A participatory design informed framework for information behaviour studies

Anika Meyer, Ina Fourie, and Preben Hansen.

Introduction. Applying participatory design in educational contextscan improve the congruence between perceptions of students, teachers and instructional designers.Information behaviour activities such as collaborative information seeking and information sharing are core to participatory design. Information behaviour studies related to participatory design must be guided by an information behaviourframework informed by the principles of participatory design. Albeit a few examples of frameworks, reference is mostly only to participatory design steps, phases and stages, with limited acknowledgement of information activities. This paper suggests a participatory design information behaviour framework for studies in educational contexts.

Method. Scoping review of selected publications on participatory design and information behaviour, and participatory design in education.

Analysis. Thematic analysis applied in educational context as exemplar.

Results. A participatory design information behaviour framework must allow for the following constructs: context, participant selection (i.e., actors, stakeholders), definition of shared visions and purposes; roles and tasks; information resources and access; iterative information activities; participatory design steps, phases and stages; consideration of intervening factors; and finer nuances of all of these constructs.

Conclusion. The suggested framework can guide information behaviour studies on participatory design with a focus on information activities.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irisic2004

Introduction and rationale

Researchers such as Agarwal (2018), Fidel and Pejtersen (2004), Hepworth, et al. (2014), and Järvelin and Ingwersen (2004) have argued for taking studies of information behaviour to practical designs such as for information systems, improving information retrieval systems and databases. There have also been many calls to use findings from information behaviour studies to inform the design of information related interventions such as information provision to patients (Fourie, 2008) and enabling access to information for learning and information literacy training (Hepworth, et al., 2014). Thus, signifying an increase of interest in the impact of information behaviour studies (Greifeneder, 2014).

Recognising a range of definitions for information behaviour (Bates, 2010; Case 2012; Ingwersen and Järvelin, 2005; Wilson, 1999), this paper will define information behaviour as all information-related activities, interactions and encounters, including information seeking, information searching, information needs, information encountering, information avoidance, browsing, information use and recognising, expressing and making sense of information needs, as explained by Fourie and Julien (2014). For participatory design, information and knowledge sharing are especially important (Ginige, et al., 2014; Longo, 2014; Skeels, 2010). Furthermore, participatory design and related activities such as collaboration have also started to feature in information behaviour studies (Meyer, et al., 2018; Nickpour, et al., 2014). Participatory design can be seen as a series of methods, tools, techniques and theories that can be applied in information behaviour studies (Keshavarz, 2008).

Over the last decade, design researchers (i.e., researchers in the process of design [Lee, et al., 2017; Lee, et al., 2019]) have shown growing interests in participatory design (Halskov and Hansen, 2015; Robertson and Simonsen, 2012; Sulmon, et al., 2013), extending it to participatory research (Allen, et al., 2019; Andersson, 2018; Bergold and Thomas, 2012) and community participatory research (Jull, et al., 2017). Participatory design in education holds great value to improve the quality of learning spaces, learning activities and teaching methods and individual and collective sense-making of everyday information encounters to advance collective learning, to cultivate metacognition and reflection on learning and teaching, promote creativity and innovation, and develop participatory, collaborative, and democratic competencies (DiSalvo and DiSalvo, 2014; Hughes and Burns, 2019; Könings and McKenney, 2017; Könings, et al., 2014). There has also been an increase in participatory research approaches in educational context (Hughes and Burns, 2019; Ismail and Ibrahim, 2017; Yalman and Yavuzcan, 2015).

Albeit the importance of information sharing and other information behaviour activities in participatory design, there is limited research on information behaviour in participatory design (some exceptions being Ginige, et al., 2014; Longo, 2014; Skeels, 2010). These studies did not explicitly link to any information behaviour model or conceptual framework. In our scoping literature review, we could not identify any use of a participatory design model to inform information behaviour studies. Considering the increased interest in participatory design and participatory research, the value this can bring to the educational context and the prominence of information activities in these processes, it seems timely to explore the process of participatory design and the availability of participatory design models and frameworks to determine how these can be used to ensure appropriate, high-quality information behaviour studies in contexts relevant to contemporary society. Educational contexts will serve as exemplar. This is also in line with work the authors are currently doing (Meyer, et al., 2018).

Based on key textbooks such as Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design (Simonsen and Robertson, 2012), and Participatory Design for Learning (DiSalvo, et al., 2017a), our perception is that participatory design is a holistic process with specific needs for the involvement of participants, processes and tools that must be considered in the design and conduction of information behaviour studies. We thus asked:

Research question: How can participatory design models and frameworks inform information behaviour studies?

RQ1: Which participatory design models and frameworks are available (educational context as exemplar)?

RQ2: Which guidelines on the processes, steps, stages, phases, selection of participants, etc. for participatory design in educational contexts are available?

RQ3: How can insights from RQ1 and RQ2 be combined with insight from traditional information behaviour models to propose a participatory design conceptual framework for participatory design information behaviour studies in a selected context (e.g. education)?

Apart from the introduction and rationale, the paper will cover clarification of key concepts (participatory design, and conceptual frameworks and models); a brief background on (i) information behaviour in participatory design, and (ii) information behaviour studies related to participatory design; a scoping literature review based on thematic analysis of participatory design, frameworks, steps, phases, etc.; a discussion of findings from the thematic analysis; proposal of a nascent participatory design information behaviour (PDIB) framework to support information behaviour studies; recommendations for further work and a conclusion.

Clarification of concepts

Participatory design

Although the literature reflects many useful definitions of participatory design (DiSalvo, et al., 2017a; Kang, et al., 2015; Simonsen and Hertzum, 2012; Simonsen and Robertson, 2012), there are no uniform interpretations (Saad-Sulonen, et al., 2015). According to DiSalvo, et al. (2017b, p. 17), participatory design ‘offers methods and practices for discovering, navigating, and co-creating goals in direct partnership with participants, while simultaneously revealing the constraints and opportunities that these participants face in complex contexts’. In addition, Simonsen and Robertson (2012, p. 3) note that participatory design is ‘a process of investigating, understanding, reflecting upon, establishing, developing, and supporting mutual learning between multiple participants in collective ‘reflection-inaction’. The design and development process of participatory design resulted in various physical and digital systems, products, and services (Muller and Druin, 2012). This does, however, not exclude non-digital products. Muller and Druin (2012, p. 3), furthermore, explain that participatory design ‘is a set of theories, practices, and studies related to end-users as full participants in activities leading to software and hardware computer products and computer-based activities’. Hartson and Pyla (2018) point out that participatory design is a democratic process for design (social and technological) of systems which involve all stakeholders. Participatory design literature predominately tends to use the term stakeholders (Cárdenas-Claros, 2014; Könings, et al., 2014), specifically in an educational context (DiSalvo, et al., 2017a; Hughes and Burns, 2019; Janssen, et al., 2017; Simonsen and Robertson, 2012). ‘Over the years it has taken various forms and conceptualisations including public/community consultation, cooperative design, collective resource approach, and more recently co-design and co-creation’ (Thinyane, et al., 2018, pp. 20-21).

Based on the above definitions by DiSalvo, et al., (2017a), Hartson and Pyla (2018), Muller and Druin (2012), and Simonsen and Robertson (2012), the following operational definition is accepted:

Participatory design entails a variety of constructivist cognitive processes such as collective reflection and understanding in complex contexts, use of appropriate tools and methodologies (i.e., a set of methods and a diverse collection of principles and practices) to actively engage a multicultural community (i.e., users and stakeholders) in creatively designing technologies, tools, environments, and businesses which are more responsive towards different socio-cognitive experiences, tasks and domains. In some contexts, participatory design methods are focused on delivering products that reflect the needs of users, the shared understanding of stakeholders and their values (Kang, et al., 2015, p. 831) and ‘produce a design with an aim of creating an emotional investment for the users’ (Parviainen, et al., 2016, p. 1). Although no specific information activities and related affective and emotional experiences are currently present in the definitions we noted for participatory design; it is worth further consideration as this is important in information behaviour studies (Fourie and Julien, 2014).

