The Relevance of Theory and

a New Approach to Library Structure

D. A. WHITE AND T. D. WILSON

This paper was prompted by a realisation that, after a long period of study, there seem to be serious gaps in our understanding of the organisational nature of libraries. There is a real lack of applied, or applicable, theory in this area and only a limited amount of empirical field-based enquiry. The subject under immediate study was that of organisational conflict. A review of the management and sociological literature revealed theoretical complexity and terminological confusion.There is no general agreement in the literature on a definition of the term conflict, (Bell and Blakeney, 1977). There is no coherent body of theory on the subject, (Thomas, 1976). The theories that do exist seem to have little real basis in fact. Empirical work, as so often happens in attempts at hypothesis verification, have concentrated on very small, quantifiable problems. In short there seemed to be little to go on. Moreover it is questionable as to how useful the constant modification, application and verification of existing theory is to research in hitherto unexplored areas of organisational activity.

The problem of borrowed theory and consequent hypotheses is one that has pervaded the social sciences. It may stem from the way that sociology has been done in the past. The drive to be recognised as a science led to an emphasis being placed on quantification as a method: this has brought too great an emphasis on verification as the chief criterion for excellent research. The bulk of theory has been the product of sociological imagination and not always the result of investigation in the field. Hence, its relation to many areas of behaviour is at least dubious and for the most part irrelevant. Being able to show some part of a theory to be proveable is no judgement of its worth. The 'worth' of a theory must be based on its relevance and that will lie in its applicability to an area of study and its ability to explain particular problems. Glaser and Strauss (1967) propose 'grounded theory' as a basis for theory generation, that is: "... the discovery of grounded theory from data systematically obtained from social research ... Then one can be relatively sure that the theory will fit and work." ( Glaser and Strauss, 1967: 2,3). This approach might meet the requirements of explaining particular social or organisational problems better than the kind of logico-deductive theory that has been so prevalent. Such theory would appear to hold more value for both practitioner and researcher.

The most striking thing about the literature of organisational conflict is that there is a good deal of it. The greatest problem, however, is its sheer diversity. Much of it is highly specialised, including a number of different approaches and involving quite different organisational arenas. Conflict studies in organisations, alone, include the interface between union and management, between supervisor and subordinate, among peers, or between different organisational departments or subgroups. Moreover a great deal of work has been done outside the boundaries of organisations in the areas of experimental gaming, small group research, social conflict and international relations.

Some body of theory has emerged and some of the major elements of this work have been succinctly presented in the library literature by Eggleton ( 1979). Particular note must be made of the conceptual work of Pondy (1967), Walton and Button ( 1969) and Schmidt and Kochan (1972). All of these have sought to produce some working theory for explaining conflict within organisations. But for the most part they remain the products of deduction with little general applicability. This may, in itself be quite impossible. Only a very abstract model is likely to be applicable to the study of all organisational conflict phenomena, ( Ephron, 1961).

