Questionnaire Design in the Context of Information Research

T. D. WILSON

PROJECT INISS:1 A STUDY OF

INFORMATION-SEEKING BEHAVIOUR IN SOCIAL SERVICES DEPARTMENTS

The work reported here was part of a 5-year action research project to identify the information needs and information-seeking behaviours of social workers and their managers, with a view to introducing evaluated innovations in organizational information systems.

The project had three phases:

1. An observational study of staffs of social services departments, covering all aspects of information transfer and communication. Twenty-two members of staff, ranging from Basic Grade Social Worker to Director of Social Services, were each observed for 1 working week.

2. Interviews of 151 members of staff, stratified by work role and randomly sampled from staff lists using random number tables. The work-role categories used were: Directorate, for the Assistant Director level and above; Middle Management, for managerial levels down to Area Director;

Specialist, for Advisors, Training Officers, and Research Officers; Fieldworkers, for Senior Social Workers and Social Workers; and Administrative Support Staff, for Clerks, etc.

3. An innovation phase in which a number of ideas for improving information transfer were tested in seven departments. The innovations were the direct result of the field-work experience, and were introduced in the departments through negotiation, not only at the top of the organization, but also with the levels of staff most directly affected. Consequently, the innovations adopted were those perceived by the staff to be the most likely to make a contribution to their daily work.

The project as a whole has been widely discussed in the professional social-work press and in the information-science literature, and has led to occasional short courses in information handling and communication under the auspices of the National Institute for Social Work. The results are readily accessible through a number of publications (see Wilson and Streatfield, 1977, 1980, 1981; Streatfield and Wilson, 1980; Wilson et al., 1978). In this chapter, I am concerned with an aspect of the project not previously discussed in detail: the design of our study questionnaire and its employment in the interviews.

PRINCIPLES OF QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN

The design of questionnaires involves a process with several general stages:

1. Preliminary design work on the areas to be explored in the interview.

2. Question wording and sequencing.

3. Physical design or layout.

Pilot testing may be part of any, or all, of these stages of design.

In the standard texts on survey research methods, most attention is given to problems of question wording and sequencing and to physical design (see Hoinville, et al., 1978 ; Hughes, 1976; Madge, 1953; Mayntz et al., 1969; Moser and Kalton, 1971; Oppenheim, 1966). In only two of these texts is preliminary design work given any attention: Hoinville, et al. (1978: 9) note: "The soundest basis for developing structured questionnaires is preliminary small-scale qualitative work to identify ranges of behaviour, attitudes and issues." They then proceed to discuss in-depth interviewing and group interviews as the appropriate kinds of "qualitative work." Oppenheim (1966:. 25) comments: "The earliest stages of pilot work are likely to be exploratory. They might involve lengthy, unstructured interviews; talks with key informants; or the accumulation of essays written around the subject of the inquiry." In none of the texts mentioned, however, is there any detailed discussion of the relationships between pilot work, or "qualitative work," and the more specific aspects of questionnaire design. By presenting a case study, I intend to address these relationships.

THE OBSERVATIONAL PHASE OF

PROJECT INISS

As noted above, the first phase of Project INISS involved 22 person-weeks of observation in five social services departments. The form of observation used was 'structured observation,' as defined by Mintzberg:

a method that couples the flexibility of open-ended observation with the discipline of seeking certain types of structured data. The researcher observes the manager as he performs his work. Each observed event... is categorized by the researcher in a number of ways ... as in the diary method, but with one important difference. The categories are developed during the observation and after it takes place. ( Mintzberg, 1973: 231)

The one amendment we made to this definition, in the case of Project INISS, is that the explanatory categories were developed before, during, and after the observation, relying for the precategorization, in part, upon Mintzberg's work.

