Informed, active, empowered: research into workers’ information literacy in the context of rights at work

Dijana Šobota and Sonja Špiranec

Introduction. The paper reports the findings of research into information literacy in the context of workers’ rights in Croatia. It analyses workers’ information behaviour and the ways in which they obtain and use information to seek the protection of their rights. The paper aims to map out a new research framework for information literacy situated at the junction of workplace and critical information literacy.

Method. Quantitative data were collected by an online questionnaire with 50 primarily close-ended questions on a nationally representative sample of N=500 employed workers.

Analysis. Quantitative analysis was carried out on the data employing SPSS and Excel.

Results. Higher levels of being informed and information competences, and active information behaviour, lead to less frequent violations of workers’ rights and to a greater readiness to seek the protection of, and fight for, those rights.

Conclusions. The findings confirm the importance of information literacy in the prevention of violations of rights and in mounting effective opposition when these occur, and in the empowerment of workers to seek their protection and improvement. The results allow further delineation of the information literacy practices of workers. The paper brings the first attempt to look into the prospect of the critical workplace information literacy construct.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irisic2239

Introduction

From the outset and the coinage of the term by Zurkowski (1974) information literacy has been conceived and promoted as vital for well-being and development, with the skills at the core of the concept termed ‘survival skills in the Information Age’ (ALA, 1989). The key documents in library and information science, such as the Prague Declaration (2003) and Alexandria Proclamation (2005), endorse information literacy as a basic human right and consider the ideas of social justice, equality and democracy as the basis of information literacy. However, despite their essentially humanist values, they fail to acknowledge the vested interests of neoliberal philosophy (or, rather, they completely and uncritically embrace it (Seale, 2013, p. 47)), thwarting attempts by citizens to assert their human rights. This disjuncture is evident also in the almost complete disregard for workers’ rights, as a part of human rights, in the empirical and theoretical considerations of information literacy, including critical information literacy, despite their obvious connections. The paper, and the research reported, do not address the reasons for this disregard, but they do aim to address this dearth by bringing workers’ rights into the discourse. Specifically, they aim to comprehend the role and value of information literacy in the context of workers’ rights by exploring workers’ information behaviour and their awareness of information and its sources in empowering them in the pursuit of their rights at work.

The explored concepts of information literacy and information behaviour are closely related. Indeed, information behaviour – people’s information practices of information seeking and use – is the kernel of many definitions of information literacy, e.g. ‘information literacy is the adoption of appropriate information behaviour’ (Johnston and Weber, 2003, p. 336). In the workplace context, numerous studies (for instance Byström and Järvelin, 1995; Leckie, et al., 1996; Cheuk, 1998; White, et al., 2008) have focused on the goal-directed, cognitive and affective aspects of information behaviour, i.e. on the microlevel of individual professionals and their interaction with information, without paying much attention to the contextual aspects. However, and especially in complex contexts such as workers’ rights, information literacy is broader than information behaviour and the perspective of the individual. Rather, it is a holistic and situated experience (Lloyd, 2007) which acknowledges not only the individual’s experience of information but also the social and cultural context that influences all practice. To focus only on information behaviour would mean to fail to acknowledge that workers experience information about their rights in consort with other factors, and that their consciousness of and critical action in relation to information and those factors affect their success in attempting to assert their rights, as this research attempts to prove.

Developing critical consciousness is a central tenet of critical information literacy. It is fundamentally concerned with social justice and human emancipation: it endeavours to empower people to question, through their abilities, society’s dominant values and beliefs (Cope, 2010, p. 19), and to take control of their lives by developing critical consciousness (Elmborg, 2006, p. 193).

Information literacy conceived in such a way is therefore of particular relevance in the context of workers’ rights: workers not only need the abilities to access, evaluate and use information about their rights but they need to be empowered to recognise and take action against social injustices, i.e. the violation of their rights. In that sense, critical consciousness and information literacy can be considered of existential importance: the failure to make well-informed choices and decisions dialogically, through awareness of information sources and the power of information, on top of the failure to benefit from that power, can have a decisive impact on individual workers’ rights, the world of work at large and social justice in general.

A logical conceptual setting and theoretical framework for researching information literacy in the context of workers’ rights is workplace information literacy since the notion of rights is a dimension of the world of work and the need for it emanates mostly from the workplace. However, concepts of workplace information literacy pertain to aspects relevant to employers and the organisation – business outcomes such as innovation, productivity and competitiveness – while the dimension of workers’ rights has been left out of the narrative.

On the theoretical level, this contribution aims to fill the knowledge gap in workers’ rights within the workplace information literacy discourse, and thereby carve out critical dimensions in the concept of workplace information literacy. With this, the paper aims to start a conversation about critical workplace information literacy by bridging hitherto separate theoretical frameworks – critical information literacy and workplace information literacy.

Theoretical framework

There are profound paradigmatic and ideological differences in understanding information literacy. This, in particular, pertains to a differentiation between the reductionist skills approach and the holistic, social context approach to information literacy, and to an understanding of its value and role. The latter has been promoted by the ACRL guiding document Framework for information literacy for higher education (ACRL, 2016), which departs from the standards-based skills approach, incorporates critical perspectives and recasts information literacy as part of a ‘complex ecosystem’, akin to Lloyd’s information landscape construct (2006; 2010). However, the Framework has also been criticized for retaining the sensibility of a set of standards (Seale, 2016; Drabinski and Sitar, 2016), its ideological underpinnings as (neo)liberal and antithetical to critical information literacy it means to instantiate (Seale, 2016), and as being insufficiently explicit in connecting information literacy to social justice and civic engagement (Battista, et al., 2016; Saunders, 2016).

This paper subscribes to a holistic understanding of information literacy, which encompasses an emphasis on a critical reflection on the nature of information and its social context (Shapiro and Hughes, 1996); critical awareness of the importance of the wise and ethical use of information (Johnston and Webber, 2003); and an understanding that information is socially produced and distributed, and can therefore be accessed primarily through social context and social relationships (Lloyd, 2006). This socioculturally-anchored paradigmatic understanding of information literacy is reflected in different theoretical frameworks and the different applied subdomains of information literacy research, including workplace information literacy and critical information literacy. Both are logical starting points for researching the notion of workers’ rights.

Although information literacy was predominantly applied to and studied in the context of formal education, the last two decades have brought about a rich knowledge base derived from information literacy research in the workplace context (for an overview, see e.g. Lloyd, 2013; Sayyad Abdi and Bruce, 2015).

Despite different interpretations of the notion of workplace information literacy across scholarly literature (Widén, et al., 2021), there is a common approach that focuses on the role of information-handling skills in relation to work practices and goals. The uniqueness of this specific instance of information literacy is defined by the workplace context (ibid.), which is often described as messy, complex and distributed through a range of entwined practices that contribute to the collective performance of work (Lloyd, 2011). When conceptualising workplace information literacy, it is not enough to focus on the worker’s own context or personal information landscape but also the larger information landscape of an organisation (Lloyd, 2010), which requires approaches that capture the social dimensions of workplaces (Lloyd, 2017).

Workers’ rights are inseparable from the workplace as they are determined and influenced by rules, contractual relations, agreements and the power dynamics of that workplace in which both the personal and the collective, i.e. the social dimensions have a role to play. The workplace has also historically been the central site of resistance where workers organised as collective agents of struggle for their interests. Workers’ rights, however, go beyond workplace level and are far broader in scope as they encompass an array of rights which are laid out in sources at sectoral, national and international level, and which are more general in nature, comprising also elements of the welfare state. This complexity of the rights landscape requires cognizance and awareness of, and a discursive approach to, various sources of information and rights, and the asymmetrical power relationships at the intersection of the workplace and the broader sociopolitical level.

The second theoretical strand relevant for researching the concept of workers’ rights is hence critical information literacy which embraces an analysis of ‘social and political ideologies embedded within economies of ideas and information’ (Kapitzke, 2003, p. 61) and encourages a critical and discursive approach to information (Simmons, 2005, in Tewell, 2015, p. 25). Critical information literacy brings about a fundamental shift in thinking about information literacy by focusing on the power relationships between social actors (Cope, 2010, p. 15) and questioning the ways in which information is constructed, disseminated and understood (ibid., p. 25). As noted above, it focuses on empowering and liberating people and the most critical tool to that end is consciousness raising (Freire, 1970) by which people become not only aware of the issues and context but also critical of them. Those tenets of critical theory and pedagogy, inherent in critical information literacy, provide a means to recognise oppression and its causes and consequences, and to mount opposition. Heightened awareness of injustices and critical pedagogy can help increase the abilities of the people, knowledge, awareness and agency needed to challenge social injustice, including participation through methods such as protests and collective action (Smith, 2013, p. 20). The aim of critical literacy is thus to give voice to the silenced (Doherty, 2007), and to enable people to participate in the decisions and events that affect their lives (Whitworth, 2009, p. 118).

