Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science, Copenhagen, Denmark, 19-22 August, 2013

Using design experiments to investigate conceptual issues in knowledge organization: an ongoing study

Melanie Feinberg, Julia Bullard and Daniel Carter

The University of Texas at Austin, School of Information, 1616 Guadalupe St., Suite 5.202, Austin, TX 78701-1213, USA

Introduction

In January, 2013, the New York Times ran a story, “Generation LGBTQIA,” about the conceptual battles that some university students in the U.S. have begun to wage regarding categories that define gender and sexual preference. Whereas an earlier generation of student activists had focused their efforts toward the relatively strict definition of new categories—to emphasize both the validity and distinctiveness of lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and transgendered persons as groups—these current students wanted to introduce categories with fuzzy, unclear boundaries and scope. The “A” in the LGBTQIA formulation, for example, could be either “asexual” (for a celibate person) or “ally” (for a heterosexual person of conventional gender who nonetheless actively supports the recognition of alternate gender and sexual identities). Moreover, the students profiled in the article spoke of shifting through the different categories, with some invoking a desire to recategorize themselves at will or to appropriate one or more categories in personally specific ways. And yet these students also resisted the exclusive use of broader terms to encompass all variations of gender and sexual difference (such as “queer”), wanting to define themselves both loosely and specifically at the same time. For example, the article describes how Britt, a student at the University of Pennsylvania, claims the term “bi-gender” (predominantly female at some times, predominantly male at other times) to describe herself, finding this category to be “more fluid than ‘transgender’ but less vague than ‘genderqueer.’”

In wanting to be named and yet not wanting to be pinned down with a limited or inadequate definition, the experiences of these students form a particularly vivid example of residuality, a phenomenon of classification articulated by Susan Leigh Star and Geoffrey Bowker (Star and Bowker, 2007). Star and Bowker describe the residual as what doesn’t quite fit into a category system. The residual might be completely absent, or it might be inadequately expressed, or split between existing categories. In some sense, the residual represents the persistent vagueness, ambiguity, and invisibility that classifications attempt to eliminate by carving up the world into clearly demarcated groups with precisely delineated relationships. For Star and Bowker, the residual is an inevitable byproduct of the classificatory enterprise, even as it also poses a challenge to actively confront. In the context of existing classification design practice, the idea of the miscellaneous, other, or unexpressed is similarly characterized as an inevitability (Michael Buckland (2012) provides an extensive catalogue of reasons why this occurs). Traditionally, the associated design goal would be to minimize the residual as much as possible.

In this project, we explore what happens when we attempt to foreground the residual instead of minimizing it. Through a set of design experiments, we question the status of residuality as a problem by actively engaging it through an information collection’s descriptive infrastructure. Our experimental digital information collections attempt to exploit their gaps and borders as features to be welcomed, instead of hiding them like uncomfortable secrets. In doing so, we hope to learn about the information collection as a type of document genre, in terms of what it can express, how it can produce that expression, and how this expression can be read. Moreover, we hope to learn more about the notion of residuality itself and how to view it as a resource, as well as a constraint.

To focus this investigation, we target three primary research questions:

- How can a digital information collection foreground the experience of the residual?

- What constitutes the authoring experience of such an information collection?

- What constitutes the reading experience of such an information collection?

The paper is organized as follows. First, we describe our conceptual framework in more detail, focusing on the feminist theorist Gloria Anzaldua’s notion of mestiza consciousness as a design goal, which we link to Star and Bowker’s residuality. Next, we present our approach to investigating this space, which draws on work in critical making and critical design, as primarily introduced in human-computer interaction (HCI), synthesized with complementary work on interaction criticism. We then describe the design experiments that we created and discuss initial findings. Our experiments took the form of three “transformations” of a small (50 total resources) digital video collection that had been originally created according to traditional descriptive principles. Each of the three authors of this paper “transformed” a separate copy of the original collection, changing its descriptive infrastructure (index categories and values, titles and abstracts, and other metadata) to experiment with enacting mestiza consciousness. These three transformations, each representing a different mode of engagement with residuality, have then become the focus of structured reflection by the transformation authors, by invited subject-matter experts, and by students in a semester-length course on collection design.