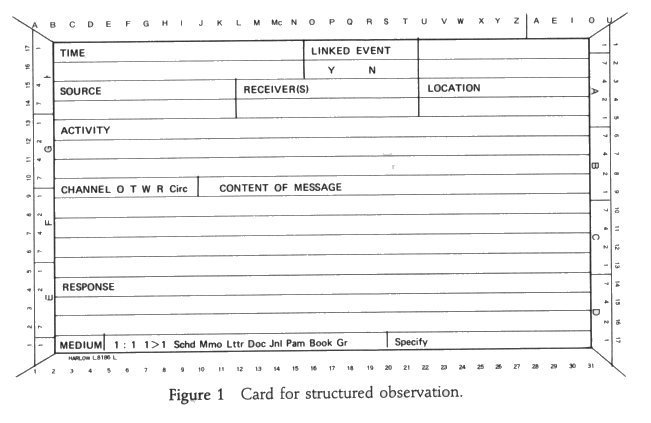

All observed communication events (a change of event being signalled by a change in the subject of communication) were recorded on edge-notched cards (see Figure 1) and, in total, 5,839 such cards were produced for the 22 participants. Manual analysis was performed on the predetermined variables, such as duration of event, location of the event, and channel of communication used. Further definition of events in terms of the activity engaged in while communicating and the subject of the communication was carried out after observation. The categorization of activity was performed using Mintzberg's analysis of managerial behaviour into interpersonal, informational, and decisional roles, slightly expanded by the inclusion of a "social work practitioner" role, a "decision-seeker" role, and a "negotiation-prompter" role, to account for observed non-managerial roles. A simple classification scheme employing two facets, "client or organization focus" and "service focus," was used to categorize the subject of communication events.

Structured observation, therefore, served primarily the purpose of collecting quantitative data. However, it also had an important qualitative significance, in that the observers developed an understanding of the nature of social services work and of the relationships between information channels and information types and the work carried out by different categories of staff in the departments.

This understanding extended to the political, cultural, and interpersonal relationships among individuals and groups of staff in the departments and was of a kind not reducible to statistical analysis, but was of great relevance to the interview phase of the project. The observational experience informed not only the design of the questionnaire but, most importantly, interpersonal relations between interviewers and respondents and organizational relationships between the Project and the departments. For example, interviews were carried out in departments in which observation had been done, and it was obvious, from comments made in passing, that respondents had been influenced in their decision to cooperate by the fact that project staff had established a degree of credibility in the department during the observational phase. Furthermore, having seen the extent of feedback from the research team to the department and to individuals, the managers of departments were prepared to support the project to the extent of sending memoranda to all respondents encouraging cooperation. Given that, at the start of the project, there had been some unwillingness to encourage interviewing and, indeed, a preference for observation, this indicated a very gratifying change of attitude.

THE CONSEQUENCES OF OBSERVATION

FOR QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN

Questionnaire design for the interview phase of the Project occupied some 200 person-hours of work and was greatly influenced by the experience of observation, so far as question wording, overall design and sequencing, design of response cards, and categories of questions were concerned.

The questionnaire that emerged from the design process had seven categories of questions:

1. Work and work role. Before observation, analysis of the literature had suggested that the chief explanatory variable for differences in information-seeking behavior would be the work done by the respondent. Observation had produced support for this proposition, in that differences were discernible among the five broad categories of staff identified above: directorate level; line managers; specialists and advisers; fieldworkers; and administrative support staff. For example, there were differences in relation to time spent in meetings, as noted below. Questions were directed, therefore, to identifying the category into which respondents could be fitted, and to discovering what specialized knowledge any respondent possessed and to what extent this knowledge was communicated to others.

