about half of them (p<0.05), while in the older group those with primary school education were least likely to consider this difficult, or 80% (p<0.05).

In addition, although the majority of both women and men in the older age group disagreed that taking new technology in use is difficult, women were considerably more in disagreement with this than men (p<0.05) (see Figure 9).

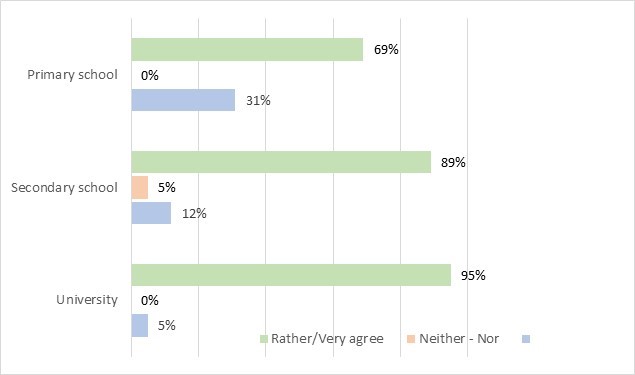

Analysis by background variables of the question about the participants possibilities of receiving help at using health technology revealed significant differences by education in the age group 60-67 years old. The results are presented in Figure 10.

Figure 10 Access to help at using technology in 60- to 67-year-olds sorted by education

As Figure 10 shows that, in the younger age group, the majority of participants in all educational group disagreed that it is easy to get help at using technology. Participants with university education were most likely to disagreed that it easy to get help at using technology, while those with primary school education were least likely to agree with it (p<0.05).

Discussion

Innovations in information technology have brought about major changes in healthcare. New possibilities of disseminating and accessing digital health information have emerged that give people the chance to better monitor their health and to, more actively, manage their healthy behaviour. The current study explored how people at the age of 60 years or older have adopted new health information and communication technology.

The results clearly demonstrated that the majority of participants in both age groups were motivated towards getting health information, including information in electronic health records. The results, however, varied by their age group. Those who are 60 to 67 years old were more likely to be both interested in health information and discuss it with others, as well as being considerably more likely to find it important to have access to their digital health records, than those who are 68 years and older. A similar trend for interest in digital health records was found by Huvila, et al. (2018).

However, despite being interested in health information, including information in digital form, the majority of participants in both age groups had not yet adopted new health technology. The results, revealed that the use of the health system Heilsuvera, was low, both for communicating with health professionals and getting information about their own health, and for seeking quality information about healthy living. Furthermore, the majority of them did not use health technology, although the younger group was somewhat more likely to have done so than the older group. The use of older technology to track and record their health information was, on the other hand, more common among both age groups.

Thus, the study findings indicate that well established means to gather information, which older adults are familiar with and have grown accustomed to use, may have more value for them than new technology. This corresponds with previous finding, that older adults prefer to choose information channels based on the practices that they have created over time, as well as their values and long-term perspectives (Rosales and Fernández-Ardèvol, 2019).

The low use of the system Heilsuvera is perhaps not surprising, considering the short time it had been in use at the time of the survey. It may always be expected that it takes time and effort to get people acquainted with new technology, and to get them engaged with using it. Furthermore, the data for the study was collected before the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic. Because the system has been employed to deliver information about the disease, it may be expected that this has attracted older adults’ attention and increased its use in general. The system can be seen as an opportunity for improvement in access to high quality health information, as well as for people to communicate with health professionals and receive various tailored information about their health. The value of the information itself is essential. The possibility to receive health information that are tailored to people’s own needs has been found to be a motivator that encourages older people to make an effort at using digital solutions (Jimison, et al., 2008; Loos, 2012). Hence, given time for people to become knowledgeable about the possibilities that the system offers, and provided that they will also get support at taking it into use, it can be concluded that the system makes promising possibilities for the future.

