‘Confused, scared, hopeless, unsure.’ Teens looking for information about COVID-19

Leanne Bowler

Introduction. Presents findings from an online questionnaire investigating teens’ information-seeking about COVID-19.

Method. Online questionnaire completed by 26 teens, ages 15 to 19 years, living in Brooklyn, New York, in June 2020. Responses include quantitative data (ranking and checklists) and qualitative data (free writing).

Analysis. The questionnaire explored information themes in relation to COVID-19, such as information sources and platforms, credibility and disinformation, teens’ roles in information intermediation, affective aspects of their information behaviour, as well as what would have helped teens find COVID-19 information.

Results. Teens experienced anxiety as they looked for reliable information about COVID-19. They served as their family’s language brokers and technology experts, taking on the responsibilities of information intermediator. Teens used social media platforms and legacy media as information sources. Nevertheless, teens indicated a wish for institutional support and guidance from governments (municipal, state, federal) and schools. Libraries were not an information source.

Conclusions. The results of this study have implications for research into teen mental health in relation to the COVID-19 global pandemic, as well as reframing the meaning of ‘everyday life information seeking’ during a time of crisis, when everyday life is not normal.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irisic2220

Introduction

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared a global COVID-19 pandemic. New York State issued stay-at-home orders on March 22, which were extended until May 15, 2020 (New York State, 2020). Schools were closed and young people began several months of online learning. By April 9, 2020, New York City had the most COVID-19 cases in the world (Millman, 2020) and, for New Yorkers, constant sirens became the soundtrack of the health crisis (Associated Press, 2020). By June 2020 New York City had started on its path to re-opening, but the previous three months were still fresh in the memories of most, including the 26 teens from Brooklyn who participated in this study.

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted many parts of adolescents’ lives (De Figueiredo, et al., 2021) and uncertain times may trigger the need to seek information. Indeed, data from Google Trends has shown an increase in searches for information about the coronavirus (Mangono, et al., 2021). A study published by CommonSense Media investigated the ways that 1500 teens (age 14 to 22) have coped with the pandemic, one of which is to seek information about COVID-19 (Rideout, et al., 2021). The study found that more than eight in ten (85%) young people have gone online to look for health information on a wide variety of topics (6). Of those health topics, among the most frequently researched has been COVID-19 (58%). Young people also reported that social media has played an important role in keeping them informed about current events during the pandemic (34%) and learning how to protect themselves against the virus (31%). This paper continues this exploration into the information-seeking behaviour of teens, as related to COVID-19. It paints a picture, albeit preliminary, of the ways that teens navigated and coped with an emerging and complex information ecosystem during the early months of the global pandemic.

Methods

An online questionnaire was completed in June 2020 by 26 teens, ages 15 to 19 years, living in the borough of Brooklyn in New York City. Fifteen identified as female; eleven as male. They were recruited through an invitation from the Brooklyn Public Library, to teens who had previously registered in programs at the library, thus assuring that participants were teens living in Brooklyn. The questionnaire was sent to 35 teens and completed by 26, a response rate of 74%. Participants were compensated with a $10 gift certificate from Starbucks.

| Age | 15 years | 16 years | 17 years | 18 years | 19 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (Total=26) | 3 | 12 | 6 | 4 | 1 |

The questionnaire was created with Google Forms and sent to participants by email in early June 2020. All questionnaires were completed within a week. The questionnaire included 16 questions written in English and responses were a mix of quantitative data (ranking and checklists) and qualitative data (free writing). The questions reflected information themes determined a priori, such as information sources and platforms, credibility and disinformation, teens’ roles in information intermediation, affective aspects of their information behaviour, and thoughts on what might have helped them find information about COVID-19. Analysis and subsequent results address these themes.