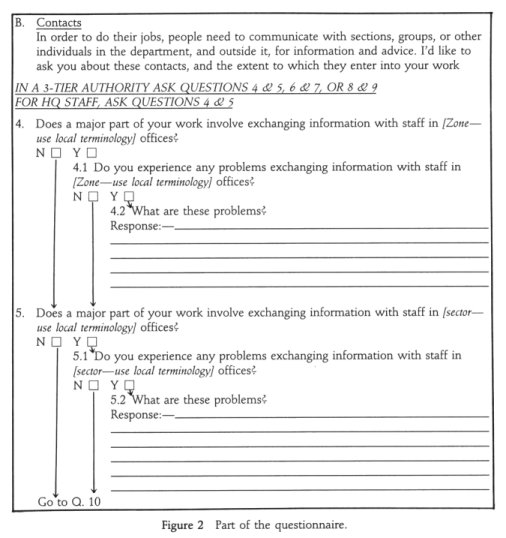

2. Contacts, that is, personal contacts and time spent in formally scheduled meetings. Observation had shown that the dominant mode of information transfer was by word-of-mouth, either face-to-face or over the telephone. These two categories accounted for 60.4% of all observed events. Figure 2 shows a page of the contacts section of the questionnaire and also illustrates the physical layout, with its use of arrows, directing the interviewer to the correct follow-up questions.

Observation had also shown the significance of meetings in social services work, with directorate-level staff spending an average of 16.8 hours a week and line managers 13 hours a week in meetings. As a proportion of the time available in a working week, this could be very demanding: for example, two line managers spent 32% and 33%, respectively, of their working week attending meetings, one social worker 25% of her time, excluding meetings with clients, and a director of social services 70% of his time. As Figure 2 shows, the questions also covered the problems experienced in communicating with the hierarchical levels of the organization.

3. Information use. Figure 3 shows the response sheet used as the lead-in to this set of questions. The categories of information types differed from those usually employed in information science investigations, in that they were based on an analysis of the categories of information used by the subjects observed. Previous information needs studies have mostly used categories of information derived from a librarian's concept of information as journal, monograph, government publication, map, and so forth; that is, the categories were based generally on notions of "form of information."

| Frequency of need | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information Type | Not at all | Less than once a month | Monthly | Weekly | Daily |

| 1. Legal, e.g., act of Parliament, DHSS Circular | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2. Procedural, e.g., departmental procedure note/manual | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3. Names, addresses, telephone numbers, i.e., 'directory information' | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4. Training, e.g., courses, information syllabuses, course materials | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5. Central Government statistical information, e.g., DHSS statistics | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6. Internal statistical information | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7. Records relating to clients, foster parents, adopters | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 8. Internal personnel and/or financial records, e.g., staff lists, budgets | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9. News of developments in social work, including internal changes, whether written or not | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 10. Research in social work | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 11. Evaluations of experience or ideas in social work | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 12. Other—please specify ______________________ | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| ____________________________________________ | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| ____________________________________________ | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| ____________________________________________ | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Observation had shown that various difficulties were experienced in getting various kinds of information and, therefore, follow-up questions sought information on the problems and on access to more general documentary materials. These questions proved useful, as 80% of respondents perceived a daily need for names, addresses and telephone numbers, and as 13% experienced difficulty in getting such information; 53% needed access to client records daily and 21% experienced difficulty in getting access. In other words, two kinds of information of a common nature presented problems for significant minorities of those who needed access.

4. Formal communication systems. In this section, information was sought on the use of various specialized stores and files of information, such as correspondence files, financial records, case record indexes, and departmental or team libraries. The interviews confirmed the experience of observation, that is, that files of information relating to clients and to the availability of foster parents and adopters, as well as "message" books were highly used, whereas the use of team and departmental libraries was more sporadic. Given the nature of social work, this was to be expected.

5. Personal information habits. Observation had shown that social services staff maintained various personal files of information and other information aids, such as diaries and address books. The interview results showed that the most frequently used of these sources was the diary, used daily by 95% of respondents. Address books and notebooks were used daily by 72% and 58%, respectively, of respondents. Again, observation suggested that some personal information files were maintained because of shortcomings in officially provided systems, and 32% of respondents claimed that this was indeed the case.