Models and conceptual framework

Wilson (1999, p. 250) notes that a ‘model may be described as a framework for thinking about a problem and may evolve into a statement of the relationships among theoretical propositions’. Several information behaviour studies (Niedźwiedzka, 2003; Savolainen, 2016; Wilson, 1999) have used models to produce new theoretical and conceptual frameworks.

Savolainen (2016, p. 650) explains that:

models represent a way of organising a body of knowledge to pave the way towards theories. From this perspective, a model can be conceived as an interim stage in a research discipline, before a theory can be established, serving as a “working strategy” for hypothesis testing.

This implies that ‘a model can simply be described in words by presenting a set of theoretical propositions’. Wilson (2010) added that models could also represent mathematical, textual or graphic constructs. On the other hand, a conceptual framework can be defined as a framework which is based on a set of conceptual and epistemological constructs. It provides a structure to explain a phenomenon, ‘rather than subscribing to specific theories or models’ (Fidel and Pejtersen, 2004).

For this paper, we will draw on participatory design models and frameworks and information behaviour models to develop a conceptual framework for an information behaviour study of a participatory design project.

Need to move from acknowledgement of information behaviour models to a participatory design information behaviour framework

Shenton and Hay-Gibson (2012, p. 92) note that ‘the last 30 years have seen the development of a multiplicity of models constructed within the overall territory of information behaviour’. This is confirmed by Case and Given (2016), Ford (2015) and Hester Meyer (2018) and the many models that have been reported in individual papers. Apart from general information behaviour models (Wilson, 1997, 1999), there are many models focusing on specific information activities (Bukhari, et al., 2016). Such models include Kuhlthau’s information search process model (1991), Foster (2005) confirming that information seeking is not a linear process, Ellis’ (1989) information seeking model highlighting phases and stages (such as starting, differentiating, extracting, verifying and ending applicable to participatory design stages), Leckie, et al.’s. (1996) model of information seeking of professionals and Johnson, et al.’s. (1995) comprehensive model of information seeking. Due to length constraints, these models are not discussed in more detail. Good overviews are, however, offered by Case and Given (2016) and Ford (2015). Much can also be learned about information needs, a key component in information behaviour and the trigger of information seeking, from the work of Dervin (1992) on gaps in knowledge that must be filled and the need for sense-making, Belkin (1980) on anomalies in knowledge (ASK) and Taylor (1968) on the different levels of recognition of information need moving from visceral need (i.e., vague and unexpressed information need) to a conscious need, formalised need, or compromised need (i.e., formal information need). Information sharing prominent in participatory design is not widely acknowledged. Wittenbaum, et al., (2004) created a framework to understand information sharing in decision‐making groups as a motivated process where group members’ goals and features of the context influence what, how and to whom information is shared to fulfil tasks and social outcomes. Savolainen (2019) notes that information behaviour use information sharing interchangeably with information exchange and information transfer, for example, in Wilson’s (1999) model of information behaviour, information sharing is approached in terms of information exchange and information transfer, and in Robson and Robinson’s (2015) revised information seeking and communication model (ISCM) information exchange suggests a two-way flow of information between information providers and between users.

Aforementioned models noted here would undoubtedly be useful for an information behaviour study on participatory design. They raise awareness of the importance of context (Wilson, 1997), intervening variables which could positively or negatively influence an individual’s information seeking behaviour (Wilson, 1997) and especially prior experience (Johnson as cited in Johnson and Case, 2012), different stages and phases that impacts on information needs and preference for information sources (Ellis, 1989), the impact of tasks, roles (especially crucial in participatory design) and responsibilities and awareness of information sources (Byström and Kumpulainen, 2019; Leckie, et al., 1996), and the fluctuation in cognitive states and affective experiences during the search process (Kuhlthau, 1991). Few models acknowledge information sharing as an activity. This is important since information sharing, information encountering, and serendipity are core information activities in participatory design (Conole, et al., 2010).

From the models and studies noted and work by Hester Meyer (2018), information behaviour models raise awareness on the importance of context and situation (Wilson, 1997); user’sinformation need (Dervin, 1992; Taylor, 1968); information activities (Ellis, 1989; Kuhlthau, 1991); sources of information (Byström and Kumpulainen, 2019; Leckie, et al., 1996); and intervening factors (Wilson, 1997). In the next section, we will highlight essential components noted in existing participatory design models and frameworks to inform information behaviour studies.

Method and analysis

For purposes of this paper, we decided to use a scoping literature review. Grant and Booth (2009, p. 101) define a scoping literature review as a ‘preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of available research literature. Aims to identify nature and extent of research evidence (usually including ongoing research)’. The purpose of the scoping literature review was to identify participatory design frameworks or components of such frameworks that we can consider in the development of a participatory design theoretical framework for information behaviour studies. We, therefore, focused on:

- Studies explicitly dealing with participatory design and information behaviour

- Books on participatory design per se

- Research papers on participatory design in educational context.

Key Library and Information Science, educational, and multi-disciplinary databases (such as Library and Information Science Abstracts [LISA], Library and Information Science Source, Emerald Insight, ERIC, Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics) and ScienceDirect) were searched. We performed the following searches on the before-mentioned databases, namely:

- Participatory design and information (behaviour or behaviour) in the title of the document or combinations of title and abstract and keywords. The concept information behaviour yielded little or no applicable literature, and so we used associated terms: information needs, information seeking, information searching, information retrieval, information sharing and information use. A total of seven publications were retrieved.

- Participatory design in combination with education, teaching and learning in the title of the document. A total of 39 publications were retrieved. From these publications, ten specifically contained the terms participatory design as well as education.

- Participatory design framework and participatory design model (searching in all fields). A total of eight publications were retrieved.

The following were applied for manual selection: only full text publications in English; articles, books, book chapters and conference papers; no limit on date published.

Books with participatory design in the title were searched for on the WorldCat Library Catalog and Amazon. A total of 288 books were retrieved. The criteria applied for manual selection included: availability of books in English; subject category of education; no limit on date published (Result = 19 books). Further selection was based on perception of relevance to purpose of paper, resulting in two books, titled: Routledge international handbook of participatory design (Simonsen and Robertson, 2012), and Participatory design for learning (DiSalvo, et al., 2017a).

To structure the scoping literature review, we used thematic analysis. According to Braun and Clarke (2012, p. 57), thematic analysis ‘is a method for systematically identifying, organising, and offering insight into patterns of meaning (themes) across a data set’. A thematic analysis enabled us to identify themes in participatory design literature to create a theoretical framework for studies of information behaviour in educational context. There are various approaches to thematic analysis, e.g. inductive, deductive, semantic, latent, (critical) realist, essentialist and constructionist approaches (Braun and Clarke, 2012). This paper followed an inductive approach; the coding and theme development were directed by the content/ data (Braun and Clarke, 2012).

Thematic analysis: participatory design literature

We applied thematic analysis to bodies of participatory design literature: (i) participatory design studies in education and (ii) participatory design studies mentioning information behaviour and related information activities.

Participatory design in education

Many studies in educational context emphasise both the collaborative nature of learning and the need to improve the congruence between the perceptions of students and those creating the learning environment (Könings, et al., 2014) and the efficiency of instructional design. Hence, there is a necessity to include different stakeholders as design partners in instructional design through participatory design (Könings, et al., 2014) and to consider various theories in participatory design such as activity theory (Zaphiris and Constantinou, 2007), social theory and social science theory (Faiola, 2007), social constructivism (Spinuzzi, 2005) and learning theory (DiSalvo, et al., 2017b). In fact, Roschelle, et al., (2006, p. 606) emphasise the diversity of participants needed in participatory design in education when referring to:

a highly-facilitated, team-based process in which teachers, researchers, and developers work together in defined roles to design an educational innovation, realise the design in one or more prototypes, and evaluate each prototype's significance for addressing a concrete educational need.