It should be noted that since COVID-19 touched all aspects of teens’ lives, from school to mental health, the questionnaire did not define ’information about COVID-19’as a concept specific to bio-medical or health information. The open-ended questions in particular allowed for a broader window on COVID-19 information – living in a pandemic having become, in a sense, a ’way of life’ (Savolainen, 1995). Taking an everyday life approach allowed for a picture to emerge of what COVID-19 actually meant to teens: school closures, lock-down, death rates, sterilization techniques, directives for small businesses, and so on – far beyond what we might normally call ‘health information’.

Results

Information sources and platforms

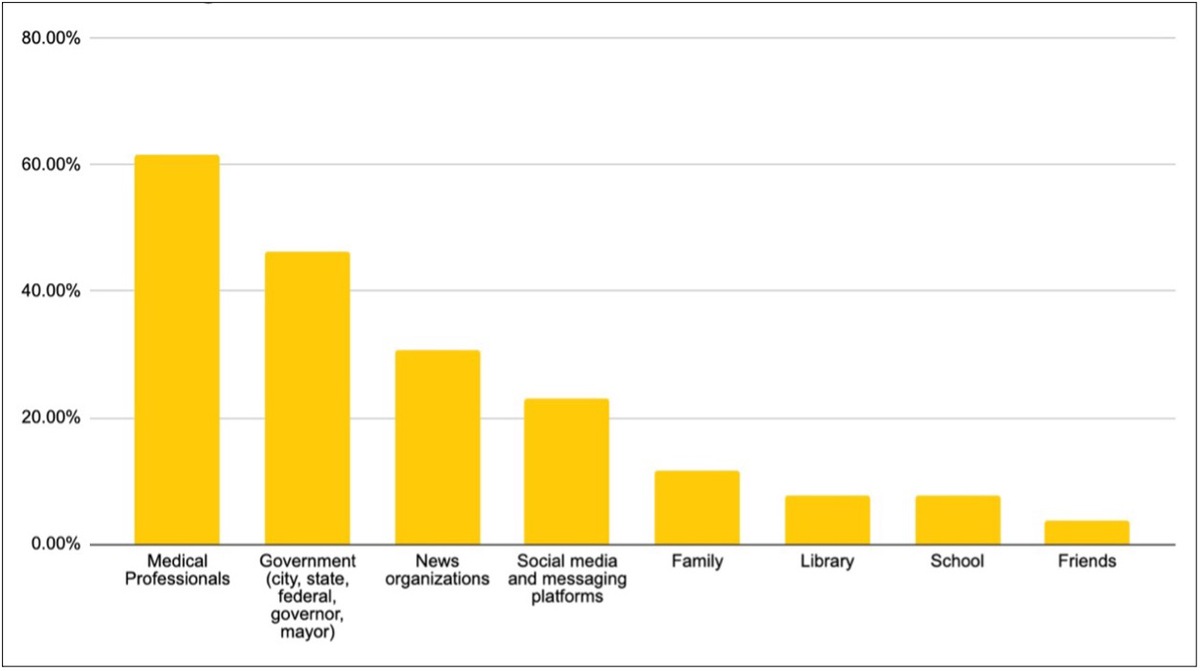

Teens were asked what their preferred sources for information about COVID-19 were. Since the pandemic touched all aspects of life, the scope of information sources was broad (See Table 1 below. Note that categories may overlap). Teens indicated a preference for information from official, government sources (municipal, state, federal) as well as political leaders (Governor and Mayor). The library, however trustworthy, was not an ideal information source for these teens, one suggesting that because the library building was closed, they would therefore have no access to information – the library website and digital resources not considered. Schools, as well, were low on the scale of preferred information sources. Comments as to what might have helped teens find COVID-19 information suggest that schools could have played a more active role in the provision of COVID-19 information:

I think school could’ve pushed more towards giving students like me access to valid and reliable info. A lot of kids these days will believe anything on the internet, so it would’ve helped if they directed us to sources that were accountable. (Female, 17 years)

Legacy media such as the New York Times was mentioned by three teens in their written responses to questions regarding helpful and preferred information sources. According to one teen, this was only because the New York Times - normally a subscription based service - had allowed free access to COVID-19 information on its web site. Such access proved invaluable, as one teen explained:

I do not come from a community or family who listen or are aware of any news whatsoever (we do not have a tv at home) so my only sources are the New York Times and other online sources that are easily accessible. (Male, 18 years)

People, not just documents and data, can be an information source and 60% of teens identified medical professionals as their most preferred source. This could include medical professionals interviewed on television, viewed on YouTube, or cited in news articles. Some caution should be applied when interpreting this response. The people who teens thought they should trust may not be the people that they actually used as information sources. Written comments suggest a different picture. For example, one teen who identified medical professionals as their preferred information source, also identified John Oliver, the host of the Daily Show (a comedy show) as a trusted source (Male, 15). Interestingly, among the least preferred people for most teens were friends and family, even though these would have been the people that teens were in contact with the most during the stay-at-home period. This seemingly runs counter to the assumption that information seekers will look to their friends and family first before seeking information sources from mass media (which today includes social media) because it is just easier (Dervin, 1983).

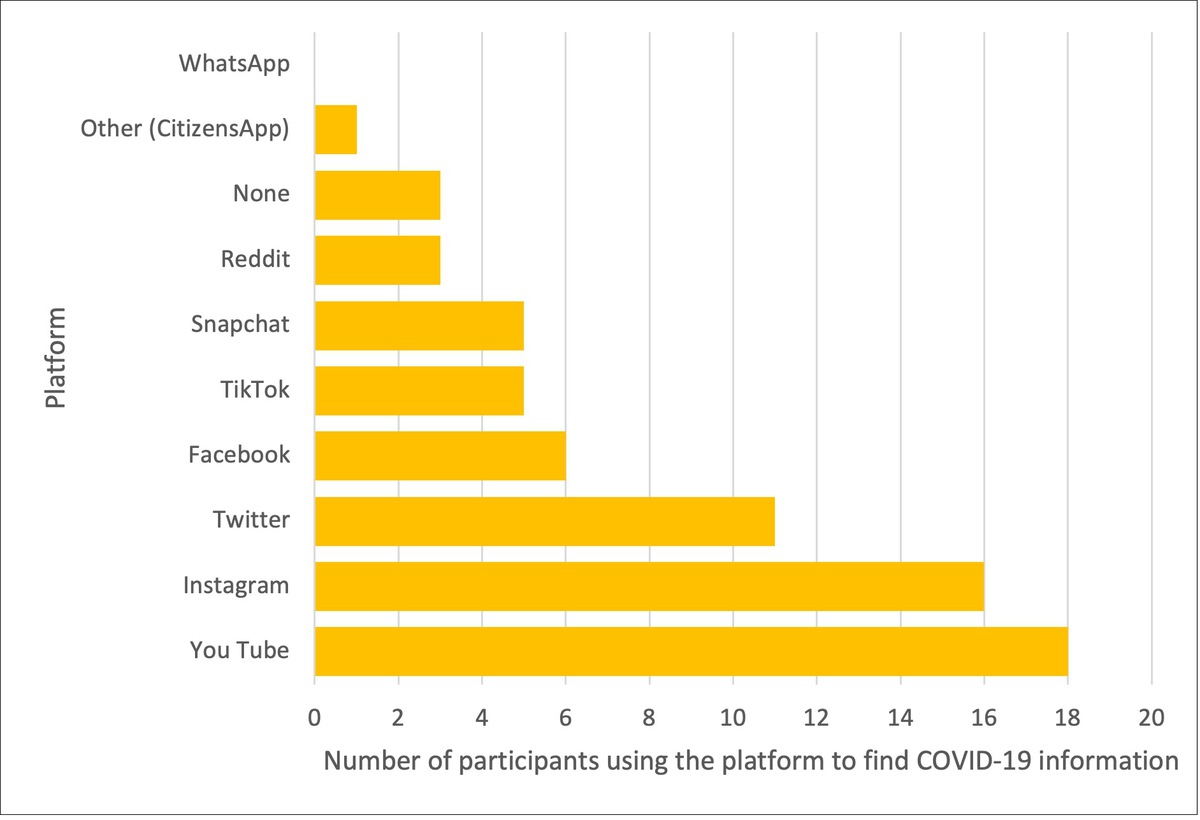

Although not a preferred information source, social media and messaging platforms did play a role in the teens’ information seeking, reinforcing Rideout and Robb’s (2021) finding that social media has helped teens stay informed during the pandemic. Asked ‘Which social media platforms do you use to find information about COVID-19’ three teens said they did not use any social media platforms, leaving 23 who did. Teens identified YouTube, Instagram, and then Twitter as their go-to platforms. There is no indication how much these platforms were used to find information about COVID-19, only that they were used. (Figure 2 below displays teen’s reported use of social media platforms).