6. Organizational climate and the structure of the department. Previous work (see Olson, 1977) had suggested that information-seeking behaviour would be related to respondents' perceptions of the "climate" of the organization. Accordingly, a short form of the Litwin and Stringer (1968) climate questionnaire was devised, selecting those items which observation had suggested would be most relevant to information use. Table 1 lists the items selected. However, the only significant relationship was that between climate and work role: fieldwork staff had more negative attitudes towards management than other levels and no relationship was found between climate and any of the information-use variables.

| 1. The jobs in this Department are clearly defined and logically structured. |

| 2. Our management is not so concerned about formal organization and authority, but concentrates instead on getting the right people together to do the job. |

| 3. Supervision in this department is mainly a matter of setting guidelines for subordinates; they then take responsibility for the job. |

| 4. People in this department don't really trust each other enough. |

| 5. In this department it is sometimes unclear who has the formal authority to make a decision. |

| 6. This department is characterised by a relaxed, easy-going working climate. |

| 7. When I am on a difficult assignment I can usually count on getting assistance from my colleagues. |

| 8. In this department people are encouraged to speak their minds, even if it means disagreeing with their superiors. |

| 9. The policies and structure of the department have been clearly explained. |

| 10. One of the problems in this department is that individuals won't take responsibility. |

| 11. It's hard to get to know people in this department. |

| 12. I feel that I am a member of a well-functioning team. |

7. Experience and training. These were questions covering years of experience in social services departments, in the present job, and professional qualifications.

In addition to the direct relationships between observation and questionnaire development noted above, there were two further relationships resulting from observational experience.

First, scenarios were prepared for the five work-role categories on the basis of the narrative accounts prepared following the observation. An example of a scenario is shown in Figure 4. These were sent out to respondents prior to the interviews, and respondents were asked to show whether the account was "very close," "close," or "not at all close" to their "information behaviour" in a particular week. They were also asked to modify the accounts to make them more representative of their experience. Analysis of these accounts was rather difficult and time consuming, but enabled the production of accurate portraits of the relevant categories of staff.

| SCENARIO (13 Information behaviour and contacts) | ||||||

| Social Worker | ||||||

| 1) Please tick the appropriate box below: | ||||||

This description is:

| ||||||

| to my normal working week | ||||||

| Please modify the account to make it a closer fit by changing various words or figures: | ||||||

| James Joyce's main source of information about his work is his supervisor (often during team meetings), but he also obtains information from colleagues in the department (including other social workers) and, to a lesser extent, from external contacts. Mr. Joyce never uses the department library, seldom reads journals (apart from glancing at the department's newsletter) and rarely reads other publications. Files on matters of current importance to Mr. Joyce are usually kept in his office filing cabiner, but most other records are held in the section filing system. He is a member of a department working party and occasionally attends external conferences or courses on professional topics. |

Second, the whole process of design was informed by the team's experience of observation. Individual team members assumed responsibility for particular sections of the questionnaire and prepared draft questions. These were discussed in team meetings in the course of which the researchers played the role of the people they had observed in order to test the propriety, the wording, and the sequencing of questions. The process was quite straightforward: the draft questionnaire was worked through, question by question, while each member of the team tried to respond in terms of the work roles and information-seeking behaviour of the people they had observed. As a consequence, differing perceptions of the meanings of questions emerged, and the influence of differing organizational structures was revealed. In a sense, therefore, the piloting of the questionnaire was done "in house," with the researchers representing respondents. In this way, questions were altered in their wording, resequenced, or dropped from the draft schedule. The final draft version of the questionnaire was then sent to members of the Project's advisory committee and further changes were made as a consequence. The final version of the questionnaire (by then, its sixth incarnation) was used in an interviewer training session before being used in the field. It may have been preferable to pilot the questionnaire in the field but, given the available resources, this was not possible, and the results obtained using the questionnaire suggest that role-playing on the basis of observation, coupled with informed comment from outside, was a satisfactory alternative.

In summary, therefore, the advantages of basing our questionnaire design on observation in the work settings of the respondents were considerable; the observation period was also essential, since without it the relevance of the questions to the respondents would have been problematic.

