Contemporary Chinese parents' needs and questions of parenting for young children: a Web text-mining approach

Huihua He, Si He and Yan Li

Introduction. The current study investigated characteristics of parenting needs and questions of Mainland Chinese parents of young children. Specifically, Web text-mining technology was used to identify themes of parenting needs and questions, and parents' emotional status hidden in their question texts.

Method. Total of 921,483 questions that parents posted from the top five parenting Websites in China during a 36-month study period were collected.

Results. Daily care is one of the most important topics that concerned parents. Contemporary Mainland Chinese parents tend to raise questions about parental knowledge and skills. Different themes of questions could also be identified from different care-givers and different age groups of young children.

Conclusions. From a parenting-oriented perspective, contemporary Chinese parents asked pesonalised questions through the Internet frequently. The considerable needs of grandparenting emerged. Programme designers and social policy makers should empower and support young children's parents with their parental knowledge, skills and emotional competence.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper877

Introduction

The number of Internet user in China has reached 802 million until June 2018. The average online time is 27 hours per person per week, and about 231 minutes per day (CNNIC, 2018). Internet social technology including social applications on mobile devices have become an effective way of communication, information exchange, making friends and achieving social support (Jang, et al., 2017 ). According to Esarey and Qiang (2011), the total aggregate daily page views reached 1 billion, with 10 million new Web texts being posted every single day in Mainland China. Through online social technology, Internet users can ask questions, search information and solutions to their problems, interact with others, share life experience and achieve social support (Gang and Bandurski, 2011). Parents could be a very active group of Mainland Chinese netizens, especially new parents with young children. Generally, parents use the Internet for searching information on parenting issues and education policies, consulting expert advices, storing pictures and documents, maintaining family-school relationship, and pursuing social support (Zeng and Cheatham, 2017). Previous studies have suggested that parents' Information and Communication Technology (ICT) use can positively affect parenting outcomes and strengthen parents' social capital gradually (Rudi, et al., 2015; Jang and Dworkin, 2014).

Questioning is one of the important purposes of Mainland Chinese parents to use the Internet social technology. They raise their own parenting issues and seek answers from other parents or experts. At the same time, parents can also discuss the topic of parenting in the process of mutual communication. Although the accuracy of the questions has not been verified, studies have shown that parents generally trust the answers and responses they receive from other parents based on their own parenting knowledge and experience (Harvey, et al., 2017). Researchers also suggested that parents with younger children are more likely to go online searching for the information and support they need (McDaniel, et al., 2012). Since parents are usually posting their questions initiatively and promptly, Web texts posted by Mainland Chinese parents on the Internet can reflect their or their families' parenting needs and problems precisely. Therefore, analysing questions that parents posted online could be an accurate and effective way to understand parents' needs and concerns, and could also be valuable for parent programme design and policy development.

Previous research on the needs of parents usually employ questionnaires or interviews to ask parents to report their parenting questions and needs (Rawlins, et al., 1990). Only limited numbers of participants can attend the study which could cause generalisability problems. Web text-mining technology can overcome limitations of traditional methods and provide more reliable results (Liu, et al., 2017). Therefore, this study will use Internet text-mining approaches to explore the characteristics of parents' questions proposed on the Internet social platform from different dimensions. There are two research purposes: (1) to achieve a convincing understanding of contemporary Mainland Chinese parents' needs and questions, and (2) to provide more reliable suggestions for policy making and educational resources allocation. Specifically, the current study will focus on Mainland Chinese parents of 0-6 year old children since they are heavily reliant upon Internet social applications. Web texts analysis will be conducted from the following aspects: (1) most frequent meaningful words in parents' questions; (2) themes of parents' questions; (3) questions from different care-givers; (4) questions regarding different children's age group; and (5) emotional expressions when parents' posted the questions online.

Literature review

Parent Internet use

According to previous research, parents usually go online for multiple purposes, such as information-seeking, online purchasing, communication with others, and documents storage (Zeng and Cheatham, 2017; Rudi, et al., 2015; Jang and Dworkin, 2014). ICT use is one of the most popular method. For instance, parents tend to use email newsletters and online classes from professionals to seek reassurance about their parenting practices (Jang, Dworkin and Hessel, 2015). Parents prefer more interactive applications for communication such as forum or discussion boards to discuss their children's potential problems, maintain social relationships, consulting advice and to exchange social support (Ammari and Schoenebeck, 2015; Morris, 2014; McDaniel, et al., 2012). For example, posting and commenting on blogs could be a frequent approach for parents to communicate with their family members and friends (Kennedy, et al., 2008; Doty and Dworkin, 2014; Bartholomew, et al., 2012). Parents also use online tools for managing personal documents and record their children's anecdotes (Kumar and Schoenebeck, 2015; Dworkin, et al., 2013). One of the most popular parent forum of Mainland China is babytree.com which had attracted more than 9.2 million registered users by 2012 (Jang and Dworkin, 2014). This Website reaches 80% of all online mothers from pregnancy to those with 0-6-year children in Mainland China.

Each ICT holds different features which can satisfy parents' individualized needs. For example, parents of a newborn baby tend to ask parenting questions on nurturing practices through virtual communities and discussion boards including parent blogs (Gibson and Hanson, 2013; Hall and Irvine, 2009). Moreover, research findings indicated an increasing reliance on the Internet as an important information source for parents of children with disabilities, especially for health- and education-related issues (Zeng and Cheatham, 2017). Parents search information through the Internet to reduce their anxiety about their children's special needs. Children's medical and educational needs were coped with through the Internet by their parents more often than going to see their paediatricians (Kostagiloas, et al., 2013). For instance, parents reported that online health and educational information were more up-to-date, quicker and easier to access than offline information (Sillence and Briggs,2007).

This type of online information exchange and support is also valuable for other care-givers of young children in the family (Baker, et al., 2016). For instance, research found that mothers would receive parenting information, emotional support and a sense of belonging in the community, while fathers can receive knowledge, skills and support about fatherhood. Fathers would have better understanding about fatherhood and were encouraged to take responsibilities of parenting. Positive and informational texts received from other family members, friends or other parents could improve parental knowledge, skills and efficacy (Suzuki, et al., 2009).

Although parents would initially choose the ICT applications they believe most comfortable and appropriate to their situation, the quality of online information provided by both search engine and social tools is questionable (Rudi, et al., 2015). Little is known about the accuracy and appropriateness of the information and generally Internet information is not reviewed or approved by experts or professional organisations before being available for parents (Zaidman-Zait and Jamieson, 2007). Parents have different capabilities to judge the quality of Internet information. Research findings of parents both trusting and mistrusting online parenting information coexist in the literature (Walsh, et al.,2015).

In addition, parents' emotions could be affected by the Web texts they were reading (Zeng and Cheatham, 2017). Stern, et al. (2012) found that mothers of children with disabilities or diseases are likely to feel anxious after they use the Internet for information-seeking. One reason could be that online resources or answers from other users contained contradictory advices. Another reason could be just their questions remained unanswered for a long time, which made parents feel stressed and nervous about their children's conditions. However, other studies found that parents' online behavior can also reflect parents' emotions. For example, emotional expressions were always found in the Web texts of online social platforms, such as parents' blogs, especially for single-mothers and care-givers with special needs (Zhao and Basnyat, 2018). For instance, financial concerns and stress from nurturing young children could affect single-mothers' self-esteem negatively. Parents could express their concerns and emotional status clearly or covertly while posting online messages. Research has indicated that care-givers with special needs could achieve social support including information support, emotional support and tangible support. ICT use could be valuable for parents with low socioeconomic status to relieve loneliness, increase self-confidence and navigate legal services.