Research questions and hypotheses

In order better to understand workers’ information literacy practice and the correlation between information literacy and the state of workers’ rights, the research was framed according to the inherently activist and emancipatory principles of critical pedagogy and literacy. It focused on the broad question of how workers behave in relation to information about and the protection of their rights, and on the impact of critical consciousness in that regard. The following questions drove the research:

RQ1. Are there any differences between cohorts of workers in their perceived level of being informed, and in their information behaviour, dependent on:

RQ1.1. education, and

RQ1.2. trade union activity in the workplace?

RQ2. How do workers obtain information about their rights at work?

RQ3. Is there a correlation between the level of being informed about workers’ rights and:

RQ3.1. the violations of those rights, and

RQ3.2. workers’ readiness to fight for them?

Four hypotheses were formulated:

H1. There are significant differences in the level of being informed and their information behaviour based on education.

H2. Trade union members and workers employed at an employer where a trade union is active are better informed about their rights at work.

H3. Workers mainly receive information on their rights at work from employers, and actively seek information only where they suspect their rights have been violated.

H4. Workers who are better informed about workers’ rights face fewer violations of rights, and those workers exhibit greater readiness to be actively involved in the protection of their rights and the fight for better ones.

Methodology and sampling

The research, designed and carried out by the lead author, used quantitative methodology. A structured questionnaire (see Appendix) consisting of fifty questions was used as an instrument. The questions were primarily closed, employing a combination of yes/no, multiple choice, an option of elaborating on an answer and ratings based on a five-point Likert scale; while one question was open-ended. More complex answers were categorised later and are shown in the overall results.

Responses were gathered during April 13-22, 2021. Data analysis, with both descriptive and inferential statistics, was carried out using SPSS and Excel. Both parametric and nonparametric tests were performed: parametric t-test for independent samples and proportions, and analysis of variance; and nonparametric chi-squared test for frequency differences.

The research instrument was partly informed by Wilson’s information behaviour models. Wilson defines information behaviour as ‘the totality of human behavior in relation to sources and channels of information, including both active and passive information seeking, and information use’ (2000, p. 49). Wilson’s approach is person-centred and focused on the information needs (physiological, cognitive or affective) that prompt information behaviour and contexts (e.g. individual, work, life, socio-cultural and the political-economic environment), as well as the personal, interpersonal or environmental barriers (subsequently replaced with ‘intervening variables’ (Wilson, 1997) which may influence it. Information seeking behaviour is, he argues, a problem-solving and goal-directed activity (Wilson, 1999, and the stages of the information seeking process are the phases of resolving a problem within its context (Wilson, et al., 2002). Of interest to this research are the risk/reward and social cognitive theories which extend these intervening variables (and which fit with a critical aspect of the questionnaire and variables such as trade union membership and readiness to fight for workers’ rights) to examine both the obstacles and the enablers to information seeking.

Specifically, the research questionnaire was conceived to examine workers’ information seeking behaviour in relation to workers’ rights, the motives that prompt their specific behaviour and the barriers or enablers to their information seeking, for instance social risks and self-efficacy (confidence in the skills that one is using) (Bandura, 1982). The problem-solving aspect was also explored by investigating the specific workers’ rights-related issues towards which information behaviour is geared.

The questionnaire contained the following sets of questions: on demography, employment status and union activity in the workplace; on the self-assessed level of being informed about workers’ rights and of information competences; on information behaviour (finding and using information about rights); and on evaluating information and information sources, using information in the protection of and fight for rights, etc.).

Respondents fitting the selection criteria for a nationally representative sample (older than 16, employed on the basis of an employment contract) were recruited from the online HrNation panel of the Hendal market research agency which collected the responses. Respondents received a protected link to the questionnaire via e-mail. The sample of employed people in Croatia was selected with N=500 respondents, and was set according to county, age and sex in line with the data of the Croatian Bureau of Statistics (CBS, 2019). Additionally, during the collection of the data, quotas by employment status, sector of employment, size of company and union membership were monitored. Table 1 provides further information about the sample.

The results are shown in the overall sample and, where relevant, in sub-samples with regard to education, level of being informed about workers’ rights and union membership.

| Respondents | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 51.4 |

| Female | 48.6 | |

| Age | 18 or less | 0.2 |

| 19-24 | 5.8 | |

| 25-34 | 23.4 | |

| 35-49 | 41.8 | |

| 50-64 | 28.2 | |

| 65+ | 0.6 | |

| Education | No formal education (unfinished primary school) | 0.2 |

| Primary (8 grades) | 0.4 | |

| Secondary | 56.0 | |

| Undergraduate study | 13.6 | |

| Graduate study | 26.2 | |

| Masters/PhD | 3.6 | |

| Sector of employment | Private | 55.8 |

| Public (Public/state-owned administration, public services, public company) | 41.6 | |

| Non-profit | 2.6 | |

| Occupation | Administrative/clerical support | 29.2 |

| Services and sales | 18.2 | |

| Scientists, engineers, experts | 13.8 | |

| Technicians and associate professionals | 13.2 | |

| Elementary | 9.0 | |

| Plant and machine operators, assemblers | 4.8 | |

| Craft and related trades | 4.6 | |

| Legislators, officials and directors | 3.0 | |

| Artistic occupations | 2.2 | |

| Armed forces occupations | 1.6 | |

| Skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers | 0.4 | |

| Employment contract | Open-ended | 82.0 |

| Fixed-term (renewed several times) | 8.0 | |

| Fixed-term (concluded for the first time) | 7.6 | |

| Part-time (work for multiple employers) | 1.0 | |

| Permanent seasonal work | 0.8 | |

| Temporary agency work | 0.6 | |

| Trade union membership | Member | 22.6 |

| Non-member | 75.8 | |

| No reply | 1.6 | |

Findings and discussion

The findings are grouped according to the specific research questions and hypotheses.

Differences in the level of being informed and information behaviour based on education

The first group of findings pertains to research question RQ1.1 of differences in the perceived level of being informed and with regard to information behaviour depending on education; and to hypothesis H1 that there are significant differences between workers of different education levels.

More than half (52%) of respondents state they are informed about their workers’ rights (median value 4), although 28% state that they are neither informed nor uninformed. Statistical analysis shows no significant differences with regard to education level (Table 2).

| Level of being informed about workers' rights | Education level | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary school (N=280) | Undergraduate study (N=68) | Graduate study (N=131) | MA/PhD (N=18)* | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| 3.7 | 0.79 | 3.5 | 0.97 | 3.74 | 0.79 | 3.78 | 0.73 | |

| Analysis of variance |

Df=3; F=1.86; p=0.14; Eta²=0.01 |

|||||||

| Note: df= degrees of freedom; F= F ratio; p= probability level; Eta²= Eta squared (effect size) | ||||||||

Nevertheless, when asked to identify the main problems in seeking and obtaining information about workers’ rights, by assessing their agreement with statements on a 5-point scale, respondents with secondary education, in contrast to those with a university degree (Table 3), tend to state that they do not know how to assess which information is relevant, and that they consider information is denied to them on purpose. This was confirmed by the individual post-hoc (Scheffé) tests and by analysis of variance highlighting a significant difference in the variables: v1 (F(3)=4.56; p<.01); v5 (F(3)=5.15; p<.05); v7 (F(3)=3.02; p<.05), and v8 (F(3)=4.47; p<.01).