THE QUESTIONNAIRE IN USE

As noted previously, 151 interviews were carried out in the interview phase of the Project. The five interviewers (that is, the four research workers and the Project Head) all received interviewer training, conducted by Michael Brenner (an outline of the training procedure is given in his chapter in Part I). Training is often neglected in academic research interviewing (judging from the paucity of references to the subject in published research), but in the case of Project INISS, its worth was proved time and again.

One researcher, for example, was faced with a particularly "difficult" respondent on her first interview. The difficulty in the respondent's behaviour was not related to the questions, but to the interviewing relationship, as from time to time he would switch off the tape recorder, leap from his chair, and begin to hurl abuse against his section head and various other colleagues. He would then sit down again, switch on the recorder, and carry on with the interview as though nothing had happened. Without the training she had received, the interviewer might have been unable to cope with a situation such as this. As it happened, she carried on skillfully with the interview: the resulting tape recording gives no indication whatsoever that the respondent was behaving in a curious manner and no indication that the interviewer was disturbed by his activities.

Most of the problems encountered in the interviewing phase were anticipated and none proved insuperable. In fact, the main difficulty was in making contact with busy people (in some cases more than 250 miles away from Sheffield, where the research team was based) to set up the interviews. In 53 cases out of the 151, more than two attempts were needed before contact was made, and in 31 cases, four or more attempts were needed.

A very high level of cooperation was obtained from all respondents. Based on comments made to the interviewers, it is known that the cooperation was at least partly due to the team's having been observing in all four of the departments in which the interviewing was carried out. In other words, the staff in departments had gained the impression that the Project was non-threatening and seriously intentioned and that its work was worth supporting.

As might be expected, in spite of careful design and pretesting, difficulties were experienced with some of the questions. Questions that sought generalizations about the frequency of behaviour or specific statements about the amount of time spent in particular activities presented some problems. For example, some respondents were reluctant to specify a particular frequency in answer to the question, "in general, how often do other people in the department ask you for advice or information about these areas'?-" (areas of personal expertise). Also, the question: "can you estimate about what proportion of your time is spent on these activities^" (referring to a response card), caused considerable difficulty, particularly with fieldwork staff, and frequently disrupted the flow of the interview. The main problems with this question seemed to result from difficulty on the part of the respondents in being able to describe a typical week because of the unpredictable nature of client-oriented work, or being able to generalize about the use of time spent in particular activities, possibly because the separate components of work were not usually identified as such.

The work-role scenarios for social workers, senior social workers, and specialists also caused problems. For social workers, the different demands of work on long-term care teams and intake teams, as well as demands connected with differences between urban and rural social service problems appeared to be at the root of the difficulties. For specialists, two categories of problems arose: First, the scenarios had been prepared with the work of specialists responsible for advisory work in relation to particular client groups (for example, the blind, the mentally handicapped, and the elderly) in mind. Naturally enough, specialists of a different kind, namely training officers, research officers, and information officers, found the scenario less satisfactory. Second, several advisers who appeared in the sample were concerned with residential services, whereas the observational phase had been concerned with fieldwork services only.

Two rather unusual instances of failure to complete response sheets relating to types of information or relevance to the respondents occurred: one respondent was partially sighted and the other chose to breast-feed her child during the interview leaving only one hand free to hold the sheet. In the first case the interviewer read out the categories and recorded the responses; in the second, the interviewer passed the sheets to the respondent in such a way that she did not have to move in accepting them. He then recorded the responses. (The fact that the mother was feeding her child provides unusual evidence of the relaxed manner in which the interview was carried out!)

Finally, the items related to organizational climate caused some problems: frequent hesitation was encountered with some statements containing two elements that were not always seen as naturally associated. For example: "The jobs in this Department are clearly defined and logically structured." Also, some of the apparent underlying assumptions, such as that staff should "take responsibility for the job," were challenged, and items that referred to a "team" almost certainly were understood to refer to the local, social-worker team rather than to staff more generally in the department.

These latter points are all the more disturbing when it is recalled that the Litwin-Stringer list is usually employed in self-administered questionnaire studies, without the presence of an interviewer.