Taking new technologies in use can be demanding and older adults have been found to adopt it at a slower rate than those who are younger (Anderson and Perrin, 2017; Vorrink, et al., 2017). The majority of participants aged 60 to 67 years considered this difficult, while the results were reversed for those who are 68 years or older. This was unexpected and in contradiction to other results that show that the older group was somewhat less likely to have used apps for health information, as well as having expressed less interest in electronic health records. However, it is possible that the explanation to this may indeed be that, because they placed less emphasis on health information technology than those who are younger, they were also less prone to see it as a challenge to take it into use. In addition, although the majority in both age groups found it difficult to get help at using technology, the younger group claimed to have more problems with it than the older group. These are factors that can have a bearing on whether or not people are ready to make the effort of starting to use new health technology. Previous studies have for example reported that the ease of using new technology (Mendiola, et al., 2015; Tsai, et al., 2015), the confidence that people possess at being able to handle new technology and being able to get help at taking it into use, is of importance for older adults (Anderson and Perrin, 2017).

A further analysis of how the background variables interacted with the adoption of new technology revealed that people with university education found this more difficult than those with less education. Again, the reason may be that, since people with higher education are more likely to use information and communication technology (Hargittai and Dobransky,2017; Sabelli, 2020; Vroman, et al., 2015) they are also more likely to be aware of the difficulties connected to start using it. In the younger group, women were both more motivated towards health information and they used the new system Heilsuvera for communicating and seeking personal health information more than men, while in the older group the results were more mixed.

The overall study is limited by a total response rate of 42%. Although his may be considered satisfactory in a survey it raises the question whether or not those who answered the survey are giving a biased picture of those who did not respond. To compensate for this bias, the data were weighed by sex, age, place of residence and education, so that it corresponds with the distribution in the population. Thus, the findings may provide valuable information about the adoption of new health information and communication technology among older Icelanders.

Conclusion

For older adults to be able to make informed health decisions it is essential that they have access to quality information about their health history and healthy lifestyle. Health information and communication technology can open possibilities for them to retrieve more information relevant to their needs, as well as offering new ways to communicate with health professionals. Providing access to information, however, is of little value if it is not done in a way that meets the needs of the intended users. The results revealed that although the majority of the participants in both age groups were interested in health information, including information in digital form, they had not yet adopted new health information and communication technology. Furthermore, those who belong to the younger age group, in particular, did not perceive their possibilities for doing so to be good. Thus, the conclusion of the study is that it is not sufficient to make new information and communication technology available. For older adults to be ready to accept new technology and take it into use, they must be offered training at using it and technical support as needed.

The results from the study help to shed a light on older adult´s potentials to benefit from the development in health information and communication technology, and to identify their needs for support at using it. There is, however, a great deal more to learn about the topic. In particular, further research using more varied methods is needed, especially qualitative studies, which can explore more deeply why older people do not use new health technology and what kind of support they need and prefer to receive. This is particularly important because information and communication technology develops rapidly, which is a progress that can be expected to continue in the coming years.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the University of Iceland Research Fund.

About the author

Ágústa Pálsdóttir is a Professor in the Department of Information Science, School of Social Science, the University of Iceland. She received her bachelor’s degree in Library and Information Science and Master of Library and Information Science from the University of Iceland and PhD in Information Studies from the Department of Information Studies, Åbo Akademi University, Finland. She can be contacted at: agustap@hi.is

References

- Anderson, M. & Perrin, A. (2017). Tech adoption climbs among older adults. Pew Research Centre. https://www.pewinternet.org/2017/05/17/tech-adoption-climbs-among-older-adults/ (Internet Archive )

- Berger, K.S. (1994). The developing person through the lifespan (3 ed.). Worth Publishers.

- Bol, N., van Weert, J.C., Loos, E.F., Romano Bergstrom, J C., Bolle, S. & Smets, E.M. (2016). How are online health messages processed? using eye tracking to predict recall of information in younger and older adults. Journal of Health Communication, 21(4), 387-396. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1080327

- Brand, B., LaVenture, M., Lipshutz, J.A., Stephens, W.F. & Baker, E.L. (2018). The Information imperative for public health: a call to action to become informatics-savvy. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice, 24(6), 586-589.