| Variables ‘Perceived problems’ | Education level | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary school (N=280) | Undergraduate study (N=68) | Graduate study (N=131) | MA/PhD (N=18)* | Analysis of variance (ANOVA) | ||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | df | F | p | Eta² | |

| v1 I often find it difficult to understand information about workers’ rights | 3.3 | 1.22 | 2.8 | 1.25 | 2.9 | 1.17 | 3.1 | 1.23 | 3 | 4.56 | 0.00 | .16 |

| v2 Laws, regulations, rules etc. are amended too often | 3.8 | 1.07 | 3.6 | 1.16 | 3.6 | 0.98 | 3.8 | 0.94 | 3 | 0.74 | 0.53 | .07 |

| v3 I find it too difficult to find my way around the abundance of information about workers’ rights | 3.2 | 1.32 | 3.0 | 1.24 | 3.1 | 1.17 | 3.6 | 1.20 | 3 | 1.15 | 0.33 | .08 |

| v4 I do not have sufficient information about workers’ rights | 3.3 | 1.24 | 3.0 | 1.34 | 2.9 | 1.19 | 3.1 | 1.32 | 3 | 2.58 | 0.06 | .12 |

| v5 I think workers are denied info about their rights on purpose | 3.8 | 1.13 | 3.5 | 1.23 | 3.3 | 1.15 | 3.3 | 1.24 | 3 | 5.15 | 0.00 | .17 |

| v6 I think workers do not get truthful or complete information about their rights | 3.7 | 1.14 | 3.5 | 1.00 | 3.5 | 1.09 | 3.6 | 1.29 | 3 | 1.31 | 0.27 | .09 |

| v7 I don’t know where to seek info about rights | 2.9 | 1.30 | 2.8 | 1.33 | 2.6 | 1.20 | 2.5 | 1.10 | 3 | 3.02 | 0.03 | .13 |

| v8 I don’t know how to assess which information is relevant | 3.1 | 1.22 | 2.6 | 1.23 | 2.7 | 1.18 | 2.9 | 1.41 | 3 | 4.47 | 0.00 | .16 |

|

Note: Statistically significant responses are indicated in red. df= degrees of freedom; F= F ratio; p= probability level; Eta²= Eta squared (effect size) |

||||||||||||

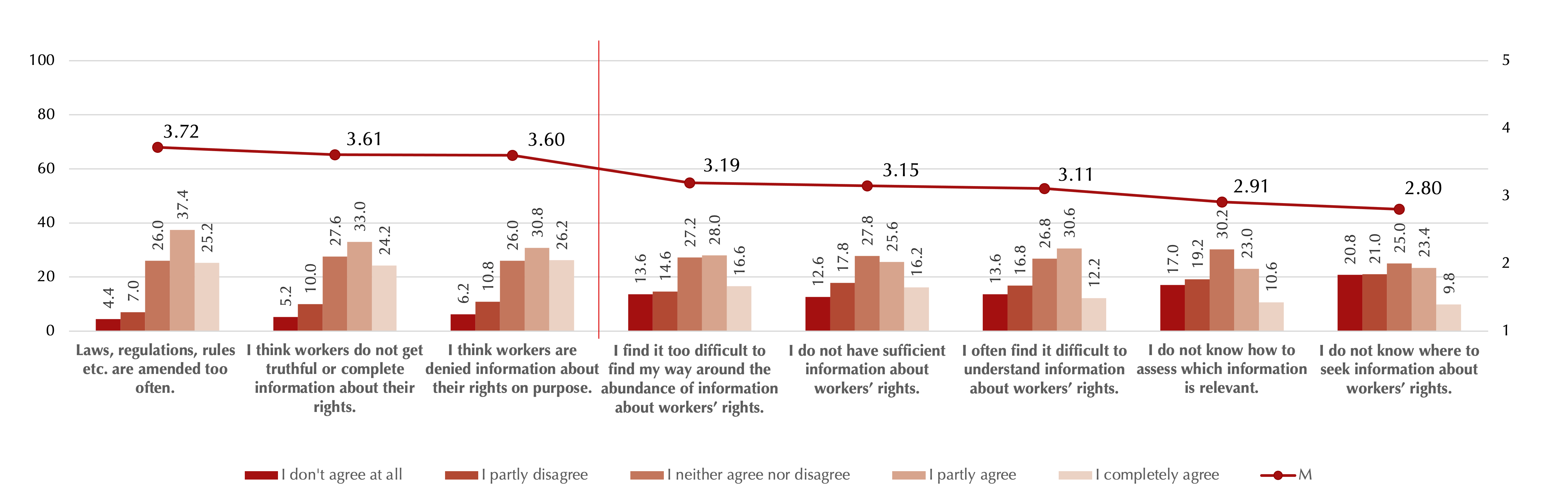

Figure 1 shows that these problems, together with the problem of frequent legislative changes, are among the most commonly identified ones in information seeking and obtaining.

Although an abundance of information is not identified among the most common problems, frequent legislative changes can be interpreted as information abundance and correlates with problems in the contemporary information environment in which information quickly becomes obsolete, and which points to the need to educate people on ways to find and use information. This need was identified by respondents themselves, as shown below.

On the other hand, as shown in Table 4, the higher the education level, the higher the assessment of one’s information competences. More generally, 36% of respondents assessed their competences as good (the most frequent and statistically significant response).

| How do you assess your information competences (knowledge and skills) in seeking, evaluating and using information about workers’ rights? | ||||||||||||

| Education level | Trade union membership | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary school | Undergraduate study | Graduate study | MA/PhD | Member | Non-member | |||||||

| Unsatisfactory | 10.9 | 4.5 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 3.7 | 3.3 | ||||||

| Sufficient | 25.1 | 21.2 | 22.1 | 37.5 | 23.1 | 21.3 | ||||||

| Good | 39.0 | 33.3 | 31.1 | 31.3 | 27.8 | 41.0 | ||||||

| Very good | 21.3 | 33.3 | 33.6 | 18.8 | 36.1 | 28.7 | ||||||

| Excellent | 3.7 | 7.6 | 9.8 | 12.5 | 9.3 | 5.7 | ||||||

| N | 267 | 66 | 122 | 16 | 108 | 122 | ||||||

| Education level | Trade union membership | |||||||||||

| Secondary school (N=280) | Undergraduate study (N=68) | Graduate study (N=131) | MA/PhD (N=18)* | Member (N=108) | Non-member (N=122)) | |||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Self-assessed information competences | 2.8 | 1.01 | 3.2 | 1.10 | 3.3 | 1.01 | 3.1 | 1.06 | 3.2 | 1.03 | 3.1 | 0.92 |

The relatively high self-assessment of information competences and the level of being informed about rights, in conjunction with the finding that the majority of those who do not inform themselves about their rights do not perceive a need for it, is potentially indicative of several things: that respondents lack consciousness and falsely believe that the skills they have are sufficient; and that they have obtained all relevant information and are operating at full knowledge. This points to the problem of information naïveté (Brody, 2008). Pawley argues that not recognising the problem, including the need to be informed, is the biggest problem and a sign that ‘hegemonic “invisible” or premise control is complete’ (Pawley, 1998, p. 142).

Altogether, the research found no differences based on education level in terms of the level of being informed nor in terms of activity or passivity in seeking information about workers’ rights. Thereby, hypothesis H1 is not confirmed.

Differences in the level of being informed based on trade union membership

The second group of findings pertains to research question RQ1.2 and confirms hypothesis H2 that trade union members and workers in union-organised workplaces are better informed about their rights at work.

Trade union members have a significantly higher level of being informed about workers’ rights compared with non-members, as shown in Table 5 and by the independent samples t-test for the variable ‘Level of being informed about workers’ rights’ with regard to trade union membership (M=4.0; t(236)=2.72; p <0.1).

| Level of being informed about workers’ rights | Trade union membership | Independent samples t-test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Member (N=110) | Non-member (N=128) | df | t | p | D | |||

| M | SD | M | SD | 236 | 2.72 | 0.01 | 0.47 | |

| 4.0 | 0.64 | 3.7 | 0.77 | |||||

| Note: df= degrees of freedom; t= t-test; p= probability level; d= Cohen’s d | ||||||||

Union activity at the level of the employer in general also has a positive impact on workers’ level of being informed: workers in a unionised workplace, compared with non-unionised ones, state a higher level of being informed about workers’ rights (a mean value of 3.8 compared to one of 3.5). Furthermore, union members are significantly better informed than non-members about certain specific rights (such as health and safety (t(225.1)=2.18; p=0.03; d=-0.24) and the right to organise (t(233.2)=5.15; p=0.00; d=-0.73)). They are also frequently less likely to perceive information withholding and a lack of information (t(236)=-2.35; p>.05), or that they do not know how to evaluate relevant information (t(236)=-2.06; p>.05) and where to find it (t(236)=-2.57; p>.01). Non-members in general perceive more problems in seeking and obtaining information about workers’ rights (Table 6).