Figure 2: Social media platforms used to find information about COVID-19 (26 responses)

Credibility, disinformation and discord

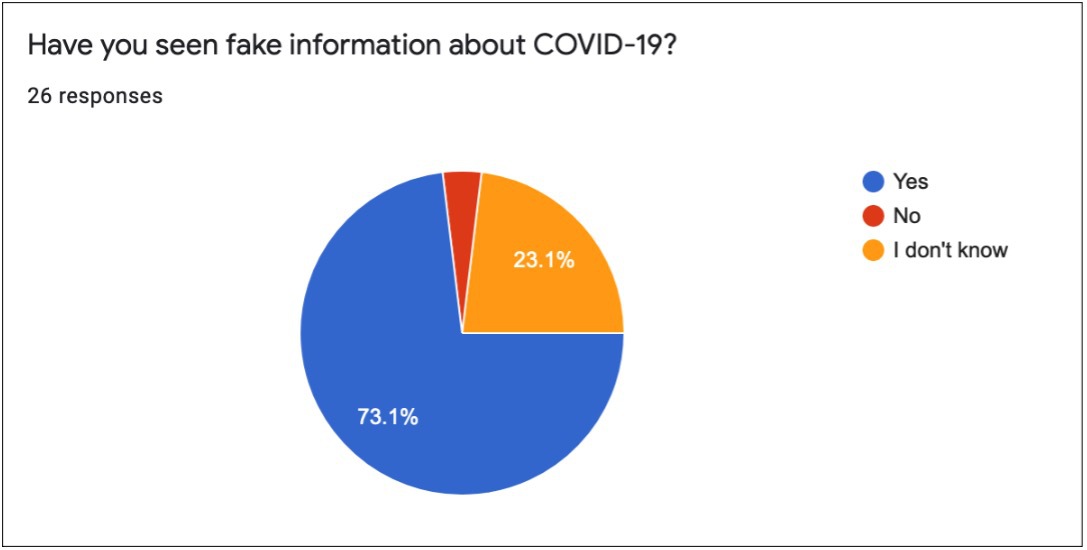

The teens in this study were asked a simple question about the quality of COVID-19 information, using a colloquial term for disinformation - fake information: ‘Did you see fake information about COVID-19’ Nineteen said yes, six reported ‘I don’t know’ and one said no. (Figure 3 below shows the percentages). Arguably there is an assumption here that teens have the capacity to ascertain credible and reliable information. The questionnaire allowed them to provide evidence of so-called fake news and every teen who answered yes did so, their commentaries demonstrating an understanding of source credibility, the ways that social media amplifies disinformation, and their keen awareness of the broader ideological and information wars. Overall, the teens revealed a deeply held scepticism of social media platforms as a medium for reliable, trustworthy information about COVID-19, even as they accessed and used this technology.

There was a lot of fake information related to how masks wouldn't help slow the spread of the coronavirus and how it was actually detrimental to your health. I typically saw these things on Facebook... I knew it was fake information because there was no scientific backing to it and most people would just talk about their constitutional rights about not having to wear a mask. (Male, 16 years)

Perhaps one reason for this skepticism was due to their frustration over the politicization of COVID-19. Four teens referred to President Trump as a source for disinformation, while others noted the difficulty distinguishing between fact and opinion in the highly charged political debates around COVID-19.