At its current stage, the primary contribution of this paper is in its vision and novel approach, not in its findings, which are preliminary. In articulating Anzaldua’s mestiza consciousness as an alternate conceptual foundation for the design of information collections, we reconsider the conventional wisdom regarding the goals, function, and associated structure of classification schemes and other elements of descriptive infrastructure, such as titles, abstracts, and subcollections. As our mode of inquiry for this provocation, we adapt strategies from design research in HCI to imagine, construct, and critique alternate uses of descriptive infrastructure that attempt to enact mestiza consciousness. Our findings emerge from both the process of design itself and from various forms of structured reflection on the experimental products. We suggest that such theoretically motivated design interventions form a productive complement to the existing repertoire of research methods for information studies in general, and for knowledge organization in particular.

Residuality and mestiza consciousness

The state of residuality as described by Star and Bowker has connections to the feminist writer Gloria Anzaldua’s idea of mestiza consciousness, a life experience that continually fuses divergent aspects of identity through the crossing and recrossing of border states. In her classic work of feminist theory, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, Anzaldua uses her personal history as someone with disparate, conflicting aspects of being to describe a mode of existence that is enacted both outside and between traditional categories of culture, class, and ethnicity. Anzaldua describes, for example, her status as a Chicana (American of Mexican descent) from the Rio Grande valley in Texas (on the border with Mexico), raised in an agricultural, socially traditional community, who is also a poet, scholar, feminist, and lesbian. The complex and contradictory knot of categories that Anzaldua herself embodies incorporates within itself ambiguity, conflict, and a level of indeterminacy, a condition that Anzaldua terms mestiza consciousness. The word mestizo [from Spanish for “mixed”] indicates, in its traditional usage, intermarriage between Spanish conquerors in Latin America and the indigenous peoples; most Mexicans today have this heritage. (Mestiza is the feminine form.) Anzaldua both appropriates the traditional usage and transforms it, using the term mestiza to indicate not just a mixed ethnic heritage but a mixed sense of culture, class, language, and other elements of core identity. In the construct of mestiza consciousness, Anzaldua reorients the residual, making it central.

Mestiza consciousness additionally conceptualizes the residual as a continuously dynamic process of transformation. A key element of Anzaldua’s thought is the experience of transition, described evocatively in terms of the Aztec goddess Coatlicue, who includes both creator and destroyer aspects. Anzaldua’s depiction of the Coatlicue state involves moving beyond mere acceptance or rejection of an opposition (much as the student activists described in the introduction want to move beyond binary divisions such as “straight” and “queer” or even “lesbian” and “gay”). According to Anzaldua, Coatlicue “simultaneously, depending on the person... represents: duality in life, a synthesis of duality, and a third perspective: something more than a mere duality or a synthesis of duality” (2012, p. 68). The new mestiza who lives the Coatlicue state “operates in a pluralistic mode…not only does she sustain contradictions, she turns the ambivalence into something else” (2012, p.101). The new mestiza shows within herself a path between oppositions, a path that has a specific history of travel inscribed within it but has no endpoint. From the perspective of classification schemes, we can think of this as a continual process of understanding what a category like “straight” or “queer” can mean: what it means to be that, to not be that, to sort of be that, or to once have been that, all as a specific, ephemeral experience. Anzaldua attends not only to the cognitive aspects of this Coatlicue state but also to its emotional components. The period leading to a transition is one of pain and suffering, while the state following its acceptance is one of calm liberation. (Star and Bowker similarly note that residuality is painful when forced but can be empowering if chosen.)

In addition to a conceptual framework, mestiza consciousness can also be seen as a form of rhetorical strategy. In Borderlands, Anzaldua shatters document forms in a way that makes the reader’s path echo the mestiza’s path: she includes historical background and scholarly exegesis mixed with poetry and personal anecdotes, even dreams and visions. Anzaldua incorporates extensive sections about the writing process itself, which include vivid images of physical states such as intense nausea and being in a sort of trance (Star, also, includes detailed descriptions of such experiences in the article with Bowker, where she notes, for example, carrying pieces of writing in her pockets, for weeks, so that they will remain near her at all times). Anzaldua further uses multiple languages, including English, standard Spanish, and a variety of Spanish dialects, such as Chicana Spanish and a Tex-Mex hybrid of Spanish and English. In proceeding through the book, the reader must work through material that is, frankly, irritating in its density and superficial lack of coherence as indicated by existing genre conventions. It is only through accepting a level of unknowing and releasing expectations based on past traditions that the reader can progress in understanding and perceive the underlying structure of Anzaldua’s thought.