| Variables ‘Perceived problems' | Member (N=110) | Non-member (N=128) | t-test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | df | t | P | D | |

| v1 I often find it difficult to understand information about workers’ rights | 2.9 | 1.26 | 3.1 | 1.20 | 236 | -1.14 | 0.26 | 0.16 |

| v2 Laws, regulations, rules etc. are amended too often | 3.7 | 1.07 | 3.7 | 1.08 | 236 | -0.03 | 0.97 | 0.00 |

| v3 I find it too difficult to find my way around the abundance of information about workers’ rights | 3.1 | 1.26 | 3.1 | 1.29 | 236 | -0.12 | 0.91 | 0.00 |

| v4 I do not have sufficient information about workers’ rights | 2.7 | 1.18 | 3.1 | 1.21 | 236 | -3.12 | 0.00 | 0.33 |

| v5 I think workers are denied info about their rights on purpose | 3.4 | 1.25 | 3.4 | 1.12 | 236 | -0.18 | 0.86 | 0.00 |

| v6 I think workers do not get truthful or complete information about their rights | 3.4 | 1.24 | 3.7 | 1.05 | 236 | -2.35 | 0.02 | 0.23 |

| v7 I don’t know where to seek information about rights | 2.3 | 1.23 | 2.7 | 1.25 | 236 | -2.57 | 0.01 | 0.32 |

| v8 I don’t know how to assess which information is relevant | 2.6 | 1.22 | 2.9 | 1.20 | 236 | -2.06 | 0.04 | 0.25 |

| Note: df= degrees of freedom; t= t-test; p= probability level; d = Cohen’s d | ||||||||

Obtaining information about workers’ rights

The third group of findings relates to research question RQ2 of how workers obtain information about their rights and to hypothesis H3 that they mainly receive information from their employer, actively seeking information only in cases of suspected rights violations.

Respondents are evenly split between being passive recipients of information from the employer and/or the trade union (52%) and active seekers of it (48%). Statistical analysis shows no significant difference according to education level or union membership; this was tested, and confirmed, by chi-squared test (Table 7).

| Which of the following statements is nearest to your information behaviour? | ||||||||

| Approaches to obtaining information | Total | Education level | Trade union membership | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary school | Undergraduate study | Graduate study | MA/PhD | Member | Non-member | |||

| I actively seek information about my rights | 47.8 | 48.6 | 45.6 | 33.3 | 40.0 | 44.5 | ||

| I receive information about workers’ rights from the employer and/or trade union | 52.2 | 51.4 | 54.4 | 51.1 | 66.7 | 60.0 | 55.5 | |

| N | 500 | 280 | 68 | 131 | 18 | 110 | 128 | |

| Chi-squared test for variable ‘Education’: df=3; χ²=1.77; p=0.62 | Chi-squared test for variable ‘Trade union membership’: df=2; χ²=1.23; p=0.54 | |||||||

| Note: df= degrees of freedom; χ²= chi-squared; p= probability level | ||||||||

At the point of employment, the majority of respondents (81%) read their employment contract whereas other sources of rights are read to a lesser degree: works rules by 40% of respondents; and the collective agreement by 30%. The majority (76%) read the document(s) because the employer provides them and only 19% do so on their own initiative.

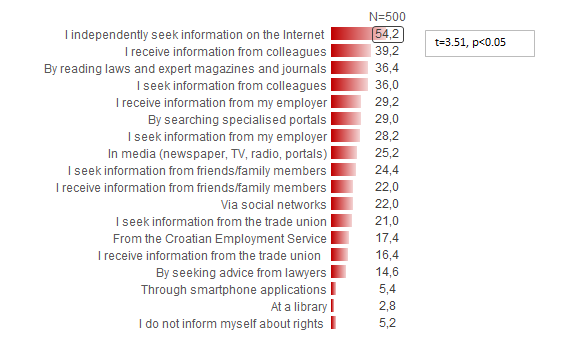

When asked about sources of information on workers’ rights, 67% of respondents state they know where to find information. As Figure 2 shows, 54% state they inform themselves by independently seeking information on the Internet and 39% by receiving information from colleagues; while similar percentages receive information from the employer (29%) or seek it from the employer (28%). Libraries are an information source for less than 3% of respondents.

These results are not surprising: they are consistent with studies showing that, in both job-related and non-work information seeking, the Internet was, even in the early stages of its development, among the most popular information sources (Savolainen, 1999); and it has attracted an increasing number of information seekers (Howard, et al., 2002; Katz and Rice, 2002). The results are also consistent with research showing that social context and social interaction are significantly more important information sources in the workplace context (Lloyd, 2006).

The research finds that only 5% of workers do not inform themselves about their rights at work; these are mostly respondents who describe themselves as uninformed about their rights or are neutral. Although due to the small sample (N=26) these results are only indicative, it is worth noting that the most frequently reported reasons for not seeking information are no perceived need (46%); a view that the Labour Law is a dead letter and that therefore there is no point in seeking information (38%); a lack of time (35%); and a lack of knowledge of where to find information (15%) or how to analyse and interpret it (11%).

Less than half (48%) of respondents do not cross-check the information they receive or find while 52% do (half of those on the Internet). Chi-squared testing (χ²(1)=0.68; p>.05) shows no statistically significant differences in the share of respondents who do (not) cross-check information.

The most commonly reported reasons for seeking information about workers’ rights are the concern that a right has been violated (45%) and where workers are not sure which rights they have (28%).

The majority of respondents (54%) think the employer should be the main source of additional information about workers’ rights, by informing them of any change to working conditions and when employing new workers; while one in three considers that the biggest responsibility for the development of workers’ information competences lies with the employer.

These findings partially confirm hypothesis H3 that workers mainly receive information on their rights from their employers and actively seek it only in case of suspected rights violations.

Before moving on to the next group of findings, two other questions are of interest here. First, as much as 82% of respondents recognise the need for the greater availability of information about workers’ rights, primarily those who self-assess lower level of being informed about their rights (as noted above, the majority think the employer should provide additional information). At the same time, respondents are mostly neutral on the question of the impact of the level of being informed about their rights on the quality of their job (M=3.10; SD=1.09), although those who are better informed consider that this impact is greater: such respondents also declare greater job satisfaction (M=3.9; SD=0.86). Moreover, when asked which type of education would be most helpful for more efficient information seeking, only 7% state they would need educating on the critical evaluation of information while the two types most frequently stated are ways of protecting rights (35%) and on where to find information about rights (30%). This is in line with the fundamental emancipatory principles of critical pedagogy that people need to be educated to be able to act and participate (Castoriadis, 1996, in Giroux, 2011, p. 144), and has clear implications both for information literacy education and for education in general.

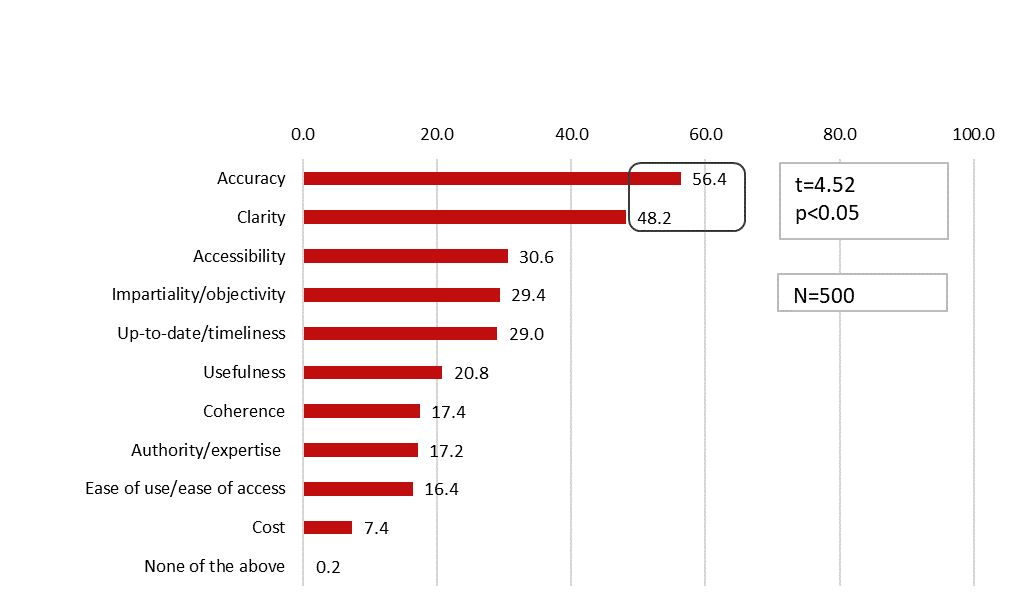

The second question of interest is trust in information sources. The employer is identified as the most trusted of the three sources quoted (employer, trade union and state), although a median value of 3 (neither trust nor distrust) indicates a rather non-committal appreciation. The lowest trust is in the state. As illustrated in Figure 3, the most important elements in the assessment of the reliability and relevance of an information source are accuracy and clarity, while authority and expertise rank quite low. A t-test for proportions was performed between the second (‘clarity’) and third (‘accessibility’) frequency (percentage) (Figure 3); no statistically significant difference between accuracy and clarity was found (t=1.80; p>.05).