Parenting needs and questions

Comparatively less research has been conducted to investigate parenting needs of young and typical or normal children. Some of them focused on parent education needs, such as types of parent education (Jacobson and Engelbrecht, 2000). Researchers also found that knowledge about creative development, observation techniques, social development, safety and first-aid, and methods to simulate education motivation could be high-ranked needs that parents reported (Chung, 1993). Brady (2010) sought to explore the needs of parents with normal children age 4 to 5 years, in relation to a parent education programme. The study concludes that parents believed that a high-quality education programme should provide them with supporting children's academic progress, how to improve parent-child relationship, how to encourage appropriate social interaction, and how to discuss topics such as discipline with other parents in their community.

Most researchers have focused on parents' needs of children with special needs, such as disabilities or having health problems (Dworkin, et al., 2013; Gowen et al., 1993; Harvey, et al., 2017 2017). Adler, et al. (2015) conducted a content analysis of 48 publications focusing on the knowledge needs of parents with sick children. Results indicated that parents' knowledge needs could be categorised into 9 categories: (1) knowledge about the condition or illness; (2) support (support groups, peers, policies and regulations, and financial support), (3) treatment (treatment plan and results, medical information, and operation techniques), (4) everyday care (children's behavior handling and reduction of consequences of disease), (5) the future (children's development delay, social development, education of the child, and life expectancy), (6) how to explain the illness to others, (7) equipment (technique equipment, information of obtaining appropriate aids), (8) organizational issues, and (9) the effect of the illness on the family. Results of this study also suggested that parental needs varied greatly between the families, individuals and changing over time.

Ji, et al. (2018) assessed the needs of parents of children with special health care needs in Mainland China. Four groups of needs had been reported including informational needs, emotional needs, practical needs and psychosocial needs. Informational needs could be a full explanation of tests or treatments procedures, benefits and side effects of treatments, and ways to help the child get well. Emotional needs could be how to deal with anxiety and stress and how to cope with a suffering child and frustration. Practical needs could be coping with house work and disruption of usual routine. Finally, psychosocial needs could be working with the family's fears and worries, children's social acceptance and coping with changes in other people's attitudes and behavior towards the child. Other types of needs could be spiritual needs and physical needs of parents (Kerr, et al., 2007).

Instruments used to examine parents' needs include survey, questionnaire, personal interview or focus group. Researchers either use pre-existing instruments or developed purposive instruments for their study. For example, Family Needs Survey was developed by Bailey and Simeonsson (1988) to document family needs for the purpose of planning early intervention programmes. The survey includes 35 items and has six subscales including information needs, support needs, explanation needs, community service needs, financial needs and family functioning needs. A few studies have employed this survey and reported that six factors explained 55% of the total variance (Ellis, et al., 2002; Graves and Hayes, 1996; Adler, et al., 2015).

Furthermore, assessment of needs, interests, and service preferences is important for programme planning for parents at every stage. Parents' interests in information topics, their problems related to parenthood, their attitudes and values regarding child rearing and their awareness, use or needs of various sources of support could be measured and clarified by an extensive assessment process (Gowen, et al., 1993). For instance, Lee, et al. (2016) have conducted a needs assessment to examine the availability of parenting support services to fathers. Results indicated that parenting programmes for fathers should be provided, and should especially recruit fathers of young African Americans. Fathers also reported their service needs such as employment supports, navigating the child support system, co-parenting relationship support and positive fatherhood mentorship.

Research questions

The entire constellation of needs encountered by parents has not been studied, especially for Mainland Chinese parents. In addition, survey, interview or other traditional methodology of needs assessment have inherent limitations including limited response choices and generalisability issues. Research has yet to investigate parents' parenting needs by analysing Internet data, such as Web texts including parents' messages posted on Internet social media. However, previous research has indicated that Internet social platform should be a very convenient and effective way to ask parenting questions and share parenting needs for parents worldwide, including contemporary Chinese parents. Thus, this study aims to investigate contemporary Chinese parents' parenting needs of 0-6-year old children by Web text-mining technologies. The following research questions were asked:

- What are the primary themes of parental needs of Chinese parents with young children?

- What are parenting needs of different care-givers, and at different age stages?

- What are parents' anxiety level in different categories of parenting need?

Methods

Data source

The current study collected total of 921,483 questions that parents posted from the top five parenting Websites in China during a 36-month study period from November 2014 to October 2017. More specifically, first we entered child care (育儿), mother and baby (母婴), early parenting (早期教养), family and parents (家庭早教、家长), early education (早教) and baby nurturing (婴幼儿照护) into Chinese Web search engines, such as Baidu and searched for Websites about parenting of young children. Secondly, experts from early education and parenting field selected five sites with the highest rates of use according to Website content (see Table 1). Finally, a Web crawler was developed and texts of parents' questions were extracted from the discussion board of these Websites.

The data set comprises of the question texts that were collected from the selected Websites by our Web crawler. There were 59,147 unique users and 921,483 questions identified during the 36-month research period. Each user ID was asked about sixteen questions on average. The number of questions that top ten active users posted were 290, 202, 202, 192, 190, 176, 162, 151, 151, 141. The median number of questions raised by each user was five and the interquartile range was three to twelve. Each question text in the data set includes three attributes: user ID of information seekers, time-stamp of question, and the content of question raised by the information seekers.

| Website | URL | Web page selection | Description of parents' questions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Babyspace | http://www.0-6.com/ | consumption zone, interactive communication zone, parenting knowledge question and answer | questions are classified according to age and domain, questions are marked whether it has been answered or not, each question contains: questions, questioner's ID, time and answers; |

| Babytree | http://www.babytree.com/ | parenting knowledge question and answer, social forum activity area, shopping zone | questions are classified according to age and domain, questions are marked whether it has been answered or not, each question contains: questions, questioner's ID, time, answers, and the best answer; |

| Yaolan | http://www.yaolan.com/ | knowledge column, forum community, question and answer area, shopping zone | questions are classified according to age, each question contains: questions, questioner's ID, time, answers, and mark the best answer |

| Child care network | http://www.ci123.com/ | question and answer area, community forum, parents blog, mother and child's shopping center | questions are classified according to age and domain, questions are marked whether it has been answered or not, each question contains: questions, questioner's ID, time, answers and the best answer |

| Baby knows | https://baobao.baidu.com/ | question and answer area, community forum | there is no classification of questions, each question contains: questions, questioner's ID, time, answers and the best answer |