Participatory design’s philosophy on design in and for education stems from Rittel’s (1972) interpretation that each challenge can have multiple outcomes, and that endeavours to resolve challenges often result in constructing new, possibly even more complex challenges (which could add a new dimension to the manifestation of information needs). In terms of learning (and teaching) design, participatory design supports mutual learning processes as they unfold between participants in collective reflection-in-action during the design process (van der Velden and Mörtberg, 2015). In the process, critical discussions among various stakeholders are cultivated by addressing power imbalances (McIntyre-Mills, 2010) and focusing on active knowledge and understanding (Lee, et al., 2017). Key findings on participatory design literature in educational context that hold relevance for the development of a participatory design information behaviour framework are reflected in Table 1. The findings in Table 1 were interpreted to identify themes for further analysis.

| Authors and titles of articles | Key findings in terms of participatory design |

|---|---|

| Bang and Vossoughi (2016) |

Participatory design is endogenous design; the intervention and design initiate within (internal to) the field. External intervention should inform negotiation processes, including non-design social and educational justice, educational equity. |

| Cárdenas-Claros (2014) |

Participant selection is based on context and diversity (e.g., language, age, specialisation, profession). Stages related to five design features: analysing the type, location, sequence, click-through and display of help options for computer-assisted language learning (CALL). Design outcomes differ for each feature. Reflection essential after each stage. |

| Collis, et al. (2009) | Three participatory design perspectives: pragmatic (design success based on stakeholders’ domain knowledge); theoretical (encourage mutual learning through idea sharing); political (learning experiences and outcomes influenced by stakeholders’ rights and needs). |

| Conole, et al. (2010) |

Objectives: ongoing stakeholder engagement; informing future design developments. Design processes is an iterative, co-construction and negotiation of shared ideas. Key success factor: mutual trust and respect for the different domain knowledge(s) of stakeholders. Serendipity is a trigger point in design decision-making. |

| Danielsson and Wiberg (2006) |

Spatially distributed teams require facilitators. Participants’ intrinsic motivation encourages their input. Mutual learning is a key feature. |

| Fang and Strobel (2011) |

Knowledge application in authentic tasks (e.g. designing educational game prototypes) indorses individual/group learning. Key features: peer sharing, concept adjustment, team discussions. Participatory design must inspire excitement and motivation. |

| Kallio (2018) | Participatory design is the basis for democratic participation, building agency, meaning and community. |

| Mäkelä and Helfenstein (2016) |

Requires: communality, individuality, comfort, health, novelty and conventionality. Participants’ involvement and self-expression drive participation. |

| Mor and Winters (2008) | A participatory design model must encourage and support interdisciplinary practice and a culture of openness to support participants’ rights. |

| Torrens and Newton (2013) |

Need stimulation activities, e.g. annotation, orthographic, perspective illustration, and sample images (mood boards). Sense of ownership motivates participation. |

| Zaphiris and Constantinou (2007) |

Nine stages with individual activities: building of bridges; analysis of existing tools; borrowing ideas and investigating constraints; discussion of ideas for new tools; creation and evaluation of paper prototypes; building prototypes; evaluating prototypes; building a final tool; testing and analysis of the final tool. Sharing of individual experiences contribute to design, and group dynamics promote sharing of comments. Size and age differences of participants, resource restraints and group member fatigue can be limitations. |

The thematic analysis aimed to identify specific themes to inform an information behaviour study of a participatory design project. The following themes were noted based on Table 1: the importance of reckoning with the intricacies of the context (e.g. an educational context), purpose and need of the design project, expected outcomes, stakeholders’ involvement and roles, nature of participation, internal and external influencing factors, technology and tools needed for the design activities and communication and available sources.

Participatory design and information behaviour with related information activities

Greifeneder (2014) highlights that information behaviour research has grown a great deal over the last couple of years and has taken on new topics and new methods such as participatory design. Although this might be the case, there is still limited literature available mentioning information behaviour and related information activities in participatory design studies (Keshavarz, 2008). (This was very clear from our literature searches.) A study by Keshavarz (2008) refers explicitly to the terms information behaviour and participatory design. This study focused on a participatory design approach to examine users' behaviour, human factors and contexts when designing information retrieval systems. Keshavarz (2008) notes the importance of understanding users’ information activities (i.e., information needs, information seeking, information searching and information retrieval) and context-based aspects such as tasks, environment and organisational setting during the participatory design of information retrieval systems. Somerville and Howard (2010) report on an 'information in context' design project to collaboratively create organisational structures and communication systems using participatory design processes. They highlight a range of information activities such as information encounters, information sharing, information seeking and information needs (Somerville and Howard, 2010) that occurs during the participatory co-design process.

Overall, Godjo, et al. (2015) emphasise that participatory design only works if the design team share information. The significance of sharing information, knowledge, ideas, expertise and experiences in participatory design is also emphasised by Ginige, et al. (2014), Longo (2014), McDonnell (2009) and Skeels (2010). They mostly agree on the need for a supportive environment to facilitate a variety of information activities.

Discussion of findings that can inform an information behaviour study of participatory design in education contexts

In the preceding sections, findings from information behaviour models and the thematic analyses from participatory design in educational contexts and information behaviour studies of participatory design projects were presented. Based on these, we identified nine themes that need to be acknowledged in an information behaviour study of participatory design. In the preceding discussion, we noted finer nuances that need to be incorporated with these themes, but that we will not all address at this stage, e.g. needs and information needs assessment, a variety of intervening issues revealed in Table 1, e.g. trust, intrinsic motivation, involvement, self-expression, sense of excitement and sense of ownership, as well as the iterative nature of participatory design processes, the need for meaning and community and building agency and the importance of domain knowledge. In the discussion to follow, we also refer to earlier findings and the broader body of literature on participatory design per se to strengthen discussion.

Context: Both the literature on information behaviour models and participatory design in educational contexts (cf, Table 1) emphasise the importance to understand the context in which a participatory design project is situated. The design requirements, design needs and design outcomes are related to the context and are directly derived from the participants within or related to that context (Richards, et al. 2014). For example, Bang and Vossoughi (2016) describe participatory design as endogenous design where the intervention and design initiate within a specific context in a field. Apart from the contexts noted in Table 1, insight on the impact of context in participatory design projects can be gained from reports on projects in other contexts, e.g. architecture, urban design, health, computer systems design, psychology, anthropology, human-computer interaction, communication studies, education and information behaviour (Berg, et al., 2013; Hansen, et al., 2015; MacDonald, et al., 2010; Muller and Druin, 2012).

Project purpose and outcomes: It is of great importance for participatory design projects ‘to avoid drifting between ad-hoc user wishes and approvals, and help users get to the core’ of what the purpose, needs and wants are (Bødker and Iversen, 2002, p. 17). The overarching purpose of a project must relate to the context and design needs. The context and purpose of a project determine the selection of stakeholder categories and participating actors. They, again, participate in refining the finer nuances of the purpose and intended outcomes (as explained in a later section). Constant reflection throughout a project can help to keep focus on the overall purpose (Bødker and Iversen, 2002). In Table 1, Cárdenas-Claros (2014), e.g. observes participant selection is based on context and diversity (e.g., language, age, specialisation, profession). The purpose and intended outcomes instigate the needs for the design project as well as information needs which is a crucial trigger for information behaviour, although not always prominently noted in all information behaviour models.