- Directory of Health (2016). Heilsuvera: mínar heilbrigðisupplýsingar. https://www.landlaeknir.is/gaedi-og-eftirlit/heilbrigdisthjonusta/rafraen-sjukraskra/heilsuvera-minar-heilbrigdisupplysingar/ (Internet Archive)

- Eriksson-Backa, K. (2012). Finnish ‘silfer surfers’ and online health information. In K. Eriksson-Backa, A. Luoma, & E. Krook (Eds.), Exploring the Abyss of Inequalities. 4th Internation Conference on Well-Being in the Informatoin Society, WIS 2012, Turku, Finland, August 2012, Proceding. (pp. 138-149). Springer. (Communications in Computer and Information Science, 313).

- Hargittai, E. & Dobransky, K. (2017). Old dogs, new clicks: digital inequality in skills and uses among older adults. Canadian Journal of Communication, 42(2), 195-212. https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2017v42n2a3176

- Health Records Act nr. 55 April 27, 2009. https://www.government.is/media/velferdarraduneyti-media/media/acrobat-enskar_sidur/Health-Records-Act-No-55-2009-as-amended-2016.pdf (Internet Archive )

- Hoogendam, Y.Y., Lijn van der, F., Vernooij, M.W., Hofman, A., Niessen, W.J., Lugt van der, A., Ikram, M.A. & Geest van der, J.N. (2014). Older age relates to worsening of fine motor skills: a population-based study of middle-aged and elderly persons. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 6, 259. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4174769/ (Internet Archive )

- Huvila, I., Enwald, H., Eriksson-Backa, K., Hirvonen, N., Nguyen, H. & Scandurra, I. (2018). Anticipating ageing: older adults reading their medical records. Information Processing and Management, 54(3), 394–407.

- Jimison, H., Gorman, P., Woods, S., Nygren, P., Walker, M., Norris, S. & Hersh, W. (2008). Barriers and drivers of health information technology use for the elderly, chronically ill, and underserved. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 175. AHRQ Publication No. 09-E004). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19408968/ (Internet Archive)

- Kolotylo-Kulkarni, M, Seale, D.E, & LeRouge, C.M. (2021). Personal health information management among older adults: scoping review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(6), e25236. https://doi.org/10.2196/25236

- Lee, K., Hoti, K., Hughes, J.D & Emmerton, L. (2017). Dr Google is here to stay but health care professionals are still valued: an analysis of health care consumers’ internet navigation support preferences. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 9(6), e210 (2017). https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7489

- Loos, E. (2012). Senior citizens: digital imigrants in their own country? Observatorio, 6(1), 1-23.

- Loos, E.F. & Romano Bergstrom, J. (2014). Older adults. In J. Romano Bergstrom & A.J. Schall (Eds.), Eye Tracking in User Experience Design. (pp. 313-329). Elsevier.

- Lög um málefni aldraðra nr. 125/1999 [Act on the Affairs of the Elderly]. https://www.althingi.is/lagas/nuna/1999125.html (Internet Archive)

- Mendiola, M.F., Kalnicki, M. & Lindenauer, S. (2015). Valuable features in mobile health apps for patients and consumers: content analysis of apps and user ratings. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 3(2), e40. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4446515/ (Internet Archive)

- Norman, C. & Skinner, H. (2006). EHealth literacy: essential skills for consumer health in a networked world. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 8(2), e9. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.8.2.e9

- Ono, H. & Zavodny, M. (2007). Digital inequality: a five-country comparison using microdata. Social Science Research, 36(3), 1135-1155.

- Pálsdóttir, Á. (2008). Information behaviour, health self-efficacy beliefs and health behaviour in Icelanders´ everyday life. Information Research, 13(1) paper 334. http://InformationR.net/ir/13-1/paper334.html (Internet Archive)

- Pálsdóttir, Á. (2011a). Icelanders´ and trust in the Internet as a source of health and lifestyle information. Information Research, 16(1) paper 470. http://InformationR.net/ir/16-1/paper470.html (Internet Archive )

- Pálsdóttir, Á. (2011b). Opportunistic discovery of information by elderly Icelanders and their relatives. Information Research, 16(3) paper 485. http://InformationR.net/ir/16-3/paper485.html (Internet Archive )

- Pálsdóttir, Á. (2015). Senior citizens, media and information literacy and health information. Communications in Computer and Information Science, 552: 233-240.