Data analysis

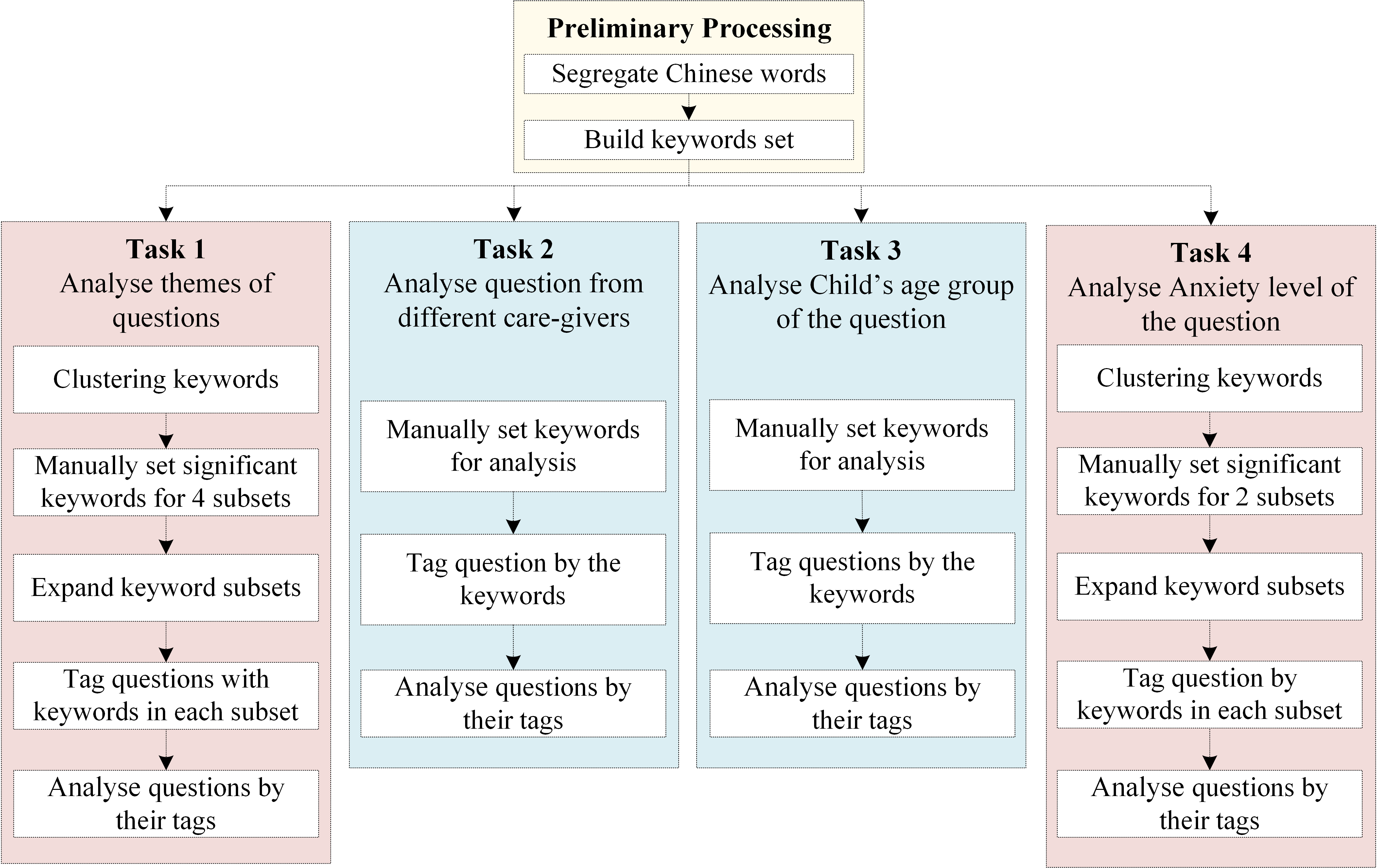

text-mining is a process that derives high-quality information or meaningful patterns from text materials, involving activities, such as information retrieval, lexical analysis and information extraction. In the current study, text-mining method was used to analyse questions that were posted online publicly by Chinese parents. Four tasks were conducted in the data analysis process, which are (1) themes of questions, (2) different care-givers who proposed the questions, (3) different age groups that questions concerned, and (4) anxiety level of the questions. The overall process was shown in Figure 1.

In order to analyse question themes and the anxiety level of the questions (i.e., Tasks 1 and 4), contemporary text-mining technology was employed first to help recognise all the keywords from the question set that is too large to handle manually. Then the keywords were used to tag all the questions iteratively by a Python program. In order to analyse questions from different care-givers and age groups (i.e., Task 2 and 3), the keywords were first set manually, then each question tagged directly with these keywords by a Python program. After finishing tagging every question, they were classified by the keywords that were marked on them.

Preliminary processing. Firstly, all question texts were segregated at morpheme level (i.e., the smallest grammatical unit in a language). Since the text being analysed is Chinese, word segregation was conducted by HanLP after cleaning the data set. As a result, the useful words were ready for next step. These words are nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs which can represent meaning of the corresponding sentences.

Secondly, keywords set was built. A term frequency, inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) algorithm is used to identify the keywords in each sentence (Salton, 1988). This algorithm scores the importance of words in a document based on how frequently they appear across multiple documents. If a word appears frequently in a document, it is deemed as important. Here, it is called a keyword. If a word appears in many documents and it is not a unique identifier, it is given a low score. Therefore, common words like the and for which appear in many documents, will be scored down. Words that appear frequently in a single document will be scored up, and all the identified keywords will be put together to generate a keywords set.