This is consistent with a wealth of research confirming mistrust in political and judicial institutions (e.g. Eurobarometer, 2021). That authority and expertise are among the lowest predictors of perceptions of the reliability and relevance of an information source is unsurprising as it is in line with decreasing trust in experts. Among other things, this is a consequence of the Internet rendering authorities unnecessary because of the illusion it creates that we are all experts because we can easily find information (Nichols, 2017).

A possible explanation for reliance on the employer in seeking information about workers’ rights may be found in the cognitive authority and legitimacy which arise out of the employer’s role (Weber, 1947; Wilson, 1983) as well as in the default assumption of accepting information at face value (Lewandowsky, et al., 2012). It may also be explained by the principle of least effort (Zipf, 1949) since the employer is a ready source, especially given that 52% of respondent workplaces are non-unionised and 76% of respondents are not union members. Zipf’s principle postulates that seekers will minimise effort and do only what is sufficient to find and understand the information they seek and need, and has been frequently confirmed in information behaviour research (Case, 2012). Nonetheless, complexity of information behaviour should not be reduced to an explanation which ignores context and individual differences (Case, 2005, p. 291). The more probable reason could be a lack of critical consciousness, even false consciousness, as workers uncritically accept authority and fail to recognise the agenda behind a source of oppression, hence their failure to oppose (Freire, 1970). This claim is further supported by findings that the employer is a source for cross-checking information and for seeking the protection of one’s rights, in particular because, at the same time, in the case of some respondents, fear of reprisal does deter workers from seeking protection. This is discussed further below. An assumption that the authorities (in this case employers) are telling the truth, thus indicating an acceptance of powerlessness, is a sign of being trapped in a neoliberal episteme (Gregory and Higgins, 2013, p. 191).

This research did not explore the reasons for trusting a particular information source nor the preference criteria in why a particular information source was accessed; these should be explored in future research.

Correlation between level of being informed and the violation of rights, the protection of workers’ rights and readiness for activism

The findings which pertain to research questions RQ3.1 and RQ3.2 will be discussed together in relation to hypothesis H4.

Violations of workers’ rights were reported by 38% of respondents while 43% replied in the negative. Also indicative is that 19% did not know if their rights had ever been violated as it could be deduced that this group is probably uninformed about the rights they have. Table 8 illustrates that workers who more positively assess their level of being informed about workers’ rights state to a greater degree that their rights have not been violated; while the greatest occurrence of violations lies among those respondents who assess their level of being informed as weaker. Additionally, an ANOVA (F(2/497)=17.78; p<.01; Eta²=0.26) shows a statistically significant difference in the level of being informed depending on the (non)violation of rights. Workers whose rights have not been violated are better informed (M=3.90, SD=0.69) than those who are not sure whether they have (M=3.35, SD=0.84) and those who declare there has been a violation (M=3.57, SD=0.90)

| Have your workers’ rights ever been violated? | ||||

| Violation of rights | Level of being informed about workers’ rights | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL | Not informed | Neither informed nor uninformed | Informed | |

| Yes | 38.4 | 54.3 | 39.2 | 35.7 |

| No | 43.0 | 23.9 | 32.2 | 50.8 |

| Don’t know | 18.6 | 21.7 | 28.7 | 13.5 |

| N | 500 | 46 | 143 | 311 |

As shown in Table 9, better informed respondents more frequently seek the protection of their rights. The t-test (t(192)=2.44; p<.05, d=0.78) shows a statistically significant difference in the level of being informed based on (not) seeking the protection of violated rights: those who sought protection are better informed (M=3.72, SD=0.91) than those who did not (M=3.41, SD=0.86). While respondents are more likely to seek protection by approaching the employer personally (56%) or through a shop steward (28%), respondents with a higher level of being informed about their rights seek protection mostly through lawsuits with the help of the trade union.

| If your rights have been violated, have you sought their protection? | ||||

| Seeking protection of violated rights | Level of being informed about workers’ rights | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL | Not informed | Neither informed nor uninformed | Informed | |

| Yes | 50.5 | 52.0 | 37.5 | 56.8 |

| No | 49.5 | 48.0 | 62.5 | 43.2 |

| N | 192 | 25 | 56 | 111 |

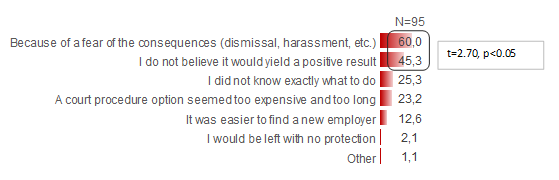

The main reasons for not seeking the protection of rights (Figure 4) are fear of the consequences and lack of faith in a positive outcome. Respondents who do not seek protection because they do not know what to do are those who have a lower level of being informed about workers’ rights.

40% state they are not ready to fight actively for the improvement of their rights because they do not believe anything could be changed. The t-test (t(395.0)=2.94; p<.01, d=1.46) shows a statistically significant difference in the level of being informed where workers are not ready for activism because they do not believe that change is possible. The majority (52%) highlight they are lesser informed about their rights (M=2.54, SD=0.88) compared with those who do not share this view (M=3.76, SD=0.78). A correlation between information competences and readiness for activism was found: the t-test (t(472)=2.24; p<.05, d=0.21) confirms a statistically significant difference in self-assessed information competences in relation to an unreadiness to fight actively for one’s rights due to the belief that nothing could be changed. Those unready to fight actively self-assess lower information competences (M=2.86, SD=1.02) than those who do not declare their lack of belief that change is possible (M=3.08, SD=1.03).

A similar finding emerges from workplace studies among Taiwanese civil servants which show that low levels of information literacy retard collective action, and that information literate individuals are more prone to transformative practices (Chou et al., 2005, 2008 in Whitworth, 2014, p. 158). Also, Pálsdóttir’s research (2008), testing Bandura’s (1982) notion of self-efficacy, finds in the context of the relationship with health information seeking that those who are least active are mainly those with low self-efficacy scores.

The two results emphasised here (not seeking the protection of rights; and unreadiness to fight actively for their improvement, interpreted as critical evaluation and the use of information as elements of information literacy), together with the previous result on the reasons for not seeking information (especially on the Labour Law being a dead letter and there being thus no point in seeking information), point to false consciousness and defeatism, fatalism and passivity among respondents. False consciousness, in particular a failure to perceive injustice and disadvantage, as well as resistance to change and fatalism, harbouring the false belief that protest is futile or impossible, is contrary to one’s interests and contributes to the maintenance of a disadvantaged position (Jost, 1995) and to a deterioration of workers’ rights.

Nonetheless, the research finds that one in four respondents would be ready to fight for better rights by proposing amendments to works rules and collective agreements. These workers are better informed (M=3.84, SD=0.68) than those who are not ready to fight for their rights (M=3.62, SD=0.86), as confirmed by the t-test (t(257.3)=-3.00; p<.01, d=0.28). Those who are ready for activism also assess their information competences as excellent or very good (M=3.19, SD=1.02) unlike those who are not ready (M=2.92, SD=1.02). The t-test (t(472)=2.49; p<.05; d=0.26) confirms a statistically significant difference in self-assessed information competences in relation to readiness for activism.

These findings confirm hypothesis H4 that workers who are more informed about their rights face fewer violations and are more ready to fight actively for them. This has particularly significant implications for policy, education and further research.

Limitations

The main limitation in terms of achieving a nationally representative sample is the online collection of data which excluded participants with lower computer literacy, those from rural areas with poorer Internet access and those with lower education. Furthermore, self-assessment scales, in particular those used in relation to knowledge and information about individual workers’ rights, cannot be considered an objective measurement. Nevertheless, since the research attempted also to explore the issues of motivation, needs and attitudes towards information and the information environment, their use seemed justified. Given the specific socio-economic context, the generalisation of research conclusions to other contexts should be made cautiously. Nonetheless, the findings do offer valuable insight into workers’ information literacy practice and can be useful for follow-up research studies.

Conclusion

The research aimed to explore workers’ information behaviour, their awareness of information (sources) and the ways in which they obtain and use information to seek the protection of their rights at work, therefore contributing to understanding the role that information literacy plays in the pursuit of workers’ rights.