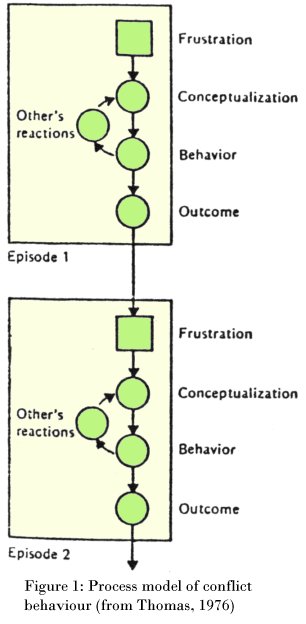

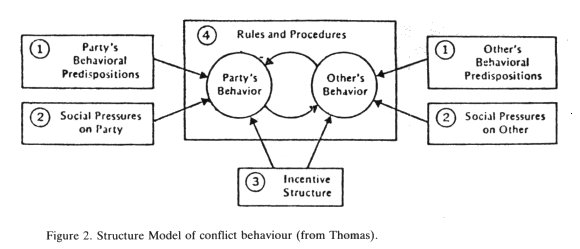

An attempt at producing a. coherent, general model which has not been reported in the library literature has been made by Thomas ( 1976). Working from a large amount of the available literature Thomas suggests two main models for the description of conflict behaviour. These are described as the Process and the Structural models. While describing them separately they are to be considered as interdependent. The Process model builds directly on the work of Pondy (1967) who saw conflict as being more readily understood if it were considered a dynamic process. This model is concerned with the internal dynamics of a particular instance of conflict. It breaks conflict down into its conditions, actions and resultant outcomes or conflict aftermath. A feedback mechanism is built in so that the result of one outbreak of conflict may form the conditions of another, (Fig. 1). Where the Process Model is concerned with behavioural interaction within specific, discrete instances of conflict, the Structural Model is concerned with how underlying conditions shape events and seeks to highlight the central behavioural tendencies withina given dyadic relationship. This in itself may be problematic in that much small group work relies heavliy on dyadic relationships while organisational conflict may be more multi-faceted. Rather than identifying events this model is concerned with the underlying parameters that shape those events, (Fig. 2). Both parties have behavioural predispositions which stem from their motives and abilities. Both are subject to pressures from their surrounding social environments. The parties respond to the conflict incentives (loss/gain) in the situation. Finally, the interaction occurs within a framework of rules and procedures which constrain behaviour. The model does not take account of potential feedback mechanisms. In reality all of these variables would be affected by the outcomes of particular conflicts.

Taken together these models seem to offer a reasonably coherent explanation of conflict behaviour. As a conceptual tool they may guide the re-searcher to consider certain behavioural tendencies that may, or may not, be inherent in conflict. But they assumes the existence of conflict without offering any explanation as to why particular organisational circumstances might produce it. They can identify the conditions of particular conflicts but not the reasons for how those conditions have arisen. To do this the everyday processes of the particular organisation would have to be analysed and understood. These models, like so many similar "pictures of the world", are based on reviews and syntheses of the literature. They are, therefore, continual conceptual adaptations of sets of ideas whose relation to the area under study has become somewhat tenuous. The use of this kind of theory has two major problems. Firstly, it may produce a tendency to "fit" data where they are inappropriate. This is not necessarily a concious act on the part of the researcher. It may be a natural tendency, when armed with a particular set of hypotheses, to categorise data in those terms. Argyris ( 1972, 1980) demostrates the tendency for researchers to match what they see to their own particular version of social reality. Secondly, the constant urge towards the verification of existing theory may prevent the development of theory or ideas that stem directly from the area under study, which may oppose existing theory and which may be more relevant or true. Theory if it is to be relevant should stem from the study of the particular organisation. Such a method should prevent the application of inappropriate concepts and the "fitting" of data. To explain organisational problems in libraries it is necessary to develop more library-based organisation theory.

A step towards this would be to reconsider the way that we view libraries as organisations. Theories set out what we assume to be true about society and organisations in particular. Our assumptions about the nature of libraries as formal organisations may be badly misplaced. This is due to the overriding importance, in research and practice, of organisational structure found in business and industry. By contrast, it is assumed here that libraries are Human Service Organisations, (HSO). An alternative view of the nature of such organisations may facilitate our attempts to understand processes, such as conflict, that occur within them. Such an alternative is presented here and the possible implications for conflict are noted.

Inquiry into the nature of formal organisations has been fixated on the paradigm which Trist (1977) refers to as the "techno-bureaucratic" paradigm. Organisational research tends to make the normative assumption that the technocratic bureaucracy is the ideal paradigm for all organised effort. The validity of this assumption and the applicability of this paradigm to the dynamics of HSO's are questionable. The dominant paradigm is characterised by its focus on management as the rationalising force in organisations. It supposes that management is the appropriate domain for the exercise of influence over the organisational sphere, and it assumes that the most applicable principles for the operation of organisations are those of hierarchical control and coordination. Classical theory maintains that bureaucratic struc- ture is the form most conducive to managerial control and coordination; managers are accountable for subordinates efforts and consequently authority relationships must be clear and explicit.