Stakeholder categories and participating actors: As shown in Table 1, choice of participants and participant input are very important and determined by the context, purpose and intended outcomes. There is some ambiguity in the terminology used for participants. Literature on participatory design in educational contexts predominately tends to use the term stakeholders (Cárdenas-Claros, 2014; DiSalvo, et al., 2017a; DiSalvo, et al., 2017b; Hughes and Burns, 2019; Janssen, et al., 2017; Könings, et al., 2017; Simonsen and Robertson, 2012). A few reports on educational contexts, however, instead refer to actors (Brodersen and Pedersen, 2019; Jørgensen, et al., 2011; Vink, et al., 2016). In line with preferences in the information behaviour literature (Ingwersen and Järvelin, 2005; Savolainen, 2016), we will refer to individual participants as actors and representative categories of actors as stakeholders. The selection of both actors and stakeholders should be appropriate to the context and purpose. The actors should allow for diversity in demographics, e.g., age, gender, fields of specialisation, skills, profession and domain knowledge (Frascara, 2017; Lindberg, et al., 2019; Mäkelä and Helfenstein, 2016; Rodil, 2014; Scariot, et al., 2012). These have often been noted to influence information behaviour (Case and Given, 2016). The choice of stakeholder categories is influenced by the types of input required to represent the needs of the design project and purpose. Categories can be based on disciplinary knowledge and skills, e.g., expertise in pedagogics and instructional design, the discipline relevant to the design, e.g., teaching discipline and experiences of, e.g. students or lecturers. An educational, participatory design project can include stakeholders such as students, faculty members and partners/stakeholders from industry. Stakeholder categories can be identified through action research cycles (Zuber-Skerritt, 1992) or stakeholder analysis models (Könings, et al., 2017). Individual actors can be involved in various stakeholder categories, and some stakeholder categories might only make an occasional contribution during specific phases in the design process (e.g. funding procurement from sponsors) (Bergvall-Kåreborn and Ståhlbrost, 2008).

Participant roles and involvement: The selection and involvement of both individual actors and stakeholders are influenced by the roles (and the finer nuances of tasks) featuring in the participatory design project. (Tasks and roles have been noted as very important in information behaviour studies [Byström and Hansen, 2005]). Participants can be involved on various levels, e.g., conceptual level (i.e., idea generation and concept development of, e.g., a system or tool); functional level (i.e., assessment and adaptation of a system or tool according to the project purpose and needs) or operational level (e.g., determining the required capacity of a system or tool) (Barcellini, et al., 2015), or on an informative,consultative andparticipatory level of involvement (Scariot, et al., 2012). Various tools can be used to identify levels of involvement, e.g., a ladder participation tool (Arnstein, 1969), multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) (Marttunen, et al., 2015) or a multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) (United Kingdom Department of International Development [DFID], 2003). Different roles might apply at different project stages such as planning, implementation, observation and reflection (Könings, et al., 2017). Druin (2002) distinguished four roles: users, testers, informants or design partners while Barcellini, et al., (2015), using actual role analysis in design (ARAD), came up with the interactive, group-oriented, task-oriented and production roles.

Participant input (refinement of project purpose and outcomes): In addition to the overarching purpose of a project (set before the selection of participants), selected actors and stakeholders must be involved in the next level of specific decisions. They collaborate on establishing the finer nuances of the project purpose and expected outcomes that determine the design needs and requirements for a project; information sharing, idea and knowledge generation are especially crucial at this stage, as well as iteration (See Conole, et al., (2010) in Table 1). Participatory design strives for clarity of coherent visions, goals and needs during a design project (Simonsen and Hertzum, 2012). Participants can, therefore, consider various design principles and practices as set out in textbooks (da Silveira, 2013; Schuler and Namioka, 2017; Simonsen and Robertson, 2012).

Stages, phases, processes and steps: Participatory design as such can be considered as a process involving a variety of stages and phases (these terms are often used interchangeably) as well as steps, processes and tasks (Penuel, et al., 2007). Work by Ellis (1989) and Kuhlthau (1991) found that project stages and phases influence information behaviour. Typical stages or phases in participatory design projects include: defining a problem and objectives, building relationships, invitations to participants (actors), starting interactions, documentation of ideas and decisions, interacting and involving remote audiences (if applicable), following up and continuing interactions (Korošak, et al., 2018). Some researchers focus more on processes and steps that are either finer detail for stages and phases or used as interchangeable terms for stages and phrases. (These can also be interpreted in terms of tasks that are related to roles.) Axelsen, et al., (2014), for example, refer to evaluation (this can also be a stage or phase), consideration of design theory, development of a design framework and development of a design proposal. The development of a prototype and prototype testing can be included as either a stage, phase or procedure or specific task (Ismail and Ibrahim, 2017). For example, in Table 1, Zaphiris and Constantinou (2007) include the creation, development and evaluation of prototypes in their nine-stage participatory design approach of interactive learning tools for children.

Supportive environment: The success of collaboration and individual and collective growth and idea generation during the participatory design process depends on providing a space that promotes a culture of mutual trust and respect, mutual learning, reflective practices, collaboration, social change and equality and freedom of expression and support for a social constructivist learning environment for growth and development (i.e., a Third Space) (Kang, et al., 2015). Some of these issues are also noted in Table 1. The ideal would be a conflict and domination-free environment where information, knowledge, ideas, expertise and opinions can be shared (Bergold and Thomas, 2012). Information activities such as information and knowledge sharing and trust are critical in making optimal use of such a space. Furthermore, provision of access to a spectrum of public information and knowledge (e.g., access to appropriate tools, technologies, services, information sources, knowledge and skills) is vital for design decision-making. In Table 1, Conole, et al., (2010) mention serendipity as a trigger point in design decision-making. Various information activities can be performed to obtain information such as information seeking (Kuhlthau, 1991), information searching (Ellis, 1989), information encountering (associated with serendipity) (Conole, et al., 2010; Somerville and Howard, 2010) and information sharing (Wittenbaum, et al., 2004). Verbal information sharing is especially important to promote collaboration in participatory design (Ginige, et al., 2014; Longo, 2014; Skeels, 2010).

Appropriate techniques and tools: Techniques and tools are needed for information collection from participants, e.g. workshops, ethnography, cooperative prototyping, mock-ups, card sorting, storyboarding, walkthroughs, organisational visits and six thinking hats (Ishida, 2012; Kang, et al., 2015). Various techniques and tools have been reported for educational contexts to stimulate participation (i.e. stimulation activities) (cf Table 1).

Intervening variables: A broad spectrum of variables have been reported to either support or hinder participation during the participatory design process, e.g., external influences (politicised trust, power relations, cultural capacity and social positioning), internal influences (intrinsic motivations, personal incentive, democracy, mutual learning and cooperation, and system quality and acceptance) and, participants’ perspectives taken during the participatory design process such as pragmatic theoretical or political perspectives. Information behaviour studies also reported on the influence of a variety of intervening variables such as psychological, interpersonal, attitude, feelings and emotions (Fourie and Julien, 2014; Kuhlthau, 1991; Wilson, 1997).

Proposal of a nascent participatory design information behaviour framework

Wilson (1999) denotes that information behaviour models do not all attempt to define the same set of activities or phenomena; various information models represent different aspects and components of information behaviour for specific contexts and situations. Studies on information behaviour in participatory design projects need a framework that uses constructs that have been well argued in the information behaviour literature (Case and Given, 2016; Ford, 2015; Hester Meyer, 2018), as well as constructs evident in frameworks and processes of participatory design (cf. Table 1). This point is fleshed out in an earlier section (Need to move from acknowledgement of information behaviour models to a participatory design information behaviour framework). As has been argued, existing information behaviour models do not adequately accommodate the highly iterative, designerly and creative nature (amongst others) of participatory activities. To keep in line with the participatory design literature, we cited in this paper; we suggest a nascent (i.e., evolving) information behaviour framework (not a model) to be used when studying information behaviour in participatory design projects.