The president is doling out false information which makes it seem like COVID-19 is a controversial, political topic, when in fact it is a matter of life and death and people still think there should be a debate over it. (Female, 18 years)

With the heavy politicization of the issue it was difficult at times to differentiate between political banter and hard data. (Male, 18 years)

Figure 3: Fake information about COVID-19

Teens’ roles as information intermediators

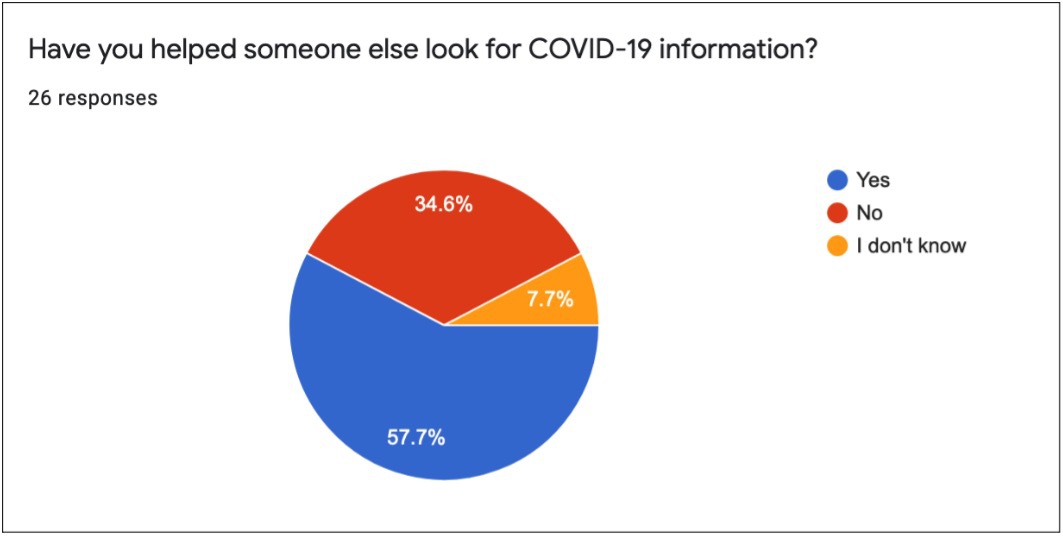

Many teens in this study served as information intermediators for their family and friends – a heavy burden to shoulder in a global pandemic. When asked if they had ever helped someone else look for COVID-19 information, 15 answered yes (57%), nine said no (34%) and two didn’t know (7.6%). (Figure 4 below shows the percentages). Twelve reported helping their parents or grandparents find information and, if we extend the inner social circle to include friends, a total of 15 teens sought COVID-19 information on behalf of others.

Figure 4: Information mediation

Intermediaries act as information agents for others, fulfilling three information services: information need recognition, information sourcing, and information comprehension (Buchanan and Ruthven, 2019). Although this role is typically associated with librarians and educators, it is also one that non-professionals play in everyday life, including youth in stressful situations (Fisher and Yafi, 2018). They do this for many reasons. For example, young people often serve as language brokers, translating and interpreting for family, community, and peers who don’t speak the local language (Crafter and Iqbal, 2021), as was the case with this teen:

My parents work in a restaurant and COVID-19 really took a toll on their business. Since they don't speak English that well, whenever they need more information on how quickly the virus is spreading, what the city reopening phases are, regulations that businesses have to abide by in light of social distancing, I'm always the one that has to help them research this information. (Female, 18 years)

Another teen dealt with gaps in both language and digital skills, explaining that she helped her family because ‘they are not familiar with technology and are not native speakers and wanted to find out more about COVID-19’ (Female, 16 years).

One imagines that in New York City, home to 3 million immigrants (36 % of the city’s population), speaking over 200 languages, this scenario has played out time and again for teens throughout the pandemic (New York City, 2020). Translational roles go beyond language when we consider that an intermediary has to interpret the information needs of others as well as the meaning of their questions, a phenomenon identified as the ‘imposed query’ (Gross, 1995).