The findings indicate the existence of differences in the level of being informed about rights at work and information behaviour among different cohorts of workers; and their relatively passive behaviour in terms of seeking information about and the protection of their rights. They also point to a lack of critical awareness, even false consciousness, with regard to information sources and their information competences, as well as a lack of recognition of the need to seek information and protect rights. This pertains in particular to a failure to perceive workplace rights violations and to fear, defeatism and fatalism; behaviour which is contrary to their interests and which stems from a lack of faith that change is possible.

Significantly, however, this behaviour is more prominent among respondents with a lower level of being informed about their rights. The research has shown that higher levels of being informed and greater information competences, and more active information seeking behaviour, lead to less frequent violations of rights and to a greater readiness to seek the protection of rights and to fight actively for them. The research also confirms that better informed workers are more aware of the importance of information in the context of overall job quality while trade union membership is proven to be a strong predictor of higher level of being informed and of readiness for activism.

These findings highlight that information literacy, in particular workers’ awareness of their rights and their ability to access information and use it critically, is an important tool in the prevention of rights violations as well as being an indicator of effective opposition when these occur. Therefore, it has potential to address the detrimental effects of defeatism and fatalism not only as regards workers’ rights but in wider society. This affirms the emancipatory character of critical information literacy and its value in the empowerment of workers and the realisation of rights, i.e. social justice, not as a utopian promise but as a genuine possibility. The findings also affirm its central tenet: social justice depends on an informed and engaged citizenry (Downey, 2016, p. 11) in which the precondition for any critical action is critical awareness and critical understanding (cf. Harris, 2010, p. 282).

Consequently, information research can substantially assist the struggle for workers’ rights as it may serve to conceptualise those public policy measures which are aimed at better protecting and improving such rights. It also argues positively for the formation of broader alliances in the pursuit of rights and justice, and advocacy of the importance of information literacy education programmes for students, workers and labour market actors.

Further studies are needed which would encompass other categories of workers and explore the correlation between trust and information literacy. Future research should also, on a transdisciplinary basis, further explore the emancipatory potential of information literacy by investigating obstacles to workers’ better information literacy and the impact this has on job quality.

On the theoretical level, the aim of the paper was to map out a new research framework for information literacy situated at the junction of workplace and critical information literacy. Since this is the logical space for researching workers’ rights due to conceptual premises, this paper brings a first attempt to explore the prospect of the critical workplace information literacy construct which would bridge separate discourses, namely workplace information literacy and critical information literacy.

This refocusing of the critical grounds for information literacy research and education would help empower workers to become aware of the key role that information can play in the pursuit of decent work and social justice. This would help ensure that information literacy remains relevant for citizens and workers, and that it should indeed be seen as a survival skill as the information environment evolves.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable and insightful comments. Dijana Šobota is also thankful to the Friedrich Ebert Foundation of Zagreb and the International Trade Union Confederation for their support of the research reported in this paper.

About the authors

Dijana Šobota is a PhD student in the Department of Information and Communication Sciences, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb, Ivana Lučića 3, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia; and Executive Secretary for international relations and organisational development at the Union of Autonomous Trade Unions of Croatia, Trg kralja Petra Krešimira IV. 2, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia. Her research interests are at the intersection of information literacy and labour issues and rights. She can be contacted at dijana.sobota@sssh.hr.

Sonja Špiranec is Professor in the Department of Information and Communication Sciences, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb, Ivana Lučića 3, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia. She received her PhD from Zagreb University and her research interests are information literacy and knowledge organisation. She can be contacted at sspiran@ffzg.hr.

References

- ACRL. (2016). Framework for information literacy for higher education. ACRL. http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/issues/infolit/framework1.pdf (Internet Archive)

- ALA. (1989). Presidential Committee of Information Literacy: Final Report. http://www.ala.org/acrl/publications/whitepapers/presidential (Internet Archive)

- Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122-147. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

- Battista, A., Ellenwood, D., Gregory, L., Higgins, S., Lilburn, J., Harker, Y. S., & Sweet, C. (2015). Seeking social justice in the ACRL Framework. Communications in Information Literacy, 9(2), 111-125. https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2015.9.2.188

- Brody, R. (2008). The Problem of Information Naïveté. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 59(7), 1124-1127. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20849

- Byström, K., & Järvelin, K. (1995). Task complexity affects information seeking and use. Information Processing & Management, 31, 191-213.

- Case, D. O. (2005). Principle of least effort. In K. E. Fisher, S. Erdelez, & L. McKechnie (Eds.), Theories of information behaviour (pp. 289-292). Information Today.

- Case, D. O. (2012). Looking for information: a survey of research on information seeking, needs and behavior. (3rd ed.). Emerald.

- Cheuk, B. (1998). Modelling the information seeking and use process in the workplace: Employing sense-making approach. Information Research, 4(2), 4-2. http://www.informationr.net/ir/4-2/isic/cheuk.html (Internet Archive)

- Cope, J. (2010). Information literacy and social power. In M. T. Accardi, E. Drabinski, & A. Kumbier (Eds.), Critical library instruction: theories and methods (pp. 13-27). Library Juice Press.

- Croatian Bureau of Statistics. (2019). First release. Persons in paid employment, by activities and counties. Situation as on 31 March 2019. https://www.dzs.hr/Hrv_Eng/publication/2019/09-02-04_01_2019.htm (Internet Archive)

- Doherty, J. J. (2007). No shhing: giving voice to the silenced: an essay in support of critical information literacy. Library Philosophy and Practice, 9(28) (e-Journal). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/133/ (Internet Archive)

- Downey, A. (2016). Critical information literacy: foundations, inspirations and ideas. Library Juice Press.

- Drabinski, E., & Sitar, M. (2016). What standards do and what they don’t. In K. McElroy and N. Pagowsky (Eds.), Critical Library Pedagogy Handbook, Vol. 1 (pp. 53-64). ACRL Press.

- Elmborg, J. (2006). Critical information literacy: implications for instructional practice. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 32(2), 192-199.

- Eurobarometer (2021). Standard Eurobarometer 94. Kantar. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2355. (Internet Archive)

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Herder and Herder.

- Giroux, H. A. (2011). On critical pedagogy. Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Gregory, L. & Higgins, S. (2013). Forces of oppression in the information landscape: free speech and censorship in the United States. In Lua Gregory and Shana Higgins (Eds.), Information literacy and social justice: radical professional praxis (pp. 185-203). Library Juice Press.

- Harris, B. (2010). Encountering values: the place of critical consciousness in the competency standards. In M. T. Accardi, E. Drabinski, & A. Kumbier (Eds.), Critical library instruction: theories and methods (pp. 279-291). Library Juice Press.

- Howard, P. E. N., Rainie, L., & Jones, S. (2002). Days and nights on the Internet. In B. Wellman & C. Haythorntwaite (Eds.), The Internet in everyday life (pp. 45-73). Blackwell.

- International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (2005). Beacons of the information society: the Alexandria Proclamation on Information Literacy and Lifelong Learning. The Hague, The Netherlands. https://bit.ly/3yru8KF (Internet Archive)

- Johnston, B., & Webber, S. (2003). Information literacy in higher education: a review and case study. Studies in Higher Education, 28(3), 335-352.

- Jost, J. T. (1995). Negative illusions: conceptual clarification and psychological evidence concerning false consciousness. Political Psychology, 16(2), 397-424.

- Kapitzke, C. (2003). Information literacy: a review and poststructural critique. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 26(1), 53-66.

- Katz, J., & Rice, R. E. (2002). Social consequences of Internet use: access, involvement and interaction. MIT Press.

- Leckie, G. J., Pettigrew, K.E., & Sylvain, C. (1996). Modeling of the information seeking of professionals: a general model derived from research on engineers, health care professionals and lawyers. Library Quarterly, 66, 161-193.

- Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction, continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(3), 106-131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612451018

- Lloyd, A. (2006). Information literacy landscapes: an emerging picture. Journal of Documentation, 62(5), 570-583.

- Lloyd, A. (2007). Recasting information literacy as socio-cultural practice: implications for library and information science researchers. Information Research, 12(4) paper colis 34. http://informationr.net/ir/12-4/colis/colis34.html (Internet Archive)

- Lloyd, A. (2010). Information literacy landscapes: information literacy in education, workplace and everyday contexts. Chandos.

- Lloyd, A. (2011). Trapped between a rock and a hard place: what counts as information literacy in the workplace and how is it conceptualized? Library Trends, 60(2), 277-296.