The constructs we envisage for a participatory design information behaviour framework are deducted from the preceding discussion and include the following:

- Context of the participatory design project (the importance of context is well argued in both information behaviour and participatory design literature). The context can be extended to the environment; participatory design projects have been reported to require environments supportive of the creative processes of design and access to information.

- Participants: stakeholder categories and participating actors (these are the people whose information behaviour should be studied).

- Roles, tasks and levels of involvement of participants; in information behaviour, these are normally treated as intervening variables, but due to their prominence in participatory design projects these are suggested as a separate construct for information behaviour studies.

- Information needs; triggered by the envisaged purpose and outcomes of the design project at the start and the project contexts, as well as information needs triggered when participants start giving input on the refinement of the project purpose and outcomes and based on mutual learning and idea generation; the latter is a very important distinguishing characteristic of participatory design.

- Participatory design processes which may include phases/stages/steps and that is marked by their highly iterative nature; although the influence of project phases/stages have been acknowledged in information behaviour research, participatory design processes and what these entail takes a much more prominent role. In fact, research often reports on process models rather than frameworks. Some of these are very detailed and some more abstract, e.g., Tell-Make-Act diagram (Brandt, et al., 2012). Some general steps in the participatory design process could involve: identify research objectives and user groups, background information (conduct interviews and contextual inquiry), analysis and preparation of results of research and presenting to stakeholders, making design recommendations, creating prototypes, testing prototypes, making enhancements to a prototype, and Within the constraints of this paper, we will not deal with the detail; this is for a further project where this key construct of participatory design need to be fleshed out in more detail and aligned more prominently with the constructs of information behaviour. Amongst others, it will be important to note if there is a difference between participatory design project contexts, e.g. education and the participatory design of human-computer interaction.

- Information sources and access; these have been noted as an important construct(s) in information behaviour research, but needs to be considered in more detail when studying information behaviour in participatory design since it has been noted as a core construct supporting idea generation and creativity essential to design projects.

- Information activities, especially information sharing, information seeking, information organisation, serendipitous encountering of information and communication; information activities fall under the umbrella concept of information behaviour. Such activities might be more prominent in participatory design projects due to the very nature of participatory design and the need for information sharing and engagement; further research is required on this aspect before adding detail to the proposed framework.

- Although appropriate techniques and tools are seen as separate construct(s) for participatory design, these also relate closely to information activities. The link between information activities and how techniques and tools can support information activities in participatory design need further research before we can add detail on how this should be positioned as construct in the proposed framework. (It would, e.g., be necessary to establish if there might be differences between techniques and tools used in participatory design in educational contexts and those used in participatory design projects focusing on human-computer interaction.)

- Intervening variables (although there are many such variables, domain knowledge, expertise and prior knowledge stand out).

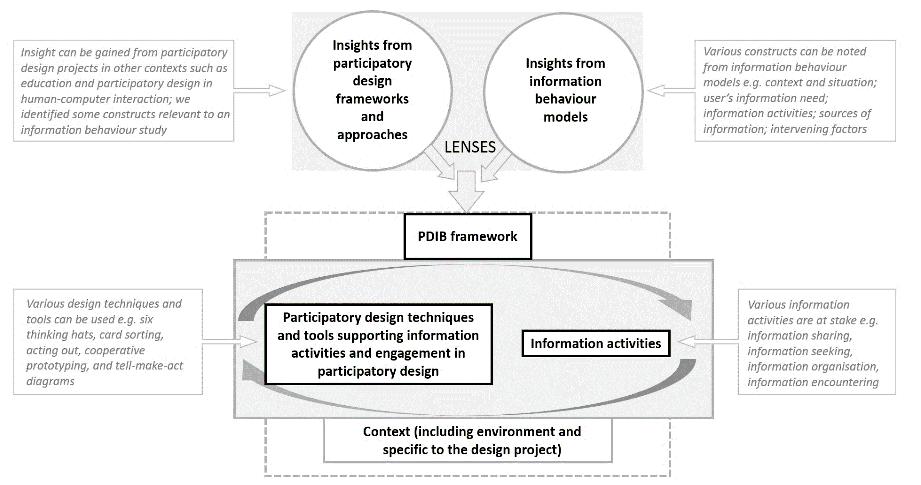

The nascent participatory design information behaviour framework we suggest in Figure 1 takes advantage of the two research areas of (i) a participatory design approach and (ii) insights from information behaviour models and aligns them to suggest a viable tool for participatory design information behaviour studies. On the one hand, we have a set of proposed methods, techniques and tools, and on the other side, we have general information activities. What methods and techniques to use and what information activities that will be involved depend on the context for the information behaviour studies which would also be the context for the participatory design project. The core of the framework is where the methods, techniques and tools are linked to information behaviour activities. The proposed framework is presented in Figure 1 on a general level as an information behaviour lens (the PDIB framework – participatory design information behaviour framework) to study the manifestation, triggers, challenges and intricacies of a spectrum of information activities in a participatory design project. The detail is not specified, based on our arguments when presenting the constructs to feature.

Figure 1: A general nascent participatory design information behaviour (PDIB) framework to inform information behaviour studies of participatory design projects

Conclusion

This paper presented a selection of information behaviour models with their related components as well as findings from participatory design in educational contexts with a focus on frameworks, approaches and processes. The rationale was to identify research lenses that can inform the development of a framework to guide information behaviour studies of participatory design projects. Educational contexts was our exemplar. Our initial findings, however, need to be supplemented with scoping reviews in other contexts such as participatory design in human-computer interaction.

We concluded that studies on information behaviour in participatory design projects require a framework that incorporates constructs from both information behaviour (including information activities) and participatory design (frameworks, processes and techniques and tools that might support information activities and especially engagement; these all need further investigation). The nascent participatory design information behaviour framework we propose reflects work in progress; further work and an exploratory study are necessary to populate the detail of the model. We hope that our model will trigger interest from other researchers in a diversity of contexts. Although we focused on educational contexts, the framework should also be a good point of departure for other contexts. Each of the constructs noted can be investigated in more detail.

About the authors

Anika Meyer is a Lecturer in the Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria. She is currently enrolled for her doctoral studies at the Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria. Her research interests include creativity, collaborative information seeking (CIS), guided inquiry, third space, information literacy, information behaviour and makerspaces - specifically the construction of these creative spaces through universal design, holistic ergonomics and participatory design. Postal address: Private bag X20, Hatfield, 0028, Pretoria, South Africa. She can be contacted at anika.meyer@up.ac.za

Dr Ina Fourie is a Full Professor in the Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria. She holds a doctorate in Information Science and a post-graduate diploma in tertiary education. Her research focus includes information behaviour, information literacy, information services, current awareness services and distance education. Currently, she mostly focuses on affect and emotion and palliative care, including work on cancer, pain and autoethnography. Postal address: Private bag X20, Hatfield, 0028, Pretoria, South Africa. She can be contacted at ina.fourie@up.ac.za

Dr Preben Hansen is a Docent and Associate Professor in Human-Computer Interaction at Stockholm University, Department of Computer Science. Dr Preben Hansen’s research covers two overlapping strands: information seeking and information retrieval and Human-Computer Interaction and Interaction Design and include information search behaviour, collaborative information searching, searching as learning, sustainable design, research through design cross-object interaction, and materiality. Postal address: Department of Computer and Systems Sciences, Stockholm University, Borgarfjordsgatan 12 SE-164 07 Kista, P.O. Box 7003, Sweden. He can be contacted at preben@dsv.su.se

References

- Agarwal, N. (2018). Exploring context in information behavior: seeker, situation, surroundings, and shared identities. Morgan and Claypool.