The experience of reading Borderlands suggests that an attempt to enact mestiza consciousness/residuality in an information collection will also need to incorporate experimental forms, potentially in a disquieting or initially annoying way, as traditional goals, such as efficient information retrieval, are subverted through the alteration of features that typically support those goals. For example, in a traditional well-constructed controlled vocabulary, the relationships between a broader category and its narrower terms should be apparent, consistent, and coherent, with the terms in each array mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive. Moreover, the conceptual distance between the broader and narrower terms should be proximate (that is, not jumping directly from the broad class of Animals to a specific group like Cats, but including intermediate categories such as Vertebrates, Mammals, and so forth along the way), and the terms at a single level should be at a similar level of abstraction (all at the level of Cats and Dogs and not mixed between Cats and Carnivores). In a vocabulary motivated by mestiza consciousness, such principles might be (purposefully) violated, either consistently or inconsistently. We seek to understand and characterize the experience produced through such violations, for authors of information collections as well as for readers (or users).

Critical making as a mode of research inquiry

An emerging trend in design research considers the making of new artifacts as itself a form of research (in contrast to design as being informed by research, or design as a means of testing hypotheses through performance tests and other evaluative measures). Many of these activities find initial inspiration in the work of Donald Schon, who characterized the practice of working designers as potentially achieving a form of experiment. Through both conscious and subconscious activities of reflection (reflection on action and reflection in action), the designer, in Schon’s depiction, uses the process of an evolving conversation with the design situation to generate new knowledge about both the process of design and its outcomes (Schon 1983). In HCI, scholars have expanded this general concept of design as research in a number of ways.

Critical making, as introduced by Ratto (2011), identifies the process of designing, building, and using an artifact as a means to explore theoretical questions. Ratto describes an example of workshop participants building individual elements of a networked system to explore different means by which networked agents can either contribute to, or take from, the system. This activity of making enabled participants to engage in a productive conversation about the role of “walled gardens,” or proprietary enclosed systems such as Facebook, in the ecology of the Internet at large. In critical making, the outcome is this reflection upon the process of building and deploying an artifact; the design product itself is only the means by which this insight is produced. Notably, the making activity in this approach is conducted by the research participants, although the infrastructure to support the making is created by the researcher.

Critical design, an approach initiated by Dunne (1999, 2006), involves the generation of an experimental artifact that transgresses cultural norms and provokes reevaluation of those norms. Dunne, for example, describes a series of conceptual design proposals to variously make apparent the invisible, intersecting electro-magnetic fields that are constantly emitted by our array of electronic household objects, such as televisions and computers. Dunne calls these proposals a form of “value-fiction,” whose goal is not to satisfy an existing user need but to explore the enactment of value states different from those currently operational for that class of objects, to “ask questions rather than provide answers” and to “stimulate discussion in a way that a film or a novel might.” (One proposal involves a means to physically represent, as both colors and sounds, the “dreams” of objects like televisions as echoes of their electro-magnetic emissions. This artistic representation is generated through a user’s touch.)

While Dunne’s presentation is sketchy and impressionistic, S. Bardzell, et al (2012) attempt to describe a more systematic approach to critical design as a research method. They summarize the design and deployment of two artifacts created to align with a feminist approach to HCI and to spur the questioning of gender roles. With their “significant screwdriver,” for example, one’s use of the artifact generates a visual representation of that work, which can then be printed out and given to a loved one in the form of a greeting card. This action is intended to recast the idea of “handyman” tasks, more typically undertaken by men, as a form of caring and nurturing. In critical design, there is more emphasis on the design itself than in Ratto’s critical making; however, the outcome centers around the quality of the experience generated by the artifact as a means of questioning current values. While the “significant screwdriver” might enable us to learn about attitudes and activities associated with household work, in addition to suggesting implications for feminist design principles and the process of critical design itself, it does not, as described by S. Bardzell, et al, directly lead to new ideas about screwdrivers (or other hand tools) as a class of objects. In critical design, the “participants” in the research (or the people who experience the artifact) are distinct from the researchers who conceive and make the artifact, although S. Bardzell, et al note that this separation is artificial and uneasy; their projects proceeded in unanticipated ways as their “participants” used the artifacts in unexpected configurations. S. Bardzell, et al suggest that distinctions between “researchers” and “participants” in critical design are unavoidably blurry.