The technology most appropriate for this vertical system is linear. The assembly line is the archetype; management by objectives, program, planning, and budgeting systems, management information systems and rational problem solving are clear technological preferences. The measures of success for modern organisations are held to be cost efficiency and effectiveness: useful output must exceed total input and the organisation's objectives must be attained.

The industrial paradigm has constraints that restrict the understanding of the unique reality of HSO's This reality is distinctly different from that of the world of business and industry. Human service organisations have been defined as 'the set of organisations whose primary function is to alter the persons behaviour, attributes or social state in order to maintain or enhance his well being...' (Hasenfield and English, 1976). Generally speaking these types of organisations are concentrated in the fields of health, education, and social welfare. Examples include hospitals, health centres, social service departments, public health departments, schools and universities. The inclusion of libraries, academic or public, is appropriate here. While having many structural similarities with other classes of formal organisations, HSO's have distinctive attributes and problems. They have been perceived as different from business concerns, commonweal organisations and mutual benefit organisations (Blau and Scott, 1963; Harshbarger, 1974). New phrases have been coined by some theorists to describe them. Weick (1976) refers to educational systems as "loosely coupled systems" indicating that organisation and individuals are somehow attached but retain their identity and separateness. This state has also been refered to as an "organised anarchy" (Cohen, et al., 1972).

| Dimension | Human Service Organisations | Business/Industrial Organisations Goals |

|---|---|---|

| Primary motive | Service | Profit |

| Primary beneficiaries | Clients | Owners |

| Primary resource base | Public taxes | Private capital |

| Goals | Relatively ambiguous and problemetic | Relatively clear and explicit |

| Psychological orientation of workforce | Professional | Instrumental |

| Transformation processes | Staff-client interactions | Employee-product interactions |

| Connectedness of events and units | Loosely coupled | Tightly coupled |

| Means-end relation | Relatively indeterminant | Relatively determinant |

| Outputs | Relatively unclear and intangible | Relatively clear and tangible |

| Measures of performance | Qualitative | Quantitative |

| Primary environmental influences | The political and and professional communities> | The industry and suppliers |

Human service organisations have different characteristics from business organisations and face different problems. Kouzes and Mico ( 1979) have compiled a table contrasting some of these distinctive attributes with those of business and industry (Fig. 3). Not all of the contrasts apply to all HSO's and industrial organisations. The table is intended to be illustrative rather than definitive, but it forms a useful guide to the kinds of distinction that need to be made.

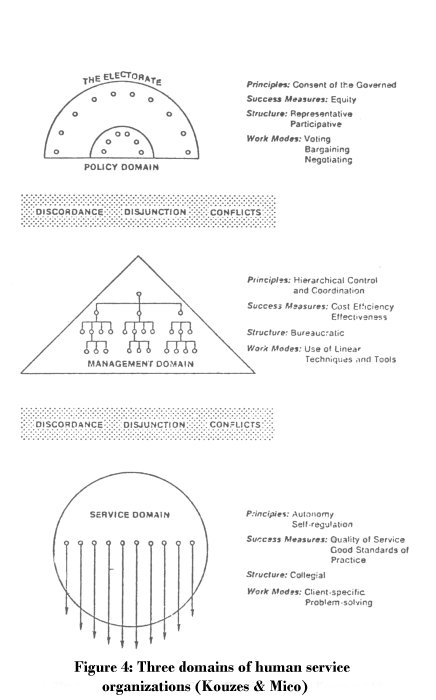

A recognition of this difference led Kouzes and Mico to develop a theory of organisational behaviour based on their experience of working with them and more applicable to them. They have termed their set of suppositions Domain Theory. Domain is defined as a "sphere of influence or control claimed by a social entity". They see HSO's as comprising of three distinct domains - the Policy Domain, the Management Domain and the ServiceDomain. This seems to bear resemblance to the three-tier model of formal organisation postulated by Talcott Parsons ( 1960: 60). The policy, managerial and technical functions suggested by Parsons are very similar, though this has not been noted by the authors. The Policy Domain refers to the organisational level at which governing policies are formulated. This is the highest managerial level of the organisation and involves mediation with the community at large. The policy maker must secure resources for the organisation but is expected to keep face with the community as a whole. He is responsible for the public image of the organisation. The policy maker must justify the existence of the organisation per se and must justify the money being spent. The policy maker has to vie for political power within the community. Hence the policy maker is most concerned with organisational survival and is orientated to the community as resource provider and a source of power. The work modes by which policy decisions are reached necessarily involve negotiating, bargaining and voting.