Teens also served as intermediaries due to their technical prowess, as was the case with this teen who reported that his family does ‘not have access to any sort of outside news or information about the disease due to a lack of participation in TV and the interne’ (Male, 18). Some teens became educators in digital and information literacy, one showing her mother how to use Citizen App to find out how many people were being affected by COVID-19 in New York City (Female, 16 years). Another reported that her mother’s lack of information literacy skills drew her into WhatsApp chats with false information:

After hearing from her these absurd rumors and theories that non-qualified people were spreading, I told her about the importance of reliable, accountable, and valid resources. I gave her access to things like the mayors and governors accounts so she was receiving accurate information’. (Female, 17 years)

The essence of intermediation is a trusting relationship (Buchanan and Ruthven, 2019), suggesting socio-emotional ties to the person or people for whom one intermediates and therefore, aspects of emotional labour. Imagine the emotional cost for this teen looking for COVID-19 information for her sick grandmother.

I helped my grandparents because my grandmother was getting increasingly sick (and was eventually hospitalized with COVID-19 though we didn't know if she had it at the time) and I was concerned by reports that specific pain killers could worsen the infection so I did research into which drugs would be safe to use. I recommended that she not take Ibuprofen because research indicated it could worsen or extend COVID-19 symptoms. (Female, 17 years)

Affective aspects of teen’s information behaviour

High rates of anxiety and depression have been reported among children and youth during the pandemic (Courtney, et al., 2020; Office of the Surgeon General, 2021b). Teens are in a developmental stage particularly sensitive to environmental stress and the COVID-19 pandemic may have elevated the risks. Given this situation, the study looked to the teens’ feelings as they sought information about COVID-19. They were specifically asked, ‘How did you feel when you were looking for information about COVID-19’ ? An analysis of responses found emotion-laden words used to describe feelings related to COVID-19 information (e.g. anxious, confused, frightened, hopeless, nervous, overwhelmed, sad, scared, shocked, stressed, uncertain, worried…), suggesting that the teens in this study experienced anxiety. This, coupled with their frustration over the politicization of COVID-19, as mentioned above, created a highly charged information environment in which to navigate during a global pandemic. The voice of teens gives us a window onto the intense feelings they experienced.

I felt super stressed because I wasn’t exactly sure where to look and what exactly qualified as proper information. (Female, 16 years)

I was overwhelmed because there was so much information about covid. (Male, 16 years)

Confused, scared, hopeless, unsure. Words like antibody testing and vaccines were thrown around but no one ever really had a definitive answer or timeline of when these cures would come out. (Female, 18 years)

Nevertheless, as the pandemic wore on, almost a third of the teens said they were navigating COVID-19 information more adeptly than they had at the beginning and finding reliable sources (and perhaps, more information sources became available to the public).

At first there was a lot of information all coming at me at once so I was a little bit overwhelmed, but now I have been able to choose my favorite websites (my favorite is Johns Hopkins) And I do most of my research there. (Male, 16 years)

What might have helped these teens find information about COVID-19?

Asked ‘What would have helped you find information about COVID-19’, a third of the teens wished there was a centralized information source or tool where they could find verified, reliable information about the pandemic. Some felt it would be fine if social media platforms had a section dedicated to such a tool (and some eventually did), but most placed responsibility for this centralized system on institutions such as schools or government. Underlying this may be a request for trusted adults and the institutions that serve young people to step into the fray. One teen mentioned that adults should provide him with ‘a list of sources or articles that are reliable for me to read up on’ (Male, 15 years). At least three teens looked to their school - the institution closest to them – to play a more active role in the provision of COVID-19 information. Luckily one teen said his teacher pointed him in the direction of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the New York State’s Department of Health (Male, 16 years) – an example of a teacher serving as an information intermediary. Even though these teens had a relationship with the public library, at no point did any teen suggest that libraries could be the centralized information clearinghouse that they sought.