Reflective design, proposed by Sengers, et al (2005), also aims to learn about the situation in which an experimental design is deployed, but it incorporates an additional focus on the artifact itself. Sengers, et al propose that all interface designs should encourage critical reflection on the part of both designers and users regarding the role of technology in everyday life; however, the designs that Sengers, et al produce as case studies of reflective design support additional goals as well, although they do not respond to previously identified user problems. One of Sengers’ et al’s case studies involves a means by which museum visitors can become more active participants in the experience of attending an exhibit. Because the research team discovered that museum visitors tend to be reticent about contributing explicit commentary regarding museum objects, believing that their lack of expertise means that they have little of value to say, Sengers, et al developed an application that logged a “digital imprint” when users of an exhibit guide selected an object to learn about. In this way, other visitors could see not only how many people elected to access information about each object, but which anonymous avatars did so across the range of available objects. In contrast to the critical design approach, the reflective design case studies described by Sengers, et al illuminate something about the broad class of artifacts (such as exhibition guides) in which their experiments resided, as well as about the experiences of designers and users, and their experiments involved the development of multiple design ideas in a particular artifact space. Similar to critical design, the “participants” interacted with the design experiments created by the “researchers,” although as with critical design, findings emerged from the reflective activities of both these groups.

Our approach: making and criticizing

Although we are interested in residuality itself as a concept, and in the experience of both writers and readers of information collections that attempt to foreground residuality, we are also interested in the information collection as a document genre, and in the mechanisms through which the reader’s productive experience of residuality can be generated. For example, we want to be able to describe how a classificatory array that mixes concepts at different levels of abstraction works within a particular design experiment to produce certain expressive effects. To this end, we supplement the making of design experiments with a more structured, formal reflection than those solicited by S. Bardzell, et al and Sengers, et al. Instead of asking “typical users” to interact with our experiments in a naturalistic way, we have solicited responses more in the vein of scholarly criticism. The use of criticism in the mode of the humanities, to produce compelling interpretations of interactive artifacts, such as information collections, has been introduced by a range of scholars in HCI, including Lowgren and Stolterman (2004) and Bardzell and Bardzell (2008). J. Bardzell (2011) has proposed a number of principles for rigorous, systematic interaction criticism, including four perspectives from which criticism often emerges: a focus on the creator, on the artifact itself, on the reader (or user), and on the social context in which the artifact is embedded. The first three of J. Bardzell’s perspectives align well with our research questions, and we have incorporated them into our research approach.

To include robust elements of both making and criticizing, we formulated the following research plan:- Develop a set of multiple design experiments that display different means of enacting mestiza consciousness in an information collection through interventions with its descriptive infrastructure (classification scheme and other metadata elements).

- Write structured reflections that address both the authoring activity and the created product.

- Solicit critical responses to the design experiments from a variety of subject experts, including both scholars and experienced practitioners from appropriate domains.

- Solicit critical responses to the design experiments from student critics who have been instructed in both the conceptual background of the project (including classification design traditions, residuality and mestiza consciousness, and critical making) and in the practice of interaction criticism.

- Synthesize, compare, and interrogate the various responses to the experiments.

The following paragraphs describe each element in more detail.