The second domain, that of management, attempts most to mirror the model of business and industrial management. It is assumed that HSO's should be businesslike in their approach. Management is concerned with the control of the organisation's functions. It has a dual function - mediation between the organisation and the external situation and 'administration' of the organisation's internal affairs. Those in the Management Domain are facilitators of the technical or service function. Their responsibility lies with the disposal of services; their character, adequacy and quality. In carrying out this role they tend to adopt the businesslike principles of hierarchical control and coordination. They attempt to rationalise the organisation, accepting cost efficiency and effectiveness as success measures and bureaucracy as the rightful structure. Consequently the orientation of the Management Domain is to internal processes and method and linear work modes, whether appropriate to the working of HSO's or not, have been imported or adapted.

The third area identified is the Service Domain. Every formal organisation has certain technical functions - this may be the provision of some service. The primary exigencies to which this domain is orientated are those imposed by the nature of the technical task. Members of this domain have two distinctive characteristics: self-autonomy and client-orientation. After years of schooling, professionals consider themselves to be capable of selfgovernment and believe that they have the expertise to respond to the needs and demands of their clients. Principles of autonomy and self-regulation thus dominate the service domain. 'Quality of care' and 'professional standards' are the preferred criteria for measuring success and these quality standards are related to process not product. The members of this domain are, orientated as their work is orientated, towards the client. Individualised, client-specific problem solving is the predominant work mode with a technology that is loosely determined. A graphic presentation of the major characteristics of each domain is included in Figure 4.

Each domain operates by different and contrasting principles, success measures, structural arrangements and work modes. Each is organised in functional and coherent ways that are appropriate to the performance of the primary task of the individual domain. The policy makers have developed structures and work modes to respond to the articulated demands of the community and to establish enough position in the community for bargaining. The managers have developed mechanisms to respond to their accountability for efficient use of resources and attainment of goals. The professionals at the service/technical level face direct demands from clients and have developed their own work modes for dealing with them. These difference serve to separate and disconnect the domains. They promote separate identities - identities that are associated with the domains.

The separateness and incongruence brought by the existence of these domains within the organisation may account for many organisational problems including conflict. Lack of cohesion within the organisation may be a result of the different perceptions of reality about the organisation. There is a tendency to define as problems only those things closely affecting one's own domain's criteria of success. One domain's solution may be another domain's problem. Each domain follows different norms and these norms often legitimate incompatible behaviour. Conformity to rules and procedures is frequently a norm of the Management Domain but it contrasts with the Service Domain's nonconformist norm of individuality.

Where there are such contradictions about principles, norms, success measures, structures and work modes there is bound to be conflict. Much of the vertical conflict experienced in HSO's may be explained by the natural conditions of disjunction and discordance created by the interactions of conflicting domains. Much of the role conflict of middle managers can be seen in terms of the discrepancies of role expectations between these domains. This will be especially keen if, as in libraries, the managers are drawn from the service level.

The paradigm of conflicting domains may serve as a more valuable conceptual guide to explaining conflicts in HSO's and in library organisations. It has some important characteristcs, in terms of theory, which make it more relevant to research in this area. It is original and does not claim validity on the citation and modification of other ideas. Its authors have based their thought on the direct experience of working within the type of organisations which they are seeking to describe. Their experience as Organisational Development consultants within HSO's demonstrated to them the inappropriateness of much of the prevalent theory. It also gave them opportunity to develop theory out of the realities of the day to day operation of these organisations. Theory built on this should be more relevant and meaningful to the practitioner.