- Allen, K., Needham, C., Hall, K. & Tanner, D. (2019). Participatory research meets validated outcome measures: tensions in the co‐production of social care evaluation. Social Policy and Administration, 53(2), 311-325. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/spol.12468

- Andersson, N. (2018). Participatory research - a modernizing science for primary health care. Journal of General and Family Medicine, 19(5), 154-159. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jgf2.187

- Arnstein, S.R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Planning Association, 35(4), 216-224. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Axelsen, L.V., Mygind, L. & Bentsen, P. (2014). Designing with children: a participatory design framework for developing interactive exhibitions. International Journal of the Inclusive Museum, 7(1), 1-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.18848/1835-2014/CGP/v07i01/44473

- Bang, M. & Vossoughi, S. (2016). Participatory design research and educational justice: studying learning and relations within social change making. Cognition and Instruction, 34(3), 173-193. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2016.1181879

- Barcellini, F., Prost, L. & Cerf, M. (2015). Designers' and users' roles in participatory design: what is actually co-designed by participants? Applied Ergonomics, 50, 31-40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2015.02.005

- Bates, M.J. (2010). Information behaviour. In Bates, M.J. & Maack, M.N. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Library and Information Sciences (3rd. ed.) (pp. 2381-2391). CRC Press. https://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/bates/articles/information-behavior.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20170312062414/https://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/bates/articles/information-behavior.html)

- Belkin, N.J. (1980). Anomalous states of knowledge as a basis for information retrieval. Canadian journal of information science, 5(1), 133-143.

- Berg, M., Adolfsson, A., Ranerup, A. & Sparud-Lundin, C. (2013). Person-centered web support to women with type 1 diabetes in pregnancy and early motherhood-the development process. Diabetes technology and therapeutics, 15(1), 20-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/dia.2012.0217

- Bergold, J. & Thomas, S. (2012). Participatory research methods: a methodological approach in motion. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung, 13(1), 191-222.

- Bergvall-Kåreborn, B., & Ståhlbrost, A. (2008, October). Participatory design: one step back or two steps forward?. Proceedings of the 10th Anniversary Conference on Participatory Design 2008(pp. 102-111). Indiana University. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.5555/1795234.1795249

- Bødker, S. & Iversen, O.S. (2002). Staging a professional participatory design practice: moving PD beyond the initial fascination of user involvement. Proceedings of the second Nordic conference on Human-computer interaction (pp. 11-18). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/572020.572023

- Brandt, E., Binder, T., & Sanders, E.B.N. (2012). Tools and techniques: ways to engage telling, making and enacting. In J. Simonsen & T. Robertson (Eds.), Routledge international handbook of participatory design (pp. 165-207). Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203108543

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In Cooper, H.E., Camic, P.M., Long, D.L., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D.E. & Sher, K.J. (Eds). APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol 2: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57-71). American Psychological Association. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

- Brodersen, S. & Pedersen, S. (2019). Navigating matters of concern in participatory design. Proceedings of the Design Society: International Conference on Engineering Design, 1, 965-974. Cambridge University Press.

- Bukhari, S., Hamid, S. & Ravana, S.D. (2016). Merging the models of information seeking behaviour to generate the generic phases. Third International Conference on Information Retrieval and Knowledge Management (CAMP)(pp. 125-130). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: IEEE.

- Byström, K. & Hansen, P. (2005). Conceptual framework for tasks in information studies. Journal of the American Society for Information science and Technology, 56(10), 1050-1061. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/asi.20197

- Byström, K. & Kumpulainen, S. (2019). Vertical and horizontal relationships amongst task-based information needs. Information Processing and Management, 57(2), 102065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2019.102065

- Cárdenas-Claros, M.S. (2014). Design considerations of help options in computer-based L2 listening materials informed by participatory design. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 28(5), 429-449. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2014.881385

- Case, D.O. (2012). Looking for information: a survey of research on information seeking, needs and behaviour (3rd. ed.). (Series editor: Amanda Spink). Emerald Group Publishing.

- Case, D.O. & Given, L.M. (Eds.). (2016). Looking for information: a survey of research on information seeking, needs and behavior. Emerald Group Publishing.

- Collis, C., Foth, M. & Schroeter, R. (2009). The Brisbane media map: participatory design and authentic learning to link students and industry. Learning Inquiry, 3(3), 143-155. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11519-009-0046-8

- Conole, G., Scanlon, E., Littleton, K., Kerawalla, L. & Mulholland, P. (2010). Personal inquiry: innovations in participatory design and models for inquiry learning. Educational Media International, 47(4), 277-292. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2010.535328

- da Silveira, D.M.C. (2013). Participatory design and usability: a behavioral approach of workers’ attitudes in the work environment. 15th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction 21 - 26 July 201 Mirage Hotel, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA (pp. 409-416). Springer.

- Danielsson, K., & Wiberg, C. (2006). Participatory design of learning media: designing educational computer games with and for teenagers. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 3(4), 275-291. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17415650680000068

- Dervin, B. (1992). From the mind’s eye of the user: the sense-making qualitative methodology. In J.D. Glazier & R.R. Powell (Eds.), Qualitative research in information management (pp. 61-84). Libraries Unlimited.

- DiSalvo, B. & DiSalvo, C. (2014). Designing for democracy in education: participatory design and the learning sciences. International Society of the Learning Sciences.

- DiSalvo, B., Yip, J., Bonsignore, E. & DiSalvo, C. (2017a). Participatory design for learning. Participatory Design for Learning(pp. 3-6). Routledge.

- DiSalvo, B., Yip, J., Bonsignore, E. & DiSalvo, C. (2017b). Participatory design for learning: perspectives from practice and research. In B. DiSalvo, J. Yip, E. Bonsignore & C. DiSalvo (Eds.), Participatory Design for Learning (pp. 16-21). Routledge.

- Druin, A. (2002). The role of children in the design of new technology. Behaviour and Information Technology, 21(1), 1-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01449290110108659

- Ellis, D. (1989). A behavioural approach to information retrieval system design. Journal of Documentation, 45(3), 171-212. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/eb026843

- Faiola, A. (2007). The design enterprise: rethinking the HCI education paradigm. Design Issues, 23(3), 30-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/desi.2007.23.3.30

- Fang, J. & Strobel, J. (2011). How ID models help with game-based learning: an examination of the gentry model in a participatory design project. Educational Media International, 48(4), 287-306. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2011.632277

- Fidel, R. & Pejtersen, A.M. (2004). From information behaviour research to the design of information systems: the Cognitive Work Analysis framework. Information Research, 10(1), paper 210. http://Informationr.net/ir/10-1/paper210.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200711210452/http://informationr.net/ir/10-1/paper210.html)

- Ford, N. (2015). Introduction to information behaviour. Facet Publishing.

- Foster, A.E. (2005). A non-linear model of information seeking behaviour. Information Research, 10(2), paper 222. http://Informationr.net/ir/10-2/paper222.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20190810140444/http://www.informationr.net/ir//10-2/paper222.html)

- Fourie, I. (2008). Information needs and information behaviour of patients and their family members in a cancer palliative care setting: an exploratory study of an existential context from different perspectives. Information Research, 13(4), paper 360. http://Informationr.net/ir/13-4/paper360.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20190810140556/http://www.informationr.net/ir//13-4/paper360.html)

- Fourie, I. & Julien, H. (2014). Ending the dance: a research agenda for affect and emotion in studies of information behaviour. Proceedings of ISIC, the Information Behaviour Conference, Leeds, 2-5 September 2014, 19(4) 9. http://Informationr.net/ir/19-4/isic/isic09.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20191227031347/http://informationr.net/ir/19-4/isic/isic09.html#.Xw7zAEl7nIU)

- Frascara, J. (2017). Design, and design education: how can they get together? Art, Design and Communication in Higher Education, 16(1), 125-131. http://dx.doi.org/10.1386/adch.16.1.125_1

- Ginige, A., Paolino, L., Romano, M., Sebillo, M., Tortora, G. & Vitiello, G. (2014). Information sharing among disaster responders - an interactive spreadsheet-based collaboration approach. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 23, 547-583. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10606-014-9207-0

- Godjo, T., Boujut, J.F., Marouzé, C. & Giroux, F. (2015). A participatory design approach based on the use of scenarios for improving local design methods in developing countries. (Archived by HAL at https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01206430v2)

- Grant, M.J. & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Greifeneder, E. (2014). Trends in information behaviour research. Proceedings of ISIC, the Information Behaviour Conference, Leeds, 2-5 September 2014, 19(4) 13. http://Informationr.net/ir/19-4/isic/isic13.html(Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20190810142519/http://www.informationr.net/ir//19-4/isic/isic13.html#.Xw72Fkl7nIU)

- Halskov, K. & Hansen, N.B. (2015). The diversity of participatory design research practice at PDC 2002–2012. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 74, 81-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2014.09.003

- Hansen, P., Shah, C. & Klas, C.P. (Eds.). (2015). Collaborative information seeking: best practices, new domains and new thoughts. Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-18988-8

- Hartson, R. & Pyla, P.S. (2018). The UX Book: agile UX design for a quality user experience. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers.