Design experiments

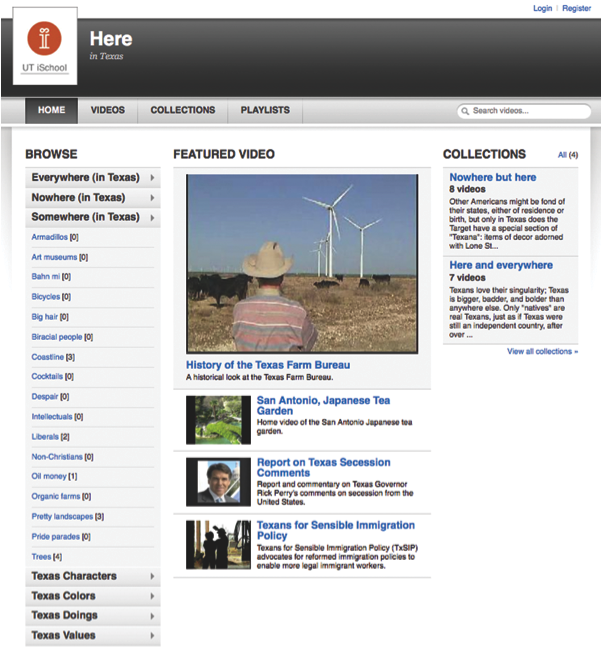

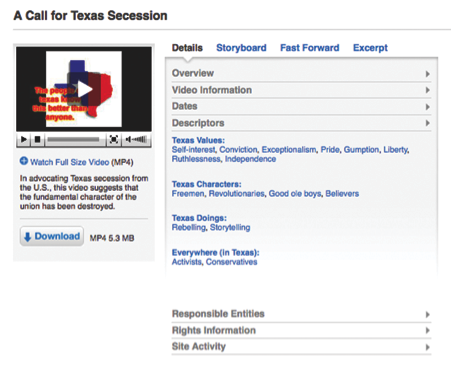

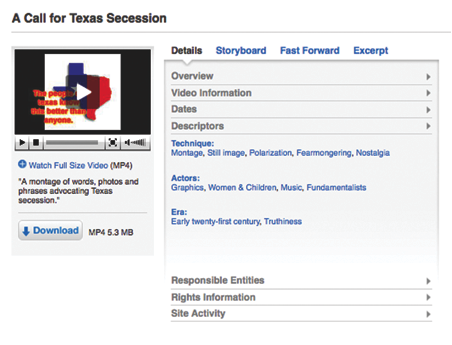

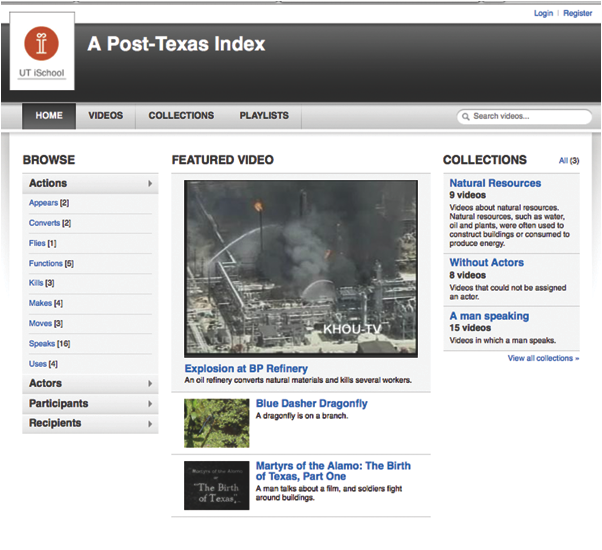

To ensure a level of productive comparability between design experiments, we created three “transformations” of a small, existing digital video collection. The initial collection contained 50 short videos, gathered from a variety of sources, all in the general domain of “Texas” as a subject area. (Of all U.S. states, Texas lays claim to a singular identity that stretches back to its brief period in the nineteenth century as an independent nation. This identity is perceived differently by Texas natives, by residents, and by residents of other states.) The original Texas collection was created in 2010 to be used in a variety of potential teaching and research situations, and its descriptive infrastructure was designed to follow traditional design principles and to be reasonably comprehensive (to provide a sense of each item’s contents without needing to watch each video). The Texas collection was created with the Open Video Digital Library Toolkit (OVDLT [1]), an easy-to-use environment for digital video libraries that includes a wide array of customizable metadata elements, such as:

- Any number of custom-defined descriptor sets (a descriptor set is a group of index terms [such as Politics, Sports, and Agriculture] identified with a broader category label [such as Subject, Genre, or Location]).

- Titles, alternate titles, sentence summaries of content, and longer abstracts of content.

- Any number of custom-defined roles associated with the video or its catalogue record (such as a sponsoring organization or director).

- Any number of custom-defined dates associated with the video or its catalogue record (such as the video’s original broadcast or the date that the catalogue record was created).

- Freeform tags.

- “Collections,” or selected subsets of annotated videos to express a particular theme.

The following images show some of these elements for the original Texas collection.

Our three “transformations,” or design experiments, took copies of the original Texas collection and manipulated them to the level possible with the OVDLT administration and cataloguing tools. Accordingly, all three “transformations” and the original collection include the same 50 videos, and overall page layout and interface features are standardized by the OVDLT. Only the descriptive infrastructure (descriptor sets, titles and abstracts, subcollections, and other metadata elements) was changed. Each of the three researchers took responsibility for one transformation and was free to create it as he or she saw fit, in keeping with the general design goal of foregrounding residuality and enacting mestiza consciousness. The three transformation experiments are named as follows:

- Here in Texas.