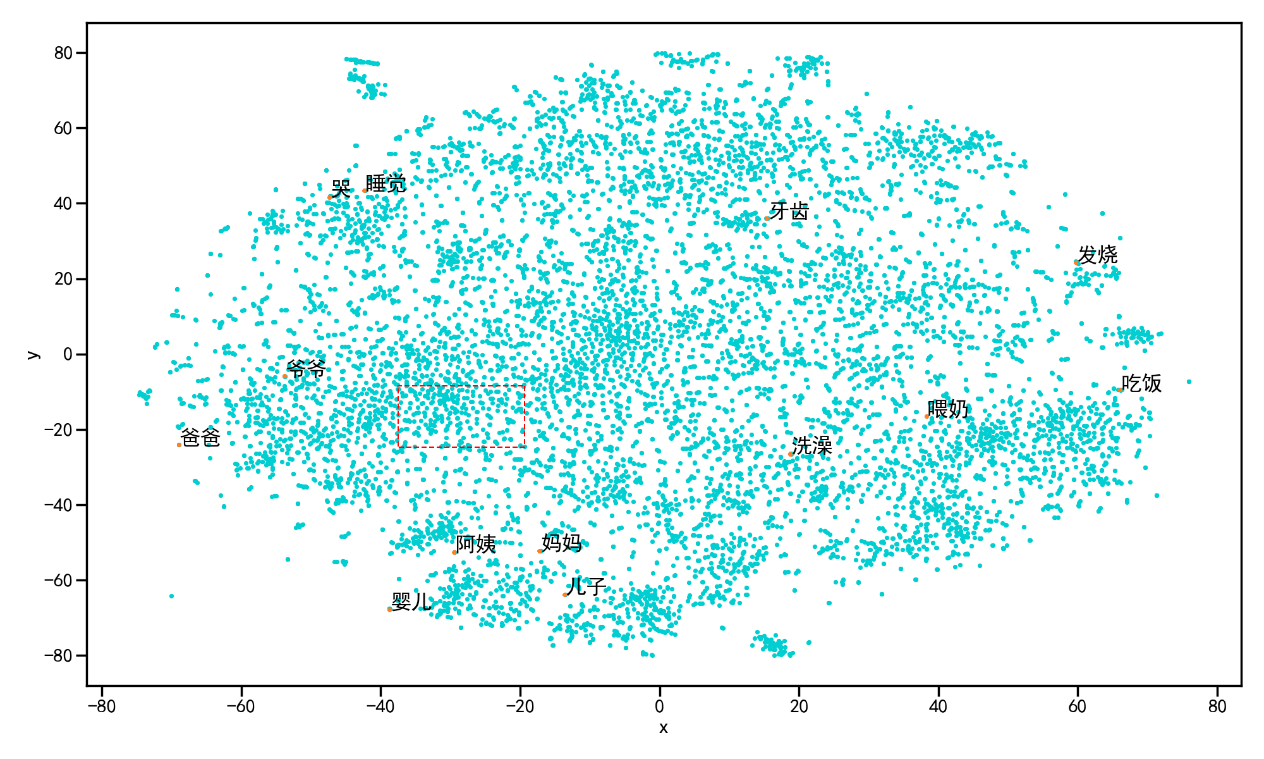

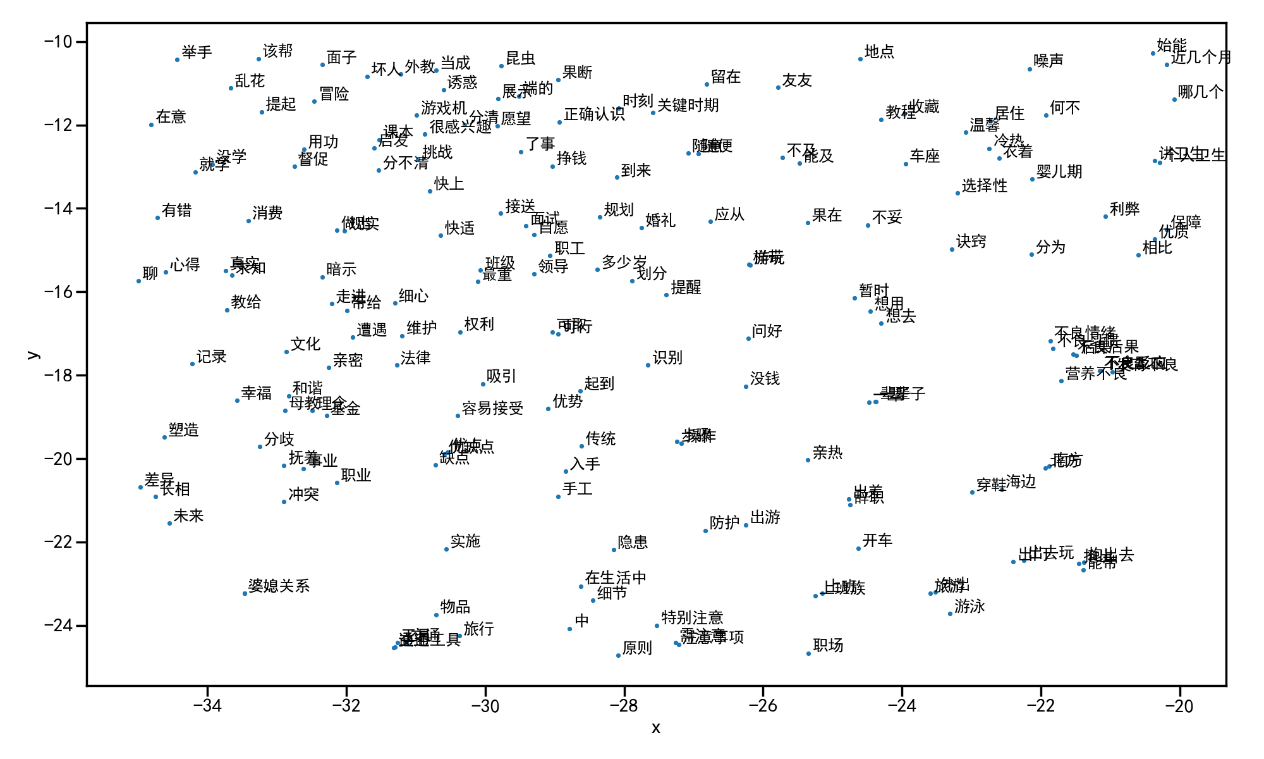

Analysis for Task 1 and 4. Firstly, keywords subsets were identified and initial keywords of each subset were determined. To classify the keywords set obtained in previous step, word vector space model (Salton, 1974) and K-means clustering algorithm were adopted (MacQueen, 1967). Vector space models represent a word in a K dimensional vector of a continuous vector space where semantically similar words are mapped to nearby points. Based on the question text that was obtained from previously mentioned websites, Word2vec, (a computationally efficient predictive model for learning word embeddings from raw text), was used to get the word vectors for each keyword (Mikolov, et al., 2013). Word vector visualization samples are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Figure 2 shows visualized vectors for 10,000 sample words in our question library. Each point in this figure is corresponding to a Chinese word. The distance between points denotes a 2D mapping of their high-dimensional semantic relationship. This mapping was achieved by distributed stochastic neighbour embedding (t-SNE), which is an unsupervised, non-linear technique primarily used for data exploration and visualizing high-dimensional data. Figure 3 shows the local details for the red area in Figure 2.

According to our best classification results in the experiments, a sixty-dimensional vector was used as an input for the K-means clustering in the current study. In this step, clustering experiments on 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 initial means were conducted. Results of all the five clustering experiments are not satisfactory, there were always some unrelated words grouped together. Nevertheless, it was found that many words with obvious similar meaning were clustered successfully. For task 1, according to the common meaning expressed by the clustered keywords groups, the researchers found that six groups can best represent the category feature of the whole keywords set. They are named by the researchers as parenting knowledge, parenting skills, parent-child relationship, parenting efficacy, pregnancy maternity care and foetal development For Task 4, the authors specify two keywords groups, one is for high anxiety and another is for low anxiety (Table 2). For each group, keywords were manually picked that best fit it to be the initial words, some of which are shown in Table 2.

| Tasks | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Task 1 Themes of the question | eating, sleeping, formula, bathing, milk feeding, bathing, diaper, teeth, crying |

| Task 4 Anxiety level of the question | hurry, really anxious, anxiously |

Secondly, keyword subsets achieved by the previous step were expanded. After six keyword subsets were found for Task 1 and 4, all the keywords are converted to word vectors by using word2vec. Let W be the word vector array containing word vectors Wi of each word in the keyword subsets, W= (W1, W2, …Wi, …Wn). Let V be the array containing all word vectors Vi of keywords which are not in the six keyword subsets, V= (V1, V2, …Vi, …Vn). We iteratively compare each Vi with each Wi. If Vi are determined to match Wi, then the corresponding word for Vi is categorised into the subset of Wi. For example, if word vector of aunt is judged as matching to the word vector of mother, since mother is a keyword of the Question from different care-givers group, then aunt is added into this group.

The similarity between two word-vectors is determined by a measure of similarity, cosine similarity. This measure computes the cosine of the angle between vectors Vi and Wi. A cosine value of 0 means that the two vectors are orthogonal to each other and have no match. The closer the cosine value to 1, the smaller the angle and the greater the match between vectors. Let Vi = (v1, v2, v3, … vn), Wi= (w1, w2, w3, … wn), the similarity calculation between them is shown in the following.

simcosine(Vi,Wi) = (Vi∙Wi) / (||Vi||∙||Wi||) = ∑i(Vi∙Wi)/√(∑iVi2∙∑iWi2) (1)

where ||Vi|| is the Euclidean norm of vector Vi, defined as √(v12+v22+v32 ), i.e., the length of the vector. Similarly, ||Wi|| is the Euclidean norm of vector Wi. If simcosine(Vi, Wi) is greater than a threshold value T, we say Vi matches Wi. To get the best classification result, the threshold value T is 0.6. This value is chosen after many experiments. If the threshold is set too high, most related words will probably be ignored. Nevertheless, if the threshold is set too low, the irrelevant words would be mistakenly classified. After comparing each Vi with each Wi, all the similar keywords are clustered into these six subsets. In another word, these subsets are now expanded.

Thirdly, keywords in the expanded subsets were used to annotate all questions. In this step, the authors use the keywords in the expanded subset to tag all the questions. If a question text contains a keyword in a subset, then the question is marked with this keyword. As described in the previous step, the subset that this keyword belongs to is corresponding to a specific category, thus, this question is treated as belonging to this category when further result analysis was conducted. After tagging all the question with all the possible keywords, the tagged question set were stored in a database. Finally, as all the questions in the database have now been marked with different keywords, they can easily be classified for further research by checking the keywords each question bears.