- Piper, A.M., Campbell, R. & Hollan, J.D. (2010). Exploring the accessibility and appeal of surface computing for older adult health care support. In E. Mynatt, D. Schoner, G. Fitzpatrick, S. Hudson, K. Edwards & T. Rodden, (Eds.), CHI 2010: Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Atlanta, GA, USA, April 10–15 2010. (pp. 907–916). ACM.

- Resnik, D.B. (2007). Responsibility for health: personal, social, and environmental. Journal of Medical Health Ethics, 33(8), 444-445.

- Ries, W., Pöthiga, D. (1984). Chronological and biological age. Experimental Gerontology, 19(3), 211-216.

- Rosales, A. & Fernández-Ardèvol, M. (2019). Smartphone usage diversity among older people: movement disorder evaluation and deep brain stimulation systems. In S. Sayago (Ed.), Perspectives on Human-Computer Interaction Research with Older People (pp. 51–66). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-06076-3_4

- Sabelli, M. (2020). Old women and tablets: information behaviour in unfavourable contexts and social mediators. In Proceedings of ISIC, the Information Behaviour Conference, Pretoria, South Africa, 28-30 September 2020. Information Research, 25(4), paper isic2007. https://doi.org/10.47989/irisic2007

- Soederberg Miller, L.M. & Bell, R.A. (2012). Online health information seeking: the influence of age, information trustworthiness, and search challenges. Journal of Aging and Health, 24(3), 525-541.

- Statistics Iceland. (2014). Computer and internet usage in Iceland and other European countries 2013. Statistical Series: Tourism, Transport and IT 99. https://hagstofan.s3.amazonaws.com/media/public/6210b1e3-cd70-4a7b-8bab-dc957243dc4c/pub_doc_NVGSTvv.pdf (Internet Archive )

- Tapuria, A., Porat, T., Kalra, D., Dsouza, G., Xiaohui, S. & Curcin, V. (2021) Impact of patient access to their electronic health record: systematic review. Informatics for Health and Social Care, 46(2), 194-206. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538157.2021.1879810

- Thane, P. (1989). History and the sociology of ageing. Social History of Medicine, 2(1), 93-96.

- Todd, M.M., Tonatiuh, M., Battula, M., Davoudi, A., Kheirkhahan, M., Young, M.E., Weber, E., Fillingim, R.B. & Rashidi, P. (2019). Perception of older adults toward smartwatch technology for assessing pain and related patient-reported outcomes: pilot study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 7(3), e10044. https://doi.org/10.2196/10044

- Tsai, H.S., Taiwan, H., Shillair, R., Cotton, S.R., Winstead, V. & Yost, E. (2015). Getting grandma online: are tablets the answer for increasing digital inclusion for older adults in the U.S.?. Educational Gerontology, 41, 695–709.

- United Nations. (2013). World population aging. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2013.pdf (Internet Archive)

- Vorrink, S.N.W., Antonietti, A.M.G.E.F., Kort, H.S.M., Troosters, T., Zanen, P. & Lammers, J-W.J. (2017). Technology use by older adults in the Netherlands and its associations with demographics and health outcomes. Assistive Technology, 29(4), 188-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2016.1219885

- Vroman, K.G., Arthanat, S. & Catherine Lysack, C. (2015). ‘‘Who over 65 is online?’’ older adults’ dispositions toward information communication technology. Computers in Human Behavior, 43, 156-166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.10.018

- Wikler, D. (2002). Personal and social responsibility for health. Ethics & International Affairs, 16(2), 47-55.

- World Health Organization. (2007). Global age friendly cities: a guide. WHO. http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Global_age_friendly_cities_Guide_English.pdf (Internet Archive)