- Kaleidescopic Texas.

- Post-Texas Index.

Here in Texas attempts to engage how the 50 videos both do and do not represent the idea of “Texas,” as both stereotypes and in reality, as filtered through the author’s perspective as a non-native Texas resident. Accordingly, some of the descriptor sets reference concepts associated with this general idea of Texas that are not represented in the collection, as well as concepts that the current videos do participate in.

Kaleidescopic Texas presents a multifaceted idea of Texas that attempts to isolate areas of conflict, such as a tension between progress and nostalgia. Kaleidescopic Texas also relies on the authorial perspective of an outsider, in this case someone from a different country but living in Texas. Kaleidescopic Texas uses the subversion of traditional classificatory principles, such as mixing different levels of abstraction within a single descriptor set, to call attention to the artificiality with which such distinctions are maintained.

In contrast to the other two transformation experiments, Post-Texas Index eschews any recognizable authorial perspective, instead describing video elements as “objectively” as possible but from an extremely high level of abstraction. The intended effect is rather like the videos are being described by an alien from outer space, for an audience of other aliens: the context that endows the videos with meaning for human beings is stripped away. Both political rallies and the exhortations of football coaches to their players are described, for example, as “men speaking.”

Multiple forms of structured reflection on the design experiments

Our three research questions address the writing, or design process of the transformation experiments, the qualities of the design experiments themselves, and the reading experience. To address the question of the writing experience, each of the three researchers wrote summative reflective essays that distilled the researcher’s goals in creating a transformation as well as the process of attempting to enact those goals. These essays also encapsulated each designer’s sense of the most significant themes or issues to emerge from the making experience. (The next section of this paper will describe one of these.) These essays are supplemented with notes of informal design meetings that occurred regularly throughout the ten-week process of conceptualizing and implementing the design experiments.

To address the questions regarding the qualities in the design experiments that work to express mestiza consciousness, and to characterize the overall reading experience of this kind of collection, we are collecting two complementary forms of critical response. For the first set of responses, we arranged for eleven subject-matter experts to contribute a brief written essay (approximately 750 words) that engages the identified questions. Seven of these participants are academics who represent an array of related fields: classification research, infrastructure studies, digital libraries, human-computer interaction, and critical making. Four of the participants are practicing information professionals, including librarians, archivists, and digital content providers. Three of the practitioners have master’s degrees in LIS, and two of the practitioners have doctorates in literature; one practitioner additionally has a law degree. Participants were invited to address either a single design experiment in their responses or to compare two or all three of them, as they wished. Our expert participants were provided with brief background information about the goals of the project (including a concise introduction to residuality and mestiza consciousness). They were also given access to the original Texas collection.

For the second set of responses, 14 LIS master’s students in a semester-length course on digital collection design have a class assignment to write a 3,000-word essay addressing the two questions. As part of their course activities, the students read and discussed introductory material about traditional classificatory practices, as well as the Star and Bowker and Anzaldua pieces. The students also read several articles about critical making, critical design, and reflective design, as well as articles on interaction criticism. As with the expert respondents, students could address one, two, or all three design experiments in their essays, and they had access to the original Texas collection.

Preliminary findings and discussion

Although our analysis is currently ongoing, we present here a brief sense of how a particular theme emerged initially via the critical design process of making the transformations, and then how that theme was refined through sustained reflection occasioned by the solicited responses and student essays. The discussion here represents an interim stage in the development of our findings, as we continue to structure and synthesize the complex data that this project has generated. We include this preliminary material as an example of the type of knowledge we hope to gain from such design experiments, and to show how the interaction between critical making process, critical design product, and critical response to the design product enables us to develop, assess, and refine our understanding.

The making process provoked a number of questions regarding the nature and role of authenticity in the context of residuality and its portrayal in an information collection, as well as the nature and role of coherence, and the relationship between these notions. The accounts of residuality by Star and Bowker and of mestiza consciousness by Anzaldua rely heavily on the revelation of personal history as both the substance through which a broader illumination is generated and as the rhetorical means of its communication. Individual experience, as expressed through a well-developed authorial persona, provides a means through which the fracture that characterizes residuality/mestiza consciousness is mediated and understood. Even as some elements of the authorial persona are used to convey that which lies outside conventional modes of categorization, other elements of the persona provide a consistent grounding against which ambiguity, fluidity, and contradiction can be made meaningful.