Analysis for Tasks 2 and 3. First, keywords used for these two tasks were determined. Researchers manually selected the keywords that best represent the subjects because the keywords for these two tasks are clear and limited. The keywords are shown in Table 3. Secondly, keywords were used to annotate all the questions. As a result, each question has assigned all the possible keyword tag that denote its feature. Finally, we can easily classify questions for further research according to their tags.

| Tasks | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Task 2 Question from different care-givers | mother, mom, father, dad, grandparents, grandpa, grandma, nanny, aunt |

| Task 3 Questions from different age groups of children | age, month, newborn |

Results

Word frequency analysis

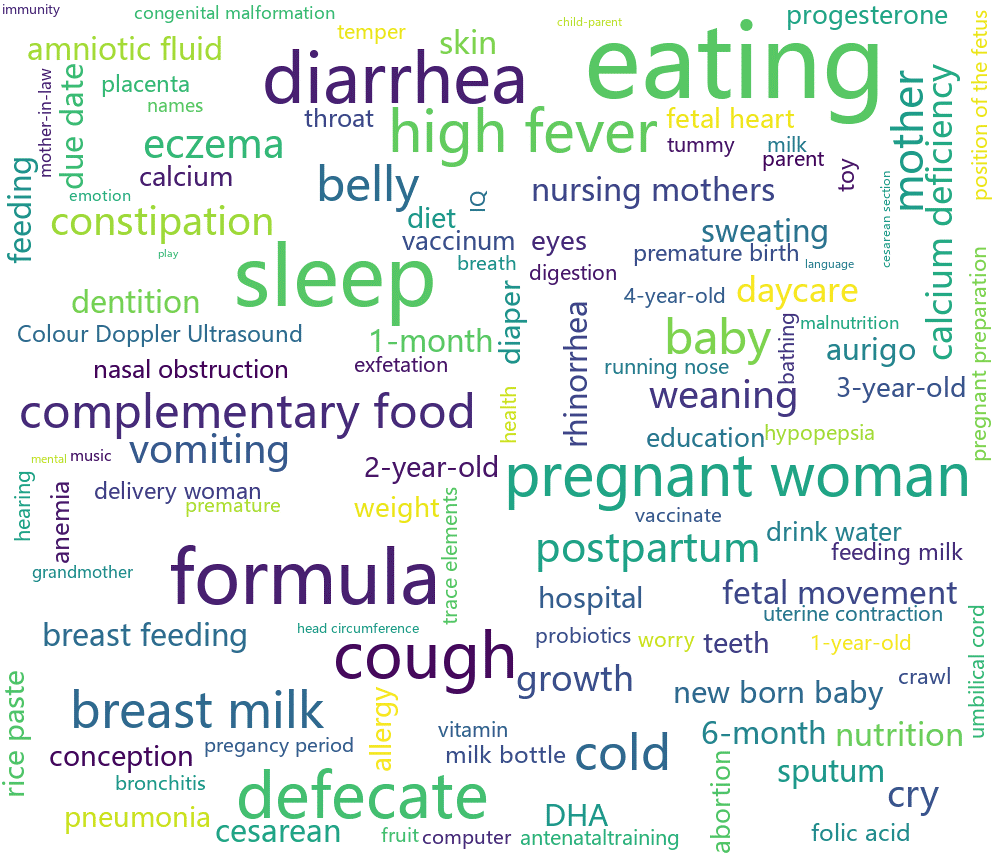

The top 100 frequently used words were extracted from parents' questions. Word clouds were generated to depict the frequent keywords visually (see Figure 4). The top ten frequent words were eating, sleep, formula, diarrhea (diarrhoea), cough, defecate, high fever, breast milk cold and belly. Results suggested that parents are more likely to ask questions regarding young children's daily care and common diseases. In other words, Mainland Chinese parents of young children do not have sufficient hands-on experiences or scientific knowledge supporting their care-giving behaviour. They tend to propose more questions regarding young child's daily routine and healthy issues on the Internet.

Themes of parents' questions

Themes of questions. Parents' questions were clustered into six prevalent themes and were fetched for further content analysis. The identified themes could be categorised into two broad categories, which were parenting and pregnancy. The number of questions in the parenting category were 683,626 (74.19%) while the number of questions in the pregnancy category were 237,857 (25.81%). There were four themes in the parenting category, which were parenting knowledge, parenting skills, parent-child relationships and parenting efficacy. Themes in the pregnancy category were pregnancy maternity care and foetal development. Descriptive statistics for all questions and their themes are reported in Table 4.

| Categories of themes | Themes of the questions | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting | Parenting knowledge | 376,156 | 40.82 |

| Parenting skills | 259,109 | 28.12 | |

| Parent-child relationship | 1,747 | 0.19 | |

| Parenting efficacy | 46,614 | 5.06 | |

| Subtotal | 683,626 | 74.19 | |

| Pregnancy | Pregnancy maternity care | 159,492 | 17.31 |

| foetal development | 78,365 | 8.5 | |

| Subtotal | 237,857 | 25.81 | |

| Total | 921,483 | 100 | |

Results suggested that questions that parents were most likely to ask are topics of parenting knowledge. The least amount of questions were topics of parent-child relationships. Parents were more interested in questions about knowledge on young children's development and daily nurturing behaviour, which was consistent with the results of word frequency analysis. For example, parents may ask When does the baby start to have the very first teeth? and What should I do if my baby has a high fever?. Within the pregnancy category, prenatal mothers were more likely to consult information on maternity care, such as How many times does the foetus move a day? and When should I to do the Color Doppler Ultrasound?.

Themes from different care-givers. To explore themes of the parenting category proposed by different care-givers, caregiver information in questions was extracted by our tool. Four different care-givers were identified which were children's mother, father, grandparents and others. Other care-givers refer to nanny, aunt, uncle and others. Only 11,279 (1.2%) questions contain caregiver information which can be recognised by our tool explicitly. Results suggested that most questions proposed on the Internet did not only refer to one specific caregiver in the contemporary Chinese family with young children. In detail, the number of questions labelling mothers (74.55%) was higher than questions labelling both grandparents (20.52%) and fathers (3.59%). Results suggest that grandparents had undertaken more nurturing responsibilities than children's father.

Table 5 reports descriptive statistics of questions in different themes from different care-givers. Questions proposed by children's mothers generally focused on parenting knowledge while questions proposed by fathers focused on parenting skills. Grandparents were more likely to propose questions about parent-child relationships and parenting skills. For example, questions regarding grand-parenting could be How to play with baby? or How to bath the newborn baby?.

| care-givers | Question themes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All themes | Parenting knowledge | Parenting skill | Parent-child relationship | Parenting efficacy | ||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Mother | 8409 | 74.55 | 4773 | 56.76 | 3074 | 36.56 | 52 | 0.62 | 510 | 6.06 |

| Father | 405 | 3.59 | 70 | 17.28 | 292 | 72.11 | 18 | 4.44 | 25 | 6.17 |

| Grandparents | 2315 | 20.52 | 314 | 13.56 | 814 | 35.16 | 1062 | 45.87 | 125 | 5.41 |

| Others | 150 | 1.34 | 85 | 56.67 | 54 | 36.00 | 1 | 0.67 | 10 | 6.66 |

| Total | 11279 | 100 | 5242 | 46.48 | 4234 | 37.54 | 1133 | 10.05 | 670 | 5.93 |

Themes from different age groups. To explore the themes of parenting questions proposed for different age groups of young children, the study extracted the age information from each question and organised questions according to the age of young children. Four age groups were emerged: 0-12 months, 13-24 months, 25-36 months, and 37 months and above. Results indicated that a total of 151,661 questions having information of young children age. In detail, there were 123,290 children aged 0-12 months, 9,896 children aged 13-24 months, 8,191 children aged 25-36 months, and 10,284 children aged above 37 months. It could be suggested that the number of questions decreased while children are growing up before three years old but could increase after age three in which children's developmental needs and parents' questions have been changing.

Descriptive statistics of questions in each theme from different age groups was reported in Table 6. Results indicated that during the 0-12 month's stage, parents raise more questions in the themes of parenting knowledge, such as How to get newborn baby to sleep?. Parents were more concerned about questions regarding parenting skills when young children were 13-month old and above. For example, parents may ask questions like When should I add complementary food? and Is it normal for my baby to chewing pacifier while sleeping?.