- Hepworth, M., Grunewald, P. & Walton, G. (2014). Research and practice: a critical reflection on approaches that underpin research into people's information behaviour. Journal of Documentation, 70(6), 1039-1053. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JD-02-2014-0040

- Hertzum, M. & Hansen, P. (2019). Empirical studies of collaborative information seeking: a review of methodological issues. Journal of Documentation, 75(1), 140-163. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JD-05-2018-0072

- Hughes, H. & Burns, R.E. (2019). Fostering educator participation in learning space designing: insights from a Master of Education unit of study. School Spaces for Student Wellbeing and Learning(pp. 179-197). Springer. http://dx.doi.org/1007/978-981-13-6092-3

- Ingwersen, P. & Järvelin, K. (2005). The turn: integration of information seeking and retrieval in context. Springer.

- Ishida, T. (Ed.). (2012). Participatory design. In Yamauchi, Y., Introduction to Field Informatics: Kyoto University Field Informatics Research Group (pp. 123-138). Springer.

- Ismail, R. & Ibrahim, R. (2017). PDEduGame: towards participatory design process for educational game design in primary school. 2017 International Conference on Research and Innovation in Information Systems (ICRIIS)(pp. 1-6). IEEE. http://dx.doi.org/1109/ICRIIS.2017.8002540

- Janssen, F.J., Könings, K.D. & Van Merriënboer, J.J. (2017). Participatory educational design: how to improve mutual learning and the quality and usability of the design? European Journal of Education, 52(3), 268-279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12229

- Järvelin, K. & Ingwersen, P. (2004). Information seeking research needs extension towards tasks and technology. Information Research, 10(1), paper 212. http://Informationr.net/ir/10-1/paper212.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20190831221550/http://informationr.net/ir/10-1/paper212.html)

- Jensen, C.M., Overgaard, S., Wiil, U.K., Smith, A.C. & Clemensen, J. (2018). Bridging the gap: a user-driven study on new ways to support self-care and empowerment for patients with hip fracture. SAGE Open Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312118799121

- Johnson, J.D. & Case, D.O. (2012). Health information seeking. Peter Lang Publishing Inc.

- Johnson, J.D., Donohue, W.A., Atkin, C.K. & Johnson, S. (1995). A comprehensive model of information seeking: tests focusing on a technical organization. Science Communication, 16(3), 274-303. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1075547095016003003

- Jørgensen, U., Lindegaard, H. & Rosenqvist, T. (2011). Engaging actors in co-designing heterogeneous innovations. In Culley, S.J., Hicks, B.J., McAloone, T.C., Howard, T.J., Malmqvist, J., (Eds), Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED 11), Impacting Society through Engineering Design, 15 - 19 August 2011 (pp. 453-464). Design Society.

- Jull, J., Giles, A. & Graham, I.D. (2017). Community-based participatory research and integrated knowledge translation: advancing the co-creation of knowledge. Implementation Science, 12(1), 150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0696-3

- Kallio, J.M. (2018). Participatory design of classrooms: infrastructuring education reform in K-12 Personalized learning programs. Journal of Learning Spaces, 7(2), 35-49.

- Kang, M., Choo, P. & Watters, C.E. (2015). Design for experiencing: participatory design approach with multidisciplinary perspectives. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174, 830-833. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.676

- Keshavarz, H. (2008). Human information behaviour and design, development and evaluation of information retrieval systems. Program, 42(4), 391-401. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00330330810912070

- Könings, K.D., Bovill, C. & Woolner, P. (2017). Towards an interdisciplinary model of practice for participatory building design in education. European Journal of Education, 52(3), 306-317. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12230

- Könings, K.D. & McKenney, S. (2017). Participatory design of (built) learning environments. European Journal of Education, 52(3), 247-252. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12232

- Könings, K.D., Seidel, T. & Van Merriënboer, J.J. (2014). Participatory design of learning environments: integrating perspectives of students, teachers, and designers. Instructional Science, 42(1), 1-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11251-013-9305-2

- Korošak, T.S., Zavratnik, V., Kos, A. & Duh, E.S. (2018). Report of participatory tools, methods and techniques. Faculty of Electrical Engineering, University of Ljubljana. https://www.alpine-space.eu/projects/smartvillages/partners-description/smartvillages_181231_co-creation_-d-t3.-1.1.pdf

- Kuhlthau, C.C. (1991). Inside the search process: information seeking from the user's perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(5), 361-371. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199106)42:5%3C361::AID-ASI6%3E3.0.CO;2-%23

- Leckie, G.J., Pettigrew, K.E. & Sylvain, C. (1996). Modelling the information-seeking of professionals: a general model derived from research on engineers, health care professionals, and lawyers. TheLibrary Quarterly, 66(2), 161-193. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/602864

- Lee, H.R., Šabanović, S., Chang, W.L., Hakken, D., Nagata, S., Piatt, J. & Bennett, C. (2017). Steps toward participatory design of social robots: mutual learning with older adults with depression. 12th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, HRI’17, March 6–9 2017 (pp. 244-253). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1145/2909824.3020237

- Lee, J., Ahn, J., Kim, J. & Kho, J.M. (2019). Co‐design education based on the changing designer's role and changing creativity. International Journal of Art and Design Education, 38(2), 430-444. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jade.12204

- Lindberg, M., Johansson, M., & Österlind, H. (2019). Design teams–a participatory path to socially transformative innovation? Forskning og forandring, 2(1), 25-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.23865/fof.v2.1235

- Longo, B. (2014). RU There? Cell phones, participatory design, and intercultural dialogue. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 57(3), 204-215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2014.2341437

- MacDonald, S.L., Winter, T. & Luke, R. (2010). Roles for Information professionals in patient education: Librarians' perspective. Partnership: the Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 5(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v5i1.1153

- Mäkelä, T. & Helfenstein, S. (2016). Developing a conceptual framework for participatory design of psychosocial and physical learning environments. Learning Environments Research, 19(3), 411-440. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10984-016-9214-9

- Marttunen, M., Mustajoki, J., Dufva, M. & Karjalainen, T.P. (2015). How to design and realize participation of stakeholders in MCDA processes? A framework for selecting an appropriate approach. EURO Journal on Decision Processes, 3(1-2), 187-214.

- McDonnell, J. (2009). Collaborative negotiation in design: a study of design conversations between architect and building users. CoDesign, 5(1), 35-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15710880802492862

- McIntyre-Mills, J. (2010). Participatory design for democracy and wellbeing: narrowing the gap between service outcomes and perceived needs. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 23(1), 21-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11213-009-9145-9

- Meyer, A., Hansen, P. & Fourie, I. (2018). Assessing the potential of third space to design a creative virtual academic space based on findings from information behaviour. Proceedings of ISIC, The Information Behaviour Conference, Krakow, Poland, 9-11 October: Part 1. Information Research, 23(4), paper 1814. http://www.informationr.net/ir/23-4/isic2018/isic1814.html. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/74FBUGQyU)

- Meyer, H.W. (2018). Understanding the building blocks of information behaviour: a practical perspective. Innovation: journal of appropriate librarianship and information work in Southern Africa, 56, 24-50.