In creating our transformations, all three authors found that we, as well, needed to identify a clear locus of coherence in order to motivate our explorations of fracture and provide a sense of control over our designs. Moreover, the sense of grounding and control that we found necessary to proceed as authors required that we trust the source of that coherence, or commit to it. For example, two authors initially wanted to experiment with creating purely fictive authorial personas, even multiple fictive personas at once, as a means to engage the pluralistic elements of the residual. But neither author could ultimately do so; adopting diverse fictional characters felt too forced and artificial, making the persona a distraction instead of a ballast. We did not have the creative resources to enable our commitment to fictional characters; we did not trust our abilities to create believable and yet utterly false personas. As the result of these initial authoring failures, all the transformation authors came to believe that some form of authenticity, which we associated with commitment, was a necessary component of a core coherence, and without this core coherence, we did not feel able to further develop a sense of fracture in a principled way. Although we abandoned the idea of creating fictional personas, however, we each found multiple, different routes toward achieving that necessary sense of authenticity.

The Here in Texas author did use an authorial persona in a manner similar to Star, Bowker, and Anzaldua, referring to particular life situations and events in collection annotations and creating an identifier (“Texas resident”) to mark authorship of each collection record. The overall goals for Here in Texas were thus deeply entwined with the intersecting specificities of a particular persona, and its sense of coherence came from the distinctiveness of that voice. The Post-Texas Index author, on the other hand, relied on a consistent concept to maintain a sense of coherence: the transformation was grounded in its use of a consistently high level of abstraction in description, emanating from a goal to retain conventional syntax while avoiding conventional semantics. The generic persona of the Post-Texas Index was subservient to the transformation’s conceptual goals, and its coherence came from the unity of its concept. The Kaleidescopic Texas author took a hybrid approach. The transformation’s concept involved the juxtaposition of three perspectives: that of the original, untransformed collection; an “objective” perspective associated with the ideals of traditional professional practice; and a “subjective” perspective. The subjective perspective did use an authorial persona, also grounded in that author’s personal experience. But the persona was only evident in some of the transformation’s features. The coherence for Kaleidescopic Texas came from the distinctiveness of the three separate elements of the concept; the voice of a persona distinguished one of these elements.

From within each transformation author’s “authentic” core of coherence, a particular focus for the residual could be explored. For the Here in Texas author, this was the concurrent reality and insufficiency of Texas stereotypes; for the Post-Texas Index author, this was the arbitrariness and yet necessity of context for understanding; and for the Kaleidescopic Texas author, this was the juxtaposition of multiple ways of interpreting individual descriptive facets.

Remarks from the two forms of critical responses that we collected challenged us to extend these initial thoughts on authenticity and coherence. The responses, particularly the solicited ones from experts, were exceedingly diverse in content and opinion, and we did not use them for any pervasive or consistently expressed remarks, but rather for revealing insights that may have appeared in only a few examples. In other words, we did not find it useful or appropriate to “code” the responses as one would do according to a social-science approach. (As an aside, we note that although it was not our goal for our respondents to accurately glean our authorial intentions in their interpretations, some respondents in both the solicited and student groups did indeed do so. While it would have been disappointing if all of the responses had mirrored our own ideas, it was nonetheless a certain validation that some respondents did interpret our transformations as designed.) In the solicited responses, one class of remarks that caught our attention was the characterization, by several participants, of the original Texas collection as “boring.” While the original collection followed a fairly standard approach in describing its videos, “boring” was nonetheless a surprising assessment. One wouldn’t call a physical library operating in a traditional mode “boring,” for example; it just wouldn’t seem applicable. It may be that in using “boring,” what these respondents really meant was “unexceptional,” but the use of “boring” recalled our attention to the structure that we were transforming, which we had not been actively considering in our making process. At the same time, several participants also referred to the Post-Texas Index as “boring.” Some of these were the same participants who used this term for the original Texas collection. Here, “boring” could not mean “unexceptional”; if anything, the Post-Texas Index was the most immediately strange of the three transformations, because the abnormal level of abstraction was readily apparent. In the student essays, “boring” was not used for either collection. The original Texas collection was described by terms like “familiar” and “accessible,” which are perhaps a more positive spin on “unexceptional.” But in these essays, as well, some students found the Post-Texas Index to be initially strange but ultimately not strange enough, more like a cartoon, or exaggerated, reality than an alternate reality. In contrast, Here in Texas and Kaleidescopic Texas were neither boring nor cartoons (which is not to say that they weren’t criticized; they were, but not on that basis).