In addition, results indicated that parents rarely proposed questions about parent-child relationships in any age groups. It is suggested that parents are confident with their parent-child relationships when their children were very young, or the importance of parent-child relationships was not recognised by Chinese parents of young children.

| Age groups | Question themes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All themes | Parenting knowledge | Parenting skill | Parent-child relationship | Parenting efficacy | ||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 0-12 mon | 123290 | 81.29 | 67675 | 54.89 | 44796 | 36.48 | 164 | 0.13 | 10475 | 8.50 |

| 13-24 mon | 9896 | 6.53 | 4108 | 41.51 | 5116 | 51.70 | 53 | 0.53 | 619 | 6.26 |

| Grandparents | 8191 | 5.40 | 3496 | 42.68 | 4244 | 51.81 | 33 | 0.41 | 418 | 5.10 |

| Others | 10284 | 6.78 | 3865 | 37.58 | 5912 | 57.49 | 33 | 0.32 | 474 | 4.61 |

| Total | 151661 | 100 | 79144 | 52.18 | 60248 | 39.73 | 283 | 0.19 | 11986 | 7.90 |

Themes of pregnancy and maternal issue. The total number of pregnancy and maternal questions are 237,857 (25.81%). Two different themes were identified in this category which are pregnancy maternity care and foetal development. 159,492 questions were included in the pregnancy maternity care theme, accounting for 17.31% of the total. The number of foetal development questions in pregnancy is 78,365, accounting for 8.5% of the total.

Comparing with the number of questions related to foetal development during pregnancy, pregnant women are more likely to ask questions related to their own health care during pregnancy. Results also indicated that parents have started to concerns about parenting issues before their child's birth. For example, pregnant women may ask questions like Is it normal for a pregnant women to have backache? and Is it useful to listen to classic music when I pregnant?.

Anxiety level reflected from parents' questions

Sentiment analysis was yielded to analyse the level of anxiety of parenting questions by analysing emotional words contained in the question. Not all questions contained emotion words that our tool can recognise but most of them could be identified. For those questions containing emotion words which were extracted by our tool, questions are assigned into either high anxiety or low anxiety categories. Emotion words which were labeled as high anxiety could be hurry, very hurry, anxious and very anxious. Emotion words which were labeled as low anxiety could be what or how to do, what are the reasons, and want it or not.

Results suggested that generally the anxiety level reflected from parents' questions was relatively low. Although some parents felt anxious when they proposed their questions on the Internet, most of them have a positive attitude towards their parenting practice. More specifically, the anxiety level reflected from questions regarding themes of parenting knowledge and foetal development is higher than other themes. For example, parents' questions could be 'Waiting online, hurry, what I should do if my baby do not want my breast feeding?. Questions regarding parenting efficacy, parent-child relationship and grandparents' issues, shows the lowest level of anxiety (Table 7), such as What my husband can play with my 2-year-old daughter? and My 1-year-old son has very good relationships with his grandma, but when should grandparents stop sleeping with my son?'.

| Different themes | N | High anxiety | Low anxiety | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Parenting knowledge | 376,156 | 8,572 | 2.28 | 200,719 | 53.36 |

| Parenting skills | 259,109 | 5,724 | 2.21 | 241,665 | 93.27 |

| Parent-child relationship | 1,747 | 19 | 1.09 | 1,017 | 58.21 |

| Parenting efficacy | 46,614 | 468 | 1.00 | 40,906 | 87.75 |

| Pregnancy maternity care | 159,492 | 2,458 | 1.54 | 99,696 | 62.51 |

| foetal development | 78,365 | 1,872 | 2.34 | 42,646 | 54.42 |

| Total | 921,483 | 19,113 | 2.07 | 626,619 | 68.00 |

In terms of questions proposed by different care-givers, the anxiety level of mothers' questions were higher than fathers but much lower than grandparents and other care-givers. Results suggested that contemporary Chinese mothers of young children have positive attitudes regarding their parenting and are confident in their practices. However, since grandparents take more responsibilities in nurturing young children than fathers in Chinese families, grandparents felt more anxious than children's fathers (see Table 8).

| Different care givers | N | High anxiety | Low anxiety | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Mother | 8,409 | 1,363 | 16.21 | 7,046 | 83.79 |

| Father | 405 | 19 | 4.69 | 386 | 95.31 |

| Grandparents | 2,315 | 1,012 | 43.72 | 1,303 | 56.28 |

| Total | 11,129 | 2,484 | 22.02 | 8,795 | 77.98 |

Table 9 reports the level of anxiety reflected from questions of different age groups of children. Generally the number of questions in the high level anxiety category was much less than questions in the low level anxiety category. In addition, among the questions in the high level anxiety category, the highest level of anxiety was 0-12 months, followed by 13-24 months and 25-36 months, and then 37 months and above. Results indicated that parents felt more anxious when infants were very young. For example, parents' questions could be "I am very anxious about my newborn baby's sleeping problems. She seems never want to sleep. What should I do???". It also could be suggested that parents of infants were not capable of taking care of their young children. Their parental efficacy could be low and their eagerness of solving problems was very obvious. They were expecting to achieve suggestions from others through Internet social technology.

| Age groups (month) | N | High anxiety | Low anxiety | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| 0-12 mon. | 123,290 | 38,705 | 31.39 | 84,585 | 68.61 |

| 13-24 mon. | 9,896 | 3,189 | 32.23 | 6,707 | 67.77 |

| 25-36 mon. | 8,191 | 2,617 | 31.95 | 5,574 | 68.05 |

| >=37mon. | 10,284 | 2,866 | 27.87 | 7,418 | 72.13 |

| Total | 151,661 | 47,377 | 31.21 | 104,284 | 68.79 |

Discussion

The purpose of this study is to explore contemporary Mainland Chinese parents' needs and questions of parenting young children as well as their anxiety level through text-mining approach according to parents' messages posted on the most popular Internet discussion board in China. Results indicated that the most frequent words that parents posted were eating, sleep, formula, diarrhea and cough; and the most popular themes of parents' questions are parenting knowledge and skills.

Previous studies have reported that parents of young children considered parenthood as a stressful and demanding life role (Adler, et al., 2015). Their needs include children's physical, emotional and cognitive development (Gibson and Hanson, 2013). Parent-child communication and discipline strategies were also high-rated supports that parents eager to achieve from traditional parenting programmes. As a results, researchers were used to study parental needs from a developmental-oriented perspectives. However, the current study analyse the questions based on parenting-oriented perspectives. Therefore, the topics found in this study are all related to parents' practices, such as parenting knowledge and skills. In addition, most previous study focused on parents of children with special needs. So disease treatment, emotional intervention and social integration were principle concerns of these parents. Although the current study also found that parents were concerned about their children's health issues, they only asked questions about common diseases and nurturing skills. Questions about professional treatment would not be focused by parents' in this study.

These words and themes illustrated that issues regarding young children's common disease and daily routine were focused by most Mainland Chinese parents. This is reasonable because the current study focused on parents with children aged up to six years old. New parents and parents with very young children should be more likely to be cautious about their parenting knowledge and skills. Particularly, contemporary Mainland Chinese parents are eager to acquire accurate and scientific parenting knowledge and effective parenting skills to ensure the quality of their parenting and to relieve parenting stress as well.

In addition, despite contemporary Mainland Chinese parents' educational level and family income are relatively higher than before, our findings revealed that parents of young children still lack scientific knowledge and self-confidence in their parenting behaviour. It also could be argued that the more the parents understand the importance of early care and development to their children's future development, the more they concern about their quality of early parenting practices.

As expected, our findings suggested that parenting needs were inconsistent between children's father and mother. Mainland Chinese mothers are more concerning about parenting knowledge than fathers while fathers' questions of parenting skills are similar with mothers'. These results highlighted that Mainland Chinese mothers not only want to acquire parenting skills but also want to understand the relevant knowledge corresponding to the skills while fathers are only concerning about the specific skills of parenting. Previous studies have indicated that fathers would be more interested in achieving skills of engaging their children and supports of co-parenting (Ammari and Schoenebeck, 2015). It could be indicated that Mainland Chinese fathers of young children were more likely to seek answers about specific strategies of nurturing young children instead of cooperation issues with children's mothers.