Conclusion

This study offers a snapshot of how a group of teens navigated the early days of the COVID -19 pandemic. Results point to a need for deeper exploration into teens’ information-seeking behaviour, feelings, and motivations during times of crisis. The data show that teens did engage with COVID-19 information through a variety of pathways and platforms. It also shows that from the beginning of the pandemic, teens were not insulated from the broader political discourse surrounding COVID-19 and were well aware of the emerging crisis of disinformation, a society-wide problem that has been called ‘an urgent threat’ (Office of the Surgeon General, 2021a). Nor were the teens in this study passive receivers of information. Rather, many in this study were active seekers on behalf of others. Did looking for information for others provide young people with in an altruistic mission to help get them through the pandemic or cause anxiety?

There are other questions that require more study. For example, some teens suggested that looking for information about COVID-19 was a coping mechanism, empowering them to monitor the situation and avoid illness (Miller, 1987; Folkman, 1984). If this was the case, how did this behaviour work out for them? Was it helpful? We might also ask if there were other mechanisms at work. Were teens seeking information for the sake of learning, or did the novelty of the situation simply interest them, in the same way that many people see the news as entertainment (Holmov, 1982)?

Notwithstanding the fact that many teens willingly looked for COVID-19 information for themselves and for others, they still expressed a sense of being overwhelmed. Did social media contribute to this sense of unease, in pushing streams of information, perhaps uninvited, toward young people? At the same time, one wonders what role the public library could have played in disseminating information about COVID-19 (or at least, pointing the way to resources), had the teens thought to use this trusted community resource. As noted above, no teen considered the library web site and digital resources in the library’s collection as an option.

The experiences shared by the teens who participated in this study presage many of the ongoing debates and concerns around COVID-19 information two years later. During times of crisis, teens need both informational and emotional support, including recognition that many of them take on the burdens of information intermediation on behalf of their families and friends. Results of this study have implications for research into teen mental health in relation to the COVID-19 global pandemic, as well as a reframing of what Savolainen’s ‘everyday life information seeking’ (1995, 2005) looks like during a time of crisis, when everyday life is not normal.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the teens who participated in this research. Their contributions are invaluable. Many thanks as well to Derek Frisicchio and the librarians at the Brooklyn Public Library for their contributions to the project.

About the author

Leanne Bowler is a Professor at the School of Information, Pratt Institute, in New York City, USA. Her research and teaching focuses on young peoples' critical interactions with information and data, their technology practices, STEM learning, and how family, teachers, and out-of-school organizations such as libraries and museums can support young people's competencies in a socio-technical world. She can be contacted at lbowler@pratt.edu.

References

- Associated Press. (2020, March 30). Sirens a constant as NYC nears 700 coronavirus deaths. FOX 5 New York. https://www.fox5ny.com/news/sirens-a-constant-as-nyc-nears-700-coronavirus-deaths (Internet Archive)

- Buchanan, S., Jardine, C., & Ruthven, I. (2019). Information behaviors in disadvantaged and dependent circumstances and the role of information intermediaries. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 70(2), 117-129. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24110

- Courtney, D., Watson, P. Battaglia, M., Mulsant, B., & Szatmari, P. (2020). COVID-19 Impacts on Child and Youth Anxiety and Depression: Challenges and Opportunities. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry / La Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 65(10), 688-691. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0706743720935646

- Crafter, S., & Iqbal, H. (2021). Child language brokering as a family care practice: Reframing the ‘parentified child’ debate. Children & Society.