CONCLUSIONS

Effective interviewing demands (for details, see Brenner's chapter in Part I):

1. Trained interviewers.

2. A questionnaire designed to meet the research objectives of a study as well as the requirements of the interview situation.

3. Respondents who are cooperative.

The observational phase of Project INISS contributed to all of these aspects:

1. The interviewers were able to employ their training effectively in the context of the organizations and staff of the departments that constituted the research setting.

2. The questionnaire was relevant; that is, it enabled the gathering of the perceptions of information use and communication held by the respondents.

3. We obtained the cooperation of respondents, at least in part, because they were acquainted with the team's earlier work in the departments.

I do not intend to emphasize that prior observation of a research setting is necessarily the best prerequisite for questionnaire design. Clearly, methods suggested by other authors, such as informal, intensive interviews (see Part II), have their advantages, given that prolonged observation is certainly more expensive and time-consuming than interviewing. However, in a field like information science, where there is relatively little experience of complex, multimethod, social science research, we obtained intimate familiarity with the social life under study, which, in turn, provided an adequate foundation for questionnaire design.

Note

Project on information needs and information services in local authority social services departments ( Wilson, et al., 1978 ).

REFERENCES

- Allen, T. J. (1977). Managing the flow of technology. Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press.

- Bybee, C. R. (1981). Fitting information presentation formats to decision-making. Communication Research, 8, 343-370.

- Crane, D. (1972). Invisible colleges. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Havelock, R. C. (1973). Planning for innovation through dissemination and utilization of knowledge. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Center for Research on the Utilization of Scientific Knowledge.

- Hoinville, C., Jowell, R., et al. (1978). Survey research practice. London: Heinemann.

- Hughes, J. A. (1976). Sociological analysis: methods of discovery. London: Nelson.

- Litwin, G. H., and Stringer, R. A. (1968) Motivation and organizational climate. Boston: Harvard University Press.

- Madge, J. (1953). The tools of social science. London: Longmans.

- Mayntz, R., Holm, K., and Hübner, P. (1969). Introduction to empirical sociology. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin.

- Mintzberg, H. (1973). The nature of managerial work. New York: Harper and Row.

- Moser, C. A., and Kalton, C. (1971). Survey methods in social investigation. London: Heinemann.

- Olson, E. E. (1977) Organizational factors affecting information flow in industry. Aslib Proceedings, 29, 2-11.

- Oppenheim, A. N. (1966). Questionnaire design and attitude measurement. London: Heinemann.

- Price, D. J. de S. (1963). Little science, big science. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Storer, N.W. (ed.) (1973). The sociology of science: theoretical and empirical investigations. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Streatfield, D. R., and Wilson, T. D. (1980). The vital link: information in social services departments. Sheffield: Community Care and the Joint Unit for Social Services Research.

- Weinshall, T.D. (ed.) (1979). Managerial communication: concepts, approaches and techniques. London: Academic Press.

- Wilson, T.D. and Streatfield, D.R. (1977). Information needs in local authority social services departments: an interim report on project INISS. Journal of Documentation, 33, 277-293.

- Wilson, T. D., and Streatfield, D. R. (1980). You can observe a lot. . .: a study of information use in local authority social services departments. Sheffield: University of Sheffield, Department of Information Studies. (Occasional Publications No. 12) [Available at http://informationr.net/tdw/publ/INISS/]

- Wilson, T.D. and Streatfield, D. R. (1981) Structured observation in the investigation of information needs. Social Science Information Studies, 1, 173-184.

- Wilson, T. D., Streatfield, D. R, Mullings, C., Lowndes Smith, V., and Pendleton, B. (1978). Information needs and information services in local authority social services departments (project INISS), final report to the British Library Research and Development Department on stages I and 2, October 1975-December 1977. London: British Library.

How to cite this paper

Wilson, T.D. (1985) Questionnaire design in the context of information research, In: M. Brenner, J. Brown and D. Canter, eds. The research interview: uses and approaches. (pp. 65-77) London: Academic Press. [Available at http://informationr.net/tdw/publ/papers/1985qdesign.html]