A modest test of the model was carried out in the course of interviews with senior and middle-level library managers in pilot work towards the development of methods for studying conflict. Six chief librarians and eight at the middle level working in public, university and polytechnic institutions were interviewed. All respondents recognised the model as a valid description of the organisations within which they worked. This fact alone is some testimony to the model's theoretical value as a basis for examining library organisations, although it cannot provide proof of its 'truth'.

The most common reservations on the part of the respondents related to the hazy distinction between the service and managerial domains that exist in libraries. Librarians in the service domain often have managerial responsibilities as well as client-serving responsibilities. This in itself may help to explain the role conflicts often experienced by middle managers in libraries (Edwards, 1975). The two domains, as noted earlier, make different demands, and when the demands are made in the same person dissonance and stress may result.

Further work is needed to develop and test the Domain Theory model in libraries, but the fact of its 'common-sense' force and its immediate recognition by respondents suggests, at the least, that the way in which it was generated has lessons for library research. 'Grounded theory' generated from experience and observation in organisations may have more to offer a field characterised by its 'pre-theoretical' nature than 'derived theory' where ideas are extracted from previous work without adequate exploration of their applicability.

Bibliography

- Argyris, C. (1972) The applicability of organisational sociology. Cambridge: University Press.

- Argyris, C. (1980). Inner contradictions of rigorous research. London: Academic Press.

- Bell, E. C. and Blakeney, R. N. (1977). Personality correlates of conflict resolution models. Human Relations, 30, 849-857.

- Blau, P. and Scott, W. (1962) Formal organisations. San Francisco, CA: Chandler.

- Cohen, M. D., March, J. G. and Olsen, J. P. A. (1972). A garbage can model of organisational choice. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17, 1-25.

- Edwards, R. M. (1975). The management of libraries and the professional functions of librarians. Library Quarterly, 45, 150-160.

- Eggleton, R. (1979). 'Conflicts in libraries revisited' Libri, 29, 64-77.

- Ephron, L. (1961). Group conflict in organisations: a critical appraisal of recent theories. Berley Journal of Sociology, 6, 53-72.

- Glaser, B. G. and Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, Ill: Aldine Publishing Co.

- Harshbarger, D. (1974). The human service organisation' [in] H. W. Demont and D. Harshbarger (eds.) A handbook of human service organisations. New York, NY: Behavioral Publications.

- Hasenfield, Y. and English, R. A. (1974). Human service organisations; a conceptual overview [in] Y. Hasenfield and R. A. English (eds.) Human service organisations. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Kouzes, J. and Mico, P. R. (1979). Domain theory: an introduction to organisational behavior in human service organisations. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 19, 449-469.

- Parsons, T. (1960) Structure and process in modern societies. Glencoe, Ill: The Free Press.

- Pondy, L. R. (1967) Organisational conflict: concepts and models. Administrative Science Quarterly, 12, 296-320.

- Schmidt, S. M. and Kochan, T. A. (1972) Conflict: towards conceptual clarity. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17, 359-370.

- Thomas, K. W. (1976) Conflict and conflict management, [in] M. D. Dunnette (ed.) Handbook of industrial and organisational psychology. Chicago, Ill.: Rand McNally.

- Trist, E. (1977). Collaboration in work settings: a personal perspective. Journal. of Applied Behavioral Science, 73, 268-278.

- Walton, R. E. and Dutton, J. M. (1969). Management of interdepartmental conflict: a model and a review. Administrative Science Quarterly, 14, 73-78.

- Weick, K. E. (1976). Educational organisations as loosely-coupled systems. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21, 1-19.

This paper was originally published in Representation and Exchange of Knowledge as a Basis of Information Processes, H.J. Dietschmann (ed.) Elsevier Science Publishers B.V. (North-Holland), 1984

How to cite this paper

White, D.A. & Wilson, T.D. (1984) The relevance of theory and a new approach to library structure. Libri, 34(3), 175-185 [Available at http://informationr.net/tdw/publ/papers/1984libri.html]