- De Figueiredo, C. S., Sandre, P. C., Portugal, L., Mázala-de-Oliveira, T., da Silva Chagas, L., Raony, Í., Ferreira, E. S., Giestal-de-Araujo, E., Dos Santos, A. A., & Bomfim, P. O. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents' mental health: Biological, environmental, and social factors. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry, 106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110171

- Dervin, B. (1983). More will be less unless: The scientific humanization of information systems. National Forum, 63(3), 25-27. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-01-2021-373

- Drouin, M., McDaniel, B. T., Pater, J., & Toscos, T. (2020). How parents and their children used social media and technology at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and associations with anxiety. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(11), 727-736. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0284

- Gross, M. (1995). The imposed query. RQ, 35(2), 236-243. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20862879 (Internet Archive)

- Fisher, K.E. & Yafi, E. (2018). Syrian youth in Za’atari Refugee Camp as ICT wayfarers: An exploratory study using LEGO and storytelling. COMPASS ’18: Proceedings of the 1st ACM SIGCAS Conference on Computing and Sustainable Societies, June 2018, Article 13, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1145/3209811.3209873

- Folkman, S. (1984). Personal control and stress and coping processes: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(4), 839-852. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.839

- Gunderson, J., Mitchell, D., Reid, K., & Jordan, M. (2021). Peer Reviewed: COVID-19 Information-Seeking and Prevention Behaviors in Florida, April 2020. Preventing Chronic Disease, 18. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd18.200575

- Holmov, P. (1982). Motivation for reading different context domains. Communication Research, 9(2), 314-320. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F009365082009002006

- Jalilian, M., Kakaei, H., Nourmoradi, H., Bakhtiyari, S., Mazloomi, S., & Mirzaei, A. (2021). Health Information Seeking Behaviors Related to COVID-19 Among Young People: An Online Survey. International Journal of High Risk Behaviors and Addiction, 10(1). https://dx.doi.org/10.5812/ijhrba.105863

- Mangono, T., Smittenaar, P., Caplan, Y., Huang, V. S., Sutermaster, S., Kemp, H., & Sgaier, S. K. (2021). Information-Seeking Patterns During the COVID-19 Pandemic Across the United States: Longitudinal Analysis of Google Trends Data. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(5). https://doi.org/10.2196/22933

- Miller, S. (1987). Monitoring and blunting: Validation of a questionnaire to assess styles of information seeking under threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(2), 345-353. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.2.345

- Millman, J. (2020). New York Has Most COVID-19 Cases in World, Deaths Top 7k as Curve Starts to Flatten. https://www.nbcnewyork.com/news/local/new-york-has-most-covid-19-cases-in-globe-cuomo-warns-of-more-death-even-as-curve-flattens/2366721/ 4NewYork. (Internet Archive)

- New York City. (2020). State of our Immigrant City. Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs Annual Report. New York City, New York. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/immigrants/downloads/pdf/MOIA-Annual-Report-for-2020.pdf (Internet Archive)

- New York State. (2020). Governor Cuomo Issues Guidance on Essential Services Under The “New York State on PAUSE” Executive Order. New York State. https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-issues-guidance-essential-services-under-new-york-state-pause-executive-order (Internet Archive)

- Office of the Surgeon General. (2021a). Confronting Health Misinformation: The US Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Healthy Information Environment. Office of the Surgeon General. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-misinformation-advisory.pdf (Internet Archive)

- Office of the Surgeon General (2021b). U.S. Surgeon General Issues Advisory on Youth Mental Health Crisis Further Exposed by COVID-19 Pandemic. Office of the Surgeon General. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2021/12/07/us-surgeon-general-issues-advisory-on-youth-mental-health-crisis-further-exposed-by-covid-19-pandemic.html (Internet Archive)

- Rideout, V., Fox, S., Peebles, A., & Robb, M. B. (2021). Coping with COVID-19: How young people use digital media to manage their mental health. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense and Hopelab. https://www.chcf.org/publication/coping-covid-19-young-people-digital-media-manage-mental-health/ (Internet Archive)

- Savolainen, R. (1995). Everyday life information seeking: Approaching information seeking in the context of “way of life”. Library and Information Science Research, 17(3), 259-294. https://doi.org/10.1016/0740-8188(95)90048-9

- Savolainen, R. (2005). Everyday life information seeking. In K. E. Fisher, S. Erdelez, & L. E. F., McKenchie (Eds.), Theories of Information Behavior (pp. 143-149). Medford, NJ: Information Today, Inc.