- Lloyd, A. (2013). Building information resilient workers: the critical ground of workplace information literacy. What have we learnt? In S. Kurbanoğlu, E. Grassian, D. Mizrachi, R. Catts, & S. Špiranec (Eds.), Worldwide Commonalities and Challenges in Information Literacy Research and Practice, ECIL 2013, Communications in Computer and Information Science, 397. (pp. 219-228). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-03919-0_28

- Lloyd, A. (2017). Learning within for beyond: exploring a workplace information literacy design. In M. Forster (Ed.), Information literacy in the workplace (pp. 97-112). Facet.

- Nichols, T. (2017). The death of expertise: the campaign against established knowledge and why it matters. Oxford University Press.

- Pálsdóttir, Á. (2008). Information behaviour, health self-efficacy beliefs and health behaviour in Icelanders' everyday life. Information Research, 13(1) paper 334. http://informationr.net/ir/13-1/paper334.html (Internet Archive)

- Pawley, C. (1998). Hegemony's handmaid? The library and information studies curriculum from a class perspective. The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, 68(2), 123-144.

- Prague Declaration. (2003). Towards an information literate society. Washington: National Commission on Library and Information Science; National Forum on Information Literacy and UNESCO. http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CI/CI/pdf/PragueDeclaration.pdf (Internet Archive)

- Saunders, L. (2016). Re-framing information literacy for social justice. In S. Kurbanoğlu, J. Boustany, S. Špiranec, E. Grassian, D. Mizrachi, L Roy, T. Çakmak (Eds.), Information Literacy: Key to an Inclusive Society, ECIL 2016, Communications in Computer and Information Science, 676. (pp. 56-65). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52162-6_6

- Savolainen, R. (1999). The role of the Internet in information seeking in context. Information Processing & Management, 35(6), 765-782.

- Sayyad Abdi, E., & Bruce, C. (2015). From workplace to profession: new focus for the information literacy discourse. In S. Kurbanoğlu, J. Boustany, S. Špiranec, E. Grassian, & D. Mizrachi, L. Roy (Eds.), Information Literacy: Moving Toward Sustainability: Third European Conference, ECIL 2015, Tallinn, Estonia, October 19-22, 2015. (pp. 59–69). (Revised Selected Papers). Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28197-1_7.

- Seale, M. (2013). The neoliberal library. In Lua Gregory and Shana Higgins (Eds.), Information literacy and social justice: radical professional praxis (pp. 39-61). Library Juice Press.

- Seale, M. (2016). Enlightenment, neoliberalism, and information literacy. Canadian Journal of Academic Librarianship, 1(1), 80–91.

- Shapiro, J. J., & Hughes, S. K. (1996). Information technology as a liberal art. Educom Review, 31(2), 31-36.

- Smith, L. (2013). Towards a model of critical information literacy instruction for the development of political agency. Journal of Information Literacy, 7(2), 15-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.11645/7.2.1809

- Tewell, E. (2015). A decade of critical information literacy: a review of the literature. Communications in Information Literacy, 9(1), 24-43. https://doi.org/10.1177/016555150002600602

- Weber, M. (1947). The theory of social and economic organization. Free Press.

- White, M. D., Matteson, M., & Abels, E. G. (2008). Beyond dictionaries: Understanding information behavior of professional translators. Journal of Documentation, 64(4), 576-601. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410810884084

- Whitworth, A. (2009). Information obesity. Chandos.

- Whitworth, A. (2014). Radical information literacy: reclaiming the political heart of the IL movement. Chandos.

- Widén, G., Ahmad, F., Nikou, S., Ryan, B., & Cruickshank, P. (2021). Workplace information literacy: measures and methodological challenges. Journal of Information Literacy, 15(2), 26-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.11645/15.2.2812

- Wilson, P. (1983). Second-hand knowledge: an inquiry into cognitive authority. Greenwood Press.

- Wilson, T.D. (1997). Information behaviour: an inter-disciplinary perspective. Information Processing & Management, 33(4), 551-572. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(97)00028-9

- Wilson, T.D. (1999). Models in information behaviour research. Journal of Documentation, 55(3), 249-270. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000007145

- Wilson, T.D. (2000). Human information behavior. Informing Science, 3(2), 49-55.

- Wilson, T.D., Ford, N.J., Ellis, D., Foster, A., & Spink, A. (2002). Information seeking and mediated searching. Part 2. Uncertainty and its correlates. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 53(9), 704-715. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.10082

- Zipf, G.K. (1949). Human behavior and the principle of least effort: an introduction to human ecology. Addison-Wesley.

- Zurkowski, P.G. (1974). The information service environment: relationships and priorities. National Commission on Libraries and Information Science. (Internet Archive)

How to cite this paper

Appendix

Quantitative questionnaire on information literacy in the context of workers' rights

1. Sex:a) M

b) F

c) Other/don’t want to identify

2. How old are you?

a) 18 or less

b) 19-24

c) 25-34

d) 35-49

e) 50-64

f) 65 or more

3. What is your highest education level obtained?

a) No formal education (unfinished primary education)

b) Primary education (8 grades)

c) Secondary education

d) Undergraduate study

e) Graduate study

f) Master/Ph.D.

4. In which county do you work? Please select.

5. Are you employed in an employer on the basis of an employment contract?

a) Yes

b) No – END OF SURVEY

6. What is your current employment contract?

a) Open-ended employment contract

b) Fixed-term employment contract – the first I have concluded with my current employer

c) Fixed-term employment contract which the employer has already renewed at least twice

d) Employment contract with a temporary work agency

e) Part-time employment contract (work for multiple employers)

f) Employment contract for permanent seasonal work

7. In which of the following sectors do you work?

a) Public sector (public/state administration, public services or public company)

b) Private sector

c) Non-profit sector

8. What is the activity of your employer?

a) Agriculture, forestry and fishing

b) Mining and quarrying

c) Manufacturing industry

d) Electricity, gas, steam and air-conditioning supply

e) Water supply, sewage, waste management and remediation

f) Construction

g) Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles

h) Transportation and storage

i) Accommodation and food service activities

j) Information and communications

k) Financial and insurance activities

l) Real estate activities

m) Professional, scientific and technical activities

n) Administrative and support service activities

o) Public administration and defence, compulsory social security

p) Education

q) Healthcare and social welfare

r) Arts, entertainment and recreation

s) Other services

9. How many employees does the company or institution in which you work employ?

a) Up to 10 employees

b) 11-50 employees

c) 51-249 employees

d) 250-999 employees

e) 1,000 employees or more

f) Don’t know

10. How long have you worked for your current employer? (Please write in the number of years.)

11. Please select the category which best describes your occupation/current employment.

a) Legislators, officials, directors

b) Scientists, engineers and professionals

c) Technicians and associate professionals

d) Administrative clerks, clerical support workers

e) Service and sales occupations

f) Skilled agricultural, forestry, fishery and hunting workers

g) Craft and related trades workers

h) Plant and machine operators and assemblers

i) Elementary occupations

j) Armed forces occupations

k) Artistic occupations

12. What is your monthly wage for your current or your most recent job?

a) Up to 3,500 kn

b) 3,501-5,000 kn

c) 5,001-6,500 kn

d) 6,501-8,000 kn

e) 8,001-10,000 kn

f) 10,001-12,000 kn

g) 12,001-15,000 kn

h) Higher than 15,000 kn

i) Don’t want to reply

13. Is a trade union active in your employer? a) Yes

b) No

c) Don’t know

14. Are you a member of a trade union?

a) Yes

b) No

c) Don’t want to reply

15. How do you assess your level of information about the rights that you as a worker have (on a scale from 1 to 5, where “1”=I am not informed at all, and “5”=I am fully informed)?

16. How do you assess your level of information about the rights that you as a worker have (on a scale from 1 to 5, where “1”=I am not informed at all, and “5”=I am fully informed) in relation to the following issues:

ROTATION

a) Working time, including overtime

b) Working time distribution

c) Wages

d) Other material rights

e) Annual leave

f) Protection against dismissal

g) Occupational health and safety

h) Right to trade union organising

i) Right to strike

17. Which of the following statements is nearest to your information behaviour?

a) I actively seek information about my workers’ rights.

b) I receive information about workers’ rights from the employer and/or trade union.

17a. On a scale from 1 to 5, where “1”=I don’t agree at all, and “5”= I completely agree, please assess your agreement with each of the following statements which relate to problems in accessing information about workers’ rights:

ROTATION

a) I often find it difficult to understand information about workers’ rights.

b) Laws, regulations, rules etc. are amended too often.

c) I find it too difficult to find my way around the abundance of information about workers’ rights.

d) I do not have sufficient information about workers’ rights.

e) I think workers are denied information about their rights on purpose.

f) I think workers do not get truthful or complete information about their rights.

g) I do not know where to seek information about workers’ rights.

h) I do not know how to assess which information is relevant.