What relationship did our respondents see between the original collection and Post-Texas Index that we had not seen? We realized that the Post-Texas Index was like the original Texas collection in two ways. One, both collections found their coherence through a single unifying concept. For the original Texas collection, we might call this concept the familiarity of convention (which, through its pervasiveness, enables access). For Post-Texas Index, the concept is the arbitrariness of convention, as demonstrated through the emphasis of syntax over semantics. The arbitrary can be seen as an exaggeration of the familiar, an exaggeration that exposes the familiar as conceptually hollow. But while the Post-Texas Index effectively critiques the foundation of the original Texas collection, it nonetheless has a similarly thin conceptual basis. Two, the foundational concepts for both collections are independent of both the collection content and the designer as a person with an opinion on that content (as opposed to the designer as a flat conceptual construct). The strategy of Post-Texas Index could be applied to other collections, by other people, and while individual decisions might be debated (in terms of applying descriptors and so on), the overall effect would be similar. This of course is an established goal with conventional description, as with the original Texas collection. But Here in Texas and Kaleidescopic Texas are relentlessly specific in being integrated with the collection content and in expressing opinions specific to that content. While the Post-Texas Index author had always been aware that the design was both an exaggeration of traditional description and not integrated with the Texas content, we had not in our initial reflections assimilated the depth of its continued similarity to the original collection.

In terms of our motivating research questions, we think this tells us something about how information collections can foreground the residual. In order for a collection to express the sense of fracture that characterizes the residual—in order to express ambiguity, fluidity, and contradiction in a way that is meaningful, and not chaotic—that fracture does need to be read against a core of coherence, and authenticity provides a form of glue that keeps that core together. But to be a really sticky glue, that authenticity needs to arise from a specific engagement with the specifics of the collection contents.

What good is such a finding? Well, another of our research questions involves the nature of the reading experience for collections oriented toward the residual. Our respondents did not necessarily like or enjoy the more specific transformations, Here in Texas and Kaleidescopic Texas. In fact, the more extensively developed persona, from Here in Texas, was actively disliked by several respondents, who described the persona’s perceived commentary as disdainful, sarcastic, too clever, and other similar assessments. But they were able to “hook in” to the specificity and get into a dialogue with it, even if they didn’t like it. Indeed, some were able to comment productively on Here in Texas because they didn’t like it. One especially perceptive student essay pondered the notion of reader tools, or the means through which a collection can facilitate its reading. Specificity seems like one of those tools for productive critical reading, and a vivid authorial voice is one means to providing it. If we want to encourage active critical reading of information collections, we can think about how to make them more particular and specific, in both aligning with their content and in providing an evidently particular view upon that content. We are of course, aware that this goes against many goals of traditional practice, chief amongst them the interoperability enabled through standardization and convention—but we suggest through this study that the structure of convention discourages critical reading practices.

Conclusion and continued work

Although the project we describe is still in its data analysis phase, we feel that our research design and orientation forms a worthwhile contribution to the repertoire of methods for investigating conceptual issues in knowledge organization, in particular, and information studies, in general. The development of theoretically grounded design experiments, in conjunction with structured reflection from three groups (authors, experts, and student critics), constitutes an innovative advance for conceptual inquiry in knowledge organization, which has tended to focus its scholarship around high-level theoretical discussion. A design research orientation such as the one articulated here complements these existing modes of inquiry and provides a means for extending conceptual discussion into the realm of making.

Such a design focus also enables the development of hybrid research/pedagogy models, enabling students to participate in research as creators, and not just as users. In an extension of the project described here, the 14 student critics who are contributing essays on the initial three design experiments will subsequently be creating their own design experiments using a different digital video library (but with the same environment, the Open Video Digital Library Toolkit). These additional design experiments will provide another, complementary data source for our reflections, as we become the “readers” and our research “participants” become the “authors.”

[1] Geisler, G. Open video digital library toolkit. Software documented and available at http://www.open-video-toolkit.org/