Unlike previous studies, the current study found that in Mainland China, the number of questions regarding to grandparenting are considerable, even more than fathering issues. Although we cannot confirm that those questions regarding grandparenting were actually asked by grandparents, the contents of questions were related to grandparenting certainly. Previous studies from western countries found that grandparenting was a supplement for at-risk families (Jang and Dworkin, 2014). This could be different from the reason why Chinese grandparents participated in nurturing young children. Therefore, grandparents from different cultures might have different concerns of parenting. Researchers from western cultures found that grandparents paid more attentions to families' economic status, peer effects and their own parental efficacy. However, in the current study, questions regarding grandparenting were about how to improve their parenting skills and parent-child relationships. It could be imply that grandparents take great responsibilities of parenting young children in contemporary Mainland Chinese families and they are making great efforts to ensure the quality of parenting and to relieve parenting stress of their own children.

Moreover, parents' needs results in Internet use patterns that may correspond with their children's development needs appropriately (Doty and Dworkin, 2014; Rudi, et al., 2015). Previous studies have suggested parents of children from different age groups have different information and communication needs. Consistent with the literature, the current study found that the number of questions of 0-1-years old was the greatest and before age 3, their parents' needs of parenting knowledge and skills decrease gradually as children's age increase (Kostagiolas, et al., 2013). However, after age 3, parents began to ask more questions, which was mainly reflected in parental knowledge and skills. Comparatively few of previous research explored diversity of parents' needs with children from different age groups, however, discrepancy was discovered in ethnicity and family income (Kumar and Schoenebeck, 2015). Results of the current study indicated that themes of parents' concerns or needs had been changing as their children's development needs were changing.

Inconsistent with previous studies examining parents' emotional needs of children with special needs, the current study found that the anxiety level of Mainland Chinese parents were relatively low than expected (Zhao and Basnyat, 2018). The reason could be that most parents in the current study did not have sick children so they mainly concerned about general parenting needs and questions. They did not involve in emergency situations, so their anxiety level is not high.

In fact, researches analysing parents' emotions from their needs and questions were relatively few. However, sentiment analysis could disclose parents' intentions, emotions and anxiety level according to their online statements. For example, researchers regarding parents with special needs found that parents did have negative emotions while discussing diseases and treatment of their children (Harvey, et al., 2017). From expression of emotions in parents' questions, our results suggested that Mainland Chinese parents of young children generally do not express very anxious emotions. The most anxious questions are raised by mothers regarding parenting knowledge and skills. Mother feels more anxious than fathers and parents feel more anxious when children are up to one-year old. Few of studies collected and analysed parental emotional expressions when conducting needs assessment of parenting. Findings of the study provide an overall picture of contemporary Mainland Chinese parents' emotional status and their well-beings as well. From the perspective of eastern culture, Mainland Chinese parents were considered as Tigers' mothers referring to their strict and disciplinary parenting strategies. Chinese Tigers' mothers are always anxious about their children's learning and development. However, the anxiety level of parents in this study does not support this argument.

Practical implications

Previous research have indicated that parents consistently used Internet to seek parenting information of education and health issues (Baker, et al., 2016). Some studies have shown that the use of Internet can result in positive parental attitude and behaviour changes (Haslam, et al., 2017). The current study collected more than 900,000 parental questions in 36 months from the Internet and found willingness by parents to use Internet as a reliable source for various parenting needs and questions. Therefore, Internet parenting education programme could provide parents an alternative or supplement of traditional face-to-face parenting education programmes. On-site parenting education programmes could be restricted by a few of challenges in recruiting, engaging and retaining parents, who would have numerous barriers to attendance (Koerting, et al., 2013; Spoth et al., 2000). Internet provides feasible opportunities for delivering evidence-based parenting education programmes to a board of range of parents, including high-risk families who usually are reluctant to receive any kind of parenting services.

In addition, parents' deficiency of parental knowledge and skills revealed that parent's education programme or other social supports of families with young children should be both knowledge-oriented and practice-oriented. According to our findings about grandparents' questions, parenting education programmes should consider senior adults as their target population in Mainland China. In the traditional Chinese culture of the family, grandparents are reliable resources of early parenting of families so they should also be supported by parenting education programmes. Moreover, grandparents also need to deal with the relationships between their own children, especially when their parenting opinions are conflict with opinions of their grandchildren's parents.

Moreover, parents' information seeking behaviour could also be a way of achieving social support from other parents online. Therefore, both offline and online parent education programmes should consider the emotional needs of parents initiatively and design specific functions of providing social support for them to deal with parents' stress and problems.

Limitations

The current study has the following limitations. Our study only collected questions that parents raised on the discussion boards or forums of parenting Websites. Future study could explore parental questions or discussions on other social media including applications on mobile devices, such as Weibo, WeChat or QQ, which are three major mobile APPs for social communication in Mainland China. Moreover, although the Web text-mining method adopted in this study is the cutting edge natural language processing technology, this study only analyse the parent questions and dialogues that are posted on the forum owing to the limitations of data sources. Future research can further expand the dimensions of data and obtain more in-depth research results from the correlation analysis with other data. However, based on the data mining analysis method, it is still impossible to understand the source of the parents' problems and related background information. Future research can be conducted by sampling and interviewing parents of different groups to further explore the reasons for parents' needs, and to analyse parental needs from various aspects such as cultural values.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the study identified a few of parenting issues that contemporary Mainland Chinese parents are most concerned about, such as parenting knowledge, parenting skills and pregnancy issues. The study also found that different care-givers have different parenting needs and parents' needs are changing as their children are growing up. Although parents have considerable needs in parenting knowledge and skills, their emotional status is relatively positive. It also reveals the significance of developing effective online parenting education programme that can provide parents and grandparents more convenient and pesonalised services. Internet will never replace the role of the professionals in education and early care but must be seen today as an integral part of modern multi-disciplinary approach.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by funding from Shanghai Education Scientific Research Program (Grant No. C17053)

About the authors

Huihua He is an associated professor of College of Education in Shanghai Normal University. She Obtained her Ph.D in Washington State University in 2007. Her research interests includes Information and Communication Technology uses in early education, early family care and education, early social-emotional learning, and related topics. She can be contacted at: hehuihua@shnu.edu.cn

Si He is a graduate student of College of Education in Shanghai Normal University. She graduated from the School of Education at Shanghai Normal University. Her research interests include the combination of information processing and early education. She can be contacted at: daisyhs.ikonic131@gmail.com

Yan Li is a professor of College of Education in Shanghai Normal University. She obtained her PhD degree from East China Normal University. Her research focuses on children's emotional development and learning, family and school collaboration, and preschool teacher education. She can be contacted at: liyanshnu@outlook.com

References

Note: A link from the title is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Ammari, T. & Schoenebeck, S.Y. (2015). Understanding and supporting fathers and fatherhood on social media sites. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1905-1914). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702205

- Adler, K., Salanterä, S., LeinoKilpi, H. & Grädel, B. (2015). An integrated literature review of the knowledge needs of parents with children with special health care needs and of instruments to assess these needs. Infants & Young Children, 28(1), 46-71. https://doi.org/10.1097/IYC.0000000000000028

- Bailey, D. B., & Simeonsson, R. J. (1988). Assessing needs of families with handicapped infants. The Journal of Special Education, 22(1), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/002246698802200113

- Baker, S., Sanders, M. R. & Morawska, A. (2016). Who uses online parenting support? A cross-sectional survey exploring Australian parents' Internet use for parenting. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 26, 916-927. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0608-1

- Bartholomew, M. K., Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Glassman, M., Kamp Dush, C. M. & Sullivan, J. M. (2012). New parents' Facebook use at the transition to parenthood. Family Relations, 61(3), 455-469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00708.x

- Brady, D. L. (2010). Needs assessment of parents of typical children ages 4 to 5 years old. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Southern California.