18. While concluding your employment contract, did you read: a) Employment contract

b) Works rules

c) Collective agreement

Yes / No / Don’t remember / There is no collective agreement concluded at the level of my employer / My employer does not have works rules

If yes to any of the replies under Q18:

19. If you did read the employment contract/works rules/collective agreement, was it:

a) Following my own request

b) The employer showed it to me

c) The trade union showed it to me

d) Other (please specify)

20. Have you ever been, in your current job or during your career, in a situation that you are not sure or cannot establish whether your employer has violated some of your workers’ rights by his/her behaviour?

a) Yes

b) No

c) Don’t know

21. Do you know where to find information about your rights as a worker?

a) Yes

b) No

22. How do you keep yourself updated about your rights as a worker? Please select ALL replies that apply to you.

ROTATION

a) I get information from my employer

b) I get information from the trade union (shop steward, specialist, leadership)

c) I get information from colleagues

d) I get information from friends/family members

e) I seek information from my employer

f) I seek information from the trade union

g) I seek information from colleagues

h) I seek information from friends/family members

i) I independently seek information on the Internet

j) Via social networks

k) By searching specialised portals

l) Through smartphone applications

m) By reading laws and professional magazines and journals

n) By seeking advice from lawyers

o) From the Croatian Employment Service

p) At a library

q) In media (newspaper, TV, radio, portals)

r) I do not inform myself about rights

If a reply is a-q under Q22 (for the whole block until Q30)

23. Do you cross-check the information about workers’ rights that you get/find?

a) Yes

b) No

If yes to Q23:

24. If yes, in which way and how do you cross-check information about workers’ rights? Please write in your reply.

25. When do you most often update yourself about your workers’ rights? Multiple replies possible.

a) When I think that some of my rights have been violated

b) When laws and regulations are being amended

c) When a new collective agreement is being concluded or an existing one amended

d) When I am not sure what rights I have

e) When a trade union organises a protest in relation to some issues important for workers

f) Other (please specify)

26. How do you assess your own competences (knowledge and skills) of seeking, evaluating and using information about workers’ rights?

a) Unsatisfactory

b) Sufficient

c) Good

d) Very good

e) Excellent

27. In your opinion, who is most responsible for the development of workers’ competences with regard to understanding information about workers’ rights?

ROTATION

a) School/faculty

b) Croatian Employment Service

c) Employer

d) Trade union

e) One own’s independent learning

f) Other (please specify)

28. What kind of education and advice would be most useful for accessing information about workers’ rights more successfully?

ROTATION

a) Education about sources of rights

b) Education about where to find information

c) Education on the ways of seeking information (Internet use, communication technology etc.)

d) Education on the critical evaluation of information

e) Education on ways of protecting rights

f) Other (please specify)

29. In your opinion, which documents are most important for establishing information about your workers’ rights? Please select a maximum of THREE replies.

ROTATION

a) Employment contract

b) Works rules

c) Collective agreement

d) Labour Law

e) Other law which regulates the activity I am employed in

f) Occupational Safety and Health Act

g) The Constitution of the Republic of Croatia

h) international documents (e.g. EU regulations and directives, conventions of the International Labour Organization)

30. On what issues related to workers’ rights have you sought information so far? Multiple replies possible.

ROTATION

a) Wages and/or wage supplements

b) Other material rights (e.g. Christmas bonus, awards, etc.)

c) Working time, including overtime

d) Annual leave

e) Daily or weekly rest periods

f) Paid leave for important personal needs

g) The use of maternity, parental or adoption leave

h) Occupational safety and health

i) Notice periods

j) Severance pay

k) Entitlement to education

l) Right to trade union organising

m) Right to strike

n) Other (please specify)

If reply r under Q 22:

31. If you do not keep yourself updated about workers’ rights, what is the reason for that? Multiple replies possible.

a) The Labour Law in Croatia is a dead letter so there is no point in updating myself

b) My shop steward is not capable of providing important information

c) I do not know where to find information

d) I do not have the need to do so

e) I do not have the necessary knowledge to understand and/or interpret information by myself

f) I do not have the time

g) Other (please specify)

ALL

32. Have your rights ever been violated?

a) Yes

b) No

c) Don’t know

If yes to Q32:

33. If your rights have been violated, did you then seek to protect them?

a) Yes

b) No

If yes to Q33:

34. If yes, how? Multiple replies possible.

ROTATION

a) By approaching the employer in person

b) By approaching the employer through the trade union

c) By approaching the employer through the works council

d) By submitting a written request for the protection of my rights

e) By making a complaint (with the help of the trade union)

f) By making a complaint (by hiring a lawyer)

g) By going on strike

h) By participating in protests

i) Other (please specify)

If no to Q33:

35. If no, why not? Multiple replies possible. ROTATION

a) Because of a fear of the consequences (dismissal, harassment, etc.)

b) I do not believe it would yield a positive result

c) A court procedure option seemed too expensive and too long

d) It was easier to find a new employer

e) I did not know exactly what to do

f) Other (please specify)

ALL

36. Are you ready to stand up more actively for a higher level of rights? Multiple replies possible.

a) Yes, by joining a trade union

b) Yes, by active participation in a trade union and trade union activities

c) Yes, by taking part in protests and strikes

d) Yes, by proposing amendments to works rules, collective agreements, etc.

e) No, because I do not believe that anything can be changed

f) No, because my employer would not tolerate it

37. If your employer is covered by a collective agreement, have you ever checked the rights that you have under that collective agreement?

a) Yes

b) No

c) We do not have a collective agreement

If yes to Q37: (for block until Q41)

38. On which rights did you seek information? Please specify.

39. How did you seek or get information about the collective agreement?

a) The employer informed me

b) The trade union informed me

c) I had to ask for information from the employer

d) I sought information from the trade union

e) I sought information from colleagues

f) Other (please specify)

40. Have you ever asked for any clarification of your rights under the collective agreement?

a) Yes

b) No

If yes to Q40:

41. If yes, from whom?

a) From the employer

b) From the trade union

c) From colleagues

d) Other (please specify)

ALL

42. In what way do you communicate with and/or approach your employer with regard to issues pertaining to your rights and/or obligations? Multiple replies possible.

ROTATION

a) Conversation (face-to-face)

b) E-mail

c) By telephone (calls or messages)

d) Through a company Website

e) Through a shop steward

f) Through a works council

g) I do not communicate with the employer

43. What is the most common way in which your employer informs you about any developments related to your rights as a worker? Multiple replies possible.

ROTATION

a) Conversation (face-to-face)

b) E-mail

c) By telephone (calls or messages)

d) Through a company Website

e) By way of a noticeboard

f) In meetings (a meeting of employees or similar)

g) Other (please specify)

h) The employer does not inform me of any developments related to my workers’ rights.

44. What is the most common way in which the trade union updates you about any developments related to your workers’ rights? Multiple replies possible.

ROTATION

a) Conversation with a shop steward

b) By way of a trade union noticeboard

c) In meetings (local union meeting, mass meeting of employees or similar)

d) Through a union Website

e) Via trade union social media channels

f) Through a smartphone application

g) Through a trade union magazine

h) Through leaflets, posters, etc.

i) By organising education courses

j) Other (please specify)

k) There is no trade union in my employer

l) I am not a member of a trade union; therefore the trade union does not keep me updated

45. Do you think that more information about your workers’ rights should be available to you?

a) Yes

b) No

46. Where should this information come from? Multiple replies possible.

ROTATION

a) It should be a part of the school curriculum

b) From the Croatian Employment Service

c) The employer should provide full information to a new employee at the moment of employment, before the conclusion of the employment contract

d) The employer should inform workers of every change to working conditions

e) There should be more associations/organisations that provide such information

f) Trade unions should organise the provision of information

g) The state should set up a dedicated Website

47. Please indicate your trust in each of the following sources of information about your rights as a worker. Please use the 1-5 scale, where “1”=I have no trust, and “5”=I have full trust: a) Employer

b) Trade union

c) State

48. When assessing the reliability and relevance of the source of information, which of the following is most important for you? You can select a maximum of THREE replies.

ROTATION

a) Accuracy

b) Usefulness

c) Coherence

d) Clarity

e) Authority/expertise

f) Accessibility

g) Up-to-date/timeliness