- Mor, Y. & Winters, N. (2008). Participatory design in open education: a workshop model for developing a pattern language. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2008(1), 12. http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/2008-13

- Muller, M. & Druin, A. (2012). Participatory design: the third space in HCI. In J. Jacko (Ed.), The human-computer interaction handbook (3rd ed.) (pp. 1125-1154). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishing Company.

- Nickpour, F., Dong, H. & Macredie, R. (2014). Information behaviour in design: an information framework. Blucher Design Proceedings, 1(2), 1390-1398.

- Niedźwiedzka, B. (2003). A proposed general model of information behaviour. Information Research, 9(1), paper 164. http://informationr.net/ir/9-1/paper164.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20191211101630/http://www.informationr.net/ir/9-1/paper164.html)

- Parviainen, E., Lagerstöm, E. & Hansen, P. (2016). Compost table–participatory design towards sustainability. Proceedings of the 30th International BCS Human Computer Interaction Conference (HCI 2016)(pp. 1-3). BCS Learning and Development Ltd. http://dx.doi.org/10.14236/ewic/HCI2016.63

- Penuel, W.R., Roschelle, J. & Shechtman, N. (2007). Designing formative assessment software with teachers: an analysis of the co-design process. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 2(1), 51-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S1793206807000300

- Richards, C., Thompson, C.W. & Graham, N. (2014). Beyond designing for motivation: the importance of context in gamification. Proceedings of the first ACM SIGCHI annual symposium on Computer-human interaction in play (pp. 217-226). https://doi.org/10.1145/2658537.2658683

- Rittel, H. (1972). On the planning crisis: systems analysis of the' first and second generations'. Bedrifts Okonomen, 8(1972), 390-396.

- Robertson, T. & Simonsen, J. (2012). Participatory design: an introduction. In J. Simonsen & T. Robertson (Eds.), Routledge international handbook of participatory design (pp. 1-17). Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203108543

- Robson, A. & Robinson, L. (2015). The information seeking and communication model. Journal of Documentation, 71(5), 1043-1069. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JD-01-2015-0023

- Rodil, K. (2014). A participatory perspective on cross-cultural design. Building Bridges: HCI, Visualization, and Non-formal Modeling(pp. 30-46). Springer.

- Roschelle, J., Penuel, W.R. & Schechtman, N. (2006). Co-design of innovations with teachers: definition and dynamics. ICLS '06 Proceedings of the 7th international conference on learning sciences (pp. 606-612). International Society of the Learning Sciences.

- Saad-Sulonen, J., Halskov, K., Huybrechts, L., Vines, J., Eriksson, E. & Karasti, H. (2015). Unfolding participation. What do we mean by participation - conceptually and in practice. Aarhus Series on Human Centered Computing, 1(1), 4-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.7146/aahcc.v1i1.21324

- Savolainen, R. (2016). Conceptual growth in integrated models for information behaviour. Journal of Documentation, 72(4), 648-672. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JDOC-09-2015-0114

- Savolainen, R. (2019). Modeling the interplay of information seeking and information sharing: A conceptual analysis. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 71(4), 518-534. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-10-2018-0266

- Scariot, C.A., Heemann, A. & Padovani, S. (2012). Understanding the collaborative-participatory design. Work, 41, 2701-2705. http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2012-0656-2701

- Schuler, D. & Namioka, A. (Eds.). (2017). Participatory design: principles and practices. CRC Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1201/9780203744338

- Shah, C. (2012). Coagmento: A case study in designing a user-centric collaborative information seeking system. Systems science and collaborative information systems: theories, practices and new research(pp. 242-257). IGI Global. http://dx.doi.org/10.4018/978-1-61350-201-3.ch013

- Shenton, A.K. & Hay‐Gibson, N.V. (2012). Information behaviour meta‐Library Review, 61(2), 92-109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00242531211220735

- Simonsen, J. & Hertzum, M. (2012). Sustained participatory design: extending the iterative approach. Design issues, 28(3), 10-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00158

- Simonsen, J. & Robertson, T. (Eds.). (2012). Routledge international handbook of participatory design. Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203108543

- Skeels, M.M. (2010). Sharing by design: understanding and supporting personal health information sharing and collaboration within social networks. University of Washington.

- Somerville, M.M. & Howard, Z. (2010). 'Information in context': co-designing workplace structures and systems for organisational learning. Information Research, 15(4), paper 446. http://informationr.net/ir/15-4/paper446.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20190811050813/http://www.informationr.net/ir//15-4/paper446.html)

- Spinuzzi, C. (2005). The methodology of participatory design. Technical communication, 52(2), 163-174. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43089196 (Archived by the Internet Archive at link)

- Sulmon, N., Derboven, J., Perez, M.M. & Zaman, B. (2013). Mapping participatory design methods to the cognitive process of creativity to facilitate requirements engineering. Information Systems Research and Exploring Social Artifacts: Approaches and Methodologies(pp. 221-241). GI Global. http://dx.doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-2491-7.ch012

- Taylor, R.S. (1968). Question-negotiation and information seeking in libraries. College & Research Libraries, 29(3), 178-194. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl_29_03_178

- Thinyane, M., Bhat, K., Goldkind, L. & Cannanure, V.K. (2018). Critical participatory design: reflections on engagement and empowerment in a case of a community based organization. Proceedings of the 15th Participatory Design Conference: Full Papers - Volume 1(pp. 1-10). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3210586.3210601

- Torrens, G.E. & Newton, H. (2013). Getting the most from working with higher education: a review of methods used within a participatory design activity involving KS3 special school pupils and undergraduate and post-graduate industrial design students. Design and Technology Education: an international journal, 18(1), 1360-1431. https://ojs.lboro.ac.uk/DATE/article/view/1800/1734 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20190807171559/https://ojs.lboro.ac.uk/DATE/article/view/1800/1734)

- van der Velden, M. & Mörtberg, C. (2015). Participatory design and design for values. In Van den Hoven, J., Vermaas, P.E. & Van de Poel, I. (Eds.). Handbook of Ethics, Values, and Technological Design: Sources, Theory, Values and Application Domains (pp. 41-66). Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6970-0

- Vink, J., Wetter-Edman, K., Edvardsson, B. & Tronvoll, B. (2016). Understanding the influence of the co-design process on well-being. Service Design Geographies. Proceedings of the ServDes. 2016 Conference, May 2016, 125 (pp. 390-402). Linköping University Electronic Press. http://www.ep.liu.se/ecp/125/032/ecp16125032.pdf

- Wilson, T.D. (1997). Information behaviour: an interdisciplinary perspective. Information processing and Management, 33(4), 551-572. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(97)00028-9

- Wilson, T.D. (1999). Models in information behaviour research. Journal of Documentation, 55(3), 249-270. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000007145

- Wilson, T.D. (2010). Fifty years of information behaviour research. Bulletin of the American Society for Information Science and Technology,36(3), 27-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bult.2010.1720360308

- Wittenbaum, G.M., Hollingshead, A.B. & Botero, I.C. (2004). From cooperative to motivated information sharing in groups: moving beyond the hidden profile paradigm. Communication Monographs, 71(3), 286-310. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0363452042000299894

- Yalman, Z. & Yavuzcan, H.G. (2015). Co-Design practice in industrial design education in Turkey a participatory design project. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 197, 2244-2250. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.367

- Zaphiris, P. & Constantinou, P. (2007). Using participatory design in the development of a language learning tool. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 4(2), 79-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17415650780000305

- Zuber-Skerritt, O. (1992). Action research in higher education: examples and reflections. Kogan Page.