- China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC). (2018). The 42nd statistical report on Internet development in China. http://www.cnnic.net.cn/hlwfzyj/hlwxzbg/hlwtjbg/201808/P020180820630889299840.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/p-020180820630889299840)

- Chung, M. J. (1993). Parent education for kindergarten mothers: Needs assessment and predictor variables. Early Child Development and Care, 85(1), 77-88. https://doi.org/10.1080/0300443930850109

- Doty, J. & Dworkin, J. (2014). Parents' of adolescents' use of social networking sites. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 349-355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.012

- Dworkin, J., Connell, J. & Doty, J. (2013). A literature review of parents' online behavior. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 7(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2013-2-2. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2K2JFeR)

- Ellis, J. T., Luiselli, J. K., Amirault, D., Byrne, S., Omalley-Cannon, B., Taras, M. & Sisson, R. W. (2002). Families of children with developmental disabilities: assessment and comparison of self-reported needs in relation to situational variables. Journal of Development and Physical Disabilities, 14(2), 191. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015223615529

- Esarey, A. & Qiang, X. (2011). Digital communication and political change in China. International Journal of Communication, 5(5), 298-319. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/688/525 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3kkjoVu)

- Gang, Q. & Bandurski, D. (2011). China's emerging public sphere: the impact of media commercialization, professionalism, and the Internet in an era of transition. In S. Shirk (Ed.), Changing media, changing China (pp. 38-76). Oxford University Press.

- Gibson, L. & Hanson, V. L. (2013). Digital motherhood: how does technology help new mothers? In R. Grinter, T. Rodden, P. Aoki, E. Cutrell, R. Jeffries & G. Olson, (Eds.), Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems, Paris, France, 27 April - 2 May, 2013 (pp. 313-322). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2470654.2470700

- Gowen, J. W., Christy, D. S. & Sparling, J. (1993). Informational needs of young children with special needs. Journal of Early Intervention, 17(2), 194–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/105381519301700209

- Graves, C. & Hayes, V. E. (1996). Do nurses and parents of children with chronic conditions agree on parental needs? Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 11(5), 288–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0882-5963(05)80062-4

- Hall, W. & Irvine, V. (2009). E-communication among mothers of infants and toddlers in a community-based cohort: a content analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(1), 175-183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04856.x

- Harvey, S., Memon, A., Khan, R. & Yasin, F. (2017). Parent's use of the Internet in the search for health care information and subsequent impact on the doctor-patient relationship. Irish Journal of Medical Science, 186(4), 821-826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-017-1555-6 /li>

- Haslam, D. M., Tee, A. & Baker, S. (2017). The use of social media as a mechanism of social support in parents. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 26(3), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0716-6

- Jacobson, A. L., & Engelbrecht, J. (2000). Parenting education needs and preferences of parents of young children. Early Childhood Education Journal, 28(2), 139-147.

- Jang, J. & Dworkin, J. (2014). Does social network site use matter for mothers? Implications for bonding and bridging capital. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 489-495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.02.049

- Jang, J., Dworkin, J. & Hessel, H. (2015). Mothers' use of information and communication technologies for information seeking. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18(4), 221-227. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0533

- Jang, J., Hessel, H. & Dworkin, J. (2017). Parent ICT use, social capital, and parenting efficacy. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 395-401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.025

- Ji, Q., Currinmcculloch, J. A., Zhang, A., Streeter, C. L., Jones, B. L. & Chen, Y. (2018). Assessing the needs of parents of children diagnosed with cancer in china: a psychometric study developing a needs assessment tool. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 35(1), 6-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454217723862

- Kennedy, T. L., Smith, A., Wells, A. T. & Wellman, B. (2008). Networked families. Pew Research Center.

- Kerr, L. M., Harrison, M. B., Medves, J., Tranmer, J. E. & Fitch, M. I. (2007). Understanding the supportive care needs of parents of children with cancer: an approach to local needs assessment. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 24(5), 279-293. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454207304907

- Koerting, J., Smith, E., Knowles, M. M., Latter, S., Elsey, H., McCann, D. C. & Sonuga-Barke, E. J. (2013). Barriers to, and facilitators of, parenting programs for childhood behavior problems: a qualitative synthesis of studies of parents' and professionals' perceptions. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 22(11), 653–670. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0401-2

- Kostagiolas, P., Martzoukou, K., Georgantzi, G. & Niakas, D. (2013). Information seeking behavior of parents of pediatric patients for clinical decision making: the central role of information literacy in a participatory setting. Information Research, 18(3), paper 590. http://informationr.net/ir/18-3/paper590.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3eRHndB)

- Kumar, P. & Schoenebeck, S. (2015). The modern day baby book: enacting good mothering and stewarding privacy on Facebook. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM conference on computer supported cooperative work and social computing, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 14-18 March, 2015 (pp.1302-1312). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2675133.2675149

- Lee, S. J., Hoffman, G. & Harris, D. (2016). Community-based participatory research (CBPR) needs assessment of parenting support programs for fathers. Children & Youth Services Review, 66, 76-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.05.004

- Liu, J., Zhou, M., Lin, L., Kim, H.J. & Wang, J. (2017). Rank Web documents based on multi-domain ontology. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing, 8(4), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-017-0566-5

- McDaniel, B. T., Coyne, S. M. & Holmes, E. K. (2012). New mothers and media use: associations between blogging, social networking, and maternal well-being. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(7). 1509-1517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-011-0918-2

- MacQueen, J. (1967). Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In L. M. LeCam & J. Neyman, (Eds.), Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability (pp. 281–297). University of California Press.

- Mikolov, T., Sutskever, I., Chen, K., Corrado, G. & Dean, J. (2013). Distributed representations of words and phrases and their compositionality. In : C. J. C. Burges, L. Bottou, M. Welling, Z. Ghahramani, & K. Q. Weinberger, (Eds.). Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, (vol 2, pp. 3111-3119). Curran Associates.

- Morris, M. R. (2014). Social networking site use by mothers of young children. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM conference on computer supported cooperative work, Baltimore, Maryland, USA, 15-19 February, 2014 (pp. 1272-1282). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2531602.2531603

- Rudi, J., Dworkin, J., Walker, S. & Doty, J. (2015). Parents' use of information and communications technologies for family communication: differences by age of children. Information, Communication & Society, 18(1), 78-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.934390

- Rawlins, P. S., Rawlins, T. D. & Horner, M. (1990). Development of the family needs assessment tool. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 12(2), 201-214. https://doi.org/10.1177/019394599001200206

- Salton, G. (1974). A vector space model for automatic indexing. Communications of the ACM, 18(11), 613-620. https://doi.org/10.1145/361219.361220

- Salton, G. & Buckley, C. (1988). Term-weighting approaches in automatic text retrieval. Information processing & management, 24(5), 513-523. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4573(88)90021-0

- Sillence, E. & Briggs, P. (2007). Please advise: using the Internet for health and financial advice. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(1), 727-748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2004.11.006

- Spoth, R., Redmond, C. & Shin, C. (2000). Modeling factors influencing enrollment in family-focused preventive intervention research. Prevention Science, 1(4), 213-225. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026551229118

- Stern, M. J., Cotten, S. R. & Drentea, P. (2012). The separate spheres of online health: gender, parenting, and online health information searching in the information age. Journal of Family Issues, 33(10), 1324–1350. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X11425459

- Suzuki, S., Holloway, S. D., Yamamoto, Y. & Mindnich, J. D. (2009). Parenting self-efficacy and social support in Japan and the United States. Journal of Family Issues, 30(11), 1505-1526. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X09336830

- Walsh, A. M., Hamilton, K., White, K. M. & Hyde, M. K. (2015). Use of online health information to manage children's health care: a prospective study investigating parental decisions. BMC Health Services Research, 15(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0793-4

- Zaidman-Zait, A. & Jamieson, J. R. (2007). Providing web-based support for families of infants and young children with established disabilities. Infants & Young Children, 20(1), 11–25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001163-200701000-00003

- Zeng, S. & Cheatham, G. A. (2017). Chinese-American parents' perspectives about using the Internet to access information for children with special needs. British Journal of Special Education, 44(3), 273-291. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12182

- Zhao, X. & Basnyat, I. (2018). Online social support for "Danqin mama": a case study of parenting discussion forum for unwed single mothers in China. Computers in Human Behavior, 80, 12-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.10.045